Abstract

Goose astrovirus genotype 2 (GAstV-2) is the causative agent causing severe visceral gout and joint gout in goslings, with mortality rates of affected flocks up to 50%. To date, continuous GAstV-2 outbreaks still pose a great threat to goose industry in China. Although most researches on GAstV-2 have focused on its pathogenicity to geese and ducks, limited studies have been performed on chickens. Herein, we inoculated 1-day-old specific pathogen-free (SPF) White Leghorn line chickens with 0.6 mL of GAstV-2 culture supernatant (TCID50 10−5.14/0.1 mL) via orally, subcutaneously and intramuscularly, and then assessed the pathogenicity. The results revealed that the infected chickens presented depression, anorexia, diarrhea, and weight loss. The infected chickens also suffered from extensive organ damage and had histopathological changes in the heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and thymuses. The infected chickens also had high viral load in tissues and shed virus after the challenge. Overall, our research demonstrates that GAstV-2 can infect chickens and adversely affect the productivity of animals. And the viruses shed by infected chickens can pose a potential risk to the same or other domestic landfowls.

Key words: GAstV-2, chickens, pathogenicity, landfowls

INTRODUCTION

Astrovirus (AstV), of the family Astroviridae, is nonenveloped, single-stranded, positive sense RNA viruses with a genome of 6.4 to 7.9 kb containing 3 open reading frames (ORFs): 1a, 1b, and 2, a 5′-untranslated region (UTR), a 3′-UTR, and a poly (A) tail (Pantin-Jackwood et al., 2011). Astroviridae comprises the genera Mamastrovirus and Avastrovirus (Madeley and Cosgrove, 1975). Genus Avastrovirus consists of strains isolated from avian species and always linked with severe intestinal and extraintestinal disease, such as fatal hepatitis in ducks (Yugo et al., 2016), poult-enteritis mortality syndrome in turkeys (Jindal et al., 2011), runting-stunting syndrome in broilers (Kang et al., 2018), white chicken syndrome in chickens (Long et al., 2018), and visceral gout in goslings (Yang et al., 2018), which caused great economic losses in poultry industry. Although astrovirus infections are thought to be species specific (De Benedictis et al., 2011), the wide variety of species infected, the genetic diversity of the family, and the occurrence of recombination suggests that cross-species transmission of astroviruses could occur. In fact, distinct avian strains have been transmitted across bird species (Pantin-Jackwood et al., 2006; Cattoli et al., 2007; Fu et al., 2009).

Since 2017, a severe infections disease characterized with different degrees of visceral gout, was reported in goslings in the major goose-producing regions in China, which has led to substantial economic losses (Zhang et al., 2018a,b). Several research groups have identified the causative agent as a novel goose astrovirus (GAstV-2) (Niu et al., 2018). Recently, GAstV-2-infected ducklings, with morbid flocks displaying articular and visceral gout (Chen et al., 2020b), indicating the potential for cross-species transmission of GAstV-2 from goose to duck. To date, several reports have revealed the waterfowl-origin astroviruses have been constantly evolving and frequent cross-species transmission is occurring among different waterfowl flocks, bringing greater challenges to the preventing and controlling the disease (He et al., 2022). However, it is unknown whether GAstV-2 could infect other domestic landfowls and possibly cause pathogenicity.

In this study, we successfully established an animal model of infection of GAstV-2 in chickens. The weight changes, clinical symptoms, gross and microscopic pathological changes, viral shedding, and viral load in organs were monitored and systematically analyzed. Our results have enriched the understanding of the GAstV-2 and have laid the foundation for further study of the pathogenic mechanism of this virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus

A GAstV-2 strain named SDPY was isolated, identified, and stored at the Research Institute of Poultry Disease of Shandong Agricultural University. The virus was propagated in Leghorn Male-chicken Hepatocellular-carcinoma cells, and the infectivity titer was 10−5.14/0.1 mL, which was calculated with the Reed and Muench method (Reed and Muench, 1938).

Animals and Ethics Statement

One-day-old specific pathogen-free (SPF) White Leghorn line chickens were purchased from Poultry Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Jinan Spirax Ferrer. The chickens were maintained in SPF chicken isolators with ad libitum feeding. The experimental protocol was approved by the ethical committee for animals in research of Shandong Agricultural University, China.

Pathogenicity Assessment of GAstV-2 in SPF Chickens

A total of 160 one-day-old SPF chickens were randomly divided into 4 groups (n = 50/group): oral infection group, subcutaneous injection group, intramuscular injection group, and control group. SPF chickens in 3 experimental groups were inoculated with 0.6 mL of GAstV-2 culture supernatant (10−5.14/0.1 mL) via oral infection, subcutaneous injection, or intramuscular injection. In contrast, the control group was inoculated with equal doses of phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at the same injection site. The 4 groups were reared in separate SPF isolators, and the feeding conditions were consistent. Water and food were autoclaved before feeding and automatically refilled. Clinical symptoms, gross and microscopic lesions were recorded after infection.

Sample Collection

On the 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 14, 17, 20, 24, 28, 33, 38, 44 days postinoculation (dpi), at each sample collection node, 3 chickens, randomly selected from each group, were weighed and then euthanized with intravenous pentobarbital sodium (New Asia Pharmaceutical, Shanghai, China). After necropsy, the hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, kidneys, bursas, thymuses, pancreas, brains, proventriculi, and intestines were collected. One part of each tissue was used for histopathological examinations. Before euthanasia, blood samples and cloacal swabs of the chickens were collected. Blood specimens, cloacal swabs and the remaining part of each tissue were using for recording the changes of viral load by quantitative real-time PCR.

Histopathology

The collected tissue was fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution and embedded in paraffin. Four micrometer sections were prepared from the paraffin blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological analysis.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR for Viral Load

Viral RNA was extracted from the collected samples using MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) following the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of each RNA sample was measured using the DeNovix DS-11 Spectrophotometer. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the TaKaRa One-Step Prime Script RT-PCR Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) in a total volume of 20 μL based on the Roche LightCycler 96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche, BaselCity, Switzerland). The program of quantitative real-time PCR was performed by using the TaqMan one-step RT-PCR method established in our laboratory (Yin et al., 2020).

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was carried out at least 3 times. The data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) and shown as mean values ± SEM. To investigate the differences among assays, the data were analyzed using ANOVA via the method of Bonferroni (SPSS Statistics 17.0, IBM, New York, NY). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical Signs Following Inoculation With GAstV-2 in Chickens

After GAstV-2 infection, the chickens in each experimental group showed signs of depression, anorexia, and diarrhea with white feces at 4 dpi (Figure 1A–E). However, the chickens in the control group did not show any clinical signs of disease (Figure 1F). No death occurred in each experimental group throughout the experiment.

Figure 1.

Clinical symptoms showing depression, anorexia, diarrhea, and weight loss. (A, D, G) Oral infection group. (B, D, H) Subcutaneous injection group. (C, E, I) Intramuscular injection group. (F) Control group. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. negative control.

GAstV-2 Inhibited the Body Weight Gain of Chickens

Continuous monitoring revealed that the body weight gain of all 3 infection groups was remarkably lower than that of the control group (Figure 1G and H). It occurred at 14 dpi in oral infection group and subcutaneous injection group, and continued until the end of the experiment. The repression of the body weight gain of the intramuscular injection group was also observed at 17 dpi. This unfavorable effect on the body weight gain of subcutaneous injection group was more serious than that of other 2 experimental groups.

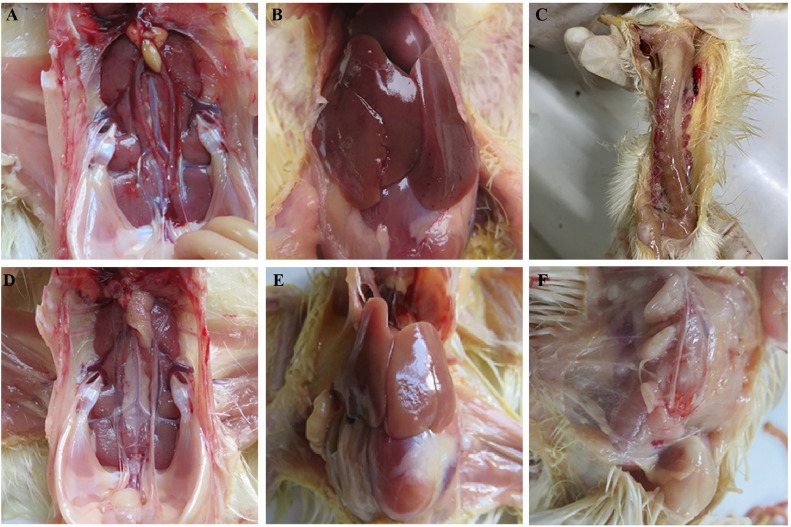

GAstV-2-Induced Organ Injuries

Necropsy in chickens was performed to observe the organ injuries caused by GAstV-2 infection. In general, the gross lesions reported in GAstV-2-infected chickens were characterized by gout with urate deposits in ureter, hemorrhage and swellings of kidneys (Figure 2A), hemorrhage and enlargement in livers (Figure 2B), and severe hemorrhage of thymuses (Figure 2C). No any clinical symptoms were found in control chickens in this experiment (Figure 2D–F).

Figure 2.

Gross lesions caused by GAstV-2. (A) Swellings of kidney and urate deposits in ureter. (B) Hemorrhage and enlargement in liver. (C) Severe hemorrhage of thymuses. (D–F) No any clinical symptoms were found in control group.

GAstV-2-Induced Histopathological Changes in Organs

Histopathological examination revealed that there were obvious and almost identical histopathological changes in each experimental group at 11 dpi. The most significant microscopic lesions were in heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and thymus. Myocardial fiber hemorrhage, rupture, myocardial interstitial edema, and mild inflammatory cell infiltration were observed in cardiac tissues (Figure 3A and B). The livers exhibited hepatic steatosis, necrosis, and hemorrhage (Figure 3C and D). The spleen showed lymphopenia and focal necrosis (Figure 3E and F). Lesions in the kidneys were characterized by glomerular swelling and hemorrhages, inflammatory cell infiltration in renal tubular and renal interstitial hemorrhage (Figure 3G and H). In the thymus, a large amount of exudation of erythrocyte in the medulla and cortex was observed (Figure 3I and J).

Figure 3.

Histopathology lesions of organs induced by GAstV-2 infection. (A, B) Heart. (C, D) Liver. (E, F) Spleen. (G, H) Kidney. (I, J) Thymus. (a–e) Normal tissue control. Tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, 200×).

Stable Viral Shedding in the Blood and Cloaca of Chickens Induced by GAstV-2

By detecting the virus RNA in the blood and cloaca at different time points, we arrived at the viral shedding rule after infection. The detection results of GAstV-2 copy number in blood were shown in Figure 4A. Viral copy numbers in the 3 infection groups could be detected in the blood as early as 1 dpi, and viral copy number in the intramuscular injection group reached 1 replication peak at 5 dpi, with the other 2 groups reaching the replication peaks at 7 dpi. Subsequently, viral load declined with time. The changes of virus copy number in blood were almost the same in 3 infection groups. The detection results of GAstV-2 copy number in cloacal swabs were shown in Figure 4B. The changes of virus copy number in cloacal swabs were almost the same as in blood. Note that the viral RNA was not detected in the control group.

Figure 4.

Rules of viral shedding in the blood and cloaca. (A) The viral copy numbers in blood and (B) cloacal swabs. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3).

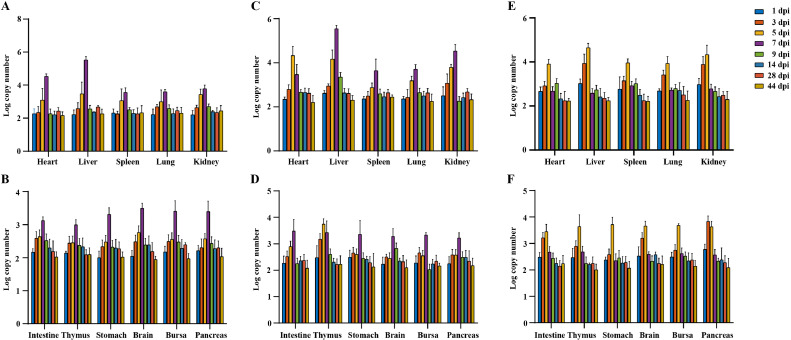

Replication Kinetics of GAstV-2 in Tissues

Using qPCR, copy numbers of the GAstV-2 genome were quantified in 11 tissues of infected chickens on the 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 14, 28, 44 dpi. Figure 5 shows active replication of GAstV-2 detected in all 11 tissues throughout the experimental period. At 1 dpi, the presence of virus was detected in all tissues and organs that we collected. Notably, more virus copy numbers were found in the livers than in other tissues. Furthermore, virus copy numbers in all investigated tissues showed similar trend in both oral and subcutaneous infection groups, and attained high levels in all investigated tissues at 5 and 7 dpi. Virus copy numbers of all investigated tissues in the intramuscular infection group peaked earlier than the other 2 groups, reaching the maximum at 5 dpi. No positive viral RNA was recorded in the control goslings in this study.

Figure 5.

Kinetic of GAstV-2 loads in tissues. (A, B) The viral copy numbers in tissue samples of oral infection group. (C, D) The viral copy numbers in tissue samples of subcutaneous infection group. (E, F) The viral copy numbers in tissue samples of intramuscular infection group. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Since 2017, a remarkably increasing number of commercial goslings infected with GAstV-2 have been reported in many provinces in mainland China (Liu et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020a). The sudden emergence of goose-derived GAstV-2 results in visceral gout and high mortality, and its spread has caused severe economic damage to the goose industry in China. Due to the lack of targeted vaccines and appropriate medicines, it is difficult to control or prevent GAstV-2 infection. Additionally, the wide range of Avastrovirus-infected birds due to genetic diversity is another major reason for the high prevalence of GAstV-2, as do reports that Avastrovirus such as ANV, CAstV, and TAstV-1 can cause infection in other avian species (Johnson et al., 2017). GAstV-2 has also been detected in cherry valley ducklings and Muscovy ducklings, which suggests potential cross-species transmission of GAstV-2 in avians (Chen et al., 2020b, 2021). Although this virus has been widespread, there have been no detailed studies on the pathogenicity of GAstV-2 to chickens. Hence, we inoculated 1-day-old SPF White Leghorn line chickens with GAstV-2 culture supernatant via orally, subcutaneously and intramuscularly, and then assessed the pathogenicity and tissue tropism.

Similar to the clinical symptoms of affected goslings, the chickens in each experimental group showed signs of depression, anorexia, and diarrhea with white feces, but no death was observed. Pathological and histopathological lesions of GAstV-2-infected chickens were in kidney, liver, heart, spleen and thymus, and other organs of SPF chickens after GAstV-2 infection were relatively obvious, but the lesions were minor compared with those of infected goslings (Yin et al., 2021). Unlike the infected goslings, the infected chickens showed severe hemorrhage of thymuses. This suggests that GAstV-2 may cause significant damage to the immune system of chickens, and infected chickens have lower resistance and are more susceptible to the attack of other pathogenic agents in the external environment.

Compared with the control group, chickens in the infected groups grew slowly and gained less weigh. In addition, the unfavorable effect on the body weight gain of the chickens in subcutaneous injection group was the most serious, which was consistent with the results of pathogenicity test in goslings (Yin et al., 2021). It indicates that GAstV-2 has a significant effect on the weight gain of chickens. Although GAstV-2-infected chickens don't die, the poor productivity performance of these chickens is a potential risk to harm the breeding industry.

GAstV-2 RNA was detected in the blood from infected chickens at 1 dpi, indicating the primary viremia can be developed less than 24-h postinfection. Viral loads could be detected continuously in the cloacal swabs of GAstV-2-infected chickens. Viral nucleic acids released from the cloaca, which contaminate feed and drinking water, cause more widespread infections. It suggests effective measures to by which disease spread could be prevented.

Viral RNA was found in all investigated tissues samples from the infected chickens and maintained at high levels in vital tissues, suggesting that GAstV-2 has a wide tissue tropism. The liver contained the highest concentration of GAstV-2, indicating that it may be the main target organ of GAstV-2. Such result was different from other studies (Yin et al., 2021), which revealed that viral load in the kidney was higher than that in the liver, heart, and spleen. In addition, target organs may also include kidney and heart, and they could be used as options for detection of GAstV-2 due to high viral copy numbers. In this study, the changes of viral loads in cloacal swabs, blood, and various organs were basically the same. Reasonable immunization procedures can be formulated according to the shedding virus in production practice. During the peak period of viral loads, the disinfection of chicken house should be strengthened to prevent the wide spread of the disease.

The present pilot challenge experiment evidenced for the first time that, in addition to waterfowls, GAstV-2 can also infect domestic chickens through multiple ways and can cause disease in this species. Broad tropism and the potential for cross-species transmission of this virus cannot be excluded, and the possibility that this virus is able to infect other domestic landfowls such as turkeys, guinea fowl, and pigeons is likely. Therefore, prophylactic measures to control this virus may need to be investigated and implemented by animal health companies and poultry farmers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-42-19); National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872500, 32172845); Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020MC183); The Higher Education Support Program of Youth Innovation and Technology of Shandong Province, China (2019KJF022).

Author Contributions: Conceived and designed the experiments: Y. D., Y. T., D. H. Performed the experiments: D. H., X. J. Analyzed the data: D. H., X. J. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: D. H., X. J. Wrote the paper: D. H.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Cattoli G., De Battisti C., Toffan A., Salviato A., Lavazza A., Cerioli M., Capua I. Co-circulation of distinct genetic lineages of astroviruses in turkeys and guinea fowl. Arch. Virol. 2007;152:595–602. doi: 10.1007/s00705-006-0862-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Xu X., Yu Z., Sui C., Zuo K., Zhi G., Ji J., Yao L., Kan Y., Bi Y., Xie Q. Characterization and genomic analysis of emerging astroviruses causing fatal gout in goslings. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020;67:865–876. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Yu Z., Xu X., Ji J., Yao L., Kan Y., Bi Y., Xie Q. First report of a novel goose astrovirus outbreak in Muscovy ducklings in China. Poult. Sci. 2021;100 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhang B., Yan M., Diao Y., Tang Y. First report of a novel goose astrovirus outbreak in Cherry Valley ducklings in China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020;67:1019–1024. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Benedictis P., Schultz-Cherry S., Burnham A., Cattoli G. Astrovirus infections in humans and animals – molecular biology, genetic diversity, and interspecies transmissions. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011;11:1529–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Pan M., Wang X., Xu Y., Xie X., Knowles N.J., Yang H., Zhang D. Complete sequence of a duck astrovirus associated with fatal hepatitis in ducklings. J. Gen. Virol. 2009 doi: 10.1099/vir.0.008599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D., Wang F., Zhao L., Jiang X., Zhang S., Wei F., Wu B., Wang Y., Diao Y., Tang Y. Epidemiological investigation of infectious diseases in geese on mainland China during 2018–2021. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022;69:3419–3432. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal N., Patnayak D.P., Chander Y., Ziegler A.F., Goyal S.M. Comparison of capsid gene sequences of turkey astrovirus-2 from poult-enteritis-syndrome-affected and apparently healthy turkeys. Arch. Virol. 2011;156:969–977. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-0931-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C., Hargest V., Cortez V., Meliopoulos V., Schultz-Cherry S. Astrovirus pathogenesis. Viruses. 2017;9:22. doi: 10.3390/v9010022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K., Linnemann E., Icard A.H., Durairaj V., Mundt E., Sellers H.S. Chicken astrovirus as an aetiological agent of runting-stunting syndrome in broiler chickens. J. Gen. Virol. 2018;99:512–524. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Jiang M., Dong Y., Wang X., Zhang D. Genetic characterization of a novel group of avastroviruses in geese. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018;65:927–932. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long K.E., Ouckama R.M., Weisz A., Brash M.L., Ojkić D. White Chick syndrome associated with chicken astrovirus in Ontario, Canada. Avian Dis. 2018;62:247–258. doi: 10.1637/11802-012018-Case.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeley C.R., Cosgrove B.P. Viruses in infantile gastroenteritis. Lancet. 1975;306:124. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu X., Tian J., Yang J., Jiang X., Wang H., Chen H., Yi T., Diao Y. Novel goose astrovirus associated gout in gosling, China. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;220:53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin-Jackwood M.J., Spackman E., Woolcock P.R. Phylogenetic analysis of turkey astroviruses reveals evidence of recombination. Virus Genes. 2006;32:187–192. doi: 10.1007/s11262-005-6875-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin-Jackwood M.J., Strother K.O., Mundt E., Zsak L., Day J.M., Spackman E. Molecular characterization of avian astroviruses. Arch. Virol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed L.J., Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Tian J., Tang Y., Diao Y. Isolation and genomic characterization of gosling gout caused by a novel goose astrovirus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018;65:1689–1696. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D., Tian J., Yang J., Tang Y., Diao Y. Pathogenicity of novel goose-origin astrovirus causing gout in goslings. BMC Vet. Res. 2021;17:40. doi: 10.1186/s12917-020-02739-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D., Yang J., Tian J., He D., Tang Y., Diao Y. Establishment and application of a TaqMan-based one-step real-time RT-PCR for the detection of novel goose-origin astrovirus. J. Virol. Methods. 2020;275 doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2019.113757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X., Meng K., Zhang Y., Yu Z., Ai W., Wang Y. Genome analysis of newly emerging goose-origin nephrotic astrovirus in China reveals it belongs to a novel genetically distinct astrovirus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;67:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yugo D.M., Hauck R., Shivaprasad H.L., Meng X.-J. Hepatitis virus infections in poultry. Avian Dis. 2016;60:576–588. doi: 10.1637/11229-070515-Review.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Cao Y., Wang J., Fu G., Sun M., Zhang L., Meng L., Cui G., Huang Y., Hu X., Su J. Isolation and characterization of an astrovirus causing fatal visceral gout in domestic goslings. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0074-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Ren D., Li T., Zhou H., Liu X., Wang X., Lu H., Gao W., Wang Y., Zou X., Sun H., Ye J. An emerging novel goose astrovirus associated with gosling gout disease, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]