Abstract

Objectives

To examine the association of sleep duration and timing with BMI among adults. Also, to identify obesogenic and unhealthy behaviors (e.g.diet/sleep quality, physical activity, screen time, smoking) associated with short sleep duration and late bedtime.

Participants

Participants (n=755) were part of exploratory, population-based research, with data collection in a virtual environment.

Methods

For purposes of characterizing the population we considered short sleepers<7h/night, and the population bedtime median was used to stratify participants into early and late sleepers (before and after 23:08). Student's t-test and chi-square test were performed to assess differences in characteristics between groups. Linear regression analyses were conducted to determine the association of sleep duration, bedtime, and wake-up time with BMI. Quantile regression was estimated for the 25th, 50th, and 75th quantiles to identify the distributional correlations between BMI and sleep variables. Restricted cubic splines were also used to study the shape of the association between sleep-BMI. Analyses were adjusted for potential confounding variables.

Results

BMI decreased by 0.40Kg/m2 for each additional hour of sleep duration [95%CI=-0.68,-0.12,p=0.005] and increased by 0.37 kg/m2 for each additional hour of bedtime [95%CI=0.12,0.61,p=0.003]. The association between bedtime and BMI remained even after adjustment for sleep duration. These effects were higher and stronger with higher BMI values (p75th). Wake-up time did not show statistically significant associations.

Conclusions

Because we found that beyond sleep duration, bedtime was significantly associated with BMI, our data reflect the pertinence of assessing sleep timing patterns in disentangling sleep-obesity association. Insights into the characteristics, obesogenic and unhealthy behaviors related to short and late sleep may support specific strategies to prevent and treat excess body adiposity and other negative health outcomes.

Keywords: Body mass index (BMI), Obesity, Overweight, Sleep, Bedtime, Lifestyle

Highlights

-

•

This is the first Brazilian survey on chronobiological aspects related to sleep.

-

•

Both sleep duration and bedtime were associated with BMI.

-

•

The effects of sleep duration and bedtime were higher and stronger with higher BMI values (p75th).

-

•

Our data reflect the pertinence of assessing sleep timing in disentangling sleep-obesity association.

1. Introduction

In parallel with the growing epidemics of obesity and overweight, average sleep duration and quality are decreasing in modern society [1]. In the United States, data from the National Health Interview Survey has shown that self-reported mean sleeping time decreased by 10–15min from 1985 to 2012, while the percentage of adults reporting less than 6 h of sleep per night increased by 31% [2]. In a global quantification of sleep schedules using smartphone data, Brazil appeared as the third country with the shortest sleep duration, and average bedtime was the main assigned predictor [3].

Emerging evidence from both cross-sectional and longitudinal epidemiological studies [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8]] is accumulating to suggest the association between sleep deprivation and higher values of body mass index (BMI). The main proposed mechanisms underlying why short sleep may cause increased body weight include: increase caloric consumption given the greater number of waking hours and opportunities to eat [9,10]; an orexigenic pattern due to decreased leptin and/or increased ghrelin [11,12]; decreased physical activity and energy expenditure, perhaps due to increased daytime fatigue and sleepiness [13]; and, increased systemic inflammation [14].

In recent years, beyond the sleep duration, sleep timing, including bedtime and wake-up time, has been suggested as another important modifiable sleep behavior that plays a role in obesity [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]]. Firstly, later bedtime may be a driver of shorter sleep duration, given that individuals who go to bed later may not be able to compensate by sleeping later the next morning due to work, and social schedules. Secondly, altered sleep timing may lead to circadian disruption, which can have independent effects on biology and behavior, including, for example, alterations in leptin and glucose [20]. In addition, later bedtime, by increasing the opportunity for eating late at night - during the biological night, relative to melatonin onset - may also play a role as a risk factor for overweight and other metabolic outcomes as a result of circadian disorders [[21], [22], [23]]. A self-reported preference for later sleep has also been associated with poorer health behaviors in diverse domains, such as consumption of obesogenic food, increased smoking, alcohol use, and, prolonged exposure to artificial light at night [15,19].

Although more evidence needs to be warranted, it has also been observed a trend toward higher adiposity as wake-up timing is advanced [24]. However, [25]; by showing that sleep loss during the second half of the night has altered morning glucagon and cortisol levels, suggested that the timing of sleep restriction can potentiate its deleterious effects. In addition, early wakefulness may be related to impaired insulin sensitivity due to raised melatonin levels during the early-morning period [26].

As seen, studies about the relationship between sleep timing and adiposity are still limited and so, the sleep-obesity association has not been fully clarified. Few investigations have concurrently determined associations of sleep duration and bedtime with lifestyle or health behaviors, nevertheless. Furthermore, most of the research was carried out in high-income countries, especially Europe and North America, and it is known that sleep habits are substantially influenced by socioeconomic, cultural, seasonal conditions, and local work schedules [3].

So, once there is no previous population-based survey about sleep habits in Brazil, this study was carried out to evaluate whether sleep duration, bedtime, and wake-up time were associated with BMI, using data from, as far as we know, the largest sleep-related survey with Brazilian adults. We also aimed to identify obesogenic and unhealthy behaviors (e.g. poor diet quality, insufficient physical activity, longer screen time, smoking) associated with short sleep duration and late bedtime. After controlling for several potential confounding factors, we hypothesized that (1) sleep duration and sleep timing (bedtime and wake-up time) would be, respectively, negatively, and positively associated with BMI and (2) the association of sleep timing with BMI would be independent of sleep duration.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and population

This study was carried out with data from the first stage of the SONAR-Brazil Survey, which aims to investigate chronobiological aspects related to sleep, food, and nutrition in Brazilian adults. This is exploratory, population-based research, with data collection exclusively in a virtual environment. Participants were adults, non-pregnant, aged between 18 and 65 years, born and residing in all regions of Brazil (n=808). After excluding participants who declared night workload (between midnight and 6:00) (n=12) and shift work (n=41) we analyzed data for the remaining 755 non-pregnant Brazilian adults.

Considering a large population, to estimate population proportions with a confidence level of 95% and a margin error of 5% we defined, a priori, a minimum sample size of 385 valid questionnaires. However, the sample size remained open, and the efforts were directed to increase as maximum as possible to minimize the error margin. The final sample of 755 guarantees proportion estimates with a 95% confidence level and a margin of error lower than 4%. All data collection procedures have been conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Committee of Research Ethics.

Recruitment took place between August and December 2021 and data were collected using a Google Form. By clicking on the research link, the volunteer respondents were directed to informed consent and, only after indicating their consent to participate in the study, they were directed to the questionnaire, made up of four blocks: characterization, health, and lifestyle, sleep characteristics, eating and sleeping schedules. The generated responses were automatically stored in spreadsheets compatible with Microsoft Office Excel and later exported to the statistical software STATA 13 statistical software (Stata Corporation) for statistical analyses. The link to the online questionnaire was disseminated in several ways: referral of health professionals' reports in newspapers/magazines, advertisements on social media platforms, research institutes, health fairs, events scientific journals, and electronic pages addressing the research participants, to increase research visibility and, consequently, data collection.

2.2. Anthropometric parameters

For anthropometric evaluation, the BMI [weight(Kg)/height(m)2] was calculated, based on self-reported weight and height. The classification of nutritional status was performed based on the cutoff points established by the World Health Organization (WHO) [27].

2.3. Sleep traits

In the questionnaire block about ‘eating and sleeping schedules’, the participants were informed: 'In this section, we want to know your routine on weekdays (work days) and weekends (free days)'. The following questions were used to measure usual sleep and wake times: ‘Considering your habits during the last month, on a typical weekday (or weekend)’ 1. What time do you wake up? 2. What time do you sleep? Responses were in 30-min increments.

From the responses, “wake time”, and “bedtime” was obtained (represented as clock time, hh:mm), and for each variable, the weekly average was calculated as follows: [(5 × weekdays value) + (2 × weekend value)]/7.

Sleep duration (h) was calculated as the difference between bedtime and wake time. The average sleep duration across the entire week was calculated as follows: [(5 × sleep duration on weekdays) + (2 × sleep duration on weekends)]/7.

The chronotype was estimated based on the sleep-corrected midpoint of sleep, which is proposed to clean the chronotype of the confounder sleep debt [28]. For participants whose sleep duration on free days was longer than work days, the midpoint was calculated as follows: [bedtime on free days + (sleep duration on free days/2)]. For participants whose sleep duration on free days was shorter than work days, due to the sleep debt accumulated over the workweek, the corrected midpoint of sleep was applied, and calculated as follows: [bedtime on free days + (weekly average sleep duration/2)]. For more details on the methodology see ROENNEBERG, WIRZ-JUSTICE, MERROW, 2003; [28].

For purposes of characterizing the population, we considered short sleepers:<7h/night, based on the cut-off point established by the National Sleep Foundation (recommended sleep duration between 7 and 9 h/night) [29], and participants were dichotomized into early and late sleepers by the median of participants' bedtime (before and after 23:08), as performed in other studies, given that there is no consensus about the most appropriate clock time to sleep.

2.4. Diet quality and lifestyle traits

Food consumption was investigated using a food frequency questionnaire comprising 19 food/preparation categories, for which participants selected the frequency of weekly consumption: 'never’, 'sometimes (1–3 days/week)', 'almost always (4–6 days/week)' or 'always (6–7 days/week)'. Diet quality was evaluated based on the Food Guide for the Brazilian Population [30] and adopted the methodology proposed by Ref. [31].

Food markers for healthy eating (fresh fruits; vegetables and/or legumes; beans, chickpeas, lentils and/or peas; milk and/or dairy products; eggs; meats; fish) received increasing scores (never = 0; sometimes = 1; almost always = 2; always = 3), while unhealthy eating markers (snacks; chocolate; fried snacks; instant noodles, packaged snacks or crackers; fast food; hamburger and/or sausages; coffee; soda cola-based; sweetened beverages; mate or black tea; guarana powder; alcoholic beverages), decreasing (never = 3; sometimes = 2; almost always = 1; always = 0). From the sum of the scores of each food category, the total score of the Diet Quality Index (DQI) was obtained, which could range from 0 to 57 points, with a higher score suggestive of a higher frequency of consumption of healthier foods and lower frequency of consumption of unhealthy foods. Sequentially, from the available scores, it was created tertiles for diet quality classification: 1st tertile – low quality (21–34 points); 2nd tertile – intermediate quality (35–38 points), and 3rd tertile – good quality (39–47 points).

Physical activity was measured through the following questions: “On which days of the week do you practice physical exercise or sport (moderate-to vigorous-intensity activity)?“, “How long is that in each day of practice?“, answered in minutes. The weekly duration of physical activity was calculated sequentially [number of days/week x duration/day]. As defined by WHO [32] it was considered as insufficient physical activity <150 m/week of moderate-to vigorous-intensity activity.

Finally, screen time per day and before bed were evaluated by the questions: “In your free time (not counting work/study), how many hours/day do you spend watching TV, on your computer, tablet, or cell phone?” and “Right before bedtime, how long do you spend using screens (eg. TV, computer, tablet, or cell phone)?“.

Some other details of the survey questionnaire concerning other covariates including education, marital status, smoking, and drinking were included in our study.

2.5. Statistical analyses

To assess differences between both, short and non-short sleepers, as well as between early and late bedtime groups, in their characteristics and lifestyle traits, student's t-test (for continuous variables) and chi-square test (for categorical variables) were performed.

Moreover, linear regression analyses evaluated differences in BMI (as the outcome variable) associated with sleep duration, bedtime, and wake-up time. In addition, quantile regression was estimated for the 25th, 50th, and 75th quantiles to identify the distributional correlations. These analyses were performed in the following stages: Model 1: was unadjusted for each sleep variable, Model 2: included each sleep variable singularly, and the following adjustment variables: gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol, and smoking. Finally, to identify whether the association of sleep timing would be independent of sleep duration, for bedtime and wake-up time, a third Model included all Model 2 variables and sleep duration and for sleep duration, the third Model included all Model 2 variables and bedtime. Regression coefficient (β) and 95% CIs were calculated for the unadjusted and adjusted models.

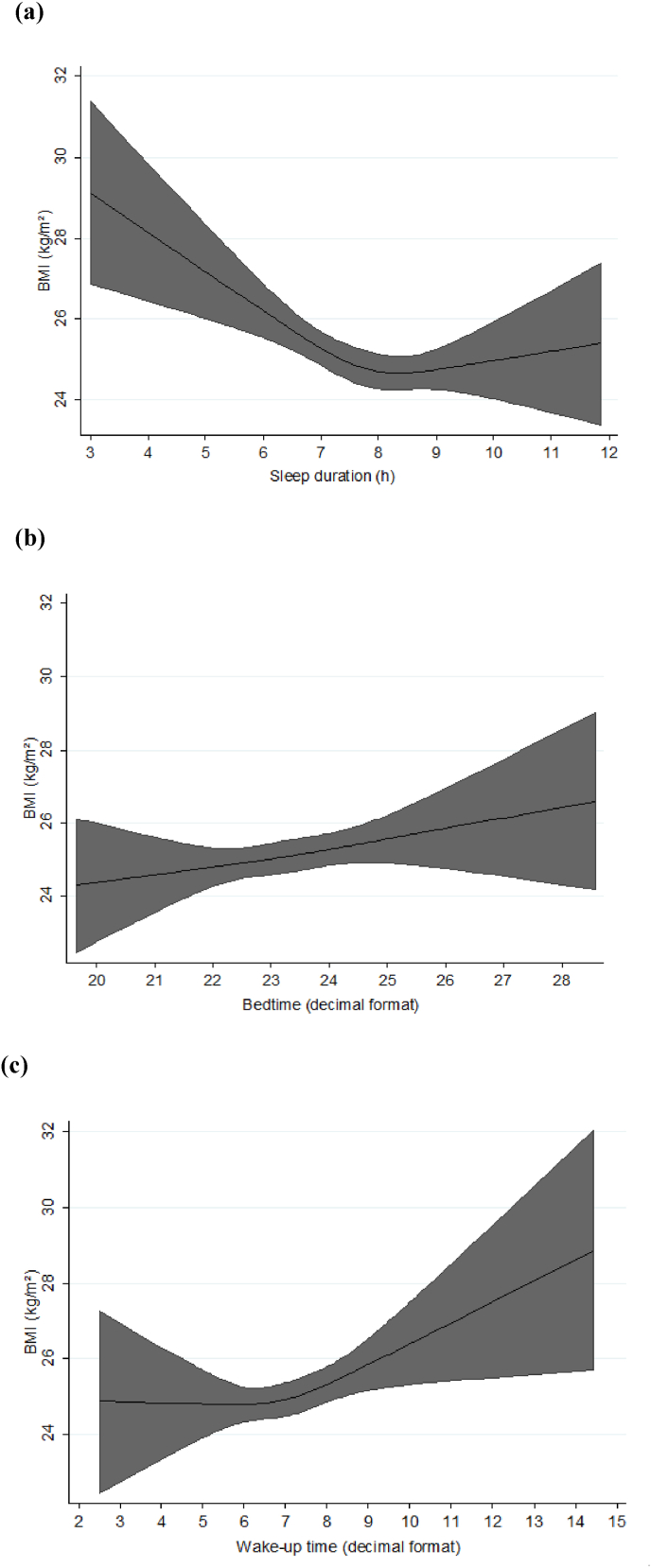

Restricted cubic splines were also used to study the shape of the association between sleep markers (duration, bedtime, and wake-up time) and BMI. A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 755 adults [age: 33 y (range 18–65); ∼73% women, BMI: ∼25kg/m2, ∼45% with overweight, ∼23% short sleepers, and ∼50% late sleepers] were enrolled (Table 1). Characteristics of the participants depending on the sleep duration (less or more than 7 h) and bedtime (before and after 23:08) are also shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics and lifestyle traits of participants according to sleep duration and bedtime.

| Variables | All | Sleep Duration |

P value* | Bedtimeb |

P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Short Sleepers (n=581) | Short Sleepers (n=174) | Early Sleepers (n=380) | Late Sleepers (n=375) | ||||

| Total,% | 100 | 76.9 | 23.1 | 50.3 | 49.7 | ||

| Gender,%female | 73.5 | 75.0 | 68.4 | 0.08 | 78.2 | 68.8 | 0.004 |

| Age,y | 33.4±11.1 | 33.1±11.0 | 34.4±11.3 | 0.18 | 35.3±11.2 | 31.5±10.7 | <0.001 |

| Educationlevel | |||||||

| Less than High School,% | 1.5 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 0.04 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.01 |

| High school,% | 27.9 | 27.7 | 28.7 | 23.2 | 32.8 | ||

| College graduate or above,% | 70.6 | 71.4 | 67.8 | 75.5 | 65.6 | ||

| Brazilmacro-region | |||||||

| North,% | 3.3 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 0.13 | 2.4 | 4,3 | 0.18 |

| North East,% | 68.3 | 66.6 | 74.1 | 70.5 | 66,1 | ||

| Southeast,% | 20.3 | 22.2 | 13.8 | 19.7 | 20,8 | ||

| South,% | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 4,8 | ||

| Midwest,% | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4,0 | ||

| MaritalStatus | |||||||

| Married/Living with Partner,% | 38.5 | 39.9 | 33.9 | 0.15 | 47.1 | 29,9 | <0.001 |

| BMI,kg/m2 | 25.1±5.0 | 24.8±5.0 | 26.0±5.1 | 0.006 | 24.8±4.8 | 25.4±5.2 | 0.13 |

| Overweight(BMI≥25kg/m2),% | 44.8 | 42.7 | 51.7 | 0.03 | 44.5 | 45,1 | 0.87 |

| Dietquality | 35.7±4.3 | 35.8±4.2 | 35.4±4.5 | 0.23 | 36.1±4.3 | 35,3±4,2 | 0.01 |

| Low (1st tertile),% | 38.7 | 38.4 | 39.7 | 0.95 | 36.6 | 40,8 | 0,03 |

| Intermediate (2d tertile),% | 34.7 | 34.9 | 33.9 | 32.6 | 36,8 | ||

| Good (3rd tertile),% | 26.6 | 26.7 | 26.4 | 30.8 | 22,4 | ||

| Sleeptraits | |||||||

| Sleep duration,h/night | 7.7±1.2 | 8.2±0.9 | 6.2±0.7 | <0.001 | 8.2±1.0 | 7.4±1.2 | <0.001 |

| Wake-up time,hh:mm | 07:06±1:24 | 07:18±1:24 | 06:18±1:30 | <0.001 | 06:30±1:06 | 07:42±1:30 | <0.001 |

| Bedtime,hh:mm | 23:18±1:24 | 23:06±1:18 | 00:06±1:36 | <0.001 | 22:18±0:42 | 00:18±1:12 | <0.001 |

| Nocturnal awakenings,n/night | 1.4±1.3 | 1.3±1.2 | 1.6±1.5 | 0.002 | 1.5±1.2 | 1.3±1.3 | 0.16 |

| Poor Sleep Quality,% | 33.1 | 28.2 | 49.4 | <0.001 | 27.6 | 38.7 | 0.001 |

| Chronotype,% | |||||||

| Morning | 62.9 | 63.0 | 62.6 | 0.49 | 89.2 | 36,3 | <0.001 |

| Indifferent | 21.2 | 21.9 | 19.0 | 9.2 | 33.3 | ||

| Evening | 15.9 | 15.1 | 18.4 | 1.6 | 30,4 | ||

| Lifestyletraits | |||||||

| Physical Activity,% yes | 65.2 | 66.4 | 60.9 | 0.18 | 67.1 | 63,2 | 0.26 |

| Physical activity,m/week | 155.4±176.0 | 151.0±165.3 | 169.9±207.3 | 0.21 | 163.1±190.6 | 147,6±159,6 | 0.22 |

| < 150 m/week,% | 56.4 | 58.0 | 51.1 | 0.11 | 57.9 | 54.8 | 0.38 |

| Screen Time,m/day | 219.9±167.2 | 217.7±164.0 | 227.2±177.8 | 0.51 | 192.5±144.6 | 247,8±183.4 | <0.001 |

| Screen Time before bed,m | 68.6±87.3 | 62.0±72.7 | 90.8±121.8 | <0.001 | 58.3±73.4 | 79,1±98,4 | 0.001 |

| Smokers,% | 3.6 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 0.19 | 2.1 | 5.1 | 0.03 |

| Alcohol use,% | 49.8 | 50.3 | 48.3 | 0.64 | 46.8 | 52,8 | 0.10 |

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index.

Values are shown as means ± SDs or percentages.

a Sleep duration groups were defined as follows: non-short-sleepers≥7 h/night, short-sleepers<7 h/night [ [29]].

*P values are derived from the student's t-test (for continuous variables) and the chi-square test (for categorical variables). Significant P-values ≤0.05 are shown in bold.

Bedtime groups were defined, depending on the median population as follows: early-sleepers≤23:08, late-sleepers>23:08.

Higher BMI averages were observed among short sleepers, compared to non-short sleepers (a difference of ∼1.2 kg/m2). On average, participants spend more than 1 h using screens right before bedtime and this time was longer among short and late sleepers, compared with longer and earlier sleepers (differences of 28.8 m and 20.8 m, respectively) (all p≤0.05) (Table 1).

As expected, short sleepers had a later bedtime and earlier wake-up time (difference of 1 h), more nocturnal awakenings, and a higher percentage of self-reported poor sleep quality (∼49% versus ∼28%) than the non-short sleep group. Late sleepers, compared to those who slept earlier, had later wake-up time (difference of 72 m), shorter sleep duration (difference of 48 m), higher percentages of self-reported poor sleep quality (∼39% versus ∼28%), and lower diet quality score (all p≤0.05) (Table 1).

Results from linear regression analyses with each sleep variable can be found in Table 2. Regarding sleep duration, the simple regression model has shown a statistically significant lower BMI [β=-0.55, 95% CI=-0.85, −0.25, p<0.001], and the result did not change when the analysis was adjusted for gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol, and smoking. Indeed, BMI decreased by 0.40 kg/m2 for each additional hour of sleep [95% CI=-0.68, −0.12, p=0.005]. However, when adjusted for bedtime, sleep duration was not associated with BMI.

Table 2.

Associations of sleep duration, bedtime, and wake-up time with BMI.

| Sleep Variables | Unadjusted |

Adjusted Model 1 |

Adjusted Model 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value | |

| SleepDuration | −0.55 (−0.85,-0.25) | <0.001 | −0.40 (−0.68,-0.12) | 0.005 | −0.27 (−0.58; 0.04) | 0.08a |

| Bedtime | 0.18 (−0.07,0.44) | 0.15 | 0.37 (0.12,0.61) | 0.003 | 0.27 (−0.00,0.53) | 0.05a |

| Wake-uptime | −0.20 (−0.45,0.05) | 0.11 | 0.06 (−0.18,0.30) | 0.61 | 0.25 (0.01,0.50) | 0.06b |

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index; CI, Confidence Interval.

β values reflect the difference in BMI (Kg/m2) for each increased hour of each sleep variable.

Unadjusted Model: univariate association of sleep duration, bedtime and wake-up time, and BMI.

Adjusted Model 1: sleep duration, bedtime, and wake-up time were separately entered into multiple models after adjusting for the participants' gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol, and smoking.

Significant P−values ≤ 0.05 are shown in bold.

Adjusted Model 2: sleep duration and bedtime were simultaneously entered into multiple models after adjusting for the participants' gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol, and smoking.

Adjusted Model 2: wake-up time and sleep duration were simultaneously entered into multiple models after adjusting for the participants' gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol, and smoking.

Bedtime was positively associated with BMI, in the adjusted models, such that participants had 0.27 kg/m2 higher BMI values [95% CI=0.00, 0.53, p=0.05] per additional hour of bedtime, independent of sleep duration and other confounders variables.

These associations can also be seen in the multiple quantile regression for the 25th, 50th, and 75th quantiles (Table 3), which provides interesting insights. The effect of sleep duration and bedtime increases as the BMI percentile increases, showing that the effects are higher and stronger with higher BMI values. No association was found between wake-up time and BMI either in unadjusted or adjusted Models (Table 2, Table 3).

Table 3.

Quantile regression associations of sleep duration, bedtime, and wake-up time with BMI.

| Sleep Variables | 25th |

50th |

75th |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sleep Duration | ||||||

| AdjustedModel1 | −0.14 (−0.40,0.11) | 0.26 | −0.21 (−0.51,0.09) | 0.16 | −0.63 (−1.06,1.19) | 0.005 |

| AdjustedModel2 | −0.13 (−0.44,0.17) | 0.38 | −0.17 (−0.52,0.17) | 0.32 | −0.52 (−1.00,-0.04) | 0.03a |

| Bedtime | ||||||

| AdjustedModel1 | 0.05 (−0.18,0.28) | 0.68 | 0.23 (−0.03,0.49) | 0.08 | 0.50 (0.08,0.91) | 0.02 |

| AdjustedModel2 | 0.03 (−0.23,0.30) | 0.80 | 0.17 (−0.13,0.17) | 0.32 | 0.32 (−0.10,0.74) | 0.13a |

| Wake-uptime | ||||||

| AdjustedModel1 | −0.05 (−0.27,0.17) | 0.68 | 0.00 (−0.25,0.25) | 0.99 | −0.11 (−0.52,0.30) | 0.59 |

| AdjustedModel2 | 0.03 (−0.23,0.30) | 0.80 | 0.17 (−0.13,0.47) | 0.27 | 0.32 (−0.10,0.74) | 0.13b |

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index; CI, Confidence Interval.

β values reflect the difference in BMI (Kg/m2) for each increased hour of each sleep variable.

Adjusted Model 1: sleep duration, bedtime, and wake-up time were separately entered into multiple models after adjusting for the participants' gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol, and smoking.

Significant P-values ≤0.05 are shown in bold.

Adjusted Model 2: sleep duration and bedtime were simultaneously entered into multiple models after adjusting for the participants' gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol, and smoking.

Adjusted Model 2: wake-up time and sleep duration were simultaneously entered into multiple models after adjusting for the participants' gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol, and smoking.

Restricted cubic splines modeling (Fig. 1) showed that the lowest value of BMI was seen in the sleep duration of ∼8h/night (a) and the positive association of bedtime with BMI was linear (b). Higher values of BMI can be seen upon a wake-up time from ∼7:00 (c).

Fig. 1.

Sleep duration, Bedtime, Wake-up time, and BMI. Black lines plot the predicted BMI values with 95% confidence intervals (grey fill). Models are adjusted for gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol, smoking, and sleep duration (except for (a) sleep duration).

4. Discussion

As far as we are aware, this is the first Brazilian survey on chronobiological aspects related to sleep, and also the first study to investigate the association of sleep duration and timing with adiposity. Our main findings were that both sleep duration and bedtime were separately associated with BMI, which decreased by 0.40 kg/m2 for each additional hour of sleep duration and increased by 0.37 kg/m2 for each additional hour of bedtime. These effects were higher and stronger with higher BMI values (p75th). Another interesting data was that even when sleep duration and bedtime were adjusted for each other the significance of one of them remained. All these associations were adjusted for gender, age, marital status, education, diet quality, weekly physical activity duration, alcohol use, and smoking. Furthermore, we observed that both short sleep duration and late bedtime were associated with several obesogenic and unhealthy behaviors (eg. lower diet quality, longer screen time before bed, smoking) that may in long-term influence weight gain, obesity [15,19,[33], [34], [35]].

Our observation that sleep duration was negatively associated with BMI is consistent with meta-analyses [5,36], and the magnitudes of the associations that we found are within the ranges of those documented previously [5,6,36]. Also, epidemiologic studies have often associated short sleep with higher energy intake and have sometimes found that short sleep coincides with reduced dietary quality [15,19,35]. Another very interesting finding of our study was that the lowest BMI value was seen in the sleep duration of 8 h/night, which refers precisely to the median of the recommended sleep duration (7–9 h) [29] and is also in agreement to the results of a recent meta-analysis, in which a reverse J-shaped relation between sleep duration and obesity was found, with the lowest risk at 7–8 h sleep per day [5].

Regarding sleep timing, there are several pathways in which late sleep/wake may affect weight regulation. Later sleepers may curtail their sleep, in order to meet occupational or social demands and also may have greater barriers to engaging in healthful diet and exercise behaviors due to competing demands after work and school obligations [19,37]. An interesting study that performed the global quantification of sleep schedules, using smartphone data, identified that country differences in sleep duration were primarily explained by a difference in bedtime [3], pointing to the hypothesis that biological cues around bedtime are either weakened or ignored for societal reasons, thereby leading individuals to delay their bedtime and truncate their sleep duration as a result. Researchers have demonstrated that even sleep timing difference between morning and evening chronotypes is not simply a result of the endogenous circadian rhythm phase differences, but also involves lifestyle and psychological factors in the choice of bedtime and arising time [38,39]. Thus, perhaps due to a mismatch between their preferred schedule and the typical work schedule, individuals with later bedtime may be at greater risk for circadian misalignment, defined as the alteration of sleep-wake timing relative to the endogenous circadian rhythm [[40]; Suwazono et al., 2008 [18]].

Specifically in our study, although bedtime was associated with higher BMI values, independent of sleep duration, late sleepers, in addition to reporting 42 m less sleep compared to early sleepers, reported longer screen time right before bed, which may disturb the sleep-wake cycle, sleep quality and increase the risk of obesity, due to a suppression of melatonin production and disruption of daily rhythms [33,34]. The foregoing suggests that circadian misalignment could be behind the association found between sleep timing and BMI.

Although the observed trend towards higher BMI, as waking-up time increased did not show a statistical association in our study [24], a U-shape association between wake-up time and BMI has been suggested. It seems that waking up too early (eg. ∼4:00), along with poor sleep quality, lack of sufficient sleep, and inconsistent sleep schedules, coincide with stress early in the day, and might increase, by flattening cortisol rhythms, the risk of developing obesity, as well as depression, anxiety, and other stress-related mood disorders [41,42].

There is currently no consensus recommendation about the ideal clock time neither to sleep nor to wake up, however, it can be safely stated that sleep timing, whenever possible, in addition to occurring during the night, should be planned retrospectively according to the required waking-up time, in order to guarantee 7–9 h of sleep and should not imply the concomitant consumption of food during the biological night, as a way to prevent excessive weight gain and other resulting morbidities from circadian misalignment [[21], [22], [23]].

Additionally, bedtime and waking-up times should be consistent and concomitant with the incorporation of other sleep hygiene practices (defined as a set of behavioral and environmental recommendations intended to promote healthy sleep), such as the establishment of a pre-bed routine (eg. relaxing activities ∼30 before bed, dimming artificial lights, disconnecting from electronics) and pro-sleep habits throughout the day (eg. exposure to natural daylight, physical activity, non-smoking, reducing alcohol consumption, cutting down on the caffeine in the afternoon and evening, not eating late dinner) [43].

4.1. Strengths and weaknesses

Our study has a few limitations, starting with the use of self-reported questionnaires which are prone to underreporting (i.e. dietary intake) or misreporting (i.e. bedtime, wake-up time). However, BMI computed from self-reported weight and height is considered a valid measure across different socio-demographic groups [44]. Also, precise questions were used to investigate sleep domains, the questionnaire specified that responses should be based on recent behaviors (last month) and, to guarantee data as close as possible to the real usual behavior, the questionnaire differentiated weekdays (work/study days) and weekends (free days) [45]. In addition, despite our covariate adjustment for sociodemographic, diet-related, and lifestyle traits, we recognize that a general weakness of cross-sectional studies is that the direction of the relationship, and possible pathways of causation, can only be hypothesized. Finally, we recognize as a limitation the absence of energy and nutrient consumption data to assess differences in daily/evening intake between sleeper groups.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, overall, our findings show that, among Brazilian adults, after adjusting for potential confounders, beyond the negative association between sleep duration and BMI, increasing bedtime, independently of sleep duration, BMI increased as well.

In addition to providing the first overview of Brazilian sleep patterns, as well the first investigation of the association between sleep duration and timing with adiposity, insights into the characteristics, obesogenic and unhealthy behaviors related to short sleep and late bedtime may support specific strategies to prevent and treat excess body adiposity and other unfavorable health outcomes.

Finally, our results suggest that beyond sleep duration, sleep timing might be considered to disentangle the sleep-obesity association and point to the need of incorporating sleep measures as part of the medical and nutrition counseling, communication, and research, like many other lifestyle factors that contribute to nutritional health, when examining weight management and health promotion.

[46]

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Giovana Longo-Silva: conceived, designed, and coordinated the research, raised funding, participated in data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, and interpretation, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version, Also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Anny Kariny Pereira Pedrosa: designed the research, participated in, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, and interpretation, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version, Also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Priscilla Marcia Bezerra de Oliveira: designed the research, participated in, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, and interpretation, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version, Also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Jéssica Ribeiro da Silva: designed the research, participated in, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, and interpretation, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version, Also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Risia Cristina Egito de Menezes: designed the research, participated in, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, and interpretation, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version, Also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Patricia de Menezes Marinho: designed the research, participated in, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, and interpretation, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version, Also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Renan Serenini Bernardes: designed the research, participated in, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, and interpretation, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version, Also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Declaration of competing interest

None

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all Brazilians who participated in the SONAR-Brazil survey, as well as the institutions and professionals who contributed to the research dissemination throughout the country.

Contributor Information

Giovana Longo-Silva, Email: giovana.silva@fanut.ufal.br.

Anny Kariny Pereira Pedrosa, Email: dra.annykariny@gmail.com.

Priscilla Marcia Bezerra de Oliveira, Email: prioliveirap9@gmail.com.

Jéssica Ribeiro da Silva, Email: jessicaribeiro.0714@gmail.com.

Risia Cristina Egito de Menezes, Email: risiamenezes@yahoo.com.br.

Patricia de Menezes Marinho, Email: patricia_mmarinho@hotmail.com.

Renan Serenini Bernardes, Email: renan_serenini@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Van Cauter E., Knutson K.L. Sleep and the epidemic of obesity in children and adults. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1530/eje-08-0298. S59–S66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford E.S., Cunningham T.J., Croft J.B. Trends in self-reported sleep duration among US adults from 1985 to 2012. Sleep. 2015;38(5):829–832. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walch O.J., Cochran A., Forger D.B. A global quantification of "normal" sleep schedules using smartphone data. Sci Adv. 2016;2(5) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tse L.A., Wang C., Rangarajan S., Liu Z., Teo K., Yusufali A., et al. Timing and length of nocturnal sleep and daytime napping and associations with obesity types in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Q., Zhang M., Hu D. Dose-response association between sleep duration and obesity risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sleep Breath. 2019;23(4):1035–1045. doi: 10.1007/s11325-019-01824-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potter G.D.M., Cade J.E., Hardie L.J. Longer sleep is associated with lower BMI and favorable metabolic profiles in UK adults: findings from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey. PLoS One. 2017;12(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Y., Zhai L., Zhang D. Sleep duration and obesity among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep Med. 2014;15(12):1456–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taheri S. The link between short sleep duration and obesity: we should recommend more sleep to prevent obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(11):881–884. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.093013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St-Onge M.P., Roberts A.L., Chen J., Kelleman M., O'Keeffe M., RoyChoudhury A., et al. Short sleep duration increases energy intakes but does not change energy expenditure in normal-weight individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:410–416. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.013904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaput J.P., Després J.P., Bouchard C., Tremblay A. The association between short sleep duration and weight gain is dependent on disinhibited eating behavior in adults. Sleep (Basel) 2011;34(10):1291–1297. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reutrakul S., Van Cauter E. Sleep influences on obesity, insulin resistance, and risk of type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2018;84:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaput J.P., Després J.P., Bouchard C., Tremblay A. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin levels and increased adiposity: results from the Quebec family study. Obesity. 2007;15(1):253–261. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmid S.M., Hallschmid M., Jauch-Chara K., Wilms B., Benedict C., Lehnert H., et al. Short-term sleep loss decreases physical activity under free-living conditions but does not increase food intake under time-deprived laboratory conditions in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(6):1476–1482. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandner M.A., Sands-Lincoln M.R., Pak V.M., Garland S.N. Sleep duration, cardiovascular disease, and proinflammatory biomarkers. Nat Sci Sleep. 2013;5:93–107. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S31063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grummon A.H., Sokol R.L., Lytle L.A. Is late bedtime an overlooked sleep behaviour? Investigating associations between sleep timing, sleep duration and eating behaviours in adolescence and adulthood. Publ Health Nutr. 2021;24(7):1671–1677. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020002050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnadas-Solé C., Zerón-Rugerio M.F., Hernáez Á., Foncillas-Corvinos J., Cambras T., Izquierdo-Pulido M. Late bedtime is associated with lower weight loss in patients with severe obesity after sleeve gastrectomy. Int J Obes. 2021;45(9):1967–1975. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00859-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaki N., Fujiwara S., Yamashita H., Ozono R., Monzen Y., Teramen K., Kihara Y. Association between obesity and self-reported sleep duration variability, sleep timing, and age in the Japanese population. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2018;12(2):187–194. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baron K.G., Reid K.J., Kim T., Van Horn L., Attarian H., Wolfe L., et al. Circadian timing and alignment in healthy adults: associations with BMI, body fat, caloric intake and physical activity. Int J Obes. 2017;41(2):203–209. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baron K.G., Reid K.J., Kern A.S., Zee P.C. Role of sleep timing in caloric intake and BMI. Obesity. 2011;19(7):1374–1381. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron K.G., Reid K. Circadian misalignment and heatlh. Int Rev Psychiatr. 2014;26(2):139–154. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.911149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dashti H.S., Gómez-Abellán P., Qian J., Esteban A., Morales E., Scheer F.A., et al. Late eating is associated with cardiometabolic risk traits, obesogenic behaviors, and impaired weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113(1):154–161. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mchill A.W., Phillips A.J.K., Czeisler C.A., Keating L., Yee K., Barger L.K., et al. Later circadian timing of food intake is associated with increased body fat. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(5):1213–1219. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.161588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garaulet M., Gómez-Abellán P., Alburquerque-Béjar J.J., Lee Y.C., Ordovás J.M., Scheer F.A. Timing of food intake predicts weight loss effectiveness. Int J Obes. 2013;37(4):604–611. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zerón-rugerio M.F., Longo-Silva G., Hernáez Á., Ortega-regules A.E., Cambras T., Izquierdo-pulido M. The elapsed time between dinner and the midpoint of sleep is associated with adiposity in young women. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):410. doi: 10.3390/nu12020410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilms B., Chamorro R., Hallschmid M., Trost D., Forck N., Schultes B., et al. Timing modulates the effect of sleep loss on glucose homeostasis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(7):2801–2808. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-02636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckel R.H., Depner C.M., Perreault L., Markwald R.R., Smith M.R., McHill A., et al. Morning circadian misalignment during short sleep duration impacts insulin sensitivity. Curr Biol. 2015;25(22):3004–3010. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. Obesity and overweight. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roenneberg T., Pilz L.K., Zerbini G., Winnebeck E.C. Chronotype and social jetlag: a (self-) critical review. Biology. 2019 Jul 12;8(3):54. doi: 10.3390/biology8030054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohayon M., Wickwire E.M., Hirshkowitz M., Albert S.M., Avidan A., Daly F.J., et al. National Sleep Foundation's sleep quality recommendations: first report. Sleep Health. 2017;3(1):6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melo E.A., Jaime P.C., Monteiro C.A. Primary Health Care Department; 2015. Dietary guidelines for the Brazilian population. Brasília: ministry of health of Brazil. Secretariat of health care; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomes A.P., Soares A.L.G., Gonçalves H. Low diet quality in older adults: a population-based study in southern Brazil. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2016;21:3417–3428. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320152111.17502015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green A., Cohen-Zion M., Haim A., Dagan Y. Evening light exposure to computer screens disrupts human sleep, biological rhythms, and attention abilities. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(7):855–865. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1324878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rybnikova N.A., Haim A., Portnov B.A. Does artificial light-at-night exposure contribute to the worldwide obesity pandemic? Int J Obes. 2016;40(5):815–823. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dashti H.S., Scheer F.A., Jacques P.F., Lamon-Fava S., Ordovas J.M. Short sleep duration and dietary intake: epidemiologic evidence, mechanisms, and health implications. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(6):648–659. doi: 10.3945/an.115.008623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaput J.P., Dutil C., Featherstone R., Ross R., Giangregorio L., Saunders T.J., et al. Sleep duration and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Appl Physiol Nutr Metabol. 2020;45(10):S218–S231. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato-Mito N., Shibata S., Sasaki S., Sato K. Dietary intake is associated with human chronotype as assessed by both morningness-eveningness score and preferred midpoint of sleep in young Japanese women. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2011;62(5):525–532. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2011.560563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lack L.C., Wright H.R. Clinical management of delayed sleep phase disorder. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5(1):57–76. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0501_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wittmann M., Dinich J., Merrow M., Roenneberg T. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(1–2):497–509. doi: 10.1080/07420520500545979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruger M., Scheer F.A. Effects of circadian disruption on the cardiometabolic system. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2009;10(4):245–260. doi: 10.1007/s11154-009-9122-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Safi Z.A., Polotsky A., Chosich J., Roth L., Allshouse A.A., Bradford A.P., et al. Evidence for disruption of normal circadian cortisol rhythm in women with obesity. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018;34(4):336–340. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1393511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams E., Magid K., Steptoe A. The impact of time of waking and concurrent subjective stress on the cortisol response to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(2):139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irish L.A., Kline C.E., Gunn H.E., Buysse D.J., Hall M.H. The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: a review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;22:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodge J.M., Shah R., McCullough M.L., Gapstur S.M., Patel A.V. Validation of self-reported height and weight in a large, nationwide cohort of U.S. adults. PLoS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robbins R., Quan S.F., Barger L.K., Czeisler C.A., Fray-Witzer M., Weaver M.D., et al. Self-reported sleep duration and timing: a methodological review of event definitions, context, and timeframe of related questions. Sleep Epidemiol. 2021;1 doi: 10.1016/j.sleepe.2021.100016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roenneberg T., Wirz-Justice A., Merrow M. Life between clocks: daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J Biol Rhythm. 2003;18(1):80–90. doi: 10.1177/0748730402239679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]