Summary

In health promotion programmes (HPP), it is crucial to have intersectoral collaboration within coalitions and to build networks between health and other societal sectors. A health broker role is recognized as being helpful in connecting the coalition with the broader network, and participatory action research (PAR) is deemed supportive because it facilitates evaluation, reflection, learning and action. However, there is a lack of insight into how processes that affect collaboration develop over time. Therefore, this study aimed to provide insights into the coalition’s processes that facilitate building and maintaining intersectoral collaboration within a HPP coalition and network and how these processes contribute to the coalition’s ambitions. As part of PAR, the coalition members used the coordinated action checklist (CAC) and composed network analysis (CNA) in 2018 and 2019. The CAC and CNA results were linked back into the coalition in five group sessions and used for reflection on pro-gress and future planning. Coalition governance, interaction with the context, network building and brokerage, and generating visibility emerged as the most prominent processes. Important insights concerned the health broker’s role and positioning, the programme coordinator’s leadership and the importance of visibility and trust leading to investment in continuation. The combined research instruments and group sessions supported discussion and reflection, sharing visions and adjusting working strategies, thereby strengthening the coalition’s capacity. Thus, PAR was useful for evaluating and simultaneously facilitating the processes that affect collaboration.

Keywords: intersectoral collaboration, network analysis, health broker, participatory action research

INTRODUCTION

In health promotion, intersectoral collaboration—building and strengthening networks within healthcare sectors and between health and other societal sectors—is increasingly recognized as a core element of implementing a health promotion programme (HPP) (Koelen et al., 2008; Wagemakers et al., 2010b; Corbin et al., 2018). Policy changes in public health, care and social support in recent years have led to intersectoral partnerships and to local-level community engagement becoming even more important (van den Berg et al., 2016). Intersectoral collaboration is defined as ‘a recognized relationship between (parts of) different sectors of society which has been formed to take action on an issue to achieve health outcomes or intermediate health outcomes in a way which is more effective, efficient or sustainable than might be achieved by the health sector acting alone’ (Nutbeam, 1998). Intersectoral collaboration requires the engagement of partners from different sectors, identification of opportunities for collaboration, negotiation of agendas, mediating different interests and promoting synergy (WHO, 2014).

The formation of cooperative networks of mostly non-profit and public organizations is a widespread approach to intersectoral collaboration, especially in health and human services. Within the network structure, community coalitions can be formed to act as effective entities for promoting and facilitating HPPs (Cramer et al., 2006). Thus, by working together, community organizations can draw on the broad range of resources and expertise provided by the other organizations in the network, and, consequently, community members’ health and well-being will be improved (Roussos and Fawcett, 2000; Provan et al., 2005).

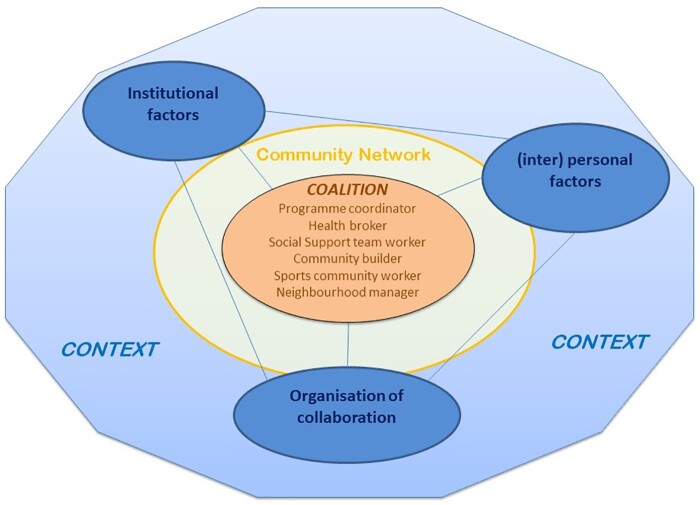

However, collaboration in coalitions and networks can be challenging and does not develop just because it is needed. To build and sustain successful collaborations, several factors that affect intersectoral collaboration are identified in the literature (Cramer et al., 2006; Zakocs and Edwards, 2006; Smit et al., 2015). Koelen et al. (Koelen et al., 2012) defined prerequisites for success in coordinated action for health and combined them in the Healthy Alliances (HALL) framework. Three interdependent clusters—institutional factors, (inter)personal factors and organization of the coalition—are recognized as affecting collaboration. For example, an institutional factor is that organizations have their own philosophy and culture, a personal factor is that people have different backgrounds, knowledge domains, interests and perspectives and an organization factor is that collaboration involves working in a new area and that ambitions need to be defined. Collaboration in a coalition is also influenced by the context, for example the history of the collaboration, experience of partner organizations in working together and political climate (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2009; Kegler et al., 2010; Reed et al., 2014).

A broker role can be helpful in facilitating building and maintenance of networks, for example by exchanging knowledge between stakeholders (Herens et al., 2013; Leenaars et al., 2015; van Rinsum et al., 2017). Brokers can add considerable value to a coalition or network by crossing holes or boundaries, making advice and knowledge more accessible and producing environments in which collaboration can flourish (Long et al., 2013). The benefits of a broker role, especially in health promotion, lie in connecting stakeholders from health and non-health sectors with citizens, and subsequently stimulating an integrated community approach to address health inequities (Harting et al., 2011; Golden et al., 2015).

Participatory action research (PAR) is a favourable approach to both facilitate and evaluate coalition building, as it integrates learning and offers tools for action, reflection, discussion and decision-making (Baum et al., 2006; Koch and Kralik, 2009; Rice and Franceschini, 2007). In PAR, researchers and communities work together with the primary aim of developing actions to address the communities’ priority issues. PAR strengthens community capacity to make positive changes and improves programme sustainability (Jagosh, 2012; Snijder et al., 2020). Besides capacity building, PAR enables those involved to continually optimize their strategies and contributes to the visibility of achievements (Wallerstein and Duran, 2006; Jagosh et al., 2015). For example, regular evaluation and feedback sessions facilitate community coalition’s processes, including collaboration processes, and sustain collective learning and stakeholder enthusiasm (Butterfoss and Francisco, 2004; Wagemakers et al., 2010b; Wijenberg et al., 2019).

A vast body of knowledge exists about the factors that relate to the building and maintenance of intersectoral collaboration in health promotion. Less is known about how coalition’s processes evolve and interact over time, and how they contribute to capacity building in practice. Coalition’s processes are—in line with Nutbeam [(1998), p. 358]—defined as a series of steps taken in order to achieve the coalition’s ambitions. In this study, PAR was applied in a community HPP to explore what these processes entail and to gain a more detailed understanding of the complexity of these processes. By following the coalition and its network over time, it was possible to monitor the processes and the multiplicity of influences at work, and thereby contribute to practice-based knowledge (Green, 2006; Wallerstein and Duran, 2010). Overall, the aim of this study was to provide insight into the processes that facilitate the building and maintenance of (i) intersectoral collaboration within a coalition and (ii) its network in a community HPP and (iii) how these processes contribute to the coalition’s ambitions. Special attention is paid to the broker role in facilitating the intersectoral collaboration and/or coalition processes.

METHODS

Study setting

This study is part of a broader project, the community HPP ‘Voorstad on the Move (VoM)’, with the overall aim of contributing to the improvement of health and to find ways to reduce health inequities in a city district of low socioeconomic status in the Netherlands. Intersectoral collaboration between social services, primary care, policy, public health and community workers is one of the action principles in the HPP approach (de Jong et al., 2019). In the VoM preparatory phase (October–December 2015), an explorative study was performed to ascertain the health situation in the city district and to decide on the programme’s goals and methods. One important finding was the presence of a strong and lively social infrastructure of public, welfare, social support, sports and care organizations, community centres and (informal) networks in which both professionals and inhabitants collaborate (de Jong and Roos, 2016).

In June 2016, programme VoM started with five organizations, all part of the existing social infrastructure: the municipal health service, the Social Support team Voorstad, the welfare organization, the neighbourhood viability coalition and the local Sports Service organization. The VoM coalition, a group of six persons, was formed, in which the five organizations were represented along with a health broker, who was an inhabitant of VoM, working self-employed. This coalition was the programme’s driving and leading force until the end of the funding term, December 2019. The coalition members built a communitywide network of organizations, workers and inhabitants based on the existing social infrastructure and the contacts that each of them brought in. At the start of the VoM programme, coalition members formulated three ambitions (a, b, d), in relation to the overall aim of the HPP. In March 2018, three more ambitions (c, e, f) were added, resulting from a mid-term programme evaluation. Together with the researchers, of whom one was part of the coalition, the main indicators (measured concepts) and the related research methods and instruments were formulated (Table 1). Ambitions a and b provide insight into the processes that facilitate intersectoral collaboration within the coalition, ambition c into the coalition’s network, and d, e and f into the processes that contribute to the ambitions. In addition, ambitions b and c also provide insight into the broker role.

Table 1:

Coalition’s ambitions, indicators, research methods and instruments

| Coalition’s ambitions | Main indicators | Research methods | Research instruments |

|---|---|---|---|

| a. To strengthen intersectoral collaboration in the coalition between: social support team, welfare, local sports service, public health service, neighbourhood viability and health broker. |

|

|

CAC |

| b. To clarify roles and tasks of coalition’s members, specially within the coalition, specifically the broker role. |

|

|

CAC |

| c. To expand the coalition’s network with other organizations and inhabitant (groups), supported by the health broker. |

|

|

|

| d. To realize health promotion activities that fit in or connect with existing programmes and activities. |

|

Document analysis of minutes of coalition meetings and reports of activities | |

| e. To enlarge visibility of the programme and activities. | Visibility of achievements |

|

|

| f. To make the programme sustainable in policy and practice of the municipality and collaborating partners. |

|

|

|

Study design

Intersectoral collaboration in the VoM programme was studied from the perspective of the HALL framework (Figure 1). From this perspective, building and maintenance of intersectoral collaboration in a HPP is viewed as a dynamic process. The framework shows that collaboration within the coalition and its network was mutually affected by institutional factors, (inter)personal factors and the organization of the collaboration, together with the interaction of the context.

Fig. 1:

The HALL framework. Adapted based on Koelen et al. (2012).

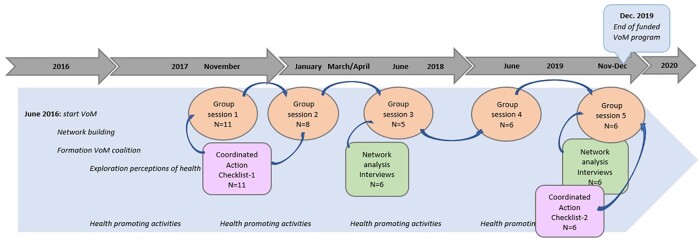

The programme was implemented using PAR with the aim of both facilitating and evaluating the HPP (Koelen and van den Ban, 2004). Discussion and reflection on the ongoing programme processes, in particular the collaboration within the coalition, building and sustaining the broader network and the health broker role occurred in five separate group sessions with the coalition members at their regular project meetings (Figure 2).

Fig. 2:

Timeline with research activities embedded in the VoM programme.

At three junctures, November 2017, March–April 2018 and November 2019, specific research instruments—the coordinated action checklist (CAC) and the composed network analysis tool (CNA)—were applied to measure collaboration within the coalition and to map the network of coalition members, respectively. The results of these measurements were input for four of the five group sessions. The fourth group session, in June 2019, was an evaluation session, part of the overall FNO evaluation study with the action points of the preceding sessions as input (Hogeling et al., 2019). Conclusions and recommendations resulting from the sessions were used to adjust the participants’ working methods and activities. The duration of the group sessions varied from 48 to 98 min.

Coordinated action checklist

The CAC—based on the HALL framework (Koelen et al., 2012)—was used twice to discuss and evaluate the collaboration and to make results visible (Wagemakers et al., 2010a). The main CAC topics are partners’ suitability, task dimension, relationship dimension, growth dimension and profiling, consisting of 25 items, presented as statements. Respondents were asked to rate their degree of consent/agreement regarding each statement on a 5-point scale. For this study, two items were added relating to the health broker role, namely, the health broker functions to full satisfaction and the positioning of the health broker within the collaboration works well. In addition, one item evaluating the preconditions of the collaboration was added. Two items were removed from the original checklist, as these items were covered by the CNA.

The final checklist included 26 items. In November 2017, a group of 11 respondents (nine VoM partners, a health broker and the project coordinator) completed the CAC on paper. The CAC checklist scores were calculated per item and per topic. The scores per item were calculated by adding the scores of all partners together and dividing the total score by the number of partners. The topic score was calculated by adding the average of the total item scores, then dividing that by the number of items in that topic. Item and topic scores ranged from 0 to 100.

The CAC results were presented and used as input for the discussion in group sessions 1, 2 and 5. In the first group session, respondents were asked to explain their personal scores and what they considered collaboration success factors. The second group session with eight participants, which took place in January 2018, was a continuation of the first session. Again, the CAC results were discussed; in particular, the high scores (above 80) and the low scores (below 60) were highlighted. The discussion focused on a shared vision and working strategy, specific actions needed to improve the collaboration and the VoM activities plan 2018.

Two years later, in November 2019, the checklist was administered again, expanded with four items about ‘continuation’, ending up with a list of 30 items. The members of the coalition (n = 6) completed the CAC online. In Group session 5 (November 2019), the coalition members discussed the results of the second CAC measurement, together with the composed network results. The focus of that session was on the continuation of the HPP and the coalition after the programme term had ended.

Composed network analysis

In March/April 2018, an extended network analysis was conducted. The CNA method, developed for this study from a literature review (Tijhuis 2018), uses a combination of different methods, like network drawing, interview, questionnaire and group sessions (Pluto and Hirshorn, 2003; Provan et al., 2005; Cross et al., 2009; Schiffer and Hauck, 2010; Yessis et al. 2013; Wijenberg et al., 2019). This CNA method was derived from the social network analysis (SNA) approach, which describes and analyses interactions among a defined set of actors. It regards social relations as more powerful than individual attributes in explaining social phenomena (Marin and Wellman, 2011). One of the CNA outputs is a network map, in which actors or units are called nodes, and the connections are the ties between nodes. The relationship or tie is a flow of resources that can include social support, time, information, money and shared activity (Marin and Wellman, 2011).

The first step of the CNA method is to draw the network with the coalition members (P1–P6). The drawing was conducted with each participant individually, as individual visualizations and evaluations of the network were expected to be more effective. Schiffer and Hauck’s (Schiffer and Hauck, 2010; Karn et al., 2017; Rasheed et al., 2017) drawing method, which utilizes ‘influence towers’, was used. During and after the drawing of the network, a semi-structured interview was conducted by a researcher (Y.T.), reflecting on the results. First, the respondent listed all actors in his/her network on post-its and stuck them on a map with the respondent in the centre. Subsequently, relations between the actors were drawn, and respondents were asked to define their influence by putting influence towers beside the actors, literally a tower of fiches. The question was: ‘How strongly can these actors influence the coalition’s ambitions?’ Thus, the respondents evaluated their networks and the quality of the collaboration with each actor. The interviews, with the drawing process included, took between 85 and 120 min, with an average of 92 min. NetDraw, part of the UCINET program, was used to visualize the results of the network mapping by drawing a complete network map (Cross et al., 2002). A network map of the VoM coalition was composed by putting all actors mentioned together. Coloured nodes were used to distinguish different actor-groups, namely, local government (orange), organizations (blue), inhabitant (groups) (rose), research (yellow), trained volunteers (purple) and the VoM coalition (green). The lines in the network map represent a direct relation from a coalition member to an actor. The important actors in the network are highlighted by an increased node size.

Group session 3 was held with five coalition members in June 2018 to discuss the results of the network drawings and the questionnaires. The composed network map of all coalition members together was input for the discussion and conclusions, and points for improvement and action were determined.

In November 2019, another network analysis was conducted with the then coalition members. Using the 2018 network maps, the respondents were asked to draw their network by going through all the actors that they had mentioned in 2018 and indicating any changes. As building the influence towers was very time-consuming, this time, each respondent was asked to indicate his/her five most influential actors by circling their names, resulting in 21 important actors in the 2019 composed network map.

The network drawing was part of a semi-structured interview with each coalition member individually, in combination with questions about the sustainability of the collaboration. The CNA results were evaluated and discussed in Group session 5, together with the results of the second CAC measurement. The focus of that session was on the achievement of the coalition’s ambitions and the continuation of the coalition and health promoting activities after the end of the programme.

Overall data analysis

The overall analysis consisted of an integration of the data generated by the research tools (CAC and CNA) and qualitative information from the interviews, group sessions, minutes of the coalition meetings and reports of activities. The integration was focused on the processes that facilitated the building and maintenance of intersectoral collaboration, using the results of the measurement instruments at two junctures and the transcripts from the interviews and the group sessions. Reports of meetings, activities and interviews were consulted to determine the achievements resulting from the collaboration.

A thematic content analysis approach was applied to the transcripts of the individual interviews and the group sessions, guided by the CAC topics and supported by Atlas-ti 8.4. Two researchers (M.d.J. and Y.T.) performed this analysis, which involved open, axial and selective coding. Each researcher read, marked and coded (open coding) a number of interviews and group sessions. Researcher Y.T. did the first coding of the 2017 and 2018 measurements and M.d.J. the 2019 interviews and group session. Then, all the researchers compared the codes, discussed the differences and reached consensus on the codes used. The coding of the 2019 transcripts was held to be decisive, and consensus was reached readily.

RESULTS

Achievements resulting from the collaboration in the VoM coalition

The coalition’s ambition was to realize a coherent set of health promoting activities that fit in or connect to already existing social programmes and running activities in the community. Also, ambitions on collaboration and network development, organization of the collaboration, including visibility and sustainability were defined and pursued. Table 2 presents the achievements for each of the six ambitions (a–f).

Table 2:

Achievements resulting from collaboration within the coalition and with its network

| Coalition’s ambitions | Achievements |

|---|---|

| a. To strengthen intersectoral collaboration in the coalition |

|

| b. To clarify roles and tasks of coalition members, specifically the broker role |

|

| c. To expand the coalition’s network |

|

| d. To realize health promoting activities, initiated by and/or involving inhabitants |

|

| e. To enlarge visibility |

|

| f. To make the programme sustainable |

|

Strengthen the collaboration within the coalition

All scores on the dimensions measured with the CAC improved over time, with especially high scores on partners’ suitability, the task dimension and the relation dimension (See Appendix with CAC scores in 2017 and 2019).

Coalition members agreed that, from the start, the right partners were represented in the coalition. In both measurements, the ‘partners’ suitability’ score was good and increased (respectively, from 78 to 93). The statement ‘the contribution of the different partners is to everyone’s full satisfaction’ (item 4) received a low score (43) initially and improved strongly to a score of 100 two years later. Also, the statement ‘I feel strongly involved in this coalition’ (item 7) ended up with a maximum score of 100. The coalition members explained that the low score in 2017 resulted from the absence of a clear mission and vision for VoM and uncertainty about the division of roles and tasks. Lots of discussions arose about the mission, ambitions and planning of the VoM programme, and disagreement on a workable division of roles and tasks was noticed.

…. I am missing, and that is what I already indicated in November (2017), I am missing a little bit, a mission and a vision about where are we working towards in 2018, and that is what I need to stay committed to the programme. (P5, session 2)

The programme coordinator took the lead in clarifying roles and tasks, confirming decisions, and composing a working plan for the years 2018 and 2019 together with the members, and this proved to be very helpful. In 2019, in the fifth group session, discussing the second measurement, coalition members reported that they had reached clarity and agreement on roles and tasks.

From the beginning, the conditions for the existence of the collaboration were not satisfying (item 13) and did not improve over time (scores 50 in 2017 and 54 in 2019); this is attributable to organizational and policy choices, like management of the social support team, limited time and budgets available. Although coalition members struggled to get permission from their organizations to spend time at project meetings, tasks and consequent actions in working time, the coalition members are personally dedicated to the collaboration.

For me, the programme got a fixed number of hours a week, as part of my total working hours. (….) So, the collaboration is not my main task, like it is for the other coalition members or the welfare workers, they are really neighbourhood based. (P4, session 5)

In 2018, one of the core organizations decided to convert from its membership by rotation, into two members being permanent part of the VoM coalition. From then on, a solid group formed the coalition and had regular meetings facilitated by the coordinator, and initiated and facilitated activities together. This scenario created togetherness and personal commitment to the coalition’s ambitions on which they were working, as reflected in the scores on the relation dimension (from 59 to 93). Three items, open communication, willingness to make compromises, and loyalty to implement decisions and actions (items 14, 16, 18), even got a maximum score of 100.

I can look back on the team with warm feelings now. We had such struggles in the beginning, like: who are you, as a public health advisor to tell us what should be done in this neighbourhood, you know, that attitude. Why is the health broker role not part of the social support team? Well, we have had a lot of fights, conflict, and confrontations about this in our meetings, it chafed every now and then. And now, I realise, hey, it does not chafe anymore, we complement one another, we make beautiful one-two punches. (P5, session 5)

The importance of knowing one another personally, and having shared ambitions and joint activities, became visible when members of the group left or were absent for a long time, because of illness or changing jobs. The new members fitted in easily and took up their roles without much discussion.

Clarify roles, tasks and the broker role

The respondents were moderately positive about the health broker in 2017, with an average score of 60 on the CAC. As an explanation of the low scores, coalition members mentioned the uncertainty about this newly created function and the fact that the health broker, specially appointed within the VoM programme, was not employed by an organization. This caused confusion and a lot of discussion about division of tasks and responsibilities in relation to the other coalition members, which have broker roles as well, arising from their core functions.

I do not consider my contribution (to the VoM coalition) as my core task, let’s say. But, making connections, yes for me it is very clear, that is what I do, so I euh, I find it difficult to say if that is part of my core task, my responsibility, or the project its responsibility, or the health broker’s who has fixed hours for it. (P6, session 1)

To create clarity about roles, tasks and responsibilities, in the second group session—spring 2018—decisions were made regarding the health broker role. The broker role was no longer reserved for the person appointed as health broker. Other coalition members also took up broker tasks, for example connecting inhabitant groups with (health) professionals and supporting groups in organising activities, facilitated by the programme’s budget. This change in who should fulfil the broker role is reflected in the network maps, showing a shift in contacts from the health broker to other coalition members (social support team worker, community builder and neighbourhood manager). The coalition members were convinced that a health broker role was crucial to enable the continuation of the VoM programme after the funding had ended.

Both the positioning and the functioning of the health broker had improved during the programme, ending up with a mean score of 75 (items 19, 20) in 2019. In order to assure sustainability, the health broker role had to be transferred from being a ‘free player’s’ task to being a task for a collaborating organization.

At a certain moment, it will fade out. So, the contacts that have arisen between workers, but also between workers and inhabitants, that well, that will still need something like a booster, a connector, for example such as a broker, who could do that. (P1, session 5)

Expand the coalition’s network

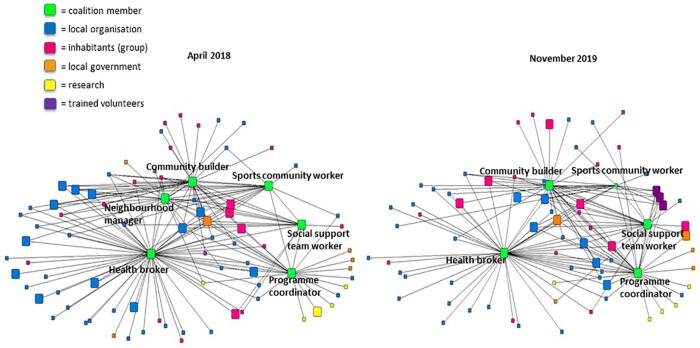

The network analysis, conducted twice at 1.5-year intervals, resulted in two composed network maps of the VoM coalition (Figure 3).

Fig. 3:

Network maps April 2018 and November 2019.

The composed network maps revealed useful information about the extent and diversity of the actors in the network, central (important) actors and missing actors. The coalition consisted of six members (green nodes), from whom the health broker and the community builder had the highest number of contacts. Central actors mentioned by all the respondents were inhabitant groups (rose nodes), welfare workers/child workers (blue nodes) and the community centres (also blue), referred to as important meeting points and facilitators of social and health promoting activities.

What strikes me is that, when you look at the community centre nodes, we put much of our effort into them to strengthen these powerful places. (P6, session 3)

Overall comparison of the 2018 and 2019 network maps shows that the total number of actors did not change much. The neighbourhood manager was no longer an official member of the coalition, but still closely connected (from green to orange). The importance of the sports community worker diminished and some other representatives had disappeared. Also, new and important partners joined the network, for example trained volunteers (purple nodes). Overall, coalition members indicated that the number of relations had not increased over time, which might be due to the coalition’s agreement in 2019 to focus on consolidation and continuation of the programme after the funding period and on supporting inhabitants and workers in sustaining successful activities. This change in focus is also illustrated by the differences in the importance rating of actors, from mostly organizations, welfare workers and community centres to community groups, volunteers/inhabitants, a general practitioner and municipal policy officers by the end of 2019.

In 2018, the primary schools in the city district were viewed as missing actors, because they could and should be important partners in the network to contribute to the programme’s goals. Only the health broker had mentioned them as contacts, adding, however, that meeting frequency was low (small blue nodes). The Turkish inhabitants living in the neighbourhood were another missing actor group. There were no direct relations with Turkish individuals or groups, only indirectly through colleagues.

No, that is what I see as well, but what I also see is the difficulty to sometimes involve these groups of Turkish people, let’s say, so that is what we experience as well from our working method in the neighbourhood. (P8, session 5)

Group session 3 resulted in the following agreements and actions: intensify the relations with the primary schools; find ways to contact the Turkish inhabitants, especially the elderly; involve the aldermen and policy officer in the programme’s network; align the relations with the welfare workers and the welfare organization; and sustain and strengthen the relationship with the neighbourhood manager and the community centres. Despite the intention to intensify the contacts with the neighbourhoods’ primary schools and with the Turkish inhabitants, they still did not feature on the 2019 network map.

Up to 2018, the municipality (orange nodes) was not a central actor, although there were some contacts with local government officials. These relations were distant, and there was no relation with the responsible alderman.

Those are striking results from the network analysis, oh yes, we just did not involve the municipality enough. And why not? That is because we just are very modest about Voorstad on the Move. (P5, session 5)

Because the respondents considered the municipality a very important actor for the continuation of the programme, as it is responsible for local public health and welfare and social support policies, they made extra efforts to get the alderman and the policy officer more involved in the network. By the end of the programme term, the alderman and the policy officer were indicated as important actors and were involved in the coalition’s network.

Realize health promoting activities

A wide range of health promoting activities (physical activity groups, mental health courses, supportive peer groups, mothers’ meetings, education and individual coaching) were implemented as part of VoM together with network contacts and coordinated by the coalition. Adding the participation figures of all the activities together reveals that about 350 inhabitants attended one or more of these activities between 2017 and 2019.

All respondents mentioned that organizing these health promoting activities together, strengthened the collaboration between the various organizations in the coalition and with the new and existing connections in the broader network. Together with the (action) research activities, professionals from different sectors outside health learned about the inhabitants’ perceptions on health. This contributed to a shift in thinking, and, as a result, community workers and organizations got a broader view on health and embraced the health and behaviour approach (instead of illness and cure).

And now we have health much more in our sights. And I think that is nice, because we did not have it that way in my organisation. (P8, session 5)

Enlarge visibility

Visibility had a low score (55) in 2017 and showed only a small improvement in 2 years, to a score of 64 in 2019. Reflecting on the last 2 years of the programme, the coalition explained the low scores by pointing out their modesty, having an internal orientation and not taking enough advantage of their network contacts.

… and, that we were very modest about what we were working on, and had accomplished. Then some follow-up actions came up, because yes, we had to put our project on the political agenda, and achieve some more visibility. (P5, session 5)

While considerable time was spent on the collaboration process, hardly any visible results appeared in the first 2 years of the project. Only in the last year of the VoM programme did the coalition members consider the activities that had resulted from their collaborative efforts as successes, worth being made visible. They started to feel the urge to increase their visibility in order to gain the support of their organizations and the local government for the continuation of the coalition and the VoM programme.

To make the programme sustainable

The CAC continuation topic, with four statements that were especially added to the questionnaire for this study, ended up with a mean score of 79 by the end of 2019 and were discussed in group session 5. On the one hand, the respondents were very positive about their personal motivation to stay involved in the VoM coalition (item 30, score 100). On the other hand, they had little confidence in its continuation without extra funding (item 27) and the support of their organizations and the municipality. The coalition members expressed their concern, in particular about the facilitation of collaboration in the coalition and the funding of the health broker role and health promotion activities. For that, besides an external budget and policy support, contacts with the ‘right’ influential persons within the municipality were needed.

Well, yes, I do miss, especially for continuation, a good connection with the municipality. And that is with the team managers as well as policy-based, the one that has responsibility for the social support teams. So, with the workers it is fine, but these workers themselves are not able to take care of the continuation, of the organisational embedding. (P1, session 5)

Thus, they agreed on the necessity of having a leading professional or coordinator for a sustainable collaboration (item 29). This coordinator role entails responsibility for the organization of the coalition, and is needed in addition to the health broker role that is outward oriented in connecting the coalition with its network.

Well, the vulnerability is in the fact that we have meetings with the coalition every three or four weeks, and even if an agenda is missing, there will be enough points to discuss. But, imagine there will be no scheduled meetings, then you have to arrange moments to meet and to be reminded of the project and to think Oh, yes, this or that needs attention. (P7, session 5)

The involvement of the municipality, resulting in a so-called bridging budget, was credited to the coalition. This financial commitment had to be invested in sustainable health promoting activities, continuation of the coalition and finding ways to institutionalize the health broker role to support the community health promotion approach.

Identified processes that facilitate intersectoral collaboration

Summarizing, the most prominent processes that facilitate intersectoral collaboration within the coalition, with the coalition’s network, and that contribute to the coalition’s ambitions are listed in Table 3. These processes are further elaborated on in the discussion.

Table 3:

Summary of processes that affect intersectoral collaboration

| Process | Facilitated by |

|---|---|

| Governance of coalition |

|

| Network building and sustainment |

|

| Generating visibility |

|

| Interaction with context |

|

DISCUSSION

This study has revealed more detailed insights into the processes that facilitate building and maintaining intersectoral collaboration within a coalition and its network in a community HPP over 2 years. Those insights concern the most prominent coalition’s processes: ‘governance of the coalition’, ‘network building and the health broker role’, ‘generating visibility’ and ‘interaction with the context’. The research instruments integrated in PAR and adapted to the coalition’s context, proved useful for evaluating the collaboration and helped coalition members and researchers to recognize the processes and act upon them. Moreover, this study focused on the processes, thereby making visible the coalitions’ ambitions and achievements.

Governance of the coalition

The programme coordinator was essential to govern the internal organization of the coalition and to enhance coalition capacity. A clear governance of the coalition, by defining a shared vision and clarifying the division of roles, convinced the collaborating organizations to commit to the coalition and to facilitate their employees with time to attend meetings and for programme activities. The programme coordinator’s leadership—which stimulated personal involvement—and togetherness in the coalition was decisive in holding the coalition together, which was also found in other studies (Cramer et al., 2006; Fawcett et al. 2010; Corbin et al., 2018). The group sessions that were part of practice and research helped the members to reflect and take time to discuss the results, share visions and adjust their working strategy, thereby strengthening the capacities of individual members and the coalition as a whole.

Network building and health broker role

The coalition’s network evolved relatively easily, because it could be built on the existing infrastructure in the city district and each individual member of the coalition brought in his/her contacts. Brokerage, in this study not performed exclusively by the appointed health broker, was essential in connecting the coalition with the broader network. The network analysis helped the coalition members to clarify the health broker role and other roles and tasks, and to make decisions about the division of responsibilities. In line with other studies, it was concluded that embedding the health broker(s) in a professional organization was the preferred way to foster the acceptance of the health broker role in the coalition as well as in the broader network (Harting et al., 2011; Long et al., 2013).

Generating visibility

Through the network of new and existing contacts, a range of health promoting activities were implemented, arising from citizens’ ideas and wishes. Only in the third year of the HPP did awareness of the coalition’s achievements grow, thanks to the PAR activities, especially the CAC and the reflection meetings. Subsequently, the coalition members paid more attention to the visibility of the achievements, resulting in a growing appreciation of their own efforts and the feeling of involvement of the members in the coalition. This strengthened the capacity within the coalition and encouraged investment in the continuation of the HPP by gaining local government support and the commitment of the organizations involved. The value of the coalition and its activities was acknowledged, indicating that coalition capacity, like other researchers found, can induce changes in local policy decisions, commitment, and readiness to invest in health promotion (Cacari-Stone et al., 2014, Jagosh, 2012; Anderson-Carpenter et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2017).

Interaction with the context

This study elucidated the interaction between the collaboration and the context, showing not only the importance of taking into account the changing context in studying intersectoral collaboration, but also the power of the coalition to influence the context (Kegler et al., 2010; Reed et al., 2014).

The context of the VoM coalition had important advantages, such as the history of collaboration in the city district and community engagement that helped the coalition members to build the network in a relatively short time. However, the (policy) context in which the VoM programme was implemented was unstable because of transitions of policy responsibilities from the national to the local government (van den Berg et al., 2016). Coalition members were confronted with cutbacks, uncertainty and tasks in their own organization that diverted attention from collaboration in the beginning. Later on, the action research clarified the contextual influences, making it possible to discuss, reflect and subsequently (re)act and learn from it.

Achievements

In practice, the particular processes described evolved simultaneously and interacted mutually, concurrently resulting in observed and visible achievements. Besides achievements that were expected beforehand, such as health promoting activities and a strengthened community network, unexpected achievements resulted from the collaboration, for example the professionals’ broader view on health and local government involvement. Observation and discussion about the achievements have contributed to commitment to, and continuation of, the coalition, as is required to realize community change and the desired health outcomes in the long term. We agree with Butterfoss and Francisco, that to evaluate coalitions (Butterfoss and Francisco, 2004), it is recommended to focus on the achievements and short-term successes, as well as on processes affecting the collaboration.

Reflection and recommendations for using PAR in practice

As has become clear, PAR facilitated reflection and learning through a continuous process of dialogue. It was convincingly demonstrated in this study that PAR proved useful for evaluating the collaboration and helped coalition members and researchers to recognize the processes and act upon them. At the same time, while focusing on the processes, the research helped to make achievements visible.

Both research instruments, the CAC and the CNA, provided different information and complemented each other. The application of the CAC offered good opportunities for evaluating and discussing upcoming issues, thereby improving the collaboration (Wagemakers et al, 2010a). The (extended) network analysis (CNA), which was especially composed for this study based on a literature review (Tijhuis, 2018), was a very complete method, but appeared to be time-consuming and difficult to use in practice. Therefore, it was simplified in the second measurement, which might have resulted in a too low number of identified actors in the network. In addition, the identified actors were not asked for their input, a missed opportunity to engage these actors and the organizations they represent. Still, the network analysis has proven its worth by visualizing the variety and the influence of actors according to the coalition members and by comparing the actual situation with the map of the situation 1.5 years ago. Altogether, the combination of instruments, with in-depth evaluation sessions of the collaboration can be seen as capacity-building method, facilitating coordinated action.

Using PAR has added value, because it adapts to the particular situation in practice and always takes into account the perspectives of the persons involved. In this study, the insights into the processes concern just one case—the VoM programme—which is a strength and a limitation (Flyvbjerg, 2006). On the one hand, it created a thorough understanding of the processes that evolved simultaneously and interacted mutually in a real-life situation. On the other hand, it may be hard to generalize the findings, because every HPP has its own characteristics and is implemented in a different context. In order to gain broader insights into the processes that are generalizable and those that are context specific, more practice-based studies are needed.

Notwithstanding, some interesting recommendations for research and practice emerged from this study.

The research activities were time consuming for coalition members and programme coordinator. Along the term of the VoM programme, the focus was mostly at the internal processes of the coalition. This may have hindered a more outside-oriented view of the coalition, resulting in less attention for the visibility of programme activities and achievements in the broader network of the coalition, one of the coalition’s ambitions. At the same time, coalition members appreciated participating in the research activities, because it gave them more insight into the emerging processes and they got to know each other better. Eventually, this resulted in a strengthened collaboration and ample attention paid to the visibility of the programme’s activities and achievements outside the coalition in the last year of the programme.

The role of the action researcher is challenging, because it requires flexibility and a broad range of competences. In our study, the action researcher coordinated the programme and was a member of the coalition. The researcher took part in the coalition meetings and managed to gain the trust of the coalition members, which made them willing to participate in the research activities. At the same time, the researcher had to monitor the processes and to report on the programme. Next to flexibility, communication and social skills and competences that relate to self-reflection, conflict management and perseverance are required (Wagemakers, 2010).

In PAR, practice and research are closely related, which results in a dual role of researcher and health promotion professional (Lezwijn, 2011). The action researcher/programme coordinator must be clear about these different roles and have the flexibility to change roles when needed. It is recommended that in HPP’s accompanied by PAR, both research and practice need to justify the dual role, health promotion professionals need additional research competences and researchers should become more familiar with challenges of health promotion practice.

CONCLUSION

The added value of this study is that it revealed more detailed insights into the processes that facilitate the building and maintenance of intersectoral collaboration in the setting of a community HPP. By following the coalition, including the health broker, during a 2-year period, we gathered insights on the coalition’s processes that evolved over time. Above, we convincingly demonstrated that PAR proved useful for evaluating the collaboration and helped coalition members and researchers to recognize the processes and act upon them. At the same time, while focusing on the processes, the research helped to make achievements visible.

In-depth insights into the processes and the interdependence between them helped the community workers and researchers to optimize their working strategies and strengthened the coalition’s capacity. The particular processes described evolved simultaneously and interacted mutually, concurrently resulting in visible outputs. Making the achievements, some unexpected, visible contributed to the commitment and continuation of the coalition, as is required to realize community change and desired health outcomes in the long term. Accordingly, PAR and the integrated research instruments—adapted to the coalition’s context—were useful for evaluating and simultaneously facilitating the processes that affected the collaboration and for determining the short-term achievements. Additional practice-based studies are required to gain broader insights, especially to distinguish between generalizable and context-specific processes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all those involved in this study: the respondents, members of the VoM coalition, volunteers at the neighbourhood centre and employees of the welfare organization.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The project proposal was reviewed and approved by the Social Sciences Ethics Committee (SEC) of Wageningen University and Research. The Committee concluded that the proposal dealt with ethical issues in a satisfactory way and that it complied with the Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (Date 18 October 2018). Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis, could withdraw at any point, and were fully informed about the research activities. Participants signed a written consent to participate in the study. All individual interviews and group sessions were recorded after participants gave verbal permission.

FUNDING

This study was made possible by external financing from a Dutch wealth fund for health, quality of life and future perspectives, called ‘FNO-Zorg voor kansen’ (fnozorgvoorkansen.nl).

APPENDICES

Appendix:

Item and cluster scores Coordinated action checklist 2017 and 2019

| Items and dimensions of coordinated action checklist | Nov 2017 (n=11) |

Nov 2019 (n=6) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. The collaboration is an asset for health promotion | 89 (19.6) | 96 (10.2) |

| Suitability partners | 78 (16.3) | 93 (5.7) |

| 2. To realise the goals of the collaboration, the right people are involved | 75 (22.4) | 71 (24.6) |

| 3. Equity of the partners is essential for good collaboration | 93 (11.1) | 96 (10.2) |

| 4. The contribution of the different members is to everyone’s full satisfaction | 43 (15.4) | 100 (0.0) |

| 5. I have a special interest in participating in this collaboration because of my position or organisation | 98 (7.2) | 100 (0.0) |

| 6. I can contribute to the collaboration in a satisfactory way (time, resources, etc.) | 77 (22.5) | 88 (20.9) |

| 7. I feel strongly involved in this coalition | 75 (31.6) | 100 (0.0) |

| 8. I can contribute constructively to the collaboration because of my expertise | 82 (28.4) | 100 (0.0) |

| Tasks dimension | 62 (14.2) | 85 (10.5) |

| 9. There is agreement among the members about mission, goals, and planning | 45 (14.4) | 92 (12.9) |

| 10. The collaboration achieves regular (small) successes | 77 (16.7) | 100 (0.0) |

| 11. The coalition functions well (working structure, methods) | 57 (28.4) | 96 (10.2) |

| 12. The collaboration evaluates progress in the interim and, if necessary, makes adjustments | 80 (24.5) | 83 (25.8) |

| 13. The conditions for the existence of the collaboration are satisfying | 50 (27.4) | 54 (33.2) |

| Relation dimension | 59 (4.8) | 93 (5.1) |

| 14. The coalition members are open in their communication | 55 (27.8) | 100 (0.0) |

| 15. The project partners work together in a constructive manner and know how to involve one another when action is needed | 60 (22.9) | 83 (20.4) |

| 16. The coalition members are willing to make compromises | 61 (26.9) | 100 (0.0) |

| 17. Within the collaboration conflicts are dealt with in a constructive way | 53 (23.6) | 83 (20.4) |

| 18. The coalition members are loyal in implementing decisions and actions | 66 (16.1) | 100 (0.0) |

| Health brokers | 60 (2.1) | 75 (28.5) |

| 19. The health brokers function to full satisfaction | 63 (28.0) | 79 (18.8) |

| 20. The positioning of the health brokers within the collaboration works well | 58 (26.4) | 71 (40.1) |

| Growth dimension | 74 (3.7) | 85 (12.3) |

| 21. The collaboration is prepared to recruit new partners in the course of time | 78 (24.8) | 79 (18.8) |

| 22. The collaboration succeeds in mobilising others for its actions | 70 (23.4) | 88 (20.9) |

| Visibility | 55 (8.4) | 64 (10.0) |

| 23. The collaboration accurately maintains its external relations | 43 (19.5) | 67 (12.9) |

| 24. The collaboration is seen by external partners as a reliable and legitimate actor | 58 (27.5) | 63 (13.7) |

| 25. The collaboration has a good image in the outside world | 55 (24.5) | 67 (12.9) |

| 26. The coalition takes care of the continuation after the funding of the VoM program ends | 66 (26.7) | 58 (12.9) |

| Continuation (2019 measurement) | - | 79 (7.6) |

| 27. When the external funding stops, this collaboration will continue to exist | - | 63 (20.9) |

| 28. The sustainability of this coalition is on the agenda (of several structures) | - | 71 (24.6) |

| 29. A sustainable coalition needs a good coordinator or leader | - | 83 (20.4) |

| 30. I am personally motivated to contribute to the VoM coalition after 2019 | - | 100 (0.0) |

REFERENCES

- Anderson-Carpenter K. D., Watson-Thompson J., Jones M. D., Chaney L. (2017) Improving community readiness for change through coalition capacity building: evidence from a multisite intervention. Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 486–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum F., MacDougall C., Smith D. (2006) Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 854–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L. D., Wells R., Jones E. C., Chilenski S. M. (2017) Effects of sectoral diversity on community coalition processes and outcomes. Prevention Science, 18, 600–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss F. D., Francisco V. T. (2004) Evaluating community partnerships and coalitions with practitioners in mind. Health Promotion Practice, 5, 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss F. D., Kegler M. C. (2009) The community coalition action theory. In DiClemente R., Crosbie R. A., Kegler M. (eds), Emerging Theories in Health Promotion and Practice, 2nd edition, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 237–277. [Google Scholar]

- Cacari-Stone L., Wallerstein N., Garcia A. P., Minkler M. (2014) The promise of community-based participatory research for health equity: a conceptual model for bridging evidence with policy. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 1615–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. H., Jones J., Barry M. M. (2018) What makes intersectoral partnerships for health promotion work? A review of the international literature. Health Promotion International, 33, 4–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer M. E., Atwood J. R., Stoner J. A. (2006) A conceptual model for understanding effective coalitions involved in health promotion programing. Public Health Nursing, 23, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross R., Borgatti S. P. and, Parker A. (2002) Making invisible work visible: Using social network analysis to support strategic collaboration. California Management Review, 44, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cross J. E., Dickmann E., Newman-Gonchar R., Fagan J. M. (2009) Using mixed-method design and network analysis to interagency collaboration. American Journal of Evaluation, 30, 310–329. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M. A. J. G., Roos G. (2016) Startfoto Gezond in Voorstad [Starting picture healthy in Voorstad]. http://www.samengezondindeventer.nl/projecten/voorstad-beweegt/ (last accessed 6 November 2019).

- de Jong M. A. J. G., Wagemakers A., Koelen M. (2019) Study protocol: evaluation of a community health promotion program in a socioeconomically deprived city district in the Netherlands using mixed methods and guided by action research. BMC Public Health, 19, 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett S., Schultz J., Watson-Thompson J., Fox M., Bremby R. (2010) Building multisectoral partnerships for population health and health equity. Preventing Chronic Disease, 7, 1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg B. (2006) Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar]

- Golden S. D., McLeroy K. R., Green L. W., Earp J. L., Lieberman L. D. (2015) Upending the social ecological model to guide health promotion efforts toward policy and environmental change. Health Education & Behavior, 42, 8S–14S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L. W. (2006) Public health asks of systems science: to advance our evidence-based practice, can you help us get more practice-based evidence? American Journal of Public Health, 96, 406–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting J., Kunst A. E., Kwan A., Stronks K. (2011) A ‘health broker’ role as a catalyst of change to promote health: an experiment in deprived Dutch neighbourhoods. Health Promotion International, 26, 65–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herens M., Wagemakers A., Vaandrager L., van Ophem J., Koelen M. (2013) Evaluation design for community-based physical activity programs for socially disadvantaged groups: communities on the move. JMIR Research Protocols, 2, e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogeling L., Vaandrager L., Koelen M. (2019) Evaluating the healthy futures nearby program: protocol for unraveling mechanisms in health-related behavior change and improving perceived health among socially vulnerable families in the Netherlands. JMIR Research Protocols, 8, e11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh J., Bush P. L., Salsberg J., Macaulay A. C., Greenhalgh T., Wong G.. et al. (2015) A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health, 15, 725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh J., Macaulay A. C., Pluye P., Salsberg J., Bush P. L., Henderson J.. et al. (2012) Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. The Milbank Quarterly, 90, 311–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karn S., Devkota M. D., Uddin S., Thow A. M. (2017) Policy content and stakeholder network analysis for infant and young child feeding in Nepal. BMC Public Health, 17, 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler M. C., Rigler J., Honeycutt S. (2010) How does community context influence coalitions in the formation stage? A multiple case study based on the community coalition action theory. BMC Public Health, 10, 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T., Kralik D. (eds) (2009) Participatory Action Research in Health Care. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Koelen M. A., van den Ban A. W. (eds) (2004) Health Education and Health Promotion. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen. [Google Scholar]

- Koelen M. A., Vaandrager L., Wagemakers A. (2008) What is needed for coordinated action for health? Family Practice, 25, i25–i31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelen M. A., Vaandrager L., Wagemakers A. (2012) The healthy alliances (HALL) framework: prerequisites for success. Family Practice, 29, i132–i138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenaars K. E. F., Smit E., Wagemakers A., Molleman G. R. M., Koelen M. A. (2015) Facilitators and barriers in the collaboration between the primary care and the sport sector in order to promote physical activity: a systematic literature review. Preventive Medicine, 81, 460–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezwijn J. (2011) Towards salutogenetic health promotion. PhD dissertation, Wageningen University, Wageningen.

- Long J. C., Cunningham F. C., Braithwaite J. (2013) Bridges, brokers and boundary spanners in collaborative networks: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin A., Wellman B. (2011) Social network analysis: an introduction. In Scott J., Carrington P. J. (eds) The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, pp. 11–25. 10.4135/9781446294413.n2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. (1998) Health promotion glossary. Health Promotion International, 13, 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Pluto D. M., Hirshorn B. A. (2003) Process mapping as a tool for home health network analysis. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 22, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provan K. G., Veazie M. A., Staten L. K., Teufel-Shone N. I. (2005) The use of network analysis to strengthen community partnerships. Public Administration Review, 65, 603–613. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed S., Roy S. K., Das S., Chowdhury S. N., Iqbal M., Akter S. M.. et al. (2017) Policy content and stakeholder network analysis for infant and young child feeding in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health, 17, 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed S. J., Miller R. L., Francisco V. T.; Adolescent Medical Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (2014) The influence of community context on how coalitions achieve HIV-preventive structural change. Health Education & Behavior, 41, 100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice M., Franceschini M. C. (2007) Lessons learned from the application of a participatory evaluation methodology to healthy municipalities, cities and communities initiatives in selected countries of the Americas. Promotion & Education, 14, 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos S. T., Fawcett S. B. (2000) A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annual Review of Public Health, 21, 369–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer E., Hauck J. (2010) Net-map: collecting social network data and facilitating network learning through participatory influence network mapping. Field Methods, 22, 231–249. [Google Scholar]

- Smit E., Leenaars K. E. F., Wagemakers A., Molleman G. R. M., Koelen M. A., van der Velden J. (2015) Evaluation of the role of care sport connectors in connecting primary care, sport, and physical activity, and residents’ participation in the Netherlands: study protocol for a longitudinal multiple case study design health behavior, health promotion and S. BMC Public Health, 15, 510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder M., Wagemakers A., Calabria B., Byrne B., O'Neill J., Bamblett R.. et al. (2020) We walked side by side through the whole thing’: a mixed-methods study of key elements of community-based participatory research partnerships between rural aboriginal communities and researchers. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 28, 338–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijhuis Y. (2018) Intersectoral Collaboration within the Voorstad on the Move Project. [Master's thesis]. Retrieved 25 January 2019, from: https://edepot.wur.nl/458260 (last accessed 11 November 2020).

- van den Berg M., Boerma W., de Jong J., van Ginneken E., Groenewegen P., Kroneman M. (2016) The Netherlands: health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 18, 1–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rinsum C. E., Gerards S. M. P. L., Rutten G. M., van de Goor I. A. M., Kremers S. P. J. (2017) Health brokers: how can they help deal with the wickedness of public health problems? BioMed Research International, 17, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagemakers A. (2010) Community Health Promotion. Facilitating and evaluating coordinated action to create supportive social environments. PhD dissertation, Wageningen University, Wageningen.

- Wagemakers A., Koelen M. A., Lezwijn J., Vaandrager L. (2010a) Coordinated action checklist: a tool for partnerships to facilitate and evaluate community health promotion. Global Health Promotion, 17, 17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagemakers A., Vaandrager L., Koelen M. A., Saan H., Leeuwis C. (2010b) Community health promotion: a framework to facilitate and evaluate supportive social environments for health. Evaluation and Program Planning, 33, 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. B., Duran B. (2006) Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7, 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N., Duran B. (2010) Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100, S40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijenberg E., Wagemakers A., Herens M., Hartog F., den Koelen M. A. (2019) The value of the participatory network mapping tool to facilitate and evaluate coordinated action in health promotion networks: two dutch case studies. Global Health Promotion, 26, 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2014). Health in all policies: Helsinki statement. Framework for country action. https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/frameworkforcountryaction/en/ (last accessed 8 November 2019).

- Yessis J., Riley B., Stockton L., Brodovsky S., von Sychowski S. (2013) Interorganizational relationships in the heart and stroke foundation’s spark together for healthy kidsTM. Health Education & Behavior, 40, 43S–50S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakocs R. C., Edwards E. M. (2006) What explains community coalition effectiveness? A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]