Abstract

Weight gain is a common harmful side effect of atypical antipsychotics used for schizophrenia treatment. Conversely, treatment with the novel phosphodiesterase-10A (PDE10A) inhibitor MK-8189 in clinical trials led to significant weight reduction, especially in patients with obesity. This study aimed to understand and describe the mechanism underlying this observation, which is essential to guide clinical decisions. We hypothesized that PDE10A inhibition causes beiging of white adipose tissue (WAT), leading to weight loss. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) methods were developed, validated, and applied in a diet-induced obesity mouse model treated with a PDE10A inhibitor THPP-6 or vehicle for measurement of fat content and vascularization of adipose tissue. Treated mice showed significantly lower fat fraction in white and brown adipose tissue, and increased perfusion and vascular density in WAT versus vehicle, confirming the hypothesis, and matching the effect of CL-316,243, a compound known to cause adipose tissue beiging. The in vivo findings were validated by qPCR revealing upregulation of Ucp1 and Pcg1-α genes, known markers of WAT beiging, and angiogenesis marker VegfA in the THPP-6 group. This work provides a detailed understanding of the mechanism of action of PDE10A inhibitor treatment on adipose tissue and body weight and will be valuable to guide both the use of MK-8189 in schizophrenia and the potential application of the target for weight loss indication.

Supplementary key words: MRI, beiging, PDE10A, MK-8189

Atypical antipsychotics are widely used for the treatment of schizophrenia, yet many are known to cause significant side effects limiting their tolerability and patient compliance (1). Weight gain is known to occur commonly, leading to an increased risk of associated diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and reduced quality of life (2). Recently, a novel approach to schizophrenia treatment has been reported based on phosphodiesterase-10A (PDE10A) inhibition, which may help limit the effect of therapy on patient weight. PDE10A is a member of the cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs) family of enzymes responsible for the degradation of cyclic AMP (cAMP) and cyclic GMP (cGMP) (3). It is encoded by a single gene and is highly expressed in the brain, especially in the striatum, and shows low expression in peripheral tissues (4). There is strong preclinical and emerging clinical evidence supporting the role of PDE10A in the treatment of schizophrenia. PDE10A-deficient mice demonstrated reduced exploratory behavior and a decreased response to the effects of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor–receptor antagonists phencyclidine and MK-801 (5). In clinical trials, a PDE10A inhibitor MK-8189 showed a significant improvement in positive symptoms in schizophrenia patients versus placebo (6), and a further trial is ongoing to evaluate a broader dose range (7). Interestingly, MK-8189 was shown to significantly reduce body weight in overweight and obese patients with schizophrenia, while a significant weight gain was observed for the standard-of-care risperidone (6). The weight loss noted in the MK-8189 group could contribute towards a reduction in obesity prevalent in schizophrenia patient population and its metabolic side effects (8), and improve the associated high rate of discontinuation as seen for atypical antipsychotics (1). A more detailed in vivo understanding of the mechanism of the PDE10A-mediated weight loss will be beneficial for further development of the therapeutic approach, addressing safety concerns related to weight loss, as well as exploring the potential for using PDE10A directly as a target for obesity treatment.

In vivo studies have been performed to understand the biological cause for PDE10A's influence on body weight. Nawrocki et al. (9) showed that pharmacological PDE10A inhibition increased whole-body energy expenditure in obese mice, leading to weight loss and reducing adiposity not attributable to alterations in food restriction. In addition, Hankir et al. (10) demonstrated an effect of PDE10A inhibition on increased brown adipose tissue (BAT) metabolism and showed ex vivo overexpression of thermogenic genes in the white adipose tissue of treated mice, providing a probable explanation for the observed weight modulation.

The characteristics and role of BAT in human metabolism have been the subject of research for several decades. Early results in the 1980s revealed its disproportionately high energy expenditure modulated in response to changes in demand (11), mediated predominantly by the expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) (12, 13). Regulation of this process was shown to be linked with obesity and weight change (14), reinforcing its therapeutic relevance (15). Importantly, plasticity was observed in adipose tissue. Responsible for most of fat storage in the body, White Adipose Tissue (WAT) which normally displays little metabolic activity and relevance has been shown to undergo a transition to a more BAT-like phenotype, in a process known as “beiging” or “browning” (16). The promise of beiging as a therapeutic strategy has been widely discussed (17). β3-adrenergic receptor agonist treatment such as CL-316,243 has been shown to lead to broad downstream metabolic changes, including beiging in humans and rodents (18, 19), while several other compounds have shown promising early results. However, this approach has not been clinically shown to lead to weight loss to date. PDE10A inhibition may provide a promising tool for clinical induction of beiging with a significant effect on body weight.

Positron emission tomography (PET) has been used to confirm the presence and activity of BAT in adult humans (20), yet challenges related to spatial resolution, specificity of 18F-FDG, quantification, and availability of more specific tracers limit the widespread application of this modality in BAT research. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may provide an alternative, offering versatile contrast sensitive to tissue composition, physiology, and metabolism at high spatial resolution. MRI methods have previously been applied to characterize adipose tissue in vivo and capture its response to tool compounds known to modulate adipose physiology (21, 22, 23), but never in the context of investigational drugs. In this study for the first time we developed and applied MRI methods to characterize in vivo the multiparametric changes in adipose tissue physiology in response to PDE10A inhibitor treatment, providing detailed insight into its mechanism of action. The methods used were validated in vivo using a β3-adrenergic receptor agonist CL-316,243 known to cause BAT activation and WAT beiging (24), showing results equivalent to these observed after PDE10A inhibition. This proposed approach is readily translatable to evaluate the effect size in humans in the ongoing clinical evaluation of PDE10A inhibitor in schizophrenia as well as the potential development of novel weight loss compounds based on this target.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments

Experiments were performed in diet-induced obese (DIO) C57Bl/6NTac mice (Taconic). Animals were individually housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle and fed a high-fat diet (D12492: 60% kcal from fat; Research Diets) for 16 weeks prior to the study start starting at 6 weeks old. All protocols for the use of these animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Merck & Co, Inc.

For measurement of response to PDE10A inhibitor treatment, animals were treated with vehicle (50% tween 80/0.25% methylcellulose, n = 11) or THPP-6 (n = 10, 30 mg/kg) PO daily for 14 days, while still fed a high-fat diet and MRI was performed on day 15. Given the known dramatic weight loss effect of THPP-6 (9), to ensure comparable weight across scanning at the time of imaging, randomization was not performed in the main experiment. Instead, heavier mice were chosen for the treated group, with the remaining ones in the vehicle group. This design did not affect the study findings, as validated in another experiment where weight randomization at day 0 was performed (see Supplementary Materials).

In the method validation study, DIO mice were treated with saline (n = 7) or CL-316,243 (n = 8, 1 mg/kg) injected IP daily for 7 days (24), while fed a high-fat diet. MRI was performed on day 8.

For validation of target engagement in the brain, a separate group of animals was treated with a single dose of vehicle (n = 10) or THPP-6 (n = 10, 30 mg/kg) and euthanized 2 h later for cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate (cGMP) measurement as described below.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% for induction and 1.5%–2.5% for maintenance) in 3:1 medical air:O2 mixture and placed in a custom cradle heated with circulating warm water. Temperature and respiration were monitored continuously using an MR compatible animal monitoring system (SA Instruments) and maintained at ∼50 breaths/min and 37.0°C respectively. A quadrature transmit-receive 40 mm volume coil was used and MRI was performed (Bruker BioSpec 70/30, 7T) for each animal first in the intrascapular region: Multislice Multiecho Gradient Echo (MGE) sequence, TR = 221.5 ms, FA = 10°, 14xTE = 3.5–10.78 ms, echo spacing 0.56 ms, FOV = 45 × 45 × 10.5 mm, 173 × 173 points, 15 slices, 9 averages, respiratory gating, duration of the scan was ∼7 min. Alternative approximate fat fraction measurement was performed in a subset of animals using a fat-suppressed fast spin echo scan (RARE, TR/TE = 2,500/20 ms, same FOV and matrix as above) followed by the same scan with no fat suppression. The inguinal region was then moved to the center of the coil and the above scan protocol was repeated with no respiratory gating. Afterward, dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) scan was performed in the same FOV:3D FLASH, TR/TE = 5.5/2.5 ms, FA = 25deg, 128 × 128 × 15 points, 100 repetitions (8 s/scan), with 0.2 mmol/kg Gadavist (Bayer, Germany) contrast bolus injected after 1 min through an IV catheter inside the magnet.

Image analysis

Quantification of Fat Fraction maps from the MGE scan was performed in VivoQuant (Invicro, MA) through the fitting of a multipeak magnitude model (25). The first six echo images were used to avoid noise fitting. All other analyses and quantification were performed using custom code in MATLAB 2021a. Regions of interest (ROI) for intrascapular BAT and inguinal WAT (iWAT) were segmented in each slice with the imfreehand function, separately in MGE and DCE scans.

A magnitude model was chosen for FF quantification for more robust convergence and given the severe limitations of complex-based FF estimation at high field and in small animal applications. However, specific to the magnitude-based model, FF values of x and 1-x (e.g., 0.3 and 0.7) could not be distinguished (26). Alternative measurements of fat fraction based on chemical shift-selective fat suppression were therefore performed in a subset of animals to inform further assumptions. While otherwise more prone to artifacts, fat fraction estimate maps can then be calculated as where FS and NS are the fat-suppressed and non-fat-suppressed images. Analysis of the maps revealed fat content of over 0.5 in BAT and subcutaneous WAT voxels (supplemental Fig. S3). Based on these observations, MGE FF maps were processed in MATLAB to assume the FF values in each voxel to be over 0.5 according to a formula , where is the unconstrained MGE magnitude model-based FF estimation. Median FF values from such processed maps were extracted for the BAT and iWAT ROIs for each mouse.

The processed FF maps were also utilized for blood vessel delineation. Areas of FF < 0.75 in iWAT ROIs with at least two connecting voxels in the slice were classified as blood vessels. The threshold was chosen by inspection to highlight the elongated structures known to be vessels from raw MGE images and DCE scans. The ROIs were shrunk radially by 1 voxel in each slice to exclude contributions from connective tissue. The fraction of positive voxels to all voxels in the shrunk ROI was denoted as vessel volume fraction (VVF) and quantified for each animal.

The approach for DCE quantification was designed to highlight subtle changes in perfusion of the very poorly vascularized iWAT. K-trans modeling was not performed due to low contrast enhancement. Instead, the amplitude of DCE signal enhancement was calculated for each voxel between 10 time-points approximately 2 min after contrast injection, when strong global enhancement was observed, and the six time-points acquired before injection. Voxels were then classified as positively enhancing if the amplitude of enhancement exceeded the standard deviation of the signal before injection. The fraction of enhancing to all iWAT voxels was quantified, denoted as DCE(+), and used as a metric of vascularity in the ROI. One animal was excluded from the DCE analysis due to motion after injection.

Gene expression analysis

Directly after imaging, the animals were sacrificed, and intrascapular, inguinal, and epididymal adipose tissue samples were collected for ex vivo analysis and frozen in −80°C.

Total RNA from ∼100 mg frozen adipose sample was extracted using a Tissuelyzer bead mill (Qiagen 85300) and Qiazol lysis reagent (Qiagen 79306). RNA was isolated using Qiagen RNeasy lipid tissue mini kit (Qiagen 74804). RNA was quantitated using a NanoDrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific ND-8000-GL). Two micrograms of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems 01152470). It was assumed that transcription efficiency approached 100%. Taqman gene expression assay was performed with the probes listed below. Fifteen nanograms/well cDNA was added to TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems 4444557) and an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio7 PCR system (Applied Biosystems 4485701) was used under the following conditions: 10 μl of reaction mix was run at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min and cycled from 95°C for 1 s to 60°C for 20 s for 40 rounds. Probes were from ThermoFisher and included Mm00442102_m1 (VegfB), Mm00437306_m1 (VegfA), Mm00443243_m1 (Tek), and Mm99999915_g1 (GAPDH).

Cycle threshold (CT) values were calculated for all samples (averaged over four wells/tissue sample) and genes, and ΔCT was the difference between CT for the gene of interest and the housekeeping gene (27). ΔΔCT denoted the difference between ΔCT for each animal minus the average ΔCT in the vehicle group. The degree of gene up-/downregulation versus vehicle is described by a factor 2−ΔΔCT, that is, positive ΔΔCT signifies downregulation.

Blood lipid analysis

Blood was drawn via cardiac puncture from all animals directly prior to sacrifice and serum frozen for a lipid panel analysis. Lipid analysis was performed based on a homogeneous enzymatic calorimetric assay on the Siemens Atellica CH930 chemistry analyzer using the Siemens Cholesterol (Cat #11097609) and Triglyceride (Cat #11097591) methods as well as Roche HDL (Cat #07528566) and LDL (07005717) methods adapted to the instrument. Concentrations of the above components in the serum were reported.

cGMP measurement

A 10-kW Muromachi brain fixation system, Model TMW-4012C (10 kW output) was used to euthanize the animals by exposure to head-focused microwave radiation 2 h after treatment. The animals were irradiated at 5.2 kW for 1.4 s. Following microwave fixation, the brain was harvested, and striatum dissected and frozen on dry ice. cGMP content in striatum was determined using the Direct cGMP ELISA Kit (Enzo Life Sciences) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

All errors are quoted as the standard error of the mean unless stated otherwise. Statistical analyses were performed in MS Excel 2021 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Unpaired two-tailed t test compared metrics between different cohorts. Pearson rank test was performed to assess the significance of the correlation between parameters. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Significance of gene upregulation was assessed by comparison of ΔΔCT values for the two cohorts for a given gene using the unpaired two-tailed t test.

Results

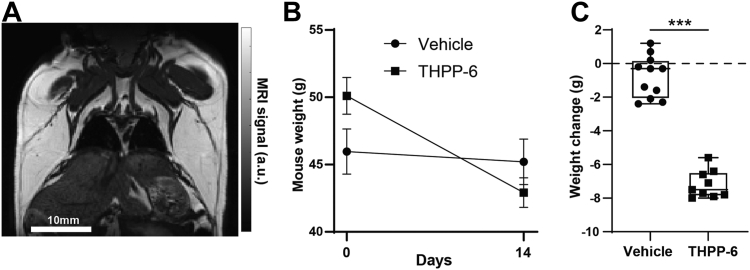

Consistent with previous preclinical and clinical observations, treatment with PDE10A inhibitor THPP-6 over 14 days in obese mice led to a decrease in body weight not observed in vehicle group (Fig. 1, 0.7 ± 0.3 g vs. −5.7 ± 0.6 g weight change day 14 - day 0 treated vs. vehicle P < 10−7). The modest weight loss observed in the vehicle group may be attributed to daily oral dosing. A trending positive relationship was observed between initial weight and the weight loss amount (r = .60, P = 0.09) in the treated animals, similar to the clinical case where obese patients showed the greatest weight loss on PDE10A inhibitor treatment (6). In a separate experiment, where mice were randomized by weight before treatment, a similar weight loss effect limited to THPP-6 group was observed (47.2 ± 1.0 g vs. 47.9 ± 1.0 g vehicle, 47.4 ± 0.9 g vs. 41.7 ± 1.4 g THPP-6, P < 10−5, see Supplementary Materials). Similar weight change trends were observed when animals were treated with CL-316,243, a compound with a known effect on BAT activation and WAT beiging. Strong weight loss was noted in the CL-316,243 treated group with a modest, significantly lower decrease in weight observed in the vehicle group attributable to repeated injections (−2.4 ± 0.5 g vs. −1.0 ± 0.3 g weight loss treated vs. vehicle, P = 0.035 between groups, see Supplementary Materials).

Fig. 1.

PDE10A inhibitor treatment leads to weight loss in obese mouse model. A non-fat-suppressed T2-weighted MR scan shows a representative Diet-Induced Obesity mouse (A) with significant subcutaneous fat deposits visible in white. During 14 days of treatment, dramatic weight loss was observed in THPP-6 cohort (B), for which heavier animals were used to minimize weight difference at imaging (Day 14). The average weight change for each animal during treatment is shown in (C). Box between 25th and 75th percentile, line at median. ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

In the target engagement experiment, cGMP concentration in the striatum region of the brain was significantly increased in THPP-6 treated versus vehicle mice (3.2 ± 0.9 vs. 1.38 ± 0.15, P = 0.044). This is in line with the effect of PDE10A on the degradation of cGMP, with PDE10A inhibition leading to increased cGMP concentration as expected.

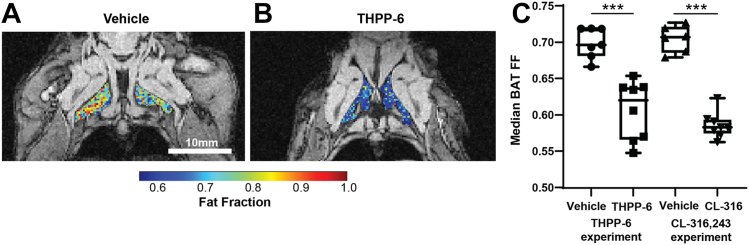

Measurements of fat fraction in intrascapular BAT depots revealed significantly lower fat content in after THPP-6 treatment compared with the vehicle (Fig. 2, FF = 0.700 ± 0.008 vs. 0.619 ± 0.012 vehicle vs. THPP-6, P = 0.0001) consistent with the BAT activating effect of the treatment. CL-316,243 treatment, known to cause BAT activation, led to an equivalent effect on BAT FF (FF = 0.705 ± 0.007 vs. 0.587 ± 0.006 vehicle vs. CL-316,243, P < 10−7).

Fig. 2.

PDE10A inhibitor treatment causes BAT fat content decrease consistent with BAT activation. Representative images of Fat Fraction (FF) in intrascapular BAT in vehicle (A) and THPP-6 (B) treated animals, overlaid onto single echo raw images for anatomical reference. Median FF in BAT region of interest was significantly lower in THPP-6 versus vehicle group, with the same effect observed for CL-316,243 (C). Box between 25th and 75th percentile, line at median. ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

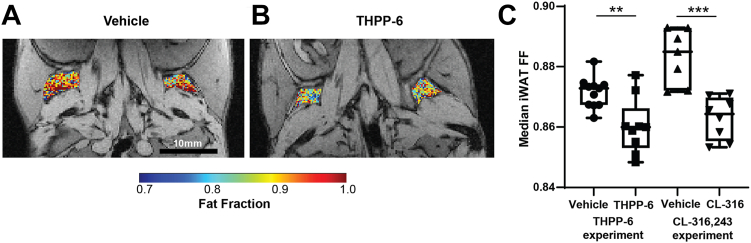

FF quantification in inguinal WAT depots showed high values and a more homogeneous distribution (Fig. 3) compared to intrascapular BAT. Importantly, a significant treatment-induced FF reduction was also observed in these WAT deposits, a hallmark of the beiging transition (FF = 0.8715 ± 0.0015 vs. 0.860 ± 0.003 vehicle vs. THPP-6, P = 0.003). No within-group correlation was observed between mouse weight and iWAT FF (Pearson r = 0.21, P = 0.58 in THPP-6 and r = 0.37, P = 0.26 in Vehicle cohort) suggesting that the difference in FF is not driven by the weight change. Significantly lower FF in treated versus vehicle groups was observed also in the experiment with tool compound CL-316,243 (FF = 0.883 ± 0.003 vs. 0.863 ± 0.002 vehicle vs. CL-316,243, P = 0.0003) validating the measurement protocol.

Fig. 3.

Inguinal WAT shows fat fraction decrease after treatment adipose tissue beiging. Representative images of Fat Fraction (FF) in inguinal WAT (iWAT) in vehicle (A) and THPP-6 (B) treated animals, overlaid onto single echo raw images for anatomical reference. Median FF in iWAT was significantly lower in THPP-6 versus vehicle group (C), as well as in CL-316,243 and its corresponding vehicle group. Box between 25th and 75th percentile, line at median. ∗∗P < 0.01.

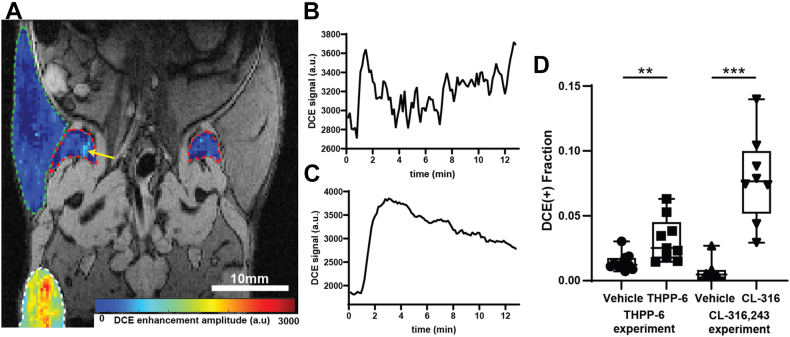

Vascularization of the iWAT depots was also evaluated as a hallmark of white fat beiging. DCE MRI showed relatively low overall contrast enhancement in the regions as expected, yet detailed analysis revealed small areas of positive enhancement (Fig. 4). Quantification of the enhancing ROI volume fraction, indicative of the presence of functional vasculature, revealed significantly elevated values in THPP-6 group versus vehicle (0.014 ± 0.002 vs. 0.032 ± 0.006, vehicle vs. THPP-6, P = 0.008), supporting treatment-induced angiogenesis of the depots. Qualitatively the same effect was observed when treated with CL-316,243 (0.007 ± 0.004 vs. 0.079 ± 0.012 vehicle vs. CL-316,243, P = 0.0001), validating the link between observed vascular changes and adipose tissue physiology.

Fig. 4.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI shows increased iWAT perfusion after treatment. DCE enhancement amplitude in a representative animal from the THPP-6 cohort is shown in (A) for iWAT (red outline), flank subcutaneous WAT (green outline) and leg muscle (white outline) overlaid on single echo anatomical reference. Yellow arrow points at the area of positive enhancement in iWAT. DCE signal profile for this area is shown in (B) while a corresponding profile from a well-perfused leg muscle is shown in (C). Quantification of iWAT positively enhancing volume fraction (D) shows significantly elevated values in THPP-6 versus vehicle, as well as in CL-316,243 versus its vehicle groups. Box between 25th and 75th percentile, line at median. ∗∗P < 0.01.

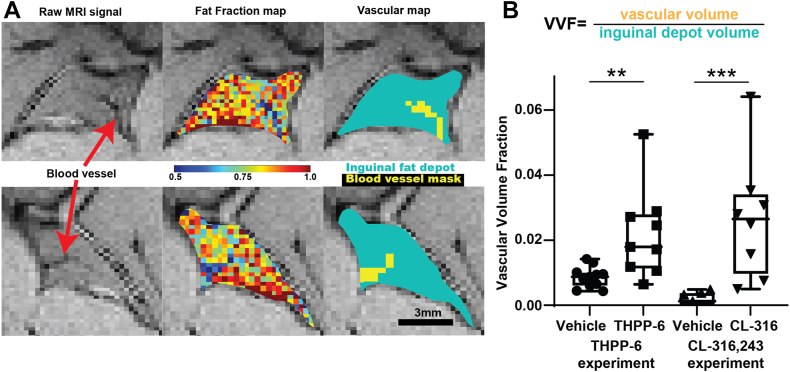

Independent measurement of iWAT vascularization was provided through the segmentation of blood vessels apparent in FF maps through their lower fat content. As shown in Fig. 5, voxels containing blood vessels were identified in the raw MGE images and robustly segmented in the FF maps. The volume fraction of the ROI occupied by these positive voxels (Vascular Volume Fraction, VVF) was compared between treatment groups, revealing significantly increased macroscopic vessel coverage in THPP-6 cohort (VVF = 0.0086 ± 0.0010 vs. 0.022 ± 0.005, vehicle vs. THPP-6, P = 0.006), as well as a matching difference due to CL-316,243 treatment (0.008 ± 0.002 vs. 0.044 ± 0.006 vehicle vs. CL-316,243, P = 0.0001). These results support the DCE findings.

Fig. 5.

Blood vessel segmentation confirms increased iWAT vascularization due to beiging. Two representative iWAT depots from THPP-6 treated animals (A, top and bottom line) show blood vessel infiltration into the depots (red arrows) in raw single echo images, fat fraction maps, and automatically segmented vascular maps. Quantification of the fraction of voxels classified as blood vessels (Vascular Volume Fraction, VVF) shows significantly higher values in THPP-6 versus vehicle cohort (B), with performance of the method validated by a similar difference in CL-316,243 versus its vehicle group. Box between 25th and 75th percentile, line at median. ∗∗P < 0.01.

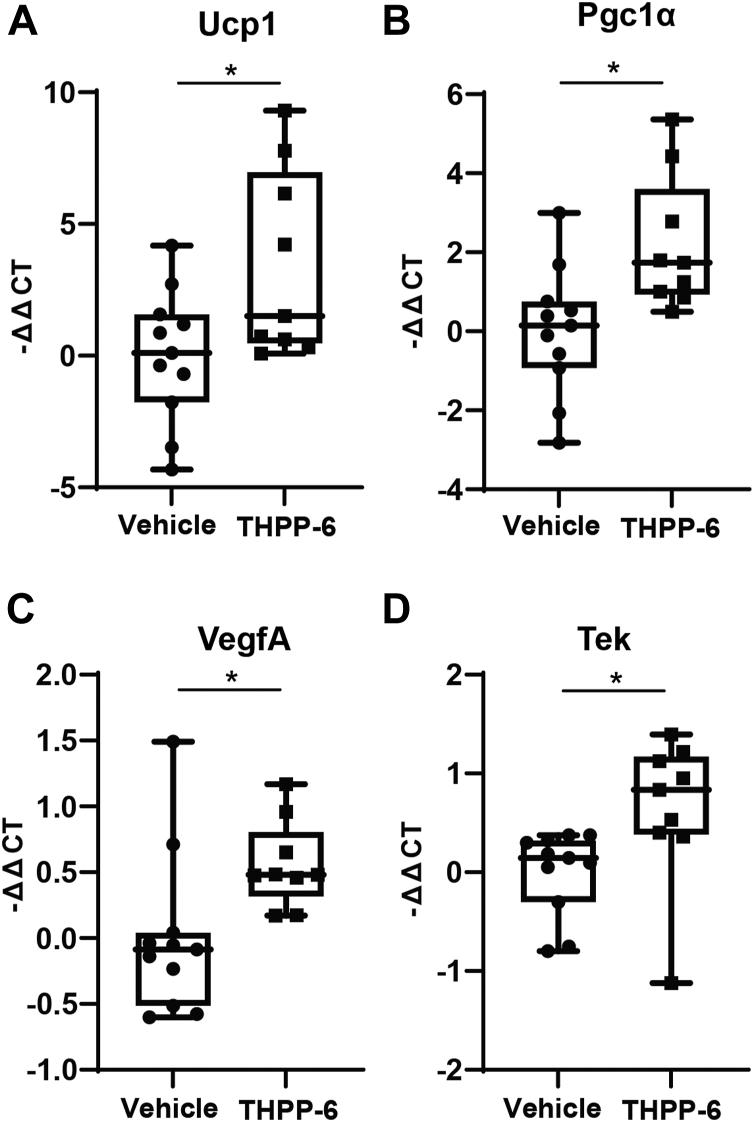

Ex vivo validation of the imaging results was performed through gene expression analysis in adipose tissue samples. A panel of genes known to be involved in BAT activity and beiging transition was tested. Significant upregulation of several key genes was observed in the iWAT in the THPP-6 treated versus vehicle cohorts (Fig. 6), including Ucp1 and Pgc1α (P = 0.032 and P = 0.015 respectively). These results validate the imaging observation of iWAT beiging. In addition, to specifically evaluate the extent of angiogenesis signaling in the adipose depots, VegfA, VegfB, and Tek (Tie2) expression was compared between the cohorts. In line with the increased vascularization and perfusion, significant upregulation of VegfA and Tek was observed in iWAT of THPP-6 treated animals (P = 0.018 and P = 0.016, respectively). Interestingly, significant upregulation of VegfA was also observed in THPP-6 mice in epididymal WAT tissue (P = 0.02), with VegfB and Tek showing no difference in expression. No difference in any of the above markers was noted for BAT. Blood lipid analysis did not show significant differences between the THPP-6 and vehicle cohort in any of the markers – Cholesterol, Triglycerides, HDL and LDL (P > 0.12, supplemental Fig. S4).

Fig. 6.

Gene expression analysis confirms beiging of iWAT after THPP-6 treatment. Quantification of delta-delta-Cycle Threshold (ΔΔCT) with respect to a housekeeping gene and vehicle group revealed significant upregulation in THPP-6 cohort of Ucp1 (A) and Pgc1α (B), genes characteristic for their expression in BAT, as well as of VegfA (C) and Tek (D), linked with angiogenesis. Box between 25th and 75th percentile, line at median. ∗P < 0.05.

Discussion

The role of brown and white adipose tissue metabolism in weight modulation has been widely studied with an array of approaches, including in vivo imaging. However, the therapeutic impact of this research has been limited due to a lack of robust targets and clinical compounds in this field. Recently, PDE10A inhibitor treatment has highlighted the clinical relevance of this relationship, demonstrating a strong weight loss effect in overweight and obese schizophrenia patients apparently linked with the modulation of adipose tissue metabolism (9, 10). In this study a novel MRI framework is used to reveal and characterize the underlying mechanism of action of the PDE10A inhibitor treatment, capturing the transition from white to brown adipose tissue and activation of the brown adipose tissue depots in an obese mouse model.

Significant decreases in fat content of both brown and white adipose tissue depots were observed in treated animals, consistent with activation of BAT and beiging of WAT. In WAT, these changes were complemented by increased vascular infiltration, confirmed independently with two MR techniques, the second hallmark of WAT beiging. While beiging was previously measured with MRI after aggressive treatment with a known potent β3-adrenoceptor agonist (22), this study represents the first time a beiging transition was observed after investigational therapy. The optimized method involving a novel DCE data analysis approach enabled for subtle vascular differences to be captured between treatment cohorts. Vessel segmentation implemented on FF images provided independent in vivo validation of the DCE observations.

The novel multi-parametric method for WAT beiging characterization utilized in this study was additionally validated in vivo using the β3-adrenoceptor agonist CL-316,243 as a positive control. The measurements showed a highly significant decrease in adipose tissue fat content and increase in vascularization, matching the response to PDE10A inhibitor treatment. These results validate and confirm high sensitivity of the imaging method proposed. To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that both the changes in fat content and vascularization in WAT related to beiging can be captured in mice using MRI. Importantly, given the similarity in response between the β3-adrenoceptor agonist, known to induce beiging, and the THPP-6, these findings further support our conclusion that changes observed after PDE10A inhibitor treatment were due to WAT beiging and BAT activation.

Comprehensive ex vivo validation through gene expression analysis confirmed the imaging findings, showing upregulation of both BAT-specific genes in the iWAT, and of angiogenesis signaling consistent with increased vascularization in THPP-6 treated mice. Angiogenesis is known to be closely linked with the function and metabolism (28) of both white and brown adipose tissue. In iWAT, the focus of this study, increased VegfA expression was previously observed after cold exposure and β3-adrenoceptor agonist treatment (29), both known to induce WAT beiging, reinforcing our understanding of PDE10 inhibition effect.

Previous work (9) confirmed that the effect of PDE10A inhibition on body weight loss is not attributable to reduced food intake alone. In a pair-feeding experiment, DIO mice treated with a dose of THPP-6 matching this study showed significantly higher weight loss to vehicle-treated controls at the same caloric intake. This difference was further shown to be due to increased energy expenditure, as measured in a calorimetry experiment.

The in vivo effects of PDE10A inhibition in this study were evaluated by a single timepoint comparison between treatment groups. Further insight could be derived from longitudinal observations pre- and post-treatment. This was not possible for the DIO mouse model. In pilot experiments, handling for the pre-treatment imaging had a drastic impact on the food intake and weight of the animals for multiple days, introducing a confounding factor that compromised the findings. In the future, alternative obese models less sensitive to such perturbations may be used to observe longitudinal effects of PDE10A inhibition with MRI and validate the findings. Additionally, pair-feeding may be used to strictly isolate the effect of treatment-induced metabolic changes on WAT beiging.

The MRI evaluation of WAT beiging in this work was focused on inguinal WAT, a distinct subcutaneous white adipose tissue depot known to be susceptible to beiging and physiological changes due to presence of beige adipocytes (16). In humans, BAT depots have been observed in the inguinal area (30). The gene expression analysis after PDE10A inhibition in this study revealed upregulated angiogenesis signaling not limited to iWAT, but observed also in epididymal adipose tissue, known to be less susceptible to beiging than subcutaneous WAT (16). These findings suggest a widespread systemic effect of PDE10A inhibition on adipose tissue, consistent with the dramatic weight loss observed in the model after treatment, exceeding 10% over 14 days. More work may be performed in the future to provide further insight into the changes observed outside BAT and inguinal WAT.

Further research is also needed to elucidate the exact mechanism of PDE10A-mediated adipose physiology changes. Classically, cAMP, increased robustly by PDE10A inhibition, is known to regulate BAT and WAT metabolism and induce thermogenesis through the Protein kinase A (PKA) activation (31), and downstream targets which ultimately induce UCP1 expression. While a statistically significant UCP1 upregulation was observed in WAT in this study, the modest magnitude of its change compared to previous reports using CL-316,243 (24) suggests potential UCP1-indepentent mechanisms should also be considered (12). Creatine-driven substrate cycling (32), as well as calcium ion cycling (33) have been shown to induce thermogenesis bypassing UCP1, however their relationship with PDE10A or cAMP/cGMP is not known. These measurements should be included in future investigations.

Given the advanced stage of clinical development of PDE10A inhibitor therapy, the findings presented above are of direct clinical relevance, providing a mechanistic explanation for the weight loss observed in patients with schizophrenia in the Phase 2 trial (6). Non-invasive MRI measurements of adipose tissue fat fraction have been successfully performed in healthy volunteers and can be readily included in future trials for direct clinical validation, as relevant pulse sequences and analysis algorithms are available routinely on clinical MR systems.

Data availability

All raw and processed MRI data, quantification, and analysis code are available upon request.

Supplemental data

This article contains supplemental data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: All authors are employed by Merck & Co Inc.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

M. R. T., H. D. H., C. M. H., T. P. M., and C. O. M. methodology; M. R. T. software; M. R. T., J. M., H. D. H., and C. M. H. investigation; M. R. T., C. M. H., and T. P. M. formal analysis; M. R. T. and S. M. S. writing–original draft; M. R. T. visualization; J. M. and H. D. H. project administration; J. M., H. D. H., C. M. H., T. P. M., C. O. M., and S. M. S. writing–review & editing; C. M. H., T. P. M., C. O. M., and S. M. S. resources; T. P. M. and C. O. M. supervision; C. O. M. and S. M. S. conceptualization.

Supplemental data

References

- 1.Tsutsumi C., Uchida H., Suzuki T., Watanabe K., Takeuchi H., Nakajima S., et al. The evolution of antipsychotic switch and polypharmacy in natural practice--a longitudinal perspective. Schizophr. Res. 2011;13:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newcomer J. Metabolic risk during antipsychotic treatment. Clin. Ther. 2004;26:1936–1946. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conti M., Beavo J. Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bender A., Beavo J. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siuciak J., Chapin D.S., Harms J.F., Lebel L.A., McCarthy S.A., Chambers L., et al. Inhibition of the striatum-enriched phosphodiesterase PDE10A: a novel approach to the treatment of psychosis. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51:386–936. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukai Y., Lupinacci R., Marder S., Mackle M., Snow-Adami L., Voss T., et al. P534. Initial assessment of the clinical profile of the PDE10A inhibitor MK-8189 in patients with an acute episode of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2022;91:S305. (in English) [Google Scholar]

- 7. NCT04624243 . Efficacy and Safety of MK-8189 in Participants With an Acute Episode of Schizophrenia (MK-8189-008) 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casey D., Haupt D.W., Newcomer J.W., Henderson D.C., Sernyak M.J., Davidson M., et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: implications for increased mortality in patients with schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2004;65 Suppl 7:4–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nawrocki A., Rodriguez C.G., Toolan D.M., Price O., Henry M., Forrest G., et al. Genetic deletion and pharmacological inhibition of phosphodiesterase 10A protects mice from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2014;63:300–311. doi: 10.2337/db13-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hankir M., Kranz M., Gnad T., Weiner J., Wagner S., Deuther-Conrad W., et al. A novel thermoregulatory role for PDE10A in mouse and human adipocytes. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8:796–812. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201506085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothwell N., Stock M. Luxuskonsumption, diet-induced thermogenesis and brown fat: the case in favour. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 1983;64:19–23. doi: 10.1042/cs0640019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeda K., Yamada T. UCP1 dependent and independent thermogenesis in brown and beige adipocytes. Front. Endocrinol. 2020;11:498. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannon B., Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alcalá M., Calderon-Dominguez M., Serra D., Herrero L., Viana M. Mechanisms of impaired brown adipose tissue recruitment in obesity. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:94. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNeill B., Suchacki K., Stimson R. Human brown adipose tissue as a therapeutic target: warming up or cooling down? Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021;184:R243–R259. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J., Boström P., Sparks L.M., Ye L., Choi J.H., Giang A.H., et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012;150:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herz C., Kiefer F. Adipose tissue browning in mice and humans. J. Endocrinol. 2019;241:R97–R109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Mara A., Johnson J.W., Linderman J.D., Brychta R.J., McGehee S., Fletcher L.A., et al. Chronic mirabegron treatment increases human brown fat, HDL cholesterol, and insulin sensitivity. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:2209–2219. doi: 10.1172/JCI131126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Y., Berry D.C., Graff J.M. Distinct cellular and molecular mechanisms for β3 adrenergic receptor-induced beige adipocyte formation. Elife. 2017;6:e30329. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cypess A.M., Lehman S., Williams G., Tal I., Rodman D., Goldfine A.B., et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu M., Junker D., Branca R., Karampinos D. Magnetic resonance imaging techniques for Brown adipose tissue detection. Front. Endocrinol. 2020;11:421. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yaligar J., Verma S.K., Gopalan V., Anantharaj R., Thu Le G.T., Kaur K., et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI of brown and beige adipose tissues. Magn. Reson. Med. 2020;84:384–395. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panagia M., Chen Y.C.I., Chen H.H., Ernande L., Chen C., Chao W., et al. Functional and anatomical characterization of brown adipose tissue in heart failure with blood oxygen level dependent magnetic resonance. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:978–984. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keinan O., Valentine J.M., Xiao H., Mahata S.K., Reilly S.M., Abu-Odeh M., et al. Glycogen metabolism links glucose homeostasis to thermogenesis in adipocytes. Nature. 2021;599:296–301. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yokoo T., Bydder M., Hamilton G., Middleton M.S., Gamst A.C., Wolfson T., et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: diagnostic and fat-grading accuracy of low-flip-angle multiecho gradient-recalled-echo MR imaging at 1.5 T. Radiology. 2009;251:67–76. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511080666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu H., Shimakawa A., Hines C.D.G., McKenzie C.A., Hamilton G., Sirlin C.B., et al. Combination of complex-based and magnitude-based multiecho water-fat separation for accurate quantification of fat-fraction. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011;66:199–206. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak K., Schmittgen T. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herold J., Kalucka J. Angiogenesis in adipose tissue: the interplay between adipose and endothelial cells. Front. Physiol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.624903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo X., Jia R., Luo X.Q., Wang G., Zhang Q.L., Qiao H., et al. Cold exposure differentially stimulates angiogenesis in BAT and WAT of mice: implication in adrenergic activation. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017;42:974–986. doi: 10.1159/000478680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sacks H., Symonds M. Anatomical locations of human brown adipose tissue: functional relevance and implications in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:1783–1790. doi: 10.2337/db12-1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.London E., Bloyd M., Stratakis C.A. PKA functions in metabolism and resistance to obesity: lessons from mouse and human studies. J. Endocrinol. 2020;246:R51–R64. doi: 10.1530/JOE-20-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kazak L., Chouchani E.T., Jedrychowski M.P., Erickson B.K., Shinoda K., Cohen P., et al. A creatine-driven substrate cycle enhances energy expenditure and thermogenesis in beige fat. Cell. 2015;163:643–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikeda K., Kang Q., Yoneshiro T., Camporez J.P., Maki H., Homma M., et al. UCP1-independent signaling involving SERCA2b-mediated calcium cycling regulates beige fat thermogenesis and systemic glucose homeostasis. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1454–1465. doi: 10.1038/nm.4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw and processed MRI data, quantification, and analysis code are available upon request.