Abstract

Background:

Evidence-based models are needed for delivering exercise-related services for knee osteoarthritis (OA) efficiently and according to patient needs.

Objective:

To examine a STepped Exercise Program for patients with Knee OsteoArthritis (STEP-KOA).

Design:

Randomized controlled trial.

Setting:

Two Department of Veterans Affairs sites.

Participants:

345 patients (mean age 60 years, 15% female, 67% non-white) with symptomatic knee OA

Interventions:

Participants were randomized to STEP-KOA and Arthritis Education (AE) Control groups with a 2:1 ratio, respectively. STEP-KOA began with three months of internet-based exercise program (Step 1). Participants not meeting response criteria for improvement in pain and function after Step 1 progressed to Step 2, involving 3 months of bi-weekly physical activity coaching calls. Participants not meeting response criteria after Step 2 progressed to in-person physical therapy visits (Step 3). The AE group received educational materials via mail every two weeks.

Measurements:

The primary outcome was the Western Ontario and McMasters Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC). WOMAC scores for STEP-KOA and AE groups at 9 months were compared using linear mixed models.

Results:

In the STEP-KOA group, 65% (150/230) of participants progressed to Step 2 and 35% (81/230) progressed to Step 3. The estimated baseline WOMAC score for the full sample was 47.5 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 45.7, 49.2). At 9-month follow-up, the estimated mean WOMAC score was 6.8 points (95% CI −10.5, −3.2) lower in the STEP-KOA group compared to the AE group, indicating greater improvement.

Limitations:

Participants were mostly male Veterans, and follow-up time was limited.

Conclusion:

Veterans in STEP-KOA reported modest improvements in knee OA symptoms compared to the control group. STEP-KOA may be an efficient strategy for delivering exercise therapies for knee OA.

Trial Registration:

Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02653768 (STepped Exercise Program for Knee OsteoArthritis (STEP-KOA)), Registered January 12, 2016

INTRODUCTION

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of chronic pain and disability (1, 2). The prevalence of knee OA is projected to continue rising substantially, highlighting the importance of delivering guideline-based and efficient care within health systems (3). Knee OA treatment guidelines consistently recommend exercise-based therapies, including physical therapy (PT), as core components (4–6), based on evidence for their effectiveness (7, 8). However, the vast majority of patients with knee OA are physically inactive,(9) and PT is substantially under-utilized (10–12). Reasons for low use of PT include limited access (related to health insurance coverage or lack of physical therapists in some settings) (13) and lack of evidence regarding which patients may benefit most from PT. Some patients with knee OA may experience improvements in symptoms through lower cost exercise-based interventions, while others may require additional support from a physical therapist to address specific impairments that limit activity. However, there are currently no evidence-based models for delivering different types of exercise-related services for knee OA efficiently and according to patient needs.

Stepped care models have been applied in pain management and other health conditions to customize treatments based on patients’ responses (14–18). These interventions, which begin with a low intensity treatment and “step up” to more intensive treatments if patients do not experience clinically relevant improvement, are attractive from both patient and resource allocation perspectives (19, 20). For patients, stepped care allows tailoring based on patient-centered outcomes. For health care systems, stepped care reserves costlier or limited resources (e.g. physical therapist time) for patients who do not respond adequately to other approaches. This study examined a novel STepped Exercise Program for patients with Knee OsteoArthritis (STEP-KOA), beginning with an internet-based exercise program and stepping up sequentially to telephone-based physical activity coaching and in-person PT if patients did not achieve meaningful improvements in OA-related symptoms in prior steps.

METHODS

Detailed study methods have been published (21).

Design Overview.

Participants were randomized to STEP-KOA and Arthritis Education (AE) arms (Figure 1). Three- and six-month assessments determined whether participants in STEP-KOA progressed to more intensive steps, based on established response criteria (see below) (22). The primary outcome time point was at nine months. Following 9-month assessments, AE arm participants were offered Step 1 and 2 interventions.. All participants continued other usual medical care for OA during the study. Enrollment began on 9/16/2016, and 9-month follow-up was completed on 2/6/2019. This trial (NCT02653768) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Durham Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System.

Figure 1:

CONSORT Diagram

Note: Some participants could not be contacted at one time point but did not withdraw and were successfully contacted at a later time point. Therefore, the follow-up numbers at 6 and 9 months include some people who were not included at the prior time point.

Setting and Participants.

This study was conducted at two VA sites: Durham, NC and Greenville, NC. Participants were n=345 Veterans who had: 1) Diagnosis of Knee OA, identified from VA electronic medical records plus self-report of a clinician diagnosis of OA, and 2) Self-reported Joint Pain ≥3 (0–10 scale) in a knee with OA over the past two weeks. Exclusion criteria, described previously, included co-occurring rheumatic conditions, recent completion of PT for knee OA, and health conditions that would make unsupervised exercise unsafe.(21) The primary recruitment method involved identification of patients with knee OA in VA electronic medical records, followed by an introductory letter. Participants had an International Classification of Disease-9 or −10 code for general OA or knee OA; for those with general OA code, a trained research coordinator reviewed the electronic health record (EHR) to verify a clinician had made a diagnosis of knee OA. Veterans could also self-refer, and clinicians could refer patients; this was followed by EHR review to verify a knee OA diagnosis. All potential participants completed a screening telephone call, followed by an in-person visit to complete consent and baseline assessments.

Randomization and Interventions

Participants were randomized to STEP-KOA or AE in a 2:1 ratio, respectively, using a stratified, block randomization with block sizes of 3. Strata were gender and study site. The randomization sequence was generated by a study statistician, stored in the study database and accessible only to un-blinded team members. Participants were informed of their randomization assignment following completion of baseline assessments.

STEP-KOA Intervention

STEP-KOA Overview.

Progression to advanced steps was based on Outcome Measures in Rheumatology group and the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OMERACT-OARSI) response criteria.(22) Participants could meet criteria for a clinically relevant response in two ways: 1) ≥50% improvement in pain or function and absolute change ≥20 or 2) Improvement in at least two of the following: pain ≥20% and absolute change ≥10; function ≥20% and absolute change ≥10; Patient Global Impression of Improvement (since beginning of study) = better or much better (vs. worse, much worse, same).

STEP-KOA began with access to an internet-based exercise program for knee OA (Step 1). After 3 months, participants not meeting OMERACT-OARSI response criteria progressed to Step 2: bi-weekly telephone coaching to address barriers to physical activity. After 3 months of Step 2, participants still not meeting response criteria progressed to Step 3: in-person PT visits. Some participants initially met response criteria at 3 months but regressed by 6 months and no longer met response criteria when compared to baseline; these participants were advanced to Step 2 at 6-months. If participants missed their 3-month or 6-month assessment, they remained in their assigned Step at that time point.

Step 1: Internet-based Exercise Training (IBET).

The IBET program provided personalized exercise recommendations including progression of activities, with seven exercise levels (23). Initial exercise level assignment was based on self-reported pain, function and activity. Each level included stretching and strengthening exercises, along with aerobic exercise recommendations. Static pictures and videos of assigned stretching and strengthening exercises were provided. Participants were instructed to complete stretching and strengthening exercises at least three times per week. They could request at any time to move to a harder or easier exercise level but could only move to a harder level if their score on the modified short-form of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) was better than or equal to their previous score. Participants were given ankle weights and elastic resistance bands, and those without internet access were given an iPad and data plan during their intervention period.

Step 2: Six Bi-Weekly Telephone-Based Physical Activity Coaching.

The goals of Step 2 calls were to address OA-related and other barriers to exercise, provide social support for physical activity, reinforce the benefits of physical activity, and use motivational interviewing strategies to address any ambivalence regarding physical activity (24). During each call, the coach led patients in goal-setting for their weekly physical activity, using “SMART” (Specific, Measurable, Action-oriented, and Time-Bound) principles (25); patients were encouraged to perform strengthening exercises 2–3 times per week and to aim for a long-term goal of 150 minutes of physical activity per week (based on guidelines), but goals were tailored to patients’ functional abilities. Coaches (n=3 with Masters Degrees in health education related fields) received training from co-investigators with experience in exercise science, physical activity coaching, telephone-based interventions and motivational interviewing. A subset of intervention calls was audio-recorded, and co-investigators used fidelity checklists to provide feedback to the coaches.

Step 3: PT Visits.

PT visits were based on usual care for knee OA and included a personalized exercise program, instruction in activity pacing and joint protection, and evaluation of mobility, stability, function, knee alignment, limb length inequalities, muscle weakness, inflexibility, and need for mobility aids, knee braces, and shoe orthotics. VA physical therapists (n=7, 3–9 years of experience) delivered the intervention; the principal investigator provided therapists with 1 initial training session, followed by periodic fidelity checks. Participants were asked to attend 3–7 PT visits, based on progression toward goals. The first PT session lasted 1 hour, and remaining visits were 30 minutes each. Participants were paid for travel to each PT visit ($10 plus an additional amount that varied by distance).

Arthritis Education Control Condition

Participants in the AE control group received educational materials via mail every two weeks for 9 months. The AE intervention included a comprehensive set of topics related to OA and its management, described previously and based on established treatment guidelines (21, 26, 27).

Outcomes and Follow-Up

Study assessments were conducted in person at baseline and 9-months and via telephone at 3- and 6-months. Assessments were conducted by a trained, blinded research assistant. Participants were paid $40 for in-person and $20 for telephone-based assessments.

Primary Outcome: WOMAC.

The WOMAC is a measure of lower extremity pain (5 items), stiffness (2 items), and function (17 items), with items rated on a Likert scale of 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (extreme symptoms). The reliability and validity of the WOMAC total score and subscales have been confirmed, and it has been used in many trials of behavioral interventions for OA, including telephone-based administration (28, 29).

Secondary Outcome: Objective Physical Function.

Physical function assessments included a 30 second stair stand test (30), a 40 meter fast-paced walk (31), a timed get up and go test, stair climbing test (12 steps), and a 6-minute walk test, following previously established procedures for each (32). Following each test, participants were asked to indicate the maximum pain they experienced during the test, on a scale of 0–10.

Physical Activity Measures

Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE).

The PASE is a self-report, 12-item scale that measures occupational, household, and leisure activity during a one-week period; higher scores indicate greater weekly activity.(33)

Participant Characteristics.

We report information on participants’ age, race / ethnicity, gender, household financial status, education level, work status, marital status, body mass index, rating of comfort with internet use (Likert scale of 1=not at all comfortable to 5=very comfortable), comorbid illnesses (Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire) (34), duration of arthritis symptoms, and self-rated general health (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of STEP-KOA Participants, Overall and By Arm

| Characteristic | Total Sample (N=345) Mean ± SD or N (%) |

STEP-KOA (N=230) Mean ± SD or N (%) |

AE Control (N=115) Mean ± SD or N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Age | 60.0 (10.3) | 59.9 (9.9) | 60.2 (11.1) |

| Female | 53 (15.4) | 36 (15.7) | 17 (14.8) |

| Non-White Race* | 229 (67.3) | 155 (68.3) | 74 (65.5) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 8 (2.3) | 4 (1.7) | 4 (3.5) |

| Some education above high school | 275 (79.7) | 184 (80.0) | 91 (79.1) |

| Working (part or full time) | 124 (35.9) | 81 (35.2) | 43 (37.4) |

| Married or living with partner | 217 (62.9) | 149 (64.8) | 68 (59.1) |

| Low Perceived Income§ | 78 (22.6) | 56 (24.3) | 22(19.1) |

| Comfort with Internet Use† | 4.3(1.1) | 4.3(1.1) | 4.3(1.2) |

| Greenville VA Healthcare Center Patient‡ | 76(22.0) | 50 (21.7) | 26 (22.6) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 33.9 (7.4) | 33.9 (7.5) | 33.9 (7.1) |

| Number of Self-Reported Comorbidities^ | 3.90 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.6) |

| Fair or Poor Self-Rated Health | 101 (29.3) | 65 (28.3) | 36 (31.3) |

| Duration of Arthritis Symptoms (years) | 16.4 (11.2) | 16.3 (11.6) | 16.6 (12.4) |

| Primary and Secondary Outcomes | |||

| WOMAC Total (Range 0–96) | 47.5 (16.3) | 47.8 (16.6) | 46.8 (15.9) |

| WOMAC Pain (Range 0–20) | 9.9 (3.4) | 10.0 (3.4) | 9.7 (3.5) |

| WOMAC Function (Range 0–68) | 33.3 (12.4) | 33.5 (12.7) | 32.8 (12.0) |

| 30-Second Chair Stand Test (# stands) | 7.8 (3.8) | 7.8 (3.7) | 7.8 (4.0) |

| 40m Fast-Paced Walk (seconds) | 40.7 (16.9) | 40.1 (17.4) | 40.1 (16.0) |

| Timed Up-and-Go Test (seconds) | 12.3 (5.9) | 12.3 (5.9) | 12.3 (5.8) |

| Stair Climb Test (seconds) | 9.2 (4.8) | 9.1 (4.6) | 9.3 (5.2) |

| 6-Minute Walk Test (meters) | 308 (131) | 306 (135) | 310 (125) |

| Physical Activity for the Elderly Scale | 148 (91.2) | 151 (94.0) | 142 (85.4) |

Majority African American: Total N=219, STEP=KOA N=149, AE N=70

Self-report of “just meet basic expenses” or “don’t even have enough to meet basic expenses.”

1=”not at all” to 5=”very” comfortable

Other participants’ primary clinical site was the Durham VA Healthcare Center

From Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (Sangha et al., 2003); list of 13 medical conditions plus up to 2 optional “other” conditions WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

Missing data: 2 participants missing age (STEP-KOA n=2), 5 missing race (STEP-KOA n=3, AE Control n=2), 4 missing ethnicity (STEP-KOA n=2, AE Control n=2), 4 missing perceived income (STEP-KOA n=3, AE Control n=1), 28 missing comfort with internet use (STEP-KOA n=19, AE Control n=9), 1 missing self-rated health (STEP-KOA n=1), 3 missing duration of arthritis symptoms (STEP-KOA n=1, AE Control n=2). 1 participant missing WOMAC total (STEP-KOA n=1), 1 missing chair stand test (STEP-KOA n=1), 3 missing 40 meter walk (STEP-KOA n=1, AE Control n=2), 2 missing timed up-and-go test (AE Control n=2), 22 missing stair climb test (STEP-KOA n=16, AE Control n=6), 1 missing 6-minute walk test (STEP-KOA n=1), and 1 missing PASE total (STEP-KOA n=1)

Normative values for physical function tests: 30-second chair stand: 13–14 stands in adults age 60–79; 40m walk test: 19–23 seconds in adults age 60–79; Timed Up-and Go: 8–9 seconds in adults age 60–79;Stair climb test:8.7–10.2 for healthy men and women; 6 minute walk test: 471–572m for adults age 60–79

Adverse Events.

Adverse event information was obtained through patient report (during outcome assessment or intervention contacts) and the VA electronic medical record. Initial determinations of severity and study-relatedness were made by the principal investigator (and co-investigators if needed); these were submitted to the Institutional Review Board for final determination.

Statistical Analyses

Sample Size.

For sample size calculations we used methods appropriate for Analysis of Covariance type analyses (35). Based on previous data, alpha=0.05, 80% power, 20% dropout and a within patient correlation of WOMAC of 0.40, standard deviation of 17.5, we estimated that n=345 participants (230 in STEP-KOA, 115 in AE) were needed to detect an effect size difference of 0.33 at 9-months (36–38). This corresponds to a 5.8 point difference in mean total WOMAC scores at 9-months between arms. We were also powered to detect medium effect size differences in secondary study outcomes.

Analysis Approach.

All analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and conducted on an intent-to-treat basis, involving all randomly assigned participants using all data up to 9-month follow-up or last available measurement (39, 40) (40). Our analytic strategy implicitly accommodates missingness when related to prior outcome, or to other baseline covariates included in the model (missing at random (MAR)). For primary and continuous secondary outcomes, linear mixed longitudinal models were used. Predictors in all models included dummy coded time effect(s) for each follow-up time point and an indicator variable for STEP-KOA interacting with the time effect(s) (see Appendix A). To account for repeated measures within participants we fit an unstructured covariance structure. Our primary inference for all analyses was based on the STEP-KOA by 9-month follow-up time indicator parameter, which is the estimated difference between STEP-KOA and AE at 9-month follow-up. This model assumes study arms have equal baseline means, which is appropriate for a randomized control trial and is equivalent in efficiency to an ANCOVA model (41, 42). Final models also included stratification variables for site and gender.

Missing Data.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis for the primary analysis using a multiple imputation approach that included additional baseline variables beyond those in our random effects models to strengthen the MAR assumption. The MAR imputation assumes the effectiveness of STEP-KOA participants missing the outcome to be similar to those in that arm remaining in the trial. Due to the magnitude of loss to follow-up in the STEP-KOA arm, we also conducted a reference-based imputation to examine a plausible missing-not-at-random (MNAR) assumption where STEP-KOA participants missing the outcome were assumed to have the effectiveness of AE participants (see Appendix A) (43).

RESULTS

Participants, Retention and Intervention Delivery

We identified 4,800 potentially eligible patients from VA electronic medical records, and an additional 58 participants were referred by a health care provider or self-referred (Figure 1). Of 1,665 Veterans who were mailed a letter or referred to the study, 345 were eligible, enrolled and randomized. Characteristics of enrolled participants are shown in Table 1. Proportions of participants completing follow-up assessments were: 3-months – 75.6% (70.4% STEP-KOA, 86.0% AE), 6-months – 75.4% (70.0%% STEP-KOA, 86.0% AE), 9-months – 74.2% (70.4% STEP-KOA, 81.7% AE). Among 230 participants in the STEP-KOA group, N=150 (65%) progressed to the Step 2 intervention (N=114 at 3-months and N=36 at 6-months), and of those who progressed to Step 2 at 3-months, N=81 (71.1%) progressed to Step 3 (Figure 2). We could not assess responder status for 41 participants (17.8%) who missed both 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments, N=24 (10.1%) who missed 3-month assessments only and N=25 (10.9%) who missed 6-month assessments only. Only N=23 (10%) were responders at 3- and 6-months and remained in Step 1 for the entire study.

Figure 2:

Numbers of Participants Meeting Criteria for Clinically Relevant Response by Time Point in STEP-KOA Group

Among STEP-KOA group participants, 166 (72%) accessed the website during the study period, with median of 2.0 days of access [1st and 3rd quartiles: 0.0, 33.0]. Among participants who accessed the website at least once (n=166), the median days of access was 11.0 [1st and 3rd quartiles: 1.0, 44.0]. Among participants who advanced to Step 2 (n=150), the mean number of telephone sessions completed (out of 6 possible) was 3.8 (SD=1.7). Among participants who advanced to Step 3 (n=81), 42 (51.9%) attended at least one PT session, with a mean of 2.2 sessions (SD=2.7) out of a maximum of 7.

Adverse Events

There was 1 study-related adverse event (non-serious); a participant in the STEP-KOA group reported increased hip pain after doing study exercises but did not seek medical care or discontinue the study.

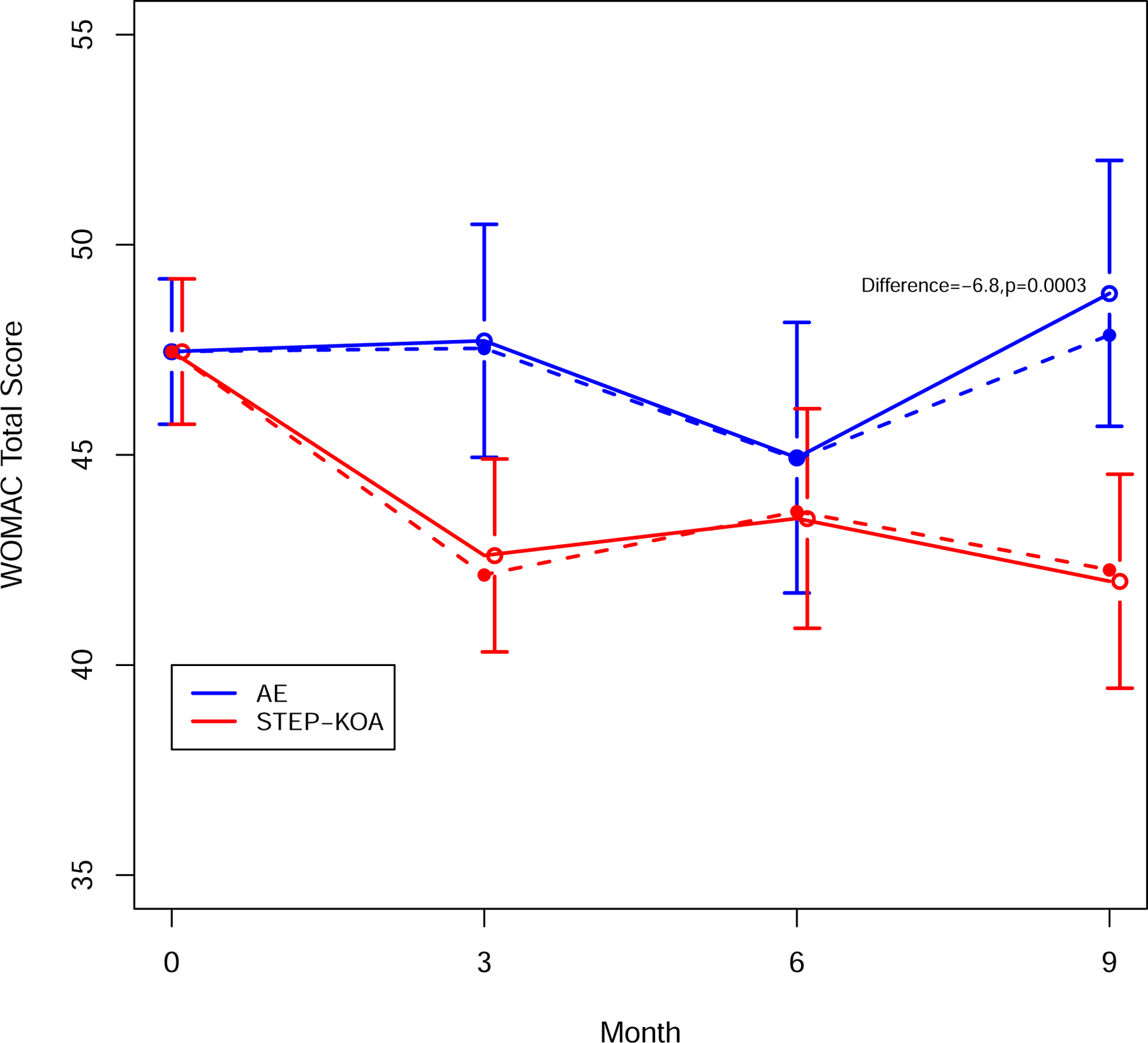

Primary Outcome: WOMAC Total Score

At 9 months, the estimated mean improvement in WOMAC total score was −5.5 points (95% Confidence Interval (CI) −7.7,−3.2) in the STEP-KOA arm and 1.4 points (95% CI −1.6,4.3) in the AE Control arm, with an estimated mean difference of −6.8 points (95% CI −10.5, −3.2; p=0.0003) between arms (Table 2; Figure 3). At 6 months there was improvement in both treatment arms compared to baseline, with the mean score for the AE Control arm worsening between 6 and 9 months. Similar results were found for the MAR imputation using the multiply imputed datasets at 9-months (mean difference = −6.7 (95% CI, −10.4, −3.0; p=0.0004). For the MNAR imputation where we assumed STEP-KOA arm participants who dropped out had similar efficacy trajectories as AE control, the estimated mean difference at 9-months was −4.9 (95% CI, −8.4, −1.4; p=0.006).

Table 2. Estimated Means and Mean Differences [95% CI] of Outcomes for STEP-KOA and AE Control Arms by Time Point from Linear Mixed Longitudinal Models; Linear mixed models.

included dummy coded time effect(s) for each of the follow-up time points and an indicator variable for STEP-KOA interacting with the time effect(s), centered stratification variables for site and gender and an unstructured covariance.

| Outcome | STEP-KOA | AE Control | Mean Difference (STEP-KOA – AE Control) (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMAC Total Subscale * | ||||

| Baseline | 47.5 | 47.5 | ||

| 3 month change from baseline | −4.9(−6.8,−2.9_ | 0.3(−2.3,2.8) | −5.1(−8.2, −2.0) | |

| 6 month change from baseline | −4.0(−6.3,−1.6) | −2.5(−5.6,0.5) | −1.4(−5.2, 2.3) | |

| 9 month change from baseline | −5.5(−7.7,−3.2) | 1.4(−1.6,4.3) | −6.8(−10.5, −3.2) | 0.0003 |

| WOMAC Pain Subscale ** | ||||

| Baseline | 9.9 | 9.9 | ||

| 3 month change from baseline | −1.0(−1.5,−0.5) | −0.1(−0.7,0.5) | −0.9 (−1.7, −0.1) | |

| 6 month change from baseline | −1.2(−1.8,−0.6) | −0.7(−1.5,0.0) | −0.5 (−1.4, 0.5) | |

| 9 month change from baseline | −1.0(−1.5,−0.5) | 0.4(−0.3,1.1) | −1.4 (−2.3, −0.6) | |

| WOMAC Function Subscale *** | ||||

| Baseline | 33.3 | 33.3 | ||

| 3 month change from baseline | −3.2(−4.7,−1.7) | 0.4(−1.5,2.4) | −3.6 (−6.0, −1.3) | |

| 6 month change from baseline | −2.4(−4.1,−0.6) | −1.3(−3.5,0.9) | −1.1 (−3.8, 1.7) | |

| 9 month change from baseline | −3.7(−5.4,−2.0) | 1.0(−1.3,3.2) | −4.6 (−7.4, −1.9) | |

| Physical Activity for the Elderly Scale ^ | ||||

| Baseline | 148.1 | 148.1 | ||

| 3 month change from baseline | 0.1(−11.5,11.7) | 0.6(−14.1,15.2) | −0.5 (−18.3, 17.3) | |

| 6 months change from baseline | 4.5(−8.2,17.2) | 13.2(−2.9,29.2) | −8.6 (−28.4, 11.1) | |

| 9 month change from baseline | 24.6(12.3,37.0) | 14.3(−1.8,30.4) | 10.3 (−9.5, 30.1) | |

| 30-Second Chair Stand Test (# stands) ^^ | ||||

| Baseline | 7.8 | 7.8 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −0.2(−0.8,0.4) | −0.6(−1.3,0.1) | 0.4 (−0.6, 1.3) | |

| 40m Fast-Paced Walk (seconds) ^^^ | ||||

| Baseline | 40.8 | 40.8 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −0.7(−3.2,1.8) | 1.6(−1.5,4.7) | −2.3 (−6.1, 1.5) | |

| Timed Up-and-Go Test (seconds) + | ||||

| Baseline | 12.3 | 12.3 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −0.5(−1.4,0.4) | 0.5(−0.7,1.6) | −0.9 (−2.3, 0.5) | |

| Stair Climb Test (seconds) ++ | ||||

| Baseline | 9.2 | 9.2 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −0.6(−1.3,0.0) | −0.1(−1.0,0.7) | −0.5 (−1.5, 0.5) | |

| 6-Minute Walk Test (meters) +++ | ||||

| Baseline | 307.2 | 307.2 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −.5(−26.2,15.3) | −15.5(−42.2,11.2) | 10.1 (−23.7, 43.8) |

Missing follow-up data:

Month 3: 84 participants (68 in STEP-KOA and 16 in AE Control); Month 6: 85 participants (69 in STEP-KOA and 16 in AE Control); Month 9: 89 participants (68 in STEP-KOA and 21 in AE Control)

Month 3: 83 participants (67 in STEP-KOA and 16 in AE Control); Month 6: 83 participants (68 in STEP-KOA and 15 in AE Control); Month 9: 88 participants (67 in STEP-KOA and 21 in AE Control).

Month 3: 84 participants (68 in STEP-KOA and 16 in AE Control); Month 6: 85 participants (69 in STEP-KOA and 16 in AE Control); Month 9: 89 participants (68 in STEP-KOA and 21 in AE Control)

Month 3: 83 participants (67 in STEP-KOA and 16 in AE Control); Month 6: 83 participants (68 in STEP-KOA and 15 in AE Control); Month 9: 88 participants (67 in STEP-KOA and 21 in AE Control)

Month 9: 137 participants (101 in STEP-KOA and 36 in AE Control).

Month 9: 148 participants (109 in STEP-KOA and 39 in AE Control).

Month 9: 145 participants (106 in STEP-KOA and 39 in AE Control).

Month 9: 167 participants (120 in STEP-KOA and 47 in AE Control).

Month 9: 9 are missing for 138 participants (101 in STEP-KOA and 37 in AE Control).

Figure 3:

WOMAC Total Score By Study Group and Time Point

Secondary Outcomes and Physical Activity

Mean improvement was greater in STEP-KOA compared to AE Control at 9-months for both the WOMAC pain subscale (mean difference = −1.4 (95% CI, −2.3, −0.6;) and the WOMAC physical function score (mean difference = −4.6 (95% CI, −7.4, −1.9;, Table 2). Both measures followed similar patterns to the overall WOMAC scores over time. For objective physical function measures and PASE we found no differences between arms (Table 2). Participants in the STEP-KOA group had a mean reduction at 9-months in self-reported pain during the stair climb test, compared to the AE control group (Table 3); there were no significant differences between study arms for pain ratings during other function tests.

Table 3. Estimated Means and Mean Differences [95% CI] of Pain Outcome after completion of Functional tests for STEP-KOA and AE Control Arms by Time Point from Linear Mixed Longitudinal Models; Linear mixed models.

included dummy coded time effect(s) for each of the follow-up time points and an indicator variable for STEP-KOA interacting with the time effect(s), centered stratification variables for site and gender and an unstructured covariance.

| Outcome | STEP-KOA | AE Control | Mean Difference (STEP-KOA – AE Control) (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain after 30-Second Chair Stand Test * | ||||

| Baseline | 5.4 | 5.4 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −0.3[−0.7,0.2] | −0.0[−0.5,0.5] | −0.3 (−0.9, 0.4) | 0.45 |

| Pain after 40m Fast-Paced Walk ** | ||||

| Baseline | 4.4 | 4.4 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −0.5[−0.9,−0.0] | −0.0[−0.6,0.5] | −0.4 (−1.1, 0.2) | 0.21 |

| Pain after Timed Up-and-Go Test *** | ||||

| Baseline | 4.1 | 4.1 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −0.1[−0.5,0.3] | 0.1[−0.4,0.6] | −0.2 (−0.9, 0.4) | 0.49 |

| Pain after Stair Climb Test ^ | ||||

| Baseline | 4.8 | 4.8 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −0.6[−1.0,−0.1] | 0.2[−0.4,0.7] | −0.8 (−1.5, −0.0) | 0.04 |

| Pain after 6-Minute Walk Test ^^ | ||||

| Baseline | 5.3 | 5.3 | ||

| 9 month change from baseline | −0.7[−1.2,−0.2] | 0.0[−0.6,0.7] | −0.7 (−1.5, 0.1) | 0.07 |

Missing 9-Month Follow-Up Data:

Follow-up data at month 9 are missing for 167 participants (118 in STEP-KOA and 49 in AE Control)

Follow-up data at month 9 are missing for 147 participants (108 in STEP-KOA and 39 in AE Control)

Follow-up data at month 9 are missing for 145 participants (106 in STEP-KOA and 39 in AE Control)

Follow-up data at month 9 are missing for 167 participants (120 in STEP-KOA and 47 in AE Control)

Follow-up data at month 9 are missing for 173 participants (123 in STEP-KOA and 50 in AE Control)

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have supported the effectiveness of individual exercise and PT interventions for knee OA (7, 8), but we believe this is the first study to evaluate an adaptive, stepped approach to delivering these treatments. Participants in the STEP-KOA group reported modest improvements in the primary outcome (WOMAC) at 9-month follow-up (44), relative to the control group; these improvements were comparable to prior studies of exercise interventions for knee OA (45, 46). We acknowledge this between-group difference is on the lower end of clinically relevant improvement for WOMAC (47). There were no between-group differences in objective physical function tests or self-reported physical activity. However, self-reported pain during a stair climb test was lower for the STEP-KOA group compared with the control group.

Although there were improvements in WOMAC function scores in the STEP-KOA group, there were no between-group differences in objective physical function tests. These results suggest participants perceived less difficulty in performing daily activities, which is an important patient-centered outcome, even though their performance across several tasks did not differ from the control group. This study sample reported high levels of OA symptoms, functional limitations and comorbidities at baseline, and it is possible that the intervention was not intense enough to yield improvements in physical performance tests in this group. In the STEP-KOA group, but not the control group, mean ratings of pain following completion of the stair climbing test declined between baseline and 9months, with a similar trend for the 6-minute walk test. Therefore, although intervention group participants did not improve performance of these tasks compared with baseline, there is some indication that they completed the tasks with less pain.

This study also provided novel data on proportions of individuals with knee OA meeting OMERAC-OARSI response criteria (22) following different exercise-based interventions. Although we observed some improvement in WOMAC scores at 3-months, only one-third of STEP-KOA participants met response criteria for clinically relevant improvement (and some of these had “regressed” by 6 months), suggesting that a more intensive approach is needed for many patients. Improvements following Step 1 were smaller than in an initial study of the same internet-based exercise program (48); this may be due to greater engagement with the program among participants in the prior study. Of those who progressed to telephone-based physical activity coaching, about half met response criteria after that Step, indicating that more intensive therapy may be appropriate for a substantial proportion of patients. In total, 81 participants (35%) progressed to Step 3 PT visits. Given challenges with access to PT services in some contexts, these results and suggest health systems may benefit from engaging patients in other exercise-based interventions prior to PT referral.

Participants’ use of the internet-based exercise program was limited, similar to that observed in a prior study (49). This is interesting given that there were some improvements in WOMAC scores by 3 months. It is possible that participants continued to perform recommended exercises without frequently accessing the website. However, there is still a need to understand the types of features that most successfully engage patients in technology-guided independent exercise programs. For patients advancing to Step 3, attendance at PT visits was also limited. Participants commonly did not want to come to an in-person PT appointment, suggesting that delivering these visits remotely may help to boost attendance and potentially intervention impact.

Strengths of the study include the innovative intervention approach, proactive outreach to patients for recruitment and high proportion of African American participants. There are limitations to this study. The study sample included VA health care users at two sites, the majority of whom were men, and this may limit generalizability. In this pragmatic study, we did not obtain radiographs, and prior radiograph reports were not consistently available for participants in VA electronic medical records. Therefore, we were unable to definitively determine the presence of radiographic knee OA or define disease severity based on criteria such as Kellgren-Lawrence. Although there are limitations to this approach, we believe the combination of a diagnosis in the EHR, patient self-report of clinician diagnosis, and current knee pain is a reasonable strategy for identifying patients under care for knee OA in a healthcare system. There was a higher-than-expected dropout rate of 25%. Although we conducted robust analyses to accommodate dropout and missing data, it is still possible that unmeasured, important characteristics could have differed between dropouts and completers. There was a higher dropout rate in the STEP-KOA group, which may have indicated lack of interest in the intervention among those participants.

In summary, we found that a novel stepped exercise program, with intensification of the intervention approach when participants did not meet response criteria, resulted in modest improvements in self-reported pain and function. This type of stepped care strategy could preserve health care resources and tailor programs to patients’ needs. However, engagement with STEP-KOA intervention components (particularly Steps 1 and 3) was limited, which may have reduced the impact on outcomes. Further work is needed to identify effective strategies to boost adherence to and maintenance following this and other exercise-based interventions for knee OA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study team expresses gratitude to study team members Battista Smith, MPH, Amy Miles, MPH, Jennifer Chapman, BASW, Aviel Alkon, BS, Jenny Zervakis, PhD, Sarah Gonzales, BA, Carolina Nagle, BS, Nadya Majette Elliott, MPH, Karen Juntilla, AAS, BA, M.Ed, Kimberlea Grimm, MHS, Katina Robinson, MS, Courtney White-Clark, MS and Carrie May, MPH; Mr. David Cooper for his support of the internet-based exercise training program, and study physical therapists Jamie St. John, PT, Tawny Kross, PT, John Sizemore, DPT, Casey Turner, PT, Benjamin Soydan, PT, and Mia C. Talcott. The study team also thanks all of the participants taking part in this research.

Funding Source:

Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service (IIR 14-091).

Role of the Funding Source:

The funder, VA Health Services Research and Development Service, did not determine the study design, conduct or reporting.

Funding

Research reported in this manuscript was funded through an Investigator Initiated Award (IIR 14-091) from the Health Services Research and Development Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The statements presented in this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The Department of Veterans Affairs did not have a role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing the manuscript. KDA receives support from National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Core Center for Clinical Research P30AR072580 and VA Health Services Research and Development Research Career Scientist Award 19-332. KDA, CJC, SW, BS, and CVH receive support from the Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (ADAPT) (CIN 13-410) at the Durham VA Health Care System. KC, KSH, HMH, and MM receive support from the NIH/NIA OAIC program AG028716)

Abbreviations

- AE

Arthritis Education

- EHR

electronic health record

- IBET

Internet-Based Exercise Training

- MAR

Missing at Random

- MI

Multiple Imputation

- MNAR

Missing Not at Random

- mSF WOMAC

Modified Short Form of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- OMERACT-OARSI

Outcome Measures in Rheumatology group and the Osteoarthritis Research Society International

- PASE

Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly

- PT

Physical Therapy

- SMART

Specific, Measurable, Action-oriented, and Time-Bound

- STEP-KOA

STepped Exercise Program for patients with Knee OsteoArthritis

- VA

Department of Veterans Affairs

- WOMAC

Western Ontario and McMasters Universities Osteoarthritis Index

Footnotes

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research is in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Written, informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Consent to publish

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Reproducible Research Statements:

Protocol: Posted as data supplement, including list of amendments

Statistical Code: Available by contacting the corresponding author: kelli.allen@va.gov

Data: De-identified data may be available following proper regulatory approvals.

Contributor Information

Kelli D. Allen, Durham VA Health Care System, Durham, and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina..

Sandra Woolson, Durham VA Health Care System, Durham, North Carolina..

Helen M. Hoenig, Durham VA Health Care System and Duke University, Durham, North Carolina..

Dennis Bongiorni, Durham VA Health Care System, Durham, North Carolina..

James Byrd, Greenville VA Health Care Center, Greenville, North Carolina..

Kevin Caves, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina..

Katherine S. Hall, Durham VA Health Care System and Duke University, Durham, North Carolina..

Bryan Heiderscheit, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin..

Nancy Jo Hodges, Durham VA Health Care System, Durham, North Carolina..

Kim M. Huffman, Durham VA Health Care System and Duke University, Durham, North Carolina..

Miriam C. Morey, Durham VA Health Care System and Duke University, Durham, North Carolina..

Shalini Ramasunder, Durham VA Health Care System and Duke University, Durham, North Carolina..

Herbert Severson, Oregon Research Institute, Eugene, Oregon..

Courtney Van Houtven, Durham VA Health Care System and Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina..

Lauren M. Abbate, VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System and University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado..

Cynthia J. Coffman, Durham VA Health Care System and Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina..

References

- 1.Bone US and Initiative Joint. The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS), Fourth Edition Rosemont, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73(7):1323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Barbour KE, Theis KA, Boring MA. Updated projected prevalence of self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation among US adults, 2015–2040. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meneses SR, Goode AP, Nelson AE, Lin J, Jordan JM, Allen KD, et al. Clinical algorithms to aid osteoarthritis guideline dissemination. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden N, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2015;49(24):1554–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verhagen AP, Ferreira M, Reijneveld-van de Vendel EAE, Teirlinck CH, Runhaar J, van Middelkoop M, et al. Do we need another trial on exercise in patients with knee osteoarthritis?: No new trials on exercise in knee OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27(9):1266–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song J, Hochberg MC, Chang RW, Hootman JM, Manheim LM, Lee J, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in physical activity guidelines attainment among people at high risk of or having knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65(2):195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cisternas MG, Yelin E, Katz JN, Solomon DH, Wright EA, Losina E. Ambulatory visit utilization in a national, population-based sample of adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61(12):1694–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhawan A, Mather RC, Karas V 3rd, Ellman MB, Young BB, Bach BR Jr, et al. An epidemiologic analysis of clinical practice guidelines for non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthroscopy 2014;30(1):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbate LM, Jeffreys AS, Coffman CJ, Schwartz TA, Arbeeva L, Callahan LF, et al. Demographic and Clinical Factors Associated With Nonsurgical Osteoarthritis Treatment Among Patients in Outpatient Clinics. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2018;70(8):1141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Physical Therapy Association Workforce Task Force. A Model to Project the Supply and Demand of Physical Therapists, 2010–2020. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakicic JM, Tate DF, Lang W, Davis KK, Polzien K, Rickman AD, et al. Effect of a stepped-care intervention approach on weight loss in adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2012;307(24):2617–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Wu J, Yu Z, Chumbler NR, Bair MJ. Telecare collaborative management of chronic pain in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312(3):240–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bair MJ, Ang D, Wu J, Outcalt SD, Sargent C, Kempf C, et al. Evaluation of Stepped Care for Chronic Pain (ESCAPE) in Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Conflicts: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(5):682–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Wu J, Hoke S, Sutherland J, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301(20):2099–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattsson S, Alfonsson S, Carlsson M, Nygren P, Olsson E, Johansson B. U-CARE: Internet-based stepped care with interactive support and cognitive behavioral therapy for reduction of anxiety and depressive symptoms in cancer - a clinical trial protocol. BMC Cancer 2013;13:414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Korff M, Tiemens B. Individualized stepped care of chronic illness. West J Med 2000;172(2):133–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davison GC. Stepped care: doing more with less? J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68(4):580–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen KD, Bongiorni D, Caves K, Coffman CJ, Floegel TA, Greysen HM, et al. STepped exercise program for patients with knee OsteoArthritis (STEP-KOA): protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20(1):254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pham T, van der Heijde D, Altman RD, Anderson JJ, Bellamy N, Hochberg M, et al. OMERACT-OARSI initiative: Osteoarthritis Research Society International set of responder criteria for osteoarthritis clinical trials revisited. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12(5):389–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks MA, Beaulieu JE, Severson H, Wille CM, Copper D, Gau JM, et al. Web-based therapeutic exercise resource center as a treatement for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort pilot study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2014;15:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blissmer B, Hall E, Marquez DX. Behavioral theories and strategies for promoting exercise. In: Pescatello LS, Arena R, Riebe D, Thompson PD, eds. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, Ninth Edition Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip and knee. Arthritis Care and Research 2012;64(4):465–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22(3):363–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. The Journal of Rheumatology 1988;15:1833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellamy N, Campbell J, Hill J, Band P. A comparison study of telephone versus onsite completion of the WOMAC 3.0 Osteoarthritis Index. The Journal of Rheumatology 2002;29:783–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones C, RIkli R, Beam W . A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 1999;70(2):113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright AA, Cook CE, Baxter GD, Dockerty JD, Abbott JH. A comparison of 3 methodological approaches to defining major clinically important improvement of 4 performance measures in patients with hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011;41(5):319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dobson F, Hinman RS, Roos EM, Abbott JH, Stratford P, Davis AM, et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21(8):1042–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1993;46:153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The self-administered comorbidity questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2003;49(2):156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borm GF, Fransen J, Lemmens W. A simple sample size formula for analysis of covariance in randomized clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2007;60(12):1234–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen KD, Bosworth HB, Brock DS, Chapman JG, Chatterjee R, Coffman CJ, et al. Patient and Provider Interventions for Managing Osteoarthritis in Primary Care: Protocols for Two Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen KD, Bongiorni D, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ, Datta SK, Edelman D, et al. Group Versus Individual Physical Therapy for Veterans With Knee Osteoarthritis: Randomized Clinical Trial. Phys Ther 2016;96(5):597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen KD, Oddone EZ, Coffman CJ, Datta SK, Juntilla KA, Lindquist JH, et al. Telephone-based self-management of osteoarthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 2010;153:570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ICH E9 Expert Working Group. ICH harmonised tripartite guideline - Statistical principles for clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine 1999;18:1905–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with MIssing Data Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu GF, Lu K, Mogg R, Mallick M, Mehrotra DV. Should baseline be a covariate or dependent variable in analyses of change from baseline in clinical trials ? Stat Med 2009;28(20):2509–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird LM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Analysis Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Kelly M, Ratitch B. Clincial Trials with Missing Data: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angst F, Aeschlimann A, Stucki G. Smallest detectable and minimal clinically important differences of rehabilitation intervention with their implications for required sample sizes using WOMAC and SF-36 quality of life measurement instruments in patients with osteoarthritis of the lower extremities. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45(4):384–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Legault C, Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, DeVita P, et al. Effects of intensive diet and exercise on knee joint loads, inflammation, and clinical outcomes among overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310(12):1263–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uthman OA, van der Windt DA, Jordan JL, Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Peat GM, et al. Exercise for lower limb osteoarthritis: systematic review incorporating trial sequential analysis and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;347:f5555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Angst F, Aeschlimann A, Michel BA, Stucki G. Minimal clinically important rehabilitation effects in patients with osteoarthritis of the lower extremity. The Journal of Rheumatology 2002;29:131–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brooks MA, Beaulieu JE, Severson HH, Wille CM, Cooper D, Gau JM, et al. Web-based therapeutic exercise resource center as a treatment for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allen KD, Arbeeva L, Callahan LF, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Heiderscheit BC, et al. Physical therapy vs internet-based exercise training for patients with knee osteoarthritis: results of a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2018;26(3):383–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.