During the fast block to polyspermy, fertilization activates a phospholipase C (PLC) to signal a depolarization in Xenopus laevis eggs. Komondor and colleagues investigated how fertilization activates PLC and ruled out the conventional signaling pathways including tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 or G-protein activation of PLC β1/3.

Abstract

Fertilization of an egg by more than one sperm, a condition known as polyspermy, leads to gross chromosomal abnormalities and is embryonic lethal for most animals. Consequently, eggs have evolved multiple processes to stop supernumerary sperm from entering the nascent zygote. For external fertilizers, such as frogs and sea urchins, fertilization signals a depolarization of the egg membrane, which serves as the fast block to polyspermy. Sperm can bind to, but will not enter, depolarized eggs. In eggs from the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis, the fast block depolarization is mediated by the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel TMEM16A. To do so, fertilization activates phospholipase C, which generates IP3 to signal a Ca2+ release from the ER. Currently, the signaling pathway by which fertilization activates PLC during the fast block remains unknown. Here, we sought to uncover this pathway by targeting the canonical activation of the PLC isoforms present in the X. laevis egg: PLCγ and PLCβ. We observed no changes to the fast block in X. laevis eggs inseminated in inhibitors of tyrosine phosphorylation, used to stop activation of PLCγ, or inhibitors of Gαq/11 pathways, used to stop activation of PLCβ. These data suggest that the PLC that signals the fast block depolarization in X. laevis is activated by a novel mechanism.

Introduction

For most sexually reproducing animals, only eggs fertilized by one sperm can successfully initiate embryonic development (Hassold et al., 1980; Rojas et al., 2021). Fertilization of an egg by more than one sperm, a condition known as polyspermy, is lethal to the developing embryo (Wong and Wessel, 2006). To prevent these catastrophic consequences, eggs have evolved various processes called polyspermy blocks that stop sperm from entering already-fertilized eggs (Wong and Wessel, 2006; Evans, 2020; Fahrenkamp et al., 2020). The molecular details of these processes are still being uncovered.

Two common polyspermy blocks are named based on their relative timing: the “fast” and “slow” blocks to polyspermy (Jaffe and Gould, 1985; Bianchi and Wright, 2016). The eggs of nearly all sexually reproducing animals use the slow block to polyspermy, which occurs minutes after fertilization and involves the exocytosis of cortical granules from the egg and establishment of a physical barrier around the nascent zygote (Wong and Wessel, 2006; Evans, 2020). Eggs from externally fertilizing animals also use the fast block to polyspermy (Wozniak and Carlson, 2020). During the fast block to polyspermy, fertilization immediately activates depolarization of the egg plasma membrane (Jaffe, 1976). This membrane potential change allows sperm to bind to, but not penetrate, the egg (Jaffe, 1976). We are still uncovering the molecular pathways that underlie this process Wozniak and Carlson, 2020; Tembo et al., 2021). Here, we sought to uncover how fertilization signals the fast block in eggs from the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis.

We have previously demonstrated that fertilization of X. laevis eggs opens the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel TMEM16A (Wozniak et al., 2018a), allowing Cl− to leave the cell and depolarize its membrane. TMEM16A channels are activated by elevated cytoplasmic Ca2+, and fertilization opens these channels via phospholipase C (PLC)–mediated activation of the inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to enable Ca2+ release from ER (Wozniak et al., 2018b). Notably, both the fast and slow polyspermy blocks in X. laevis eggs require PLC activation and IP3-signaled Ca2+ release from the ER (Nuccitelli et al., 1993; Fontanilla and Nuccitelli, 1998; Wozniak et al., 2018b).

Conflicting data have been published regarding how fertilization in X. laevis activates egg PLCs. For example, by imaging cytoplasmic Ca2+, Glahn and colleagues reported that injecting X. laevis eggs with tyrosine kinase inhibitors lavendustin A or tyrphostin B46 stopped the fertilization-evoked Ca2+ wave (Glahn et al., 1999). Similarly, Sato and colleagues reported that inhibiting tyrosine phosphorylation with 100 µM genistein completely prevented embryonic development of X. laevis eggs (Sato et al., 2000). Further work suggested that fertilization in X. laevis eggs activates PLCγ via tyrosine phosphorylation and that PLCγ specifically was necessary for the Ca2+ increase in the egg following fertilization (Sato et al., 2000). These experiments gave rise to the hypothesis that sperm bind to the extracellular domain of uroplakin III, which signals activation of an Src family kinase which then tyrosine phosphorylates PLCγ (Mahbub Hasan et al., 2005). However, Runft and colleagues imaged cytoplasmic Ca2+ in X. laevis eggs and reported that stopping either PLCγ activity by overexpressing the Src-homology 2 (SH2) domain or PLCβ activation with a Gαq targeting antibody failed to prevent the fertilization-signaled increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Runft et al., 1999). These data suggest that neither tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ nor Gαq activation of PLCβ is needed for the fast block.

Here, we sought to uncover the connection between fertilization and PLC activation during the fast block in X. laevis eggs. From analysis of existing transcriptomics and proteomics datasets, we identified three PLC isoforms in X. laevis eggs: PLCγ1, PLCβ1, and PLCβ3. We then determined which of the signaling pathways upstream of each PLC subtype were required for the fast block in X. laevis. We report that the canonical activation pathways for neither PLCγ1 nor PLCβ are required for the fast block in X. laevis eggs. Our findings indicate that PLC activation during X. laevis fertilization proceeds through a new, yet-to-be-determined pathway.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Genistein was obtained from Alfa Aesar (Thermo Fisher Scientific), lavendustin A/B was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and human chorionic gonadotropin was purchased from Covetrus. Leibovitz’s-15 (L-15) medium (without L-glutamine) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. YM-254890 was purchased from Tocris Bio-Techne Corporation. U73122 was obtained from Cayman Chemical. All other materials, unless noted, were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Solutions

Modified Ringer’s (MR) solution was used as the base for all fertilization and recording assays in this study (100 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM KCl, 2.0 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgCl2, and 5.0 mM HEPES, pH 7.8). The MR solution was filtered using a sterile, 0.2 µm polystyrene filter (Heasman et al., 1991) and diluted for experimentation as follows: fertilization recordings were performed in 20% MR (MR/5) with or without indicated inhibitors. Following whole-cell recordings, developing embryos were stored and monitored in 33% MR (MR/3).

OR2 and ND96 solutions were used for collection and storage of immature oocytes. OR2 (82.5 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6) and ND96 (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, and gentamycin, pH 7.6) were filtered using a sterile, 0.2 μM polystyrene filter.

MR solutions containing inhibitors were prepared from concentrated stock solutions made in DMSO. Final DMSO content was maintained below 2% solution, a concentration that does not interfere with the fast block (Wozniak et al., 2018b).

Animals

All animal procedures were conducted using acceptable standards of humane animal care and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh. X. laevis adults were obtained commercially from Nasco or Xenopus 1 and housed at 20°C with a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle.

Collection of gametes

Eggs

To obtain fertilization-competent eggs, sexually mature X. laevis females were induced to ovulate via injection of 1,000 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin into the dorsal lymph sac and incubated overnight at 14–16°C for 12–16 h (Wozniak et al., 2017). Females typically begin to lay eggs within 2 h after being moved to room temperature. Eggs were collected on dry Petri dishes and used within 10 min of laying, a timeframe meant to maximize egg health and reduce variability.

Sperm

To obtain sperm, testes were harvested from sexually mature X. laevis males (Wozniak et al., 2017). Males were euthanized by a 30-min immersion in 3.6 g/liter tricane-S (MS-222), pH 7.4, before testes were harvested and cleaned. Testes were then stored at 4°C in MR for use on the day of the dissection or in L-15 Leibovitz’s medium without glutamine for use up to 1 wk later.

Oocytes

X. laevis oocytes were collected by procedures described in previous manuscripts (Tembo et al., 2019). Briefly, ovarian sacs were obtained from X. laevis females anesthetized with a 30-min immersion in 1.0 g/liter tricaine-S (MS-222) at pH 7.4. Ovarian sacs were manually pulled apart and incubated for 90 min in 1 mg/ml collagenase in ND96 supplemented with 5 mM sodium pyruvate and 10 mg/ml of gentamycin. Collagenase was removed by repeated washes with OR2, and healthy oocytes were sorted prior to storage at 14°C in ND96 supplemented with sodium pyruvate and gentamycin.

Sperm preparation and in vitro fertilization

For in vitro fertilization during whole-cell recordings, sperm suspensions were made by macerating 1/10 of the X. laevis testis in 200 μl MR/5. This solution was kept at 4°C for up to 1 h for use. Up to three sperm additions were added to each egg while recording, with ∼10 min between additions. To monitor for development after recording, eggs inseminated during whole-cell recordings were transferred to MR/3 and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Development was assessed based on the appearance of cleavage furrows (Wozniak et al., 2017).

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological recordings were made using TEV-200A amplifiers (Dagan Co.) and digitized by Axon Digidata 1550A (Molecular Devices). Data were acquired with pClamp Software (Molecular Devices) at a rate of 5 kHz. Pipettes used to impale the X. laevis eggs for recordings were pulled from borosilicate glass at a resistance of 5–15 MΩ and filled with 1 M KCl.

Whole-cell recordings

Resting and fertilization potentials were quantified ∼10 s before and after the depolarization, respectively. Depolarization rates of each recording were quantified by determining the maximum velocity of the quickest 1-mV shift in the membrane potential (Wozniak et al., 2018a).

Two-electrode voltage clamp recordings

The efficacy of inhibitors targeting PLCβ activation was screened by recording xTMEM16A currents in the two-electrode voltage clamp configuration on X. laevis oocytes clamped at −80 mV. Blue/green light was applied using a 250-ms exposure to light directed from the opE-300white LED Illumination System (CoolLED Ltd) and guided by a liquid light source to the top of the oocytes in 35-mm Petri dishes. Background-subtracted peak currents were quantified from two consecutive recordings (one before and one during application of screened inhibitors). The proportional difference between peak currents before and with inhibitor for each oocyte was used to quantify inhibition.

Polyspermy assay

To determine the incidence of polyspermy with or without inhibitors, inseminated eggs were kept for observation for 2 h following whole-cell recordings. Successful monospermic fertilization was defined by symmetrical patterns of cleavage furrows in embryos, while polyspermic fertilization was defined by asymmetric patterns of cleavage furrows (Elinson, 1975; Grey et al., 1982).

Bioinformatics

To identify PLC isoforms in X. laevis eggs, existing transcriptomic (Session et al., 2016) and proteomic (Wühr et al., 2014) datasets were quarried for “PLC” genes. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) dataset was obtained from X. laevis oocytes at different stages of development as well as from the fertilization-competent eggs (Session et al., 2016). The proteomic dataset was obtained from mature dejellied X. laevis whole-egg lysates and analyzed using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (Wühr et al., 2014).

Exogenous protein expression in X. laevis oocytes

The coding DNAs encoding the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGF-R; Gagoski et al., 2016) or the rhodopsin-muscarinic receptor type 1 chimera (opto-M1R; Morri et al., 2018) were purchased from Addgene (plasmids 67130 and 106069, respectively) and engineered into the GEMHE vector using overlapping extension PCR. The sequences for all constructs were verified by automated sequencing (Gene Wiz or Plasmidsaurus). The RNAs were transcribed using the T7 mMessage mMachine (Ambion). Defolliculated oocytes were injected with RNA and used 3 d following injection.

Removal of egg jelly

For procedures requiring the removal of jelly, eggs were incubated at room temperature for 5 min before insemination with sperm suspension prepared as described previously (Wozniak et al., 2020). Activated eggs, identified by their ability to roll so the animal pole faced up and displayed a contracted animal pole, were used for Western blot preparations. To remove the jelly, eggs were placed on 1% agar in MR/3 in a 35-mm Petri dish, in MR/3 with 45 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), pH 8.5. During BME incubation, eggs were gently agitated for 1–2 min until their external jelly visibly dissolved, as indicated by close nestling of the eggs and loss of visible jelly. To remove the BME solution, dejellied eggs were then moved with a plastic transfer pipette to a Petri dish coated with 1% agar in MR/3, pH 6.5, and agitated for an additional minute. Eggs were then transferred three times to additional agar-coated dishes with MR/3, pH 7.8, swirling gently and briefly in each.

Sample preparation and Western blot

Oocytes and eggs were lysed using a Dounce homogenizer and ice-cold oocyte homogenization buffer (OHB; 10 mM HEPES, 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors in a 1:100 dilution; Hill et al., 2005). 100 μl OHB was used per 10 eggs or oocytes. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 500 relative centrifugal force (RCF) for 5 min at 4°C, and the resulting pellet was then resuspended in 100 μl OHB. The sample was again sedimented and the supernatant from both the successive sedimentations was pooled and centrifuged at 18,213 RCF for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then sedimented again at 18,213 RCF for 15 min at 4°C. 30 μl of this supernatant was combined with 10 μl sample buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 12.5 mM EDTA, and 0.02% bromophenol blue) before incubating at 95°C for 1 min.

Samples were resolved by electrophoresis on precast 4–12% BIS-TRIS PAGE gels (Invitrogen) run in TRIS-MOPS (50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% SDS) running buffer, followed by wet transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane at 10 V for 1 h in Bolt (Invitrogen) transfer buffer. Loading was evaluated by Ponceau S. Blocking was performed for 1 h at room temperature using Superblock (Thermo Fisher Scientific) buffer. Primary antibody incubation was performed overnight at 4°C with anti-PLCγ (pY783; 1:1,000; Abcam) and secondary antibody was performed for 1 h at room temperature using goat anti-rabbit HRP (1:10,000; Invitrogen). All washes were performed using TBST (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 8). Blots were resolved using Supersignal Pico (Pierce) on a GE/Amersham 600RGB imager using chemiluminescence settings.

Quantification and statistical analyses

All electrophysiology recordings were analyzed with Igor (WaveMetrics), Prism (GraphPad), and Excel (Microsoft). Data for each experimental condition are displayed in Tukey box plot distributions, where the box contains the data between 25 and 75% and the whiskers span 10–90%. All conditions include trials that were conducted on multiple days using gametes from multiple individuals. ANOVA with post hoc Tukey honest significant difference test was used to determine differences between inhibitor treatments. Depolarization rates were log10-transformed before statistical analyses.

Imaging

X. laevis eggs and embryos were imaged using a stereoscope (Leica Microsystems) equipped with a Leica 10447157 1X objective and DFC310 FX camera. Images were analyzed using LAS (version 3.6.0 build 488) software and Photoshop (Adobe).

Online supplemental material

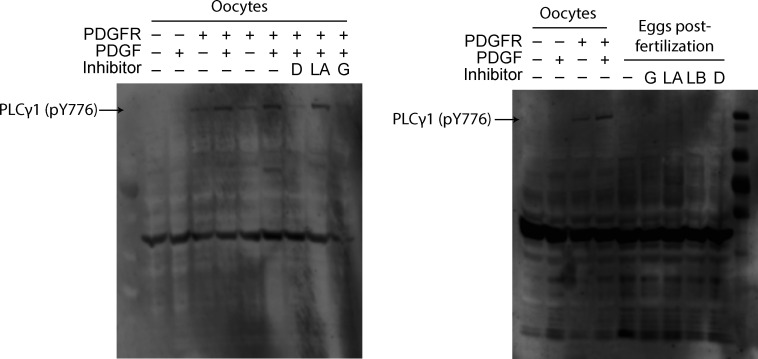

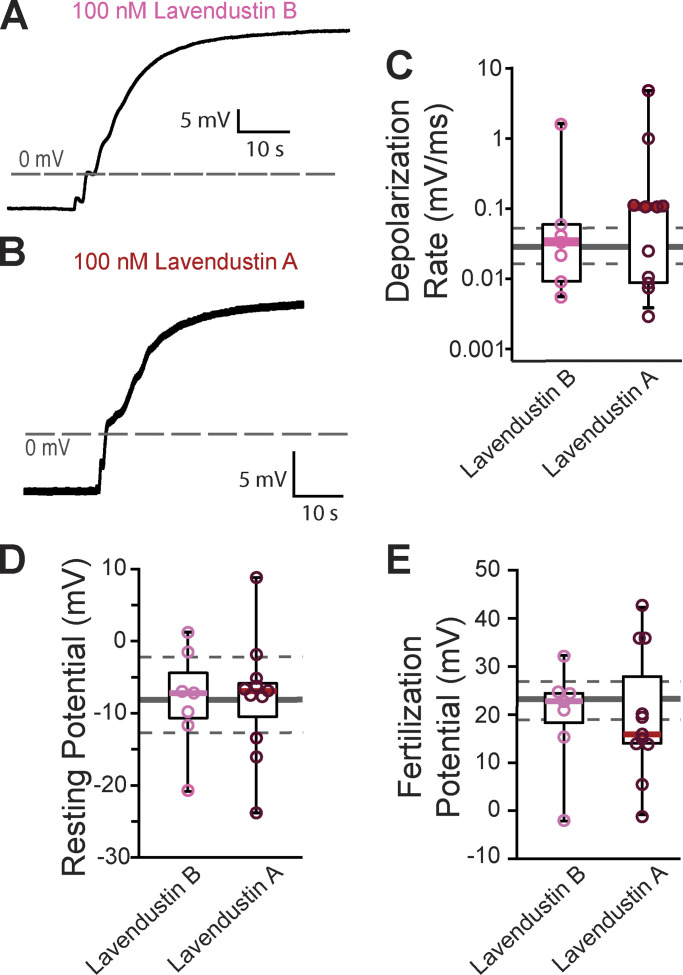

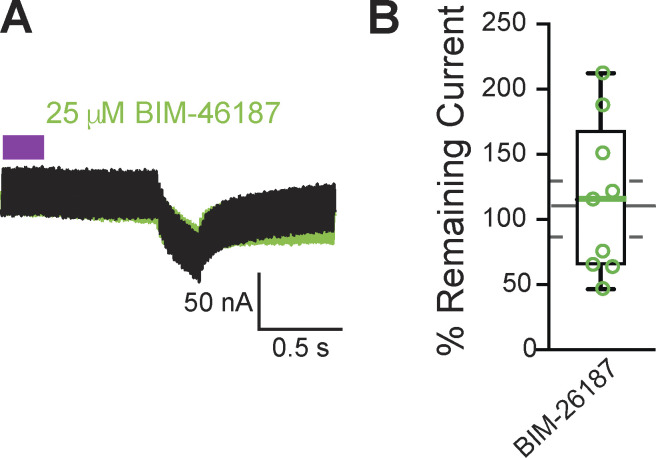

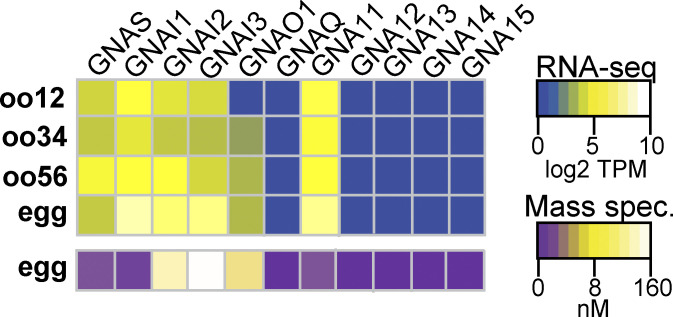

Fig. S1 shows the full Western blots probing for phosphorylation of PLCγ1 (Y776) performed on fertilized eggs to screen tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Fig. S2 includes example whole-cell recordings and associated analyses from eggs inseminated in lavendustin A or B. Fig. S3 shows an example of a two-electrode voltage clamp recording and associated analyses from recordings made to test the efficacy of BIM-46187. Fig. S4 shows a heat map display of the protein (Wühr et al., 2014) and RNA transcript (Session et al., 2016) levels for Gα subunits expressed in developing X. laevis oocytes and fertilization-competent eggs.

Figure S1.

Expanded Western blots of PLCγ phosphorylation. PLCγ1 is phosphorylated at Y776 in oocytes expressing PDGFR and stimulated with PDGF. This effect can be inhibited by dasatinib (D) and genistein (G), but not lavendustin A (LA; left). Fertilization does not induce PLCγ1 (Y776) phosphorylation in eggs (right). LB, lavendustin B.

Figure S2.

Lavendustin B or A did not alter the fast block. (A and B) Representative whole-cell fertilization signaled depolarizations in X. laevis eggs in the presence of (A) lavendustin B or (B) lavendustin A. (C–E) Tukey box plot distributions of (C) depolarization rates, (D) resting potential, and (E) fertilization potential in the presence of lavendustin B or A. Middle line denotes the median, while the box indicates 25–75% of the data, and the whiskers 10–90%. The gray solid line represents the median and the gray dashed lines denote 25–75% distribution depolarizations collected under control conditions.

Figure S3.

BIM-46187 did not inhibit Gα11 activation of PLCβ in X. laevis oocytes. (A) Representative consecutive two-electrode voltage clamp recordings in oocytes expressing opto-M1R and clamped at, before, and after a 10-min incubation in BIM-46187. The purple block indicates the time of blue/green light application. (B) Tukey box plot distributions of the percent remaining current in consecutive recordings in BIM-46187 from oocytes expressing opto-M1R. Middle line indicates median value while the box denotes 25–75% and the whiskers maximum and minimum values. The gray solid line represents the median, and the gray dashed lines denote 25–75% distribution, of the data collected under control conditions.

Figure S4.

Guanine nucleotide-binding protein gene (GNA) isoforms expressed in X. laevis eggs. Heatmaps of RNA (top) and protein (bottom) expression levels of Gα subunits at various developmental stages of egg maturation. RNA-seq data displayed as transcripts per million (TPM), and protein data shown as nanomolar concentration. Transcript levels were obtained and compiled from Session et al. (2016), while protein concentrations were from Wühr et al. (2014) through mass spectrometry.

Results

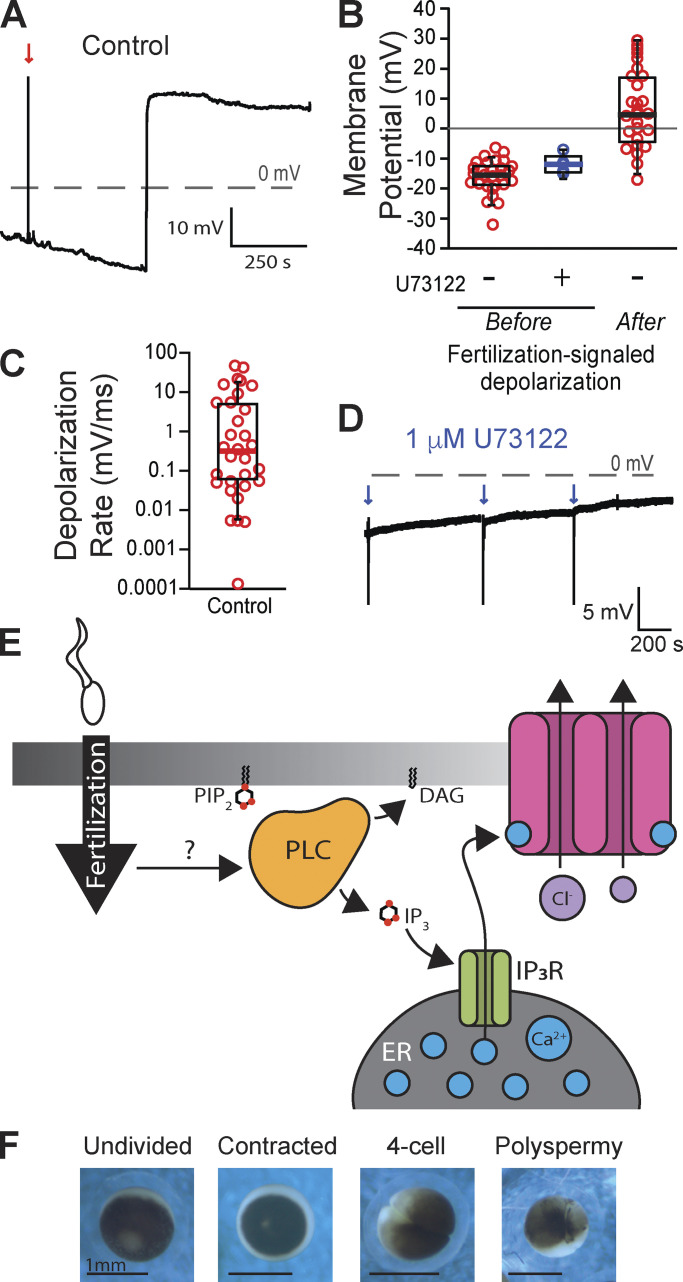

Fertilization requires PLC to signal a depolarization in X. laevis eggs

To study the fast block to polyspermy in X. laevis, we performed whole-cell recordings on eggs before and following sperm application. Sperm application during the recording resulted in a fertilization-signaled depolarization (Fig. 1 A). For eggs inseminated under control conditions, we found that the average resting potential was −15.9 ± 1.0 mV, the potential following the fertilization-signaled depolarization was 6.5 ± 2.4 mV (N = 27, Fig. 1 B), and the mean rate of depolarization was 4.4 ± 1.7 mV/ms (Fig. 1 C). We have previously demonstrated that blocking the IP3-evoked Ca2+ release from the ER, with either inhibition of PLC or the IP3 receptor, was sufficient to completely stop the fast block in X. laevis (Fig. 1 E; Wozniak et al., 2018a). Here, we similarly report that in the presence of 1 μM of the general PLC inhibitor U73122, fertilization never evoked depolarization in X. laevis eggs (N = 5, Fig. 1, B and D). However, all five eggs fertilized in U73122 developed asymmetric cleavage furrows, consistent with polyspermic fertilization (Fig. 1 F; Elinson, 1975; Grey et al., 1982). These results substantiate a requirement for PLC to activate the fast block in X. laevis eggs.

Figure 1.

Fertilization signals a PLC-mediated depolarization in X. laevis eggs. (A) Representative whole-cell recording in control conditions (diluted modified Ringer’s solution). The red arrow indicates the time of sperm addition. (B and C) Tukey box plot distributions of (B) the resting membrane potentials of eggs recorded in control conditions or in 1 μM of the PLC inhibitor U73122 and after the fertilization-evoked depolarization for control conditions, and (C) the rate of the fertilization-signaled depolarization for recordings made in control conditions. The middle line denotes the median value, the box indicates 25–75%, and the whiskers denote 10–90% (N = 28). (D) Representative whole-cell recording in 1 μM U73122. Blue arrows indicate sperm addition (N = 5). (E) PIP2 is cleaved by PLC during the fast block to create IP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG). Generation of IP3 propagates the fast block to polyspermy. (F) Representative images of an undivided, two-cell stage, and polyspermic X. laevis egg.

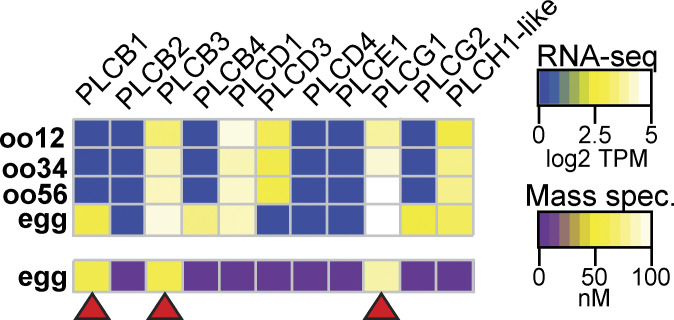

Three PLCs in the X. laevis egg are candidates for triggering the fast block

We sought to uncover how fertilization activates PLC to signal the fast block of X. laevis eggs. Because the different PLC subtypes are activated by different signaling pathways, we first sought to identify which PLC isoforms are present in X. laevis eggs. To do so, we interrogated two previously published high-throughput expression datasets. First, we examined the proteome of fertilization-competent eggs (Wühr et al., 2014) and queried for all proteins encoded by known PLC genes (Fig. 2). We found that three PLC proteins are present in the egg: PLCγ1 (encoded by the PLCG1 gene) and PLCβ1 and PLCβ3 (encoded by the PLCB1 and PLCB3 genes, respectively). PLCγ1 is the most abundant in the X. laevis egg, present at 85.2 nM, an ∼20-fold higher concentration than either PLCβ1 (3.9 nM) or PLCβ3 (4.3 nM). We also looked at an RNA-seq dataset acquired during different stages of development of X. laevis oocytes and eggs (Session et al., 2016). We reasoned that if these three PLC proteins are present in the fertilization-competent eggs, the RNA encoding these enzymes should be present in the developing gamete. Indeed, mRNA for all three PLC types was present in the developing oocytes (Fig. 2). We also observed RNA-encoding isoforms not found in the egg (Fig. 2); this is expected as the unfertilized egg contains all of the RNA translated before the maternal-to-zygotic transition occurs in during X. laevis development when the embryo is ∼4,000 cells (Yang et al., 2015).

Figure 2.

X. laevis eggs contain three PLC subtypes. Heatmaps of RNA (top) and protein (bottom) expression levels of PLC subtypes at varying stages of oocyte and egg development. RNA-seq data displayed as transcripts per million (TPM), and protein data shown as nanomolar concentration. Transcript levels were obtained and compiled from Session et al. (2016), while protein concentrations were from Wühr et al. (2014) through mass spectrometry. Red arrowheads indicate PLC subtypes that are present in both RNA-seq and mass spectrometry datasets in X. laevis eggs.

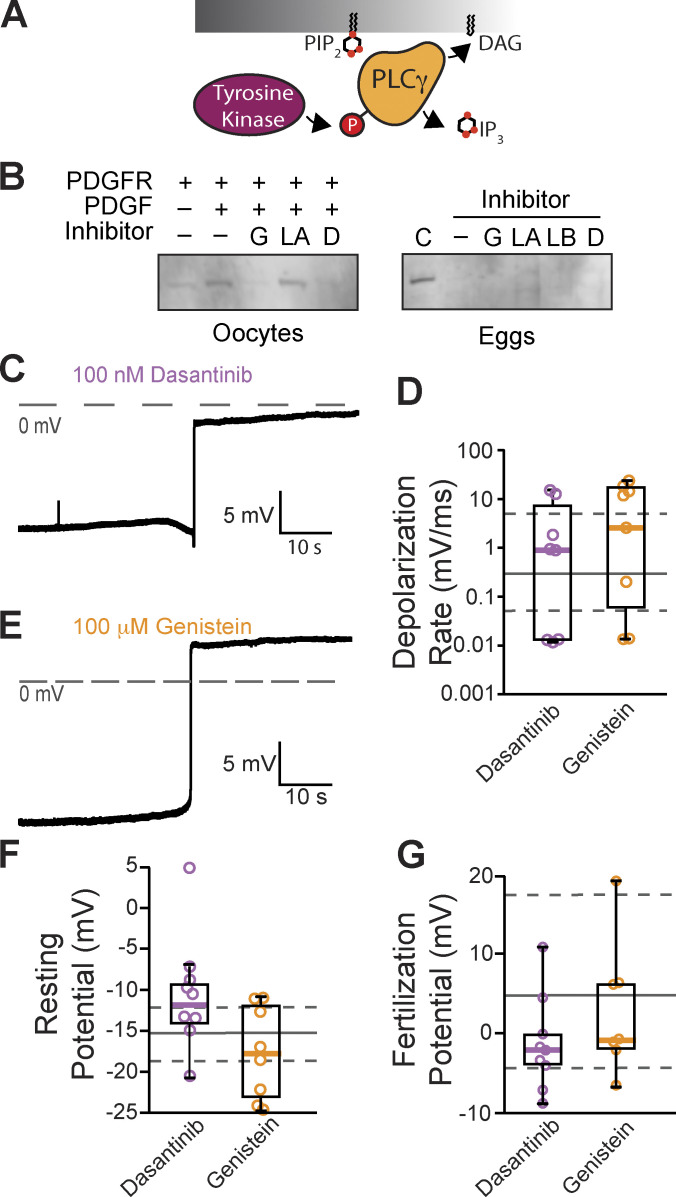

Tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 does not signal the fast block

Typically, PLCγ1 is activated by tyrosine phosphorylation of the critical residue Y776 (homologous to Y783 in mouse PLCγ1) in the SH2 domain of the enzyme (Kadamur and Ross, 2013; Fig. 3 A). Currently, no PLCγ1-specific inhibitors exist, but we can prevent phosphotyrosine-dependent activation of this enzyme using tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Before applying these inhibitors to fertilization, we first screened tyrosine kinase inhibitors for their efficacy in preventing PLCγ1 phosphorylation in X. laevis oocytes exogenously expressing PDGF-R. Applying PDGF to PDGF-R expressing oocytes induced phosphorylation of PLCγ1 at the critical tyrosine at position Y776 (Fig. 3 B). We then applied the tyrosine kinase inhibitors, two of which, genistein (100 µM) and dasantinib (100 nM), effectively stopped PDGF-signaled PLCγ1 phosphorylation. By contrast, lavendustin A (100 nM) was not effective (Fig. 3 B and Fig. S1).

Figure 3.

Inhibiting tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 did not alter the fast block to polyspermy. (A) Tyrosine kinases canonically activate PLCγ through phosphorylation (P). (B) Western blots probing for tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1-Y776 in X. laevis oocytes expressing PDGFR in the presence of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (G: genistein; LA: lavendustin A; D: dasantinib; left) and fertilized X. laevis eggs in the presence of inhibitors along with PDGFR-expressing, PDGF-activated oocyte control (C), and inactive analog (LB: lavendustin B; right). Eggs processed for Western blot revealed that PLCγ1-Y776 was not phosphorylated following fertilization. (C and E) Representative whole-cell recording of X. laevis eggs fertilized in the presence of (C) dasantinib (N = 9) or (E) genistein (N = 8). (D, F, and G) Tukey box plot distributions for depolarization rates (D), resting potential (F), and fertilization potential (G) in dasantinib and genistein. Middle line denotes the median value, the box indicates 25–75%, and the whiskers indicate 10–90%. Gray solid lines indicate median control values while gray dashed lines indicate the 25–75% spread of the controls. Source data are available for this figure: SourceData F3.

To determine whether tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 is required for the fast block, we made whole-cell recordings from X. laevis eggs inseminated in the presence of the validated tyrosine kinase inhibitors, genistein and dasantinib. We did not observe any significant differences between fertilization-evoked depolarizations recorded under control conditions (Fig. 1) or in solutions supplemented with 100 μM genistein or 100 nM dasantinib (Fig. 3, C and E). Like eggs fertilized under control conditions, the mean resting potential of eggs in 100 μM genistein was −17.6 ± 1.9 mV (vs. −15.9 ± 1.0 mV for control, P = 0.92, Tukey honestly significant difference [HSD] test) and the membrane potential following the fertilization-evoked depolarization was 2.4 ± 2.6 mV (vs. 6.5 ± 2.4 mV for controls, P = 0.85, Tukey HSD test; N = 7–27 eggs in three independent trials, Fig. 3, F and G). Genistein also did not alter the depolarization as the average rate was 8.9 ± 3.1 mV/ms compared with 4.4 ± 1.7 mV/ms for depolarizations recorded under control conditions (P = 0.66, Tukey HSD test, Fig. 3 D). Fertilization of eggs recorded in 100 nM dasantinib had a mean resting potential of −10.3 ± 2.2 mV (vs. −15.9 ± 1.0 mV for control, P = 0.19, Tukey HSD test, Fig. 3 F) and membrane potential after the fertilization-evoked depolarization of −1.3 ± 1.9 mV (vs. 6.5 ± 2.4 mV for controls, P = 0.41, Tukey HSD test, Fig. 3 G). The rate of depolarization for these eggs was 3.5 ± 1.9 mV/ms (vs. 4.4 ± 1.7 mV/ms, P = 0.99, Tukey HSD test, Fig. 3 D).

Others have reported that lavendustin A stopped the fast block in X. laevis fertilization (Glahn et al., 1999). Although lavendustin A had little effect on phosphorylation of PLCγ1, we made whole-cell recordings from X. laevis eggs in the presence of 100 nM lavendustin A or its inactive analog lavendustin B. We observed similar resting potentials, −7.9 ± 2.4 mV and −8.1 ± 2.5 mV, and fertilization potentials, 19.7 ± 3.9 mV and 19.8 ± 3.8 mV, in the presence of lavendustin A or B, respectively (Fig. S2). We also recorded normal depolarizations in either compound, 0.7 ± 0.5 mV/ms and 0.3 ± 0.2 mV/ms, which were similar to the lavendustin A and B control rates of 0.3 ± 0.2 mV/ms and 0.03 ± 0.01 mV/ms, respectively. Persistence of normal fertilization-evoked depolarizations of eggs inseminated in lavendustin A or B did not disrupt the fast block to polyspermy in X. laevis eggs.

To determine whether tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 occurs during X. laevis fertilization, we also blotted for Y776 phosphorylation in X. laevis zygotes. X. laevis eggs were incubated for 5 min in either control MR/3 conditions or tyrosine kinase inhibitors prior to sperm addition. 10 min following insemination, we observed contraction of the animal pole, an indicator of fertilization, and fertilized eggs were then dejellied. Following jelly removal, zygotes were lysed and processed for Western blots as described previously. In three independent trials, we observed no evidence of PLCγ1 phosphorylation at Y776 at fertilization (Fig. 3 B). Our results demonstrate that PLCγ1 is not activated by tyrosine phosphorylation during X. laevis fertilization.

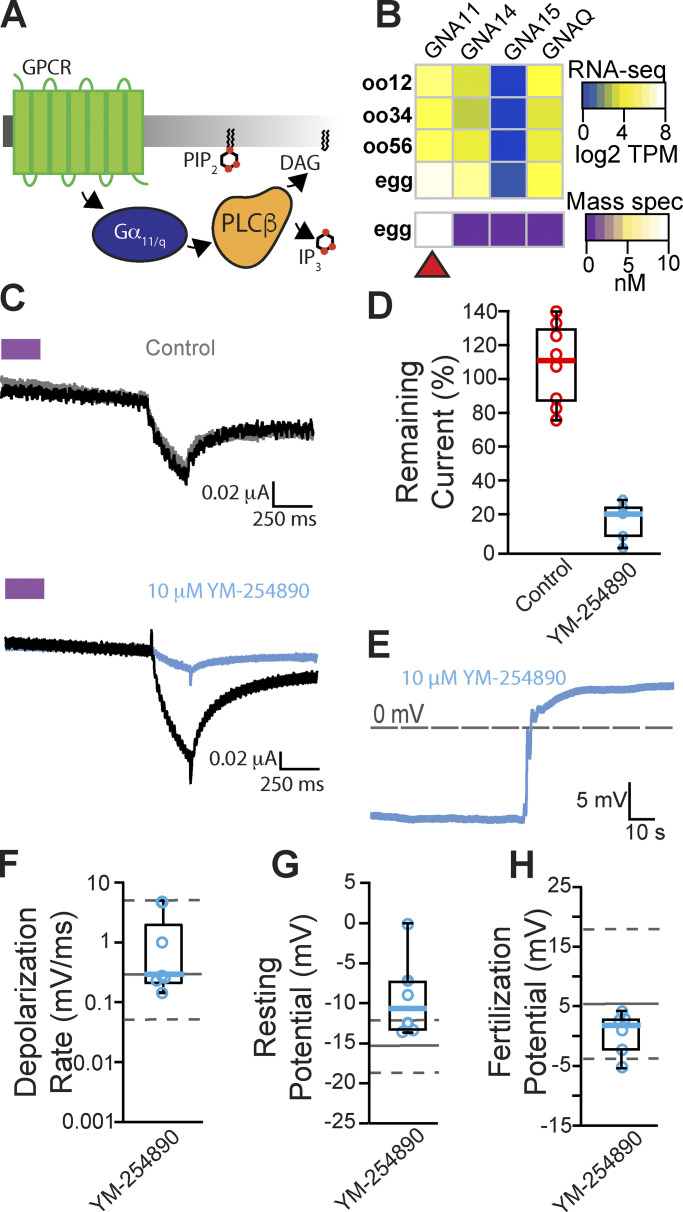

The X. laevis fast block does not require Gα11 activation of PLCβ

We next examined the other PLC isoforms present in the egg and investigated whether activation of PLCβ is required to signal the fast block. Two types of PLCβs are found in X. laevis eggs, PLCβ1 and PLCβ3 (Fig. 2), and these isoforms are typically activated by the α subunit of the Gαq family (Smrcka et al., 1991; Rhee, 2001; Fig. 4 A). The Gαq family is comprised of four members: Gαq, Gα11, Gα14, and Gα15 (Peavy et al., 2005). To determine which Gαq family members are expressed in X. laevis eggs, we again looked at a proteomics dataset for X. laevis eggs (Wühr et al., 2014). Of the four Gαq subtypes (genes: GNA11, GNA14, GNA15, and GNAQ), we found that only GNA11 is present in the unfertilized X. laevis egg (Fig. 4 B). We also validated that, indeed, RNA encoding the Gα11 protein was present in the developing oocyte (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Inhibiting Gα11/q activation of PLCβ did not alter the fast block to polyspermy. (A) PLCβ is canonically activated through the Gα11/q subunit of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR). (B) Heatmap of RNA (top) and protein (bottom) expression for the four Gαq family isoforms in X. laevis oocyte and fertilization-competent eggs. Only Gα11 (encoded by GNA11) was observed in mature eggs. TPM, transcripts per million. (C) Representative consecutive two-electrode voltage clamp recordings in control (top) conditions in oocytes expressing opto-M1R and clamped at and before and after a 10-min incubation in YM-254890, a Gα11/q inhibitor (bottom; N = 5–8). The purple block indicates the time of blue/green light application. (D) Tukey box plot distributions of the percent remaining current in consecutive recordings in control or YM-254890 conditions from oocytes expressing opto-M1R. Middle line indicates median value while the box denotes 25–75% and the whiskers maximum and minimum values. (E) Representative whole-cell recording of X. laevis eggs in the presence of YM-254890 (N = 6). (F–H) Tukey box plot distributions of (F) depolarization rates, (G) resting potential, and (H) fertilization potential in the presence of YM-254890. Middle line indicates median value while the box denotes 25–75% and the whiskers 10–90%. Gray solid lines denote control median, and dashed gray lines indicate 25–75% distribution of the control.

To identify inhibitors that stop Gα11 activation of PLCβ, we made two-electrode voltage clamp recordings from X. laevis oocytes expressing the chimeric light-activated muscarinic opto-M1R (Morri et al., 2018). Blue/green light turns on opto-M1R, which then activates PLCβ via Gαq/11 and induces IP3-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER. This burst of intracellular Ca2+ is sufficient to activate TMEM16A channels at the membrane, and we can monitor this pathway by observing TMEM16A-conducted currents on X. laevis oocytes clamped at −80 mV. We first established that under control conditions, multiple light applications evoked similar amplitudes of TMEM16A-conducted currents (Fig. 4 C, top). We then screened inhibitors of this pathway by comparing TMEM16A-conducted currents before or during application of the known Gαq/11 inhibitors YM-254890 (Fig. 4 C, bottom; Uemura et al., 2006) and BIM-46187 (Schmitz et al., 2014). Following an initial light application, opto-M1R–expressing oocytes were incubated for 10 min in the presence of either inhibitor before a second application of light. We found that YM-254890 significantly reduced activation of TMEM16A channels by opto-M1R, reducing the remaining current following second light application from an average of 108 ± 10% remaining current under control conditions to 16 ± 5% remaining current in 10 μM YM-254890 (Fig. 4 D). By contrast, BIM-46187 did not alter opto-M1R activation of TMEM16A-conducted current, with 103 ± 17% remaining current in 25 μM BIM-46187 (Fig. S3). These data indicate that YM-254890 effectively stops Gαq/11 activation of PLCβ.

To test whether Gα11 activates PLCβ during the fast block, we performed whole-cell recordings on X. laevis eggs in the presence of 10 μM YM-254890 following a 10-min incubation. In six independent trials, we observed normal fertilization-evoked depolarizations in the presence of 10 μM YM-254890 (Fig. 4 E). The average membrane potentials from eggs inseminated in 10 μM YM-254890 was −9.3 ± 1.9 mV before (vs. −15.9 ± 1.0 mV from recordings, P = 0.9, Tukey HSD) and 0.5 ± 1.3 mV (vs. 4.4 ± 1.7 mV/ms, P = 0.62, Tukey HSD) after fertilization evoked depolarization (Fig. 4, G and H). The depolarization rates were also similar in the presence or absence of YM-254890, with an average 1.1 ± 0.7 mV/ms with the inhibitor compared with 4.4 ± 1.7 mV/ms without (P = 0.83, Tukey HSD, Fig. 4 F). These findings reveal that fertilization does not require Gα11-coupled activation of PLCβ.

Discussion

The fast block to polyspermy is one of the earliest processes used by external fertilizers to ensure the genetic integrity of the nascent zygote. Although this process is used by the diverse assortment of animals that fertilize outside of the mother, the signaling events involved in this process have largely remained elusive. Our data demonstrate that the fast block is mediated by activation of a PLC (Fig. 1). Specifically, we have found that in the presence of the general PLC inhibitor U73122, fertilization did not trigger depolarization of X. laevis eggs and that these eggs developed asymmetric cleavage furrows (Fig. 1 F), an indicator of polyspermy. By contrast, we have previously reported that the inactive analog, U73343, did not alter the fast block (Wozniak et al., 2018b). We have also previously reported that the fast block in X. laevis eggs requires an activation of the ER-localized IP3R (Wozniak et al., 2018b), which enables Ca2+ release and opening of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channel TMEM16A (Wozniak et al., 2018a). Cl− then leaves the egg to depolarize the plasma membrane (Cross and Elinson, 1980; Grey et al., 1982; Webb and Nuccitelli, 1985). Here, we sought to uncover how fertilization initiates the fast block in X. laevis eggs by examining how fertilization activates PLC.

We used proteomic (Wühr et al., 2014) and transcriptomic (Session et al., 2016) data on PLC isoforms present in the X. laevis eggs to provide clues about how they are activated by fertilization. Interrogating these datasets, we identified three PLC isoforms in X. laevis eggs: PLCγ1, PLCβ1, and PLCβ3. Notably, PLCγ1 is ∼20-fold more abundant than either PLCβ1 or PLCβ3 (Fig. 2). PLC subfamilies are distinguished by structural features that serve as regulatory elements for cell signaling pathways. However, the catalytic component of PLC enzymes is highly conserved between members of the distinct PLC subfamilies (Gresset et al., 2012). Consequently, there are no inhibitors specific to each PLC subtype. However, selective inhibition can be accomplished upstream of PLC activation (e.g., the kinase and G-protein coupled receptor–coupled mechanisms that activate PLCγ and PLCβ, respectively).

The PLCγ enzyme is typically activated by phosphorylation of a critical tyrosine residue near its catalytic domain (Gresset et al., 2012). We validated that the tyrosine kinase inhibitors genistein and dasantanib blocked PLCγ1 phosphorylation by the receptor tyrosine kinase PDGF-R, but found that neither had any effect on the fast block (Fig. 3, B and D). These data indicate that tyrosine kinase–induced activation of PLCγ1 does not mediate the fast block in X. laevis.

Intriguingly, our data disagree with the prevailing hypothesis that fertilization in X. laevis activates PLCγ1 via tyrosine phosphorylation (Mahbub Hasan et al., 2005). In this hypothesis, an Src family kinase tyrosine phosphorylates PLCγ to thereby activate increased intracellular Ca2+ that initiates the cortical granule exocytosis of the slow block to polyspermy (Sato et al., 2000). Although it is yet to be determined whether the same signaling pathway initiates both the fast and slow block, our data suggest that fertilization does not activate PLCγ1 via tyrosine phosphorylation of Y776 (Fig. 3 B). We suspect that differences in the methods used to monitor tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ1 following fertilization underlie the differences in these data.

We also considered a possible role for a G-protein–mediated signaling pathway in the X. laevis fast block. Typically, PLCβ isoforms are activated by G-protein pathways requiring members of the Gαq/11 family. We noted that X. laevis eggs express the Gα11 subunit, supporting this possibility. By activating Gαq/11 through the light-activated receptor opto-M1R (Morri et al., 2018), we were able to reproducibly induce TMEM16A currents and furthermore inhibit this effect by application of the Gαq/11 inhibitor YM-254890. However, application of 10 μM YM-254890 had no effect on the fast block to polyspermy in X. laevis eggs (Fig. 4 B).

In addition to Gαq/11, PLCβ subtypes can be activated by the Gβγ dimers derived from Gαi signaling pathways (Boyer et al., 1992). Generally, Gαi is the most abundant α subunit isoform that is ubiquitously expressed in all cells, and consequently the most prolific source of Gβγ signaling (Hepler and Gilman, 1992; Touhara and MacKinnon, 2018). Even though all G-protein heterotrimers contain β and γ subunits, initiation of Gβγ signaling downstream of G-protein coupled receptors is typically the result of Gαi coupled receptors, likely due to the relatively low affinity of Gβγ for its effectors relative to interactions of Gα subunits and increased cellular abundance of Gαi heterotrimers (Hepler and Gilman, 1992). Indeed, X. laevis eggs express three Gαi isoforms abundantly (Fig. S4). However, we did not pursue a role for Gαi because published data suggest that this pathway did not contribute to the fast block (Kline et al., 1991). Specifically, Kline and colleagues demonstrated that stopping Gαi signaling with pertussis toxin did not alter the fertilization-signaled depolarization in X. laevis eggs (Kline et al., 1991).

Our data agree with interpretations of results published by Runft and colleagues, who loaded X. laevis eggs with calcium green dextran to observe the fertilization signaled Ca2+ wave (Runft et al., 1999). They reported that stopping PLCγ1 activation by expressing a dominant negative SH2 domain did not alter the fertilization-activated Ca2+ wave in X. laevis eggs (Runft et al., 1999). The SH2 domain includes the Y783 residue within the enzyme’s active site that mediates activation via phosphorylation (Hajicek et al., 2019). We did not observe evidence that this residue is phosphorylated, leaving the possibility that overexpression of the SH2 domain does not interfere with a phosphorylation-independent mechanism for PLCγ1 activation. Runft and colleagues also reported that injection of a Gαq targeting antibody did not disrupt the fertilization signaled Ca2+ wave. X. laevis eggs don’t express the Gαq protein, but antibody injection was sufficient to disrupt PLCβ-mediated Ca2+ via an exogenously expressed serotonin receptor, suggesting that their antibody was capable of inhibiting the native Gαq/11 protein (Runft et al., 1999).

Our data support the hypothesis that a non-canonical pathway activates a PLC to signal the fast block in X. laevis eggs. A possible mechanism for this is that elevated cytoplasmic Ca2+ alone may signal PLC activation at fertilization. Elevated Ca2+ has been shown to activate several PLC isoforms, including PLCγ1 (Wahl et al., 1992; Hwang et al., 1996) and PLCβ (Ryu et al., 1987; Wahl et al., 1992; Hwang et al., 1996). Several groups have proposed that this mechanism underlies the regenerative Ca2+ wave that enables cortical granule exocytosis for the slow polyspermy block (Fall et al., 2004; Wagner et al., 2004).

Alternatively, a sperm-donated PLC could give rise to the fast block. In mammalian fertilization, the sperm-derived, soluble PLCζ (encoded by the PLCZ1 gene) is released as a consequence of sperm entry. Released PLCζ signals the Ca2+ wave and initiates the slow polyspermy block (Nozawa et al., 2018). However, the PLCZ1 gene has not yet been annotated in non-mammalian animals. Whether a different sperm-derived PLC activates eggs is yet to be determined.

Fertilization quickly activates a PLC to signal TMEM16A activation and the fast block to polyspermy in X. laevis. Several questions remain regarding this critical process. Answering these questions will not only reveal the earliest events of new life but will also shed light on the voltage dependence of fertilization.

Supplementary Material

is the source file for Fig. 3.

Acknowledgments

Joseph A. Mindell served as editor.

We thank D. Summerville and P. Sau for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Institute for Health grants 1R01GM125638 to A.E. Carlson and T32GM133353 to K.M. Komondor.

Author contributions: K.M. Komondor, R.E. Bainbridge, J.C. Rosenbaum, and A.E. Carlson conceived of the research. K.M. Komondor, R.E. Bainbridge, and A.E. Carlson wrote the manuscript and assembled the figures. K.M. Komondor, R.E. Bainbridge, K.G. Sharp, A.R. Iyer, J.C. Rosenbaum, and A.E. Carlson conducted the experimentation, performed the analysis, and edited the manuscript. A.E. Carlson acquired funding.

Data availability

Data are available in the article itself and in the supplementary materials.

References

- Bianchi, E., and Wright G.J.. 2016. Sperm meets egg: The genetics of mammalian fertilization. Annu. Rev. Genet. 50:93–111. 10.1146/annurev-genet-121415-121834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, J.L., Waldo G.L., and Harden T.K.. 1992. βγ-subunit activation of G-protein-regulated phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 267:25451–25456. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)74062-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N.L., and Elinson R.P.. 1980. A fast block to polyspermy in frogs mediated by changes in the membrane potential. Dev. Biol. 75:187–198. 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90154-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinson, R.P. 1975. Site of sperm entry and a cortical contraction associated with egg activation in the frog Rana pipiens. Dev. Biol. 47:257–268. 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90281-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.P. 2020. Preventing polyspermy in mammalian eggs-Contributions of the membrane block and other mechanisms. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 87:341–349. 10.1002/mrd.23331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkamp, E., Algarra B., and Jovine L.. 2020. Mammalian egg coat modifications and the block to polyspermy. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 87:326–340. 10.1002/mrd.23320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fall, C.P., Wagner J.M., Loew L.M., and Nuccitelli R.. 2004. Cortically restricted production of IP3 leads to propagation of the fertilization Ca2+ wave along the cell surface in a model of the Xenopus egg. J. Theor. Biol. 231:487–496. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanilla, R.A., and Nuccitelli R.. 1998. Characterization of the sperm-induced calcium wave in Xenopus eggs using confocal microscopy. Biophys. J. 75:2079–2087. 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77650-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagoski, D., Polinkovsky M.E., Mureev S., Kunert A., Johnston W., Gambin Y., and Alexandrov K.. 2016. Performance benchmarking of four cell-free protein expression systems. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 113:292–300. 10.1002/bit.25814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn, D., Mark S.D., Behr R.K., and Nuccitelli R.. 1999. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors block sperm-induced egg activation in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 205:171–180. 10.1006/dbio.1998.9042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresset, A., Sondek J., and Harden T.K.. 2012. The phospholipase C isozymes and their regulation. Subcell. Biochem. 58:61–94. 10.1007/978-94-007-3012-0_3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey, R.D., Bastiani M.J., Webb D.J., and Schertel E.R.. 1982. An electrical block is required to prevent polyspermy in eggs fertilized by natural mating of Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 89:475–484. 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90335-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajicek, N., Keith N.C., Siraliev-Perez E., Temple B.R., Huang W., Zhang Q., Harden T.K., and Sondek J.. 2019. Structural basis for the activation of PLC-γ isozymes by phosphorylation and cancer-associated mutations. Elife. 8:e51700. 10.7554/eLife.51700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold, T., Chen N., Funkhouser J., Jooss T., Manuel B., Matsuura J., Matsuyama A., Wilson C., Yamane J.A., and Jacobs P.A.. 1980. A cytogenetic study of 1000 spontaneous abortions. Ann. Hum. Genet. 44:151–178. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1980.tb00955.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman, J., Holwill S., and Wylie C.C.. 1991. Fertilization of cultured Xenopus oocytes and use in studies of maternally inherited molecules. Methods Cell Biol. 36:213–230. 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60279-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler, J.R., and Gilman A.G.. 1992. G proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 17:383–387. 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90005-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, W.G., Southern N.M., MacIver B., Potter E., Apodaca G., Smith C.P., and Zeidel M.L.. 2005. Isolation and characterization of the Xenopus oocyte plasma membrane: A new method for studying activity of water and solute transporters. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 289:F217–F224. 10.1152/ajprenal.00022.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.C., Jhon D.Y., Bae Y.S., Kim J.H., and Rhee S.G.. 1996. Activation of phospholipase C-γ by the concerted action of tau proteins and arachidonic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 271:18342–18349. 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, L.A. 1976. Fast block to polyspermy in sea urchin eggs is electrically mediated. Nature. 261:68–71. 10.1038/261068a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, L.A., and Gould M.. 1985. Polyspermy-preventing mechanisms. In Biology of Fertilization. Metz C.B. and Monroy A., editors. Academic Press, New York. 223–250. 10.1016/B978-0-12-492603-5.50012-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadamur, G., and Ross E.M.. 2013. Mammalian phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 75:127–154. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, D., Kopf G.S., Muncy L.F., and Jaffe L.A.. 1991. Evidence for the involvement of a pertussis toxin-insensitive G-protein in egg activation of the frog, Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 143:218–229. 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90072-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahbub Hasan, A.K., Sato K., Sakakibara K., Ou Z., Iwasaki T., Ueda Y., and Fukami Y.. 2005. Uroplakin III, a novel Src substrate in Xenopus egg rafts, is a target for sperm protease essential for fertilization. Dev. Biol. 286:483–492. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morri, M., Sanchez-Romero I., Tichy A.M., Kainrath S., Gerrard E.J., Hirschfeld P.P., Schwarz J., and Janovjak H.. 2018. Optical functionalization of human class A orphan G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Commun. 9:1950. 10.1038/s41467-018-04342-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa, K., Satouh Y., Fujimoto T., Oji A., and Ikawa M.. 2018. Sperm-borne phospholipase C zeta-1 ensures monospermic fertilization in mice. Sci. Rep. 8:1315. 10.1038/s41598-018-19497-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuccitelli, R., Yim D.L., and Smart T.. 1993. The sperm-induced Ca2+ wave following fertilization of the Xenopus egg requires the production of Ins(1,4,5)P3. Dev. Biol. 158:200–212. 10.1006/dbio.1993.1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peavy, R.D., Hubbard K.B., Lau A., Fields R.B., Xu K., Lee C.J., Lee T.T., Gernert K., Murphy T.J., and Hepler J.R.. 2005. Differential effects of Gqα, G14α, and G15α on vascular smooth muscle cell survival and gene expression profiles. Mol. Pharmacol. 67:2102–2114. 10.1124/mol.104.007799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, S.G. 2001. Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:281–312. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, J., Hinostroza F., Vergara S., Pinto-Borguero I., Aguilera F., Fuentes R., and Carvacho I.. 2021. Knockin’ on egg’s door: Maternal control of egg activation that influences cortical granule exocytosis in animal species. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9:704867. 10.3389/fcell.2021.704867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runft, L.L., Watras J., and Jaffe L.A.. 1999. Calcium release at fertilization of Xenopus eggs requires type I IP3 receptors, but not SH2 domain-mediated activation of PLCγ or Gq-mediated activation of PLCβ. Dev. Biol. 214:399–411. 10.1006/dbio.1999.9415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, S.H., Suh P.G., Cho K.S., Lee K.Y., and Rhee S.G.. 1987. Bovine brain cytosol contains three immunologically distinct forms of inositolphospholipid-specific phospholipase C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:6649–6653. 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, K., Tokmakov A.A., Iwasaki T., and Fukami Y.. 2000. Tyrosine kinase-dependent activation of phospholipase Cγ is required for calcium transient in Xenopus egg fertilization. Dev. Biol. 224:453–469. 10.1006/dbio.2000.9782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, A.L., Schrage R., Gaffal E., Charpentier T.H., Wiest J., Hiltensperger G., Morschel J., Hennen S., Häußler D., Horn V., et al. 2014. A cell-permeable inhibitor to trap Gαq proteins in the empty pocket conformation. Chem. Biol. 21:890–902. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Session, A.M., Uno Y., Kwon T., Chapman J.A., Toyoda A., Takahashi S., Fukui A., Hikosaka A., Suzuki A., Kondo M., et al. 2016. Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature. 538:336–343. 10.1038/nature19840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smrcka, A.V., Hepler J.R., Brown K.O., and Sternweis P.C.. 1991. Regulation of polyphosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C activity by purified Gq. Science. 251:804–807. 10.1126/science.1846707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tembo, M., Wozniak K.L., Bainbridge R.E., and Carlson A.E.. 2019. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and Ca2+ are both required to open the Cl− channel TMEM16A. J. Biol. Chem. 294:12556–12564. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.007128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tembo, M., Sauer M., Wisner B., Beleny D., Napolitano M., and Carlson A.. 2021. Actin polymerization is not required for the fast block to polyspermy in the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis. MicroPubl. Biol. 10.17912/micropub.biology.000365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touhara, K.K., and MacKinnon R.. 2018. Molecular basis of signaling specificity between GIRK channels and GPCRs. Elife. 7:e42908. 10.7554/eLife.42908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura, T., Kawasaki T., Taniguchi M., Moritani Y., Hayashi K., Saito T., Takasaki J., Uchida W., and Miyata K.. 2006. Biological properties of a specific Gαq/11 inhibitor, YM-254890, on platelet functions and thrombus formation under high-shear stress. Br. J. Pharmacol. 148:61–69. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, J., Fall C.P., Hong F., Sims C.E., Allbritton N.L., Fontanilla R.A., Moraru I.I., Loew L.M., and Nuccitelli R.. 2004. A wave of IP3 production accompanies the fertilization Ca2+ wave in the egg of the frog, Xenopus laevis: Theoretical and experimental support. Cell Calcium. 35:433–447. 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, M.I., Jones G.A., Nishibe S., Rhee S.G., and Carpenter G.. 1992. Growth factor stimulation of phospholipase C-γ1 activity. Comparative properties of control and activated enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 267:10447–10456. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50039-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, D.J., and Nuccitelli R.. 1985. Fertilization potential and electrical properties of the Xenopus laevis egg. Dev. Biol. 107:395–406. 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90321-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.L., and Wessel G.M.. 2006. Defending the zygote: Search for the ancestral animal block to polyspermy. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 72:1–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak, K.L., Bainbridge R.E., Summerville D.W., Tembo M., Phelps W.A., Sauer M.L., Wisner B.W., Czekalski M.E., Pasumarthy S., Hanson M.L., et al. 2020. Zinc protection of fertilized eggs is an ancient feature of sexual reproduction in animals. PLoS Biol. 18:e3000811. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak, K.L., and Carlson A.E.. 2020. Ion channels and signaling pathways used in the fast polyspermy block. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 87:350–357. 10.1002/mrd.23168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak, K.L., Mayfield B.L., Duray A.M., Tembo M., Beleny D.O., Napolitano M.A., Sauer M.L., Wisner B.W., and Carlson A.E.. 2017. Extracellular Ca2+ is required for fertilization in the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis. PLoS One. 12. e0170405. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak, K.L., Phelps W.A., Tembo M., Lee M.T., and Carlson A.E.. 2018a. The TMEM16A channel mediates the fast polyspermy block in Xenopus laevis. J. Gen. Physiol. 150:1249–1259. 10.1085/jgp.201812071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak, K.L., Tembo M., Phelps W.A., Lee M.T., and Carlson A.E.. 2018b. PLC and IP3-evoked Ca2+ release initiate the fast block to polyspermy in Xenopus laevis eggs. J. Gen. Physiol. 150:1239–1248. 10.1085/jgp.201812069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wühr, M., R.M. Freeman, Jr., Presler M., Horb M.E., Peshkin L., Gygi S., and Kirschner M.W.. 2014. Deep proteomics of the Xenopus laevis egg using an mRNA-derived reference database. Curr. Biol. 24:1467–1475. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., Aguero T., and King M.L.. 2015. The Xenopus maternal-to-zygotic transition from the perspective of the germline. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 113:271–303. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

is the source file for Fig. 3.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in the article itself and in the supplementary materials.