Abstract

A number of antibodies generated during human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection have been cloned by the phage library approach. Antibodies reactive with an immunodominant epitope on the F glycoprotein of this virus have a high affinity for affinity-purified F antigen. These antibodies, however, have a much lower affinity for mature F glycoprotein on the surface of infected cells and are nonneutralizing. In contrast, a potent neutralizing antibody has a high affinity for mature F protein but a much lower affinity for purified F protein or F protein in viral lysates. The data indicate that at least two F protein immunogens are produced during natural RSV infection: immature F, found in viral lysates, and mature F, found on infected cells or virions. Binding studies with polyclonal human immunoglobulin G suggest that the antibody responses to the two immunogens are of similar magnitudes. Competitive binding studies suggest that overlap between the responses is relatively limited. A mature envelope with an antigenic configuration different from that of the immature envelope has an evolutionary advantage in that the infecting virus is less subject to neutralization by the humoral response to the immature envelope that inevitably arises following lysis of infected cells. Subunit vaccines may be at a disadvantage because they most often resemble immature envelope molecules and ignore this aspect of viral evasion.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) remains the most important cause of serious viral respiratory illness in infants and young children. Although previous contact with the virus provides partial immune protection from subsequent reinfections, the development of an effective vaccine has proven extremely difficult (17). Recently, promising attenuated live virus vaccine candidates have been identified during studies with experimental primates and phase I clinical trials (16, 22, 25). These vaccine candidates must strike a fine balance between attenuation and immunogenicity and be suitable for use in both seronegative children over 6 months of age and very young infants with maternally derived RSV-specific antibodies (15, 16). Subunit vaccine preparations, while not as immunogenic as live virus, are currently being evaluated as a means of boosting the immunity of elderly populations (18) and children suffering from cystic fibrosis (31). However, because of the association between vaccination with nonreplicating virus antigens and enhancement of clinical disease, subunit formulations are not suitable for young seronegative infants (26).

An important factor in the assessment of virus vaccine candidates is their ability to elicit neutralizing antibodies. This is especially true for viruses such as RSV, since neutralizing antibodies have been shown to play a major role in resistance to disease in humans (28) as well as in protection from infection in experimental animals (14, 33–35, 39, 40). Both RSV infection and RSV vaccines elicit neutralizing and nonneutralizing antibodies reactive with envelope glycoproteins. It is unclear what distinguishes these classes of antibodies and how they are elicited in humans. Both issues are important for vaccine design.

We have approached these issues by cloning a set of human antibodies elicited to the RSV envelope by natural infection. Analysis of human antibody responses has been greatly hindered in the past by the difficulties of obtaining human monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) representative of these responses. Phage library technology provides a possible strategy for solving this problem. The technique does involve random recombination of antibody heavy and light chains, which was initially thought to exclude the study of antibody responses; however, detailed investigations of a number of antibody responses to pathogens and autoantigens by the library approach have suggested that, notwithstanding this limitation, the cloned antibodies reflect broad aspects of natural responses (1, 7, 9, 19, 32, 41). In particular, epitope specificities found in the polyclonal serum are usually rescued in the corresponding library. The reasons are not fully understood but likely include some reforming of in vivo heavy- light chain combinations and domination of the binding specificity by one chain so that the partner is less important.

In this report, we have examined human antibody responses, both neutralizing and nonneutralizing, in RSV infection by using the library approach. We have restricted our analysis to human antibodies that develop against the F glycoprotein of the virus during the course of natural infection. The F glycoprotein is well defined as a major antigenic target of RSV-neutralizing antibodies. However, several lines of evidence suggest that the epitopes eliciting this protective response are conformational and highly sensitive to perturbations of the tertiary structure of the protein. For example, earlier vaccine trials with formalin-inactivated virus or affinity-purified F protein induced an imbalanced, predominantly nonneutralizing antibody response (27, 31). Moreover, many attempts to elicit a protective antibody response by immunizing animals with large synthetic peptides containing a portion of the F glycoprotein sequence failed, presumably because conformational determinants present in the native protein were not faithfully reproduced in the peptides (5, 23, 36).

These observations should be interpreted in light of the cellular processing of the F protein and its assembly into virion spikes. First produced as an inactive glycosylated precursor, F0, the protein is subsequently modified by the addition of N-linked carbohydrate and then assembled into homo-oligomers in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. F0 is subsequently cleaved endoproteolytically in the Golgi apparatus, yielding two subunits (F1 and F2) that are covalently linked to each other by disulfide bonds. It is believed that four F1—F2 molecules interact via the F1 subunit to produce the viral envelope tetramer spike. Thus, the F glycoprotein is present during infection in a number of immature forms as well as the mature form found on virions and the surface of infected cells. Any or all of these forms may stimulate the humoral immune system. It should also be noted that the mature form of the F glycoprotein, once assembled, could be dissociated to generate further forms of the protein; for the sake of simplicity, these are included here under the general grouping of immature forms of F.

In this study, we report that a number of human MAbs representing major anti-F protein specificities react strongly with immature forms of the F glycoprotein but only very weakly with the mature form expressed on RSV-infected cells. These antibodies are nonneutralizing and were presumably elicited by immature forms of the F glycoprotein. In contrast, one human MAb reacts almost exclusively with the mature form of the F glycoprotein on RSV-infected cells and virions and essentially not at all with the immature forms. It is potently neutralizing and was presumably elicited by the mature envelope on virions or infected cells. We suggest that this envelope glycoprotein dichotomy may be an important strategy for evading host immunity, since infection tends to produce, through lysis of infected cells, relatively large amounts of the immature envelope, which will elicit a strong humoral response (29, 30). A conformationally altered mature envelope molecule on the virus will be less susceptible to this antibody response. An important corollary of this hypothesis is that when recombinant or affinity-purified envelope molecules bear a closer structural similarity to the immature than to the mature envelope, as is often the case, these molecules may not be particularly good vaccines. In other words, this vaccine strategy may be handicapped because viruses have already evolved a mechanism for avoiding the humoral response to immunodominant epitopes presented on immature envelope molecules.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibody reagents. (i) Phage library construction, phage selection, and purification of soluble recombinant Fab fragments.

Four antibody Fab (κ chain of immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]) libraries expressed on the surface of filamentous phage were prepared from bone marrow RNA of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-seropositive donors previously infected with RSV as described elsewhere (8). Phage bearing RSV-specific Fab fragments were selected from the libraries by a panning procedure (8) with recombinant FG protein (kindly provided by M. Wathen, Upjohn) or affinity-purified F protein (kindly supplied by E. Walsh) bound to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) wells. Phage taken from the fourth or fifth panning round were converted to a soluble Fab expression system, and the clones were analyzed for RSV reactivity in an ELISA (41). The light-chain and heavy-chain variable-region sequences of RSV-reactive antibody clones were determined by dideoxy sequencing as described elsewhere (41). Selected clones were grown and purified by use of a polyclonal goat anti-human IgG Fab fragment (Pierce) bound to a protein G matrix (Pharmacia).

(ii) Polyclonal antibodies.

Serum samples were obtained from two healthy volunteers and pooled and from an HIV-1-seropositive donor. Polyclonal IgG was purified from the sera by use of a protein A matrix (Pharmacia).

Characterization of RSV-specific antibodies.

Purified recombinant Fab fragments and polyclonal IgG were measured for their ability to bind to RSV antigens by ELISA, surface plasmon resonance, and flow cytometry analyses.

(i) Surface plasmon resonance.

The kinetic constants for the binding of recombinant Fab fragments to affinity-purified F protein were determined by use of a BIAcore instrument (Pharmacia). F protein was coupled to the (carboxymethyl)dextran matrix of a CM5 sensor chip (Biosensor) by use of N-hydroxysuccinimide and N-ethyl-N′-[(dimethylamino)propyl]-carbodiimide hydrochloride (20). Following coupling, unreacted N-hydroxysuccinimide ester groups were inactivated with 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.0). Typically, 10,000 resonance units were immobilized. Binding measurements were performed with binding buffer (Pharmacia). The association rate constant (kon) of each Fab fragment was measured over a range of concentrations (62 to 1,000 nM) at a flow rate of 10 μl/min. The dissociation rate constant (koff) was determined by increasing the flow rate to 50 μl/min after the association phase. The binding surface was regenerated after each measurement with 10 mM HCl–1 mM NaCl (pH 2.0). Values for kon and koff were calculated by use of BIAcore kinetics evaluation software. The equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) were determined from the rate constants by use of average kon and koff values obtained from four independent measurements.

(ii) Flow cytometry.

Antibody reactivity with F protein on the surface of RSV-infected cells was examined by flow cytometry. Monolayers of HEp-2 or Vero cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 3. At 24 h postinfection, the cells (2 × 106 per sample) were detached from the culture flasks by incubation with 5 mM EDTA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed twice in PBS, and resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS containing 1% fetal calf serum and 0.02% azide). The resuspended cells were incubated for 30 min on ice with 100 μl of a range of concentrations of recombinant Fab fragments (0.04 to 10 μg/ml) or polyclonal IgG (7.8 to 250 μg/ml) and then washed three times in FACS buffer. Cell surface-bound antibody was detected by incubation for 30 min on ice with a 1:100 dilution of goat anti-human IgG Fab fragment–fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The cells were washed three times in PBS, resuspended in 1 ml of PBS, and analyzed by use of a FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

The extent to which affinity-purified F protein is able to inhibit the binding of RSV antibodies in immune human serum to RSV-infected cells was determined by flow cytometry. HEp-2 or Vero cell monolayers were infected with virus and harvested 24 h postinfection as described above. F protein (0.1 nM to 1 μM) was incubated for 1 h at 37°C with serum IgG at 66 μg/ml (a concentration sufficient to yield 50% maximum binding). These mixtures were incubated with infected cells as described above, and the level of bound antibody was determined by use of a FACScan. Inhibition was expressed as a percentage of the mean fluorescence (MF) signal measured in the absence of competing affinity-purified F protein.

The ability of Fab fragment RSV19 to inhibit the binding of RSV antibodies in human serum to RSV-infected cells was determined. HEp-2 cells were harvested 24 h postinfection and incubated for 1 h at 4°C with RSV19 (0.02 to 20 μg/ml). Serum IgG at 66 μg/ml was then added, and the cells were incubated for a further 30 min. Bound IgG was detected by use of a FACScan with a labeled secondary antibody specific for the human IgG Fc fragment. Inhibition was expressed as a percentage of the MF signal measured in the absence of RSV19.

(iii) Competitive ELISA.

To determine if the recombinant antibodies were able to compete with each other for binding to affinity-purified F protein, one Fab fragment (CM68) was biotinylated with a biotin labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. ELISA wells were coated with 100 ng of F protein, which was then reacted with 10 μg of unlabeled Fab fragment per ml for 1 h at 37°C. Biotin-labeled CM68 was added to a final concentration of 1 μg/ml, and the mixture was incubated for an additional 15 min at 37°C before being washed 10 times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. Antigen-bound CM68 was detected by use of goat anti-biotin–alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Sigma). Binding titers were expressed as a percentage of the signal given by biotinylated CM68 in the absence of competing nonbiotinylated Fab fragment, i.e., {100 − [experimental optical density at 490 nm/control optical density at 405 nm (in the absence of competing Fab fragment)]} × 100.

To define the antigenic site on RSV F glycoprotein against which the Fab fragments were directed, binding competition experiments were carried out with Fab fragments and mouse MAbs purified from ascitic fluid by use of a protein A/G matrix (Pierce) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Affinity-purified F protein was used to coat ELISA wells and was reacted for 1 h at 37°C with saturating amounts (20 μg/ml) of purified mouse MAbs that neutralize RSV and recognize the A (MAbs 151 and 1129), AB (MAb 1107), B (MAbs 1112 and 1269), and C (MAb 1243) antigenic sites of the F protein (3). Biotinylated CM68 was added at 1 μg/ml, and the mixture was incubated for a further 15 min at 37°C. Bound CM68 was detected with goat anti-biotin–alkaline phosphatase conjugate. Percent inhibition was calculated as described above.

To determine what proportion of total serum IgG reactivity elicited against the F protein was directed to the epitopes recognized by the recombinant Fab fragments, competition ELISAs were performed with Fab fragments and serum IgG. ELISA wells were coated with F protein, which was then incubated with recombinant Fab fragments (10 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Serum IgG was added at 60 μg/ml (a level predetermined to produce approximately 70% maximum binding to F protein in the ELISA), and the mixture was incubated for an additional 15 min at 37°C. Antigen-bound IgG was detected with goat anti-human IgG (Fc fragment specific) conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Percent inhibition was calculated as described above.

Viruses and cell culture.

HEp-2 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and 5% fetal calf serum. Vero cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum. RSV strains A2 and Long were used to infect HEp-2 cells. RSV strain cp-52, a cold-passage mutant of a subgroup B virus that lacks the G and SH glycoproteins (21) (kindly provided by B. Murphy and S. Whitehead), was used to infect Vero cells. Virus titers were determined by a plaque assay as described elsewhere (10).

Plaque reduction assay.

Antibody neutralization activity was measured by a plaque reduction assay in the absence of complement with HEp-2 cell cultures and strain A2 (subgroup A virus) (10). The neutralizing antibody titer was calculated as the highest dilution of purified Fab fragment or IgG that reduced plaque numbers by 50%.

RESULTS

Recovery of RSV-specific recombinant Fab fragments and assay of their neutralizing activity.

Three IgG1κ antibody Fab libraries, prepared from bone marrow RNA of HIV-1-positive donors possessing high levels of serum antibody neutralizing activities, were displayed on the surface of filamentous phage. The libraries were selected against affinity-purified F protein bound to ELISA wells. Antibody clones taken from the final round of panning were screened in an ELISA for reactivity with F protein. DNA sequence analysis of the antigen-reactive clones identified five novel RSV F protein-specific recombinant Fab fragments (CM2, CM6, CM68, DM2, and DM1) with distinct sequences (Table 1). An additional antibody, Fab fragment RSV19, was generated by panning one of the libraries against recombinant FG glycoprotein, a baculovirus-expressed chimera of the F and G glycoproteins. RSV19, described previously, exhibits high neutralizing activity against a wide range of virus strains in vitro (2, 14). In contrast, none of the antibodies recovered in panning experiments with affinity-purified F protein were able to neutralize RSV in a plaque reduction assay at concentrations of up to 50 μg/ml (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Heavy-chain-complementarity-determining region 3 sequences of RSV-specific Fab fragments

| Fab fragment | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| RSV19 | YYCATAPIAPPYFDHWGQGTLTVSS |

| CM2 | YYCARAGLYNSNGYYLYYFDYWGQGTLVTVTS |

| CM6 | YYCARQSKYASSGYYYTWFDPWGQGTLVTVSS |

| CM68 | YYCARDHGYDGNANYHDYSDYWGQGTLVTVSS |

| DM1 | YYCARELGVSGNGDYIAVFDIWGQGTLVTVSS |

| DM2 | YYCARLPFSSVWDGSGFRGYNYFGLDVWGPGTTVTVSS |

The unique sequences (in bold) reveal that each antibody has arisen from a different recombination event.

Epitope mapping.

The ability of the recombinant Fab fragments to compete either with each other or with mouse MAbs for binding to affinity-purified F protein was examined by an inhibition ELISA. Fab fragment CM68 was biotin labeled and used to compete with the remaining unlabeled Fab fragments. As shown in Table 2, with the exception of RSV19, all of the F protein-specific Fab fragments appeared to compete with CM68, indicating that all of the recombinant antibodies, except for RSV19, are directed to a single antigenic site on the F protein. We next used CM68 to compete against mouse MAbs directed to four antigenic regions (A, AB, B, and C) of the F protein thought to be important targets for virus neutralization (3). The results are also presented in Table 2. Two mouse MAbs directed against the B site competed efficiently with the Fab fragments. In addition, a MAb recognizing the C site also consistently inhibited CM68 binding, albeit to a lesser extent than the B site-specific MAbs. Conversely, inhibition was not observed when CM68 was used to compete against MAbs binding to the A or AB antigenic site of the F protein or against RSV19.

TABLE 2.

Results of competitive ELISAs done to reveal the epitope specificities of human Fab fragments and their ability to compete with human polyclonal IgGa

| Fab fragment or IgG | Competitor

|

% Inhibition of binding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Designation (antigenic site) | ||

| CM68b | Human Fab fragment | RSV19 | 0.0 |

| CM2 | 96.8 | ||

| CM6 | 92.3 | ||

| CM68 | 87.0 | ||

| DM1 | 79.2 | ||

| DM2 | 93.9 | ||

| HIV b12 | 0.0 | ||

| CM68c | Mouse MAb | 151 (A) | 0.0 |

| 1129 (A) | 0.0 | ||

| 1107 (AB) | 0.0 | ||

| 1112 (B) | 100.0 | ||

| 1269 (B) | 81.1 | ||

| 1243 (C) | 59.0 | ||

| HIV b12 | 4.0 | ||

| IgGp1d | Human Fab fragment | RSV19 | 0.0 |

| CM2 | 49.3 | ||

| CM6 | 49.8 | ||

| CM68 | 42.1 | ||

| DM1 | 28.2 | ||

| DM2 | 49.8 | ||

| Pool of Fab fragments | 57.9 | ||

ELISA measurements were obtained as described in the text.

Inhibition of binding of CM68 to affinity-purified F antigen by human Fab fragments.

Inhibition of binding of CM68 to affinity-purified F antigen by mouse MAbs to different epitope sites.

Inhibition of binding of pooled normal human serum IgG to affinity-purified F antigen by human Fab fragments.

To weigh the importance of the antigenic site targeted by the recombinant Fab fragments within the context of the overall IgG response to the F protein, we used individual, and a pool of, nonneutralizing Fab fragments to compete with a pooled human serum polyclonal IgG for binding to the F protein. The results (Table 2) indicated that approximately one half of the overall IgG response to the purified F protein is directed toward the site targeted by the nonneutralizing Fab fragments.

The epitope of a potent neutralizing antibody is not present in purified F glycoprotein or in lysates of virus-infected cells.

In order to begin to better understand the properties that distinguish neutralizing from nonneutralizing antibodies, we measured the binding constants of each of the F protein-specific Fab fragments by using the BIAcore instrument. The binding kinetics were measured over a range of antibody concentrations against immobilized affinity-purified F protein. Kinetic analyses of the resulting sensograms yielded kon and koff values, and Kd values were determined as kon/koff (Table 3). Kd values obtained for the nonneutralizing Fab fragments ranged between 3.7 and 17 nM, suggesting that all of these antibodies bound to the affinity-purified antigen relatively tightly. To our surprise, however, Fab RSV19 bound to this antigen only very weakly, with a calculated Kd value of 6 μM. The efficiency with which this antibody neutralized virus in vitro (50% plaque reduction at approximately 0.2 μg/ml or 4 nM), via a mechanism which must proceed via Fab binding to F protein assembled into virion spikes, suggests that its overall binding constant for the F protein in this mature form is considerably higher (see below).

TABLE 3.

Kinetics of binding of recombinant Fab fragments to affinity-purified F antigen, as determined by surface plasmon resonance

| Fab fragment | kon (s−1 M−1) | koff (s−1) | Kd (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSV19 | 1.7 × 101 | 1.1 × 10−5 | 6,000 |

| CM2 | 5.1 × 104 | 1.9 × 10−4 | 3.7 |

| CM6 | 4.3 × 104 | 1.9 × 10−4 | 4.4 |

| CM68 | 1.9 × 104 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 6.2 |

| DM1 | 2.5 × 104 | 3.8 × 10−4 | 15.1 |

| DM2 | 8.1 × 104 | 1.4 × 10−4 | 17.0 |

To verify that the BIAcore measurements were not the result of the idiosyncratic properties of the affinity-purified F protein or the matrix used for protein capture, we coated ELISA wells with affinity-purified F protein and RSV-infected cell lysates and gauged the relative reactivities of Fab fragments RSV19 and CM68 with these antigen presentations (Fig. 1). Once again, RSV19 bound weakly to both antigens. In contrast, CM68 bound comparatively tightly. The approximate correspondence in the curves for affinity-purified F protein and cell lysates suggests that, as expected, since the former is purified from the latter, these antigens are broadly similar. The somewhat higher apparent affinities for binding to lysates than to affinity-purified F protein may reflect the harsher conditions used in the preparation of the affinity-purified material (11).

FIG. 1.

ELISA reactivity of recombinant Fab fragments RSV19 and CM68 with RSV-infected cell lysates (lysate) and affinity-purified F glycoprotein (APF).

A potent neutralizing antibody binds tightly to F protein on the surface of infected cells, whereas nonneutralizing antibodies bind weakly.

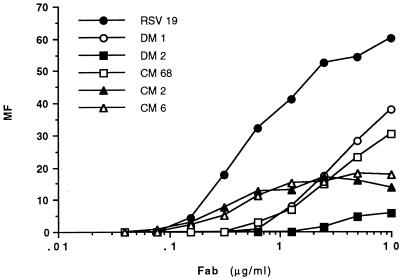

We next sought to determine how well the antibodies recognize the F protein as it occurs on the surface of virus-infected cells. Here the protein is likely to be organized into a mature, oligomeric structure, ready for incorporation into the envelope of budding virions. The ability of the recombinant antibodies to bind to RSV-infected HEp-2 cells was measured in a flow cytometry assay. Antibody binding profiles were produced by measuring the mean fluorescence of cell populations incubated with each antibody over a range of concentrations (Fig. 2). The data suggest that the relative affinities of the recombinant antibodies for mature F protein differ dramatically from those calculated for affinity-purified F protein. Whereas neutralizing Fab fragment RSV19 bound weakly to affinity-purified F protein, it bound considerably more tightly to F protein on the infected cell surface than did nonneutralizing Fab fragments (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Reactivity of recombinant Fab fragments with F protein on the surface of RSV-infected cells, as measured by flow cytometry. The MF of infected cells relative to that measured under the same conditions for uninfected cells was calculated following incubation with each antibody over a range of concentrations.

Quantitative correlation between antibody binding to viral envelope glycoproteins on the surface of infected cells and neutralizing activity.

The observations described above suggest that a key difference between neutralizing and nonneutralizing antibodies may be their relative capacities to recognize a mature envelope protein, such as that encountered on the surfaces of RSV-infected cells and virions. Support for this interpretation was sought by comparing Fab fragment RSV19 and polyclonal immune IgG for neutralizing activity and capacity to bind to the surface of RSV-infected cells. Flow cytometric analyses performed with RSV19 and polyclonal IgG preparations were used to calculate the antibody concentration required to produce 50% maximum binding to the infected cell surface. These values were then compared with the concentration of the same antibody preparation required to produce a 50% reduction of RSV plaque formation in an in vitro neutralization assay. Since the role of complement in clearing RSV infection has been documented previously (13), neutralization assays were performed without the addition of complement. The results are presented in Table 4. RSV19 neutralized virus efficiently (average neutralizing concentration, 0.23 μg/ml). The same antibody produced 50% maximum binding to RSV-infected cells at a similar concentration (0.58 μg/ml). There was a similar relationship between neutralization and binding for one of the polyclonal IgG preparations, and for the other preparation, neutralization was somewhat more efficient.

TABLE 4.

Concentrations of Fab fragment RSV19 and purified human polyclonal IgG preparations required to achieve 50% virus neutralization in vitro and 50% maximum binding to the RSV-infected cell surface

| Preparationa | Concn (μg/ml) required for 50%

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Maximum bindingb | Plaque reductionc | |

| RSV19 | 0.58 | 0.23 |

| IgGp1 | 64 | 11 |

| IgGp2 | 87 | 32 |

IgGp1 is a polyclonal IgG preparation from pooled human sera from two normal donors. IgGp2 is a polyclonal IgG preparation from an HIV-1-seropositive donor.

Measured by flow cytometry.

Measured as neutralization activity without complement by a plaque assay.

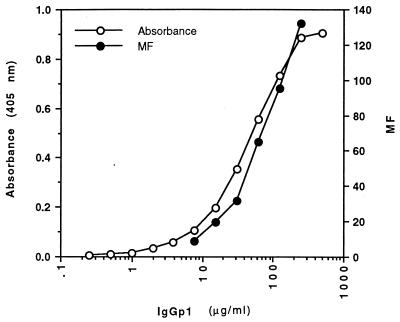

Relative proportions of antibodies reactive with purified F protein and mature oligomeric F protein in human antibody responses to RSV infection.

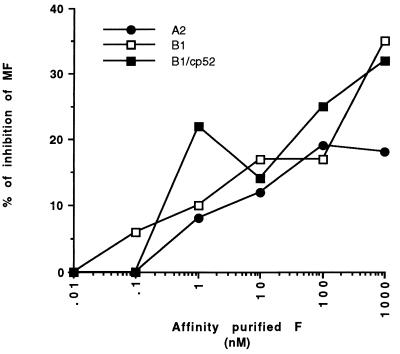

To obtain an estimate of the relative proportions of human antibodies induced to different envelope presentations of F protein as a result of RSV infection, a purified pooled polyclonal IgG preparation was titrated against affinity-purified F protein in an ELISA and against mature oligomeric F protein on infected cells by flow cytometry. Although saturation for binding to infected cells was not achieved, the data suggest approximately equivalent levels of binding to the two envelope presentations (Fig. 3). Only a portion of the observed binding to the two F glycoprotein presentations corresponded to the same antibody fraction of the polyclonal IgG preparation because excess affinity-purified F protein was able to inhibit only about 20% of the binding of IgG to infected cells (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Comparative binding of purified pooled human IgG to different antigenic presentations of F protein. The binding of human IgG (IgGp1) over a range of concentrations to affinity-purified F protein in an ELISA and to F protein as it occurs on the surface of RSV-infected cells was measured (the level of binding to G and SH proteins on the surface of infected cells is much lower than that to F protein; see the text).

FIG. 4.

Competition between human polyclonal IgG and affinity-purified F protein for binding to infected cells. Human IgG was incubated with a range of concentrations of affinity-purified F protein. Binding to cells infected with either A2, B1, or cp-52 virus was measured by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as the percentage of IgG bound in the absence of a competitor.

The foregoing interpretations are subject to the caveat that polyclonal IgG reactive with infected cells could be directed to the attachment (G) and small hydrophobic (SH) envelope glycoproteins as well as to the F glycoprotein. Accordingly, the inhibition experiment was repeated with cells infected with either the cp-52 mutant of a subgroup B RSV strain (21) or its wild-type parent, B1. Although replication competent in vitro, the cp-52 mutant contains a large genomic deletion that ablates the synthesis of the G and SH glycoproteins. We found the levels of pooled human serum IgG bound to cell populations infected with either mutant strain cp-52 or parent strain B1 to be similar (mean fluorescence values for infected cell populations, 95 and 120, respectively), suggesting that most of the serum reactivity with infected cells is directed to the F protein. This observation could indicate that a majority of all G protein-reactive antibodies in serum are directed to immature forms of the G protein and not to the G protein on the infected cell surface. Alternatively, however, the extensive antigenic and genetic diversity of the G protein, even among viruses of the same antigenic subgroup, may account for the low serum reactivity to this protein on cells infected with B1 virus.

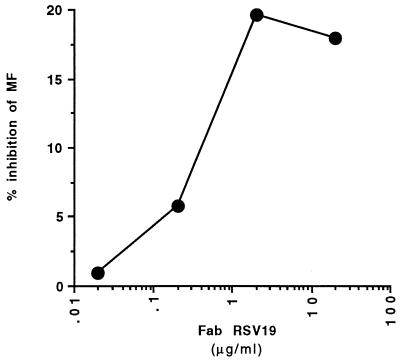

For cells infected with either cp-52 or B1 virus, saturating quantities (1 μM) of F protein reduced antibody binding in a competition assay by approximately 30% (Fig. 4). We interpret this result to mean that most of the IgG reactive with infected cells is not reactive with immature forms of F glycoprotein. However, epitope specificities other than that of RSV19 must be present in the antibodies reactive with infected cells, since RSV19 inhibited only about 20% of the total cell-bound IgG (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Competition between human polyclonal IgG and Fab fragment RSV19 for binding to infected cells. IgG binding to RSV-infected cells preincubated with a range of concentrations of RSV19 was determined by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as the percentage of IgG bound in the absence of the competing Fab.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we cloned a number of different F protein-specific antibodies by panning phage display libraries against purified and recombinant F antigens. The majority of the antibodies that were recovered were nonneutralizing, although their affinities for the antigens against which they were panned were in the nanomolar range. Using a competition ELISA, we observed that the nonneutralizing epitope region to which the bulk of the recombinant antibodies were directed was highly immunogenic and accounted for about one half of the total serum IgG reactivity against purified F protein (Table 2). These results are consistent with those of other studies (37, 38) in which a large panel of nonneutralizing antibodies was recovered by panning antibody phage libraries prepared from immune donors against a recombinant preparation of the extracellular portion of the F protein. In addition, Beeler and van Wyke Coelingh (3) also found that the ability of mouse MAbs to bind to F protein produced in a vaccinia virus recombinant was not predictive of their neutralizing activity.

In this study, the reason for the lack of neutralizing activity of many of the antibodies was shown to be their low affinity for mature oligomeric F protein present on the surface of RSV-infected cells and presumably also virions. In contrast, an antibody (RSV19 [2]) that exhibited a high level of neutralizing activity for RSV bound with a high affinity to mature oligomeric F protein but did not bind to purified F protein. This antibody was originally obtained by selection of a phage Fab library on an FG fusion protein preparation. It can only be hypothesized that this preparation must contain at least a fraction of the protein in a conformation akin to that of mature oligomeric F protein. Unfortunately, we have been unable to obtain more of this protein to test this hypothesis.

In any case, the results describe antibodies reactive with purified F protein and viral lysates and not with oligomeric F protein and vice versa. The simplest interpretation of the data is that two different immunogens are responsible. One immunogen appears to be immature F protein, as present in RSV-infected cell lysates and affinity-purified F protein prepared from such lysates. It is likely that a similar immature F protein is made available to the immune system following lysis of infected cells during natural infection. The other immunogen appears to be mature oligomeric F protein, as found on the surface of infected cells and virions. Studies with a polyclonal IgG from pooled human sera suggest that the two responses are of approximately equal magnitudes and that the degree of overlap of the two responses is relatively limited. Only 20 to 30% of the IgG response to mature oligomeric F protein could be inhibited by affinity-purified F protein, suggesting either that there is limited sharing of epitopes between mature and immature forms of F protein (up to 20 to 30% overlap of responses to mature and immature forms) or that some immature F protein is expressed on the surface of RSV-infected cells (no overlap).

A modification of the antigenic makeup of the envelope as it is assembled for presentation on the virion surface has potential evolutionary advantages. Immature forms of the envelope will be released from infected cells by cell lysis, possibly in relatively large amounts, during viral infection. This release will stimulate an antibody response that will be neutralizing if the antibodies react with the virion surface. Antigenic modification during envelope spike assembly can reduce the functional efficacy of this antibody response. The effect will be most noticeable if the mature envelope spike has a relatively low immunogenicity, as is the case for HIV-1 (6, 24). For RSV, however, there does appear to be a significant human antibody response to the mature envelope. In any case, in general, this factor may contribute to the limited success of subunit vaccines in eliciting efficient protective neutralizing antibody responses (4, 12, 31, 36), since viruses may have evolved to minimize antibody responses to the immature envelope molecules that are often used as the basis for subunit vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steve Whitehead and Brian Murphy for virus stocks.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI 39162.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbas C F, Collet T A, Amberg W, Roben P, Binley J M, Hoekstra D, Cababa D, Jones T M, Williamson R A, Pilkington G R, Haigwood N L, Cabezas E, Satterthwait A C, Sanz I, Burton D R. Molecular profile of an antibody response to HIV-1 as probed by combinatorial libraries. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:812–823. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbas C F, III, Crowe J E, Jr, Cababa D, Jones T M, Zebedee S L, Murphy B R, Chanock R M, Burton D R. Human monoclonal Fab fragments derived from a combinatorial library bind to respiratory syncytial virus F glycoprotein and neutralize infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10164–10168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beeler J A, van Wyke Coelingh K. Neutralization epitopes of the F glycoprotein of respiratory syncytial virus: effect of mutation upon fusion function. J Virol. 1989;63:2941–2950. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.2941-2950.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman P W, Gray A M, Wrin T, Vennari J C, Eastman D J, Nakamura G R, Francis D P, Gorse G, Schwartz D H. Genetic and immunologic characterization of viruses infecting MN-rgp120-vaccinated volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:384–397. doi: 10.1086/514055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourgeois C, Corvaisier C, Bour J B, Kohli E, Pothier P. Use of synthetic peptides to locate neutralizing antigenic domains on the fusion protein of respiratory syncytial virus. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:1051–1058. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-5-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton D R. A vaccine for HIV type 1: the antibody perspective. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10018–10023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton D R, Barbas C F. Human antibodies from combinatorial libraries. Adv Immunol. 1994;57:191–280. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60674-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burton D R, Barbas C F, Persson M A, Koenig S, Chanock R M, Lerner R A. A large array of human monoclonal antibodies to type 1 human immunodeficiency virus from combinatorial libraries of asymptomatic seropositive individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10134–10137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caton A J, Koprowski H. Influenza virus hemagglutinin-specific antibodies isolated from a combinatorial expression library are closely related to the immune response of the donor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6450–6454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coates H V, Alling D W, Chanock R M. An antigenic analysis of respiratory syncytial virus isolates by a plaque reduction neutralization test. Am J Epidemiol. 1966;83:299–313. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins P L, Mottet G. Post-translational processing and oligomerization of the fusion glycoprotein of human respiratory syncytial virus. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:3095–3101. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-12-3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor R I, Korber B T M, Graham B S, Hahn B H, Ho D D, Walker B D, Neumann A U, Vermund S H, Mestecky J, Jackson S, Fenamore E, Cao Y, Gao F, Kalams S, Kunstman K J, McDonald D, McWilliams N, Trkola A, Moore J P, Wolinsky S M. Immunological and virological analyses of persons infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 while participating in trials of recombinant gp120 subunit vaccines. J Virol. 1998;72:1552–1576. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1552-1576.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbeil S, Seguin C, Trudel M. Involvement of the complement system in the protection of mice from challenge with respiratory syncytial virus Long strain following passive immunization with monoclonal antibody 18A2B2. Vaccine. 1996;14:521–525. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(95)00222-M. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowe J E, Jr, Murphy B R, Chanock R M, Williamson R A, Barbas C F, Burton D R. Recombinant human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) monoclonal antibody Fab is effective therapeutically when introduced directly into the lungs of RSV-infected mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1386–1390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crowe J E, Jr, Bui P T, Davis A R, Chanock R M, Murphy B R. A further attenuated derivative of a cold-passaged temperature-sensitive mutant of human respiratory syncytial virus retains immunogenicity and protective efficacy against wild-type challenge in seronegative chimpanzees. Vaccine. 1994;12:783–790. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowe J E, Jr, Bui P T, Firestone C Y, Connors M, Elkins W R, Chanock R M, Murphy B R. Live subgroup B respiratory syncytial virus vaccines that are attenuated, genetically stable, and immunogenic in rodents and nonhuman primates. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:829–839. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dudas R A, Karron R A. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccines. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:430–439. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falsey A R, Walsh E E. Safety and immunogenicity of a respiratory syncytial virus subunit vaccine (PFP-2) in ambulatory adults over age 60. Vaccine. 1996;14:1214–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hexham J M, Partridge L J, Furmaniak J, Petersen V B, Colls J C, Pegg C A S, Smith B R, Burton D R. Cloning and characterisation of TPO autoantibodies using combinatorial phage display libraries. Autoimmunity. 1994;17:167–179. doi: 10.3109/08916939409010651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonsson U, Fagerstam L, Ivarsson B, Johnsson B, Karlsson R, Lofas L K, Persson B, Roos H, Ronnberg I. Real-time biospecific interaction analysis using surface plasmon resonance and a sensor chip technology. BioTechniques. 1991;11:620–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karron R A, Buonagurio D A, Georgiu A F, Whitehead S A, Adamus J E, Clements-Mann M L, Harris D O, Randolph V B, Udem S A, Murphy B R, Sidhu M S. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) SH and G proteins are not essential for viral replication in vitro: clinical evaluation and molecular characterization of a cold-passaged, attenuated RSV subgroup B mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13961–13966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karron R A, Wright P F, Crowe J E, Jr, Clements-Mann M L, Thompson J, Makhene M, Casey R, Murphy B R. Evaluation of two live, cold-passaged, temperature-sensitive respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in chimpanzees and in human adults, infants, and children. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1428–1436. doi: 10.1086/514138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez J A, Andreu D, Carreno C, Whyte P, Taylor G, Melero J A. Conformational constraints of conserved neutralizing epitopes from a major antigenic area of human respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2567–2577. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-12-2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore J P, Ho D D. HIV-1 neutralization: the consequences of viral adaptation to growth on transformed T cells. AIDS. 1995;9(Suppl. A):S117–S136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy B R, Collins P L. Current status of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and parainfluenza virus type 3 (PIV3) vaccine development: memorandum from a joint WHO/NIAID meeting. Bull W H O. 1997;75:307–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy B R, Hall S L, Kulkarini A B, Crowe J E, Jr, Collins P L, Connors M, Karron R A, Chanock R M. An update on approaches to the development of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and parainfluenza virus type 3 (PIV3) vaccines. Virus Res. 1994;32:13–36. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy B R, Rince G A, Walsh E E. Dissociation between serum neutralizing and glycoprotein antibody responses of infants and children who received inactivated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:197–202. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.2.197-202.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Null D, Bimle C, Weisman L, Johnson K, Steichen J, Singh S The Impact-RSV Study Group. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parren P W, I. H, Gauduin M-C, Koup R A, Poignard P, Sattentau Q J, Fisicaro P, Burton D R. Relevance of the antibody response against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope to vaccine design. Immunol Lett. 1997;58:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parren P W H I, Sattentau Q J, Burton D R. HIV-1 antibody—debris or virion? Nat Med. 1997;3:367–368. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-366d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piedra P A, Grace S, Jewell A, Spinelli S, Bunting D, Hogerman D A, Malinoski F, Hiatt P W. Purified fusion protein vaccine protects against lower respiratory tract illness during respiratory syncytial virus season in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Dis J. 1996;15:23–31. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Portolano S, Chazenbalk G D, Seto P, Hutchison J S, Rapoport B, McLachlan S M. Recognition by recombinant autoimmune thyroid disease-derived Fab fragments of a dominant conformational epitope on thyroid peroxidase. J Clin Investig. 1992;90:720–726. doi: 10.1172/JCI115943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prince G A, Hemming V G, Horswood R L, Chanock R M. Immunoprophylaxis and immunotherapy of respiratory syncytial virus infection in the cotton rat. Virus Res. 1985;3:193–206. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(85)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor G, Furze J M, Tempest P R, Bremner P, Carr F J, Harris W J. Humanised monoclonal antibody to respiratory syncytial virus. Lancet. 1991;337:1411–1412. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93091-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor G, Stott E J, Bew M, Fernie B F, Cote P J, Collins A P, Hugues M, Jerbett J. Monoclonal antibodies protect against respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. Immunology. 1984;52:137–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trudel M, Stott E J, Taylor G, Oth D, Mercier G, Nadon F, Séguin C, Simard C, Lacroix M. Synthetic peptides corresponding to the F protein of RSV stimulate murine B and T cells but fail to confer protection. Arch Virol. 1991;117:59–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01310492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsui P, Tornetta M A, Ames R S, Bankosky B C, Griego S, Silverman C, Porter T, Moore G, Sweet R W. Isolation of a neutralizing human RSV antibody from a dominant, non-neutralizing immune repertoire by epitope-blocked panning. J Immunol. 1996;157:772–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsui P, Tornetta M A, Ames R S, Bankosky B C, Griego S, Silverman C, Porter T, Moore G, Sweet R W. Isolation of RSV specific neutralizing human antibodies via blocked panning of Fab combinatorial phage libraries. In: Brown F, Burton D R, Mekalanos J, Norrby E, editors. Vaccines 96: molecular approaches to the control of infectious diseases. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh E E, Schlesinger J J, Brandriss M W. Protection from respiratory syncytial virus infection in cotton rats by passive transfer of monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1984;43:756–758. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.756-758.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weltzin R, Hsu S A, Mittler E S, Georgakopoulos K, Monath T P. Intranasal monoclonal immunoglobulin A against respiratory syncytial virus protects against upper and lower respiratory tract infections in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2785–2791. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.12.2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williamson R A, Burioni R, Sanna P P, Partridge L J, Barbas C F, Burton D R. Human monoclonal antibodies against a plethora of viral pathogens from single combinatorial libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4141–4145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]