Abstract

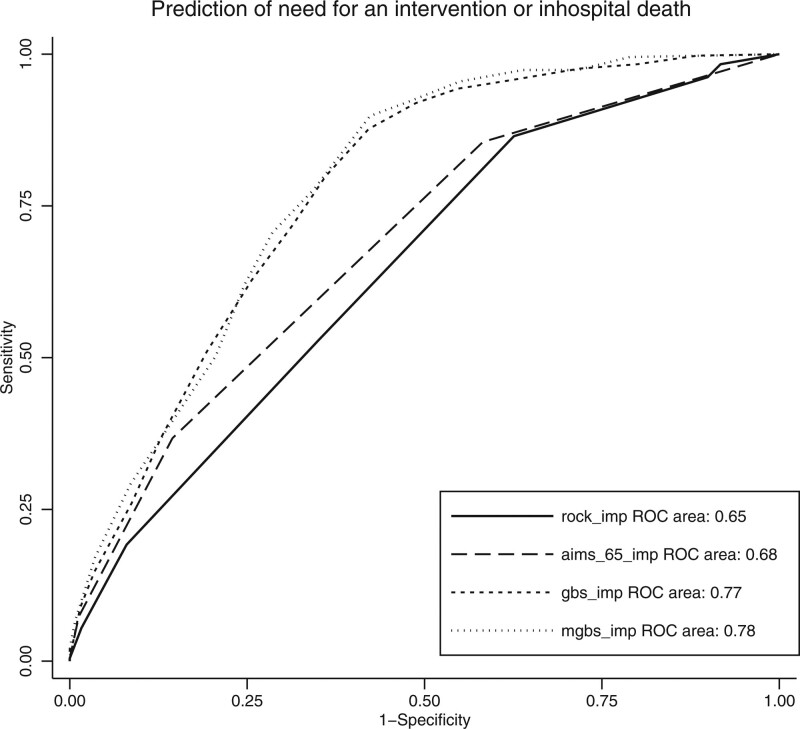

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) presents a high incidence in an emergency department (ED) and requires careful evaluation of the patient’s risk level to ensure optimal management. The primary aim of this study was to externally validate and compare the performance of the Rockall score, Glasgow-Blatchford score (GBS), modified GBS and AIMS65 score to predict death and the need for an intervention among patients with UGIB. This was a cross-sectional observational study of patients consulting the ED of a Swiss tertiary care hospital with UGIB. Primary outcomes were the inhospital need for an intervention, including transfusion, or an endoscopic procedure or surgery or inhospital death. The secondary outcome was inhospital death. We included 1521 patients with UGIB, median age, 68 (52–81) years; 940 (62%) were men. Melena or hematemesis were the most common complaints in 1020 (73%) patients. Among 422 (28%) patients who needed an intervention or died, 76 (5%) died in the hospital. Accuracy of the scoring systems assessed by receiver operating characteristic curves showed that the Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding and modified GBSs had the highest discriminatory capacity to determine inhospital death or the need of an intervention [AUC, 0.77 (95% CI, 0.75–0.80) and 0.78 (95% CI, 0.76–0.81), respectively]. AIMS65 and the pre-endoscopic Rockall score showed a lower discrimination [AUC, 0.68 (95% CI, 0.66–0.71) and 0.65 (95% CI, 0.62–0.68), respectively]. For a GBS of 0, only one patient (0.8%) needed an endoscopic intervention. The modified Glasgow-Blatchford and Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding scores appear to be the most accurate scores to predict the need for intervention or inhospital death.

Keywords: AIMS65 score, emergency department, endoscopy, Glasgow-Blatchford score, hematemesis, melena, risk assessment, Rockall score, upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Introduction

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is a common life-threatening condition that requires careful evaluation and risk stratification at initial admission to the emergency department (ED). Upper GIP (UGIB) is responsible for approximately 60% of GIB [1]. The annual incidence of GIB in the ED is estimated at around 100 cases per 100 000 population, with mortality reported to be 5–10% for patients admitted to hospital [2–4]. Main symptoms include hematemesis, melena and, less often, hematochezia and anemia [5]. Identification of acute significant bleeding is challenging and the estimation of the risk of recurrent bleeding or death can be difficult in the ED. Patients with UGIB without obvious bleeding are frequently admitted inhospital for surveillance and to perform an esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Consequently, some of these inhospital stays might lead to over-triage and overuse of specialized facilities.

Prognostic models enable to predict the risk of an adverse outcome. Several models and clinical scores have been developed to predict inhospital death or the need for an intervention and to discriminate between high- and low-risk UGIB patients [6]. Indeed, some observational studies showed that most low-risk patients could be safely discharged with outpatient care and a scheduled esophagogastroduodenoscopy [7]. Among the clinical scores, the Rockall score (RS), AIMS65 score and the Glasgow-Blatchford score (GBS) are the most frequently used. However, external validation of these scores was often performed in the same population at different time periods. Consequently, transportability represents a major limitation for the use of these scores in a different population. The aim of this study was to externally validate and compare the ability of these scores to predict the need for an intervention or inhospital death in a tertiary care hospital in Western Switzerland.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

We performed a retrospective, cross-sectional, observational study at the ED of Lausanne University Hospital, a tertiary care hospital in Western Switzerland with around 65 000 ED visits annually, based on clinical data collected by the hospital data warehouse. All patients more than 16 years of age who were admitted to the ED for UGIB between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2019 were included. UGIB was identified by symptoms at ED admission (hematemesis, melena and hematochezia) or other symptoms associated with an ED final diagnosis of GIB (syncope, hypotension, anemia, hemorrhagic shock or asthenia). Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, patients aged less than 16 years and patients refusing consent to analyze their data. The study was approved by the medical ethical committee of the Canton of Vaud (no: 2020-00515).

Data collection

We extracted all variables from the hospital data warehouse by collecting data from medical records and administrative files, as well as diagnostic and surgery coding databases. The following data were collected: demographic data (age and sex); date and time of admission; duration of hospitalization; past medical history; physiological data at admission [blood pressure, heart rate, respiration rate and level of consciousness according to the AVPU (Alert, Voice, Pain or Unresponsive scale)]; surgical interventions (type); endoscopic interventions; need for blood transfusion; level of triage priority from 1 to 4 (Swiss Emergency triage scale) including the main complaint at admission [8] and final diagnoses. We also collected laboratory data [hemoglobin, lactate, excess base, urea, albumin, blood transaminases, prothrombin time and international normalized ratio (INR), platelet count, plasma fibrinogen and activated prothromboplastin time] and therapeutic products used (norepinephrine, blood products, tranexamic acid, octreotide and esomeprazole). All variables included in each score are described in Supplement Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/EJEM/A353.

Comparison of clinical scores

The RS predicts mortality and was developed in 1996 from a study of 4185 patients with UGIB in the UK during the period 1993–1996 [9]. Since the full score requires endoscopic findings, an initial application for risk stratification is limited. Adaptation of the RS, based only on ‘pre-endoscopic’ clinical data (PERS), also predicted inhospital death and allowed early risk stratification. Considering our study aim, only PERS will be analyzed. PERS is obtained from three clinical variables: age at presentation; signs of shock (SBP and heart rate) and comorbidities (such as congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, any major comorbidity, renal failure, liver failure and disseminated malignancy). The minimum value of the score is 0 and the maximum is 7 (Supplement Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/EJEM/A353).

The AIMS65 score predicts mortality and was developed in 2011 in the USA, based on a retrospective study including 29 222 patients admitted for UIGB between 2004 and 2005 in 187 hospitals. The authors externally validated the AIMS65 1 year later on 32 504 patients included in the same national database used for its development. AIMS65 includes five clinical or laboratory variables: age at presentation; albumin, INR; alteration in mental status and SBP. This score has a narrow score spectrum (minimum value: 0 and maximum: 5) [10].

The GBS was developed in 2000 in the UK and based on 1748 patients with the objective of identifying a patient’s need for an intervention, defined as a blood transfusion, endoscopic or surgical intervention, or death, or rebleeding. GBS includes eight clinical or laboratory variables: blood urea nitrogen; hemoglobin (adapted for sex); SBP; heart rate; presentation with melena; presentation with syncope; presence of a hepatic disease (known history or clinical/laboratory evidence) and the presence of cardiac disease (known history or clinical/laboratory evidence). The minimum value of the score is 0 and the maximum is 23 [11]. According to the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, patients with a GBS score of 0–1 are considered to be at very low risk and do not require early endoscopy or hospital admission. These patients can be managed as outpatients, informed of the risk of recurrent bleeding, and advised to maintain contact with the discharging hospital [12]. The modified GBS (mGBS) predicts the need for an intervention (also defined as blood transfusion, endoscopic treatment or surgery) and represents a simple version of the GBS by omitting anamnestic variables potentially requiring interpretation or subjective judgment, which can increase the risk of bias [i.e. syncope, hepatic disease, cardiac disease and melena (minimum value: 0 and maximum value: 16)] [13].

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the need for an intervention or inhospital death. Need for intervention included blood transfusion (at least one red blood cell), or endoscopic treatment or surgery during hospital stay. Inhospital death includes all-cause of death. We chose this composite outcome to identify all adverse events that could occur (i.e. need for an intervention or inhospital death). In the ED, excluding these types of events can be a significant support in managing low-risk patients. The secondary outcome was inhospital death.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables are presented as either the mean and SD or median and interquartile range, as appropriate. Qualitative variables are expressed as numbers and proportions (percentage). We assessed the overall performance, discrimination and calibration of the scores. Overall performance was assessed by the Brier score, quantifying the distance between the predicted outcome and the actual outcome. We scaled the Brier score by its maximum to standardize for low incidence. The scaled Brier score ranges from 0 to 100% and indicates the degree of error in prediction, with 0% representing a perfect performance. The Brier score was not estimated for the GBS and mGBS scores as the authors did not report the predicted outcome.

Discrimination refers to the ability of a predictive model to discriminate between those with the outcome from those without. We estimated sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios for each threshold of the four scores. The discrimination of the risk scores was compared by plotting the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and estimating the area under the ROC (AUROC). We compared the C-statistic of each score for the primary outcome using the algorithm described by DeLong et al. [14].

Calibration relates to the agreement between the observed and predicted outcomes. We plotted a calibration graph for AIMS65 and the PERS score with the observed probability of death on predicted probability of death by the decile of score combined with a local polynomial regression (Loess algorithm). A perfect model has an intercept of 0 and a slope of 1 [15].

We managed missing values using multiple imputation by chained equation (MICE). We created 20 datasets with MICE and included all variables with missing values needed to estimate the different scores (urea, hemoglobin, blood pressure, heart rate, albumin, INR and AVPU scale). No explanatory variables (death, surgical or endoscopic interventions and transfusion) were missing. Missing values are reported for each variable in Table 1. Comorbidities were considered negative if they were not mentioned in the patient’s file. All analyses were performed using STATA software (version 16.0; Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Table 1.

Patients’ demographic and clinical features

| Missing values | Total | No intervention needed and alive | Intervention needed or death | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N = 1521 (%) | N = 1099 (%) | N = 422 (%) | |

| Male, N (%) | 0 (0) | 940 (62) | 669 (61) | 271 (64) |

| Female, N (%) | 0 (0) | 581 (38) | 430 (39) | 151 (36) |

| Median age (IQR) (years) | 0 (0) | 68 (52–81) | 65 (45–79) | 74 (63–83) |

| 16–24 (%) | 91 (6) | 90 (8) | 1 (0) | |

| 25–44 (%) | 356 (23) | 179 (16) | 25 (6) | |

| 45–64 (%) | 356 (23) | 265 (24) | 91 (21) | |

| 65–84 (%) | 610 (40) | 392 (36) | 218 (52) | |

| ≥85 (%) | 229 (15) | 173 (16) | 87 (21) | |

| SBP, mean (SD) | 208 (14) | 126 (21) | 128 (21) | 121 (22) |

| <90 mmHg, N (%) | 27 (2) | 7 (1) | 20 (5) | |

| HR, M (SD) | 206 (13) | 84.5 (17) | 83 (17) | 87 (17) |

| >100 bpm, N (%) | 209 (16) | 127 (14) | 82 (21) | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl), M (SD) | 25 (2) | 107 (32) | 116 (31) | 83 (23) |

| Mean INR, (SD) | 215 (14) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.6) |

| Creatinine (g/dl), M (SD) | 39 (3) | 107 (107) | 101 (110) | 123 (96) |

| Swiss Triage Scale (1–4), N (%) | ||||

| 1 | 122 (8) | 66 (5) | 32 (3) | 34 (9) |

| 2 | 569 (41) | 367 (36) | 202 (54) | |

| 3 | 760 (54) | 623 (61) | 137 (37) | |

| 4 | 4 (0) | 2 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Presenting symptoms | ||||

| Melena, N (%) | 0 (0) | 693 (49) | 492 (47) | 201 (54) |

| Hematemesis or melena, N (%) | 1020 (73) | 802 (73) | 218 (52) | |

| Syncope, N (%) | 173 (12) | 119 (11) | 54 (14) | |

| Hematochezia, N (%) | 89 (6) | 64 (6) | 25 (6) | |

| Comorbiditiesa | ||||

| Hepatic failure, N (%) | 308 (22) | 193 (19) | 115 (30) | |

| Coronary disease, N (%) | 250 (18) | 159 (16) | 91 (24) | |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 244 (17) | 159 (16) | 85 (22) | |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 594 (42) | 407 (40) | 187 (48) | |

| Renal failure, N (%) | 280 (20) | 182 (18) | 98 (26) | |

| Cancer, N (%) | 302 (21) | 188 (18) | 114 (30) | |

HR, heart rate; INR, international normalized ratio; IQR, interquartile range.

Comorbidities were considered negative if they were not mentioned in the patient’s file.

Results

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among 1718 identified patients visiting the ED for UGIB, 126 (7%) did not consent to the use of their data for research purposes. According to Swiss regulations, these patients were not considered for inclusion in the study. Thus, the medical records of 1549 patients visiting the ED for UIGB between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2019 were included. After exclusion of duplicates, a total of 1521 patients were included in the final analysis [male, 940 (62%); median age, 68 (52–81) years]. The most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (42%), hepatic failure (22%), renal insufficiency (20%) and malignancies (18%). Melena or hematemesis were the most common complaints recorded by the Swiss triage scale in 1020 (73%) patients. The remaining patients presented other symptoms at admission, syncope for 173 patients (12%), hematochezia for 89 patients (6%), hypotension for 31 patients (2%), and abdominal pain for 31 patients (2%). Seven hundred and twenty-four (48%) patients were treated with esomeprazole, 87 (6%) with octreotide, 30 (2%) with tranexamic acid, and 29 (2%) received noradrenaline.

Principal outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Four hundred and twenty-two patients (28% of the entire population) needed an intervention or died. Two hundred and seventy-seven (18%) patients needed a blood transfusion and 364 (24%) patients required an intervention (endoscopy, surgery or blood transfusion). Average duration of hospitalization was 7 days. We reported 76 (5%) inhospital deaths.

Table 2.

Outcomes

| Outcomes | N = 1521 (%) | % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||

| Need for interventiona or inhospital death | 422 (28) | (26–30) |

| Secondary outcome | ||

| Inhospital mortality, N (%) | 76 (5) | (4–6) |

| Intervention | ||

| Transfusion, N (%) | 277 (18) | (16-20) |

| Surgery | 0 | |

| Endoscopic intervention | 127 (8) | (7–10) |

| Discharge after ED | ||

| Hospitalization | 1049 (69) | (67–71) |

| IMCU or ICU | 193 (13) | (11–15) |

| Operation room after ED | 166 (11) | (9–13) |

| Home | 457 (30) | (28–33) |

| Death in the ED | 10 (1) | (0–1) |

ED, emergency department; IMCU, intermediate care unit.

Defined as the need for transfusion or an endoscopic procedure or surgical intervention.

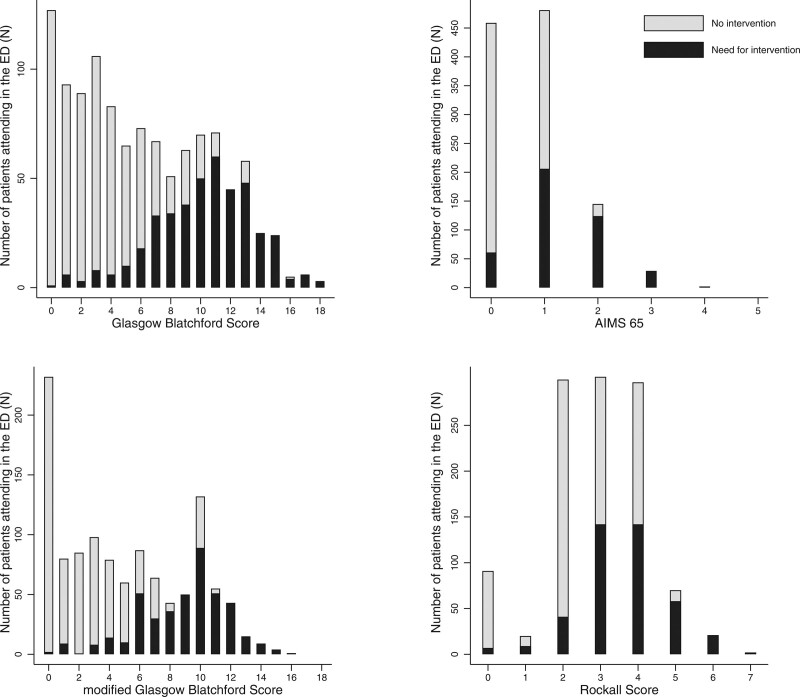

Performance indicators of clinical scores are summarized in Table 3. The Brier score was 0.046 for AIMS65 and 0.0647 for PERS. The scaled Brier score was 20% for both scores. As GBS does not provide a predicted probability of outcome, we were unable to estimate the Brier score. AUROC for the primary outcome is summarized in Fig. 1. The primary outcome showed an AUROC of 0.78 and 0.77 for mGBS and GBS score systems, respectively, followed by PERS with 0.65 and AIMS65 with 0.68. mGBS and GBS were higher than PERS and AIMS65 (P < 0.001). There was no statistical difference between mGBS and GBS (P = 0.06). Sensitivity and specificity for different thresholds are summarized in Supplementary Fig 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/EJEM/A353. Endoscopic intervention occurred in only one patient (0.8%) with a GBS and mGBS of 0. The number of interventions or deaths for each score value are shown in Fig 2. The need for intervention or inhospital death occurred in 7 patients (3%) with a GBS of 0 or 1. Calibration slopes, intercepts and calibration-in-the-large are summarized in Table 3 and in Supplementary Fig 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/EJEM/A353. Predicted mortality (calibration-in-the-large) for AIMS65 was 1.9% [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.8–2.0] and 16.2% (95% CI, 15.7–16.9) for PERS. The calibration curve of the AIMS65 score showed an underprediction and an overprediction for PERS. Sensibility, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratio are presented in Supplement Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/EJEM/A353.

Table 3.

Score results

| AIMS65 | Pre-endoscopic Rockall (PERS) | Glasgow-Blatchforda | Modified Glasgow-Blatchforda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall performanceb | ||||

| Brier score | 0.0464 | 0.0647 | - | - |

| Scaled Brier score (%) | 20.1 | 19.7 | - | - |

| Discrimination (AUROC) (95% CI) Primary outcome | 0.684 (0.657–0.711) | 0.647 (0.618–0.675) | 0.774 (0.750–0.798) | 0.782 (0.759–0.805) |

| Discrimination (AUROC) (95% CI) Secondary outcome (inhospital death) | 0.786 (0.744–0.827) | 0.719 (0.663–0.776) | 0.685 (0.631–0.740) | 0.702 (0.649–0.755) |

| Calibrationb (95% CI) | ||||

| Observed inhospital death | 5.0% (3.9–6.1) | 5.0% (3.9–6.1) | - | - |

| Predicted inhospital death | 1.9% (1.77–2.01) | 16.28% (15.67–16.89) | ||

| Calibration-in-the-large, P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Slope | 2.355 (1.899–2.811) | 0.348 (0.260–0.436) | ||

| Intercept | 0.005 (−0.008 to 0.019) | −0.006 (−0.024 to 0.012) | ||

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic; CI, confidence interval.

As the Glasgow-Blatchford score did not predict a probability of the outcome, the Brier score and calibration were not feasible.

As AIMS65 and PERS predict inhospital death, Brier score and calibration were assessed for the secondary outcome.

Fig. 1.

Discrimination of scores predicting the need for intervention or death (AUROC). AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic.

Fig. 2.

Number of events needed for an intervention by score. ED, emergency department.

Discussion

Regarding our primary outcome, the performance of AIMS65 and PERS was unsatisfactory and their clinical use cannot be recommended. However, mGBS and GBS presented a good performance with an AUC of 0.78 and 0.77, respectively. Concerning our secondary outcome, performance was good for AIMS65 and PERS, with an AUROC of 0.78 and 0.71, respectively. PERS showed a better calibration than AIMS65. A GBS or mGBS of 0 safely identified patients with no need for an intervention.

Blatchford et al. [11] enrolled 1748 patients to develop the GBS score and reported an AUROC of 0.92, significantly better discrimination than observed in our study. They prospectively performed an external validation of the study and reported a high discrimination [11]. However, the validation cohort was chronologically different, but not geographically divergent from the derivation cohort, thus resulting more in a study assessing reproductivity than a real external validation study. By contrast, our study population is geographically and chronologically different and represents a true external validation. Of note, two recent external validation studies found a similar AUROC (approximately 0.8) to our study [16,17].

A multicentre validation conducted by Stanley et al. [18] in 2017 among 3021 patients reported similar results with an AUROC of 0.69 for PERS and 0.68 for AIMS65 related to a need for intervention or death. Indeed, our results regarding inhospital death are comparable to other external validation studies. GBS discrimination for predicting death is lower (AUROC, 0.7) than predicting the need for an intervention, as observed in other external validations [16,18,19]. Saltzmann et al. [10] found an AUROC of 0.80 for the AIMS65 in the derivation cohort and 0.77 in the validation cohort for inhospital death. We found similar results with an AUROC of 0.78. Other external validation studies also showed comparable results to our study, with an AUROC of 0.78 for Stanley et al. [18], and 0.80 for Robertson et al. [20]. PERS performance, with an AUROC of 0.72, was also in line with other studies and performed slightly worse than AIMS65 [20,21].

Clinical implications

The mGBS and GBS seemed more accurate than others to predict the need for an intervention or death. Of note, these scores were developed to predict the need for an intervention, whereas PERS and AIMS65 were developed to predict mortality. It is clinically relevant to predict the need for an intervention rather than inhospital death as the main objective of risk stratification is to identify patients who can be discharged from the ED. We showed that a GBS or an mGBS of 0 was safe to exclude a patient with UGIB from the ED, with only one event for a GBS of 0 (0.06%) and this posttest prediction of less than 1% represents an acceptable probability. Current European guidelines recommend that patients with GBS ≤ 1 can be safely managed as outpatients. This study confirmed that these patients have a very low risk of death and only 3% present a need for an intervention. The performance of PERS and AIMS65 in predicting the need for an intervention or death was too weak to have any clinical use. Of note, mGBS presented similar performance indicators than GBS and is more suitable for clinical use. The percentage of patients needing an intervention or dying increased progressively from a threshold of a GBS or mGBS of 1–5. This range includes low-to-moderate risk patients. Clinical expertise and shared decision-making with patients are crucial in these groups.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths and limitations. First, we included patients at initial presentation in the ED, representing an inception cohort. Second, we did not report any missing values for follow-up inhospital death. However, due to the retrospective design, we cannot exclude missing values for interventions (transfusion, surgical or endoscopic intervention) if they were not reported or identified in the data warehouse. We cannot also exclude that discharged patients had an intervention in another healthcare facility. The retrospective design may introduce recall bias that increase the risk of misclassification. Third, 126 patients were not considered for inclusion because of their refusal to consent to the use of their health-related data. Even if this represents a small number of patients selected at random, it may have led to selection bias. Fourth, we used the first reported value for estimating each score. Error measurement might have led to regression dilution bias, thus decreasing the C-statistic of each score. Fifth, we used rigorous methods for the assessment of each score using all the characteristics of a prognostic model (overall performance, discrimination and calibration). Sixth, the large sample size with more than 1500 patients provides precise and reliable measures. Seventh, the single-center design decreases the external validity. PERS and GBS were developed almost 2 decades ago and mortality related to UIGB has changed slightly since then, which may have affected calibration with current practice and limited external validity. However, the aim of the study was to assess external validation in a different population from the derivation cohort of each score. Finally, data from our ED population in Western Switzerland may not be applicable to other geographic regions.

These scores were developed to predict generic or composite outcomes (death and the need for an intervention or death). Regarding mortality, death associated with UGIB could occur from other causes than bleeding itself (cancer, pulmonary embolism during hospitalization, etc.) Consequently, overall mortality is not a reliable outcome. Decision-making for an immediate intervention in the ED is more associated with initial bleeding than later death due to cancer evolution. Scores predicting initial death or death due to bleeding could improve decision-making in the ED and a prospective validation study of a clinical protocol including a prediction score is needed to validate the usefulness of a score integrating clinical decision-making.

Conclusion

In this retrospective study, mGBS and GBS appear to be the most accurate scores to predict the need for urgent intervention or death. The use of these scores could help in decision-making. However, clinical judgment remains essential, especially in low-to-moderate risk patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alexandre Wetzel and David Caillet-Bois for data collection and extraction.

S.R., F.X.A. and P.N.C. designed the study. S.R. and F.X.A. designed and monitored the data collection from which this paper was developed. S.R. and F.X.A. analyzed the data. S.R. and F.X.A. wrote the first draft. S.R., F.X.A., A.S. and P.N.C. contributed to the writing and revision of the paper.

Availability of data and materials: data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website (www.euro-emergencymed.com).

References

- 1.Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Polo-Tomás M, Ponce M, Alonso-Abreu I, Perez-Aisa MA, et al. Time trends and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104:1633–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scherdin Y, Halldestam I, Redeen S. Incidence and mortality related to gastrointestinal bleeding, and the effect of tranexamic acid on gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Res 2021; 14:165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laine L, Yang H, Chang SC, Datto C. Trends for incidence of hospitalization and death due to GI complications in the United States from 2001 to 2009. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:1190–5; quiz 1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Leerdam ME. Epidemiology of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2008; 22:209–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiebaud PC, Yordanov Y, Galimard JE, Raynal PA, Beaune S, Jacquin L, et al. ; Initiatives de Recherche aux Urgences Group. Management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in emergency departments, from bleeding symptoms to diagnosis: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017; 25:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oakland K. Risk stratification in upper and upper and lower GI bleeding: which scores should we use? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2019; 42-43:101613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laursen SB, Dalton HR, Murray IA, Michell N, Johnston MR, Schultz M, et al. ; Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage International Consortium; Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage International Consortium. Performance of new thresholds of the Glasgow Blatchford score in managing patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13:115–21.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutschmann OT, Hugli OW, Marti C, Grosgurin O, Geissbuhler A, Kossovsky M, et al. Reliability of the revised Swiss Emergency Triage Scale: a computer simulation study. Eur J Emerg Med 2018; 25:264–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut 1996; 38:316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saltzman JR, Tabak YP, Hyett BH, Sun X, Travis AC, Johannes RS. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 74:1215–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet 2000; 356:1318–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gralnek IM, Stanley AJ, Morris AJ, Camus M, Lau J, Lanas A, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2021. Endoscopy 2021; 53:300–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng DW, Lu YW, Teller T, Sekhon HK, Wu BU. A modified Glasgow Blatchford Score improves risk stratification in upper gastrointestinal bleed: a prospective comparison of scoring systems. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36:782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988; 44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steyerberg EW. Clinical Prediction Models [Internet]. Springer New York; 2009. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-0-387-77244-8. [Accessed 30 July 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang A, Ouejiaraphant C, Akarapatima K, Rattanasupa A, Prachayakul V. Prospective comparison of the AIMS65 score, Glasgow-Blatchford score, and Rockall score for predicting clinical outcomes in patients with variceal and nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Endosc 2021; 54:211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan JCH, Ayaru L. Analysis of risk scoring for the outpatient management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Frontline Gastroenterol 2011; 2:19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanley AJ, Laine L, Dalton HR, Ngu JH, Schultz M, Abazi R, et al. ; International Gastrointestinal Bleeding Consortium. Comparison of risk scoring systems for patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: international multicentre prospective study. BMJ 2017; 356:i6432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyett BH, Abougergi MS, Charpentier JP, Kumar NL, Brozovic S, Claggett BL, et al. The AIMS65 score compared with the Glasgow-Blatchford score in predicting outcomes in upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 77:551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson M, Majumdar A, Boyapati R, Chung W, Worland T, Terbah R, et al. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems. Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 83:1151–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim MS, Choi J, Shin WC. AIMS65 scoring system is comparable to Glasgow-Blatchford score or Rockall score for prediction of clinical outcomes for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMC Gastroenterol 2019; 19:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.