Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the end of 2019 led to profound consequences on global health and economy. Till producing successful vaccination strategies, the healthcare sectors suffered from the lack of effective therapeutic agents that could control the spread of infection. Thus, academia and the pharmaceutical sector prioritise SARS-CoV-2 antiviral drug discovery. Here, we exploited previous reports highlighting the anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities of isatin-based molecules to develop novel triazolo-isatins for inhibiting main protease (Mpro) of the virus, a crucial enzyme for its replication in the host cells. Particularly, sulphonamide 6b showed promising inhibitory activity with an IC50= 0.249 µM. Additionally, 6b inhibited viral cell proliferation with an IC50 of 4.33 µg/ml, and was non-toxic to VERO-E6 cells (CC50 = 564.74 µg/ml) displaying a selectivity index of 130.4. In silico analysis of 6b disclosed its ability to interact with key residues in the enzyme active site, supporting the obtained in vitro findings.

Keywords: Isatin derivatives, click chemistry, SARS-CoV-2, main protease, FRET assay and moleuclar docking

Introduction

Since the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic in 2019, the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 has resulted in more than 620 million confirmed cases and the deaths of millions of people1, making it one of the most catastrophic global health disasters in human history2. There are now only a few SARS-CoV-2 medicines available, despite the widespread approval of vaccination3,4. In addition to this, the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants that are effective poses a threat to the efficacy of vaccines developed for the purpose of controlling COVID-19 infection5,6. Hence, the search for effective therapeutic drugs to combat SARS-CoV-2 is urgently needed.

In the search for inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2, several viral targets that are essential to the replication of the virus are being investigated. One of these viral targets is the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro)7. The 1a/1ab polyprotein (pp), which is the target of Mpro’s proteolytic activity8, is hydrolysed into 16 mature non-structural proteins (NSPS)9. These proteins play crucial roles in the initial stages of the SARS-CoV-2 replication cycle, including the synthesis of RNA of the virus, the rearrangement for the host cell cytoplasmic organelles to create environments favourable for viral replication, the production of structural, and construction of new viral particles which eventually would be released to other host cells. The Protomers A and B constitute the homodimer protease which are responsible for the catalytic function of enzyme through thiol group of Cys145 and deprotonated His41 which is considered as the catalytic dyad of Mpro10. Hence, the disruption of the catalytic activity of Mpro may therefore be a useful and promising strategy, as demonstrated by the clinical success of nirmatrelvir, the first Mpro inhibitor to enter into clinical use11.

There are two categories of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors, non-covalent inhibitors like X77 and ML188 or covalent inhibitors (such as N3 and GC376)12. The covalent inhibitor forms a covalent bond with catalytic dyad, which blocks the binding site. On the other hand, non-covalent inhibitor does not require covalent binding to block the Mpro enzyme7. Despite the advantages of covalent inhibitors and their current resurrection, concerns about their safety, such as the possibility of off-target effects and delayed effects, have always hampered the development of such new medications, although, as mentioned above, nirmatrelvir constitutes an exception13–14.

Presently, the isatin motif (Figure 1) is highly valuable in the area of pharmaceutical chemistry and drug design15. Since it can be found and isolated from several natural resources and its synthetic accessibility, the isatin scaffold has been used to prepare novel derivatives with plethora of pharmacological properties such as anticancer16–19, antibacterial20–21, anti-tubercular22–24, antimalarial25–26, antileishmanial27–28, and antiviral activities29. In particular, there has been a surge of interest in the recent decades to explore the biological effect of diverse isatin-based small molecules towards a wide range of pathogenic viruses. For example, the antiviral activities for diverse isatin derivatives were reported against HIV30–32, arbovirus33, chikungunya virus34, herpes simplex virus (HSV)35, coxsackievirus36, poxvirus37, and influenza virus38.

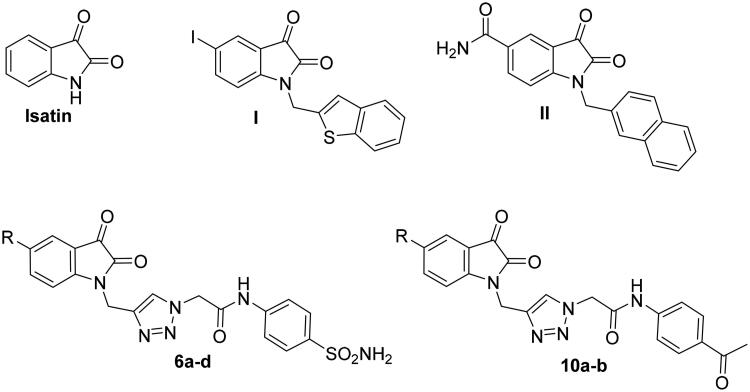

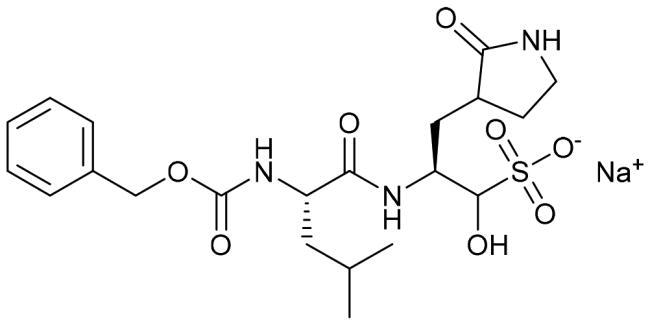

Figure 1.

Structures of isatin and some reported main SARS-CoV protease inhibitors (I and II), as well as the target triazolo isatins (6a-d and 10a-b).

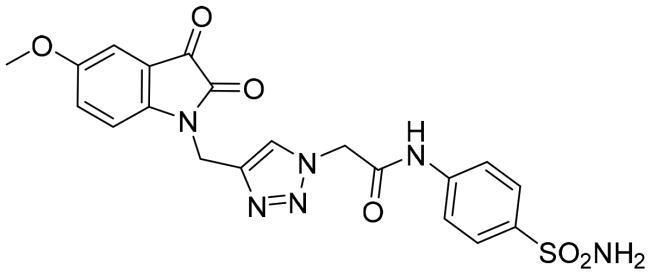

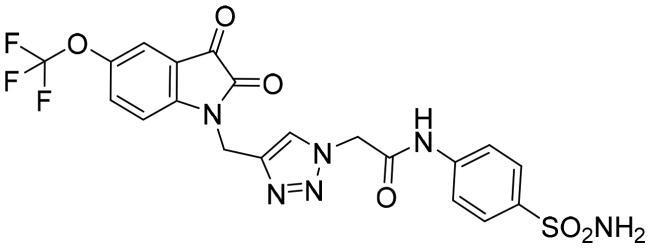

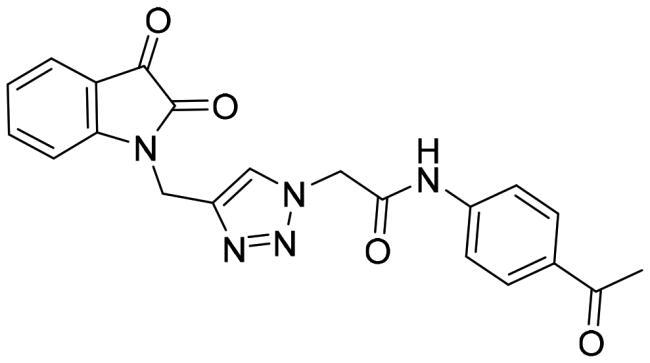

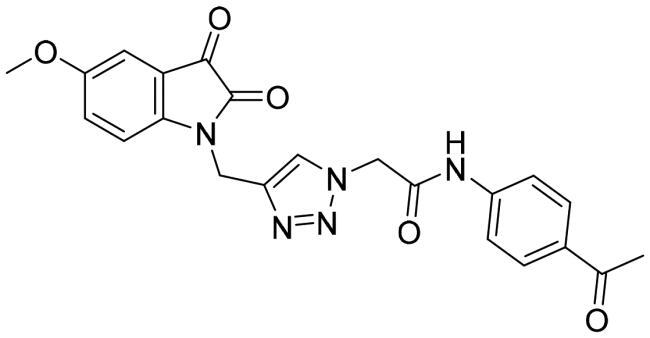

Furthermore, many investigations have been conducted in order to afford isatin analogues as effective inhibitors of SARS-CoV main protease39–43. Chen et al., in 2005, described the synthesis of N-substituted isatin derivatives endowed with a good inhibitory impact towards SARS-COV main protease in the low micromolar range (IC50: 0.95–17.50 μM). Among this series, compound I (Figure 1) emerged as the most promising inhibitor with IC50 equals 0.95 μM41. Recently, Liu et al assessed the antiviral activity of other new N-substituted isatin-based molecules, by targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease43. The reported isatins demonstrated effective inhibitory activity against the tested protease, with compound II (Figure 1) standing out as the most promising candidate in that study (IC50 = 0.045 μM).

Since previous studies spot the light on the potential activity of N-substituted isatins, we were inspired to design a novel set of derivatives (6a-d and 10a-b) as potential inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Figure 1). The proposed derivatives were synthesised, characterised and evaluated using Fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based analysis to evaluate their inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

The synthetic strategy was designed in order to retain the dione system which is characteristic to the isatin motif so that it could form an essential hydrogen bonding with important residues such as Cys145. Also, the N-substitution was decorated with the privileged triazole nucleus, which could enhance pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile, as well as incorporated an amide linker that could achieve some important interactions. Lastly, the appended phenyl ring was grafted with a sulfamoyl functionality to afford the first series (6a-d), whereas in the second series the ketone group was exploited (10a-b), Figure 1.

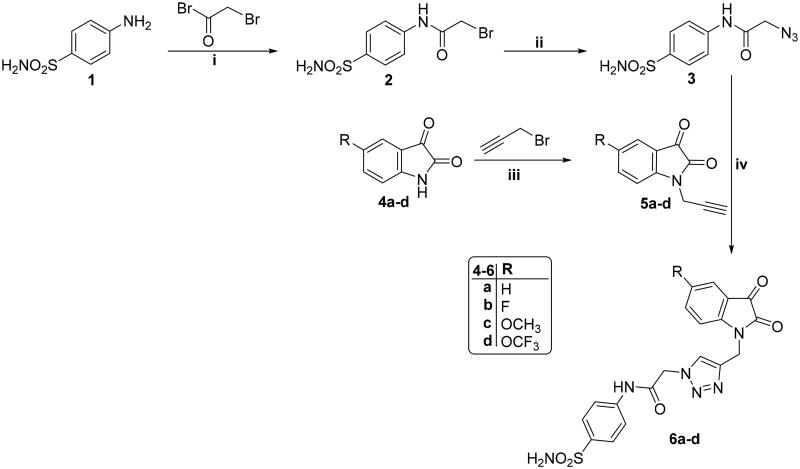

The preparation of triazolo-isatins (6a-d and 10a-b), utilised in this work, is demonstrated in Schemes 1 and 2. Acylation of the basic amino functionality in sulphanilamide 1 to afford 2-bromo-N-phenylacetamide 2, was achieved through stirring in dry dioxane at room temperature and in the presence of K2CO3, then, intermediate 2 was dissolved in dry dimethyl formamide and stirred with sodium azide at room temperature to furnish 2-azido-N-(4-sulfamoylphenyl)acetamide 3. On the other hand, isatins 4a-d were alkylated with propargyl bromide in dry acetonitrile and in presence of K2CO3 to produce the corresponding N-propargyl isatins 5a-d, which further reacted with 2-azido-N-(4-sulfamoylphenyl)acetamide 3 through Azide-alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition in order to produce the target sulphonamide-tethered triazolo isatins 6a-d (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Reagent and conditions: (i) Dry dioxane, K2CO3, stirring r.t., 12 h; (ii) NaN3, DMF, stirring r.t., 8 h; (iii) Dry acetonitrile, K2CO3, Stirring r.t., 10 h; (iv) DMF/H2O, CuSO4.5H2O, sodium ascorbate, heating at 60 °C, 7 h.

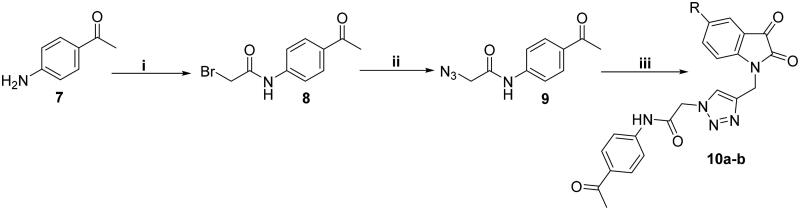

Scheme 2.

Reagent and conditions: (i) Dry dioxane, K2CO3, stirring r.t., 12 h; (ii) NaN3, DMF, stirring r.t., 8 h; (iii) 5a or 5c, DMF/H2O, CuSO4.5H2O, sodium ascorbate, heating at 60 °C, 7 h.

In Scheme 2, we aimed at replacing the sulphonamide functionality in the first series with a ketone group. N-(4-acetylphenyl)-2-azidoacetamide 9 was synthesised in the same way that 2-azido-N-(4-sulfamoylphenyl)acetamide 3 was. Thereafter, azide 9 was reacted with N-propargyl isatins 5a and 5c via the azide-alkyne cycloaddition click reaction to furnish the target triazolo isatins 10a-b (Scheme 2). The structure of the prepared derivatives of triazolo isatin was well characterised and confirmed through interpretation of the spectral and the elemental analyses data.

Biological evaluation

SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitory assay

The newly synthesised triazolo isatins (6a-d and 10a-b) were assessed for their inhibitory impact on the main protease of SARS-CoV-2, using GC376 as a standard inhibitor. The inhibition data for the examined molecules were reported as median inhibition concentrations (IC50) and displayed in Table 1, Figure S1.

Table 1.

In vitro inhibitory effect of target triazolo isatins (6a-d and 10a-b) against 3CL-Pro, using (GC376) as a standard drug.

| Comp. | R | aIC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| 6a |

|

0.562 ± 0.005 |

| 6b |

|

0.249 ± 0.006 |

| 6c |

|

0.939 ± 0.007 |

| 6d |

|

1.054 ± 0.053 |

| 10a |

|

12.28 ± 0.73 |

| 10b |

|

17.075 ± 0.815 |

| GC376 |

|

0.063 ± 0.001 |

Mean from two different assays.

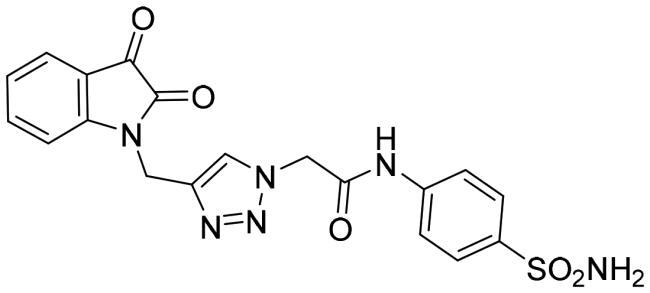

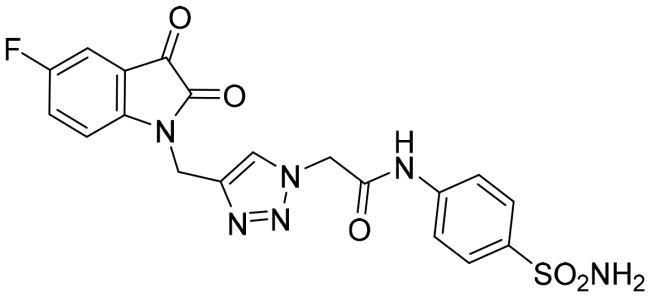

The data listed in Table 1 disclosed that the examined 3CL-Pro was inhibited by the herein described triazolo isatins in a variable degree. The target sulphonamide-tethered triazolo isatins 6a-d effectively inhibited 3CL-Pro with IC50 values spanning from 0.249 to 1.054 μM. Compounds 6a-c showed the ability to exert sub-micromolar inhibition; IC50 equal 0.562 ± 0.005, 0.249 ± 0.006 and 0.939 ± 0.007 μM, respectively, whereas compound 6d displayed low-micromolar inhibitory activity (IC50 = 1.054 ± 0.053 μM). Incorporation of unsubstituted isatin motif resulted in compound 6a with good inhibitory activity (IC50 = 0.562 μM). Fluorine is exploited as an isostere for the hydrogen atom since its similar to hydrogen in terms of size and electronic characteristics. Triazole derivative 6b bearing fluorine substituent at the isatin C-5 showed an increase in the 3CL-Pro inhibitory activity suggesting that the C-5 substitution is tolerated and also highlighting that the halogens incorporation may be advantageous. Moreover, grafting methoxy or trifluoromethoxy group led to compounds 6c and 6d with about 2-fold decreased activity (IC50 = 0.939, and 1.054 μM, respectively) than their unsubstituted counterpart 6a.

On the other hand, the introduction of acetyl instead of the sulphonamide functionality (compounds 10a and 10b) resulted in a dramatic decrease in the 3CL-Pro inhibitory action (IC50 = 12.28, and 17.075 μM, respectively) hinting out that incorporation of the sulphonamide group is a crucial element for the activity.

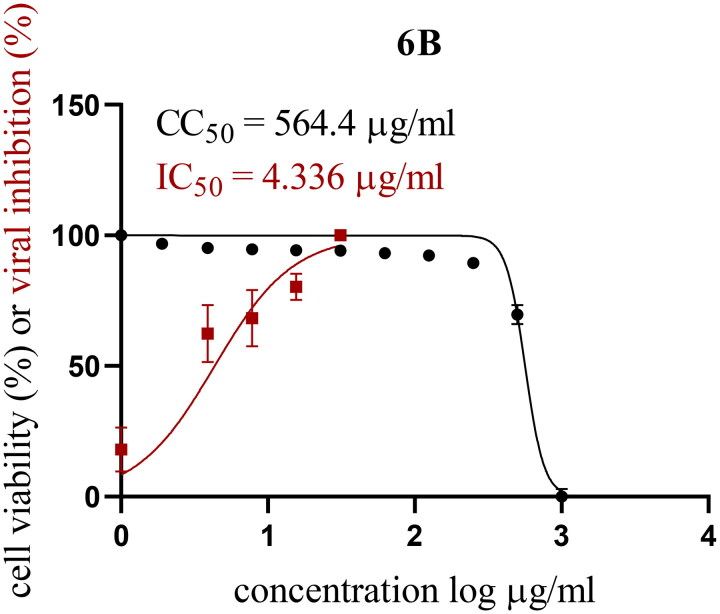

The SARS-CoV-2 inhibitory assay (Cell-Based)

Since compound 6b showed the best inhibitory effect against 3CL-Pro of SARS-CoV-2 established, its cellular antiviral activity was further assessed. Firstly, MTT assay was exploited to determine the cytotoxicity of 6b against VERO-E6 cell line. According to the data, 6b has a favourable safety profile with a cytotoxicity concentration 50 (CC50) value of 564.74 µg/ml, which indicates that it has no significant impact on the survival of healthy, uninfected cells (Figure 2). Thereafter, the ability of 6b to reduce the viability of SARS-CoV-2 cells was further investigated.

Figure 2.

CC50 and IC50 values for isatin derivative 6b.

Remarkably, compound 6b exerted promising cell growth inhibitory activity with IC50 = 4.33 µg/ml that results in a safety index equals 130.4, suggesting that 6b has good activity against SARS-CoV-2 in-vitro without causing toxicity to the host cells (Figure 2). This outcome is most likely associated with 6b’s capacity to efficiently inhibit the 3CL-Pro enzyme, as previously described.

Molecular modeling studies

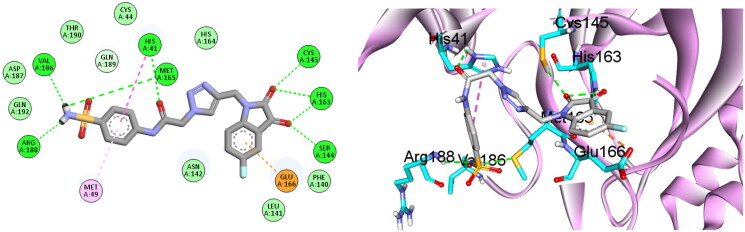

Docking studies

Molecular docking was proved to be a valuable tool to recognise the interactions of enzyme inhibitors44–48. Hence, we utilised molecular docking to gain an insight on the binding profile of isatin derivative 6b with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme active site. As a start, redocking the co-crystalised ligand GC-14 into its binding site was preformed to ensure the capability of the software to reproduce experimental pose in RMSD less than 1.5 Å. Since the calculated RMSD of the redocked pose was found to be 0.83, the docking protocol was considered valid. As depicted in Figure 3, the interaction of the co-crystalised ligand with the binding site could be summarised in its ability to form several interactions with the critical amino acids such as His 41, Met 49, Leu 141, Gly 143, Cys 145, Met 165 and Glu 166.

Figure 3.

Redocking of the co-crystalised ligand GC-14 into SARS-CoV-2 Mpro binding site.

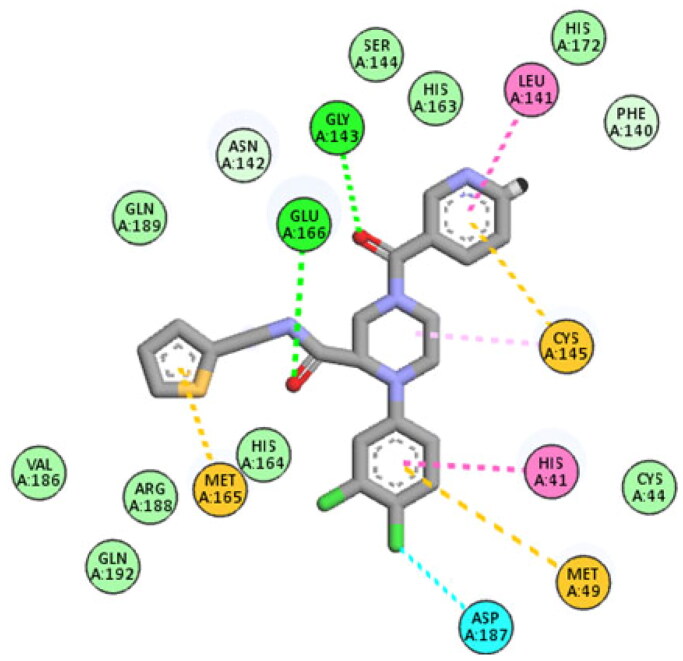

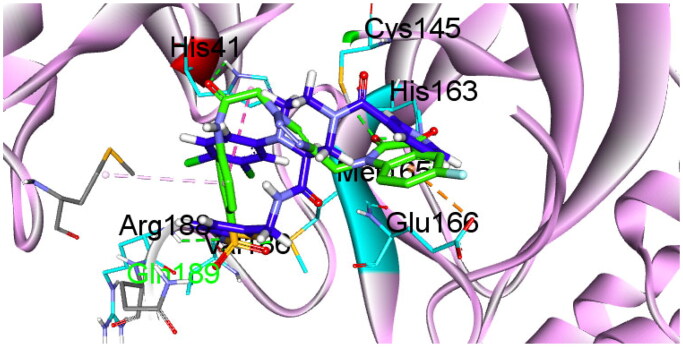

It’s interesting to note that compound 6b shared a similar binding mechanism with the co-crystallized ligand, as presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Compound 6b (in green) in 3D style overlaid with GC-14 (in blue).

The isatin ring of 6b interacted with Ser 144, Cys 145 through hydrogen bonding and one hydrophobic interaction with Glu166. Moreover, one hydrogen bond with His41 was formed through carbonyl of the amide linker formed. Furthermore, three hydrogen bonds with Met 165, Val 186 and Arg 188, were established through sulphonamide group in addition, the phenyl ring appended to the sulphonamide functionality formed two hydrophobic interactions with His 41 and Met 49 (Figure 5). Finally, compound 6b achieved binding energy of −10.7 Kcal/mol better than that for the co-crystalised (-9.8 Kcal/mol). To this end, the good binding mode and excellent docking score of compound 6b highlights its ability to inhibit SARS CoV-2 Mpro through several types of interactions.

Figure 5.

2D and 3D interaction diagram of compound 6b with SARS CoV-2 Mpro binding site.

Molecular Dynamics

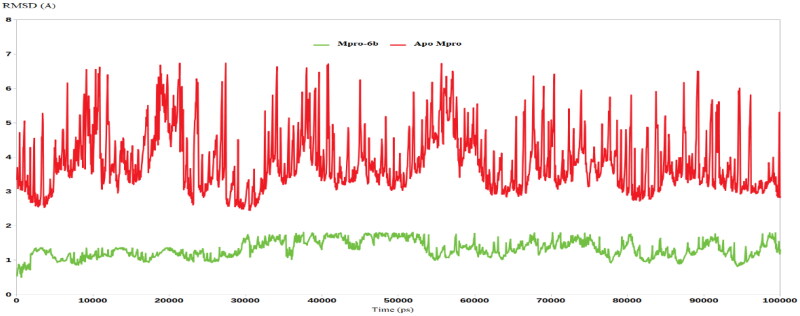

Further virtual investigations were achieved by molecular dynamic (MD) simulations studies. MD simulation provides various useful parameters for studying the dynamics of biological systems. Moreover, MD investigations might provide information about the binding affinity and intensity of docked complexes of a ligand and target proteins. To this end, the binding coordinate revealed by Mpro docking with isatin derivative 6b was advanced to MD simulations. To provide a comparative mean for the effect of the newly synthesised triazolo isatin 6b on the Mpro enzyme, the latter was subjected to MD using its apo form. Therefore, two MD simulations were conducted for 100 ns using GROMACS 5.1.1 software. As shown in Figure 6, triazolo isatin 6b had the privilege of forming a stable complex with the Mpro enzyme, as indicated by its low RMSD values that averagely reached 1.5 Å. On the other hand, the RMSD of the apo Mpro enzyme reached an average value of 4.8 Å, indicating a high degree of flexibility suiting the Mpro intended function to process the viral polypeptide Figure 6. To this extent, the value decrease in the RMSD between the Mpro-6b complex and the apo Mpro highlights the great ability of triazolo isatin 6b to strongly bind and inhibit the SARS CoV-2 Mpro enzyme.

Figure 6.

RMSD analysis for the MD simulations.

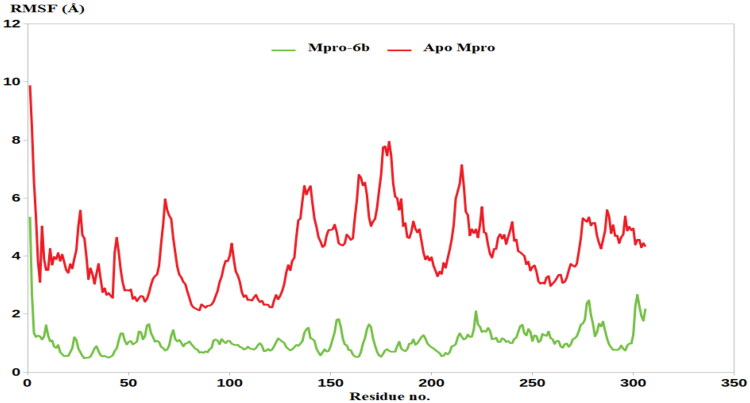

Similar results were obtained from the RMSF analysis in which the residues of the apo protein demonstrated high fluctuations that reached an average of 4.3 Å. In comparison, the binding of compound 6b to the Mpro residues, their stability increased significantly as indicated by average RMSF less than 1.6 Å, Figure 7. To summarise, the MDs results highlight the ability of triazolo isatin 6b to inhibit the SARS CoV-2 Mpro enzyme through forming a stable complex within the Mpro active site, as consistent with the enzyme assay.

Figure 7.

RMSF analysis for the MD simulations.

Conclusion

The preparation of isatin-triazole hybrids was successfully facile through click chemistry allowing the development of novel compounds as Main protease (Mpro) inhibitors. Sulphonamide tethered derivatives showed better activity than the acetophenone derivatives, especially compound 6b which exhibited sub-micromolar enzyme inhibitory activity in FRET assay. Thereafter, triazolo isatin 6b’s antiviral activity was demonstrated by its capacity to inhibit the proliferation of viral cells with an IC50 value of 4.33 µg/ml. Notably, 6b exerted non-significant toxicity towards VERO-E6 cells (CC50 = 564.74 µg/ml) revealing a favourable safety profile with selectivity index equals 130.4. This remarkable observation was supported by molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation which showed the interaction of 6b with several important amino acid residues in the binding site of Mpro and the stability of the formed interactions between the compound and the active site. In particular, the formation of several hydrogen bonds with amino acids involved in the catalytic activity of the enzyme through the alpha-ketoamide moiety and sulphonyl amide function group explains the superior activity of benzenesulfonamide tethered derivatives 6 over acetophenone derivatives 10. Hence, 6b could be further developed as anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent after performing more extensive studies.

Experimental

Chemistry

General

The solvents and reagents used in the reactions were commercially sourced and not purified further. A Stuart melting point device was used to measure melting points that was uncorrected. NMR spectra were attained using a JEOL ECA 500 NMR Spectrometer (500 MHz 1H and 126 MHz 13 C NMR), while elemental analysis (% C, H, and N) was accomplished using a PerkinElmer 2400 CHNS analyser. Reaction progress and product mixtures were regularly monitored through thin layer chromatography (TLC) using Aluminium sheets pre-coated with silica gel 60 F254 purchased from Merk.

Synthesis of intermediates 2-bromo-N-phenylacetamides 2 and 8

To a suspension of 4-aminobenzenesulfonamide 1 or 4′-aminoacetophenone 2 (20 mmol) in dry dioxane (15 ml) and K2CO3 (5.5 g, 40 mmol) at 0 °C, bromoacetyl bromide (4.42 g, 22 mmol) was added dropwise and the mixture was incubated at r.t. with stirring for 12 h. Then, ice-water was added to the reaction mixture, and the precipitate that developed was filtered out. dried and recrystallized from ethanol to produce 2-bromo-N-phenylacetamides 2 and 8 with 75% and 80% yield, respectively49.

Synthesis of intermediates 2-azido-N-phenylacetamides 3 and 9

To a solution of 2-bromo-N-phenylacetamides 2 and 8 (15 mmol) in dry DMF (15 ml), sodium azide (2.9 g, 45 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was incubated at r.t. while stirring for 8 h, and then water (75 ml) was added, and the reaction mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 ml). The organic layer was washed with brine, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, then evaporated under reduced pressure to furnish intermediates 2-azido-N-phenylacetamides 3 and 9 which used in the next step forthwith without further purification50–51. Yield: 73% (3); 70% (9).

Synthesis of N-propargyl isatins 5a-d

A solution of isatin derivatives 4a-d (20 mmol), propargyl bromide (22 mmol), and K2CO3 (5.5 g, 40 mmol) in dry acetonitrile (15 ml) was incubated at r.t. while stirring for 10 h. Afterward, ethyl acetate (3 × 15 ml) was used to extract the reaction mixture after it had been poured into water. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and concentrated at reduced pressure after being washed with brine to yield N-propargyl isatins 5a-d. The yields were 72%, 78%, 70%, and 75% for 5a-d, respectively.

1-(Prop-2-yn-1-yl)isatin (5a)

Yield = 78%, Orange crystals, melting point = 160–162 °C (reported melting point = 158–160 °C)52.

5-Fluoro-1-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)isatin (5b)

Yield = 72%, Red crystals, melting point = 128–130 °C (reported melting point = 124–125 °C)53.

5-Methoxy-1-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)isatin (5c)

Yield = 75%, Red crystals, melting point = 131–133 °C (reported melting point = 130–132 °C)54.

1-(Prop-2-yn-1-yl)-5-(trifluoromethoxy)isatin (5d)

Orange crystals, yield = 70%, melting point = 91–92 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 3.37 (s, 1H, -C≡CH), 4.59 (d, 2H, N-CH2, J = 2.0 Hz), 7.34 (d, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.64 (s, 1H, Aromatic-H), 7.76 (d, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.8 Hz); Anal. Calcd. for C12H6F3NO3: C, 53.54; H, 2.25; N, 5.20; found C, 53.68; H, 2.24; N, 5.17.

General procedure for synthesis of target inhibitors 6a-d and 10a-b

A solution containing 2-azido-N-phenylacetamides 3 and 9 (2 mmol) in 5 ml of a mixture of DMF and H2O (4:1) was prepared. To this solution, N-propargyl isatins 5a-d (2 mmol), CuSO4.5H2O (1 mmol), and sodium ascorbate (2 mmol) were added. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 7 h. After the reaction was complete, the mixture was poured onto crushed ice, filtered, and dried under reduced pressure. The resulting product was crystalised from ethanol to yield the target compounds 6a-d and 10a-b.

2–(4-((2,3-Dioxoindolin-1-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(4-sulfamoylphenyl)acetamide (6a)

Yield (75%); Orange crystals; melting point = 280–282 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δ (ppm): 4.99 (s, 2H, -CH2), 5.33 (s, 2H, -CH2), 7.11 (t, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.18 (d, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.27 (s, 2H, SO2NH2), 7.52 (d, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.62 (t, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 7.0 Hz), 7.69 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.75 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.5 Hz), 8.19 (s, 1H, Aromatic-H), 10.79 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 126 MHz) δ ppm: 35.04, 52.29, 111.25, 117.62, 118.90, 123.45, 124.54, 125.36, 126.90, 138.17, 138.91, 141.26, 141.36, 150.22, 157.88, 164.80, 183.11; Anal. Calcd. for C19H16N6O5S: C, 51.81; H, 3.66; N, 19.08; found C, 52.01; H, 3.64; N, 19.02.

2–(4-((5-Fluoro-2,3-dioxoindolin-1-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(4-sulfamoylphenyl) acetamide (6b)

Yield (75%); Red crystals; melting point = 271–273 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δ (ppm): 4.99 (s, 2H, -CH2), 5.33 (s, 2H, -CH2), 7.20 (dd, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.0, 4.0 Hz), 7.26 (s, 2H, SO2NH2), 7.47–7.53 (m, 2H, Aromatic-H), 7.68 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.75 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 9.0 Hz), 8.18 (s, 1H, Aromatic-H), 10.78 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 126 MHz) δ ppm: 35.11, 52.29, 111.43, 111.62, 112.63, 112.68, 118.54, 118.60, 118.89, 123.92, 124.14, 125.38, 126.89, 138.92, 141.26, 146.43, 157.64, 157.92, 159.55, 164.78, 182.49; Anal. Calcd. for C19H15FN6O5S: C, 49.78; H, 3.30; N, 18.33; found C, 49.93; H, 3.29; N, 18.26.

2–(4-((5-Methoxy-2,3-dioxoindolin-1-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(4-sulfamoylphenyl) acetamide (6c)

Yield (75%); Reddish brown crystals; melting point = 295–297 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δ (ppm): 3.74 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.96 (s, 2H, -CH2), 5.33 (s, 2H, -CH2), 7.11–7.24 (m, 2H, Aromatic-H), 7.26 (s, 2H, SO2NH2), 7.69 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.75–7.77 (m, 3H, Aromatic-H), 8.17 (s, 1H, Aromatic-H), 10.79 (s, 1H, NH); Anal. Calcd. for C20H18N6O6S: C, 51.06; H, 3.86; N, 17.86; found C, 50.86; H, 3.88; N, 17.95.

2–(4-((2,3-Dioxo-5-(trifluoromethoxy)indolin-1-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-N-(4-sulfamoylphenyl)acetamide (6d)

Yield (75%); Light brown crystals; melting point = 283–285 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δ (ppm): 5.01 (s, 2H, -CH2), 5.34 (s, 2H, -CH2), 7.26 (s, 2H, SO2NH2), 7.29 (d, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.61 (s, 1H, Aromatic-H), 7.69–7.71 (m, 3H, Aromatic-H), 7.75 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 9.0 Hz), 8.19 (s, 1H, Aromatic-H), 10.79 (s, 1H, NH); Anal. Calcd. for C20H15F3N6O6S: C, 45.81; H, 2.88; N, 16.03; found C, 45.93; H, 2.87; N, 15.96.

N-(4-Acetylphenyl)-2–(4-((2,3-dioxoindolin-1-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)acetamide (10a)

Yield (71%); Yellow crystals; melting point = 231–233 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.51 (s, 3H, COCH3), 4.99 (s, 2H, -CH2), 5.34 (s, 2H, -CH2), 7.11 (t, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.18 (d, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.55 (d, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.62 (t, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.67 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.92 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 8.5 Hz), 8.19 (s, 1H, Aromatic-H), 10.78 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 126 MHz) δ ppm: 26.48, 35.02, 52.32, 111.23, 117.60, 118.54, 123.42, 124.51, 125.33, 129.62, 132.17, 138.13, 141.35, 142.64, 150.20, 157.86, 164.79, 183.09, 196.58; Anal. Calcd. for C21H17N5O4: C, 62.53; H, 4.25; N, 17.36; found C, 62.38; H, 4.28; N, 17.43.

N-(4-Acetylphenyl)-2–(4-((5-methoxy-2,3-dioxoindolin-1-yl)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)acetamide (10b)

Yield (75%); Yellow crystals; melting point = 245–247 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.51 (s, 3H, COCH3), 3.74 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.96 (s, 2H, -CH2), 5.33 (s, 2H, -CH2), 7.11–7.14 (m, 2H, Aromatic-H), 7.22 (d, 1H, Aromatic-H, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.67 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.92 (d, 2H, Aromatic-H, J = 9.0 Hz), 8.18 (s, 1H, Aromatic-H), 10.79 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 126 MHz) δ ppm: 26.49, 35.01, 52.32, 55.93, 109.23, 112.34, 118.06, 118.55, 119.04, 123.93, 125.31, 129.63, 132.18, 142.65, 144.02, 155.87, 157.90, 162.37, 164.81, 183.37, 196.60; Anal. Calcd. for C22H19N5O5: C, 60.97; H, 4.42; N, 16.16; found C, 61.14; H, 4.42; N, 16.16.

Biological evaluations

Protein expression and purification for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

The DNA sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 Main protease (Mpro) was acquired from the complete genome of SARS-CoV-2 (GenBank MN908947.3). The gene that encodes the protein was optimised for expression in Escherichia coli (E. coil) and synthesised by Bio Basic Inc (Konrad Crescent, Canada). The synthesised gene was inserted into a pET-28a(+) plasmid with a C-terminal His tag. Competent E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells were transformed using this plasmid (New England Biolabs). The transformed cells were grown at a temperature of 37 °C in a medium made of terrific broth (TB) with the addition of 50 µg/mL of the antibiotic Kanamycin and 1% glucose. Protein production was induced after reaching OD600 of 0.6 by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), then the cells were incubated at 16 °C and 180 rpm overnight. The cells were then collected by centrifuging them at 7000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, resuspended in a lysis buffer, and then sonicated to lyse them. Finally, they were centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 40 min at 4 °C to remove the remaining cell debris. The His-tagged protein was purified from the supernatant using affinity TALON Superflow resin (Cytiva, Marlborough, USA) and eluted with an elution buffer containing 50 mM TRIS, 300 mM imidazole, and 150 mM NaCl. SDS-PAGE was used to determine the protein’s degree of purity (see Figure S1), and the pure protein was dialysed and concentrated using a 10K Pierce™ Protein Concentrator (Thermo Scientific).

Enzyme inhibition assay

The enzyme inhibition experiment was conducted in 96-well, black microtiter plates with a total volume of 200 µl. A final concentration of 20 nM of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme was used. The compounds being assessed, along with GC376 as a standard inhibitor, were pre-incubated with the enzyme at different concentrations in an assay buffer consisting of 20 mM TRIS, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and the pH was adjusted to 7.3. A FRET substrate, Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-EDANS, was added to the mixture at final concentration of 10 µM and incubated in the dark for 3 h at room temperature. Fluorescence signals of released EDANS were estimated using a Spectrofluorometer with microplate reader accessory (Cary Eclipse, Agilent Technologies) at (excitation/emission, 355 nm/460 nm), and the blank was determined by measuring the entire reaction mixture without the enzyme. The obtained data was plotted and analysed to determine the IC50 values of the tested compounds using nonlinear regression with a variable slope.

MTT cytotoxicity assay towards VERO-E6 cells

The cytotoxic impact of triazolo isatin derivative 6b was tested in VERO-E6 cells by using the 3–(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method with minor modifications55,56. The procedures were provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Cell-Based SARS-CoV-2 inhibitory assay

The cellular antiviral activity of compound 6b against SARS-CoV-2 was assessed and the IC50 value was determined as descriped previously57–59. The procedures were provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Molecular modelling studies

Molecular docking

Vina Autodock software was used to perform docking studies on compound 6b60. The protein data bank (PDB) was utilised to download the 3D co-ordinates of SARS CoV-2 Mpro bound to an experimental inhibitor (PDB ID: 8ACL)61. The 3D structure of our proposed molecule was created by the Biovia discovery visualiser after it was sketched by ChemDraw. M.G.L 1.5.7 tools were used in the generation of the needed pdbqt format files, since it is mandatory for both receptor and ligands to be in pdbqt format as essential required by Vina Autodock. Moreover, the binding pocket was built using a grid box encompassing the binding of the co-crystalised ligand with dimensions of 22, 22, and 22, respectively, in the three axes. To ensure a valid docking approach, initial docking of the co-crystalised coordinates to the pre-determined binding domain was conducted. Finally, compound 6b was docked into the validated binding domain of SARS CoV-2 Mpro enzyme. The Biovia discovery studio 2021 free visualiser was used to create 2D and 3D interactions for the docked pose to visualise the interaction of 6b with the active site of Mpro.

Molecular Dynamics

Two molecular dynamic simulations (MDS) were conducted for 100 ns exploiting software of GROMACS 5.1.162. The retrieved docking coordinates of the Mpro enzyme in-complex with triazolo isatin 6b and the apo mpro enzyme. The receptor and ligand topologies were generated by PDB2gmx (embedded in GROMACS) and GlycoBioChem PRODRG2 Server respectively, both under GROMOS96 force field63. After rejoining ligands and receptor topologies to generate two systems, the typical molecular dynamics scheme of GROMACS was applied for all the systems. This includes, solvation, neutralisation, energy minimisation under GROMOS96 43a1 force field and two stages of equilibration (NVT and NPT)64–67. Finally, unrestricted production stage of 100 ns was applied for the two systems with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method implemented to compute the long-range electrostatic values using 12 Å cut-off and 12 Å Fourier spacing. The stability of the complexes was judged using RMSD and RMSF values calculated from the MDS trajectories from the production step.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This paper is based upon work supported by Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) under grant number [44025].

Disclosure statement

CT Supuran is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. He was not involved in the assessment, peer review, or decision-making process of this paper. The authors have no relevant affiliations of financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- 1.Cucinotta D, Vanelli M.. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:157–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mori M, Capasso C, Carta F, Donald WA, Supuran CT.. A deadly spillover: SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2020;30(7):481–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC . COVID-19 Treatments and Medications. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/treatments-for-severe-illness.html

- 4.CDC . Interim Clinical Considerations for COVID-19 Treatment in Outpatients. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/outpatient-treatment-overview.html

- 5.Supuran CT. Coronaviruses. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2021;31(4):291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deniz S, Uysal TK, Capasso C, Supuran CT, Ozensoy Guler O.. Is carbonic anhydrase inhibition useful as a complementary therapy of Covid-19 infection? J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2021;36(1):1230–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macip G, Garcia-Segura P, Mestres-Truyol J, Saldivar-Espinoza B, Pujadas G, Garcia-Vallvé S.. A review of the current landscape of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: have we hit the bullseye yet? IJMS. 2021;23(1):259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan S, Wu G.. Spatial and temporal roles of SARS-CoV PLpro—A snapshot. Faseb J. 2021;35(1):e21197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin Z, Du X, Xu Y, Deng Y, Liu M, Zhao Y, Zhang B, Li X, Zhang L, Peng C, et al. . Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582(7811):289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong N, Zhang S, Zou P, Chen J, Kang X, Li Z, Liang C, Jin C, Xia B.. Without its N-finger, the main protease of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus can form a novel dimer through its C-terminal domain. J Virol. 2008;82(9):4227–4234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Capasso C, Nocentini A, Supuran CT. Protease inhibitors targeting the main protease and papain-like protease of coronaviruses. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2022;17(6):547–557. b) Nocentini A, Capasso C, Supuran CT.. Perspectives on the design and discovery of α-ketoamide inhibitors for the treatment of novel coronavirus: where do we stand and where do we go? Expert Opin Drug Discov. 202;(6) 547–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Ma C, Sacco MD, Hurst B, Townsend JA, Hu Y, Szeto T, Zhang X, et al. . Boceprevir, GC-376, and calpain inhibitors II, XII inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral replication by targeting the viral main protease. Cell Res. 2020;30(8):678–692. b) Vuong W, Khan MB, Fischer C, Arutyunova E, Lamer T, Shields J, Saffran HA, et al. . Feline coronavirus drug inhibits the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 and blocks virus replication. Nat Commun. 11(1)2020;4282. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Joyce RP, Hu VW and Wang J.. The history, mechanism, and perspectives of nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332): an orally bioavailable main protease inhibitor used in combination with ritonavir to reduce COVID-19-related hospitalizations. Med Chem Res. 2022;31(10):1637–1646. b) Singh J, Petter RC, Baillie TA, Whitty A.. The resurgence of covalent drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2011;10: 307–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer RA. Covalent inhibitors in drug discovery: from accidental discoveries to avoided liabilities and designed therapies. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20(9):1061–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandao P, Marques C, Burke AJ, Pineiro M.. The application of isatin-based multicomponent-reactions in the quest for new bioactive and druglike molecules. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;211:113102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eldehna WM, El Hassab MA, Abo-Ashour MF, Al-Warhi T, Elaasser MM, Safwat NA, Suliman H, Ahmed MF, Al-Rashood ST, Abdel-Aziz HA, et al. . Development of isatin-thiazolo [3, 2-a] benzimidazole hybrids as novel CDK2 inhibitors with potent in vitro apoptotic anti-proliferative activity: synthesis, biological and molecular dynamics investigations. Bioorg Chem. 2021;110:104748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eldehna WM, Al-Wabli RI, Almutairi MS, Keeton AB, Piazza GA, Abdel-Aziz HA, Attia MI.. Synthesis and biological evaluation of certain hydrazonoindolin-2-one derivatives as new potent anti-proliferative agents. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2018;33(1):867–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Taghour MS, Elkady H, Eldehna WM, El-Deeb NM, Kenawy AM, Elkaeed EB, Alsfouk AA, Alesawy MS, Metwaly AM, and Eissa IH. Design and synthesis of thiazolidine-2, 4-diones hybrids with 1, 2-dihydroquinolones and 2-oxindoles as potential VEGFR-2 inhibitors: in-vitro anticancer evaluation and in-silico studies. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2022;37(1):1903–1917. b) Eldehna WM, Fares M, Ibrahim HS, Alsherbiny MA, Aly MH, Ghabbour HA, Abdel-Aziz HA.. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity of biphenylurea derivatives containing indolin-2-one moieties. " Molecules. 2016;21(6);762. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Warhi T, Abo-Ashour MF, Almahli H, Alotaibi OJ, Al-Sanea MM, Al-Ansary GH, Ahmed HY, Elaasser MM, Eldehna WM, Abdel-Aziz HA.. Novel [(N-alkyl-3-indolylmethylene) hydrazono] oxindoles arrest cell cycle and induce cell apoptosis by inhibiting CDK2 and Bcl-2: synthesis, biological evaluation and in silico studies. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2020;35(1):1300–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo H. Isatin derivatives and their anti-bacterial activities. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;164:678–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Warhi T, Elimam DM, Elsayed ZM, Abdel-Aziz MM, Maklad RM, Al-Karmalawy AA, Afarinkia K, Abourehab MA, Abdel-Aziz HA, Eldehna WM.. Development of novel isatin thiazolyl-pyrazoline hybrids as promising antimicrobials in MDR pathogens. RSC Adv. 2022;12(48):31466–31477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Xu Z, Zhang S, Gao C, Fan J, Zhao F, Lv Z-S, Feng L-S. Isatin hybrids and their anti-tuberculosis activity. Chin Chem Lett. 2017;28(2):159–167. b) Abdel-Aziz HA, Ghabbour HA, Eldehna WM, Qabeel MM, Fun H-K.. Synthesis, crystal structure, and biological activity of cis/trans amide rotomers of (Z)-N′-(2-Oxoindolin-3-ylidene) formohydrazide. J Chem. 2014;2014: 760434. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdelrahman MA, Almahli H, Al-Warhi T, Majrashi TA, Abdel-Aziz MM, Eldehna WM, Said MA.. Development of novel isatin-tethered quinolines as anti-tubercular agents against multi and extensively drug-resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecules. 2022;27(24):8807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elsayed ZM, Eldehna WM, Abdel-Aziz MM, El Hassab MA, Elkaeed EB, Al-Warhi T, Abdel-Aziz HA, Abou-Seri SM, Mohammed ER.. Development of novel isatin–nicotinohydrazide hybrids with potent activity against susceptible/resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and bronchitis causing–bacteria. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2021;36(1):384–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiyanzu I, Clarkson C, Smith PJ, Lehman J, Gut J, Rosenthal PJ, Chibale K.. Design, synthesis and anti-plasmodial evaluation in vitro of new 4-aminoquinoline isatin derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13(9):3249–3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thakur RK, Joshi P, Baranwal P, Sharma G, Shukla SK, Tripathi R, Tripathi RP.. Synthesis and antiplasmodial activity of glyco-conjugate hybrids of phenylhydrazono-indolinones and glycosylated 1, 2, 3-triazolyl-methyl-indoline-2, 3-diones. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;155:764–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khatoon S, Aroosh A, Islam A, Kalsoom S, Ahmad F, Hameed S, Abbasi SW, Yasinzai M, Naseer MM.. Novel coumarin-isatin hybrids as potent antileishmanial agents: synthesis, in silico and in vitro evaluations. Bioorg Chem. 2021;110:104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabt A, Eldehna WM, Ibrahim TM, Bekhit AA, Batran RZ.. New antileishmanial quinoline linked isatin derivatives targeting DHFR-TS and PTR1: design, synthesis, and molecular modeling studies. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;246:114959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elsaman T, Mohamed MS, Mohamed Eltayib E, Abdel-Aziz HA, Abdalla AE, Munir MU, Mohamed MA.. Isatin derivatives as broad-spectrum antiviral agents: the current landscape. Med Chem Res. 2022;31(2):244–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandeya SN, Yogeeswari P, Sriram D, De Clercq E, Pannecouque C, Witvrouw M.. Synthesis and screening for anti-HIV activity of some N-Mannich bases of isatin derivatives. Chemotherapy. 1999;45(3):192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banerjee D, Yogeeswari P, Bhat P, Thomas A, Srividya M, Sriram D.. Novel isatinyl thiosemicarbazones derivatives as potential molecule to combat HIV-TB co-infection. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46(1):106–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bal TR, Anand B, Yogeeswari P, Sriram D.. Synthesis and evaluation of anti-HIV activity of isatin β-thiosemicarbazone derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15(20):4451–4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Moraes Gomes PAT, Pena LJ, Leite ACL.. Isatin derivatives and their antiviral properties against arboviruses: a review. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2019;19(1):56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mishra P, Kumar A, Mamidi P, Kumar S, Basantray I, Saswat T, Das I, Nayak TK, Chattopadhyay S, Subudhi BB, et al. . Inhibition of Chikungunya virus replication by 1-[(2-Methylbenzimidazol-1-yl) Methyl]-2-Oxo-Indolin-3-ylidene]Amino] Thiourea(MBZM-N-IBT). Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang I-J, Wang L-W, Hsu T-A, Yueh A, Lee C-C, Lee Y-C, Lee C-Y, Chao Y-S, Shih S-R, Chern J-H, et al. . Isatin-β-thiosemicarbazones as potent herpes simplex virus inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21(7):1948–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang HM, Dai H, Hanson PJ, Li H, Guo H, Ye X, Hemida MG, Wang L, Tong Y, Qiu Y, et al. . Antiviral activity of an isatin derivative via induction of PERKNrf2-mediated suppression of cap-independent translation. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9(4):1015–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pirrung MC, Pansare SV, Das Sarma K, Keith KA, Kern ER.. Combinatorial optimization of isatin-β-thiosemicarbazones as anti-poxvirus agents. J Med Chem. 2005;48(8):3045–3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selvam P, Murugesh N, Chandramohan M, Sidwell RW, Wandersee MK, Smee DF.. Anti-influenza virus activities of 4-[(1,2-dihydro-2-oxo-3H-indol-3- ylidene)amino]-N-(4,6-dimethyl-2-pyrimidin-2-yl)benzenesulphonamide and its derivatives. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2006;17(5):269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu W, Zhu H-M, Niu G-J, Shi E-Z, Chen J, Sun B, Chen W-Q, Zhou H-G, Yang C.. Synthesis, modification and docking studies of 5-sulfonyl isatin derivatives as SARS-CoV 3C-like protease inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22(1):292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selvam P, Murgesh N, Chandramohan M, De Clercq E, Keyaerts E, Vijgen L, Maes P, Neyts J, Ranst MV.. In vitro antiviral activity of some novel isatin derivatives against HCV and SARS-CoV viruses. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70(1):91–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L-R, Wang Y-C, Lin YW, Chou S-Y, Chen S-F, Liu LT, Wu Y-T, Kuo C-J, Shieh-Shung Chen T, Juang S-H.. Synthesis and evaluation of isatin derivatives as effective SARS coronavirus 3CL protease inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15(12):3058–3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou L, Liu Y, Zhang W, Wei P, Huang C, Pei J, Yuan Y, Lai L.. Isatin compounds as noncovalent SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2006;49(12):3440–3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu P, Liu H, Sun Q, Liang H, Li C, Deng X, Liu Y, Lai L.. Potent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease derived from N-substituted isatin compounds. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;206:112702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ElNaggar MH, Abdelwahab GM, Kutkat O, GabAllah M, Ali MA, El-Metwally ME, Sayed AM, Abdelmohsen UR, Khalil AT.. Aurasperone A inhibits SARS CoV-2 in vitro: an integrated in vitro and in silico study. Mar Drugs. 2022;20(3):179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elsbaey M, Ibrahim MAA, Bar FA, Elgazar AA.. Chemical constituents from coconut waste and their in-silico evaluation as potential antiviral agents against SARS-CoV-2. S Afr J Bot. 2021;141:278–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elimam DM, Elgazar AA, El-Senduny FF, El-Domany RA, Badria FA, Eldehna WM.. Natural inspired piperine-based ureas and amides as novel antitumor agents towards breast cancer. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2022;37(1):39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Sanea MM, Hamdi A, Mohamed AAB, El-Shafey HW, Moustafa M, Elgazar AA, Eldehna WM, Ur Rahman H, Parambi DGT, Elbargisy RM, et al. . New benzothiazole hybrids as potential VEGFR-2 inhibitors: design, synthesis, anticancer evaluation, and in silico study. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2023;38(1):2166036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Othman DI, Hamdi A, Tawfik SS, Elgazar AA, Mostafa AS.. Identification of new benzimidazole-triazole hybrids as anticancer agents: multi-target recognition, in vitro and in silico studies. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2023;38(1):2166037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elbadawi MM, Eldehna WM, Nocentini A, Abo-Ashour MF, Elkaeed EB, Abdelgawad MA, Alharbi KS, Abdel-Aziz HA, Supuran CT, Gratteri P, et al. . Identification of N-phenyl-2-(phenylsulfonyl) acetamides/propanamides as new SLC-0111 analogues: synthesis and evaluation of the carbonic anhydrase inhibitory activities. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;218:113360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.An R, Lin B, Zhao S, Cao C, Wang Y, Cheng X, Liu Y, Guo M, Xu H, Wang Y, et al. . Discovery of novel artemisinin-sulfonamide hybrids as potential carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors with improved antiproliferative activities. Bioorg Chem. 2020;104:104347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El‐Sayed HA, Moustafa AH, Masry AA, Amer AM, Mohammed SM.. An efficient synthesis of 4, 6‐diarylnicotinonitrile‐acetamide hybrids via 1, 2, 3‐triazole linker as multitarget microbial inhibitors. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2022;59(2):275–285. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Firoozpour L, Gao L, Moghimi S, Pasalar P, Davoodi J, Wang M-W, Rezaei Z, Dadgar A, Yahyavi H, Amanlou M, et al. . Efficient synthesis, biological evaluation, and docking study of Isatin based derivatives as caspase inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2020;35(1):1674–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tri NM, Thanh ND, Ha LN, Anh DTT, Toan VN, Giang NTK.. Study on synthesis of some substituted N-propargyl isatins by propargylation reaction of corresponding isatins using potassium carbonate as base under ultrasound-and microwave-assisted conditions. Chem Pap. 2021;75(9):4793–4801. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Day J, Uroos M, Castledine RA, Lewis W, McKeever-Abbas B, Dowden J.. Alkaloid inspired spirocyclic oxindoles from 1, 3-dipolar cycloaddition of pyridinium ylides. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11(38):6502–6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferatio and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1-2) :55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abd-Alla HI, Kutkat O, Sweelam H-t. M, Eldehna WM, Mostafa MA, Ibrahim MT, Moatasim Y, GabAllah M, Al-Karmalawy AA.. Investigating the potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 and anti-MERS-CoV activities of yellow necklacepod among three selected medicinal plants: extraction, Isolation, identification, in vitro, modes of action, and molecular docking studies. Metabolites. 2022;12(11):1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al-Karmalawy AA, El-Gamil DS, El-Shesheny R, Sharaky M, Alnajjar R, Kutkat O, Moatasim Y, Elagawany M, Al-Rashood ST, Binjubair FA, et al. . Design and statistical optimisation of emulsomal nanoparticles for improved anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of N-(5-nitrothiazol-2-yl)-carboxamido candidates: in vitro and in silico studies. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2023;38(1):2202357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elebeedy D, Elkhatib WF, Kandeil A, Ghanem A, Kutkat O, Alnajjar R, Saleh MA, Maksoud AIAE, Badawy I, Al-Karmalawy AA.. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities of tanshinone IIA, carnosic acid, rosmarinic acid, salvianolic acid, baicalein, and glycyrrhetinic acid between computational and in vitro insights. RSC Adv. 2021;11(47):29267–29286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abo Elmaaty A, Eldehna W, Khattab M, Kutkat O, Alnajjar R, El-Taweel A, Al-Rashood S, Abourehab M, Binjubair F, Saleh M, et al. . Anticoagulants as potential SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors for COVID-19 Patients: in vitro, molecular docking, molecular dynamics, DFT, and SAR studies. IJMS. 2022;23(20):12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trott O, Olson AJ.. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gao S, Sylvester K, Song L, Claff T, Jing L, Woodson M, Weiße RH, Cheng Y, Schäkel L, Petry M, et al. . Discovery and crystallographic studies of trisubstituted piperazine derivatives as non-covalent SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors with high target specificity and low toxicity. J Med Chem. 2022;65(19):13343–13364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, Lindahl E.. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1-2:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schüttelkopf AW, van Aalten DMF.. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 8):1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hassab MAE, Fares M, Amin MKA-H, Al-Rashood ST, Alharbi A, Eskandrani RO, Alkahtani HM, Eldehna WM.. Toward the identification of potential α-ketoamide covalent inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 main protease: fragment-based drug design and MM-PBSA calculations. Processes. 2021;9(6):1004. [Google Scholar]

- 65.El Hassab MA, Shoun AA, Al-Rashood ST, Al-Warhi T, Eldehna WM.. Identification of a new potential SARS-COV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor via combining fragment-based drug design, docking, molecular dynamics, and MM-PBSA calculations. Front Chem. 2020;8:915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.El Hassab MA, Ibrahim TM, Al-Rashood ST, Alharbi A, Eskandrani RO, Eldehna WM.. In silico identification of novel SARS-COV-2 2'-O-methyltransferase (nsp16) inhibitors: structure-based virtual screening, molecular dynamics simulation and MM-PBSA approaches. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2021;36(1):727–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El Hassab MA, Ibrahim TM, Shoun AA, Al-Rashood ST, Alkahtani HM, Alharbi A, Eskandrani RO, Eldehna WM.. In silico identification of potential SARS COV-2 2′-O-methyltransferase inhibitor: fragment-based screening approach and MM-PBSA calculations. RSC Adv. 2021;11(26):16026–16033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.