Abstract

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) is well known for its role producing the vasoconstrictor angiotensin II and ACE inhibitors are commonly used for treating hypertension and cardiovascular disease. However, ACE has many different substrates besides angiotensin I and plays a role in many different physiologic processes. Here, we discuss the role of ACE in the immune response. Several studies in mice indicate that increased expression of ACE by macrophages or neutrophils enhances the ability of these cells to respond to immune challenges such as infection, neoplasm, Alzheimer’s disease and atherosclerosis. Increased expression of ACE induces increased oxidative metabolism with an increase in cell content of ATP. In contrast, ACE inhibitors have the opposite effect, and in both humans and mice, administration of ACE inhibitors reduces the ability of neutrophils to kill bacteria. Understanding how ACE affects the immune response may provide a means to increase immunity in a variety of chronic conditions now not treated through immune manipulation.

1. Introduction.

Among all peptides that have been characterized, angiotensin II is one of the most intensively studied. While the sequence of this peptide was delineated in the 1950s, each additional decade has brought an increased depth of understanding of how angiotensinogen, renin, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) coordinate to produce angiotensin II and how this peptide, after binding to cell surface receptors, has a plethora of functions encompassing blood pressure control and cardiovascular regulation.1,2,3 To this author, the greatest unsolved question is an exact elucidation of how angiotensin II, binding to the AT1 receptor in a variety of tissues and signaling through approximately equivalent pathways, has so many different effects.

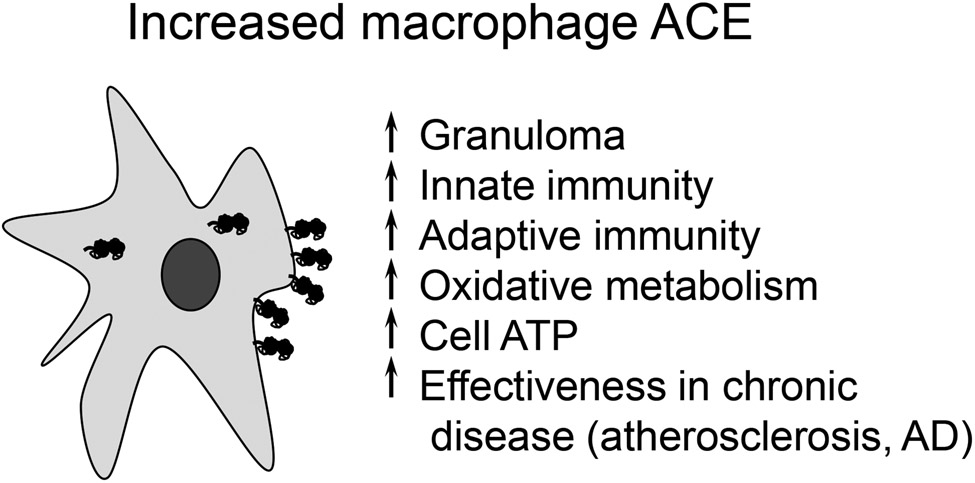

In studying the renin-angiotensin system, our group has found the biology of ACE particularly attractive. ACE is made by many different tissues and has dozens if not hundreds of peptide substrates that serve to differentiate its physiologic function from that of angiotensin II.4 In considering the physiologic roles of ACE, angiotensin II and its many cardiovascular effects is the sun in the sky: it is so important and is so central to physiology that its brightness outshines the moon-like non-cardiovascular effects of ACE, and it takes a keen eye to fully recognize that ACE indeed plays important roles in addition to blood pressure control. Here, we discuss some of these actions with an emphasis on the role of ACE in immunity (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

While ACE is recognized for participating in blood pressure regulation, it also has several other physiologic effects. This is very evident in the ACE 10/10 mouse in which there is increased ACE expression by monocytes and macrophages. ACE is composed of two catalytic domains and is found on the surface of cells. In macrophages, ACE has many functions that affect cell metabolism and myeloid cell immune response. With increased ACE expression, the enzyme has intracellular functions including the trimming of MHC class I and class II peptides before their presentation by cells.

2. ACE and the immune response.

It was first reported in 1975 that patients with active sarcoidosis have elevated serum ACE levels.5 We now know that human lesional macrophages and myeloid derived giant cells in virtually all human granulomatous diseases (histoplasmosis, leprosy, miliary TB, Wegener’s granulomatosis, etc) express abundant ACE.6,7,8,9 Macrophage ACE up-regulation is even found in zebra fish granuloma.10 Extensive study of material from human atherosclerotic lesions shows that the macrophages identified in both early and late stage lesions also make abundant ACE.11,12 ACE increases when the human monocytic cell line THP1 is differentiated into macrophages.11 When human peripheral blood monocytes differentiate to macrophages, cell ACE activity increases 9-fold.13 All of these observations raise the question of why ACE is made by activated macrophages. While the answer to this question is only now being uncovered, what is certain is increased ACE expression by one of the central cells in the immune response has nothing to do with blood pressure.

3. ACE and the adaptive immune response.

Our analysis of the role of ACE in immunity began with the construction of a mouse termed ACE 10/10 in which embryonic stem cell targeting was used to insert the c-fms promoter immediately 5' of the coding region of the natural ACE gene.14 ACE 10/10 are homozygous for the mutation. Because of this, the tissue specificity of the natural ACE promoter was replaced by the specificity of the c-fms promoter resulting in ACE 10/10 mice having high levels of ACE expression by monocytes and macrophages. Depending on how/when ACE is measured, ACE 10/10 macrophages express from 16-fold to 25-fold normal levels of ACE.14 Other myelomonocytic cells, such as neutrophils and dendritic cells, also over-express ACE, but at only 4% and 17% of macrophage levels. ACE expression by T and B cells is very low, similar to WT. In contrast, ACE 10/10 mice lack ACE expression by endothelial cells, renal epithelial cells and other tissues which do not recognize the c-fms promoter. Despite this change in ACE expression, ACE 10/10 mice have normal body and organ weights, serum ACE levels, blood pressure, renal function, peripheral blood, and bone marrow characteristics. ACE 10/10 mice live normal life spans and have no evidence of auto-immune disease.

ACE 10/10 mice were studied following subcutaneous injection of mouse B16-F10 melanoma cells. This is an aggressive mouse tumor and the implantation of 106 cells results in a visible tumor at the end of two weeks. ACE 10/10 mice were much more resistant to the growth of melanoma; at the end of two weeks, tumors in WT mice averaged 540 mm3 while ACE 10/10 mice averaged only 90 mm3. Histologic examination of the small tumors in ACE 10/10 mice confirmed many more inflammatory cells (myeloid and lymphoid derived cells) within the tumor blood vessels and tumor itself.14 The increased resistance to tumor growth in this model is dependent on the action of CD8+ T cells, emphasizing the interaction of myeloid and lymphoid cells in this example of adaptive immunity. Indeed, following challenge with B16 tumor cells expressing ovalbumin (in this case acting as a tumor maker), analysis showed that ACE 10/10 have more circulating CD8+ T cells sensitive to SIINFEKL (the major ovalbumin immune epitope for T cells in C57BL/6 mice) and to the B16 tumor epitope TRP-2 than similarly treated WT mice.14 That this is due to bone marrow derived cells was established by transplanting WT mice with bone marrow from ACE 10/10 or WT mice. In this experiment, ACE expression by all tissues excepting bone marrow were at WT levels. Nonetheless, mice with ACE 10/10 bone marrow had consistently smaller tumors following B16 challenge. In ACE 10/10 mice, increased resistance to tumor was eliminated by treating the animals for 1 week with an ACE inhibitor (ACEi) but not with the angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) losartan. In fact, ACE 10/10 mice genetically lacking angiotensinogen retain an increased immune response.14 Thus, the increased immune response is not due to any angiotensin peptide.

4. Antigen presentation.

Changing the behavior of myeloid cells has ripple effects throughout the immune response. For example, following mouse immunization with ovalbumin (OVA), anti-OVA antibody levels in ACE 10/10 mice were >20-fold those in WT.15 Whether one considers antibody production or the sensitization of killer T cells, a critical function of phagocytic cells is the presentation of peptides by class I or class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins.16,17 Much is known about this process but a critical feature is intracellular trimming of peptides before their presentation on the cell surface of phagocytic cells.18,19,20 This applies to antigens from either the extracellular environment (cross-presentation) or antigens produced endogenously. Several different studies now indicate that ACE can play a role in this process through the intracellular cleavage of the C-terminus of peptides destined for presentation.21,22 This includes both self-peptides (such as the HY peptide Uty encoded on the Y chromosome) as well as foreign antigens such as those from polyoma virus or ovalbumin. Increased ACE expression levels in macrophages increases their ability to stimulate OVA-sensitive CD4+ T cells ex vivo.15 ACE also affected the in vivo presentation of MHC class I and class II epitopes, increasing some epitopes while decreasing others.22 As to whether this ability to shape the presented peptide repertoire is central to the increased immune function of ACE 10/10 cells, or just one of several changes that affect immune function has not yet been determined.

5. Human studies of ACE and tumors.

If ACE plays a role in the adaptive immune response, an obvious question is whether there is evidence of this in humans. Here, we must restate the obvious: that clinical studies in humans are much more complicated than in mice given the wide diversity of humans and the many different clinical situations in which ACEi are prescribed. Nonetheless, there is a lively debate in the literature concerning whether ACEi are associated with increased risk of cancer and in particular lung cancer.23 Hicks et al. studied 992,061 patients from the United Kingdom to determine the relative effect of ACEi vs ARBs on the incidence of lung cancer.24 They concluded that there was an increased risk of lung cancer with an association noted after 5 yrs of use and with hazard ratios that gradually increased with longer durations of use. This was disputed by a meta analysis of Korean patients by Lee et al. who found no difference between patients taking ACEi vs ARBs.25

6. ACE and the innate immune response.

In considering ACE 10/10 mice, the enhanced immune response is not limited to just tumors. Several studies have examined acute infection with either L. monocytogenes (listeria) or methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) as a means of assessing innate immunity.26 For both, as with melanoma, the immune response of ACE 10/10 mice was substantially increased. For example, 4 days after subcutaneous challenge with MRSA (strain SF8300), the skin lesions in ACE 10/10 mice were much smaller (ACE 10/10: 13 mm2; WT: 60 mm2) and contained roughly 50-fold fewer viable bacteria as compared to lesions in WT.26 These results are particularly significant because mice are far more resistant to MRSA than humans. Nonetheless, despite effective innate immunity in WT mice, the immune response of ACE 10/10 was markedly better, indicating a much more vigorous immune response than that possibly achievable by WT mice.

Neutrophils and monocytes are derived from a common precursor and share many features. This led us to investigate the natural role of ACE in neutrophil function. Initial experiments studied the subcutaneous injection of MRSA into WT and ACE KO mice.27 After three days, ACE KO mice had significantly larger skin lesions (4-fold) and more bacteria per lesion (3.3-fold) compared to WT animals.

Because of the low blood pressure in ACE KO mice, WT mice were transplanted with bone marrow (BM) from either WT mice or from ACE KO mice. 8 weeks later, the mice were challenged with subcutaneous MRSA. The WT mice transplanted with ACE KO BM had increased skin lesional area (4.9-fold) and lesional bacterial counts (3.5-fold) as compared to transplantation of WT BM.27 Further, ACE KO neutrophils, as well as neutrophils from a WT mouse treated with an ACEi killed significantly less bacteria in vitro and in vivo than WT cells.27,28 This was vividly illustrated using a mouse model of MRSA-induce infectious endocarditis: in cohorts of 10 mice, 100% of ACE KO mice demonstrated vegetative bacterial growth compared to 40% of WT mice, and 10% of NeuACE animals. When NeuACE mice were treated with an ACEi, 80% of animals showed vegetative cardiac valve growth.28

To study neutrophils with increased ACE, we made a new line of mice by transgenic insertion of a construct consisting of the c-fms promoter driving ACE cDNA. Several founders were studied until one was identified in which ACE expression was increased 12- to 18-fold only in neutrophils; in these mice called NeuACE, macrophage ACE expression is similar to WT mice.27 Compared to ACE 10/10, NeuACE mice are 1) a different line of mice, 2) animals in which the endogenous ACE gene is unchanged, and 3) all tissues except neutrophils make normal levels of ACE. By increasing ACE in neutrophils, we test if ACE over expression will affect this different population of myeloid cells. When NeuACE mice were studied by infection with either MRSA, K. pneumoniae, or P. aeruginosa; the resistance of the NeuACE mice was consistently much better than WT animals. This difference was due to neutrophils since the depletion of these cells with anti-PMN antibody eliminated the difference between NeuACE and WT mice.27 It was also dependent on ACE activity since an ACEi increased lesion size eliminating the difference between WT and NeuACE. No such effect was noted with either losartan or the renin inhibitor aliskiren, strongly indicating that angiotensin II is not the cause of this phenotype. Thus, in this different line of mice in which ACE expression is increased in a different type of myeloid cell, animals show increased bacterial resistance similar to ACE 10/10. This finding and analysis of other transgenic mouse lines expressing increase myeloid ACE that were created in our laboratory, established beyond doubt that the remarkable phenotype observed in ACE 10/10 is not idiosyncratic to this mouse line.18,29

Neutrophils kill bacteria by several different means, but central is the generation of superoxide by NADPH oxidase. Increased ACE expression in NeuACE neutrophils increases NADPH oxidase and superoxide.27 This results in more effective killing of bacteria. ACE 10/10 macrophages also make significantly more superoxide than WT cells.27 Analysis of ACE KO, WT, and NeuACE mice showed a direct relationship between ACE expression and production of the potent chemoattractant LTB4.28

7. Human studies of ACE and innate immunity.

Seven volunteers were tested in an IRB approved protocol in which they took the ACE inhibitor ramipril, 2.5 mg twice per day, for one week.28 This is a typical dose for heart failure or hypertension. Blood was collected before the drug, after 1 week of drug exposure, and then after an additional washout week. Whole blood was tested for bacterial killing of MRSA, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa by measuring bacterial survival 2 hr and 5 hr after addition of bacteria to blood. Blood neutrophils were also highly purified and tested at 2 hr and 5 hr for 1) intracellular killing of the three bacteria, 2) LPS stimulated intracellular ROS production, and 3) cell production of superoxide in response to LPS. These data showed a consistent reduction of neutrophil function due to ramipril. For example, linear regression analysis of all whole blood killing data (all subjects, time points, and bacteria) indicated a significant reduction of killing caused by ramipril with a p<0.0001. This assay is dependent on neutrophil function. Ramipril significantly reduced intracellular bacterial killing, superoxide production, and cell total ROS production. These human data were nearly identical to a similar study in mice implying a very similar biology of ACE and myeloid function in these two species.28

8. Chronic disease

While one might imagine an effect of ACE on myeloid killing of bacteria, a surprising finding is the effect of increased ACE expression, as seen in ACE 10/10 mice, on the response to chronic diseases including atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease.30,31,32 There are well-established mouse models that mimic the pathology and the biology of these human afflictions.33,34 Such mice were mated with ACE 10/10 resulting in offspring modeling the disease process but now having either WT levels or increased levels of ACE expression by bone marrow derived monocytes and macrophages. In both the mouse model of atherosclerosis and the model of Alzheimer’s disease, animals expressing increased levels of macrophage ACE had a much better disease outcome with significantly less pathologic evidence of atherosclerosis or Alzheimer’s disease brain plaques. Thus, these studies emphasize that macrophage function is not only central to processes such as tumors or infections but also to the response to chronic injury observed in these models. Put another way, modern investigation has suggested that the inflammatory response present in human patients with atherosclerosis or Alzheimer’s disease is not only ineffective in resolving the clinical problem but probably contributes to the pathology of disease.35 Apparently, enhancement of the immune response as observed in the ACE 10/10 mice, is highly beneficial even in reducing the pathology of some chronic diseases.

9. ACE affects myeloid cell metabolism.

A critical question is how does increased ACE expression affect and indeed facilitate the immune response. While this is still not fully resolved, the recent finding that ACE expression levels affect myeloid cell metabolism represents a breakthrough in our understanding of the phenomenon.36 Recent advances in mass spectrometry techniques allow these machines to produce a detailed metabolic map in which cell levels of dozens of intermediate metabolites are accurately determined, producing a fingerprint of a cell’s metabolism. Such studies of thioglycollate induced peritoneal ACE 10/10 macrophages, bone marrow derived NeuACE neutrophils and equivalent WT cells showed that ACE markedly increased cell concentration of many metabolites in both myeloid populations. For example, ACE 10/10 macrophages showed 27 significant differences from WT cells with 26 metabolites increased in ACE 10/10. Most surprising, ATP levels per cell were consistently and significantly increased in both cell types over expressing ACE (3.0-fold and 1.9-fold in macrophages and neutrophils).35 These remarkable data were verified by chemically measuring cellular ATP which showed an increase of 2.4 and 1.7-fold in ACE 10/10 and NeuACE cells. In contrast, ACE KO macrophages have lower ATP levels than WT. The increase in cellular ATP was due to ACE catalytic activity as it was reduced to WT levels by treating mice with the ACE inhibitor ramipril but not by the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan. These differences were not due to differences in cell size/number or mitochondrial size/number, as these parameters were equivalent to WT in cells expressing increased ACE.35

Mass spectrometry was also used to study Krebs cycle metabolic intermediates. This showed that ACE 10/10 macrophages have significantly higher levels of citrate (3.9-fold), isocitrate (5.2-fold), succinate (1.9-fold), and malate (2.0-fold).35 Similar results were found in NeuACE neutrophils vs. WT though the differences were less pronounced, perhaps because neutrophils are more dependent on glycolysis for energy .

It is also possible to assess oxidative metabolism by using the Seahorse machine to detect O2 uptake.35 This showed significant differences between ACE 10/10 and WT macrophages. For example, maximal oxygen consumption was 37% higher in ACE 10/10 than in WT macrophages. Additional experiments were performed with macrophages fed either glucose, pyruvate/malate, glutamate/malate or succinate/rotenone. In all instances, oxidative metabolism (oxygen consumption) in ACE 10/10 macrophages was higher than WT (for example, 31% higher than WT cells with glucose feeding).

Mitochondrial production of ATP is driven by the difference in membrane potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Perhaps not surprising, ACE 10/10 mice had a 24% increase in mitochondrial potential while cells from ACE KO mice had a 30% decrease as compared to WT cells.35

Mitochondrial membrane potential and production of ATP are ultimately due to the efficiency of the electron transport chain. Western blot analysis of ACE 10/10 macrophages, NeuACE neutrophils, and WT cells with antibodies directed against proteins present in each of the five electron transport complexes showed that, in cells with elevated ACE expression, there was a significant increase in the protein from electron transport complex I and complex V as compared to WT cells.35 ACE 10/10 macrophages also had an increase of COX1 (MTCO1) from electron transport complex IV . These data were confirmed by mass spectrometry. An increase of electron chain proteins is consistent with the increased respiratory rate found in the ACE 10/10 macrophages.

10. Testis ACE.

One of the earliest non-cardiovascular effects of ACE recognized was that due to the isoform of ACE made by developing male germ cells.37 Termed testis ACE (or alternatively germinal ACE), the production of large amounts of this enzyme by cells that have nothing to do with cardiovascular function clearly implicated a physiologic role different from blood pressure control. Indeed, the original descriptions of mice genetically lacking ACE included reproductive studies of these mice.38,39 Simply put, male ACE knockout (KO) mice reproduce very poorly.40 Detailed in vitro study documented a major difference in the ability of sperm from a wild-type (WT) mouse vs. an ACE KO mouse to bind to hamster ova.41 Other analyses described a defect in the ability of sperm from ACE KO males to ascend the female reproductive tract.40 While many biochemical details remain to be elucidated, genetic analysis suggested that a lack of angiotensin II function was not the explanation for the ACE KO phenotype and thus suggested that some other peptide besides angiotensin II must explain the natural function of testis ACE.40

11. Conclusion

If the effects of ACE and angiotensin II on cardiovascular function is the sun, then the role of ACE in regulating myeloid cell immune function is clearly one of the moons. While the finding that ACE levels are high in patients with active sarcoidosis was first noted in 1975, it has recently become crystal clear that such expression is not frivolous or inconsequential or merely a result of cell activation. In fact, several aspects of myeloid cell function vary directly with the increase or decrease of ACE activity. One example is myeloid cell expression of superoxide, which, as compared to WT, is enhanced in cells with increased ACE expression and diminished in cells lacking ACE activity.27 Another example, as discussed, is cell ATP content, which also appears to vary directly with cell ACE activity.35 There are several remaining questions of which perhaps the foremost is whether these data in mice are applicable to the human. Our answer to this is that the phenomenon in the mice is very consistent and stable and encompasses both increased and decreased ACE expression. Further, as discussed, analysis of ACEi show that the effects on neutrophil killing of bacteria in vitro are nearly superimposeable between mouse and human. Thus, there is reason to hope that human immune behavior will model that in mice in the sense that increased ACE expression, or ultimately the application of the peptide produced by ACE, may be applicable as a means of enhancing human immune response.

In the last 40 years, scientific research has focused more on disabling the immune response than on discovering ways to strengthen it. This was in response to the need in transplantation and the treatment of autoimmune disease to reduce the deleterious effects of immune activation. Checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated that the opposite approach is also extremely useful in some disease processes.42 It appears clear in the mouse that enhanced myeloid expression of ACE achieves an immune response significantly better than that possibly obtainable by WT animals. Our hope is that additional investigation and discovery into how ACE affects the immune response may provide another means to increase cell immunity and may be applicable in a variety of chronic conditions now not treated through immune manipulation.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by AHA Grants 19CDA34760010 (Z.K.), 16SDG30130015 (J.F.G.), and NIH grants P01HL129941 (K.E.B.), R01AI134714 (K.E.B.), R01AI134714-S1 (K.E.B.), R01HL142672 (J.F.G.), P30DK063491 (J.F.G.), and K99HL141638 (D.O-D).

References

- 1.Lentz KE, Skeggs LT Jr, Woods KR, Kahn JR, Shumway NP. The amino acid composition of hypertensin II and its biochemical relationship to hypertensin I. J Exp Med. 1956. Aug 1;104(2):183–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.104.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skeggs LT Jr, Lentz KE, Kahn JR, Shumway NP, Woods KR. The amino acid sequence of hypertensin. II. J Exp Med. 1956. Aug 1;104(2):193–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.104.2.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein KE, Ong FS, Blackwell WL, Shah KH, Giani JF, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Shen XZ, Fuchs S, Touyz RM. A modern understanding of the traditional and nontraditional biological functions of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Pharmacol Rev. 2012. Dec 20;65(1):1–46. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.006809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semis M, Gugiu GB, Bernstein EA, Bernstein KE, Kalkum M. The plethora of angiotensin-converting enzyme-processed peptides in mouse plasma. Anal Chem. 2019. May 21;91(10):6440–6453. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieberman J Elevation of serum angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) level in sarcoidosis. Am J Med. 1975. Sep;59(3):365–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baudin B New aspects on angiotensin-converting enzyme: from gene to disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002. Mar;40(3):256–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams GT, Williams WJ. Granulomatous inflammation - a review. J Clin Pathol. 1983. Jul;36(7):723–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brice EA, Friedlander W, Bateman ED, Kirsch RE. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme activity, concentration, and specific activity in granulomatous interstitial lung disease, tuberculosis, and COPD. Chest. 1995. Mar;107(3):706–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein KE, Khan Z, Giani JF, Cao DY, Bernstein EA, Shen XZ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018. May;14(5):325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cronan MR, Beerman RW, Rosenberg AF, Saelens JW, Johnson MG, Oehlers SH, Sisk DM, Jurcic Smith KL, Medvitz NA, Miller SE, Trinh LA, Fraser SE, Madden JF, Turner J, Stout JE, Lee S, Tobin DM. Macrophage Epithelial Reprogramming Underlies Mycobacterial Granuloma Formation and Promotes Infection. Immunity. 2016. Oct 18;45(4):861–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diet F, Pratt RE, Berry GJ, Momose N, Gibbons GH, Dzau VJ. Increased accumulation of tissue ACE in human atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1996. Dec 1;94(11):2756–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohishi M, Ueda M, Rakugi H, Naruko T, Kojima A, Okamura A, Higaki J, Ogihara T. Enhanced expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme is associated with progression of coronary atherosclerosis in humans. J Hypertens. 1997. Nov;15(11):1295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saijonmaa O, Nyman T, and Fyhrquist F Atorvastatin inhibits angiotensin-converting enzyme induction in differentiating human macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 2007. Apr; 292, H1917–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen XZ, Li P, Weiss D, Fuchs S, Xiao HD, Adams JA, Williams IR, Capecchi MR, Taylor WR, Bernstein KE. Mice with enhanced macrophage angiotensin-converting enzyme are resistant to melanoma. Am J Pathol. 2007. Jun;170(6):2122–34. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao T, Bernstein KE, Fang J, Shen XZ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme affects the presentation of MHC class II antigens. Lab Invest. 2017. Jul;97(7):764–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen PE. Recent advances in antigen processing and presentation. Nat Immunol. 2007. Oct;8(10):1041–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purcell AW, Elliott T. Molecular machinations of the MHC-I peptide loading complex. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008. Feb;20(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein KE, Khan Z, Giani JF, Cao DY, Bernstein EA, Shen XZ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018. May;14(5):325–336. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2018.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leone P, Shin EC, Perosa F, Vacca A, Dammacco F, Racanelli V. MHC class I antigen processing and presenting machinery: organization, function, and defects in tumor cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013. Aug 21; 105(16):1172–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roche PA, Furuta K. The ins and outs of MHC class II-mediated antigen processing and presentation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015. Apr; 15(4):203–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen XZ, Billet S, Lin C, Okwan-Duodu D, Chen X, Lukacher AE, Bernstein KE. The carboxypeptidase ACE shapes the MHC class I peptide repertoire. Nat Immunol. 2011. Oct 2;12(11):1078–85. doi: 10.1038/ni.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen XZ, Lukacher AE, Billet S, Williams IR, Bernstein KE. Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme changes major histocompatibility complex class I peptide presentation by modifying C termini of peptide precursors. J Biol Chem. 2008. Apr 11;283(15):9957–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709574200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song T, Choi CH, Kim MK, Kim ML, Yun BS, Seong SJ. The effect of angiotensin system inhibitors (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers) on cancer recurrence and survival: A meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2017. Jan;26(1):78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hicks BM, Filion KB, Yin H, Sakr L, Udell JA, Azoulay L. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and risk of lung cancer: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2018. Oct 24;363:k4209. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SH, Chun KJ, Park J, Kim J, Sung JD, Park RW, Choi J, Yang K. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and incidence of lung cancer in a population based cohort of common data model in Korea. Sci Rep. 2021. Sep 17;11(1):18576. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97989-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okwan-Duodu D, Datta V, Shen XZ, Goodridge HS, Bernstein EA, Fuchs S, Liu GY, Bernstein KE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme overexpression in mouse myelomonocytic cells augments resistance to Listeria and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2010. Dec 10;285(50):39051–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan Z, Shen XZ, Bernstein EA, Giani JF, Eriguchi M, Zhao TV, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Fuchs S, Liu GY, Bernstein KE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme enhances the oxidative response and bactericidal activity of neutrophils. Blood. 2017. Jul;130(3):328–339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-752006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao DY, Giani JF, Veiras LC, Bernstein EA, Okwan-Duodu D, Ahmed F, Bresee C, Tourtellotte WG, Karumanchi SA Bernstein KE, Khan Z. An ACE inhibitor reduces bactericidal activity of human neutrophils in vitro and impairs mouse neutrophil activity in vivo. Sci Transl Med. 2021. Jul 28;13(604):eabj2138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan Z, Cao DY, Giani JF, Bernstein EA, Veiras LC, Fuchs S, Wang Y, Peng Z, Kalkum M, Liu GY, Bernstein KE. Overexpression of the C-domain of angiotensin-converting enzyme reduces melanoma growth by stimulating M1 macrophage polarization. J Biol Chem. 2019. Mar 22;294(12):4368–4380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okwan-Duodu D, Weiss D, Peng Z, Veiras LC, Cao DY, Saito S, Khan Z, Bernstein EA, Giani JF, Taylor WR, Bernstein KE. Overexpression of myeloid angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) reduces atherosclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019. Dec 10;520(3):573–579. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.10.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernstein KE, Koronyo Y, Salumbides BC, Sheyn J, Pelissier L, Lopes DH, Shah KH, Bernstein EA, Fuchs DT, Yu JJ, Pham M, Black KL, Shen XZ, Fuchs S, Koronyo-Hamaoui M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme overexpression in myelomonocytes prevents Alzheimer's-like cognitive decline. J Clin Invest. 2014. Mar;124(3):1000–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI66541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koronyo-Hamaoui M, Sheyn J, Hayden EY, Li S, Fuchs DT, Regis GC, Lopes DHJ, Black KL, Bernstein KE, Teplow DB, Fuchs S, Koronyo Y, Rentsendorj A. Peripherally derived angiotensin converting enzyme-enhanced macrophages alleviate Alzheimer-related disease. Brain. 2020. Jan 1;143(1):336–358. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jankowsky JL, Fadale DJ, Anderson J, Xu GM, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Lee MK, Younkin LH, Wagner SL, Younkin SG, Borchelt DR. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum Mol Genet. 2004. Jan 15;13(2):159–70. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo Sasso G, Schlage WK, Boué S, Veljkovic E, Peitsch MC, Hoeng J. The Apoe(−/−) mouse model: a suitable model to study cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in the context of cigarette smoke exposure and harm reduction. J Transl Med. 2016. May 20;14(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0901-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verdile G, Keane KN, Cruzat VF, Medic S, Sabale M, Rowles J, Wijesekara N, Martins RN, Fraser PE, Newsholme P. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: The Molecular Connectivity between Insulin Resistance, Obesity, and Alzheimer's Disease. . Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:105828. doi: 10.1155/2015/105828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao DY, Spivia WR, Veiras LC, Khan Z, Peng Z, Jones AE, Bernstein EA, Saito S, Okwan-Duodu D, Parker SJ, Giani JF, Divakaruni AS, Van Eyk JE, Bernstein KE. ACE overexpression in myeloid cells increases oxidative metabolism and cellular ATP. J Biol Chem. 2020. Jan 31;295(5):1369–1384. doi: 10.1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Dorry HA, Bull HG, Iwata K, Thornberry NA, Cordes EH, Soffer RL. Molecular and catalytic properties of rabbit testicular dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 1982. Dec 10;257(23):14128–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krege JH, John SW, Langenbach LL, Hodgin JB, Hagaman JR, Bachman ES, Jennette JC, O'Brien DA, Smithies O. Male-female differences in fertility and blood pressure in ACE-deficient mice. Nature. 1995. May 11;375(6527):146–8. doi: 10.1038/375146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esther CR Jr, Howard TE, Marino EM, Goddard JM, Capecchi MR, Bernstein KE. Mice lacking angiotensin-converting enzyme have low blood pressure, renal pathology, and reduced male fertility. Lab Invest. 1996. May;74(5):953–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagaman JR, Moyer JS, Bachman ES, Sibony M, Magyar PL, Welch JE, Smithies O, Krege JH, O'Brien DA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998. Mar 3;95(5):2552–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuchs S, Frenzel K, Hubert C, Lyng R, Muller L, Michaud A, Xiao HD, Adams JW, Capecchi MR, Corvol P, Shur BD, Bernstein KE. Male fertility is dependent on dipeptidase activity of testis ACE. Nat Med. 2005. Nov;11(11):1140–2. doi: 10.1038/nm1105-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018. Sep;8(9):1069–1086. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]