Abstract

Background:

Despite the advent of innovative knee prosthesis design, a consistent first-option knee implant design in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) remained unsettled. This study aimed to compare the clinical effects among posterior-stabilized (PS), cruciate-retaining (CR), bi-cruciate substituting (BCS), and bi-cruciate retaining designs for primary TKA.

Methods:

Electronic databases were systematically searched to identify eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies from inception up to July 30, 2021. The primary outcomes were the range of knee motion (ROM), and the secondary outcomes were the patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and complication and revision rates. Confidence in evidence was assessed using Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis. The Bayesian network meta-analysis was performed for synthesis.

Results:

A total of 15 RCTs and 18 cohort studies involving 3520 knees were included. The heterogeneity and inconsistency were acceptable. There was a significant difference in ROM at the early follow-up when PS was compared with CR (mean difference [MD] = 3.17, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.07, 7.18) and BCS was compared with CR (MD = 9.69, 95% CI 2.18, 17.51). But at the long-term follow-up, there was no significant difference in ROM in any one knee implant compared with the others. No significant increase was found in the PROMs and complication and revision rates at the final follow-up time.

Conclusions:

At early follow-up after TKA, PS and BCS knee implants significantly outperform the CR knee implant in ROM. But in the long run, the available evidence suggests different knee prostheses could make no difference in clinical outcomes after TKA with extended follow-up.

Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty, Knee implant, Range of knee motion, Patient-reported outcome measures

Introduction

As a common degenerative disease, the pain, deformation, and disability caused by knee osteoarthritis (KOA) affect more than 250 million people worldwide,[1] which was the position as of 2020.[2] Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the most common and efficacious treatment option for this advanced degenerative disease.[3] With the progress in technologies and inventions of new materials, and as a result of the collaboration between surgeons and engineers for the past 50 years, dozens of prostheses have been designed so far.[4] These different implant designs attempted to reach the highest range of knee motion (ROM), regain knee function, and decrease pain and wear.[5] The crucial key of revision rate after primary TKA for various reasons was to evaluate the success of the surgery and the prognosis of patients. Furthermore, the intense societal need for improving medical quality of care has shifted the focus from the “hard” outcome measures initially introduced to “softer” outcomes. The “softer” outcomes after TKA surgery are patient-report outcomes scores (PROMs) including ROM and Oxford Knee Score (OKS), which become more and more noticeable.

The prosthetic implant options mainly involve posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) retention, PCL substitution, bi-cruciate retaining (BCR), and bi-cruciate substituting (BCS).[4] The optimal mode of design in TKA has still been in dispute for decades.[6] It was reported in 2016 that in the United States nearly 50% of surgeons prefer to posterior stabilized (PS) implants, with cruciate-retaining (CR) constituting approximately 42% of primary knee arthroplasty cases.[7] But in CR and PS TKA procedures, the resected anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) can cause anterior knee laxity and abnormal tibiofemoral positioning.[8] BCR TKA retains the PCL as well as the ACL. A recent study showed that BCR TKA had similar functional and radiographic outcomes compared to CR TKA in a similar cohort of patients.[9] BCS TKA was designed to promote normal knee kinematics by incorporating both anterior and posterior post-cam mechanisms to replicate the function of ACL and PCL. However, because of limited evidence about BCR and BCS, it is unclear as to what the technical differences and specific superiority are among the PS, CR, BCS, and BCR designs.

Network meta-analysis (NMA) can give a relative ranking of treatments and facilitate the comparisons between collected interventions; and it also analyses the pooled data by connecting a network of evidence.[10] NMA can not only evaluate all head-to-head comparisons but also fill the gaps of indirect comparisons to obtain greater statistical power and precision.[11] This study aims to perform a systematic review and NMA of current randomized controlled trials (RCTs) among PS, CR, BCR, and BCS TKA designs and finally find the optimal pattern.

Methods

Study selection and exclusion

The inclusion criteria of the literature were: (1) The study included patients who were diagnosed with KOA undergoing primary TKA surgery. (2) The surgery was planned to use at least two different knee prosthesis designs among PS, CR, BCS, and BCR implants. (3) The study included at least one of the following clinical outcome measures: PROMs such as the Knee Society Function Score (KSFS) and OKS, the ROM, and the complication and revision rates. (4) The design of the study was RCT, prospective cohort, or retrospective cohort study.

The exclusion criteria of the literature included: (1) the study has published only an abstract but no formal full-text paper; (2) the study has been carried out in patients undergoing emergency surgery, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, and revision TKA; (3) the study has used mobile-bearing TKA, medial pivot TKA, ultra-congruent TKA, high-flex PS TKA, and high-flex CR TKA; (4) when data from the same study were released at different stages, the most recently published findings were traced back and included.

Search strategy

The pre-piloted main search words, such as “posterior stabilized,” “cruciate retaining,” “arthroplasty,” and “randomized controlled trial” were searched in the PubMed, Embase, Medline, Ovid, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library from inception up to July 2021 with restriction in English-language. The detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary Material 1. According to the inclusion criteria, the titles and abstracts of the relevant studies were obtained and screened. The full texts of potentially eligible articles were evaluated in duplicate by two independent researchers. Discrepancies when screening the title, abstract, and full text were resolved by discussing with senior researchers.

Data synthesis and outcome measures

The primary outcomes were the ROM at the early and long-term follow-up. The secondary outcomes were PROMs concluded by KSFS and OKS in the final follow-up time, and the complication and revision rates during the whole follow-up duration. Complications included aseptic loosening, fractures, deep infection, bearing dislocation, pain at the operation site, and manipulation. We defined the early follow-up of ROM as the patient after TKA from discharge to postoperative 2 years (≤2 years). The long-term follow-up of ROM was defined as longer than 2 years (>2 years).

Data extraction

The data from each eligible article were independently extracted in duplicate using pre-piloted, standardized Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (Excel 2016) by two researchers. The data extracted included the first author, publication year, region of the study object, number of participants, mean age, treatments, outcomes, and follow-up duration. In the case of missing data, we attempted to extract data from other meta-analyses or perform calculations according to the Cochrane Collaboration for Systematic Reviews guidelines.[12]

Risk of bias (ROB) and quality of evidence assessment

This process was conducted independently by two reviewers. The revised Cochrane ROB (ROB V.2.0) tool[13] was used to assess the ROB in five domains of each RCT study: bias due to the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result. Domains were scored as low, moderate, or high ROB. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)[14] was used to assess the quality of prospective and retrospective cohort studies in three dimensions: selection of the study population, comparability of the groups under study, and assessment of outcome. Studies that received a score of 9 stars were considered to have a low ROB, 7 or 8 stars to have a moderate ROB, and ≤6 stars to have a high ROB. Discrepancies between investigators were resolved by consensus and arbitration by a panel of adjudicators. The credibility of findings from each NMA was evaluated using a web-based application: confidence in network meta-analysis (CINeMA) (https://cinema.ispm.unibe.ch/).[15] The confidence in the evidence of each treatment comparison was graded by CINeMA based on six domains: within-study bias, reporting bias, indirectness, indirectness imprecision, heterogeneity, and incoherence and graded as high, moderate, low, and very low for each outcome.

Statistical analysis

First, we evaluated the transitivity assumption by comparing the distribution of potential effect modifiers (mean age, female proportion, body mass index [BMI], and average follow-up duration) in our study. Then, we carried out the traditional pair-wise meta-analysis to analyze the direct comparisons and I2-statistics to examine the heterogeneity between studies. Subsequently, we found and omitted the studies with obviously high heterogeneity by using sensitivity analysis.[16] Then we conducted the network maps that showed the whole network with nodes as TKA designs and the size of nodes implying the sample size. The goodness fit between fixed- and random-effect models were assessed through leverage plots and we selected the model with fewer outliers based on a visual inspection of the leverage plots and comparison of the deviance information criterion values. We examined publication bias in contour-enhanced funnel plots.[16]

We assessed consistency in the network by fitting the inconsistency model and comparing it to the consistency model. A plot of the posterior mean deviance of the individual data points in the inconsistency model against their posterior mean deviance in the consistency model can highlight discrepancies between the two models.[17] Besides, we evaluated consistency statistically using node-splitting analysis that illustrates the inconsistency between indirect and direct comparisons.[18]

All the analyses and illustrations were done in R 3.6.2 (https://www.r-project.org/). using packages: “BUGSnet,”[17] “gemtc,”[19] “rjags,” and “netmeta.”[20]

Results

Search results, study characteristics

On electronically searching the aforementioned databases and the reference sections of relevant articles, 1869 records were respectively identified. 1129 were excluded for duplication and 586 excluded for meeting the exclusion criteria, after which there were 154 full-text studies left to further assess for eligibility. The flowchart for the selection of studies is displayed in Figure 1. Eventually, a total of 15 RCTs and 18 cohort studies involving 3453 participants with 3520 knees were included for this study.[21–52] The comparison of detailed information of eligible patients was documented in Table 1. Studies were full reports published between 2002 and 2021 that included knee prosthesis design. The inclusion/exclusion criteria used in the included study and patients’ characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The transitivity of potential effect modifiers is illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. There were three outliers in the female proportion, two in BMI and five in the average follow-up duration. The mean age of the patients ranged from 57.6 to 75.1 years. The KOA accounted for 98.1% of the entire population. The minimal mean BMI of patients reported by included articles was 26.0 kg/m2, and the maximal was 34.1 kg/m2. The follow-up duration of included studies ranged from 3.0 months to 12.7 years. The enhanced funnel plots were assessed for potential publication bias detection in our study and most of the comparisons showed little bias, as can be seen from Supplementary Figures 2–5.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the selection of studies. TKA: Total knee arthroplasty.

Table 1.

Baseline information of all included studies.

| Study | Research year | Type of study | Region | Number of knees | Group | Postoperative follow-up time | Outcome measures | Results |

| Baumann 2016 | 2013–2014 | Prospective cohort study | Germany | 20 | 1. BCR | 9 months | ROM | BCR implants could provide improved functional properties. |

| 20 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Chaudhary 2008 | 1999–2003 | RCT | Canada | 49 | 1. PS | 3 and 24 months | ROM WOMAC RAND-36 Complication |

The two treatment groups had a similar range of motion of the knee over the initial two-year postoperative period. |

| 51 | 2. CR | |||||||

| Harato 2008 | 1997–2000 | RCT | Canada | 99 | 1. CR | 60 months | ROM KSS WOMAC Complication |

PS design does appear to support significantly improved postoperative ROM compared with the CR design. |

| 93 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Scarvell 2017 | 2006–2010 | RCT | Australia | 116 | 1. BCS | 24 months | ROM OKS KSS Complication Revision |

There was no evidence of clinical superiority of one implant over the other at 2 years |

| 122 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Schimmel 2014 | 2002–2013 | RCT | Netherlands | 62 | 1. BCS | 24 months | ROM KSS Complication Revision |

Patients who receive a BCS system compared with those who receive a conventional PS system have comparable knee flexion characteristics and clinical and functional outcomes. |

| 62 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Troelsen 2019 | 2014–2015 | RCT | Denmark | 25 | 1. BCR | 24 months | OKS FJS Revision |

They found no differences between the BCR and CR implants in terms of patient-reported outcome measure scores at 2 years. |

| 25 | 2. CR | |||||||

| Boom 2019 | 2008–2011 | RCT | Netherlands | 59 | 1. CR | 12 months | ROM WOMAC |

There are no differences in speed of recovery of WOMAC or ROM during the first postoperative year after CR or PS TKA. |

| 55 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Ward 2011 | 2007–2010 | RCT | Australia | 13 | 1. BCS | 36 months | OKS PTA |

The BCS TKR produced a higher mean PTA than the PS TKR. |

| 15 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Tanzer 2002 | 2000–2010 | RCT | Canada | 20 | 1. CR | 3, 6, 12 and 24 months | KSS ROM Complication |

They could find no difference in the clinical, functional, or radiographic outcome of CR or PS TKAs at 2 years postoperatively. |

| 20 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Cho 2016 | 2015–2016 | Prospective cohort study | Korea | 51 | 1. CR | 3 months | KSS ROM |

The KSS and ROM were not significantly different between two groups. |

| 51 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Ozturk 2016 | 2007–2008 | RCT | Germany | 33 | 1. CR | 1, 2, 3, 12 and 84 months | KSS ROM |

PS knees gained faster and larger active flexion arc than CR knees |

| 28 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Christensen 2016 | 2013–2014 | Retrospective cohort study | America | 66 | 1. CR | 12 months | ROM | BCR implant has inferior survivorship compared with a conventional CR implant. |

| 237 | 2. BCR | |||||||

| Baumann 2017 | 2013–2015 | Prospective cohort study | Germany | 34 | 1. BCR | 18 months | FJS VAS EQ-5D Complication |

The group of PS-TKA patients had a lower mean score value in the FJS compared to the BCR-group. |

| 34 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Beaupre 2016 | 1999–2003 | RCT | Canada | 32 | 1. CR | 120 months | WOMAC RAND-36 Revision |

Over 10 years postoperatively, low levels of revision or re-operation were reported in the PS and CR TKA group. |

| 30 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Maruyama 2004 | 1998–2000 | RCT | Japan | 20 | 1. CR | 31.7 months | ROM KSS |

There were no significant differences between the CR and PS TKAs in postoperative knee scores. However, postoperative improvement in range of motion was significantly superior in the PS group. |

| 20 | 2. PS | 30.6 months | ||||||

| Binabdrazak 2013 | 2007–2008 | Retrospective cohort study | Singapore | 112 | 1. CR | 24 months | ROM KSS OKS SF-36 Complication |

The PS group had a significantly better final range of motion as compared to the CR group. There were no significant differences in the other outcome scores. |

| 83 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Carvalho 2014 | 2008–2009 | Prospective cohort study | Brazil | 14 | 1. CR | 30.6 months | ROM | There were no differences in ROM between CR and PS TKA. |

| 24 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Catani 2004 | NA | RCT | Sweden | 20 | 1. CR | 3, 6, 12, 24 months | ROM HSS IKS Complication |

PS knee implants do not show a statistically significantly different migration of the tibial component concerning CR implants. |

| 20 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Chen 2014 | 2001–2010 | Prospective cohort study | Singapore | 33 | 1. CR | 6, 24 months | KSS OKS |

Although PS prostheses offer better knee flexion in TKA after the previous HTO, the knee stability, clinical scores and revision rate at 6 months and 2 years post-TKA are comparable between CR and PS prostheses. |

| 100 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Conditt 2004 | NA | Retrospective cohort study | America | 28 | 1. CR | 12 months | KSS ROM |

Substitution for the PCL may not fully restore the functional capacity of the intact PCL, particularly in high-demand activities that involve deep flexion. |

| 21 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Kolisek 2009 | NA | Prospective cohort study | America | 45 | 1. CR | 60 months | KSS ROM |

This study did not conclusively demonstrate the superiority of one knee design over the other. |

| 46 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Inui 2020 | 2012–2017 | Retrospective cohort study | Japan | 56 | 1. BCS | 24 months | ROM KOOS |

BCS TKA showed more normal-like kinematics and better clinical results than PS TKA. |

| 55 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Laidlaw 2010 | NA | Retrospective cohort study | America | 55 | 1. CR | 61.2 months | ROM KSS |

Passive ROM after TKA was significantly greater than pre-operative passive ROM for each cohort. |

| 42 | 2. BCR | 10.5 months | ||||||

| 30 | 3. BCS | 27.6 months | ||||||

| Lavoie 2018 | 2009–2013 | Retrospective cohort study | Canada | 100 | 1. BCR | 6 weeks, 6, 12, 24 months |

ROM KSS |

Postoperative ROM was similar between BCR TKA and PS TKA when preoperative knee flexion was 130 degrees or more, and when there was no preoperative flexion contracture |

| 100 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Matsumoto 2012 | 2003–2005 | RCT | Japan | 25 | 1. CR | 71.9 months 70.6 months |

KSS ROM |

There were no significant differences in clinical outcomes between CR and PS at the 5-year follow-up. |

| 25 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Moro-oka 2007 | NA | Prospective cohort study | Japan | 5 | 1. CR | 72 months 70 months |

KSS ROM |

Preserving both cruciate ligaments in total knee arthroplasty appears to maintain some basic features of normal knee kinematics in these activities. |

| 9 | 2. BCR | |||||||

| Mugnai 2013 | 2007–2009 | Retrospective cohort study | Italy | 84 | 1. PS | 30 months 29 months |

ROM KOOS Complication |

The bearing geometry and kinematic pattern of different guided-motion prosthetic designs can affect the clinical–functional outcome and complications type in primary TKA. |

| 103 | 2. BCS | |||||||

| Sando 2015 | 1995–2000 | Prospective cohort study | Canada | 143 | 1. CR | 12.7 years | KSS WOMAC SF-12 ROM revision |

PS performed better than CR in terms of clinical scores and range of motion. |

| 271 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Song 2020 | 2015–2017 | Prospective cohort trial | Korea | 90 | 1. CR | 12 months | KSS WOMAC ROM |

There was no notable difference in functional outcome, range of motion, kinematics, and survival rate between CR and PS TKAs. |

| 64 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Boom 2014 | NA | Prospective cohort study | Netherlands | 9 | 1. CR | 6–9 months | KSS WOMAC ROM |

The study showed no differences in kinematics and kinetics between the PS and the CR TKA design. |

| 12 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Vermesan 2015 | NA | RCT | Italy | 25 | 1. CR | 6, 24 months | KSS ROM |

Both implants had the potential to assure great outcomes. |

| 25 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Victor 2005 | NA | RCT | America | 22 | 1. CR | 60 months | KSS WOMAC SF-36 |

Despite similar clinical outcomes, there are significant kinematic differences between cruciate-retaining and cruciate-substituting arthroplasties. |

| 22 | 2. PS | |||||||

| Yoshiya 2005 | 1998–2000 | Prospective cohort study | Japan | 20 | 1. CR | 18–53 months | ROM | Flexion kinematics for the PS TKA was characterized by the maintenance of a constant contact position under weight-bearing conditions and posterior femoral rollback in passive flexion. |

| 20 | 2. PS |

BCR: Bi-cruciate retaining; BCS: Bi-cruciate substituting; CR: Cruciate-retaining; EQ-5D: EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire; FJS: Forgotten Joint Score; HSS: Hospital for Special Surgery; HTO: High tibial osteotomy; IKS: International Knee Society; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; KSS: Knee Society Score; NA: Not available; OKS: Oxford Knee Score; PCL: Posterior cruciate ligament; PS: Posterior-stabilized; PTA: Patellar tendon angle; RAND-36: RAND 36-Item Health Survey; RCT: Random controlled trial; ROM: Range of knee motion; SF-12: Short Form-12; SF-36: Short Form-36; TKA: Total knee arthroplasty; TKR: Total knee replacement; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Quality assessment

The summary ROB assessment of the 15 included RCTs is illustrated in Supplementary Figure 6. The authors showed the results of each quality item as percentages across studies. Most of the studies are with low ROB in all the items. Out of 18 cohort studies assessed by NOS [Supplementary Table 2], three studies were of good quality, nine were of fair quality, and six studies were of poor quality. The results of confidence from NMA are summarized in Table 2 and the majority of comparisons were graded as low confidence.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis summary of all outcomes of node splitting analysis and confidence in network meta-analysis (CINeMA).

| Outcome | Comparison | Number of knees | Number of studies | Node-splitting (P-value) | Nature of evidence | CINeMA level | Downgraded reason |

| ROM (early follow-up) | CR vs. PS | 709 | 10 | 0.968 | Mixed | Moderate | Heterogeneity |

| BCS vs. PS | 111 | 1 | 0.283 | Mixed | Low | With-study bias Heterogeneity |

|

| BCS vs. CR | 85 | 1 | 0.398 | Mixed | Moderate | With-study bias | |

| BCR vs. PS | 40 | 1 | 0.205 | Mixed | Moderate | With-study bias | |

| BCR vs. CR | 400 | 2 | 0.295 | Mixed | Low | With-study bias Heterogeneity |

|

| BCR vs. BCS | 72 | 1 | 0.205 | Mixed | Low | With-study bias Heterogeneity |

|

| ROM (long-term follow-up) | CR vs. PS | 876 | 7 | – | Mixed | Very low | Heterogeneity Incoherence |

| BCS vs. PS | 187 | 1 | – | Mixed | Low | Incoherence | |

| BCS vs. CR | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Low | Incoherence | |

| BCR vs. PS | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Very low | Imprecision Incoherence |

|

| BCR vs. CR | 1 | 14 | – | Mixed | Very low | Incoherence Imprecision |

|

| BCR vs. BCS | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Very low | Imprecision Incoherence |

|

| KSFS | CR vs. PS | 1353 | 12 | 0.839 | Mixed | Low | Heterogeneity |

| BCS vs. PS | 362 | 2 | 0.524 | Mixed | Low | Heterogeneity | |

| BCS vs. CR | 85 | 1 | 0.775 | Mixed | Low | Heterogeneity | |

| BCR vs. PS | 200 | 1 | 0.686 | Mixed | Low | Heterogeneity | |

| BCR vs. CR | 111 | 2 | 0.767 | Mixed | Moderate | Heterogeneity | |

| BCR vs. BCS | 72 | 1 | 0.232 | Mixed | Low | With-study bias | |

| OKS | CR vs. PS | 327 | 2 | – | Mixed | Moderate | Incoherence |

| BCS vs. PS | 266 | 2 | – | Mixed | Very low | Incoherence Heterogeneity |

|

| BCS vs. CR | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Very low | Incoherence Heterogeneity |

|

| BCR vs. PS | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Low | Incoherence | |

| BCR vs. CR | 48 | 1 | – | Mixed | Low | Incoherence | |

| BCR vs. BCS | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Low | Incoherence | |

| Complication rate | CR vs. PS | 681 | 6 | 0.780 | Mixed | Low | Imprecision |

| BCS vs. PS | 549 | 3 | – | Mixed | High | – | |

| BCS vs. CR | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Low | Imprecision | |

| BCR vs. PS | 240 | 2 | 0.771 | Mixed | Low | Imprecision | |

| BCR vs. CR | 351 | 2 | 0.781 | Mixed | Very low | With-study bias Imprecision |

|

| BCR vs. BCS | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Low | Imprecision | |

| Revision rate | CR vs. PS | 476 | 2 | – | Mixed | Very low | With-study bias Imprecision Incoherence |

| BCS vs. PS | 362 | 2 | – | Mixed | Very low | Imprecision Incoherence |

|

| BCS vs. CR | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Very low | Heterogeneity Incoherence |

|

| BCR vs. PS | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Very low | Imprecision Incoherence |

|

| BCR vs. CR | 351 | 2 | – | Mixed | Very low | Imprecision Incoherence |

|

| BCR vs. BCS | 0 | 0 | – | Indirect | Very low | Heterogeneity Incoherence |

BCR: Bi-cruciate retaining; BCS: Bi-cruciate substituting; CR: Cruciate-retaining; KSFS: Knee Society Function Score; OKS: Oxford Knee Score; PS: Posterior-stabilized; ROM: Range of knee motion; SD: Standard difference; –: Not available.

Primary outcomes

Model choice and consistency checking

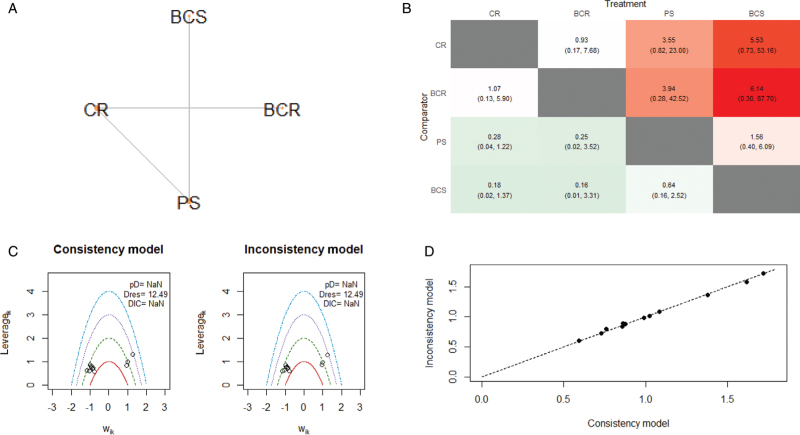

As shown in the leverage plots of random and fixed effects, we all chose the random model effect due to low heterogeneity, except OKS [Supplementary Figure 7]. We assessed consistency in the network by fitting a random-effects inconsistency model and comparing it to our random-effects consistency model. In general, we chose the consistency model due to its adequate fit and parsimony. Except for several points, the data were near the y = x line, indicating a general agreement between the two models. This impelled us to proceed with the more parsimonious (consistency) model [Figures 2–7].

Figure 2.

Network analysis results for ROM at the early follow-up. (A) The network plot showing the interventions included in the network analysis. Size of nodes represents the sample size of each intervention; edges are the frequency of comparison. (B) The league plot for surgical interventions. The number in each cell represents the comparison between the name of column vs. the name of the row. Results with statistically significance are annotated with an asterisk. (C) The leverage plots showing the goodness of consistency and inconsistency effects. Dres, the posterior mean of the residual deviance. pD, the effective number of parameters, calculated as the sum of the leverages. (D) The league plot for the posterior mean deviance of the individual data points in the inconsistency model compared with the consistency mode. BCR: Bi-cruciate retaining; BCS: Bi-cruciate substituting; CR: Cruciate-retaining; DIC: Deviance information criterion; PS: Posterior-stabilized; ROM: Range of knee motion.

Figure 7.

Network analysis results for revision rate. (A) The network plot showing the interventions included in the network analysis. Size of nodes represents the sample size of each intervention; edges are the frequency of comparison. (B) The league plot for surgical interventions. The number in each cell represents the comparison between the name of the column vs. the name of the row. (C) The leverage plots showing the goodness of consistency and inconsistency effects. Dres, the posterior mean of the residual deviance. pD, the effective number of parameters, calculated as the sum of the leverages. (D) The league plot for the posterior mean deviance of the individual data points in the inconsistency model compared with the consistency mode. BCR: Bi-cruciate retaining; BCS: Bi-cruciate substituting; CR: Cruciate-retaining; DIC: Deviance information criterion; PS: Posterior-stabilized.

Range of knee motion

The network plot encompassed a total of 13 studies with 1290 knees in ROM at the early follow-up [Figure 2A]. The connections between nodes represented direct comparisons. There was a significant difference in ROM at the early follow-up when PS was compared with CR (mean difference [MD] = 3.17, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.07, 7.18) and BCS was compared with CR (MD = 9.69, 95% CI 2.18, 17.51) [Figure 2B]. No significant difference was found in other comparisons.

We established networks concerning ROM in the long-term follow-up for comparison with a total of nine studies with 1077 knees [Figure 3A]. The result of the NMA for ROM is summarized in Figure 3B, and there was no statistically significant increase in ROM in any one knee implant compared with the others at the long-term follow-up.

Figure 3.

Network analysis results for ROM at the long-term follow-up. (A) The network plot showing the interventions included in the network analysis. Size of nodes represents the sample size of each intervention; edges are the frequency of comparison. (B) The league plot for surgical interventions. The number in each cell represents the comparison between the name of column vs. the name of the row. (C) The leverage plots showing the goodness of consistency and inconsistency effects. Dres, the posterior mean of the residual deviance. pD, the effective number of parameters, calculated as the sum of the leverages. (D) The league plot for the posterior mean deviance of the individual data points in the inconsistency model compared with the consistency mode. BCR: Bi-cruciate retaining; BCS: Bi-cruciate substituting; CR: Cruciate-retaining; DIC: Deviance information criterion; PS: Posterior-stabilized; ROM: Range of knee motion.

Secondary outcomes

Knee society function score

We established networks for comparison for KSFS, in which each node denoted an intervention [Figure 4A]. A total of 2183 knees and 17 studies were connected in this NMA. In KSFS, there was no intervention which was significantly superior to another [Figure 4B].

Figure 4.

Network analysis results for KSFS. (A) The network plot showing the interventions included in the network analysis. Size of nodes represents the sample size of each intervention; edges are the frequency of comparison. (B) The league plot for surgical interventions. The number in each cell represents the comparison between the name of the column vs. the name of the row. (C) The leverage plots showing the goodness of consistency and inconsistency effects. Dres, the posterior mean of the residual deviance. pD, the effective number of parameters, calculated as the sum of the leverages. (D) The league plot for the posterior mean deviance of the individual data points in the inconsistency model compared with the consistency mode. BCR: Bi-cruciate retaining; BCS: Bi-cruciate substituting; CR: Cruciate-retaining; DIC: Deviance information criterion; KSFS: Knee Society Function Score; PS: Posterior-stabilized.

Oxford knee score

We performed the NMA that included 641 knees and 5 studies [Figure 5A]. We chose the fixed-effect consistency model [Supplementary Figure 5D]. As the NMA league plot of OKS shows, none of the interventions were significantly superior to any other [Figure 5B].

Figure 5.

Network analysis results for OKS. (A) The network plot showing the interventions included in the network analysis. Size of nodes represents the sample size of each intervention; edges are the frequency of comparison. (B) The league plot for surgical interventions. The number in each cell represents the comparison between the name of column vs. the name of row. (C) The leverage plots showing the goodness of consistency and inconsistency effects. Dres, the posterior mean of the residual deviance. pD, the effective number of parameters, calculated as the sum of the leverages. (D) The league plot for the posterior mean deviance of the individual data points in the inconsistency model compared with the consistency mode. BCR: Bi-cruciate retaining; BCS: Bi-cruciate substituting; CR: Cruciate-retaining; DIC: Deviance information criterion; OKS: Oxford Knee Score; PS: Posterior-stabilized.

Complication rate

The network plot on complication rate encompassed 1821 knees within, with a total of 13 studies [Figure 6A]. As the NMA league plot shows, there was no statistically significant difference among the four interventions [Figure 6B].

Figure 6.

Network analysis results for complication rate. (A) The network plot showing the interventions included in the network analysis. Size of nodes represents the sample size of each intervention; edges are the frequency of comparison. (B) The league plot for surgical interventions. The number in each cell represents the comparison between the name of column vs. the name of row. (C) The leverage plots showing the goodness of consistency and inconsistency effects. Dres, the posterior mean of the residual deviance. pD, the effective number of parameters, calculated as the sum of the leverages. (D) The league plot for the posterior mean deviance of the individual data points in the inconsistency model compared with the consistency mode. BCR: Bi-cruciate retaining; BCS: Bi-cruciate substituting; CR: Cruciate-retaining; DIC: Deviance information criterion; PS: Posterior-stabilized.

Revision rate

The network diagram of the revision rate is presented in Figure 7A. A total of 1189 knees and six studies were connected in this NMA. There was no significant difference in the revision rate among the four interventions in NMA [Figure 7B].

Node-splitting method

Node comparisons were carried out to perform a node splitting analysis [Table 2]. The results suggested that there was no significant difference between direct and indirect evidence in our analysis.

Discussion

In this systematic review and NMA, the principal finding was that none of the interventions showed greater clinical significance than any other for clinical outcomes after TKA. This suggested that there was not one superior choice of knee implants for TKA. These findings were consistent with those of the latest meta-analysis by Nisar et al[53] that the implant design alone may not promote improvement in PROMs and ROM following TKA. In the previous meta-analyses, the researchers only attached importance to comparing CR TKA to PS TKA in clinical outcomes. However, there was limited high-quality evidence such as RCTs and prospective cohort studies about BCR and BCS TKA. It was unclear which of the four kinds of implants would have the best efficiency. This NMA was targeted at clarifying and comparing clinical outcomes among four knee implants for patients with KOA in primary TKA.

ROM is a crucial measure of clinical outcome. Even though some meta-analyses demonstrated that PS TKA is superior to CR TKA in respect of ROM, the difference in follow-up time may affect their results as ROM can improve over time.[54,55] Some RCTs reported that ROM at the early follow-up after CR or even PS TKA was decreased compared to baseline.[23,56] Different follow-up periods may have influenced the final comparisons among four knee implant designs. In our pooled results, at early follow-up after TKA, PS and BCS knee implants significantly outperform the CR knee implant in ROM. But there was no statistically significant difference in ROM in any one knee implant compared with the others at long-term follow-up. In the long run, there were no one knee implant designs superior to the others in ROM.

PROMs can reflect the quality of life and functional outcomes of patients after primary TKA. Our results demonstrated that none of the knee prostheses showed significant advancement compared with the others on the available PROMs such as KSFS and OKS. Another two meta-analyses suggested that CR TKA and PS TKA had similar clinical outcomes concerning knee function and postoperative knee pain.[54,57] In contrast, Longo et al[58] demonstrated that PS TKA had a statistically significant greater postoperative improvement of KSFS compared with the CR group. Some studies reported that BCR TKA showed similar other PROMs such as the visual analogue score and the Forgotten Joint Score when compared to CR TKA.[9,59] However, for the newly designed BCS TKA, it resulted in significantly better outcomes when compared with PS TKA in other PROMs such as the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score and stair-climbing ability.[42,60] To resolve the question of whether this superiority matters or not in clinical practice, further investigation and longer follow-up are still needed. Future RCTs should be performed to support new implant designs such as BCR and BCS.

In terms of complications and revisions related to implant safety, the results were in agreement that there was no significant difference in all comparisons between any two knee implants. But Christensen et al[25] found that the BCR implant has inferior survivorship when compared with the CR implant concerning complications after primary TKA. And Schimmel et al[61] reported that patients who received a BCS implant compared with those who received a PS implant had more complications at 2-year follow-up after TKA. It is necessary to conduct further randomized trials to verify these concerns about the new BCR and BCS designs.

This study has several strengths. Compared with other meta-analyses, this meta-analysis and systematic review included the latest RCTs and cohort studies to provide four knee implants. Additionally, we also performed a detailed assessment of methodological quality. Notably, in this NMA, we evaluated four knee implant designs for ROM at early and long-term follow-up after TKA by direct comparisons and indirect comparisons, which have never been carried out in previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

Several limitations should be noted. First, it is important to acknowledge that some studies included patients with conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, which are distinct from KOA. Second, we used the final follow-up data after TKA as clinical outcomes rather than advancement between preoperative baseline and follow-up endpoints. It might not be the best method to analyze results. Finally, the scoring system commonly adopted by the authors of the included studies was not sensitive enough and some authors did not take the standard scoring scale.

In summary, PS and BCS knee implants significantly outperform the CR knee implant in ROM at early follow-up after TKA. But in the long run, the available evidence suggests that these four different knee prostheses indicate no difference in other clinical outcomes after TKA with extended follow-up.

Availability of data and materials

Some or all data and models used in the study are available from the corresponding author on request. All codes generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81974347), the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (No.2021M702351), and the Medical Science and Technology Program of Health Commission of Sichuan Province of China (No. 21PJ040).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Sun K, Wu Y, Wu L, Shen B. Comparison of clinical outcomes among total knee arthroplasties using posterior-stabilized, cruciate-retaining, bi-cruciate substituting, bi-cruciate retaining designs: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Chin Med J 2023;136:1817–1831. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002183

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

References

- 1.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380:2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73:1323–1330. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr AJ, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price AJ, Arden NK, Judge A, et al. Knee replacement. Lancet 2012; 379:1331–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60752-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dall’Oca C, Ricci M, Vecchini E, Giannini N, Lamberti D, Tromponi C, et al. Evolution of TKA design. Acta Biomed 2017; 88:17–31. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i2-S.6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White PB, Ranawat AS. Patient-specific total knees demonstrate a higher manipulation rate compared to “off-the-shelf implants”. J Arthroplasty 2016; 31:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angerame MR, Holst DC, Jennings JM, Komistek RD, Dennis DA. Total knee arthroplasty kinematics. J Arthroplasty 2019; 34:2502–2510. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaishya R, Agarwal AK, Vijay V. Extensor mechanism disruption after total knee arthroplasty: a case series and review of literature. Cureus 2016; 8:e479.doi: 10.7759/cureus.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takubo A, Ryu K, Iriuchishima T, Tokuhashi Y. Comparison of muscle recovery following bi-cruciate substituting versus posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty in the Asian population. J Knee Surg 2017; 30:725–729. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1597977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biazzo A, D’Ambrosi R, Staals E, Masia F, Izzo V, Verde F. Early results with a bicruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty: a match-paired study. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2021; 31:785–790. doi: 10.1007/s00590-020-02834-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Ioannidis JP. Demystifying trial networks and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2013; 346:f2914.doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leucht S, Chaimani A, Cipriani AS, Davis JM, Furukawa TA, Salanti G. Network meta-analyses should be the highest level of evidence in treatment guidelines. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2016; 266:477–480. doi: 10.1007/s00406-016-0715-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salanti G, Del Giovane C, Chaimani A, Caldwell DM, Higgins JPT. Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014; 9:e99682.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tikka C, Verbeek J, Ijaz S, Hoving JL, Boschman J, Hulshof C, et al. Quality of reporting and risk of bias: a review of randomised trials in occupational health. Occup Environ Med 2021; 78:691–696. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-107038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: Comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14:45.doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Del Giovane C, Chaimani A, Caldwell DM, Salanti G. Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. Value Health 2014; 17:A324.doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Béliveau A, Boyne DJ, Slater J, Brenner D, Arora P. BUGSnet: an R package to facilitate the conduct and reporting of Bayesian network meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19:196.doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu-Kang T. Node-splitting generalized linear mixed models for evaluation of inconsistency in network meta-analysis. Value Health 2016; 19:957–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shim SR, Kim SJ, Lee J, Rücker G. Network meta-analysis: application and practice using R software. Epidemiol Health 2019; 41:e2019013.doi: 10.4178/epih.e2019013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neupane B, Richer D, Bonner AJ, Kibret T, Beyene J. Network meta-analysis using R: a review of currently available automated packages. PLoS One 2014; 9:e115065.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumann F, Krutsch W, Worlicek M, Kerschbaum M, Zellner J, Schmitz P, et al. Reduced joint-awareness in bicruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty compared to cruciate-sacrificing total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018; 138:273–279. doi: 10.1007/s00402-017-2839-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maruyama S, Yoshiya S, Matsui N, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Functional comparison of posterior cruciate-retaining versus posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19:349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Boom LGH, Brouwer RW, van den Akker-Scheek I, Reininga IHF, de Vries AJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al. No difference in recovery of patient-reported outcome and range of motion between cruciate retaining and posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Knee Surg 2020; 33:1243–1250. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1693023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baumann F, Bahadin Ö, Krutsch W, Zellner J, Nerlich M, Angele P, et al. Proprioception after bicruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty is comparable to unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017; 25:1697–1704. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen JC, Brothers J, Stoddard GJ, Anderson MB, Pelt CE, Gililland JM, et al. Higher frequency of reoperation with a new bicruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475:62–69. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4812-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavoie F, Al-Shakfa F, Moore JR, Mychaltchouk L, Iguer K. Postoperative stiffening after bicruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2018; 31:453–458. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1604145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scarvell JM, Perriman DM, Smith PN, Campbell DG, Bruce WJM, Nivbrant B. Total knee arthroplasty using bicruciate-stabilized or posterior-stabilized knee implants provided comparable outcomes at 2 years: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled, clinical trial of patient outcomes. J Arthroplasty 2017; 32:3356–3363. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward TR, Burns AW, Gillespie MJ, Scarvell JM, Smith PN. Bicruciate-stabilised total knee replacements produce more normal sagittal plane kinematics than posterior-stabilised designs. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93B:907–913. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.93b7.26208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho KY, Kim KI, Song SJ, Bae DK. Does cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty show better quadriceps recovery than posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty? - Objective Measurement with a Dynamometer in 102 Knees. Clin Orthop Surg 2016; 8:379–385. doi: 10.4055/cios.2016.8.4.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark CR, Rorabeck CH, MacDonald S, MacDonald D, Swafford J, Cleland D. Posterior-stabilized and cruciate-retaining total knee replacement: a randomized study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; 392:208–212. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harato K, Bourne RB, Victor J, Snyder M, Hart J, Ries MD. Midterm comparison of posterior cruciate-retaining versus-substituting total knee arthroplasty using the Genesis II prosthesis - a multicenter prospective randomized clinical trial. Knee 2008; 15:217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Öztürk A, Akalin Y, Çevik N, Otuzbir A, Özkan Y, Dostabakan Y. Posterior cruciate-substituting total knee replacement recovers the flexion arc faster in the early postoperative period in knees with high varus deformity: a prospective randomized study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2016; 136:999–1006. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanzer M, Smith K, Burnett S. Posterior-stabilized versus cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty - Balancing the gap. J Arthroplasty 2002; 17:813–819. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.34814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Den Boom LGH, Brouwer RW, Van Den Akker-Scheek I, Bulstra SK, van Raaij JJAM. Retention of the posterior cruciate ligament versus the posterior stabilized design in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2009; 10:119.doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Victor J, Banks S, Bellemans J. Kinematics of posterior cruciate ligament-retaining and -substituting total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomised outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005; 87B:646–655. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.87b5.15602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beaupre LA, Sharifi B, Johnston DWC. A randomized clinical trial comparing posterior cruciate-stabilizing vs posterior cruciate-retaining prostheses in primary total knee arthroplasty: 10-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty 2017; 32:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bin Abd Razak HR, Pang HN, Yeo SJ, Tan MH, Lo NN, Chong HC. Joint line changes in cruciate-retaining versus posterior-stabilized computer-navigated total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013; 133:853–859. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carvalho LH, Jr, Temponi EF, Soares LFM, Gonçalves MJB. Relationship between range of motion and femoral rollback in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2014; 48:1–5. doi: 10.3944/aott.2014.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catani F, Leardini A, Ensini A, Cucca G, Bragonzoni L, Toksvig-Larsen S, et al. The stability of the cemented tibial component of total knee arthroplasty: posterior cruciate-retaining versus posterior-stabilized design. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19:775–782. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen JY, Lo NN, Chong HC, Pang HN, Tay DKJ, Chin PL, et al. Cruciate retaining versus posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty after previous high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23:3607–3613. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3259-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conditt MA, Noble PC, Bertolusso R, Woody J, Parsley BS. The PCL significantly affects the functional outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19: (7 Suppl 2): 107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inui H, Taketomi S, Yamagami R, Kono K, Kawaguchi K, Takagi K, et al. Comparison of intraoperative kinematics and their influence on the clinical outcomes between posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty and bi-cruciate stabilized total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2020; 27:1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolisek FR, McGrath MS, Marker DR, Jessup N, Seyler TM, Mont MA, et al. Posterior-stabilized versus posterior cruciate ligament-retaining total knee arthroplasty. Iowa Orthop J 2009; 29:23–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laidlaw MS, Rolston LR, Bozic KJ, Ries MD. Assessment of tibiofemoral position in total knee arthroplasty using the active flexion lateral radiograph. Knee 2010; 17:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumoto T, Muratsu H, Kubo S, Matsushita T, Kurosaka M, Kuroda R. Intraoperative soft tissue balance reflects minimum 5-year midterm outcomes in cruciate-retaining and posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27:1723–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moro-Oka TA, Muenchinger M, Canciani JP, Banks SA. Comparing in vivo kinematics of anterior cruciate-retaining and posterior cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007; 15:93–99. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mugnai R, Digennaro V, Ensini A, Leardini A, Catani F. Can TKA design affect the clinical outcome? Comparison between two guided-motion systems. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22:581–589. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sando T, McCalden RW, Bourne RB, MacDonald SJ, Somerville LE. Ten-year results comparing posterior cruciate-retaining versus posterior cruciate-substituting total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30:210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song SJ, Park CH, Bae DK. What to know for selecting cruciate-retaining or posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg 2019; 11:142–150. doi: 10.4055/cios.2019.11.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vermesan D, Trocan I, Prejbeanu R, Poenaru DV, Haragus H, Gratian D, et al. Reduced operating time but not blood loss with cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty. J Clin Med Res 2015; 7:171–175. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2048w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoshiya S, Matsui N, Komistek RD, Dennis DA, Mahfouz M, Kurosaka M. In vivo kinematic comparison of posterior cruciate-retaining and posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasties under passive and weight-bearing conditions. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Troelsen A, Ingelsrud LH, Thomsen MG, Muharemovic O, Otte KS, Husted H. Are there differences in micromotion on radiostereometric analysis between bicruciate and cruciate-retaining designs in TKA? A randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2020; 478:2045–2053. doi: 10.1097/corr.0000000000001077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nisar S, Ahmad K, Palan J, Pandit H, van Duren B. Medial stabilised total knee arthroplasty achieves comparable clinical outcomes when compared to other TKA designs: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the current literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022;30:638-651. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06358-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang C, Liu Z, Wang Y, Bian Y, Feng B, Weng X. Posterior cruciate ligament retention versus posterior stabilization for total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0147865.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bercik MJ, Joshi A, Parvizi J. Posterior cruciate-retaining versus posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chaudhary R, Beaupré LA, Johnston DW. Knee range of motion during the first two years after use of posterior cruciate-stabilizing or posterior cruciate-retaining total knee prostheses. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90:2579–2586. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.G.00995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li N, Tan Y, Deng Y, Chen L. Posterior cruciate-retaining versus posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22:556–564. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Longo UG, Ciuffreda M, Mannering N, D’Andrea V, Locher J, Salvatore G, et al. Outcomes of posterior-stabilized compared with cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2018; 31:321–340. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kalaai S, Scholtes M, Borghans R, Boonen B, van Haaren E, Schotanus M. Comparable level of joint awareness between the bi-cruciate and cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty with patient-specific instruments: a case-controlled study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2020; 28:1835–1841. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05613-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kono K, Inui H, Tomita T, Yamazaki T, Taketomi S, Sugamoto K, et al. Bicruciate-stabilised total knee arthroplasty provides good functional stability during high-flexion weight-bearing activities. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2019; 27:2096–2103. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schimmel JJP, Defoort KC, Heesterbeek PJC, Wymenga AB, Jacobs WCH, van Hellemondt GG. Bi-cruciate substituting design does not improve maximal flexion in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96:e81.doi: 10.2106/jbjs.M.00277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data and models used in the study are available from the corresponding author on request. All codes generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on request.