Abstract

Background:

This study aimed to systematically review the evidence of drug-coated balloon used in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction and compared with using drug-eluting stent in terms of clinical and angiographic outcomes for a relatively long follow-up period.

Methods:

Electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library were used to search for the information of each study. A total of 8 studies involving 1310 patients were included in this meta-analysis.

Results:

During a median follow-up duration of 12 months (range 3-24 months), there were no statistical differences between the drug-coated balloon and drug-eluting stent group in terms of a major adverse cardiovascular event (odds ratio = 1.07; P = .75; 95% CI: 0.72-1.57), all-cause death (odds ratio = 1.01; P = .98; 95% CI = 0.56-1.82), cardiac death (odds ratio = 0.85, P = .65; 95% CI = 0.42-1.72), target lesion revascularization (odds ratio = 1.72; P = .09; 95% CI: 0.93-3.19), recurrent myocardial infarction (odds ratio = 0.89, P = .76; 95% CI: 0.44-1.83), and thrombotic event (odds ratio = 1.10; P = .90; 95% CI: 0.24-5.02). Drug-coated balloon was not linked with risk of late lumen loss compared with drug-eluting stent (mean difference = −0.06 mm; P = .42; 95% CI: −0.22-0.09 mm). However, there was a higher incidence of target vessel revascularization noted in the drug-coated balloon group compared with the drug-eluting stent group (odds ratio = 1.88; P = .02; 95% CI: 1.10-3.22). The subgroup analysis stratified by different study types and ethnicities showed there were no significant differences between the 2 groups.

Conclusions:

Using drug-coated balloon might serve as a potential alternative strategy for patients with acute myocardial infarction because of the similar clinical and angiographic outcomes compared with using drug-eluting stent; nevertheless, the issue of target vessel revascularization should be more focused on. Larger and more representative studies are needed in the future.

Keywords: Drug-coated balloon, drug-eluting stent, acute myocardial infarction, major adverse cardiovascular event

Highlights

The high-quality evidence of drug-coated balloon utilized in patients with acute myocardial infarction is still lacking.

The present meta-analysis was performed to determine the effectiveness and safety of drug-coated balloon used in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction in terms of clinical and angiographic outcomes for a relatively long follow-up period.

Using drug-coated balloon would be an alternative strategy for using drug-eluting stent in patients with acute myocardial infarction since no significant differences in clinical and angiographic outcomes were noted in our meta-analysis.

Introduction

The second-generation drug-eluting stent (DES) has been the safest and most effective standard management during the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) transition process over 40 years, superior to the plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) and bare metal stent (BMS) implantation in the long term.1-4 Despite this, DES implanting seems to still arise a number of adverse events in practical procedures, for instance, in-stent restenosis (ISR) and late-stent thrombosis as well as bleeding caused by the long-term duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).5,6 The drug-coated balloon (DCB) currently demonstrated its effect in the treatment of ISR,7,8 which is recommended by the 2018 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for myocardial revascularization as the evidence of class I.9 In addition to ISR, DCB has been used in other circumstances, such as small vessel lesions,10,11 bifurcation lesion,12 high bleeding risk,13 and acute myocardial infarction (AMI).14 Recently, Megaly et al15 performed a meta-analysis of short-term clinical and angiographic outcomes of patients with DCB vs. DES in AMI, indicating that there was no statistical difference between the 2 groups.15 However, larger sized, wider representative and longer-term follow-up studies are further warranted to assess the effectiveness of DCB in patients with AMI. Therefore, this study intends to search the online database for comparative studies on DCB and DES in the intervention procedure of AMI and to carry out an updated meta-analysis to evaluate the clinical efficacy of DCB compared with DES in the treatment of AMI.

Methods

The present meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA).16

Search Strategy

We performed a systematic computerized search via Pubmed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library from April 2002 to October 2022 using the following keywords “drug-eluting balloon,” “DEB,” “drug-coated balloon,” “DCB,” “paclitaxel-coated balloon,” and “acute myocardial infarction.” We screened the eligible studies by browsing titles, abstracts, and full texts. We deleted reviews, case reports, letters, comments, and others. The specific references were also screened to avoid missing any research.

Study Selection and Data Collection

We enrolled in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational cohort studies comparing DCB with DES in the treatment of AMI. In the DCB arm, we excluded those cases with preferred choice of DCB followed by a bailout strategy, defined as stent application to remedy residual stenosis or dissection. The hybrid strategy defined as a combination utilizes of DCB and DES was not allowed in the DCB group.

The eligible data were selected independently by 2 researchers (F.Z. and X.B.), and any disagreement was determined by a third one (J.J.) finally. The ethics approval and patient consent were not required for this analysis. The baseline characteristics of the included studies involved age, sex, and history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and smoking. The quality of included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk assessment tool for RCTs and The Newcastle Ottawa Scale for observational studies.

Clinical and Angiographic Outcomes

The clinical outcomes in this meta-analysis are major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) including all-cause death, cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), target lesion revascularization (TLR), and target vessel revascularization (TVR). The exact definition of MACE in each study is shown in Table 1. The angiographic outcomes included late lumen loss (LLL) defined as the minimal lumen diameter (MLD) post-procedural minus the MLD at follow-up time measured by quantitative coronary analysis (QCA).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

| Study (First Author, Year) | Study Type | Numbers of DCB/DES Group | Balloon/Stent Type | Region (Number of Centers) | Follow-up Time (Months) | Enrolment Dates | STEMI/NSTEMI | Bailout Stenting (%) | Angiographic Outcomes | MACE Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nijhoff, 2015 | Observational | 40/45 | DIOR II (Eurocor GmbH, Bonn, Germany)/Paclitaxel (Taxus Liberté, Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass, USA) | The Netherlands (2) | 12 | NA | STEMI | 10 | LLL, binary restenosis, MLD, diameter stenosis | Death, any MI and TVR |

| Gobić, 2017 | RCT | 38/37 | Sequent Please (B.Braun, Melsungen, Germany)/Sirolimus (Biomime, Meril Life Sciences, Vapi, India) | Croatia (1) | 6 | March 2014-January 2015 | STEMI | 7.3 | LLL, MLD | Cardiovascular death, reinfarction, TLR, and stent thrombosis |

| Fang, 2018 | Observational | 75/42 | NA | Taiwan (1) | 12 | November 2011-December 2015 | STEMI/NSTEMI with ISR | NA | NA | TLR, TVR, recurrent MI, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality |

| Scheller, 2019 | RCT | 85/111 | Sequent Please (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany)/56% with BMS, 44% with DES | Germany (5) | 9 | December 2012-January 2017 | NSTEMI | 15 | NA | All-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularization, stroke, or PCI at other vessels |

| Zhang, 2020 | Observational | 180/200 | NA | China (1) | 3 | January 2016- May 2019 | STEMI/NSTEMI | 1.1 | NA | cardiac death, non-fatal MI, TVR, and in-stent thrombosis |

| Tan, 2020 | Observational | 56/212 | Sequent Please (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany)/(Endeavor Resolute, Metronic company) or (Firebird2, Microport company) | China (1) | 24 | March 2016-March 2018 | STEMI/NSTEMI of SVD | NA | MLD, diameter stenosis, LLL | all-cause death, non-fatal MI, TLR, or TVR |

| Hao, 2021 | RCT | 38/42 | Yinyi Biotech BingoDrug Coated Balloon (Liaoning, China) | China (1) | 12 | January 2018- December 2019 | STEMI | 9.5 | LLL, restenosis | NA |

| Niehe, 2022 | RCT | 56/53 | Pantera Lux paclitaxel-coated balloon (Biotronik)/sirolimus-eluting stent (Biotronik) | The Netherlands (1) | 24 | October 2014-November 2017 | STEMI | 18 | NA | Cardiac death, recurrent MI, and ischemia-driven TLR |

DCB, drug-coating balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent; LLL, late lumen loss; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; MLD, minimal lumen diameter; NA, not available; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; SVD, small vessel coronary artery disease; TLR, target lesion revascularization; TVR, target vessel revascularization.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted a statistical analysis with Review Manager software (Version 5.3.5. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). Odds ratios with 95% CIs were presented as summary statistics. The OR estimations and CI values in fixed effects and random effects models were calculated according to the Mantel–Haenszel (M–H) method. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by I 2 statistics. The I 2 statistic values <25%, 25%-50%, and >50% were considered as low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively. The random effects model meta-analysis was used if a high degree of heterogeneity exists, if not the fixed effects model meta-analysis would be chosen. We performed sensitivity analysis by deleting each study that might be the cause of high heterogeneity. When a P value was less than .05, it was considered significant statistically. The funnel plot was used to assess potential publication bias.

Results

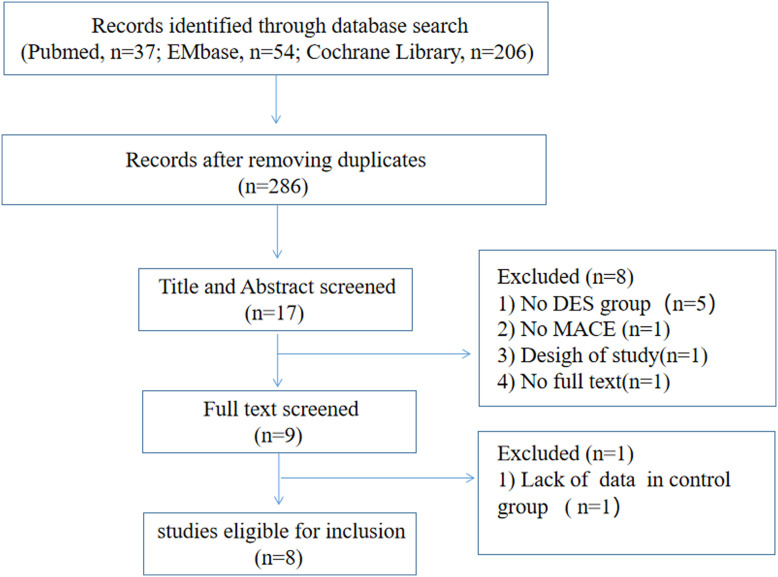

A total of 8 studies (1310 patients; DCB group, n = 568; DES group, n = 742) were included in this meta-analysis (Figure 1). The characteristics of these 8 studies are described in Table 1, and the baseline information of those is described in Table 2. Only 4 studies are RCTs and another 4 studies are observational trials. Most of the studies are single-centered except EPCAD study which includes 5 centers of German. The population of this meta-analysis is derived from European and Asian countries. The median follow-up time was 12 months ranging from 3 months to 24 months. We compared the outcomes of DCB with the second-generation DES.10,12,14 Bailout stenting procedures in the DCB group ranged from 1.1% to 18%, with 6 studies whose bailout stenting data are available.

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the search strategy for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients in Each Study Included. DCB, drug-coating balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent

| Study |

Age | Male (%) | Diabetes (%) | Dyslipidemia (n, %) | Hypertension (n, %) | Smoking (n, %) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCB | DES | DCB | DES | DCB | DES | DCB | DES | DCB | DES | DCB | DES | |

| Nijhoff, 2015 | 57.9 ± 10.0 | 55.9 ± 9.7 | 26 (65) | 41 (83.7) | 5 (12.5) | 2 (4.1) | 7 (17.5) | 16 (32.7) | 14 (35.0) | 15 (30.6) | 21 (52.5) | 28 (57.1) |

| Gobić, 2017 | 56.6 ± 13.2 | 54.3 ± 10.6 | 27 (71.1) | 27 (73) | 2 (5.3) | 4 (10.8) | 4 (10.5) | 7 (18.9) | 12 (31.6) | 13 (35.1) | 16 (42.1) | 21 (56.8) |

| Fang, 2018 | 67.5 ± 11.6 | 69.9 ± 11.0 | 46 (61.3) | 46 (61.3) | 58 (77.3) | 26 (61.9) | 39 (52.0) | 23 (54.8) | 64 (85.3) | 37 (88.1) | 25 (33.3) | 16 (38.1) |

| Scheller, 2019 | 66.0 ± 11.4 | 67.0 ± 13.1 | 69 (66.3) | 72 (67.9) | 28 (26.9) | 38 (35.8) | 52 (50.0) | 48 (45.3) | 82 (78.7) | 93 (87.7) | 35 (33.7) | 43 (40.6) |

| Zhang, 2020 | 66.4 ± 12.3 | 63.1 ± 18.2 | 152 (76.0) | 122 (67.8) | 25 (13.9) | 40 (20.0) | NA | NA | 76 (42.2) | 70 (35.0) | 100 (55.6) | 108 (54.0) |

| Tan, 2020 | 64.96 ± 8.82 | 62.39 ± 9.91 | 34 (60.7) | 139 (65.6) | 18 (32.14) | 58 (26.85) | NA | NA | 21 (37.50) | 75 (34.72) | 29 (51.78) | 94 (43.51) |

| Hao, 2021 | 59 ± 11 | 56 ± 11 | 30 (75) | 35 (82) | 10 (28) | 15 (35) | NA | NA | 8 (22) | 8 (22) | 24 (28) | 28 (31) |

| Niehe, 2022 | 57.4 ± 9.2 | 57.3 ± 8.3 | 52 (87) | 52 (87) | 8 (13) | 4 (7) | 10 (17) | 8 (13) | 18 (30) | 19 (32) | 36 (60) | 30 (50) |

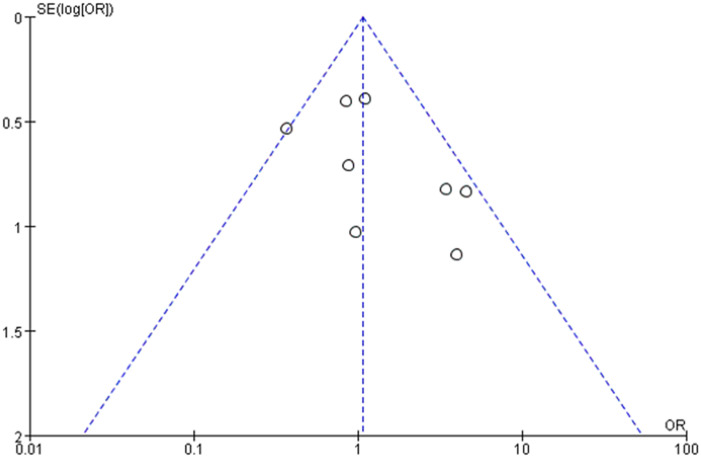

Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

The funnel plot for MACE of this meta-analysis was assessed as symmetrical visually with an approximately equal number of studies on both sides of the vertical axis (Supplementary Figure 1 in the Data Supplement). The results of Cochrane risk assessment for RCTs and Newcastle Ottawa Scale for observational studies were illustrated by Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1 in the Data Supplement.

Supplementary Figure 1.

The funnel plot for MACE in this meta-analysis.

Supplementary Figure 2.

The quality assessment for RCTs in this meta-analysis.

Supplementary Table 1.

The Quality Assessment for Observational Studies in this Meta-Analysis

| Study |

Selection | Comparability | Outcomes | Score |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5A | 5B | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Nijhoff (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Fang (2018) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Zhang (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 8 |

| Tan (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

1, representativeness of the exposed cohort; 2, selection of the nonexposed cohort; 3, ascertainment of exposure; 4, Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of study; 5A, Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design; 5B, comparability of cohorts on the basis of the analysis; 6, assessment of outcome; 7, follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur; 8, adequacy of follow-up of cohorts.

Y, yes; N, no.

Clinical and Angiographic Outcomes

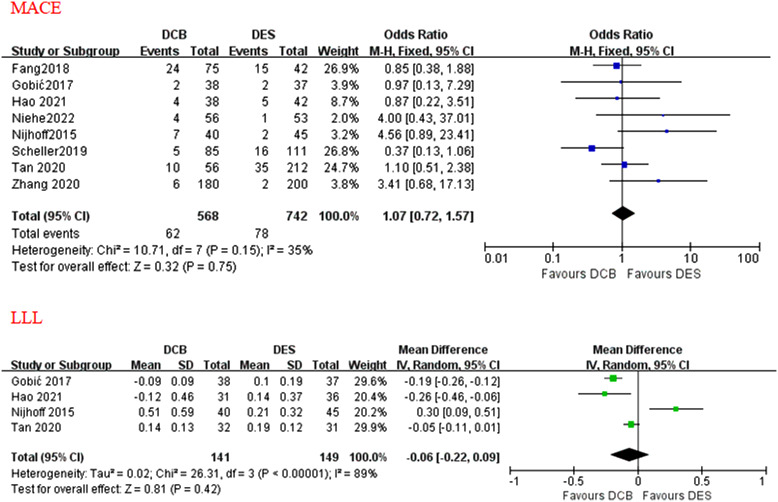

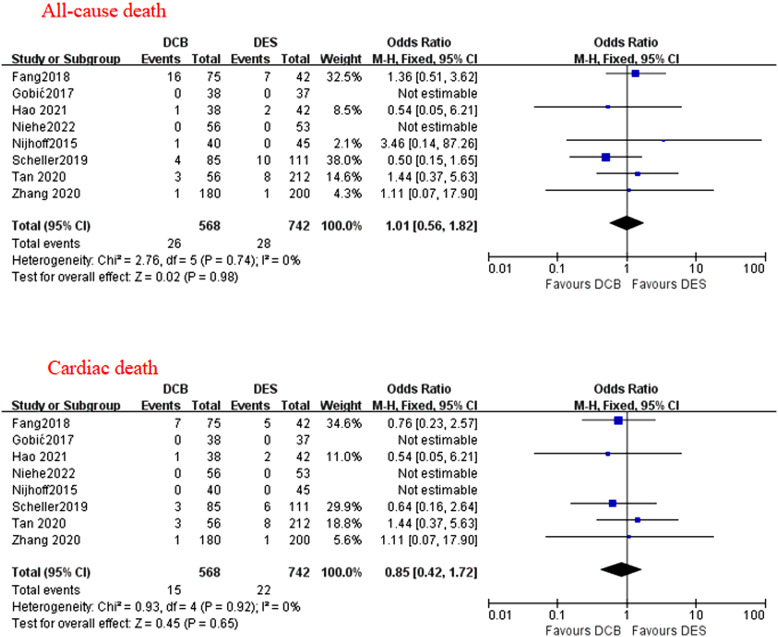

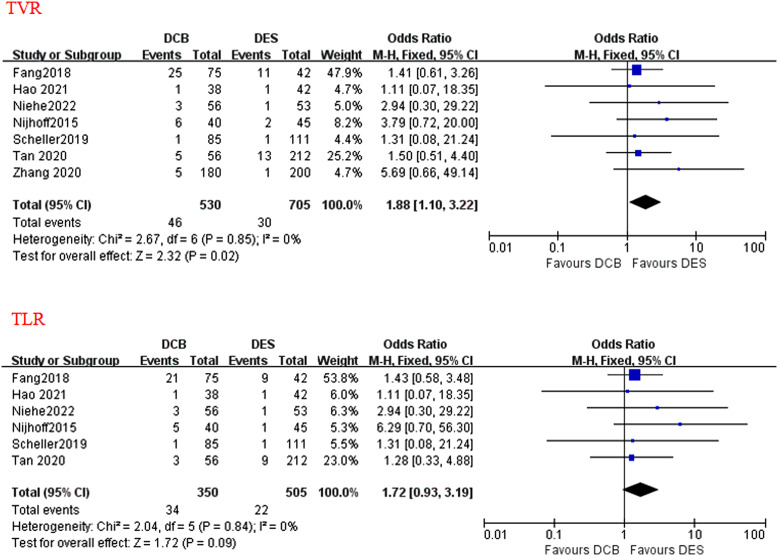

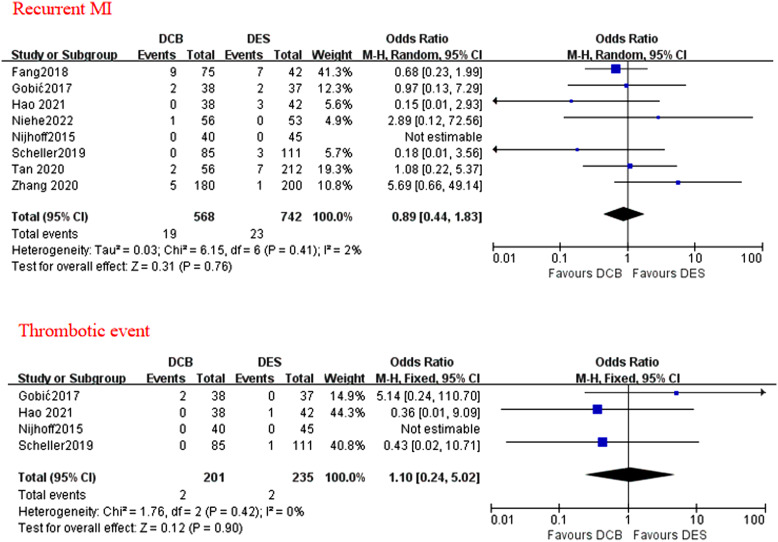

A total of 8 studies reported data on MACE, cardiac death, and recurrent MI. All-cause death was assessed in all the 8 studies, although a few studies did not report non-cardiac death. Target vessel revascularization (including TLR) was assessed in 7 out of 8 studies. Target vessel revascularization was assessed in 6 out of 7 studies, thrombotic event was assessed in 4 out of 8 studies. During a median follow-up duration of 12 months (range 3-24 months), no statistically different effects were found between the applications of DCB and DES in terms of MACE (OR = 1.07; P = .75; 95% CI: 0.72-1.57; Figure 2), all-cause death (OR = 1.01; P = .98; 95% CI = 0.56-1.82; Figure 3), cardiac death (OR = 0.85; P = .65; 95% CI = 0.42-1.72; Figure 3), TLR (OR = 1.72; P = .09; 95% CI: 0.93-3.19; Figure 4), recurrent MI (OR = 0.89, P = .76; 95% CI: 0.44-1.83; Figure 5), and thrombotic event (OR = 1.10; P = .90; 95% CI: 0.24-5.02; Figure 5). However, there was a higher incidence of TVR noted in the application of DCB compared with DES (OR = 1.88; P = .02; 95% CI: 1.10-3.22; Figure 4). The heterogeneity among the 8 studies (I 2 = 35%) was displayed when we pooled ORs of each study concerned with MACE. The sensitivity analysis showed deleting any one of the studies did not change the tendency in terms of MACE, all-cause death, cardiac death, TLR, recurrent MI, and thrombotic event except for TRV. When either Nijhoff’s study or Zhang’s study was deleted, no statistically significant difference was noted between DCB and DES groups.

Figure 2.

The forest plots of clinical and angiographic outcomes (MACE and LLL) compared DCB with DES in patients with AMI. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent; LLL, late lumen loss; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event.

Figure 3.

The forest plots of the clinical outcomes of all-cause death and cardiac death compared DCB with DES in patients with AMI. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent.

Figure 4.

The forest plots of the clinical outcomes of TVR and TLR compared DCB with DES in patients with AMI. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent; TLR, target lesion revascularization; TVR, target vessel revascularization.

Figure 5.

The forest plots of the clinical outcomes of recurrent MI and thrombotic events compared DCB with DES in patients with AMI. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent.

During a median follow-up duration of 12 months, DCB strategy was not associated with LLL compared with DES implanting (MD = −0.06 mm, 95% CI = −0.22-0.09 mm, Figure 2).

Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analysis of outcomes (MACE, all-cause death, cardiac death, TVR, TLR, and recurrent MI) was stratified by the type of RCT or observational study and by the population of European or Asian. The results showed that there were still no significant differences between 2 groups with either RCTs or observational studies as well as either Europeans or Asians (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis of outcomes (MACE, all-cause death, cardiac death, TVR, TLR, recurrent MI) compared DCB with DES in patients with AMI. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent; MI, myocardial infarction; TLR, target lesion revascularization; TVR, target vessel revascularization.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis of 8 clinical trials including 1310 patients with AMI undergoing PCI, we compared the clinical outcomes of DCB versus DES used in the operation. The principal findings were as followed: In terms of clinical and angiographic outcomes, performing PCI with DCB only strategy had no significant difference associated with doing that with DES strategy. Furthermore, our subgroup analysis demonstrated different study types and populations did not alter the stability of results.

Role of Drug-Eluting Stent in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

The new generation DES rather than BMS or POBA has become the cornerstone management during PCI for its advantages in reducing elastic recoil, flow-limiting dissections, and restenosis caused by cellular proliferation.17,18 Despite this, the patients treated with DES are still at risk for late-stent thrombosis, ISR, and a prolonged DAPT postoperative.19 Moreover, PCI with DES strategy is also limited in tackling complex lesions such as long, bifurcated, calcified, or chronic total occlusions (CTO) lesions.19

Role of Drug-Coated Balloon in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Drug-coated balloon, an attractive alternative therapy of DES, has played a vital role in the treatment of ISR and obtained a recommendation of class IA.9 However, using DCB in de novo lesions such as bifurcation lesions, and small vessel disease (SVD) has been getting increasing evidences with regard to recent multiple trials and meta-analyses.12-20 In recent years, DCB strategy also has been tried to be applied in the treatment of ACS, even AMI. Ho et al21 in Singapore first reported a case of STEMI treated with DCB. Their subsequent study found that patients with AMI treated with DCB only had a low rate of ischemic events within 30 days, which demonstrated that DCB was safe and feasible.22 In 2015, Nijhoff et al23 reported the therapeutic effect of the DEB-only strategy compared with DES strategy in primary PCI, indicating that DEB might increase risks of LLL, restenosis, and MACE compared to DES.23 DEB-only strategy was still recommended as a valid alternative for DES strategy since no acute or late thrombotic events occurred in the trial.23 In 2017, Gobić et al24 published their results of the first RCT for DCB vs. DES in the primary PCI setting, providing evidence for the positive efficiency of DCB-only strategy in further reduction of MACE and LLL. In 2018, Fang et al25 claimed that DCB is an alternative strategy to AMI with ISR due to its acceptable low clinical outcomes similar to DES. A recent meta-analysis performed by Megaly et al15 included 4 studies that drew a conclusion that DCB was associated with similar short-time outcomes (MACE, all-cause mortality, cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), TLR) compared with DES. Nevertheless, its findings were limited to a small sample, short follow-up duration, and European only. REVELATION trial, a prospective randomized control trial planning for 5-year follow-up, displayed no significant differences between the DCB and DES groups in terms of fractional flow reserve in a 9-month follow-up.26 Then they recently brought out that DCB angioplasty was inferior to a DES strategy in the setting of STEMI for similar MACE in the 2-year follow-up.27 Tan et al28 reported there were no differences in 24-month MACE and LLL noted between the DCB group and DES group in a retrospective research enrolling 268 patients of AMI with de novo small coronary artery disease.28 Besides, Zhang et al29 and Hao et al30 found that the incidences of MACE rate were no significant differences between the DCB and the stent group during 3 months and 1 year respectively in the Chinese population.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Our meta-analysis integrated previous clinical trials, supporting that there were no significant different effects between applications of DCB and DES with respect to MACE as well as LLL either in European or Asian populations. The higher incidence of TVR after DCB angioplasty compared with DES implantation was found, which might be the obstacle to the widespread use of DCB for acute coronary lesions.

Study Limitations

Several limitations in this meta-analysis are as followed. First, the significant heterogeneity between included studies should be taken into account, although we have attempted to tackle this item with sensitive analysis and use a random effective model on occasion. Second, 3 observational studies included may bring selective bias. Third, some other clinical events such as bleeding were not available. Fourth, the inconsistent definitions of MACE must be noted. Last, the new sirolimus-coated balloons were not used in the included studies, even though there is a potential alternative to the paclitaxel-coated balloons.31

Conclusion

In patients with AMI, PCI with DCB is not statistically associated with LLL, a high risk of MACE and all-cause death, cardiac death, recurrent MI, TLR, and thrombotic event compared with DES in a median 1-year follow-up. Drug-coated balloon appears as an attractive alternative to DES in patients with AMI, but TVR risk at follow-up time should be concentrated on. Therefore, more long-term and large-sample clinical trials are still warranted.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: As all data analyzed in this study were from previous published studies, no ethical approval and patient consent are required.

Peer-review: Internally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Z.F.: Conception, Data Collection and/or Processing, Analysis, Writing; J.J.: Supervision, Materials, Data Collection and/or Processing; S.H.: Supervision, Analysis and/or Interpretation, Literature Review; N.L., Data Collection and/or Processing, Literature Review; B.X.: Design, Supervision, Fundings, Critical Review.

Declaration of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the Social Development Project of Yangzhou (Grant No. YZ2021060).

References

- 1. Ibánez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2017;70(12):1082. ( 10.1016/j.rec.2017.11.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127(4):e362 e425. ( 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McKavanagh P, Zawadowski G, Ahmed N, Kutryk M. The evolution of coronary stents. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2018;16(3):219 228. ( 10.1080/14779072.2018.1435274) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palmerini T, Benedetto U, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Long-term safety of drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: evidence from a comprehensive network meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(23):2496 2507. ( 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vlachojannis GJ, Smits PC, Hofma SH, et al. Biodegradable polymer Biolimus-eluting stents versus durable polymer everolimus-eluting stents in patients with coronary artery disease: final 5-year report from the Compare II trial (abluminal biodegradable polymer Biolimus-eluting stent versus durable polymer everolimus-eluting stent). JACC Cardiovasc Intv. 2017;10(12):1215 1221. ( 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.02.029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Madhavan MV, Kirtane AJ, Redfors B, et al. Stent-related adverse events >1 year after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(6):590 604. ( 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.058) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stella PR, Belkacemi A, Waksman R, et al. The Valentines Trial: results of the first one week worldwide multicentre enrolment trial, evaluating the real world usage of the second generation DIOR paclitaxel drug-eluting balloon for in-stent restenosis treatment. EuroIntervention. 2011;7(6):705 710. ( 10.4244/EIJV7I6A113) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Indermuehle A, Bahl R, Lansky AJ, et al. Drug-eluting balloon angioplasty for in-stent restenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Heart. 2013;99(5):327 333. ( 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302945) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J 2019;40(2):87 165. ( 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tang Y, Qiao S, Su X, et al. Drug-coated balloon versus drug-eluting stent for small-vessel disease: the RESTORE SVD China randomized trial. JACC Cardiovasc Intv. 2018;11(23):2381 2392. ( 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.09.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow MA, et al. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): an open-label randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10150):849 856. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31719-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corballis NH, Paddock S, Gunawardena T, Merinopoulos I, Vassiliou VS, Eccleshall SC. Drug coated balloons for coronary artery bifurcation lesions: A systematic review and focused meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0251986. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0251986) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rissanen TT, Uskela S, Eränen J, et al. Drug-coated balloon for treatment of de-novo coronary artery lesions in patients with high bleeding risk (DEBUT): a single-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):230 239. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31126-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scheller B, Ohlow MA, Ewen S, et al. Bare metal or drug-eluting stent versus drug-coated balloon in non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the randomised PEPCAD NSTEMI trial. EuroIntervention. 2020;15(17):1527 1533. ( 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00723) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Megaly M, Buda KG, Xenogiannis I, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of short-term outcomes with drug-coated balloons vs. stenting in acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2021;36(4):481 489. ( 10.1007/s12928-020-00713-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. ( 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Waksman R, Pakala R. Drug-eluting balloon: the comeback kid? Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(4):352 358. ( 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.873703) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, et al. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(23):1773 1780. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa012843) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chaddad R, El-Mokdad R, Lazar L, Cortese B. DCBs as an adjuvant tool to des for very complex coronary lesions. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2022;23(1):13. ( 10.31083/j.rcm2301013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Megaly M, Buda K, Saad M, et al. Outcomes with Drug-Coated Balloons vs. Drug-Eluting Stents in Small-Vessel coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Revasc Med Incl Mol Interv. 2022;35:76 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ho HH, Ong PJ, Jafary FH. "First-in-man" report of successful use of drug-coated balloon angioplasty in primary percutaneous coronary intervention to treat a patient with 2 discrete ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2016;214:19 20. ( 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.03.097) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ho HH, Tan J, Ooi YW, et al. Preliminary experience with drug-coated balloon angioplasty in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(6):311 314. ( 10.4330/wjc.v7.i6.311) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nijhoff F, Agostoni P, Belkacemi A, et al. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention by drug-eluting balloon angioplasty: the nonrandomized fourth arm of the DEB-AMI (drug-eluting balloon in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction) trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86(suppl 1):S34 S44. ( 10.1002/ccd.26060) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gobić D, Tomulić V, Lulić D, et al. Drug-coated balloon versus drug-eluting stent in primary percutaneous coronary intervention: A feasibility study. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354(6):553 560. ( 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.07.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fang CY, Fang HY, Chen CJ, Yang CH, Wu CJ, Lee WC. Comparison of clinical outcomes after drug-eluting balloon and drug-eluting stent use for in-stent restenosis related acute myocardial infarction: a retrospective study. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4646. ( 10.7717/peerj.4646) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vos NS, Fagel ND, Amoroso G, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty versus drug-eluting stent in acute myocardial infarction: the REVELATION randomized trial. JACC Cardiovasc Intv. 2019;12(17):1691 1699. ( 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.04.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Niehe SR, Vos NS, Van Der Schaaf RJ, et al. Two-year clinical outcomes of the REVELATION study: sustained safety and feasibility of paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty versus drug-eluting stent in acute myocardial infarction. J Invasive Cardiol. 2022;34(1):E39-E42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tan Q, Wang Q, Yang H, Jing Z, Ming C. Clinical outcomes of drug-eluting balloon for treatment of small coronary artery in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16(4):913 918. ( 10.1007/s11739-020-02530-w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang DP, Wang LF, Liu Y, et al. [Efficacy comparison of primary percutaneous coronary intervention by drug-coated balloon angioplasty or drug-eluting stenting in acute myocardial infarction patients with de novo coronary lesions]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2020;48(7):600 607. ( 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200327-00254) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hao X, Huang D, Wang Z, Zhang J, Liu H, Lu Y. Correction to: study on the safety and effectiveness of drug-coated balloons in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;16(1):247. ( 10.1186/s13019-021-01629-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ahmad WAW, Nuruddin AA, Abdul Kader MASK, et al. Treatment of coronary de novo lesions by a sirolimus- or paclitaxel-coated balloon. JACC Cardiovasc Intv. 2022;15(7):770 779. ( 10.1016/j.jcin.2022.01.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a