Abstract

A satellite RNA of 836 nucleotides [excluding the poly(A) tail] depends on the bamboo mosaic potexvirus (BaMV) for its replication and encapsidation. The BaMV satellite RNA (satBaMV) contains a single open reading frame encoding a 20-kDa nonstructural protein (P20). The P20 protein with eight histidine residues at the C terminus was overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Experiments of gel retardation, UV cross-linking, and Northwestern hybridization demonstrated that purified P20 was a nucleic-acid-binding protein. The binding of P20 to nucleic acids was strong and highly cooperative. P20 preferred binding to satBaMV- or BaMV-related sequences rather than to nonrelated sequences. By deletion analysis, the P20 binding sites were mainly located at the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of satBaMV RNA, and the RNA-protein interactions could compete with the poly(G) and, less efficiently, with the poly(U) homopolymers. The N-terminal arginine-rich motif of P20 was the RNA binding domain, as shown by in-frame deletion analysis. This is the first report that a plant virus satellite RNA-encoded nonstructural protein preferentially binds with nucleic acids.

RNA-binding proteins play key roles in the posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression in eukaryotic cells. In RNA viruses, RNA-binding proteins are essential for all of the viral life cycles, including replication, translation, movement, and encapsidation (3, 6, 8, 44). In plants, many RNA virus-encoded movement proteins (MPs) (4, 10, 11, 16, 29, 43, 48), capsid proteins (CPs) (1, 44, 45), and other functional proteins (12, 15, 18, 20, 25, 40, 41) are RNA-binding proteins. In other investigations, host proteins that regulate viral RNA translation bound to viral RNAs (3, 5, 14, 17, 51). In potato virus X, two host factors were identified to bind with essential nucleotides for viral replication (50).

Among satellites associated with viruses, the small and large forms of delta antigens encoded by hepatitis D virus (HDV) are the only satellite-encoded proteins that have been identified to bind with viral RNAs in vitro (30). These proteins profoundly affect HDV replication and packaging (8, 28). The RNA binding domain of delta antigens consists of two arginine-rich motifs (ARMs) (28), which are commonly found in viral, bacteriophage, and ribosomal proteins (6). In addition to delta antigens, the nonstructural proteins encoded by mRNA-type satellites of nepovirus are very basic; some of them also contain ARMs at the N termini (19). However, such RNA-binding activity has not yet been identified. The example analyzed in the present study was the nucleic-acid-binding properties of the bamboo mosaic virus (BaMV) satellite RNA (satBaMV)-encoded nonstructural protein.

The genomic organization of BaMV, like those of other potexviruses, contains a 6.4-kb single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome with five conserved open reading frames (ORFs) (31, 33, 53). The satBaMV, the only satellite RNA found in the potexvirus group, depends on BaMV for its replication and encapsidation, but it shares little sequence homology with BaMV except for the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) (34). The satBaMV contains 836 nucleotides [excluding the poly(A) tail] and encodes a 20-kDa nonstructural protein (P20) (34). In contrast to satellite-encoded proteins associated with nepoviruses, which are required for satellite RNA replication (21, 23, 39), P20 is not essential for satBaMV replication (35). However, all of the satBaMV variants we have sequenced contain the P20 ORF (38). P20 can be immunologically detected and located in plant cells coinfected with BaMV and satBaMV (36). Mutations within the P20 ORF delayed or impaired satBaMV systemic movement (9, 35), suggesting a significant role of P20 in the satBaMV life cycle. P20 shares 46% identity in amino acid sequences with the 17-kDa CP of a satellite virus associated with panicum mosaic sobemovirus (sPMV) (37). According to computer modeling, P20 also structurally resembles the 17-kDa CP which consists of eight-stranded β-sheets to form a “jelly roll” structure (2, 38). P20 is a relatively basic protein (pI, 10.26), and its N-terminal amino acid residues are rich in arginines, suggesting that P20 may be an RNA-binding protein.

In this study, we constructed a recombinant P20 with eight histidine residues (His-Tag) at the C terminus and expressed it in Escherichia coli. The recombinant P20 was a strong nucleic-acid-binding protein that preferred binding with RNA rather than DNA. Binding of P20 to nucleic acids was highly cooperative and preferential to satBaMV sequences. By deletion analysis, we concluded that the P20 binding sites were mainly located at the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of satBaMV RNA and that the N-terminal ARM was the RNA binding domain of P20. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a plant virus satellite RNA-encoded nonstructural protein binding with nucleic acids in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction and expression of recombinant or truncated P20 in E. coli.

The ORF of the P20 protein was amplified from a full-length cDNA clone of satBaMV, pBSF4 (35), by the Expand High-Fidelity PCR System (Boehringer Mannheim) that introduced restriction enzyme sites, C-terminal His-Tag codons, and a stop codon. The 5′ primer was BS-39 (5′-ACCAAGCATATGGTTCGGAGGAGA-3′; the NdeI site is underlined, and the coding region of P20 ORF is in boldface), and the 3′ primer was BS-40 (5′-GATATACTCGAGTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGACTGGTTGGTGCACGGTCAG-3′; the XhoI site is underlined; the sequence complementary to the stop codon is in boldface; the sequence complementary to the His-Tag codons and to the BSF4 nucleotides 689 to 708 is in italics) (34). PCR products were directly ligated into the pGEM-T Easy Vector System (Promega) to produce pGEM-T20. After the pGEM-T was completely digested with XhoI, the plasmid DNA was partially digested with NdeI due to an internal NdeI site in the ORF of P20. The XhoI- and NdeI-digested fragment of 582 bp containing the full-length coding sequences of P20 and the His-Tag was gel eluted by a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and then ligated into pET21b (Novagen) previously digested with the same restriction enzymes to produce the recombinant P20 expression vector pET-P20.

To construct an in-frame truncated mutant of P20 (P18), pET-P18 was generated by using the in-frame second AUG as the translational initiation codon. The procedures used were the same as for P20 except that the 5′ primer used in PCR was BS-44 (5′-GTCTCCCATATGACCGACATC-3′, where the NdeI site is underlined, and the second ATG and in-frame coding region of P20 are in boldface) (34). All constructions were confirmed by sequencing analysis.

Purification of recombinant P20 and P18.

The E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring pET-P20 or pET-P18 were grown in Luria-Bertani or 2× YT media (47) (pH 7.4) with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml at 37°C to mid-log phase. After 0.4 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction for 3 h at 28°C, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min (Hitachi RPR 10-2 rotor). The cell pellets were resuspended in buffer A (20 mM Tris, pH 7.9; 0.1 M NaCl; 5 mM imidazole) with complete proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Boehringer Mannheim) on ice. After the cells were broken by ultrasonic treatment (Sonicator Ultrasonic Processor XL; Misonix), inclusion bodies and cell debris were collected by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min (Hitachi R20A-2 rotor). The pellets were then resuspended in buffer B (buffer A with 8 M urea) on ice overnight. After centrifugation at 39,000 × g for 20 min, the soluble proteins were loaded onto a Ni2+ affinity column packed with His-Bind Resin (Novagen), and the His-Tag fusion proteins were purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the loading sample was passed through the resin and washed with buffer B followed by buffer B containing 35 mM imidazole, and then the His-Tag fusion proteins were eluted with buffer B containing 300 mM imidazole. Finally, the column was treated with buffer S (20 mM Tris, pH 7.9; 50 mM EDTA) to remove the charged Ni2+ ions and any residual proteins. After being concentrated by an Ultrafree Centrifugal Filter Device (Millipore), the purified P20 or P18 was renatured by dialysis at 4°C against CAPS [3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid] buffer (20 mM CAPS, pH 11.0; 0.1 M NaCl; 1 mM dithiothreitol; 10% glycerol) with increasingly lower concentrations of urea to gradually remove detergent. Samples from each purification step were subjected to analysis by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining (47). The concentrations of purified proteins were determined by the Bradford method (27).

Preparation of 32P-labeled nucleic acid probes.

The riboprobes used in this study were made by in vitro transcription of restriction enzyme-linearized plasmids with [α-32P]CTP (Amersham) in a nucleotide mixture with RNA polymerase (Promega), followed by purification with a Push Column Beta Shield Device and NucTrap Probe Purification Columns (Stratagene). The specific activities of riboprobes were quantified by a Liquid Scintillation Analyzer (Packard). The amounts of nucleic acids were determined by absorption (A260) with a U-2000 Spectrophotometer (Hitachi).

The full-length positive-sense BSF4 riboprobe was prepared by using XbaI-linearized pBSF4 followed by transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (35). The full-length negative-sense BSF4 riboprobe was obtained by SacII digestion and SP6 transcription of pGEM-BSF4, which contained the full-length cDNA of BSF4 RNA ligated into the pGEM-T Easy Vector. To make 5′-deleted BSF4 riboprobes, pBSF4 DNA was digested with different restriction enzymes, namely, EcoNI, SacI, AvaII, BstXI, or ApaI, and blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase (47). After digestion with XbaI and gel elution, the resulting DNA fragments were ligated into HindIII-digested, blunt-ended, and then XbaI-digested pGEM-4 vector (Promega) to generate plasmids pG-S2, pG-S3, pG-S4, pG-S6, and pG-S7 (see Fig. 7A), respectively. The 5′-deleted riboprobes of BSF4 were generated by XbaI linearization and T7 transcription of these plasmids. The G-S1 riboprobe, containing only the 5′ UTR of BSF4, was obtained by BstXI digestion and T7 transcription of pBSF4. The G-S5 riboprobe, containing the P20 coding region of BSF4, was generated by XhoI digestion and T7 transcription of pGEM-T20.

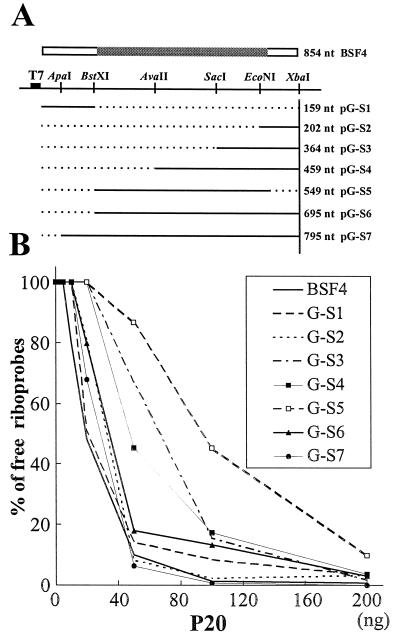

FIG. 7.

BSF4 satBaMV-derived mutants and their binding efficiencies with P20. (A) Schematic maps of satBaMV mutants. The dark, open, and shaded boxes represent the T7 promoter and the untranslated and P20 coding regions of BSF4 RNA, respectively. The restriction enzymes used in construction and the lengths of transcribed satBaMV mutants are indicated. The horizontal solid and dotted lines represent the transcribed and deleted portions of satBaMV mutants, respectively. (B) Gel retardation assays of the interactions of P20 with satBaMV mutants. The percentages of residual free riboprobes were determined as described in Fig. 3.

To make the 5′-end positive-sense riboprobe of BaMV, the first 841 nucleotides of BaMV-O were amplified from pBL (52) by PCR with 5′ primer B-17 (5′-TGCGGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGAAAACCACTCCAAACGAA-3′; the BamHI site is underlined, the T7 promoter is in italics, and the 5′-end sequence of BaMV is in boldface) and 3′ primer B-19 (5′-CTAGTCTAGAGCCTTCCACGCCGTATGAGT-3′; the XbaI site is underlined, the sequences complementary to the 822 to 841 nucleotides of BaMV are in boldface) (33). After being digested with BamHI and XbaI, the PCR products were ligated into pUC119 to generate pBa841. The BaMV 5′-end positive-sense riboprobe was obtained by XbaI digestion and T7 transcription of pBa841. The BaMV 3′ positive- and negative-sense riboprobes were made by BamHI digestion and T7 transcription or HindIII digestion and SP6 transcription of pBaHB (32), respectively, which contained 173 nucleotides covering the entire 3′ UTR of BaMV-O (33).

The sPMV positive- and negative-sense full-length riboprobes were derived from HindIII or EcoRI digestions and T7 or SP6 transcriptions of psPMV (a gift from K.-B. G. Scholthof, Department of Plant Pathology, Texas A & M University). The full-length positive-sense cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) satellite C (sat-C) riboprobe was derived from EcoRI digestion and T7 transcription of pCMV-SatC (24). The riboprobe derived from pET vector was obtained by using XhoI-digested pET21b vector and T7 transcription.

To make the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) probe, the full-length cDNA of BSF4 was amplified from pBSF4 (35) by PCR, purified with the Wizard PCR Preps DNA Purification System (Promega), and 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham) (47). After the dsDNA probe was boiled and quickly chilled, the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) probes were obtained.

Gel retardation analyses of the interactions between P20 and labeled nucleic acids.

The indicated amounts of purified P20 were incubated with 6 ng of 32P-labeled riboprobe and 2 U of RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega) in 15 μl of CAPS buffer for 30 min on ice. After incubation, samples were loaded onto a 1% agarose gel and electrophoresed with 0.5× Tris-boric acid-EDTA buffer at 4°C. After the gel was dried on 3MM Chr paper (Whatman), the mobility patterns of 32P-labeled nucleic acids were analyzed with a PhosphorImager with ImageQuant Version 3.3 (Molecular Dynamics).

For competition assays, the purified P20 was incubated with 0.5 μg of unlabeled competitor RNAs in CAPS buffer for 5 min on ice, and then 6 ng of 32P-labeled BSF4 positive-sense riboprobe was added for further incubation for 30 min. For the binding-strength assays, the indicated concentrations of NaCl were added to the incubation buffer. For the binding assays of DNA probes, a 20-ng amount of DNA probes was used instead.

UV cross-linking assays.

The purified 0.2 μg of P20 or P18 was incubated with 20 ng of BSF4 positive-sense riboprobes in a total volume of 10 μl of CAPS buffer on ice for 30 min. The reaction mixtures were then pipetted into a 96-well microtiter plate and irradiated on ice with 1.8 J of UV light by using a Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene). The mixtures were digested with 0.5 μg of RNase A (R-5500; Sigma) for 15 min at 37°C after 1 μl of 1 M Tris buffer (pH 6.8) was added to neutralize the buffer pH. Then, 10 μg of proteinase K was added for a further incubation of 15 min in some treatments. The cross-linked protein-RNA complexes were analyzed by SDS–15% PAGE and a PhorsphorImager.

Northwestern hybridization.

The total proteins extracted from E. coli expressing recombinant P20 or P18 were separated by SDS–12.5% PAGE and electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore) (47). The blot was washed by incubation with TEN50 buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA; 50 mM NaCl; 0.2% Nonidet P-40) for more than 24 h at 4°C and then hybridized with the binding buffer (TEN50 with 0.02% Ficoll 400, 0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 0.02% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 250 μg of yeast RNA per ml) containing riboprobes with a final concentration of 500,000 cpm/ml for 90 min at 40°C. After being washed with TEN50, TEN200 (TEN50 with 200 mM NaCl), and then TEN300 (TEN50 with 300 mM NaCl) for 10 min at 40°C, the membrane was dried on 3MM Chr paper and scanned by a PhosphorImager.

Oligopeptide.

The oligopeptide corresponding to the N-terminal 20-amino-acid residues of P20 (N20) was synthesized by using t-butyloxcarbonyl chemistry with an Applied Biosystems model 430A solid-phase peptide synthesizer. The amino acid sequence of N20 is MVRRRNRRQRSRVSQMTDIM (34).

RESULTS

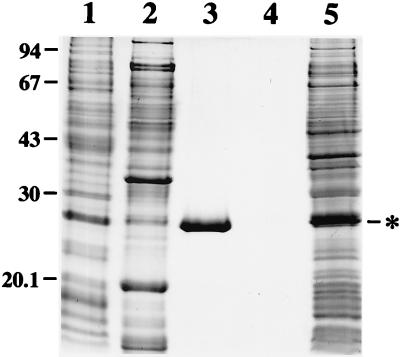

Construction, expression, and purification of recombinant P20.

To obtain a substantial amount of P20 for analyzing its biochemical properties, the cDNA of P20 ORF with 3′ His-Tag was inserted into a T7 expression vector, pET21b, to generate pET-P20. IPTG induction subsequently produced significant amounts of recombinant P20 in the form of dense, insoluble protein aggregates or inclusion bodies in E. coli (Fig. 1, lane 5). After sonication to break the cells, recombinant P20 was recovered from pellets containing inclusion bodies and cell debris by solubilization with 8 M urea in Tris buffer (pH 7.9); the solubilized mixture was then loaded onto an Ni2+ affinity column to purify the His-Tag fusion protein. Affinity chromatography was highly effective and, as shown in Fig. 1, resulted in recovery of P20 with >95% purity (lane 3). No other proteins were eluted from the column after EDTA treatment (lane 4). Due to the additional His-Tag and the high pI value, the recombinant P20 exhibited a mobility in SDS-PAGE of approximately 27 kDa (lane 3). The purified P20 was then dialyzed stepwise against Tris buffers with different pH values (pH 7.4 to 8.0) and different concentrations of NaCl (0.1 to 0.5 M) and with or without 0.1% Tween 20 or Nonidet P-40. However, purified P20 was precipitated when the urea concentration fell below 1 M. After being tested with different buffer systems with pH values of from 3 to 12, only the CAPS buffer (pH 11.0) could dissolve substantial amounts of precipitated P20 in the absence of urea. Thus, the purified P20 was renatured by stepwise dialysis against CAPS buffer with increasingly lower concentrations of urea. Finally, soluble recombinant P20 was obtained in CAPS buffer and remained soluble even after centrifugation at 150,000 × g for 30 min when the P20 concentration was not greater than 1.1 μg/μl.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of overexpressed and purified P20. Total proteins extracted from E. coli harboring the pET-P20 (lane 5) and the flow-through proteins (lane 1), the 35 mM imidazole washing-out proteins (lane 2), the 300 mM imidazole eluting recombinant P20 (lane 3), or the EDTA-eluting residual proteins (lane 4) from the Ni2+ affinity column were analyzed by SDS–15% PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. The positions of marker proteins (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. The asterisk shows the position of the recombinant P20.

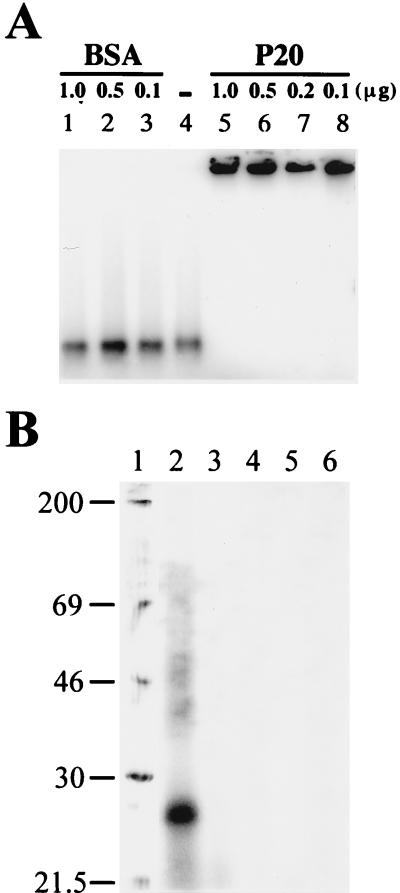

Binding of recombinant P20 to BSF4 positive-sense RNA.

The nucleic-acid-binding activities of the purified P20 were initially assayed by the ability of P20 to retard a radioactively labeled BSF4 positive-sense riboprobe on a native agarose gel. As shown in Fig. 2A, the BSF4 riboprobe incubated with the recombinant P20 was retained in the wells in 1% agarose gel after electrophoresis (lanes 5 to 8). The probe did not bind with BSA under the same conditions (lanes 1 to 3). To exclude the possibility of any unknown and impure proteins being bound to BSF4 RNA, a UV cross-linking experiment was performed. The incubation mixture of P20 and BSF4 riboprobe was treated with UV irradiation followed by RNase A digestion and SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 2B, a single radiolabeled protein of about 27 kDa was detected (lane 2). The mixture of P20 and BSF4 riboprobe without UV irradiation (lane 4) and the protein-RNA mixture treated with proteinase K (lane 3) did not show the reaction. We inferred from these results that the recombinant P20 was the only covalently cross-linked protein that bound to BSF4 RNA in vitro.

FIG. 2.

Gel retardation (A) and UV cross-linking (B) assays of the protein-RNA interactions. (A) The indicated amounts of BSA (lanes 1 to 3) and purified P20 (lanes 5 to 8) or of buffer only (lane 4) were incubated with 6 ng of 32P-labeled BSF4 riboprobe for 30 min in CAPS buffer on ice and then electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel. The gel was dried and analyzed by PhosphorImager scanning. (B) UV cross-linking assays of P20 and P18 to 32P-labeled BSF4 positive-sense riboprobe. P20 (lanes 2 to 4) or P18 (lanes 5 to 6) was incubated with BSF4 riboprobe. After UV irradiation (lanes 2, 3, and 5), the sample mixtures were treated with RNase A (lanes 2 to 6) and proteinase K (lane 3). The RNA cross-linked proteins were analyzed by SDS–15% PAGE and PhosphorImager scanning. Positions of Rainbow [14C]methylated protein molecular-mass markers (in kilodaltons) (Amersham) are indicated beside lane 1.

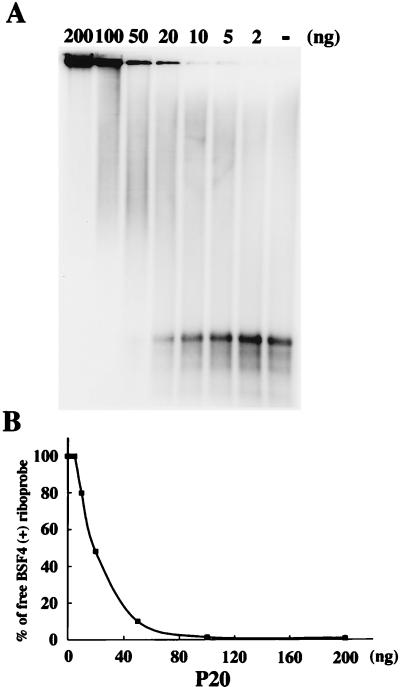

Highly cooperative binding of P20 to nucleic acids.

To identify the interactive relations between P20 and BSF4 RNA, serial amounts of P20 were used to examine its binding pattern. Figure 3A shows an “all or none” pattern in the binding of P20 to BSF4 RNA. No intermediate band representing a partially coated BSF4 riboprobe could be clearly identified between free and fully retarded riboprobes. This binding pattern demonstrated a highly cooperative mode of interaction between P20 and BSF4 RNA. As Figure 3B illustrates, the saturated binding of BSF4 RNA with increasing amounts of P20 was achieved at a protein/RNA weight ratio of about 25:1. The BSF4 positive-sense riboprobe was 854 nucleotides in length [including poly(A)17 and one extra non-satBaMV nucleotide], accounting for why the minimum size of recombinant P20 bound was an average of three nucleotides of BSF4 RNA per P20 monomer. These results resemble those observed with the P30 protein of tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), which had an average of four to five nucleotides for each P30 protein bound (9), and with the RecA protein of E. coli, which had binding-site size of three nucleotides (46).

FIG. 3.

Gel retardation assay (A) and the binding curve of P20-RNA interacting complexes (B). (A) The indicated amounts of purified P20 or buffer only (lane −) were mixed with 6 ng of 32P-labeled BSF4 riboprobe and then assayed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The percentages of residual free riboprobes were quantified with a PhosphorImager and the ImageQuant Version 3.3 program. The binding curve of RNA-P20 interactions is plotted in panel (B).

To examine the binding efficiencies of P20 to DNAs, BSF4 ds- and ssDNA probes were generated. P20 retarded BSF4 ds- and ssDNA probes in a highly cooperative mode, just as did ssRNA, and the binding efficiencies of P20 to ds- and ssDNAs were similar but only about one-sixth as efficient as ssRNA (data not shown).

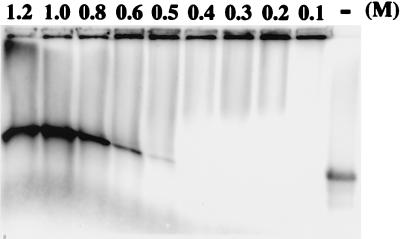

The binding strength of P20 to BSF4 riboprobe.

The strength of P20-BSF4 riboprobe interactions was measured by using increasing concentrations of NaCl in the reaction mixture. As shown in Fig. 4, the P20-RNA complexes started to separate at an NaCl concentration exceeding 0.5 M and became fully dissociated at salt concentrations above 0.8 M. This indicated a high binding strength of P20 to BSF4 RNA, although the assay was performed in a very basic incubation buffer.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the binding strength of P20-RNA complexes. Purified P20 (0.1 μg) was incubated with 6 ng of 32P-labeled BSF4 positive-sense riboprobe or with buffer only (lane −) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of NaCl. After incubation on ice for 30 min, the P20-RNA complexes were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and PhosphorImager scanning.

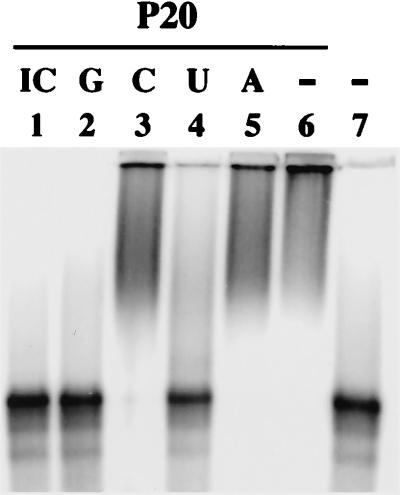

P20 preferentially binding with ssRNAs.

To determine whether P20 could bind specific RNAs, competition assays were performed. Different homopolymer RNAs were used to compete with P20 in binding to BSF4 riboprobe. The gel retardation pattern shown in Fig. 5 revealed that poly(I-C) dsRNA and poly(G) ssRNA were the most efficient competitors (lanes 1 and 2); poly(U) ssRNA was the next most efficient (lane 4), whereas poly(A) and poly(C) ssRNAs were ineffective (lanes 3 and 5). This observation indicated that P20 preferred binding to dsRNA and to G- or U-rich ssRNAs.

FIG. 5.

Competition assays of P20-RNA complexes with different homopolymer RNAs. Purified P20 (0.1 μg) was incubated with buffer only (lane 6) or with 0.5 μg of unlabeled poly(I-C) dsRNA (lane 1), poly(G) (lane 2), poly(C) (lane 3), poly(U) (lane 4), or poly(A) (lane 5) ssRNAs for 5 min on ice, respectively, followed by the addition of 6 ng of 32P-labeled BSF4 positive-sense riboprobe for further incubation for 30 min. The competition activities of homopolymer RNAs to P20-BSF4 RNA interactions were analyzed by gel retardation assay. Lane 7, BSF4 riboprobe only.

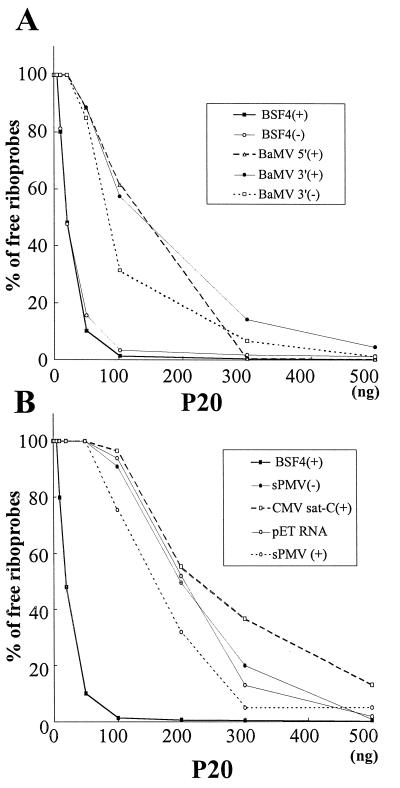

To further test the P20 binding specificity, two groups of single-stranded riboprobes were prepared. One was BaMV- or satBaMV-related RNAs, including BaMV 5′ positive-sense and 3′ positive- or negative-sense RNAs and BSF4 positive- or negative-sense RNAs. The other was BaMV- and satBaMV-nonrelated RNAs, including the sPMV positive- and negative-sense RNAs, positive-sense RNA of CMV sat-C, or pET21b vector directing RNA. As shown in Fig. 6A, P20 most efficiently retarded positive- and negative-sense BSF4 ssRNAs, followed by BaMV 3′ negative-sense RNA, and then BaMV 5′ and 3′ positive-sense RNAs. A sixfold amount of P20 was needed to retard 50% of BaMV 5′ and 3′ positive-sense RNAs compared to BSF4 RNA. However, an approximately 10-fold amount of P20 was required to obtain 50% retardation of nonrelated riboprobes (Fig. 6B). These results led us to conclude that the P20 preferred binding to positive- and negative-sense satBaMV RNAs rather than to BaMV-related RNAs and other nonrelated RNAs.

FIG. 6.

RNA binding activities of purified P20 with different single-stranded riboprobes. Gel retardation assays of the interactions of P20 with satBaMV- and BaMV-related riboprobes (A) or with satBaMV- and BaMV-nonrelated riboprobes (B). The percentages of residual free riboprobes were determined as described in Fig. 3.

P20 binding site(s) of satBaMV RNA.

To determine whether core binding sites exist in satBaMV RNA, serial 5′-end-deleted mutants of BSF4 RNA were generated (Fig. 7A). G-S7 had a 59 nucleotide deletion at the 5′ end of BSF4 and G-S6 lacked the 5′ UTR of 159 nucleotides. G-S4 and G-S3 had deletions from the 5′ end to the AvaII or SacI site of the P20 coding region, respectively. G-S2 retained only the 3′ 59 nucleotides of the P20 coding region and the entire 3′ UTR of BSF4 (Fig. 7A). The P20 retardation efficiencies of deleted mutants were plotted and shown in Fig. 7B. The mutants containing progressive deletions from the 5′ end of BSF4 RNA reduced the binding efficiencies to P20, with only one exception: G-S2 RNA. Although G-S2 RNA had the longest 5′ deletion, its binding efficiency with P20 was comparable to those of the two longest mutant RNAs, G-S7 and G-S6, implying that a core binding site might exist within G-S2 RNA. The binding site on the short G-S2 RNA may be more accessible for P20 than those on the other two longer RNAs, G-S3 and G-S4. This may account for the high binding efficiency of G-S2 to P20.

To determine whether any core binding sites other than G-S2 RNA might also exist in BSF4 RNA, G-S1 containing the 5′ UTR and G-S5 containing only the P20 coding region were generated (Fig. 7A). Notably, the retardation efficiency of P20 to the shortest mutant RNA, G-S1, was the highest, at a level comparable to that of full-length BSF4 RNA, whereas G-S5 RNA showed the weakest affinity for P20 among the examined satBaMV RNAs (Fig. 7B). Taken together, the P20 main binding sequence(s), if it(they) exist(s), must be located at the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of satBaMV RNA.

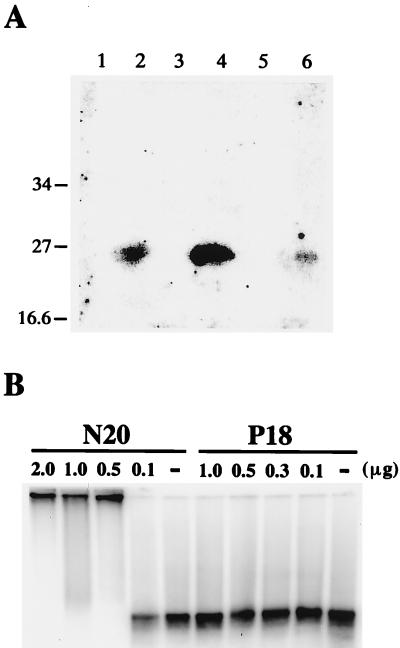

The nucleic acid binding domain of P20.

The N terminus of P20 is arginine-rich, with seven arginine residues in the first 12 amino acids (Table 1), a finding consistent with our prediction that the nucleic acid binding domain of P20 is located on this ARM. For confirmation, the ORF of an in-frame-deleted P20 mutant, P18, without the N-terminal 15 amino acids and the ARM, was overexpressed in E. coli. The RNA-binding abilities of recombinant P18 to riboprobes were examined by UV cross-linking experiments (Fig. 2B), Northwestern hybridization (Fig. 8A), and gel retardation assay (Fig. 8B), respectively. UV cross-linking results indicated that P18 failed to bind to the BSF4 riboprobe under the same conditions as P20 (Fig. 2B, lane 2 versus lane 5). Similar results were obtained from the Northwestern hybridization with the G-S1 riboprobe. As shown in Fig. 8A, strong signals at the positions of P20 were obtained from the total proteins of E. coli transformed with pBS17 (36), an expression vector with the full-length P20 ORF but without the His-Tag (lane 2) or pET-P20 (lane 4), or they were obtained from the purified recombinant P20 (lane 6). However, no specific signal was obtained from the total proteins of E. coli harboring pET-P18 (lane 3) or purified recombinant P18 (lane 5). These results indicated that P20, but not P18, could bind with satBaMV-specific riboprobe and that the N-terminal ARM of P20 was an essential RNA binding domain.

TABLE 1.

The amino acid sequences of N-terminal ARMs of satBaMV P20 and relevant proteins of other RNA viruses

| Proteinsa | ARMsb | References |

|---|---|---|

| BMV CP (9–21) | TRAQRRAAARRNR | 44, 49 |

| CMV CP (9–21) | SRTSRRRRPRRGS | 13, 44 |

| HIV-1 Rev (34–50) | TRQARRNRRRRWRERQR | 26 |

| HIV-1 Tat (47–58) | YGRKKRRQRRRP | 7 |

| HDAg M1 (97–107) | KERQDHRRRKA | 28, 30 |

| HDAg M2 (136–146) | EDEKRERRIAG | 28, 30 |

| satBaMV P20 (1–12) | MVRRRNRRQRSR | 34 |

| sPMV CP (1–12) | MAPKRSRRSNRR | 2, 42 |

Abbreviations of proteins used include brome mosaic virus (BMV), the Rev and Tat proteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), and the first (M1) and second (M2) ARMs of the delta antigen (HDAg) of hepatitis D virus. Numbers in parentheses refer to amino acid positions within the proteins.

The amino acid residues are represented in single-letter abbreviations. The amino acid residues of ARMs responsible for RNA binding or putative RNA binding are listed. The amino acid residues that are important for RNA binding in Rev and Tat proteins of HIV-1 (22) and HDAg (28) are underlined. The conserved basic amino acid residues with more than 60% similarity among these peptides are in boldface.

FIG. 8.

Analyses of the RNA binding activities of P20, P18, and N20. (A) Assays of RNA-protein interactions by Northwestern hybridization. The total proteins of E. coli transformed with pET21b vector only (lane 1), pBS17 (lane 2), pET-P18 (lane 3), or pET-P20 (lane 4), respectively, and the purified P18 (lane 5) or P20 (lane 6) were separated by SDS–12.5% PAGE. After transfer to a PVDF membrane, the blot was hybridized with 32P-labeled G-S1 riboprobe. The positions of prestained SDS-PAGE standards (in kilodaltons) (Bio-Rad) are indicated on the left. (B) Gel retardation assays of the binding activities of P18 protein or N20 oligopeptide to BSF4 positive-sense riboprobe. The indicated amounts of P18, N20, or buffer only (lane −) were incubated with 32P-labeled BSF4 positive-sense riboprobe and then analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and PhosphorImager scanning.

In addition, an oligopeptide N20 corresponding to the N-terminal 20 amino acids of P20 containing the ARM was chemically synthesized. Gel retardation assays revealed that N20, but not P18, was able to bind with the BSF4 riboprobe in a highly cooperative manner, as P20 did under the same conditions (Fig. 8B). In summary, the N-terminal ARM of P20 was the nucleic acid binding domain responsible for cooperative RNA binding.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that the purified recombinant P20 is a strong nucleic-acid-binding protein that binds to nucleic acids in a highly cooperative manner with sequence preference, as evidenced from gel retardation, UV cross-linking, and Northwestern hybridization. P20 prefers binding to RNA, particularly G- and U-rich ssRNA, rather than to DNA. The P20 binding sites are located primarily at the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of satBaMV RNA. The RNA binding domain appears to be the N-terminal ARM of P20.

The overexpressed P20 with His-Tag always formed inclusion bodies in E. coli. This occurred despite the fact that we grew the bacteria in a rich medium (YTGK medium; 16 g of yeast extract, 10 g of peptone, 10 ml of glycerol, 5 g of NaCl, and 0.75 g of KC1 per liter) at a relative high pH (pH 7.4) and induced P20 expression at a low temperature (28°C) or in the presence of rifampin (100 μg/ml). In addition, the use of 4 M urea was not sufficient to solubilize the pelleted recombinant P20, and a urea concentration of more than 7 M was needed. Therefore, the conventional means of solubilizing and purifying plant viral MPs did not work in this case (10). Interestingly, a CAPS buffer with a pH of 11.0 was the only buffer system we tested that could facilitate the renaturation of purified P20. Although the recombinant P20 theoretically has negative charges in CAPS buffer, the N20 containing the N-terminal ARM of P20 with a predicted pI value of 12.9 was positively charged. This finding may explain why the purified P20 in CAPS buffer retains strong RNA binding activity.

The data presented here excluded the possibility that the aggregates of P20 in the wells retarded nucleic acids because the BSF4 RNA-P20 interactions were competed by poly(I-C), poly(G), and poly(U) homopolymers but not by others (Fig. 5). The retardation efficiencies also varied with different RNAs (Fig. 6 and 7). In addition, we observed that only P20 was run into the agarose gel and shifted into the wells in the presence of BSF4 RNA by Western blotting (data not shown). The results of UV cross-linking and Northwestern hybridization further excluded the possibilities of nonspecific ionic interactions of P20 to nucleic acids or of contamination by other residual RNA-binding proteins (Fig. 2B and 8A). The additional His-Tag in the C terminus of P20 did not account for the nucleic acid binding activity because the recombinant P18 with the His-Tag lacked such activity (Fig. 2B and 8). On the other hand, the overexpressed P20 without the His-Tag in pBS17 transformed cells was shown to bind RNA (Fig. 8A).

The binding properties of P20 to nucleic acids resembled those of known plant viral MPs (10, 11, 16, 29, 43, 48) and CPs (1, 45) in many aspects. For instance, all plant viral MPs and CPs bound nucleic acids in a highly cooperative manner. The strength of P20-BSF4 RNA interactions in the present study was comparable to that of TMV and red clover necrotic mosaic virus MPs to ssRNAs (10, 43) and was stronger than those of cauliflower mosaic virus gene I product (11), the MPs of alfalfa mosaic virus (48) and CMV (29), and the CP of barley yellow mosaic virus (45) to ssRNAs. However, the P20-nucleic acid interactions also differed in some aspects. P20 preferred binding to RNA rather than DNA, whereas the well-characterized MPs bound ssRNA and ssDNA with similar affinities but with lower affinity to double-stranded nucleic acids (10, 43, 48). The efficient competing activity of poly(I-C) dsRNA with the P20-RNA interactions also indicates a different character for P20 (Fig. 5). Most of the MPs and CPs, except the AMV CP (1), bind nucleic acids in a highly cooperative manner without sequence specificity, but the binding cooperativity of AMV CP appeared to be lower than those of other MPs and CPs (1). In contrast, P20 bound RNAs with sequences that were preferable to satBaMV RNA (Fig. 5, 6 and 7).

The P20 core binding sites were primarily located at the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of satBaMV RNA (Fig. 7), particularly with G- and U-rich sequences (Fig. 5). Thus, the suggested P20 binding sequences in BSF4 RNA may be the 5′-terminal 72GCUGAGGGUGUGGCAGG88 and 108UGUGGUGUU116 sequences and the 3′-terminal 747GGUUUAGCCUGGUU760 and 799GUAGUGGUGGUCGU812 sequences (34). Since the binding efficiencies of P20 to positive- or negative-sense BSF4 riboprobes were similar (Fig. 6A), the possible P20 binding site with the G- and U-rich sequences may also be located in the 3′ end of negative-sense BSF4 RNA, which is complementary to nucleotides 2 to 51 of BSF4 (34). Although the 5′ UTR of BaMV contains 94 nucleotides (33) and shares 63% identity with the corresponding region of the satBaMV 5′ UTR (34), the BaMV 5′ positive-sense riboprobe had much less affinity for P20 than did positive-sense BSF4 and G-S1 riboprobes (Fig. 6A and 7B). The lack of G- and U-rich sequences in the BaMV 5′ UTR, which are otherwise found in the satBaMV 5′ UTR, may account for such a low binding efficiency. Likewise, the binding efficiencies of P20 to positive- and negative-sense sPMV RNAs were relatively low and close to those of the unrelated CMV sat-C and pET21b vector-directed sequences (Fig. 6B). Sequences highly rich in G and U were not found in the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of sPMV RNA (42). Although the satBaMV RNA shares high identity with sPMV in their coding regions (37), the G-S5 riboprobe containing only the P20 coding region of satBaMV showed the least P20 binding affinity among the examined satBaMV sequences (Fig. 7B).

The RNA binding domain of P20 was the N-terminal ARM. P18, without the ARM, did not have any RNA binding activities under the same conditions, whereas the chemically synthesized N20 containing the ARM did (Fig. 2B and 8). These results were further supported by the crystallography of the CP of sPMV in which its N-terminal ARM was predicted to be the viral RNA binding domain (2), although the RNA-protein interactions have not yet been identified. Among the available ARMs of RNA viral proteins, conserved basic amino acids, especially arginine, were noted, although the sources of these proteins are quite diverse (Table 1).

The biological function(s) of P20 still remains unclear, however, since P20 could only be detected in plant protoplasts coinfected with BaMV and satBaMV at the early stage of infection (36). Previous results also showed that P20 might play a facilitating role in satBaMV replication and systemic movement in infected plants (35). Results of this study demonstrate that the nucleic-acid-binding properties of P20 are unique in P20’s high cooperativity and sequence preference for satBaMV RNA. Whether P20 functions as a stabilizing factor for satBaMV RNA remains to be determined. Nevertheless, the satBaMV RNA-P20 interactions may facilitate the understanding of how P20 regulates satBaMV replication, how P20 assists satBaMV to move systematically, and how P20 regulates the interactions among BaMV, satBaMV, and host cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by National Science Council Project grants NSC-86-2311-B001-036-B11 and NSC-87-2311-B001-004-B11 and by Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baer M L, Houser F, Loesch-Fries L S, Gehrke L. Specific RNA binding by amino-terminal peptides of alfalfa mosaic virus coat protein. EMBO J. 1994;13:727–735. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ban N, McPherson A. The structure of satellite panicum mosaic virus at 1.9 Å resolution. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:882–890. doi: 10.1038/nsb1095-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belsham G J, Sonenberg N. RNA-protein interactions in regulation of picornavirus RNA translation. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:499–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.499-511.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleykasten C, Gilmer D, Guilley H, Richards K E, Jonard G. Beet necrotic yellow vein virus 42 kDa triple gene block protein binds nucleic acid in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:889–897. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-5-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blyn L B, Chen R, Semler B L, Ehrenfeld E. Host cell proteins binding to domain IV of the 5′ noncoding region of poliovirus RNA. J Virol. 1995;69:4381–4389. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4381-4389.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burd C G, Dreyfuss G. Conserved structures and diversity of functions of RNA-binding proteins. Science. 1994;265:615–621. doi: 10.1126/science.8036511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calnan B J, Biancalana S, Hudson D, Frankel A D. Analysis of arginine-rich peptides from the HIV Tat protein reveals unusual features of RNA-protein recognition. Genes Dev. 1991;5:201–210. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang M-F, Chen C-J, Chang S-C. Mutation analysis of delta antigen: effect on assembly and replication of hepatitis delta virus. J Virol. 1994;68:646–653. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.646-653.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, W., Lin, N.-S. and Y.-H. Hsu. Unpublished data.

- 10.Citovsky V, Knorr D, Schuster G, Zambryski P. The P30 movement protein of tobacco mosaic virus is a single-strand nucleic acid binding protein. Cell. 1990;60:637–647. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90667-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Citovsky V, Knorr D, Zambryski P. Gene I, a potential cell-to-cell movement locus of cauliflower mosaic virus, encodes an RNA-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2476–2480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daros J-A, Carrington J C. RNA binding activity of NIa proteinase of tobacco etch potyvirus. Virology. 1997;237:327–336. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies C, Symons R H. Further implications for the evolutionary relationships between tripartite plant viruses based on cucumber mosaic virus RNA 3. Virology. 1988;165:216–224. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90675-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dominguez D I, Hohn T, Schmidt-Puchta W. Cellular proteins bind to multiple sites of the leader region of cauliflower mosaic virus 35S RNA. Virology. 1996;226:374–383. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donald R G K, Jackson A O. RNA-binding activities of barley stripe mosaic virus γb fusion proteins. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:879–888. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-5-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donald R G K, Lawrence D M, Jackson A O. The barley stripe mosaic virus 58-kilodalton βb protein is a multifunctional RNA binding protein. J Virol. 1997;71:1538–1546. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1538-1546.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehrenfeld E, Gebhard J G. Interaction of cellular proteins with the poliovirus 5′ noncoding region. Arch Virol Suppl. 1994;9:269–277. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9326-6_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez A, Lain S, Garcia J A. RNA helicase activity of the plum pox potyvirus CI protein expressed in Escherichia coli. Mapping of an RNA binding domain. Nucleic Acid Res. 1995;23:1327–1332. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.8.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritsch C, Mayo M, Hemmer O. Properties of the satellite RNA of nepoviruses. Biochimie. 1993;75:561–567. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(93)90062-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gramstat A, Courtpozanis A, Rohde W. The 12 kDa protein of potato virus M displays properties of a nucleic acid-binding regulatory protein. FEBS Lett. 1990;276:34–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80500-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hans F, Pinck M, Pinck L. Location of the replication determinants of the satellite RNA associated with grapevine fanleaf nepovirus (strain F13) Biochimie. 1993;75:597–603. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(93)90066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harada K, Martin S S, Frankel A D. Selection of RNA-binding peptides in vivo. Nature. 1996;380:175–179. doi: 10.1038/380175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemmer O, Oncino C, Fritsch C. Efficient replication of the in vitro transcripts from cloned cDNA of tomato black ring virus satellite RNA requires the 48K satellite RNA-encoded protein. Virology. 1993;194:800–806. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu, Y.-H., C.-W. Wu, C.-W. Lee, C.-C. Hu, and F.-Z. Lin. Unpublished data.

- 25.Kadare G, David C, Haenni A-L. ATPase, GTPase, and RNA binding activities associated with the 206-kilodalton protein of turnip yellow mosaic virus. J Virol. 1996;70:8169–8174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8169-8174.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kjems J, Calnan B J, Frankel A D, Sharp P A. Specific binding of a basic peptide from HIV-1 Rev. EMBO J. 1992;11:1119–1129. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruger N J. The Bradford method for protein quantitation. Methods Mol Biol. 1994;32:9–15. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-268-X:9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee C-Z, Lin J-H, Chao M, McKnight K, Lai M M C. RNA-binding activity of hepatitis delta antigen involves two arginine-rich motifs and is required for hepatitis delta virus RNA replication. J Virol. 1993;67:2221–2227. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2221-2227.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Q, Palukaitis P. Comparison of the nucleic acid- and NTP-binding properties of the movement protein of cucumber mosaic cucumovirus and tobacco mosaic tobamovirus. Virology. 1996;216:71–79. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin J-H, Chang M-F, Baker S C, Govindarajan S, Lai M M C. Characterization of hepatitis delta antigen: specific binding to hepatitis delta virus RNA. J Virol. 1990;64:4051–4058. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4051-4058.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin N-S, Lin F-Z, Huang T-Y, Hsu Y-H. Genome properties of bamboo mosaic virus. Phytopathology. 1992;82:731–734. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin N-S, Chen C-C, Hsu Y-H. Post-embedding in situ hybridization for localization of viral nucleic acid in ultrathin sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:1513–1519. doi: 10.1177/41.10.8245409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin N-S, Lin B-Y, Lo N-W, Hu C-C, Chow T-Y, Hsu Y-H. Nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of bamboo mosaic potexvirus. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2513–2518. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin N-S, Hsu Y-H. A satellite RNA associated with bamboo mosaic potexvirus. Virology. 1994;202:707–714. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin N-S, Lee Y-S, Lin B-Y, Lee C-W, Hsu Y-H. The open reading frame of bamboo mosaic potexvirus satellite RNA is not essential for its replication and can be replaced with a bacterial gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3138–3142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin, N.-S., Y.-S. Lee, and Y.-H. Hsu. Unpublished data.

- 37.Liu J-S, Lin N-S. Satellite RNA associated with bamboo mosaic potexvirus shares similarity with satellites associated with sobemoviruses. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1511–1514. doi: 10.1007/BF01322678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J-S, Hsu Y-H, Huang T-Y, Lin N-S. Molecular evolution and phylogeny of satellite RNA associated with bamboo mosaic potexvirus. J Mol Evol. 1997;44:207–213. doi: 10.1007/pl00006137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y-Y, Cooper J I. The multiplication in plants of arabis mosaic virus satellite RNA requires the encoded protein. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1471–1474. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-7-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo Y, Shuman S. RNA binding properties of vaccinia virus capping enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21253–21262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maia I G, Bernardi F. Nucleic acid-binding properties of a bacterially expressed potato virus Y helper component-proteinase. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:869–877. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-5-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masuta C, Zuidema D, Hunter B G, Heaton L A, Sopher D S, Jackson A O. Analysis of the genome of satellite panicum mosaic virus. Virology. 1987;159:329–338. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osman T A M, Hayes R J, Buck K W. Cooperative binding of the red clover necrotic mosaic virus movement protein to single-stranded nucleic acids. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:223–227. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-2-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao A L N, Grantham G L. Molecular studies on bromovirus capsid protein. II. Functional analysis of the amino-terminal arginine-rich motif and its role in encapsidation, movement and pathology. Virology. 1996;226:294–305. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reichel C, Maas C, Schulze S, Schell J, Steinbiss H-H. Cooperative binding to nucleic acids by barley yellow mosaic bymovirus coat protein and characterization of a nucleic acid-binding domain. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:587–592. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-4-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roca I A, Cox M M. The RecA protein: structure and function. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;25:415–456. doi: 10.3109/10409239009090617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoumacher F, Erny C, Berna A, Godefroy-Colburn T, Stussi-Garaud C. Nucleic acid-binding properties of the alfalfa mosaic virus movement protein produced in yeast. Virology. 1992;188:896–899. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90549-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sgro J-Y, Jacrot B, Chroboczek J. Identification of regions of brome mosaic virus coat protein chemically cross-linked in situ to viral RNA. Eur J Biochem. 1986;154:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sriskanda V S, Pruss G, Ge X, Vance V B. An eight-nucleotide sequence in the potato virus X 3′ untranslated region is required for both host protein binding and viral multiplication. J Virol. 1996;70:5266–5271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5266-5271.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanguay R L, Gallie D R. Isolation and characterization of the 102-kilodalton RNA-binding protein that binds to the 5′ and 3′ translational enhancers of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14316–14322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsai C-H, Cheng C-P, Peng C-W, Lin B-Y, Lin N-S, Hsu Y-H. Sufficient length of a poly(A) tail for the formation of a potential pseudoknot is required for efficient replication of bamboo mosaic potexvirus RNA. J Virol. 1999;73:2703–2709. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2703-2709.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang C-C, Liu J-S, Lin C-P, Lin N-S. Nucleotide sequence and phylogenetic analysis of a bamboo mosaic potexvirus isolate from common bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris McClure) Bot Bull Acad Sin. 1997;38:77–84. [Google Scholar]