Abstract

VhChiP is a chitooligosaccharide-specific porin identified in the outer membrane of Vibrio campbellii type strain American Type Culture Collection BAA 1116. VhChiP contains three identical subunits, and in each subunit, the 19-amino acid N-terminal segment serves as a molecular plug (the “N-plug”) that controls the closed/open dynamics of the neighboring pores. In this study, the crystal structures of VhChiP lacking the N-plug were determined in the absence and presence of chitohexaose. Binding studies of sugar–ligand interactions by single-channel recordings and isothermal microcalorimetry experiments suggested that the deletion of the N-plug peptide significantly weakened the sugar-binding affinity due to the loss of hydrogen bonds around the central affinity sites. Steered molecular dynamic simulations revealed that the movement of the sugar chain along the sugar passage triggered the ejection of the N-plug, while the H-bonds transiently formed between the reducing end GlcNAc units of the sugar chain with the N-plug peptide may help to facilitate sugar translocation. The findings enable us to propose the structural displacement model, which enables us to understand the molecular basis of chitooligosaccharide uptake by marine Vibrio bacteria.

Keywords: chitin, chitoporin, sugar-specific channel, Vibrio spp

Vibrio campbellii (formerly known as Vibrio harveyi) is a noncholera, bioluminescent, virulent pathogen that causes a lethal disease, known as luminous Vibriosis, in both wild and cultured aquatic animals (1). V. campbellii is a fast-growing bacterium, which plays a significant role in the recycling of chitin and in this way, contributes to the carbon and nitrogen balance between the oceans and the earth. Like other marine Vibrio spp. (2, 3, 4), V. campbellii possesses an active chitin catabolic pathway, which allows the bacterium to utilize chitin as its sole carbon source. The chitin catabolic cascade of V. campbellii contains highly effective chitin-degrading enzymes (5, 6), and the degradation products are subsequently internalized by the cells. Chitin is first degraded to chitooligosaccharides ((GlcNAc)n, with n ≥2) and GlcNAc by chitinases (7, 8). Small sugar molecules, such as D-GlcNAc and (GlcNAc)2, are thought to pass through the outer membrane (OM) of the bacterial cells through protein channels that serve as general diffusion porins (9), while larger chitooligosaccharides ((GlcNAc)3,4,5,6) are taken up through a chitooligosaccharide-specific channel, known as chitoporin or ChiP (10, 11). The transported chitooligosaccharides are further degraded by chitin dextrinase (12) or exo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidases (6, 13), generating the final hydrolytic products D-GlcNAc and (GlcNAc)2, which are further translocated by a (GlcNAc)-specific phosphotransferase system transporter and a (GlcNAc)2 ABC transporter (14, 15, 16), respectively. The chitin catabolic cascade of marine Vibrio sp. is known to be operated by (GlcNAc)2-inducible genes that are tightly controlled by a two-component membrane-bound histidine kinase, identified as the chitin sensor (9). We previously identified and functionally characterized the first OM ChiP (VhChiP) from V. campbellii type strain American Type Culture Collection BAA-1116 (11). VhChiP is a sugar-specific OM porin with the ability to selectively transport a range of chitooligosaccharides, chitohexaose being the most preferred (11, 17). The average single-channel conductance of VhChiP was 1.8 ± 0.3 nS in 1 M KCl electrolyte, and each channel contains multiple GlcNAc-binding sites within the pore (18, 19). We previously determined the X-ray crystal structures of the OM-expressed and in vitro–refolded VhChiP in the absence and presence of chitotetraose and chitohexaose (PDB IDs: 5MDO, 5MDP, 5MDQ, 5MDR, 5MDS) (20). VhChiP consists of three identical β-barrels, each containing 16 β-strands connected on the extracellular side by eight hydrophilic loops and on the periplasmic side by eight short hydrophobic turns. In the structure of VhChiP complexed with chitohexaose, the sugar chain was found to extend throughout the extracellular side toward the periplasmic side and to interact exclusively with the multiple affinity sites. The most striking observation from our previous crystallographic data was that the N termini of the trimeric channel contained short helices of nine amino acids (Asp1–Lys9) that served as molecular plugs (the so-called “N-plugs”). In the OM-expressed channel (PDB ID: 5MDQ), all three subunits were plugged in such a manner that the N-plug of one subunit occluded the periplasmic half of the neighboring pore. However, in the open (in vitro–folded) channel (PDB ID: 5MDO), all three N-plugs were ejected from the trimeric pores.

The observation of the N-plug inside the OM-expressed VhChiP channel, but outside the sugar-bound channel, led us to hypothesize that entry of the sugar molecule into the protein pore may trigger the ejection of the N-plug. In this study, we performed structural determinations of the N terminally truncated VhChiP in the absence and presence of the preferred substrate (chitohexasose) and analyzed the protein–ligand interactions. We further employed time-resolved single-channel electrophysiology and isothermal microcalorimetry (ITC) to investigate sugar–channel interactions in the truncated channel and the Asp1 mutant and related the binding affinity to the structural data. In the last part of our study, we employed steered molecular dynamic (SMD) simulations to follow the movement of the sugar and its interactions with the N-plug inside the protein pore. Combining the data from protein crystallography, single-channel electrophysiology, and SMD simulations, we constructed a structural model for sugar translocation through the OM of marine Vibrio bacteria.

Results

The crystal structure of the N-terminal truncated VhChiP shows that chitohexaose is fully extended inside the channel lumen

The truncated VhChiP channel, lacking nine N-terminal amino acid residues, was successfully expressed in the OM of the omp-deficient Escherichia coli BL21 (Omp8) Rosetta host. The OM-expressed VhChiP was extracted with 2% (w/v) SDS, followed by 3% (v/v) poly(ethylene glycol) octyl ether (octyl POE), then further purified to homogeneity by gel filtration. Figure 1A shows a representative SDS-PAGE gel, with a single Coomassie-stained band of WT VhChiP that migrated to below 42 kDa (Fig. 1A, track 1), corresponding to the molecular weight of the protein, determined previously to be 39 kDa (11). The truncated VhChiP channel migrated faster in the gel (Fig. 1A, track 2), consistent with its predicted molecular weight of 36.4 kDa.

Figure 1.

Purification and structural determination of truncated VhChiP without and with sugar ligand.A, migration of the purified WT (track 1) and truncated VhChiP (track 2) relative to molecular weight standard proteins (track Std). B–D, X-ray crystal structures of the truncated VhChiPs. The upper figures are top views and lower figures are side views of the structures. B, cartoon representation of the ligand-free truncated VhChiP (PDB: 7EQM), showing the locations of three prominent loops: red for L8, blue for L2, and green for L3. C, surface representation of the ligand-free truncated structure (PDB: 7EQM. D, surface representation of the truncated structure in complex with chitohexaose (PDB: 7EQR). Chitohexaose is shown in a space-filling model, with atoms C represented in black, O in red, and N in blue. Each subunit is shown in a different color.

X-ray diffraction data of ligand-free truncated VhChiP were indexed, integrated, and scaled at a resolution of 2.40 Å in monoclinic space group C121, with a single trimer per asymmetric unit. The structure of the ligand-free truncated VhChiP was determined by molecular replacement (MR), using the refolded VhChiP (PDB ID: 5MDO) as a structural template. The final model of the ligand-free truncated VhChiP was refined to Rwork and Rfree values of 18.0% and 22.6%, respectively. X-ray diffraction data from truncated VhChiP cocrystallized with chitohexaose were obtained to a resolution of 2.75 Å. The data were processed in the triclinic P1 space group with two trimers per asymmetric unit. The structure of the ligand-bound truncated VhChiP was solved by MR, using the ligand-free truncated VhChiP structure as the template. The structure of chitohexaose was retrieved from the structure of VhChiP in complex with chitohexaose (PDB ID: 5MDR) and placed in the electron density map. The refined model for the chitohexaose-truncated VhChiP complex had refinement statistics Rwork and Rfree of 18.1% and 22.3%, respectively. The crystal structures of the ligand-free truncated VhChiP and the chitohexaose-bound truncated VhChiP were deposited under the PDB IDs of 7EQM and 7EQR, respectively. The details of crystallographic statistics of both structures are presented in Table 1. Inspection of the structures revealed that both truncated structures existed as intact trimers (Fig. 1B), indicating that the N-plug truncation did not affect the assembly of the protein. The trimeric subunits were held together by loops L2 (blue), while the longest loop L3 (green) protruded into the channel lumen, and loop L8 (red) covered the entrance of the protein pore on the extracellular side. The ligand-free truncated channel was open (Fig. 1C, top view and side view), as in the structure of the in vitro–refolded VhChiP (PDB ID: 5MDO, ref. (20)). We observed electron density for the sugar ligand in all six protein chains (two trimeric molecules). However, the complete electron density map of six GlcNAc rings of chitohexaose was observed only in chains B and F, while the electron densities of the sugar molecules in chains A, C, D, and E were partial, missing mainly the areas assigned to GlcNAc-1 (nonreducing end) and GlcNAc-6 (reducing end) of the sugar chain. For the structures of chains B and F, (Fig. 1D, upper panel), the sugar chain was fully extended inside the pore, in a similar manner to chitohexaose found in the native structure. The six GlcNAc rings of the sugar chain extended throughout the affinity sites 1-6 from the periplasmic side toward the extracellular side (Fig. 1C, lower panel).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics of the truncated VhChiP channels in the absence and presence of chitohexaose

| PDB ID | Apo truncated VhChiP 7EQM |

Truncated VhChiP+chitohexaose |

|---|---|---|

| 7EQR | ||

| Wavelength | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Resolution range | 19.91–2.50 (2.59–2.50) | 19.82–2.75 (2.85–2.75) |

| Space group | C 1 2 1 | P 1 |

| Unit cell | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 105.2, 151.4, 95.8 | 58.0, 131.2, 136.6 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 111.1, 90 | 65.8, 87.8, 86.9 |

| No. of asymmetric unit | 1 trimer | 2 trimers |

| Total reflections | 200,430 | 500,859 |

| Unique reflectionsa | 43,100 (3248) | 85,921 (6047) |

| Completeness (%) | 89.2 (67.7) | 90.1 (63.9) |

| Mean I/sigma(I) | 12.2 (2.9) | 9.9 (1.8) |

| Multiplicity | 3.6 (3.1) | 5.1 (3.4) |

| Wilson B-factor | 31.8 | 42.5 |

| Rmeas | 0.119 (0.397) | 0.188 (0.730) |

| Rpim | 0.061 (0.213) | 0.081 (0.345) |

| CC1/2 | (0.864) | (0.776) |

| Reflections used in refinement | 43,094 (3248) | 85,896 (6047) |

| Reflections used for Rfree | 2137 (166) | 4784 (294) |

| Rwork | 0.180 (0.197) | 0.181 (0.211) |

| Rfree | 0.226 (0.292) | 0.223 (0.275) |

| Number of nonhydrogen atoms | 8149 | 16,450 |

| Macromolecules | 7731 | 15,462 |

| Ligands | 63 | 718 |

| Solvent | 355 | 304 |

| Protein residues | 993 | 1986 |

| RMS (bonds) (Å) | 0.007 | 0.009 |

| RMS (angles) (˚) | 0.87 | 1.03 |

| Ramachandran plots | ||

| Favored (%) | 97.16 | 95.95 |

| Allowed (%) | 2.63 | 3.95 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0.13 | 5.82 |

| Clash score | 3.56 | 12.36 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 33.0 | 43.2 |

| Macromolecules | 32.9 | 42.6 |

| Ligands | 38.5 | 57.6 |

| Solvent | 34.2 | 41.0 |

Values in parentheses are for the outer resolution shell.

The structures of closed and open sugar-bound states of VhChiP differ only in the position of the side chain of Tyr349

Superimposition of the Cα backbone of ligand-free truncated VhChiP (PDB ID: 7EQM) and chitohexaose-bound truncated VhChiP (PDB ID: 7EQR) with the unplugged refolded VhChiP (PDB ID: 5MDO) and sugar-bound VhChiP (PDB ID: 5MDR) yielded RMSD values for 340 Cα atoms of 0.22 and 0.28 Å (Fig. 2A), respectively, suggesting considerable similarity in their rigid backbones. Nevertheless, a significant movement of the side chain of Tyr349 on the internal surface of the β-barrels was apparent between the closed and open channels (Fig. 2A). In the plugged WT channel (PDB ID: 5MDQ), the side chain of Tyr349 was adjacent to the channel wall (red stick), while this residue pointed toward the middle of the pore in the open truncated channel (PDB ID: 7EQM, navy stick) and in both WT and truncated channels occupied by chitohexaose (PDB IDs: 5MDR, orange stick and 7EQR, pale green stick) (Fig. 2A). The angular shift from the Tyr349 side chain position in 5MDQ was 94.7° (7EQM), 85.1° (5MDR), and 81.7° (7EQR), respectively (Fig. 2B). The Tyr349 side chain in the plugged structure (Fig. 2C) was located close to the channel wall and formed a hydrogen bond with the side chain of the nearby (2.9 Å) residue Arg59 on strand B2. In contrast, the side chain of Tyr349 in the open and sugar-bound structures (Fig. 2C, 7EQM, 7EQR, and 5MDR) rotated away from Arg59 in the opposite direction and formed an H-bond with the side chain of Glu347 instead (approx. 2.7 Å).

Figure 2.

Structural comparison of truncated VhChiP with the native VhChiP structures.A, superimposition of Cα backbone of VhChiPs: 7EQM (ligand-free truncated, open channel) and 7QER (sugar-bound truncated) from this study, and 5MDQ (ligand-free WT, plugged channel) and 5MDR (sugar-bound WT) from the previous study, (20). Green represents the N-plug of 5MDQ. Chitohexaose is shown as sphere. B, the deviation of angle in Tyr349 in the open channel or in the sugar-bound channels when compared with the plugged channel (5MDR). C, distance and interactions of the side chain of Tyr349 in each VhChiP variant with its neighboring side chains. Hydrogen bonds are typically ≤ 3.5 Å.

N-terminal truncation caused the substantial loss of H-bonds around the central affinity sites

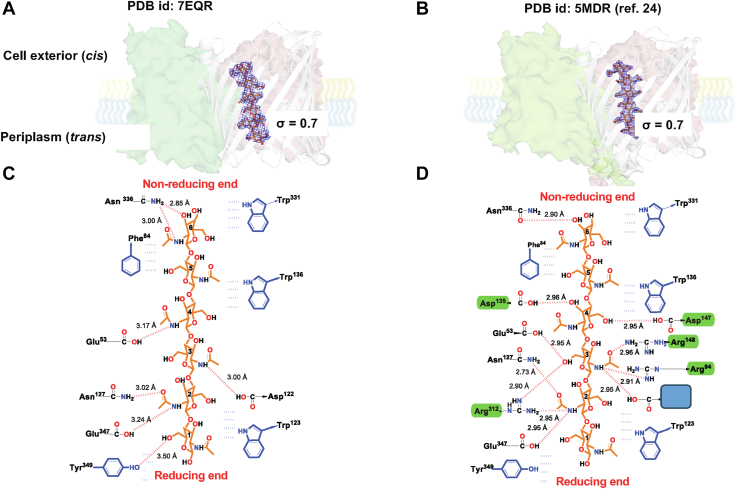

The crystal structure of the truncated VhChiP in complex with chitohexaose (PDB ID: 7EQR) contained two trimers per asymmetric unit, and two chains had sufficient electron density to fit chitohexaose inside the channel. The electron density of four GlcNAc rings was strong at the affinity sites 2 to 5 but weak at affinity sites 1 and 6 (Fig. 3A). As a result of weak interactions, the quality of the electron density of chitohexaose in the truncated channel was poorer than that of chitohexaose in the WT channel (PDB ID: 5MDR) (Fig. 3B). We observed that each of the trimeric β-barrels contained one molecule of chitohexaose inside the channel lumen (Fig. 3C) in which the reducing end sugar (GlcNAc-1) made π–π interactions with the plane of the aromatic side chains of Trp123 and Tyr349. One weak hydrogen bond was observed between the side chain of Tyr349 and the N-acetamido group of GlcNAc-1 (3.5 Å).

Figure 3.

LIGPLOT analysis of VhChiP binding to chitohexaose. The affinity sites are designated with numbers 1 to 6. A and B show the electron density map of chitohexaose in one of the monomers of the truncated channel (PDB ID: 7EQR) and WT channel (PDB ID: 5MDR; ref. (20)), respectively, with the OMIT maps of chitohexaose contoured at sigma = 0.7. C and D show the detailed interactions of chitohexaose with the pore-lining residues. Sugar backbones are shown as 2D with atoms colored orange for C, red for O, black for H, and blue for N. Hydrogen bonds (green) between the residues and the GlcNAc rings at the affinity sites 2 to 4 are missing in the truncated channel. Red broken lines represent hydrogen bonds. Blue residues form hydrophobic interactions. Residues that are involved in an extra H-bond in (D) relative to (C) are labeled with a green background.

At affinity site 2, two weak hydrogen bonds were observed, one between the carboxylate side chains of Asp127 and the O-acetamido group of GlcNAc-2 (3.02 Å) and another between the side chain of Glu347 and the N-acetamido group of GlcNAc-2 (3.24 Å). The plane of GlcNAc-2 also stacked against the plane of Trp123. For affinity sites 3 and 4, only one hydrogen bond was seen at each site, in which the carboxyl side chain of Asp122 bonded with the N-acetamido group of GlcNAc-3 (3.00 Å) and of Glu53 with the N-acetamido group of GlcNAc-4 (3.17 Å). GlcNAc-4 also made hydrophobic interactions with Trp136, while GlcNAc-5 made hydrophobic interactions with the side chains of Phe84 and Trp136 and GlcNAc-6 with Phe84 and Trp331, respectively. GlcNAc-6 also formed two hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Asn336. The crystal structure of the WT VhChiP showed clear electron density for chitohexaose with high-resolution diffraction data (1.90 Å), as well as high-binding affinity (20). Although the hydrophobic interactions at affinity site 1 (GlcNAc-1/Trp123/Tyr349) and affinity site 5 (GlcNAc-5/Phe84/Trp136) and site 6 (GlcNAc-6/Phe84/Trp331) were similar, more hydrogen bonds were observed in the WT channel (Fig. 3D) than in the truncated channel (Fig. 3C). Five hydrogen bonds were missing in the truncated structure (Fig. 3D, residues highlighted in green), including the N-acetamido group of GlcNAc-2/Arg312 (2.95 Å) and GlcNAc-3/Arg94 (2.91 Å), the O-acetamido groups of GlcNAc-3/Arg148 (2.96 Å) and Glu53/O-acetamido of GlcNAc-3 (2.95 Å), the O-acetamido of GlcNAc-3 Arg312/O- (2.90 Å) and the O-acetamido of GlcNAc-4/Asp135 (2.96 Å)/Asp145 (2.95 Å). A summary of interactions at each affinity site of both channels with chitohexaose is given in Table S1.

Single-channel electrophysiology reveals the N-terminal truncation caused the substantial loss in the binding affinity

Single-channel analysis using the black lipid membrane (BLM) reconstitution technique was employed to examine the effects of the Δ1-9 truncation on pore conductance of VhChiP (Fig. S1). The WT VhChiP could insert into artificial lipid membranes and remained fully open with occasional gating during a 2-min recording time under the given conditions (1 M KCl in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) (Fig. S1A). Histogram analysis of a total of 57 stepwise multiple insertions suggested an average single-channel conductance of 2.05 ± 0.2 nS (Fig. S1B), a value comparable to that of the OM-expressed VhChiP (1.8 ± 0.3 nS) reported previously (11). The truncated channel inserted relatively quickly into the membrane and remained more stably open, with no gating (Fig. S1C). The average channel conductance of truncated VhChiP was 2.0 ± 0.4 nS, estimated from histogram analysis of 60 insertions (Fig. S1D), similar to that of WT VhChiP.

The effect of the N-plug truncation on the binding affinity was investigated by single-channel analysis. Figure 4, A and B show ion traces from WT and truncated VhChiP, respectively, observed with an applied potential of +100 mV in 1 M KCl electrolyte and with different concentrations of chitohexaose (Fig. 4) added to the cis side of the chamber. It was clear that the sugar interacted strongly with the WT channel, causing temporary occlusion of ion flow in a concentration-dependent manner. In Figure 4A, we observed transient falls in the ionic current, mainly from the fully open (state O3) to one monomeric closure (state O2) as the sugar concentration was increased from 0 to 0.5 μM, and only occasionally did the ionic current fall further, with dimeric closure (state O1) when the concentration of chitohexaose was increased to 1.0 μM. The average residence time (τc) for the sugar molecule inside the channel was 3.7 ± 0.3 ms, and the estimated on-rate (kon) is 56 ± 10 × 106 M-1s-1. In contrast, rare and fast-blocking events were observed for the truncated channel at the same concentration range of the sugar and falls in current were only less frequently observed. The average residence time estimated for the sugar inside the truncated channel is about 2.4 ms and the on-rate is 12 × 106 M−1s−1. The binding constant (K) estimated for the WT is 250,000 ± 50,000 M−1, which is 8.3-fold greater than that for the truncated channel (30,000 ± 9000 M−1) (Table 2). Similar results were observed with sugar addition on trans side (Fig. 4, C for WT and D for truncated), the kinetic values being slightly different.

Figure 4.

Sugar-channel interaction studies by black lipid membrane (BLM) technique. The BLM experiments were carried out by adding chitohexaose on the cis side to (A) WT VhChiP, (B) truncated VhChiPs or trans side of (C) WT VhChiP and (D) truncated VhChiP reconstituted in lipid membranes. Both sides of the chamber were bathed with 1 M KCl in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4. The purified VhChiP (20 μg mL−1, 1 μl) was always added on the cis side. Both channels were exposed to different concentrations of chitohexaose (0–1 μM, but only traces at 0, 0.5, and 1.0 μM are shown). States of the channel in lipid membrane: O3, trimeric opening; O2, monomeric closure; O1, dimeric closure; and C: trimeric closure. Current traces were recorded continuously at 25 ± 1 °C at two potentials, ±100 mV (here only +100 mV is shown) for 2 min.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of the truncated VhChiP titrated with the synthesized N-plug peptide

| VhChiP | Sugar | N-plug | kon × 106 (M−1s−1) | τc (ms) | koff × 103 (s−1) | K (M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | cis | - | 68 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 0.27 ± 0.4 | 250,000 ± 50,000 |

| trans | - | 50 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 0.21 ± 0.5 | 240,000 ± 70,000 | |

| Truncated | cis | - | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 0.50 ± 0.1 | 11,000 ± 3000 |

| trans | - | 6.8 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 0.30 ± 0.1 | 23,000 ± 5000 | |

| Truncated | cis | trans | 56 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 255,000 ± 10,000 |

| cis | cis | - | - | - | n.d. |

The equilibrium binding constant (K, M−1) is estimated from Equation 1, which is derived from the relative reduction of the average single channel conductance when the channel was titrated with different concentrations of chitohexaose. The on-rate (kon, M−1 s−1) is given by kon = K · koff and the off-rate (koff, s−1) for the single trimeric molecule of VhChiP channel and its mutant by titration with chitohexaose from the relationship koff = 1/τc.

n.d., nondetectable blocking events.

The N-plug peptide corresponding to the first nine residues (DGANSDAAK) inside the protein pore was synthesized and added on either cis or trans side of the sample cell partitioned by the lipid bilayer, and its effects on the binding kinetics of sugar–channel interactions were investigated. Figure 5 shows the control traces without sugar addition on either side but with N-plug peptide added on the trans side at various concentrations. Under the applied potential of +100 mV in 1 M KCl, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, rare and short-lived blocking events were observed when the truncated channel was exposed to the N-plug peptide at 10 and 40 μM (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained when the N-plug peptide was added on the cis side without sugar (data not shown) and with both chitohexaose (1 μM) and the N-plug peptide (10 and 40 M) on cis side (Fig. 5B). The results were markedly different with the addition of chitohexaose on the cis side and the N-plug peptide on the trans side. Strong blocking events at a monomeric level from state O3 (fully open) to O2 (one monomer closure) were observed with 10 μM N-plug peptide added. When the concentration of the peptide was increased to 40 μM, blocking events in the monomeric closure (state O2) were much more frequent, along with sporadic blocking in the dimeric closure (state O1) (Fig. 5C). With the addition of 40 μM N-plug peptide, overlapping blocking events of states O2 and O1 were observed, allowing more than one sugar molecule to remain, at the same time, inside the protein channel (Fig. 5C, bottom trace).

Figure 5.

The effects of N-plug peptide binding on sugar–channel interactions. Single-channel experiments were carried out with the truncated channel as follows; (A) no sugar addition, varied concentrations of the N-plug peptide added on the trans side, (B) fixed concentration of chitohexaose (1 μM) on the cis side, varied concentrations of the N-plug peptide added on the cis side (10 and 40 μM); (C) fixed concentration of chitohexaose (1 μM) on the cis side, varied concentrations of the N-plug peptide added to the trans side. Current traces were recorded continuously at 25 ± 1 °C at ±100 mV (here only +100 mV are shown) for 2 min for each dataset.

Table 2 shows the kinetic values for chitohexaose interactions with VhChiP variants that were obtained from noise analysis of single-channel measurements. The equilibrium binding constant (K, M−1) estimated for chitohexaose additions on the cis and trans side of lipid bilayer reconstituted with the WT channel were similar (250,000 and 240,000 M−1, respectively). For the truncated channel, the K values for chitohexaose additions on the cis and trans sides were 11,000 M−1 and 23,000 M−1, respectively. When chitohexaose was added on the cis and N-plug on the trans side, the K value returned to 255,000 M−1, the value for chitohexaose–WT channel interactions. In contrast, the K value for the addition of both sugar and the N-plug peptide on the cis side was incalculable, as there were insufficient blocking events.

The decrease in binding affinity of the truncated channel was confirmed by ITC

The effects of N-plug truncation on the binding affinity of VhChiP were investigated using ITC. The ITC measurements yielded negative thermograms, indicating that all binding events occurred exothermically. Figure 6, top panels show ITC thermograms, and the bottom panels show the corresponding heat integration plotted against the molar ratio, with curve fitting using a one-site binding function. Chitohexaose titration into WT VhChiP (Fig. 6A) yielded an equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of 0.3 ± 0.1 μM and a stoichiometry of 3.2 ± 0.1. Titration of chitohexaose into the truncated channel yielded a Kd of 10 ± 0.3 μM and a stoichiometry of 2.8 ± 0.1 (Fig. 6B), while titration of chitohexaose with the truncated VhChiP mixed with the N-plug peptide (Fig. 6C) yielded a Kd of 2.9 ± 0.07 μM and a stoichiometry of 2.3 ± 0.2. Chitohexaose was shown to interact with the N-plug peptide with a Kd of 2.6 ± 0.12 mM and a stoichiometry of 1.0 ± 0.02. A summary of the ITC experiments and data appears in Table 3.

Figure 6.

Binding study by isothermal titration microcalorimetry. Titration of chitohexaose into (A) WT VhChiP, (B) truncated VhChiP, (C) truncated VhChiP mixed with the N-plug peptide, and (D) the synthesized N-plug peptide. Top panels are thermograms and bottom panels are the corresponding heat integrations with theoretical fits using a nonlinear one-site binding function, available in MicroCal PEAQ-ITC analysis software. ITC experiments were performed at 25 °C. The data were corrected for heats of dilution obtained by titration of chitohexaose into buffer (control data offset by +10 μcal.sec−1, top traces). Data presented are mean ± SD from the same set of experiments, which were carried out in triplicate. ITC, isothermal titration microcalorimetry.

Table 3.

Binding parameters for sugar–VhChiP interactions by isothermal titration calorimetry

| Chitohexaose titration |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Truncated VhChiP | Truncated VhChiP + N-plug peptide |

N-plug peptide | D1A mutant | |

| Substrate (mM) | 0.6 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 30 | 0.8 |

| Protein (μM) | 20 | 20 | 20 | - | 20 |

| N-plug (μM) | - | - | 5 | 500 | - |

| n (site) | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.02 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| Kd (μM) | 0.3 ± 0.06 | 10.0 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.07 | 2600 ± 120 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

SMD simulations confirmed that the sugar molecule induced the N-plug ejection

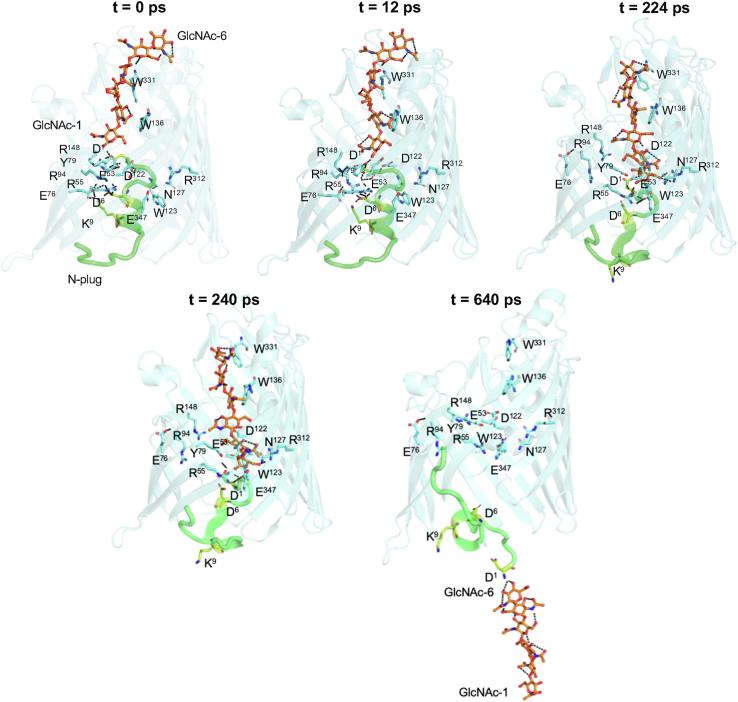

To address the molecular mechanism of translocation, SMD simulations were used to observe sugar movement through the pore. The plugged form of the OM-expressed VhChiP (PDB ID: 5MDQ) was chosen as the starting point for molecular docking as it contained the N-plug inside the pore. Our previous applied force molecular dynamics (MD) simulations suggested that the N-plug was stable inside the pore in the absence of sugar (20), and a similar result was observed with our initial SMD simulation performed with the plugged channel without sugar. The snapshots of the first frame and the last frame were superimposed with RMSD of 1.3 with no ejection of the N-plug, suggesting that the N-plug was stable over the period of the simulation (Fig. S2A). To observe sugar movement inside the channel, SMD simulation was carried out with the plugged pore, the sugar substrate (chitohexaose) being placed on the exterior of the protein pore and the three residues Ala143-Gln146, which are part of loop L3, fluctuated slightly, presumably through the motion of the N-plug (20). However, our SMD simulations did not reveal much movement of L3. We further inspected the crystal structures of the plugged channel without (5MDQ) and with sugar (5MDR) (Fig. S2B), which showed no side chain movement upon sugar insertion, and the distance from the most extended side chain of Tyr147 (13.1 Å) was too far for the N-plug to bond with these residues (Fig. 3C). The main observation was that the reducing end of the sugar chain inserted into the protein pore overlapped with the tail of the N-plug. Superimposition of the sugar molecule in the structure of 5MDR and 7EQR (Fig. S3A) showed the sugar chain interacting with polar residues that mostly bind the N-plug (Fig. S3B). The interactions of the N-plug with these residues were disrupted during sugar protrusion. Figure 7 shows five snapshots, demonstrating considerable motion of the sugar molecule and the N-plug inside the protein pore. Overall, SMD simulation suggested a displacement mechanism in which subsequent interactions of the reducing sugars with the tail of the N-plug assist sugar translocation (20).

Figure 7.

Main snapshots of sugar movement into the plugged pore obtained from SMD simulation from 0 to 700 ps. At t = 0, the sugar chain is stretched on top of the VhChiP pore. At t = 12 ps, the reducing end of GlcNAc-1 has formed a strong H-bond with Asp1. At t = 224 ps, sugar is displaced and Asp6 detached from the channel wall. At t = 240 ps, Lys9 is detached from Glu76. Trp 123(part of L3) and Trp331 (part of L8) are displayed to indicate insignificant change inside chain movement of the pore-lining residues during sugar insertion. At t = 640 ps, the N terminus has been ejected and the sugar released. SMD, steered molecular dynamics.

At t = 0, the sugar chain occupied the extracellular side of the protein pore, with the reducing end sugar ring (GlcNAc-1) located 4.5 Å away from the N-terminal residue (Asp1) of the N-plug. However, (GlcNAc)6 did not interact with any of the residues lining the pore. Asp1 was inserted deepest inside the bottom half of the protein pore, stabilized by H-bonds with the cluster of adjacent pore-lining residues: Glu53, Tyr79, Tyr118, Asp122, Asn127, Arg148, Arg312, and Glu347. Additionally, Asp6 and Lys9 in the N-plug formed other clusters of H-bonds, with Arg55-Asp6-Lys9-Arg94 and Asp6-Lys9-Glu76, respectively.

At t = 12 ps, the chitohexaose chain moved down the pore toward the constriction zone, where the reducing end of GlcNAc-1 formed a strong H-bond with Asp1 of the N-plug, while Asp1 remained bonded to Glu53 and Tyr79.

At t = 224 ps, the sugar chain moved further down the channel lumen, creating a constraint to the N-plug and subsequently caused Asp6 to detach from Arg55 and Arg94.

At t = 240 ps, the sugar completely displaced the N-plug, leaving it ready to be ejected from the protein pore, while GlcNAc-1 remained attached to Asp1. At this time point, Lys9 also detached from the channel wall.

At t = 640 ps, the N-plug was completely ejected, while interactions of the reducing end sugar rings (GlcNAc-1 and GlcNAc-2) with Asp1 (side chain), Gly2 (main chain), and Asp6 (side chain) of the N-plug through a H-bond network may provide additional force for the sugar molecule to be translocated. For more details, the MD simulation movie is attached in the Supplementary (MV1).

Site-directed mutation of Asp1 revealed that the sugar interacted with the tail of the N-plug through H-bonding

To investigate the important role of the N-plug in sugar translocation, we further mutated Asp1 to Ala and conducted electrophysiological and ITC studies of the interaction of the D1A mutant with chitohexaose. Figure 8A shows that all trimers of the D1A mutant were stably open in artificial lipid membranes at the applied potential of ±100 mV. The average conductance of the fully open channel was 200 ± 0.1 nS, which is slightly larger than that of the unmutated channel (Fig. 4A). On titration with chitohexaose on the cis side at concentrations of 0 to 1.0 μM, less frequent monomeric blockages of the ionic current were observed, and the binding curve yielded a K value of 100,000 ± 20,000 M−1, which was 2.5-fold less than that for the WT channel. Figure 8B (upper panel) shows an exothermic thermogram from ITC experiments, obtained by adding chitohexaose to the D1A mutant. Analysis of the fitted theoretical curve of heat integration (lower panel) yielded a Kd value of 1.2 ± 0.2 μM (Table 3).

Figure 8.

Effects of the Asp1mutation on the binding affinity of VhChiP for chitohexaose. Asp1 was mutated to Ala, generating the D1A mutant. A, reconstitution of the D1A mutant into black lipid membrane and occlusion of ion flow upon the addition of chitohexaose at different concentrations to the cis side of the lipid bilayer. Single-channel measurement was carried out as described for the WT and the truncated VhChiPs. Each dataset was acquired at an applied potential of +100 mV in 1 M KCl, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4. Data were acquired over 2 min. Right-hand panels show the corresponding histogram analysis. B, binding studies by ITC are as follows: a thermogram of chitohexaose titration into the D1A channel is shown in the upper panel, while heat integration with nonlinear curve fitting is shown in the lower panel. The state of the channel in lipid membrane under applied voltages is shown as O3 for fully open, O2 for one monomeric closure, O1 for dimeric closure, and C for fully closed. ITC, isothermal titration microcalorimetry.

Discussion

Porins are protein channels found on the OM of Gram-negative bacteria and have a major role in controlling membrane permeability, preventing the entry of noxious compounds, and allowing the entry of nutrient molecules that are required for cell growth and function (21). VhChiP is a chitooligosaccharide-specific channel found in the OM of V. campbellii (formerly V. harveyi) strain American Type Culture Collection BAA 1116. The channel can interact with chitohexaose with high affinity, the binding constant (K) is 250,000 to 500,000 M−1 ((17, 22), and this study). This value is at least one or two orders of magnitude greater than that reported for other sugar-specific channels, for instance maltoporin (LamB) for maltohexaose (13,600 M−1) (23), CymA for cyclodextrin (31,300 M−1) (24), and ScrY for sucrose (80 M−1) (25). The strong binding reflects the remarkable efficiency of the VhChiP channel in recognizing its substrate and coordinating chitooligosaccharide transport. In comparison, we reported the functional characterization of a ChiP homolog (EcChiP) from E. coli (26, 27) and found that EcChiP contained only one subunit, with a single channel conductance (0.5 ± 0.05 nS) only one-third of that in the trimeric VhChiP (2.0 ± 0.1 nS). Kinetic evaluation from single-channel analysis gave a K value for chitohexaose of 50,000 M−1 for EcChiP, which is about 10-fold less than that of VhChiP for the same sugar. The data indicated the role of VhChiP in meeting the physiological requirement of V. campbellii in using chitin as a primary carbon source and a lesser demand by E. coli, which uses chitin only as an alternative energy source.

The structural details suggested that the OM-expressed VhChiP trimers (PDB ID: 5MDQ) were occluded by the N-plug located on the periplasmic side, while these plugs were ejected in the open channel (PDB ID: 5MDO) and the sugar-bound channel (PDB ID: 5MDR), suggesting that the N-plugs controlled the closed/open dynamics of the protein channel (20). The existence of N-plugs was a unique characteristic of the previously described TonB-dependent transporters (28) and oligosaccharide-specific channels (CymA) from Klebsiella oxytoca (29) but was not observed in nonspecific porins or other sugar-specific channels. The existence of the N-plug that acts as a ligand-expelled gate to control channel opening/closing was previously reported for TonB-dependent transporters (28) and cyclodextrin-specific transporter (CymA) (29). For CymA, the crystal structure in complex with cyclodextrin and SMD simulations suggested that bulky cyclodextrin (α-CD) changes its orientation inside the pore from a flat to a linear shape as the molecule travels through a narrow pore and that this disrupts charge–charge interactions between the N-plug and the channel wall, causing the release of the N-terminal plug from the pore.

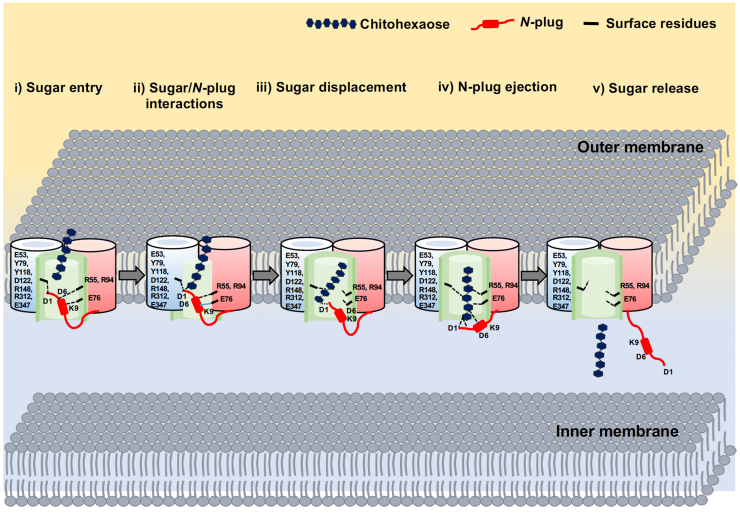

The crystal structures suggested that deletion of the N-plug did not interfere with trimer formation by VhChiP because the three subunits were held together by intramolecular L2–L2 interactions (22). However, the most critical effects were observed in the crystal structures in complex with chitohexaose, where five key H-bonds that are formed with Arg94, Asp135, Asp147, Arg148, and Arg312 around the central affinity sites were missing in the truncated structure (See Fig. 3, residues highlighted in green), leading to a 22.3-fold reduction in the binding affinity for chitohexaose (Table 2). In our previous results, we also demonstrated by proteoliposome swelling assays that truncation of the channel caused a 2-fold reduction in the rate of permeation of bulk sugar molecules, as compared to the WT channel (20). The loss of the H-bond interactions in the structure of truncated VhChiP in complex with sugar and the drastic reduction in the binding affinity as demonstrated by single-channel electrophysiology and ITC binding studies suggested that the N-plug is displaced and subsequently ejected during sugar translocation. The initial interaction of the sugar chain would be through H-bonding with Asp1 at the tail of the N-plug, as is supported by the large reduction in the binding affinity produced by mutation of Asp1 to Ala. The structural details and electrophysiology data, supported by the SMD simulations, suggest that sugar translocation occurs in a multistep process, as shown in Figure 9. Step 1: Sugar entry. Chitohexaose enters the plugged pore and resides in the upper part of the protein lumen, while the N-plug occupies the bottom half of the pore. Step 2: Sugar/N-plug interaction. The incoming sugar moves downward, the reducing end of GlcNAc-1, making contact with Asp1 of the N-plug through a strong H-bond. The interaction between chitohexaose and the N-plug peptide was confirmed by ITC and site-directed mutation studies of Asp1. Step 3: Sugar displacement. The reducing end of the sugar protrudes further, constraining the N-plug and causing Asp6 and Lys9 to detach from the channel wall. Step 4: N-plug ejection. Protrusion of the sugar chain finally expels the N-plug from the pore on disruption of the hydrogen bonds between the sugar molecule and the tail of the N-plug. Step 5: Sugar release. The release of the sugar chain occurs almost simultaneously with N-plug ejection.

Figure 9.

The displacement model of sugar translocation through the VhChiP tunnel based on SMD simulation data. Chitohexaose is shown as a string of hexagonal units (blue), the N-plug is shown in red, dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds, dashed lines with arrows indicate the direction of sugar and the N-plug movement. SMD, steered molecular dynamics.

Concluding remarks

In this study, we determined the crystal structures of truncated VhChiP, lacking the N-plug, in the absence and presence of chitohexaose. Structural analysis of sugar–channel interactions suggested that N-plug deletion led to the loss of five hydrogen bonds that interacted with the GlcNAc moieties at the central affinity site, thus drastically weakening the binding affinity of the truncated channel. SMD simulations suggested that the movement of the sugar molecule along the protein pore ejected the N-plug, while at the same time, hydrogen bonds formed between the reducing end of the sugar chain and the N-plug facilitate sugar translocation. Since several Vibrio species, including V. campbellii, are known to cause severe Vibriosis in marine organisms, such as fish, shrimps, and corals, understanding the mechanistic detail of sugar translocation may help the strategic design of powerful nutrient-based antimicrobial molecules and N-plug mimicking antimicrobial peptides that specially target ChiP channels, as potential therapeutics against Vibrio infections.

Experimental procedures

Gene synthesis, recombinant protein expression, and purification

The chiP gene fragment, encoding the truncated VhChiP lacking the N-terminal amino acids 1-19, was synthesized by GenScript, then cloned into pET23a(+) vector. The chiP gene was designed to exogenously express the truncated channel with an intrinsic 25-aa signal peptide for insertion into the OM of the Omp-deficient E. coli host strain BL21 (DE3) Omp8 Rosetta. The recombinant WT and truncated VhChiPs were expressed and purified, following the protocol reported previously (11). Briefly, transformed cells were grown at 37 °C in LB liquid medium containing 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin, 25 μg mL−1 kanamycin, and 1% (w/v) glucose. At an A600 of 0.6 to 0.8, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Cell growth was continued for a further 6 h, and cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 4500g at 4 °C for 20 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 μg mL−1 DNaseI, and 10 μg mL−1 RNaseA. Cells were lysed by sonication on ice for 10 min using a Sonopuls Ultrasonic homogenizer with a 6-mm diameter probe. The recombinant VhChiP was extracted with 2% (w/v) SDS, followed by incubation at 50 °C for 1 h with gentle stirring and centrifugation at 40,000g at 4 °C for 60 min. VhChiP was extracted from the pellets, which were enriched in OMs, in two steps. In a pre-extraction step, the pellet was washed with 15 ml of 0.125% n-octylpolyoxyethylene in 20 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (ALEXIS Biochemicals), homogenized with a Potter–Elvehjem homogenizer, incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, then centrifuged at 100,000g, 4 °C for 40 min. In the second step, the pellet from centrifugation at 100,000g was resuspended in 10 to 15 ml of 3% (v/v) n-octylpolyoxyethylene in 20 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, then homogenized with a Potter–Elvehjem homogenizer, and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, followed by further centrifugation at 100,000g, 4 °C for 40 min. After exchange of the detergent with 0.2% (v/v) lauryldimethylamine oxide (LDAO, Sigma-Aldrich) by thorough dialysis, VhChiP was further purified by ion exchange chromatography using a HiTrap Q HP prepacked column (5 × 1 ml), connected to an ÄKTA Prime plus FPLC system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Life Sciences Instruments, ITS Co Ltd). Bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 1 M KCl in 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 containing 0.2% (v/v) LDAO. VhChiP-containing fractions were pooled and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 16/600 superdex 200 (GE Healthcare). For site-directed mutation of Asp1 to Ala (mutant D1A), the mutated gene was synthesized and cloned into pET23a(+) vector by GenScript. Gene expression and purification of the D1A mutant was carried out as described above. The purity of the purified proteins was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis. Fractions containing only VhChiP were pooled, and the protein concentration was determined using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Bio-Active Co, Ltd).

Protein crystallization and X-ray data collection and processing

Single crystals of the truncated VhChiP were grown successfully under several conditions from MemChannel and MemTrans Screen kits (Molecular Dimensions Limited). Single crystals of the ligand-free truncated VhChiP appeared in a sitting drop screen plate within 3 days at 291 K in MemTrans Screen kit in condition A2, containing 0.1 M lithium sulfate, 0.1 M N-(2-acetamido)iminodiacetic acid pH 5.2, and 26% (v/v) PEG 400. This condition was chosen for further optimization by varying the pH and PEG 400 concentration of the precipitant. Larger single crystals with an average size of 100 × 200 μm2 (W × L) were finally obtained from microseeding optimization after 3 days of incubation at 298 K. Single crystals of the truncated VhChiP cocrystallized with chitohexaose were also successfully grown in MemChannel Screen kit in condition C7, containing 0.125 M lithium nitrate, 0.1 M glycine pH 9.8, and 45% v/v PEG 400. Single crystals appeared within 5 days at 291 K. This condition was further optimized by seeding, and the final crystal size was on average 100 × 300 μm2 (W × L). Diffraction data were collected on beamline TPS 05A at the NSRRC (100 K at 1 Å). Data were indexed, integrated, and scaled with HKL2000 (30, 31). The structure was determined using MR, and structural factors were anisotropy-corrected. WinCoot (32) was used for manual model building, and the structure was refined with PHENIX (https://hexdocs.pm/phoenix/Phoenix.Endpoint.html) (33).

Single-molecule electrophysiology

Single-channel analysis using the BLM reconstitution technique was performed as described previously (13, 34, 35). A diagram summarizing the BLM setup and the experimental design is shown in Fig. S4. The lipid bilayer cuvette consisted of a 25-μm thick Teflon film sandwiched between two chambers. The film had an aperture of 50- to 100-μm diameter, across which a virtually solvent-free planar lipid bilayer was formed. The chambers were filled with electrolyte solution and Ag/AgCl electrodes immersed on either side of the Teflon film. The electrolyte used was 1 M KCl buffered with 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4. 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (Avanti Polar Lipids) was used for lipid bilayer formation. To form the bilayer, the aperture was first prepainted with 1 μl of 1% (v/v) hexadecane in pentane (Sigma-Aldrich). One of the electrodes was used as the ground (cis), while the other electrode (trans) was connected to the head-stage of an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). VhChiP (20–100 ng μL−1) was added to the solution on the cis side of the lipid membrane. At applied transmembrane potentials of ±100 mV, a single channel was frequently inserted within a few minutes. The protein solution in the chamber was then gently diluted by multiple additions of the working electrolyte, to prevent multiple insertions. Single-channel current measurements were performed in the voltage-clamp mode, with the internal filter set at 10 kHz. Amplitude, probability, and single-channel analyses were performed using pClamp v.10.5 software (https://www.moleculardevices.com/products/axon-patch-clamp-system/acquisition-and-analysis-software/pclamp-software-suite) (all from Molecular Devices). To investigate sugar translocation, chitooligosaccharide was added to the cis side of the chamber at a final concentration of 5 μM. Occlusions of ion flow caused by sugar diffusion through the inserting channel were usually recorded for 2 min. To determine the kinetics of sugar translocation on individual subunit blockages, discrete concentrations of chitohexaose (0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 μM) was tested. To study channel blocking behaviors of the N-plug, the first nine amino acids (Asp1-Lys9) (the so-called N-plug peptide) that plugged the channel was synthesized (GenScript). Two concentrations of the peptide (10 and 40 μM) were added to either the cis or the trans side of the chamber, containing with or without 1 μM of chitohexaose on the cis side.

The equilibrium binding constant K (M-1) was estimated from the decrease in the ion conductance in the presence of increasing concentrations of sugar using the following equation (36):

| (1) |

Gmax is the average conductance of the fully open VhChiP channel, and Gc is the average conductance at a given concentration [c] of chitohexaose. Imax is the initial current through the fully open channel in the absence of sugar, and Ic is the current at a particular sugar concentration. The titration experiments were also analyzed using double reciprocal plots.

Binding study by ITC

ITC experiments were carried out at least three times using the MicroCal PEAQ-ITC (Malvern Instruments Ltd) at 25 ± 1 °C with a stirring speed of 500 rpm. For titration experiments, 40 μl of chitohexaose or the N-plug was titrated from a syringe into the 300 μl-calorimeter cells containing 0.05% (v/v) LDAO, 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, and protein solution. The optimized concentration ratios of chitohexaose and N-plug to VhChiP variants are shown in Table 3. Injections (2 μl per injection) were repeated 19 times over 150-s intervals. The background was measured by injecting the corresponding ligand into the cell containing only the buffer. The ITC data were collected and analyzed using the MicroCal PEAQ-ITC analysis software (https://www.malvernpanalytical.com/en/support/product-support/software/microcal-peaq-itc-analysis-software-v141). The ITC profile obtained by injecting the corresponding ligand into the reaction cell containing buffer without VhChiP was subtracted from the control dataset. The resultant data were fitted by a single-site binding model with the nonlinear least square algorithm.

SMD simulations

The ligand-free, OM-expressed VhChiP (PDB ID: 5MDQ) was used as the starting structure since the N-plug resides inside the pore. Hydrogen atoms were added to VhChiP, while all water molecules, ions, detergents, and other ligands were removed from the crystal structure. Docking parameters were adjusted by default using the automatic genetic algorithm parameter setting in GOLD (37, 38, 39). All amino acid residues of VhChiP located within a 12 Å radius from the extracellular side were selected to define the sugar-binding sites. Iterated cycles of docking simulations were performed, generating 100 possible ligand conformers. All the GOLD docking calculations were further inspected for protein–ligand interactions. The conformer with the highest ChemPLP docking score of 77.5 was selected as the optimal protein-ligand model for MD simulations. The virtual biological system for MD simulations was set by mimicking VhChiP in the lipid membrane (40). The solvation system, containing chitohexaose-bound VhChiP, phospholipid, water, and ions, was prepared using CHARMM-GUI (41, 42). The protein–chitohexaose complex was embedded in a 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine bilayer with TIP3P water and 1 M KCl. Energy minimization was performed using the steepest descent algorithm for 5000 steps, followed by a 5 ns equilibration in the constant-temperature, constant-pressure ensemble (NPT) with positional restraints on the heavy atoms of the proteins and lipids. MD simulations were performed with the GROMACS-2022.2 (https://manual.gromacs.org/2022/install-guide/index.html) (43) using the CHARMM36 all-atom force field (44). The particle-mesh Ewald approach was used to calculate long-range electrostatic interactions with a cut-off of 12 Å. Short-range Coulomb and Lennard Jones interactions were explicitly calculated up to the cut-off distance. The LINCS algorithm was applied to constrain the lengths of all bonds containing hydrogen atoms (45). The simulations were carried out in the NPT ensembles, which could be achieved by a semi-isotropic Parrinello–Rahman barostat (46) at 1 bar with a coupling constant of 5 ps and the Nosé–Hoover thermostat (47, 48) with a coupling constant of 1 ps. Energy minimization was carried out at 303 K to equilibrate the system, which included a sugar–protein complex embedded in phospholipids with water and KCl in the aqueous phase. SMD simulations were run under stabilized parameters, as shown in Fig. S5. The potential energy was initially decreased and became stable after 500 energy minimization steps (Fig. S5A). The solvation system containing phospholipid 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine in the NPT ensembles became well-equilibrated within 5 ns of simulation time with an average temperature of 303.15 ± 0.125 K (Fig. S5B), the average pressure of 5 ± 50 bar (Fig. S5C), and the density of solvation of 1065 ± 2 kg m−3 (Fig. S5D). SMD simulations were subsequently performed to predict the synchronized movements of the chitohexaose chain and the N-plug using GROMACS tools. The sugar chain was pulled by the center of mass away from the active site vestibule. The pulling velocity of 0.01 nm−1 ps−1 and the bias force constant of 750 kJ.mol−1 nm−2 was applied in the unbinding and entry process. One-dimensional reaction coordinates were related to the z-coordinate distance between the center of mass of the sugar molecule. A series of configurations and reaction coordinates across the tubular pore were acquired, generating 650 configurations for every 0.5 Å of the sugar movement.

Data availability

All the data used for this study are available upon request to wipa.s@vistec.ac.th.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the beamline TPS-05A staff who supported X-ray diffraction data collection and processing and the technical services provided by the Synchrotron Radiation Protein Crystallography Facility of the National Core Facility Program for Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, and the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Centre (NSRRC), Taiwan. We would like to acknowledge Dr David Apps, the University of Edinburgh, Scotland for critical reading of the manuscript.

Author contributions

S. S., A. A., and R. R. formal analysis; S. S., A. A., and W. S. writing-original draft; A. A. and W. S. data curation; R. R. writing-review and editing; W. S. methodology; R. R. and W. S. supervision; S. S., A. A., and R. R. investigation; W. S. project administration

Funding and additional information

A. A. was funded by Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology through a Postdoctoral Research Grant. S. S. received a full PhD scholarship from Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology (VISTEC). W. S. was funded by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (SLRI) through Mid-Career Grant and Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology (VISTEC).

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Wolfgang Peti

Supporting information

References

- 1.Austin B., Zhang X.H. Vibrio harveyi: a significant pathogen of marine vertebrates and invertebrates. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2006;43:119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung B.O., Roseman S., Park J.K. The central concept for chitin catabolic cascade in marine bacterium. Vibrios. Macromol. Res. 2008;16:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt D.E., Gevers D., Vahora N.M., Polz M.F. Conservation of the chitin utilization pathway in the Vibrionaceae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:44–51. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01412-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassler B.L., Yu C., Lee Y.C., Roseman S. Chitin utilization by marine bacteria. Degradation and catabolism of chitin oligosaccharides by Vibrio furnissii. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:24276–24286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Songsiriritthigul C., Pantoom S., Aguda A.H., Robinson R.C., Suginta W. Crystal structures of Vibrio harveyi chitinase A complexed with chitooligosaccharides: implications for the catalytic mechanism. J. Struct. Biol. 2008;162:491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suginta W., Chuenark D., Mizuhara M., Fukamizo T. Novel β-N acetylglucosaminidases from Vibrio harveyi 650: cloning, expression, enzymatic properties, and subsite identification. BMC Biochem. 2010;11:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suginta W., Robertson P.A.W., Austin B., Fry S.C., Fothergill-Gilmore L.A. Chitinases from Vibrio: activity screening and purification of chiA from Vibrio carchariae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000;89:76–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suginta W., Vongsuwan A., Songsiriritthigul C., Prinz H., Estibeiro P., Duncan R.R., et al. An endochitinase A from Vibrio carchariae: cloning, expression, mass and sequence analyses, and chitin hydrolysis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;424:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X., Roseman S. The chitinolytic cascade in Vibrios is regulated by chitin oligosaccharides and a two-component chitin catabolic sensor/kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:627–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307645100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keyhani N.O., Li X.B., Roseman S. Chitin catabolism in the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii: identification and molecular cloning of a chitoporin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33068–33076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suginta W., Chumjan W., Mahendran K.R., Janning P., Schulte A., Winterhalter M. Molecular uptake of chitooligosaccharides through chitoporin from the marine bacterium Vibrio harveyi. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keyhani N.O., Roseman S. The chitin catabolic cascade in the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii: molecular cloning, isolation, and characterization of a periplasmic chitodextrinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:33414–33424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winterhalter M. Black lipid membranes. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2000;5:250–255. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iinuma C., Saito A., Ohnuma T., Tenconi E., Rosu A., Colson S., et al. NgcESco Acts as a lower affinity binding protein of an ABC transporter for the uptake of N,N'-diacetylchitobiose in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Microbes Environ. 2018;33:272–281. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME17172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keyhani N.O., Wang L.X., Lee Y.C., Roseman S. The chitin disaccharide, N,N'-diacetylchitobiose, is catabolized by Escherichia coli and is transported/phosphorylated by the phosphoenolpyruvate: glycose phosphotransferase system. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33084–33090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukamizo T., Kitaoku Y., Suginta W. Periplasmic solute-binding proteins: structure classification and chitooligosaccharide recognition. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;128:985–993. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chumjan W., Winterhalter M., Schulte A., Benz R., Suginta W. Chitoporin from the marine bacterium Vibrio harveyi: probing the essential roles of Trp136 at the surface of the constriction zone. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:19184–19196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.660530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suginta W., Smith M.F. Single-molecule trapping dynamics of sugar-uptake channels in marine bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;110 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.238102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suginta W., Chumjan W., Mahendran K.R., Schulte A., Winterhalter M. Chitoporin from Vibrio harveyi, a channel with exceptional sugar specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:11038–11046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aunkham A., Zahn M., Kesireddy A., Pothula K.R., Schulte A., Baslé A., et al. Structural basis for chitin acquisition by marine Vibrio species. Nat. Comm. 2018;9:220. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02523-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aunkham A., Suginta W. Probing the physiological roles of the extracellular loops of chitoporin from Vibrio campbellii. Biophys. J. 2021;120:2124–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilty C., Winterhalter M. Facilitated substrate transport through membrane proteins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;86:5624. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.5624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pajatsch M., Andersen C., Mathes A., Böck A., Benz R., Engelhardt H. Properties of a cyclodextrin-specific, unusual porin from Klebsiella Oxytoca. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25159–25166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen C., Cseh R., Schülein K., Benz R. Study of sugar binding to the sucrose-specific ScrY channel of enteric bacteria using current noise analysis. J. Membr. Biol. 1998;164:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s002329900411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soysa H.S.M., Suginta W. Identification and functional characterization of a novel OprD-like chitin uptake channel in non-chitinolytic bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:13622–13633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.728881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soysa H.S.M., Schulte A., Suginta W. Functional analysis of an unusual porin-like channel that imports chitin for alternative carbon metabolism in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:19328–19337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.812321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noinaj N., Guillier, Barnard T.J., Buchanan S.K. TonB-dependent transporters: regulation, structure, and function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Berg B., Bhamidimarri S.P., Prajapati J.D., Kleinekathöfer U., Winterhalter M. Outer-membrane translocation of bulky small molecules by passive diffusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:E2991–E2999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424835112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Met. Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minor W., Cymborowski M., Otwinowski Z., Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution–from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Cryst. D. 2006;62:859–866. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams P.D., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Hung L.W., Ioerger T.R., McCoy A.J., Moriarty N.W., et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Cryst. D. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller C. Plenum Press; New York: 1986. Ion Channel Reconstitution. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Gelder P., Dumas F., Winterhalter M. Understanding the function of bacterial outer membrane channels by reconstitution into black lipid membranes. Biophys. Chem. 2000;85:153–167. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(99)00153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benz R., Hancock R.E. Mechanism of ion transport through the anion-selective channel of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane. J. Gen. Physiol. 1987;89:275–295. doi: 10.1085/jgp.89.2.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones G., Willett P., Glen R.C., Leach A.R., Taylor R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones G., Willett P., Glen R.C. Molecular recognition of receptor sites using a genetic algorithm with a description of desolvation. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;245:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(95)80037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verdonk M.L., Cole J.C., Hartshorn M.J., Murray C.W., Taylor R.D. Improved protein–ligand docking using GOLD. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2003;52:609–623. doi: 10.1002/prot.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu H., Schulten K. Steered molecular dynamics simulations of force-induced protein domain unfolding. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 1999;35:453–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jo S., Kim T., Iyer V.G., Im W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu E.L., Cheng X., Jo S., Rui H., Song K.C., Dávila-Contreras E.M., et al. CHARMM-GUI membrane builder toward realistic biological membrane simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2014;35:1997–2004. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abraham M.J., Murtola T., Schulz R., Páll S., Smith J.C., Hess B., et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klauda J.B., Venable R.M., Freites J.A., O’Connor J.W., Tobias D.J., Mondragon-Ramirez C., et al. Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H.J., Fraaije J.G. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parrinello M., Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nosé S. A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Mol. Phys. 1984;52:255–268. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoover W.G. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A. 1985;31:1695. doi: 10.1103/physreva.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data used for this study are available upon request to wipa.s@vistec.ac.th.