Abstract

Background

Rare diseases negatively impact patients’ quality of life, but the estimation of health state utility values (HSUVs) in research studies and cost–utility models for health technology assessment is challenging.

Objectives

This study compared the methods for estimating the HSUVs included in manufacturers’ submissions of orphan drugs to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) with those of published studies addressing the same rare diseases to understand whether manufacturers fully exploited the existing literature in developing their economic models.

Methods

All NICE Technology Appraisal (TA) and Highly Specialized Technologies (HST) guidance documents of non-cancer European Medicines Agency (EMA) orphan medicinal products were reviewed and compared with any published primary studies, retrieved via PubMed until November 2020, and estimating HSUVs for the same conditions addressed in manufacturers’ submissions.

Results

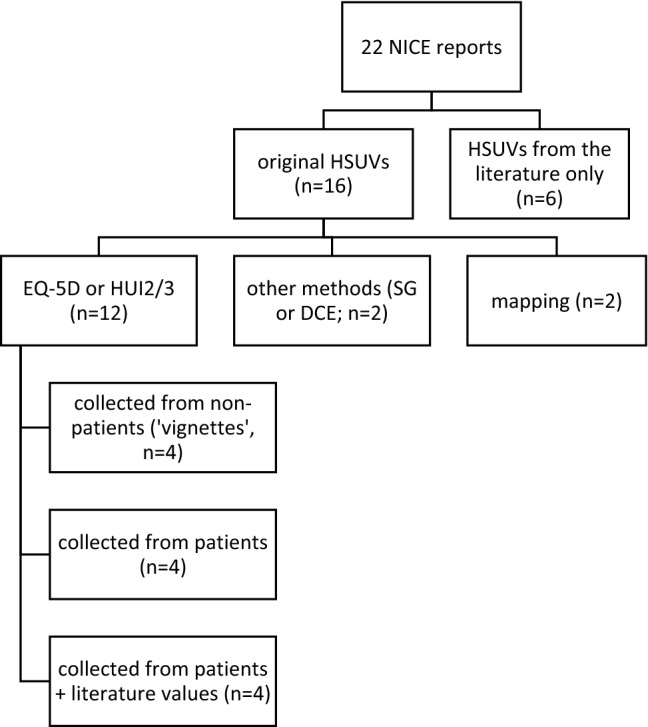

We identified 22 NICE TA/HST appraisal reports addressing 19 different rare diseases. Sixteen reports presented original HSUVs estimated using EQ-5D or Health Utility Index (n = 12), direct methods (n = 2) or mapping (n = 2), while the other six included values obtained from the literature only. In parallel, we identified 111 published studies: 86.6% used preference-based measures (mainly EQ-5D, 60.7%), 12.5% direct techniques, and 2.7% mapping. The collection of values from non-patient populations (using ‘vignettes’) was more frequent in manufacturers’ submissions than in the literature (22.7% vs. 8.0%).

Conclusions

The agreement on methodological choices between manufacturers’ submissions and published literature was only partial. More efforts should be made by manufacturers to accurately reflect the academic literature and its methodological recommendations in orphan drugs submissions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10198-022-01541-y.

Keywords: Health state utility values, Rare diseases, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Technology appraisal, Scoping literature review

Background

Rare diseases (RDs) are defined by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as diseases with a prevalence of fewer than 5 in 10,000 people and affect around 30 million individuals in the European Union (https://ec.europa.eu). These diseases are often severe, life-threatening and/or disabling, characterized by an early onset. As such, they negatively affect patients’ and their carers’ quality of life (QoL) [1], which should be appropriately account for when assessing the benefit of a new medicine. This is usually done via consideration of patient-reported outcome (PRO) data and/or health state utility values (HSUVs).

According to the Food and Drug Administration (US), PROs are defined as ‘any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else’, and a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) as an instrument, usually a questionnaire, that captures PRO data from patients (or proxies) to measure disease impact or drug effects, in a clinical trial or other study [2, 3]. For some PROMs, known as preference-based measures, an algorithm has been developed that converts patient responses into HSUVs based on preferences for specific health states derived from the instrument’s dimensions. HSUVs are single numerical values expressing preference-weighted QoL for particular health states and scored on a scale ranging from 0 (for a state equivalent to ‘dead’) to 1 (for a state equivalent to ‘full health’) [4], although some instruments provide also negative values for health states considered worse than death [5]. Among their applications, they are used for calculating the quality-adjusted life year (QALY), which combines HSUVs and survival data in a single metric and is one of the most preferred outcome measures for health technology assessment (HTA) [4].

A number of methods have been developed to estimate HSUVs, including direct and indirect approaches (i.e., preference-based PROMs). The most common direct techniques include standard gamble (SG) and time trade-off (TTO), where respondents are asked to choose between life with a lower QoL, and life in ‘full health’ with a risk of immediate death (in SG) or a shorter length (in TTO) [6]. A simple approach is represented by the visual analogue scale (VAS), where individuals are asked to rate health by selecting a value on scale where 0 is the worst state they can imagine and 10 or 100 is the best [4]. In recent years, discrete choice experiments (DCEs) have become frequently used to generate HSUVs by asking individuals to choose between hypothetical health states to elicit their preferred health state and the relative weights for various attributes included within health states [7]. The use of an indirect approach through preference-based PROMs is increasingly common and encouraged by many HTA bodies. Six main preference-based generic measures for use in HTA were identified by a recent review [8]: the EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D), the Health Utility Index Mark 2 or Mark 3 (HUI2/3), the Short Form 6 Dimension (SF-6D), the Quality of Well-Being (QWB) scale, the 15D, and the Assessment of Quality of life (AQoL). In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of EQ-5D converted to QALYs to measure the added benefit of new drugs [9]. In detail, companies, academic groups and others preparing evidence submissions for NICE should use the EQ-5D-3L value set for reference-case analyses. If data were gathered using the more recent EQ‑5D‑5L descriptive system, utility values should be calculated by mapping the 5L data onto the 3L value set, until a new high-quality 5L value set for England becomes available [10]. A further approach that is gaining consensus in research and HTA, also accepted by NICE in the absence of EQ-5D data [11], is ‘mapping’ from non-preference-based measures onto preference-based ones (e.g., EQ-5D) using an algorithm previously developed.

The estimation of HSUVs in RDs, however, is challenging. This is because direct techniques may be too demanding for patients, who are often young children or mentally disabled, while generic preference-based instruments may not capture all the relevant symptoms and disabilities, and ‘vignettes’ that describe standard hypothetical health states to non-patient populations may not reflect the heterogeneous manifestations of these diseases [12]. Similarly, the use of mapping in RDs is characterized by difficulties in recruiting sufficiently large samples needed to conduct the regression analysis to derive the algorithm, the limited overlap between the domains included in the disease-specific and generic PROMs, and the poor applicability of algorithms developed for non-rare conditions [13]. Disease-specific preference-based PROMs, which are more sensitive measures, exist for only few RDs (e.g., the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Utility Index, ALSUI) [14]. Caregiver QoL is increasingly considered in HTA, and several carer-specific preference-based instruments have been developed (e.g., ASCOT-Carer and CarerQol-7D) [15, 16]. However, their use and consideration in RDs remain limited [17, 18], even though most diseases affect young children impacting the QoL of those caring for them.

Work Package 10 of the EU Horizon 2020 project IMPACT-HTA (www.impact-hta.eu) aimed to investigate and develop guidance on use of PRO data and HSUVs in RD treatments for HTA. Results suggested PROs and HSUVs sometimes fail to demonstrate change in symptomatology or capture dimensions that really matter to patients, and their estimates are often uncertain and/or of poor quality due to insufficient evidence. The research also pointed to the likely impact of the nature of RDs on the methodological limitations identified, e.g., collecting PROs from paediatric, cognitively impaired, or heterogeneous populations [12, 19].

When preparing their HTA submissions, manufacturers usually review the available literature to identify and derive the parameters for their economic evaluations and/or to learn about methods, such as existing techniques to estimate HSUVs. Given the poor quality of the QoL evidence included in many HTA submissions [18], the question is whether manufacturers are making full use of the available literature, or whether the poor quality might be a consequence of the intrinsic limitations in applying the existing approaches to PRO and HSUV data generation in RDs. In order to answer this question, this paper aimed to further examine the approaches used to derive the HSUVs used in HTA submissions and compare them with the corresponding methodologies and recommendations arising from the literature. This was done by reviewing and comparing the methods used by manufacturers to derive HSUVs in NICE’s appraisal reports of orphan drugs with all published studies addressing the same RDs to understand whether manufacturers fully exploited the existing literature in developing their economic models and derive some related methodological learnings.

Methods

All treatments with an EMA orphan designation and appraised by NICE within their Technology Appraisal (TA) and Highly Specialized Technologies (HST) programmes until June 2020 were included in the study. Specialized or selected high-cost low-volume treatments for very rare conditions are typically evaluated within the HST procedure, while all other treatments undergo the TA process [20]. We excluded appraisal reports for cancer indications given that QALYs are more likely to be driven by survival rather than QoL increases, and any reports for conditions that are not included in the ORPHANET list of RDs [21].

The publicly available appraisal reports were downloaded from NICE’s website (https://www.nice.org.uk/). These reports include a summary of the evidence submitted by the manufacturer, a review of the manufacturer’s submission by an independent Evidence Review Group (ERG), and the Appraisal Committee’s appraisal of the evidence and final decision. The following information was extracted about the manufacturer’s approach(es) embraced to derive the HSUVs used in the economic model(s): type of technique(s) used, number and type of respondents, and literature sources consulted. Subsequent comments, criticisms, and suggestions made by the ERG and/or Committee relating to the techniques used and HSUVs results were also extracted and summarized in order to gain a better understanding of NICE’s opinion of these approaches or of what they would consider reasonable to obtain HSUVs.

We then performed a scoping review of published studies following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [22]. The scoping review was considered appropriate to synthesize the literature as this approach is suggested to map evidence and investigate how research is conducted on a certain topic (i.e., in this study, the estimation of HSUVs in rare diseases) [22, 23]. The aim was to retrieve all primary studies estimating HSUVs in the same indications addressed by the sample of NICE reports identified. An example of the research string used in PubMed is reported below for one NICE appraisal assessing Burosumab for X-linked hypophosphatemia (HST8 [24]):

((Burosumab)[Title/Abstract] OR (X-linked hypophosphatemia)[Title/Abstract]) AND ((health state utility values)[Title/Abstract] OR (utility values)[Title/Abstract] OR (health utilities)[Title/Abstract] OR (preference weights)[Title/Abstract] OR (index values)[Title/Abstract] OR QALYs[Title/Abstract] OR (cost-utility)[Title/Abstract] OR EQ-5D[Title/Abstract] OR EuroQol[Title/Abstract] OR HUI[Title/Abstract] OR (Health Utility Index)[Title/Abstract] OR QWB[Title/Abstract] OR SF-6D[Title/Abstract] OR 15D [Title/Abstract]).

The same string was applied to every drug-disease combination addressed by the NICE reports identified; drugs for the same indication were included in a single string (the full search strategy is reported in Supplementary File 1). The electronic searches were conducted until November 2020. The ScHARRHUD database (https://www.scharrhud.org/) holding bibliographic details of studies reporting HSUVs was also searched. All search results were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet and duplicates removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers and records excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria; full-text papers were retrieved in case of doubtful results. Any disagreement was solved by discussion until a consensus was reached.

The studies deemed eligible for inclusion were those presenting an original approach for estimating HSUVs in any of the conditions of interest, i.e., we excluded those using estimates from previous studies already in the literature. Studies addressing multiple conditions (e.g., post lung transplantation patients) were included provided that at least one subsample of observations was related to the condition of interest (e.g., cystic fibrosis). Studies of any design (i.e., cross-sectional surveys, cohort studies, clinical trials, and cost–utility models) could be included in the review, provided that they showed an original approach to deriving HSUVs. Studies in languages other than English, conference abstracts and study protocols were excluded. Literature reviews were excluded but their reference lists were manually checked in order to identify any additional original studies not captured by the online searches. Similarly, economic evaluations using the published literature to obtain utility parameters for their analyses were excluded, but their reference lists were checked to avoid missing any relevant publications.

For each study, we extracted detailed information regarding the study characteristics (i.e., study design, setting, country, type and number of participants), the method(s) adopted to estimate HSUVs (e.g., direct approaches, such as SG or TTO, indirect approaches using preference-based instruments, such as EQ-5D or mapping), actual HSUVs estimates for the study sample and relevant subgroups, and authors’ methodological considerations regarding the approaches used to estimate HSUVs (if reported). The data extraction form (in Excel) was piloted in parallel by two reviewers on a sample of ten studies, and subsequently refined and completed independently by the first author. The study characteristics were tabulated and subsequently summarized through descriptive statistics (i.e., frequency distribution).

Then, the methods used by manufacturers to derive HSUVs, as reported in the NICE documents reviewed, were compared with those used in the published literature for each indication considered. Specifically, we aimed to understand whether manufacturers relied on the published studies (in the public domain at least one year before the NICE appraisal date) to retrieve HSUVs, or to replicate the techniques adopted to derive HSUVs. Otherwise, we sought to understand if divergences from the existing literature was motivated by the limitations highlighted by study authors’ around the technique(s) adopted and the results obtained. In addition, based on these authors’ methodological considerations, we summarized the key learnings that are important to account for when using each of the available methods to derive HSUVs in individual RDs, and whether the manufacturer’s approach could have better reflected any methodological advice in the existing literature.

Results

Synthesis of NICE technology appraisals

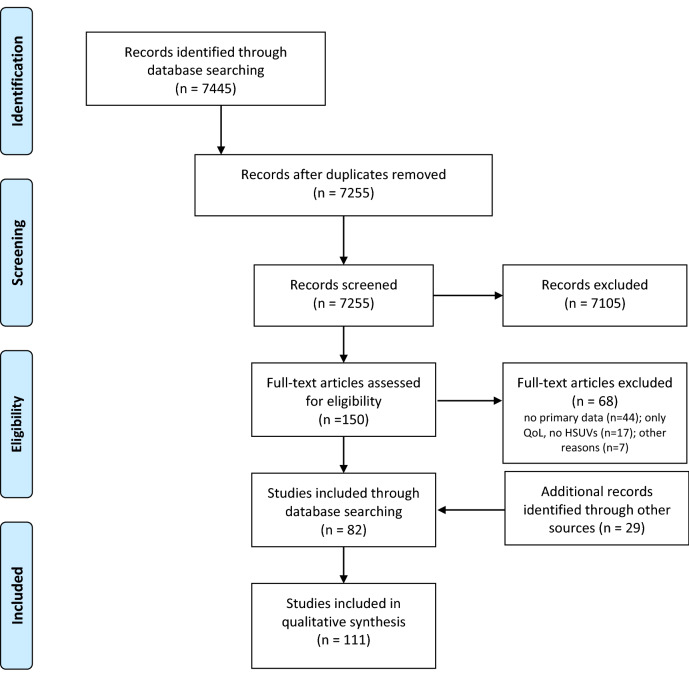

Of the 48 appraisal reports identified from the NICE website, we excluded 24 for cancer indications and two additional reports for Crohn’s and cytomegalovirus disease, since these conditions are not included in the ORPHANET list of RDs. The final sample included 22 TA/HST reports [24–45] for 19 different indications (one indication could have several treatments appraised), published between 2012 and 2019 (Table 1). Across these 22 manufacturer submissions, 16 (72.7%) derived their own HSUVs. Of these, 12 presented original data collection using a preference-based instrument (i.e., EQ-5D in 10 reports, HUI2 in one report, and HUI3 together with EQ-5D in another one). In eight of these (HST1, HST10, TA266, TA398, HST2, TA431, TA491, TA379), questionnaires were filled in by patients within a clinical study, while in the remaining four (HST6, HST8, HST11, HST12) questionnaires were administered to clinical experts to value hypothetical health state descriptions (i.e., ‘vignettes’). In two reports (TA276 and HST5), HSUVs were derived by mapping non-preference-based measures (Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire, CFQ and Short Form-36, SF-36) onto EQ-5D. In one report (HST4), HSUVs were obtained through a discrete choice experiment (DCE), and in another (TA467) through a SG exercise, both performed with the general public. Finally, six reports (HST3, HST7, HST9, TA443, TA588, TA606) did not perform any empirical study, and relied only on literature values and/or expert opinion to obtain HSUVs (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Estimation of HSUVs in RDs: a review of NICE TA/HST guidance documents

| Report code (ref.) | Drug | Manufacturer’s approach | NICE/ERG’s notes/recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Report date | Disease | ||

| HST6 [25] | Asfotase alfa | Mean utility values included in the company’s economic model were estimated by 9 clinical experts who completed the EQ-5D-5L for vignettes for each health state based on the 6MWT severity levels | The ERG felt that deriving HSUVs from clinical experts rather than from clinical studies is a limitation. Moreover, the 6MWT does not capture all the symptoms of hypophosphatasia and the EQ-5D domains, although clinicians may have considered these when providing HSUVs for the illustrative vignettes. However, the HSUVs obtained by the experts seem reasonable. |

| 2/8/2017 | Paediatric-onset hypophosphatasia | ||

| HST1 [26] | Eculizumab | EQ-5D was collected from 37 patients within two clinical studies (C08-002A/B and C08-003A/B) | None |

| 28/1/2015 | Atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome | ||

| HST4 [27] | Migalastat | Complication-related disutilities were derived from a group with Fabry diseases. Infusion-related disutilities were derived from a DCE performed with 506 people from the UK general population. | The ERG noted uncertainty about the comparability of infusion disutilities with those of disease complications given the differences in the methods used for estimation. The ERG did a scenario analysis with utilities derived from alternative sources and reduced infusion-related disutilities. |

| 22/2/2017 | Fabry Disease | ||

| HST9 [28] | Inotersen |

Original approach: published literature (Stewart 2017, which reports EQ-5D utilities using a Brazilian value set). Revised approach: using one or two EQ-5D health states in which the values from the Brazilian data were closest to the mean disease stage values for patients in the preferred THAOS registry (i.e., a global registry owned by another company). |

The ERG argued that using EQ-5D values based on Brazilian general population preferences was questionable because there are important differences in preferences for health states between the UK and Brazilian population. The revised approach, although not optimal, was acceptable for decision-making. |

| 22/5/2019 | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis | ||

| HST10 [29] | Patisiran | The company used the EQ-5D-5L utility values collected in APOLLO trial mapped to EQ-5D-3L (using Van Hout 2012) for a regression model relating HRQoL to PND scores and the interaction between time and treatment | The ERG considered the regression to be unreliable because it excluded important parameters (e.g., cardiac involvement) and included the interaction between time and treatment without the main terms (i.e., time and treatment). |

| 14/8/2019 | Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis | ||

| HST11 [30] | Voretigene neparvovec | Vignettes were developed for each health state using clinicians and patient input. The company then asked six clinicians to complete HUI3 and EQ-5D for each health state in the economic model. The company preferred to use HUI3 because it contains a visual component. | The committee noted that the company’s methods have several serious limitations: (1) small number of clinicians taking part in the vignette study; (2) ophthalmologists may focus on issues related to vision loss, which may have underestimated the overall HRQoL. The ERG suggested using utilities from Rentz 2014, a general public time trade-off study that looked at 8 health states with varying degree of vision problems defined by the NEI VFQ-25 items. The committee considered that neither source of data was sufficiently robust but the HSUVs in the models are likely to fall between the values from Rentz et al. and the EQ-5D company values. |

| 9/10/2019 | Inherited retinal dystrophies | ||

| TA266 [31] | Mannitol dry powder | HUI2 was collected from patients in a clinical trial (DPM-CF-302); literature values were also included for lung transplantation and pulmonary exacerbations. | The committee was concerned by the use of HUI2 instead of EQ-5D that is the preferred measure by NICE and was not convinced that HRQoL of patients had been valued with any certainty. |

| 28/11/2012 | Cystic fibrosis | ||

| TA398 [32] | Lumacaftor–ivacaftor | A multivariate mixed-model repeated measures regression analysis was used to model the relationship between EQ-5D utility values, lung function (ppFEV1) and pulmonary exacerbations reported in TRAFFIC and TRANSPORT trials. Utility values for lung transplants were taken from Whiting 2014. | The committee appreciated that the company had included EQ-5D data, as preferred by NICE. There was no evidence to suggest that the EQ-5D was inappropriate and it generally captured the effects of having cystic fibrosis and its treatment. |

| 27/07/2016 | Cystic fibrosis | ||

| TA276 [33] | Colistimethate sodium and tobramycin dry powders for inhalation | CFQ data collected in a clinical trial were mapped to EQ-5D using published coefficients (Eidt-Koch 2009) | The Assessment Group highlighted the shortcomings in the use of the mapping approach to produce HSUVs. The ERG developed a de novo model deriving HSUVs from the Bradley (2010) study. |

| 27/3/2013 | Pseudomonas lung infection in cystic fibrosis | ||

| HST2 [34] | Elosulfase alfa |

Original approach: HSUVs were based on the general population (asymptomatic state), an observational study of the natural history of MPS IVa using EQ-5D-5L, and cross-sectional surveys of people with the conditions and their families. Revised approach: HSUVs were obtained from the literature. |

The committee noted that the effect of the condition on HRQoL had been assessed using EQ-5D-5L in a natural history study, while the clinical trials on elosulfase alfa collected only limited evidence on HRQoL and did not collect EQ-5D. Therefore, although it was reasonable to include a utility increment with elosulfase alfa, the existing evidence did not allow this benefit to be estimated robustly. |

| 16/12/2015 | Mucopolysaccharidosis type IVa | ||

| HST8 [24] | Burosumab | The company conducted a utility study in which vignettes describing the modelled health states were developed. The vignettes were valued using EQ-5D-5L by 6 clinical experts. An additional value was inferred for the healed health state. | The committed noted that the utilities were scored by clinicians not patients, and were not taken directly from trials, which were limitations of the data. It concluded that the utility values were uncertain but, in the absence of an alternative, were acceptable for decision-making. |

| 10/10/2018 | X-linked hypophosphatemia | ||

| HST7 [35] | Strimvelis | Quality of life data collected in the STRIMVELIS clinical trials were too limited to be included in the model. The company instead used utilities from the literature. No disutility was considered for people having intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or for those who had severe infections. The impact of these assumptions was explored in sensitivity and scenario analyses. | The ERG preferred to incorporate the company's scenario analysis in which a utility weight was applied to people who had IVIG. The committee concluded that, because the ERG's preferred assumptions were based on available evidence, they were preferable for decision-making. |

| 7/2/2018 | Adenosine deaminase deficiency-severe combined immunodeficiency | ||

| TA588 [36] | Nusinersen | The company generated patient utilities from the clinical advisers. The carer-related utilities used by the company assumed that the best health state was associated with general population utility, and the worst health state was the average carer utility from a literature source. | The committee recognised that identifying robust utility values in babies and young children is exceptionally challenging. The ERG considered the company’s approach as the most appropriate. However, it noted that the utility estimates should be considered cautiously because they are not based on formal elicitation methods, may be different if other clinicians valued the health states and may not accurately reflect the view of people with SMA or their carers. Moreover, the estimates of carer utilities used in the model should be treated with caution because most were driven by assumptions rather than by evidence. |

| 24/7/2019 | Spinal muscular atrophy | ||

| TA431 [37] | Mepolizumab | EQ-5D was collected in DREAM trial | The committee noted that the company did not adjust utilities by age because DREAM showed there was no difference between age and utility. The committee considered the ERG's comment that DREAM was not powered to detect age-dependent utilities and noted that there were fewer patients underpinning the data for utilities in older people. The committee concluded that it preferred the ERG's base case, which applied age-adjusted utilities. |

| 25/1/2017 | Severe refractory eosinophilic asthma | ||

| HST5 [38] | Eliglustat | The SF-36 collected in the GD-DS3 score study was mapped to EQ-5D using a published algorithm. The utility increment (0.12) of oral therapy over infusion therapy was taken from a vignette study | The ERG agreed that the GD-DS3 score study provided the most complete set of utility values. It also agreed that oral therapy would provide a clear quality-of-life benefit but questioned the extent of the benefit assumed by the company, even though this was based on a vignette study, and proposed the alternative utility increment of 0.5. The committee concluded that, although the true value was uncertain, the alternative value used by the ERG was more appropriate. |

| 28/6/2017 | Gaucher disease (type 1) | ||

| TA467 [39] | Holoclar | The value of the utility decrement for disfigurement used in the company’s model was taken from a bespoke standard gamble (SG) stated preference exercise in 520 UK participants who were presented with various clinical scenarios describing moderate to severe LSCD, including an image of a patient’s eye with this condition. The estimated utility decrement for disfigurement was consistent with the opinion of clinical experts. | The committee noted that the utility values used in the company’s model were far lower than any used in previous appraisals for eye treatments, noting that ERG had used alternative values. For disfigurement, it used a decrement of 0.140 (rather than the company's assumption of 0.318), using cataracts as a proxy. The committee recognised that cataract disutilities were used as a proxy for disfigurement, and although uncertainty remained in the utilities, the ERG's values were a more realistic reflection of the impact on HRQoL. |

| 16/8/2017 | Limbal stem cell deficiency after eye burns | ||

| TA606 [40] | Lanadelumab | The company used utility values from Nordenfelt 2014, which is a Swedish study that included EQ-5D-5L values for both the attack-free and the attack health states. The company explained that the EQ-5D-5L values collected in the HELP-03 trial were limited and could not be used in the model. | The committee concluded that the company's preferred utility values that included a benefit for lanadelumab subcutaneous administration were acceptable for decision-making |

| 16/10/2019 | Hereditary angioedema | ||

| TA443 [41] | Obeticholic acid | HRQoL data were not collected in POISE trial so the company used utility values from published literature (Younossi 2001 and Wright 2006, used in NICE's technology appraisal guidance on sofosbuvir for treating chronic hepatitis C) | The committee acknowledged the uncertainty associated with the utility values but accepted that they had been derived from published sources |

| 26/4/2017 | Primary biliary cholangitis | ||

| TA491 [42] | Ibrutinib | EQ-5D-5L data were collected in the RESONATE CLL trial. The utility decrements associated with progression and adverse events were based on published literature (Beusterien 2010, Tolley 2013). | Clinical advisors to the ERG noted that given the lack of HRQoL data available for patients with WM, the use of utilities from a CLL study by proxy may be reasonable |

| 22/11/2017 | Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia | ||

| TA379 [43] | Nintedanib | The company assigned utility values to each health state in the model using EQ-5D data collected in the INPULSIS trials | The committee approved of the company using trial-based EQ-5D data to estimate HSUVs |

| 27/1/2016 | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | ||

| HST3 [44] | Ataluren | The company model included HRQoL data from the literature (Landfeldt et al. 2014) to inform the utility values for patients and carers | The committee concluded that it is imperative that its future review includes carer utility data |

| 20/7/2016 | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | ||

| HST12 [45] | Cerliponase alfa | The company commissioned a utility study in which vignettes describing health states for both cerliponase alfa and standard care were developed. The vignettes were validated by a clinical expert and sent to 8 clinical experts who completed the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire as a proxy for patients. These were mapped to the EQ-5D-3L before being applied in the model. The company also included disutilities for carers and siblings. | The committee was concerned about the robustness of the vignettes used to elicit these utility values. It noted that they contained additional disease elements that had an unclear association with the motor and language scale that defined the health states. However, it concluded that, in the absence of further evidence, it would consider EQ-5D-3L values estimated from the utility study using vignettes. The committee was satisfied with the principle of including disutility values for carers and siblings but agreed with the ERG that applying them for the whole 95-year time horizon was unrealistic given the life expectancy of parents, and also because disutility may change as siblings grow up and move on. |

| 27/11/2019 | Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 |

6MWT 6-min walk test, CFQ cystic fibrosis questionnaire, CLL chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, EQ-5D EuroQol-5 Dimension, EQ-5D-Y EuroQol-5 Dimension-Youth, ERG Evidence Review Group, HRQoL health-related quality of life, HST highly specialized technology, HSUVs health state utility values, HUI Health Utility Index, LSCD limbal stem cell deficiency, SMA spinal muscular atrophy, NEI VFQ National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire, NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, PND polyneuropathy disability, TA technology appraisal

Fig. 1.

Synthesis of methods used by manufacturers to obtain HSUVs (as reported in NICE TA/HST guidance documents)

In total, the use of ‘vignettes’ was reported in five cases (22.7%), of which four (HST6, HST8, HST11, HST12) using EQ-5D or HUI2/3, and one (TA467) SG, and ten reports (HST9, TA266, TA398, HST2, HST7, TA588, TA606, TA443, TA491, HST3) referred to published studies to obtain some or all HSUVs for their analyses. Cumulatively, 15 cases (68.2%) reported EQ-5D utilities obtained with different approaches: seven (HST1, HST2, HST10, TA379, TA398, TA431, TA491) collecting data directly from patients, four (HST6, HST8, HST11, HST12) using ‘vignettes’ to be valued by clinical experts, two (HST9, TA606) referring to published studies, and other two (HST5, TA276) using ‘mapping’.

The Committees and/or the ERG appraised six cases positively, where the HSUVs were derived either from EQ-5D data collected within a trial, or from different approaches considered to be reasonable (HST1, TA398, TA606, TA443, TA491, TA379). In 10 cases (HST2, HST3, HST5, HST6, HST8, HST9, HST11, HST12, TA431, TA588), the Committees highlighted several limitations in the approach used by the manufacturer (i.e., surveys of clinical experts instead of patients, small samples, EQ-5D value sets from other countries, data collected within observational studies instead of trials, vignettes with unclear disease elements) but recognized that these could be acceptable with some adjustments and/or cautious consideration of results. In the remaining six reports (HST4, HST10, TA266, TA276, HST7, TA467), the Committees were more sceptical about the approach adopted, considering that it might yield unrealistic HSUVs estimates. Consequently, they often preferred to rely on alternative de novo approaches developed by the ERG.

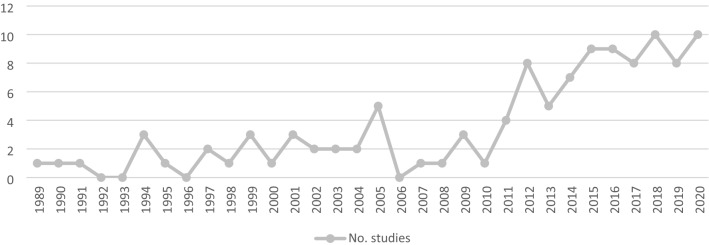

Literature search results

In total, the search strategy in PubMed identified 7445 articles. After removing 190 duplicates, 7255 records were scanned for title/abstract and 7105 were excluded in this first phase. Subsequently, 150 full-text articles were retrieved, and a further 68 records were excluded for not complying with the inclusion criteria. The two main reasons for exclusion were that the study evaluated QoL but did not estimate HSUVs, or that the study used HSUVs from the literature. Accordingly, 82 studies were selected, plus 29 studies identified through manual searches, resulting in a total of 111 studies included in the review [46–156]. No additional articles were obtained from the ScHARRHUD database (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram showing study selection

Synthesis of published studies

The 111 studies estimated HSUVs in the same RDs addressed by the NICE reports (Tables 2, 3). One study [152] was reported twice since it addressed two different conditions, thus leading to the consideration of 112 different studies. At least one study was identified for each RD addressed in the NICE reports, with the exceptions of paediatric-onset hypophosphatasia and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. The highest number of publications were retrieved for cystic fibrosis (n = 36, 32.1%), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (n = 16, 14.3%), and Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD, n = 10, 8.9%).

Table 2.

Estimation of HSUVs in RDs addressed by NICE TA/HST guidance documents: results from the literature review

| Report code (date) Drug/disease |

First author (year) [ref.] | Study design/main purpose | Sample size (country) | Technique(s) to derive HSUVs | Main findings (HSUVs estimates) | Authors’ methodological considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HST1 (28/1/2015) Eculizumab/ Atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome |

Fakhouri (2016) [76] | Open-label single-arm phase 2 trial of eculizumab to assess its efficacy in inhibiting complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) | 38 patients of 18 years or older with AHUS (US) | EQ-5D (US value set) | Mean change from baseline was significant (p < 0.001) | None | |

| Legendre (2013) [103] | Two prospective phase 2 trials of eculizumab to assess the changes in the platelet count (trial 1) and TMA event-free status (trial 2) | 35 patients of 12 years or older with AHUS (Europe and US) | EQ-5D | Mean increase in EQ-5D score at week 26: trial 1: 0.32 (95% CI, 0.24–0.39; p < 0.001); trial 2: 0.10 (95% CI, 0.05–0.15; p < 0.001) | None | ||

| Licht (2015) [105] | Extension of two phase 2 studies of eculizumab (Legendre 2013) to assess outcomes after 2 years | 32 patients of 12 years or older with AHUS (Europe and US) | EQ-5D | Baseline median EQ-5D (range): trial 1: 0.8 (0.3–1.0); trial 2: 0.9 (0.2–1.0). Eculizumab significantly improved the EQ-5D score over 2 years (p < 0.05 compared with baseline) | None | ||

|

HST4 (22/2/2017) Migalastat/Fabry Disease |

Arends (2018) [51] | Retrospective cohort study to assess HRQoL | 286 patients (NL and UK) | EQ-5D-3L (Dutch and UK preference weights) | Mean EQ-5D index score: 0.77 (± 0.26) | The EQ-5D offers three answer options per domain, limiting the detection of small changes in health | |

| Beck (2004) [54] | Cohort study to monitor the long-term effects of ERT with agalsidase alfa on renal function, heart size, pain and QoL | 545 patients (11 European countries) | EQ-5D-3L (UK preference weights) | There was a significant improvement in the EQ-5D utility score during the first year of treatment with agalsidase alfa (p < 0.05) | None | ||

|

HST4 (22/2/2017) Migalastat/Fabry Disease |

Hoffmann (2005) [88] | Prospective study to evaluate pain and its influence on QoL in patients with Fabry disease receiving ERT with agalsidase alfa using data from the Fabry Outcome Survey (FOS) | 314 patients with Fabry disease receiving ERT with agalsidase alfa and registered on the FOS European database | EQ-5D-3L | The mean EQ-5D utility score prior to ERT was 0.66 (0.32, n = 120). After 12 months of treatment with agalsidase alfa, this had improved to 0.74 (0.26; n = 59; p < 0.05); this improvement was maintained after 2 years (n = 28) | The EQ-5D has some limitations. It was established to detect and to measure changes in HRQoL reported by the patient; therefore, improvement of HRQoL does not imply improvement in an individual’s physical health state, but an improvement in the patient’s perception of their health state. | |

| Mehta (2009) [114] | Analysis of the Fabry Outcome Survey (FOS) observational database to assess cardiac mass and function, renal function, pain and QoL | 181 adult patients from 19 countries | EQ-5D | HRQoL, measured by mean (SD) deviation scores from normal EQ-5D values, improved significantly, from –0.24 (0.3) at baseline to –0.17 (0.3) after 5 years (p = 0.0483) | None | ||

| Miners (2002) [115] | Baseline data of a trial involving replacement therapy with a-galactosidase to assess HRQoL | 38 males with AFD (UK) | EQ-5D | Mean (SD) EQ-5D utility: 0.56 (0.35). Mean (SD) EQ-VAS: 24.3 (31.1) | None | ||

| Ramaswami (2012) [128] | Use of registry (Fabry Outcome Survey, FOS) data to validate FPHPQ | 87 children (4–18 years) from eight countries | EQ-5D | EQ-5D utility (mean ± SD): 1.00 ± 0.00. EQ-VAS: 1.11 ± 0.31 | Because Fabry Disease is a rare disease, it was necessary to pool data of multiple languages to be able to include patients with a wide range of disease severity and to ensure a sufficient sample size for data analysis | ||

|

HST4 (22/2/2017) Migalastat/Fabry Disease |

Rombach (2013) [131] | Cost-effectiveness analysis of ERT compared to standard medical care | 142 patients aged 5–78 years (Netherlands) | EQ-5D-3L (UK preference weights) | Mean (95% CI) EQ-5D utility: asymptomatic: 0.874 (0.804–0.934); acroparesthesia (symptomatic): 0.762 (0.699–0.822); single complication: 0.744 (0.658–0.821); multiple complications: 0.584 (0.378–0.790); total: 0.772 (0.729–0.815) | None | |

| Tsuboi (2012) [144] | Prospective observational study (6-month intervals assessments) to assess the feasibility of switching patients on agalsidase beta treatment to agalsidase alfa instead in terms of renal function, cardiac mass, pain, QoL, and tolerability/safety | 11 patients (Japan) in whom the treatment was switch from agalsidase beta to agalsidase alfa | EQ-5D-3L | The EQ-5D index score confirmed the stabilization of Fabry disease relative to pre-switch values | None | ||

| Wyatt (2012) [152] | Cost-effectiveness analysis of ERT for lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) | 311 patients (UK) | EQ-5D and SF-36 derived (SF-6D) (UK preference weights) | None | None | ||

|

HST9 (22/5/2019) Inotersen/Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis |

Inês (2020) [89] | Prospective cohort study to assess HRQoL | 621 asymptomatic carriers and 733 symptomatic patients (Portugal) | EQ-5D-3L (Portuguese value set) | Among patients, the utility value is estimated to be 0.51 (0.021), a decrement of 0.27 as compared with general population utility. No differences on utility were found between carriers and general population (p = 0.209) | EQ-5D-3L is a valid instrument in assessing HRQoL among hATTR-PN patients. Difficulties remain due to disease rarity and small samples | |

| HST10 (14/8/2019) Patisiran/Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis | Obici (2020) [119] | Randomized placebo-controlled trial (APOLLO) of patisiran to describe its impact on QoL | 225 patients (n = 148, patisiran; n = 77, placebo) from 21 countries | EQ-5D-5L | EQ-5D score: baseline: 0.6 (0.2) in both groups; at 18 months: + 0.2 in patisiran). EQ-VAS: baseline: 55.7 (20.0) for patisiran and 54.6 (18.0) for placebo; at 18 months: + 9.5 for patisiran | QoL tools used in APOLLO were appropriate measures for this disease | |

| Wixner (2014) [151] |

Use of baseline data from a global, multicentre, longitudinal, observational survey (Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey, THAOS) to explore the prevalence and distribution of gastrointestinal manifestations in transthyretin amyloidosis and to evaluate their impact on HRQoL |

1579 patients from seventeen countries | EQ-5D (US value set) | Gastrointestinal symptoms were significant negative predictors of the EQ-5D index score | None | ||

|

HST11 (9/10/2019) Voretigene/Inherited retinal dystrophies |

Brown (1999) [61] | Cross-sectional study to determine the relationship of visual activity loss to QoL | 325 patients (included 1 with x-linked retinoschisis) in the US | Standard gamble and time trade-off | Utilities associated with the better-seeing eye [mean (SD)]: SG: 0.85 (0.21); TTO: 0.77 (0.23) (p < 0.001) | It is the opinion of the author that patients understand the TTO concept more readily than the SG concept. Additionally, as was the case in this study, evidence has shown that the SG method overestimates risk aversion. | |

|

HST11 (9/10/2019) Voretigene/Inherited retinal dystrophies |

Davison (2017) [70] | Prospective cohort study to explore the feasibility of delivering standardized genomic care and of using selected measures to quantify its impact on patients | 98 patients with IRD and receiving standardized multidisciplinary care (UK) | EQ-5D-3L (UK preference weights) | EQ-5D (complete case; n = 51): baseline: 0.747; 1 month: 0.744; 3 months: 0.794. EQ-5D (multiple imputation; n = 98): baseline: 0.778; 1 month: 0.776; 3 months: 0.810 | Because the EQ-5D displayed considerable ceiling effects, further empirical work is needed to determine whether it is suitable for use in populations with genetic eye conditions. However, having the data enables comparisons across populations and health conditions. | |

| Lloyd (2019) [107] | Cross-sectional study to develop health state descriptions of RPE65-mediated IRD and to estimate associated patient utilities | 6 ophthalmologists (US) | (1) Development of vignettes through background materials, feedback from an expert advisory board meeting, and interviews with clinical specialists, patients, and caregivers. (2) Proxy evaluation of vignettes by retina specialists with additional expertise in IRDs by using EQ-5D-5L (mapping to 3L UK value set) and HUI3 | The EQ-5D-5L weights ranged from 0.709 for moderate vision loss to 0.152 for hand motion to no light perception (NLP). The HUI3 weights ranged from 0.519 to −0.039, respectively. A decline was seen on both measures, and the degree of decline from moderate vision loss to NLP was identical on both (− 0.56) | Given the ultra-rare nature of RPE65-mediated IRD, it was not feasible to recruit a patient sample and collect HRQL data prospectively. The qualitative picture that informed the vignettes supports the face validity of the utility findings. Clinicians were favoured over the general public for rating vignettes because the experience of severe vision loss may be difficult for the public to imagine. It also allowed describing some specific clinical information that may not be readily understood by the general public. The utility values are low, especially for the more severe states, and the qualitative work supported these scores. | ||

|

TA266 (28/11/2012) Mannitol dry powder/cystic fibrosis |

Acaster (2015) [48] | Cross-sectional survey to develop a mapping algorithm to estimate EQ-5D utility values from CFQ-R data | 401 patients with CF (UK) | Mapping from CFQ-R to EQ-5D-3L (UK preference weights) | The mean EQ-5D score was 0.67 (SD: 0.28), ranging from –0.35 to 1 | There was a tendency of over prediction in all models for observed values of EQ-5D lower than 0.3, and to a lesser extent, under prediction above observed EQ-5D values above 0.9. the respiratory symptoms domain was not a significant predictor of EQ-5D utility in any of the models. Given the focus of respiratory symptoms in CF trials it may be worth exploring the potential to increase sensitivity in utility scores by developing a condition-specific preference-based measure. | |

|

TA398 (27/07/2016) Lumacaftor–ivacaftor/cystic fibrosis |

Angelis (2015) [49] | Cross-sectional retrospective analysis to determine the societal economic burden and HRQoL of CF patients in the UK | 74 patients with CF (UK) | EQ-5D-5L collected from patients or caregivers (UK preference weights) | Patients: mean EQ-5D index score: 0.64; EQ-VAS: 62.23. Caregivers: 0.836 and 80.85 | The EQ-5D-5L can be considered a cross-sectional valid generic health outcome measure reflecting the progression of CF | |

|

TA276 (27/3/2013) Colistimethate sodium and tobramycin dry powders for inhalation/Pseudomonas lung infection in cystic fibrosis |

Anyanwu (2001) [50] | Cross-sectional study to examine the applicability of EQ-5D to the assessment of HRQoL in lung transplantation | 87 patients awaiting lung transplantation and 255 transplant recipients (UK) | EQ-5D-3L (UK preference weights) | Waiting list: mean (SD) VAS: 35 (19); utility score: 0.31 (0.31). Post-transplantation: mean (SD): 0–6 months: VAS: between 67 (17) and 79 (10); utility score: between 0.67 (0.15) and 0.69 (0.31); 7–18 months: VAS: between 65 (17) and 79 (17); utility score: between 0.66 (0.21) and 0.85 (0.17); 19–36 months. VAS: between 65 (20) and 79 (13); utility score: between 0.65 (0.24) and 0.86 (0.12); > 36 months: VAS: between 60 (19) and 79 (19); utility score: between 0.61 (0.31) and 0.87 (0.20) | This study has shown that QoL in all five EQ-5D domains is better in the transplanted group than in those on the waiting list, which suggests that the EQ-5D is responsive to changes in QoL resulting from symptomatic improvement after lung transplantation | |

| Bell (2019) [55] | Cross-sectional study to investigate the impact of ivacaftor (IVA) and standard of care (SOC) on HRQoL in groups of CF patients with G551D and F508del mutations | 209 patients with CF aged ≥ 12 years, or aged 6–11 years with caregiver support (France, UK, Germany, Australia, and Ireland) | EQ-5D-5L | G551D/IVA group (n = 72): mean (SE) EQ-5D index score and VAS: 0.90 (0.02) and 75.7 (1.8). F508del/SOC group (n = 137): 0.81 (0.02) and 70.0 (1.4) | The simplicity and low costs associated with the EQ-5D-5L confer potential for more widespread use and capture of longitudinal data | ||

| Bleisch (2019) [57] | 3-year cohort study to assess HRQoL trajectories after lung transplantation | 27 lung transplants recipients, of which 11 with CF and 4 with IPF (Switzerland) | EQ-5D-3L | Mean (± SD): pre-transplant: 70.43 (± 17.70); two weeks post-transplant: 62.17 (± 25.75); three months post-transplant: 85.22 (± 15.04); six months post-transplant: 87.39 (± 13.22); three years post-transplant: 89.57 (± 12.24) | EQ-5D is a generic, preference-based measure. A disease-specific measure could be more sensitive to health changes than a generic one. The EQ-5D was chosen as the outcome measure due to its being easy to complete and its previous use in lung transplant recipients. | ||

| Bradley (2013) [59] | Longitudinal study to discover the health status and healthcare utilization associated with PEs in CF | 94 patients (aged ≥ 16) with CF and chronic P. aeruginosa (UK) | EQ-5D-3L (UK preference weights) | EQ-5D utility index means were 0.85, 0.79 and 0.60 for no, mild and severe PEs, respectively | The EQ-5D correlated strongly with disease-specific domains of the CFQ-R. The EQ-5D allows for comparisons with other respiratory populations and QALY calculation for cost-effectiveness analyses of inhaled antibiotics treatments in CF. | ||

| Busschbach (1994) [62] | Retrospective cohort study to measure the QoL before and after bilateral lung transplantation in patients with CF | 6 patients with CF before and after lung transplantation (Netherlands) | Standard gamble, time trade-off, EQ-VAS | In general, the utility of the health states decreases when one has entered the transplant window. After transplantation, the utility increases to a level above the health state before the transplant window | The standard gamble seems to produce the highest values for the health states. The EQ-VAS produces relatively low values. | ||

| Chevreul (2015) [67] | Retrospective cross-sectional study to estimate the economic burden and HRQoL associated with CF in France | 166 patients (75 adults and 91 children aged above 5) with CF and 40 carers (France) | EQ-5D-5L collected from patients (or their legal representative in 81 children) and carers (mapping from the French EQ-5D-3L value set) | The average utility for a patient with CF was 0.730 and lower in adults (0.667 vs. 0.783 in children, p = 0.0015). The average utility for carers was 0.761 with no difference if they looked after an adult or a child (utility of 0.742 and 0.765 respectively, p = 0.7904). The average VAS was 71.9 for patients and 78.95 for carers | The advantage of the EQ-5D is that it is a generic tool which allows researchers to elicit country-specific utilities which can then be used in cost-effectiveness analysis and decision-making, but the questionnaire was developed for an adult population and is meant to be self-reporting. However, other studies have used the EQ-5D in children and parent-proxy ratings have also been shown to be both feasible and valid. | ||

| Chevreul (2016) [66] | Cross-sectional study to estimate the economic burden and HRQoL of patients with CF and their caregivers in Europe | 649 patients (357 adults and 292 children) and 271 caregivers from eight European countries | EQ-5D collected from patients and caregivers (country-specific value set when available) | In adults, mean utility fell between 0.640 and 0.870, and VAS between 46.0 and 69.7. Mean utility in caregivers was between 0.663 and 0.919 (VAS: 61.5–84.9) | The use of the EQ-5D has the advantage that it is a generic tool which allows researchers to elicit country-specific utilities which can then be used in cost-effectiveness analysis and decision-making | ||

| Czyzewski (1994) [69] | Baseline data of an observational study assessing the impact of an educational intervention for patients with CF and their families to determine the validity of QWB scale | 199 patients (younger than 18 years) and their primary caregiver (US) | QWB | QWB (total score): caregiver report (n = 199): mean (± SD): 0.79 (± 0.09); adolescent report (n = 55): 0.76 (± 0.08) | The low to moderate correlations between QWB scores from parent and adolescent reports suggest that respondents are not interchangeable. In general, overall correlations between the QWB and other indicators of physical and psychosocial functioning were low. These call into question the use of QWB as outcome measure in the paediatric CF population. | ||

| Dewitt (2012) [72] | Analysis of data collected alongside a 48-week multicentre clinical trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of denufosol vs placebo to characterize resource use, direct medical costs, indirect costs, and utilities | 352 participants (5 years or more), US and Canada | HUI2/3 completed by participants (if aged above 14) or by parents /caregivers as proxies for participants aged below 14; VAS (0–100) | HUI2/3 utility score [mean (SD)]: 0.90 (0.14); VAS: 88.3 (12.2). Mean (95% CI) change at 48 weeks: HUI2/3: 0.01 (–0.013; 0.031); VAS: 1.4 (–0.47; 3.33) | None | ||

| Dunlevy (1994) [74] | Longitudinal study (8 weeks) to assess the effect of low impact aerobic exercise on patients work capacity, oxygen uptake and QoL | 6 patients (US) | QWB | Mean (± SD) QWB: pre-exercise: 0.74 ± 0.09; post-exercise: 0.74 ± 0.02 (p = 1) | The lack of improvement in QWB may be related to the relative weight of the symptom/problem subscale, since only the perceived worst symptom/problem contributes to the rating | ||

| Eidt-Koch (2009) [75] | Cross-sectional multi-centre study to evaluate the validity of the EQ-5D-Y as a generic health outcome instrument in children and adolescents with CF | 96 patients (between 8 and 17 years) in Germany | EQ-5D-Y | Several low to strong correlations between the dimensions of the EQ-5D-Y and the scales of the CFQ for children, their parents and adolescents could be found. The mean VAS for 8–13-year-old patients was 85.4 (SD 16.4), the mean VAS for 14–17-year-old patients was 79.4 (SD 13.2) | The EQ-5D-Y can be considered a cross-sectional valid generic health outcome instrument which reflects differences in health according to the progression of the life-long chronic disease CF | ||

| Fitzgerald (2005) [78] | Crossover, randomized, and placebo-controlled trial of dornase alpha before and after physiotherapy to assess the change in predicted % of FEV1, a composite QWB score, and the maximum oxygen consumption, determined using a shuttle testing | 52 patients (5–18 years) in Australia | QWB | A significant period effect was demonstrated in QWB (p = 0.03), suggesting that on average a higher quality of well-being was achieved in period 1 (visit 2: least squares mean = 0.778; standard error = 0.008), compared with period 2 (visit 4: least squares mean = 0.752; standard error = 0.008) | None | ||

| Fitzgerald (2018) [77] | Cross-sectional study to examine the caregiver burden in mothers and fathers of young children with CF | 189 mothers and 137 fathers of young children with CF (Ireland) | CarerQoL-7D + VAS (0–10). The utility score (US) is a weighted average of the subjective burden derived from the CarerQol-7D (0–100) using utility wights from the UK population (higher US indicates less burden). | Fathers had a significantly higher median utility and VAS scores than mothers [utility: 89.2 (IQR: 79.6–96.5) vs. 84.7 (IQR: 74.5–88.0) p < 0.001; VAS: 8.0 (IQR: 7.0–9.0) vs 7.0 (IQR: 6.0–9.0)] | This study found that the CarerQol was a concise questionnaire easily completed by parents and appears to have some external validity | ||

| Gold (2019) [81] | Use of a pilot observational trial/prospective observational cohort study (STOP study) data to evaluate associations between 8 symptom-based questions from the CFRSD–CRISS and the EQ-5D-5L summary score | 169 patients with PEs in CF from 11 US centres | EQ-5D-5L (US population weights) | The study did not find significant correlations between the CFRSD-CRISS and EQ-5D-5L summary scores | The EQ-5D-5L alone is not a meaningful way to assess quality-of-life in future cost-effectiveness studies among CF patients with PEs. Other preference-weighted measures besides the EQ-5D-5L could be explored, such as the SF-6D, the HUI3, or perhaps a CF-specific instrument that is preference-weighted. | ||

| Groen (2004) [82] | Cost–utility study of lung transplantation | (number of patients not specified) Netherlands | EQ-5D | On the waiting list, average utility values were 0.55 during the first 6 months, 0.50 between 6 and 9 months, 0.45 between 9 and 12 months, and 0.40 after 1 year. After transplantation, average utility values ranged from 0.69 1 month after transplantation to between 0.83 and 0.85 from 3 to 12 months after transplantation. During the next year, utility rose to 0.91. In any phase, the utility during the final 3 months before a patient died was 0.31 | None | ||

| Iskrov (2015) [90] | Cross-sectional study to determine the economic burden and HRQoL of patients with CF | 23 patients and 17 caregivers (Bulgaria) | EQ-5D-3L (UK value set) | Median health utility: patients: 0.592 (IQR: –0.385 − 0.768); carers: 0.725 (IQR: 0.516 – 0.822). Median VAS: patients: 50 (IQR: 10 – 80); carers: 70 (IQR: 40 – 83) | None | ||

| Janse (2005) [92] | Cross-sectional study to investigate the differences in perception of HRQoL between parents of chronically ill children and paediatricians | 37 paediatricians and 279 parents of children with chronic conditions (including CF) in the Netherlands | HUI3 | The agreement between parents and paediatricians for the overall utility score was 9%. Parents: 0.80 (median); –0.15 to 1.00 (min–max). Paediatricians: 0.93 (median); –0.13 to 1.00 (min–max) | None | ||

| Janse (2008) [91] | Cross-sectional study to investigate the differences in perception of HRQoL among children, parents, and paediatricians | 19 paediatricians and 60 chronically ill patients (aged 10–17), including 22 CF patients, and their parents (Netherlands) | HUI3 | Overall utility score: paediatrician: 0.88; parent: 0.76; child: 0.69 | We have chosen the HUI3 because we expected the attributes of the HUI3 to match well with major complaints of these patients. Hearing could be affected by the use of antibiotics and therefore could be relevant in patients with CF. | ||

| Johnson (2000) [93] | Prospective observational study to examine the HRQoL of adults with CF using available generic instruments | 59 adult patients (Canada) | EQ-5D-3L (UK value set) | EQ-VAS scores (74.4) were generally lower than published normal scores for this instrument (Alberta general population norms: 81.8) | None | ||

| Munzenberger (1999) [116] | Longitudinal study to determine the responsiveness and validity of the QWB scale in children and adolescents with CF | 20 children and adolescents with CF (US) | QWB | Mean (SD) QWB: before treatment: 0.611 (0.075); after treatment: 0.701 (0.07); 6 months: 0.672 (0.085); 12 months: 0.672 (0.066) | We found a significant increase in QWB scores from before to after treatment of an acute exacerbation of pulmonary disease, suggesting that the scale is a responsive measure of quality-of-life outcome of such an event. However, the QWB scale is a generic QoL instrument and may not be sensitive enough to detect changes in function domains in patients with CF. In addition, the number of patients involved in this trial was relatively small. A much larger sample may be required to detect differences in function scores when using this instrument. We conclude that the QWB scale shows both responsiveness and validity during an acute exacerbation of pulmonary disease in patients with CF. This study is limited primarily by the small number of patients. We suggest additional studies to investigate responsiveness, reproducibility, and longitudinal validity of the QWB scale. | ||

| Orenstein (1989) [122] | Cross-sectional study to establish the construct validity of the QWB scale in CF patients | 44 patients (7–36 years) in US | QWB completed by patients (if aged above 14) or by patients and parents togethers (if aged between 10 and 14) or by parents (if aged below 10) | None (only correlations coefficients) | The QWB scale is an objective measure that is significantly correlated with measures of performance and pulmonary function and has substantial validity as an outcome measure in CF patients | ||

| Orenstein (1990) [121] | Longitudinal study (before and after 2-week treatment) to see if the QWB scale could capture change over time | 28 patients (aged > 10 years) in US | QWB | QWB scores generally improved, with a mean change of 0.104 ± 0.122 | The QWB can track changes in general well-being in CF patients over a brief time and detect changes associated with PE and its treatment and allows for comparison with other conditions | ||

| Orenstein (1991) [120] | Case report study to evaluate change in overall wellbeing over time | 2 patients (a 3-year-old girl and a young man) with CF (US) | QWB | QWB scores (child): prior to transplantation: 0.543; after transplantation: 0.899. QWB scores (young man): prior to transplantation: 0.6; after transplantation: 0.9) | None | ||

| Petrou (2009) [125] | Use of data from the Disability Survey 2000 to augment previous catalogues of preference-based HRQoL weights by estimating preference-based HUI3 multi-attribute utility scores associated with a wide range of childhood conditions | 2236 children with chronic conditions, including 30 with CF (England and Scotland) | HUI3 (caregiver proxy-reported) | Mean HUI3 utility score: 0.384 (± 0.336). In CF subgroup the mean score is 0.728. The mean HUI3 utility score for children of the same age is 0.929 (± 0.129) | The principal caregiver was considered the appropriate subject for the task as pilot research had indicated that the comprehension level for the HUI was somewhat high for our paediatric sample where a number of children have developmental disabilities | ||

| Ramsey (1995) [129] | Cost-effectiveness analysis of lung transplantation | 52 patients (24 on the waiting list and 28 posttransplant), of which 7 with CF (US) | Standard gamble | Mean (± SD) utility: waiting list: 0.65 ± 0.26; posttransplant (≤ 4 months): 0.73 ± 0.24; posttransplant (> 4 months): 0.89 ± 0.15 | None | ||

| Santana (2012) [133] | Cross-sectional data (at 2 years of lung transplantation) of a prospective study to assess whether HRQoL differs among diagnosis groups | 214 lung transplant recipients (of which 39 with CF) at 2 years of lung transplantation (Canada) | HUI3 | CF group: mean (SD) HUI overall score (at 2 years post transplantation): 0.74 (0.19) | None | ||

| Selvadurai (2002) [134] | Randomized study to compare groups performing aerobic and resistance training with a control group in terms of fat-free mass, pulmonary function (FEV1, FVC), lower limb strength and QoL | 66 children with CF (8–16 years) admitted to hospital with an infectious PE (Australia) | QWB | Baseline QWB score [mean (SD)]: aerobic training: 0.62 (0.28); resistance training: 0.60 (0.26); controls: 0.62 (0.29). Aerobic training produced significant improvements in QWB (+ 14.28%) | None | ||

| Singer (2015) [137] | Prospective cohort study to investigate HRQoL in lung transplant recipients | 387 transplanted patients (of which 83 with CF) in Canada | EQ-5D, standard gamble, VAS | Transplantation conferred large improvements in all HRQL measures [units (95% CI)]: EQ-5D of 0.27 (0.24–0.30), SG of 0.48 (0.44–0.51), and VAS of 44 (42–47) | None | ||

| Singer (2017) [136] | Prospective cohort study to study the effect of lung transplantation on HRQoL | 211 transplanted patients of which 19 with CF (US) | EQ-5D-3L | CF group (baseline): EQ-5D: 0.60 (0.44–0.78); EQ-VAS: 29 (20–30); CF group (change after lung transplantation): EQ-5D: 0.30 (0.22–0.39); EQ-VAS: 43.0 (36.8–49.3) | None | ||

| Solem (2016) [139] | Use of data from a 48-week randomized, placebo-controlled study of ivacaftor to examine the impact of PEs and lung function on generic measures of HRQoL | 161 patients ≥ 12 years with CF and a G551D-CFTR mutation (US) | EQ-5D-3L (UK value set) | EQ-5D index (mean, [SE]): no lung dysfunction: 0.931 (0.023); mild: 0.923 (0.021); moderate: 0.904 (0.018); severe: 0.870 (0.020). VAS score: no lung dysfunction: 85.2 (2.0); mild: 82.3 (1.8); moderate: 76.8 (1.6); severe: 73.3 (1.8) | In our analyses, ceiling effects were high, particularly for the EQ-5D index and in patients with no lung dysfunction or mild lung dysfunction as well as among those with less severe disease (i.e., patients who did not experience PEs). It should be noted that the EQ-5D index at the time of study initiation was high (mean ≈ 0.93) leaving little room for improvement with study treatments. While both EQ-5D and VAS are generic measures, they provide complementary information; the use of the EQ-5D index alone (a generic HQRL measure) may limit characterization of disease burden and health gains in patients with CF. The EQ-VAS measure showed greater ability to discriminate disease severity than the EQ-5D index. Some dimensions of the EQ-5D, particularly self-care, are less likely to be impacted by CF. Moreover, the EQ-5D was designed for use in populations 18 years of age or older, whereas this study included adolescent patients as young as 12 years of age. | ||

| Suri (2001) [141] | Open cross-over 12-week trial to compare hypertonic saline and alternate-day or daily recombinant human deoxyribonuclease in terms of FEV1, FVC, number of PEs, weight gain, QoL, exercise tolerance and costs | 47 children with CF aged between 5 and 18 (UK) | QWB | Mean QWB at baseline (SD; range): 0.61 (0.12; 0.35–0.84) | None | ||

| Vasiliadis (2005) [148] | Cost–utility analysis of lung transplantation (including a cross-sectional study to estimate utilities) | 105 patients (34 candidates and 71 recipients) in Canada | Standard gamble | Mean (± SD) difference between post-transplant recipient reported utility and candidate reported utility (CF and bronchiectasis subgroup): waiting list: 0.11 ± 0.09 (n = 8); after transplantation, first year: 0.72 ± 0.11 (n = 10); second year: 0.82 ± 0.12 (n = 8); third year: 0.84 ± 0.19 (n = 2); fourth year: 0.87 ± 0.16 (n = 3); > fifth year: 0.61 ± 0.12 (n = 7) | The SG assumes that subjects are neutral toward probability risks. In this study, candidates may have been more ready to accept a risk, thus underestimating the utility associated while waiting. | ||

| Whiting (2014) [150] | Cost-effectiveness analysis of ivacaftor for the treatment of CF | Patients aged ≥ 6 years who have at least one G551D mutation in the CFTR gene (UK) | EQ-5D (US and European value sets) | Utility values by percentage predicted FEV1: normal (FEV1 ≥ 90%): 0.97; mild (FEV1 70–89%): 0.95; moderate (FEV1 40–69%): 0.93; severe (FEV1: < 40%): 0.91 | None | ||

| Yi (2003) [153] | Cross-sectional study to assess health values in adolescents with CF | 65 adolescents (12–18 years) with CF (US) | HUI2, VAS, standard gamble, and time trade-off (VAS results were normalized to a 0.0–1.0 scale) | The mean (± SD) TTO utility was 0.96 (± 0.07) and the mean (± SD) SG utility was 0.92 (± 0.15). The mean (± SD) global utility estimate derived from the HUI2 was 0.83 (± 0.16). The mean (± SD) VAS was 0.76 (± 0.2). | The HUI2 did not appear to discriminate well between levels of health. The mean HUI2 global utility estimate was significantly lower than both the TTO and SG scores and did not correlate with either score. Nevertheless, because the issue of fertility is important in CF, an advantage of the HUI2 is that is addresses fertility. The utilities derived by the TTO and SG methods correlated well with each other and mean values were similar. | ||

|

HST2 (16/12/2015) Elosulfase alfa/Mucopolysaccharidosis type IVa |

Hendriksz (2014) [86] | Cross-sectional survey to assess the global burden of disease among patients with Morquio A, including the impact on mobility/wheelchair use, HRQoL, pain and fatigue and the interaction between these factors | 27 adults (≥ 18) and 36 children (7–17 years) from Brazil, Colombia, Germany, Spain, Turkey, and UK | EQ-5D-5L | The HRQoL utility values were 0.846, 0.582 and 0.057 respectively in adults not using a wheelchair, using a wheelchair only when needed and always using a wheelchair; values were 0.534, 0.664 and –0.180 respectively in children. In both adult patients and children, the HRQoL was most negatively affected in the domains mobility, self-care, and usual activities. | In the adult patient group, the EQ-5D pain/discomfort domain scores did not follow the pain severity scores obtained by the BPI-SF for the different mobility categories. Most likely, this is due to the fact that the pain/discomfort score of the EQ-5D-5L is based on a single question whereas the BPI-SF comprises different questions to assess pain severity and will be able to capture more subtle differences between patients. | |

|

HST2 (16/12/2015) Elosulfase alfa/Mucopolysaccharidosis type IVa |

Hisashige (2011) [87] | Cross-sectional survey to estimate preference-based HRQoL (i.e., utility) in patients with MPS using proxy respondents | 93 medical students and 6 medical experts (Japan) | Direct measurement (i.e., VAS, standard gamble, and time trade-off) | MPS IV (Morquio syndrome), mean (SD): medical students: VAS: 0.22 (0.22); TTO: 0.47 (0.22); SG: 0.54 (0.27); medical experts: VAS: 0.39 (0.21); TTO: 0.52 (0.28); SG: 0.62 (0.28); | In this study, the patients of MPSs were not used as the respondents, since they are often children with mental retardation, who would have difficulty in evaluating utility of their own health states. Health professionals are used as surrogate respondents for the patients. Utility values among medical experts were quite similar to those among medical students. However, the sample size of medical experts was very small. Any surveys using parent proxies and/or a sample of the general population are encouraged. Indirect approaches (e.g., EQ-5D) would be more practical with larger samples but their validity needs to be examined in comparison with direct measurement results. | |

| Péntek (2016) [124] | Multi-country, cross-sectional survey to assess the HRQoL of patients with MPS and their caregivers | 120 patients and 66 caregivers (seven European countries) | EQ-5D-3L collected from patients and caregivers (country-specific societal value sets) |

Patients’ average (SD) EQ-5D and VAS scores varied across countries from 0.13 (0.43) and 0.43 (0.30), and from 30.0 (28.3) and 62.2 (18.3), respectively Caregivers’ average (SD) EQ-5D and VAS scores varied from 0.39 (NA) and 0.94 (0.11), and from 45.0 (NA) and 84.4 (12.1), respectively |

None | ||

|

HST2 (16/12/2015) Elosulfase alfa/Mucopolysaccharidosis type IVa |

Pintos-Morell (2018) [126] | Prospective real-world study to evaluate the effectiveness of ERT with elosulfase alpha in terms of 6-MWT, 3-MSCT, urinary glycosaminoglycans and HRQoL | 7 patients with MPS-IVA (Spain) | EQ-5D-5L | EQ-VAS (range): baseline: 25–60; 8 months: 45–75 | We use the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, as recommended by the international guidelines for the management and treatment of MPS IVA | |

| HST8 (10/10/2018) Burosumab/X-linked hypophosphatemia | Forestier-Zhang (2016) [80] | Use of cross-sectional data from a prospective cohort study to describe HRQoL and conduct a cost-utility analysis of a hypothetical treatment for a rare bone disease | 24 patients (UK) | EQ-5D-5L (English value set) | The mean health utility score was 0.648 (± 0.290) and mean VAS was 60.8 (± 26.9) | The EQ-5D-5 L is a generic HRQoL measure and may not capture specific problems for this patient group; also, the utility score is derived from the preferences of the general population and the preferences for patients with rare bone diseases may differ | |

| HST7 (7/2/2018) Strimvelis/Adenosine deaminase deficiency- severe combined immunodeficiency | Van der Ploeg (2019) [146] | Cost-effectiveness analysis of new-born screening for severe combined immunodeficiency | None | Author’s estimates based on published literature and in consultation with clinical experts | Utility: good: 0.95; moderate: 0.75; poor: 0.5 | None | |

| TA588 (24/7/2019) Nusinersen/Spinal muscular atrophy | Belter (2020) [56] | Cross-sectional survey to collect baseline QoL results among individuals affected by SMA | 478 individuals and/or caregivers of individuals affected by SMA (worldwide) | HUI3 completed by parents of affected children aged 5 and up and by affected adults aged 18 and up (children did not complete the HUI) | Overall, the average HUI3 scores ranged from –0.05 to 0.64 | The HUI3 measures someone’s ability to perform daily activities, such as dressing, which is a common activity that patients with SMA would like to improve or maintain. However, not all the attributes assessed by the HUI3 may be relevant for any of the SMA population. For example, the HUI3 assesses QoL through vision and hearing attributes, which are not relevant to the manifestation of SMA across types, and the high attribute scores as shown in this analysis, demonstrate this. | |

| Chambers (2020) [64] | Cross-sectional cohort study to quantify the economic and HRQoL burden incurred by households with a child affected by SMA | 40 children (and their parents) with SMA I, II and III (Australia) | EQ-5D-Y completed by patients or caregivers on behalf of their child if aged below 8 (EQ-5D-3L Australian valuation weights used as proxy). CarerQoL-7D (Australian valuation weights) completed by caregivers (for themselves) | Average caregiver and patient utility scores were 0.708 and 0.115, respectively. Average caregiver and patient VAS scores were 6.14 (0–10) and 66 (0–100) | None | ||

| TA588 (24/7/2019) Nusinersen/Spinal muscular atrophy | Lloyd (2019) [106] | Cross-sectional study to estimate QoL weights or utilities of different SMA states | 5 clinical experts (UK) | (1) Development of SMA case histories describing Type I (infantile onset) and Type II (later onset) patients and different outcomes from treatment. (2) Valuation of case studies using EQ-5D-Y proxy reported (EQ-5D-3L UK weights used as proxy) | The SMA Type I utilities ranged from −0.33 (requires ventilation) to 0.71 (Type I patient reclassified as Type III following treatment). The SMA Type II utilities ranged from − 0.13 (worsened) to 0.72 (stands/walks unaided) | The study presents some limitations. First, the accuracy of the HRQoL results was dependent on the validity or accuracy of the case study descriptions, and the ability of the experts to provide an accurate proxy assessment of HRQoL. Second, the manifestation of SMA is heterogeneous but the descriptions of SMA states are by necessity a simplification and do not reflect this variability. Third, it was only possible to recruit a small group of expert physicians. However, while the group was small, their ratings were quite consistent; physicians are also able to draw on their experience of treating numerous patients with SMA, as opposed to a parent’s experience of caring for just their child; therefore, using physicians for proxy reporting allow to avoid some bias that parental judgment of HRQoL may introduce. Finally, the assessment of HRQoL used the EQ-5D-Y, which has not been proven as valid in children as young as some patients with SMA (e.g., infantile-onset patient population). However, no other alternatives currently exist for the assessment of HRQoL in such young children or infants. Despite these limitations, the study has produced data with face validity. | |

| TA588 (24/7/2019) Nusinersen/Spinal muscular atrophy | López-Bastida (2017) [110] | Cross-sectional and retrospective study to determine the economic burden and HRQoL of patients with SMA and their caregivers in Spain | 81 caregivers of patients (1–17 years) with SMA (Spain) | EQ-5D completed by caregivers (3L proxy version for patients, 5L for caregivers) | Mean EQ-5D score: 0.16 (patients) and 0.49 (caregivers). Mean EQ-VAS: 54 (patients) and 69 (caregivers) | None | |

| Zuluaga-Sanchez (2019) [156] | Cost effectiveness of nusinersen for the treatment of patients with infantile-onset (ENDEAR phase III trial) and later-onset SMA (CHERISH phase III trial) | Patients and caregivers (Sweden) | The ENDEAR and CHERISH trials did not collect utility values from patients or caregivers. Patient’s utilities were derived from Lloyd. To estimate the caregiver utilities, a fixed caregiver utility value was anchored to the stabilisation of the baseline function health state (infantile-onset: 0.850; later onset: 0.815; assumption). Then, the difference in magnitude between the patient utility of the stabilisation of the baseline function health state (−0.120 in the infantile-onset and 0.04 in the later-onset) and the other health states (e.g., the utility assigned to patients in the worsened health state in the infantile-onset model was −0.240; the difference to the stabilisation of baseline function health states was 0.12) was applied to derive the caregiver utilities for each health state. The disutility was the difference between the caregivers utility and the general population utility. | Health-state caregiver disutility values: worsened: –0.160; stabilization of baseline function: – 0.040; mild improvement: –0.090; loss of later-onset SMA advanced motor function: –0.160 | As the CHERISH study collected the PedsQL and a mapping algorithm for PedsQL to EQ-5D was available (Khan 2014), EQ-5D utility values were estimated for the later-onset model health states with the limitation that the patients in the CHERISH trial were substantially younger than the patients used to develop the algorithm. However, these utility values were not explored in the scenario analysis, as they lacked face validity (the utility estimated for the worst health state was 0.73, while the valuation elicited from clinicians in the study by Lloyd et al. for the same health state was − 0.13). | ||

| TA431 (25/1/2017) Mepolizumab/Severe refractory eosinophilic asthma | Lloyd (2007) [108] | Prospective study to report the impact of exacerbations on HRQoL and health utility in patients with moderate to severe asthma | 112 patients (UK) | EQ-5D; ASUI | Mean (SD): ASUI: no exacerbation: 0.75 (0.20); exacerbation: 0.48 (0.27); hospitalized: 0.31 (0.22); EQ-5D utility: no exacerbation: 0.89 (0.15); exacerbation: 0.57 (0.36); hospitalized: 0.33 (0.39); EQ-VAS: no exacerbation: 76.1 (15.51); exacerbation: 56.43 (21.58); hospitalized: 49.0 (19.49) | There was some evidence of floor effect on ASUI in its ability to capture the impact of exacerbations | |