Abstract

Background

Veterans receiving care within the Veterans Health Administration (VA) are a unique population with distinctive cultural traits and healthcare needs compared to the civilian population. Modifications to evidence-based interventions (EBIs) developed outside of the VA may be useful to adapt care to the VA healthcare system context or to specific cultural norms among veterans. We sought to understand how EBIs have been modified for veterans and whether adaptations were feasible and acceptable to veteran populations.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of EBI adaptations occurring within the VA at any time prior to June 2021. Eligible articles were those where study populations included veterans in VA care, EBIs were clearly defined, and there was a comprehensive description of the EBI adaptation from its original context. Data was summarized by the components of the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based interventions (FRAME).

Findings

We retrieved 922 abstracts based on our search terms. Following review of titles and abstracts, 49 articles remained for full-text review; eleven of these articles (22%) met all inclusion criteria. EBIs were adapted for mental health (n = 4), access to care and/or care delivery (n = 3), diabetes prevention (n = 2), substance use (n = 2), weight management (n = 1), care specific to cancer survivors (n = 1), and/or to reduce criminal recidivism among veterans (n = 1). All articles used qualitative feedback (e.g., interviews or focus groups) with participants to inform adaptations. The majority of studies (55%) were modified in the pre-implementation, planning, or pilot phases, and all were planned proactive adaptations to EBIs.

Implications for D&I Research

The reviewed articles used a variety of methods and frameworks to guide EBI adaptations for veterans receiving VA care. There is an opportunity to continue to expand the use of EBI adaptations to meet the specific needs of veteran populations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-023-08218-z.

KEY WORDS: veterans, veterans administration, adaptations, intervention.

BACKGROUND

Evidence-based interventions (EBIs) are often implemented in settings different from those in which they were originally developed and are frequently adapted to better meet the needs of the novel setting and/or population. Adaptations have been defined as modifying programs or practices, usually in a planned or thoughtful way.1–5 Such modifications are typically intended to improve the feasibility, compatibility, acceptability, and/or effectiveness of an EBI for use in specific contexts (e.g., community, political, religious),6 to better reflect cultural or societal norms,7 to provide refinements for a different population than originally intended, or to meet the requirements of system-level constraints2. Adaptations may be developed during study design, prior to study start, or may occur during the intervention based on feedback or need,2 and, when successful, can lead to improved reach, acceptability, and sustainability of the EBI.

The importance of adapting EBIs to specific populations—such as veterans—has been well-documented.1,8 According to Rogers9, adaptations are needed as “innovation almost never fits perfectly in the organization in which it is being embedded” and having “organizations and stakeholders involved in the implementation process” can help “optimize fit and maximize effectiveness” of an EBI.10 As the use of adaptations of EBIs becomes more popular within the field of implementation science,1 a growing body of literature has suggested that developing strategies to document such adaptations is needed. Specifically, Chambers and Norton11 argue for an “adaptome” that systematically documents variations and adaptations for intervention developers and the implementation science research community. Similarly, the expanded Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based interventions (FRAME) offers a framework for characterizing and coding adaptations to EBIs.2 The use of FRAME can facilitate a structured approach to document the implementation of EBIs, with details on when and why modifications were made to the original intervention, as well as reasons for the modifications.

Adaptations to EBIs implemented for US veterans may be especially warranted. Over 9 million veterans receive care within the Veterans Health Administration (VA), the largest integrated healthcare system in the USA.12 Veterans are a unique population with geographic distribution throughout the country. Nearly 1/3 of veterans are members of a racial or ethnic minority group, with women veterans representing the most diverse group of veterans.13 EBIs may be useful for the veteran population given their distinctive cultural traits, such as core military values (e.g., loyalty, duty, integrity) and experiences of military culture including language (e.g., military lingo), uniforms, specific sets of rules and regulations, and hierarchical structure (e.g., rank, chain of command, specialty).14–16 Furthermore, veterans have higher rates of mental health disorders, substance-use disorders, suicide, homelessness, and other chronic physical health conditions compared to civilians.17 Modifications to EBIs developed outside of the VA, or for particular subgroups of veterans, may be useful to adapt care to match the VA healthcare system context, to specific veteran cultural norms, or to account for high rates of comorbidity within the VA setting.

Given that veterans are a unique population with distinctive cultural traits, have higher rates of mental and physical health conditions compared to civilians, and receive healthcare within a veteran-specific context, adaptations to EBIs developed outside of the VA healthcare system or for different subsamples of the veteran population (e.g., women veterans) may facilitate better outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, no previous review has documented studies with adaptations to EBIs for the VA setting or for specific subgroups of veterans. Therefore, the objective of this scoping review was to document adaptations to EBIs occurring within the VA, to examine how adaptations were done within the VA context, and to explore whether EBI adaptations were feasible to implement and/or acceptable to veterans.

METHODS

We conducted a scoping review of EBI adaptations occurring within the VA at any point prior to June 2021. As our goal was to examine key concepts in this research area, we opted for a scoping review to conduct a broad overview and capture data on studies that used different research designs, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures.18,19

Search Strategy

We conducted our initial search in PubMed/MEDLINE where we extracted the full search terms (including MeSH terms) and conducted subsequent searches using the full search terms in CINAHL and PsycInfo (see Appendix for search terms). Search terms included (but were not limited to) adaptation, tailored, intervention, evidence-based, and Veterans Health Administration.

Data Abstraction

Criteria for sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, and research type (SPIDER) were developed to guide our inclusion and exclusion criteria.20 SPIDER is often used in evaluating both quantitative and qualitative research and thus we chose to use this model to develop our eligibility criteria.21 The SPIDER criteria identified articles with (1) study populations including veterans in VA care (sample); (2) clearly defined EBIs (phenomenon of interest); (3) comprehensive descriptions of EBI adaptation from their original context (design); (4) specific adaptation frameworks or methods identified (evaluation); and (5) quantitative or qualitative methods used (research type). These criteria helped us identify papers where care specific to veterans was being adapted, there was a clear description of the EBI being implemented, and specifics on the adaptation process were included.

Data were abstracted by one reviewer (AKD). Initially, study titles and abstracts with our key terms were evaluated for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Study titles and abstracts that met all SPIDER criteria were selected for full-text review. For samples that also included VA providers and/or staff, we retained the article as long as veteran outcomes were described or veterans were part of the feedback process for articles with qualitative findings. Searches were limited to the English language; articles were additionally excluded if they consisted of non-original research (e.g., review article, meta-analysis, opinion, letter, case report, case series, or commentary) or research that was not peer-reviewed.

Published protocols for studies and completed studies were included. For papers where we retrieved both a protocol and completed study, only the paper on the completed study was retained. Data was extracted by SPIDER criteria into a REDCap database.22 Following abstraction, we charted and summarized our results.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Data was summarized by the veteran population studied, the modification content area (e.g., mental health, diabetes), outcomes measured, and key findings. We include brief details on demographics for the samples in each article if they were provided. We synthesized our data based on process-specific components from the expanded Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications (FRAME)2 and using the FRAME Excel Tracking Spreadsheet (available at https://med.stanford.edu/fastlab/research/adaptation.html) to chart our results. As we were specifically interested in what and when EBIs were adapted as well as who was involved in the study, these were the FRAME elements we focused on for this analysis. We used elements of FRAME including when the modification occurred (e.g., pre-implementation, implementation, scale-up), whether the adaptations were planned, who participated in the decision to modify, and what was modified (e.g., content, trainings, implementation activities).

FINDINGS

Description of Studies

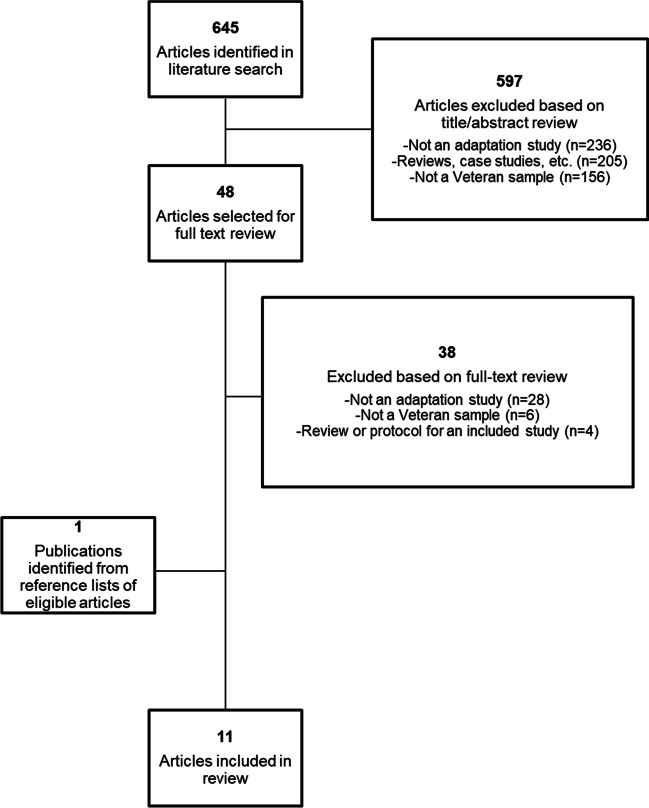

Figure 1 describes our article identification process. We retrieved 922 abstracts based on our search terms. After removing duplicates (n = 277), we were left with 645 titles and abstracts for review. Following the review of these 645 titles and abstracts, we excluded 236 of the 645 (37%) articles as they did not describe an adaptation, 205 of the 645 (32%) studies as they were reviews or case studies, and 156 of the 645 articles (24%) that did not include a veteran sample. This left 48 of the 645 (7%) articles for full-text review. Ten articles (21% out of the 48 eligible) met the SPIDER criteria. Most excluded articles (n = 28/38; 74%) did not include a comprehensive description of how the EBI was adapted from its original context. Other reasons for exclusion included the sample was not comprised of veterans or there were no veteran outcomes reported (n = 6/38, 16%) or the article was a review study or protocol for a completed study that was included (n = 4/38, 11%). A review of reference lists of eligible articles resulted in the identification of one additional article, resulting in a total of 11 articles included in this review. Ten of the included articles described results from complete studies23–32; one article33 was a protocol describing a study that was ongoing at the time of article retrieval.

Figure 1.

Article identification, exclusion, and final sample.

Description of Adaptations

Included articles described adaptation of EBIs for mental health (n = 4),23,30,32,33 access to care and/or care delivery (n = 3),26,29,30 diabetes prevention (n = 2),24,27 substance use (n = 2),25,31 weight management (n = 1),32 care specific to cancer survivors (n = 1),28 and/or to reduce criminal recidivism among veterans (n = 1)33. All papers used some form of qualitative feedback to inform adaptations. Qualitative interviews took place with veterans in eight papers (73%)23,25–29,32,33 and providers and/or VA leadership (e.g., clinical practice leadership, facility administrators, VISN directors) in five papers (45%).23–25,29,30 Six articles (55%) provided information on participant demographics.24,25,27,28,31,32 Two articles included samples of all27 or predominantly female veterans24; five of the six articles included samples with over 50% White veterans (Table 1).24,25,28,31,32

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Articles Included in the Review (n = 11)

| Author, year | Study location(s) | Study population, sample size, & demographics | Aims & purpose | Article topic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | Care delivery/access | Diabetes | Substance use | Weight Management | Care for cancer survivors | Criminal recidivism | ||||

| Abraham, 2018 |

Veteran participants: one CBOC in Arkansas Providers: CBOCs in Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, & Mississippi |

N = 11: veterans N = 11: CBOC mental health providers N = 6: VA expert CBT clinicians N = 5: VA Central Office leaders *No demographics provided |

Adapt the original National Institute of Mental Health–funded Coordinated Anxiety Learning Management (CALM) program for use in rural VA outpatient settings to support VA CBOC mental health providers in delivering CBT to veterans with a recent mental health care visit at a VA CBOC & with a diagnosis of anxiety, PTSD, or depression | x | ||||||

| Arney, 2018 | Five hospitals or CBOCs within one VISN | N = 35: providers & leadership (80% female; 83% White) | Inform the implementation of an evidence-based, diabetes group intervention (Empowering Patients in Chronic Care, EPIC) into routine primary care & develop operational partnerships that promote dissemination & institutionalization of the intervention | x | ||||||

| Blonigen, 2018 | (1) Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System; (2) VA Palo Alto Health Care System; & (3) Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital | N = 365: targeted veteran enrollment (122 veterans from each site) | Evaluate the effectiveness & implementation potential of Moral Reconation Therapy for veterans with history of incarceration enrolled in mental health residential treatment programs at the VA | x | x | |||||

| Blonigen, 2020 | VA Palo Alto Health Care System |

N = 12: veterans (92% male; 58% White) N = 11: peer providers employed by the VA (82% male; 64% White) |

Repurpose the Step Away mobile intervention system for veterans with a positive screen for hazardous drinking during a primary care visit | x | ||||||

| Day, 2021 | Veterans Affairs Medical Center-Fort Harrison | Not specified | Develop the Personalized Implementation of Video Telehealth for Rural Veterans (PIVOT-R) approach for rural veterans | x | ||||||

| Dyer, 2020 |

VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System |

N = 119: veterans (100% female; 45% Black) | Assess the impact of gender-tailoring & modality choice on women veterans’ perceptions of & engagement in tailored Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) | x | ||||||

| Hoerster, 2020 | VA Puget Sound Health Care System | N = 44: veterans (71% male; 50.4% White) | Develop, pilot, & refine a tailored behavioral weight management program for overweight veterans with PTSD (MOVE! + UP) | x | x | |||||

| King, 2014 | VA Boston Healthcare System | N = 15: veterans (87% male; 87% White) | Describe the reach, application, & effectiveness of a cancer survivor yoga protocol with a pilot sample of older veterans | x | ||||||

| Leonard, 2019 | Five VA facilities (no further specification provided) |

N = 7: veterans N = 41: providers *No demographics provided |

Describe how the Practical Robust Implementation & Sustainability Model (PRISM) was operationalized to guide the assessment of local context prior to implementation of the rural Transitions Nurse Program (TNP) | x | ||||||

| Rubenstein, 2010 | Seven sites within the following VA network regions: (1) VA Midwest Health Care Network (VISN 23); (2) VA Healthcare System of Ohio (VISN 10); & (3) South-Central VA Health Care Network (VISN 16) |

N = 208: veterans N = 36: providers & leadership (12 from each region) *No demographics provided |

Adapt research-based collaborative care for depression to VA contexts | x | x | |||||

| Yano, 2008 | 18 VA facilities across five southwestern states, matched on size & academic affiliation | N = 1941: veterans (94% male; 64% White) | Evaluate the effectiveness of an EBQI method for enabling healthcare managers, rather than researchers, to implement evidence-based smoking cessation interventions for veterans in the context of local practice needs & under routine conditions & to determine its impact on practice-level smoking cessation | x | ||||||

CBOC community-based outpatient clinics, CBT cognitive behavioral therapy, EBQI evidence-based quality improvement, PTSD posttraumatic stress disorder, VISN Veterans Integrated Services Network

A description of the adaptations made to each EBI, and the potential impacts of these adaptations to the original EBI, is included in Table 2. Additionally, Table 2 shows that four (36%) of the included articles adapted EBIs for veterans or VA providers that were developed externally from the VA.23,25,28,33 Four other papers (36%) adapted EBIs already in use at the VA but tailored those interventions for specific veteran populations, including rural veterans,26,29 women veterans,27 or veterans with PTSD.32 Three (27%) articles described the use of evidence-based quality improvement (EBQI) methods to test the delivery of an intervention by clinical staff instead of researchers.24,30,31

Table 2.

Original Intervention Description, Adaptation Goals, Frameworks, and Details of Adaptations in Included Studies (n = 11)

| Author, year | Original intervention description | Adaptation goal(s) | Adaptation framework/methods | Description of adaptation(s) made to original EBI | Potential impact(s) on original intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham, 2018 | CALM facilitates the delivery of CBT by mental health providers in outpatient settings, using a cognitive behavioral framework including psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, goal setting, exposure, & response prevention. The patient & provider both look at the computer screen together & proceed through the modules at an individualized pace | Adapt original CALM program for use in rural outpatient VA settings | ADDIE model | (1) General images were placed with images of veterans. (2) A new template with the VA logo was developed. (3) Videos of veterans describing their treatment and illness experiences were embedded. (4) Case studies were modified to better reflect experiences common to rural veterans. (5) Veterans were given the option of orally recounting (as opposed to only writing) their trauma experiences | These modifications likely had no impact on the integrity of the original program, better reflect the demographic characteristics and of rural veterans, and offer patient-centered health care consisting of treatment options that can be tailored to each individual veteran’s needs |

| Arney, 2018 | Empowering Patients in Chronic Care (EPIC) is a group-based intervention to aid patients in setting personalized goals for diabetes control, delivered by research staff & designed to occur over four sessions among a group of 5–7 participants | Assess the effectiveness of EPIC after implementation into routine care in five primary care sites | PARIHS | (1) The amount of information presented in each session was decreased. (2) The number of sessions was increased. (3) Patient reading materials were simplified | Training was incentivized with Continuing Education Units to encourage fidelity to the intervention. The training protocol was tailored to address common concerns and improve staff engagement. Strategic multilevel partnerships were developed to ensure the mobilization of necessary resources and broad support for the intervention |

| Blonigen, 2018 | Moral Reconation Therapy (MRT) is a cognitive behavioral intervention that aims to reduce criminogenic thinking & criminal recidivism | Assess use of MRT in a non-correctional setting and within a mental health treatment program | RE-AIM | N/A (protocol paper, potential adaptations to be studied) | |

| Blonigen, 2020 | Step Away is a mobile-based intervention program for individuals who want to reduce or abstain from drinking but are unable or unwilling to receive in-person care | Repurpose the Step Away intervention for general populations to create a version that maximizes engagement and effectiveness with veterans | M-PACE model | (1) App text shortened to break up long paragraphs and enumerate key information. (2) App icon replaced with an image of an American flag. (3) Videos of veterans describing their recovery from drinking problems were embedded. (4) The app name was rebranded | These changes are unlikely to have an adverse impact on the effectiveness of the Step Away program and may have the benefit of increasing the extent to which veterans identify with the app |

| Day, 2021 | PIVOT is a flexible video telehealth-to-home (VTH) implementation strategy that is adaptive to site-specific contexts & different digital innovations | Use PIVOT to improve VTH adoption in rural settings | Formative evaluation | (1) Rurality as a cultural factor was addressed to account for components of rurality (i.e., rural identity, traditions, and perceptions of help seeking or care). (2) Considerations were made for sites with a smaller or less specialized workforce. (3) Considerations were made for providers who may be accustomed to operating independently, have minimal time or motivation to enact practice changes, and have important perspectives on how to address unique barriers to implementation faced by rural sites. (4) Internal facilitators were identified to act as points of contact to improve understanding of the specific site context, demonstrate commitment to the site’s priorities, and increase engagement by fostering trust and credibility | The inclusion of a comprehensive assessment of the rural site, including infrastructure and resources, greatly improves understanding of a site’s specific needs and enables a tailored approach that targets relevant barriers |

| Dyer, 2020 | The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) is an intensive lifestyle intervention to lower the risk of incident diabetes | Assess the impact of gender-tailoring and modality choice (online vs. in-person) on women veterans’ perceptions of and engagement in tailored DPP | Formative evaluation | (1) Included gender-specific groups. (2) Allowed participants to choose from online or in-person modalities | Tailored DPP effectively addressed known barriers to intervention engagement in women veterans with prediabetes, such as potential discomfort in mixed-gender groups, transportation difficulties, rural residence, schedule conflicts, and limited computer literacy or access |

| Hoerster, 2020 | MOVE! Is a behavioral weight management program that uses techniques like goal setting, self-monitoring, & motivational interviewing through in-person group sessions | Develop, pilot, and refine a tailored behavioral weight management program for veterans with PTSD | VA Peer Support Implementation Toolkit | (1) Adapted standard MOVE! materials to allow for PTSD-specific content. (2) In-person sessions included walking outdoors adjacent to the VA facility, to provide exercise, to address hypervigilance-based activity barriers, and to encourage participants to walk in their own communities outside of MOVE! + UP sessions | Refining MOVE! UP appears to have yielded a more valuable, acceptable, and feasible program and study procedures |

| King, 2014 | A yoga intervention with positive findings for women at middle age | Adapt for an older and predominantly male veteran population | RE-AIM | (1) Modifications were made to physical yoga poses as most participants required modification of at least one or more poses. (2) Modifications were made to the instruction, adapting teaching in response to participants appearing “confused, tearful, distracted, or fidgety”. (3) Material was covered more slowly and at a more basic level | There was a broad range in participants’ functioning and required adaptations. Resulting in the development of a unique protocol for each veteran participant, rather than for all veteran participants in the class. This raises concerns about how to most effectively conduct group research on this population going forward |

| Leonard, 2019 | Transitions Nurse Program (TNP) is a multi-component, nurse-led intensive care coordination intervention designed to improve care transitions | Adapt for rural veterans who are hospitalized at VA hospitals & subsequently discharged to their rural residence & care setting | PRISM | (1) Created clear role descriptions and brainstormed ways to utilize existing infrastructure. (2) Modified program enrollment criteria at sites concerned with an overwhelming number of eligible patients. (3) Encouraged Transition Nurses to provide informational sessions at PACT sites to engage stakeholders and initiate relationships | Making these adaptations early in the implementation process helped to roll out the EBI more quickly at each site |

| Rubenstein, 2010 | Translating Initiatives in Depression into Effective Solutions (TIDES) implements research-based depression collaborative care in primary care practices | Adapt for VA primary care practices | EBQI | (1) Presented regional leaders, local leaders, and workgroups with scientific evidence and enabled them to pick the features they considered best suited to their contexts | TIDES developed an evidence-based depression collaborative care prototype with excellent overall patient outcomes |

| Yano, 2008 | US Public Health Service smoking cessation guidelines | Implement smoking cessation interventions in the context of local VA practice needs and to have the intervention delivered by healthcare managers rather than researchers | EBQI | (1) Researchers facilitated discussions with site leadership to promote ongoing local adaptations of the interventions | Facilities were encouraged to try new methods of encouraging smoking cessation among patients; however, this did not translate into improved quit rates among the veteran samples studied |

ADDIE Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, Evaluation model, CBT cognitive behavioral therapy, EBQI evidence-based quality initiative, M-PACE Method for Program Adaptation through Community Engagement, PARIHS Promoting Action on research in Health Services, PHQ Patient Health Questionnaire, PRISM Practical Robust Implementation & Sustainability Model, RE-AIM Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, & Maintenance

Frameworks used to guide the adaptation process included EBQI processes (n = 2),30,31 Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM; n = 2),28,33 and Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM; n = 1).29 Other frameworks included the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, Evaluation (ADDIE) model,23 Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS),24 and Method for Program Adaptation through Community Engagement (M-PACE).25 Two studies used formative evaluation to provide information about implementation.26,27 Finally, one study used the VA Peer Support Implementation Toolkit,32 VA-designed guidelines outlining how to train peer support specialists.34

Outcomes

Most articles reported outcomes that were qualitative in nature such as uptake,26 usability,25 reach,28 satisfaction,32 and barriers/facilitators of engagement with the adapted EBIs.23–25,27 Other key findings showed that modifications to existing EBIs better reflected specific experiences of veterans.23,25 Two studies with quantitative findings found that adaptations to EBIs resulted in meaningful weight loss32 and reduced depression symptoms as measured by PHQ-9 scores.30 Two articles reported null findings in their main outcomes,28,31 although both of these studies indicated positive findings on secondary outcomes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes Measured and Key Findings (n = 11)

| Author, year | Outcomes measured | Key findings |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham, 2018 | Acceptability and feasibility of the adapted program | Key stakeholders (including veterans, mental health providers, and VA Central Office leaders) suggested incorporating veteran-centric content. These modifications likely have no impact on the fidelity of the original CALM program and better reflect the demographic characteristics & experiences of rural veterans, enhancing the acceptability and feasibility among the targeted sample |

| Arney, 2018 | Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the intervention | Participants (including clinicians, leadership, and administrators) viewed group appointments as an effective approach to enhancing care. Clinicians discussed their roles in the groups & strategies to facilitate their performance in those roles |

| Blonigen, 2018 | Criminal recidivism | N/A (protocol paper) |

| Blonigen, 2020 | Engagement and effectiveness of the adapted program | Usability ratings of the individual modules and perceived utility of the app were uniformly positive across participants. Personalized feedback and addition of veteran-centric content were viewed as facilitators of engagement |

| Day, 2021 | Uptake of VTH for mental health care and satisfaction with the adapted program | PIVOT-R increased uptake by 10 times over a year of VTH for mental health care, with positive veteran feedback |

| Dyer, 2020 | Participant preferences with the adapted program | Participants preferred women-only groups for increased comfort, camaraderie, & understanding of gender-specific barriers to lifestyle change. More participants preferred (& participated in) online vs. in-person DPP |

| Hoerster, 2020 | Weight loss and acceptability of the adapted intervention | The final cohort reported high satisfaction & showed meaningful weight loss (Mean: -14 pounds [SD = 3.7] & 71% lost ≥ 5% baseline weight). Participant suggestions to encourage greater acceptability included additional sessions & professional involvement |

| King, 2014 | Reach and effectiveness |

Reach: 15% of eligible veterans enrolled, participated in classes, & practiced at home Effectiveness: participants reported a variety of qualitative benefits; however, comparisons of mean scores on standardized PTSD and quality of life measures showed no significant differences |

| Leonard, 2019 | Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the intervention | Themes that informed TNP implementation included a disconnect between primary care & hospital inpatient teams, concerns about work duplication, & concerns that one nurse could not meet the demand for the program |

| Rubenstein, 2010 | Changes in PHQ-9 scores | Mean PHQ-9 score improved by an average of nine points among all those who had an initial assessment & a final PHQ-9 (p < .0001) |

| Yano, 2008 | Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the intervention; cessation clinic attendance and smoking cessation rates | Intervention practices adopted multifaceted EBQI plans, but had difficulty implementing them, ultimately focusing on smoking cessation clinic referral strategies. Attendance rates increased (p < .0001), though there was no intervention effect on smoking cessation |

FRAME Components

There was a diverse range of modifications across our eleven articles based on the FRAME elements we examined. While the majority of studies (55%) were modified in the pre-implementation, planning, or pilot phases,23,25,28–30,33 there were examples of studies modified in the scale-up (27%)24,26,31 and maintenance and/or sustainment (18%)27,32 phases. All articles wrote about planned proactive adaptations to EBIs. Most adaptations (91%) involved the participation of the research team23–30,32,33, providers (73%)24–26,29–33, and/or veterans (73%)25–30,32,33 in the modification process. Three articles detailed leadership participation in the adaptation process.24,30,31 “Participation” included the involvement of stakeholders in providing feedback on the feasibility and acceptability of a given EBI and the use of formative and participatory research methods involving veterans who would directly benefit from a particular EBI. Modifications were most often contextual,23–30,32,33 with fewer studies detailing content,23,28,30–33 training and evaluation,24,30,31 or implementation activity modifications.24,26,27,31 Of the studies that made contextual modifications, these modifications were most often in the setting23–26,28–30 or population25,27–30,32,33, with fewer studies examining contextual modifications to the format27,32 or personnel24,30 involved in the intervention (Table 4).

Table 4.

FRAME Process Elements (n = 11)

| Element | N (%) |

|---|---|

| When did the modification occur? | |

| Pre-implementation/planning/pilot | 6 (55)23,25,28–30,33 |

| Implementation | 0 (0) |

| Scale-up | 3 (27)24,26,31 |

| Maintenance/sustainment | 2 (18)27,32 |

| Were adaptations planned? | |

| Planned/proactive adaption | 11 (100)23–33 |

| Planned/reactive adaption | 0 (0) |

| Unplanned/reactive modification | 0 (0) |

| Who participated in the adaptation process?* | |

| Research team | 10 (91)23–30,32,33 |

| Providers | 8 (73)24–26,29–33 |

| Veterans | 8 (73)25–30,32,33 |

| Leadership (facility and/or regional leaders) | 3 (27)24,30,31 |

| What was modified?* | |

| Content—modifications made to content itself | 6 (55)23,28,30–33 |

| Contextual—modifications made to the way the overall intervention is delivered | 10 (91)23–30,32,33 |

| Training and Evaluation—modifications made to staff training or how the intervention is evaluated | 3 (27)24,30,31 |

| Implementation and scale-up activities—Modifications made to implementation or scale-up strategies | 4 (36)24,26,27,31 |

| Where were contextual modifications made?* | |

| Format: changes were made to the format of the intervention delivery | 2 (18)27,32 |

| Setting: the intervention is being delivered in a different setting | 7 (64)23–26,28–30 |

| Personnel: the intervention is being delivered by different personnel | 2 (18)24,30 |

| Population: the intervention is being delivered to a different population than originally intended | 7 (64) 25,27–30,32,33 |

*Not a mutually exclusive category

DISCUSSION

Articles identified in this scoping review of adaptation for veterans receiving VA care used a variety of methods and frameworks to guide EBI adaptations. The majority of articles reported on modifications made to EBIs in the pilot phase, resulting in articles with smaller (pilot) sample sizes, and most reported qualitative findings such as feedback from veterans. Despite the small number of articles that shared quantitative findings, articles indicated veteran satisfaction, increased veteran focus, and clinically meaningful results with the given adaptations. For example, in Hoerster et al.’s 32 study, the MOVE + UP intervention for weight loss in veterans with PTSD found a meaningful loss of weight, high participant satisfaction, and PTSD symptom improvements in the cohort of veterans who completed the intervention. Not surprisingly, most modifications to contextual components of an EBI were made to the setting or population. This was evident in Dyer et al.’s 27 study where the Diabetes Prevention Program was tailored for gender (e.g., women veterans) and preferred modality of intervention delivery (e.g., online vs. in-person). This finding likely reflects the modification being conducted within the VA or with a greater emphasis on the unique characteristics of veterans. This is particularly illustrated by Blonigen et al. 25, where veterans provided feedback on the Step Away mobile app and in particular suggested that “modifying the appearance and design of the app to include more veteran-centric content” would benefit its use in a veteran population (e.g., adding links to veteran support groups and including veteran-specific statistics on problem drinking).

The papers reviewed here provide many examples of adaptations for veterans receiving care within the VA. All articles used some combination of common adaptation steps as identified in previous work,35 most often including consulting with stakeholders, adapting the original EBI, training staff, and testing the adapted materials. Most studies included here tested adapted EBIs in a relatively small pilot sample of veterans. This is likely due to the recent effort to adapt EBIs in a veteran population, highlighted by the majority (73%) of our included studies being published during or after 2018, and suggests that larger implementation studies may be forthcoming. However, the work presented here provides insight into achieving successful adaptation within the VA system.

While defining success in implementation work can be subjective,36 this scoping review provides examples of studies that describe implementation outcomes as outlined by Proctor et al.,37 such as acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, and feasibility, that are associated with improved outcomes, patient care, and user satisfaction. There is considerable opportunity to expand the use of EBI adaptations to meet the specific needs of veteran populations. Tailoring to subgroups that were not observed in our review (e.g., LGBTQ + , racial/ethnic minority subgroups) may be valuable, especially given the changing demographics of veterans and VA users. In the articles that provided sample demographics, most examined adaptations in White, male veterans. However, VA population projections show that both women and minority veterans are increasing,38,39 suggesting that there is a need to examine EBI modifications among growing veteran subgroups. Indeed, these findings demonstrate that future adaptation efforts could include greater input from samples of diverse veteran stakeholders.

We acknowledge that this review has limitations. First, while we conducted a broad review of available literature, consistent with rigorous scoping review methodology,18,19,40 there is always potential for missed articles. Second, scoping reviews by design do not examine the quality of the evidence examined. Third, we only included descriptions of adaptations as available in the included articles; it is likely that many other modifications are continuing to occur in routine clinical care that have not yet been systematically detected.41 Finally, we were unable to account for publication bias, and like any review, it remains unknown how much is published (or unpublished) about tailoring EBIs for veterans that does not result in the intended outcomes. Interestingly, all reviewed articles proactively planned their adaptations to EBIs. This is likely due to the nature of the modifications being made for a specific population (i.e., veterans).

In this first examination of adaptations to EBIs within the VA, we found several articles detailing methods and frameworks of such adaptations. Future steps include examining fidelity to the original interventions under study, which may first require a revised search to determine whether any of the EBIs that were studied in pre-implementation or pilot research have been implemented in larger-scale trials. Our results show that the VA is supportive of adaptations within the healthcare system, evidenced by the involvement of veterans, providers, and leadership across many of the reviewed articles. Continuing to expand the use of EBI adaptations to meet the specific needs of veteran populations may improve healthcare delivery and veteran satisfaction with that care.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. The authors would like to acknowledge support from the Institute for Implementation Science Scholars (IS-2), which is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) and Office of Disease Prevention, administered by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders, R25DK123008. Drs. Cabassa and Hamilton are mentors in the IS-2 program; Dr. Kroll-Desrosiers is a former scholar. Dr. Hamilton was supported by a VA Health Services Research & Development Research Career Scientist Award (RCS 21-135). Drs. Hamilton and Finley are additionally supported by EMPOWER QUERI 2.0 (QUE 20-028); Dr. Kroll-Desrosiers is a mentee in the EMPOWER QUERI 2.0 mentoring core.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Haardoerfer R, et al. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0815-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WiltseyStirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrera M, Jr, Berkel C, Castro FG. Directions for the Advancement of Culturally Adapted Preventive Interventions: Local Adaptations, Engagement, and Sustainability. Prev Sci. 2017;18(6):640–648. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0705-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabassa LJ, Druss B, Wang Y, Lewis-Fernandez R. Collaborative planning approach to inform the implementation of a healthcare manager intervention for Hispanics with serious mental illness: a study protocol. Implement Sci. 2011;6:80. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Intervention Mapping: Designing theory and evidencebased health promotion programs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrera M, Jr, Castro FG. A Heuristic Framework for the Cultural Adaptation of Interventions. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract. 2006;13(4):311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00043.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumpfer KL, Pinyuchon M, Teixeira de Melo A, Whiteside HO. Cultural adaptation process for international dissemination of the strengthening families program. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31(2):226–39. doi: 10.1177/0163278708315926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stirman SW, Gamarra J, Bartlett B, Calloway A, Gutner C. Empirical Examinations of Modifications and Adaptations to Evidence-Based Psychotherapies: Methodologies, Impact, and Future Directions. Clin Psychol (New York) 2017;24(4):396–420. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers EM. Diffusions of Innovations. 4. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabassa LJ. Implementation Science: Why it matters for the future of social work. J Soc Work Educ 2016;52(Suppl 1):S38-S50. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28216992). Accessed 28 June 2022. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Chambers DA, Norton WE. The Adaptome: Advancing the Science of Intervention Adaptation. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4 Suppl 2):S124–S131. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Statistics at a Glance, Veteran Population Projection Model (VetPop) 2018. Veterans Benefits Administration, Veterans Health Administration, Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. 6/30/21 https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Quickfacts/Stats_at_a_glance_6_30_21.PDF. Accessed 31 August 2022.

- 13.Hayes P. Diversity, equity, inclusion – VA goals. 7/22/21 https://blogs.va.gov/VAntage/92022/diversity-equity-inclusion-va-goals/#:~:text=Today%2C%20about%2027%25%20of%20Veterans%20are%20members%20of,belonged%20to%20a%20racial%20or%20ethnic%20minority%20group. Accessed 28 June 2022.

- 14.Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Employment Toolkit. 7/7/21 https://www.va.gov/VETSINWORKPLACE/mil_culture.asp. Accessed 28 June 2022.

- 15.Falca-Dodson M. Why Military Culture Matters: The Military Member’s Experience. Presented by the Department of Veterans Affairs War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC). https://www.warrelatedillness.va.gov/education/conferences/2010-sept/slides/2010_09_15_Falca-DodsonM-Why-Military-Culture-Matters.ppt. Accessed 28 June 2022.

- 16.Cotner BA, Ottomanelli L, Keleher V, Dirk L. Scoping review of resources for integrating evidence-based supported employment into spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(14):1719–1726. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1443161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olenick M, Flowers M, Diaz VJ. US veterans and their unique issues: enhancing health care professional awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:635–639. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S89479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Syst. 2008;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesising research evidence. In: Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, Black N, editors. Studying the Organization and Delivery of Health Services: Research Methods. London: Routledge; 2001. pp. 188–220. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abraham TH, Marchant-Miros K, McCarther MB, et al. Adapting Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management for Veterans Affairs Community-Based Outpatient Clinics: Iterative Approach. JMIR Ment Health. 2018;5(3):e10277. doi: 10.2196/10277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arney J, Thurman K, Jones L, et al. Qualitative findings on building a partnered approach to implementation of a group-based diabetes intervention in VA primary care. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e018093. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blonigen D, Harris-Olenak B, Kuhn E, Humphreys K, Timko C, Dulin P. From, "Step Away" to "Stand Down": Tailoring a Smartphone App for Self-Management of Hazardous Drinking for Veterans. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(2):e16062. doi: 10.2196/16062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Day SC, Day G, Keller M, et al. Personalized implementation of video telehealth for rural veterans (PIVOT-R) Mhealth. 2021;7:24. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2020.03.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dyer KE, Moreau JL, Finley E, et al. Tailoring an evidence-based lifestyle intervention to meet the needs of women Veterans with prediabetes. Women Health. 2020;60(7):748–762. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2019.1710892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King K, Gosian J, Doherty K, et al. Implementing yoga therapy adapted for older veterans who are cancer survivors. Int J Yoga Therap. 2014;24:87–96. doi: 10.17761/ijyt.24.1.622x224527023342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leonard C, Gilmartin H, McCreight M, et al. Operationalizing an Implementation Framework to Disseminate a Care Coordination Program for Rural Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(Suppl 1):58–66. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04964-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):91–113. doi: 10.1037/a0020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yano EM, Rubenstein LV, Farmer MM, et al. Targeting primary care referrals to smoking cessation clinics does not improve quit rates: implementing evidence-based interventions into practice. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(5 Pt 1):1637–1661. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00865.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoerster KD, Tanksley L, Simpson T, et al. Development of a Tailored Behavioral Weight Loss Program for Veterans With PTSD (MOVE!+UP): A Mixed-Methods Uncontrolled Iterative Pilot Study. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34(6):587–598. doi: 10.1177/0890117120908505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blonigen DM, Cucciare MA, Timko C, et al. Study protocol: a hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial of Moral Reconation Therapy in the US Veterans Health Administration. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2967-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chinman M, Henze K, Sweeney P. Peer specialist toolkit: implementing peer support services in VHA. http://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn4/docs/Peer_Specialist_Toolkit_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 3 November 2022.

- 35.Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Udelson H, et al. A scoping study of frameworks for adapting public health evidence-based interventions. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shepherd HL, Geerligs L, Butow P, et al. The Elusive Search for Success: Defining and Measuring Implementation Outcomes in a Real-World Hospital Trial. Front Public Health. 2019;7:293. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frayne S, Phibbs CS, Saechao FS, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 4: Longitudinal Trends in Sociodemographics, Utilization, Health Profile, and Geographic Distribution. Washington DC: February 2018 2018. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/WHS_Sourcebook_Vol-IV_508c.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2022.

- 39.National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran Population Projections 2020–2040; Source: VA Veteran Population Projection Model 2018. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Demographics/New_Vetpop_Model/Vetpop_Infographic2020.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2022.

- 40.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.WiltseyStirman S, La Bash H, Nelson D, Orazem R, Klein A, Sayer NA. Assessment of modifications to evidence-based psychotherapies using administrative and chart note data from the US department of veterans affairs health care system. Front Public Health. 2022;10:984505. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.984505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].