INTRODUCTION

The United States (U.S.) Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision overturned the constitutional right to abortion. Abortion restrictions are in place or are expected in 26 states.1 While not all physicians perform abortions, the bans broadly impact healthcare delivery for reproductive age patients, including many physicians themselves or their family members. Previous research demonstrates 67% of physicians support abortion access.2 Despite wide speculation by media or policymakers, no published study to date has described how state abortion restrictions may influence practice location preferences for physicians and trainees.3

METHODS

Between August 12 and 23, 2022, a non-probabilistic sample of physicians and trainees was recruited via social media communities (physician and student Facebook groups, Instagram stories on influential medical accounts, Twitter hashtags #MedTwitter #MedStudentTwitter). U.S. medical students and international medical graduates (IMGs) applying to U.S. residency programs, residents, fellows, and physicians in all specialties were eligible. A Qualtrics bot detector identified and removed likely bots (n = 5, 0.2%), and duplicate responses were disabled.

The survey collected demographics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, relationship status, specialty, and practice location by state). Questions included respondents’ intent to apply to train or work in states with abortion restrictions (complete or early ban, emergency contraception ban, legal consequences for providing abortions).

States were classified by abortion laws in effect during the study.4 Chi-square tests examined differences in perceptions by level of training. Analyses were conducted using SPSS 25 with p < 0.05 denoting statistical significance. This survey study followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research reporting guidelines, and was exempt by The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.5

RESULTS

In total, 2063 respondents completed the survey, including 890 respondents from states with current or likely abortion bans (43.9%) (see Table 1).4 Most (1575 [76.3%]) respondents identified as women. There were 757 U.S. medical students and 134 IMGs (combined 891 [43.2%]), 513 (24.9%) residents and fellows, and 659 (31.9%) practicing physicians.

Table 1.

Demographics of Medical Students (n = 891), Residents and Fellows (n = 513), and Practicing Physicians (n = 1172)

| Characteristic | Total n (%) |

Medical students n (%)a |

Residents and fellows n (%) |

Practicing physicians n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genderb | ||||

| Woman | 1575 (76.3) | 654 (73.4) | 399 (77.8) | 523 (79.2) |

| Man | 403 (19.5) | 180 (20.2) | 102 (19.9) | 121 (18.3) |

| Transgender male | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Transgender female | 0 | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Gender queer | 28 (1.4) | 21 (2.4) | 3 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) |

| Prefer to describe | 7 (0.3) | 4 (0.4) | 0 | 3 (0.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 43 (2.1) | 28 (3.1) | 7 (1.4) | 8 (1.2) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 171 (8.3) | 103 (11.6) | 36 (7.0) | 32 (4.9) |

| Not Hispanic | 1826 (88.5) | 757 (85.0) | 463 (90.3) | 606 (92.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 66 (3.2) | 31 (3.5) | 14 (2.7) | 21 (3.2) |

| Race^c | ||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 6 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Asian | 262 (12.7) | 116 (13.0) | 62 (12.1) | 84 (12.7) |

| Black, African American, or African | 110 (5.3) | 62 (7.0) | 36 (7.0) | 12 (1.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | 0 |

| Multiracial†† | 102 (4.9) | 43 (4.8) | 28 (5.5) | 31 (4.7) |

| White | 1408 (68.3) | 566 (63.5) | 349 (68.0) | 493 (74.8) |

| Prefer to describe | 53 (2.6) | 35 (3.9) | 7 (1.4) | 11 (1.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 119 (5.8) | 65 (7.3) | 27 (5.3) | 27 (4.1) |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Bisexual | 181 (8.8) | 105 (11.8) | 41 (8.0) | 35 (5.3) |

| Gay or lesbian | 80 (3.9) | 29 (3.3) | 18 (3.5) | 33 (5.0) |

| Heterosexual | 1632 (79.1) | 659 (74.0) | 427 (83.2) | 546 (82.9) |

| Queer, pansexual, and/or questioning | 90 (4.4) | 47 (5.3) | 17 (3.3) | 26 (3.9) |

| Don’t know | 10 (0.5) | 10 (1.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Prefer to describe | 10 (0.5) | 7 (0.8) | 0 | 3 (0.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 60 (2.9) | 34 (3.8) | 10 (1.9) | 16 (2.4) |

| Aged | ||||

| ≤ 44 | 1849 (89.6) | 891 (99.6) | 508 (99.0) | 454 (68.9) |

| ≥ 45 | 214 (10.4) | 4 (0.4) | 5 (1.0) | 205 (31.1) |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Single | 521 (25.3) | 324 (36.4) | 119 (23.2) | 78 (11.8) |

| Partnered | 534 (25.9) | 352 (39.5) | 143 (27.9) | 39 (5.9) |

| Married | 943 (45.7) | 194 (21.8) | 241 (47.0) | 508 (77.1) |

| Widowed | 6 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 6 (0.9) |

| Divorced | 20 (1.0) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 16 (2.4) |

| Other | 8 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 31 (1.5) | 16 (1.8) | 7 (1.4) | 8 (1.2) |

| Children | ||||

| Yes | 612 (29.7) | 73 (8.2) | 95 (18.5) | 444 (67.4) |

| No | 1451 (70.3) | 818 (91.8) | 418 (81.5) | 215 (32.6) |

| Respondent’s current state of residence, by anticipated abortion restrictione | ||||

| Ban/likely banf | 890 (43.9) | 430 (50.1) | 209 (40.7) | 251 (38.3) |

| Legalg | 1137 (56.1) | 429 (49.9) | 304 (59.3) | 404 (61.7) |

| Intend to provide abortion careh | ||||

| Yes | 560 (27.1) | 322 (36.2) | 130 (25.3) | 108 (16.4) |

| No | 1503 (72.9) | 569 (63.9) | 383 (74.7) | 551 (83.6) |

††Respondents who selected more than one option are considered multiracial for the purpose of this study

aIncludes U.S. medical students (n = 757) and international medical graduates applying to U.S. residency programs (n = 134)

bNationally, medical students 47.9% female and 52.9% male,7 residents and fellows 46.8% female and 53.0% male,7 and practicing physicians 35.9% female and 64.1% male7

cNationally, medical students 0.2% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 54.6% White, 21.6% Asian, 6.2% Black or African American, 5.3% Hispanic, 8% multiple races, and 3.5% other.7 Nationally, residents and fellows 0.11% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 48.9% White, 26.6% Asian, 6.0% Black or African American, 9.2% Hispanic, 4.0% multiple races, and 3.1% other.8 Nationally, practicing physicians 0.1% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 63.9% White, 19.2% Asian, 3.6% Black or African American, 5.5% Hispanic, 2.0% multiple races, and 5.6% other7

dAge 44 per CDC3

eIncludes all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia. Excludes the 36 respondents who indicated “other” on their location

fAlabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming4

gAlaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington4

hIncludes physicians, residents, fellows, and medical students in all fields

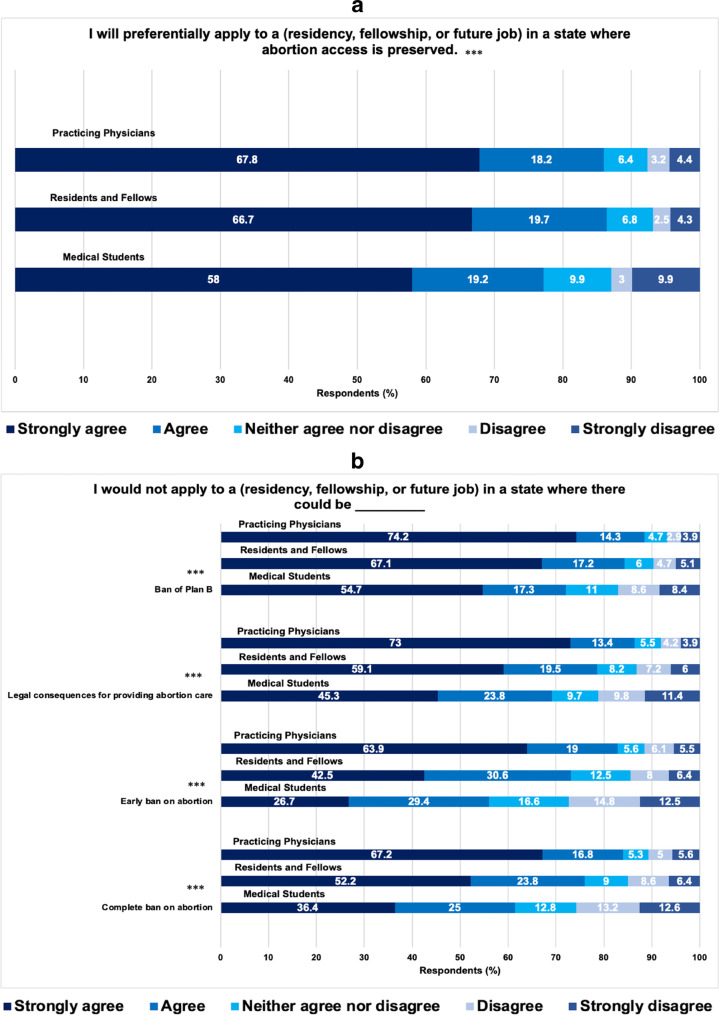

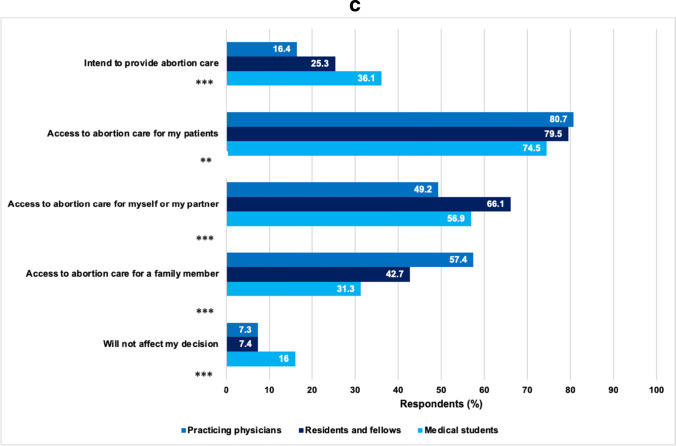

Outcomes by level of training appear in Fig. 1. Most respondents reported (82.3%) they preferred to apply to work or train in states with preserved abortion access. Three-quarters (76.4%) of respondents would not apply to states with legal consequences for providing abortion care. While these preferences were stronger among those in states without abortion bans, most respondents living in ban/likely ban states still preferred not to work in states with complete (61.3%, p < 0.001) or early (56%, p < 0.001) bans. Reasons for these preferences included preserving patients’ access to care (77.8%) and preserving access to care for themselves or their partner (56.1%). Few (11.1%) reported the Dobbs decision would not affect their preferences. Of note, the majority of male physicians in our sample also preferred to train and practice in states where abortion access is preserved (66.4%).

Fig. 1.

a Impact of Roe v. Wade on preferential application to states where abortion access is preserved for medical students (n = 891), residents and fellows (n = 513), and practicing physicians (n = 1172). b Impact of Roe v. Wade on applications to states with reproductive health care restrictions for medical students (n = 891), residents and fellows (n = 513), and practicing physicians (n = 1172). c Why will overturning Roe v. Wade impact where you apply? Medical students (n = 891), residents and fellows (n = 513), and practicing physicians (n = 1172)

Current and future abortion care providers (n = 560) reported a stronger preference to apply to work in states preserving abortion access (99.3% abortion provider vs 87.0% others, p < 0.001), and more often attributed this preference to preserving abortion access for their patients (95% abortion provider vs 71.3% others, p < 0.001), or themselves or a family member (70.4% abortion provider vs 51.6% others, p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

In this social media survey study, the majority of physicians and trainees preferred to apply to train and practice in states that preserved abortion access. While those who provide abortions had stronger preferences, the majority of non-abortion providers also preferred practicing in states without complete or early abortion bans, a ban on Plan B, or legal consequences for abortion providers.

Our study limitations include self-selection bias and a non-representative sample of U.S. physicians, with more female and white participants. Our results may not generalize to physicians not using social media. Actual geographic preferences are also influenced by factors other than abortion access.

Of the 12 states with current or anticipated abortion bans as of August 23, 2022, 11 have below-average numbers of active physicians per 100,000 people.4,6 Our data highlight that even if a fraction of the many physicians and trainees with strong geographic preferences to avoid practicing in states that ban abortion follow through on their preferences, states that ban abortion are at risk for exacerbating these existing physician shortages, and worsening health outcomes for their citizens.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available to respect the privacy of participants.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Simone A. Bernstein and Morgan S. Levy are co-first authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/5/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s11606-024-08985-3

References

- 1.Center for Reproductive Rights. After Roe Fell: Abortion Laws by State. https://reproductiverights.org/maps/abortion-laws-by-state/. Published July 27, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2022.

- 2.Team Sermo. 67% of doctors support access to abortion. Sermo. https://www.sermo.com/blog/insights/67-of-doctors-support-access-to-abortion/. Published July 14, 2022. Accessed January 5, 2023.

- 3.Vinekar K, Karlapudi A, Nathan L, Turk JK, Rible R, Steinauer J. Projected implications of overturning Roe v Wade on abortion training in U.S. Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency Programs. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(2):146-149. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000004832 10.1097/aog.0000000000004832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The New York Times. Tracking the States Where Abortion Is Now Banned. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/us/abortion-laws-roe-v-wade.html. Published May 24, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2022.

- 5.American Association of Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys, 9th Edition. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed August 30, 2022.

- 6.American Association of Medical Colleges. 2021 State Physician Workforce Data Report. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/506/. Published 2021. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 7.American Association of Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019. Accessed January 10, 2023.

- 8.ACGME Data Resource Book 2021–2022. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. https://www.acgme.org/about-us/publications-and-resources/graduate-medical-education-data-resource-book/. Accessed January 10, 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available to respect the privacy of participants.