Abstract

Currently, obtaining accurate medical annotations requires high labor and time effort, which largely limits the development of supervised learning-based tumor detection tasks. In this work, we investigated a weakly supervised learning model for detecting breast lesions in dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) with only image-level labels. Two hundred fifty-four normal and 398 abnormal cases with pathologically confirmed lesions were retrospectively enrolled into the breast dataset, which was divided into the training set (80%), validation set (10%), and testing set (10%) at the patient level. First, the second image series S2 after the injection of a contrast agent was acquired from the 3.0-T, T1-weighted dynamic enhanced MR imaging sequences. Second, a feature pyramid network (FPN) with convolutional block attention module (CBAM) was proposed to extract multi-scale feature maps of the modified classification network VGG16. Then, initial location information was obtained from the heatmaps generated using the layer class activation mapping algorithm (Layer-CAM). Finally, the detection results of breast lesion were refined by the conditional random field (CRF). Accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) were utilized for evaluation of image-level classification. Average precision (AP) was estimated for breast lesion localization. Delong’s test was used to compare the AUCs of different models for significance. The proposed model was effective with accuracy of 95.2%, sensitivity of 91.6%, specificity of 99.2%, and AUC of 0.986. The AP for breast lesion detection was 84.1% using weakly supervised learning. Weakly supervised learning based on FPN combined with Layer-CAM facilitated automatic detection of breast lesion.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Computer-aided detection, Weakly supervised learning, Class activation mapping, Feature pyramid network

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common type of cancer diagnosed all over the world (after lung cancer). Worse still, it is the leading cause of cancer death among women [1]. Early symptoms of breast cancer are typically dominated by breast lumpiness, pain, and nipple discharge, which can be easily missed and delay diagnosis and treatment. In the advanced stage, breast cancer has the potential for systemic metastasis, threatening patient survival. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) has significance for detecting and diagnosing breast lesions, which provides comprehensive diagnostic information with advantages of high spatial resolution, multiple sequence imaging, and superb tissue contrast [2]. Currently, computer-aided detection (CADe) is one of the research priorities to improve the efficiency of MRI interpretation by radiologists. In addition to automatic analysis of lesion location and morphology, an effective CADe system also provides pathological characteristics of breast carcinomas, such as molecular subtypes [3–5] and early prognosis assessment [6–9]. However, automatic breast tumor detection is full of challenges because of the irregular shape of lesions and fuzzy boundaries.

The conventional approaches utilized for breast lesion detection in DCE-MRI can be categorized as manual feature engineering for low-level image features [10, 11] and decisions based on thresholding or clustering analysis [12], which have poor generalization to identify those lesions with blurred and irregular boundaries. Recently, deep learning implemented with supervised learning algorithms has achieved significant success for recognizing breast masses, including Faster R-CNN [13] and RetinaNet [14]. These methods ease the burden of designing artificial features and combine context information from imaging sequences to obtain semantic representations at different levels. Owing to the improved computational performance, deep learning algorithms can efficiently detect malignant or benign breast tumors with stronger robustness than traditional methods. Nevertheless, supervised learning-based object detection still depends on high-quality datasets with pixel-level or bounding box labels, which are susceptible to the subjective judgments of specialized staff. Thus, achieving fantastic results via low-cost image annotations has become a research hotspot in the field of breast lesion detection.

Currently, many weakly supervised based strategies are developed that rely only on the image-level labels. However, a few similar studies on the DCE-MRI breast lesion detection tasks are reported in literatures, following a typical workflow from suspicious region extraction to false positive detection [15–17]. In convolutional neural networks (CNNs), the outputs of convolutional layers contain positional information corresponding to the crucial representations for lesion classification. Thus, those lesions can be detected using the feature maps of intermediate layers. For instance, Zhou et al. [18] first built a 3D DenseNet-based breast tumor classification network. Afterwards, the class activation mapping (CAM) was utilized to weight features from the middle layers, which were then fused to obtain the initial breast tumor regions, indicating the feasibility of tumor detection with weakly supervised learning [19]. As shown in the experimental results, CAM only detected ambiguous lesion locations, the edges of which needed to be further constrained. Furthermore, the minimization of false positives was also critical to consider.

Weakly supervised learning provides a novel idea for breast lesion detection, greatly reducing the cost and subjectivity of manual annotation. However, most of the networks employed in the above studies are classical for natural images, such as VGG16 [20], ResNet [21], and Faster R-CNN [22]. Therefore, this study compares performance of different model architectures on breast lesion detection using weakly supervised learning and explores the potential application value of our proposed CNN combined with Layer-CAM to perform auxiliary tumor detection in DCE-MRI.

Materials and Methods

MRI Protocols

DCE-MRI was performed on a 3.0-T (PHILIPS Ingenia) scanner with a specific breast coil to extract T1-weighted fat suppression scanning sequences containing one precontrast (termed S0) and four contrast-enhanced series (referred as S1–S4). The injected contrast medium was GD-DTPA (0.1 mmol/kg, 2.0 mL/s). The scanning time between each consecutive sequence was 65.4 s. Acquisition parameters were TR/TE = 4.2/2.1 ms, flip angle = 12°, field of view = 340 × 340 mm, and original image matrix = 576 × 576. Each sequence contained 150 images. In this study of weakly supervised learning, the second postcontrast MRI series S2 was preprocessed and utilized as the input of the network due to its optimal early enhancement for breast lesions among four contrast-enhanced sequences [3, 23, 24].

Experimental Design and Dataset

We retrospectively studied 254 normal cases with no enhanced or suspicious lesions and 993 breast abnormalities (643 benign and 350 malignant cases) diagnosed between 2015 and 2019 from the partner hospital. Five hundred ninety-five abnormal cases were excluded because of the postoperative MRI (N = 241), implanted prostheses (N = 17), poor-quality DCE-MRI images (N = 84), significant artifacts (N = 42), incomplete imaging acquisition (N = 24), multifocal lesions less than 5 mm in diameter (N = 130), and lack of pathological reports (N = 57). Finally, a total of 398 abnormalities with clear images, complete sequences, and pathologically confirmed diagnosis were enrolled in this study. The dataset was randomly divided into training (80%), validation (10%), and testing sets (10%) at the patient level; i.e., all images from the same case could not exist in both subsets to prevent data leakage. Table 1 depicts the clinical characteristics of the cohort.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the collected dataset

| Characteristics a |

Training set (N = 532) |

Validation set (N = 59) |

Testing set (N = 61) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 19–81 | 38–77 | 42–77 |

| BI-RADS | |||

| III | 8 | 3 | 2 |

| IV | 50 | 11 | 14 |

| V | 267 | 22 | 21 |

| Tumor size | |||

| cT1 | 129 | 15 | 5 |

| cT2 | 117 | 14 | 20 |

| cT3 | 79 | 7 | 12 |

| Pathological types | |||

| Invasive carcinoma | 233 | 29 | 30 |

| Carcinoma in situ | 60 | 6 | 5 |

| Benign | 32 | 1 | 2 |

| Normal | 207 | 23 | 24 |

aN is the sum of the number of normal and abnormal cases

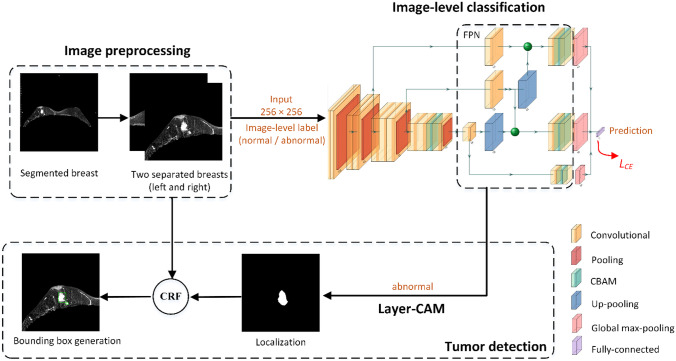

The detailed experimental procedures are shown in Fig. 1. First, the images were preprocessed to remove regions outside the bilateral breasts. Second, these preprocessed images were used to train the proposed classification model based on a feature pyramid network (FPN) and convolutional block attention modules (CBAM) [25, 26] with the output being the absence or presence of breast tumors (normal or abnormal). Then, obtaining initial tumor positions from the classification network by a layer class activation mapping (Layer-CAM) method [27]. Finally, the conditional random field (CRF) was employed to refine tumor regions and generate bounding boxes [28].

Fig. 1.

Workflow of the weakly supervised method for breast tumor detection. Layer-CAM denotes the layer class activation mapping, CRF indicates the conditional random field algorithm, and FPN means the feature pyramid network. The cross-entropy loss function LCE is utilized to optimize the image-level classification network

Image Preprocessing

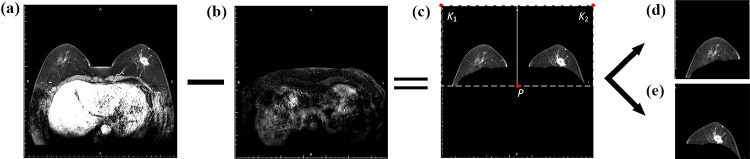

The gray values for breast tissue and other organs were approximately consistent with those for tumors, which produced a risk of false positives when identifying breast masses in DCE-MRIs. In this study, the preprocessing steps were essential to hinder noise interference and reduce computational cost, which are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Breast region segmentation. The final slice from the DCE-MRI S2 phase was selected to be filtered with a Gaussian filter (kernel size = 5 × 5), and then processed by Otsu binarization and morphological algorithms to obtain a mask of the chest region, including open operation with the disk-shaped structuring element (r = 3), connected area extraction, and hole-filling. Next, each slice from S2 was matched with the mask translated down by 20 pixels. Finally, the overlapping areas were subtracted to obtain the complete breast region.

-

Separation of two breasts. As illustrated in Fig. 2c, the point was extracted for separation of right and left breasts in each image, where denotes the horizontal coordinate of the middle point in the image and represents the vertical coordinate of the bottom point with pixel value greater than 10. The upper left and right pixels of the original image were used as two boundary points, which were combined with the point P to separate two breasts, respectively. Each image patch was resized to 256 × 256 pixels and normalized in intensity using the factor of 1/255. Subsequently, data augmentation techniques were employed in the training set to avoid overfitting of the model and improve its generalization, which included (1) random shifting of ± 10% in width or height and (2) random shearing of ± 10%.

The image-level labels (normal or abnormal) for all cases were confirmed from pathological reports via two pathologists with 6 years of experience in breast diagnosis. For breast detection, bounding box annotations that localized breast lesions in the validation and testing sets were delineated by consensus between two radiologists, who have 6 and 8 years of experience in image reading for breast disease.

Fig. 2.

Graphic illustration of image preprocessing. a The slice in the second DCE-MRI time sequence; b a mask of chest region; c the segmented breasts; d and e two sub-images of right and left breasts

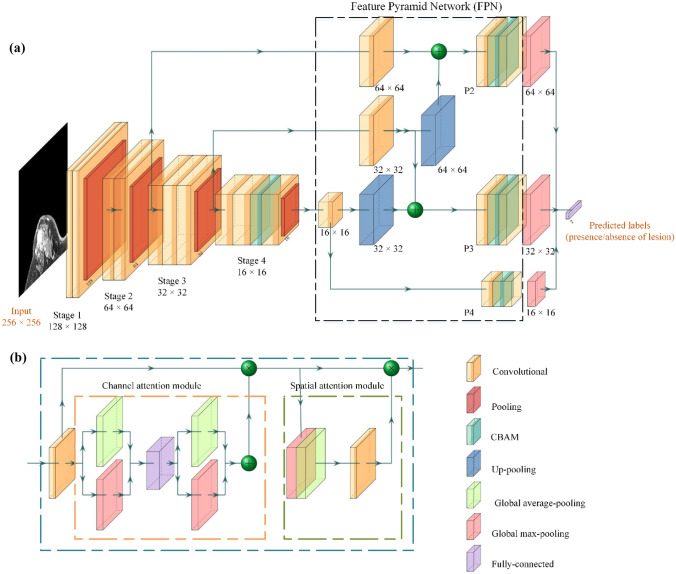

Classification Network Structure

The illustration of our proposed CNN is shown in Fig. 3a. A customized deep learning architecture with preprocessed DCE-MRI S2 series as input was developed to extract and fuse different level representations for binary prediction (normal or abnormal). The main structure of our proposed network adopted convolutional layers with 3 × 3 and 1 × 1 (bottleneck) filters. VGG16 with four stages served as the backbone network, and CBAM (Fig. 3b) was added to the last convolutional layer of the fourth stage to emphasize representative features that were beneficial for classification. With respect to FPN, three 1 × 1 convolutional layers with 256 convolutional kernels were added to each skip connection, respectively. They were leveraged to achieve dimensional reduction and informative interactions between channels. Subsequently, the intermediate features were fed into three high-level feature extractors (P2–P4), which consisted of a 3 × 3 convolutional layer with 128 convolutional kernels followed by a CBAM, a 1 × 1 convolutional layer with two convolutional kernels, and a global max-pooling (GMP) layer, respectively. Finally, the multi-level representative knowledge was combined and transmitted to a fully connected layer to discriminate the presence of lesion or not (normal or abnormal).

Fig. 3.

Overview of the network structure. a The classification network; b the convolutional block attention module (CBAM). The notation “n × n” denotes the output size of the block

Lesion Detection

In the stage of weakly supervised breast lesion detection, an optimized CAM method, termed Layer-CAM, was employed to generate heatmaps of positive images (with lesions) predicted by the proposed classification network, which could present coarse regions without additional bounding box annotations. Specifically, the class activation map was extracted before the GMP of P3 and up-sampled to 256 × 256 pixels to achieve preliminary tumor localization. Next, the pixels with the top five grayscale values were used as seed points for region growth of the coarse binary masks in lesion regions.

Furthermore, the CRF algorithm was utilized to refine the initial localization results and generate bounding boxes, which can be achieved by optimizing the posterior probability subjected to Gibbs distribution in Eq. (1):

| 1 |

where, represents the set of pixel labels (lesion or background) and is described as the observed gray value of . refers to the number of pixels. denotes the normalization term, which can be expressed in Eq. (2):

| 2 |

As calculated in Eq. (3), is the sum of all potential energies, including the unary potential and the pairwise potential :

| 3 |

where describes the class probability of pixel obtained from heatmaps by CAM, which can be formulated as follows:

| 4 |

The pairwise potential took into account the relationship between context information (intensity) and spatial consistency (position) for all pixels, which is achieved by a linear combination of Gaussian kernels, as follows:

| 5 |

where the spatial standard deviation (SD) and the color SD determine the degree of position and grayscale similarity between two pixels, respectively, while the smoothness SD is responsible for generating sharp boundaries of regions and removing small isolated points. and denote the weighting factors of Gaussian kernels. We set by default. The penalty term is introduced to control the pairwise potential between nearby pixels with different classes, which can be given by:

| 6 |

In this study, the parameters in CRF (i.e., , , in Eq. (5)) were fine-tuned using the validation set with bounding box annotations in manual iterations until the validation AP was optimal. Therefore, the mask feature representation was combined with information from the original breast image, including the texture, shape, and location of the lesion. Finally, we explicitly delineated a minimal rectangular bounding box around the refined region of breast lesion.

Statistical Analysis

The evaluation metrics for classification included accuracy (Acc), sensitivity (Sen), specificity (Spec), and area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) at the image level [29]. Average precision (AP) referred to the area under precision-recall curve and was estimated for the breast lesion detection. Delong’s test preformed on MedCalc (Ver. 20.100) was utilized to assess AUCs between different models. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Experiments and Results

Implementation Details

The proposed network architecture was implemented in Python 3.6 with the deep learning platform of Keras on an image analysis workstation with Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU of 2.4 GHz, RAM 64 GB, NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 Ti graphic processing unit, and Windows-10 64 bit. Several available packages were employed to preprocess images, e.g., scikit-image, SciPy. The cross-entropy algorithm served as the loss function, and Adam optimizer (lr = 10–5, β_1 = 0.9, β_2 = 0.999) was employed to train and update gradient of the network. The training epoch was set as 100 and batch size = 4. Model weights were saved when the accuracy reached its maximum in validation set or when 100 epochs were iterated.

Performance of Classification Models

Different deep learning frameworks were compared to estimate their classification performance using image-level labels of breast DCE-MRIs (normal or abnormal). As shown in Table 2, the classification performance of VGG16 had more comprehensive advantages than Pre-VGG16, S-ResNet50 and S-DenseNet121 in terms of AUC (0.968 vs. 0.923, 0.965, and 0.961, P < 0.05). Therefore, the structure of VGG16 was regarded as the backbone of classification model. Furthermore, when FPN and CBAM were incorporated to VGG16 simultaneously, it achieved the highest accuracy of 95.2% and optimal AUC of 0.986, which significantly outperformed that with the single CBAM or FPN (P < 0.05). The fact that the minimal gap between sensitivity and specificity (7.6%) also indicated that the robustness and structural stability of VGG16 + FPN + CBAM. We attributed this to the highlight of multi-scale imaging characteristics derived from FPN by optimizing CBAM.

Table 2.

Performance comparison between different classification models

| Model | GFLOPs c | Acc | Sen | Spec | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG16 | 20.0 | 0.900 | 0.980 | 0.888 | 0.968 |

| Pre-VGG16 a | 20.0 | 0.855 | 0.945 | 0.774 | 0.923 |

| S-ResNet50 b | 5.0 | 0.894 | 0.965 | 0.895 | 0.965 |

| S-DenseNet121 b | 3.7 | 0.901 | 0.985 | 0.851 | 0.961 |

| VGG16 + CBAM | 27.3 | 0.782 | 0.812 | 0.732 | 0.802 |

| VGG16 + FPN | 27.3 | 0.634 | 0.486 | 0.782 | 0.669 |

| VGG16 + FPN + CBAM | 27.3 | 0.952 | 0.916 | 0.992 | 0.986* |

*Significance difference was observed between the AUC of VGG16 + FPN + CBAM and that of other networks

aThe simplified VGG16 was pretrained on the ImageNet

bThe fully connected layer of models was simplified to two layers, each containing 128 convolutional kernels

cThe giga floating point of operations (GFLOPs) was used to evaluate model complexity

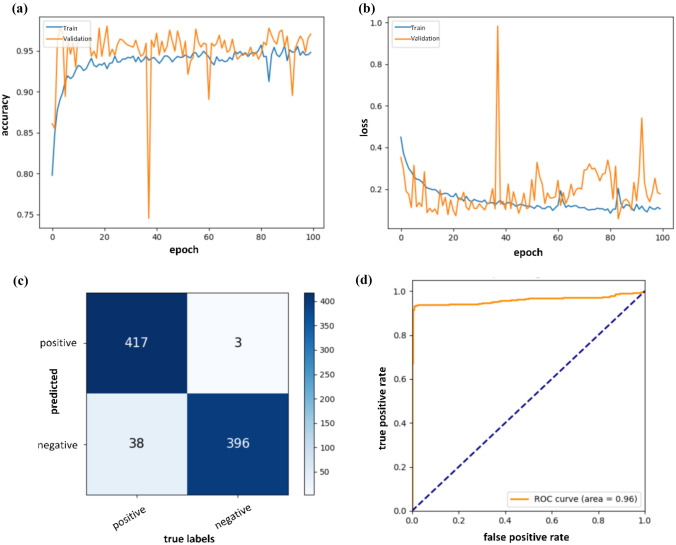

Next, two groups of ablation experiments were performed to assess the classification capabilities of different VGG16 backbones (with four or five stages) and high-level feature extractors from FPN (the 1 × 1 convolutional layer with kernel number of 2 or 64). Quantitative results summarized in Table 3 showed that the prediction model equipped with VGG16 of the fifth stage had significantly lower performance than that without the fifth stage in distinguishing the presence of lesions or not in breast DCE-MRIs (AUC: 0.977 vs. 0.986, P < 0.05). Furthermore, the overall discriminative power was improved when the kernel number of 1 × 1 convolutional layer in FPN was reduced from 64 to 2, achieving optimal sensitivity of 91.6%, specificity of 99.2%, AUC of 0.986, and statistically outperforming other models. These results demonstrated that a reasonable network design decreased the computational complexity and had a more positive impact on the discrimination task than a complex model structure. Accordingly, the best configuration of the classification network was adopt as follows: VGG16 with four stages, FPN composed of the high-level feature extractor, where the kernel numbers of 1 × 1 convolutional layers were set as 2. Figure 4 exhibits the training process in 100 epochs, confusion matrix and ROC curve evaluated at the image level using the testing set. The validation curve gradually converged and reached the optimal value at the 72th epoch during the training process. The small loss gap between the training and validation sets represented that overfitting was well prevented. A sudden rise in the validation loss indicated that some images were misclassified, most likely due to small differences in the feature maps after image normalization.

Table 3.

Classification performance with different configurations of VGG16 + FPN + CBAM

| Model | Stages | Kernels | GFLOPs a | Sen | Spec | Acc | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG16 + FPN + CBAM | 4 | 2 | 27.3 | 0.916 | 0.992 | 0.952 | 0.986* |

| 4 | 64 | 27.3 | 0.895 | 0.987 | 0.938 | 0.965 | |

| 5 | 2 | 29.1 | 0.903 | 0.995 | 0.946 | 0.977 | |

| 5 | 64 | 29.2 | 0.897 | 0.985 | 0.938 | 0.972 |

*Significance difference of AUC was found between other network configurations and the VGG16 + FPN + CBAM with stages = 4, and kernels = 2

aThe giga floating point of operations (GFLOPs) was used to evaluate model complexity

Fig. 4.

Accuracy a, loss b, confusion matrix c, and ROC d curves of the proposed classification network. In (c), positive or negative denotes the presence of breast lesions or not, respectively

Weakly Supervised Object Localization

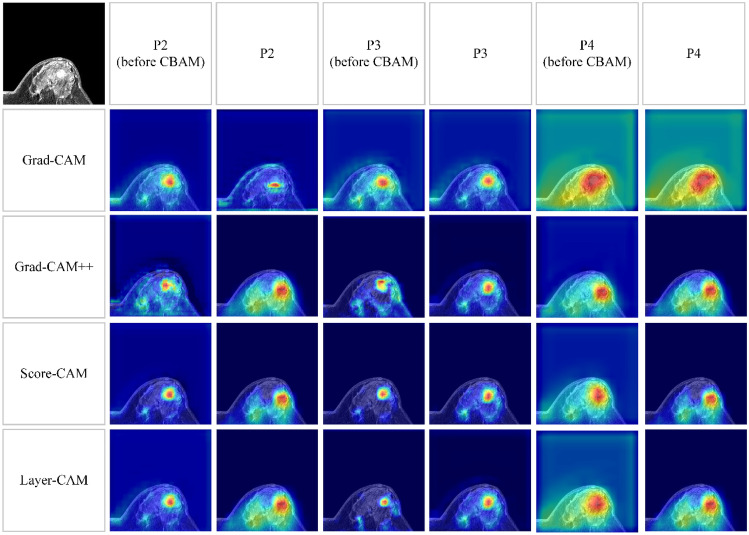

As visualized in Fig. 5, the more attention the model pays, the higher response on the class activation maps. On these class activation maps generated by different CAM methods, those highlighted pixels were successfully concentrated around the selected breast lesion. However, a series of response maps derived from high-level feature extractors (P2, P4 before CBAM, and P4) were accompanied by significant noise utilizing the Grad-CAM + + [30], Layer-CAM, and Score-CAM [31]. Differently, P3 and P3 before CBAM were more reliable and facilitated four CAM methods to draw high attention to tumor-related regions, and thus realized initial localization of breast lesion. In contrast to Grad-CAM [32], all other algorithms failed to extract accurate response maps from P2, which localized irrelevant tissue information of MR imaging patches. We speculated that the gradients of feature maps varied due to the weights controlled by CBAM. Therefore, the class activation maps generated from P2 before CBAM were regarded as the benchmarks. Quantitative evaluation metrics were further analyzed to compare the detection performance using different CAM methods on P2 before CBAM, P3, and P4, which are summarized in Table 4. In all four CAM algorithms, primary tumor information was difficult to be derived from the high-level feature extractor of the P4 branch. APs less than 0.5% represented failures in fitting the predicted bounding boxes to the real tumor regions. This was likely attributed to the increased resolution of the class activation maps (from 16 × 16 to 256 × 256), which resulted in an offset of the detected ROIs. Comparatively, the more prominent detection performance could be obtained from two extractors of P3 and P2 before CBAM, which significantly outperformed P4 (the optimal APs of 55.3% and 71.2% vs. 0.5%, P < 0.05). In addition, we observed that Layer-CAM achieved the highest results using the P3 high-level feature extractor, which was also faster in terms of computational power with less resources than Score-CAM on P2 before CBAM (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Location information extracted from three high-level feature extractors by different CAM methods. The representative imaging patch is displayed at the upper-left corner. P2–P4 indicate that the class activation maps are generated from the last 1 × 1 convolutional layer of three high-level feature extractors, respectively. P2–P4 (before CBAM) means the class activation maps are extracted from the 3 × 3 convolutional layer before CBAM

Table 4.

Detection performance on three high-level feature extractors with different CAM methods

| CAMs | P2 before CBAM | P3 | P4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AP before CRF |

AP after CRF |

AP before CRF |

AP after CRF |

AP before CRF |

AP after CRF |

|

| Grad-CAM | 0.551 | 0.610 | 0.598 | 0.658 | 0.001 | 0.016 |

| Grad-CAM + + | 0.347 | 0.391 | 0.552 | 0.620 | 0.001 | 0.012 |

| Score-CAM | 0.553 | 0.571 | 0.452 | 0.529 | 0.002 | 0.013 |

| Layer-CAM | 0.396 | 0.484 | 0.712 | 0.841 | 0.005 | 0.017 |

We report the AP after CRF in bold if it is statistically significantly different from the AP before CRF at the significance level of 0.05

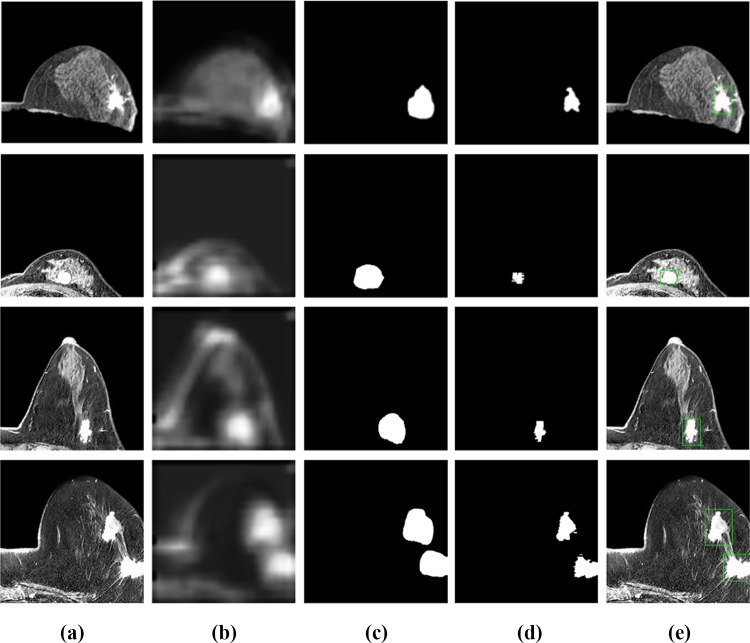

Furthermore, the coarse binary masks extracted by Layer-CAM were processed using the fully connected CRF. The improved AP of 0.841 in the testing set demonstrated that breast tumors were located much more precisely (P < 0.05). Figure 6 shows four cases processed by the successive steps. Intuitively, the CRF method could effectively refine and enhance the accuracy of labeling tumor locations.

Fig. 6.

Optimization of the breast lesion detection. a The preprocessed image patches; b the layer class activation maps; c the initial binary masks of tumor regions; d the refined results using the conditional random field algorithm; e the bounding box delineation

Discussion

In this work, we investigated a weakly supervised learning approach to detect the exact location of breast lesions using only datasets with image-level labels. The proposed model combined FPN, CBAM, and Layer-CAM to improve classification performance and accurately locate feature representations. In addition, we compared the different localization capabilities of three high-level feature extractors (P2–P4) using various CAM algorithms. Quantitative results in Table 4 demonstrated that the best detection performance could be obtained by Layer-CAM in P3. Finally, the fully connected CRF was leveraged to adjust the initial binary masks of tumor regions. The AP for lesion detection significantly improved to 84.1%.

Currently, the computer-aided DCE-MRI breast lesion detection based on deep learning has always been a research hot topic. These related studies can be categorized into tumor location based on region proposals [13, 14, 33], detection using fully convolutional networks (FCN) [34–36], and locating lesions on weakly supervised learning [16–18]. For example, Jiao et al. [13] employed DCE-MRI series segmented by U-Net + + to perform automatic breast tumor detection with supervised learning of Faster R-CNN [22, 37], which consisted of three main components, i.e., (1) representative feature extraction using ResNet101; (2) candidate region generation to predict possible lesion locations; and (3) obtaining the coordinates and probabilities of masses. The average detection sensitivity achieved 0.874 with 3.4 false positives per case on a small private dataset containing only 75 patients. However, this algorithm repeated iterative calculations to generate candidate proposals at a considerably low speed, which failed to achieve real-time detection in clinical practice. The work of Adachi et al. [14] was the first report to accomplish breast cancer detection and diagnosis tasks based on RetinaNet [38], where the application of FPN and focal loss facilitated RetinaNet to draw more attention to hard images, which greatly improved the overall detection performance in terms of sensitivity (0.926) and specificity (0.828). Another supervised learning strategy based on FCN was to detect the whole region in the original DCE-MRI images [35]. Multiple typical FCN structures, termed U-Net, were designed to realize coarse-to-fine segmentation and localization of breast masses by mask-guided hierarchical learning. Compared to the single network, those confounding pixels were gradually discarded via the multi-stage framework, which effectively reduced false positives with sensitivity of 0.750 and dice similarity coefficient (DSC) of 0.718. Similarly, a 3D U-Net was optimized for fully automatic breast malignancy segmentation via a sufficiently large-scale dataset with multiple MRI series [39]. A test DSC of 0.77 demonstrated the outstanding segmentation performance of the network, which was comparable to that of the radiologists (DSC: 0.69–0.84). In order to reduce the dependence on pixel-level labels annotated by professional radiologists, a 3D weakly supervised approach was introduced for the joint task of breast malignancy discrimination and localization [18]. The approximate position of tumors was clearly optimized by the dense CRF on a testing set of 36 cases (DSC of 0.501 and classification specificity of 0.693). Nevertheless, performing thorough comparison experiments between our scheme and state-of-the-art detection methods is full of challenges due to the lack of large public imaging databases. Therefore, from the perspective of rough evaluation, we can observe that the VGG16-guided weakly supervised learning strategy achieves the highest specificity of 0.992 and AP of 0.841, which verifies its outstanding ability to accurately detect tumors. As a preliminary screening tool, our work may help radiologists improve sensitivity and reduce misdiagnosis of breast lesions.

However, some limitations in this study should be mentioned. First, only 2D DCE-MRI slices served as inputs of our model, and 3D structural information was discarded. Second, the presence of obvious imaging artifacts might lead to bias in lesion classification and localization using the weakly supervised strategy. In addition, in most cases of multiple ipsilateral breast lesions, only tumors larger than 5 mm in diameter were enrolled in the experimental dataset. Therefore, improving the detection ability of minimal tumors is one of our research directions in the future.

Conclusion

This study developed a weakly supervised deep learning approach for breast lesion detection in DCE-MRI, which was trained only using image-level labels. It exhibited great potential and application value to assist radiologists in breast cancer diagnosis and provided a reference for practical computer-aided breast lesion detection methods in subsequent researches.

Abbreviations

- Acc

Accuracy

- AP

Average precision

- AUC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- CADe

Computer-aided detection

- CAM

Class activation mapping

- CBAM

Convolutional block attention module

- CNNs

Convolutional neural networks

- CRF

Conditional random field

- DCE-MRI

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI

- FCN

Fully convolutional network

- FPN

Feature pyramid network

- GFLOPs

Giga floating point of operations

- GMP

Global max pooling

- Layer-CAM

Layer class activation mapping

- ROC

The receiver operating characteristic curve

- Sen

Sensitivity

- Spec

Specificity

Funding

This study has received funding by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81830052), the Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan of Shanghai (Grant No. 18441900500), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (Grant No. 20ZR1438300), and the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Molecular Imaging (Grant No. 18DZ2260400).

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Design and implementation of this retrospective research were approved by the Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. The requirement for written informed consent was waived.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rong Sun and Chuanling Wei contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yuanzhong Xie, Email: xie01088@126.com.

Shengdong Nie, Email: nsd4647@163.com.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca-a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan HP, Samala RK, Hadjiiski LM: CAD and AI for breast cancer-recent development and challenges. Br J Radiol 93(1108), 2020 10.1259/bjr.20190580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Zhang Y, Chen J-H, Lin Y, Chan S, Zhou J, Chow D, Chang P, Kwong T, Yeh D-C, Wang X, Parajuli R, Mehta RS, Wang M, Su M-Y. Prediction of breast cancer molecular subtypes on DCE-MRI using convolutional neural network with transfer learning between two centers. Eur Radiol. 2020;31(4):2559–2567. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07274-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Z, Albadawy E, Saha A, Zhang J, Harowicz MR, Mazurowski MA. Deep learning for identifying radiogenomic associations in breast cancer. Comput Biol Med. 2019;109:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2019.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ha R, Mutasa S, Karcich J, Gupta N, Van Sant EP, Nemer J, Sun M, Chang P, Liu MZ, Jambawalikar S. Predicting breast cancer molecular subtype with MRI dataset utilizing convolutional neural network algorithm. J Digit Imaging. 2019;32(2):276–282. doi: 10.1007/s10278-019-00179-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park H, Lim Y, Ko ES, Cho HH, Lee JE, Han BK, Ko EY, Choi JS, Park KW. Radiomics signature on magnetic resonance imaging: association with disease-free survival in patients with invasive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(19):4705–4714. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-3783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H, Zhu YT, Burnside ES, Drukker K, Hoadley KA, Fan C, Conzen SD, Whitman GJ, Sutton EJ, Net JM, Ganott M, Huang E, Morris EA, Perou CM, Ji Y, Giger ML. MR imaging radiomics signatures for predicting the risk of breast cancer recurrence as given by research versions of MammaPrint, Oncotype DX, and PAM50 gene assays. Radiology. 2016;281(2):382–391. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang SY, Franc BL, Harnish RJ, Liu GB, Mitra D, Copeland TP, Arasu VA, Kornak J, Jones EF, Behr SC, Hylton NM, Price ER, Esserman L, Seo Y: Exploration of PET and MRI radiomic features for decoding breast cancer phenotypes and prognosis. Npj Breast Cancer 4, 2018 10.1038/s41523-018-0078-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Drukker K, Li H, Antropova N, Edwards A, Papaioannou J, Giger ML: Most-enhancing tumor volume by MRI radiomics predicts recurrence-free survival "early on" in neoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer. Cancer Imaging 18, 2018 10.1186/s40644-018-0145-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Aghaei F, Tan M, Zheng B: Automated detection of breast tumor in MRI and comparison of kinetic features for assessing tumor response to chemotherapy. Computer-Aided Diagnosis (CAD) Conference at the SPIE Medical Imaging Symposium. Proceedings of SPIE. Orlando, FL; 941429, 2015. 10.1117/12.2081616

- 11.Vignati A, Giannini V, De Luca M, Morra L, Persano D, Carbonaro LA, Bertotto I, Martincich L, Regge D, Bert A, Sardanelli F. Performance of a fully automatic lesion detection system for breast DCE-MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34(6):1341–1351. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrivastava N, Bharti J. Breast tumor detection and classification based on density. Multimedia Tools and Applications. 2020;79(35–36):26467–26487. doi: 10.1007/s11042-020-09220-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiao H, Jiang XH, Pang ZY, Lin XF, Huang YH, Li L: Deep convolutional neural networks-based automatic breast segmentation and mass detection in DCE-MRI. Comput Math Methods Med 2413706, 2020. 10.1155/2020/2413706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Adachi M, Fujioka T, Mori M, Kubota K, Kikuchi Y, Wu XT, Oyama J, Kimura K, Oda G, Nakagawa T, Uetake H, Tateishi U. Detection and diagnosis of breast cancer using artificial intelligence based assessment of maximum intensity projection dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance images. Diagnostics. 2020;10(5):330. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10050330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amit G, Hadad O, Alpert S, Tlusty T, Gur Y, Ben-Ari R, Hashoul S: Hybrid mass detection in breast MRI combining unsupervised saliency analysis and deep learning. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2017 20th International Conference Proceedings: LNCS 10435: 594–602, 2017 10.1007/978-3-319-66179-7_68

- 16.Maicas G, Snaauw G, Bradley AP, Reid I, Carneiro G: Model agnostic saliency for weakly supervised lesion detection from breast DCE-MRI. 16th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging. Venice, ITALY; p. 1057–1060, 2019 10.1109/ISBI.2019.8759402

- 17.Sangheum H, Hyo-Eun K: Self-transfer learning for weakly supervised lesion localization. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) p. 239–246, 2016 10.1007/978-3-319-46723-8_28

- 18.Zhou J, Luo L-Y, Dou Q, Chen H, Chen C, Li G-J, Jiang Z-F, Heng P-A. Weakly supervised 3D deep learning for breast cancer classification and localization of the lesions in MR images. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50(4):1144–1151. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou B, Khosla A, Lapedriza A, Oliva A, Torralba A: Learning deep features for discriminative localization. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Seattle, WA; p. 2921–2929, 2016 10.1109/cvpr.2016.319

- 20.Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition[C]// International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). p. 1–14, 2015. https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1556

- 21.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) p. 770–778, 2016. 10.48550/arXiv.1512.03385

- 22.Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–1149. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marrone S, Piantadosi G, Fusco R, Petrillo A, Sansone M, Sansone C. An investigation of deep learning for lesions malignancy classification in breast DCE-MRI. 19th International Conference on Image Analysis and Processing (ICIAP). Volume 10485, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Catania, ITALY; p. 479–489, 2017. 10.1007/978-3-319-68548-9_44

- 24.Sun R, Zhang X, Xie Y, Nie S. Weakly supervised breast lesion detection in DCE-MRI using self-transfer learning. Med Phys, 2023, Early Access. 10.1002/mp.16296 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Lin TY, Dollar P, Girshick R, He KM, Hariharan B, Belongie S: Feature pyramid networks for object detection. 30th IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Honolulu, HI; p. 936–944, 2017 10.1109/cvpr.2017.106

- 26.Woo SH, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS: CBAM: Convolutional block attention module. 15th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV). Volume 11211, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Munich, GERMANY; p. 3–19, 2018 10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1

- 27.Jiang PT, Zhang CB, Hou QB, Cheng MM, Wei YC. LayerCAM: Exploring hierarchical class activation maps for localization. Ieee Transactions on Image Processing. 2021;30:5875–5888. doi: 10.1109/tip.2021.3089943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krähenbühl P, Koltun V: Efficient inference in fully connected CRFs with gaussian edge potentials. Neural Information Processing Systems, 2011. 10.48550/arXiv.1210.5644

- 29.Obuchowski NA. Receiver operating characteristic curves and their use in radiology. Radiology. 2003;229(1):3–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291010898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chattopadhay A, Sarkar A, Howlader P, Balasubramanian VN: Grad-CAM plus plus : Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. 18th IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision. Nv, p. 839–847, 2018. 10.1109/wacv.2018.00097

- 31.Wang HF, Wang ZF, Du MN, Yang F, Zhang ZJ, Ding SR, Mardziel P, Hu X: Score-CAM: score-weighted visual explanations for convolutional neural networks. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops. Electr Network; p. 111–119, 2020. 10.1109/cvprw50498.2020.00020

- 32.Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, Vedantam R, Parikh D, Batra D. Grad-CAM: visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. International Journal of Computer Vision. 2020;128(2):336–359. doi: 10.1007/s11263-019-01228-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayatollahi F, Shokouhi SB, Mann RM, Teuwen J. Automatic breast lesion detection in ultrafast DCE-MRI using deep learning. Med Phys. 2021;48(10):5897–5907. doi: 10.1117/12.2081616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu WH, Wang Z, He YQ, Yu H, Xiong NX, Wei JG, Ieee. Breast cancer detection based on merging four modes mri using convolutional neural networks. 44th IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), International Conference on Acoustics Speech and Signal Processing ICASSP. Brighton, ENGLAND; p. 1035–1039, 2019. 10.1109/ICASSP.2019.8683149

- 35.Zhang J, Saha A, Zhu Z, Mazurowski MA. Hierarchical convolutional neural networks for segmentation of breast tumors in mri with application to radiogenomics. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2019;38(2):435–447. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2018.2865671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El Adoui M, Mahmoudi SA, Larhmam MA, Benjelloun M. MRI breast tumor segmentation using different encoder and decoder CNN architectures. Computers. 2019;8(3):52. doi: 10.3390/computers8030052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Z, Siddiquee MMR, Tajbakhsh N, Liang J. UNet plus plus : A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. 4th International Workshop on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis (DLMIA) / 8th International Workshop on Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support (ML-CDS). Volume 11045, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Granada, SPAIN; p. 3–11, 2018. 10.1007/978-3-030-00889-5_1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Lin T-Y, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollar P. Focal loss for dense object detection. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence. 2020;42(2):318–327. doi: 10.1109/tpami.2018.2858826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirsch L, Huang Y, Luo SJ, Saccarelli CR, Lo Gullo R, Naranjo ID, Bitencourt AGV, Onishi N, Ko ES, Leithner D, Avendano D, Eskreis-Winkler S, Hughes M, Martinez DF, Pinker K, Juluru K, El-Rowmeim AE, Elnajjar P, Morris EA, Makse HA, Parra LC, Sutton EJ. Radiologist-level Performance by Using Deep Learning for Segmentation of Breast Cancers on MRI Scans. Radiol Artif Intell 4(1): e200231, 2022. 10.1148/ryai.200231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.