Abstract

Background

25-Hydroxyvitamin D testing is increasing despite national guidelines and Choosing Wisely recommendations against routine screening. Overuse can lead to misdiagnosis and unnecessary downstream testing and treatment. Repeat testing within 3 months is a unique area of overuse.

Objective

To reduce 25-hydroxyvitamin D testing in a large safety net system comprising 11 hospitals and 70 ambulatory centers.

Design

This was a quality improvement initiative with a quasi-experimental interrupted time series design with segmented regression.

Participants

All patients in the inpatient and outpatient settings with at least one order for 25-hydroxyvitamin D were included in the analysis.

Interventions

An electronic health record clinical decision support tool was designed for inpatient and outpatient orders and involved two components: a mandatory prompt requiring appropriate indications and a best practice advisory (BPA) focused on repeat testing within 3 months.

Main Measures

The pre-intervention period (6/17/2020–6/13/2021) was compared to the post-intervention period (6/14/2021–8/28/2022) for total 25-hydroxyvitamin D testing, as well as 3-month repeat testing. Hospital and clinic variation in testing was assessed. Additionally, best practice advisory action rates were analyzed, separated by clinician type and specialty.

Key Results

There were 44% and 46% reductions in inpatient and outpatient orders, respectively (p < 0.001). Inpatient and outpatient 3-month repeat testing decreased by 61% and 48%, respectively (p < 0.001). The best practice advisory true accept rate was 13%.

Conclusion

This initiative successfully reduced 25-hydroxyvitamin D testing through the use of mandatory appropriate indications and a best practice advisory focusing on a unique area of overuse: the repeat testing within a 3-month interval. There was wide variation among hospitals and clinics and variation among clinician types and specialties regarding actions to the best practice advisory.

KEY WORDS: vitamin D, overutilization, quality improvement, value-based care, choosing wisely

INTRODUCTION

Testing for 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), the common clinical marker of vitamin D status, has increased in recent years despite recommendations against routine testing by multiple national guidelines and the Choosing Wisely Initiative.1–6 This may be due in part to increased media attention as well as increased reports of the association of vitamin D deficiency with various health conditions.7–9

Screening is only recommended in specific patient populations, including patients with calcium disorders, gastrointestinal malabsorption, osteoporosis, and those taking certain medications, such as steroids, antiepileptics, and antiretroviral medications.

Also, there is a lack of consensus on what serum 25(OH)D level represents deficiency and insufficiency, creating a gray area where inappropriate screening can result in a delay in appropriate treatment, overdiagnosis, and unnecessary downstream cascades, including additional laboratory tests and imaging studies.10

Most published models on reducing the overuse of 25(OH)D testing employ multifaceted interventions or stewardship, which can be resource intensive.11–15 Electronic health record (EHR) interventions with clinical decision support can achieve sustained reductions for 25(OH)D testing and may be easier to implement, particularly at a large scale.16 However, these EHR interventions often focus on best practice advisories (BPAs) for all routine ordering.16 Although effective, this untailored approach can lead to unnecessary alert fatigue.

Past efforts targeted inappropriate screening and not the timing of repeat testing. Guidelines recommend not retesting until at least 3 months after treatment initiation, as earlier testing is unlikely to show a clinically significant change.17–20

Despite these recommendations, up to 20% of repeat tests are performed in less than 3 months.18 We aimed to implement an EHR intervention to reduce both inappropriate 25(OH)D screening and repeat testing in a large safety-net system that serves all patients regardless of their insurance coverage, ability to pay, or immigration status.21

METHODS

Setting

This quality improvement initiative was implemented by the System High Value Care Council at New York City Health + Hospitals (NYC H + H), a safety net system with 11 hospitals and 70 ambulatory centers. Key stakeholders were involved in the project including subject matter experts from internal medicine, laboratory, endocrine, and patient safety. Our project was deemed a quality improvement project by the NYC H + H Central Research Office, and thus an Institutional Review Board submission was not required.

Intervention

An EHR clinical decision support tool was designed for adult inpatient and outpatient orders and involved two components: a mandatory prompt with appropriate indications and a best practice advisory.

Mandatory Indications

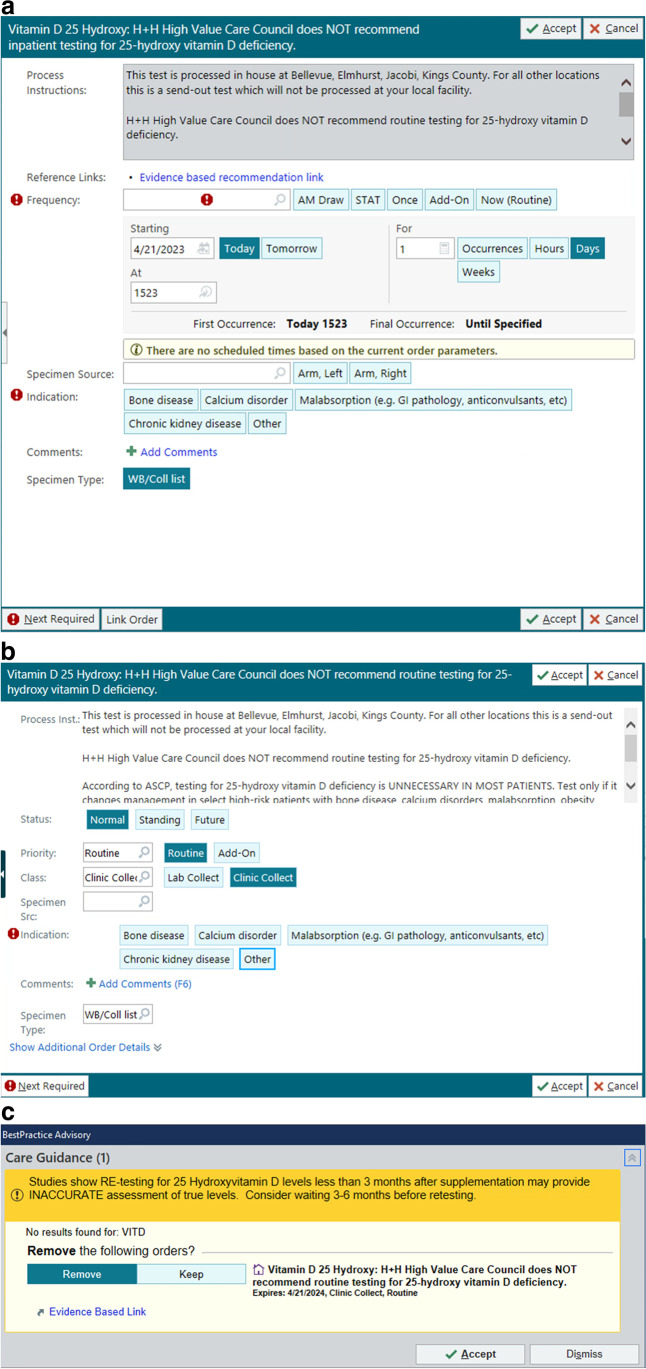

This arm of the intervention included an advisory statement within the order title (Fig. 1a, b), which outlines a recommendation by the System High Value Care Council. Additional information was placed in the process instructions within the order, along with evidence linked to guidelines. We also included an in-line prompt, which requires an appropriate indication for 25(OH)D testing before completing the order. If the user selected “other,” they were required to document the reason for testing. There are different indications for the inpatient and outpatient setting, which was reflected in the options for the mandatory indication on the order. Messaging for the inpatient order stressed that testing for vitamin D deficiency was unnecessary in most patients and should be deferred to the outpatient setting, except for the listed indications (Fig. 1a). The messaging for the outpatient reiterated that 25(OH)D routine testing is unnecessary except for high-risk patients where testing could change clinical management (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

a Inpatient 25(OH)D order modifications with mandatory field for indications. b Outpatient 25(OH)D order modifications with mandatory field for indications. c Best practice advisory for repeat 25(OH)D testing within three months.

Best Practice Advisory

A BPA was created to address retesting in the inpatient and outpatient setting. The alert fires if an order is placed for 25(OH)D level testing in less than 3 months of a previously resulted test. The BPA includes all available results from the previous 3 months and advises the ordering clinician that testing before a 3-month period may be inaccurate and is unlikely to change clinical management. The action element of the BPA defaults to cancel the current test order (Fig. 1c). There is also an evidence-based link to guidelines.18

Measures and Statistical Analysis

All patients in the inpatient and outpatient settings with orders for 25(OH)D testing were included. Pre-intervention period (6/17/2020–6/13/2021, 12 months) was compared to the post-intervention (6/14/2021–8/28/2022, 16 months). NYC H + H utilizes Epic (Verona, Wisconsin) as the EHR across all acute care sites and ambulatory clinics. Data were abstracted through SQL queries on the Epic Clarity database and analyzed statistically with version 4.0.3 of the R programming language (R Core Team, 2020).

Age and length of stay (for inpatient testing) were compared pre- and post-intervention to ensure similar patient populations. Additionally, race and ethnicity were compared pre- and post-intervention.

The primary outcomes were the average number of weekly 25(OH)D tests normalized by patient days in the inpatient setting and normalized by patient encounters in the outpatient setting. 25(OH)D testing pre-and post-intervention were also stratified by individual hospitals and the top 10 clinics by patient encounter volume. Because there are more than 70 ambulatory clinics, we chose to report the top 10 clinics. Another primary outcome was the number of 25(OH)D repeats within 3 months pre-and post-intervention.

The pre-intervention weekly averages were compared to post-intervention averages using two methods. The first approach utilized an unpaired t-test with unequal variance to compare the averages. The second approach utilized a quasi-experimental time series regression. Separate regression lines were drawn for the pre and post-intervention periods, capturing temporal trends in ordering rates. The level difference was computed by comparing the pre and post-intervention intercept values at the intervention date to capture an immediate change in ordering rates. A trend difference was computed by comparing the slopes to capture changes in longer term ordering trends. The level difference and trend difference were compared via a multivariate t-test. To aid in visual comparison, counterfactual pre-intervention regression lines were extended into the post-intervention period to show expected post-intervention period ordering rates if the intervention did not happen.

The process measure was the BPA accept rate (retest cancellation rate) for each BPA, defined as the number of BPAs where the 25(OH)D order was removed, divided by the total number of BPAs triggered. The 24-h reorder rate was also tracked, defined as the number of reorders of 25(OH)D within 24 h despite the initial removal of the order through the BPA, divided by the total number of accepted BPAs. The 24-h reorder rate subtracted from the BPA accept rate represents the true accept rate. Additionally, the BPA accept rates were stratified by provider type and specialty. A second process measure to track the appropriateness of ordering was the percentage of selections of the various indications, including other.

RESULTS

The average age was 53.8 years pre-intervention and 55.5 years post-intervention, p < 0.05 (Table 1). The average length of stay for inpatients was 14.2 days pre-intervention and 14.0 days post-intervention, p = 0.61. Hispanic/Latinx patients represented 45.6% of patients pre-intervention and 46.8% of patients post-intervention.

Table 1.

Demographic Table

| Pre (n = 65,550) |

Post (n = 45,674) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic/Latinx | 45.6% | 46.8% | < 0.01 |

| Black or African American | 29.0% | 28.3% | < 0.01 |

| Something else/unknown/choose not to disclose | 11.7% | 10.9% | < 0.01 |

| Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 6.7% | 6.7% | 0.62 |

| White | 6.5% | 6.7% | < 0.01 |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.98 |

| Two or more races | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.08 |

| Average age (years) | 53.8 | 55.5 | < 0.05 |

| Average length of stay (days) | 14.2 | 14.0 | 0.61 |

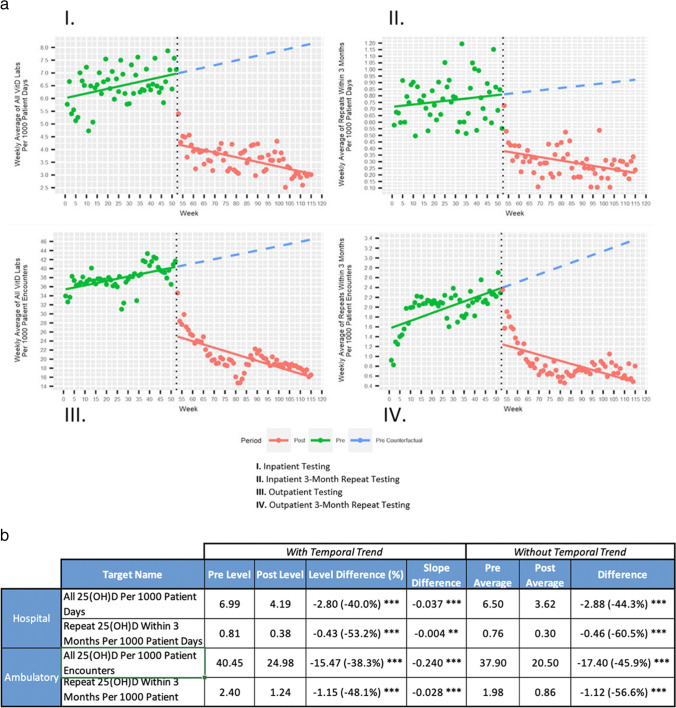

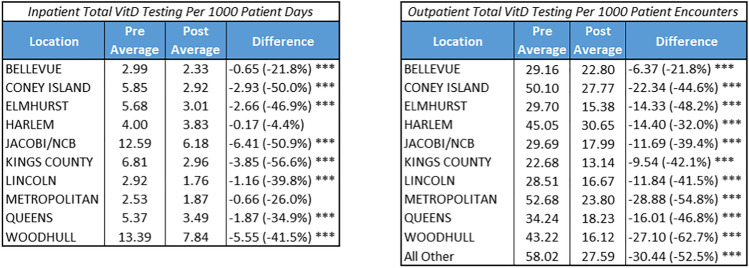

Post-intervention, there was a reduction in 25(OH)D tests performed in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. In the inpatient setting, 25(OH)D testing decreased from 6.50 to 3.62 per 1000 patient days (44.3% reduction, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2a). The level difference was − 2.80 (− 40.0%, p < 0.001) and slope difference was − 0.037 with p < 0.001 (Fig. 2b). In the outpatient setting, 25(OH)D testing decreased from 37.90 to 20.50 per 1000 patient encounters (45.9% reduction, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The level difference was − 15.47 (− 38.3%, p < 0.001) and the slope difference was − 0.24 with p < 0.001. When stratified by hospital, the reductions ranged from 4.4 to 56.6% (Table 1). In the outpatient setting, the reductions in the top 10 clinics by volume ranged from 21.8 to 62.7% (Table 2).

Figure 2.

a Regression analysis pre- vs post-intervention of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) lab testing. b Analysis of pre- vs post-intervention of (25(OH)D) total testing and repeat testing within 3 months for all hospitals and the ten clinics with the highest volume of patient encounters, stratified with a temporal trend (linear regression) and without temporal trend (Welch t test). Difference = Post minus Pre, * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

Table 2.

Variation in Ordering Patterns by Location in the Inpatient and Outpatient Settings

Difference = Post minus Pre, * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001

Of the 25(OH)D inpatient orders, chronic kidney disease comprised 26.1% of the orders, calcium disorder 16.6%, bone disease 10.7%, malabsorption 10.5%, other 34.5%, and multiple selections 1.6%. In the outpatient setting, chronic kidney disease comprised 5.9% of the orders, calcium disorder 8.2%, bone disease 25.8%, malabsorption 8.8%, liver disease 1.4%, other 49.4%, and multiple selections 0.6%. Of the other selections, common similar responses were preoperative, HIV, pregnancy, and history of vitamin D deficiency.

The 3-month inpatient repeat testing for 25(OH)D decreased from 0.76 to 0.30 per 1000 patient days (− 60.5%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The level difference was − 0.43 (− 53.2%, p < 0.001), and slope difference − 0.004 (p < 0.001). The 3-month outpatient repeat testing decreased from 2.40 to 1.24 per 1000 patient encounters (− 48.1%, p < 0.001). The level difference was − 1.15 (− 48.1%, p < 0.001), and slope difference − 0.028 (p < 0.001).

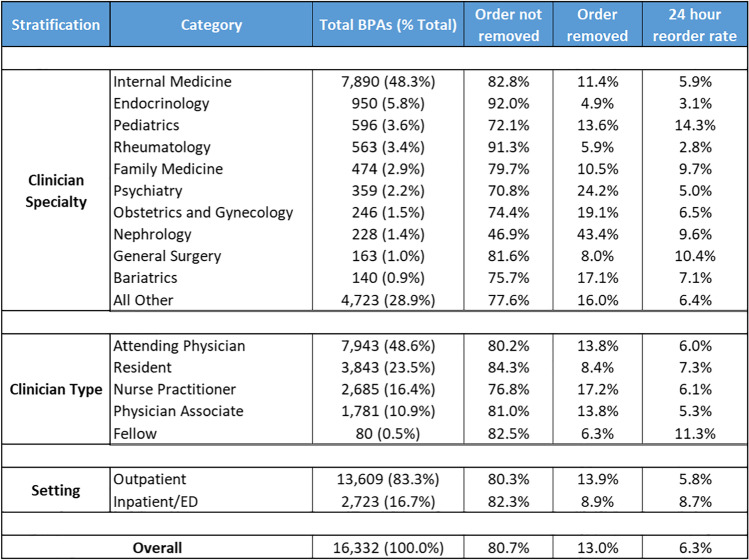

Post-BPA intervention, the accept rate (retest cancellation rate) was 19.3% (3152 of 16,332). The 24-h reorder rate was 6.3%, making the true accept rate 13.0%. The inpatient true accept rate was 8.9% (242 of 2,723) and the outpatient true accept rate was 13.9% (1891 of 13,609).

Among different types of clinicians, nurse practitioners had the highest true accept rate of 17.2%, followed by physician associates and attending physicians both at 13.8%, and residents at 8.4%. Fellows had the lowest true accept rate of 6.3% (Table 2). Among different clinician specialties, nephrology had the highest true accept rate of 43.4% and endocrine had the lowest at 4.9% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Best Practice Advisory Actions, Based on Clinician Specialty, Type, and Setting

DISCUSSION

This initiative successfully reduced 25(OH)D testing by 44–46% across 11 hospitals and 70 ambulatory centers in a safety net setting through the use of mandatory appropriate indications and a best practice advisory. Importantly, we introduced an intervention targeting a unique area of overuse: the repeat testing of 25(OH)D within a 3-month interval.

Our clinical decision support tools take advantage of key principles of nudges, which are defined as “‘any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way.”22 First, it takes a complex decision of appropriate testing and limits the number of choices to a manageable 5–6 options. Limiting options is a well-described nudge that prevents the user from becoming overwhelmed with the number of choices, thus avoiding unintended consequences such as workarounds or inaccurate clicking of an indication. Second, the prompt is preceded by an informational nudge that provides general guidance to the clinician that routine 25(OH)D testing is unnecessary in most patients and advises the appropriate indications for testing. Thirdly, the statement “H + H High Value Care Council recommends…” serves as a normative nudge and places a respected representative group of peers as the source of recommendation and norms.

Intervening on the subset of overuse of repeat testing within 3 months deserves future study. Most prior interventions to reduce 25(OH)D testing focused on general screening for deficiency.11,12,14,15 Our intervention achieved a high percentage of reduction (57–61%) in inpatient and outpatient settings, revealing a new area of opportunity.

The variation in behavior change to the initiative spans wide. This was seen among individual hospitals (− 4 to − 57%) and ambulatory centers (− 22 to − 63%). This wide variation may be a result of differences in high-value care culture within individual hospitals.23,24 The differences in action rates among clinician specialties and types to the BPA showed interesting patterns. Nephrology had a relatively high action rate to the BPA (43%) compared to other specialties. This may be due to reflex processes such as checklists or order panels for patients with renal failure. Endocrine and rheumatology had the lowest action rates (5–6%), which may necessitate a further study into specialty practices regarding the evidence for repeat testing within 3 months. Among clinician types, attending physicians showed higher action rates to residents or fellow physicians, demonstrating a comfort level among attendings to less testing described in previous literature.25 Additionally, nurse practitioners showed the highest acceptance rate to the BPA compared to all groups. This contrasts with previous findings regarding advanced practice providers, and further study may be warranted.25,26

Of note, the overall average action rate of the BPA (13%) was much lower than the reduction of repeat testing within 3 months (57–61%). This may be a result of the requirement of an indication in the 25(OH)D order. Or, this suggests cumulative learning from the BPA, preventing future iterations of this overuse, similar to findings in BPA-related reductions of triiodothyronine (T3) testing.24 This phenomenon of low BPA accept rates but a high reduction in testing has been seen in previous literature.24,27 It is also worth noting that no concurrent interventions supplemented this BPA, such as education or local publicity campaigns.

Limitations exist within this study. First, this study lacks control or randomization. We did use age and length of stay as surrogates to ensure similar patient populations. There was a statistically significant difference in age pre- and post-intervention. Since the number of 25(OH)D tests is very large (over 100,000 per year across both inpatient and outpatient), the large sample size is overpowered to detect small differences in age. Therefore, while the age difference is statistically significant, it is not clinically significant. Second, we did not investigate the appropriateness of testing through chart reviews.

We successfully reduced 25(OH)D testing across a large safety net setting through clinical decision support centered on screening and repeat testing within 3 months. Further study is needed to understand the appropriateness of orders and variation among clinician specialty and type.

Declarations:

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Force UPST. Screening for Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325(14):1436-1442. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911-1930. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.ASCP - Population based screening: Choosing Wisely. https://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-society-clinical-pathology-population-based-screening-for-vitamin-d-deficiency/. Published 2013. Accessed 3 Oct 2022.

- 4.Rockwell M, Kraak V, Hulver M, Epling J. Clinical management of low vitamin D: a scoping review of Physicians’ practices. Nutrients. 2018;10(4):493. 10.3390/nu10040493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Shahangian S, Alspach TD, Astles JR, Yesupriya A, Dettwyler WK. Trends in laboratory test volumes for Medicare Part B reimbursements, 2000-2010. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(2):189-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early Trends Among Seven Recommendations From the Choosing Wisely Campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Rodd C, Sokoro A, Lix LM, et al. Increased rates of 25-hydroxy vitamin D testing: Dissecting a modern epidemic. Clin Biochem. 2018;59:56-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kolata G. Why Are So Many People Popping Vitamin D? . https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/10/health/vitamin-d-deficiency-supplements.html. Updated April 10, 2017. Accessed 25 Jan 2023.

- 9.Vitamin D testing not recommended for most people. Harvard Health Publishing; 2023. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/vitamin-d-testing-recommended-people-201411267547. Published 2014. Updated November 26, 2014. Accessed 23 Jan 2023.

- 10.Rockwell MS, Wu Y, Salamoun M, Hulver MW, Epling JW. Patterns of Clinical Care Subsequent to Nonindicated Vitamin D Testing in Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(4):569-579. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Patel V, Gillies C, Patel P, Davies T, et al. Reducing vitamin D requests in a primary care cohort: a quality improvement study. BJGP Open. 2020;4(5): bjgpopen20X101090. 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Naugler C, Hemmelgarn B, Quan H, et al. Implementation of an intervention to reduce population-based screening for vitamin D deficiency: a cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(1):E36-e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Tai F, Chin-Yee I, Gob A, Bhayana V, Rutledge A. Reducing overutilisation of serum vitamin D testing at a tertiary care centre. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(1): e000929. 10.1136/bmjoq-2020-000929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Petrilli CM, Henderson J, Keedy JM, et al. Reducing Unnecessary Vitamin D Screening in an Academic Health System: What Works and When. Am J Med. 2018;131(12):1444-1448. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ferrari R, Prosser C. Testing Vitamin D Levels and Choosing Wisely. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):1019-1020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Felcher AH, Gold R, Mosen DM, Stoneburner AB. Decrease in unnecessary vitamin D testing using clinical decision support tools: making it harder to do the wrong thing. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(4):776-780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, et al. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 2010;182(17):1864-1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Zhao S, Gardner K, Taylor W, Marks E, Goodson N. Vitamin D assessment in primary care: changing patterns of testing. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2015;7(2):15-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Norton K, Vasikaran SD, Chew GT, Glendenning P. Is vitamin D testing at a tertiary referral hospital consistent with guideline recommendations? Pathology. 2015;47(4):335-340. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Use and Interpretation of Vitamin D testing. https://www.rcpa.edu.au/Library/College-Policies/Position-Statements/Use-and-Interpretation-of-Vitamin-D-Testing. Updated May 2023. Accessed 25 Jan 2023.

- 21.Moura P. What Is a Safety-Net Hospital and Why Is It So Hard to Define?. 2023. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/what-is-a-safety-net-hospital-covid-19/. Published 2021. Accessed 25 Jan 2023.

- 22.Last BS, Buttenheim AM, Timon CE, Mitra N, Beidas RS. Systematic review of clinician-directed nudges in healthcare contexts. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e048801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Gupta R, Moriates C, Harrison JD, et al. Development of a high-value care culture survey: a modified Delphi process and psychometric evaluation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(6):475-483. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Krouss M, Israilov S, Alaiev D, et al. Free the T3: Implementation of best practice advisory to reduce unnecessary orders. Am J Med. 2022;135(12):1437-1442. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Roman BR, Yang A, Masciale J, Korenstein D. Association of Attitudes Regarding Overuse of Inpatient Laboratory Testing With Health Care Provider Type. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1205-1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Hughes DR, Jiang M, Duszak R, Jr. A comparison of diagnostic imaging ordering patterns between advanced practice clinicians and primary care physicians following office-based evaluation and management visits. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):101-107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Shin D, Krouss M, Alaiev D, et al. Reducing unnecessary routine laboratory testing for noncritically ill patients with COVID-19. J Hosp Med. 2022;17(12):961-966. 10.1002/jhm.12993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]