Abstract

Here we present a rare case of life-threatening spontaneous renal haemorrhage following elective vascular surgery. A 73-year-old gentleman presents to the ED with acute onset right sided flank pain, 24 hours post bilateral renal artery stent insertion for renal artery stenosis. Subsequent angiography demonstrated bilateral renal artery stent occlusion with near complete bilateral kidney infarction. The patient urgently underwent bilateral renal artery thrombectomy. Post-operatively the patient developed severe unilateral flank pain and became haemodynamically unstable. Subsequent imaging revealed a large right sided retroperitoneal haematoma with active arterial bleeding. The patient ultimately underwent a right sided trauma nephrectomy for haemorrhage control.

1. Introduction

Acute renal artery occlusion is uncommon but requires rapid diagnosis and early management to prevent permanent renal dysfunction. Here we present a case of spontaneous life-threatening renal haemorrhage following endovascular revascularisation of bilaterally occluded renal artery stents. Spontaneous renal haemorrhage (SRH) is a documented phenomena that is known to occur secondary to malignant and benign renal masses; however to our knowledge, reperfusion of infarcted renal parenchyma leading to spontaneous haemorrhage has not previously been reported. The management of acute renal artery thrombosis can be conservative or surgical in nature. Here we suggest the judicious use of therapeutic anticoagulants in patients with a large percentage of infarcted renal tissue and reinforce the need for diagnostic vigilance in the peri-operative period when patients recovery deviates from their expected clinical course.

2. Case presentation

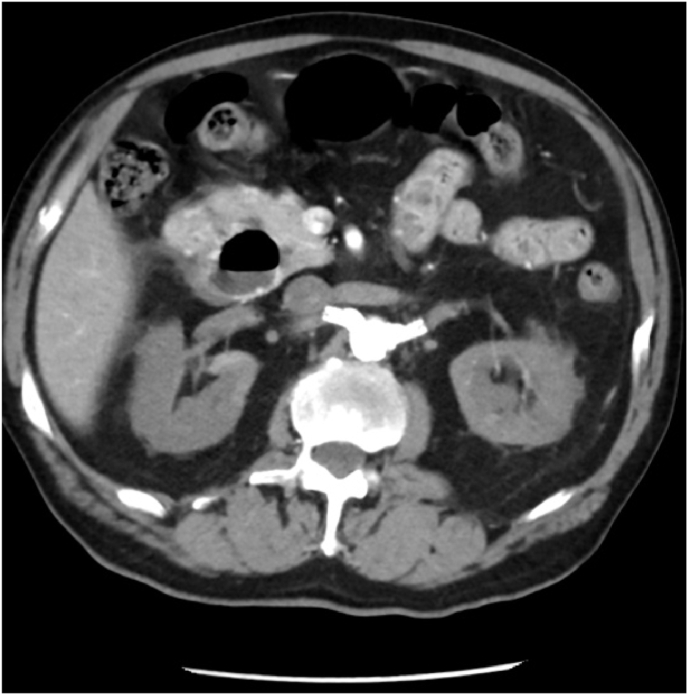

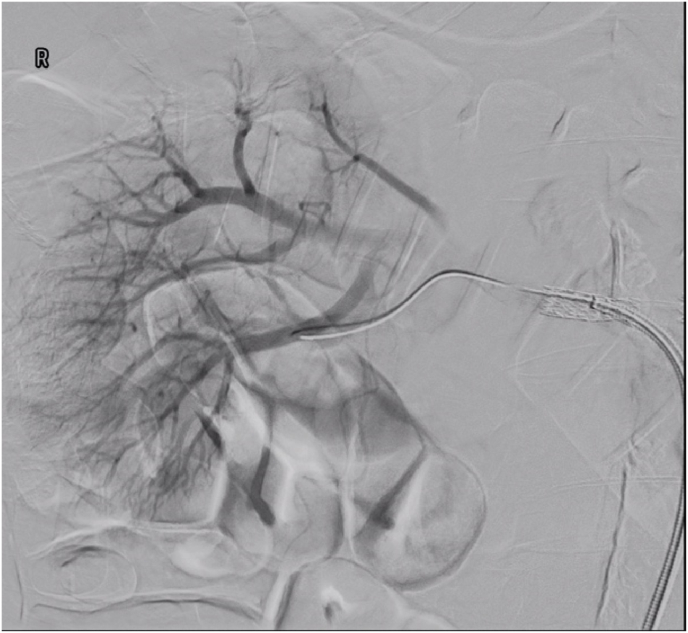

A 73-year-old gentleman presented to the emergency department of a peripheral hospital with acute right sided flank pain, roughly 24 hours post elective bilateral renal artery stent insertion for known renal artery stenosis. This is on a background of peripheral vascular disease, hypertension and ex-smoker status. The patient was investigated with an urgent abdominal CT Angiogram which revealed almost complete occlusion bilaterally of these recently placed renal artery stents (Fig. 1). In the setting of worsening pain, deteriorating renal function and CT evidence of near complete renal infarction bilaterally-the patient was fasted and transferred to a nearby private hospital where he underwent bilateral in-situ renal artery thrombectomy and repositioning of his renal artery stents. On table angiography post bilateral renal artery in-stent thrombectomy revealed patent renal arteries bilaterally without evidence of active bleeding (Fig. 2b, Fig. 2a). There was no immediate intraoperative complications and the patient was returned to the ward for routine post-operative observations. The patient remained on a heparin infusion given his high thrombotic risk.

Fig. 1.

Axial view of a abdominal CT angiogram showing bilateral renal artery occlusion.

Fig. 2b.

Angiography post in stent renal artery thrombectomy showing good renal perfusion to the right kidney without evidence of active bleeding.

Fig. 2a.

Angiography post in stent renal artery thrombectomy showing good renal perfusion bilaterally without evidence of active bleeding.

Shortly after returning to the ward, the patient developed severe right sided flank pain with associated haemodynamic instability. Physical examination revealed a positive Cullen's sign with the patient having a distended right flank which was firm and painful to palpation. Serial haemoglobin checks revealed a steady decline, from a preoperative level of 144 g/L to 88 g/L in 12 hours with an associated decline in renal function with a serum creatinine of 320 from a baseline of 200 without hyperkalaemia. The patient underwent urgent CT angiography which confirmed the diagnosis of large right sided retroperitoneal haematoma with active arterial bleed (Fig. 3). The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for supportive care, where he was transfused with packed red blood cells and required vasopressor support to maintain adequate mean arterial blood pressure. Selective renal artery embolization was unable to be performed as there was no focal area of arterial bleeding.

Fig. 3.

Coronal view of a abdominal CT angiogram showing a large retroperitoneal haematoma with evidence of active arterial bleeding.

Due to progressive worsening in haemodynamic instability-the patient was consented for and underwent an open right sided trauma nephrectomy for uncontrolled retroperitoneal haemorrhage. This procedure was performed via a midline laparotomy. The retroperitoneal haematoma had ruptured into the peritoneal cavity, whereby 2000mls of blood and haematoma were removed. Arterial control was achieved through cross clamping of the right renal artery after mobilising the small bowel and gaining direct access to the infrarenal aorta and renal arteries. Due to the presence of renal artery stents-heavy vascular clamps were required to successfully occlude the renal artery. A modified McCouchie incision was used to complete the nephrectomy.

The patient was returned to the intensive care unit intubated-where he required ongoing supportive management with haemoglobin replacement and blood pressure support. A Hickman line was inserted day 2 post-operatively as the patient developed worsening renal failure requiring renal-replacement therapy. The patient recovered well post-operatively despite his prolonged stay in the intensive care unit for supportive management and dialysis. He was stepped down to a local peripheral hospital where he underwent rehabilitation for his physical deconditioning. The right kidney was sent for histopathological analysis which revealed ischaemic change consistent with ischaemic infarction of the kidney. The patient remains off dialysis, with his renal function having returned to his previous baseline of creatinine 200, eGFR 25.

3. Discussion

Spontaneous renal haemorrhage (SRH) was first described by Bonet in 1700 however was more completely explained by Wunderlich in 1856.1 Common presenting complaints include abdominal/flank pain, visible haematuria and haemodynamic instability.2 Spontaneous retroperitoneal haemorrhage (SRH), termed Wunderlich syndrome is a rare clinical entity caused by renal tumours like Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) or Angiomyolipoma (AML).3 Although renal masses account for approximately 50–70% of the causes for SRH, the prevalence as complication of these masses remains low and is more commonly seen in larger AMLs.3 To our knowledge, SRH following revascularisation of an infarcted kidney as not been previously reported.

Acute renal artery occlusion is uncommon, however can occur as a result of thromboembolic occlusion of the main renal artery, renal artery dissection and renal artery stent occlusion.4 Although it is agreed that early diagnosis and revascularisation of the affected kidney may reduce ischaemic injury and subsequent long term renal dysfunction; there is a lack of evidence to support a specific management with either therapeutic anticoagulation, thrombolysis or surgical methods of revascularisation.5 A review by Silverberg et al., 2016 performed a retrospective study comparing conservative vs surgical intervention for acute renal artery occlusion. The majority of cases were managed conservatively with a subset of patient undergoing endovascular intervention with comparable complication rate and short to medium term results (as measured by return of renal function).4

4. Conclusion

Acute renal artery occlusion is uncommon but requires rapid diagnosis and early management to prevent permanent renal dysfunction. Here we present a case of spontaneous life-threatening renal haemorrhage following endovascular revascularisation of bilaterally occluded renal artery stents-to our knowledge this has not previously been reported. We believe that ischaemic time and subsequent volume of infarcted renal parenchyma reflects the risk of spontaneous haemorrhage following revascularisation. The management of acute renal artery thrombosis can be conservative or surgical in nature however in these high-risk patients, the use of therapeutic anticoagulants should be used judiciously. Here we re-enforce the need for close clinical monitoring and diagnostic vigilance in the peri-operative period when patients recovery deviates from their expected clinical course.

References

- 1.Polkey H.J., Vynalek W.J. Spontaneous nontraumatic perirenal and renal hematomas: an experimental and clinical study. Arch Surg. 1933 Feb 1;26(2):196–218. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgentaler A., Belville J.S., Tumeh S.S., Richie J.P., Loughlin K.R. Rational approach to evaluation and management of spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990 Feb 1;170(2):121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips C.K., Lepor H. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage caused by segmental arterial mediolysis. Rev Urol. 2006;8(1):36–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverberg D., Menes T., Rimon U., Salomon O., Halak M. Acute renal artery occlusion: presentation, treatment, and outcome. J Vasc Surg. 2016 Oct 1;64(4):1026–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blum U., Billmann P., Krause T., et al. Effect of local low-dose thrombolysis on clinical outcome in acute embolic renal artery occlusion. Radiology. 1993 Nov;189(2):549–554. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.2.8210388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]