Abstract

Background

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is often regarded as a progressive, lifelong disease requiring an increasing number of drugs. Sustained remission of T2D is now well established, but is not yet routinely practised. Norwood surgery has used a low-carbohydrate programme aiming to achieve remission since 2013.

Methods

Advice on a lower carbohydrate diet and weight loss was offered routinely to people with T2D between 2013 and 2021, in a suburban practice with 9800 patients. Conventional ‘one-to-one’ GP consultations were used, supplemented by group consultations and personal phone calls as necessary. Those interested in participating were computer coded for ongoing audit to compare ‘baseline’ with ‘latest follow-up’ for relevant parameters.

Results

The cohort who chose the low-carbohydrate approach (n=186) equalled 39% of the practice T2D register. After an average of 33 months median (IQR) weight fell from 97 (84–109) to 86 (76–99) kg, giving a mean (SD) weight loss of −10 (8.9)kg. Median (IQR) HbA1c fell from 63 (54–80) to 46 (42–53) mmol/mol. Remission of diabetes was achieved in 77% with T2D duration less than 1 year, falling to 20% for duration greater than 15 years. Overall, remission was achieved in 51% of the cohort. Mean LDL cholesterol decreased by 0.5 mmol/L, mean triglyceride by 0.9 mmol/L and mean systolic blood pressure by 12 mm Hg. There were major prescribing savings; average Norwood surgery spend was £4.94 per patient per year on drugs for diabetes compared with £11.30 for local practices. In the year ending January 2022, Norwood surgery spent £68 353 per year less than the area average.

Conclusions

A practical primary care-based method to achieve remission of T2D is described. A low-carbohydrate diet-based approach was able to achieve major weight loss with substantial health and financial benefit. It resulted in 20% of the entire practice T2D population achieving remission. It appears that T2D duration <1 year represents an important window of opportunity for achieving drug-free remission of diabetes. The approach can also give hope to those with poorly controlled T2D who may not achieve remission, this group had the greatest improvements in diabetic control as represented by HbA1c.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Metabolic syndrome, Nutritional treatment, Weight management, Blood pressure lowering

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The idea of drug-free remission of type 2 diabetes (T2D) gives hope to many and can be achieved in different ways.

Sugary and starchy foods worsen blood glucose control so a low-carbohydrate diet is a logical first step.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Advice and ongoing guidance on a low-carbohydrate diet in primary care can achieve improved diabetic control for 97% of those interested in the approach, sustained for an average of 33 months.

Those patients who started with ‘younger’ diabetes and lower HbA1c were far more likely to achieve remission.

Those in the non-remission, ‘mitigation’ group achieved unexpectedly greater, clinically important improvements in diabetic control with the diet

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Seventy-seven per cent of those adopting a low-carbohydrate approach in the first year of their T2D achieved remission. This represents an important ‘window of opportunity’ for further investigation.

People with established long-term T2D, which may be poorly controlled could benefit from looking carefully at reducing sugar and starchy carbohydrates.

Introduction

In 2021, the British Dietetic Association published a review of dietary strategies for drug-free remission of type 2 diabetes (T2D),1 which stated that ‘total dietary replacements and low-carbohydrate diets have been demonstrated as being effective in facilitating weight loss and remission of T2D’. However, metanalyses do not always support a focus on low-carbohydrate diets to achieve either weight loss or remission of diabetes.2 3 There is a need for hard data on outcomes of such an approach and to examine what clinical aspects help it succeed.

In this paper, we examine real-world data from a cohort based in a UK primary care clinic offering a low-carbohydrate approach to people with T2D from 2013 to 2021. The physiological mechanisms behind remission induced by dietary weight loss were first demonstrated in 2011.4 Since then the idea of drug-free T2D remission has gained international momentum.4–7 We now have an international consensus on the definition of remission; a glycated heamoglobin(HbA1c) <48 mmol/mol sustained for >3 months in the absence of diabetes medication.8 Earlier practice audits showed significant improvements in: HbA1c,9 10 lipids and blood pressure (BP) (this despite ‘deprescribing’ 20% of antihypertensive drugs),11 renal function12 and liver function.13 Not only were major health improvements demonstrated but also substantial drug-budget savings.10

This analysis of our 8-year dataset explores which factors predict remission, its durability and the glycaemic control of those not achieving remission.

Methods

Advice on lowering dietary carbohydrate was offered routinely by our team of nine specially trained GPs and three practice nurses to patients with T2D (defined as HbA1c >48 mmol/mol on two occasions) starting in March 2013 (online supplemental file 1, low-carbohydrate protocol). Our protocol includes important information around the deprescribing of both drugs for BP and T2D; both BP and blood glucose were often found to improve to an extent requiring a medication review.11 Checking and discussing body weight was the first step in every consultation, then the low-carbohydrate diet was offered as an option alongside clear and simplified explanations of key physiological principles emphasising: that good diabetic control is about avoiding the damage caused by blood sugars spikes, that ‘time in range’ matters,14 a high blood sugar is often a reflection of foods eaten recently, glucose and insulin levels change in response to different foods, starchy carbohydrates comprise many glucose molecules causing significant blood sugar elevation and how weight loss was part of the process. (online supplemental file 2).

bmjnph-2022-000544supp001.pdf (1MB, pdf)

We view high blood sugars as an interesting puzzle rather than a problem, one to be explored collaboratively with the patient. In cases where weight or HbA1c began to climb after an initial improvement we observed early on that most patients had actually increased their carbohydrate consumption (carb creep). Often a quick telephone call would motivate change.

Many of our less experienced clinicians worried that talking about obesity could be considered ‘fat shaming.’ We encouraged them to explain that weight loss could really help peoples’ health and to ask if they were interested to work collaboratively to achieve this. In this way, we supplied relevant information and then checked if the person wanted to go ahead before giving more specific advice.

For those who opted for the lower carbohydrate programme, baseline weight and blood results were ascertained alongside dietary advice as part of routine GP or practice nurse consultations. Weight was measured at each visit, the level of ongoing support was tailored to patient choice and clinical need. In addition to 10 min ‘one-to-one’ appointments (we estimate an average of three consultations per patient, per year) the practice offered optional 90 min evening group sessions, approximately every 6 weeks. Group sessions included relatives who were encouraged to attend as some patients relied on others for food shopping or cooking. Group sessions provided a forum for people to offer practical support to others and training new staff. On average 25 patients attended each session. From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, these group sessions were hosted as online Zoom meetings. This enabled us to send a link to these meetings inviting every person in the practice with T2D. This was particularly important for patients wanting a ‘refresher’.

Educational resources were produced to support patients and staff. The low-carbohydrate diet sheet (online supplemental file 3) outlines suitable sources of food. Glycaemic load data were also presented to encourage a reduced intake of sugary and starchy foods. For example, replacing breakfast cereals, rice, bread and potatoes with, full-fat dairy, eggs, green leafy vegetables, meat, fish, berries and nuts (with sensitivity to each patient’s sociocultural dietary needs and preferences). From 2018, staff training was formalised through completion of a Royal College of General Practitioners e-learning module on T2D and the glycaemic index, written by one of the authors.15

This paper forms part of an ongoing audit of service provision. An iterative process necessitating regular updates of the protocol and practice-wide sharing of ‘what works’ based on audits like this. As a result, our methods have improved since 2013. The tendency for results to deteriorate after initial promise led to us focusing on effective maintenance of dietary change. We suggested people look ahead to the challenges of holidays, Christmas and birthdays, times when so many diets fail. We encouraged patients to look out for weight gain at these times and take action. Computer generated graphs of all metrics measured were sent out as patient feedback (the reception staff call this ‘The happy post’). Around 2016, we became aware of another possible behavioural factor causing our patients to regain weight: ‘food addiction’.16 In response, we supported people to identify and completely avoid their ‘trigger foods’.

Further behaviour changes were enabled by encouraging participants to consider their individual hopes and health goals, the resources available to them, setting realistic next steps and enabling the individual to notice what works for them (online supplemental file 4).17 We would highlight the power that the hope of drug-free remission brings to people with T2D. This model was key to maintaining the motivation of our clinical team and helping it evolve. Finally, in terms of behaviour change we learnt to ask how people learn best: Did they prefer a leaflet, book or App?

Exclusion criteria were severe mental illness, terminal illness and eating disorders

Routine clinical data were collected from March 2013 to April 2021. Baseline measurements of weight and BP were made at the surgery and blood tests (HbA1c, lipid profiles) by the local NHS phlebotomy clinic. Frequency of blood tests depended on clinical need and risk assessment as part of standard care. Some patients found it challenging to fit fasting blood tests into their lifestyle patterns, so our results include a greater number of incomplete data sets for lipid profiles than other measures.

Statistical analyses were performed with R V.4.0.2. Summaries of baseline and follow-up data are shown as median and the IQR (IQR, 25th percentile, 75th percentile) for non-normally distributed continuous variables like age, weight, HbA1c, lipid profile and BP. More normally distributed continuous variables like duration of diet are presented as mean (SD). Comparisons between baseline and latest follow-up continuous variables were made using the Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired samples. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Baseline and latest follow-up distributions of data are presented as box and whisker plots, the box represents the median value and the IQR, the red dot indicates the mean value and the upper and lower whiskers indicate either, the minimum/maximum value, or 1.5 times the IQR.

Linear regression models were fitted with HbA1c reduction as the outcome and baseline HbA1c as the predictor. Logistic regression models were fitted with remission occurrence as the outcome and gender, baseline age, baseline weight, baseline HbA1c and duration of T2D as predictors.

Results

By the end of the 8-year period (March 2013–April 2021), Norwood surgery had a T2D disease register of 473 people, of whom 186 (39%) chose the low- carbohydrate approach. Of these, 114 (61%) were male, and the median (IQR) age at baseline was 63 (54, 73) years. Mean (SD) duration of follow-up was 33 (27) months. 37.6% of the cohort were people within 1 year of diagnosis.

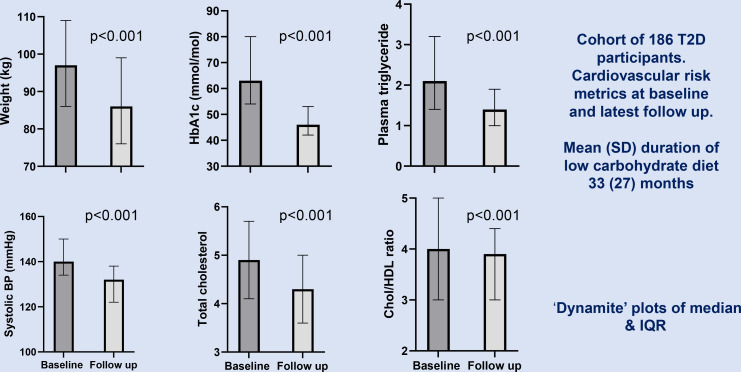

For the whole cohort commenced on the low-carbohydrate programme median (IQR) weight fell from 97 (84–109) to 86 (76–99) kg, giving a mean(SD) weight loss of −10 (8.9)kg; p<0.001. Median (IQR) HbA1c dropped from 63 (54–80) to 46(42–53) mmol/mol; p<0.001. The median (IQR) triglyceride dropped from 2.1 (1.4–3.2) to 1.4 (1.0–1.9)mmol/L; p<0.001. The median (IQR) systolic BP dropped from 140 (134–150) to 132 (122–138) mm Hg; p<0.001. The median (IQR) total cholesterol decreased from 4.9 (4.1–5.7) to 4.3 (3.6–5.0) mmol/L;p<0.001. The median (IQR) total cholesterol to High-Density Lipoprotein(HDL) ratio decreased from 4.0 (3.0–5.0) to 3.9 (3.0–4.4); p<0.001 (table 1, figure 1 and online supplemental file 5).

Table 1.

Comparing baseline and latest follow-up data for 186 patients with T2D advised on a low-carbohydrate diet, with breakdown into two subgroups; 94 patients who achieved remission and 92 patients who did not

| Baseline measure median (IQR) | Latest follow-up median (IQR) | Difference Mean (SD) |

P value | Matched pairs n (%) |

|

| 1. Cohort of 186 T2D participants who chose a low-carbohydrate diet mean (SD) duration of diet: 33 (27) months mean (SD) time from diagnosis to diet start: 64 (69) months | |||||

| Age (years) | 63 (54–73) | – | – | – | – |

| Weight (kg) | 97 (84–109) | 86 (76–99) | −10 (8.9) | <0.001 | 181 (97) |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 63 (54–80) | 46 (42–53) | −21 (19) | <0.001 | 183 (98)* |

| Serum cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.9 (4.1–5.7) | 4.3 (3.6–5.0) | −0.5 (0.9) | <0.001 | 107 (58) |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | +0.1 (0.3) | 0.002 | 114 (61) |

| Total chol/HDL ratio | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 3.9 (3.0–4.4) | 0.5 (0.9) | <0.001 | 102 (58) |

| Calculated LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.6 (2.9–4.5) | 3.1 (2.5–3.6) | −0.5 (0.9) | <0.001 | 100 (54) |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 2.1 (1.4–3.2) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | −0.9 (1.2) | <0.001 | 108 (58) |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 140 (134–150) | 132 (122–138) | −12 (16) | <0.001 | 128 (69) |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80 (78–90) | 78 (70–80) | −5.8 (9.7) | <0.001 | 128 (69) |

| 2. Cohort of 94 T2D participants achieving remission mean (SD) duration of diet: 35 (31) months Mean (SD) time from diagnosis to diet start: 43 (65) months | |||||

| Age (years) | 63 (54–72) | – | – | – | – |

| Weight (kg) | 96 (84–111) | 83 (74–100) | −12 (9.2) | <0.001 | 90 (96) |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 54 (50–62) | 43 (39–45) | −17 (15) | <0.001 | 91 (97)* |

| Serum cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.0 (4.0–5.4) | 4.2 (3.6–5.1) | −0.4 (1.0) | 0.002 | 48 (51) |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | +0.2 (0.3) | <0.001 | 51 (54) |

| Total chol/HDL ratio | 4.2 (3.1–5.0) | 4.0 (3.0–4.4) | −0.5 (0.9) | 0.001 | 46 (49) |

| Calculated LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.6 (2.8–4.1) | 3.1 (2.5–3.6) | −0.5 (1.1) | 0.001 | 43 (46) |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.9 (1.3–3.0) | 1.3 (0.9–1.7) | −0.9 (1.3) | <0.001 | 46 (49) |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 140 (136–155) | 132 (121–140) | −14 (18) | <0.001 | 63 (67) |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80 (78–90) | 76 (70–80) | −7 (10) | <0.001 | 63 (67) |

| 3. Cohort of 92 T2D participants not achieving remission mean (SD) duration of diet: 31 (23) months Mean (SD) time from diagnosis to diet start: 84 (68) months | |||||

| Age (years) | 62 (55–73) | add data | – | – | – |

| Weight (kg) | 97 (86–108) | 89 (79–99) | −8.6 (8.4) | <0.001 | 91 (99) |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 75 (65–91) | 54 (49–60) | −24 (21) | <0.001 | 92 (100) |

| Serum cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.8 (4.2–5.8) | 4.3 (3.6–4.8) | −0.5 (0.9) | <0.001 | 59 (64) |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.4) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.315 | 63 (68) |

| Total chol/HDL ratio | 4.0 (3.0–5.1) | 3.8 (2.9–4.6) | 0.5 (1.0) | <0.001 | 56 (61) |

| Calculated LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.5 (2.9–4.7) | 3.1 (2.4–3.7) | −0.6 (0.8) | <0.001 | 57 (62) |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 2.2 (1.6–3.2) | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) | −0.8 (1.2) | <0.001 | 62 (67) |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 140 (132–149) | 132 (124–138) | −11(13) | <0.001 | 65 (71) |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80 (76–85) | 78 (70–80) | −4.1 (8.9) | <0.001 | 65 (71) |

*HbA1c is known for all participants at latest follow-up for classification as ‘in remission’, however, baseline HbA1c is not known for three participants.

BP, blood pressure; HbA1c, Glycated Haemoglobin; HDL, High-Density Lipoprotein; LDL, Low-Density lipoprotein; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1.

Change in weight, metabolic parameters and systolic blood pressure in the cohort of 186 patients with T2D followed up for an average of 33 months. BP, blood pressure; T2D, type 2 diabetes. HDL High-Density Lipoprotein

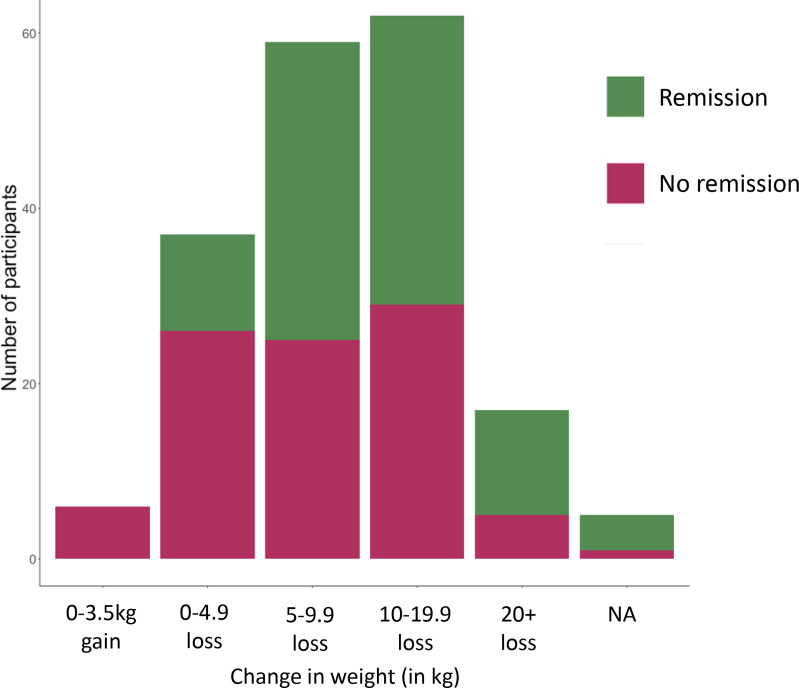

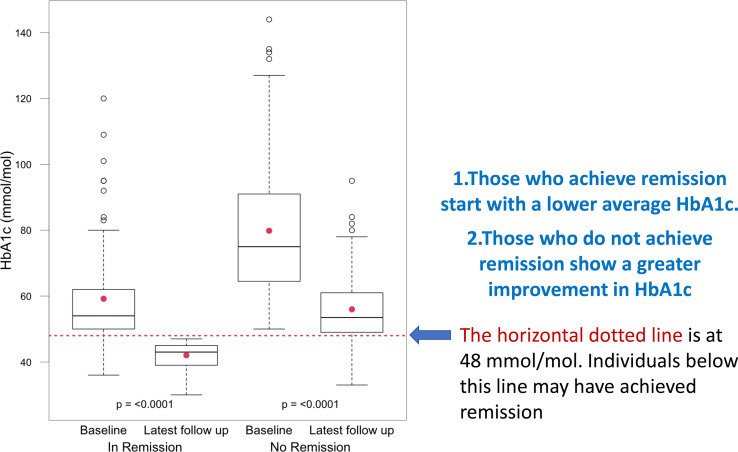

Data for baseline and latest follow-up both for remission and non-remission subcohorts are compared further down in table 1. The mean (SD) weight change was −12 (9.2) kg for the remission group compared with −8.6 (8.4) kg for the non-remission group (non-significant). No patients achieved remission without some weight loss, though in three patients it was one kg or less. The distribution of weight change between the remission and non-remission groups is shown in figure 2. In the remission group HbA1C dropped by a mean(SD) of 17 (15) mmol/mol compared with 24 (21) mmol/mol for the non-remission group. The remission group also started with a lower baseline HbA1c (figure 3 and table 2). This group had been on the diet for a mean (SD) of 37 (42) months compared with 31 (23) months for the non-remission group

Figure 2.

Number of patients divided into those who achieve remission and those who do not plotted against change in weight (in kg). NA, not applicable.

Figure 3.

Baseline and latest follow-up HbA1c figures in mmol/mol divided into remission and no-remission groups shown as box and whisker graphs. Mean duration of the low-carbohydrate diet 33 months. HbA1c, Glycated Haemoglobin

Table 2.

Comparing baseline data for a cohort of 186 people with T2D who chose a low-carbohydrate diet segregated into: (1) the group who go on to achieve remission; (2) the group who do not achieve remission

| Baseline metric | Remission group n=94 on the diet for a mean(SD) of 35 (31) months Median (IQR) |

Non-remission group n=92 on the diet for a mean(SD) of 31 (23) months Median (IQR) |

P value |

| Time since diagnosis (Months) | 2.0 (0.0–68) | 72 (28–127) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 54 (50–62) | 75 (65–91) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 63 (54–72) | 62 (55–73) | 0.903 |

| Weight (kg) | 96 (84–111) | 97 (86–108) | 0.850 |

| Serum cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.0 (4.0–5.4) | 4.8 (4.2–5.8) | 0.817 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 0.799 |

| Calculated LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.6 (2.8–4.1) | 3.5 (2.9–4.7) | 0.736 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.9 (1.3–3.0) | 2.2 (1.6–3.2) | 0.058 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 140 (136–155) | 140 (132–149) | 0.307 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80 (78–90) | 80 (76–85) | 0.097 |

BP, blood pressure; HbA1c, Glycated Haemoglobin; HDL, High-Density Lipoprotein; LDL, Low-Density Lipoprotein; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

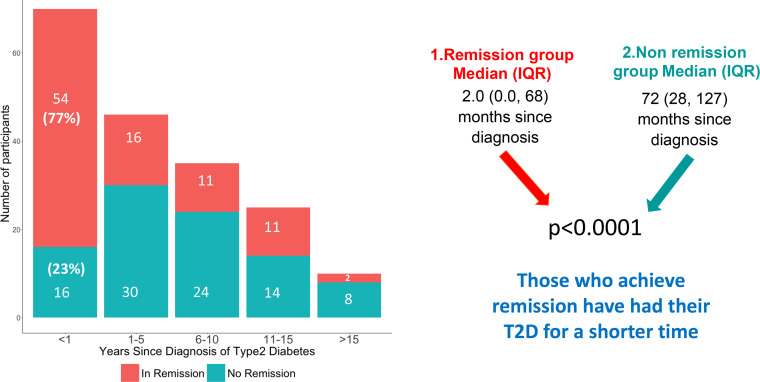

Data on baseline figures comparing the remission group with the non-remission group are shown in table 2. Only two metrics showed significant difference: Baseline median (IQR) HbA1c for the remission group was 54 (50–62) mmol/mol compared with 75 (65–91) mmol/mol for the non-remission group (p<0.001). Baseline median (IQR) for time since diagnosis was 2 (0.0–68) months for the remission group compared with 72 (28–127) months for the non-remission group (p<0.001). The remission group were more likely to be diagnosed recently and have a significantly lower baseline HbA1c. All other baseline metrics: age, weight, blood lipids and BP were not significantly different between remission and non-remission groups.

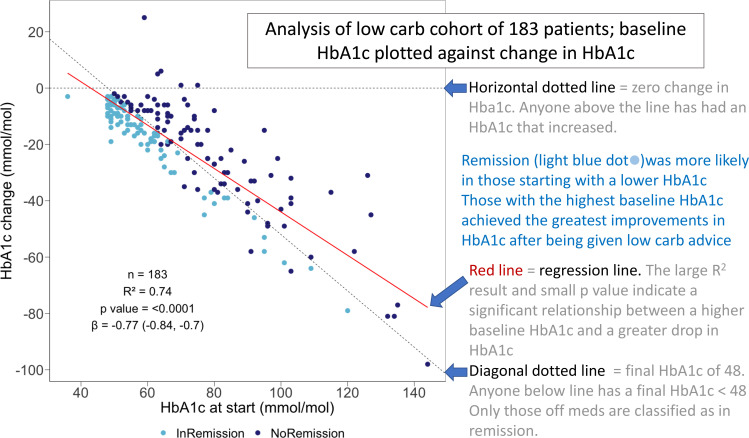

A linear regression model fitted with HbA1c reduction as the outcome and baseline HbA1C as the predictor demonstrated a highly significant relationship R2=0.74; p<0.0001 (figure 4 and online supplemental file 6). Those starting with the highest HbA1c were more likely to achieve the greatest improvements in HbA1c but were less likely to achieve remission (logistic regression, online supplemental file 7). F igure 4 also shows that 178 patients showed an improved HbA1c, only 5 (3%) had a worse result at latest follow-up.

Figure 4.

Regression analysis of the improvement in HbA1c over an average of 33 months with respect to baseline HbA1c. HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin.

Recent diagnosis (<1 year) of diabetes was an important predictor of remission (see figure 5, online supplemental file 7). In the first year after diagnosis 77% of those given low-carbohydrate advice achieved a HbA1c of<48 mmol/mol while not taking any diabetic medication. The comparable figures for established T2D were 35%, 31%, 44% and 20% for durations of 1–5, 5–10, 10–15 and greater than 15 years. By April 2021, 94 people had achieved remission, this was 51% of those choosing a low-carbohydrate approach and 20% of the total practice T2D disease register (table 3).

Figure 5.

A cohort of 186 patients with T2D on a low-carbohydrate diet for an average of 33 months stratified according to years since diagnosis, comparing baseline data for time since diagnosis of T2D between the remission group (n=94) and non-remission group (n=92). T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Table 3.

Norwood practice data on T2D remission March 2015–April 2021

| Data collected to: |

Mean duration of low-carbohydrate approach | No of T2D cases in remission HbA1c<48* |

No of choosing the approach | Remission rate for people who choose the low-carbohydrate approach | No of patients with T2D on the diabetic register | Overall remission rate for practice |

| March 2017 | 13 months | 15 | 48 | 31% | 416 | 4% |

| May 2018 | 20 months | 41 | 106 | 39% | 454 | 9% |

| January 2019 | 22 months | 59 | 123 | 48% | 469 | 13% |

| March 2020 | 30 months | 68 | 143 | 48% | 485 | 14% |

| April 2021 | 33 months | 94 | 186 | 51% | 473 | 20% |

*T2D remission defined as: previous diagnosis of T2D by WHO criteria and HbA1c <6.5% (<48 mmol/mol) without antidiabetes medication. As per McCombie et al. 39 in mmol/mol.

HbA1c, Glycated haemoglobin; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Prediction of remission with logistic regression models looking at baseline data on HbA1c, weight, age, gender and time since diagnosis (online supplemental files 9 and 10) showed that only a lower baseline HbA1c and less time since diagnosis of T2D were good predictors of remission. Taken together these two factors could predict remission with an accuracy (95% CI) of 79% (72% to 84%), 73% sensitivity, 85% specificity.

Interrogation of the Openprescribing website for the year ending January 2022 revealed that of the 16 local GP practices that make up Southport and Formby Clinical Commissioning Group Norwood Surgery spent £68 353 less on drugs for diabetes than is average for the area (online supplemental file 11).

Discussion

In our cohort of 186 patients on the lower carbohydrate programme for an average of 33 months, average weight fell by 10 kg and HbA1c by 21 mmol/mol, with significant reductions in Low-Density Lipoproteine(LDL) cholesterol, triglyceride, systolic and diastolic BP. HDL cholesterol increased significantly. Together these form some of the major risk factors not just for T2D but also for cardiovascular disease. T2D remission was achieved by 51% of the cohort, 20% of the practice T2D disease register.

These outcomes are very different from those reported in many low-carbohydrate diet studies and reasons must be considered. The striking observation is the substantial fall in weight, not always seen in studies of this dietary approach.2 3 18 Weight loss was observed in the only other study of a low-carbohydrate diet which achieved good rates of remission of T2D.7 Delivery by a trusted health professional and frank discussion of the importance of weight loss would appear to have been important in bringing about the observed effects. Consistent long-term management was achieved by the primary care team.

Ongoing support is essential in preventing a return to old habits. It is possible that for some people food, much like nicotine and alcohol may be addictive.16 This may explain why highly processed foods can be so challenging to give up permanently.19 We have found the idea of food addiction can help people better understand their relationship with food. Ongoing benefits from this approach depend on sticking with the diet and long-term weight loss. One of our patients commented ‘this is a lifestyle rather than a diet’. Our programme is diet focused, the addition of exercise may well improve results further.20 An important part of the programme is the continued monitoring of weight allowing early detection of ‘slipping back’. For the most people, increasing weight and HbA1c is simply a reflection of ‘carb creep’, clinicians should recognise this. It is not that the diet itself has failed, it is a failure of dietary adherence. For many people, this situation simply requires a phone call to ask ‘have you any idea why your blood has become more sugary?’ Such close personal follow-up was observed to be effective. We found that most people knew that carbs had crept back and realised they needed to return to what had worked before. This is where our open-access group work via Zoom helps. Those needing a refresher can join without an appointment. Rarely, we have seen the worrying scenario of rising HbA1c despite significant weight loss. Clearly missed diagnosis of type 1 diabetes or pancreatic cancer should be considered. We have also learnt that anticipating and discussing challenging situations such as Christmas and holidays in advance helped our patients to plan before problems arose. For the many whose control slips, we have found it is helpful to ask afterwards ‘What could you do differently next time?’. With empathy and ongoing support our mistakes can be an opportunity to learn.

An essential component of our success appears to be the offer of hope while supporting people to consider different approaches to T2D. It may seem challenging to enthuse those with long-standing T2D who have poor diabetic control. However, previous qualitative research suggests that changing to a dietary approach to manage diabetes is well accepted, particularly in people with T2D for up to 6 years.21 22 Although we found remission rates to be lower in those with longstanding T2D, those in this high-risk group still benefit significantly from reducing their carbohydrate intake and losing weight in terms of greatly improved diabetic control. Perhaps the most important messages from this audit is that clinical benefit does not depend on achieving remission.

The T2D remission rate at the Norwood surgery has improved every single year since 2017 as shown in table 3. We are becoming increasingly effective. Why is this? We believe that offering hope of a better future is essential, coupled with clear messages delivered by supportive peers and professionals. Follow-up with honest feedback is essential. A very helpful motivational technique is to offer our patients dietary change as an alternative to lifelong medication. Interestingly, when offered this choice not a single person in 8 years chose lifelong medication but renewed their dietary efforts.

Seventy-seven per cent of those opting to try the low-carbohydrate-based programme in the first year following diagnosis achieved remission as shown in figure 4. Our data clearly show that the best chance of remission is in those with T2D for least time, consistent with previous observations.23–25 The remission rate drops after that first year, suggesting that those leaving it longer are missing an important window of opportunity. We should focus on ‘metabolic age’ (duration of T2D) rather than chronological age. We found that those people who achieve remission start with a lower HbA1c. This may be anticipated, but there is still hope for those starting with a higher HbA1c. Those with the highest HbA1c at baseline were most likely to see the biggest improvements in HbA1c on reducing dietary carbohydrate as shown in figure 4 (although five patients achieved remission despite starting with a HbA1c >90 mmol/mol). This gives hope to those with poorly controlled T2D who are more likely to achieve significant mitigation than remission and avoid medication. Finally looking at figure 4, it can be seen that only 5 out of 183 (3%) participants choosing a low-carbohydrates approach recorded a worsening HbA1c result.

The role of weight loss in remission is important.26 Our findings support this, with none achieving remission without weight loss. A commonly reported patient finding was how surprised they were not to feel hungry on this diet. Interestingly randomised controlled trials have shown a low-carbohydrate diet may both increase energy expenditure27 and reduce appetite,28 which would make weight loss much easier. The studies which have revealed the physiological changes underlying remission demonstrate the considerable reduction in liver fat content associated with weight loss. In a primary care series of people apparently free of liver disease, liver fat decreased from the very high level of 16.0% to just 3.1%.24 This completely reverses the liver insulin resistance which causes fasting hyperglycaemia. It also resulted in a sharp reduction in exported triglyceride from the liver to all ectopic sites including the pancreas. This decrease in pancreatic fat supply permits relief of the metabolic stress which causes beta cell dysfunction.4 24 29 It is likely that weight loss by any means can induce remission. Other studies of remission have used a relatively high carbohydrate, low calorie approach and clinical studies of food-based approaches or bariatric surgery both achieve remission.25 30 The question is which approach is safe, effective and most acceptable to patients? The present data demonstrate a highly effective method in primary care which allows continued avoidance of weight regain. In a study of adults with screen-detected T2D, weight loss of ≥10% early in the disease was associated with a doubling of remission at 5 years.31

The rising cost of drug treatments for T2D is of great concern, especially in an ageing population and an obesity epidemic. The substantial prescribing savings documented in this audit are therefore of profound importance. It is clear that medication will be required for many people with T2D especially those with longer duration disease. However, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines on T2D focus more on medication while paying scant attention to diet.32 The management of most diseases is based on knowledge of pathophysiology but this new understanding of the nature of T2D20 has not yet been incorporated into such guidelines. Change is underway, guided by the National Health Service (NHS) England diabetes remission programme.33 Major national savings in prescribing costs for T2D are achievable. It is also important to appreciate the potential risks of some medications. SGLT2 inhibitors can cause potentially fatal ketoacidosis.34 A practical summary is included in online supplemental file 1, doctor/nurse protocol.

Limitations are common to all practice-based service evaluations of this kind. The lack of randomisation introduces the risk of selection bias as those least motivated to return to health are less likely to embark on the programme. It is unlikely that cases are ‘cherry picked’ given the high average baseline HbA1c (63 mmol/mol). The absence of a control group means we cannot compare this dietary intervention directly with routine care. We acknowledge the risk of reporting bias as we rely on each persons’ word regarding dietary adherence, however, the mean weight loss of 10 kg suggests significant dietary change. We cannot be certain of the exact nature of the change or the balance of the different macronutrients in the diet of participants. The magnitude of average improvement and the fact this cohort are a large proportion (39%) of the known T2D disease register of a UK NHS practice with 9800 patients is encouraging, as is the observation that this approach has been shown to help people with T2D in other UK general practices.35 36

Conclusions

In England alone, the National Diabetes Audit 2020–2021 data release37 confirmed that over one million people have poorly controlled T2D with a HbA1c >58 mmol/mol. This has important implications for mortality as the UK National Diabetes Audit and Office of National Statistics estimate that each year spent with HbA1c >58 mmol/mol loses a patient around 100 days of life.38 Novel solutions to this problem must be identified as routine UK NHS care is clearly insufficient. In this context our cohort improved average HbA1c from 63mmol/mol to 46 mmol/mol. Norwood surgery has supported people with T2D reduce dietary carbohydrates and lose weight for over 8 years. This has delivered significant improvements in HbA1c with 20% of the practice’s population achieving drug-free T2D remission. There have also been a range of important cardiovascular risk factor improvements. Diabetes drug savings are £68 353 per year compared with the local average. These savings are likely to be dwarfed by cost savings from reduced complications of T2D and days lost from work. Our findings show that a low-carbohydrate intervention with weight loss can be particularly effective in delivering remission for those with either a lower HbA1c or who have had diabetes for a shorter time. It can also give hope to those with poorly controlled T2D who had the greatest improvements in HbA1c.

Footnotes

Twitter: @lowcarbGP

Contributors: DU initiated the approach in the practice, designed the infographics and wrote the initial drafts. JU organised and ran the group consultations, also training all clinical staff in using patients’ own goals and feedback to implement change. CD did the statistics, produced the tables, the boxplots and regression models. ST supported the approach within the practice and co-edited the manuscript. RT advised on data interpretation and co-edited the manuscript. DU is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: No, there are no competing interests.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Brown A, McArdle P, Taplin J, et al. Dietary strategies for remission of type 2 diabetes: a narrative review. J Hum Nutr Diet 2022;35:165–78. 10.1111/jhn.12938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Korsmo-Haugen H-K, Brurberg KG, Mann J, et al. Carbohydrate quantity in the dietary management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2019;21:15–27. 10.1111/dom.13499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sainsbury E, Kizirian NV, Partridge SR, et al. Effect of dietary carbohydrate restriction on glycemic control in adults with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;139:239–52. 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lim EL, Hollingsworth KG, Aribisala BS, et al. Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia 2011;54:2506–14. 10.1007/s00125-011-2204-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Taylor R, Al-Mrabeh A, Sattar N. Understanding the mechanisms of reversal of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7:726–36. 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30076-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (direct): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018;391:541–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33102-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hallberg SJ, McKenzie AL, Williams PT, et al. Effectiveness and safety of a novel care model for the management of type 2 diabetes at 1 year: an open-label, non-randomized, controlled study. Diabetes Ther 2018;9:583–612. 10.1007/s13300-018-0373-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Riddle MC, Cefalu WT, Evans PH, et al. Consensus report: definition and interpretation of remission in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2021;64:2359–66. 10.1007/s00125-021-05542-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Unwin D, Unwin J. Low carbohydrate diet to achieve weight loss and improve HbA 1c in type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes: experience from one general practice. Practical Diabetes 2014;31:76–9. 10.1002/pdi.1835 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Unwin D, Khalid AA, Unwin J, et al. Insights from a general practice service evaluation supporting a lower carbohydrate diet in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and prediabetes: a secondary analysis of routine clinic data including HbA1c, weight and prescribing over 6 years. BMJ Nutr Prev Health 2020;3:285–94. 10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Unwin DJ, Tobin SD, Murray SW, et al. Substantial and sustained improvements in blood pressure, weight and lipid profiles from a carbohydrate restricted diet: an observational study of insulin resistant patients in primary care. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:2680. 10.3390/ijerph16152680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Unwin D, Unwin J, Crocombe D, et al. Renal function in patients following a low carbohydrate diet for type 2 diabetes: a review of the literature and analysis of routine clinical data from a primary care service over 7 years. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2021;28:469–79. 10.1097/MED.0000000000000658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Unwin JD, Cuthbertson DJ, Feinman R. A pilot study to explore the role of a lowcarbohydrate intervention to improve GGT levels and HbA1c. Diabesity in practice 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the International consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1593–603. 10.2337/dci19-0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Unwin D, Lake I. An e-learning course on type 2 diabetes and the low Gi diet., in RCGP; 2018.

- 16. Gordon EL, Ariel-Donges AH, Bauman V, et al. What Is the evidence for "food addiction?" a systematic review. Nutrients 2018;10:477. 10.3390/nu10040477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Unwin D UJ. A simple model to find patient hope for positive lifestyle changes: GRIN.Unwin D,Unwin J.Journal of holistic healthcare Volume 16 Issue 2 Summer 2019. Journal of holistic healthcare 2019;16. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taylor R, Ramachandran A, Yancy WS, et al. Nutritional basis of type 2 diabetes remission. BMJ 2021;374:n1449. 10.1136/bmj.n1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schulte EM, Avena NM, Gearhardt AN. Which foods may be addictive? the roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117959. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taylor R, Al-Mrabeh A, Sattar N. Understanding the mechanisms of reversal of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019. 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30076-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rehackova L, Araújo-Soares V, Steven S, et al. Behaviour change during dietary type 2 diabetes remission: a longitudinal qualitative evaluation of an intervention using a very low energy diet. Diabet Med 2020;37:953–62. 10.1111/dme.14066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rehackova L, Araújo-Soares V, Adamson AJ, et al. Acceptability of a very-low-energy diet in type 2 diabetes: patient experiences and behaviour regulation. Diabet Med 2017;34:1554–67. 10.1111/dme.13426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Steven S, Hollingsworth KG, Al-Mrabeh A, et al. Very low-calorie diet and 6 months of weight stability in type 2 diabetes: pathophysiological changes in responders and nonresponders. Diabetes Care 2016;39:808–15. 10.2337/dc15-1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taylor R, Al-Mrabeh A, Zhyzhneuskaya S, et al. Remission of human type 2 diabetes requires decrease in liver and pancreas fat content but is dependent upon capacity for β cell recovery. Cell Metab 2018;28:547–56. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Panunzi S, Carlsson L, De Gaetano A, et al. Determinants of diabetes remission and glycemic control after bariatric surgery. Diabetes Care 2016;39:166–74. 10.2337/dc15-0575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Taylor R. Type 2 diabetes and remission: practical management guided by pathophysiology. J Intern Med 2021;289:754–70. 10.1111/joim.13214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Klein GL, et al. Effects of a low carbohydrate diet on energy expenditure during weight loss maintenance: randomized trial. BMJ 2018;363:k4583. 10.1136/bmj.k4583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hu T, Yao L, Reynolds K, et al. The effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2016;26:476–88. 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhyzhneuskaya SV, Al-Mrabeh A, Peters C, et al. Time course of normalization of functional β-cell capacity in the diabetes remission clinical trial after weight loss in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2020;43:813–20. 10.2337/dc19-0371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steven S, Lim EL, Taylor R. Population response to information on reversibility of type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2013;30:e135–8. 10.1111/dme.12116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dambha-Miller H, Day AJ, Strelitz J, et al. Behaviour change, weight loss and remission of type 2 diabetes: a community-based prospective cohort study. Diabet Med 2020;37:681–8. 10.1111/dme.14122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. NICE . Type 2 diabetes in adults: management, 2022. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28 [Accessed 31 Dec 2022].

- 33. England N. Low calorie diets to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes, 2019. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/diabetes/treatment-care/low-calorie-diets/

- 34. Murdoch C, Unwin D, Cavan D, et al. Adapting diabetes medication for low carbohydrate management of type 2 diabetes: a practical guide. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:360–1. 10.3399/bjgp19X704525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Morris E, Aveyard P, Dyson P, et al. A food-based, low-energy, low-carbohydrate diet for people with type 2 diabetes in primary care: a randomized controlled feasibility trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020;22:512–20. 10.1111/dom.13915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oliver D, Andrews K. Brief intervention of low carbohydrate dietary advice: clinic results and a review of the literature. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2021;28:496–502. 10.1097/MED.0000000000000665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. National diabetes audit 2020-21 data release, 2021. England. Available: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-diabetes-audit

- 38. Heald AH, Stedman M, Davies M, et al. Estimating life years lost to diabetes: outcomes from analysis of national diabetes audit and office of national statistics data. Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab 2020;9:183–5. 10.1097/XCE.0000000000000210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McCombie L, Leslie W, Taylor R, et al. Beating type 2 diabetes into remission. BMJ 2017;358:j4030. 10.1136/bmj.j4030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjnph-2022-000544supp001.pdf (1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.