Graphical abstract

Keywords: Ultrasound, Heat treatment, Coix seed prolamins, Protein modification, Enzymatic hydrolysis characteristics, α-Glucosidase inhibitory peptide

Highlights

-

•

HT + US can change the structure of coix seed prolamin and make it more stretch.

-

•

HT + US can accelerate coix seed prolamin enzymolysis.

-

•

HT + US increased reaction rate constant kin significantly (P < 0.05).

-

•

HT + US decreased the values of Ea, ΔH and ΔS (P < 0.05).

Abstract

The self-assembled structures of coix seeds affected the enzymatic efficiency and doesn‘t facilitate the release of more active peptides. The influence of heating combined with ultrasound pretreatment (HT + US) on the structure, enzymatic properties and hydrolysates (CHPs) of coix seed prolamin was investigated. Results showed that the structural of coix seed prolamins has changed after HT + US, including increased surface hydrophobicity, reduced α-helix and random coil content, and a decrease in particle size. So that, leads to changes in thermodynamic parameters such as an increase in the reaction rate constant and a decrease in activation energy, enthalpy and enthalpy. The fractions of <1000 Da, degree of hydrolysis and α-glucosidase inhibitory were increased in the HT + US group compared to single pretreatment by 0.68%–17.34%, 12.69%–34.43% and 30.00%–53.46%. The peptide content and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of CHPs could be maintained at 72.21 % and 57.97 % of the initial raw materials after in vitro digestion. Thus, the findings indicate that HT + US provides a feasible and efficient approach to can effectively enhance the enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency and hypoglycaemic efficacy of CHPs.

1. Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a topic commonly feature is hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, which is a chronic metabolic disease with a high incidence in the world [1], [2]. The damage caused by T2DM can be effectively mitigated by regulating the activity of related metabolic enzymes, including inhibition the activity of α-glucosidase, α-amylase, dipeptidyl peptidase IV, and promotion the secretion of glucagon-like peptide 1 and other pathways [3]. The α-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.20) is the key enzyme involved in the carbohydrate digestion process. The α-glucosidase inhibitory peptide, which slow the final stages of carbohydrate digestion and consequently preventing the entry of glucose into the circulation, is considered as a viable prophylactic treatment of hyperglycemia. However, chemical α-glucosidase inhibitors have certain adverse effects on the human body after long-term use, such as abdominal distension, gastrointestinal discomfort, etc [4]. Therefore, the development of a safe, effective and long-term use of food-derived α-glucosidase inhibitors is a hot spot in this research field.

Coix seed (Coix larchryma-jobi L.), a medicine-food homologous cereal, is prevalent mainly in tropical Asia. Coix seed has a variety of health benefits, including low glycemic index, lipid-profit regulation and anti-obesity, causing these effects mainly mainly due to the richness of the active component (protein, lipids and polyphenols) in coix seed [5], [6]. Numerous studies have confirmed that coix seed protein improves the symptoms of T2DM mice by repairing islet cells, improving the inflammatory response, regulating lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in multiple ways [7], [8]. Coix seed prolamins is rich in amino acids such as Leu, Pro and Ala, suggesting that coix seed prolamins may be a potential source of α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides [9]. However, no studies in this area have been reported. An important reason is that the compact molecular structure of coix seed prolamins causes the enzymatic hydrolysis rate to be blocked, and the problem of low peptide conversion rate [10] has not been well solved. Heat treatment (HT) and ultrasound treatment (US) is a treatment commonly in the food industry, it can be used to stretch the structure of proteins, expose more active sites and ultimately enhance enzymolysis efficiency [11], [12]. Although, there are limitations to improving the enzymolysis efficiency by HT or US alone. For example, large aggregates would form when HT, which leads to a blockage of the enzymatic reaction [13]. In contrast, heating combined with ultrasound pretreatment (HT + US) can alter the thermal aggregation morphology to obtain smaller protein particles, allowing for a fuller unfolding of the protein structure [14], [15] and enhancing the probability of obtaining bioactive peptides [16]. However, fewer studies have been conducted to improve the enzymolysis efficiency of coix seed prolamins and to assess its effect on the structure, enzymatic properties and hydrolysis products (CHPs) of coix seed prolamins using suitable pretreatment methods.

This study is the first to characterise the structure and enzymatic thermodynamic reactions of coix seed prolamins under the different pretreatment conditions (HT, US, and HT + US) to clarify the differences in the conformational and enzymatic reaction characteristics of coix seed prolamins before and after modification by HT + US treatment and to explore the potential mechanism of enzymatic hydrolysis by HT + US. The characteristic parameters of the CHPs prepared under the different pretreatment conditions, including the degree of hydrolysis, molecular weight distribution, and-glucosidase inhibition activity, were determined to explore the compositional characteristics of the CHPs (especially the HT + US group). Finally, the changes in the peptide content and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of HT + US-treated CHPs during in vitro digestion were further determined to examine their bioavailability and provide a preliminary assessment of the application potential of CHPs prepared by HT + US-assisted enzymatic digestion. This study aimed to provide a reference for the efficient utilisation of coix seed prolamins.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

Coix seeds were purchased from Ganzhou Hengrui Agricultural Products Co. Ltd. (Jiangxi, China). Alkaline protease (Alcalase), α-glucosidase, p-nitrophenyl-d-glucopyranoside (pNPG), artificial saliva, artificial gastric fluid, and artificial small intestine fluid were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Dithiothreitol (DTT), dinitrobenzoic acid (DTNB), and glycine were purchased from Guangzhou Shuopu Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Guangdong, China). Potassium tartrate was purchased from the Tianjin Comio Chemical Reagent Development Centre (Tianjin, China). Forinol was purchased from Shanghai Ruji Biotechnology Development Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Trichloroacetic acid was purchased from Fuchen (Tianjin) Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and anhydrous (NaAc) were purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China). Potassium bromide (KBr) and 8-aniline-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid (ANS) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Non-pre-dyed markers were purchased from Beijing Lanjike Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). The sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel preparation kit was purchased from Beijing Solarbio Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade.

2.2. Preparation of coix seed prolamins

Firstly, the coix seed was ground and sieved through 80 mesh and then mixed with petroleum ether 1:5 (w/v) to degrease the coix seed powder to obtain degreased coix seed powder. Coix seed prolamins were extracted using the alcoholic extraction and water sedimentation methods. An 80% ethanol solution, 1 mg/mL dithiothreitol (DTT) solution, and 3 mol/L NaAc solution were added to the protein extraction solution at a volume ratio of 100:1:1 and mixed with defatted barley powder at a total material-to-liquid ratio of 1:6 (w/v). The sample solution was sonicated at 40 °C (250 W, 40 kHz) for 30 min and centrifuged at 3500×g for 20 min to obtain the supernatant before adding an equal volume of deionised water to the supernatant to obtain barley alcohol-soluble protein. The purity of the coix seed prolamins prepared using this method was 83.78 ± 1.95%.

2.3. Determination of amino acid composition

The specific method for determining the amino acid content of coix seed prolamins is described in GB/T5009.124-2016 [17]. Briefly, coix seed prolamins (0.020 g) were placed in the hydrolysis tubes. The sample was hydrolysed with 10 mL of HCl solution (6 mol/L), and nitrogen was charged into the hydrolysis tube and hydrolysed at 110 °C for 22 h. After completion, the hydrolysate was filtered into a 50-mL volumetric flask and fixed with ultrapure water. An amount of the diluted solution was pipetted through a 0.22-μm filter membrane and analysed using an automated amino acid analyser (L-8900; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. HT + US pretreatment

Two grams of coix seed prolamins were mixed with 50 mL of deionised water to prepare a 4% protein solution and stirred for 30 min using a magnetic stirrer at 500 rpm. The treatment group was defined as the HT group and treated for 30 min in a water bath at 90 °C (DF-101S Collective Heating Magnetic Stirrer; Shanghai Lichenbangxi Instrument Technology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China). The US group was treated at 300 W, 40 kHz, and 25 °C for 30 min (SB25-12DTD Ultrasonic Cleaner; Ningbo Xinzhi Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Ningbo, China). The HT + US group was treated with a 90 °C water bath for 30 min and then sonicated at 300 W, 40 kHz, and 25 °C for 30 min. The control group was not pretreated. The samples were freeze-dried and prepared for further use.

2.5. Structural characterisation of coix seed prolamins

2.5.1. SDS-PAGE

SDS-PAGE was performed for each treatment group, according to the method described by Resendiz-Vazquez et al. [18]. Protein samples were dissolved in 80% ethanol to a concentration of 5 mg/mL, added to an equal amount of loading buffer, and rapidly mixed and denatured in a boiling water bath for 5 min. The electrophoresis conditions were as follows: 10 μL loading volume, 5% concentrate, 12% separator gel, and applied voltage of 80–120 V. Staining was performed using a staining solution (0.00116% Komas Brilliant Blue) for 2 h. Then, the stain was decolourised in decolourisation solution three to four times, and the bands were photographed after they were clear.

2.5.2. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

The infrared spectra and secondary structures of coix seed prolamins before and after pretreatment were analysed using a Fourier infrared spectrometer (TENSORII FTIR; Tianjin Jinbeier Technology Co., Ltd., Tianjing, China) according to the method described by Xie et al. [19]. A 2 mg sample was mixed with 200 mg KBr, ground and pressed, and the absorption spectra were measured by full-band scanning at 400–4000 cm−1 at 25 °C. The spectral data obtained were analysed using Peakfit 4.12 software.

2.5.3. Surface hydrophobicity (H0)

The surface hydrophobicity of the samples was analysed using a fluorescence spectrometer (F2700; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), according to the method described by Wang et al. [20]. The protein solution was diluted to a concentration gradient and mixed with 8 mM ANS (100:1 vol ratio). The fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer after 3 min of reaction at an excitation wavelength of 390 nm, an emission wavelength of 468 nm, and a slit width of 5 nm. The initial slope of the fitted curve represented the surface hydrophobicity (H0) of each group.

2.5.4. Intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence spectra of the samples were collected according to the method described by Ma et al. [21] Lyophilised samples were prepared in 1 mg/mL protein solutions using 80% ethanol and scanned using a fluorescence spectrometer (F2700; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), with an excitation wavelength of 280 nm, an emission wavelength of 290–450 nm, and excitation and emission slit widths of 5 nm each.

2.5.5. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM analysis was performed as described by Tian et al. [22]. The lyophilised samples were evenly coated on a double-sided conductive adhesive. The earwash ball was blown for 1 min, and after completion, the raw material coating was sprayed with gold at 10 nm. A Hitachi-S-3400N scanning electron microscope (Hitachi High Technologies Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was used in low-vacuum mode for barley alcoholic protein microstructure observation. The images were magnified to 400× and 2000× and the voltage was set to 15 kV.

2.5.6. Particle size

Firstly, 1 mg of the sample was dissolved in 2 mL of 80 % ethanol solution. The samples were dispersed using an ultrasonic cleaner (CJ-020; Shenzhen Superclean Technology Industry Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) with a parameter of 120 W, 40 kHz, and 5 min. The parameters were 120 W, 40 kHz, and 5 min. The top solution (1 mL) was slowly added to a cuvette to prevent bubble formation. Testing was performed using a Malvern laser particle sizer (Zetasizer Nano ZS90; Malvern Instruments Co., Ltd., UK). After the instrument warmed up for 30 min, the test software was started, the particle size test program was selected, and water was chosen as the solvent, followed by preheating for 30 s at 25 °C before measuring each sample three times in parallel.

2.6. Thermodynamic studies of enzymatic reactions

Coix seed prolamins were dissolved in deionised water after the different pretreatments to maintain a concentration of 4%. The coix seed prolamins suspensions from each treatment group were then placed in a constant stirring water bath at 20, 30, 40, and 50 °C, respectively. Alcalase was used for enzymatic hydrolysis (enzyme addition amount 8000 U/g), and 1 mol/mL NaOH was used to adjust the pH to 9.0. The reaction was terminated after 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 min of hydrolysis. An equal volume of 15% trichloroacetic acid was added to precipitate unhydrolyzed barley alcoholic protein, after which the enzyme was inactivated in a boiling water bath for 15 min. The supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min after cooling, and the peptide concentration in the supernatant was determined using the Folin-Phenol method.

2.6.1. Reaction rate constant (kin) and activation energy (Ea)

According to Ma et al. [23], the alkaline protease hydrolysis of coix seed prolamins can be described by a first-order kinetic equation using the following kinetic model:

| (1) |

where C is the concentration of coix seed prolamins at time t in the enzymatic reaction (g/mL), kin is the reaction rate constant, t is hydrolysis time, and C0 is the initial concentration of coix seed prolamins before the enzymatic reaction (g/mL).

Because the reduction in coix seed prolamins in the enzymatic reaction is difficult to measure, the trend of peptide production in the enzymatic system was chosen to reflect the overall enzymatic process [24]. At constant temperature and pressure, the amount of peptide solution produced at reaction time t (Vt) is proportional to the amount of coix seed prolamins consumed, while the amount of peptide solution produced after the reaction is complete (V∞, obtained after 10 h of enzymatic digestion) is proportional to the initial concentration of coix seed prolamins. Thus, we have C0 ∝ V∞, C∝(V∞-Vt), substituting equation (1) into equation (2). By making “ln(V∞-Vt) ∼ t” graph, we were able to calculate the slope of the line, which was the reaction rate constant kin.

| (2) |

where Vt is the amount of peptide produced after the reaction time t (g/mL), V∝ is the amount of peptide produced after the reaction is complete (µg/mL), and kin is the rate constant of reaction.

The reaction rate constants for the pretreated coix seed prolamins consisted of the following two reaction rate constants, as shown in equation (3):

| (3) |

where kt is the reaction rate constant due to temperature (min−1) and kpre is the reaction rate constant due to pretreatment (HT, US, and HT + US) (min−1).

According to the Arrhenius equation, the relationship between the rate constant of a chemical reaction and the change in temperature is expressed as in equation (4). Then, equation (4) was transformed and rearranged into equation (5), and the apparent activation energy Ea was obtained from the slope of the “lnkin ∼ 1/T” diagram, while the prefactor A was obtained from the intercept:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where A is the prefactor or collision factor (min−1), Ea is the apparent activation energy (J/mol), R is the gas constant 8.314 (J/mol-K), and T is temperature (K).

2.6.2. Enthalpy of activation (ΔH), entropy of activation (ΔS), and Gibbs free energy (ΔG)

According to the thermodynamic expression of the Eyring equation for bimolecular reactions [25], the relationship between ΔS and ΔH with the reaction temperature and reaction rate constant is given by equation (6), which was transformed into equation (7) by taking the natural logarithm:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

where kB is Boltzmann’s constant (1.38 × 10-23 J/K), h is Planck’s constant (6.6256 × 10-34 J/s), ΔG is Gibbs free energy (J/mol), ΔH is the enthalpy of activation (J/mol), and ΔS is the entropy of activation (J/mol·K). By making the “lnkin/T ∼ 1/T” graph as a straight line by equation (7) above, ΔH and ΔS were obtained from the slope and intercept, from which ΔG was calculated using equation (8).

2.7. Characterisation of CHPs from coix seed prolamins

2.7.1. Enzymatic hydrolysis of coix seed prolamins

Based on a previous screening of proteases with α-glucosidase inhibition activity and a hydrolysis index, the effect of various pretreatment techniques on the enzymatic system of coix seed prolamins alkaline protease was investigated. First, the sample was mixed with deionized water and prepared into a 4 % (m/v) coix seed prolamins solution, and the solution was placed in a magnetic stirring pot. The solution was maintained at 50 °C and adjusted to an optimum pH of 9.0. Enzymatic digestion was initiated by adding alkaline protease at a rate of 8000 U/g with constant stirring. The amount of NaOH (1 mol/L) required to maintain pH 9.0 was recorded at 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 105, and 120 min during the enzymatic digestion and used to calculate the degree of hydrolysis.

2.7.2. Degree of hydrolysis (DH)

In this experiment, the DH was determined using the pH-stat method by taking the volume of 1 mol/L NaOH consumed during hydrolysis with alkaline protease to calculate the DH at each stage of the reaction, as follows:

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

where V is the amount of NaOH consumed (mL), N is the concentration of the NaOH solution (mol/L), is the total protein content (g/g) in coix seed prolamins samples, m is the mass of the coix seed prolamins sample (g), htot is the number of millimoles of peptide bonds per unit mass of raw barley protein (8.3 mmol/g), and T is the test temperature.

2.7.3. Molecular weight distribution

Briefly, 10 mg of CHPs were dissolved in 1 mL of mobile phase, filtered through a 0.45-μm membrane, and the molecular weight distribution of CHPs was determined by permeation gel chromatography. The aqueous chromatography column used was TSK gel GMPWXL (TOSH; Tosoh, Japan). The mobile phase was an aqueous solution containing 0.1 N NaNO3 and 0.06% NaN3 at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min and a column temperature of 35 °C. Narrowly distributed polyethylene glycol was used as a standard.

2.7.4. Determination of α-glucosidase inhibitory activity

The degree of α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was determined using the pNPG method, referring to the method provided by Huang et al. [26] Briefly, α-glucosidase and pNPG were prepared at 0.06 U/mL and 2.5 mmol/L, respectively, in 0.1 mol/L, pH 6.8, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, 50 μL of sample solution and 50 μL of α-glucosidase solution were pipetted into a 96-well microtitre plate, which was then mixed and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C in a constant temperature incubator. The pNPG solution (50 μL) was then added and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in a constant-temperature incubator (ZXMP-R1230; Shanghai Zhicheng Analytical Instruments Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China). Upon completion, 100 mL of 0.5 mol/L anhydrous Na2CO3 solution was added to terminate the reaction. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm using an enzyme marker (SPECTROstar Nano Enzyme Marker; BMG LABTECH, Germany). The experimental setup was as follows: (1) test setup: sample + α-glucosidase + pNPG; (2) sample control group: PBS + PBS + pNPG; (3) blank group: PBS + α-glucosidase + pNPG; (4) control group: PBS + PBS + pNPG. Equation (12) was used to calculate the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity:

| (12) |

where As is the absorbance of the sample, An is the absorbance values of the control group, Ac is the absorbance value of blank group, and Ab is the absorbance value of the blank control group.

2.7.5. Bioavailability studies of CHPs

The effects of simulated oral, gastric, and small intestinal digestion on the bioavailability of coix seed prolamins hydrolysate were examined, as described by Wang et al. [27]. A 40-mg lyophilised sample was loaded into a digestion flask and digested in a water bath shaker at 37 °C and 200 rpm. First, 10 mL of artificial saliva (pH 6.8) was added to the digestion system and the digestion reaction was carried out for 5 min to simulate the oral digestion phase. After completion, the enzyme was rapidly inactivated in a boiling water bath for 15 min, cooled, and the pH was adjusted to 3.0, using 1 mol/mL HCL. Then, 10 mL of artificial gastric juice (pH 3.0) was added, and the digestion reaction was carried out for 2 h to simulate the gastric digestion phase. After completion, the enzyme was inactivated in a boiling water bath for 15 min, and the pH of the digestion system was adjusted to 7.0 with 1 mol/mL NaOH after cooling. Finally, 15 mL of an artificial small intestine solution (pH 7.0) was added to the digestion system and allowed to react for 3 h to simulate the small intestine digestion phase, followed by 15 min of enzyme inactivation in a boiling water bath. The peptide content and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the digests were measured at various stages of simulated digestion in vitro.

2.8. Data processing and analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0. Statistical analyses were conducted using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and two-way comparisons of means (Duncan’s test). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Graphs were created using GraphPad Prism 8 (Dotmatics Ltd., San Diego, California, USA) or Origin 8.0 (OriginLab Corporation, USA) for the relevant graphs.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural characterisation of barley alcoholic proteins before and after modification via pretreatment

3.1.1. SDS-PAGE

Fig. 1A shows the SDS-PAGE results for coix seed prolamins under the different pretreatment conditions. As shown in Fig. 1A, the molecular weight of untreated coix seed prolamins was mainly distributed between 18.4 and 35 kDa, with four bands clearly visible, mainly at 31.27, 28.56, 23.83, and 19.88 kDa from the top to bottom, respectively. Coix seed prolamins were found to be mainly composed of four proteins with different molecular weights: α-prolamin (19–22 kDa), β- prolamin (14 kDa), γ- prolamin (16–27 kDa), and σ- prolamin (10 kD) [28]. As shown in the Fig. 1A, The highest expression of coix seed prolamins was γ-prolamin. The bands of the other three prolamins were not obvious, and the expression level was low, consistent with the results of Xie [29]. After HT and US pretreatment, the positions of the bands of coix seed prolamins did not change, indicating that these two pretreatments did not significantly affect the primary structure of coix seed prolamins. At the same time, there was no new band in the lane of the HT + US group, however, the abundance of the original four bands became lighter. This may be due to the cavitation effect of ultrasound, which destroyed the morphology of coix seed prolamins particles and degraded macromolecular proteins into small molecular proteins. At the same time, ultrasonic treatment changed the charge distribution on the surface of coix seed prolamins molecules [30]. Eventually, the protein left the gel surface of the separation gel [31], [32].

Fig. 1.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (A), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) (B), surface hydrophobicity (C), and endogenous fluorescence maps (D) of coix seed prolamins under the different pretreatment conditions. Different lowercase letters for each data point in Fig. 1C indicate significant differences between samples (P < 0.05).

3.1.2. FTIR

FTIR is a common spectroscopic technique used to characterise the secondary structure of protein molecules, and its spectral pattern is closely related to the vibrational state of chemical bonds in the protein molecule [33]. As shown in Fig. 1B, untreated coix seed prolamins exhibited a unique primary peak in the amide A band (3000–3500 cm−1) with an absorption wavelength of 3291.53 cm−1, mainly caused by N-H bending and O-H stretching vibrations [33]. However, the absorption peaks disappeared after the HT, US, and HT + US treatments. In addition, the untreated coix seed prolamins exhibited a strong peak at 1541.66 cm−1 (Fig. 1B), which was associated with C-O and N-H stretching caused by the bending vibrations of inter- or intramolecular hydrogen bonds [34]. The peak decreased after pretreatment, suggesting that pretreatment broke the hydrogen bonds between the coix seed prolamins molecules. After the three pretreatments, the intensity of the absorption peak at 3026.27 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum of the coix seed prolamins decreased and was blue-shifted, with the characteristic peaks at this location corresponding to the symmetric and asymmetric vibrations of –CH2 and –CH3 [20]. The absorption peak at 3000–2800 cm−1 is related to the intermolecular C-H stretching vibration [20].After pretreatment, the intensity of the absorption peak at this position decreases. The above results showed that pretreatment significantly affected the state of N-H bond, O-H bond, C-O bond and C-H bond in the coix seed prolamins molecule, thus changing the secondary structure of the coix seed prolamins.

After Gaussian fitting of the amide I band (1600–1700 cm−1), it was found that compared with the Control group, the content of α-helix, β-sheet and random coil in the HT group was significantly reduced (P < 0.05), and the content of β-turn was significantly increased (P < 0.05) (Table 1), indicating that HT treatment induced the denaturation of coix seed prolamins and the opening of the molecular structure, completing the conversion of α-helix, β-sheet, and random coil to β-turn. After US treatment, the β-sheet content of coix seed prolamins increased, but the content of the other three configurations did not change significantly (P > 0.05). The increase of β-sheet content helped to improve the flexibility of protein molecules and make them elastic [35]. Compared with the Control group and the HT group, HT + US decreased the content of α-helix, increased the content of β-turn and random coil, and had no significant change in the content of β-sheet. This suggests that coix seed prolamins undergo defolding, dissociation, and rearrangement with a higher degree of disorder in the protein molecules [36]. These results show that HT + US can further increase the degree of unfolding and disorder of coix seed prolamins, ultimately yielding a more loosely structured protein molecule.

Table 1.

Secondary structure content of coix seed prolamins under the different protein pretreatments.

| Sample | α-helix (%) | β-sheet (%) | β-turn (%) | Random coil (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 20.99 ± 0.50a | 44.41 ± 1.31b | 22.93 ± 0.52b | 11.67 ± 0.29a |

| HT | 19.55 ± 0.01b | 43.84 ± 0.02b | 28.10 ± 0.06a | 8.51 ± 0.03b |

| US | 20.79 ± 0.30a | 46.03 ± 0.52a | 20.56 ± 2.14b | 12.62 ± 1.32a |

| HT + US | 19.74 ± 0.002b | 44.18 ± 0.003b | 26.97 ± 0.01a | 9.11 ± 0.01b |

Different lowercase letters in the upper-right corner of the data in the same column in Table 1 indicate significant differences between the samples (P < 0.05).

3.1.3. H0

A comparison of the magnitude of the H0 values of each group (Fig. 1C) also revealed that the H0 of each treatment group changed regularly after pretreatment, with a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in the H0 of coix seed prolamins after HT treatment, mainly due to the thermal aggregation effect of the protein molecules, reburying the already exposed hydrophobic groups [34]. This was consistent with the phenomenon observed by Xue et al. [37]. Simultaneously, US treatment induced the unfolding of coix seed prolamins molecules, leading to an increase in the number of exposed hydrophobic groups [38], which ultimately caused an increase in coix seed prolamins H0 (P < 0.05). When compared with the HT group, the HT + US treatment not only elevated the H0 value (by 218.47%), while also the H0 value was significantly higher than that of the US group (P < 0.05). These results indicate that US treatment had a positive effect on the disaggregation of coix seed prolamins. The shock waves, shear forces, and turbulence generated by US facilitated the breaking of non-covalent bonds within the aggregates and depolymerisation occurred, releasing hydrophobic regions previously encapsulated within the coix seed prolamins aggregates. These results show that heating and sonication affected the magnitude of the interlinking forces between peptide groups and alter the amino acid sequence, disrupting the hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic regions within the coix seed prolamins molecule, and that HT + US treatment amplified these effects.

3.1.4. Endogenous fluorescence spectroscopy

In this study, by collecting endogenous fluorescence spectra from different treatment groups, changes in the fluorescence intensity and maximum absorption wavelength (λmax) reflected the degree of exposure of Trp residues within the protein and changes in the microenvironment, which can characterise the tertiary structure of coix seed prolamins to some extent [39]. As shown in Fig. 1D, all four groups of λmax were at 330 nm, with no blue or red shift in the maximum absorption peak, indicating that heating and sonication did not affect the local environment of Trp polarity within coix seed prolamins [40]. Simultaneously, we found that the thermal aggregation and cross-linking reactions caused by HT treatment re-internalised the exposed Trp residues inside the protein, resulting in fluorescence quenching [13]. US treatment enhanced the fluorescence intensity as the compact structure of the coix seed prolamins molecule was opened, and more Trp residues were exposed. Compared to the HT group, the endogenous fluorescence intensity of coix seed prolamins was significantly increased after HT + US treatment, again indicating that US treatment caused a certain degree of depolymerisation of coix seed prolamins aggregates, resulting in the re-release of encapsulated Trp. Cao et al. [41] studied the effect of sonication on the morphology of quinoa protein oxidative clusters and found that sonication at 300 W for 10–30 min induced the dissociation of quinoa protein aggregates and Trp residues away from disulphide bonds and other fluorescent groups, thereby enhancing the fluorescence intensity.

3.1.5. Microscopic morphology and particle size

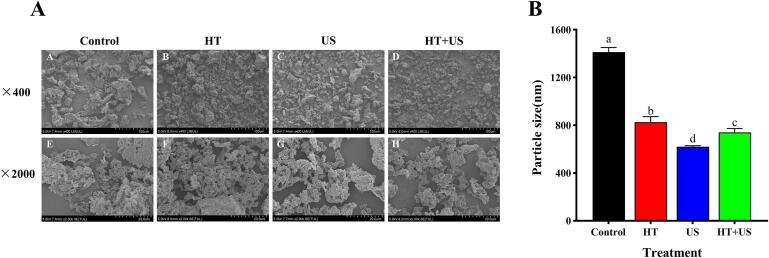

The microscopic morphology and particle size of coix seed prolamins were examined to visualise the microstructure and aggregation of coix seed prolamins before and after the different treatments and to obtain more information on the mesoscopic scale. From Fig. 2A, it can be seen that coix seed prolamins mainly present the morphological characteristics of spherical and rod-like particles with intertwined molecular particles and a certain degree of aggregation, which may be due to the ability of coix seed prolamins to self-assemble into microspheres or nanoparticles during the alcohol extraction process, and some protein molecules show rod-like structures during the water sedimentation process [10]. Coix seed prolamins are highly homologous to cereal alcoholic proteins, such as maize and sorghum, with great structural similarities. Both contain high levels of hydrophobic amino acids (>50%) and low levels of hydrophilic amino acids, exhibiting amphiphilic properties. The amphiphilic nature is the main driver of the self-assembly of these alcoholic proteins, whereas the final structure of the alcoholic proteins of these grains (coix seed, maize, and sorghum) is highly dependent on the protein concentration and solvent polarity during the extraction process, through which the structure of the alcoholic proteins can be targeted or designed to improve product quality [42].

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (A) and particle size (B) of coix seed prolamins soluble proteins under the different pretreatment conditions. Different lowercase letters for each data point in Figure B indicate significant differences between samples (P < 0.05).

HT-treated coix seed prolamins showed finer molecular particles and a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in particle size compared with the control group, with a decrease of 41.52% (Fig. 2B). Simultaneously, the coix seed prolamins molecules underwent extensive aggregation, with shortened molecular spacing and the formation of large structurally compact clusters (Fig. 2A). Compared to the control and HT groups, the coix seed prolamins particles were more dispersed and homogeneous after US treatment (Fig. 2A), and the particle size was also at the lowest level (620.73 ± 8.25 nm) (Fig. 2B). Under the HT or US treatment conditions, coix seed prolamin molecular particles underwent cleavage and the frequency of intermolecular collisions increases, all of which favour a reduction in protein molecular particle size [43]. Compared with the HT group, the HT + US treatment separated the thermally aggregated coix seed prolamin particles, and the protein particles were more evenly distributed and finer in size (Fig. 2A), further reducing their particle size (Fig. 2B). This can be mainly attributed to the effect of ultrasonic cavitation and turbulence on accelerating the collision of coix seed prolamins and breaking interactions, such as intermolecular hydrogen bonds of aggregates, during which the particle structure of the coix seed prolamins is also broken, thus reducing the particle size. This effect was more pronounced under higher-intensity (300–500 W) US conditions [44], [45]. In summary, HT + US can not only depolymerise coix seed prolamins aggregates but also break the intermolecular forces of coix seed prolamins to a certain extent and change their particle morphology, thus obtaining smaller molecular particles.

3.2. Effect of pretreatment on the thermodynamics of the enzymatic reaction of coix seed prolamins

3.2.1. Reaction rate constant (kin)

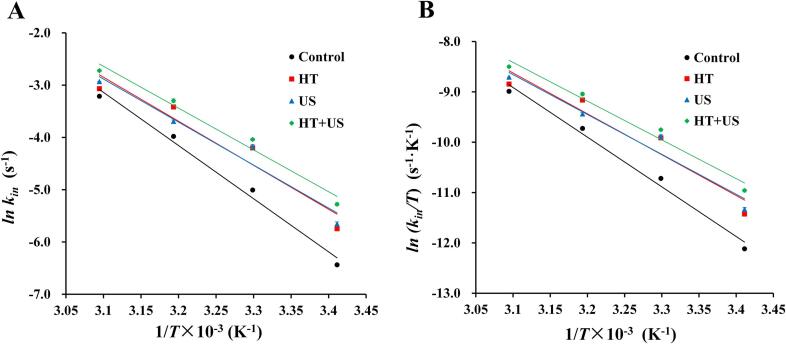

These findings suggest that heat and US pretreatment caused the denaturation of coix seed prolamins and led to changes in the efficiency of enzymatic digestion; however, the extent of these changes remains unclear. Fig. 3A–D show the relationship between ln(C∝-Ct) and reaction time t to investigate the effect of the different pretreatment processes on the rate constant kin of the enzymatic digestion reaction. As shown in Table 2, there was a good linear relationship between ln(C∝-Ct) and (R2 > 0.95 all), indicating that the enzymatic reactions of the four groups of coix seed prolamins conformed to the primary kinetic model. Table 2 summarises the rate constants kin the enzymatic reaction for each treatment group, and the results show that the rate constant kin increased gradually with increasing temperature in each group, mainly because the increase in temperature (20–50 °C) elevated the alkaline protease activity and increased the frequency of collision between alkaline protease and coix seed prolamins [46]. In addition, both HT and US treatments enhanced the rate constant kin of the enzymatic reaction, with the HT + US treatment showing more significant enhancement. In particular, at a temperature of 50 °C, the kin increased by 15.92%, 32.59%, and 63.23% in the HT, US, and HT + US groups, respectively, compared to the control group (Table 2). The occurrence of this phenomenon may be that pretreatment caused changes in the secondary and tertiary structures of coix seed prolamins, exposing more cleavage sites, making coix seed prolamins and alcalase easier to bind [47] and coix seed prolamins and alkaline proteases bind more readily. Compared with the HT group, HT + US pretreatment further enhanced the kin of the hydrolysis reaction (by 40.99%) at an enzymatic digestion temperature of 50 °C, indicating that the HT + US-treated coix seed prolamins were more susceptible to enzymatic digestion reactions, all of which relied on the full unfolding of the protein molecular structure [47].

Fig. 3.

Plot of ln(V∝-Vt) ∼ t during the enzymatic digestion of coix seed prolamins under the different pretreatment conditions: (A) control group, (B) heat treatment (HT) group, (C) ultrasound (US) group, and (D) HT + US group.

Table 2.

Reaction rate constants (kin) of the different protein pretreatment methods on coix seed prolamins at different temperatures.

| Type | Enzymolysis temperature (°C) | Fitting the curve | R2 of the fitted curve | kin (min−1) | kt (min−1) | kpre (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 20 | –0.0032x + 2.4918 | 0.985 | 0.0016 ± 0.0000Dc | – | – |

| 30 | –0.0067x + 2.462 | 0.9902 | 0.0067 ± 0.0001Cc | – | – | |

| 40 | –0.0328x + 2.3377 | 0.9714 | 0.0187 ± 0.0003Bd | – | – | |

| 50 | –0.0403x + 2.4797 | 0.9955 | 0.0402 ± 0.0002Ad | – | – | |

| HT | 20 | –0.0032x + 2.4918 | 0.985 | 0.0032 ± 0.0001Db | 0.0016 ± 0.0000D | 0.0016 ± 0.0001Db |

| 30 | –0.0150x + 2.4998 | 0.9904 | 0.0150 ± 0.0003Cb | 0.0067 ± 0.0001C | 0.0083 ± 0.0001Bb | |

| 40 | –0.0328x + 2.3377 | 0.9714 | 0.0328 ± 0.0006Bb | 0.0187 ± 0.0003B | 0.0141 ± 0.0003Ab | |

| 50 | –0.0466x + 2.4434 | 0.9848 | 0.0466 ± 0.001Ac | 0.0402 ± 0.0002A | 0.0063 ± 0.0010Cc | |

| US | 20 | –0.0035x + 2.4811 | 0.9817 | 0.0035 ± 0.0001Db | 0.0016 ± 0.0000D | 0.0019 ± 0.0001Db |

| 30 | –0.01545x + 2.486 | 0.9947 | 0.0154 ± 0.0005Cb | 0.0067 ± 0.0001C | 0.0088 ± 0.0006Bb | |

| 40 | –0.0249x + 2.4854 | 0.9999 | 0.0249 ± 0.0007Bc | 0.0187 ± 0.0003B | 0.0062 ± 0.0010Cc | |

| 50 | –0.0533x + 2.4744 | 0.9597 | 0.0533 ± 0.000Ab | 0.0402 ± 0.0002A | 0.0131 ± 0.0002Ab | |

| HT + US | 20 | –0.0051x + 2.4679 | 0.9942 | 0.0051 ± 0.0001 Da | 0.0016 ± 0.0000D | 0.0035 ± 0.0001 Da |

| 30 | –0.0176x + 2.4259 | 0.9775 | 0.0176 ± 0.0004Ca | 0.0067 ± 0.0001C | 0.0109 ± 0.0006Ca | |

| 40 | –0.037x + 2.3576 | 0.9924 | 0.037 ± 0.0013Ba | 0.0187 ± 0.0003B | 0.0183 ± 0.0010Ba | |

| 50 | –0.0657x + 2.4181 | 0.965 | 0.0657 ± 0.0014Aa | 0.0402 ± 0.0002A | 0.02545 ± 0.0012Aa |

Different capital letters in the upper-right corner of the same column in Table 2 indicate significant differences between sample points for the same pretreatment but different enzymatic digestion temperatures (P < 0.05). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between sample points for different pretreatments, but at the same enzymatic digestion temperatures (P < 0.05).

3.2.2. Thermodynamic parameters for reactions

According to the reaction rate constant kin, the slope of the fitted curve was obtained by plotting the “lnkin ∼ 1/T” diagram using the Arrhenius equation, which was used to characterise the apparent activation energy Ea. As shown in Fig. 4A and Table 3, the Ea for each group was <40 kJ/mol, which is lower than the Ea for most reactions (40–400 kJ/mol), indicating a faster reaction rate [46]. Compared to the control group, Ea was reduced by 17.21%, 19.08%, and 21.34% in the HT, US, and HT + US groups, respectively (P < 0.05), indicating that HT and US treatments significantly reduced the energy barrier for the reaction between coix seed prolamins and alkaline protease, allowing the enzymatic reaction to occur more quickly; the improvement was more pronounced with HT + US. The enthalpy of activation, entropy of activation, and Gibbs free energy of the enzymatic reactions were determined using the Eyring equation. ln (kin/T) vs. 1/T is shown in Fig. 4B. ΔH and ΔS were obtained from the slope and intercept of the fitted curve, respectively, while ΔG at each temperature was calculated using equation (8), the results of which are shown in Table 3. The ΔH was >0 in all groups, indicating that the enzymatic reaction was heat absorbing and that the pretreatment facilitated the reaction by reducing the enthalpy of activation of the enzymatic reaction. The decrease in ΔS indicates that the pretreatment resulted in a more uniform distribution of coix seed prolamins and alkaline protease during the reaction, which transformed the reaction from a disordered state to an ordered state and enhanced the affinity of the protein to the enzyme [48]. The fact that all of the ΔG values were greater than zero indicates that the hydrolysis reactions in each group were non-transient and non-spontaneous. Ea, ΔH, and ΔS were lower in the HT + US group than in the HT group, indicating that the US treatment further disrupted the non-covalent bonds of the heat-denatured coix seed prolamins and affected its ground state level, resulting in a higher enzymatic efficiency under the same enzymatic conditions [47].

Fig. 4.

Relationship curves for lnkin ∼ 1/T (A) and ln(kin/T) ∼ 1/T (B).

Table 3.

Thermodynamic parameters of the reactions of conventional and protein pretreatment enzymatic digestion.

| Type | Ea (kJ/mol) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔS (J/mol·K) |

ΔG (J/mol·K) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 °C | 30 °C | 40 °C | 50 °C | ||||

| Control | 10.17 ± 0.012a | 82.01 ± 0.104a | –17.42 ± 0.42a | 5.18 ± 0.11c | 5.36 ± 0.12c | 5.53 ± 0.12c | 5.70 ± 0.13c |

| HT | 8.42 ± 0.056b | 67.44 ± 0.46b | –60.18 ± 1.29b | 17.71 ± 0.38b | 18.31 ± 0.39b | 18.91 ± 0.40b | 19.51 ± 0.42b |

| US | 8.23 ± 0.12b | 65.89 ± 0.97b | –65.27 ± 2.95c | 19.20 ± 0.86a | 19.85 ± 0.89a | 20.51 ± 0.92a | 21.16 ± 0.95a |

| HT + US | 8.00 ± 0.035b | 63.98 ± 0.29c | –69.14 ± 1.08c | 20.33 ± 0.32a | 21.02 ± 0.33a | 21.71 ± 0.34a | 22.411 ± 0.35a |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between sample points for different lowercase letters in the upper-right corner of the data are shown in the same column as Table 3.

3.3. Mechanism of the protein modification technique of HT combined with US to promote the enzymatic reaction of coix seed prolamins

Based on the above discussion, the mechanism of action of the HT + US-assisted enzymatic digestion technique is proposed, as shown in Fig. 5. HT + US affects the structure and thermodynamic properties of the enzymatic reaction of coix seed prolamins and thus facilitates the enzymatic reaction, including three key elements: (1) HT induces the unfolding of coix seed prolamins molecules to expose more enzymatic sites while forming coix seed prolamins thermophoresis aggregates; (2) the cavitation effect of US caused further fragmentation of coix seed prolamins molecules, a further reduction in particle size, and higher intermolecular dispersion, whereas the dissociation of aggregates exposed more active sites (enzymatic cleavage sites); (3) broken coix seed prolamins molecules have a larger specific surface area, which can fully contact the protease and enhance the enzymatic reaction. The modified coix seed prolamins have a larger kin and lower Ea, ΔH, and ΔS during the enzymatic reaction, which is conducive to the high efficiency of the enzymatic reaction.

Fig. 5.

Mechanism of action underyling the HT + US-assisted enzymatic digestion technique.

3.4. Effects of pretreatment modifications on the properties of CHPs

3.4.1. Effects of pretreatment modifications on the hydrolysis of CHPs

The hydrolysis of the coix seed prolamins hydrolysate in the different pretreatment groups is shown in Fig. 6B. The rate of increase in hydrolysis in all groups was initially fast, followed by a slower rate, which was attributed to the concentration of the substrate protein before and after the reaction, in accordance with the kinetic model of enzymatic digestion. Compared to the single treatment group, there was a significant increase in the hydrolysis of coix seed prolamins at all time stages in the HT + US treatment, in descending order: HT + US > US > HT > control. DH at 120 min reached 34.43 ± 0.99%, 30.31 ± 1.14%, 28.06 ± 0.78%, and 24.90 ± 1.35%, respectively. This suggests that the molecular structure of coix seed prolamins obtained after HT + US treatment was more thoroughly unfolded, exposing more active sites for binding to alkaline proteases [16], [49]. Notably, protein molecules are prone to aggregation when treated with HT, and the formed protein aggregates do not facilitate the smooth access of enzyme molecules to the cleavage site [31]. However, the results of this study showed that the degree of hydrolysis of coix seed prolamins significantly increased after HT treatment, and the degree of hydrolysis further improved after HT + US treatment. These results indicate that the proenzymatic effect of protein modification due to HT treatment was stronger than the abrogation of the degree of hydrolysis due to protein aggregation. Moreover, ultrasonic treatment can alter this aggregation morphology through microfluidic, shear, and turbulent forces brought about by the cavitation effect [50], resulting in a higher level of HT-treated coix seed prolamins molecular structure stretching, and thus a greater degree of hydrolysis.

Fig. 6.

Amino acid composition of coix seed prolamins (A) (values are provided in g/100 g in the graph). Degree of hydrolysis (DH) (B) and IC50 values (C) of coix seed prolamins hydrolysate against α-glucosidase under different pretreatment conditions. Different lowercase letters for each data point in (C) indicate the significant differences between samples (P < 0.05).

3.4.2. Effects of pretreatment modifications on the molecular weight distribution of CHPs

The peptide molecular weight of the unmodified group of CHPs was mainly distributed in the range 500–2000 Da, accounting for 78.81% (Table 4), whereas that of the 180–500 Da fraction, which contained mainly dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides, was low (only 5.65%). After pretreatment, the content of the low-molecular-weight fractions increased in the 180–1000 Da range (0.82%, 16.55%, and 17.34% for HT, US, and HT + US, respectively) and decreased in the 1000–3000 Da range (1.89%, 14.20%, and 13.26% for HT, US, and HT + US, respectively). A decrease in the mean molecular weight (Mn, Mw, and Mz) reflected a shift from large to low molecular weight fractions of the enzymatic digest. Compared to the HT group, the combined HT + US treatment of 180–1000 Da was 1.16-times higher than that of the HT group, indicating that HT + US was more conducive to the hydrolysis and release of more small-molecule peptides from heated coix seed prolamins. Vilcacundo et al. [51] found that more low-molecular-weight peptides help to increase the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the enzymatic hydrolysate. This is mainly because the short peptide has a lower binding free energy with the α-glucosidase active site [52]. In summary, compared with the single treatment group, the HT + US treatment group was easier to obtain the hydrolysate of low molecular weight peptides, which may have a positive effect on the inhibition of α-glucosidase activity.

Table 4.

Molecular weight distribution and average molecular weights of CHPs under the different pretreatment conditions.

| Type | 180–500 Da | 500–1000 Da | 1000–2000 Da | 2000–3000 Da | >3000 Da | Mn (Da) | Mw (Da) | Mz (Da) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.65% | 38.35% | 40.46 | 10.23% | 5.32% | 985 | 1341 | 1957 |

| HT | 6.37% | 37.99% | 39.56% | 10.17% | 5.91% | 977 | 1366 | 2120 |

| US | 12.12% | 39.16% | 34.87% | 8.62% | 5.23% | 863 | 1272 | 2260 |

| HT + US | 11.37% | 40.26% | 35.51% | 8.46% | 4.39% | 866 | 1221 | 1853 |

Mn, number-average molecular weight; Mw, weight-average molecular weight; Mz, Z-average molecular weight.

3.4.3. Effects of pretreatment modifications on the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of CHPs

Coix seed prolamins contain abundant amino acids with hypoglycaemic activity, such as Glu, Leu, Pro, and Ala (Fig. 6A). These amino acid residues are common building blocks of highly active α-glucosidase-inhibitory peptides [9], [53]. To reflect the in vitro hypoglycaemic activity of CHPs, the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of CHPs was measured and the IC50 values were calculated. As shown in Fig. 6C, the IC50 values of hydrolysates for the control, HT, US, and HT + US groups were distributed as 15.30 ± 0.68 mg/mL, 12.44 ± 0.64 mg/mL, 10.17 ± 0.35 mg/mL, and 7.12 ± 0.33 mg/mL. After pretreatment, the IC50 values of all HT extracts decreased significantly (P < 0.05) compared to those of the control group, indicating that pretreatment enhanced the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of CHPs, with the greatest enhancement observed in the HT + US group (53.46% enhancement). In addition, HT + US further enhanced the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of HPCs compared to that of the HT group, which was associated with the disruption of the coix seed prolamins structure by US [16]. The above results showed that pretreatment increased the affinity of protein molecules for proteases [54] and that HT + US treatment further amplified the degree of modification of coix seed prolamins after a single treatment. Ultrasound treatment of the cavitation effect of US through oscillation caused chemical and physical changes in the liquid medium, resulting in the formation of tiny bubbles, expansion, and implosion on a microscopic scale to produce strong forces (including shear, impact, and heat), thus changing the protein structure [11] and declustering the thermal aggregates. This further enhanced the efficiency of hydrolysis and influenced the peptide distribution characteristics of the enzymatic digest, ultimately resulting in higher levels of α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. The experimental results are consistent with the results of molecular weight distribution.

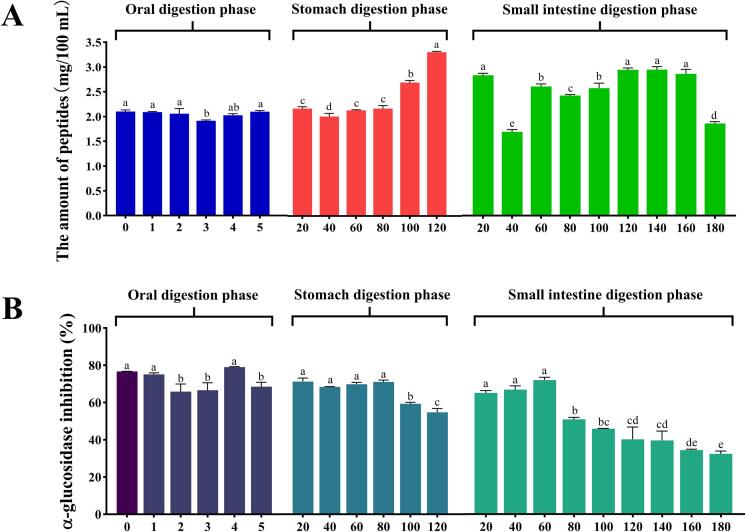

3.4.4. Bioavailability of CHPs

Based on the above findings, HT + US treatment was found to result in loosely structured coix seed prolamins, and by promoting the rate of the enzymatic reaction, a hydrolysate with excellent α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was obtained. However, studies have shown that after oral ingestion, α-glucosidase inhibiting peptides pass through digestive organs, such as the oral cavity, stomach, and small intestine, while being subjected to various digestive enzymes and the digestive environment, which may result in the breakage of some of the peptides and alter their structural integrity and α-glucosidase inhibiting activity [55]. The structure and stability of the enzymatic cleavage of peptide fractions during this process are not yet clear. Therefore, in this section, we focus on the bioavailability (peptide content and α-glucosidase inhibition activity) of the HT + US group of enzymes during the oral, gastric, and small intestine in vitro digestion phases, the results of which are shown in Fig. 7. The changes in the peptide content and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the coix seed prolamins hydrolysate at each stage of digestion are shown in Fig. 7A and B, respectively. During the oral digestion phase, there was no significant change (P > 0.05) in peptide content at any time point, except for a significant decrease (P < 0.05) at 3 min (Fig. 7A), which corresponded to a decrease in α-glucosidase inhibitory activity at 3 min (Fig. 7B). Due to the short oral digestion time, the protease reacted less with the peptides in the hydrolysate, resulting in a good retention of the peptide content and activity. During the gastric digestion phase, the peptide content gradually increased as the digestion time increased, reaching a maximum at 120 min after the end of digestion (3.31 ± 0.019 mg/100 mL) (Fig. 7A), indicating that a large number of small molecules of short peptides were formed during the gastric digestion phase from a portion of the long peptide chains after pepsin cleavage and acid hydrolysis (pH 3.0). The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the hydrolysate increased significantly (P < 0.05) during the first 80 min of the gastric digestion phase and decreased significantly (P > 0.05) after 100 and 120 min of digestion. α-Glucosidase inhibition at 120 min was 54.70 ± 2.10% (Fig. 7B). This trend in activity may occur because pre-digestion cleavage produces short peptides with amino acid residues, such as Leu, Phe, and Arg, and studies suggest that peptides with these amino acid residues may have better α-glucosidase inhibitory activity [56], [57]. In the later stages of digestion, a portion of the preproduced short peptides was further cleaved, releasing large amounts of free amino acids, which resulted in the loss of activity of these peptides and ultimately had a negative effect on the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the hydrolysate.

Fig. 7.

Peptide content (A) and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity (B) of coix seed prolamins hydrolysates during in vitro digestion. Different lowercase letters for each data point in the graph indicate the significant differences between samples (P < 0.05). Each digestion stage was used as a group for significant difference comparisons.

After entering the small intestine digestion phase, the peptide content showed a decreasing and then increasing trend, with a maximum peptide content of 2.41 ± 0.05 mg/100 mL at 140 min of intestinal digestion. Ultimately, the final digestion product had 0.72-times more peptide than the starting material (Fig. 7A). The change in α-glucosidase inhibitory activity during small intestine digestion was divided into two phases. The first phase gave rise to an increase in activity from 0 to 60 min, with the highest activity at 60 min (71.66 ± 1.50%) and a 31.01% increase in activity compared to the beginning phase of small intestine digestion (0 min). The second phase gave rise to a gradual decrease in activity over 60–180 min, reaching an activity of 32.23 ± 1.50% by the end of the small intestinal digestion (180 min), which was 57.97% of the activity of the initial raw material (0 min of oral digestion) (Fig. 7B). This may be due to further hydrolysis of a certain amount of oligopeptides produced by gastric digestion by trypsin during the early stages of digestion in the small intestine (0–40 min), resulting in a decrease in the peptide content. However, as the digestion reaction proceeded, more long-chain peptides were cleaved by trypsin, and smaller peptide fragments were formed, leading to a gradual increase in the content of subsequent peptides. At the same time, most bioactive peptides with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity were hydrolysed during this process, resulting in the loss of CHP activity. In contrast, the decrease in the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of CHPs slowed significantly during the later stages of digestion (140–180 min), and 32.23 ± 1.50% inhibitory activity was observed at 180 min. These results suggest that the vast majority of the final digestion products of CHPs were α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides with digestive enzyme resistance. As shown in Fig. 6A, the content of the coix seed prolamins Pro and Asp was high, whereas in a study on the conformational relationship of gastrointestinal resistance peptides, dipeptides containing Pro were the most stable for in vitro intestinal digestion, together with those containing Gly and Asp [58]. Because Pro contains a rigid cyclic imino group, it imposes unique conformational restrictions on the peptide chain, resulting in considerable resistance to metabolic proteases [59]. In addition, high levels of Arg and Glu (Fig. 6A) in the peptide segment inhibit trypsin digestion [60]. Therefore, we speculate that most of the in vitro digestion terminal products of CHPs are peptides with Pro, Arg, Gly, Asp and Glu.

In conclusion, the peptide content and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of coix seed prolamins hydrolysates were found to be affected to some extent by oral, gastric, and small intestinal digestion in this study. The oral phase was less influential and the small intestine digestion phase was more influential, while the continuous digestion process eventually affected bioavailability. However, the bioavailability of the coix seed prolamins hydrolysate was better maintained than that of the initial raw material. The peptide content and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the final product were 72.21% and 57.97% of those of the initial raw material, respectively. These results suggest that the coix seed prolamins hydrolysate has good bioavailability and is a promising oral hypoglycaemic product for the treatment of T2DM.

4. Conclusions

In this study, all three pretreatments (HT, US, HT + US) altered the structure of coix seed prolamins. HT + US exposed more hydrophobic groupings, smaller particle size and higher efficiency of enzymatic hydrolysate than the single treatment groups. This higher enzymatic efficiency was attributed to a significant reduction in the thermodynamic parameters Ea, ΔH and ΔS. The proportion of <1000 Da components, DH and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of CPHs in HT + US group were the highest compared to the other three treatment groups. Moreover, the peptide content and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of CPHs could be maintained at 72.21 % and 57.97 % of the starting material after in vitro digestion, indicating that bioavailability of CHPs was good. Therefore, HT + US can be substantial technology to improve hypoglycaemic activity of CHPs.

Funding

This work was supported by Research Team Project of Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province, China [grant number TD2020C003], Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural Reclamation University Academic Success, The Introduction of Talent Research Start-up Program [grant number XDB-2017-21], Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural Reclamation University Postgraduate Innovative Scientific Research Project [grant number YJSCX2022-Z04], and Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural Reclamation University Postgraduate Innovative Scientific Research Project [grant number YJSCX2022-Y43].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhiming Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Shu Zhang: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Lu Bai: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Huacheng Tang: Data curation. Guifang Zhang: Conceptualization, Supervision. Jiayu Zhang: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization. Weihong Meng: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization. Dongjie Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Wang R., Zhao H., Pan X., Orfila C., Lu W., Ma Y. Preparation of bioactive peptides with antidiabetic, antihypertensive, and antioxidant activities and identification of α‐glucosidase inhibitory peptides from soy protein. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019;7(5):1848–1856. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovic D., Piperidou A., Zografou I., Grassos H., Pittaras A., Manolis A. The growing epidemic of diabetes mellitus. CVP. 2020;18(2):104–109. doi: 10.2174/1570161117666190405165911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang S., Wang C., Zhang D. Ameliorative effect and mechanism of food-derived bioactive peptides against type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Food Sci. 2023;44(3):278–287. doi: 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20220225-220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mushtaq M., Gain A., Noor N., Masoodi F.A. Phenotypic and probiotic characterization of isolated LAB from Himalayan cheese (Karadi/Kalari) and effect of simulated gastrointestinal digestion on its bioactivity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021;149 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen P., Li L., Huo X., Qipao L., Zhang Y., Chen Z., Wang L. New angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory peptide from Coax prolamin and its influence on the gene expression of renin-angiotensin system in vein endothelial cells. J. Cereal Sci. 2020;96 doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2020.103099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L., Yuan J., Zhang X., Qipao Y. Protein composition analysis of Coax lacryma-jobi L. var. ma-yuen (Roman.) Stapf seeds. Prog. Mod. Biomed. 2012;12(23):4416–4432. [Google Scholar]

- 7.L. Meng, Adlay seed protein dependent on IKK/NF-κB pathway to control inflammation and improve insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus, Hei University of Technology, Hefei. 2018.

- 8.Watanabe M., Kato M., Ayugase J. Anti-diabetic effects of adlay protein in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2012;18(3):383–390. doi: 10.3136/fstr.18.383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z., Zhang S., Meng W., Zhang J., Zhang D. Food-derived α–glucosidase inhibitory peptides: structure-activity relationship, safety and bioavailability. Food Sci. 2022 doi: 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20220822-258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X., Yang Y., Wang Z. Structure characteristics of Coix seeds prolamins and physicochemical and mechanical properties of their films. J. Cereal Sci. 2018;79:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2017.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ulug S.K., Jahandideh F., Wu J. Novel technologies for the production of bioactive peptides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;108:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xi J., Yao L., Chen H. The effects of thermal treatments on the antigenicity and structural properties of soybean glycinin. J. Food Biochem. 2021;45(9):e13874. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Na X., Wang J., Ma W., Xu X., Zhong L., Wu C., Du M., Zhu B. Reduced adhesive force leading to enhanced thermal stability of soy protein particles by combined preheating and ultrasonic treatment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021;69(10):3015–3025. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morales R., Martínez K.D., Pizones Ruiz-Henestrosa V.M., Pilosof A.M.R. Modification of foaming properties of soy protein isolate by high ultrasound intensity: particle size effect. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015;26:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao C., Chu Z., Miao Z., Liu J., Liu J., Xu X., Wu Y., Qi B., Yan J. Ultrasound heat treatment effects on structure and acid-induced cold set gel properties of soybean protein isolate. Food Biosci. 2021;39 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2020.1008827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uluko H., Zhang S., Liu L., Tsakama M., Lu J., Lv J. Effects of thermal, microwave, and ultrasound pretreatments on antioxidative capacity of enzymatic milk protein concentrate hydrolysates. J. Funct. Foods. 2015;18:1138–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GB 5009.124, Determination of amino acid in foods, National Standard, China, 2016.

- 18.Resendiz-Vazquez J.A., Ulloa J.A., Urías-Silvas J.E., Bautista-Rosales P.U., Ramírez-Ramírez J.C., Rosas-Ulloa P., González-Torres L. Effect of high-intensity ultrasound on the technofunctional properties and structure of jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) seed protein isolate. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;37:436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie J., Du M., Shen M., Wu T., Lin L. Physico-chemical properties, antioxidant activities and angiotensin-I converting enzyme inhibitory of protein hydrolysates from Mung bean (Vigna radiate) Food Chem. 2019;270:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y.-Y., Wang C.-Y., Wang S.-T., Li Y.-Q., Mo H.-Z., He J.-X. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of tree peony (Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.) seed protein hydrolysates obtained with different proteases. Food Chemistry. 2021;345:128765. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma W., Wang J., Xu X., Qin L., Wu C., Du M. Ultrasound treatment improved the physicochemical characteristics of cod protein and enhanced the stability of oil-in-water emulsion. Food Res. Int. 2019;121:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian R., Feng J., Huang G., Tian B., Zhang Y., Jiang L., Sui X. Ultrasound driven conformational and physicochemical changes of soy protein hydrolysates. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;68 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma H., Huang L., Jia J., He R., Luo L., Zhu W. Effect of energy-gathered ultrasound on Alcalase. Ultrasonics Sonochem. 2011;18(1):419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qu W., Ma H., Liu B., He R., Pan Z., Abano E.E. Enzymolysis reaction kinetics and thermodynamics of defatted wheat germ protein with ultrasonic pretreatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20(6):1408–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swati G., Haldar S., Ganguly A., Chatterjee P.K. Investigations on the kinetics and thermodynamics of dilute acid hydrolysis of Parthenium hysterophorus L. substrate. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;229:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2013.05.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Q., Tian Y. α-Glucosidase and dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitory activity and peptide composition of Porphyra yezoensis protein hydrolysate. Food Sci. 2020;41(24):110–116. doi: 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20191014-114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B., Yu Z., Li Q., Liu F., Zhong F. Effects of ssimulated gastrointestinal ddigestion on antioxidant activity of sheepskin collagen peptides and their digestive protection. Food Sci. 2022;43(7):128–138. doi: 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20210204-090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin L.-J., Hsiao E.S.L., Tseng H.-S., Chung M.-C., Chua A.C.N., Kuo M.-E., Tzen J.T.C. Molecular Cloning, Mass Spectrometric Identification, and Nutritional Evaluation of 10 Coixins in Adlay (Coix lachryma-jobi L.) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57(22):10916–10921. doi: 10.1021/jf903025n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie H. Central South University of Forestry and Technology; Changsha: 2021. The research on the construction and characteristics of astaxanthin complex nanoparticles based on coixin. https://doi.org/10.27662/d.cnki.gznlc.2021.000314. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Y., Li F., Carvajal M.T., Harris M.T. Interactions between bovine serum albumin and alginate: An evaluation of alginate as protein carrier. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;332(2):345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu H., Li-Chan E.C.Y., Wan L., Tian M., Pan S. The effect of high intensity ultrasonic pre-treatment on the properties of soybean protein isolate gel induced by calcium sulfate. Food Hydrocoll. 2013;32(2):303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie Y., Wang J., Wang Y., Wu D., Liang D., Ye H., Cai Z., Ma M., Geng F. Effects of high-intensity ultrasonic (HIU) treatment on the functional properties and assemblage structure of egg yolk. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;60 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ai M., Tang T., Zhou L., Ling Z., Guo S., Jiang A. Effects of different proteases on the emulsifying capacity, rheological and structure characteristics of preserved egg white hydrolysates. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;87:933–942. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu H., Zhang H., Liu Q., Chen Q., Kong B. Solubilization and stable dispersion of myofibrillar proteins in water through the destruction and inhibition of the assembly of filaments using high-intensity ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;67 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu Y., Fu S., Wu C., Qi B., Teng F., Wang Z., Li Y., Jiang L. The investigation of protein flexibility of various soybean cultivars in relation to physicochemical and conformational properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;103 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pezeshk S., Rezaei M., Hosseini H., Abdollahi M. Impact of pH-shift processing combined with ultrasonication on structural and functional properties of proteins isolated from rainbow trout by-products. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;118 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xue F., Zhu C., Liu F., Wang S., Liu H., Li C. Effects of high-intensity ultrasound treatment on functional properties of plum (Pruni domesticae semen) seed protein isolate. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018;98(15):5690–5699. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.9116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao Y., Hao X., Hu Y., Zhou N., Ma Q., Zou L., Yao Y. Modification of the functional properties of chickpea proteins by ultrasonication treatment and alleviation of malnutrition in rat. Food Funct. 2023;14(3):1773–1784. doi: 10.1039/d2fo02492f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J., Zhu B., Dou J., Ning Y., Wang H., Huang Y., Li Y., Qi B., Jiang L. pH and ultrasound driven structure-function relationships of soy protein hydrolysate. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023;85:103324. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y., Wang Z., Handa C.L., Xu J. Effects of ultrasound pre-treatment on the structure of β-conglycinin and glycinin and the antioxidant activity of their hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2017;218:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao H., Sun R., Shi J., Li M., Guan X., Liu J., Huang K., Zhang Y. Effect of ultrasonic on the structure and quality characteristics of quinoa protein oxidation aggregates. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;77 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang H., Li X., Wang J., Wu W., Guo R., Yu Q., Zhang C. Recent progress in prolamines as a food nutrient carrier. Food Sci. 2019;40(19):318–325. doi: 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-20181008-049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu H., Pan J., Dabbour M., Kumah Mintah B., Chen W., Yang F., Zhang Z., Cheng Y.u., Dai C., He R., Ma H. Synergistic effects of pH shift and heat treatment on solubility, physicochemical and structural properties, and lysinoalanine formation in silkworm pupa protein isolates. Food Res. Int. 2023;165:112554. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang L., Wang J., Li Y., Wang Z., Liang J., Wang R., Chen Y., Ma W., Qi B., Zhang M. Effects of ultrasound on the structure and physical properties of black bean protein isolates. Food Res. Int. 2014;62:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen X., Fang T., Gao F., Guo M. Effects of ultrasound treatment on physicochemical and emulsifying properties of whey proteins pre-and post-thermal aggregation. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;63:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayim I., Ma H., Alenyorege E.A., Ali Z., Donkor P.O. Influence of ultrasound pretreatment on enzymolysis kinetics and thermodynamics of sodium hydroxide extracted proteins from tea residue. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018;55:1037–1046. doi: 10.1007/s13197-017-3017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdualrahman M.A., Ma H., Zhou C., Yagoub A.E., Hu J., Yang X. Thermal and single frequency counter-current ultrasound pretreatments of sodium caseinate: enzymolysis kinetics and thermodynamics, amino acids composition, molecular weight distribution and antioxidant peptides. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016;96(15):4861–4873. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wali A., Ma H., Hayat K., Ren X., Ali Z., Duan Y., Rashid M.T. Enzymolysis reaction kinetics and thermodynamics of rapeseed protein with sequential dual-frequency ultrasound pretreatment. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018;53(1):72–80. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fadimu G.J., Farahnaky A., Gill H., Truong T. Influence of ultrasonic pretreatment on structural properties and biological activities of lupin protein hydrolysate. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022;57(3):1729–1738. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.15549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu A., Li L. Effect mechanism of ultrasound pretreatment on fibrillation kinetics, physicochemical properties and structure characteristics of soy protein isolate nanofibrils. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105741.). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vilcacundo R., Martínez-Villaluenga C., Hernández-Ledesma B. Release of dipeptidyl peptidase IV, α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides from quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) during in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion. J. Funct. Foods. 2017;35:531–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.06.024.). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ibrahim M.A., Bester M.J., Neitz A.W., Gaspar A.R.M. Rational in silico design of novel α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides and in vitro evaluation of promising candidates. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;107:234–242. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ibrahim M.A., Bester M.J., Neitz A.W., Gaspar A.R. Structural properties of bioactive peptides with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2018;91(2):370–379. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fadimu G.J., Gill H., Farahnaky A., Truong T. Improving the enzymolysis efficiency of lupin protein by ultrasound pretreatment: Effect on antihypertensive, antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of the hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2022;383 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang B., Xie N., Li B. Influence of peptide characteristics on their stability, intestinal transport, and in vitro bioavailability: A review. J. Food Biochem. 2019;43(1):e12571. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gallego M., Mora L., Toldrá F. The relevance of dipeptides and tripeptides in the bioactivity and taste of dry-cured ham. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2019;1:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s43014-019-0002-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu W., Li H., Wen Y., Liu Y., Wang J., Sun B. Molecular mechanism for the α-glucosidase inhibitory effect of wheat germ peptides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021;69(50):15231–15239. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c06098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foltz M., Van Buren L., Klaffke W., Duchateau G.S. Modeling of the relationship between dipeptide structure and dipeptide stability, permeability, and ACE inhibitory activity. J. Food Sci. 2009;74(7):H243–H251. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vanhoof G., Goossens F., De Meester I., Hendriks D., Scharpé S. Proline motifs in peptides and their biological processing. FASEB J. 1995;9(9):736–744. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.9.7601338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Šlechtová T., Gilar M., Kalíková K., Tesařová E. Insight into trypsin miscleavage: comparison of kinetic constants of problematic peptide sequences. Anal. Chem. 2015;87(15):7636–7643. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]