Abstract

The physical and chemical properties of synthetic DNA have transformed this prototypical biopolymer into a versatile nanoscale building block material in the form of DNA nanotechnology. DNA nanotechnology is, in turn, providing unprecedented precision bioengineering for numerous biomedical applications at the nanoscale including next generation immune-modulatory materials, vectors for targeted delivery of nucleic acids, drugs, and contrast agents, intelligent sensors for diagnostics, and theranostics, which combines several of these functionalities into a single construct. Assembling a DNA nanostructure to be programmed with a specific number of targeting moieties on its surface to imbue it with concomitant cellular uptake and retention capabilities along with carrying a specific therapeutic dose is now eminently feasible due to the extraordinary self-assembling properties and high formation efficiency of these materials. However, what remains still only partially addressed is how exactly this class of materials is taken up into cells in both the native state and as targeted or chemically facilitated, along with how stable they are inside the cellular cytosol and other cellular organelles. In this minireview, we summarize what is currently reported in the literature about how (i) DNA nanostructures are taken up into cells along with (ii) what is understood about their subsequent stability in the complex multi-organelle environment of the cellular milieu along with biological fluids in general. This allows us to highlight the many challenges that still remain to overcome in understanding DNA nanostructure–cellular interactions in order to fully translate these exciting new materials.

Introduction

The importance of formulating a predictable relationship between the properties of DNA nanostructures (DNA NS or NS) and their structural integrity, along with their intracellular behavior, is emphasized in their now frequently demonstrated potential as designer nanoscale platforms for targeted medical interventions.1–4 DNA NS have shown potential superiority in delivering pharmaco-chemical or nucleic acid therapeutics against several diseases in comparison to current drugs. The targeted delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs via DNA NS instead of direct intravenous administration can dramatically reduce off-target toxicity.5–8 Their versatility is highlighted by examples where thrombin-DNA aptamer chemistry has been leveraged in DNA platforms to, on one hand, induce targeted damage in the vasculature of tumor sites in Chinese hamster animal models9 and, on the other hand, prevent thrombosis during hemodialysis by sequestering protein activity from plasma.10,11 In another example of this material’s versatility, RNA-targeting protein RNAse A bound to DNA platforms via sulfo-SMCC protein–DNA chemistry was able to induce cell death in cancer MCF-7 cells.12 Optimizing the display of ligands,13–16 aptamers,17–19 and antigens20,21 on the NS surface to match the spatial pattern of membrane receptors improves the therapeutic efficacy, particularly the B-cell recognition, of engineered DNA NS as vaccines,19,20 cancer treatment, or immunogenic treatments. In addition to interfacing with cells, DNA NS can potentially be programmed to remain inactive until the right biological signal stimulates a mechano-chemical actuation; these cues can include that originating from light-induced antigen binding,22 aptamer-protein binding,9,23 antigen-ligand binding,24 and many others that are yet to be incorporated into prototypical biomedical systems.25,26 Combining imaging with therapeutic application is also possible due to the multiplexed functionality of DNA NS.27 Alongside performing the aforementioned delivery functionalities, the off-target immune response elicited by DNA NS is often non-toxic up to considerably high doses.28 Most excitingly, delivering genes for potential Cas9-mediated genome editing is possible using the superior structural properties of DNA NS.29

As synthetic DNA-based therapeutic NS mature and start being prototyped for the aforementioned applications, confident prediction of the stability and structural integrity of a DNA NS inside the body at any point in time persists as a significant challenge. There are general observations that suggest that – depending on the structural and/or functional “complexity” of a DNA NS – it could remain “stable” up to a certain number of hours within the extracellular environment, serum, blood, and the cytosol (vide infra). Whole animal delivery studies show that the shape of a DNA NS imparts certain renal targeting advantages over unfolded plasmid DNA which can be leveraged for renal intervention.30 Collectively processing such observations to formulate a framework that could guide future design criteria has yet to be done and this is something that is crucial prior to clinical trial scrutiny.

The complexity of the journey that a DNA NS will undergo for delivery into a cell should be appreciated. Using the context of targeting a solid tumor in an animal model for illustration, the NS will most likely be first administered as a bolus or by slower infusion in the blood stream, intramuscularly, to the lymphatic system, or even in a transdermal manner. Assuming a targeting moiety is attached to the NS, such as an arginylglycylaspartic acid (RGD) peptide motif or folic acid targeting tumors displaying integrin or folic acid receptors, respectively, the NS will then selectively bind to the tumor cell surfaces.31 The DNA NS then are usually taken up into the cells by some form of endocytosis that in this case is most likely receptor mediated, but which for untargeted NS may be a more non-specific mechanism, these are reviewed in ref. 2 and 32. Now once inside the endolysosomal system and entrapped in endosomal vesicles, the DNA NS need to escape this harsh environment to access the cytosol and subsequently enter the nucleus or mitochondria if those organelles are the required targets of the intervention. Fig. 1 provides an excellent overview of the interactions occurring during the endocytic uptake of a DNA nanorod into H1299 (transformed lung carcinoma epithelial) cells as followed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which, in this case, also shows the hydrolysis of the structure after being present in acidic lysosomes over 24 h.33 Suffice to say that DNA NS have already been shown to discreetly access these different components of a mammalian cell – they can robustly match the spatial pattern and maximize their interaction with membrane receptors,20,21 undergo endocytosis to access intracellular space,34,35 and make deliveries into the cytosol and even the nucleus.12,35 How one DNA NS accomplishes all this while another different assembly architecture does not, how they can be engineered specifically enough, and the fundamental rules that determine a given intracellular pathway remain poorly understood.

Fig. 1.

DNA nanoparticle endocytosis into cells. Visualization of the uptake and endocytic pathway in H1299 cells of a rod-shaped DNA NS labeled with spherical gold nanoparticles which allow for tracking via TEM imaging. (a) Schematic and representative electron microscopy image of the DNA nanorod with 6 gold nanospheres displayed along the length of the DNA NS. (b) Schematic representation of the uptake mechanism hypothesized for DNA nanorods through the four stages of endocytosis. (c–f) Step-wise representation of the transport of gold-labeled DNA nanorods from extracellular membrane to lysosomes where it can be seen that the nanorod has disintegrated (clustered instead of linearly arranged gold spheres). Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref. 33 Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

Herein, a progress report consolidating the knowledge gained so far in elucidating the uptake mechanisms and stability of DNA NS in cellular and biological environments is presented. The DNA NS discussed here constitute 10–200 nanometer (nm) structures, or sometimes larger, as prepared by self-assembly of a pool of single stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecules via thermal annealing. DNA materials of this kind are typically designed based on two overarching strategies, namely, DNA origami36 and complete ssDNA assembly.37,38 For more information on the DNA materials themselves and their properties, along with potential applications in the current context, the interested reader is referred to ref. 1, 4, 39, and 40. Of particular interest are DNA NS that are examined for their innate cellular uptake abilities rather than when coupled with transfection agents4 such as chitosan,41 gold nanoparticles,42 condensing agents,7,43 or viral capsids.44 These examples along with delivery of materials that are electroporated into cells, while valuable, are outside the current scope. A more extensive discussion on the in vivo implications of DNA NS is also reviewed recently.1,45 The context of interest being examined is that of understanding which properties of DNA NS facilitate interaction with the cell membrane or otherwise affect the rest of the internalization path at this stage of their development.

Uptake of DNA NS into mammalian cells

Tables 1 and 2 summarize published reports describing the state of the investigation into the uptake properties of DNA nanoparticles. Table 1 focuses on DNA NS applied in different therapeutic contexts while Table 2 summarizes studies geared towards fundamental understanding and typically do not contain DNA NS that were functionally modified with a drug or protein. The uptake studies listed in Table 1 fall under the context of three overarching therapeutic applications, namely, immune-modulation, nucleic acid delivery, and pharmacochemical delivery. For each study, the type of DNA NS studied, cell type, displayed targeting moieties, dosage, and the tracked end-point are identified. Abbreviations of cell types are further defined in the table’s footnotes. Predominantly, the DNA tetrahedron (~10 nm) is used in these studies but over the last several years larger DNA origami structures (~100 nm) have become more common, likely due to the availability of more sites to couple biocompatible signaling molecules. We observed that the display of targeting antigens or ligands on the surface of the DNA NS is not a requirement for uptake and that DNA NS with21,31,46,47 and without5,34,48,49 targeting moieties have been reported to be internalized by cells. The spatial arrangement of antigens on the DNA NS does, however, perform significantly better in immunostimulatory applications since it leverages B/T-cell receptor antigen pattern recognition and macrophage functionality.20,21,50

Table 1.

Overview of application-specific studies reporting uptake of DNA nanostructure by mammalian cell and animal models

| Application | DNA nanostructure (size nm/mass kDa) | Cell type primary/transformed | Targeting moiety on DNA/drug or Protein | Dosage (in ×104 cells)a | Tracked end-point | Cytotoxicityb | Ref. (year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune-stimulation: | Rectangle reconfigured as tube (90 nm) | BMDC, mice | OVA, gp100, and Adpgk peptides | 2 nM in 3× | Endosome | 98 (2021) | |

| Octahedron (50 nm), tube (400 nm/4 MDa), nanorod (89 nm/4 MDa) | 3T3, HEK-293, H441 | None | 1 nM in 1× | — | None >7 d | 79 (2014) | |

| Disk (80 nm/4 MDa) | RAW264.7 | CpG | 10–1000 nM in 2× | Endosome | None >5 h | 21 (2022) | |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | RAW264.7 | CpG | 100 nM in 50× | — | None >24 h | 99 (2011) | |

| Rectangle (90 nm/4 MDa) | RAW264.7, THP-1 | IgG | 1 μM DNA in 3× | — | — | 50 (2021) | |

| Tube (80 nm/4 MDa) | Splenic macrophages | CpG, CpG PTO, CpG chimera | 2.4 nM 50 μL DNA in 40× | Lysosomes | None >18 h | 72 (2011) | |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | RAW 264.7, primary dendritic cells | CpG, streptavidin | 62.5 nM in 2.5×-25× | Lysosomes | — | 53 (2012) | |

| Nucleic acid delivery: | Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | HeLa | siRNA | 10–80 nM in 15× | — | None >24 h | 31 (2012) |

| Tube (27 nm/140 kDa) | HeLa | None | 10 nM | Endosome | None >24 h | 100 (2014) | |

| Rectangular prism (10 nm/160 kDa) | HeLa | DNA trigger strand | 75 nM in 1× | — | None >72 h | 26 (2016) | |

| Cube (7 nm/82 kDa) | HeLa, primary B-lymphocytes | DNA trigger strand | 250 pmole in 10× | — | — | 101 (2014) | |

| Rectangle, tube (32 nm–64 nm) | DMS53, NSCLC | siRNA | 16.7 nM in 1× | Cytoplasm | None >8 h | 46 and 47 (2020) | |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | Mice | SARS-CoV-2 aptamer | 500 nM 100 μL inj. | — | None >12 h | 19 (2022) | |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | Mice | TGF-β1 mRNA | 1 μM 200 μL inj. | Liver targeting | None >24 h | 102 (2022) | |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | Mice | BACE1 aptamer | 1 μM 100 μL inj. | Cross BBB | — | 18 (2022) | |

| Pharmaco-chemical/drug: | Triangle (120 nm), rod (400 nm) | MCF-7 | None/DOX | 50–100 μM | — | None >48 h | 6 (2012) |

| Disk (62 nm/4 MDa), donut (44 nm/4 MDa), sphere (62 nm/4 MDa) | MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 | MUC1 aptamer/DOX | 1 nM in 0.3× | — | None >48 h | 5 (2022) | |

| Cross, rectangle, triangle (50 nm/4 MDa) | MDA-MB-231 | None/DOX | 1.25–5 nM in 0.3× | Lysosomes | — | 8 (2018) | |

| T-nanotube, S-nanotube (100 nm/4 MDa) | MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and MCF-7 | None/DOX | 50–15 000 nM Dox in 20× | Endosomes | — | 103 (2012) | |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | U87MG | Tumor penetrating peptide/DOX | 50 nM in 0.4× | — | — | 104 (2016) | |

| 3D DNA NS (100 nm | MCF-7, mice | MUC1 aptamer | 4 μM in 10× | — | — | 105 (2022) | |

| Protein delivery: | Rectangle reconfigured as a tube (90 nm/4 MDa) | HUVEC, mice | AS1411 aptamer/thrombin | — | — | None >72 h | 9 (2018) |

| Rectangle (90 nm/4 MDa) | MCF-7 | MUC1 aptamer/RnaseA | 1 nM | — | None >48 h | 12 (2019) |

Abbreviations: Adpgk = neoantigen peptide derived from MC-38 colon carcinoma, CpG = unmethylated cytosine–guanine dinucleotide motifs, DOX = doxorubicin, gp100 = peptide vaccine from melanoma antigen glycoprotein, MUC1 = mucin 1 protein overexpressed in malignant cells, OVA = ovalbumin peptide epitope presented by class I major histocompatibility complex, PTO = kinase substrate, siRNA = small interfering RNA, inj = tail vein injection, BBB = blood brain barrier. Cell types: BMDC = bone marrow derived dendritic cells; COS = monkey kidney fibroblast cells; DMS53 = human small cell lung cancer cells; H1299 = human non-small cell lung cancer cells; H441 = human distal lung epithelial cells; HEK293 = human embryonic epithelial kidney cells; HeLa = human cervical cancer cells; Huh7 = human epithelial cancer cells; HUVEC = human umbilical vein endothelial cells; MCF-7 = human breast cancer cells; MDA-MB = human epithelial breast cancer cells; NSCLC = human non-small cell lung cancer cells; NIH-3T3 = mouse embryonic fibroblast cells; RAW264.7 = mouse macrophage cells; THP-1 = human leukemia monocytic cells; U87MG = human glioblastoma.

Dosage is given as ×104 cells. For example, first entry represents 3 × 104 cells.

Cytotoxicity in the presence of bare DNA NS only (not the treatment in some cases).

Table 2.

Studies focused on DNA nanostructure uptake in mammalian cells

| DNA nanostructure (size nm/mass kDa) | Cell type primary/transformed | Targeting moiety displayed on the DNA NS | Dosage (in ×104 cells)a | Tracked end-point | Cytotoxicityc | Ref. (year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thin rod, thick rod, small ring, large ring, barrel, octahedron, block (50 nm-400 nm/4 MDa) | BDMC, HEK293, HUVEC | None | 1 nM in 10× | None >12 h | 106 (2018) | |

| Octahedron (11 nm/160 kDa) | COS fibroblasts | None | 2 μg mL−1 in 100× | Cytoplasm, endosomes | — | 34 (2016) |

| Tetrahedral nanocage (8 nm/82 kDa), octahedral nanocage (11 nm/180 kDa), chainmail (25 nm/180 kDa), square box (35 nm), rectangle (80 nm/4 MDa) | COS-7 | None | 6 μg ml−1 in 100× | Lysosomes | — | 69 (2019) |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | HEK | None | 1 μg in 30× | Cytoplasm | None >72 h | 49 (2011) |

| Cube, tetrahedron nanocages (10 nm) | HeLa | None | 150 nM | Lysosome, mitochondria | — | 52 (2019) |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | HeLa | None | 150 nM | None >3 h | 55 (2021) | |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | HeLa, COS-7 | None | 100 nM in 8× | Lysosome, nucleus | — | 35 (2014) |

| Small tetrahedron (11 nm), large tetrahedron (47 nm), small rod (32 nm), large rod (127 nm) | HeLa, H1299, DMS53 | None | 250 nM | Lysosome | None >1 h | 33 (2018) |

| 6-Helix bundle (6 nm × 7 nm) | HepG2, Huh7 | Oligolysine | 50 nM in 10× | Endosome, lysosome, cytoplasm | None >24 h | 48 (2021) |

| Concave-DNA origami structure (34 nm/4 MDa) | HeLa, HepG2, MCF-7, DC2.4 | pH low insertion peptideb | 15 nM in 10× | Endoplasmic reticulum | — | 107 (2022) |

| Icosahedron (10 nm/160 kDa) | Caenorhabditis elegans | 10 kDa FITC-dextran | 12–15 μM | Endosome | — | 108 (2011) |

| Tube (400 nm/4 MDa) | NIH-3T3 | None | 10 nM | Lysosome | — | 109 (2016) |

| Tetrahedron (7 nm/82 kDa) | RAW264.7 | None | 10 nM in 2.5× | Cytoplasm | None >6 h | 110 (2013) |

Cell types: BMDC = bone marrow derived dendritic cells; COS = monkey kidney fibroblast cells; DMS53 = human small cell lung cancer cells; H1299 = human non-small cell lung cancer cells; HEK293 = human embryonic epithelial kidney cells; HeLa = human cervical cancer cells; Huh7 = human epithelial cancer cells; HUVEC = human umbilical vein endothelial cells; DC2.4 = immortalized murine dendritic cells; NIH-3T3 = mouse embryonic fibroblast cells; RAW264.7 = mouse macrophage cells.

Dosage is given as ×104 cells. For example, first entry represents 10 × 104 cells (or 105 cells).

The different cells were first treated with artificial membrane receptor (AMR) that enabled uptake and targeting of the DNA NS.

Cytotoxicity in the presence of bare DNA NS only (not the treatment in some cases).

It is generally agreed that the primary mechanism of NS uptake into cells without active delivery modalities such as electroporation is almost universally that of endocytosis. Indeed, almost all the studies listed in Tables 1 and 2 directly or indirectly align with this consensus. The most common mechanism of uptake was found to be receptor-mediated endocytosis wherein the DNA NS interacted with membrane receptors and are internalized via endocytic vesicles (Fig. 1). A clear uptake mechanism explaining the efficiency of internalization or the interaction of DNA NS with membrane receptors is still not fully elucidated. Colocalization of the fluorescence of dyes (typically cyanine 5 – Cy5) coupled to DNA NS prototypes and cell lysosomal staining suggests that the structures reach the lysosomes in a NS-dependent timeframe.51 The DNA NS in lysosomes may or may not be fully intact; some clarity is needed as to what extent the Cy5 fluorescence colocalization within lysosomes is attributed to stable DNA NS.32,52 Macrophage cells such as RAW264.7 (established from a tumor in a male mouse induced with the Abelson murine leukemia virus) are known to perform phagocytosis on what the human body would normally consider foreign material, but in the case of DNA NS, the distinction between their endo- and phagocytosis and other uptake mechanisms by these cells is yet to be studied further.50 Preliminary studies have tracked certain DNA NS in endosomes and even lysosomes of RAW264.7 cells through fluorescence colocalization studies.21,53

The shape or structural complexity of DNA NS is a factor that modulates the timeframes in which the structures enter the cell and collect in the lysosomes before complete degradation.33 While it is not immediately evident from Tables 1 and 2 how the physicochemical properties of DNA NS determine which endocytic pathway they might trigger (since 7–400 nm large rods, tubes, polyhedra, disks, and other shapes are amenable to uptake), preliminary experimental and computational analysis suggest that the vertices of polygonal DNA NS offer the path of least resistance in terms of interfacing with the negatively charged cell membrane for endocytosis.54,55 More recent work by Bhatia and co-workers systematically corroborates that tetrahedron endocytosis occurs more readily than for other larger polyhedral structures, and the size of the tetrahedral shape (14.3 nm “medium” size versus “large” 32 nm or “small” 11 nm) can affect its endocytic efficacy.56 Cancerous cell lines have higher uptake propensity for DNA NS than non-cancerous. The implication of understanding the role of NS shape in uptake can be considered crucial to formalizing the physical factors of DNA NS that determine their cellular interaction.

Stability of DNA NS in biological environments

Over the last decade, considerable effort by the scientific community has helped decipher the preliminary structural stability of DNA nanoparticles in some extracellular in vitro-related environments; knowledge of this kind helps overcome one of the primary barriers to the development of any translational biomedical products. These environments include cell culture media, blood sera (most commonly fetal bovine serum – FBS), and various buffers with salt and pH conditions mimicking what could be experienced in vivo for mammalian cells and the body, as summarized in Tables 3 and 4. In biological environments, the integrity of DNA NS can be rapidly compromised through attacks by various DNA nucleases (DNases), low divalent cation concentrations (common to nearly all physiological environments), and large variations in ionic strength and pH, particularly upon uptake into cells or ingestion into the stomach with its inherently acidic environment which is naturally hydrolytic.39,40 For eventual therapeutic applications, a DNA NS must be sufficiently robust to maintain structural integrity long enough to enter the body, travel to a target of interest, and undergo any desired interactions, such as uptake, macrophage capture, or viral capture.57,58 The timescales for such interactions range from minutes to tens of hours, though most applications require lifetimes on the order of several hours in the body.

Table 3.

Stability of DNA nanostructures in serum

| Environment | DNA nanostructure | Dimensions/mass | Modifications for stability | Reported stability | Reporting | Notes | Ref. (year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media/buffers with serum | |||||||

| DMEM-Mg with 10% FBS, 37 °C | ssDNA | 63, 96 nt/24, 36 kDa | ± HEG termination | ssDNA τ1/2: 0.8–4 h | PAGE denat. | Cy dye position: 3′ > int > 5′ | 52 (2019) |

| Tetrahedron (Tet.) | 7 nm/82 kDa | 3′, int., 5′ Cy dyes | Tet. τ1/2: 7–8 h | PAGE | HEG termination > native | ||

| Cube | 7 nm/124 kDa | Cube τ1/2: 3.5–5.5 h | Tet. ⪢ cube > ssDNA | ||||

| DMEM with 10% FBS, 37 °C | Disc origami | 62 nm dia./4 MDa | — | Disc <12 h | AGE | No degradation observed. | 5 (2022) |

| Donut origami | 44 nm dia./4 MDa | Donut <24 h | |||||

| Sphere origami | 42 nm dia./4 MDa | Sphere <12 h | |||||

| RPMI with 10% FBS, 37 °C | Octahedron origami | 45 nm dia./4 MDa | — | <24 h | AGE, TEM | No degradation observed. | 79 (2014) |

| DMEM with 10% FBS, 37 °C | Triangular prism | 10 nm/160 kDa | PS | τ1/2: 2–7 h (decreased w/PS) | AGE, PAGE, denat. PAGE | While PS decreased structure stability, single strand stability increased | 111 (2014) |

| 10% FBS, 37 °C | Tetrahedron (Tet.) | 7 nm/82 kDa | Enzymatic ligation | FBS: Tet. >24 h, DS ~4 h | AGE | Tet. >3× more stable than DS | 78 (2009) |

| Linear dsDNA (DS) | 63 bp/41 kDa | DNase: Tet. <10 min, DS ~3 min | |||||

| 50% FBS, 37 °C | Tetrahedron (Tet.) | 7 nm/82 kDa | — | Tet. <24 h | AGE | Tet. >4× more stable than DS | 99 (2011) |

| Duplex | 63 bp/41 kDa | Duplex <4 h | |||||

| DMEM with 10% FBS, 37 °C | Triangular prism ssDNA | 10 nm/160 kDa 63 bp/41 kDa | HEG ended DNA oligos | Prism: ~2 h, HEG prism: >24 h ssDNA: <1 h, HEG ssDNA: 28 h | PAGE | HEG >10× increased stability | 67 (2013) |

| RPMI with 10% FBS, 37 °C | Barrel origami | 60 nm dia./4 MDa | Oligolysine (K4–K20) | For native/K10/K10: P5k in FBS: τ1/2 = 5 min/55 min/36 h | AGE, TEM | Best nuclease stability with K10:P5k | 65 (2017) |

| PEG oligolysine (K10:P1k–10k) | |||||||

| 10% FBS, 37 °C | Tetrahedron (Tet.) | 7 nm/82 kDa | Enzymatic ligation (Tet., Oct.) | Native structures: τ1/2 ~12 h | AGE | Tet. most stable structure | 69 (2019) |

| Octahedron (Oct.) | 11 nm/180 kDa | Click-chemistry ligation (CM) | Ligated structures: τ1/2 ~36 h | ||||

| Chainmail rod (CM) | 25 nm/180 kDa | Native origami: τ1/2 ~24 h | |||||

| Rectangular origami | 90 × 60 nm/4 MDa | ||||||

| 10% FBS in TAE + Mg, 37 °C | Pyramid | 10 nm/94 kDa | 2′-Fluoro-RNA (2F) | Native structures: <1 h | AGE | >24× improved stability with modified backbones | 71 (2019) |

| Triangular prism | 12 nm/105 kDa | 2′-O-Methyl-RNA (2OMe) | 2F structures: >24 h | ||||

| Cube | 12 nm/140 kDa | Enantiomeric l-DNA | 2OMe structures: >24 h | ||||

| Rugby-ball | 18 nm/140 kDa | l-DNA structures: >24 h | |||||

Abbreviations: fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium, Tris acetate EDTA (TAE), agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE), polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), hexaethylene glcol (HEG), single stranded DNA (ssDNA), phosphorothioate (PS), half-life (τ1/2), hours (h), internal (int).

Table 4.

Stability of DNA NS in buffers and media, buffers with nucleases, and intra/extracellular

| Environment | DNA nanostructure | Dimensions/mass | Modifications for stability | Reported stability | Reporting | Notes | Ref. (year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffers and media | |||||||

| 1× PBS | 6-HB origami | 7 nm/36 kDa | — | Tm = 51 °C in PBS | Tm (melting temperature) | No added peptide stability | 48 (2021) |

| DMEM-Mg, 37 °C | Disk origami | 60 nm dia./4.5 MDa | — | DMEM: >5 h | AGE | No serum or nucleases | 21 (2022) |

| MES buffer pH 5.5, 37 °C | MES: >5 h | ||||||

| RPMI media low Mg, 37 °C | Barrel origami (×4) | 30–90 nm dia./4 MDa | Oligolysine (K4–K20) | All but PEI stabilized | AGE, TEM | Best salt stability with K6 | 65 (2017) |

| 5 mM Tris with 1 mM EDTA, 37 °C | Block origami | 50 nm/4 MDa | PEG oligolysine | Structures in RPMI | All oligolysines stabilized all structures | ||

| 24/6-HB origami | 100–400 nm/4 MDa | Spermidine, spermine | PEI compromised structures | ||||

| Octahedron origami | 60 nm dia./4 MDa | Polyethylenimine (PEI) Oligoarginine (R6) | R6 compromised shape | ||||

| 6 M urea, 23–42 °C | Triangle origami | 120 nm/4 MDa | Strand redesign | Up to 30 min | AFM | Ligation increased Tm by 8 °C | 112 (2019) |

| Enzymatic ligation | |||||||

| Buffers with nucleases | |||||||

| 1 U DNase I | 18-HB origami | 140 nm/4 MDa | Origami:<1 h in DNase I | AGE, TEM | Origami stable in all but DNase I and T7 exo | 80 (2011) | |

| 10 U endonucl. (T7, MseI) | 24-HB origami | 100 nm/4 MDa–70 nm/4 MDa | Partial degradation in 1 h by T7 exo | Origami ⪢ plasmid | |||

| 10 U exonucl. (T7, E. coli, lambda) | 32-HB origami | 5309 bp/3.3 MDa | Plasmid: <5 min in DNase I | ||||

| All in NE buffer 4, 37 °C | pET24b ds plasmid | ||||||

| 1 U μL−1 DNase I, 37 °C | Wide barrel origami | 90 nm dia./4 MDa | PEG oligolysine (K10P) | Native: τ1/2 < 1 min | AGE, TEM | K10P: ~400-fold improved | 81 (2020) |

| Barrel origami | 60 nm dia./4 MDa | Crosslinked K10P (×K10P) | With K10P: τ1/2 ~16 min With ×K10P: τ1/2 ~66 h | ×K10P: ~105-fold improved Over native structures | |||

| 0.2 U DNase I, 37 °C | Tetrahedron (Tet.) | 7 nm/82 kDa | Enzymatic ligation | Tet. <10 min, DS ~3 min | AGE | Tet. >3× more stable than DS | 78 (2009) |

| Linear dsDNA (DS) | 63 bp/41 kDa | ||||||

| RPMI with varying DNase I, 37 °C | Barrel origami | 60 nm dia./4 MDa | Oligolysine (K4–K20) | DNase for degradation in 1 h: 0.5 U mL−1 native, >500 U mL−1 K10: P5k | AGE, TEM | Best nuclease stability with K10:P5k | 65 (2017) |

| PEG oligolysine (K10:P1k–10k) | |||||||

| Intra/extracellular | |||||||

| Cell cytosol (COS-1, fibroblasts, astrocytes, A549, and HeLa cells) | Tetrahedron (Tet.) | 7 nm/82 kDa | — | Tet. >1 h in all cell types | Three-dye FRET | Tetrahedron ⪢ crosshair | 86 (2022) |

| 4-Arm crosshair (4ac) | 23 nm/104 kDa | 4ac <15 min in HeLa cells | |||||

| Cell lysate at 4 °C, 25 °C | Rectangle origami | 90 × 60 nm/4 MDa | — | All structures stable >12 h | AGE, TEM, AFM | No degradation observed. | 113 (2011) |

| Triangle origami | 120 nm/4 MDa | ||||||

| Block origami | 30 nm/4 MDa | ||||||

| 70% human serum, 37 °C | Nanotweezer (Ntw) | 10 nm/53 kDa | — | Ntw: >24 h in serum/blood | AGE, FRET | DS more stable than Ntw | 62 (2015) |

| 97.5% whole human blood, 37 °C | dsDNA probe (DS) | 22 bp/17 kDa | DS: >24 h in serum/blood | ||||

| ssDNA | 32 nt/10 kDa | ssDNA: <2 h in serum/blood | |||||

| Flowing whole blood | Tetrahedron (Tet.) | 7 nm/82 kDa | — | Tet. >1 h in all cell types | Three-dye FRET | Tetrahedron ⪢ crosshair | 9 (2018) |

| 4-Arm crosshair (4ac) | 23 nm/104 kDa | 4ac >15 min in HeLa cells | |||||

In vitro studies have played a particularly outsized role in deciphering the relationship between DNA NS design and resilience in physiological environments, owing to the fine-grained control of environmental conditions that cannot be achieved in vivo, as well as compatibility with large, multiplexed assays that can probe many design criteria and conditions simultaneously. Studies of the resilience of DNA NS against nucleases have shown that stability varies widely depending on the physical properties of the NS, as highlighted in several recent reviews,32,39,40,59–61 and structures with greater topological complexity, helical density, and crossover density have been shown to possess greater resistance to degradation by nucleases.62–64 Unfortunately, DNA NS with these characteristics tend to possess reduced thermal stability and require higher divalent cation concentrations to remain stable in solution. This is particularly notable in closely packed structures with high charge densities and to a lesser extent in structures with high crossover densities, often achieved with crossovers at nonideal positions and/or by shortening the length of complementary domains in the structure.63,64 Despite the potential drawbacks, these modifications can improve the stability of native DNA NS in the presence of nucleases by an order of magnitude or more and are thus useful tools in the design of nuclease-resistant nanostructures.

Beyond the use of native DNA NS, many strategies to modify and/or protect DNA NS in biological environments have been successfully demonstrated, such as polymer coatings adhered to structures electrostatically or chemically,41,65–67 staple strand ligation and cross-linking (Fig. 2) with chemical,68,69 enzymatic,69 and photoactivated strategies,70 incorporation of nucleic acids with nuclease-resistant backbones such as enantiomeric l-DNA,71 phosphorothioate DNA,72 peptide nucleic acids (PNA),77 and various modified RNAs,73,74 as well as protection with hard coatings such as silica.75,76 Such modifications can potentially extend the lifetimes of DNA NS in biological environments beyond that achievable with native structures, often without compromising and sometimes improving thermal and low-salt stability. A recent review article by Chandrasekaran highlights several approaches to creating nuclease resistance DNA NS.40 Fig. 2 is an example of small DNA NS that possess better serum stability when the strands are covalently linked within them versus when they are not.69 From the various reports in the literature gathered here, some general trends for structures in similar environments can be identified. The lifetime of single-stranded and duplexed DNA prior to assembly into DNA NS is typically on the order of an hour or less in serum/media and 10 min or less in buffer with nucleases.52,67,78 The lifetimes of native DNA NS are improved to several hours or longer in serum/media,5,69,79 though native structures are often fully degraded within an hour in buffer with nucleases.78,80,81 Modified DNA NS tend to have lifetimes in serum/media on the order of days and several hours in buffer with nucleases,65,69,71 though some oligolysine-based coatings have been shown to extend lifetimes to days even in exposure to high nuclease concentrations.81

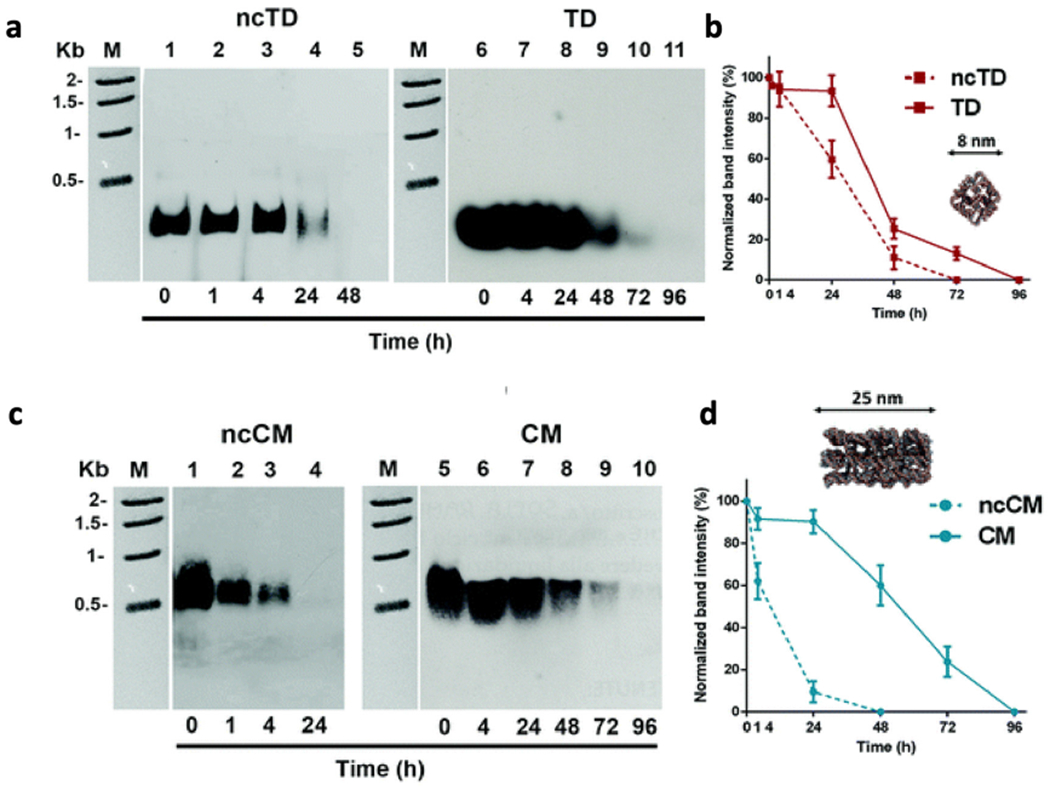

Fig. 2.

Stability of selected DNA NS in FBS containing serum without and with non-covalent (nc) linkage. The NS studied, namely, (a and b) tetrahedral (TD) and (c and d) chainmail (CM), were covalently interlocked via alkyne–azide linkage between ends of adjacent DNA molecules. Stability was studied in the presence of 10% FBS serum and measured via agarose gel electrophoresis with the results of the corresponding densitometric analysis shown in the accompanying plots. Reproduced from ref. 69 with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry. Copyright 2019.

It remains a challenge to identify more than basic trends from the consolidated studies of DNA NS stability due to a general lack of standardization and best practices between studies. Studies often vary in several ways between nanostructure design, buffer conditions, nuclease activity, types of nucleases, methods of characterizing structural integrity, and reported measures of stability.1,32,40,82 This makes it extremely hard to correlate results amongst these studies. Additionally, it is not yet common practice to calibrate the enzymatic activity of nucleases in sera and buffers, which can vary with aging and handling, prior to their use,32,61,79 thus it is possible for studies to report different values for stability of the same DNA NS under identical conditions. Until some form of standards are adopted, we must rely on the consistency within individual studies to elucidate the preliminary rules dictating DNA NS stability in biological environments.

Conclusions and future outlook

From reviewing the consolidated summary of DNA NS uptake behavior (Table 1), it can be surmised that the overall size of the NS tested thus far ranges from a few nm (with 7 nm tetrahedron being the dominant test-bed) to 100 nm per side, which translates to an approximate range of 30 kilodaltons (kDa) up to 4 megadaltons (MDa) in terms of globular mass. The arbitrarily different DNA NS that have been administered in uptake related studies, however, do not bear a direct correlation to NS mass, making it challenging to compare their performance in a systematic manner. This review also does not focus on the intracellular mechanisms of DNA NS endocytosis since a definitive consensus or enough data is still being sought by the field. A similar issue emerges for the stability studies highlighted in Tables 3 and 4, and if these issues persist, every DNA NS employed for therapeutic applications will require a case-by-case stability evaluation. It would be extremely beneficial if the field could collaborate and actively formulate a protocol for standardized quality control expected from each study that will be undertaken in the future.83 Such assay cascades have been put into place for other nanomaterials being developed for potential clinical use.84

The progress in recent decades on biomedically applied DNA NS is exemplative of a promising role of the field in targeted and combinatorial therapeutic interventions. Future directions that the field has already seen some movement towards are in vaccine development through strategic antigen display or through delivery of antigenic cargo to immune cells. Combinatorial therapies, wherein adjuvants such as CpG, nanoparticles, and intercalating drugs are simultaneously delivered via a targeted DNA NS, are also of high interest. Lastly, delivery of functional nucleic acids through DNA NS such as silencing RNA (siRNA), or even epitope-expressing genes, warrant further investigation.

Towards achieving a status that currently favors lipid and viral-based nanoparticles as delivery systems, a few concerted efforts are needed and already underway. Consolidation into a repository of DNA NS that have been designed and engineered by the rapidly growing expert community will help repurpose successful NS in application-specific translational studies, much like the tetrahedron (originally designed by Goodman et al.37), has become prototypical in fundamental studies. Nanobase.org by Poppleton et al. is one such endeavor that is creating a database of DNA and RNA NS.85 From such collaborations, one can anticipate certain DNA NS to emerge (or evolve) as superior cell- and intervention-specific (immune-stimulation versus nucleic acid delivery versus pharmacochemical delivery) options, but will more importantly be informed with recommendations on dosage, targeting moieties, and site-directed modifications by relevant studies in the literature.

The need of the hour is more cell-directed studies elucidating the programmable release and stability of DNA NS inside the cell. Fig. 3 shows results from a recent report where dyelabeled DNA structures were directly microinjected into the cytosol of a variety of different primary and transformed cells and the stability of the structures evaluated by tracking the resulting FRET over time.86 This format was exploited to bypass the complications of endocytic uptake so that the only variable became that of cytosolic stability. This study confirmed that the high-torsion DNA tetrahedron is more stable in the cellular cytosol than linear structures. Perhaps it is worth exploring the feasibility of adopting techniques of cytosolic delivery through endocytosis that have shown promise for other non-nucleic acid nanoparticles. Like DNA NS, calcium phosphate nanoparticles (CPN) aim to be carriers that introduce medication into the cell in a noninvasive manner.87,88 Both nanoparticle types are taken into the cell via endocytosis and face stability issues as they are transported into the lysosome.87,88 Some stability issues can be alleviated if the CPNs can undergo endosomal escape into the cytoplasm.87–90 Research using CPNs has shown successful endosomal escape of the nanoparticle via destabilization,87,88 thus we can attempt to integrate destabilizing methods, like cationic polymers88,89 and pH sensitive polymers87,89 in DNA NS administration to investigate if the same effect is observed. Furthermore, expanding cytosolic studies to other DNA NS types as well as integration of stabilizing techniques are needed.86

Fig. 3.

A study on the cytosolic stability of small DNA nanoparticles. Schematic with scale shown of the (a) nanocrosshair and (b) tetrahedron structures whose stability was observed directly in the cytosol of live cells. The location of dye labels and FRET pathway on each structure are also shown. COS-1 cells microinjected with the nanocrosshair (c) and (d) tetrahedron shown at t = 0 min and t = 60 min. After 60 min the FRET changed based on the change in stability of the DNA structure can be seen. (e) Plot of the change in acceptor dye to donor dye fluorescence ratio over time in the nanocrosshair versus tetrahedron DNA structure. (f) Plot of the change in acceptor dye to donor dye fluorescence ratio over time for microinjected samples of the nanocrosshair supplemented with the indicated concentrations of aurintricarboxylic acid nuclease inhibitor providing evidence that degradation resulted from nuclease activity. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from ref. 86 Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

Feasibility of DNA NS based therapies at a scale where patient impact is significant are required as well. For example, to what extent are DNA NS based anti-cancer interventions advantageous from an economic standpoint is being evaluated.91 It is also notable that the dosage of DNA NS tested in Tables 1 and 2 are in the nM scale, urging careful evaluation of scalable synthesis needed for translating DNA NS based therapies into in vivo studies, let alone clinical use. Formulations testing oral or topical administration of DNA-based treatments are slowly emerging as well.92,93 Additionally aerosolization, lyophilized storage,94 scalable production,95 and long term stability96,97 of DNA NS have seen preliminary success in some cases but are topics in which ongoing research is actively engaged. In order to realize the widespread applicability of these fascinating materials within a medical context, everything comes back full circle to understanding their fundamental structural integrity and functional properties intracellularly and this still remains the first challenge.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the US Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), the Office of Naval Research, and the NRL’s Nanoscience Institute for programmatic funding. D. M. was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under award number R00EB030013-03. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Mathur D and Medintz IL, Adv. Healthcare Mater, 2019, 8, e1801546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang S, Ge Z, Mou S, Yan H and Fan C, Chem, 2021, 7, 1156–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okholm AH and Kjems J, Expert Opin. Drug Delivery, 2017, 14, 137–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller A and Linko V, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2020, 59, 15818–15833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Udomprasert A, Wootthichairangsan C, Duangrat R, Chaithongyot S, Zhang Y, Nixon R, Liu W, Wang R, Ponglikitmongkol M and Kangsamaksin T, ACS Appl. Bio Mater, 2022, 5, 2262–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang Q, Song C, Nangreave J, Liu X, Lin L, Qiu D, Wang ZG, Zou G, Liang X, Yan H and Ding B, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 13396–13403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palazzolo S, Hadla M, Russo Spena C, Caligiuri I, Rotondo R, Adeel M, Kumar V, Corona G, Canzonieri V, Toffoli G and Rizzolio F, Cancers, 2019, 11, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng Y, Liu J, Yang S, Liu W, Xu L and Wang R, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2018, 6, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Jiang Q, Liu S, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Song C, Wang J, Zou Y, Anderson GJ, Han JY, Chang Y, Liu Y, Zhang C, Chen L, Zhou G, Nie G, Yan H, Ding B and Zhao Y, Nat. Biotechnol, 2018, 36, 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao S, Tian R, Wu J, Liu S, Wang Y, Wen M, Shang Y, Liu Q, Li Y, Guo Y, Wang Z, Wang T, Zhao Y, Zhao H, Cao H, Su Y, Sun J, Jiang Q and Ding B, Nat. Commun, 2021, 12, 358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rangnekar A, Zhang AM, Li SS, Bompiani KM, Hansen MN, Gothelf KV, Sullenger BA and LaBean TH, Nanomedicine, 2012, 8, 673–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao S, Duan F, Liu S, Wu T, Shang Y, Tian R, Liu J, Wang ZG, Jiang Q and Ding B, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2019, 11, 11112–11118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellmeier J, Platzer R, Eklund AS, Schlichthaerle T, Karner A, Motsch V, Schneider MC, Kurz E, Bamieh V, Brameshuber M, Preiner J, Jungmann R, Stockinger H, Schutz GJ, Huppa JB and Sevcsik E, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2021, 118, e2016857118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellmeier J, Platzer R, Muhlgrabner V, Schneider MC, Kurz E, Schutz GJ, Huppa JB and Sevcsik E, ACS Nano, 2021, 15, 15057–15068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong R, Aksel T, Chan W, Germain RN, Vale RD and Douglas SM, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2021, 118, e2109057118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang T, Alvelid J, Spratt J, Ambrosetti E, Testa I and Teixeira AI, ACS Nano, 2021, 15, 3441–3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai Y, Islam MS, Adamiak M, Shiu SC, Tanner JA and Heddle JG, Genes, 2018, 9, 571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Zhu J, Jia W, Xiong H, Qiu W, Xu R and Lin Y, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2022, 14, 44228–44238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan S, Liu S, Sun M, Zhang J, Wei X, Song T, Li Y, Liu X, Chen H, Yang CJ and Song Y, ACS Nano, 2022, 16, 15310–15317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veneziano R, Moyer TJ, Stone MB, Wamhoff EC, Read BJ, Mukherjee S, Shepherd TR, Das J, Schief WR, Irvine DJ and Bathe M, Nat. Nanotechnol, 2020, 15, 716–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comberlato A, Koga MM, Nussing S, Parish IA and Bastings MMC, Nano Lett, 2022, 22, 2506–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seitz I, Ijas H, Linko V and Kostiainen MA, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2022, 14, 38515–38524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas SM, Bachelet I and Church GM, Science, 2012, 335, 831–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelen W, Sigl C, Kadletz K, Willner EM and Dietz H, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2021, 143, 21630–21636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitikultham P, Wang Z, Wang Y, Shang Y, Jiang Q and Ding B, ChemMedChem, 2022, 17, e202100635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bujold KE, Hsu JCC and Sleiman HF, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 14030–14038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang D, Sun Y, Li J, Li Q, Lv M, Zhu B, Tian T, Cheng D, Xia J, Zhang L, Wang L, Huang Q, Shi J and Fan C, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2016, 8, 4378–4384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas CR, Halley PD, Chowdury AA, Harrington BK, Beaver L, Lapalombella R, Johnson AJ, Hertlein EK, Phelps MA, Byrd JC and Castro CE, Small, 2022, 18, e2108063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin-Shiao E, Pfeifer WG, Shy BR, Saffari Doost M, Chen E, Vykunta VS, Hamilton JR, Stahl EC, Lopez DM, Sandoval Espinoza CR, Deyanov AE, Lew RJ, Poirer MG, Marson A, Castro CE and Doudna JA, Nucleic Acids Res, 2022, 50, 1256–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang D, Ge Z, Im HJ, England CG, Ni D, Hou J, Zhang L, Kutyreff CJ, Yan Y, Liu Y, Cho SY, Engle JW, Shi J, Huang P, Fan C, Yan H and Cai W, Nat. Biomed. Eng, 2018, 2, 865–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee H, Lytton-Jean AK, Chen Y, Love KT, Park AI, Karagiannis ED, Sehgal A, Querbes W, Zurenko CS, Jayaraman M, Peng CG, Charisse K, Borodovsky A, Manoharan M, Donahoe JS, Truelove J, Nahrendorf M, Langer R and Anderson DG, Nat. Nanotechnol, 2012, 7, 389–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green CM, Mathur D and Medintz IL, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2020, 8, 6170–6178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang P, Rahman MA, Zhao Z, Weiss K, Zhang C, Chen Z, Hurwitz SJ, Chen ZG, Shin DM and Ke Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 2478–2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vindigni G, Raniolo S, Ottaviani A, Falconi M, Franch O, Knudsen BR, Desideri A and Biocca S, ACS Nano, 2016, 10, 5971–5979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang L, Li J, Li Q, Huang Q, Shi J, Yan H and Fan C, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2014, 53, 7745–7750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rothemund PW, Nature, 2006, 440, 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodman RP, Berry RM and Turberfield AJ, Chem. Commun, 2004, 12, 1372–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ke Y, Ong LL, Shih WM and Yin P, Science, 2012, 338, 1177–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manuguri S, Nguyen MK, Loo J, Natarajan AK and Kuzyk A, Bioconjugate Chem, 2023, 34, 6–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chandrasekaran AR, Nat. Rev. Chem, 2021, 5, 225–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmadi Y, De Llano E and Barisic I, Nanoscale, 2018, 10, 7494–7504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park S and Hamad-Schifferli K, ACS Nano, 2010, 4, 2555–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chopra A, Krishnan S and Simmel FC, Nano Lett, 2016, 16, 6683–6690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mikkila J, Eskelinen AP, Niemela EH, Linko V, Frilander MJ, Torma P and Kostiainen MA, Nano Lett, 2014, 14, 2196–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kansara K, Kumar A and Bhatia D, Appl. Nanomed, 2022, 22, 337. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rahman MA, Wang P, Zhao Z, Wang D, Nannapaneni S, Zhang C, Chen Z, Griffith CC, Hurwitz SJ, Chen ZG, Ke Y and Shin DM, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2020, 59, 12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rahman MA, Wang P, Zhao Z, Wang D, Nannapaneni S, Zhang C, Chen Z, Griffith CC, Hurwitz SJ, Chen ZG, Ke Y and Shin DM, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2017, 56, 16023–16027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smolkova B, MacCulloch T, Rockwood TF, Liu M, Henry SJW, Frtus A, Uzhytchak M, Lunova M, Hof M, Jurkiewicz P, Dejneka A, Stephanopoulos N and Lunov O, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2021, 13, 46375–46390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walsh AS, Yin H, Erben CM, Wood MJ and Turberfield AJ, ACS Nano, 2011, 5, 5427–5432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kern N, Dong R, Douglas SM, Vale RD and Morrissey MA, eLife, 2021, 10, 68311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prakash V, Tsekouras K, Venkatachalapathy M, Heinicke L, Presse S, Walter NG and Krishnan Y, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2019, 58, 3073–3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lacroix A, Vengut-Climent E, de Rochambeau D and Sleiman HF, ACS Cent. Sci, 2019, 5, 882–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X, Xu Y, Yu T, Clifford C, Liu Y, Yan H and Chang Y, Nano Lett, 2012, 12, 4254–4259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding H, Li J, Chen N, Hu X, Yang X, Guo L, Li Q, Zuo X, Wang L, Ma Y and Fan C, ACS Cent. Sci, 2018, 4, 1344–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng X, Fang S, Ji B, Li M, Song J, Qiu L and Tan W, Nano Lett, 2021, 21, 6946–6951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rajwar A, Shetty SR, Vaswani P, Morya V, Barai A, Sen S, Sonawane M and Bhatia D, ACS Nano, 2022, 16, 10496–10508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sigl C, Willner EM, Engelen W, Kretzmann JA, Sachenbacher K, Liedl A, Kolbe F, Wilsch F, Aghvami SA, Protzer U, Hagan MF, Fraden S and Dietz H, Nat. Mater, 2021, 20, 1281–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ren S, Fraser K, Kuo L, Chauhan N, Adrian AT, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ, Kwon PS and Wang X, Nat. Protoc, 2022, 17, 282–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stephanopoulos N, ChemBioChem, 2019, 20, 2191–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lacroix A and Sleiman HF, ACS Nano, 2021, 15, 3631–3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bila H, Kurisinkal EE and Bastings MMC, Biomater. Sci, 2019, 7, 532–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goltry S, Hallstrom N, Clark T, Kuang W, Lee J, Jorcyk C, Knowlton WB, Yurke B, Hughes WL and Graugnard E, Nanoscale, 2015, 7, 10382–10390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chandrasekaran AR, Vilcapoma J, Dey P, Wong-Deyrup SW, Dey BK and Halvorsen K, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2020, 142, 6814–6821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xin Y, Piskunen P, Suma A, Li C, Ijas H, Ojasalo S, Seitz I, Kostiainen MA, Grundmeier G, Linko V and Keller A, Small, 2022, 18, e2107393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ponnuswamy N, Bastings MMC, Nathwani B, Ryu JH, Chou LYT, Vinther M, Li WA, Anastassacos FM, Mooney DJ and Shih WM, Nat. Commun, 2017, 8, 15654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agarwal NP, Matthies M, Gur FN, Osada K and Schmidt TL, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2017, 56, 5460–5464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Conway JW, McLaughlin CK, Castor KJ and Sleiman H, Chem. Commun, 2013, 49, 1172–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cassinelli V, Oberleitner B, Sobotta J, Nickels P, Grossi G, Kempter S, Frischmuth T, Liedl T and Manetto A, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 7795–7798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raniolo S, Croce S, Thomsen RP, Okholm AH, Unida V, Iacovelli F, Manetto A, Kjems J, Desideri A and Biocca S, Nanoscale, 2019, 11, 10808–10818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gerling T, Kube M, Kick B and Dietz H, Sci. Adv, 2018, 4, eaau1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim KR, Kang SJ, Lee AY, Hwang D, Park M, Park H, Kim S, Hur K, Chung HS, Mao C and Ahn DR, Biomaterials, 2019, 195, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schuller VJ, Heidegger S, Sandholzer N, Nickels PC, Suhartha NA, Endres S, Bourquin C and Liedl T, ACS Nano, 2011, 5, 9696–9702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin C, Ke Y, Li Z, Wang JH, Liu Y and Yan H, Nano Lett, 2009, 9, 433–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim KR, Kim HY, Lee YD, Ha JS, Kang JH, Jeong H, Bang D, Ko YT, Kim S, Lee H and Ahn DR, J. Controlled Release, 2016, 243, 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nguyen L, Doblinger M, Liedl T and Heuer-Jungemann A, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2019, 58, 912–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nguyen M-K, Nguyen VH, Natarajan AK, Huang Y, Ryssy J, Shen B and Kuzyk A, Chem. Mater, 2020, 32, 6657–6665. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fairweather S, Rogers M, Stoulig P, O’Murphy F, Bose E, Tumusiime S, Desany A, Troisi M, Alvarado A, Wade E, Cruz K, Wlodychak K and Bell AJ Jr., Biophys. Chem, 2022, 289, 106863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Keum JW and Bermudez H, Chem. Commun, 2009, 45, 7036–7038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hahn J, Wickham SF, Shih WM and Perrault SD, ACS Nano, 2014, 8, 8765–8775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Castro CE, Kilchherr F, Kim DN, Shiao EL, Wauer T, Wortmann P, Bathe M and Dietz H, Nat. Methods, 2011, 8, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anastassacos FM, Zhao Z, Zeng Y and Shih WM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2020, 142, 3311–3315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Afonin KA, Dobrovolskaia MA, Church G and Bathe M, ACS Nano, 2020, 14, 9221–9227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rennick JJ, Johnston APR and Parton RG, Nat. Nanotechnol, 2021, 16, 266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.NCI, Assay Cascade Characterization Program, https://www.cancer.gov/nano/research/ncl/assay-cascade, (accessed September 2, 2022).

- 85.Poppleton E, Mallya A, Dey S, Joseph J and Sulc P, Nucleic Acids Res, 2022, 50, D246–D252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mathur D, Rogers KE, Diaz SA, Muroski ME, Klein WP, Nag OK, Lee K, Field LD, Delehanty JB and Medintz IL, Nano Lett, 2022, 22, 5037–5045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maitra A, Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn, 2005, 5, 893–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pittella F, Zhang M, Lee Y, Kim HJ, Tockary T, Osada K, Ishii T, Miyata K, Nishiyama N and Kataoka K, Biomaterials, 2011, 32, 3106–3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martens TF, Remaut K, Demeester J, De Smedt SC and Braeckmans K, Nano Today, 2014, 9, 344–364. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ma D, Nanoscale, 2014, 6, 6415–6425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Coleridge EL and Dunn KE, Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express, 2020, 6, 065030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang G, Lee HE, Shin SW, Um SH, Lee JD, Kim K-B, Kang HC, Cho Y-Y, Lee HS and Lee JY, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2018, 28, 1801918. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Baig M, Khan S, Naeem MA, Khan GJ and Ansari MT, Biomed. Pharmacother, 2018, 97, 1250–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhu B, Zhao Y, Dai J, Wang J, Xing S, Guo L, Chen N, Qu X, Li L, Shen J, Shi J, Li J and Wang L, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2017, 9, 18434–18439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Praetorius F, Kick B, Behler KL, Honemann MN, Weuster-Botz D and Dietz H, Nature, 2017, 552, 84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xin Y, Kielar C, Zhu S, Sikeler C, Xu X, Moser C, Grundmeier G, Liedl T, Heuer-Jungemann A, Smith DM and Keller A, Small, 2020, 16, e1905959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kielar C, Xin Y, Xu X, Zhu S, Gorin N, Grundmeier G, Moser C, Smith DM and Keller A, Molecules, 2019, 24, 2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu S, Jiang Q, Zhao X, Zhao R, Wang Y, Wang Y, Liu J, Shang Y, Zhao S, Wu T, Zhang Y, Nie G and Ding B, Nat. Mater, 2021, 20, 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li J, Pei H, Zhu B, Liang L, Wei M, He Y, Chen N, Li D, Huang Q and Fan C, ACS Nano, 2011, 5, 8783–8789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kocabey S, Meinl H, MacPherson IS, Cassinelli V, Manetto A, Rothenfusser S, Liedl T and Lichtenegger FS, Nanomaterials, 2014, 5, 47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bujold KE, Fakhoury J, Edwardson TGW, Carneiro KMM, Briard JN, Godin AG, Amrein L, Hamblin GD, Panasci LC, Wiseman PW and Sleiman HF, Chem. Sci, 2014, 5, 2449–2455. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim KR, Kim J, Back JH, Lee JE and Ahn DR, ACS Nano, 2022, 16, 7331–7343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhao YX, Shaw A, Zeng X, Benson E, Nystrom AM and Hogberg B, ACS Nano, 2012, 6, 8684–8691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xia Z, Wang P, Liu X, Liu T, Yan Y, Yan J, Zhong J, Sun G and He D, Biochemistry, 2016, 55, 1326–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jiang Y, Zhou H, Zhao W and Zhang S, Anal. Chem, 2022, 94, 6771–6780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bastings MMC, Anastassacos FM, Ponnuswamy N, Leifer FG, Cuneo G, Lin C, Ingber DE, Ryu JH and Shih WM, Nano Lett, 2018, 18, 3557–3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu CX, Wang B, Zhu WP, Xu YF, Yang YY and Qian XH, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed, 2022, 61, e202205509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bhatia D, Surana S, Chakraborty S, Koushika SP and Krishnan Y, Nat. Commun, 2011, 2, 339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fu M, Dai L, Jiang Q, Tang Y, Zhang X, Ding B and Li J, Chem. Commun, 2016, 52, 9240–9242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kim KR, Lee YD, Lee T, Kim BS, Kim S and Ahn DR, Biomaterials, 2013, 34, 5226–5235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fakhoury JJ, McLaughlin CK, Edwardson TW, Conway JW and Sleiman HF, Biomacromolecules, 2014, 15, 276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ramakrishnan S, Scharfen L, Hunold K, Fricke S, Grundmeier G, Schlierf M, Keller A and Krainer G, Nanoscale, 2019, 11, 16270–16276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mei Q, Wei X, Su F, Liu Y, Youngbull C, Johnson R, Lindsay S, Yan H and Meldrum D, Nano Lett, 2011, 11, 1477–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]