Abstract

Herein, we describe efficient nanogold-catalyzed cycloisomerization reactions of alkynoic acids and allenynamides to enol lactones and dihydropyrroles, respectively (the latter via an Alder-ene reaction). The gold nanoparticles were immobilized on thiol-functionalized microcrystalline cellulose and characterized by electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) and by XPS. The thiol-stabilized gold nanoparticles (Au0) were obtained in the size range 1.5–6 nm at the cellulose surface. The robust and sustainable cellulose-supported gold nanocatalyst can be recycled for multiple cycles without losing activity.

Keywords: cellulose-supported nanogold catalysis, C−C bond formation, heterogeneous catalysis, cycloisomerization, heterocycles, Alder-ene reaction

The development of robust and selective heterogeneous catalytic processes is fundamental for the future of our planet since the possibility of recycling the catalysts after the reaction completion opens up the possibility for highly sustainable processes avoiding the presence of metal pollutant in the reaction wastes.1 Common support materials for metal catalysts are carbon, alumina, and silica as well as polymeric materials.2 Natural polymers have received great attention from the scientific community due to their abundance, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and nontoxicity.3 Cellulose is the most abundant macromolecule in the world. The use of polysaccharides as heterogeneous supports for metal catalysts offers many advantages, compared to other heterogeneous supports, such as increased absorption capacity and the presence of many hydroxyl groups that offers the possibility to anchor various functional groups.4

Lactones of enols are structural motifs of many drugs and natural products exhibiting high biological activity.5 They are also useful building blocks and versatile intermediates in the synthesis of complex molecules.6 Catalytic intramolecular cycloisomerization of alkynoic acids provides an easy atom-economical way for the synthesis of functionalized enol lactones. Different transition-metal complexes (Pd,7 Au,8 Ag,9 Pt10) have been shown to be able to catalyze the intramolecular cyclization reaction with high degrees of regio- and chemoselectivity.

Alder-ene reactions are powerful for the synthesis of functionalized heterocycles, such as pyrroles. Various homogeneous catalytic approaches have been reported. Thus, Pt,11 Au,12 and Ag13 were used to promote the cyclization of 1,6-allenynes for stereoselective synthesis of trienes. Bäckvall and co-workers reported numerous studies on the alkyne-assisted palladium-catalyzed oxidative carbocyclization of allenynes, where the nucleophilic attack on palladium by the allene and the subsequent alkyne insertion led to the construction of a variety of 5-membered-ring compounds.14 Recently, our groups tried to expand the synthetic protocol of allenyne carbocyclization to first-row transition-metal catalysts. In this context, we reported a novel cellulose-supported heterogeneous nanocopper-catalyzed carbocyclization of allenynamides to pyrroles proceeding via an Alder-ene pathway.15a

Gold catalysts have shown a great capability to activate π carbon–carbon bonds, especially related to alkynes and allenes, toward the addition of nucleophiles.16 Gold nanoparticles, due their heat and air stability, have attracted the interest of many researchers from different scientific fields.17−19 One of the pioneering studies on the synthesis of gold nanoparticles was done by Turkevich et al. in 1951, in which HAuCl4 was reduced by citrate.18a In 1994, Brust and Schiffrin reported a fundamental protocol in two steps for the synthesis of thiol-stabilized gold nanoparticles. First, a solution of HAuCl4 was mixed with thiol ligands, leading to the reduction of the AuIII salt to AuI thiolates. Next, the AuI thiolates were further reduced by NaBH4 to generate gold nanoparticles.18b In 2015, Bäckvall and co-workers reported a novel electrochemical method for the preparation of gold nanoparticles supported on thiol-functionalized MCF.19 The AuIII species were first reduced by a surface-confined redox reaction with the thiol ligands to form MCF-supported AuI thiolates. The MCF-SH-AuI intermediate was isolated and further reduced with NaBH4 to give MCF-supported gold nanoparticles.19 It was demonstrated that the nanoparticle size is directly related to the catalytic activity.

The immobilization of nanoparticles, on heterogeneous solid supports, offers an easy way to avoid the agglomeration during the reaction process stabilizing the catalytic activity.20 Various solid materials such as cellulose,21 carbon nanotubes,22 zeolites,23 mesocellular foam,14e,19 and metal oxides24 have been studied as heterogeneous supports for gold nanoparticles. In our groups, we have worked extensively on the preparation of novel heterogeneous catalyst systems for stereoselective synthesis14e,25 and on the construction of functional cellulose-based materials.14f,15a,15f,15h,15i Based on our previous work, we decided to investigate cellulose–gold heterogeneous catalysts for application in selective organic synthesis. Herein, we report on a cellulose-supported gold nanocatalyst for promoting cycloisomerization of alkynoic acids and allenynamides to enol lactones and dihydropyrroles, respectively, in high yields. The sustainable catalyst was recyclable and was used for 9 cycles without losing efficiency or selectivity. A remarkable observation is that the Au(0) nanoparticles on cellulose catalyze reactions that usually require Au(I) as a catalyst.

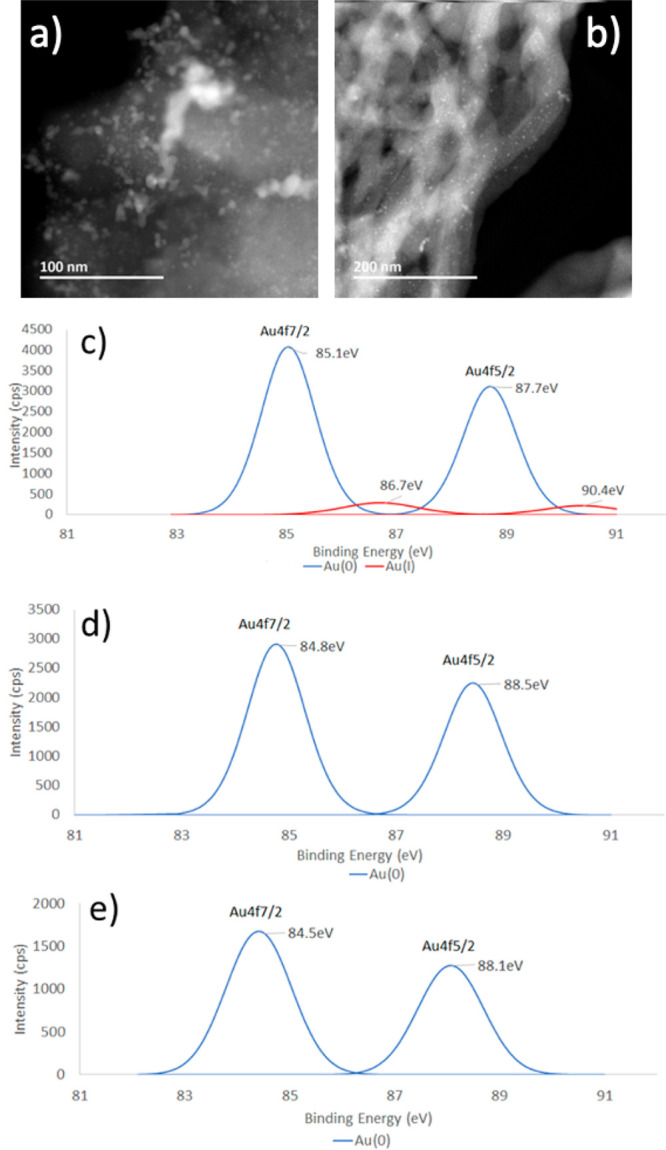

We began our study by fabricating cellulose-supported catalysts. Thus, the gold nanoparticles were immobilized on microcrystalline cellulose (MCC)26 functionalized with mercaptopropyl (McP) silane or aminopropyl (AmP) silane groups. A schematic overview of the synthesis of the MCC-Au0 catalysts is provided in Scheme 1. First MCC-McP and MCC-AmP were prepared by organocatalytic silylation catalyzed by tartaric acid.15f,15g Next, the functionalized MCC was dispersed in an aqueous solution where HAuCl4 had been previously added to furnish the MCC-Au precatalysts, respectively. In the case of mixing the thiol-functionalized cellulose (MCC-McP) with HAuCl4 (0.1 M HCl), in situ reduction of the Au by sulfur occurred, and MCC-McP-Au0/AuI was formed with Au(0) being the dominant oxidation state as shown by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Figure 1c.) At the same time, the thiol groups at the MCC-McP surface were oxidized to SVI (−SO2–, −SO3H) as determined by XPS (see the Supporting Information). In this context, oxidation of thiol groups linked to gold nanoparticles to sulfones can significantly improve their catalytic activity for enyne cyclizations.12c Subsequent reduction of the MCC-Au precatalysts with NaBH4 gave access to the Au nanoparticle catalyst MCC-McP-Au0 (Figure 1d). The NaBH4 reduction of the MCC-AmP-Au precatalyst gave the corresponding MCC-AmP-Au0. The Au0 nanoparticles were characterized by scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), and the high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) STEM images showed well-dispersed nanoparticles supported on MCC with a size range distribution of 1.5–6 nm (Figure 1a,b and Figure S1). The loadings of Au on MCC-McP-Au0 and on MCC-AmP-Au0 were 4.5% (w/w) and 16.3% (w/w), respectively, as determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES).

Scheme 1. General Procedure for the Synthesis of MCC-Supported Gold Nanoparticle Catalysts.

Figure 1.

(a, b) HAADF-STEM images of well-dispersed Au nanoparticles on MCC-McP-Au0 at 100 and 200 nm scales, respectively. XPS spectra at the Au 4f (4f5/2 and 4f7/2) peaks of (c) MCC-McP-Au0/AuI, (d) MCC-McP-Au0, and (e) MCC-McP-Au0 after one reaction cycle.

With the cellulose-supported Au nanoparticle catalysts in hand, we began our investigations of catalytic intramolecular cyclization of alkynoic acids and allenenynamides. We started testing the efficiency of MCC-McP-Au0 nanocatalysts for the cycloisomerization of 4-pentynoic acid 1a.

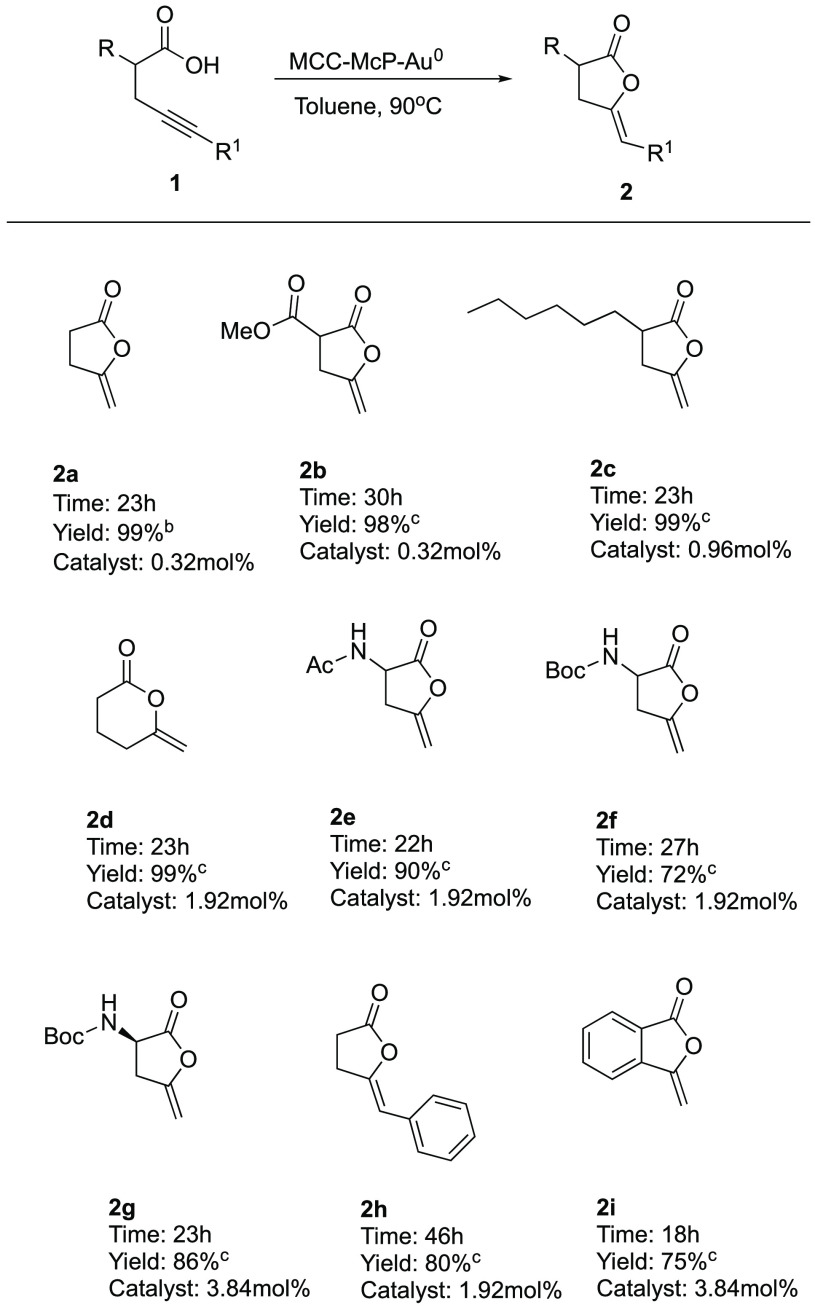

Different solvents were screened (Table 1), and running the reaction in toluene or acetonitrile at 90 °C, for 23 h, gave the corresponding product 2a in quantitative yield. We also performed a control reaction with MCC-sulfonic acid propyl silane, which had been prepared by oxidation of MCC-McP with H2O2, using the exact same reaction conditions. The sulfonic acid modified MCC was not able to catalyze the formation of 2a from 1a (entry 6). We also tried to use MCC-McP-Au0/AuI, which is predominantly Au0 (Figure 1c). Surprisingly, under the standard conditions for lactonization of 1a this catalyst gave only trace amounts of lactone 2a (entry 7). With these results in hand, we performed the reaction on a variety of substrates using MCC-McP-Au0 (Scheme 2).27 α-substituted alkynoic acids with different functional groups gave the corresponding cyclic products 2b–f in high yields. Difficult substrates such as hexynoic acid cyclized in 24 h, leading to the six-membered ring lactone 2d in 99% yield. Amino acid derivative 1g was also converted to the corresponding optically active α-amino lactone 2g without loss of enantiopurity. Substrate 1h terminally substituted with the alkyne acids gave the corresponding product 2h in 80% yield with complete Z selectivity. Substrate 1i with a rigid aromatic scaffold under these conditions cyclized in 18 h to give the corresponding benzofuran 2i in 75% yield.

Table 1. Condition Screening for the MCC-McP-Au0-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization of Alkynoic Acidsa.

| entry | solvent | temp (°C) | time (h) | conversion (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CH2Cl2 | RT | 96 | 33 |

| 2 | CH2Cl2 | 40 | 24 | 20 |

| 3 | toluene | 90 | 23 | 99 |

| 4 | dioxane | 90 | 23 | 81 |

| 5 | CH3CN | 90 | 23 | 99 |

| 6c | toluene | 90 | 23 | 0 |

| 7d | toluene | 90 | 23 | 2 |

Reaction conditions unless specified otherwise: 1a (0.4 mmol), MCC-McP-Au0 (5 mg, 0.32 mol % Au0), solvent (1 mL).

Conversion to 2a as determined by 1H NMR using 1,4-dinitrobenzene as internal standard.

Reaction performed with MCC-sulfonic acid propyl silane (MCC-Si-CH2CH2CH2SO2H).

Scheme 2. MCC-McP-Au0-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization of Different Alkynoic Acids.

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.4 mmol), MCC-McP-Au0, toluene (1 mL), 90 °C.

Determined by 1H NMR using 1,4-dinitrobenzene as internal standard.

Isolated yield after flash chromatography.

We also carried out a few selected reactions with MCC-AmP-Au0 as a catalyst (Scheme 3). As can be seen from Scheme 3, results very similar to those in Scheme 2 were obtained. Also, here substitution at the terminal position of the alkyne with an aromatic compound (p-CF3-C6H4, 1j) afforded the Z isomer 2j in 73% yield.

Scheme 3. MCC-AmP-Au0-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization of Different Alkynoic Acids.

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.4 mmol), MCC-AmP-Au0, toluene (1 mL), 90 °C.

Determined by 1H NMR using 1,4-dinitrobenzene as internal standard.

Isolated yield after flash chromatography.

Since lifetime and recycling of heterogeneous catalysts have key roles in practical applications, we evaluated the efficiency of the heterogeneous nanogold catalyst by conducting recycling experiments on the cycloisomerization of 4-pentynoic acid 1a (Table 2).28 As shown, the catalyst was recycled 9 times without any evidence of loss in activity, giving the corresponding lactone 2a in 99% NMR yield, within 23 h, for each cycle. We also performed XPS analysis of the recycled catalyst, which determined that Au(0) was the oxidation state of the gold surface of MCC-McP-Au0 (Figure 1e).

Table 2. Recycling of MCC-McP-Au0 Catalysta.

| cycle | time (h) | conversion (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23 | 99 |

| 2 | 23 | 99 |

| 3 | 23 | 99 |

| 4 | 23 | 99 |

| 5 | 23 | 99 |

| 6 | 23 | 99 |

| 7 | 23 | 99 |

| 8 | 23 | 99 |

| 9 | 23 | 99 |

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.4 mmol), MCC-McP-Au0 (20 mg, 1.28 mol %), toluene (1 mL), 90 °C.

Determined by 1H NMR using 1,4-dinitrobenzene as internal standard.

Another fundamental aspect that makes heterogeneous catalysis so attractive for industrial use and for the development of green protocols is the possibility to avoid the accumulation of toxic industrial waste containing hazardous metal complexes. Thus, to determine the presence of free homogeneous Au species in solution during the reaction, hot filtration experiments were performed on the cycloisomerization of 1a to 2a (Scheme 2). MCC-McP-Au0 was filtered off after 20% conversion, and after that no more product 2a was detected on attempted continued reaction. In a parallel control experiment, MCC-McP-Au0 was filtered off after full conversion. In both cases, inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) showed no presence of free Au species in the remaining solution (<0.5 ppm), confirming that there was no leaching of Au from MCC-McP-Au0.29

Also, in the MCC-AmP-Au0- catalyzed cycloisomerization of 1a to 2a (Scheme 3) the catalyst was filtered off after full conversion. In this case, ICP-OES analysis of the crude reaction mixture revealed a leaching of 7.5% of the total amount of Au used in this experiment. These results support the use of MCC-McP-Au0 as the preferred heterogeneous nanocatalyst for cycloisomerization transformations.

In cycloisomerization of alkynoic acids, e.g. 1 to 2, catalyzed by homogeneous gold complexes, an Au(I) complex is the catalyst and it is proposed that an Au(I)-alkyne complex is attacked by the carboxylate group to give the lactone.8c,8e Hydrolysis of the gold–carbon bond would give the product. The stereochemistry of the product when a disubstituted alkyne is used is in line with this mechanism. It is remarkable that the heterogeneous Au(0) catalyst MCC-McP-Au0, with no detectable amounts of Au(I) according to XPS, worked well as the catalyst. It is likely that a small number of Au(I) atoms are formed together with Au(0) in the Au(0) particles. The failure of MCC-McP-Au0/AuI to catalyze the lactonization of 1a to 2a (entry 7, Table 1), may be due to the lack of nanoparticle formation in the latter material. This was supported by both HAADF-STEM images and Au L-edge EDS maps of the MCC-McP-Au0/AuI (see Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). In contrast to MCC-McP-Au0, MCC-McP-Au0/AuI shows evenly distributed Au(I) complexes on the MCC support, and no distinct nanoparticles were observed.

Motivated by the high yields detailed above and excellent recyclability of the MCC-McP-Au0 catalyst (Scheme 2 and Table 2), we decided to investigate the use of this catalyst for the conversion of allenynamide 3 to dihydropyrrole 4 (Scheme 4). We recently reported that nanocopper on MCC catalyzes this reaction via an Alder-ene cyclization mechanism.15a Substrates bearing an aryl group at the R1 position of substrates 3 cyclized within 4 h and gave the corresponding aromatic allenynamides 4a,b in 93% and 87% yields, respectively. Substrates 3c,d with an aliphatic group at the R1 position react more slowly (23 h), giving the corresponding products 4c,d in 71% and 85% yields, respectively.

Scheme 4. MCC-McP-Au0-Catalyzed Carbocyclization of Allenynamides.

Reaction conditions: 3 (0.15 mmol, 1 equiv), MCC-McP-Au0 (54 mg, 9 mol %), Cs2CO3 (0.195 mmol, 1.3 equiv), toluene (1 mL), 80 °C.

In conclusion, we have reported an efficient intramolecular cyclization of alkynoic acids to enol lactones and a stereoselective Alder-ene reaction of allenynamides to dihydropyrroles catalyzed by microcrystalline-cellulose-supported Au nanoparticles. The MCC-Au0 catalyst was shown to be highly selective for both reactions, leading to the corresponding cyclic products in high yields and high degrees of selectivity. The MCC-McP-Au0 catalyst displayed excellent recyclability without any loss of activity after 9 cycles, and no Au leaching in solution was detected. It is remarkable that the Au(0) catalyst MCC-McP-Au0 with no detectable amounts of Au(I) according to XPS catalyzes reactions that usually require Au(I) as catalyst. Further studies on the mechanism of these cellulose-based nanogold-catalyzed reactions are currently underway in our laboratories.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Swedish Research Council (2018-04425 and 2019-04042), the European Union, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research (Mistra: project Mistra SafeChem, project number 2018/11) is gratefully acknowedged.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.3c02722.

Detailed experimental procedures, STEM images, XPS spectra, FT-IR spectra, compound characterization data, and NMR spectra (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Miceli M.; Frontera P.; Macario A.; Malara A. Recovery/Reuse of Heterogeneous Supported Spent. Catalysts Catalysts 2021, 11, 591. 10.3390/catal11050591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Bailie J. E.; Hutchings G. J.; O’Leary S. O.. Supported Catalysts. Eds. Buschow K. H. J.; Cahn R. W.; Flemings M. C.; Ilschner B.; Kramer E. J.; Mahajan S.; Veyssiere P.. Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology; Elsevier: 2001; pp 8986–8990. [Google Scholar]; b Török B.; Schäfer C.; Kokel A.. Heterogeneous Catalysis in Sustainable Synthesis. In Advances in Green Chemistry; Elsevier: 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeswari S.; Prasanthi T.; Sudha N.; Swain R. P.; Panda S.; Goka S. Natural polymers: a recent review. WJPPS 2017, 6, 472–494. 10.20959/wjpps20178-9762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Levy-Ontman O.; Biton B.; Shlomov S.; Wolfson A. Renewable Polysaccharides as Supports for Palladium Phosphine Catalysts. Polymers 2018, 10, 659. 10.3390/polym10060659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yu C.; Wu W.; Gao M.; Liu Y. Modified Cellulose with BINAP-Supported Rh as an Efficient Heterogeneous Catalyst for Asymmetric Hydrogenation. Catalysts 2022, 12, 83. 10.3390/catal12010083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Liu J.; Plog A.; Groszewicz P.; Zhao L.; Xu Y.; Breitzke H.; Stark A.; Hoffmann R.; Gutmann T.; Zhang K.; Buntkowsky G. Design of a Heterogeneous Catalyst Based on Cellulose Nanocrystals for Cyclopropanation: Synthesis and Solid-State NMR Characterization. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 12414–12420. 10.1002/chem.201501151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels S. B.; Katzenellenbogen J. A. Halo enol lactones: studies on the mechanism of inactivation of alpha-chymotrypsin. Biochemistry 1986, 25 (6), 1436–1444. 10.1021/bi00354a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wu R.; Li J.; Wang Y.; Quan Z.; Su Y.; Huo C. Copper-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidative Dehydrogenative Ring-Opening Reaction of Glycine Esters with α -Angelicalactone: Approach to Construct α-Amino-γ-Ketopimelates. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 3436–3440. 10.1002/adsc.201900006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ogawa Y.; Kato M.; Sasaki I.; Sugimura H. Total Synthesis of (+)-Pyrenolide D. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 12315–12319. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hu B.; Cheng X.; Hu Y.; Liu X.; Karaghiosoff K.; Li P. J. Rhenium-Catalyzed Arylation–Acyl Cyclization between Enol Lactones and Organomagnesium Halides: Facile Synthesis of Indenones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 15497–15502. 10.1002/anie.202103465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nebra N.; Monot J.; Shaw R.; Martin-Vaca B.; Bourissou D. Metal–Ligand Cooperation in the Cycloisomerization of Alkynoic Acids with Indenediide Palladium Pincer Complexes. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2930–2934. 10.1021/cs401029x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Hamasaka G.; Uozumi Y. Cyclization of alkynoic acids in water in the presence of a vesicular self-assembled amphiphilic pincer palladium complex catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 14516–14518. 10.1039/C4CC07015A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tomas-Mendivil E.; Toullec P. Y.; Díez J.; Conejero S.; Michelet V.; Cardierno V. Cycloisomerization versus Hydration Reactions in Aqueous Media: A Au(III)-NHC Catalyst That Makes the Difference. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2520–2523. 10.1021/ol300811e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d García-Alvarez J.; Díez J.; Vidal C. Pd(II)-catalyzed cycloisomerisation of γ-alkynoic acids and one-pot tandem cycloisomerisation/CuAAC reactions in water. Green. Chem. 2012, 14, 3190–3196. 10.1039/c2gc36176k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; For the mechanism of Pd(II) immobilized on a heterogeneous support, see:; e Yuan N.; Gudmundsson A.; Gustafson K. P. J.; Oschmann M.; Tai C.-W.; Persson I.; Zou X.; Verho O.; Bajnóczi E. J.; Bäckvall J.-E. Investigation of the Deactivation and Reactivation Mechanism of a Heterogeneous Palladium(II) Catalyst in the Cycloisomerization of Acetylenic Acids by In Situ XAS. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 2999–3008. 10.1021/acscatal.0c04374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tomas-Mendivil E. P.; Toullec Y.; Borge J.; Conejero S.; Michelet V.; Cadierno V. Water-Soluble Gold(I) and Gold(III) Complexes with Sulfonated N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization, and Application in the Catalytic Cycloisomerization of γ-Alkynoic Acids into Enol-Lactones. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 3086–3098. 10.1021/cs4009144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Bhakta S.; Ghosh T. Gold-Catalyzed Carboxylative Cyclization Reactions: Recent Advances. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 496–505. 10.1002/ajoc.202000694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Cadierno V. Gold-Catalyzed Addition of Carboxylic Acids to Alkynes and Allenes: Valuable Tools for Organic Synthesis. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1206. 10.3390/catal10101206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Rodríguez-Alvarez M. J.; Vidal C.; Díez J.; García-Alvarez J. Introducing deep eutectic solvents as biorenewable media for Au(I)-catalysed cycloisomerisation of γ-alkynoic acids: an unprecedented catalytic system. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 12927–12929. 10.1039/C4CC05904B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Genin E.; Toullec P. Y.; Antoniotti S.; Brancour C.; Genêt J.-P.; Michelet V. Room Temperature Au(I)-Catalyzed exo-Selective Cycloisomerization of Acetylenic Acids: An Entry to Functionalized ϒ-Lactones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3112–3113. 10.1021/ja056857j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Dalla V.; Pale P. Silver-catalyzed cyclization of acetylenic alcohols and acids: a remarkable accelerating effect of a propargylic C–O bond. J. Chem. 1999, 23, 803–805. 10.1039/a903587g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Pale P.; Chuche Silver assisted heterocyclization of acetylenic compounds. J. Tet. Lett. 1987, 28, 6447–6448. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)96884-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Dalla V.; Pale P. Silver-catalyzed heterocyclization: First total synthesis of the naturally occurring cis 2-hexadecyl-3-hydroxy-4-methylene butyrolactone. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 3525–3528. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)73226-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ke D.; Espinosa N. A.; Mallet-Ladeira S.; Monot J.; Martin-Vaca B.; Bourissou D. Efficient Synthesis of Unsaturated δ- and ε-Lactones/Lactams by Catalytic Cycloisomerization: When Pt Outperforms Pd. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 2324–2331. 10.1002/adsc.201600382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cadran N.; Cariou K.; Hervé G.; Aubert C.; Fensterbank L.; Malacria M.; Marco-Contelles J. PtCl2-Catalyzed Cycloisomerizations of Allenynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 3408–3409. 10.1021/ja031892g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lemiere G.; Gandon V.; Agenet N.; Goddard J.-P.; de Kozak A.; Aubert C.; Fensterbank L.; Malacria M. Gold(I)- and Gold(III)-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization of Allenynes: A Remarkable Halide Effect. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7596–7599. 10.1002/anie.200602189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ikeuchi T.; Inuki S.; Oishi S.; Ohno H. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Cascade Cyclization Reactions of Allenynes for the Synthesis of Fused Cyclopropanes and Acenaphthenes. Angew.Chem.Int.Ed. 2019, 58, 7792–7796. 10.1002/anie.201903384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For the use of ultrasmall gold particles stabilized by polymantane ligands as precatalysts, see:; c Nasrallah H. O.; Min Y.; Lerayer E.; Nguyen T.-A.; Poinsot D.; Roger J.; Brandès S.; Heintz O.; Roblin P.; Jolibois F.; Poteau R.; Coppel Y.; Kahn M. L.; Gerber I. C.; Axet M. R.; Serp P.; Hierso J.-C. Nanocatalysts for highly selective enyne cyclization: oxidative surface reorganization of gold sub-2nm nanoparticle networks. JACS Au 2021, 1, 187–200. 10.1021/jacsau.0c00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia P.; Harrak Y.; Diab L.; Cordier P.; Ollivier C.; Gandon V.; Malacria M.; Fensterbank L.; Aubert C. Silver-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization of 1, n-Allenynamides. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2952–2955. 10.1021/ol201041h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Deng Y.; Bartholomeyzik T.; Persson A. K. Å.; Sun J.; Bäckvall J.-E. Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative Arylating Carbocyclization of Allenynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2703–2707. 10.1002/anie.201107592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Deng Y.; Bäckvall J.-E. Palladium Catalyzed Oxidative Acyloxylation/Carbocyclization of Allenynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3217–3221. 10.1002/anie.201208718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Bartholomeyzik T.; Mazuela J.; Pendrill R.; Deng Y.; Bäckvall J.-E. Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative Arylating Carbocyclization of Allenynes: Control of Selectivity and Role of H2O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8696–8699. 10.1002/anie.201404264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Bartholomeyzik T.; Pendrill R.; Lihammar R.; Jiang T.; Widmalm G.; Bäckvall J.-E. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative Arylating Carbocyclization of Allenynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 298–309. 10.1021/jacs.7b10267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Li M.-B.; Inge A. K.; Posevins D.; Gustafson K. P. J.; Qiu Y.; Bäckvall J.-E. Chemodivergent and Diastereoselective Synthesis of γ-Lactones and γ-Lactams: A Heterogeneous Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative Tandem Process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14604–14608. 10.1021/jacs.8b09562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For an account, see:; f Li M.-B.; Bäckvall J.-E. Efficient Heterogeneous Palladium Catalysts in Oxidative Cascade Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2275–2286. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zheng Z.; Deiana L.; Posevins D.; Rafi A.; Zhang K.; Johansson M. G.; Tai C.-W.; Córdova A.; Bäckvall J.-E. Efficient Heterogeneous Copper-Catalyzed Alder-Ene Reaction of Allenynamides to Pyrrolines. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 1791–1796. 10.1021/acscatal.1c05147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For selected recent examples of transition-metal catalysts immobilized on cellulose and nanocelluloses, see:; b Cirtiu C. M.; Dunlop-Briere A. F.; Moores A. Palladium NCN and CNC pincer complexes as exceptionally active catalysts for aerobic oxidation in sustainable media. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 288–291. 10.1039/C0GC00326C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Klemm D.; Kramer F.; Moritz S.; Lindström T.; Ankerfors M.; Gray D.; Dorris A. Nanocelluloses: A New Family of Nature-Based Materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 5438–5466. 10.1002/anie.201001273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kaushik M.; Moores A. Review: nanocelluloses as versatile supports for metal nanoparticles and their applications in catalysis. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 622–637. 10.1039/C5GC02500A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Shaghaleh H.; Xu X.; Wang S. Current progress in production of biopolymeric materials based on cellulose, cellulose nanofibers, and cellulose derivatives. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 825–842. 10.1039/C7RA11157F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Córdova A.; Afewerki S.; Alimohammadzadeh R.; Sanhueza I.; Tai C.-W.; Osong S. H.; Engstrand P.; Ibrahem I. A sustainable strategy for production and functionalization of nanocelluloses. Pure Appl. Chem. 2019, 91, 865–874. 10.1515/pac-2018-0204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Afewerki S.; Alimohammadzadeh R.; Osong S. H.; Tai C.-W.; Engstrand P.; Córdova A. Sustainable Design for the Direct Fabrication and Highly Versatile Functionalization of Nanocelluloses. Global Challenges 2017, 1, 1700045. 10.1002/gch2.201700045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Deiana L.; Rafi A. A.; Naidu V. R.; Tai C.-W.; Bäckvall J.-E.; Córdova A. Artificial plant cell walls as multi-catalyst systems for enzymatic cooperative asymmetric catalysis in non-aqueous media. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 8814–8817. 10.1039/D1CC02878B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Li M.-B.; Yang Y.; Rafi A. A.; Oschmann M.; Grape E. S.; Inge A. K.; Córdova A.; Bäckvall J.-E. Silver-Triggered Activity of a Heterogeneous Palladium Catalyst in Oxidative Carbonylation Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10391–10395. 10.1002/anie.202001809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fürstner A.; Davies P. W. Catalytic Carbophilic Activation: Catalysis by Platinum and Gold π Acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 3410–3449. 10.1002/anie.200604335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jiménez-Núñez E.; Echavarren A. M. Molecular diversity through gold catalysis with alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2007, 333–346. 10.1039/B612008C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Karimi B.; Esfahania F. Unexpected golden Ullmann reaction catalyzed by Au nanoparticles supported on periodic mesoporous organosilica (PMO). Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10452. 10.1039/c1cc12566d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Karimi B.; Gholinejad M.; Khorasania M. Highly efficient three-component coupling reaction catalyzed by gold nanoparticles supported on periodic mesoporous organosilica with ionic liquid framework. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 8961. 10.1039/c2cc33320a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Karimi B.; Esfahani F. K. Gold Nanoparticles Supported on the Periodic Mesoporous Organosilicas as Efficient and Reusable Catalyst for Room Temperature Aerobic Oxidation of Alcohols. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 1319–1326. 10.1002/adsc.201100802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Karimi B.; Bigdeli A.; Safari A. A.; Khorasani M.; Vali H.; Karimvand S. K. Aerobic Oxidation of Alcohols Catalyzed by in Situ Generated Gold Nanoparticles inside the Channels of Periodic Mesoporous Organosilica with Ionic Liquid Framework. ACS Comb. Sci. 2020, 22 (2), 70–79. 10.1021/acscombsci.9b00160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Karami S.; Esfahani S. K.; Karimi B. Gold nanoparticles supported on carbon coated magnetic nanoparticles; a robustness and effective catalyst for aerobic alcohols oxidation in water. Mol. Catal. 2023, 534, 112772. 10.1016/j.mcat.2022.112772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Turkevich J.; Stevenson P. C.; Hillier J. A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1951, 11, 55–75. 10.1039/df9511100055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Brust M.; Walker M.; Bethell D.; Schiffrin D. J.; Whyman R. Synthesis of thiol-derivatised gold nanoparticles in a two-phase Liquid–Liquid system. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1994, 0, 801–802. 10.1039/C39940000801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson K.; Verho O.; Nyholm L.; Oscarsson S.; Bäckvall J. E. Dispersed Gold Nanoparticles Supported in the Pores of Siliceous Mesocellular Foam: A Catalyst for Cycloisomerization of Alkynoic Acids to γ-Alkylidene Lactones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2015, 2250–2255. 10.1002/ejoc.201403664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Grass M. E.; Zhang Y.; Butcher D. R.; Park J. Y.; Li Y.; Bluhm H.; Bratlie K. M.; Zhang T.; Somorjai G. A. A Reactive Oxide Overlayer on Rhodium Nanoparticles during CO Oxidation and Its Size Dependence Studied by In Situ Ambient-Pressure X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8893–8896. 10.1002/anie.200803574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tsunoyama H.; Sakurai H.; Negishi Y.; Tsukuda T. Size-Specific Catalytic Activity of Polymer-Stabilized Gold Nanoclusters for Aerobic Alcohol Oxidation in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9374–9375. 10.1021/ja052161e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Van Rie J.; Thielemans W. Cellulose–gold nanoparticle hybrid materials. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 8525–8554. 10.1039/C7NR00400A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For immobilization on bacterial nanocellulose, see:; b Chen M.; Kang H.; Gong Y.; Guo J.; Zhang H.; Liu R. Bacterial Cellulose Supported Gold Nanoparticles with Excellent Proerties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7 (39), 21717–21726. 10.1021/acsami.5b07150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wildgoose G. G.; Banks C. E.; Compton R. G. Metal nanoparticles and related materials supported on carbon nanotubes: methods and applications. Small 2006, 2, 182–193. 10.1002/smll.200500324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Han L.; Wu W.; Kirk F. L.; Luo J.; Maye M. M.; Kariuki N. N.; Lin Y.; Wang C.; Zhong C.-J. A direct route toward assembly of nanoparticle-carbon nanotube composite materials. Langmuir 2004, 20, 6019. 10.1021/la0497907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Neatu F.; Li Z.; Richards R.; Toullec P. Y.; Genet J.-P.; Dumbuya K.; Gottfried J. M.; Steinrück H. P.; Parvulescu V. I.; Michelet V. Heterogeneous Gold Catalysts for Efficient Access to Functionalized Lactones. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 9412–9418. 10.1002/chem.200801327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shu X. Z.; Nguyen S. C.; He Y.; Oba F.; Zhang Q.; Canlas C.; Somorjai G. A.; Alivisatos A. P.; Toste F. D. Silica-Supported Cationic Gold(I) Complexes as Heterogeneous Catalysts for Regio- and Enantioselective Lactonization Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7083–7086. 10.1021/jacs.5b04294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Huang Q.-A.; Ikeda T.; Haruguchi K.; Kawai S.; Yamamoto E.; Murayama H.; Ishida T.; Honma T.; Tokunaga M. Intramolecular cyclization of alkynoic acid catalyzed by Na-salt-modified Au nanoparticles supported on metal oxides. Applied Catalysis A, General 2022, 643, 118765 10.1016/j.apcata.2022.118765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Hulea V.; Dumitriu E. In Nanomaterials in Catalysis, 1st ed.; Serp P., Phillipot K., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: 2013; pp 375–413. [Google Scholar]; c Barakat T.; Rooke J. C.; Tidahy H. L.; Hosseini M.; Cousin R.; Lamonier J.-F.; Giraudon J.-M.; De Weireld G.; Su B.-L.; Siffert S. Noble-Metal-Based Catalysts Supported on Zeolites and Macro-Mesoporous Metal Oxide Supports for the Total Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 1420–1430. 10.1002/cssc.201100282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Engström K.; Johnston E. V.; Verho O.; Gustafson K. P. J.; Shakeri M.; Tai C.-W.; Bäckvall J.-E. Co-immobilization of an Enzyme and a Metal into the Compartments of Mesoporous Silica for Cooperative Tandem Catalysis: An Artificial Metalloenzyme. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 14006–14010. 10.1002/anie.201306487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Görbe T.; Gustafson K. P.; Verho O.; Kervefors G.; Zheng H.; Zou X.; Johnston E. V.; Bäckvall J.-E. Design of a Pd(0)-CalB CLEA Biohybrid Catalyst and Its Application in a One-Pot Cascade Reaction. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1601–1605. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Gustafson K. P. J.; Görbe T.; De Gonzalo G.; Yuan N.; Schreiber C.; Shchukarev A.; Tai C.-W.; Persson I.; Zhou X.; Bäckvall J.-E. Chemoenzymatic Dynamic Kinetic Resolution of Primary Benzylic Amines using Pd0-CalB CLEA as a Biohybrid Catalyst. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 9174–9179. 10.1002/chem.201901418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gustafson K. P. J.; Lihammar R.; Verho O.; Engström K.; Bäckvall J.-E. J. Chemoenzymatic Dynamic Kinetic Resolution of Primary Amines Using a Recyclable Palladium Nanoparticle Catalyst Together with Lipases. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 3747–3751. 10.1021/jo500508p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Deiana L.; Jiang Y.; Palo-Nieto C.; Afewerki S.; Incerti-Pradillos C. A.; Verho O.; Tai C.-W.; Johnston E. V.; Córdova A. Combined heterogeneous metal/chiral amine: multiple relay catalysis for versatile eco-friendly. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3447–3451. 10.1002/anie.201310216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Palo-Nieto C.; Afewerki S.; Andersson M.; Tai C.-W.; Berglund P.; Córdova A. Integrated Heterogeneous Metal/Enzymatic Multiple Relay Catalysis for Eco-Friendly and Asymmetric Synthesis. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3932–3940. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Deiana L.; Afewerki S.; Palo-Nieto C.; Verho O.; Johnston E. V.; Córdova A. Highly Enantioselective Cascade Transformations by Merging Heterogeneous Transition Metal Catalysis with Asymmetric Aminocatalysis. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2 (851), 1–7. 10.1038/srep00851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The MCC: Avicel Ph 101 can be obtained for 2.00 US$-3.50 US$/kilogram (20 kg min order) and for laboratory use (Avicel PH101, Merck) for 137.00 US$/kilogram.

- The reactions were carried out under nitrogen, but control experiments showed that the reaction also works under air, giving the same yield. In other control experiments the presence of base was tested. The use of K2CO3 as base gave a very low yield. Even with catalytic amounts of K2CO31a gave only 9% of 2a after 30 h in a control experiment carried out as in Scheme 2.

- The recycling experiments were carried out with 1.28 mol % of catalyst to avoid too much loss of recovered catalyst. It turned out to be difficult to recycle 0.32 mol % of the catalyst (5 mg of powder) due to cloud formation when removing the liquid from the centrifuged catalyst; small amounts of the powder are removed together with the liquid due to some suspension. However, we have run three cycles anyway with 0.32 mol % of catalyst. The results show that we obtained quantitative yields in all three cycles. In the fourth cycle it was evident by inspection by the eye that the amount of the powder had become less and the subsequent cycle did not give full conversion.

- a Although the results from the hot filtration supports a heterogeneous pathway, one cannot completely rule out the possibility that potential soluble species are redepositing on the support during the filtration. With immobilized palladium catalysts, techniques have been developed to poison the homogeneous fraction by e.g. using polyvinyl pyridine (PVP) due to the very strong Pd–N bonds.29b,29c However, with gold this poisoning technique is not possible due to the very weak Au–N bonds.; b Richardson J. M.; Jones C. W. Poly(4-vinylpyridine) and Quadrapure TU as Selective Poisons for Soluble Catalytic Species in Palladium-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions – Application to Leaching from Polymer-Entrapped Palladium. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006, 348, 1207–1216. 10.1002/adsc.200606021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Karimi B.; Akhavan P. F. A Study on Applications of N-Substituted Main-Chain NHC-Palladium Polymers as Recyclable Self-Supported Catalysts for the SuzukiMiyaura Coupling of Aryl Chlorides in Water. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 6063–6072. 10.1021/ic2000766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.