Abstract

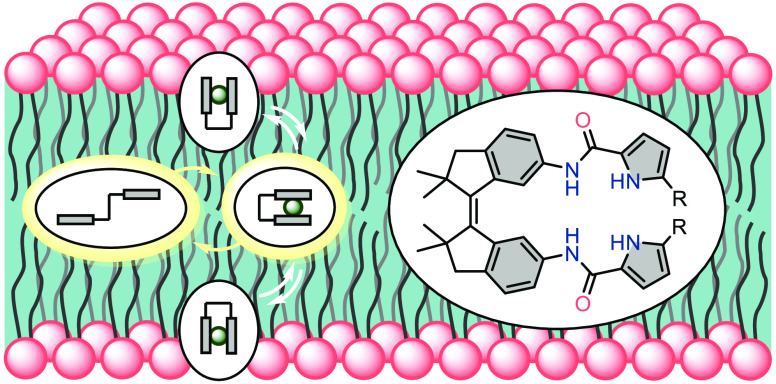

Toward photocontrol of anion transport across the bilayer membrane, stiff-stilbene, which has dimethyl substituents in the five-membered rings, is functionalized with amidopyrrole units. UV–vis and 1H NMR studies show high photostability and photoconversion yields. Where the photoaddressable (E)- and (Z)-isomers exhibit comparable binding affinities, as determined by 1H NMR titrations, fluorescence-based transport assays reveal significantly higher transport activity for the (Z)-isomers. Changing the binding affinity is thus not a necessity for modulating transport. Additionally, transport can be triggered in situ by light.

Driven by the important role of anions in many biological processes, a large number of artificial anion receptors have been developed.1 These receptors have found applications in analyte sensing,2 wastewater extraction,3 and transmembrane transport.4 With respect to the latter, defects in anion transport by proteins have been linked to serious illnesses (e.g., cystic fibrosis), and synthetic systems with transport capabilities therefore have therapeutic potential.5 Although a number of synthetic receptors have been shown to facilitate anion transport, they usually do not exhibit stimulus-controlled conformational changes, which are a hallmark of proteins. To endow them with stimulus-responsive properties remains a fundamental challenge,6,7 and current approaches are primarily based on the control of the binding affinity, which presumably translates into transport activity. The use of light to control transport activity is advantageous, as it can be applied with high spatiotemporal precision and does not produce chemical waste.8 Indeed, a significant amount of light-responsive anion receptors have been developed over the past decade,9 and a small number of them were shown to be capable of mediating transmembrane transport.7 The groups of Jeong7a and Langton,7b for example, demonstrated light-controlled chloride transport using azobenzene appended with (thio)urea and squaramide groups, respectively. Furthermore, in collaboration with the group of Gale, we recently described the photocontrol of membrane transport as well as the potential use of stiff-stilbene-derived bis(thio) urea receptors.7f Nevertheless, crucial design parameters for light-controllable anion receptors still need to be identified, and furthermore exploration of other binding motifs as well as improvement of photoswitching properties are needed in order to get closer to practical (and biological) applications.

Among extensively studied pyrrole-containing receptors,10 amidopyrroles have been used successfully in anion binding and, in one case, also in transmembrane transport.11 We envisioned that functionalizing stiff-stilbene with amidopyrrole units in the 6,6′-positions would create a suitable anion binding pocket in the (Z)-isomer, whereas in the (E)-isomer the binding units would be far apart from each other, thus leading to inferior binding and transport behavior. Our group demonstrated previously that stiff-stilbene provides an excellent scaffold for designing photoswitchable receptors due to its high structural rigidity, large geometrical change upon isomerization, and very good thermal stability.7f,12b In the present design, dimethyl substituents were incorporated into the five-membered rings to increase steric crowding in the vicinity of the central double bond, which was shown in two other cases to improve photostationary state (PSS) ratios as well as resistance to fatigue.13

Herein, we describe bis(amidopyrrole) receptors 1 and 2 (Scheme 1), where the electron-withdrawing CF3 groups were introduced into the latter compound to enhance NH proton acidity. Both receptors display robust bidirectional photoswitching, and while their (E)- and (Z)-isomers have virtually no difference in anion (i.e., acetate and chloride) binding affinity, they do display significantly different chloride transport activity. As a result, transmembrane transport can be activated in situ by light irradiation. Our results illustrate that affinity control is not a necessity for modulating transport activity, which is important to consider in future designs of photoresponsive transmembrane transporters. Such transporters could potentially be applied as light-controlled physiological tools or therapeutic agents.

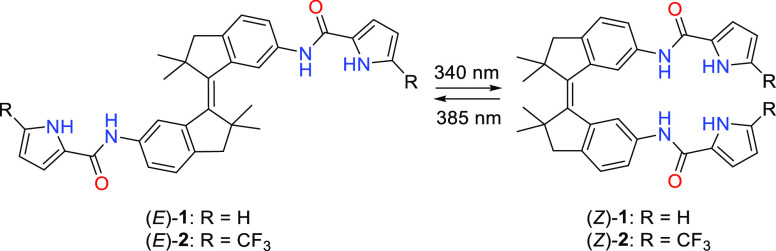

Scheme 1. Photoisomerization of Bis(amidopyrroles) 1 and 2.

The synthesis of bis(amidopyrrole) receptors 1 and 2 is outlined in Scheme 2. The starting 6-bromo-2,2-dimethyl-1-indanone (3) was prepared according to a procedure described by the group of Diederich.14 McMurry homocoupling of this indanone yielded dibromo-substituted (E)-4. Subsequent Buchwald–Hartwig amination gave compound (E)-5, which was reacted with the respective pyrrole-carboxylic acid using HBTU to afford the bis(amidopyrrole) receptors (E)-1 and (E)-2. Where pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid is commercially available, its trifluoromethylated derivative 7 was obtained by treatment of methyl 2-pyrrole-carboxylate with sodium triflinate in the presence of tert-butyl hydroperoxide, which was followed by cleavage of the methyl ester using TMSCl/NaI. The (Z)-isomers of the bis(amidopyrrole) receptors were generated from the corresponding (E)-isomers by 340 nm irradiation in a chloroform solution. The resulting E/Z mixture was separated by column chromatography (see the SI for synthetic details and characterization).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Bis(amidopyrrole) Receptors.

(i) Zn, TiCl4, THF, reflux; (ii) benzophenone imine, Pd(OAc)2, DPPF, NaOtBu, toluene, 90 °C; (iii) 2 M aqueous HCl, THF; (iv) pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid or compound 7, HBTU, DIPEA, CH2Cl2; (v) 340 nm light irradiation, CHCl3; (vi) CF3SO2Na, tBuOOH, CH2Cl2/H2O 7:3; (vii) NaI, TMSCl, MeCN, reflux.

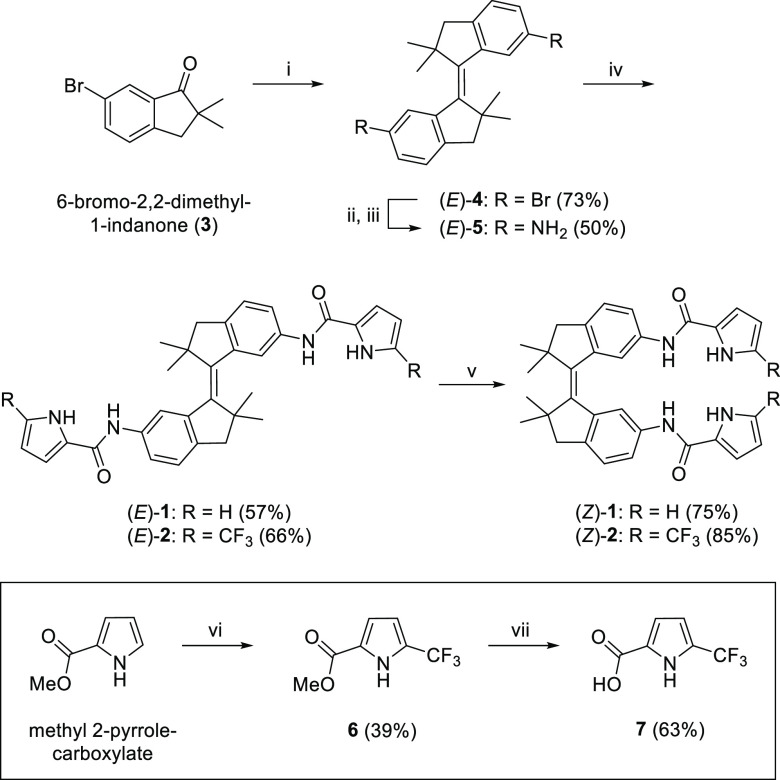

The photoswitching behavior of 1 and 2 was first studied by UV–vis spectroscopy in a DMSO solution. Both (E)-isomers showed absorption maxima at around 290 and 350 nm (Figure 1A and B). Irradiation with 365 nm light led to a decrease in these maxima and a small increase in the longer wavelength absorption, indicating formation of the respective (Z)-isomers.12b The spectra changed further by subsequent 340 nm irradiation, revealing higher conversion toward the (Z)-isomers with this wavelength. The opposite spectral changes were observed when 385 nm was then used, demonstrating reversibility of the isomerization process. In all cases, irradiation was halted when no further changes in absorption were observed, indicating that the photostationary states (PSS) had been reached. Importantly, clear isosbestic points were maintained during irradiation, illustrative of a unimolecular isomerization process (Figures S21–S24). Furthermore, alternation of 340 and 385 nm irradiation showed excellent fatigue resistance (Figure 1C and D).15

Figure 1.

(A) UV–vis spectral changes of (E)-1 upon sequential irradiation with 365 (10 s), 340 (140 s), and 385 nm (180 s) light and (B) UV–vis spectral changes of (E)-2 upon sequential irradiation with 365 (10 s), 340 (120 s), and 385 nm (120 s) light (c = 2.0 × 10–4 M in degassed DMSO). The absorption change (at λ = 345 nm) upon multiple 340/385 nm irradiation cycles starting with (C) (E)-1 and (D) (E)-2 is also shown.

Next, 1H NMR studies were performed to determine the PSS ratios. Irradiation of the (E)-isomers in DMSO-d6 with 340 nm light led to the formation of new sets of 1H NMR signals, which were assigned to the respective (Z)-isomers (Figures S25 and S26). By subsequent irradiation with 385 nm light, the (E)-isomers were partially recovered. The PSS340 and the PSS385 (E/Z) ratios were determined as 19:81 and 82:18 for 1 and as 23:77 and 83:17 for 2, respectively. Using the UV–vis absorbance data, PSS365 (E/Z) ratios of 40:60 for 1 and 45:55 for 2 were derived. Similar ratios have been reported for other stiff-stilbene derivatives containing dimethyl substituents in the five-membered rings.9a,12b,13,16

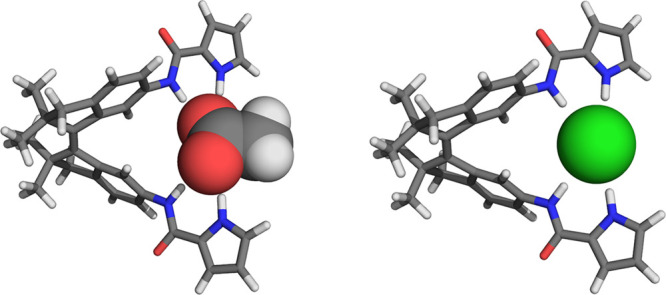

The possibility of the (Z)-isomer to form 1:1 complexes with either acetate or chloride was first assessed by DFT geometry optimizations (Figure 2 and Tables S1 and S2 for details). These anions were chosen because they have previously been found to give 1:1 binding with structurally related stiff-stilbene-based urea receptors, which additionally were shown to be capable of mediating transmembrane chloride transport.7f,9g The energy-minimized structure of (Z)-1⊂AcO– displayed amide and pyrrole N(H)···O hydrogen bond distances of 2.89 and 2.76 Å, respectively, and a central CPh—C=C—CPh dihedral angle of ϕ = 20.6°. For the chloride-bound complex, hydrogen bond lengths were longer (i.e., N(H)···Cl– distances of 3.38 and 3.27 Å for amide and pyrrole, respectively), while the dihedral angle was slightly smaller (ϕ = 18.8°). From these calculations, 1:1 binding of the (Z)-isomer with both anions thus seemed viable.

Figure 2.

DFT-optimized molecular geometries of (Z)-1⊂AcO– (left) and (Z)-1⊂Cl– (right) at the B3LYP/6-31G++(d,p) level of theory using an IEF-PCM (DMSO) solvation model.

The binding strength of these anions was quantified by 1H NMR spectroscopic titrations in DMSO-d6/0.5%H2O. Addition of their NBu4+ salts to the bis(amidopyrrole) receptors resulted in downfield shifting of the signals belonging to the amide and pyrrole NH protons, illustrating involvement in hydrogen bonding (Figures S27–S34). Furthermore, small chemical shift changes of the aromatic signals were noted. An exception was the titration of (E)-2 and (Z)-2 with AcO–, which resulted in the disappearance of the pyrrole NH signal, most likely as a sign of deprotonation.10a In contrast to what was expected based on the DFT modeling, modified Job’s plot analysis for the titration of AcO– to (Z)-1 hinted at a 1:2 binding stoichiometry. The same stoichiometry was deduced for (E)-1 (Figures S36–S37). The titration data were therefore fitted to a 1:2 binding model (using HypNMR)17 by treating the two amidopyrrole binding sites as equal (cooperativity factor α = 1, see Figure S35 and Figures S38–S43 in the SI for details). Interestingly, the obtained binding constants for both isomers were comparable [K11 = 98 M–1 and 102 M–1 for (E)-1 and (Z)-1, respectively].

Fitting the data for Cl– binding using a 1:2 binding model also gave virtually the same association constants for both isomers and, moreover, revealed very weak binding [K11 ∼ 3–4 M–1 for (E)-1 and (Z)-1]. Nevertheless, the binding strength was slightly enhanced by the presence of electron-withdrawing CF groups, as can be expected on the basis of increased NH proton acidities [K11 ∼ 6 M–1 for (E)-2 and (Z)-2]. For the (E)-isomer, 1:2 binding was anticipated, since the binding motifs are too far apart from each other to bind a single anion simultaneously. It appears that for the (Z)-isomer such simultaneous binding is also disfavored, which contrasts our previous findings with stiff-stilbene-based bis(urea) receptors. The difference may be ascribed tentatively to an enlarged dihedral angle as compared to that of regular stiff-stilbene,9g which is caused by the steric crowding of the dimethyl-substituents attached to the five-membered rings.

In spite of the weak binding and comparable affinities for the photoaddressable isomers, the capability of receptors 1 and 2 to mediate chloride transport was validated in an 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonate (HPTS) assay (see the SI for details).18 Initially, the compounds were added as DMSO solutions to POPC vesicles (200 nm mean diameter), which were loaded with the pH-sensitive HPTS fluorescent dye in an aqueous NaCl solution buffered to pH 7.0, whereafter a NaOH base pulse was applied to generate a pH gradient. In the presence of sufficient amounts of receptor, the pH gradient dissipated, which occurs by receptor-mediated Cl–/H+ symport or Cl–/OH– antiport (as indicated by the change in HPTS emission; see Figures S44–S51). Concentration-dependent runs and fitting of the data to the Hill equation revealed the half-maximal effective concentration values (EC50; see Table 1). From these studies, both receptors appeared to have a moderate activity. However, for the CF3-functionalized receptor 2, 100% chloride efflux was never reached, even at the highest loading (10 mol %), which could indicate issues with membrane solubility or deliverability.18b

Table 1. Chloride Transport Activity (EC50)a of Compounds 1 and 2.

| postadded |

preincorporated |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | EC50(E) (mol %) | EC50(Z) (mol %) | EC50(E) (mol %) | EC50(Z) (mol %) |

| 1 | 3.11 | 1.71 | 3.20 | 1.69 |

| 2 | 1.70 | 0.53 | 0.26 | 0.062 |

Defined as the transporter-to-lipid molar ratio (mol %) needed to reach 50% of the maximum possible chloride efflux.

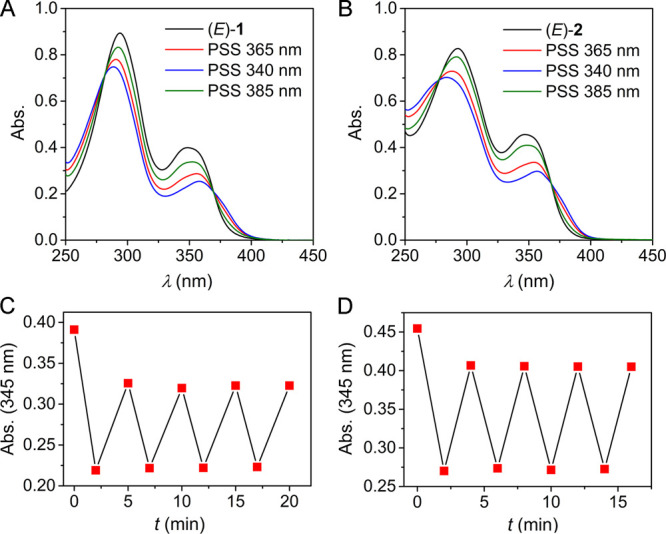

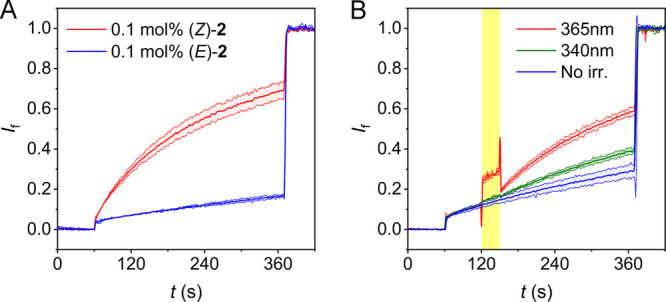

The HPTS assay was therefore repeated with the compounds preincorporated into the POPC lipid bilayer. For receptor 1, the activities were virtually unaltered with respect to postaddition, and it was confirmed that the (Z)-isomer is more active than the (E)-isomer (1.9-fold). For 2 instead, now maximum efflux was reached (at 1 mol % loading) and, gratifyingly, the (Z)-isomer turned out to be an active transporter, whereas the (E)-isomer displayed a 4.1-fold lower activity. Interestingly, the EC50 value of (Z)-2 is in the same range as that determined previously for our stiff-stilbene bis(thio)ureas,7f as well as for azobenzene-based bis(squaramides),7b,7e while its chloride binding affinity is lower. Furthermore, in contrast to previously reported photoswitchable transporters, the binding affinities of both isomers are similar in this case, and still the (Z)-isomer is significantly more active than the (E)-isomer (Figure 3A). This higher activity is proposed to originate from other factors contributing to transport efficiency such as a better mobility and partioning in the membrane,7,19 in addition to an improved anion encapsulation ability.20

Figure 3.

Plot of the fractional fluorescence intensity (If) as a measure of chloride transport (A) facilitated by (Z)-2 and (E)-2 (0.1 mol %, preincorporated) and (B) starting with (E)-2 (0.1 mol %) and activation by in situ irradiation using 340 or 365 nm light for 30 s.21

In the same HPTS assay, control over transport activity by in situ irradiation was demonstrated. Compound (E)-2 was preincorporated into POPC vesicles and, 60 s after the base pulse was applied, irradiation at 340 or 365 nm for 30 s led to the enhancement of transport (Figure 3B), which is explained by isomerization to the more active (Z)-2. The largest effect was observed with the longer wavelength, which is likely explained by higher conversion to the active isomer within the short irradiation time. It should be noted here that although the PSS ratio is lower upon irradiation with 365 nm light than that with 340 nm light, the PSS is reached much faster with the former wavelength (Figure 1B).22

Finally, chloride transport facilitated by the more active (Z)-isomers was additionally studied in a cationophore-coupled ion-selective electrode (ISE) assay using POPC vesicles (200 nm mean diameter) with an internal buffered KCl solution and suspended in a buffered KGlu solution (pH 7.2, see the SI for details).18a The chloride gradient was dissipated by preincorporated (Z)-isomers after the addition of either monensin or valinomycin, showing that they are capable of both electroneutral and electrogenic transport (Figures S55 and S56). Only slightly faster efflux was observed when coupled to the latter cationophore, revealing that there is no significant Cl– uniport selectivity.

In summary, two bis(amidopyrrole)-functionalized stiff-stilbene derivatives, having dimethyl-substituted five-membered rings, were synthesized. These derivatives could be effectively switched between (E)- and (Z)-isomers using 340/385 nm light, showing improved PSS ratios and fatigue resistance in comparison to regular stiff-stilbene derivatives. Although similar binding affinities were determined for the photoaddressable isomers, they exhibited distinct chloride transport activities. Consequently, transport could be activated in situ by light. In this system, the change in transport activity upon isomerization is clearly governed by factors other than binding affinity, which is important to take into account in the future design of light-responsive transporters. Hence, our results open a new perspective on the development of photoactivatable transporters, which could potentially be applied as physiological tools or therapeutic agents to study and treat diseases by facilitating the passage of anions across the lipid bilayer membrane.

Experimental Section

General Methods and Materials

THF, MeCN, and CH2Cl2 were dried using a Pure Solve 400 solvent purification system from Innovative Technology. Dry DMSO and toluene were purchased from Acros Organics, and DMSO-d6, MeCN-d3 and CDCl3 were purchased from Eurisotop. DMSO-d6 was stored under N2 over molecular sieves (4 Å). The degassing of the solvents was carried out by purging with N2 for 30 min unless noted otherwise. 6-Bromo-2,2-dimethyl-1-indanone (3) was prepared using a procedure reported in the literature.14 All other chemicals were commercial products and were used without further purification. Column chromatography was performed using silica gel (SiO2) purchased from Screening Devices BV (Pore diameter 55–70 Å, surface area 500 m2 g–1). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on aluminum sheets coated with silica 60 F254 and neutral aluminum oxide obtained from Merck. Compounds were visualized with UV light (254 nm) or by staining with potassium permanganate. 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AV 400 and Bruker 500 Ultra Shield instruments at 298 K unless indicated otherwise. Chemical shifts (δ) are denoted in parts per million (ppm) relative to residual protiated solvent (DMSO-d6, δ = 2.50 and 39.52 ppm for 1H detection and 13C detection, respectively; CDCl3, δ = 7.26 and 77.16 ppm; for 1H detection and 13C detection, respectively). The splitting pattern of peaks is designated as follows: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), p (quintet), h (septet), m (multiplet), and br (broad). High-resolution mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was performed on a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive HF spectrometer with ESI ionization. IR spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer Spectrum Two FT-IR spectrometer. The wavenumber (ν) is in units of reciprocal centimeters (cm–1), and the intensity is designated as follows: s (strong), m (medium), w (weak), very w (very weak), br (broad), and sh (shoulder). Melting points were determined with a Büchi M560 apparatus. UV–vis spectra were recorded on an Agilent Cary 8454 spectrometer using 1 cm or 1 mm quartz cuvettes. Fluorescence was measured on a JASCO FP-8500 spectrofluorimeter using 1 cm PS cuvettes. Irradiation of samples was carried out using Thorlabs model M340F3 (0.85 mW, λem = 340 ± 6 nm), M365F1 (4.1 mW, λem = 365 ± 4 nm), and M385F1 (9.0 mW, λem = 385 ± 5 nm) instruments positioned at a distance of 1 cm to the sample unless noted otherwise.

(E)-6,6′-Dibromo-2,2,2′,2′-tetramethyl-2,2′,3,3′-tetrahydro-1,1′-biindenylidene [(E)-4]

First, TiCl4 (5.50 mL, 50.1 mmol) was slowly added to a vigorously stirred suspension of Zn (6.56 g, 100 mmol) in dry THF (60 mL) under a N2 atmosphere. The solution was stirred at reflux for 2 h using an oil bath and then cooled to rt. Subsequently, compound 3 (5.99 g, 25.1 mmol) was added to the black suspension, and the mixture was stirred at reflux for 16 h using and oil bath, cooled to rt, treated with saturated aqueous NH4Cl solution (60 mL), and extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 150 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. Purification by column chromatography (SiO2, pentane) afforded (E)-4 (4.06 g, 73%) as a white solid; Rf = 0.63 (SiO2, pentane); mp 162.5–163.7 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 7.57 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 2.72 (s, 4H), 1.31 (s, 12H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 146.2, 144.7, 144.2, 130.8, 130.2, 125.9, 118.7, 51.5, 51.3, 27.8 ppm; IR (ATR) ν = 2971 (w, sh), 2955 (m), 2926 (w), 2901 (w), 1591 (m), 1564 (w), 1463 (s), 1402 (m), 1382 (m), 1369 (m), 1320 (m), 1274 (m), 1252 (w), 1164 (m), 1095 (w), 1067 (s), 889 (m, sh), 882 (s), 652 (m), 627 (m), 609 (m) cm–1.

(E)-2,2,2′,2′-Tetramethyl-2,2′,3,3′-tetrahydro-[1,1′- biindenylidene]-6,6′-diamine [(E)-5]

Compound (E)-4 (2.03 g, 4.55 mmol), palladium(II) acetate (0.16 g, 0.73 mmol), DPPF (0.25 g, 0.45 mmol), and sodium tert-butoxide (0.88 g, 9.1 mmol) were placed in a Schlenck tube and brought under N2 via three vacuum/N2 cycles. Then, to the reaction mixture was added dry and degassed toluene (25 mL), followed by benzophenone imine (1.91 mL, 11.4 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at 90 °C for 21 h using an oil bath, cooled to rt, and diluted with water (30 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with CHCl3 (3 × 125 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. Purification by column chromatography (SiO2, 0.1% NEt3 in CH2Cl2) afforded the imine intermediate as a yellow oil. Subsequently, this imine intermediate was redissolved in THF (100 mL), and to the mixture was added a 2 M aqueous HCl solution (50 mL). The mixture was stirred for 1 h at rt, diluted with H2O (100 mL), and extracted with Et2O (3 × 60 mL) to remove excess of benzophenone imine formed during the reaction. The resulting water layer was treated with K2CO3 (pH ∼ 10) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 60 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated to afford (E)-5 (0.72 g, 50%) as a white solid. Rf = 0.59 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/EtOAc 1:1); mp 182.2–183.3 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 6.84 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 6.72 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 2H), 6.39 (dd, J = 7.9, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 4.84 (s, 4H), 2.58–2.53 (m, 4H), 1.25 (s, 12H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 145.9, 145.4, 143.0, 132.3, 124.0, 113.6, 113.5, 51.0, 50.2, 27.6 ppm; IR (ATR) ν = 3423 (w), 3330 (w), 2975 (w, sh), 2953 (m, sh), 2943 (m), 2921 (m), 2900 (m), 2856 (w, sh), 2844 (w, sh), 1695 (very w) 1618 (m, sh), 1607 (m), 1583 (m), 1486 (s), 1466 (w, sh), 1454 (m), 1379 (w), 1361 (m), 1328 (m), 1252 (m), 1189 (m), 1066 (br, m), cm–1; HRMS (ESI) m/z 319.2165 ([M + H]+, calcd for C22H27N2+ 319.2168).

(E)-N,N′-(2,2,2′,2′-Tetramethyl-2,2′,3,3′-tetrahydro-[1,1′-biindenylidene]-6,6′-diyl) Bis(1H -pyrrole-2-carboxamide) [(E)-1]

Compound (E)-5 (100 mg, 0.314 mmol) and 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid (84 mg, 0.75 mmol) were placed in an oven-dried two-neck flask under a N2 atmosphere. Then, dry and degassed CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added, followed by HBTU (272 mg, 0.716 mmol) and DIPEA (263 μL, 1.51 mmol). The mixture was stirred at rt for two days, diluted with H2O (10 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (5 × 15 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with 1M aqueous HCl solution (10 mL) and brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated. Purification by column chromatography (SiO2, pentane/EtOAc 70:30) afforded (E)-1 (90 mg, 57%) as a white solid; Rf = 0.30 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH 98:2); mp 285.8–286.7 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 11.74 (s, 2H), 9.71 (s, 2H), 8.24 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.07–7.03 (m, 2H), 6.96–6.91 (m, 2H), 6.18–6.13 (m, 2H) 2.72 (s, 4H), 1.35 (s, 12H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 159.3, 149.9, 142.5, 139.5, 136.6, 126.2, 124.0, 122,4, 119.4, 119.2, 111.2, 108.9, 51.2, 50.8, 27.4 ppm; IR (ATR) ν = 3297 (w), 2957 (very w), 1648 (m), 1626 (m), 1614 (w, sh), 1587 (m), 1572 (w, sh), 1549 (m), 1524 (s), 1486 (m), 1444 (m), 1420 (m), 1345 (m), 1315 (m), 1260 (m), 1214 (w), 1197 (m), 1122 (m), 1045 (w) cm–1; HRMS (ESI) m/z 505.2596 ([M + H]+, calcd for C32H33N4O2+ 505.2598).

(Z)-N,N′-(2,2,2′,2′-Tetramethyl-2,2′,3,3′-tetrahydro-[1,1′-biindenylidene]-6,6′-diyl) Bis(1H-pyrrole-2-carboxamide) [(Z)-1]

Compound (E)-1 (16 mg, 0.032 mmol) was placed in an open round-bottom flask under a constant N2 flow and dissolved in degassed CHCl3 (38 mL). The solution was irradiated with a Thorlab model M340F3 LED (0.85 mW) through the opening of the round-bottom flask while stirring for 3 h at rt and keeping the volume constant by adding more CHCl3. Purification by column chromatography (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH 98:2) afforded (Z)-1 (12 mg, 75%) as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.41 (SiO2, CH2Cl2/MeOH 98:2); mp 320.1–320.9 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 11.46 (s, 2H), 9.43 (s, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (dd, J = 8.0, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.90–6.82 (m, 4H), 6.07–6.02 (m, 2H), 3.08–3.01 (m, 2H), 2.56–252 (m, 2H), 1.62 (s, 6H), 1.16 (6H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 158.8, 144.5, 143.0, 139.7, 136.2, 126.1, 124.4, 122.1, 120.5, 118.6, 111.1, 108.8, 51.4, 50.0, 28.7, 26.2 ppm; IR (ATR) ν = 3424 (very w), 3243 (br, m), 2988 (w, sh), 2923 (m), 1639 (w, sh), 1616 (m), 1594 (m), 1569 (m), 1551 (m), 1514 (br. s), 1440 (s), 1416 (m, sh), 1403 (m), 1333 (br. s), 1291 (m, sh), 1269 (m), 1229 (m), 1170 (m), 1143 (m), 1107 (m), 1092 (m), 1082 (m), 1046 (m), 1031 (m) cm–1; HRMS (ESI) m/z 505.2596 ([M + H]+, calcd for C32H33N4O2+ 505.2598).

Methyl 5-(Trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylate (6)

Methyl 2-pyrrolecarboxylate (1.0 g, 8.0 mmol) and sodium triflinate (4.99 g, 32.0 mmol) were dissolved in 10 mL of CH2Cl2/H2O (7:3 v/v). Subsequently, a tert-butyl hydroperoxide solution (70 wt % in H2O, 8.81 mL, 91.4 mmol) was added dropwise at rt. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 24 h, treated with a saturated aqueous Na2SO3 solution (50 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 100 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine (50 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. Purification by column chromatography (SiO2, petroleum ether/EtOAc 90:10) afforded 6 (0.60g, 39%) as a white solid; Rf = 0.30 (SiO2, petroleum ether/EtOAc 90:10); mp 87.6–89.0 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 10.18 (s, 1H), 6.91–6.83 (m, 1H), 6.63–6.55 (m, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 161.5, 125.1, 121.9, 115.1, 111.0, 52.3; 19F NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ = −60.15 ppm; IR (ATR) ν = 3262 (m), 2965 (very w) 2916 (w), 2849 (w), 1699 (s), 1578 (w), 1461 (w), 1437 (m), 1279 (s), 1259 (m, sh), 1204 (m), 1155 (s), 1117 (w, sh), 1104 (s), 1047 (m) cm–1. HRMS (ESI) m/z 194.0422 ([M + H]+, calcd for C7H7F3NO2+ 194.0423).

5-(Trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid (7)

Compound 6 (0.50 g, 2.6 mmol) and NaI (0.97 g, 6.5 mmol) were placed in an oven-dried three-neck flask and brought under a N2 atmosphere. Then, dry and degassed MeCN (30 mL) was added, followed by TMSCl (0.82 mL, 6.5 mmol). The mixture was stirred at reflux for 41 h using an oil bath, after which the solvent was evaporated. The resulting brown solid was triturated with EtOAc (150 mL) and filtered. The filtrate was washed with brine (3 × 30 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated. Purification by column chromatography (SiO2, petroleum ether/EtOAc/AcOH 79:20:1) afforded a yellow oil, which was dissolved in H2O (10 mL). Then, to the mixture was added saturated aqueous Na2CO3 solution (30 mL) (pH ∼ 10), and organic impurities were extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). The aqueous layer was then treated with 6 M aqueous HCl solution (pH ∼ 1) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL), and the combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated to afford 7 (294 mg, 63%) as a white solid; Rf = 0.30 (SiO2, petroleum ether/EtOAc/AcOH 70:29:1); mp 106.5–108.3 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 10.32 (s, 1H), 9.65 (s, 1H), 7.06–6.99 (m, 1H), 6.67–6.61 (m, 1H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 165.4, 124.1, 121.6, 118.9, 117.3, 111.5; 19F NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3) δ = −60.32 ppm; IR (ATR) ν = 3196 (br. m), 1675 (s), 1645 (m, sh), 1571 (m), 1527 (w), 1508 (w), 1459 (w), 1432 (very w, sh), 1404 (m), 1327 (m), 1281 (w, sh), 1264 (s), 1257 (s), 1233 (s), 1200 (w, sh), 1169 (s), 1112 (s), 1103 (w, sh), 1043 (s) cm–1; HRMS (ESI) m/z 178.0115 ([M – H]−, calcd for C6H3F3NO2– 178.0121).

(E)-N,N′-(2,2,2′,2′-Tetramethyl-2,2′,3,3′-tetrahydro-[1,1′-biindenylidene]-6,6′-diyl) Bis(5-(trifluoromethyl)-1H -pyrrole-2-carboxamide) [(E)-2]

Compound (E)-4 (100 mg, 0.314 mmol) and acid 6 (135 mg, 0.754 mmol) were placed in an oven-dried two-neck flask and brought under a N2 atmosphere. Then, dry and degassed CH2Cl2 (5 mL) was added, followed by HBTU (272 mg, 0.717 mmol) and DIPEA (263 μL, 1.51 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred at rt for three days, diluted with H2O (10 mL), and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 30 mL). The organic phase was washed with a 1 M aqueous HCl solution (10 mL) and H2O (10 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. Purification by column chromatography (SiO2, pentane/EtOAc 90:10) afforded (E)-2 as a white solid (133 mg, 66%); Rf = 0.40 (SiO2, pentane/iPrOH 95:5); mp 237.8–238.7 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 12.99 (s, 2H), 10.02 (s, 2H), 8.23 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.1, Hz, 2H), 7.12–7.08 (m, 2H), 6.71–6.67 (m, 2H), 2.74 (s, 4H), 1.36 (s, 12H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 158.4, 145.9, 142.5, 140.1, 136.0, 130.1, 124.1, 122.6, 122.2 119.6, 119.5, 110.9, 110.3, 51.1, 50.7, 27.3 ppm; 19F NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3) δ = −57.75 ppm; IR (ATR) ν = 3319 (w), 3154 (very w), 2925 (w), 1604 (s), 1583 (w, sh), 1545 (s), 1484 (m), 1414 (m), 1366 (m, sh), 1350 (m), 1325 (w, sh), 1311 (s), 1261 (s), 1172 (s), 1144 (m), 1116 (s), 1105 (s), 1039 (m) cm–1; HRMS (ESI) m/z 641.2341 ([M + H]+, calcd for C34H31F6N4O2+ 641.2345).

(Z)-N,N′-(2,2,2′,2′-Tetramethyl-2,2′,3,3′-tetrahydro-[1,1′-biindenylidene]-6,6′-diyl) Bis(5-(trifluoromethyl)-1H -pyrrole-2-carboxamide) [(Z)-2]

Compound (E)-2 (20 mg, 0.031 mmol) was dissolved in degassed CHCl3 (38 mL) in an open round-bottom flask under constant N2. The solution was irradiated with a Thorlab model M340F3 LED (0.85 mW) through the opening of the round-bottom flask while stirring for 3 h at rt and keeping the volume constant by adding more CHCl3. Purification by column chromatography (SiO2, pentane/iPrOH 95:5) afforded (Z)-2 (17 mg, 85%) as a yellow solid; Rf = 0.57 (SiO2, pentane/iPrOH 95:5); mp 232.0–233.4 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 12.74 (s, 2H), 9.72 (s, 2H), 7.88 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.94–6.87 (m, 2H), 6.60–6.54 (m, 2H), 3.10–3.0 (m, 2H), 2.57–2.52 (m, 2H), 1.62 (s, 6H), 1.16 (s, 6H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ = 157.9, 144.6, 143.1, 140.2, 135.8, 130.0, 124.6, 122.3, 121.9, 120.4, 119.6, 118.4, 110.8, 110.2, 51.5, 50.1, 28.6, 26.2 ppm; 19F NMR (470 MHz, CDCl3) δ = −57.76 ppm; IR (ATR) ν = 3200 (br. w), 2926 (w), 1601 (s), 1544 (s), 1485 (m), 1404 (m), 1311 (s), 1258 (s), 1170 (s), 1119 (s), 1037 (m) cm–1; HRMS (ESI) m/z 641.2343 ([M + H]+, calcd for C34H31F6N4O2+: 641.2345).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the European Research Council (Starting Grant 802830 to S.J.W.) and the Dutch Research Council (NWO-ENW, Vidi Grant VI.Vidi.192.049 to S.J.W.). We thank Dr. Karthick B. Sai Sankar Gupta and Alfons Lefeber for assistance with NMR experiments.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.3c01018.

Synthetic methods and characterization of new compounds, 1H NMR and UV–vis photoisomerization studies, 1H NMR spectroscopic titrations and data fitting, DFT calculations, and anion transport studies (PDF)

Author Present Address

‡ Department of Chemistry and Pharmacy, Friedrich-Alexander Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Nikolaus-Fiebiger-Str. 10, 91058 Erlangen, Germany

Author Present Address

# Macromolecular Engineering Laboratory, ETH Zurich, Sonneggstrasse 3, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland

Author Contributions

† D.V. and J.E.B. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Sessler J. L.; Gale P. A.; Cho W. S.. Anion Receptor Chemistry; Stoddart J. F., Ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]; b Busschaert N.; Caltagirone C.; Van Rossom W.; Gale P. A. Applications of Supramolecular Anion Recognition. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8038–8155. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gunnlaugsson T.; Glynn M.; Tocci G. M.; Kruger P. E.; Pfeffer F. M. Anion recognition and sensing in organic and aqueous media using luminescent and colorimetric sensors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 3094–3117. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Tay H. M.; Beer P. Optical sensing of anions by macrocyclic and interlocked hosts. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 4652–4677. 10.1039/D1OB00601K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer B. A.; Delmau L. H.; Fowler C. J.; Ruas A.; Bostick D. A.; Sessler J. L.; Katayev E.; Pantos G. D.; Llinares J. M.; Hossain Md. A.; Kang S. O.; Bowman-James K. Supramolecular Chemistry of Environmentally Relevant Anions. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 59, 175–204. 10.1016/S0898-8838(06)59005-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Valkenier H.; Davis A. P. Making a Match for Valinomycin: Steroidal Scaffolds in the Design of Electroneutral, Electrogenic Anion Carriers. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2898–2909. 10.1021/ar4000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Davis J. T.; Gale P. A.; Quesada R. Advances in anion transport and supramolecular medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6056–6086. 10.1039/C9CS00662A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Akhtar N.; Biswas O.; Manna D. Biological applications of synthetic anion transporters. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 14137–14153. 10.1039/D0CC05489E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ko S.-K.; Kim S. K.; Share A.; Lynch V. M.; Park J.; Namkung W.; Van Rossom W.; Busschaert N.; Gale P. A.; Sessler J. L.; Shin I. Synthetic ion transporters can induce apoptosis by facilitating chloride anion transport into cells. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 885–892. 10.1038/nchem.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Manuel-Manresa P.; Korrodi-Gregório L.; Hernando E.; Villanueva A.; Martínez-García D.; Rodilla A. M.; Ramos R.; Fardilha M.; Moya J.; Quesada R.; Soto-Cerrato V.; Pérez-Tomás R. Novel Indole-based Tambjamine-Analogues Induce Apoptotic Lung Cancer Cell Death through p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1224–1235. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Park S.-H.; Park S.-H.; Howe E. N. W.; Hyun J. Y.; Chen L.-J.; Hwang I. C.; Vargas-Zuniga G.; Busschaert N.; Gale P. A.; Sessler J. L.; Shin I. Determinants of Ion-Transporter Cancer Cell Death. Chem. 2019, 5, 2079–2098. 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Li H.; Valkenier H.; Thorne A. G.; Dias C. M.; Cooper J. A.; Kieffer M.; Busschaert N.; Gale P. A.; Sheppard D. N.; Davis A. P. Anion carriers as potential treatments for cystic fibrosis: transport in cystic fibrosis cells, and additivity to channel-targeting drugs. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 9663–9672. 10.1039/C9SC04242C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For pH-induced conformational change, see:; a Santacroce P. V.; Davis J. T.; Light M. E.; Gale P. A.; Iglesias-Sánchez J. C.; Prados P.; Quesada R. Conformational Control of Transmembrane Cl– Transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1886–1887. 10.1021/ja068067v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Howe E. N. W.; Busschaert N.; Wu X.; Berry S. N.; Ho J.; Light M. E.; Czech D. D.; Klein H. A.; Kitchen J. A.; Gale P. A. pH-Regulated Nonelectrogenic Anion Transport by Phenylthiosemicarbazones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8301–8308. 10.1021/jacs.6b04656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Shinde S. V.; Talukdar P. A Dimeric Bis(Melamine)-Substituted Bispidine for Efficient Transmembrane H+/Cl– Cotransport. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4238–4242. 10.1002/anie.201700803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For light-responsive carriers, see:; a Choi Y. R.; Kim G. C.; Jeon H.-G.; Park J.; Namkung W.; Jeong K.-S. Azobenzene-Based Chloride Transporters with Light-Controllable Activities. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 15305–15308. 10.1039/C4CC07560A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kerckhoffs A.; Langton M. J. Reversible Photo-Control over Transmembrane Anion Transport Using Visible-Light Responsive Supramolecular Carriers. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6325–6331. 10.1039/D0SC02745F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ahmad M.; Metya S.; Das A.; Talukdar P. A Sandwich Azobenzene–Diamide Dimer for Photoregulated Chloride Transport. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 8703–8708. 10.1002/chem.202000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ahmad M.; Chattopadhayay S.; Mondal D.; Vijayakanth T.; Talukdar P. Stimuli-Responsive Anion Transport through Acylhydrazone-Based Synthetic Anionophores. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 7319–7324. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kerckhoffs A.; Bo Z.; Penty S. E.; Duarte F.; Langton M. J. Red-shifted tetra-ortho-halo-azobenzenes for photo-regulated transmembrane anion transport. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 9058–9067. 10.1039/D1OB01457A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wezenberg S. J.; Chen L. J.; Bos J. E.; Feringa B. L.; Howe E. N. W.; Wu X.; Siegler M. A.; Gale P. A. Photomodulation of Transmembrane Transport and Potential by Stiff-Stilbene Based Bis(Thio) Ureas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 331–338. 10.1021/jacs.1c10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Shinkai S.; Manabe O. Photocontrol of Ion Extraction and Ion Transport by Photofunctional Crown Ethers. Top. Curr. Chem. 1984, 121, 67–104. 10.1007/3-540-12821-2_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lee S.; Flood A. H. Photoresponsive Receptors for Binding and Releasing Anions. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2013, 26, 79–86. 10.1002/poc.2973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Xu J. F.; Chen Y.-Z.; Wu L.-Z.; Tung C.-H.; Yang Q.-Z. Synthesis of a Photoresponsive Cryptand and Its Complexations with Paraquat and 2,7-Diazapyrenium. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 684–687. 10.1021/ol403343s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Qu D.-H.; Wang Q.-C.; Zhang Q.-W.; Ma X.; Tian H. Photoresponsive Host-Guest Functional Systems. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7543–7588. 10.1021/cr5006342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Díaz-Moscoso A.; Ballester P. Light-Responsive Molecular Containers. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 4635–4652. 10.1039/C7CC01568B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wezenberg S. J. Photoswitchable molecular tweezers: isomerization to control substrate binding, and what about vice versa?. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 11045–11058. 10.1039/D2CC04329G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples, see:; a Shimasaki T.; Kato S. I.; Ideta K.; Goto K.; Shinmyozu T. Synthesis and Structural and Photoswitchable Properties of Novel Chiral Host Molecules: Axis Chiral 2,2′-Dihydroxy-1,1′-Binaphthyl-Appended Stiff-Stilbene. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 1073–1087. 10.1021/jo061127v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hua Y.; Flood A. H. Flipping the Switch on Chloride Concentrations with a Light-Active Foldamer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12838–12840. 10.1021/ja105793c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Han M.; Michel R.; He B.; Chen Y.-S.; Stalke D.; John M.; Clever G. H. Light-Triggered Guest Uptake and Release by a Photochromic Coordination Cage. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1319–1323. 10.1002/anie.201207373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wezenberg S. J.; Vlatković M.; Kistemaker J. C. M.; Feringa B. L. Multi-State Regulation of the Dihydrogen Phosphate Binding Affinity to a Light- and Heat-Responsive Bis-Urea Receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16784–16787. 10.1021/ja510700j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Dąbrowa K.; Niedbała P.; Jurczak J. Anion-Tunable Control of Thermal Z→E Isomerisation in Basic Azobenzene Receptors. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 15748–15751. 10.1039/C4CC07798A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Dąbrowa K.; Jurczak J. Tetra-(Meta-Butylcarbamoyl) Azobenzene: A Rationally Designed Photoswitch with Binding Affinity for Oxoanions in a Long-Lived Z-State. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 1378–1381. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Wezenberg S. J.; Feringa B. L. Photocontrol of Anion Binding Affinity to a Bis-Urea Receptor Derived from Stiff-Stilbene. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 324–327. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Kokan Z.; Chmielewski M. J. A Photoswitchable Heteroditopic Ion-Pair Receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16010–16014. 10.1021/jacs.8b08689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Villarón D.; Siegler M. A.; Wezenberg S. J. A photoswitchable strapped calix[4]pyrrole receptor: highly effective chloride binding and release. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 3188–3193. 10.1039/D0SC06686A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gale P. A. Amidopyrroles: from anion receptors to membrane transport agents. Chem. Commun. 2005, 3761–3772. 10.1039/b504596g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kim D. S.; Sessler J. L. Calix[4]Pyrroles: Versatile Molecular Containers with Ion Transport, Recognition, and Molecular Switching Functions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 532–546. 10.1039/C4CS00157E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Vargas-Zúñiga G. I.; Sessler J. L. Pyrrole N-H anion complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 345, 281–296. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale P. A.; Light M. E.; Mcnally B.; Navakhun K.; Sliwinski K. E.; Smith B. D. Co-transport of H+/Cl– by a synthetic prodigiosin mimic. Chem. Commun. 2005, 3773–3775. 10.1039/b503906a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Waldeck D. H. Photoisomerization Dynamics of Stilbene. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 415–436. 10.1021/cr00003a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Villarón D.; Wezenberg S. J. Stiff-Stilbene Photoswitches: From Fundamental Studies to Emergent Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 13192–13202. 10.1002/anie.202001031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lenoir D.; Lemmen P. Reduktive Kupplungsreaktionen von Ketonen aus der Reihe des 1-Indanons, 1-Tetralons und 9-Fluorenons; konformative Effekete in der Reihe der Indanylidenindane und Tetralinylidentetraline. Chem. Ber. 1984, 117, 2300–2313. 10.1002/cber.19841170703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Shimasaki T.; Kato S.; Shinmyozu T. Synthesis, Structural, Spectral, and Photoswitchable Properties of cis- and trans-2,2,2‘,2‘-Tetramethyl-1,1‘-indanylindanes. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 6251–6254. 10.1021/jo0701233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Imato K.; Sasaki A.; Ishii A.; Hino T.; Kaneda N.; Ohira K.; Imae I.; Ooyama Y. Sterically Hindered Stiff-Stilbene Photoswitch Offers Large Motions, 90% Two-Way Photoisomerization, and High Thermal Stability. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 15762–15770. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c01566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwertz G.; Witschel M. C.; Rottmann M.; Leartsakulpanich U.; Chitnumsub P.; Jaruwat A.; Amornwatcharapong W.; Ittarat W.; Schäfer A.; Aponte R.; Trapp N.; Chaiyen P.; Diederich F. Potent inhibitors of plasmodial serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) featuring a spirocyclic scaffold. ChemMedChem. 2018, 13, 931–943. 10.1002/cmdc.201800053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The dimethyl substitution of the five-membered rings in stiff-stilbene very likely avoids undesired photoinduced side reactions with the central double bond, which could be the main reason for fatigue.

- In comparison with nonmethyl-substituted stiff-stilbene, photoconversion towards the (Z)-isomer is higher, but less (E)-isomer is regenerated in the reverse isomerization process, see ref (12b).

- The data were fit using HypNMR:Frassineti C.; Ghelli S.; Gans P.; Sabatini A.; Moruzzi M. S.; Vacca A. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance as a Tool for Determining Protonation Constants of Natural Polyprotic Bases in Solution. Anal. Biochem. 1995, 231, 374–382. 10.1006/abio.1995.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wu X.; Howe E. N. W.; Gale P. A. Supramolecular Transmembrane Anion Transport: New Assays and Insights. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1870–1879. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gilchrist A. M.; Wang P.; Carreira-Barral I.; Alonso-Carrillo D.; Wu X.; Quesada R.; Gale P. A. Supramolecular methods: the 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (HPTS) transport assay. Supramol. Chem. 2021, 33, 325–344. 10.1080/10610278.2021.1999956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saggiomo V.; Otto S.; Marques I.; Félix V.; Torroba T.; Quesada R. The role of lipophilicity in transmembrane anion transport. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 5274–5276. 10.1039/c2cc31825c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. J.; Marques I.; Dias C. M.; Tromans R. A.; Lees N. R.; Félix V.; Valkenier H.; Davis A. P. Tilting and Tumbling in Transmembrane Anion Carriers: Activity Tuning through n-Alkyl Substitution. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 2004–2011. 10.1002/chem.201504057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The increase in the fractional fluorescence intensity (If) during 365 nm irradiation is due to minor excitation of encapsulated HPTS dye.

- Presumably, the difference in irradiation time needed to reach PSS is the result of a lower power of the 340 nm LED (0.85 mW) as compared to the 365 nm LED (4.1 mW) used in this work (see the SI for details). Please note that possible effects of local heating on the transport rate were excluded in an earlier study, see ref (7f).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.