Abstract

Leptospirosis is an important economical disease of livestock globally, especially in Asia, the Caribbean, and the African continent. Its presence has been reported in a wide range of livestock. However, information on leptospirosis in South Africa is scanty. We conducted a cross-sectional study in 11 randomly selected abattoirs to determine the seroprevalence and risk factors for leptospirosis in slaughtered cattle in Gauteng province, South Africa. During abattoir visits to selected abattoirs, blood samples were collected from 199 cattle and demographic data obtained on the slaughtered animals. The microscopic agglutination test (MAT) was performed on all sera using a 26-serotype panel using cutoff titer ≥ 1:100. Animal- and abattoir-level risk factors were investigated for their association with seropositivity for leptospirosis. The seroprevalence of leptospirosis in the cattle sampled was 27.6% (55/199). The predominant serogroups detected in seropositive cattle were Sejroe (sv. Hardjo) (38.2%) and Mini sv. Szwajizak) (14.5%) but low to Canicola (sv. Canicola) (1.8%) and Pomona (sv. Pomona) (1.8%). The differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Of the five variables investigated, only one (abattoirs) had statistically significantly (P < 0.001) differences in the seroprevalence of leptospirosis among abattoirs. The study documented for the first time in South Africa, the occurrence of serogroups Sejroe (Hardjo bovis strain lely 607), Tarassovi, Hebdomadis, and Medanensis in slaughtered cattle. It was concluded that six of the nine serovars (representing seven serogroups) of Leptospira spp. circulating in cattle population in South Africa are not vaccine serogroups. The clinical, diagnostic, and public health importance of the findings cannot be ignored.

Keywords: Seroepidemiology, Leptospirosis, Cattle, MAT, Abattoirs and South Africa

Introduction

Leptospirosis is an important zoonotic disease of public and animal health importance worldwide and is caused by pathogenic spirochete of the genus Leptospira (Haake 2000). Leptospirosis is an environmentally transmitted disease, and a susceptible host is infected when in contact with water or soil contaminated with urine of a reservoir animal. However, infection can also occur after direct exposure to tissues and fluids of infected animals (Faine et al. 1999; Dhewantara et al. 2019). There is a wide range of animals from livestock, companion animals, and wildlife that have been identified as carriers or reservoirs for pathogenic Leptospira spp. and can shed the bacteria in their urine without symptoms (Bharti et al. 2003; Adler and Moctezuma 2010).

Leptospirosis is a life-threatening disease for humans. Recently, it has been reported that there are over 1 million cases of leptospirosis around the globe and the mortality is up to 60,000 deaths per year (Costa et al. 2015; Torgerson et al. 2015). Levett (2001) reported the existence of over 300 serovars of Leptospira spp. categorized into 25 serogroups. It has also been reported that 17 pathogenic Leptospira spp. circulate worldwide with 21 intermediates that cause non-severe clinical manifestation (Vincent et al., 2019). Mortality rates of leptospirosis in animals and humans have reported 40% aborted cases and above in cattle (Spickler and Leedom 2013) and over 60,000 deaths per year in humans (Costa et al. 2015).

Leptospirosis is mostly under-diagnosed given its non-specific flu-like symptoms at early stages of the disease and the lack of good diagnostic methods (Levett 2001). The microscopic agglutination test (MAT) is considered the “gold standard” for serological diagnosis of leptospirosis, especially in epidemiological studies (World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) 2014, 2018). The advantages and disadvantages of the MAT as a diagnostic test are well documented in the literature (Brandáo et al. 1998; Levett 2001; Smythe et al. 2009; World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) 2014, 2018).

Although the major risk of the disease is upon inhabitants of developing countries living in conditions of poverty and/or lack of basic sanitation leptospirosis, being a zoonosis, has been transmitted to abattoir workers (Almasri et al. 2019; Cook et al. 2017; Dreyfus et al. 2015). Abattoirs used for the slaughter of livestock in any country are vital to conduct active and passive surveillance for diseases, particularly zoonoses such as leptospirosis (Ngugi et al. 2019).

In South Africa, the serological evidence of cattle leptospirosis was first reported in the Western Cape province by van der Merwe (1967) using the MAT with a seroprevalence of 2.5%, while Gummow et al. (1999) reported a seroprevalence of 52% with a predominance of serovar Pomona in the Eastern Cape province. Hesterberg et al. (2009) documented a seroprevalence of 19.4% for leptospirosis in cattle in rural communities in KwaZulu-Natal province and found serovar Pomona to be most frequently detected. To date in South Africa, the antigens that have been used in previous studies are Pomona, Tarassovi, Bratislava, Canicola, Hardjo, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Szwajizak, Grippotyphosa, Bulgarica, Hyos, Robinsoni, and Saxkoebing (Gummow et al. 1999; Hesterberg et al. 2009; Van der Merwe 1967).

In the country, current data are unavailable in cattle, which is created primarily due to the lack of active surveillance, the use of only eight serovars in the panel of antigens for the serodiagnosis of leptospirosis, limited technical-know-how on the serological testing, and culture of leptospires. Therefore, the objectives of the study were to use the international panel of 26 serovars with MAT to determine the seroprevalence of leptospirosis in cattle slaughtered at abattoirs in Gauteng province, to compare the seropositivity for leptospirosis using both 8- and 26-serovar serovar panels, to determine the types and titres of serogroups of Leptospira spp. circulating in livestock and finally, to investigate the risk factors associated with infection by Leptospira spp. in cattle at the abattoirs.

Materials and methods

Policy on prevention and surveillance for leptospirosis in South Africa

It has been documented that leptospirosis is endemic in animal and human populations in South Africa (Botes and Garifallou 1967). Leptospirosis is not a reportable disease in the country and vaccination and testing for the disease is voluntary. The commercially available vaccines to prevent the disease contain five serovars, namely, Canicola, Grippotyphosa, Hardjo, Icterohaemorrhagiae, and Pomona. The diagnosis of leptospirosis in the country is centralized at the leptospirosis reference laboratories based at the Agricultural Research CouncilOnderstepoort Veterinary Research (ARC-OVR) in Pretoria, South Africa. The MAT is the standard test used to confirm the diagnosis of leptospirosis using an 8-serovar panel consisting the five vaccine serovars mentioned above plus serovars Bratislava, Tarassovi, and Szwajizak. Sera for testing for leptospirosis are normally submitted by individual livestock owners, private and government veterinarians.

Study area

The cross-sectional study was conducted in Gauteng province of South Africa. Gauteng province is the smallest province in South Africa and has the highest number of abattoirs in the country, consisting of both high throughput (HT) and low throughput (LT) abattoirs which slaughter animals originating from all the nine provinces of the country.

Sample size determination

To estimate the sample size for the current study, with a 95% confidence interval, the following formula (Thrusfield 2007) was used: n=[1.962 Pexp (1−Pexp)]\d2, where n=required sample size, Pexp=estimated prevalence of leptospirosis and d=desired absolute precision. This is because there is a dearth of current data on livestock leptospirosis in the country. For the study, Pexp was estimated at 50% and d was 7.0%. The estimated minimum sample size for the study was therefore 196 animals.

Selection of abattoirs

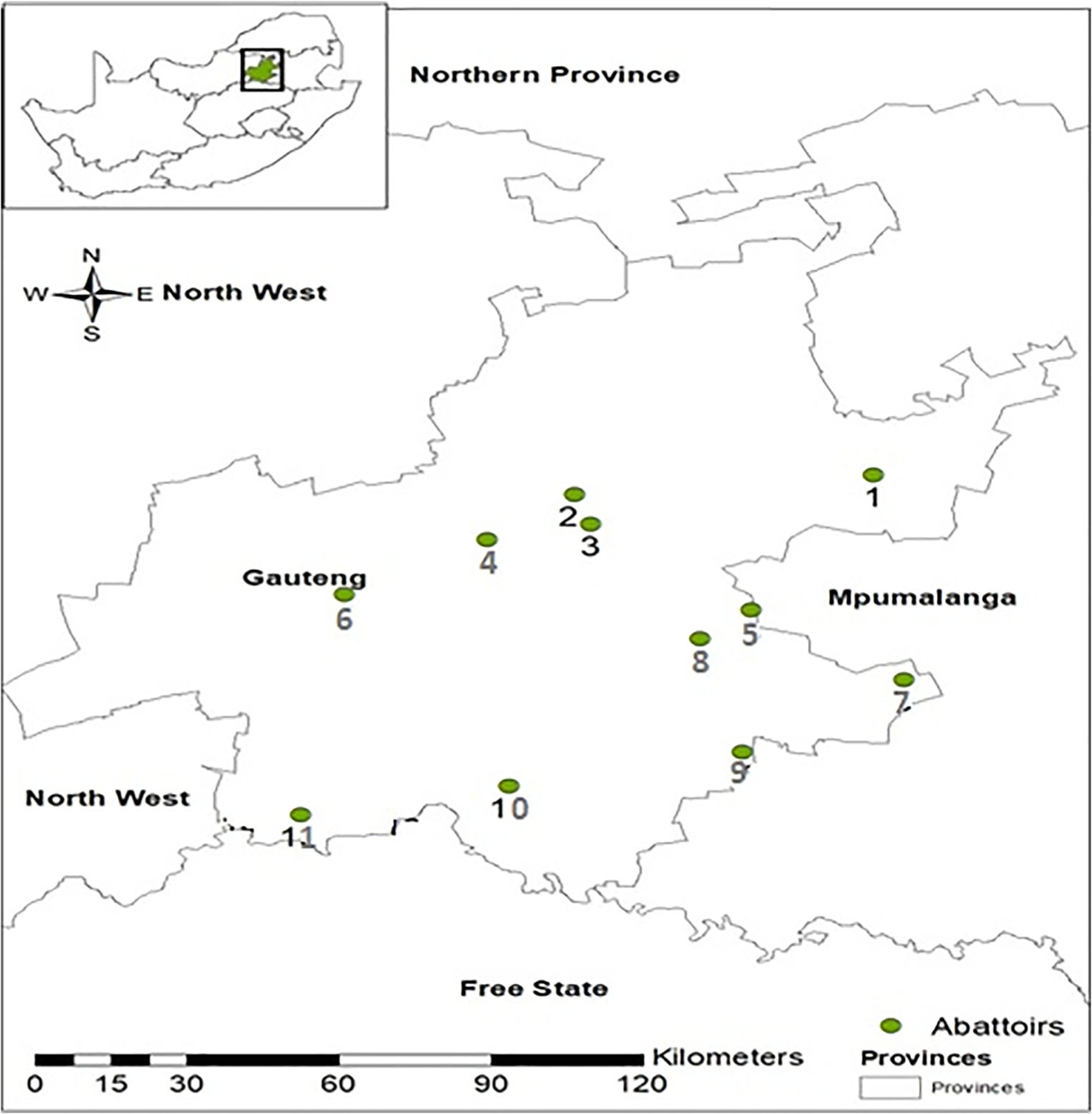

The list of red meat abattoirs including their names, throughput, location, and operational status (active or non-active) was obtained from Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (GDARD). From the list, 11 abattoirs were randomly selected from a total 35 abattoirs for the study from where samples were collected between September 2016 and April 2017 (Fig. 1). The selected abattoirs were visited once during the study period and cattle being slaughtered on the day of the visits were sampled. During each abattoir visit for sampling, the geographic information system (GIS) data (geo coordinates) were collected using the nuvi® GPS navigator, (Garmin, 2689 LMT., USA). The readings were entered into the Arc GIS program, version 13.0 and the data used to produce the map.

Fig. 1.

Map showing the locations of the 11 abattoirs in Gauteng province from where slaughter cattle were sampled

Collection and processing of samples

At slaughter, whole blood was collected aseptically from the selected animals into 10 mL yellow capped tubes, containing serum separator, and the tubes were identified by the ID number on the tag of each animal. Overall, a total of 199 blood samples were collected from slaughtered cattle. Sera harvested from the clotted blood through centrifugation were stored at − 20 °C for further analysis.

Collection of demographic data

The cattle arriving at the abattoirs for slaughter originated from farms throughout South Africa based on the information obtained from the abattoir managers. The abattoir-related information included the location in Gauteng province, throughput (HT and LT), and number of animal species slaughtered (multi-species and mono-species). The animal-related information collected comprised the age (young and adult), sex (male and female), and breed. Information was unavailable on the leptospirosis vaccination status of each animal and the herd history of occurrence of leptospirosis, thereby making trace back investigation of animals to the farm origin impossible in the current study. It is pertinent to mention that the MAT is unable to differentiate between titers of vaccinated versus infected animals (OIE 2014).

Detection of antibodies to Leptospira spp. using the MAT

The MAT was initially performed at the Leptospirosis Reference Laboratory at the ARC-OVR laboratory using as antigen the eight serovars as described on the standard protocols for MAT in South Africa. The same samples were also tested at the Yale University School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology and Microbial Diseases, New Haven, CT, USA using a 26 serovar panel (Table 1).

Table 1.

The 26 Reference antigens of Leptospira spp. used forMAT in this study

| S/no. | Serovar | Serogroup |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Djasiman | Djasiman |

| 2 | Szwajizaka | Mini |

| 3 | Hebdomadis | Hebdomadis |

| 4 | Topaz | Tarassovi |

| 5 | Arborea | Ballum |

| 6 | Javanica | Javanica |

| 7 | Medanensis | Medanensis |

| 8 | Hardjo-Lely 607 | Sejroe |

| 9 | Panama | Panama |

| 10 | Icterohaemorrhagiaea,b | Icterohaemorrhagiae |

| 11 | Hardjo-Prajitnoa,b | Sejroe |

| 12 | Tarassovia | Tarassovi |

| 13 | Bataviae | Bataviae |

| 14 | Pomonaa,b | Pomona |

| 15 | Celledoni | Celledoni |

| 16 | Canicolaa,b | Canicola |

| 17 | Cynopteri | Cynopteri |

| 18 | Grippotyphosaa,b | Grippotyphosa |

| 19 | Ballum | Ballum |

| 20 | Shermani | Shermani |

| 21 | Bratislavab | Australis |

| 22 | Robinsoni | Pyrogenes |

| 23 | Kremastos | Hebdomadis |

| 24 | Bulgarica | Autumnalis |

| 25 | Zanoni | Pyrogenes |

| 26 | Australis | Australis |

Serovars used for routine diagnosis in the OVR Central Laboratory, South Africa

Serovars contained in the vaccine sold in South Africa for livestock

To perform the MAT at the ARC-OVR, the sera were diluted at 1:50 (OIE 2018), using Sorensen’s media for the first screening for antibodies against Leptospira spp. using live culture antigens (approximately 2 × 108 leptospires per mL) of eight reference antigens of Leptospira serovars. To standardize the antigens prior to use in the MAT, the strains were sub-cultured in 10 mL of Ellinghausen, McCullough, Johnson and Harris medium (EMJH) (OIE 2018) in sterile transparent screw-cap tubes and incubated at 29 °C and were checked weekly for the bacterial growth density of 1–2 × 108 Leptospira per mL after 5–7 days of inoculation. The serovars (antigens) used in this phase of the study were Bratislava, Canicola, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Tarassovi, Pomona, Swazajak, Hardjoprajitno, and Grippotyphosa and were obtained from the Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands. All samples that were seropositive at the screening dilution of 1:50 were thereafter subjected to a two-fold dilution titration (1:100 to 1:3200) to determine the final titer. The endpoint observed under the Dark Field Microscope (Leitz Wetzlar®, Model number 963225, Germany) was the dilution of serum samples that showed 50% agglutination, leaving 50% free leptospires compared with the control culture diluted at 1:2 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). At the Yale University, the MAT was also used to determine the antibodies to Leptospira spp. in the serum samples, but we used an extended panel of 26 representative serovars of Leptospira spp. as antigen (Table 1). The MAT was performed as previously described (OIE 2018).

Any sample that was positive at a titer ≥ 1:100 to any of the serovars by one or both laboratories was classified as positive for leptospirosis (OIE 2014, 2018). The results were described as the presumptive infective serogroup based on the serovar with the highest titer for each animal. In case there was multiple serovars belonging to multiple serogroups that had the highest titer, the animal was considered positive with unknown presumptive serogroup.

Statistical analyses

Univariate analysis of associations was conducted considering the serological status of the cattle as a binary outcome (positive or negative). The predictor variables for cattle were abattoirs (n = 11), throughput of abattoir (LT, HT), sex (male, female), age (adult, young), and breed (n = 5). Each predictor variable was tested for significant associations with the serological status using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test of association. The proportions of positive animals for various levels of the variables were also calculated.

Statistical analysis was carried out using R Console version 3.2.1 (R Core Team 2017) at 5% level of significance. Microsoft Excel software was used to plot bar charts of frequency of seropositivity of the variables generated from the univariate analyses.

Results

Seropositivity of sera of cattle using 8- and 26- serotypes panels for MAT

Overall, a total of 27.6% (55/199) of the cattle were seropositive for leptospirosis using the 26-antigen MAT panel. Of a total of 199 cattle tested, only 19 (9.5%) were seropositive using the 8-serovar MAT panel while the 26-serovar panel classified 55 (27.6%) as seropositive. The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.01). All the 19 cattle determined to be seropositive for leptospirosis by the 8-antigen panel were also classified as seropositive using the 26-antigen which includedthe same antigens in both panels, i.e., 100% agreement. Therefore, the use of 8-serovar panel alone resulted in 18.1% (36/155) of the samples being classified as false-negative results.

Analysis for leptospirosis seroprevalence in cattle

The data analyzed were based on the results obtained from the 26-serovar panel MAT. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and univariate associations between variables and seropositivity for antibodies to Leptospira spp. in cattle at abattoirs. The abattoir-level seroprevalence of leptospirosis was 90.9% (10/11). For the five variables investigated for cattlelevel seroprevalence, statistically significantly difference was detected in only one, the abattoirs. The cattle-level seroprevalence ranged from 0.0% (0/10) in Abattoir 10 to 75.0% (6/8) in abattoir 1, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001). The differences in the seroprevalence of leptospirosis were not statistically different by the throughput (HT versus LT) of abattoirs, breed, sex, and age of cattle.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and univariate associations between potential animal-level risk factors and infection with Leptospira species as determined by MAT in cattle abattoirs in Gauteng province in South Africa

| Variable | Category | No. of positive/total tested (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abattoir | 1 | 6/8 (75) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1/25 (4.0) | ||

| 3 | 9/20 (45.0) | ||

| 4 | 1/4 (25.0) | ||

| 5 | 2/30 (6.7) | ||

| 6 | 20/30 (66.7) | ||

| 7 | 9/30 (30.0) | ||

| 8 | 3/10 (30.0) | ||

| 9 | 1/7 (14.3) | ||

| 10 | 0/10 (0.0) | ||

| 11 | 3/25 (12.0) | ||

| Throughput | HT | 34/115 (29.6) | 0.52 |

| LT | 21/84 (25.0) | ||

| Breed | Nguni | 12/31 (38.7) | 0.29 |

| Brahman | 4/10 (40.0) | ||

| Holstein | 1/6 (16.7) | ||

| Bonsmara | 37/141 (26.2) | ||

| Jersey | 1/11 (9.1) | ||

| Sex | Male | 35/118 (29.7) | 0.52 |

| Female | 20/81 (24.7) | ||

| Age | Adult | 53/183 (29.0) | 0.24 |

| Young | 2/16 (12.5) |

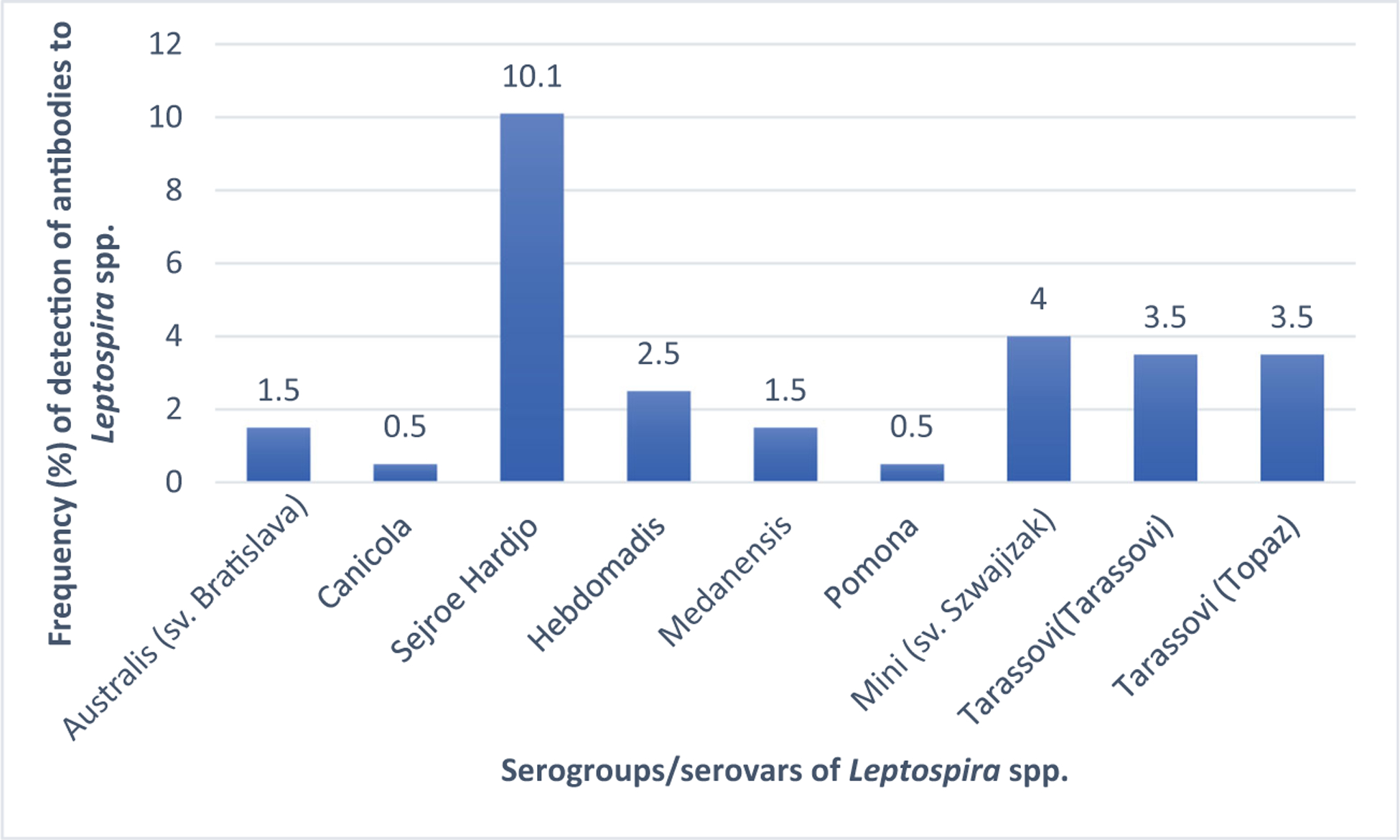

Frequency distribution of antibodies to serogroups of Leptospira spp. in cattle

The seroprevalences of leptospirosis in cattle by serogroups was as follows: Sejroe (sv. Hardjo), 10.1% (20/199), Mini (sv. Szwajizak), 4.0% (8/199), Tarassovi (sv. Tarassovi), 3.5% (7/199), and (sv. Topaz), 3.5% (7/199), but low to Pomona (sv. Pomona), 0.5% (1/199), and Canicola (sv. Canicola), 0.5% (1/199) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Frequency distribution of serogroups/serovars of Leptospira spp. detected in cattle. i) Bratislava = Australis (sv. Bratislava); ii) Medensis = Medanensis; and iii) Szwajizak = Mini (Szwajizak)

Seropositivity to vaccine antigens (serovars) of Leptospira spp.

The 26 serogroups tested by MAT included the five serovars (Grippotyphosa, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Canicola, Hardjo, and Pomona) in the commercial vaccines used to prevent leptospirosis in the country. Antibodies were detected to only three (Canicola, Hardjo, and Pomona) of the five serovars (Table 1). The frequency of detection of antibodies to the three vaccine serovars was 40.0% (22/55) comparedto 60.0% (33/55) found for the six non-vaccine serovars. The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.01).

Distribution of titers of antibodies to serogroups of Leptospira in cattle

For the seven serogroups detected, the antibody titers (ranged from 100 to 3200 in seropositive cattle and the frequencies were statistically significantly different (P < 0.05) (Table 3). The predominant titers (100 and 200) in the 55 seropositive cattle were detected at a frequency of 49.1% (27/55) and 27.3% (15/55), respectively (P = 0.02). The serogroups with the highest titers (3200) was detected at a frequency of 3.6% (2/55) comprising 1.8% (1/55) for Tarassovi (sv. Tarassovi) and 1.8% (1/55) for Sejroe (sv. Hardjo).

Table 3.

Titers of antibodies to serogroups (serovars) of Leptospira spp. in cattle

| Animals type | Titer | Serogroups (serovar) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australis (sv. Bratislava) | Canicola (sv. Canicola) | Sejroe (sv. Hardjoa) | Hebdomadis (sv. Kremastos) | Medanensis (sv. Medanensis) | Pomona (sv. Pomon) | Mini (sv. Szwajizak) | Tarassovi (sv. Tarassovia) | Tarassovi (sv. Topaz) | |||

| Cattle | 100 | 100 (3/3) | 100 (1/1) | 40.0 (8/20) | 80.0 (4/5) | 33.3 (1/3) | 100 (1/1) | 37.5 (3/8) | 14.3 (1/7) | 71.4 (5/7) | 49.1 (27/55) (P < 0.05) |

| 200 | 0.0 (0/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 35.0 (7/20) | 0.0 (0/5) | 33.3 (1/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 37.5 (3/8) | 28.6 (2/7) | 28.6 (2/7) | 27.3 (15/55) (P < 0.05) | |

| 400 | 0.0 (0/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 0.0 (0/20) | 20.0 (1/5) | 0.0 (0/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 0.0 (0/8) | 14.3 (1/7) | 0.0 (0/7) | 3.6 (2/55) (P < 0.05) | |

| 800 | 0.0 (0/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 20.0 (4/20) | 0.0 (0/5) | 33.3 (1/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 0.0 (0/8) | 14.3 (1/7) | 0.0 (0/7) | 10.9 (6/55) (P < 0.05) | |

| 1600 | 0.0 (0/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 0.0 (0/20) | 0.0 (0/5) | 0.0 (0/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 25.0 (2/8) | 14.3 (1/7) | 0.0 (0/7) | 5.5 (3/55) (P < 0.05) | |

| 3200 | 0.0 (0/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 5.0 (1/20) | 0.0 (0/5) | 0.0 (0/3) | 0.0 (0/1) | 0.0 (0/8) | 14.3 (1/7) | 0.0 (0/7) | 3.6 (2/55) (P < 0.05) | |

| P value | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | ||

| Total no. | 3 | 1 | 20 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 55 | |

Highest titer in cattle (3200), 3.6% (2/55) with, 14.3% (1/7) for Tarassovi (sv. Tarassovi)

Discussion

In the current cross-sectional study conducted in abattoirs throughout Gauteng province, the seroprevalence for leptospirosis in cattle was 27.6%. Comparable seroprevalences of 21.5% and 22.3% have been reported by others (Suepaul et al. 2011; André-fontaine 2016), while considerably lower seroprevalences of leptospirosis (3.5% to 10%) have been reported in abattoir studies by others (Leon et al. 2008; Ngbede et al. 2012). Higher seroprevalences of 40.0% leptospirosis in slaughter cattle at abattoirs have been documented in Egypt (Horton et al. 2014) and in St. Kitts, 79.8% (Shiokawa et al. 2019), using MAT. It is however pertinent to mention that in comparing seroprevalence data obtained from livestock, factors such as the type (serogroups and serovars), spectrum (number) of serovars and the diagnostic titers used in the MAT, inability of the MAT to different between antibody titers generated in vaccinated and naturally infected animals (OIE 2014), technical proficiency of the personnel preforming the tests, the vaccination history of the animals tested, among others, should be taken into consideration (Picardeau 2013; Smythe et al. 2009; World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) 2014). The findings in this study have a national significance because the cattle slaughtered in abattoirs located in Gauteng province originated from several provinces across South Africa. Plausibly, the data may be representative of the seroprevalence of leptospirosis (27.6%) in cattle in the country, with resultant negative economic impact on livestock production and zoonotic risk to abattoir workers.

In our study, the seroprevalence of leptospirosis differed significantly across the 11 abattoirs in Gauteng province. The situation in South Africa may be explained, in part, by the differences in the seroprevalence of leptospirosis in cattle from different types of farms (feedlot and communal) in the Gauteng province and the country at large. It also depends on factors such as farm exposure to reservoirs of leptospirosis, particularly rodents, environmental contamination, management systems, and level of sanitation (Vinetz 2001).

The infecting serogroups of Leptospira spp. in livestock have both epidemiological and diagnostic significance. This is because if the number and type of serotypes included in the panel used for the MAT are inadequate, the findings may lead to under-reporting of leptospirosis in the country. In this study, the use of 8-serotypes panel for the MAT on the 199 samples revealed a statistically significantly lower seroprevalence of 9.5% compared to the 27.6% detected with the 26-serotypes panel. The diagnostic implication is that the use of an 8-serotypes MAT panel only would have resulted wrongly classifying 18.18.5% of the samples as negative for leptospirosis. In addition to increasing the number of serotypes in the MAT panel, it has been suggested that the sensitivity of the MAT may be increased by the use of serotypes of Leptospira spp. isolated from the geographical area, for example the country, where the sera were being tested (Pinto et al. 2015) and the use of lower cutoff titers for classifying MAT results, for example, ≥ 1:40 or ≥ 1:48 (Dreyfus et al. 2018; Ngugi et al. 2019), instead of the recommended titer of 1:100 (World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) 2018).

Overall, with the 26-serovar panel, antibodies to Leptospira spp. were detected to 9 (34.6%) and the predominant serogroup in the 55 seropositive cattle was Sejroe (sv. Hardjo), with a seropositivity of 36.4% (20/55) and an overall seroprevalence of 10.1% (20/199). Data on the serological surveys for cattle leptospirosis in the country are limited, with the first report originating from the Western Cape (Van der Merwe 1967), using the MAT where a seroprevalence of 2.5% (108/4305) was detected. The serogroups observed in that study were Australis, Autumnalis, Bovis, Canicola, Grippotyphosa, Hyos, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Pyogenes, and Saxkoebing. These findings date back to the mid-1960s which might indicate a change in the distribution of the circulating serovars currently in the country. It has been documented that sejroe (sv. Hardjo) was the most frequently detected serovar in slaughter cattle and cattle sampled from farms by others in Mexico (Vado-solís et al. 2002), Southern Uganda (Atherstone et al. 2014), and Tanzania (Schoonman and Swai 2013). The widespread predominance of antibodies to serogroup sejroe (sv. Hardjo) is based on reports that cattle are a reservoir for the serovar and that the serovar causes leptospirosis in cattle (Balamurugan et al. 2018; Bharti et al. 2003). However, other serogroups of Leptospira spp. have been documented to be predominant in other countries as indicated by Shiokawa et al. (2019) who reported that the highest seroprevalence was observed to serogroup Mankarso in cattle slaughtered in abattoirs in St. Kitts. Suepaul et al. (2011) also reported the predominance of serogroup Icterohaemorrhagiae in cattle sampled from farms in Trinidad, and serogroup Shermani and Ranarum in cattle in Thailand (Chadsuthi et al. 2017).

Of potential clinical relevance is the fact that the titers of antibodies detected in the seropositive cattle were also high to the predominant Sejroe (sv. Hardjo), with 34% of the samples seropositive for the serogroups having titers of 800 and over. These titers are considered significant for current or acute disease (Adesiyun et al. 2006; Gummow et al. 1999). Similarly, high titers of antibodies were detected to other serogroups tested in our study. The limitation of this cross-sectional study can however not be ignored since although all the slaughter animals were apparently healthy, the recovery of animals from recent exposure to Leptospira spp. which could have led to increased titers, could not be ascertained in this study. Furthermore, the limitation of the MAT used in the current study which is unable to differentiate between antibody titers produced following vaccination and natural exposure (OIE 2014), should however be considered in discussing the importance of the titers of antibodies to sejroe (sv. Harjo) detected in our study.

The other serogroups to which antibodies were detected in cattle in the current study, Australis, Canicola, Hebdomadis, Medanensis, Pomona, Mini, and Tarassovi, have also been documented in cattle by others (Adesiyun et al. 2006; Dreyfus et al. 2018; Gummow et al. 1999; Schoonman and Swai 2010; Suepaul et al. 2011; Vallée et al. 2018). The seroprevalence of antibodies to serogroups of Leptospira spp., within and across countries and regions, may be affected by the policy on vaccination and the types of serovars of Leptospira in the vaccines, the serotypes used in the MAT panel, infecting serovars in animal reservoirs and environmental contamination. Unfortunately, in our study the vaccination history of the animals sampled was unavailable and vaccination for livestock against leptospirosis is voluntary in the country. It is important to note that of the five vaccine serovars which are also included in the panel of 26 serotypes used for MAT, antibodies were detected to only three (Canicola, Hardjo and Pomona) in our cross-sectional study. Additionally, antibodies were detected to 6 non-vaccine serovars (Topaz, Hebdomadis, Medanensis, Bratislava, Szwajizak, Tarassovi). It is noteworthy that for the 55 cattle seropositive for leptospirosis (titers of 100 or higher), 33 (60.0%) had antibodies to the six non-vaccine serovars at a significantly higher frequency compared to the 22 (40.0%) which exhibited antibodies to the three vaccine serovars. It is therefore indicative that the seropositivity detected in our study was primarily be due the natural exposure of the cattle to Leptospira spp. Additionally, considering the absence of history of voluntary vaccination of cattle against leptospirosis, it cannot be assumed that the cattle positive for antibodies against the three vaccine serovars were due to vaccine exposure rather than natural exposure to the pathogen. Although the potential interference of vaccination with surveillance has been reported, there are documentations that it is minimal (Balakrishnan and Roy 2014; Júnior et al. 2007; Martins et al. 2018). It is also important to consider the fact that MAT does not differentiate between the titers produced by vaccinated and naturally infected animals (OIE 2014).

Of the variables and risk studied, the throughput of abattoirs, sex and breed of animals did not have a significant effect on the seroprevalence of leptospirosis in the cattle studied. Ngbede et al. (2012) reported a similar finding regarding the sex and breed of cattle slaughtered at an abattoir in Nigeria where no significant association with the seropositivity for leptospirosis in the slaughtered animals was detected. Similarly, Suepaul et al. (2010) reported that sex of cattle was not significantly associated with the occurrence of leptospirosis in cattle in Trinidad.

The age of cattle tested in our study was not significantly associated with seropositivity for leptospirosis, a finding at variance with the report of Ngbede et al. (2012) who reported that the age of slaughtered cattle was statistically significantly (P = 0.0313) associated with the seropositivity for leptospirosis as follows, < 2 years (0.0%), 2–5 years (1.82%), and > 5 years (12.5%). The authors attributed the differences to increased exposure to the pathogen over time. The difference between both studies could be due, in part, to the fact that in South Africa most of the cattle slaughtered originated from feedlots where animals are slaughtered at approximately 1–2 years of age, while most of those slaughtered in Nigeria are primarily from extensively and semi-intensively managed farms and are considerably older, > 2-year-old cattle constituted 94.4% of the 142 cattle tested. Suepaul et al. (2011) in a farm-based study in Trinidad had also reported that age of cattle had a significant effect on seropositivity for leptospirosis.

Conclusions and recommendations

It is concluded that serogroups Sejroe, Mini, and Tarassovi are circulating in cattle in Gauteng province and therefore may be of clinical importance. The finding of a high frequency of detection of serogroups of Leptospira that are neither in the vaccines nor in the MAT antigen panel used in the country may have both clinical and diagnostic implications. The potential public health significance of serological evidence of leptospirosis in slaughtered cattle to abattoir workers as well as the economic impact on livestock farmers through animal morbidity and mortality cannot be ignored.

It is recommended that the spectrum and types of serotypes in the panel used to diagnose livestock leptospirosis with the MAT in the country be increased from the current 8-antigen panel to reduce the under-reporting of leptospirosis in the country. Secondly, the vaccines used to prevent leptospirosis in South Africa should be re-considered to, in addition, contain the predominant serovars (particularly Bratislava, Topaz, Tarassovi, and Szwajizak) detected to be currently circulating in livestock in the country. Finally, it will be prudent to conduct a national abattoir-based study on leptospirosis in the country.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Institute of Health, USA, the Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (GDARD), South Africa, for the provision of funds to enable us to conduct this research study. We thank the University of Pretoria, Yale University School of Public Health, National Veterinary Research Institute, and Onderstepoort Veterinary Research (OVR) for their support. The cooperation of the abattoir owners for the access to their facilities is well appreciated by the authors.

Funding

This study was funded by the NIH grant R01 AI121207 and the Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (GDARD), South Africa, for the provision of funds to enable us to conduct this research study. Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (GDARD), South Africa (Grant Reference Number:2015/16).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval Animal ethical clearances were approved and received from the Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) through the Section 20 approval (number: FY2015/2016), the University of Pretoria Animal Ethics Committee (AEC: v084–16) of the Faculty of Veterinary Science, and from the ARC-Onderstepoort Veterinary Research (ARC-OVR) (ARC-OVR: AEC 12–16) for this research.

Informed consent Managers or owners of the abattoirs from where pigs were sampled for the study consented.

References

- Adesiyun AA, Mootoo N, Halsall S, Bennett R, Clarke NR, Whittington CU, Seepersadsingh N, 2006. Sero-epidemiology of canine Leptospirosis in Trinidad: Serovars, Implications for Vaccination and Public Health. Journal of Veterinary Medicine 53, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler B, and de la Moctezuma P, 2010. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Veterinary Microbiology, 140, 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasri M, Ahmed QA, Turkestani A, Memish ZA, 2019. Hajj abattoirs in Makkah: risk of zoonotic infections among occupational workers. Veterinary Medicine and Science 5, 428–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André-Fontaine G, 2016. Leptospirosis in domestic animals in France: Serological results from 1988 to 2007. Revue Scientifique et Technique de l’OIE 35, 913–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherstone C, Picozzi K, Kalema-Zikusoka G, 2014. Short report: Seroprevalence of Leptospira hardjo in cattle and African buffalos in southwestern Uganda. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 90, 288–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan G, Roy P, 2014. Comparision of efficacy of two experimental bovine leptospira vaccines under laboratory and field. Veterinary Immunology Immunopathology.15, 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan V, Alamuri A, Bharathkumar K, Patil SS,Govindarai GN, Nagalingam M, Krishnamoorthy P, Rahman H, Shome BR, 2018. Prevalence of Leptospira serogroup-specific antibodies in cattle associated with reproductive problems in endemic states of India. Tropical Animal Health Production 50, 1131–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, Matthias MA, Diaz MM, Lovett MA, Vinetz JM, Levett PN, Gilman RH, Williq MR, 2003. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 3, 757–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botes W, Garifallou A, 1967. Leptospirosis: a brief review, general considerations and incidence in South Africa. Journal of South African Veterinary Medicine Association 38, 67–75 [Google Scholar]

- Brandáo AP, Camargo ED, Da Silva ED, Silva MV, Abráo RV, 1998. Macroscopic agglutination test for rapid diagnosis of human leptospirosis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 36, 3138–3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadsuthi S, Bicout DJ, Wiratsudakul A, Suwancharoen D, Petkanchanapong W, Modchang C, Triampo W, Ratanakorn P, Chalvet-monfray K, 2017. Investigation on predominant Leptospira serovars and its distribution in humans and livestock in Thailand. PLoS Neglected Tropical Disease. 9, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EA, de Glanville WA, Thomas LF, Kariuki S, Bronsvoort BM, Fèvre EM, 2017. Risk factors for leptospirosis seropositivity in slaughterhouse workers in western Kenya. Occupational Environmental Medicine 74, 357–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa F, Hagan JE, Calcagno J, Kane M, Torgerson P, Martinez-Silveira MS, Stein C, Abela-Rider B, Ko AI 2015. Global Morbidity and Mortality of Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 9, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhewantara PW, Lau CL, Allan KJ, Hu W, Zhang W, Mamun AA, & Soares RJ, 2019. Spatial epidemiological approaches to inform leptospirosis surveillance and control : A systematic review and critical appraisal of methods. 85, 185–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus A, Heuer C, Wilson P, Collins-Emerson J, Baker MG, Benschop J, 2015. Risk of infection and associated influenza-like disease among abattoir workers due to two Leptospira species. Epidemiology and Infection 143, 2095–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus A, Wilson P, Benschop J, Collins-Emerson J, Verdugo CHC, 2018. Seroprevalence and herd-level risk factors for seroprevalence of Leptospira spp. in sheep, beef cattle and deer in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 66, 302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faine S, Adler B, Bolin C, Perolat P, 1999. Leptospira and Leptospirosis, 2nd edition. Melbourne: Medical Science. [Google Scholar]

- Gummow B, Myburgh JG, Thompson PN, Lugt JJ Van Der J, Spencer BT, 1999. Three case studies involving Leptospira interrogans serovar pomona infection in mixed farming units. Journal of South African Veterinary Association 70, 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake DA, 2000. Spirochetal Lipoproteins and Pthogenesis. Microbiology 182, 5700–57005. [Google Scholar]

- Hesterberg UW, Bagnali R, Bosch B, Perrett K, Homer R, Gummow B 2009. Journal of South African Veterinary Association 80, 45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton KC,Wasfy M,, HamedSamaha H, Abdel-Rahman B, Safwat S, Abdel Fadeel M, Mohareb E, Dueger E, 2014. Serosurvey for Zoonotic Viral and Bacterial Pathogens Among Slaughtered Livestock in Egypt. Vector Borne Zoonotic Disease 14, 633–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Júnior GN, Genovez ME, Ribeiro MG, Castro V, Jorge AM, . 2007. Interference of vaccinal antibodies on serological diagnosis of leptospirosis in vaccinated buffalo using two types of commercial vaccines. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 38, 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Leon LL, Garcia RC, Diaz CO, Valdez RB, Carmona GCA, Velazquez BLG, 2008. Prevalence of Leptospirosis in Dairy Cattle from Small Rural Production Units in Toluca Valley, State of Mexico. Animal Biodiversity and Emerging Diseases 1149, 292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levett PN, 2001. Leptospirosis Leptospirosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 14, 296–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins G, Oliveira CS & Lilenbaum W (2018). Dynamics of humoral response in naturally-infected cattle after vaccination. against leptospirosis. Acta Tropica 187:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngbede EO, Raji MA, Kwanashie CN, Okolocha EC, Gugong VT, Hambolu SE, 2012. Serological prevalence of leptospirosis in cattle slaughtered in the Zango abattoir in Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria, Veterinaria Italiana 48, 179–184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngugi JN, Fèvre EM, Mgode GF, Obonyo M, Mhamphi GG, Otieno CA, Cook EAJ, 2019. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of leptospirosis in slaughter pigs; a neglected public health risk, western Kenya. BMC Veterinary Research. 15, 403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OIE (World Organization for Animal Health)., 2014. Leptospirosis. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals - Web Format, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- OIE (World Organization for Animal Health)., 2018. Leptospirosis. Terrestial Manual, 503–516. [Google Scholar]

- Picardeau M, 2013. Diagnosis and epidemiology of leptospirosis. Medecine et Maladies Infectieuses, 43, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto PS, Loureiro AP, Penna B, Lilenbaum W, 2015. Usage of Leptospira spp. local strains as antigens increases the sensitivity of the serodiagnosis of bovine leptospirosis. Acta Tropica 149, 163–167.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Schoonman L, and Swai ES, 2010. Herd-andanimal-level risks factors for bovine leptospirosis in Tanga region of Tanzania. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 42, 1565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoonman L, Swai., 2013. Risk factors associated with the seroprevalence of leptospirosis, amongst at-risk groups in and around Tanga city, Tanzania. Journal Annals of Tropical Medicine Parasitology 103, 711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiokawa K, Welcome S, Kenig M, Lim B, Rajeev S. (2019). Epidemiology of Leptospira infection in livestock species in Saint Kitts. Tropical Animal Health Production 15, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe LD, Wuthiekanun V, Chierakul W, Suputtamongkol Y, Tiengrim S, Dohnt MF, Symonds ML, Slack AT, Apiwattanaporn A, Chueasuwanchai S, Day NP, Peacock SJ 2009. Short Report : The Microscopic AgglutinationTest ( MAT ) is an unreliable predictor of infecting Leptospira serovar in Thailand, American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 81, 695–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spickler AR, Leedom LKR 2013. Leptospirosis. The Center for Food Security and Public Health. http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/leptospirosis.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Suepaul S, Carrington C, Campbell M, Borde G, Adesiyun AA, 2010. Serovars of Leptospira isolated from dogs and rodents. Epidemiology and Infection 138, 1059–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suepaul SM, Carrington CV, Campbell M, Borde G, Adesiyun AA., 2011. Seroepidemiology of leptospirosis in livestock in Trinidad. Tropical Animal Health Production,.43, 367–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrusfield MV, 2007. Veterinary Epidemiology. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 3rd edition. Blackwell Science Ltd, a Blackwell Publishing Company UK. [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson PR, Hagan JE, Costa F,Calcagno J,Kane M, Martinez-Silveira MS, Goris MG, Stein C, Ko AI, Abela-Ridder B 2015. Global burden of leptospirosis: estimated in terms of disability adjusted life years. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 9, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vado-solís I, Cárdenas-marrufo MF, Jiménez-delgadillo B, Alzina-lópez A, Laviada-molina H, 2002. Clinical-epidemiological study of leptospirosis in humans and reservoirs in Yucatán, México, 44, 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallée E, Heuer C, Collins-Emerson JM, Benschop J, Ridler AL, Wilson PR, 2018. Effects of natural infection by L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo type Hardjo-bovis and L. interrogans serovar Pomona, and leptospiral vaccination, on sheep growth. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 1, 196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Merwe GF, 1967. Leptospirosis in cattle, sheep and pigs in the Republic of South Africa. Bulletin de l Office International Des Epizooties, 68, 63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A., Schiettekatte O, Goarant C, Neela VK, Bernet E, Thibeaux R, Ismail N, Mohd Khalid MKN,Amran F, Toshiyuki Masuzawa T,Nakao R, Korba AA, Bourhy P, Frederic J Veyrier FJ, Picardeau MI (2019). Revisiting the taxonomy and evolution of pathogenicity of the genus Leptospira through the prism of genomics. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 13,5: e0007270. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinetz JM, 2001. Leptospirosis. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 14, 527–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]