Abstract

Cell cycle G2 arrest, nuclear localization, and cell death induced by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr were examined in fission yeast by using a panel of Vpr mutations that have been studied previously in human cells. The effects of the mutations on Vpr functions were highly similar between fission yeast and human cells. Consistent with mammalian cell studies, induction of cell cycle G2 arrest by Vpr was found to be independent of nuclear localization. In addition, G2 arrest was also shown to be independent of cell killing, which only occurred when the mutant Vpr localized to the nucleus. The C-terminal end of Vpr is crucial for G2 arrest, the N-terminal α-helix is important for nuclear localization, and a large part of the Vpr protein is responsible for cell killing. It is evident that the overall structure of Vpr is essential for these cellular effects, as N- and C-terminal deletions affected all three cellular functions. Furthermore, two single point mutations (H33R and H71R), both of which reside at the end of each α-helix, disrupted all three Vpr functions, indicating that these two mutations may have strong effects on the overall Vpr structure. The similarity of the mutant effects on Vpr function in fission yeast and human cells suggests that fission yeast can be used as a model system to evaluate these Vpr functions in naturally occurring viral isolates.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protein R (Vpr) is a 15-kDa virion-associated protein which is conserved among HIV-1, HIV-2, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), and other lentiviruses (35, 45), suggesting an important role of Vpr in the viral life cycle. Studies of SIV of macaques (SIVmac) with defective vpr also indicate the importance of Vpr. Some of the rhesus monkeys infected with vpr-defective SIVmac either do not progress to AIDS or show a slower progression of the disease (11, 16, 22). When vpr and vpx, a second gene homologous to vpr in SIVmac, are both defective, infected rhesus monkeys have a low titer of virus and do not progress to AIDS (11, 45). In chimpanzees and one human subject infected with an HIV-1 strain containing a mutant, nonfunctional Vpr protein, the Vpr protein reverted to the wild-type sequence during the course of the infection, indicating that there is strong selection for Vpr during HIV-1 infection (12).

When assayed in cell culture systems, Vpr shows multiple activities. Vpr activates viral replication (25, 26) and induces changes of cell morphology that mimic cell differentiation (24). It prevents cell proliferation by arresting transfected human cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle (14, 19, 38, 39), where the replication of HIV is increased (12, 48). The expression of HIV Vpr in transfected human cells ultimately causes cell death through apoptosis (1, 43) and/or cytopathic effects (48). These effects of Vpr are highly conserved among eukaryotes, since Vpr also causes G2 arrest, changes of cell morphology, and cell death in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) cells (50, 51, 55). Vpr also promotes transport of the preintegration viral complex into the nucleus and thus helps HIV-1 to infect nondividing cells (4, 15, 46). When Vpr is expressed alone in mammalian cells, it is localized to the nucleus and often found predominately at the nuclear membrane. In this report, we show that Vpr is localized to the nucleus of S. pombe cells, just as it is in mammalian cells with the same predominate localization at the nuclear membrane (46).

The processes affected by Vpr, cell cycle, nuclear localization, and cell death, are highly conserved among eukaryotes, and studies with yeast cells have been instrumental in the molecular dissection of these processes (reviewed in reference 53). With regard to the cell cycle, the Cdc2 cyclin-dependent kinase, which determines the onset of mitosis in all eukaryotic cells, is functionally interchangeable between the fission yeast and human Cdc2 proteins (23). An illustration of the conservation of the Vpr-induced G2 arrest is that Vpr induces G2 arrest in both fission yeast and human cells by inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdc2 (8, 14, 19, 38, 50, 54). Similarly, nuclear localization is highly conserved between mammalian and budding yeast cells with human nuclear transport factors functional in budding yeast (9, 46). The classical pathway for nuclear localization initiates with binding of the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) to importin α, also known as karyopherin α. The NLS-importin α complex interacts with importin β, and this complex then binds to nuclear porins, components of the nuclear pore, for translocation into the nucleus (13). Vpr does not itself contain an NLS, but it has recently been shown that Vpr binds to importin α from either budding yeast or human cells to stabilize the binding of an NLS to a different site on importin α (37, 46). More recently, it has been suggested that some aspects of apoptosis are conserved between mammalian and fission yeast cells. Four proteins (Bak, Bax, Ced4, and Vpr) which induce apoptosis in mammalian cells or nematodes also induce death in fission yeast cells with changes in nuclear morphology characteristic of apoptosis (17, 18, 20, 55). Given the high degree of conservation for the G2-mitosis transition of the cell cycle, nuclear localization, and cell death, Vpr almost certainly exerts these three effects by interacting with highly conserved components of the cellular machinery. Fission yeast is then likely to be an excellent model system in which to study these functions of Vpr.

In this study, we examined in fission yeast the effect of a collection of vpr mutations which have previously been characterized for their effects on G2 arrest in human cells (2, 42). One goal of this study was to determine if the mutations have the same effect on G2 arrest in fission yeast as they do in human cells. If there is a strong correlation between the effects of the Vpr mutations in yeast and human cells, this finding would support using yeast in certain functional studies of Vpr. A second goal of this study was to determine if the vpr mutations have differential effects on the multiple activities of vpr which, in yeast, include G2 arrest, cell killing, and nuclear localization. Finding a mutation with a large effect on one function of vpr with little or no effect on another would suggest that Vpr uses different pathways for these two effects. The availability of these mutations would then help in analyzing the different pathways utilized by vpr for these multiple functions.

One ultimate goal of this study is to contribute to the development of the yeast system as a means to address the role of multiple Vpr activities during HIV infection and pathogenesis. The existence of multiple Vpr activities in cell culture assays and numerous sequence variants of Vpr in patients raises the question of whether all of these activities are of equal importance to the virus. It may be that under certain conditions, one or more of the activities is not required for a normal viral life cycle and that most of the Vpr quasispecies under these conditions do not have that activity. One approach to defining the role of multiple Vpr activities in human infections is to develop a structure-function map of Vpr to allow prediction of function from the DNA sequence. Although a number of studies have focused on defining the functional domains of Vpr (7, 30–32, 49), the large extent of Vpr sequence variation (quasispecies) in infected patients makes this characterization tedious and almost impossible. It is unlikely that a sufficiently detailed structure-function map of Vpr will be available any time soon to allow full and accurate predictions of Vpr activities from sequence data alone. The comparative ease of determining Vpr activities in yeast suggests the alternative approach of cloning Vpr variants from patients into yeast cells to determine the activities of each Vpr variant. The study reported here supports the feasibility of this approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and media.

S. pombe SP223 (h− ade-216 leu1-32 ura4-294) was used as the host in this study. All of the methods used here for cell cultures, induction of vpr gene expression under the control of the nmt1 promoter, and cell plating have been described previously (51, 54, 55).

Cloning of the vpr gene into S. pombe expression vectors pYZ1N and pYZ3N-GFP.

The pYZ1N and pYZ3N-GFP vectors have already been described (52). Briefly, these two vectors are derivatives of the pREP1N vector we used to express vpr in previous studies (51, 55). They all contain the same nmt1-inducible promoter and were designed to allow positive selection of gene insertions (both vectors) and fusion to the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-encoding gene (pYZ3N-GFP) for in vivo analysis of gene expression. Expression of vpr in the pYZ1N plasmid gives the same phenotypic changes as reported previously for expression in the pREP1N vector (51, 52, 55). Thirteen independent vpr point mutations, which were derivatives of wild-type vprLAI and initially studied for their effects in human cells (42), were used in this study. Four deletion mutants, also derivatives of wild-type vprLAI, have been described previously (2). These vpr genes were amplified by PCR as described previously (51) using PCR primers VPRNde (GAGGCATATGGAACAAGCCCCAGAAGACC) and VPRBamWT (GGCGGATCCCTAGGATCTACTG). The digested PCR product was inserted at the NdeI and BamHI sites of the pYZ1N vector. The vpr genes were fused in frame with GFP by PCR amplification using the SacI (ACAGACCGCGGATATGGAAAAGCCCCAGAAGACC) and VPRBam primers and inserting the digested PCR product into the SacII and BamHI sites of pYZ3N-GFP. The ligation mixtures were transformed into Escherichia coli, and colonies containing plasmids with vpr inserts were identified as colorless colonies on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal)-containing Luria-Bertani agar plates (6). The insertions were initially identified by restriction enzyme digestion and PCR. The presence of the correct mutation in each clone was confirmed by complete nucleotide sequencing of the insert using an ABI 377 DNA Sequencer (The Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.). All of the vpr-containing plasmids were expressed in the SP223 fission yeast strain to examine G2 arrest, nuclear localization, and cell death.

Measurement of cell cycle G2 arrest.

The flow cytometry procedure used to measure cell cycle G2 arrest was performed essentially as described previously (51), with some minor modifications. Briefly, in order to quantify the extent of G2 arrest induced by HIV-1 Vpr, cells were taken from an active, log-phase, thiamine-containing culture (in the range of 1 × 107 to 5 × 107 cells per ml), washed three times with distilled water, and used to start a thiamine-free culture at a density of 2 × 105 cells per ml at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm). Cells were collected 40 h after the culture was started, and the DNA content of the cells was determined by FACScan using Cell-fit software (Becton Dickinson). The extent of Vpr-induced G2 arrest was expressed as the percentage of G1 cells in the vpr-repressing cells that shifted to the G2 phase of the cell cycle in vpr-expressing cells. All of the data presented here are averages (with standard deviations) of three independent experiments and are expressed as a ratio of the G2 arrest of mutant vpr to that of wild-type vpr. Ratios of greater than one indicate increased induction of G2 arrest, and ratios of less than one indicate reduced G2 arrest compared to wild-type Vpr.

Measurement of cell survival.

Colony-forming ability was used as a quantitative measurement of Vpr-induced cell death as previously described (55). Briefly, S. pombe cells containing the pYZ1N::vpr constructs were prepared as described above for measurement of G2 arrest. An aliquot of each vpr-expressing or vpr-repressing culture was collected 18 h after vpr gene induction and plated onto thiamine-containing selection (EMM) plates. Numbers of CFU were calculated from the number of colonies that grew on the plates as a percentage of the number of cells originally plated, corrected by the plating efficiency of vpr-repressed cells. The plating efficiency of vpr-repressed cells was determined for 18-h thiamine-containing cultures by plating on thiamine-containing EMM selection plates and ranged from 100 to 40%.

Nuclear localization.

Cultures of cells with plasmids expressing GFP or the GFP-Vpr fusion were prepared as described above for measurement of G2 arrest. Cellular localization was determined 18 to 24 h after vpr gene induction by fluorescence microscopy on an Olympus BH2-RFL microscope using the blue filter combination with the EY-455 supplemental exciter filter.

Secondary-structure analyses of Vpr.

The secondary structures of Vpr were analyzed by nnpredict software, which predicts a secondary-structure tendency for each residue in an amino acid sequence based on a two-layer feedforward neural network (21). These structural predictions are generally consistent with the tertiary model proposed recently for Vpr based on circular-dichroism and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data (28, 40). The diagram of Vpr’s tertiary structure was generated by using the RasMol v. 2.6 program (41) on the coordinates provided by Ziwei Huang (28).

RESULTS

Vpr proteins from viral variants NL4-3 and LAI have similar effects on G2 arrest and cell killing.

Wild-type VprLAI, which is the parent of all of the mutant Vpr proteins used in this study, differs at four amino acids (Y15H, S28N, N41G, and R85Q) from VprNL4-3, which was used in previous fission yeast studies. Figure 1 shows that VprLAI and VprNL4-3 have similar effects on fission yeast with respect to G2 arrest and cell killing. Vpr-induced cell cycle G2 arrest was measured by flow cytometry and determination of the septation index. Flow cytometry analysis measures the percentage of G1 cells when vpr is repressed that shift to the G2 phase in vpr-expressing cells. This quantitative measurement of Vpr-induced G2 arrest showed that 74.4% ± 7.8% of the VprLAI G1 cell population shifted to G2 (Fig. 1A), compared to 71.5% ± 14.8% of the VprNL4-3 cell population (data not shown; 51). Thus, both Vpr variants induced similarly high levels of G2 arrest in fission yeast. The septation index assay was also used to compare the abilities of the two Vpr variants to inhibit cell division. This assay measures the percentage of cells in a population that contains septa, an indication of mitotic cell division (51). Both vpr-repressing cultures maintained a normal septation index (11.0% ± 0.5% and 11.5% ± 0.6% for VprNL4-3 and VprLAI, respectively), indicating normal and actively growing cells, but only 5.2% ± 1.0% and 3.5% ± 0.5% of septa were observed in the vpr-expressing cultures 18 h after vpr induction.

FIG. 1.

Effects of VprLAI on G2 arrest, cell survival, and nuclear localization in fission yeast. (A) Flow cytometric analyses 40 h after transfer to medium with (vpr repressed) or without (vpr expressed) thiamine, showing the shift of G1 cells in the medium with thiamine (+T) to the G2 stage of the cell cycle in medium without thiamine (−T). (B) Qualitative assay for cell killing by Vpr. The plate with thiamine at the top represses the nmt1 promoter, and cells form normal-size colonies after incubation for 3 to 4 days. Cells with the VprNL4-3 plasmid (a) are on the left side, and cells with the VprLAI plasmid (b) are on the right. On the plate without thiamine shown at the bottom, the vpr gene is induced, and both VprNL4-3 and VprLAI prevent the formation of normal-size colonies. (C) The morphological changes induced by VprLAI differ somewhat from those induced by VprNL4-3. The cultures with thiamine for both VprNL4-3 (a) and VprLAI (b) show the normal Calcofluor staining pattern, with weak overall staining of the cell wall and intense staining of the septum forming at the site of eventual cell division. One cell in each panel shows this strong staining of the septum. The cultures without thiamine at the bottom (vpr expressed) both show large increases in chitin staining compared to normal cells. However, for VprNL4-3 (a), this increased chitin deposition occurs at the protruding ends of the cells while cells with VprLAI have very thick chitin deposits near the center of the cell, where the septum normally forms. (D) The GFP-VprNL4-3 fusion protein localizes around the rim of the nucleus and shows little overlap with nuclear DNA. A cell 17 h after induction of Vpr was stained for DNA with the vital stain Hoechst 33342 (Chikashige, 1994 no. 8). The third panel, in color, shows GFP-Vpr in the false color of red and DNA staining in the false color of green with little overlap between the two colors.

Expression of VprNL4-3 in fission yeast induces extensive cell death (50, 51, 55). Two methods are used to measure the cell death induced by Vpr. A qualitative method is to streak vpr-containing cells directly from a thiamine-containing plate (to repress vpr expression) onto a thiamine-free plate (to induce vpr expression). In this assay, no visible colonies or very small colonies form with cells containing either VprNL4-3 or VprLAI (Fig. 1Ba) (51). The second method is quantitative and measures the colony-forming ability of vpr-expressing cells on thiamine-containing agar plates (to stop vpr expression). For VprLAI, 16.8% ± 3.6% of the cells form colonies on agar plates after 18 h of induction in thiamine-free liquid medium, which is identical to the 16.7% ± 1.3% observed for VprNL4-3 (Table 1) (55). Thus, both variants of Vpr efficiently kill fission yeast cells.

TABLE 1.

Summary of effects of mutations on Vpr-induced G2 arrest, nuclear localization, and cell killing

| Vpr genotype | Effect on G2 arrest (avg mt:wt ratio ± SD)a

|

Nuclear localization | Colony-forming ability (avg % survival ± SD) | Structural domainsb | Vpr function(s) affectedc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fission yeast cells | Human cellsd | |||||

| Wild types | ||||||

| VprNL4-3 | + (1.04 ± 0.08) | + | + | + (16.7 ± 1.3) | − | − |

| VprLAI | + (1.00 ± 0.06) | + | + | + (16.8 ± 3.6) | − | − |

| Point mutations | ||||||

| E17D | + (1.00 ± 0.04) | + | + | + (5.6 ± 0.2) | α1 | None |

| W18R | + (0.93 ± 0.13) | ND | ND | ↓ (86.9 ± 3.5) | α1 | D |

| E24G | + (1.02 ± 0.19) | + | + | ↓ (43.1 ± 16.7) | α1 | D |

| E25K | + (1.10 ± 0.06) | + | ± | − (110.4 ± 6.0) | α1 | D, N |

| H33R | ↓ (0.84 ± 0.23) | − | ± | ↓ (37.1 ± 3.0) | α1 | D, N, G2 |

| F34I | + (1.04 ± 0.01) | ↓ | ± | ↓ (87.5 ± 6.7) | α1 | D, N |

| W54R | + (1.04 ± 0.09) | ↓ | + | ↓ (44.2 ± 14.1) | α2 | D |

| H71R | ↓ (0.62 ± 0.32) | − | ± | ↓ (41.7 ± 4.1) | α2 | D, N, G2 |

| H78R | ↓ (0.38 ± 0.21) | ↓ | + | + (9.5 ± 7.1) | C tail | G2 |

| S79A | + (1.10 ± 0.30) | + | + | + (9.5 ± 1.0) | C tail | None |

| R88K | ↓ (0.31 ± 0.21) | ↓ | + | + (9.5 ± 2.7) | C tail | G2 |

| A89T | + (0.91 ± 0.08) | + | + | + (8.8 ± 1.7) | C tail | None |

| R90K | + (1.11 ± 0.12) | ↓e | + | ↑ (1.8 ± 1.3) | C tail | D, G2 |

| Deletions | ||||||

| N15 | ↓ (0.62 ± 0.03) | ND | ± | − (94.3 ± 21.3) | N tail | D, N, G2 |

| N27 | − (0.18 ± 0.09) | ND | ± | − (100.1 ± 6.0) | N tail, α1 | D, N, G2 |

| C63 | − (−0.21 ± 0.30) | ND | − | − (117.6 ± 13.7) | α2, C tail | D, N, G2 |

| C77 | ↓ (0.89 ± 0.08) | ND | ± | ↓ (20.9 ± 4.3) | C tail | D, N, G2 |

ND, not determined; wt, wild type; mt, mutant; +, wild-type level; ↓, reduced effect. −, no effect.

Location of the mutation in the structural domains of Vpr. N tail, amino acids 1 to 16; α1, α-helix from amino acid 17 to amino acid 34; α2, α-helix from amino acid 52 to amino acid 71; C tail, amino acids 72 to 96.

D, cell death; N, nuclear localization; G2, G2 arrest.

Data from Selig et al. (42).

M. Emerman, personal communication.

Vpr proteins from viral variants NL4-3 and LAI induce cell morphological changes with subtle differences.

Vpr induces morphological changes including gross enlargement and irregular shapes in mammalian cells (24). Gross enlargement and irregular protruding structures were also observed when VprNL4-3 was expressed in fission yeast (51). These yeast cells are generally two to three times larger than normal cells. Moreover, the protruding structures induced on the cells by Vpr correlate with sites of increased chitin biosynthesis in the cell wall. Multiple septa were found in some of the irregularly shaped cells (55) (Fig. 1Ca). Gross enlargement of cells and increased chitin biosynthesis were also found when VprLAI was expressed in yeast. Interestingly, however, neither the irregular protruding structures nor localized accumulation of chitin in the cell wall was found in the vprLAI-expressing cells. Instead, the chitin accumulation was found predominantly in the septal area (Fig. 1Cb).

GFP-Vpr fusion protein localizes to the nuclear rim.

To determine the cellular localization of Vpr in fission yeast, the vpr gene was fused to the GFP-encoding reporter gene and expressed from the nmt1 promoter in fission yeast cells. As a control, the GFP-encoding gene alone was expressed from the nmt1 promoter. In thiamine-containing medium, cells with either GFP or the GFP-Vpr fusion had no green fluorescence (data not shown). When the nmt1 promoter was induced with thiamine-free medium, cells with the gfp gene alone had green fluorescence dispersed throughout the cells with obvious fluorescence in both the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments (Fig. 2Ba). The cells with GFP alone remained normal, with no morphological changes, G2 arrest, or cell death. In contrast, cells with the GFP-Vpr fusion had intense green fluorescence around the nucleus at the nuclear rim with little labelling of the cytoplasm (Fig. 1D and 2Bb). The GFP-Vpr fusion protein retains Vpr functions, since it induces morphological changes, G2 arrest, and cell death (data not shown). As the fusion protein is functional, the localization of the GFP-Vpr fusion protein most likely represents the cellular localization of Vpr. In a two-color representation with GFP in the arbitrary color of green and DNA in the arbitrary color of white (Fig. 1Da), the combination of the two colors in the third panel shows that there is little overlap of GFP and DNA, indicating that GFP-Vpr localizes predominately at the nuclear rim, with little of the fusion actually present in the nucleus.

Vpr point mutations affect G2 arrest similarly in yeast and human cells.

The panel of mutant Vpr proteins used in this fission yeast study come from studies of Vpr interactions with uracil DNA glycosylase (2, 42). These mutant proteins include four deletions, two from the amino terminus (N15 and N27) and two from the carboxy terminus (C63 and C77), and 13 single point mutations representing single amino acid substitutions distributed throughout the gene. The mutant vpr genes were cloned into expression vector pYZ1N. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that all of the vpr mutations were expressed in fission yeast. A 15-kDa band corresponding to the size of Vpr was detected with anti-Vpr serum for all 13 point mutations (Fig. 2A). The point mutations expressed at least as much protein as wild-type VprLAI, and the W18R, E25K, H33R, F34I, H71R, and H78R point mutant proteins had expression levels higher than that of the wild type. Thus, any reduction in activity caused by a vpr point mutation is not due to reduced protein expression. As the deletion mutant proteins may not react with the antiserum raised against a synthetic peptide representing part of Vpr (4), expression of the four deletions was measured by Northern blot analyses and shown to be similar to that of VprLAI by hybridization of an RNA blot with a vpr probe (Fig. 2Ab). Also, when expressed as fusions to GFP, all four Vpr deletion mutant proteins gave readily detectable green fluorescence, indicating that the fusion proteins were expressed at similar levels.

FIG. 2.

Effects of Vpr mutations on nuclear localization and G2 arrest. (A) Expression of mutant Vpr proteins. Extracts from induced (without thiamine) point mutant Vpr proteins (a) and mRNA from deletion mutant proteins (b) were isolated and subjected to Western and Northern blotting analyses, respectively. The arrow indicates the 15-kb band expected for Vpr. +T, with thiamine; −T, without thiamine; WT, wild type. (B) Mutations which affect localization of the GFP-Vpr fusion protein. (a) Localization of GFP not fused to Vpr showing uniform distribution throughout the cell. (b) Localization of GFP-VprLAI showing a ring or a ring of dots around the nucleus with little detectable labelling of the cytoplasm. Panels c to j show the results of those Vpr mutations which change the localization pattern: c, E25K; d, H33R; e, F34I; f, H71R; g, N15 deletion; h, N27 deletion; i, C63 deletion; j, C77 deletion. (C) Effects of Vpr mutations on G2 arrest. Representative flow cytometry analyses of the cell cycle are shown for four mutations. The upper panels are for cultures with thiamine, where vpr is repressed, and the bottom panels are for cultures without thiamine, where vpr is expressed.

The mutations indicate that the carboxy terminus of Vpr is required for induction of G2 arrest in fission yeast but that other regions of the protein also play a role in G2 arrest. While the two short deletions N15 and C77 reduce the extent of G2 arrest, the longer deletions N27 and C63 eliminate G2 arrest. For the point mutations, three of six mutations in the carboxy terminus (H71R, H78R, and R88K) reduce G2 arrest. The H33R mutation is the only point mutation in the amino-terminal half of Vpr to affect G2 arrest (Table 1; Fig. 2C).

Vpr-induced cell death is independent of G2 arrest.

More than half of the mutations in this study caused significant reductions in the amount of cell death induced by Vpr (Table 1). Three of the four deletions eliminated cell death, while the C77 deletion reduced cell death (20.9% ± 4.3%). Seven of the 13 point mutations reduced cell death to various degrees. The mutations reducing cell killing are not located in a small region of the protein, indicating that much of the Vpr protein is required for cell killing.

Five point mutations that reduced cell killing (W18R, E24G, E25K, F34I, and W54R) did not affect the ability to induce G2 arrest (Table 1). In contrast, two other mutations, H78R and R88K, showed the opposite effect, with decreased G2 arrest but unchanged levels of cell killing. Discordance between the G2 arrest and cell killing effects of these seven mutations suggests that these are the independent functions of Vpr.

Nuclear localization is not required for G2 arrest.

All four deletions and four of the point mutations (E25K, H33R, F34I, and H71R) affect the localization of the GFP-Vpr fusion to the nuclear rim (Fig. 2Bc to j). With GFP-VprLAI, the green labelling was restricted mostly to the rim of the nucleus, with most cells having no detectable labelling in the cytoplasm or the nucleus itself (Fig. 1D and 2Bb). In contrast, the four deletions and four point mutations had various levels of labelling in the cytoplasm, along with other differences from the labelling pattern of the GFP-VprLAI fusion protein. The N15 and C77 deletions and the H33R, F34I, and H71R point mutations caused labelling of the nuclear rim weaker than that obtained with GFP-VprLAI, while the N27 and C63 deletions and the E25K point mutation caused little or no preferential labelling of the nuclear rim. General labelling of the nucleus at various levels was seen for the N27 and C77 deletions and the four point mutations affecting nuclear localization. The N15 deletion and, to a lesser extent, the C77 deletion frequently caused a strong dot of labelling on the nuclear rim. The C63 deletion is the only mutation that nearly eliminated any specific labelling and resulted in labelling that was almost randomly distributed in the cell.

The E25K and F34I mutations indicate that nuclear localization is not required for G2 arrest, since these mutations produced levels of G2 arrest comparable to that of wild-type VprLAI, even though localization to the nuclear rim was reduced or eliminated. The E25K mutation also produced normal levels of G2 arrest in human cells (42). In contrast, other point mutations (H78R and R88K) that produced typical nuclear localization reduced the ability to induce G2 arrest in yeast, which is also consistent with the idea that nuclear localization and G2 arrest are independent functions of Vpr.

Nuclear localization may be required for cell killing.

The four point mutations (E25K, H33R, F34I, and H71R) and the four deletion mutations reducing or eliminating nuclear localization all significantly reduced cell killing, suggesting that nuclear localization is required for cell killing (Table 1). Analysis of more mutations for their effects on cell killing and nuclear localization is necessary to confirm this. However, if nuclear localization is required for cell killing, this series of mutations clearly establishes that nuclear localization is not sufficient for cell killing, since point mutations E24G and W54R produced the typical localization to the nuclear rim, but these two mutations significantly reduced cell-killing ability (43.1% ± 16.7% and 44.2% ± 14.1% compared to the 16.7% ± 3.6% of VprLAI).

Structural requirements for Vpr functions.

A tertiary structure of Vpr recently proposed on the basis of NMR and circular-dichroism data consists of helix-loop-helix domains and amino and carboxy tails (28, 34, 40). The approximate positions of these structural features are amino acids 1 to 16 for the amino tail, 17 to 34 for the first α-helix, 35 to 51 for the loop, 52 to 71 for the second α-helix, and 72 to 96 for the carboxy tail. NMR studies indicate that the second α-helix may extend several more amino acids beyond position 71 (40). The two α-helixes in Vpr which are indicated by circular-dichroism and NMR data are likely to interact with each other through their hydrophobic faces (28, 40, 44, 49). The tertiary structures of the loop and the N and C tails have not yet been reported.

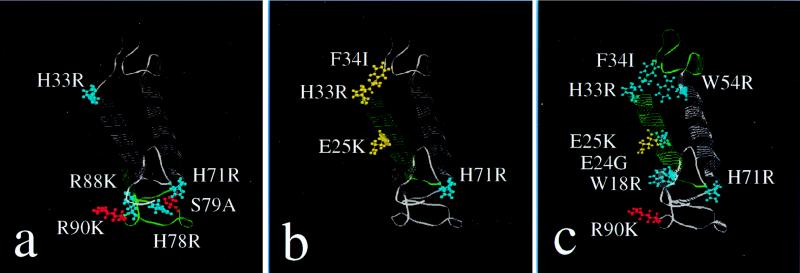

While this three-dimensional structure requires further confirmation, it is used in Fig. 3a to c to illustrate the position of the Vpr point mutations as a basis for identifying possible structural domains of Vpr required for a function. The C tail of Vpr appears to be crucial in the induction of G2 arrest in fission yeast (Table 1). Five of the six Vpr mutations in this region affected G2 arrest; H71R, H78R, and R88K reduced G2 arrest, while S79A and R90K enhanced G2 arrest (Fig. 3a; Table 1). Interestingly, different effects of two adjacent mutations on G2 arrest were observed. Reduced G2 arrest (average mutant: wild-type ratio ± standard deviation, 0.38 ± 0.21) was observed for H78R, while the adjacent S79A mutation resulted in the same or slightly enhanced G2 arrest (1.10 ± 0.30). Similarly, an opposite effect was also seen at amino acids 88 and 90, where R88K reduced G2 arrest (0.31 ± 0.21) and R90K retained the wild-type level or somewhat enhanced G2 arrest (1.11 ± 0.08; Table 1 and Fig. 2A).

FIG. 3.

Positions of amino acid substitutions which affect a Vpr function. The tertiary structure of Vpr is from reference 28. The amino acid is shown in blue when the change reduces an activity, the amino acid is shown in yellow when no activity is observed, and the amino acid is shown in red when wild-type or increased activity is observed. Structural domains implicated as being important for a function are shown in green. (a) Substitutions affecting G2 arrest. (b) Substitutions affecting localization to the nuclear rim. (c) Substitutions affecting cell killing.

The first α-helix in the N-terminal portion of Vpr appears to be crucial for nuclear localization. Three single substitutions (E25K, H33R, and F34I) that reside within or near the N-terminal α-helix reduced or eliminated localization to the nuclear rim (Fig. 2C). The regions of Vpr required for cell killing appear to span most of the protein. Point mutations in or near the first α-helix (W18R, E24G, E25K, H33R, and F34I) reduce cell killing, as do the two mutations in the second α-helix (W54R and H71R). Four of five point mutations in the carboxy tail (H78R, S79A, R88K, and A89T) do not affect cell killing to a significant extent, but the R90K mutation increases cell killing. Notably, two point mutations (H33R and H71R) reduce all three functions, G2 arrest, nuclear localization, and cell killing, and these two mutations are at the carboxy ends of each α-helix (Table 1; Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The high degree of conservation of Vpr functions was first reported for the VprNL4-3 viral variant, which induces cell cycle G2 arrest, cell death, and localization to the nucleus in both mammalian and fission yeast cells (7, 43, 51, 55). This study shows that these effects of VprLAI, which differs at four amino acids from VprNL4-3 and which induces G2 arrest, nuclear localization, and cell death in human cells (44, 48), are essentially the same as those of VprNL4-3 in fission yeast. However, these two variants of Vpr induce morphological changes in fission yeast with subtle differences (Fig. 1C). VprNL4-3 induces unique protruding structures that correlate with an accumulation of chitin (55). While VprLAI also induces increased chitin biosynthesis, it does not induce the protruding structures with the associated accumulation of chitin, but instead, the increased chitin accumulates predominantly in the equatorial region where the multiple new cell walls (septa) are formed. While the mechanism of increased chitin biosynthesis in fission yeast and the analogous function in human cells is unknown, this subtle difference between VprNL4-3 and VprLAI observed in fission yeast raises the question of whether these two variants of Vpr also function somewhat differently in human cells.

The results obtained with the mutations in VprLAI are further evidence for the conservation of Vpr functions, since when the same mutation has been studied in human cells, the mutations almost always have similar effects in human and yeast cells. For G2 arrest, 9 of the 12 mutations show identical effects on G2 arrest in human and yeast cells (Table 1). Two of the mutations (F34I and W54R) show minor differences between fission yeast and human cells with reduced G2 arrest in human cells but no change in yeast cells. This discrepancy could be due to the differences in scoring of the G2 effect. The one exception is the R90K mutation, which produced wild-type or somewhat enhanced G2 arrest in fission yeast (1.11 ± 0.12), opposite to the decreased G2 arrest reported in mammalian cells (42). This opposite effect could be explained by differences in the interaction of R90K mutant Vpr with the homologous yeast and human target proteins with which Vpr interacts to induce G2 arrest; R90K Vpr might have a stronger interaction with the yeast protein but a weaker interaction with the human protein. This possibility can be tested when the initial target protein for the induction of G2 arrest is identified.

Vpr mutations also seem to affect nuclear localization almost identically in human and yeast cells. Four of the mutations found to reduce or eliminate localization of the GFP-Vpr fusion protein to the nuclear rim in fission yeast (E25K, F34I, H71R, and the C77 deletion) also affect nuclear localization in human cells. Vodicka et al. (46) reported that VprLAI localized to the nuclear membrane in human and budding-yeast cells, just as the fusion protein does in fission yeast. They also showed that the F34I and H71R Vpr mutant proteins do not localize to the nuclear membrane in human cells, in good agreement with the results reported here showing that the F34I mutation nearly eliminates localization to the nuclear membrane and H71R significantly reduces it. Yao et al. (49) reported that E25K and the C77 deletion produced large amounts of Vpr protein in the cytoplasm. This close agreement between human and yeast cells with respect to the effects of mutations on G2 arrest and nuclear localization suggests that most of the time results from yeast studies on a Vpr mutation will also apply to human cells.

Another indication that Vpr functions are highly conserved is that the regions of Vpr important for a function appear to be similar in human and fission yeast cells. For G2 arrest in fission yeast, point mutations in the amino-terminal end do not affect G2 arrest, with the exception of the H33R mutation discussed below. However, a number of point mutations at the carboxy terminus of Vpr affect G2 arrest. The strong influence of the carboxy terminus on G2 arrest is illustrated by pairs of nearby amino acids (H78R plus S79A and R88K plus R90K) whose mutation has opposite effects on G2 arrest. The point mutations analyzed in fission yeast then indicate that the carboxy-terminal end is particularly important for G2 arrest. The same conclusion has been reached from studies of Vpr-induced G2 arrest in mammalian cells (7, 30, 42, 48).

The regions of Vpr required for nuclear localization also seem to be similar in human and fission yeast cells. Proline substitutions, which disrupt α-helixes, at five different positions in the N-terminal domain of Vpr impaired nuclear localization in mammalian cells (7, 31). In fission yeast, the two N-terminal deletions and three single substitutions (E25K, H33R, and F34I) within or near the end of the N-terminal α-helix nearly abolished nuclear localization (Fig. 2C). Thus, the structural domain of Vpr required for nuclear localization is the same in human and fission yeast cells.

This study of Vpr mutations shows that a mutation often affects the functions of Vpr differently and suggests that some functions of Vpr are independent. In particular, four mutations (E25K, F34I, H78R, and R88K) have significantly different effects on G2 arrest and nuclear localization. The best example of this point is the E25K mutation that nearly eliminates localization to the nuclear rim without any detectable effect on the levels of G2 arrest. Similar observations in mammalian cells have led to proposals that G2 arrest and nuclear localization are independent functions mediated by two different structural domains of Vpr (10, 30, 46).

These studies in fission yeast also suggest that G2 arrest is not required for cell killing. Comparisons between Vpr-induced cell killing in fission yeast and human cells are limited by the small amount of data available about the effects of Vpr mutations on the killing of human cells. Only one mutation studied here has also been examined in human cells, and in agreement with our observations in fission yeast, the C77 deletion impairs both G2 arrest and cell killing in Jurkat T cells (48). However, contrary to our view that G2 arrest and cell killing are separate functions of Vpr, Yao et al. (48) have suggested that G2 arrest correlates with cell killing. In their studies, two of four single substitutions (I63K and R80A) were shown to decrease both G2 arrest and cell killing. In our study, decreased G2 arrest and cell killing were also caused by two point mutations (H33R and H71R) and all four deletions from either the N or C terminus. However, a discordance between the effect on G2 arrest and cell killing was observed in seven single amino acid substitutions, including four mutations at the N-terminal α-helical region (W18R, E24G, E25K, and F34I), one mutation at the leucine-rich domain (W54R), and two mutations at the C terminus (H78R and R88K). These data strongly support the idea that Vpr uses different pathways to induce G2 arrest and cell death. This idea is further supported by our recent studies (8) showing that Vpr-induced G2 arrest can be suppressed by a nonphosphorylatable Tyr15 mutation of Cdc2. In this mutant yeast strain, Vpr does not induce G2 arrest, but Vpr is still able to kill cells as efficiently as in a wild-type yeast strain. Based on this result and the evidence from analysis of Vpr mutants, we conclude that G2 arrest and cell death are independent functions of Vpr in fission yeast. More mutations, particularly ones such as E25K, which eliminates cell death but produces wild-type levels of G2 arrest in fission yeast, need to be analyzed in human cells to determine if G2 arrest and apoptosis are independent functions of Vpr in human cells.

In contrast to the independence of G2 arrest from nuclear localization and cell killing in fission yeast, the mutant analysis suggests that nuclear localization and cell killing are related. Mutations that impair nuclear localization (E25K, H33R, F34I, and H71R) also attenuate the ability of Vpr to kill cells, suggesting that Vpr needs to localize to the nuclear rim to be effective in the induction of cellular death. However, nuclear localization is not sufficient for cell killing. Mutations (E24G and W54R) that reduce the ability of Vpr to kill cells still cause its localization to the nuclear rim. An alternative explanation of the mutant data obtained with fission yeast is that the functional domains needed for nuclear localization and cell killing simply overlap and that, by happenstance, no mutation included in this study separated nuclear localization and cell killing. This possibility is supported by the point mutations that indicate that the cell-killing domain involves most of the Vpr protein and extends beyond the nuclear localization domain (Fig. 3b and c).

Although the point mutations suggest that the carboxy end of Vpr is important for G2 arrest and that the N-terminal α-helix is important for nuclear localization, the deletions, in contrast, tend to indicate that the overall structure of the Vpr protein is required for the wild-type levels of functions. A particularly interesting observation is that the N-terminal end of Vpr seems to have some role in G2 arrest, since the N15 deletion reduces G2 arrest and the N27 deletion eliminates G2 arrest. This deletion may affect G2 arrest through structural changes in Vpr. The tertiary structures of the amino and carboxy tails of Vpr are not known, but they might be close to each other at the end of the protein, where they are in a position to interact with each other (Fig. 3). If the amino tail serves to hold the carboxy tail in a structure necessary for binding to the protein leading to G2 arrest, then the amino-terminal deletions could affect G2 arrest even if the carboxy portion contains the actual binding site. A structural change may also explain the ability of two point mutations (H33R and H71R) to interrupt all three functions. These two amino acids are present near the end of each proposed α-helix and may represent sites that are crucial to maintaining the overall structure required for Vpr functions. Therefore, these sites might be potential targets in designing anti-Vpr regimens.

These studies of mutant Vpr proteins have major implications for the functions of the Vpr quasispecies present during HIV infection. Ten of the 13 point mutations examined in this study affected one or more of the three Vpr functions (G2 arrest, nuclear localization, and cell killing). Eight of these 10 point mutations had a significant effect on only one or two of these three functions while leaving the other function(s) unchanged. Vpr mutations then often have functional consequences and frequently affect only a subset of functions. Even VprLAI and VprNL4-3 had subtle differences in their induction of morphological changes in fission yeast, indicating that all Vpr variants are not functionally equivalent. These observations raise the question of whether individual Vpr quasispecies all possess identical G2 arrest, nuclear localization, and apoptosis activities. The similar effects of Vpr mutations on these activities in fission yeast and human cells indicate that the yeast system will be useful in evaluating the functional variations of naturally occurring Vpr variants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Emerman and Josephine Sire for their gifts of point and deletion mutant vpr genes, respectively, Ziwei Huang for providing the coordinates to generate the tertiary structure of the Vpr protein, Jun Yang for assistance in DNA sequencing, and Ram Yogev for encouragement. The HIV-1 VprNL4-3 antiserum was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, and contributed by Velpandi Ayyavoo.

This work was supported in part by funding from the Chicago Pediatric Faculty Foundation and National Institutes of Health grant 1R29-AI-40891-091 (Y.Z.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayyavoo V, Mahboubi A, Mahalingam S, Ramalingam R, Kudchodkar S, Williams W V, Green D R, Weiner D B. HIV-1 Vpr suppresses immune activation and apoptosis through regulation of nuclear factor kappa B. Nat Med. 1997;3:1117–1123. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouhamdan M, Benichou S, Rey F, Navarro J-M, Agostini I, Spire B, Camonis J, Slupphaug G, Vigne R, Benarous R, Sire J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr protein binds to the uracil DNA glycosylase DNA repair enzyme. J Virol. 1996;70:697–704. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.697-704.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou P Y, Fasman G D. Empirical predictions of protein conformation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1978;47:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connor R I, Chen B K, Choe S, Landau N R. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology. 1995;206:935–944. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conti L, Rainaldi G, Matarrese P, Varano B, Rivabene R, Columba S, Sato A, Belardelli F, Malorni W, Gessani S. The HIV-1 vpr protein acts as a negative regulator of apoptosis in a human lymphoblastoid T cell line: possible implications for the pathogenesis of AIDS. J Exp Med. 1998;187:403–413. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cronan J J, Narasimhan M, Rawlings M. Insertional restoration of beta-galactosidase alpha-complementation. Gene. 1988;70:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Marzio P, Choe S, Ebright M, Knoblanch R, Landau N R. Mutational analysis of cell cycle arrest, nuclear localization, and virion packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr. J Virol. 1995;69:7909–7916. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7909-7916.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elder, R. T., M. Yu, M. Chen, and Y. Zhao. Tyr15 phosphorylation of Cdc2 is required for cell cycle G2 arrest induced by HIV-1 Vpr and is independent of cell death in fission yeast. Submitted for publication.

- 9.Fabre E, Hurt E. Yeast genetics to dissect the nuclear pore complex and nucleocytoplasmic trafficking. Annu Rev Genet. 1997;31:277–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher T M, 3rd, Brichacek B, Sharova N, Newman M A, Stivahtis G, Sharp P M, Emerman M, Hahn B H, Stevenson M. Nuclear import and cell cycle arrest functions of the HIV-1 Vpr protein are encoded by two separate genes in HIV-2/SIV(SM) EMBO J. 1996;15:6155–6165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbs J S, Lackner A A, Lang S M, Simon M A, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Progression to AIDS in the absence of a gene for vpr or vpx. J Virol. 1995;69:2378–2383. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2378-2383.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh W C, Rogel M E, Kinsey C M, Michael S F, Fultz P N, Nowak M A, Hahn B H, Emerman M. HIV-1 Vpr increases viral expression by manipulation of the cell cycle: a mechanism for selection of Vpr in vivo. Nat Med. 1998;4:65–71. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorlich D, Mattaj I W. Nucleocytoplasmic transport. Science. 1996;271:1513–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He J, Choe S, Walker R, Di Marzio P, Morgan D O, Landau N R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J Virol. 1995;69:6705–6711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6705-6711.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinzinger N, Bukinsky M, Haggerty S, Ragland A, Kewalramani V, Lee M, Gendelman H, Ratner L, Stevenson M, Emerman M. The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 influences nuclear localization of viral nucleic acids in nondividing host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7311–7315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoch J, Lang S M, Weeger M, Stahl-Hennig C, Coulibaly C, Dittmer U, Hunsmann G, Fuchs D, Müller J, Sopper S, Fleckenstein B, Überla K T. vpr deletion mutant of simian immunodeficiency virus induces AIDS in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1995;69:4807–4813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4807-4813.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ink B, Zörnig M, Baum B, Hajibagheri N, James C, Chittenden T, Evan G. Human Bak induces cell death in Schizosaccharomyces pombe with morphological changes similar to those with apoptosis in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2468–2474. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James C, Gschmeissner S, Fraser A, Evan G I. CED-4 induces chromatin condensation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and is inhibited by direct physical association with CED-9. Curr Biol. 1997;7:246–252. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jowett J B, Planelles V, Poon B, Shah N P, Chen M-L, Chen I S Y. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr gene arrests infected T cells in the G2 + M phase of the cell cycle. J Virol. 1995;69:6304–6313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6304-6313.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jurgensmeier J M, Krajewski S, Armstrong R C, Wilson G M, Oltersdorf T, Fritz L C, Reed J C, Ottilie S. Bax- and Bak-induced cell death in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:325–339. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kneller D G, Cohen F E, Langridge R. Improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by an enhanced neural network. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90154-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang S M, Weeger M, Stahl-Hennig C, Coulibaly C, Hunsmann G, Müller J, Müller-Hermelink H, Fuchs D, Wachter H, Daniel M M, Desrosiers R C, Fleckenstein B. Importance of vpr for infection of rhesus monkeys with simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1993;67:902–912. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.902-912.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee M G, Nurse P. Complementation used to clone a human homologue of the fission yeast cell cycle control gene cdc2. Nature. 1987;327:31–35. doi: 10.1038/327031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy D N, Fernandes L S, Williams W V, Weiner D B. Induction of cell differentiation by human immunodeficiency virus 1 vpr. Cell. 1993;72:541–550. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90073-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy D N, Refaeli Y, MacGregor R R, Weiner D B. Serum Vpr regulates productive infection and latency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10873–10877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy D N, Refaeli Y, Weiner D B. Extracellular Vpr protein increases cellular permissiveness to human immunodeficiency virus replication and reactivates virus from latency. J Virol. 1995;69:1243–1252. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1243-1252.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y-L, Spearman P, Ratner L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R localization in infected cells and virions. J Virol. 1993;67:6542–6550. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6542-6550.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo Z, Butcher D J, Murali R, Srinivasan A, Huang Z. Structural studies of synthetic peptide fragments derived from the HIV-1 Vpr protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:732–736. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macreadie I G, Castelli L A, Hewish D R, Kirkpatrick A, Ward A C, Azad A A. A domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr containing repeated H(S/F)RIG amino acid motifs causes cell growth arrest and structural defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2770–2774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahalingam S, Ayyavoo V, Patel M, Kieber-Emmons T, Weiner D B. Nuclear import, virion incorporation, and cell cycle arrest/differentiation are mediated by distinct functional domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr. J Virol. 1997;71:6339–6347. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6339-6347.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahalingam S, Collman R G, Patel M, Monken C E, Srinivasan A. Functional analysis of HIV-1 Vpr: identification of determinants essential for subcellular localization. Virology. 1995;212:331–339. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahalingam S, Khan S A, Murali R, Jabbar M A, Monken C E, Collman R G, Srinivasan A. Mutagenesis of the putative alpha-helical domain of the Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: effect on stability and virion incorporation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3794–3798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nie Z, Bergeron D, Subbramanian R A, Yao X-J, Checroune F, Rougeau N, Cohen E A. The putative alpha helix 2 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr contains a determinant which is responsible for the nuclear translocation of proviral DNA in growth-arrested cells. J Virol. 1998;72:4104–4115. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4104-4115.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piller S C, Ewart G D, Premkumar A, Cox G B, Gage P W. Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 forms cation-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:115–115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Planelles V, Jowett J B, Li Q-X, Xie Y, Hahn B, Chen I S. Vpr-induced cell cycle arrest is conserved among primate lentiviruses. J Virol. 1996;70:2516–2524. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2516-2524.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poon B, Jowett J B, Stewart S A, Armstrong R W, Rishton G M, Chen I S Y. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr gene induces phenotypic effects similar to those of the DNA alkylating agent, nitrogen mustard. J Virol. 1997;71:3961–3971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3961-3971.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Popov S, Rexach M, Ratner L, Blobel G, Bukrinsky M. Viral protein R regulates docking of the HIV-1 preintegration complex to the nuclear pore complex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13347–13352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Re F, Braaten D, Franke E K, Luban J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle in G2 by inhibiting the activation of p34cdc2-cyclin B. J Virol. 1995;69:6859–6864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6859-6864.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogel M E, Wu L I, Emerman M. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr gene prevents cell proliferation during chronic infection. J Virol. 1995;69:882–888. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.882-888.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roques B P, Morellet N, de Rocquigny H, Demene H, Schueler W, Jullian N. Structure, biological functions and inhibition of the HIV-1 proteins Vpr and NCp7. Biochimie. 1997;79:673–680. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)83501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sayle R A, Milner-White E J. RASMOL: biomolecular graphics for all. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:374. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selig L, Benichou S, Rogel M E, Wu L I, Vodicka M A, Sire J, Benarous R, Emerman M. Uracil DNA glycosylase specifically interacts with Vpr of both human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus of sooty mangabeys, but binding does not correlate with cell cycle arrest. J Virol. 1997;71:4842–4846. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4842-4846.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart S A, Poon B, Jowett J B, Chen I S Y. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr induces apoptosis following cell cycle arrest. J Virol. 1997;71:5579–5592. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5579-5592.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Subbramanian R A, Yao X J, Dilhuydy H, Rougeau N, Bergeron D, Robitaille Y, Cohen E A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr localization: nuclear transport of a viral protein modulated by a putative amphipathic helical structure and its relevance to biological activity. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:13–30. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tristem M, Marshall C, Karpas A, Hill F. Evolution of the primate lentiviruses: evidence from vpx and vpr. EMBO J. 1992;11:3405–3412. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vodicka M A, Koepp D M, Silver P A, Emerman M. HIV-1 Vpr interacts with the nuclear transport pathway to promote macrophage infection. Genes Dev. 1998;12:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang B, Ge Y, Palasanthiran P, Xiang S, Ziegler J, Dwyer D, Randle C, Dowton D, Cunningham A, Saksena N. Gene defects clustered at the C-terminus of the vpr gene of HIV-1 in long-term nonprogressing mother and child pair: in vivo evolution of vpr quasispecies in blood and plasma. Virology. 1996;223:224–232. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao X-J, Mouland A J, Subbramanian R A, Forget J, Rougeau N, Bergeron D, Cohen E A. Vpr stimulates viral expression and induces cell killing in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected dividing Jurkat T cells. J Virol. 1998;72:4686–4693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4686-4693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao X-J, Subbramanian R A, Rougeau N, Boisvert F, Bergeron D, Cohen E A. Mutagenic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr: role of a predicted N-terminal alpha-helical structure in Vpr nuclear localization and virion incorporation. J Virol. 1995;69:7032–7044. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7032-7044.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang C, Rasmussen C, Chang L-J. Cell cycle inhibitory effects of HIV and SIV Vpr and Vpx in the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Virology. 1997;230:103–112. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao Y, Cao J, O’Gorman M R G, Yu M, Yogev R. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protein R (vpr) gene expression on basic cellular function of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Virol. 1996;70:5821–5826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5821-5826.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao Y, Elder R T, Chen M Z, Cao J. Fission yeast expression vectors adapted for positive identification of gene insertion and GFP fusion. BioTechniques. 1998;25:2–4. doi: 10.2144/98253st06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao Y, Lieberman H B. Schizosaccharomyces pombe: a model for molecular studies of eukaryotic genes. DNA Cell Biol. 1995;14:359–371. doi: 10.1089/dna.1995.14.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao Y, Lu Y. Lithium-acetate based protocol for yeast transformation. In: Li Y M, Zhao Y, editors. Practical protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Science Press Ltd.; 1996. pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao Y, Yu M, Chen M, Elder R T, Yamamoto A, Cao J. Pleiotropic effects of HIV-1 protein R (Vpr) on morphogenesis and cell survival in fission yeast and antagonism by pentoxifylline. Virology. 1998;246:266–276. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]