Abstract

目的

探讨牙周炎对口腔鳞状细胞癌(oral squamous cell carcinoma, OSCC)发展的作用,明确牙周炎微生物是否诱导M2巨噬细胞极化并促进肿瘤进展。

方法

通过收集有无牙周炎的OSCC患者肿瘤组织,免疫组化验证M2巨噬细胞变化趋势;将连续3 d用含四联抗生素饮用水处理后的小鼠,每隔1 d涂牙周炎患者唾液集合菌5次,颊黏膜注射小鼠口腔鳞状细胞癌细胞(SCC7)建立伴牙周炎OSCC小鼠模型,观察牙周炎对OSCC发展的影响,分析肿瘤组织M2巨噬细胞含量,检测小鼠唾液菌群结构、脾脏和结肠组织的病理变化;最后,将收集的来自牙周炎患者的唾液,与小鼠外周血单个核细胞(PBMC)和SCC7细胞共同培养,流式细胞术检测M2巨噬细胞含量。

结果

临床样本的免疫组化结果显示,伴牙周炎OSCC患者(27.01%±2.12%)比不伴牙周炎OSCC患者(17.00%±3.66%)肿瘤组织中M2极化巨噬细胞增多(P<0.05)。伴牙周炎OSCC小鼠(PO组)肿瘤体积更大,生存率更低,Ki67阳性细胞表达率(35.49%±5.00%)高于OSCC组(O组)(23.89%±4.13%)(P<0.05);流式细胞术结果表明,PO组小鼠肿瘤组织中M2巨噬细胞含量(24.97%±4.41%)高于O组(5.75%±0.52%)(P<0.05),同时qPCR结果显示M2巨噬细胞相关因子Arg1、IL-10、CD206的表达总体呈现上升趋势;免疫组化结果表明PO组小鼠肿瘤组织中M2巨噬细胞阳性表达(21.82%±4.16%)相对O组(9.64%±0.60%)增加(P<0.05);PO组小鼠口腔菌群结构改变,条带增多,多样性增加,脾脏组织白髓减少,红髓分界不明,出血严重,结肠组织腺体形态异常,隐窝结构破坏较严重。细胞实验结果表明,PBMC与SCC7细胞共培时,牙周炎微生物的存在增加了M2巨噬细胞极化(71.00%±0.66%)。

结论

牙周炎促进了OSCC的发展,诱导肿瘤相关巨噬细胞向M2极化,牙周炎症治疗对OSCC患者具有重要价值。

Keywords: 肿瘤相关巨噬细胞, M2极化, 口腔鳞状细胞癌, 牙周炎

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the role of periodontitis in the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and to determine whether periodontitis microorganisms induce M2 macrophage (M2) polarization and promote tumor progression.

Methods

The tumor tissues of OSCC patients with periodontitis and those without periodontitis were collected and immunohistochemistry tests were done to validate the trend of changes in M2 macrophages. A mouse model of OSCC accompanied by periodontitis was established by treating mice with drinking water containing four antibiotics for three consecutive days, applying in the mouths of the mice a coat of bacteria collected from the saliva of patients with periodontitis once every other day for five times, and injecting in their buccal mucosa OSCC cells (SCC7). We observed the effect of periodontitis on the development of OSCC, analyzed the M2 macrophage content in the tumor tissues, and analyzed salivary microbiota structure, and examined the pathological changes in the spleen and colon tissues of the mice. Finally, we collected saliva from patients with periodontitis, co-cultured it with mice peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and SCC7 cells, and examined M2 macrophage percentage by flow cytometry.

Results

Immunohistochemical findings from the clinical samples showed that M2-polarized macrophages in OSCC patients with periodontitis were more enriched (27.01%±2.12%) compared with those of OSCC patients without periodontitis (17.00%±3.66%). The OSCC mice with periodontitis (PO group) had tumors of larger size and lower survival rate than OSCC mice (O group) did. Furthermore, the expression rate of Ki67-positive cells (35.49%±5.00%) was significantly higher than that of O group (23.89%±4.13%) (P<0.05). According to the results of flow cytometry, M2 macrophage expression (24.97%±4.41%) in PO group was higher than that of O group (5.75%±0.52%) (P<0.05). In addition, qPCR results showed that gene expression of M2 macrophage-related factors, Arg1, IL-10, and CD206, showed an overall upward trend. Immunohistochemistry results showed that the positive expression of M2 macrophages was significantly increased in the PO group (21.82%±4.16%) compared to that of the O group (9.64%±0.60%) (P<0.05). Mice in the PO group showed changes in their oral flora structure, exhibiting increased bands and diversity. The white pulp in their spleen tissue decreased and the boundary of the red pulp became indistinct with severe bleeding. The morphology of the colon glands was abnormal and the U-shaped crypt was damaged rather seriously. According to the results of cell experiment, when co-culturing PBMC with SCC7 cells, the presence of periodontitis microorganisms increased the polarization of M2 macrophages (71.00%±0.66%).

Conclusion

Periodontitis promotes the development of OSCC by inducing M2 polarization in tumor-associated macrophages. Hence, periodontitis treatment holds important values for OSCC patients.

Keywords: Tumor-associated macrophages, M2 polarization, Oral squamous cell carcinoma, Periodontitis

口腔鳞状细胞癌(oral squamous cell carcinoma, OSCC)是口腔颌面部最常见的恶性肿瘤[1],鉴于有转移和复发的趋势,OSCC患者通常需要化疗、放疗和手术联合治疗,但治愈率低[2],因此明确OSCC恶性进展的病因和机制,探索更有效的治疗策略至关重要。近年来流行病学和分子生物学研究表明,牙周炎作为一种高患病率的慢性炎症,是免疫细胞为响应微生物刺激渗入牙周组织时触发的炎症反应[3],其与OSCC的相互促进关系和炎性学说机制一直是口腔医学研究的热点,但具体机制并未得到很好阐释,尤其是发展中的肿瘤病变如何利用口腔免疫系统产生促肿瘤作用,这一过程如何受到共生菌群的影响仍有待深入研究[4]。

肿瘤相关巨噬细胞(tumor-associated macrophages, TAMs)作为肿瘤微环境(tumor microenvironment, TME)中的主要免疫细胞,可通过多种途径发挥促肿瘤及免疫抑制的作用,与肿瘤增殖、侵袭、耐药等有关[5]。根据表型和功能,巨噬细胞可分为M1和M2两种亚型,M1巨噬细胞可以吞噬和杀伤靶细胞,而M2巨噬细胞促进肿瘤的进展[6]。TME中TAMs细胞多数表现出M2极化特征,起到抑制肿瘤微环境免疫反应的作用。M2、M1比率失衡会导致多种疾病的发展[7],其中高M2/M1比率状态[8]与包括口腔癌在内的多种恶性肿瘤密切相关。此外,巨噬细胞作为最重要的免疫和炎症细胞之一,在宿主对牙周炎微生物感染的防御反应中发挥着重要作用[9],而OSCC患者中牙周炎对巨噬细胞的表达和变化的影响尚需要进一步研究。本研究拟通过建立伴牙周炎OSCC小鼠模型,研究牙周炎对OSCC的进展及M2巨噬细胞极化的影响,以期对OSCC的牙周炎病因防控提供理论依据。

1. 材料及方法

1.1. 临床样本收集

告知患者研究内容并获得知情同意书后,收集四川大学华西口腔医院口腔颌面外科手术患者的OSCC肿瘤组织10例,包括OSCC无牙周炎患者肿瘤组织5例(O组),伴牙周炎OSCC患者肿瘤组织5例(PO组)。患者在术前进行牙周检查,术中收集肿瘤组织。本研究同时收集3例慢性牙周炎患者唾液与3例健康人唾液各2 mL。纳入标准——牙周炎患者:①均由口腔医生仔细检查,临床附着丧失(+),探诊出血阳性(+),探诊深度大于3 mm,牙齿松动,确诊为慢性牙周炎;②1年内未接受任何牙周治疗;③无其他颌面部或全身感染性疾病;④近1个月内未接受抗生素治疗。OSCC患者:①病理诊断为OSCC;②除OSCC外无其他部位原发恶性肿瘤以及严重全身性疾病;③入院前未接受放化疗及手术等其他相关治疗。将收集的同组志愿者的唾液混合、离心后收集沉淀、等分并迅速冷冻保存,以备牙周炎涂菌处理和细胞共培。本研究得到四川大学华西口腔医院医学伦理委员会的批准(WCHSIRB-OT-2019-015),所有实验均按相关规定进行。

1.2. 动物模型建立

实验动物购自成都达硕实验动物有限公司,选取5周龄SPF雄性Balb/c健康小鼠。动物实验经四川大学华西口腔医院医学伦理委员会的批准(WCHSIRB-D-2019-015)。

将22只小鼠随机分组,空白对照组(Con组,n=3):健康小鼠不做任何处理。牙周炎组(P组,n=3):连续3 d用含四联抗生素〔氨苄青霉素(1 g/L, Solarbio Cat# A8180-1)、三硫酸新霉素(1 g/L, MCE Cat# HY-B0470)、甲硝唑(1 g/L, MCE Cat# HY-B0318)、万古霉素(500 mg/L, MCE Cat# HY-B0671)〕饮用水处理后,每隔1 d在小鼠口内涂菌100 μL(1.1收集,处理5次)。OSCC组(O组,n=6):SCC7细胞(来自口腔疾病研究国家重点实验室,四川大学华西口腔医院)胰酶消化后,1000 r/min离心,PBS重悬,将细胞密度调整为5×106/50 μL,经小鼠口腔颊黏膜下注射50 μL。伴牙周炎OSCC组(PO组,n=10):连续3 d用含四联抗生素饮用水处理后的小鼠,每隔1 d涂菌100 μL(处理5次),且在最后一次涂菌时颊黏膜注射SCC7细胞(5×106/50 μL)。所有的小鼠在最后一次涂菌处理后第12天安乐死,收集小鼠的颊黏膜组织、肿瘤组织、脾脏组织、结肠组织和小鼠口腔唾液拭子,以进行后续实验。

1.3. 免疫组织化学染色与HE染色

取实验小鼠颊黏膜或肿瘤组织,以及OSCC患者术后肿瘤组织,根据通用SP试剂盒(ZSGB-BIOCat# SP-9000)说明书进行染色,经固定、脱水、包埋、切片、脱蜡、水化、抗原修复、封闭、一抗Ki67 (1∶100, Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 12202)、anti-CD86 (1∶100, Bioss Cat# bs-1035 R)或anti-CD206 (1∶100, Proteintech Cat# 18704-1-AP)孵育、DAB显色(ZSGB-BIO Cat# ZLI-9018)、苏木素复染、固封,以PBS缓冲液代替一抗作为阴性对照,阳性着色为棕黄色,使用Image J软件进行量化和归一化分析。

切取各组小鼠的1/4脾脏组织、2 cm结肠组织加工,固定脱水后包埋在石蜡中,制备5 μm切片。根据试剂产品说明书(Solarbio Cat# G1120)进行HE染色。观察脾脏和结肠组织的病理情况。

1.4. PCR-变性梯度凝胶电泳(PCR-DGGE)检测小鼠口腔菌群组成变化

收集小鼠的口腔唾液拭子于无菌离心管中,按照细菌基因组DNA提取试剂盒(Tiangen Cat# DP302)说明书提取口腔微生物组总DNA,用合成引物(Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)对口腔细菌16S rRNA V3区进行PCR扩增[10]〔primer-F: 5′-GC clamp-CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC AG-3′; primer-R: 5′-ATT ACC GCG GCT GCT GG- 3′; GC clamp(CGC CCG CCG CGC GCG GCG GGC GGG GCG GGG GCA CGG GGG G)〕,采用8%聚丙烯酰胺凝胶进行分离,变性浓度为40%~60%,在1×TAE电泳缓冲液中(60 ℃, 20 V, 30 min; 50 V, 12 h)电泳结束后稍冷却,按1∶10000倍稀释Goldview染料(中晖赫彩Cat#NE006)15 μL到150 mL的1×TAE缓冲液中,混匀加到胶表面,确保所有表面都覆盖到,染胶20 min,通过ChemiDoc MP化学发光凝胶成像系统扫描成像。

1.5. 实时荧光定量PCR检测组织中炎症相关因子和M1、M2相关基因的表达

收集各组小鼠的颊黏膜和肿瘤组织提取总RNA(Yeasen Cat# 19221ES50),检测纯度及浓度。逆转录试剂盒(Yeasen Cat# 11142ES60)合成cDNA后,根据试剂盒说明书(Yeasen Cat# 10148ES60),检测炎症相关因子TNF-α、IL-6以及M2、M1相关基因Arg1、IL-10、CD206、CD86、iNOS表达。以GAPDH为内参,采用2−ΔΔCt法分析各基因表达水平。引物序列见表1。

表 1. Primer sequences used for real-time PCR analysis.

实时荧光定量PCR引物序列

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′-3′) |

| TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL-6: interleukin 6; Arg1: arginase-1; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL-10: interleukin-10; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. | |

| TNF-α | F: GACGTGGAACTGGCAGAAGAG |

| R: TTGGTGGTTTGTGAGTGTGAG | |

| IL-6 | F: GAGGATACCACTCCCAACAGACC |

| R: AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCATACA | |

| Arg1 | F: CTCCAAGCCAAAGTCCTTAGAG |

| R: AGGAGCTGTCATTAGGGACATC | |

| iNOS | F: GTTCTCAGCCCAACAATACAAGA |

| R: GTGGACGGGTCGATGTCAC | |

| IL-10 | F: GGTTGCCAAGCCTTATCGGA |

| R: ACCTGCTCCACTGCCTTGCT | |

| CD206 | F: CTCTGTTCAGCTATTGGACGC |

| R: CGGAATTTCTGGGATTCAGCTTC | |

| CD86 | F: TGTTTCCGTGGAGACGCAAG |

| R: TTGAGCCTTTGTAAATGGGCA | |

| GAPDH | F: AGGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCA |

| R: CCAGGAAATGAGCTTGACAAA | |

1.6. 流式细胞术检测组织中M2巨噬细胞的含量

取小鼠颊黏膜和肿瘤组织,加入少量DMEM培养基,剪成1 mm3组织碎块,PBS清洗3次,转入15 mL离心管,根据试剂产品说明书加入胶原酶(BioFroxx Cat# 2091; Absin Cat# 47047496),37 ℃恒温摇床消化组织至光镜下呈絮状,离心弃上清,加入PBS清洗细胞,离心弃上清,加入2%FBS-PBS制备细胞悬液,70 μm滤膜过滤。加入Fixable Viability Kit(BioLegendCat# L423105)染色并用TruStain FcX(BioLegend Cat# 101320)封闭后,按照试剂说明书将细胞与以下抗体共同孵育:CD45(1.25 μL/100 μL, BioLegend Cat# 103140)、F4/80(1 μL/100 μL, BioLegend Cat# 123130)、CD206(2.5 μL/100 μL, BioLegend Cat# 141706),加入含0.1%BSA的预冷PBS 4 ℃孵育60 min,含0.1%BSA的预冷PBS冲洗2次,固定后在Attune NxT流式细胞仪上检测,并通过FlowJo(V10.8)软件分析数据。

1.7. 细胞培养

将SCC7细胞培养于含有10%FBS(Gibco)的DMEM(Gibco)高糖培养基中,使用外周血淋巴细胞分离溶液(Salarbio Cat# P6340、Cat# P8900)从小鼠外周血中提取出外周血单个核细胞(peripheral blood mononuclear cell, PBMC)。PBMC培养于含10%FBS的RPMI 1640(Gibco)培养基中,置于含体积分数5%CO2、37 ℃的恒温恒湿培养箱中培养。

1.8. 流式细胞术检测体外共培养细胞中M2巨噬细胞的表达

将1.1步骤中收集的1.5 μg唾液沉淀于70 ℃下10 min热灭活。将准备好的5×105个PBMC(Control组)分别与1.5 μg唾液沉淀(Bac 6H组)、热灭活1.5 μg唾液沉淀(Dead Bac 6H组)、或牙龈卟啉单胞菌脂多糖(LPS-Pg)(LPS 6H组)(100 ng/mL, InvivoGen Cat# 185 tlrl-pglps)共培养6 h。将PBMC(5×105个)(Control组)分别与SCC7细胞(5×106个)(With SCC7组)、1.5 μg唾液沉淀(With Bac组)或三者(With Bac and SCC7组)共培养6 h,分别收集细胞悬液,按1.6步骤进行染色、检测和分析。

1.9. 统计学方法

采用GraphPad Prism v.7.04软件进行统计学分析。计量资料以 表示。两组间比较采用t检验,多组间比较采用ANOVA检验,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

表示。两组间比较采用t检验,多组间比较采用ANOVA检验,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 伴牙周炎OSCC患者肿瘤组织中M2极化增多

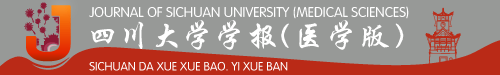

免疫组化结果显示,收集的10例患者肿瘤组织巨噬细胞均为阳性,其中PO组(27.01%±2.12%)肿瘤组织中M2巨噬细胞表达高于O组(17.00%±3.66%)肿瘤组织(P<0.05)(图1A),M1巨噬细胞在PO组(16.36%±1.79%)与O组(15.89%±4.68%)间的表达差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)(图1B)。

图 1.

Macrophages in OSCC patients' tumor tissues

OSCC患者肿瘤组织中巨噬细胞的水平

A: IHC staining of CD206 in tumor tissues; B: IHC staining of CD86 in tumor tissues. The red arrows are pointed at some representative positive cells. O: OSCC group; PO: OSCC group with periodontitis.

2.2. 牙周炎促进OSCC进展

小鼠荷瘤模型显示,PO组在第6天开始死亡,生存率更低,O组在第9天开始死亡,P组和Con组小鼠在实验过程中无死亡(图2A)。小鼠肿瘤组织的大体图显示,PO组肿瘤体积更大(图2B),且肿瘤组织质量更重。小鼠肿瘤组织的免疫组化结果显示,PO组小鼠肿瘤组织的Ki67阳性细胞表达率高于O组(P<0.05)(图2D)。qPCR检测结果(图2C、2E)显示,由于牙周炎的存在,口腔黏膜的炎症因子TNF-α和IL-6表达上升,P组与Con组间TNF-α和IL-6的表达差异无统计学意义,PO组IL-6表达相对O组更高(P<0.05)。

图 2.

Periodontitis promotes OSCC progression in mice

牙周炎促进小鼠OSCC进展

A: the survival rate of mice in each group; B: the mice were sacrificed and the tumor tissues were collected; C: the mRNA level of TNF-α was determined by qPCR; D: IHC staining of Ki67-positive cells in tumor tissues (the red arrows are pointed at some representative positive cells); E: the mRNA level of IL-6 was determined by qPCR. * P<0.05. Con: control group; P: periodontitis group; O: OSCC group; PO: OSCC group with periodontitis. n=3.

2.3. 牙周炎影响OSCC小鼠脾脏和结肠组织的病理状态

HE染色结果显示,与Con组相比,P组脾脏组织出现充血,O组和PO组脾脏组织白髓减少,红髓分界不明,出血严重(图3A)。Con组小鼠结肠黏膜形态正常,结构规则,P组炎性浸润程度较高,PO组和O组结肠腺体形态异常,U型隐窝结构破坏较严重,PO组结肠结构破坏较O组更大(图3B)。

图 3.

Periodontitis affects the histopathological state of the spleen and colon in OSCC mice

牙周炎影响OSCC小鼠脾脏和结肠的组织病理状态

A: HE staining of the spleen; B: HE staining of the colon. The red arrow are pointed at the typical pathological changes. Con, P, O, and PO denote the same as those in Fig 2.

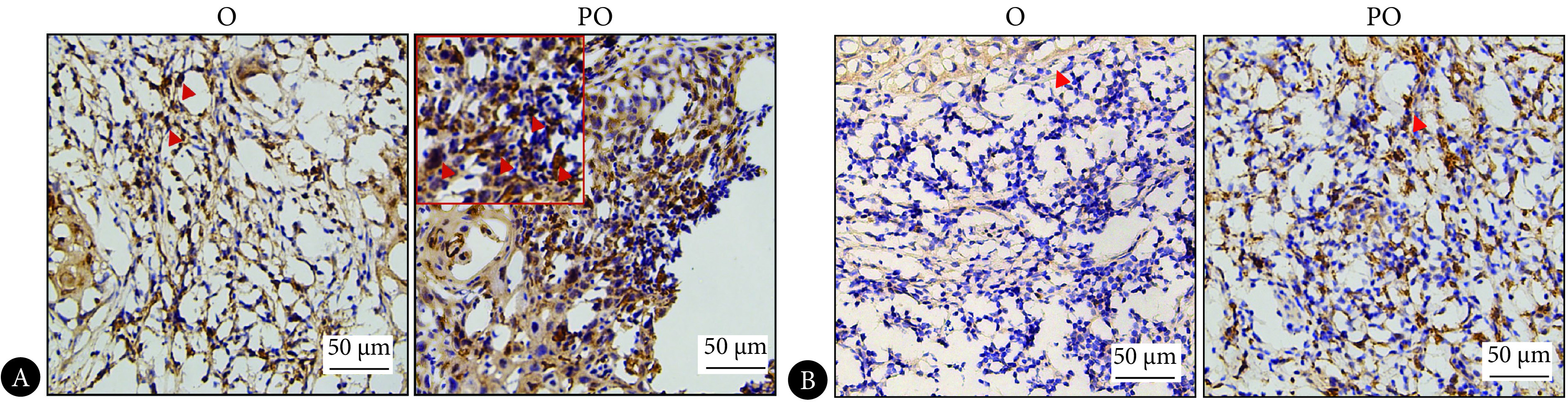

2.4. 伴牙周炎OSCC小鼠肿瘤组织中M2极化增多

流式细胞术结果显示(图4A、4B),各组小鼠颊黏膜或肿瘤组织中巨噬细胞数量差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);Con组与P组相比M2巨噬细胞数量无明显差异(P>0.05),PO组M2巨噬细胞多于O组(P<0.05)。免疫组化结果显示(图4C),在小鼠的颊黏膜组织或肿瘤组织中,Con组与P组比较M2巨噬细胞阳性率无明显差异(P>0.05),PO组M2巨噬细胞阳性率高于O组(P<0.05)。进一步采用qPCR检测O组和PO组M1和M2巨噬细胞相关基因的表达,结果显示(图4D),与O组相比,PO组M2巨噬细胞相关基因Arg、IL-10和CD206的表达增加(P<0.05),M1巨噬细胞相关基因CD86和iNOS的表达无明显差异(P>0.05)。

图 4.

Expression of M2 macrophages in mice tumor tissues

小鼠肿瘤组织中M2巨噬细胞的含量

A: Flow cytometry was used to identify the percentage of macrophages in mice tumor tissues and buccal mucosa tissues; B: flow cytometry was used to identify the percentage of M2 macrophages in mice tumor tissues and buccal mucosa tissues; C: CD206 IHC staining in tumor tissues and buccal mucosa tissues (the red arrows are pointed at some representative positive cells); D: the mRNA level of Arg, IL-10, CD206, CD86, and iNOS were determined by qPCR. * P<0.05. Con, P, O, and PO denote the same as those in Fig 2. n=3.

2.5. 牙周炎微生物促进M2巨噬细胞极化

PCR-DGGE结果显示牙周炎微生物会进一步改变OSCC荷瘤小鼠口腔菌群组成(图5A),P组相对Con组条带减少,部分条带浓度增强如蓝框所示,而PO组相对O组细菌条带数增多明显如红框所示。为了评估免疫细胞对牙周炎微生物的反应,将来自小鼠的PBMC与不同方式处理的牙周炎微生物一起孵育,流式细胞术显示,PBMC分别与LPS-Pg(LPS 6H组)、热灭活的牙周炎微生物(Dead Bac 6H组)、牙周炎微生物(Bac 6H组)培养,各组之间M2极化细胞差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)(图5B);PBMC与SCC7细胞(With SCC7组)共培时M2巨噬细胞极化水平较对照组增加(P<0.05),当牙周炎微生物同时存在的情况下(With Bac and SCC7组),M2巨噬细胞极化水平较With SCC7组进一步增加(P<0.05)(图5C)。

图 5.

Effects of periodontitis microbiome on M2 macrophage polarization

牙周炎微生物对M2巨噬细胞极化的影响

A: PCR-DGGE (the blue box indicates the band with increased concentration, and the red boxes indicate newly appeared bands); B: flow cytometry was used to assess the CD206 percentage after co-culturing PBMC with differently treated periodontitis microbiome or LPS; C: CD206 percentage in co-culturing of PBMC, periodontitis microbiome, and SCC7 cells. * P<0.05. Con, P, O, and PO denote the same as those in Fig 2. Control: PBMC cells; LPS 6H: co-culturing of PBMC with LPS; Dead Bac 6H: co-culturing of PBMC with inactivated periodontitis microorganisms; Bac 6H: co-culturing of PBMC with periodontitis microorganisms; With Bac: co-culturing of PBMC with periodontitis microorganisms; With SCC7: co-culturing of PBMC with SCC7 cells; With Bac and SCC7: co-culturing of PBMC with periodontitis microorganisms and SCC7 cells. n=3.

3. 讨论

牙周炎作为发生在牙周支持组织的慢性炎症[11-12],不但可以诱发组织损伤,还可以刺激特定的炎性细胞因子[13]。巨噬细胞作为最重要的免疫和炎症细胞之一,在抗牙周病原体反应中发挥重要作用,可能引起组织损伤以及细胞因子的变化[14],这种炎症环境为癌细胞迁移、增殖和免疫逃逸提供了可能[15-16]。在口腔癌前病变中由于牙周炎引发的炎症反应,可能促进以M1为主的TAMs经过复杂、多步骤的过程,向M2巨噬细胞极化,促使口腔癌前病变向口腔癌进展[17]。本研究发现,在动物模型上,接种牙周炎患者的口腔微生物可以使OSCC小鼠的肿瘤体积变大,牙周炎加快了小鼠OSCC肿瘤细胞活跃程度,降低了小鼠的生存率,使OSCC小鼠肿瘤组织中M2巨噬细胞极化增加。

癌症进展受TME的影响很大,其中TME包括免疫细胞和微生物等。牙周炎使口腔微生物群结构发生变化,其特征是炎症细胞的浸润和炎症因子的积累,包括细胞因子、趋化因子以及刺激细胞增殖、血管生成、组织重塑或转移的促炎因子[18]。牙周病原体在癌症和癌旁组织中富集,而癌组织和龈下菌斑之间的细菌谱相似,其中牙龈卟啉单胞菌感染与口腔癌晚期患者淋巴结转移呈正相关,伴有牙周袋较深、临床附着缺失严重、牙齿脱落[19]。同时牙周炎伴随着口腔细菌群落和肿瘤免疫微环境的改变,牙周炎口腔菌群在OSCC合并牙周炎的全过程中保持优势地位,其中卟啉单胞菌属数量最多,牙周炎口腔微生物群引起的肿瘤相关免疫反应可能作为口腔共生菌与免疫细胞联合治疗的潜在靶标[17]。本研究发现,牙周炎微生物与PBMC共培时,对M2极化的影响无明显差异;在肿瘤细胞与PBMC共培环境中,M2巨噬细胞极化较对照组增多;值得注意的是,当肿瘤细胞、PBMC和牙周炎微生物共同存在时,M2极化水平最高,表明牙周炎微生物单独刺激不能有效使TAMs向M2极化,但在TME中,牙周炎微生物可大量刺激M2巨噬细胞极化。

越来越多的研究显示,牙周炎的优势菌与OSCC的发展同样有密切的关系。本研究将牙周炎患者唾液微生物接种到OSCC动物模型里,结果证实伴牙周炎OSCC小鼠口腔菌群结构改变,牙周炎组相对正常组条带减少,可能是牙周炎引起的口腔内正常的微生物群落结构被破坏后[17],某些具有致病性的细菌占优势,例如牙龈卟啉单胞菌和具核梭杆菌[20],从而抑制其他细菌的生长,造成微生物群落结构较单一,可检出的条带数较少,而伴牙周炎OSCC组相对OSCC组细菌条带数增多,可能是因为OSCC口腔内富集牙周致病菌的同时[21],牙周炎使口腔微生物群落结构改变,菌群失衡,可检出的条带数增加[22]。同时牙周炎致病菌与多种系统性疾病的发生密切相关,甚至在口腔以外的其他远端系统器官可以检测到牙周炎致病菌的DNA片段[23],在疾病状态下,牙周炎致病菌可以在口腔以外的远端器官定植,并且影响远端器官的生理状态[24]。同时,由于“口-肠轴”的存在,口腔被视为具有肠道定植能力的机会致病菌的储存库[25]。易位的口腔菌可能引起或加剧炎性肠病[26]等多系统的机会感染。脾脏和结肠作为全身免疫系统的两大重要免疫器官,本研究对脾脏和结肠组织进行了HE染色,比较伴牙周炎OSCC对这两大免疫器官的作用。结果显示牙周炎产生的炎症反应加重了OSCC小鼠的脾脏和结肠组织的病理损伤。因此,本研究不仅显示了牙周炎微生物使OSCC中M2巨噬细胞极化增多,同时提示牙周炎促进OSCC的过程中可能也涉及了全身免疫的变化,包括重大免疫器官的改变。

总之,本研究结果强调牙周炎会影响OSCC的发展。牙周炎使小鼠OSCC肿瘤体积增大,增强了肿瘤细胞增殖活跃程度,伴随口腔微生物组成改变,脾脏和结肠组织病理损伤加重,肿瘤组织M2巨噬细胞极化增加;在癌细胞、免疫细胞和细菌共同存在时,M2巨噬细胞极化增多;同时,伴牙周炎OSCC临床样本肿瘤组织中巨噬细胞M2极化显著增多。因此,本研究提示,牙周炎症治疗对OSCC患者临床预后具有重要意义。关于牙周炎是否会通过影响癌症的免疫环境,干预癌症的免疫治疗,牙周炎微生物在肿瘤促进的炎症和抗肿瘤免疫之间的功能,本课题组后续将通过进一步体内实验进行深入探讨。

* * *

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

Funding Statement

四川省科技厅重点研发项目(No. 2020YFSY0008)资助

Contributor Information

佳 李 (Jia LI), Email: lijiahh2021@163.com.

燕 李 (Yan LI), Email: feifeiliyan@163.com.

References

- 1.DU M, NAIR R, JAMIESON L, et al Incidence trends of lip, oral cavity, and pharyngeal cancers: global burden of disease 1990-2017. J Dent Res. 2020;99(2):143–151. doi: 10.1177/0022034519894963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MUZAFFAR J, BARI S, KIRTANE K, et al Recent advances and future directions in clinical management of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(2):338. doi: 10.3390/cancers13020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LI X, TANG L, YE MYAT T, et al Titanium ions play a synergistic role in the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in Jurkat T cells. Inflammation. 2020;43(4):1269–1278. doi: 10.1007/s10753-020-01206-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CHEN P J, CHEN Y Y, LIN C W, et al Effect of periodontitis and scaling and root planing on risk of pharyngeal cancer: a nested case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):8. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.PAN Y, YU Y, WANG X, et al Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2020;11:583084. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.583084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.HWANG I, KIM J W, YLAYA K, et al Tumor-associated macrophage, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis markers predict prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):443. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02618-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WU K, LIN K, LI X, et al Redefining tumor-associated macrophage subpopulations and functions in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1731. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WANG H, YUNG M M H, NGAN H Y S, et al The impact of the tumor microenvironment on macrophage polarization in cancer metastatic progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6560. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CHEN X, DOU J, FU Z, et al Macrophage M1 polarization mediated via the IL-6/STAT3 pathway contributes to apical periodontitis induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Appl Oral Sci. 2022;30:e20220316. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2022-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WU X, MA C, HAN L, et al Molecular characterisation of the faecal microbiota in patients with type Ⅱ diabetes. Curr Microbiol. 2010;61(1):69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.QIN Z Y, GU X, CHEN Y L, et al Toll-like receptor 4 activates the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway and periodontal inflammaging by inhibiting BMI-1 expression. Int J Mol Med. 2021;47(1):137–150. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.JANG H M, PARK J Y, LEE Y J, et al TLR2 and the NLRP3 inflammasome mediate IL-1β production in Prevotella nigrescens-infected dendritic cells. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18(2):432–440. doi: 10.7150/ijms.47197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.KOUKETSU A, SATO I, OIKAWA M, et al Regulatory T cells and M2-polarized tumour-associated macrophages are associated with the oncogenesis and progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48(10):1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HU X, SHEN X, TIAN J The effects of periodontitis associated microbiota on the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;576:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.07.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WETZEL A, BONNEFOY F, CHAGUÉ C, et al Pro-resolving factor administration limits cancer progression by enhancing immune response against cancer cells. Front Immunol. 2021;12:812171. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.812171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ELEBYARY O, BARBOUR A, FINE N, et al The crossroads of periodontitis and oral squamous cell carcinoma: immune implications and tumor promoting capacities. Front Oral Health. 2020;1:584705. doi: 10.3389/froh.2020.584705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DHINGRA K Is periodontal disease a risk factor for oral cancer? Evid Based Dent. 2022;23(1):20–21. doi: 10.1038/s41432-022-0245-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ROUTY B, Le CHATELIER E, DEROSA L, et al Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359(6371):91–97. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.KAVARTHAPU A, GURUMOORTHY K Linking chronic periodontitis and oral cancer: a review. Oral Oncol. 2021;121:105375. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.GENG F, ZHANG Y, LU Z, et al Fusobacterium nucleatum caused DNA damage and promoted cell proliferation by the Ku70/p53 pathway in oral cancer cells. DNA Cell Biol. 2020;39(1):144–151. doi: 10.1089/dna.2019.5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.李玉超. 牙龈癌与牙周炎患者口腔菌群结构的比较和分析: 共性与差异. 沈阳: 中国医科大学, 2020. doi: 10.27652/d.cnki.gzyku.2020.001018.

- 22.WEI W, LI J, SHEN X, et al Oral microbiota from periodontitis promote oral squamous cell carcinoma development via γδ T cell activation. mSystems. 2022;7(5):e0046922. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00469-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NASIDZE I, LI J, QUINQUE D, et al Global diversity in the human salivary microbiome. Genome Res. 2009;19(4):636–643. doi: 10.1101/gr.084616.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.KITAMOTO S, NAGAO-KITAMOTO H, JIAO Y, et al The intermucosal connection between the mouth and gut in commensal pathobiont-driven colitis. Cell. 2020;182(2):447–462.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.READ E, CURTIS M A, NEVES J F The role of oral bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(10):731–742. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ATARASHI K, SUDA W, LUO C, et al Ectopic colonization of oral bacteria in the intestine drives T(H)1 cell induction and inflammation. Science. 2017;358(6361):359–365. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]