Abstract

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) framework has contributed to advances in developmental science by examining the interdependent and cumulative nature of adverse childhood environmental exposures on life trajectories. Missing from the ACEs framework, however, is the role of pervasive and systematic oppression that afflicts certain racialized groups and that leads to persistent threat and deprivation. In the case of children from immigrant parents, the consequence of a limited ACEs framework is that clinicians and researchers fail to address the psychological violence inflicted on children from increasingly restrictive immigration policies, ramped up immigration enforcement, and national anti-immigration rhetoric. Drawing on the literature with Latinx children, the objective of this conceptual article is to integrate the ecological model with the dimensional model of childhood adversity and psychopathology to highlight how direct experience of detention and deportation, threat of detention and deportation, and exposure to systemic marginalization and deprivation are adverse experiences for many Latinx children in immigrant families. This article highlights that to reduce bias and improve developmental science and practice with immigrants and with U.S.-born children of immigrants, there must be an inclusion of immigration-related threat and deprivation into the ACEs framework. We conclude with a practical and ethical discussion of screening and assessing ACEs in clinical and research settings, using an expanded ecological framework that includes immigration-related threat and deprivation.

Keywords: Immigration, Threat, Adverse childhood experience, Deprivation, Screening, Latinx, Health, Mental health

1. Introduction

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) framework (Felitti et al., 1998) has primarily focused on childhood adversities originating in the home, unintentionally failing to identify the pervasive and systematic oppression that afflicts certain groups in the United States (U.S.), such as Latinx immigrants (Flores and Salazar, 2017). Newer ACEs-based screening tools include one or more early adversities related to socio-structural conditions (e.g. exposure to neighborhood or school violence; Oh et al., 2018). However, the psychological violence inflicted on children from immigrant families from increasingly restrictive immigration policies, ramped up enforcement in the U.S. interior, and national anti-immigration rhetoric (Barajas-Gonzalez et al., 2018; Grace et al., 2018) remains to be fully addressed. We propose an expanded ACE framework to include the detrimental threat and deprivation that children in immigrant families endure in restrictive, anti-immigrant sociopolitical contexts. We propose adding distinct, yet related and often co-occurring, immigration-related events, using an adapted dimensional model of threat and deprivation associated with commonly occurring ACEs (McLaughlin and Sheridan, 2016). Although Latinx children are not the only ethnic/racial group affected by restrictive immigration policy and practices, their parents are the most represented in the population targeted by policy and practice (Golash-Boza and Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2013; Massey and Pren, 2012; Provine, 2013), and hence, there is more literature on Latinx children and their families compared to any other group. Our proposed framework is therefore specific to Latinx children in immigrant families.

1.1. Restrictive immigration policies affect children in immigrant families

Restrictive immigration policies and enforcement strategies include family marginalization, Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE) raids in U.S. communities, detention, and deportation, which create chronic uncertainty about family safety and preservation and may function as a form of psychological violence for children in immigrant families (Barajas-Gonzalez et al., 2018). Barajas-Gonzalez et al. (2018) applied ecological-transactional theory to delineate how chronic uncertainty about safety and threat of family separation adversely impact Latinx children in immigrant families Ecological-transactional theory (Cicchetti and Lynch, 1993) posits that a child functions within multiple contexts, or ecologies, that influence each other as well as the child’s development. These ecologies vary in their proximity to the child and include (a) the macrosystem, the most distal ecology, which includes societal values (e.g., anti-immigrant rhetoric) and policies (e.g., aggressive immigration enforcement) that shape how society functions; (b) the exosystem, which consists of community settings in which families and children live, e.g., exposure to community violence, uncertainty regarding safety and rights; (c) the microsystem, which represents individuals in the proximal ecologies with whom the child directly interacts, e.g., the family, peers, school staff, health care professionals; (d) the mesosystem, meaning interactions between various microsystems, e. g., the parent experiencing hostile remarks from a teacher; and (e) the ontogenic level, which consists of factors within the child that influence development, e.g., awareness of deportation.

Interactions among multiple ecologies can also occur. For example, immigrant parents’ difficulty accessing social services may affect a child’s nutrition and health (e.g. microsystem impacting ontogenic; Yoshikawa, 2011). Exposure to immigration enforcement threat during middle childhood (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2011) creates disturbances within the family that can disrupt child development, such as restricting activities outside the home and avoiding conversation regarding certain stressful topics (Ayón, 2017a; Castañeda, 2019; Gulbas and Zayas, 2017). In turn, the isolation resulting from restriction of outdoor and extracurricular activities (Gonzales et al., 2013; McConnell et al., 2020) and avoidance of certain family interactions is associated with anxiety and depression in Latinx youth (Castañeda, 2019; Horner et al., 2014). These risks may be heightened in adolescence, when interactions outside the immediate family are crucial to autonomy and identity formation (Gonzales et al., 2013; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2011). We can consider the emerging scholarship on the impact of parental deportation within the established literature on one of the original ACEs: incarceration of a parent. Following parental incarceration, children endure traumatic separation, stigma, strained parenting, reduced family income, unstable childcare arrangements, and home and school instability (Murray et al., 2012). These challenges explain why this adverse childhood experience predicts negative consequences into adolescence and adulthood, including 3–4 higher odds of delinquent behavior, 2.5 higher odds of mental health problems, and increased likelihood of substance use, unemployment, relationship problems (Makariev and Shaver, 2010; Murray and Murray, 2010). Finally, for immigrant children, macro-system level policies result in increasingly severe levels of threat and deprivation that affect individual children’s health and well-being, such as the exclusion of immigrants with undocumented legal status from COVID-19 federal relief efforts and penalizing access to Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) by including them in the public charge rule (Gonzalez et al., 2020; Perreira et al., 2018). Despite the evidence about the impact of restrictive immigration policies on children, immigration-related adversity has not been incorporated into ACE frameworks.

1.2. Extension of the ACEs framework to incorporate immigration-related adversity

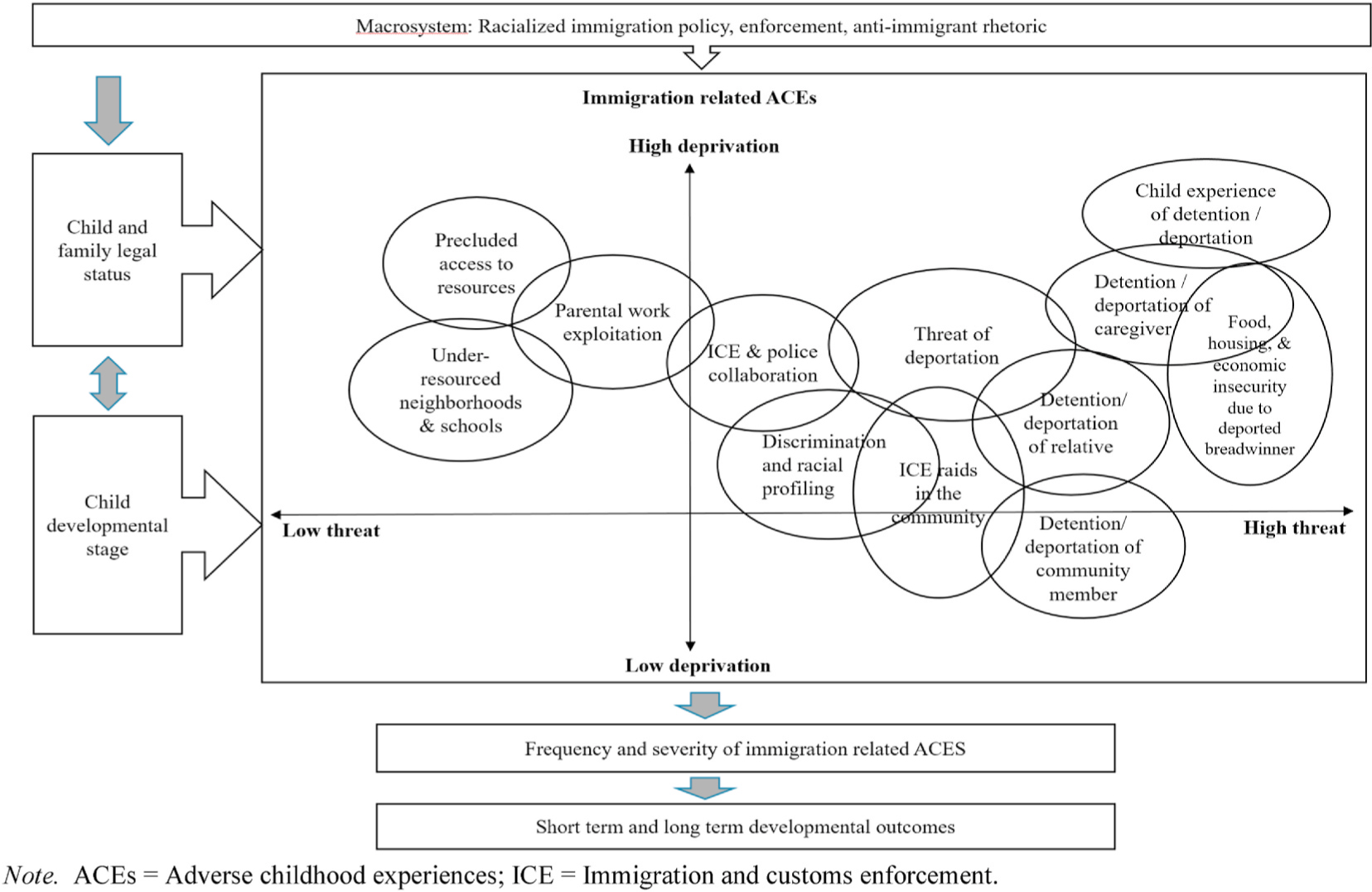

We build on our understanding of immigration policies and enforcement as a form of psychological violence by considering the continua of threat and deprivation experienced by children in immigrant families (see Fig. 1). We tailored the dimensional model of childhood adversity and psychopathology (DMAP; McLaughlin et al., 2014; Sheridan and McLaughlin, 2020) to illustrate how restrictive immigration policies and enforcement—and threat of enforcement—function as anticipatory stressors that can become chronic stressors (Garcia, 2018), a disruption to family preservation and unity, and a pervasive threat to children’s sense of safety.

Fig. 1.

Immigration-Related Adverse Childhood Experiences Model. Note. ACEs = Adverse childhood experiences; ICE = Immigration and customs enforcement.

The DMAP proposes that across the range of ACEs, different types of adversity share common features that can be conceptualized along two dimensions of environmental experience: (a) harm or threat of harm to the child or a loved one (“threat”), and/or (b) experiences involving an absence of expected cognitive and social stimulation from the environment (“deprivation”) (McLaughlin and Sheridan, 2016). McLaughlin and Sheridan (2016) critique the cumulative approach to measuring childhood adversity as implying that all ACEs affect children’s social emotional development similarly. They provide empirical support to demonstrate that experiences of deprivation, such as poverty, affect children’s development primarily through their influences on verbal and executive functioning. Experiences of harm or threat, such as physical abuse, affect children’s fear-learning, emotional reactivity, and emotion regulation. In the original model, some experiences (e.g., institutionalization) may involve both high threat and deprivation. We suggest that ACEs resulting from psychological violence due to immigration enforcement and exposure can be mapped onto threat and deprivation axes.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, children’s experiences of threat and deprivation due to immigration policies and an anti-immigrant climate will vary according to both the child and family members’ legal statuses and the child’s developmental stage. Based on these factors, frequency and severity of ACEs will fluctuate, differentially influencing short and long-term effects on the child’s development. For example, the systemic exclusion and marginalization of immigrants contributes to difficulty accessing resources, under-resourced and disinvested environments (schools, neighborhoods), and parental employment exploitation, all of which contribute to conditions of deprivation for the child. Deprivation increases in intensity, mapping onto documentation status of the child and family (“a continuum of social stratification that incorporates nativity, citizenship, and legal status,” McConnell et al., 2020, p. 79), where those with citizen status are the least vulnerable and those with undocumented status are the most vulnerable to exploitation and exclusion. Threat can be at low levels if the child has no legal vulnerability (e.g., child is a U.S.-born citizen and the family has permanent legal status in the U.S.). We indicate this level of threat as “low” rather than “no” threat because of the precariousness of “legality” for those whose parents have permanent or discretionary status (Castañeda, 2019; Menjívar, 2006). Also, the race and ethnicity of the child and of the child’s family members will influence the likelihood that someone in the family will be discriminated against given the racialization of immigration, with those presenting as White less likely to be policed (Castañeda, 2019; Getrich, 2013). We thus conceptualize discrimination, racial profiling, and local police collaboration with federal immigration enforcement as falling along the threat axis (Fig. 1). However, these factors may also contribute to deprivation. For example, a child may not attend school or go to a doctor’s appointment due to generalized fear in the community following an immigration raid. Finally, direct experiences with immigration enforcement through detention and deportation are conceptualized on a continuum, from the lower levels—Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE raids) in the community or deportation of a community member—to the highest level of threat and deprivation—a child or their caregiver is detained or deported.

Our tailored model of ACEs highlights the intersectionality of risks that children in immigrant families experience in a restrictive, anti-immigrant sociopolitical climate. For example, a child can be in a low threat, high deprivation setting (Fig. 1, upper left quadrant) and then move to a high threat, high deprivation situation (upper right quadrant) if a parent is deported (Lopez, 2019; Patler and Laster Pirtle, 2018). In our model, the level of threat and deprivation experienced and perceived by the child is dependent on both the child’s macrosystem (e. g., immigration policies and national anti-immigrant rhetoric) and the child’s ontogenic ecology, such as their awareness of immigration policies. Infants may be relatively unaware of their parents’ or own legal status, and hence, their or their parents’ vulnerability, but they are affected through the impact that status has on their parents’ vulnerability to employment exploitation and lack of access to health services. Awareness and understanding of legal status increases through childhood, as cognition and identity develop, and exposure increases to media, peers, conversations with parents, and deportations in their family and community (Suárez Orozco et al., 2011; Valdez et al., in press). Levels of deprivation that the child experiences can range from “low” to “high,” depending on personal exposure to detention, the detention and deportation of a family member (right quadrants, Fig. 1), and the ways in which policies that systematically exclude individuals without citizenship or permanent legal status affect children’s developmental contexts (left quadrants, Fig. 1).

1.3. The macrosystem: racialized immigration policies and enforcement practices

Although ACEs are generally viewed at the level of the individual, macrosystem factors often set the stage for adverse experiences of children of immigrant families. The U.S. has a long history of restrictive immigration policies aimed at Latin Americans, which promote anti-immigrant and racist attitudes toward immigrants and Latinx individuals (e.g., Hart-Cellar Act, 1965; for summary see Massey and Pren, 2012). Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and the passage of the USA PATRIOT Act (2001), immigration was heavily tied to national security (Hagan et al., 2010). Two years later, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) created Immigrations and Custom Enforcement (ICE), whose mission was to detain and deport “criminal and fugitive” noncitizens at the border and within the U.S. interior (Kanstroom, 2007). The Secure Communities Strategy (2009) formed a partnership and database sharing agreement between the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security to deport “criminal aliens.” As a result, deportations rose dramatically, peaking during Obama’s presidency at 434,015 in 2013 (Chisti and Bolter, 2017).

In 2015, Donald Trump ran for office largely on a platform of removing, deterring, and restricting immigrants in the U.S. He and his associates have used unprecedented language to cast Latinx immigrants as animals, criminals, and threats to U.S. values, ways of life, and security. The Trump administration has increased the use of private prisons to detain immigrants; broadened priorities for arrests without regard for parental status; restarted worksite raids; empowered county jail officers with immigration enforcement powers; and attempted to rescind the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Program (Pierce, 2019). On February 24, 2020, the Administration redefined the public charge rule to include use of at least one government benefit, forcing immigrant families seeking legal permanent residence to decide between important government benefits and regularizing their status (Perriera et al., 2018). These policies and rhetoric have created a climate of fear and a “violence of uncertainty”: shifting policies intentionally create systemic insecurity by constantly changing and targeting what matters most to people—family (Grace et al., 2018, p. 904).

We frame ACEs within racialized immigration policies and enforcement practices (see upper box Fig. 1), which affect the health of Latinxs, regardless of their citizenship status. As part of the racialization of immigration policy enforcement, being an immigrant, being Latinx, and being “illegal” (i.e. having unauthorized legal status) have been conflated (Abrego et al., 2017; De Genova, 2002; Menjívar and Kanstroom, 2014). Thus, members of the public may mistrust or mistreat, and officials may erroneously stop citizen Latinxs, believing they are unauthorized because they “appear” to be Latinx (Castañeda, 2019; Menjívar, 2018; Romero, 2006), with individuals with darker skin color at greater risk of being policed (Romero, 2006; Gómez Cervantes, 2019). Authorities’ distrust in Latinx communities causes Latinxs to exercise caution in their daily lives, regardless of their citizenship status (Pedraza et al., 2017). The chronic stress Latinxs experience as a result of racialized immigration policies results in allostatic load—a “wear and tear” on the body—known to have short-and long-term negative physical and mental health effects (McEwen and Stellar, 1993; Vargas et al., 2017).

Mexicans and Central Americans account for 91% of immigrant removals (Rosenblum and McCabe, 2014), and raids frequently target Latinx-dense or Spanish-speaking communities or employment sites (Li, 2019; Perez, 2011). Latinx children and their families are likely to experience adversity in the form of threat (e.g., being stopped by police) and deprivation (e.g., restricting activities and mobility) in ways that affect health, regardless of their citizenship status. As illustrated in Fig. 1, racialized immigration policies—and the ensuing anti-immigrant climate they create—are ongoing contexts that affect children and family members’ legal statuses and lead to immigration-related ACEs.

1.4. Child and family legal status

In addition to naturalized citizenship, which confers the same rights and access as native-born citizens (except for the eligibility to be president or vice president), the immigrant population is classified under four general legally-defined statuses in the U.S. that determine individuals’ access to economic, health, housing, education and civic opportunities: permanent, temporary, discretionary, and undocumented (Waters and Gerstein-Pineau, 2015). These statuses comprise a continuum of vulnerability to immigration policies (McConnell et al., 2020). Permanent status includes lawful permanent residents, refugees, and asylees, and affords the most protections and benefits. Individuals with lawful permanent residence (e.g., having a “green card”) are able to work lawfully, qualify for governmental services, and can join the military. Still, they are not allowed to vote and do not have the right to remain in the U.S. indefinitely, because Congress can place any contingency on permanent status it deems appropriate. Temporary status is held by visa holders who are entitled to limited periods of presence in the U.S., mainly for the purposes of education or employment. Discretionary status is temporary lawful status that is not intended to result in permanent presence, such as DACA and Temporary Protected Status (TPS). Undocumented or “illegal” status, refers to individuals who entered the country without authorization or who entered with an authorized visa but stayed beyond its expiration. Many of these individuals lack any documentation while others have applied for adjusted status, but stay on queue for up to a decade (Waters and Gerstein-Pineau, 2015). Undocumented status, hereafter referred to as unauthorized status, affords few legal protections and confers the constant risk and threat of detention and deportation.

Nearly 20 million, or one out of every four, children in the U.S. have a parent who is an immigrant; most of these children (88%) are U.S. born citizens (Batalova et al., 2020). Approximately 800,000 children under the age of 16 have unauthorized status and 4.1 million citizen-children have a parent with unauthorized status (Capps et al., 2016). There can be meaningful variation in “mixed status” households—family members have different legal statuses. Child and family legal status plays a critical role in the likelihood of experiencing immigration-related ACEs for Latinx youth and thus are included in our model.

1.5. Child developmental stage

The extent to which children are aware of their or their family’s vulnerability due to legal status, depends, in part, on the child’s developmental stage, especially their cognitive development. During times of heightened anti-immigrant rhetoric and enforcement, children may express distress at very early ages. For example, parent and provider reports suggest that children as young as three are aware of the Trump Administration’s anti-immigrant sentiment and the possibility of losing a parent (Cervantes et al., 2018). Children in immigrant families are aware that immigration and law enforcement target Latinx families, and express concern about it in conversations, or in drawings, by age six or seven (Dreby, 2012; Rodriguez Vega, 2018). Children’s awareness of threat due to legal vulnerability will also depend on knowledge of their own legal status. Some pre-adolescents and adolescents experience confusion about how they are seen by others and some youth deny their immigrant identity (Dreby, 2015; Valdez et al., in press). In late adolescence, many youth learn that they have unauthorized status, when they prepare to apply to college and are required to disclose their social security number; other youth learn when they are unable to do things that their siblings with citizenship are able to do, such as obtain a driver’s license, and receive preventive medical and dental care (Castañeda, 2019; Gonzales et al., 2013; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2011).

In our model, immigration policies and enforcement practices, and legal status shape where children and their families fall along the threat-deprivation axes. Child development influences how threat and deprivation are subjectively experienced. We now turn to specific components of children’s proximal and distal environments that influence their vulnerability to threat and deprivation.

2. Immigration-related ACEs

In this section we locate the immigration-related ACEs along the continua of threat and the continua of deprivation. Each of the immigration-related ACEs, associated with deprivation and threat due to marginalization, immigration enforcement and policing, and detention and deportation are on Fig. 1.

2.1. Deprivation and threat due to systemic marginalization of immigrants

2.1.1. Precluded access to resources

Parents and children of unauthorized status are not covered under the Affordable Care Act, and therefore often do not have health insurance. They are less likely to receive WIC during pregnancy and, after child birth, for their infants (Vargas and Pirog, 2016). Unable to qualify for food stamps, they experience higher levels of food insecurity (Brabeck et al., 2016; Gonzalez et al., 2020). Potochnick et al. (2017) found that the 287(g) Program (which authorizes the Director of ICE to enter into agreements with state and local enforcement agencies) was associated with a 10-point increase in food insecurity for Mexican non-citizen households with children. Access to social services (e.g., food stamps, public housing, and subsidized childcare) affects the cognitive development of toddlers in mixed status families (Yoshikawa, 2011) and moderates the relation between parental legal status and academic performance of Latinx immigrant children in grades 2–4 (Brabeck et al., 2016).

Fear, linked to parental immigration status and attempts to protect family members with unauthorized status, often deters parents from seeking social, educational, and health services for eligible children (Castañeda, 2019; Yoshikawa, 2011). Consequently, children miss educational experiences that are vital for their development and mental health. For instance, Latinx children of mothers with unauthorized status are less likely than those with native-born mothers to participate in organized activities (McConnell et al., 2020); this gap is larger for older children, which may result from children’s growing awareness of the implications of family legal status as they mature (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2011). Compared to children of parents with U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident status, children of parents with unauthorized status are less likely to attend public preschool programs or to be enrolled in activities that promote development (Yoshikawa, 2011). Marginalization associated with parental unauthorized status further contributes to children’s developmental delay (Vargas and Benitez, 2019) and school readiness (Crosnoe, 2007). These findings are in line with research on the original DMAP model suggesting that deprivation relates to internalizing and externalizing symptoms through its effects on cognitive (particularly verbal) development (McLaughlin et al., 2016). Mixed-status families, particularly those in states with more restrictive immigration policies, report worse physical health for their children, compared to authorized and U.S. born Latinx parents (Vargas and Ybarra, 2017). Marginalization associated with youth’s own unauthorized status contributes to thwarted economic and educational aspirations, sense of belonging, stigma, vigilance, symptoms of anxiety and depression, grief, and hopelessness (Castañeda, 2019; Gonzales, 2011; Gonzales et al., 2013).

2.1.2. Parental work exploitation

Systemic marginalization of immigrants leads to higher levels of occupational stress among parents of early childhood (Yoshikawa, 2011) and grade school children (Brabeck et al., 2016). This contributes to parents’ psychological distress and limits their availability for children and the resources they can provide. Unstable working conditions and the racialization of immigration may further expose immigrant parents to discrimination, which affects preschool age children’s social emotional development and behavior through its effects on parents’ psychological wellbeing (Gassman Pines, 2015). Such experiences can occur in middle to late childhood as well. Cumulative experiences of discrimination are associated with allostatic load and poor health outcomes (Brondolo et al., 2018). When parents work long hours under harsh conditions and are psychologically affected by discrimination, their capacity to provide stimulating child environments and emotional supports is compromised, resulting in deprivation.

2.1.3. Under-resourced neighborhoods and schools

Although parents with unauthorized status may experience greater levels of systemic marginalization, Latinx immigrant families in general are disproportionately likely to be raising children in under-resourced and disinvested neighborhoods and sending them to under-resourced schools. For example, they are more likely to live in neighborhoods without organizations that promote health, including parks, food resources, physical fitness facilities, health care institutions, and social service organizations (Anderson, 2017). Latinx immigrant youth are more likely to attend racially segregated schools (Reardon et al., 2019) and be taught by mostly White teachers, who may be influenced by deficit attitudes toward Latinx immigrant youth, which may undermine students’ agency within classrooms (Adair et al., 2018). The marginalization of all immigrants—especially immigrants with unauthorized status—is adversely associated with child health and mental health. We argue this happens partly through conditions of deprivation that result from systemic marginalization of immigrants.

2.2. Deprivation and threat due to immigration enforcement and policing

2.2.1. Discrimination and racial profiling

Restrictive immigration policies and national anti-immigrant sentiment have placed Latinx children of immigrants at high risk for experiences of racism such as racial profiling and discrimination by peers and community members. School-age children of immigrants may experience microinsults or microassults (derogatory comments, name calling, and physical threats) and physical attacks (Ayón and Philbin, 2017). U. S. citizen Latinx youths report being stereotyped as gang members; foreign-born Latinx youths report discrimination due to their use of Spanish, limited English proficiency, and wearing traditional attire (Córdova and Cervantes, 2010). Some derogatory comments may convey white supremacy, as when a Latinx child is told, “I’m better than you because I’m white,” by a white classmate (Ayón and Philbin, 2017).

U.S. nativity and speaking English do not protect Latinx children from discrimination (Ayón and Philbin, 2017; Ebert and Ovink, 2014). For instance, native-born Latinx adolescents who perceived discrimination by teachers and other adults in schools had heightened levels of depression (Tummala-Narra and Claudius, 2013) and internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Bennett et al., 2020). Perceived peer and societal discrimination have been associated with depressive symptoms among Latinx youths (Gonzalez et al., 2014; Potochnick and Perreira, 2010).

Discrimination becomes structural or institutional when public policies and practices marginalize entire communities (Mullaly, 2002). Structural discrimination is seen when schools ignore the needs of those they serve—due to either prejudice among educators or lack of resources in systems serving large, segregated Latinx populations (Adair et al., 2018). Proposition 203 in Arizona prioritized learning English (Arizona Secretary of State, 2000), which created structural discrimination by requiring teachers to enforce “no Spanish in the classroom” rules and penalize children for speaking in Spanish with peers (Ayón and Philbin, 2017).

2.2.2. ICE and police collaborations: implications for youths’ perceptions of police

As of June 2020, ICE has 139 active 287(g) agreements with local or state law enforcement agencies in 25 states (ICE, 2020). In Arizona, racial profiling—targeting Latinx individuals because they appear to be of unauthorized status—has been used during community and workplace raids by the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office (Perez, 2011). ICE and police collaborations present threat to children in immigrant families and result in deprivation. Studies indicate that Latinx school age children perceive authority figures, such as law enforcement or police officers, as representing a threat rather than a source of safety (Dreby, 2012; Rodriguez Vega, 2018). Youth fear police officers because they perceive them as taking loved ones away (Dreby, 2012; Rodriguez Vega, 2018; Valdez et al., 2013) and disrespecting their communities during involuntary police-citizen encounters (Solis et al., 2009). Latinx youth report that they are targeted and subjected to aggressive policing because they look “Spanish” and are routinely frisked (Solis et al., 2009).

2.2.3. ICE raids in communities

Immigration raids deter Latinx enrollment in Head Start, (an early childhood education program that promotes school readiness), by 10% (Santillano et al., 2020). Analysis of attendance data in a California school district that serves an immigrant-dense community indicates that between 2013 and 2016, 27 unique incidents involving ICE arrests led to approximately 50,000 days of missed school among all high school students across four years, with strongest effects for Latinx, English language learner, and migrant youth, and students with disabilities (Kirskey, 2019). ICE presence in communities is also associated with missed well-child appointments and under-utilization of health services (Hacker et al., 2013). Thus, ICE raids in immigrant communities may be a source of both threat and deprivation (see Fig. 1).

2.2.4. Threat of deportation

During times of heightened immigration enforcement, immigrant parents and their children report constantly worrying about whether a family member will be deported, or when the next raid will occur (Ayón and Becerra, 2013; Valdez et al., 2013). This uncertainty shapes the daily activities and routines of children (Cardoso et al., 2018; Salas et al., 2013), with families limiting time spent outside of the home in attempts to protect themselves and avoid family fragmentation; consequently, they become more socially isolated (Ayón, 2017a; Salas et al., 2013; Valdez et al., in press). Also, in mixed status families, siblings with unauthorized status have been found to spend more time inside the home (Dreby, 2015); siblings with authorized status may restrict their own travel and educational opportunities to stay near their family members with unauthorized status (Castañeda, 2019). Generalized threat affects mental health directly (creates anxiety and fear) and indirectly through its influence on behavior.

Recent studies demonstrate the adverse impact of enforcement threat on children in immigrant families. A cohort study of 397 U.S.-citizen Latinx adolescent children of immigrant parents reported that the threat to family preservation associated with restrictive immigration policies was associated with adolescents’ anxiety levels, sleep problems, and blood pressure in 2016, after the presidential election (Eskenazi et al., 2019). Nearly half of adolescent participants reported worrying at least sometimes about the personal consequences of the restrictive immigration policies and family separation because of deportation (upper right quadrant, Fig. 1). Among male adolescents, degree of worry in the first year after the 2016 presidential election was associated with lower mean arterial pressure and systolic blood pressure, possibly indicating “a physiologic desensitization in males in response to chronic stress” (Eskenazi et al., 2019, p. 749). Household fear of deportation has also been linked to elevated levels of salivary proinflammatory cytokines in children and parents, which is associated with oral inflammation and increased risk of chronic diseases like cardiovascular disease and periodontitis (Martinez et al., 2018). These findings add to a larger body of research demonstrating that immigration policies targeting parents of unauthorized status affect the health of U.S. born Latinx youth in substantial, negative ways (Landale et al., 2015; Perriera et al., 2018; Vargas et al., 2017). Among undocumented youth, who also face threat of deportation, risk for anxiety and depression is higher than for their U. S. citizen counterparts (Gonzales et al., 2013; Potochnick and Perreira, 2010). Thus, children and youth perceiving considerable (“high”) threat to their parents or to themselves due to restrictive immigration policies and heightened enforcement experience significant psychological distress and potentially adverse physiological outcomes.

2.3. Deprivation and threat due to detention and deportation

2.3.1. Detention and deportation of a parent/caregiver

In our model, the highest level of deprivation and threat (upper right quadrant, Fig. 1) exists for children who experience detention or deportation, followed by experiencing the extended detention or deportation of a parent or caregiver. From the perspective of attachment theory (Bowlby, 1988), children rely on the stability and responsiveness of primary caregivers to deal with changes in their environment in healthy and resilient ways. Separating children from their primary caregiver, via detention or deportation, threatens the parent-child bond, and deprives children from the safety, stability and responsiveness they need to deal with such threat (Shonkoff, 2019). Of note, the younger the child at the time of separation, the less matured their physiological and psychological self-regulating capacities, the more disruption they may experience (Juang et al., 2018; Shonkoff, 2019). Researchers have found that even school-aged children separated from parents due to detention or deportation undergo a heightened risk for emotional and behavioral problems, including high levels of behavioral dysregulation at home and at school (Brabeck et al., 2014; Rojas-Flores et al., 2017; Shonkoff, 2019), psychological distress and symptoms of depression and anxiety (Allen et al., 2015; Rojas-Flores et al., 2017; Zayas et al., 2015), and symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD; Rojas-Flores et al., 2017). When compared to children of parents with unauthorized status who did not have contact with immigration enforcement and parents with legal residency, school-age children of detained/deported parents exhibited greater anxiety and depression symptoms over time (Rojas--Flores et al., 2020).

According to the family reorganization perspectives (Hetherington, 1992), in the aftermath of parental detention or deportation, the interdependent family subsystems (e.g., parent-child; marital; sibling) are thrown into a disequilibrium, altering overall family functioning and stability. Abrupt and forced family separations often lead to disruptions in parenting in terms of quality and quantity of parental input, child supervision, and home daily routines, weakened parent-child bonds (Dreby, 2012), and re-organization of traditional household authorities (Suarez-Orozco et al., 2011).

2.3.2. Economic insecurity due to breadwinner being deported

Deportation of a parent who is a financial provider is often associated with immediate and long-term food (Potochnik et al., 2017), housing (Rugh and Hall, 2016), and economic instability. These deprivations can result in short- and long-term difficulties, ranging from disruption in child care, to abrupt school and neighborhood relocations (Dreby, 2012, 2015). Families that experience detention or deportation of a breadwinner report higher rates of stressors—incurring debt, undergoing a substantial decrease in income, and having a spouse lose employment—compared to families with no contact with ICE and families with permanent legal status (Lopez, 2019; Rojas-Flores et al., 2020). Vargas and colleagues (2018) have named the accumulation of adversity that results after detention and deportation a “stress proliferation” phenomenon.

2.3.3. Detention and deportation of a relative or community member

Family member detention or deportation was associated with higher odds of suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and externalizing symptoms among Latinx adolescents (Roche and White, 2020). Youth who experience the immigration-related arrest of a family member are at greater risk for depressive symptoms, with depressive symptoms magnified among youth who perceive that both of their parents have undocumented legal status (Giano et al., 2020). Quantitative studies with Latinx populations of various legal statuses (Vargas et al., 2018) and Latinx U.S. citizens (Pinedo and Valdez, in press) indicate that knowing a person who has been deported or detained increases the likelihood of an individual experiencing mental health problems. The effect is intensified as the number of persons known to have been deported or detained increases (Vargas et al., 2018). For example, Pinedo and Valdez (in press) found the detention or deportation of a friend was associated with anxiety and depression, and detention of a co-worker or known community member was associated with depression. Although these studies were conducted with adults, they suggest that children may similarly experience distress with the detention of a relative, friend, or community member, whether they experience it directly or indirectly through the adults in their lives (See Fig. 1).

2.4. Frequency and severity of immigration-related ACEs impacts developmental outcomes

As reviewed here, children of immigrants may endure numerous conditions and events that are stressful and marked by threat and deprivation, which can lead to trauma-related distress. Trauma research suggests that some ACEs are synergistic in nature, meaning that their combined effect is greater than the sum of their individual effects (Putnam et al., 2013). For example, for Latinx children, the loss of a parent to detention or deportation, may be experienced as a traumatic event, which is synergistic with being male and poor (Putnam et al., 2013). The influence of trauma exposure over time can be compounded by other events. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Latinx immigrant communities, for example, is expected to compound the effects of immigration threat and deprivation and have long-lasting mental health consequences for children in low-income, immigrant families (Garcini et al., 2020; Gonzalez et al., 2020). As with other models of adversity, children’s short and long-term developmental outcomes will depend on the timing, frequency, and severity of immigration-related ACES. Developmentally-informed principles of trauma-informed care (for review see Ko et al., 2008) are the best standard of care for these children.

3. Moving forward: screening for immigration-related ACEs

Screening for ACEs in children of immigrant families should include indicators of the threat and deprivation experiences associated with immigration policies and enforcement practices included in Fig. 1. Consistent with our model of threat and deprivation, Flores and Salazar (2017; p. 2) recommend the following experiences be integrated into traditional ACEs measures: (1) ICE arrests or deportations of parents or guardians, (2) being a victim of, or witnessing, ICE arrests or raids, (3) parent or guardian separation because of migration, and (4) experiencing anti-immigrant discrimination. Our model points to additional factors to be screened, such as children’s direct experiences of detention or deportation; prolonged food, housing, and economic insecurity due the loss of a breadwinner; under-resourced neighborhoods and schools; parental work exploitation; and precluded access to resources. These experiences should be explored to better understand the family’s context, mental health burden, and resilience, and to provide appropriate resources and interventions.

To assess for the impact of immigration-related threat on the well-being of children and their immigrant families, measurement tools are being developed to capture an array of immigration-related experiences, such as the Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES; Ayón, 2017b). The PIPES′ 24 items measure discrimination, social isolation, threat to family, and children’s vulnerability. The scale was designed for parents, and has been used with adolescents with modifications (Eskenazi et al., 2019). The Hispanic Stress Inventory (Cervantes et al., 1991) has also been used to assess immigration stressors. Best practices for screening in professional practice also apply to research measuring immigration-related ACEs, as described below.

3.1. Ethics of screening and assessment of immigration-related ACEs

Providers and researchers who screen for immigration-related experiences as part of an ACEs framework should consider potential risks and unintended consequences associated with assessment of ACEs (Finkelhor, 2018; Murphey and Bartlett, 2019), and immigration-related ACEs in particular, and take necessary steps to protect their clients and research participants from potential harm. The contributions of the sociopolitical environment, specifically the psychological violence stemming from chronic threat and deprivation for children in immigrant families, should be incorporated into assessments and interventions. Trauma-informed services for children of immigrants should be widely implemented across systems of care, including early care and school settings, healthcare, and community-based-systems of care (Ko et al., 2008).

3.1.1. Risks and safeguards of screening and assessment

There are risks to confidentiality and burden associated with screening for immigration-related adverse experiences, mainly because these experiences are linked to legal status. First, providers and researchers should be aware that even when mixed-status families desire a safe space to talk about their immigration-related experiences, they may not fully understand the limits of confidentiality. These families should be aware that professionals and researchers are not required to report legal status to ICE (Walsdorf et al., 2019). However, they would be required to report potential allegations of abuse or other safety concerns (i.e., suicidality, harm to others) to Child Protective Services that may bring attention to their legal status. There have been cases across the U. S. of medical staff reporting mixed-status families to ICE, prompting many families to entirely avoid or delay clinic or hospital visits (Grace et al., 2018). Professionals should disclose to families their stance on ICE arrests in healthcare settings, validate families’ uncertainty and fears, and encourage families to ask questions about how their healthcare setting uses families’ information about immigration status (Chung et al., 2008).

Second, to avoid breach of confidentiality, providers and researchers should understand that for families with unauthorized or mixed-status, concealing their legal status is central to the preservation of the family. Thus, providers and researchers should refrain from asking families about their legal status early in the relationship (Walsdorf et al., 2019). If children or parents disclose their legal status, providers and researchers should use caution not to record it in their records.

Third, providers and researchers should inquire from parents what children know about their own, or their family’s, legal status prior to discussing it openly with the child. Many children do not learn about their or their family’s legal status until they reach emerging adulthood (Castañeda, 2019; Gonzales, 2011).

Fourth, providers should offer relevant interventions or strategies to support children and families after screening for immigration-related adverse experiences. Inquiring about traumatic exposures without offering appropriate or accessible support, may be harmful because of the potential for retraumatization (Finkelhor, 2018; Murphey and Bartlett, 2019). Trauma may manifest in unique ways for these families because the stressor or exposure is structural, cumulative, and persistent. Interventions intended to reduce symptoms only, without proper attention to structural and systemic injustices, are likely to fail in improving the lives of families (Finkelhor, 2018). Providers should be prepared to address food and housing instability, interpersonal losses and grief, irregular school attendance, and access to vital social services, among others. Providers should know how to assist parents with legal contingency plans for their children in case of arrest and deportation. It is key that providers become involved in local legal services and immigrant rights organizations.

Finally, state or federally funded programs are subject to public record requests. As such, programs may have to release aggregated data indicating that individuals with undocumented status are receiving services, which might jeopardize program funding or weaken immigrant community trust in such programs. Data collection that reveals immigrant status, even when unidentifiable at the individual level, should not be undertaken by public agencies without complete consideration of such potential consequences for the program and community.

3.2. Expanded ACEs model limitations and future research

Research on the impact of immigration enforcement on children is nascent. A robust body of literature indicates the timing of exposure to adversity, especially during early critical periods, matters for health and mental health outcomes (Schalinski et al., 2016; Shonkoff et al., 2012; Steine et al., 2020). As longitudinal research on the impact of restrictive immigration policies and enforcement practices on child health and mental health is completed, the adapted dimensional model we propose here can be refined to better reflect children’s lived experiences. Prospective research linking immigration related adverse experiences in childhood to adult health, studies testing the cumulative nature of the impacts of immigration-related adverse experiences on adult health outcomes, and the demonstration of a dose-response relationship to adult health outcomes are needed to inform this framework.

4. Conclusion

Our framework answers the call to consider structural factors that contribute to Latinx health inequities (Cerdena et al., 2021). Expanding the ACEs framework to include threat and deprivation associated with racialized immigration policies and immigration enforcement will 1) allow practitioners to more accurately assess health disparities and treat health conditions caused by these policies and practices; 2) encourage researchers to explore how ACEs specific to the immigrant experience differentially impact children’s development; and 3) assist advocates and practitioners to press for healthier immigration policies that support the development of children in immigrant families.

References

- Abrego L, Coleman M, Martínez DE, Menjívar C, Slack J, 2017. Making immigrants into criminals: legal processes of criminalization in the post-IIRIRA era. J. Migrat. Hum. Secur. 5 (3), 694–715. [Google Scholar]

- Adair JK, Colegrove KS, McManus ME, 2018. Troubling messages: agency and learning in the early schooling experiences of children of Latina/o immigrants. Teach. Coll. Rec. 120 (6), 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Allen B, Cisneros EM, Tellez A, 2015. The children left behind: the impact of parental deportation on mental health. J. Child Fam. Stud. 24, 386–392. 10.1007/s10826-013-9848-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KA, 2017. Racial residential segregation and the distribution of health-related organizations in urban neighborhoods. Soc. Probl. 64 (2), 256–276. 10.1093/socpro/spw058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arizona Secretary of State, 2000. Proposition 203. Retrieved from. http://www.azsos.gov/election/2000/info/pubPamphlet/english/prop203.htm.

- Ayón C, 2017a. Vivimos en jaula de oro: the impact of state level legislation on immigrant Latino families. J. Immigrat. Refugee Stud. 16 (4), 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, 2017b. Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale: development and validation of a scale on the impact of state-level immigration policies on Latino immigrant families. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 39 (1), 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, Becerra D, 2013. Latino immigrant families under siege: the impact of SB1070, discrimination, and economic crisis. Adv. Soc. Work, Special Issue: Latinos/Latinas in the U.S. 14 (1), 206–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, Philbin SP, 2017. “Tú no eres de aquí:” Latino Children’s experiences of institutional and interpersonal discrimination, and microaggressions. Soc. Work. Res. 41 (1), 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Barajas-Gonzalez RG, Ayón C, Torres F, 2018. Applying a community violence framework to understand the impact of immigration enforcement threat on Latino children. Soc. Pol. Rep. 31 (3), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Batalova J, Blizzard B, Colter J, 2020. Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. Retrieved from Migration Policy Institute website: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states#Children.

- Bennett M, Roche KM, Huebner DM, Lambert SF, 2020. School discrimination and changes in Latinx adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms. J. Youth Adolesc. 10.1007/s10964-020-01256-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J, 1988. A Secure Base: Parent-child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brabeck KM, Lykes MB, Hunter C, 2014. The psychosocial impact of detention and deportation on U.S. Migrant children and families. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 84 (5), 496–505. 10.1037/ort0000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabeck KM, Sibley E, Taubin P, Murcia A, 2016. The influence of immigrant parent legal status on U.S.-born children’s academic abilities: the moderating effects of social service use. Appl. Dev. Sci. 20, 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Blair IV, Kaur A, 2018. Biopsychosocial mechanisms linking discrimination to health: a focus on social cognition. In: Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG (Eds.), Oxford Library of Psychology. The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health, pp. 219–240. [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, Fix M, Zong J, 2016, January. A Profile of U.S. Children with Unauthorized Immigrant Parents. Retrieved from Migration Policy Institute website: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/profile-us-children-unauthorized-immigrant-parents.

- Cardoso JB, Scott JL, Faulkner M, Lane L, 2018. Parenting in the context of deportation risk. J. Marriage Fam. 80, 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H, 2019. Borders of Belonging: Struggle and Solidarity in Mixed-Status Immigrant Families. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdeña JP, Rivera LM, Spak JM, 2021. Intergenerational trauma in Latinxs: a scoping review. Soc. Sci. Med. 270, 113662. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Salgado de Snyder N, 1991. The Hispanic Stress Inventory: a culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychol. Assess.: J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 3 (3), 438. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes W, Ullrich R, Matthews H, 2018. Our Children’s Fear: Immigration Policy’s Effects on Young Children. Center for Law and Social Policy, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Chisti Pierce, Bolter, 2017. The Obama Record on Deportations: Deporter in Chief or Not? Retrieved from Migration Policy Institute website: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/obama-record-deportations-deporter-chief-or-not.

- Chung RC, Bemak F, Oritz DP, Sandoval-Perez PA, 2008. Promoting the mental health of immigrants: a multicultural/social justice perspective. J. Counsel. Dev. 86, 310–317. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M, 1993. Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: consequences for children’s development. Psychiatr. Interpers. Biol. Process. 56, 96–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdova D Jr., Cervantes RC, 2010. Intergroup and within-group perceived discrimination among U.S.-born and foreign-born Latino youth. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 32, 259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, 2007. Early child care and the school readiness of children from Mexican immigrant families. Int. Migrat. Rev. 41, 152–181. [Google Scholar]

- De Genova N, 2002. Migrant [illegality] and deportability in everyday life. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 31, 419–447. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby J, 2012. The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. J. Marriage Fam. 74, 829–845. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00989.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dreby J, 2015. Everyday Illegal: when Policies Undermine Immigrant Families. University of California Press, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert K, Ovink SM, 2014. Anti-immigrant ordinances and discrimination in new and established destinations. Am. Behav. Sci. 58, 1784–1804. [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Fahey CA, Kogut K, et al. , 2019. Association of perceived immigration policy vulnerability with mental and physical health among US-born Latino adolescents in California. JAMA Pediatrics 173 (8), 744–753. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. , 1998. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 14, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, 2018. Screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): cautions and suggestions. Child Abuse Negl. 85, 174–179. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores G, Salazar JC, 2017. Immigrant Latino children and the limits of questionnaires in capturing adverse childhood events. Pediatrics 140 (5), e20172842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia SJ, 2018. Living a deportation threat: anticipatory stressors confronted by undocumented Mexican immigrant women. Race Soc. Probl. 10, 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Garcini LM, Domenech Rodríguez M, Mercado A, Paris M, 2020. A tale of two crises: the compounded effect of COVID-19 and anti-immigration policy in the United States. Psychol. Trauma: Theory, Res. Practice Pol. 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassman-Pines A, 2015. Effects of Mexican immigrant parents’ daily workplace discrimination on child behavior and functioning. Child Dev. 86 (4), 1175–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getrich C, 2013. “Too Bad I’m Not an Obvious Citizen”: The effects of racialized US immigration enforcement practices on second-generation Mexican youth. Latino Stud. 11, 462–482. 10.1057/lst.2013.28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giano Z, Anderson M, Shreffler KM, Cox RB, Merten MJ, Gallus KL, 2020. Immigration-related arrest, parental documentation status, and depressive symptoms among early adolescent Latinos. Cult. Divers Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 26 (3), 318–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golash-Boza T, Hondagneu-Sotelo P, 2013. Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: a gendered racial removal program. Lat. Stud. 11, 271–292. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Cervantes A, 2019. ‘Looking Mexican’: indigenous and non-indigenous latina/o immigrants and the racialization of illegality in the midwest. Soc. Probl. 10.1093/socpro/spz048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RG, 2011. Learning to be illegal: undocumented youth and shifting legal contexts in the transition to adulthood. Am. Socio. Rev. 76, 602–619. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RG, Suárez-Orozco C, Dedios-Sanguineti MC, 2013. No place to belong: contextualizing concepts of mental health among undocumented immigrant youth in the United States. Am. Behav. Sci. 57, 1174–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez LM, Stein GL, Kiang L, Cupito AM, 2014. The impact of discrimination and support on developmental competencies in Latino adolescents. J Latina Psychol. 2 (2), 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez D, Karpman M, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S, 2020. Hispanic Adults in Families with Noncitizens Disproportionately Feel the Economic Fallout from COVID 19. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102170/hispanicadults-in-families-with-noncitizens-disproportionately-feel-theeconomic-fallout-from-covid-19_2.pdf.

- Grace BL, Bais R, Roth BJ, 2018. The violence of uncertainty—undermining immigrant and refugee health. N. Engl. J. Med. 379 (10), 904–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbas LE, Zayas LH, 2017. Exploring the effects ofU.S.immigration enforcement on the well-being of citizen children in Mexican immigrant families. RSF: Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 3 (4), 53–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker K, Chu J, Arsenault L, Marlin RP, 2013. Provider’s perspectives on the impact of immigration and customs enforcement (ICE) activity on immigrant health. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 23 (2), 651–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Castro B, Rodriguez N, 2010. The effects of U.S. deportation policies on immigrant families and communities: cross-border perspectives. N. C. Law Rev. 88, 1799–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, 1992. I. Coping with marital transitions: a family systems perspective. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 57 (Serial No.227), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Horner P, Sanders L, Martinez R, Doering-White J, Lopez W, Delva J, 2014. “I put a mask on” the human side of deportation effects on Latino youth. J. Soc. Welfare Hum. Rights 2 (2), 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Juang LP, Simpson JA, Lee RM, Schachner MK, et al. , 2018. Using attachment and relational perspectives to understand adaptation and resilience among immigrant and refugee youth. Am. Psychol. 73 (6), 797–811. 10.1037/amp0000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanstroom D, 2007. Deportation Nation: Outsiders in American History. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Kirskey JJ, 2019. Immigration enforcement and absenteeism in a California school district. UC Center Sacramento Pol. Brief 3 (9). https://uccs.ucdavis.edu/events/event-files-and-images/Kirksey_Policy_Brief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ko SJ, Ford JD, Kassam-Adams N, Berkowitz SJ, Wilson C, Wong M, et al. , 2008. Creating trauma-informed systems: child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 39, 396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Hardie JH, Oropesa RS, Hillemeier MM, 2015. Behavioral functioning among Mexican-origin children: does parental legal status matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 56 (1), 2–18. 10.1177/0022146514567896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez WD, 2019. Separated: Family and Community in the Aftermath of an Immigration Raid. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Makariev DW, Shaver PR, 2010. Attachment, parental incarceration, and possibilities for intervention. Am. J. Bioeth. 12 (4), 311–331. 10.1080/14751790903416939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez AD, Ruelas L, Granger DA, 2018. Household fear of deportation in relation to chronic stressors and salivary proinflammatory cytokines in Mexican-origin families post-SB 1070. SSM - Popul. Health 5, 188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Pren K, 2012. Origins of the new Latino underclass. Race Soc. Probl. 4 (1), 5–17. 10.1007/s12552-012-9066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell ED, White RMB, Ettekal EV, 2020. Participation in organized activities among Mexican and other Latino youth in Los Angeles: variation by mothers’ documentation status and youth’s age. Appl. Dev. Sci. 24, 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Stellar E, 1993. Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 153 (18), 2093–2101. 10.1001/archinte.153.18.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, 2016. Beyond cumulative risk a dimensional approach to childhood adversity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 25 (4), 239–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Lambert HK, 2014. Childhood adversity and neural development: Deprivation and threat as distinct dimensions of early experience. Neurosci. Biobehavior. Rev. 47, 578–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C, 2006. Liminal legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants’ lives in the United States. Am. J. Sociol. 111, 999–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C, Kanstroom D (Eds.), 2014. Constructing Immigrant ‘Illegality’: Critiques, Experiences, and Responses. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C, Simmons WP, Alvord D, Valdez ES, 2018. Immigration enforcement, the racialization of legal status, and perceptions of the police: latinos in Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston, and Phoenix in comparative perspective. Du. Bois Rev.: Soc. Sci. Res. Race 15 (1), 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Mullaly B, 2002. Challenging Oppression: A Critical Social Work Approach. Oxford University Press, Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Ferrington DP, Sekol I, 2012. Children’s antisocial behavior, mental health, drug use, and educational performance after parental incarceration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2, 175–210. 10.1037/a0026407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Murray L, 2010. Parental incarceration, attachment and child psychopathology. Am. J. Bioeth. 12, 289–309. 10.1080/14751790903416889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphey D, Bartlett JD, 2019. Childhood adversity screenings are just one part of an effective policy response to childhood trauma. Retrieved from Child Trends website: https://www.childtrends.org/publications/childhood-adversity-screenings-are-just-one-part-of-an-effective-policy-response-to-childhood-trauma.

- Oh DL, Jerman P, Boparai SK, Koita K, Briner S, Bucci M, Harris NB, 2018. Review of tools for measuring exposure to adversity in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Health Care 32 (6), 564–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patler C, Laster Pirtle W, 2018. Feb. From undocumented to lawfully present: Do changes to legal status impact psychological wellbeing among latino immigrant young adults? Soc. Sci. Med. 199, 39–48. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza FI, Nichols VC, LeBrón AMW, 2017. Cautious citizenship: the deterring effect of immigration issue: salience on health care use and bureaucratic interactions among LatinxU.S.citizens. J. Health Polit. Pol. Law 42 (5), 925–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez TE, 2011. United States’ Investigation of the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office. U. S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. Retrieved from. http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/spl/documents/mcso_findletter_12-15-11.pdf.

- Perreira K, Yoshikawa H, Oberlader J, 2018. A new threat to immigrants’ health: the public charge rule. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 901–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce S, 2019. Immigration-related Policy Changes in the First Two Years of the Trump Administration. Retrieved from Migration Policy Institute website: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/immigration-policy-changes-two-years-trump-administration.

- Pinedo M, & Valdez CR (in press). Immigration enforcement policies and the mental health of US-citizen Latinxs: findings from a comparative analysis. Am. J. Community Psychol.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick SR, Perreira KM, 2010. Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 198, 470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick S, Chen J, Perreira K, 2017. Local-level immigration enforcement and food insecurity risk among Hispanic immigrant families with children: national-level evidence. J. Immigr. Minority Health 19, 1042–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provine DM, 2013. Institutional racism in enforcing immigration law. Norteamérica 3, 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam K, Harris W, Putnam F, 2013. Synergistic childhood adversities and complex adult psychopathology. J. Trauma Stress 26 (4), 435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon SF, Weathers ES, Fahle EM, Jang H, Kalogrides D, 2019. Is Separate Still Unequal? New Evidence on School Segregation and Racial Academic Achievement Gaps (CEPA Working Paper No.19–06). http://cepa.stanford.edu/wp19-06.

- Roche KR, White RMB, Lambert SF, et al. , 2020. Association of family member detention or deportation with Latino or Latina adolescents’ later risks of suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and externalizing problems. JAMA Pediatrics. 10.1001/jamapediatrics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Vega S, 2018. Borders and badges: Arizona’s children confront detention and deportation through art. Lat. Stud. 16, 310–340. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Flores L, Grams-Benitez et al. , Fung J, Hwang Koo J, & Muro K (forthcoming). Latino Citizen Children in the Aftermath of Parental Deportation: Mental Health, Life Events, and Service Utilization across Time.

- Rojas-Flores L, Clements M, Hwang Koo J, London J, 2017. Trauma, psychological distress and parental immigration status: latino citizen-children and the threat of deportation. Psychol. Trauma: Theory, Res. Pract. Pol. 9, 352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero M, 2006. Racial profiling and immigration law enforcement: rounding up of usual suspects in the Latino community. Crit. Sociol. 32 (2/3), 447–473. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum MR, McCabe K, 2014. Deportation and Discretion: Reviewing the Record and Options for Change. Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Rugh J, Hall M, 2016. Deporting the American dream: immigration enforcement and Latino foreclosures. Sociol. Sci. 3, 1077–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Salas LM, Ayón C, Gurrola M, 2013. Estamos traumados: the impact of anti-immigrant sentiment and policies on the mental health of Mexican immigrant families. J. Community Psychol. 41 (8), 1005–1020. 10.1002/jcop.21589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santillano R, Potochnick S, Jenkins J, 2020. Do immigration raids deter Head Start enrollment? AEA Pap. Proc. 110, 419–423. [Google Scholar]

- Schalinski I, Teicher MH, Nischk D, Hinderer E, Müller O, Rockstroh B, 2016. Type and timing of adverse childhood experiences differentially affect severity of PTSD, dissociative and depressive symptoms in adult inpatients. BMC Psychiatr. 16 (1), 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan MA, McLaughlin KA, 2020. Neurodevelopmental mechanisms linking ACEs with psychopathology. In: Adverse Childhood Experiences: Using Evidence to Advance Research, Practice, Policy and Prevention. Academic Press, pp. 265–285. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, 2019, February. Migrant Family Separation Congressional Testimony. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/about/press/migrant-family-separation-congressional-testimony-dr-jack-p-shonkoff/.

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, et al. , 2012. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 129 (1), e232–246. 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis C, Portillos EL, Brunson RK, 2009. Latino youths’ experiences with and perceptions of involuntary police encounters. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 623 (1), 39–51. 10.1177/0002716208330487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steine IM, LeWinn KZ, Lisha N, Tylavsky F, Smith R, Bowman M, Sathyanarayana S, Karr CJ, Smith AK, Kobor M, Bush NR, 2020. Maternal exposure to childhood traumatic events, but not multi-domain psychosocial stressors, predict placental corticotrophin releasing hormone across pregnancy. Soc. Sci. Med. 266, 113461. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Yoshikawa H, Teranishi R, Suárez-Orozco M, 2011. Growing up in the shadows: the developmental implications of unauthorized status. Harv. Educ. Rev. 81, 438–472. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tummala-Narra P, Claudius M, 2013. Perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among immigrant-origin adolescents. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 257–269. 10.1037/a0032960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Us Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2020. Delegation of Immigration Authority Section 287(g) Immigration and Nationality Act. Retrieved from: https://www.ice.gov/287g.

- Valdez CR, Wagner K, & Minero LP (in press). Emotional Reactions and Coping of Mexican Mixed-Status Immigrant Families in Anticipation of the 2016 Presidential Election. Family Process. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez CR, Padilla B, Lewis Valentine J, 2013. Consequences of Arizona’s immigration policy on social capital among Mexican mothers with unauthorized immigration status. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 35 (3), 303–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ED, Benitez VL, 2019. Latino parents’ links to deportees are associated with developmental disorders in their children. J. Community Psychol. 47 (5), 1151–1168. 10.1002/jcop.22178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ED, Juárez CM, Sanchez G, Livaudais M, 2018. Latinos’ connections to immigrants: How knowing a deportee impacts Latino health. J. Ethn. Migrat. Stud. 2971–2988. 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1447365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ED, Pirog MA, 2016. Mixed-status families and WIC uptake: the effects of risk of deportation on program use. Soc. Sci. Q. 97 (3), 555–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ED, Ybarra VD, 2017. U.S. citizen children of unauthorized parents: between state immigration policy and the health of children. J. Immigr. Minority Health 19, 913–920. 10.1007/s10903-016-0463-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ED, Sanchez G, Juárez M, 2017. Fear by association: perceptions of anti-immigrant policy and health outcomes. J. Health Polit. Pol. Law 42 (3), 459–483. 10.1215/03616878-3802940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsdorf A, Escudero Y, Bermúdez JM, 2019. Unauthorized and mixed-status Latinx families: sociopolitical considerations for systemic practice. J. Fam. Psychother. 30 (4), 245–271. 10.1080/08975353.2019.1679607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waters, Mary C, Gerstein-Pineau Marissa (Eds.), 2015. The Integration of Immigrants into American Society. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, 2011. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and Their Young Children. Russel Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Yoon H, Rey GN, 2015. The distress of citizen-children with detained and deported parents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 24 (11), 3213–3223. 10.1007/s10826-015-0124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]