Abstract

There is an extensive body of work documenting the negative socioemotional and academic consequences of perceiving racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence, but little is known about how the larger peer context conditions such effects. Using peer network data from 252 eighth graders (85% Latino, 11% African American, 5% other race/ethnicity), the present study examined the moderating role of cross-ethnic friendships and close friends’ experiences of discrimination in the link between adolescents’ perceptions of discrimination and well-being. Cross-ethnic friendships and friends’ experiences of discrimination generally served a protective role, buffering the negative effects of discrimination on both socioemotional well-being and school outcomes. Overall, results highlight the importance of considering racial/ethnic-related aspects of adolescents’ friendships when studying interpersonal processes closely tied to race/ethnicity.

Friends are a vital component of the fabric of adolescents’ lives. During adolescence, peers become more robust socializing agents, and peer relationships, broadly defined, are more complex as adolescents learn to negotiate dyadic relationships within a much larger social landscape (Brown & Larson, 2009). Overall, the breadth of knowledge around adolescent friendships is expansive, yet the attention placed on friendships in the context of race/ethnicity is minute (Graham, Taylor, & Ho, 2009). The racial/ethnic-related aspects of adolescents’ friendships are likely particularly salient when considering experiences such as racial/ethnic discrimination, a stressor that adolescents of color all too often face. To address this gap in the literature, in the current study we focused on two racial/ethnic-related aspects of adolescents’ friendships—close friends’ experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination and adolescents’ engagement in cross-ethnic friendships. Our goal was to understand how each influenced the links between adolescents’ personal experiences of discrimination and their socioemotional well-being (loneliness and depression) and academics (school engagement and belonging).

Experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination are unfortunately commonplace in the lives of individuals of color (Pascoe & Richman, 2009; Schmitt, Branscombe, Postmes, & Garcia, 2014). During adolescence, race/ethnicity-based mistreatment often occurs in educational spaces and is perpetrated by both peers and adult authority figures (Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000). The consequences of such mistreatment are far-reaching, harming adolescents’ mental and physical health and well-being as well as their performance and engagement in school (Benner & Graham, 2011; Brody et al., 2006; Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers, & Jackson, 2008). The realities of racial/ethnic discrimination across the life course have influenced developmental theories to specifically integrate experiences of discrimination and prejudice into models elucidating the growth and development of children and adolescents of color (Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Spencer, Dupree, & Hartmann, 1997). These models suggest that the pernicious effects of racial/ethnic discrimination can be mitigated, at least in part, by what Garcia Coll et al. (1996) term “promoting” contexts, or proximal environments that support developmental outcomes and prepare students “to deal with the societal demands imposed by … discrimination” (p. 1902). In this study, we focus on adolescent friendships as a potentially promoting context for young people facing discriminatory treatment.

A large literature highlights the buffering nature of positive peer relations for young people facing a variety of life stressors, including peer victimization, family adversity, poor parent–child relationships, and child maltreatment (Bukowski, Motzoi, & Meyer, 2009; Gutman, Sameroff, & Eccles, 2002). Although much more narrow in scope, there is also some evidence that the links between racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being are ameliorated in part by supportive friendships and affiliations with positive peers throughout the life course (Ajrouch, Reisine, Lim, Sohn, & Ismail, 2010; Brody et al., 2006; Grossman & Liang, 2008). Prior findings suggest that general support, however, may play a less prominent protective role in adolescent outcomes than domain-specific social support (Roberts, Nargiso, Gaitonde, Stanton, & Colby, 2015). As such, when investigating adolescents’ experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination, determining whether domain-specific aspects of friendships more directly tied to race/ethnicity—such as the demographic makeup of friendships and the race-related experiences of close friends—play an important protective role is a critical open question.

Cross-ethnic friendships, although somewhat uncommon (Hallinan & Williams, 1989; Hamm, Brown, & Heck, 2005), promote both positive intergroup attitudes and social competence (Hunter & Elias, 1999; Mendoza-Denton & Page-Gould, 2008). Intergroup contact theory (Allport, 1954) posits that contact with those from out-groups (e.g., other race/ethnicities than oneself) can disconfirm held stereotypes and thus facilitate more positive beliefs about out-group members. Pettigrew (1997) suggests that intergroup contact is particularly potent when such contact involves friendships, as these entail more prolonged exposure to an out-group member and a more equal balance of power, all in the context of a close relationship. These theoretical tenets have empirical support, as adolescents with more cross-ethnic friends typically report less vulnerability in terms of both their safety at school and their experiences of peer victimization (Graham, Munniksma, & Juvonen, 2014; Kawabata & Crick, 2011), and for African American and Latino young adults, cross-ethnic friendships with Whites are associated with fewer reports of racial/ethnic discrimination over time (Tropp, Hawi, Van Laar, & Levin, 2012). Cross-ethnic friendships appear to play a protective role as well, mitigating some of the detrimental consequences of race-based rejection sensitivity on psychosomatic complaints (Page-Gould, Mendoza-Denton, & Mendes, 2014).

In addition to the racial/ethnic makeup of adolescents’ close friendships, the experiences within these networks also likely play a role in adolescents’ well-being. Yet to date, no studies have examined the extent to which the pervasiveness of experiences of discrimination within the peer network influences adolescents’ adjustment and their ability to manage discriminatory encounters. High levels of perceived discrimination within the peer network could potentially be a risk factor for youth, as research in both the victimization and discrimination literatures suggest vicarious/witnessed experiences of mistreatment may be detrimental for well-being (Nishina & Juvonen, 2005; Priest et al., 2013; for exception, see Tynes, Giang, Williams, & Thompson, 2008). In contrast, there is also evidence suggesting that comparable experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination to one’s close friends may serve a functional role, ameliorating some of the negative effects of discrimination. Friends who have similar encounters with discriminatory treatment can provide each other with a sounding board and emotional support to help cope with and make meaning of experiences of discrimination (Graham, Bellmore, Nishina, & Juvonen, 2009; Tatum, 1997). Along parallel lines, knowing that close others have also experienced racial/ethnic discrimination may spur cognitions characterized by external attributions—that is, beliefs that the source of the mistreatment is due to external causes rather than something internal to the individual. Such external attributions can serve a protective role when encountering mistreatment (Graham, Bellmore, et al. 2009; Graham, Taylor, et al. 2009).

In this study, we examined how adolescents’ experiences of racial discrimination and racial/ethnic-related aspects of their friendships (i.e., presence of cross-ethnic friendships, close friends’ reports of discrimination) were linked individually and conjointly to socioemotional well-being and school engagement and belonging. We hypothesized that cross-ethnic friendships would serve a protective role, chipping away at some of the negative effects of personally experienced discrimination. Similarly, we expected that higher levels of discrimination within the peer network would attenuate the effects of personally experienced discrimination. We investigated both peer- and educator-perpetrated discrimination, and based on prior research identifying source-specific variation in effects on developmental competencies (Benner & Graham, 2013; Cogburn, Chavous, & Griffin, 2011), we hypothesized stronger effects of peer-perpetrated discrimination for socioemotional outcomes (i.e., loneliness, depression) and stronger links between educator-perpetrated discrimination and academic functioning (i.e., engagement, school belonging).

Data are drawn from a sample of predominantly Latino middle school students, and our focus on early adolescence was purposeful. It is at this time in the developmental life course that individuals begin to explore the meaning of race/ethnicity for their identity (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Early adolescence is also when young people begin to understand and articulate the implications of race for individuals’ daily lives, and at this stage of development, they begin to consider how others view their racial/ethnic group (Quintana, 2008). Moreover, early adolescents also have the emerging cognitive abilities (i.e., understanding of others’ cognitions, classification skills, construction of social comparisons, moral reasoning) to recognize both overt and more subtle forms of race-based mistreatment (Brown & Bigler, 2005; Verkuyten, Kinket, & van der Wielen, 1997). Finally, early adolescence is also the time when the peer group and friend support become particularly salient (Brown & Larson, 2009). As such, early adolescence is an ideal time to examine relations among our central constructs of interest.

Method

Participants

Survey and peer network data were collected from 252 eighth-grade students at two middle schools in the south in the Spring 2013 semester as part of the Schools, Peers, and Adolescent Development Project. The sample includes 50% girls and is 85% Latino, 11% African American, and 5% other (i.e., biracial, Asian American, White). A majority of participants’ parents did not graduate high school (56%). Many participants (68%) were born in the United States; most of their fathers (73%) and mothers (70%) were foreign born. The student bodies at the two participating schools mirrored the sample characteristics; they were predominantly Latino (86%) and socioeconomically disadvantaged (97% receiving free/reduced-price lunch). The teaching staffs were similarly racially/ethnically diverse (50% Latino, 9% African American, 33% White, 9% Asian American at School 1; 19% Latino, 19% African American, 56% White, 6% Asian American at School 2).

Procedures

Students with parent consent and student assent completed the survey and peer nominations during a noncore content course. We collected data from between 62% and 69% of the eighth-grade students in each participating school; this response rate met the criteria of creating a valid peer network (lower threshold of 60%–70%; Cillessen, 2009). For peer nominations, students were asked to write the names of their five closest friends (same-sex or opposite-sex friends) in their grade level and designate whether each friend was of the same or different race/ethnicity as themselves. Students then wrote the roster ID number of each friend. Rosters included ID numbers for students who had parent consent and student assent for study participation; students used 999 for any friends not on the roster. Most students nominated five friends (M = 4.80, SD = 0.76); an average of 2.95 (SD = 1.26) of these were study participants. Almost all students (97%) nominated at least one study participant as a close friend.

Study materials were available in English and Spanish. To ensure comparability, materials were translated into Spanish and then back translated into English. Inconsistencies were resolved by two bilingual research team members with careful consideration of items’ culturally appropriate meaning. The majority of students completed surveys in English (92%). Participants received a small compensation ($15) for participation.

Measures

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for study measures appear in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer discrimination (S) | |||||||||||

| Educator discrimination (S) | .20** | ||||||||||

| Cross-ethnic friendship | .16* | .05 | |||||||||

| Peer discrimination (F) | .07 | .07 | .15* | ||||||||

| Educator discrimination (F) | .02 | −.01 | .03 | .15* | |||||||

| Peer discrimination (same-ethnic F) | .15* | .18** | .04 | .87*** | .10 | ||||||

| Educator discrimination (same-ethnic F) | .00 | .03 | .00 | .12 | .96*** | .09 | |||||

| Loneliness | .16* | .04 | −.03 | −.09 | −.04 | .01 | −.05 | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | .11 | −.01 | −.02 | −.05 | −.03 | .03 | .00 | .60*** | |||

| School engagement | −.13* | −.23*** | −.03 | .08 | −.09 | .00 | −.05 | −.27*** | −.20** | ||

| School belonging | −.10 | −.17** | .03 | .11 | −.04 | .03 | −.06 | −.41*** | −.36*** | .28*** | |

| M | 1.24 | 1.09 | .49 | 1.22 | 1.11 | 1.18 | 1.09 | 1.77 | .25 | 3.86 | 4.00 |

| SD | .51 | .33 | .50 | .31 | .30 | .28 | .31 | .55 | .28 | .63 | .73 |

| N | 246 | 246 | 247 | 239 | 239 | 213 | 213 | 247 | 247 | 247 | 247 |

Note. S = sample participant; F = friends of participant.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Students’ Perceptions of Discrimination

Perceptions of racial/ethnic discrimination were assessed using items from the Adolescent Discrimination Distress Index (Fisher et al., 2000), which has been used extensively with middle school students (e.g., Benner & Graham, 2011; Grossman & Liang, 2008). Students rated the frequency of discrimination by educators (two items; e.g., given a lower grade than deserved) and by peers (three items; e.g., other kids exclude you from their activities) because of their race/ethnicity over the past 6 months, using a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (a whole lot). Higher mean scores indicated greater perceived discrimination perpetrated by educators (r = .30) and peers (α = .68).

Cross-Ethnic Friendships

Students reported whether each nominated friend was of the same or different race/ethnicity as themselves. We identified students who did not have any cross-ethnic friendships (0) versus students who had one or more cross-ethnic friends (1).

Friends’ Perceptions of Racial/Ethnic Discrimination

Friends’ perceptions of discrimination were constructed using peer nomination data. We matched each participant’s nominations of their five closest friends with their friends’ reports of discrimination experiences. We then averaged racial/ethnic discrimination ratings across all the participant’s close friends, regardless of whether they were same- or cross-ethnic friends. Friends’ perceptions of discrimination were calculated separately for educator and peer perpetrators.

Well-Being

Adolescents rated 13 items about their feelings of loneliness (e.g., “I have nobody to talk to”; Asher & Wheeler, 1985). Items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (true all the time), with higher mean scores indicating greater loneliness (α = .80). Depressive symptoms were assessed by the 10-item Children’s Depressive Inventory (Kovacs, 1992). Using a 3-point scale, adolescents rated their depressed feelings in the past 2 weeks (e.g., “I am sad”); higher mean scores denoted more depressive symptoms (α = .84). School engagement was measured by a five-item scale (e.g., “I pay attention in class”) from the Perceived Social Norms for Schoolwork and Achievement (Witkow, 2006). School belonging was assessed by a five-item subscale (e.g., “I feel like I am a part of this school”) from Gottfredson’s (1984) Effective School Battery. Both the school engagement and belonging items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (true all the time); higher mean scores denoted stronger engagement (α = .75) and belonging (α = .79).

Covariates

Student gender and race/ethnicity were collected from school records. Each student was identified as one of the following racial/ethnic categories: Latino, African American, and other race/ethnicities (i.e., biracial, Asian American, White). Latino was defined by the school district as “a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race.” Based on student reports, we identified generational status as first, second, or third generation or later. Students reported their parents’ highest education on a 4-point scale from 1 (less than high school) to 4 (4-year college graduates or higher). We also controlled for survey language and school attended.

Analysis Plan

We used regression analyses in Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) to examine the independent and conjoint influences of students’ experiences of discrimination, cross-ethnic friendships, and their friends’ experiences of discrimination for students’ adjustment. We tested peer- and teacher-perpetrated racial/ethnic discrimination and all well-being indicators simultaneously; well-being indicators were allowed to covary in the models. Missing data (range = 2%–5%) were handled by Mplus with full-information maximum likelihood, which utilizes all available information without imputing missing values (Enders, 2010).

The first set of hierarchical models examined the independent and conjoint influences of students’ perceived discrimination and the presence of one or more cross-ethnic friendships. We first tested main effects of these two variables (including friends’ perceptions of discrimination as a covariate), and we then added the interaction effect. When significant interactions emerged, we conducted simple slope analyses to examine the extent to which students’ perceived discrimination was linked adjustment when they had no cross-ethnic friendships versus one or more cross-ethnic friendships. We conducted an identical set of analyses to examine the independent and conjoint influences of students’ and their friends’ perceptions of discrimination (with cross-ethnic friendships included as a control). When significant interactions emerged, simple slope analyses determined the extent to which students’ perceived discrimination was linked to adjustment when their friends’ experiences of discrimination was high (1 SD above the mean) versus low (1 SD below the mean).

Results

In total, 49% of adolescents identified at least one cross-ethnic friend. Adolescent with no cross-ethnic friendships reported less peer discrimination (M = 1.15, SD = 0.37) than adolescents with at least one cross-ethnic friendship, M = 1.32, SD = 0.62, t (244) = −2.58, p < .05. Educator-perpetrated discrimination did not differ significantly between adolescents with no cross-ethnic friendships (M = 1.07, SD = 0.24) versus those with at least one cross-ethnic friendship, M = 1.11, SD = 0.40, t (244) = −0.80, p = .42. There were no significant differences in adolescent adjustment between those with and without cross-ethnic friendships, t (245) = 0.53, p = .60 for loneliness, t(245) = 0.34, p = .73 for depressive symptoms, t(245) = 0.48, p = .63 for school engagement, and t(245) = −.50, p = .62 for school belonging.

Primary Analyses

As seen in Model 1 (Table 2), adolescents reporting more peer-perpetrated discrimination were more lonely and depressed, whereas adolescents reporting more teacher-perpetrated discrimination were less engaged in school and had lower school belonging. There were few main effects of the racial/ethnic-related aspects of adolescents’ friendships with one exception. When adolescents had close friends with higher levels of peer-perpetrated discrimination, they reported greater school engagement.

Table 2.

Coefficient Estimates From Path Analyses for Relations Among Perceived Discrimination, Discrimination in the Peer Network, Cross-Ethnic Friendships, and Adolescents’ Adjustment

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | b (SE) | p | |

| Loneliness | ||||||

| Peer discrim (S) | .20 (.07) | ** | .26 (.14) | .22 (.07) | ** | |

| Edu discrim (S) | .05 (.10) | .62 (.22) | ** | .07 (.11) | ||

| Cross-ethnic friends | −.03 (.07) | −.05 (.07) | −.04 (.07) | |||

| Peer discrim (F) | −.12 (.11) | −.15 (.11) | −.11 (.11) | |||

| Edu discrim (F) | −.04 (.08) | −.06 (.08) | −.03 (.08) | |||

| Peer Discrim (S) × Cross-Ethnic (F) | −.06 (.15) | |||||

| Edu Discrim (S) × Cross-Ethnic (F) | −.77 (.23) | ** | ||||

| Peer Discrim (S) × (F) | −.16 (.23) | |||||

| Edu Discrim (S) × (F) | .29 (.56) | |||||

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||

| Peer discrim (S) | .10 (.04) | ** | .21 (.07) | ** | .11 (.04) | ** |

| Edu discrim (S) | .02 (.04) | .19 (.08) | * | .03 (.06) | ||

| Cross-ethnic friends | .02 (.04) | .01 (.04) | .02 (.04) | |||

| Peer discrim (F) | .01 (.06) | .00 (.05) | .01 (.06) | |||

| Edu discrim (F) | .02 (.06) | .00 (.06) | .03 (.06) | |||

| Peer Discrim (S) × Cross-Ethnic (F) | −0.1 (.08) | |||||

| Edu Discrim (S) × Cross-Ethnic (F) | −.24 (.09) | * | ||||

| Peer Discrim (S) × (F) | −.06 (.12) | |||||

| Edu Discrim (S) × (F) | .23 (.32) | |||||

| School engagement | ||||||

| Peer discrim (S) | −.12 (.08) | −.29 (.13) | * | −.11 (.09) | ||

| Edu discrim (S) | −.39 (.09) | *** | −.54 (.19) | * | −.35 (.09) | *** |

| Cross-ethnic friends | .00 (.08) | .01 (.08) | .01 (.08) | |||

| Peer discrim (F) | .26 (.12) | * | .27 (.12) | * | .26 (.12) | * |

| Edu discrim (F) | −.17 (.17) | −.15 (.17) | −.15 (.15) | |||

| Peer Discrim (S) × Cross-Ethnic (F) | .23 (.17) | |||||

| Edu Discrim (S) × Cross-Ethnic (F) | .21 (.22) | |||||

| Peer Discrim (S) × (F) | .00 (.27) | |||||

| Edu Discrim (S) × (F) | .73 (.49) | |||||

| School belonging | ||||||

| Peer discrim (S) | −.19 (.11 | −.62 (.20) | ** | −.23 (.11) | * | |

| Edu discrim (S) | −.37 (.15) | * | −.42 (.24) | −.37 (.16) | * | |

| Cross-ethnic friends | .06 (.10) | .08 (.09) | .07 (.10) | |||

| Peer discrim (F) | .28 (.15) | .29 (.15) | .25 (.15) | |||

| Edu discrim (F) | −.14 (.13) | −.10 (.13) | −.14 (.13) | |||

| Peer Discrim (S) × Cross-Ethnic (F) | .58 (.23) | * | ||||

| Edu Discrim (S) × Cross-Ethnic (F) | .06 (.29) | |||||

| Peer Discrim (S) × (F) | .63 (.28) | * | ||||

| Edu Discrim (S) × (F) | .18 (.87) | |||||

Note. N = 247. S = students; F = friends; Edu = educator; Discrim= discrimination.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

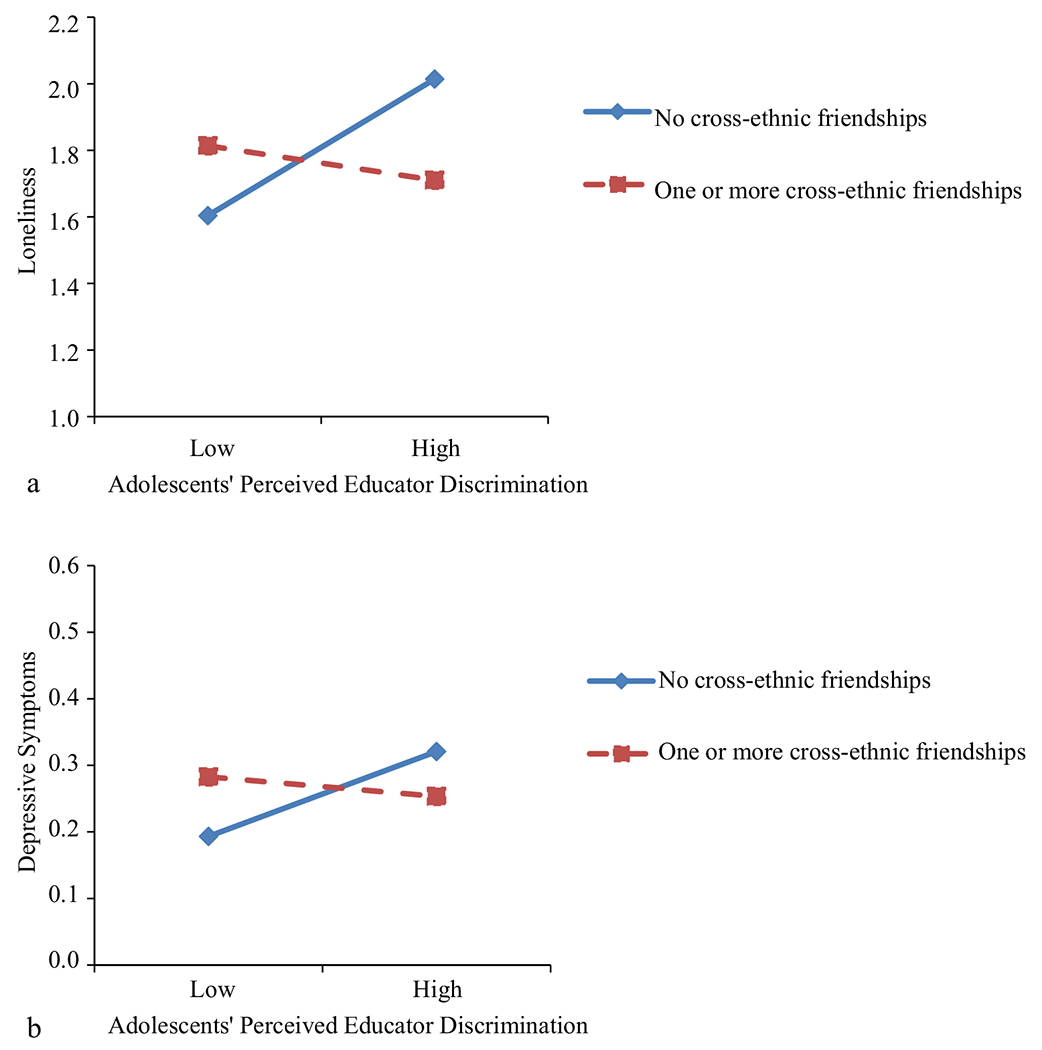

These main effects, however, masked important variation. For loneliness and depressive symptoms, we observed interaction effects between adolescents’ perceptions of educator-perpetrated discrimination and their cross-ethnic friendships (Model 2, Table 2). As seen in Figures 1a and 1b, we observed a buffering effect of cross-ethnic friendships for both loneliness and depression. Specifically, for adolescents with no cross-ethnic friends, those who perceived greater educator-perpetrated discrimination reported greater loneliness (b = .62, SE = .22, p < .01) and depressive symptoms (b = .19, SE = .08, p < .05). In contrast, adolescents who perceived greater educator discrimination but had one or more cross-ethnic friends reported lower loneliness (b = −.16, SE = .08, p < .05), and the link between educator-perpetrated discrimination and depressive symptoms was not significant for adolescents with one or more cross-ethnic friends (b = −.04, SE = .05, p = .36).

Figure 1.

Two-way interaction effects of adolescents’ perceived discrimination by educators and cross-ethnic friendships for adolescents’ (a) loneliness and (b) depressive symptoms.

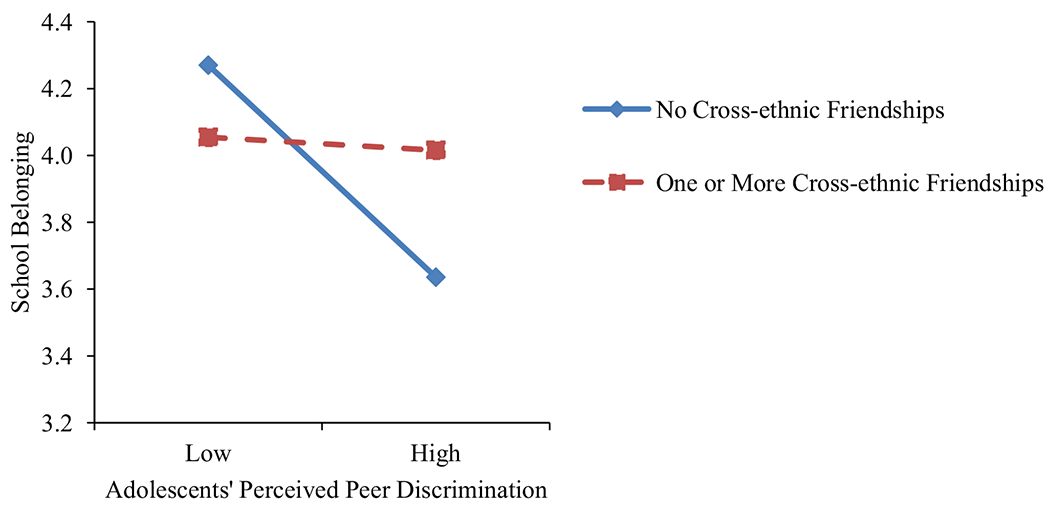

For school belonging, we observed a significant interaction between adolescents’ perceptions of peer-perpetrated discrimination and their cross-ethnic friendships as well (Model 2, Table 2). The pattern of effects, in terms of who was protected versus at risk, was identical to that observed for loneliness and depressive symptoms. As seen in Figure 2, adolescents’ perceptions of peer-perpetrated discrimination and school belonging were unrelated for those with one or more cross-ethnic friendships (b = −.04, SE = .11, p = .74), suggesting a buffering effect. In contrast, adolescents’ perceptions of peer-perpetrated discrimination were linked to lower school belonging for those with no cross-ethnic friendships (b = −.62, SE = .20, p < .01).

Figure 2.

Two-way interaction effects of adolescents’ perceived discrimination by peers and cross-ethnic friendships for adolescents’ school belonging.

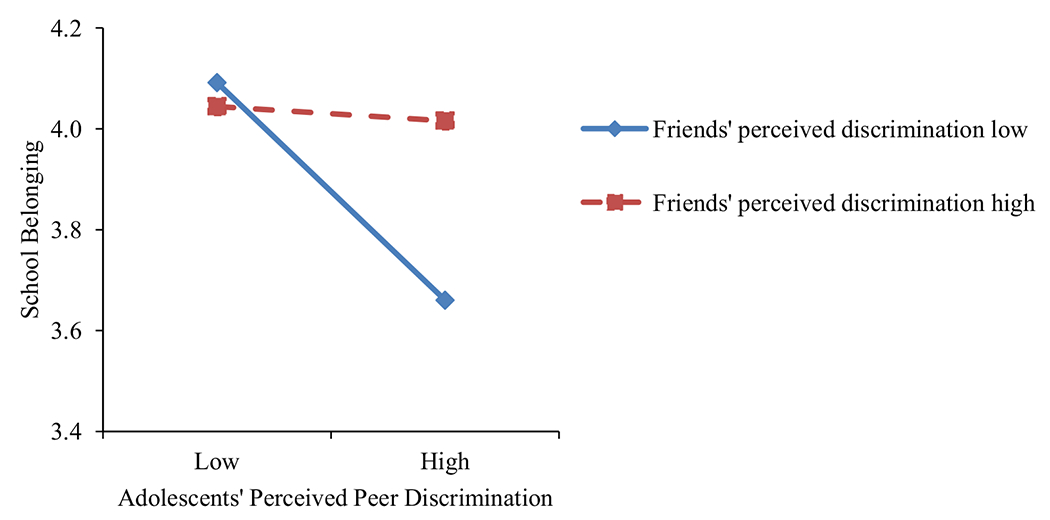

Friends’ perceptions of peer-perpetrated racial/ethnic discrimination also moderated the effects of students’ perceptions of peer-perpetrated discrimination and their feelings of school belonging (Model 3, Table 2). As seen in Figure 3, the link between students’ perceptions of peer-perpetrated discrimination and school belonging was unrelated for those whose close friends reported high levels of peer-perpetrated discrimination (b = −.03, SE = .11, p = .80). In contrast, we observed a strong, negative relation between students’ perceptions of peer-perpetrated discrimination and school belonging for those whose friends experienced little discrimination (b = −.42, SE = .17, p < .05).

Figure 3.

Two-way interaction effects of adolescents’ perceived discrimination by peers and friends’ perceived discrimination by peers for adolescents’ school belonging.

Supplementary Analyses

We conducted supplementary analyses to explore the potential moderating role of friends’ perceptions of racial/ethnic discrimination using only reports of same-ethnic friends rather than all friends. Graham et al. (2014) suggest that same-ethnic peers may serve a particular validation role, and if so, then the role of peers’ experiences of discrimination would likely be particularly potent when considering same-ethnic peers’ experiences of discrimination. In these analyses, we continued to observe a significant role of friends’ perceptions of peer-perpetrated discrimination for school belonging. An additional moderating effect, emerging only when considering same-ethnic friends’ perceptions of educator-perpetrated discrimination, also emerged for school engagement (b = .60, SE = .30, p < .05). Simple slope analyses showed that when students’ same-ethnic friends reported little educator-perpetrated discrimination, students’ own experiences of educator-perpetrated discrimination were negatively linked to lower school engagement (b = −.59, SE = .12, p < .001); this relation was not significant when students’ same-ethnic friends reported high levels of educator discrimination (b = −.22, SE = .12, p = .06).

Discussion

This study examined the independent and conjoint effects of personally experienced racial/ethnic discrimination, adolescents’ cross-ethnic friendships, and the pervasiveness of perceived discrimination within adolescents’ networks of close friends. In investigating independent contributions, we observed that the main effects of racial/ethnic discrimination were differentiated by both perpetrator and developmental domain. Specifically, educator-perpetrated discrimination was linked to academics but not socioemotional well-being, whereas the opposite pattern was found for peer-perpetrated discrimination. This was consistent with prior empirical work highlighting differentiated effects (Benner & Graham, 2013; Cogburn et al., 2011). There was, however, extensive variation in these associations once we considered racial/ethnic-related aspects of adolescents’ friendships.

First, cross-ethnic friendships appeared to be protective. In general, we found that having one or more cross-ethnic friendships attenuated some of the detrimental effects of personally experienced discrimination for adolescents. Forging cross-ethnic friendship is linked to less feelings of vulnerability (Graham et al., 2014), disconfirmation of negative expectations about intergroup contact (Mendoza-Denton, Page-Gould, & Pietrzak, 2006; Page-Gould, Mendoza-Denton, & Tropp, 2008), and a decreased likelihood of attributing experiences of prejudice specifically to race (Kawabata & Crick, 2011; Killen, 2007). Moreover, prior work has found that through more intergroup contact, such as that offered by cross-ethnic friendships, individuals experience less anxiety around cross-ethnic interactions and more empathy for out-group members (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008), which may reduce the negative effects of discrimination when experienced.

Second, students who were embedded in close friend networks characterized by high levels of peer discrimination also seemed to be protected from some of the negative effects of personally experienced discrimination. This was consistent with our hypotheses, but we did not have the ancillary data needed to test the potential mechanisms at work here. Specifically, further inquiry should examine whether the moderating role of friends’ experiences of discrimination is grounded in emotional support and coping or in the likelihood of making external attributions for the reasons for one’s discriminatory treatment. Moreover, findings from the supplementary investigation of the particular buffering effects of same-ethnic peers’ reports of discrimination may relate to psychological preparation for bias. Prior research has found that African American children with more African American friends are more likely to expect to encounter discriminatory treatment in cross-ethnic interactions (Rowley, Burchinal, Roberts, & Zeisel, 2008), and these expectations may serve to protect adolescents by reducing the likelihood of making a stress appraisal when encountering a potentially stressful event such as discriminatory treatment (Cohen & Wills, 1985). There is also evidence that same-ethnic friendships often include more shared activities between dyad members (Kao & Joyner, 2004). This may promote development of the intimacy needed to share personal struggles and elicit support in the face of stressful events such as discriminatory treatment. Indeed, sharing experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination with same-ethnic peers who identify similar struggles can support well-being (Tatum, 1997). Future work with larger and more diverse samples should further examine the role of same-ethnic versus cross-ethnic friends’ experiences of discrimination.

Strengths, Caveats, and Limitations

Our study contributes to the existing racial/ethnic discrimination literature base in two key ways. First, the pattern of relations for the main effects model provide mounting evidence for the need to consistently implement perpetrator-specific measures of discrimination. The vast majority of measures of discrimination rely on more general measures that are not perpetrator specific, but our current findings in combination with past research suggest that greater attention to who perpetrates discriminatory treatment is warranted. Second, this study provides insights into the ways adolescents’ cross-ethnic friendships and the perceived discrimination present in close friend networks matter when considering the detrimental effects of discrimination. There is a dearth of literature on both racial/ethnic-related aspects of friendships in the peer relations base and the role of friends in the adolescent racial/ethnic discrimination base, and we hope scholars will continue to pursue these lines of integrated inquiry in the future.

Although we believe the current study makes meaningful contributions, some caveats and limitations must be noted. First, our sample comprised predominantly Latino students who were the numeric majorities at the two schools in our sample, thus limiting the generalizability of our findings. Whether the racial/ethnic-related aspects of adolescent friendships under study operate similarly in schools with other demographic compositions is an open question. There is some evidence of heightened perceptions of discrimination in more racial/ethnically diverse schools (Benner & Graham, 2011; Seaton & Yip, 2009). Higher levels of diversity require a greater number of groups represented and a more equal distribution of the relative proportions of each group, and thus increasing racial/ethnic diversity necessarily limits the representation of any one group (Budescu & Budescu, 2012). As such, higher levels of diversity may prevent some groups from attaining a critical mass of same-ethnic peers, which is important for protecting against out-group bias (Linn & Welner, 2007). On the other hand, greater racial/ethnic diversity increases opportunities for cross-ethnic interactions and the potential for forging cross-ethnic friendships, which in turn can attenuate adolescents’ vulnerability within the school context (Graham et al., 2014; Kawabata & Crick, 2011). Much more work is needed to understand how these relations play out in schools with various types of demographic configurations and for students who are in the numeric majority versus minority, particularly give the increasingly segregated nature of U.S. schools (Orfield & Lee, 2007).

Similarly, we cannot determine with the current data whether the pattern of effects we observed unfold consistently across different racial/ethnic groups, as we had insufficient representation of non-Latino youth in our sample. Similarly, collapsing all Latinos into a single ethnic category may obscure subethnic differences. Prior work suggests that a complex interplay between student race/ethnicity and school characteristics (i.e., demographic composition, climate and culture, implementation of academic tracking) influences cross-ethnic friendship development (Hallinan & Teixeira, 1987; Moody, 2001). At the individual level, socioeconomic status and academic orientation also differentiate the likelihood of forming cross-ethnic friendships for certain racial/ethnic groups (Hamm et al., 2005; Quillian & Campbell, 2003), and differences in who gains the most from cross-ethnic friendships are also observed (Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005). Yet, other work suggests that the benefits of cross-group friendships (more broadly defined) are equally beneficial for the dyad member in the dominant versus stigmatized group (Davies, Tropp, Aron, Pettigrew, & Wright, 2011). As such, future research with more diverse samples is needed to replicate the effects documented here.

Finally, this study employed cross-sectional data focused on early adolescence, but evidence suggests that personal experiences of discrimination tend to increase across adolescence (Brody et al., 2006), while cross-ethnic friendships become less common (Poulin & Chan, 2010). As such, future work is needed to determine whether the processes detailed here are consistent across adolescence. Moreover, given the methodological limitations of cross-sectional designs, longitudinal studies on the focal relations are necessary to better capture the stability and directionality of the links and the potential unfolding processes underlying them. Our study, however, represents a critical first step in understanding how racial/ethnic-related aspects of adolescents’ friendship pairings come together to attenuate the links between racial/ethnic discrimination and adolescents’ well-being.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of a William T. Grant Foundation Scholar award to Aprile D. Benner and funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to the Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin (R24 HD42849). Opinions reflect those of the authors and not necessarily those of the granting agencies.

Contributor Information

Aprile D. Benner, University of Texas at Austin

Yijie Wang, Fordham University.

References

- Ajrouch KJ, Reisine S, Lim S, Sohn W, & Ismail A (2010). Perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress: Does social support matter? Ethnicity and Health, 15, 417–434. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2010.484050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, & Wheeler VA (1985). Children’s loneliness: A comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 500–505. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.4.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Graham S (2011). Latino adolescents’ experiences of discrimination across the first 2 years of high school: Correlates and influences on educational outcomes. Child Development, 82, 508–519. doi: 10.1111/j1467-8624.2010.01524.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Graham S (2013). The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: Does the source of discrimination matter? Developmental Psychology, 49, 1602–1613. doi: 10.1037/a0030557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y-F, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, … Cutrona CE (2006). Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development, 77, 1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS, & Bigler RS (2005). Children’s perceptions of discrimination: A developmental model. Child Development, 76, 533–553. doi: 10.1m/j.1467-8624.2005.00862.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, & Larson J (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In Lerner RM & Steinberg L (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol. 2: Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 74–103). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Budescu DV, & Budescu M (2012). How to measure diversity when you must. Psychological Methods, 17, 215–227. doi: 10.1037/a0027129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Motzoi C, & Meyer F (2009). Friendship as process, function, and outcome. In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 217–231). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN (2009). Sociometric methods. In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. Social, emotional, and personality development in context (pp. 82–99). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Cogburn CD, Chavous TM, & Griffin TM (2011). School-based racial and gender discrimination among African American adolescents: Exploring gender variation in frequency and implications for adjustment. Race and Social Problems, 3, 25–37. doi: 10.1007/s12552-011-9040-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K, Tropp LR, Aron A, Pettigrew TF, & Wright SC (2011). Cross-group friendships and intergroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 332–351. doi: 10.1177/1088868311411103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, & Fenton RE (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 679–695. doi: 10.1023/A:1026455906512 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, & Garcia HV (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. doi: 10.2307/1131600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson GD (1984). The effective school battery. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Bellmore A, Nishina A, & Juvonen J (2009). It must be me”: Ethnic diversity and attributions for peer victimization in middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 487–499. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9386-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Munniksma A, & Juvonen J (2014). Psychosocial benefits of cross-ethnic friendships in urban middle schools. Child Development, 85, 469–483. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Taylor AZ, & Ho AY (2009). Race and ethnicity in peer relations research. In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 394–413). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman JM, & Liang B (2008). Discrimination distress among Chinese American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9215-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Sameroff AJ, & Eccles JS (2002). the academic achievement of African American students during early adolescence: An examination of multiple risk, promotive, and protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 367–400. doi: 10.1023/A:1015389103911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan MT, & Teixeira RA (1987). Opportunities and constraints: Black-White differences in the formation of interracial friendships. Child Development, 58, 1358–1371. doi: 10.2307/1130627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan MT, & Williams RA (1989). Interracial friendship choices in secondary schools. American Sociological Review, 54, 67–78. doi: 10.2307/2095662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm JV, Brown BB, & Heck DJ (2005). Bridging the ethnic divide: Student and school characteristics in African American, Asian-Descent, Latino, and White adolescents’ cross-ethnic friend nominations. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15, 21–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00085.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter L, & Elias MJ (1999). Interracial friendships, multicultural sensitivity, and social competence: How are they related? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 20, 551–573. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(99)00028-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, & Joyner K (2004). Do race and ethnicity matter among friends? Activities among interracial, interethnic, and intraethnic adolescent friends. The Sociological Quarterly, 45, 557–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2004.tb02303.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, & Crick NR (2011). The significan of cross-racial/ethnic friendships: Associations with peer victimization, peer support, sociometric status, and classroom diversity. Developmental Psychology, 47, 1763–1775. doi: 10.1037/a0025399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M (2007). Children’s social and moral reasoning about exclusion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 32–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00470.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M (1992). Children’s depression inventory. New York, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Linn RL, & Welner KG (2007). Race-conscious policies for assigning students to schools: Social science research and the Supreme Court cases. Committee on social science research evidence on racial diversity in schools. Washington, DC: National Academy of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, & Page-Gould E (2008). Can crossgroup friendships influence minority students’ well-being at historically white universities? Psychological Science, 19, 933–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, Page-Gould E, & Pietrzak J (2006). Mechanisms for coping with status-based rejection expectations. In Levin S & van Laar C (Eds.), Stigma and group inequality: Social psychological perspectives (pp. 151–169). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Moody J (2001). Race, school integration, and friendship segregation in America. American Journal of Sociology, 107, 679–716. doi: 10.1086/338954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Nishina A, & Juvonen J (2005). Daily reports of witnessing and experiencing peer harassment in middle school. Child Development, 76, 435–450. doi: 10.1111/j1467-8624.2005.00855.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orfield G, & Lee C (2007). Historic reversals, accelerating resegregation, and the need for new integration strategies. Los Angeles, CA: Civil Rights Project, UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- Page-Gould E, Mendoza-Denton R, & Mendes WB (2014). Stress and coping in interracial contexts: The influence of race-based rejection sensitivty and crossgroup friendship in daily experiences of health. Journal of Social Issues, 70, 256–278. doi: 10.1111/josi.12059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page-Gould E, Mendoza-Denton R, & Tropp LR (2008). With a little help from my cross-group friend: Reducing anxiety in intergroup contexts through crossgroup friendship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1080–1094. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Richman LS (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF (1997). Generalized intergroup contact effects on prejudice. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin, 23, 173–185. doi: 10.1177/0146167297232006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, & Tropp LR (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 922–934. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin F, & Chan A (2010). Friendship stability and change in childhood and adolescence. Developmental Review, 30, 257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2009.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, & Kelly Y (2013). A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Social Science & Medicine, 95, 115–127. doi: 10.1016/jsocscimed.2012.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quillian L, & Campbell ME (2003). Beyond black and white: The present and future of multiracial friendship segregation. American Sociological Review, 68, 540–566. doi: 10.2307/1519738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM (2008). Racial perspective taking ability: Developmental, theoretical, and empirical trends. Handbook of Race, Racism, and the Developing Child, 16–36. doi: 10.1002/9781118269930.ch2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ME, Nargiso JE, Gaitonde LB, Stanton CA, & Colby SM (2015). Adolescent social networks: General and smoking-specific characteristics associated with smoking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76, 247–255. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, Burchinal MR, Roberts JE, & Zeisel SA (2008). Racial identity, social context, and race-related social cognition in African Americans during middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1537–1546. doi: 10.1037/a0013349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR, Postmes T, & Garcia A (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 921–948. doi: 10.1037/a0035754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, & Jackson JS (2008). The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1288–1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, & Yip T (2009). School and neighborhood contexts, perceptions of racial discrimination, and psychological well-being among African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 153–163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9356-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Dupree D, & Hartmann T (1997). A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): A self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 817–833. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum BD (1997). Why are all the black kids sitting in the cafeteria: And other conversations about race. New York, NY: Basic Books. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR, Hawi DR, Van Laar C, & Levin S (2012). Cross-ethnic friendships, perceieved discrimination, and their effects on ethnic activism over time: A longitudinal investigation of three ethnic minority groups. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51, 257–272. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR, & Pettigrew TF (2005). Relationships between intergroup contact and prejudice among minority and majority status groups. Psychological Science, 16, 951–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tynes BM, Giang MT, Williams DR, & Thompson GN (2008). Online racial discrimination and psychological adjustment among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 565–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, … Seaton E. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85, 21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M, Kinket B, & van der Wielen C (1997). Preadolescents’ understanding of ethnic discrimination. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 158, 97–112. doi: 10.1080/00221329709596655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkow MR (2006). Perceived social norms for schoolwork and achievement during adolescence. Ypsilanti, MI: Eastern Michigan University. [Google Scholar]