Abstract

Objectives:

Ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress play an important role in sexual risk behaviors for Latinx emerging adults, who are at disproportionate risk for sexually transmitted infections. Factors such as familism support and ethnic identity may be protective, yet research is limited. This study is guided by a culturally adapted stress and coping framework to examine associations of ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress with sexual risk behaviors (i.e., multiple sex partners, alcohol or drug use before sex, and condomless sex with a primary or casual partner), and examine the moderating roles of familism support and ethnic identity among Latinx emerging adults.

Methods:

Participants were recruited from Arizona and Florida, and were primarily female (51.3%) with a mean age of 21.48 years (SD = 2.06). Using cross-sectional data from 158 sexually active Latinx emerging adults, this study employed multiple logistic regression and moderation analyses.

Results:

Higher levels of ethnic discrimination and pressure to acculturate were associated with fewer sex partners, and higher levels of pressure against acculturation were associated with increased condomless sex with a casual partner. The moderation effect of higher levels of familism support on pressure to acculturate was associated with fewer sex partners, and the moderation effect of higher levels of ethnic identity on pressure against acculturation was associated with decreased condomless sex with casual partners.

Conclusions:

Examining the results within a culturally informed theoretical framework supports that protective factors may help mitigate sexual risk factors among Latinx emerging adults experiencing acculturative stress.

Keywords: Latino/a/x emerging adults, sexual risk, ethnic discrimination, acculturative stress, protective factors

High prevalence of sexual risk behaviors among emerging adults (age 18–25) in the United States remains a significant public health concern. Sexual risk behaviors—including multiple sex partners, alcohol or drug use (AOD) before sex, and condomless sex with a primary or casual partner—increase the risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In fact, individuals aged 15–24 years account for half of all new STIs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021a). Emerging adulthood is a critical developmental period impacted by risk and protective factors (Wood et al., 2018), and Latinx emerging adults (LEA) are at disproportionate risk for STIs and risky sexual behaviors (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2020). Latinx adults and adolescents experience the second highest rate of diagnosis for HIV infection (21.5 per 100,000 population) compared with White adults and adolescents (5.3 per 100,000) (CDC, 2021b). Rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea, primary and secondary syphilis, and congenital syphilis were 1.9, 1.6, 2.2, and 3.3 times higher, respectively, among Latinx compared with rates among Whites (CDC, 2020). Substance use behaviors have been linked with high-risk sexual behaviors among LEA (Brown et al., 2016; Cano et al., 2015; Chawla & Sarkar, 2019; Moore & Chau, 2019). LEA may be even more likely to engage in condomless sex compared with non-Latinx White emerging adults (Finer & Zolna, 2011; Rangel et al., 2006; Schwartz & Petrova, 2019).

Ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress contribute to sexual risk behaviors among LEA (Lorenzo-Blanco & Unger, 2015), and can be conceptualized as complex stress factors driven by racism and xenophobia as pathways for the social determinants of health (Krieger et al., 2010; Krieger, 2011; Ramírez García, 2019; Solar & Irwin, 2010). Ethnic discrimination is inequitable treatment based on one’s racial or ethnic background (Contrada et al., 2000; Williams & Mohammed, 2009), and will hereinafter be used interchangeably with discrimination. Acculturative stress is a stress response stemming from negotiating and adjusting to perceived cultural incompatibilities when interacting with the receiving culture [i.e., U.S. culture] and the heritage culture (Rodriguez et al., 2002). Emerging literature across age and racial and ethnic groups has detected mixed and indirect effects of perceived ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress on sexual risk behaviors, supporting the need for more research (Jardin et al., 2016). Among Latinx, there is growing evidence of positive associations between ethnic discrimination and sexual risk behaviors (Ayala et al., 2012; Díaz et al., 2004; Ontiniano Verissimo et al., 2020; Rosenthal et al., 2014) and between acculturative stress and sexual risk behaviors (Jardin et al., 2016; Martinez-Donate et al., 2018; Rivera et al., 2015). However, research on direct associations between ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress with sexual risk behaviors among LEA is lacking (Martinez-Donate et al., 2018; Martin-Storey & Benner, 2019; Piña-Watson et al., 2021; Rivera et al., 2015). Beyond ethnic discrimination, familism (family) support (hereinafter used interchangeably with familism) and ethnic identity may play an important role in sexual risk behaviors among LEA.

Familism (Crockett et al., 2007) and ethnic identity (Piña-Watson et al., 2021; Umaña-Taylor & Updergraff, 2007) can be protective for Latinx (Crockett et al., 2022; Ramírez García, 2019). However, research on potential relationships between such protective factors and sexual risk behaviors (Piña-Watson et al., 2021)—and the role of protective factors within the context of social determinants of health for Latinx—is scarce (Cerdeña et al., 2021). The present study examines (a) the direct association between ethnic discrimination, acculturative stress and sexual risk behaviors (i.e., multiple sex partners, AOD use before sex, and condomless sex with a primary or casual partner) and (b) familism support and ethnic identity as hypothesized protective factors that may moderate these associations. Understanding the moderation of protective factors on sexual risk behaviors can inform important prevention strategies relevant to LEA.

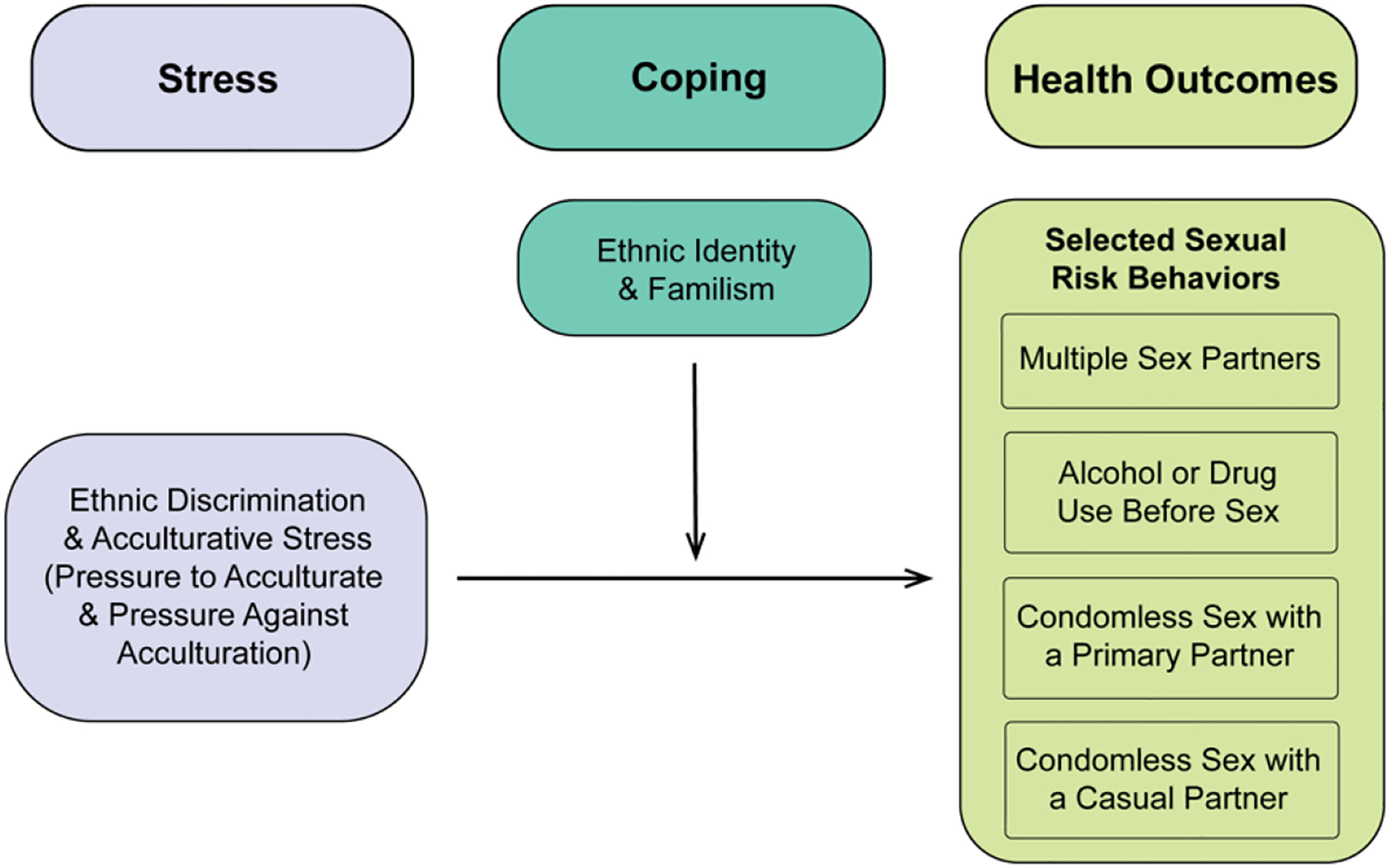

This study also addresses limitations in sexual risk behavior research among LEA by examining multiple sex partnerships (Kapadia et al., 2012), condomless sex, and AOD use before sex—all of which increase risk of HIV infection and other STIs (Copen, 2017; Deardorff et al., 2013; Ramírez-Ortiz, 2020; Stone et al., 2012)—among a sample of LEA aged 18–25 years. Guided by a stress and coping framework adapted to the Latinx community (Estrada, 2009; Walters et al., 2002), predictor variables (ethnic discrimination, acculturative stress) are hypothesized as “stress” or risk factors, and moderators (familism support and ethnic identity) are hypothesized as “coping” or protective factors for sexual risk behaviors (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Crockett et al., 2022; Estrada, 2009; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021; Sotero, 2006). This model is predicated on a social determinants of health framework (Krieger et al., 2010; Krieger, 2011; Ramírez García, 2019) in response to increasing calls for researchers and institutions to identify important risk and protective factors and address racial health inequities (Boyd et al., 2021; Cerdeña et al., 2021; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021; Ramírez García, 2019).

Association Between Ethnic Discrimination, Acculturative Stress, and Sexual Risk Behaviors

Ethnic discrimination is pervasive in the United States (Daniller, 2021; Lee et al., 2019), and racism is a serious public health threat (CDC, 2021c; Paine et al., 2021). Discrimination against Latinx, regardless of nativity, increased in recent years (Gutierrez et al., 2019), capitalizing on pre-existing Latinx racialization (Canizales & Agius Vallejo, 2021). Adverse impacts on Latinx physical and mental health (Andrade et al., 2021; Paradies et al., 2015; Paulus et al., 2019) include sexual risk behaviors (Ayala et al., 2012; Martinez-Donate et al., 2018; Ontiniano Verissimo et al., 2020). Accordant with research showing positive associations between discrimination and sexual risk across communities of color (Fields et al., 2013; Grollman, 2017), studies of discrimination that include large Latinx samples (Rosenthal et al., 2014) or Latinx-only samples have primarily revealed positive associations with sexual risk behaviors (e.g., substance use before or during sex, condomless sex in the past 3 months, in the past 12 months, and over the lifetime; Ayala et al., 2012; Díaz et al., 2004; Ontiniano Verissimo et al., 2020;), with the exception of one study which revealed negative associations (Piña-Watson et al., 2021). Studies that examine direct relationships between discrimination and sexual risk behaviors among Latinx-only samples are few, yet increasing. These studies have focused on gay men and men who have sex with men (Ayala et al., 2012; Díaz et al., 2004), Caribbean LEA in New York (Ontiniano Verissimo et al., 2020), and Mexican descent emerging adults in Texas (Piña-Watson et al., 2021). There are currently few published studies that examine direct associations between ethnic discrimination and sexual risk behaviors among LEA representing a broader range of heritages (e.g., Mexican, Caribbean, Central and South American) across more than one site in the United States.

Ethnic discrimination is both positively correlated and associated with acculturative stress among Latinx (Lee & Ahn, 2012; Torres et al., 2012). In tandem with research showing associations between acculturative stress and sexual risk across communities of color, including Latinx (Jardin et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018), cross-sectional studies of acculturative stress that include Latinx samples (Jardin et al., 2016) or Latinx-only samples (Martinez-Donate et al., 2018; Rivera et al., 2015) have revealed positive associations with sexual risk behaviors. More specifically, these studies revealed a direct association between acculturative stress and sexual risk behaviors (i.e., various behaviors including past 12-month condom usage with steady or casual partners) among a Latinx-only male Mexican migrant sample (Martinez-Donate et al., 2018), and a direct association between acculturative stress and condomless sex among LEA (Rivera et al., 2015). Studies that examine direct associations between acculturative stress and sexual risk behaviors among LEA are limited.

Protective Factors

Although ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress have been associated with sexual risk behaviors among LEA (e.g., Ontiniano Verissimo et al., 2020; Rivera et al., 2015), protective factors can mitigate these relationships (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2014). For Latinx, they may include familism support and ethnic identity (Castro et al., 2009; Crockett et al., 2022; Evans et al., 2020; Germán et al., 2009; Moise et al., 2019; Stein et al., 2017). Promising evidence shows protective effects of familism support and ethnic identity in sexual risk prevention strategies among LEA (Evans et al., 2020; Moise et al., 2019).

Familism Support as a Protective Factor

Familism is a constellation of collectivist Latinx family values that center on relationships, roles, and responsibilities among immediate and extended family (Aceves et al., 2020; Germán et al., 2009; Knight et al., 2009; Ramírez-Ortiz et al., 2020; Piña-Watson et al., 2021). While familism plays an important role across many racial and ethnic groups, it is a key cultural construct that was developed originally and most widely studied among Latinx, who report higher levels of familism compared with other racial and ethnic groups (Campos et al., 2014; Crockett et al., 2022). Limited research shows mixed results vis-à-vis moderating effects of familism as a whole concept and its embedded values (e.g., family support, involvement, parental support). Familism was associated with reduced sexual risk behaviors among Latinx adolescent girls (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009). Family involvement was specifically associated with a reduced number of lifetime sexual partners among a sample of majority Mexican-origin youth in the southwestern United States (Van Campen & Romero, 2012) and reduced substance use overall among a sample of Latinx adolescents (Castro et al., 2009). There is substantial evidence of positive associations between substance use and sexual risk across young adult and other Latinx sub-groups (Brown et al., 2016; Cano et al., 2015; Chawla & Sarkar, 2019; Dolezal et al., 2000; Moore & Chau, 2019); however, few studies demonstrated associations between familism and substance use during sex. One such study found that drinking before sex was strongly associated with condomless sex among formerly incarcerated Latinx men (Muñoz-Laboy et al., 2017). A related study of emerging adults across racial groups (16% Latinx) found that familism itself did not separately predict decreased substance use or sexual risk, yet quality of family relationships was associated with decreased substance abuse and sexual risk (i.e., intention to practice safer sex) (Maliszewski & Brown, 2014). Familism was also positively associated with condom use for Latinx men who have sex with men (Shrader et al., 2021). Limited studies examine protective effects of familism on associations between ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress on sexual risk behaviors among Latinx of any age group.

Ethnic Identity as a Protective Factor

Ethnic identity is a multidimensional concept that refers to one’s identification with values and practices associated with one’s ethnicity (Aceves et al., 2020; Andrade et al., 2021; Phinney, 1992; Umaña-Taylor & Updergraff, 2007). While protective effects of ethnic identity have been more commonly examined among Latinx adolescents (Crockett et al., 2022), fewer studies have included Latinx young and emerging adults (Iturbide et al., 2009). These studies showed mixed results on moderating effects of ethnic identity as a whole concept and its embedded dimensions (e.g., confirmation, commitment, pride, salience, development). Limited research specific to LEA showed that ethnicity-based coping increased likelihood of risky sexual behaviors (including multiple sex partners, condomless sex, and sex with a casual partner) and alcohol use among college students of Mexican descent who reported experiencing discrimination (Piña-Watson et al., 2021). Few existing studies examine protective effects of ethnic identity on associations between ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress on sexual risk behaviors among LEA across a broader range of Latinx heritage groups (e.g., Mexican, Caribbean, Central and South American).

Present Study

The present study examined associations among ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress with sexual risk behaviors. Additionally, we examined how these effects varied as a function of moderating effects of familism support and ethnic identity. Based on limited yet emerging evidence and guided by a stress-coping framework adapted to Latinx (Figure 1; Estrada, 2009; Walters et al., 2002), we hypothesized:

Both ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress would be positively associated with sexual risk behaviors.

These associations would be stronger among LEA with lower levels of familism support than those with higher levels.

They would also be stronger among LEA with lower levels of ethnic identity than those with higher levels.

Figure 1:

Culturally Adapted Stress-Coping Model Applied to Sexual Risk Behavior Among Latinx Emerging Adults. Model adapted from and etiological model of historical trauma theory model applied to Mexican Americans in United States (Estrada, 2009), which as originally adapted from an Indigenist Stress-Coping Model Adapted from “Substance Use Among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Incorporating Culture in an ‘Indigenist’ Stress-Coping Paradigm,” by K. L. Walters, J.M. Simoni, and T. Evans-Campbell, 2002, Public Health Reports, 117 Suppl 1, p. S106 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12435834/). Copyright 2002 by SAGE Publications.

Methods

Participants and Data Collection

Data are from the Project on Health among Emerging Adult Latinos (Project HEAL), a cross-sectional study comprising 200 LEA recruited between August 2018 and February 2019. The project assessed social, psychological, and cultural impacts on alcohol and nicotine use, sexual behaviors, and mental health. Participants were stratified by gender and college student status via quota sampling. Eligibility criteria included (a) identifying as Latino or Hispanic, (b) age 18–25 years old, (c) residing in Miami-Dade County, Florida, or Maricopa County, Arizona, at the time of data collection, and (d) reading in English. The present study only included 158 participants who self-reported lifetime sexual activity. Excluding the remaining 42 lifetime sexually inactive participants avoids inflation for those categorized as not at risk.

A multi-pronged approach was used to recruit an equal amount of total potential participants across sites (99 in Arizona and 101 in Florida), including social media, listservs, distribution of flyers, and word-of-mouth. Most participants were recruited in-person by college student leadership, research staff, the Principal Investigator, and other university research personnel with experience recruiting Latinx. Research staff screened potential participants by email (most students used their university email address), and those deemed eligible were emailed a unique link to provide informed consent. Upon providing consent, participants were directed to a self-administered Qualtrics survey. Participants were advised to complete the survey in a private space. Survey completion lasted approximately 50 minutes and incentives were $30 Amazon e-gift cards. Most alpha coefficients were adequate or good for all measures, decreasing likelihood of bots and fraudulent survey responses. Institutional Review Board approval was given. Additional details can be found elsewhere (Cano et al., 2020).

Of the 158 participants (Table 1), the mean age was 21.5 (SD = 2.06), with females accounting for nearly half of the total sample (n = 81, 51.3%). Most participants had just enough money for their needs (n=88, 55.7%). Participants living in Arizona accounted for slightly more than half of participants (n = 84, 53.2%). Many participants reported light skin tone (n = 125, 79.1%) and were born in the United States (n = 106, 68.4%). Approximately half identified as Mexican origin (n = 82, 51.9%), and the majority identified as heterosexual (n = 133, 84.2%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Latinx Emerging Adults Who Had Been Sexually Active in their Lifetimes from the 2018–2019 Project on Health among Emerging Adult Latinos Survey (N = 158)

| Participant characteristics | n/M | (%/SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (18–25 years) | 21.48 | 2.06 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 77 | 48.7 |

| Female | 81 | 51.3 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| More money than you need | 10 | 6.3 |

| Just enough money for your needs | 88 | 55.7 |

| Not enough money to meet your needs | 60 | 38.0 |

| Site | ||

| Florida | 74 | 46.8 |

| Arizona | 84 | 53.2 |

| Skin color | ||

| Light | 125 | 79.1 |

| Dark | 33 | 20.9 |

| Nativity | ||

| Immigrant | 49 | 31.6 |

| U.S. native | 106 | 68.4 |

| Hispanic heritage | ||

| Mexican | 82 | 51.9 |

| Other Hispanics | 76 | 48.1 |

| Sexual minority status | ||

| Heterosexual | 133 | 84.2 |

| Sexual Minority | 25 | 15.8 |

| Familism support (1–5) | 4.33 | 0.67 |

| Multigroup ethnic identity measure (1–5) | 3.92 | 0.76 |

| Ethnic discrimination (1–5) | 3.35 | 0.87 |

| Pressure to acculturate (0–5) | 2.02 | 1.28 |

| Pressure against acculturation (0–5) | 1.31 | 1.24 |

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

These included age, gender (0 = male, 1 = female), skin color (0 = light, 1 = dark), nativity status (0 = immigrant, 1 = U.S. born), Hispanic heritage (0 = Mexican, 1 = Other Hispanics), and sexual minority status (0 = heterosexual, 1 = sexual minority).

Independent Variables

Ethnic Discrimination.

Ethnic discrimination was assessed using 9 items from the perceived discrimination sub-scale of the Scale of Ethnic Experience (SEE; α = .90; Malcarne et al., 2006). The SEE is a self-report measure of multiple cognitive constructs related to ethnicity across ethnic groups. Sample questions include, “My ethnic group does not have the same opportunities as other ethnic groups”, and, “In my life, I have experienced prejudice because of my ethnicity” (Malcarne et al., 2006, p. 154). Response options were displayed on a Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Pressure to Acculturate and Pressure Against Acculturation.

Project HEAL used two sub-scales (totaling 11 items) of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (MASI; Rodriguez et al., 2002), which measures acculturative stress among people of Mexican and other Latino origins who live in the United States. Pressure to acculturate was measured using 7 items (α = .91). and pressure against acculturation was measured using 4 items (α = .87). Sample questions include, “People look down upon me if I practice Latino customs”, “I don’t feel accepted by whites” (pressure to acculturate), “People look down on me if I practice American customs”, and, “I feel uncomfortable because my family members do not know Latino ways of doing things” (pressure against acculturation) (Rodriguez et al., 2002, p. 455). Response options were displayed on a Likert scale (0 = this did not occur in the past year, 5 = extremely stressful).

Outcome Variables

All four outcomes were dichotomized and evaluated separately, with 0 indicating participants had not engaged in sexual risk behavior and 1 indicating they had. Multiple sexual partners was dichotomized by 0 = 0–1 person and 1 = 2–6 or more people.

Multiple Sex Partners.

Multiple sex partners was assessed by the question: “In the past 3 months, with how many people did you have sexual intercourse (this includes vaginal and/or anal sex)?” (Kann et al., 2018).

Alcohol or Other Drugs (AOD) Use Before Sex.

AOD use before sex was assessed by the question: “In the past 3 months, did you drink alcohol or use drugs before you had sexual intercourse (this includes vaginal and/or anal sex)?” (Kann et al., 2018).

Engagement in Condomless Sex with Primary Partner.

Engagement in condomless sex with a primary partner was ascertained with this question: “In the past 3 months, did you use a condom every time you had vaginal and/or anal sex with your primary partner (someone with whom you feel the most committed such as boyfriend/girlfriend, spouse, significant other, or life partner)?” (Kann et al., 2018).

Engagement in Condomless Sex with a Casual Partner.

Engagement in condomless sex with a casual partner was ascertained with this question: “In the past 3 months, did you use a condom every time you had vaginal and/or anal sex with a casual partner (someone with whom you do not feel committed to or know very well)?” The preceding condomless sex variables were developed by Project HEAL investigators (Ramírez-Ortiz et al., 2020).

Moderator Variables

Familism Support.

Project HEAL used a 6-item familism support subscale of the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale of Adolescents and Adults (α = .90; Knight et al., 2009), which measures Mexican American and other Latino culturally linked values during early adolescence and adulthood. Sample questions include “Parents should teach their children that the family always comes first” and “It is always important to be united as a family,” (Knight et al., 2009, pp. 459–460) with response options displayed on a Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = completely).

Ethnic Identity.

Ethnic identity was assessed using 6-items from the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure-Revised (α = .91; Phinney & Ong, 2007). Sample questions include “I have often done things that will help me understand my ethnic background better” and “I feel a strong attachment towards my own ethnic group,” (Phinney & Ong, 2007, p. 276) with response options displayed on a Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Analysis

We used R Studio V.1.2.5042 to conduct descriptive and inferential analyses and SPSS V.26 to construct the correlation matrix. The analytic approach proceeded in six steps. First, a descriptive analysis was calculated to obtain frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Second, variance inflation factor (VIF) scores were computed to detect and rule out multicollinearity between independent variables. Third, bivariate regression analyses were conducted to determine the significance of associations between each of the three independent variables (i.e., ethnic discrimination, pressure to acculturate, and pressure against acculturation) and all four outcome variables (i.e., multiple sex partners, AOD use before sex, condomless sex with primary partner, and condomless sex with a casual partner). Fourth, logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each model. Age, gender, Hispanic heritage, sexual minority status, nativity status, ethnic identity, and familism support were added to each of the logistic regression models to adjust for potential confounding. Finally, moderation terms between each of the three independent variables and familism support and ethnic identity were included to detect any moderating effects of the independent variables on sexual risk behaviors. All inferential analyses used a <0.05 alpha to test for statistical significance.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses of Outcome Variables

Table 1 presents means and standard deviations of independent and moderator variables. Mean familism support scores were 4.33 (SD = 0.67), while ethnic identity scores were 3.92 (SD = 0.67). The mean score for ethnic discrimination was 3.35 (SD = 0.87). The mean score for pressure to acculturate was 2.02 (SD = 1.28), and for pressure against acculturation was 1.31 (SD = 1.24). Table 2 presents frequencies and percentages of dichotomized outcome variables, revealing that fewer than half of all participants reported sexual risk behaviors overall. Approximately one-third of the sample reported having 2–6 sex partners (n = 46, 29.7%), while more than one-third reported using AOD before sex (n = 59, 37.2%). Less than half of participants had condomless sex with their primary partners (n = 69, 44.5%), while just below one-fifth reported condomless sex with casual partners (n = 27, 17.5%).

Table 2.

Sexual Risk Behaviors of Latinx Emerging Adults Who Had Been Sexually Active in their Lifetimes from the 2018–2019 Project on Health among Emerging Adult Latinos Survey (N = 158)

| Participant characteristics | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No. of sex partners | ||

| 0–1 person | 109 | 69.0 |

| 2–6 or more people | 49 | 31.0 |

| Alcohol/drugs before sex | ||

| No | 99 | 62.7 |

| Yes | 59 | 37.2 |

| Condomless sex with primary partner | ||

| Yes/Not at risk | 86 | 55.5 |

| No/At risk | 69 | 44.5 |

| Condomless sex with casual partner | ||

| Yes/Not at risk | 127 | 82.5 |

| No/At risk | 27 | 17.5 |

Multiple Regression and Moderation Analyses

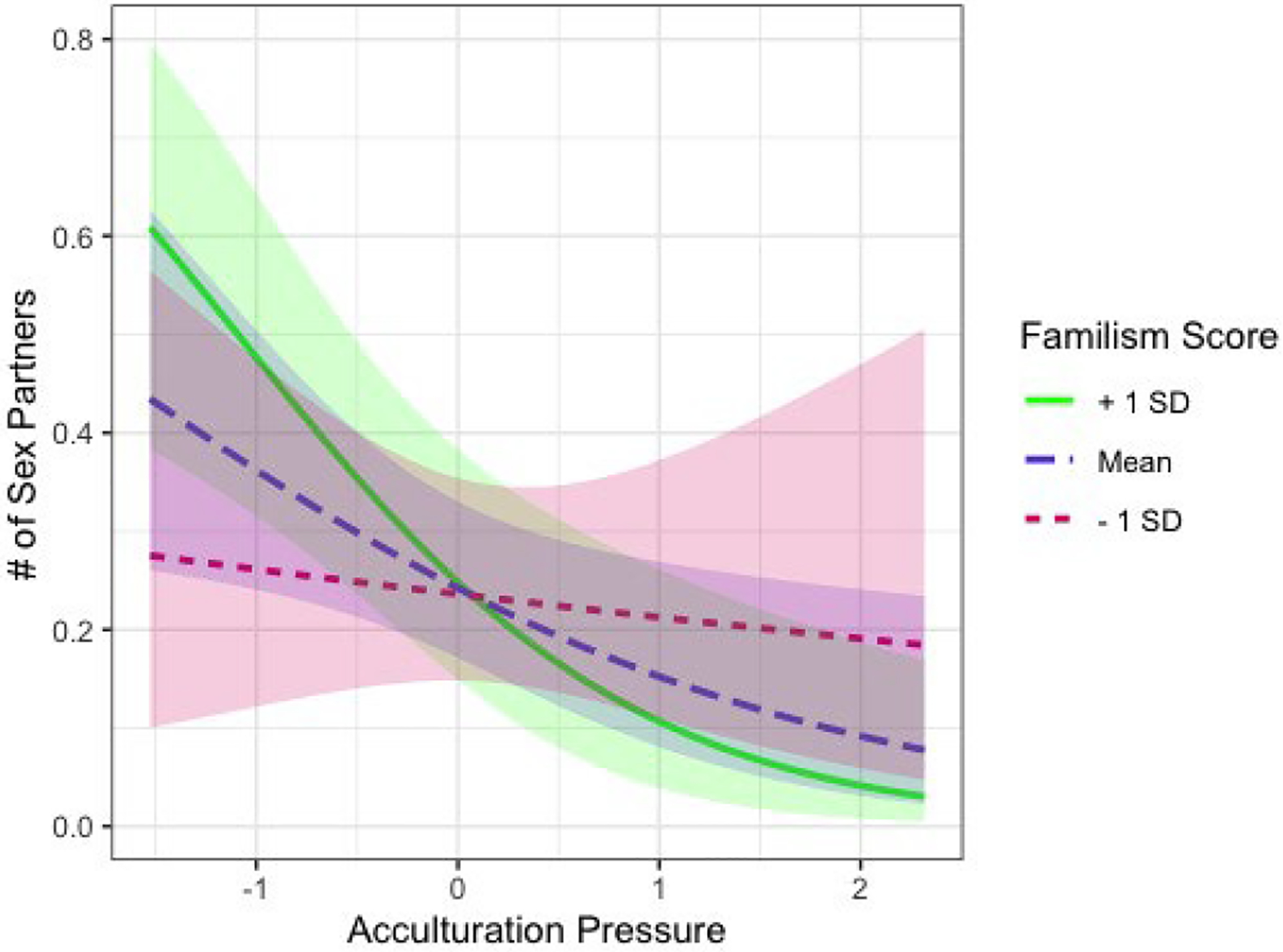

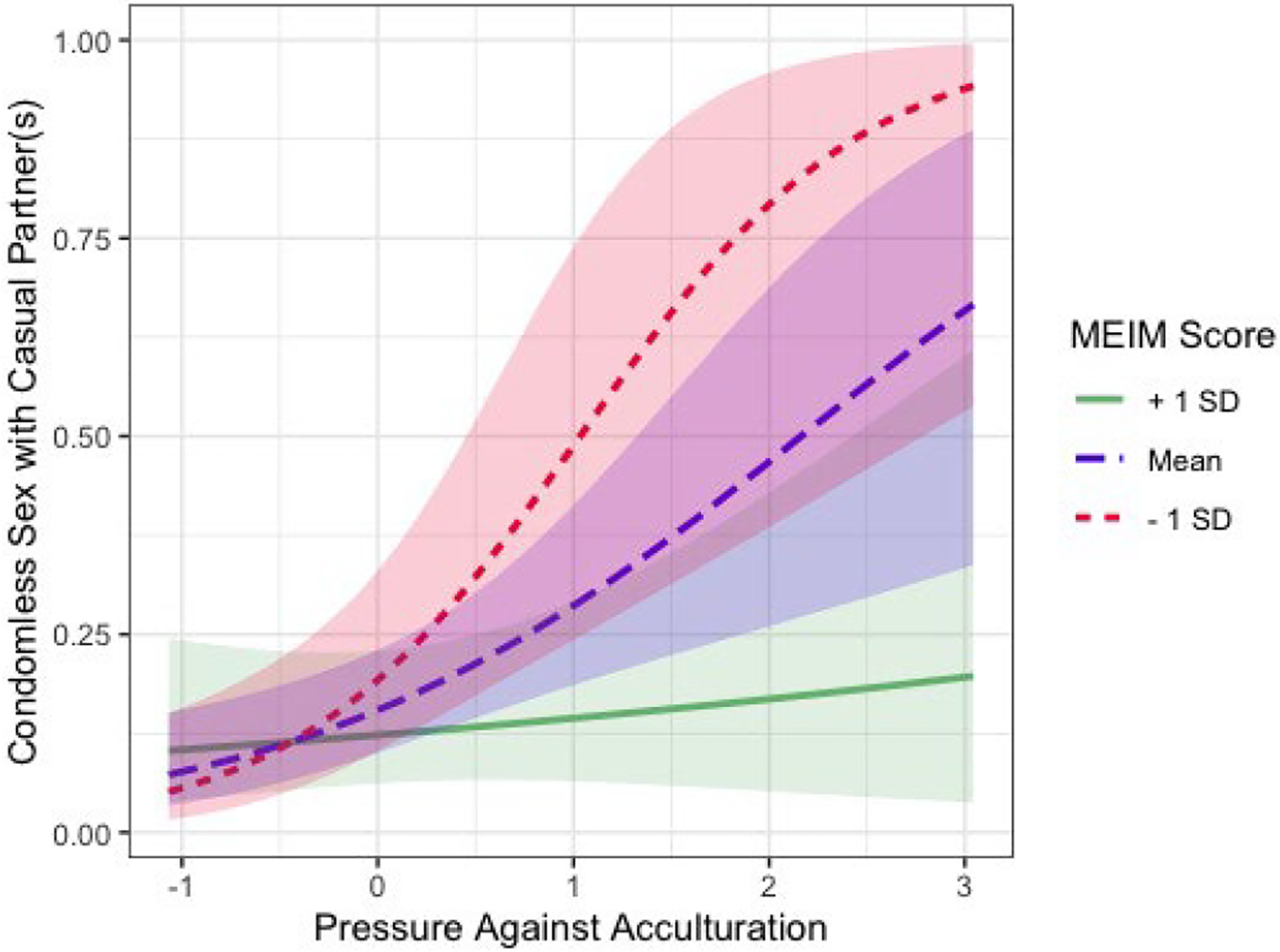

Table 3 displays results for logistic regression models estimating the probability of engaging in sexual risk behaviors by levels of ethnic discrimination, pressure to acculturate, and pressure against acculturation, holding all other variables constant. Participants who reported higher levels of ethnic discrimination had 60.8% lower odds of reporting multiple sex partners compared to those who had not experienced ethnic discrimination (OR = 0.402, 95% CI [0.232, 0.668]). Participants who reported higher levels of pressure to acculturate had 45.0% lower odds of reporting higher numbers of sex partners compared to those who did not (OR = 0.550, 95% CI [0.338, 0.868]). Adding familism support as a moderation term on this association yielded statistical significance (p = 0.043; see Fig. 2), indicating that participants who reported both higher levels of pressure to acculturate and higher levels of familism support had lower odds of reporting higher numbers of sex partners relative to those who reported lower levels of both factors. Participants who reported higher levels of pressure against acculturation had 83.4 % higher odds of reporting condomless sex with a casual partner compared to those who did not (OR = 1.834, 95% CI [1.196, 2.887]). Adding ethnic identity as a moderation term on this association yielded statistical significance (p = 0.031; see Fig. 3), indicating that participants who reported both higher levels of pressure to acculturate and higher levels of ethnic identity had lower odds of reporting condomless sex with a casual partner relative to those who reported lower levels of both factors.

Table 3: Logistic Regression Model Results.

Adjusted Effects of Ethnic Discrimination, Pressure to Acculturate, and Pressure Against Acculturation on Multiple Sex Partners Alcohol/Drug Use Before Sex, Condomless Sex with Primary Partner, and Condomless Sex with Casual Partner within the Last Three Months Among Latinx Emerging Adults in Florida and Arizona who have been Sexually Active in their Lifetimes from the 2018–2019 Project on Health among Emerging Adult Latinos Survey (N = 158)

| Independent variable | No. of sex partners OR (95% CI) |

Alcohol/Drugs before sex OR (95% CI) |

Condomless sex with primary partner OR (95% CI) |

Condomless sex with casual partner OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic discrimination | 0.402*** (0.232, 0.668) |

1.437 (0.927, 2.269) |

1.104 (0.718, 1.710) |

1.021 (0.597, 1.779) |

| Pressure to acculturate | 0.550** (0.338, 0.868) |

1.110 (0.753, 1.648) |

1.229 (0.837, 1.820) |

1.536 (0.934, 2.589) |

| Pressure against acculturation | 0.821 (0.550, 1.201) |

0.980 (0.688, 1.384) |

1.241 (0.883, 1.760) |

1.834*** (1.196, 2.887) |

Note: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

All models were adjusted for gender, age, skin color, nativity, Hispanic heritage, and sexual minority status, familism support, and multigroup ethnic identity measure.

Continuous variables including age, familism support, multigroup ethnic identity measure, ethnic discrimination, pressure to acculturate and pressure against acculturation were standardized for ease of interpretation.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

Figure 2.

Effect of Familism Support Score on Association Between Pressure to Acculturate and Multiple Sex Partners

Figure 3.

Effect of Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) Scores on Association Between Pressure Against Acculturation and Condomless Sex with Casual Partner(s)

Discussion

This study is among the first to examine associations between ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress on sexual risk behaviors (i.e., multiple sex partners, AOD use before sex, and condomless sex with a primary or casual partner), and familism support and ethnic identity as moderators on these associations among LEA. We hypothesized both ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress would be positively associated with sexual risk behaviors, and that these associations would be stronger among LEA with lower levels of familism support and ethnic identity than those with higher.

Our findings suggest a nuanced relationship between ethnic discrimination, acculturative stress, ethnic identity, familism support, and sexual risk behaviors. Contrary to our hypothesis, higher levels of ethnic discrimination and pressure to acculturate were both associated with fewer sex partners in the study sample. This finding contrasts with studies suggesting a positive association between discrimination and acculturative stress and sexual risk behaviors among LEA (Ayala et al., 2012; Díaz et al., 2004; Jardin et al., 2016; Martinez-Donate et al., 2018; Ontiniano Verissimo et al., 2020; Piña-Watson et al., 2021; Rivera et al., 2015). We offer several possible explanations. First, ethnic discrimination is positively associated with depression and generalized anxiety symptoms among participants in this sample (Cano et al., 2021), and acculturative stress is positively associated with depressive symptoms among Latinx college students (Cano et al., 2014). This majority college student sample (Cano et al., 2020) could also be impacted by evidence that perceived discrimination positively predicted academic distress (Cheng et al., 2020) and that acculturative stress was associated with family cultural conflict, which in turn was associated with increased depression among LEA college students (Cheng, 2022). Posttraumatic stress symptoms were found to mediate negative association between perceived discrimination and multiple sexual partners among Latinx adolescents (Flores et al., 2010). However, the potential mediating role of mental health symptomatology is not included in our analysis. Second, our analysis may lack important variables linked to increased sexual risk behaviors, such as social capital among emerging adults. This sample may have less social capital, and thereby fewer opportunities for sexual activity and engaging in sex risk behaviors (Cordova et al., 2022). Third, religiosity is negatively associated with fewer sex partners among LEA (Edwards et al., 2008; Haglund & Fehring, 2010), but was not included in our analysis. Finally, this majority sample of lighter-skinned, heterosexual, U.S. born, English-speaking LEA (Table 1)—of which only 29.7% reported multiple sex partners—are potentially less vulnerable to ethnic discrimination, acculturative stress, and sexual risk behaviors (Table 2; López & Hogan, 2021).

Consistent with our hypothesis and prior studies that analyzed associations between acculturative stress and condomless sex (Martinez-Donate et al., 2018; Rivera et al., 2015), higher levels of pressure against acculturation were associated with increased condomless sex with a casual partner. Furthermore, the moderation effect of higher levels of familism support on pressure to acculturate was associated with fewer sex partners (Van Campen & Romero, 2012). While we found that the moderation effect of higher levels of ethnic identity with pressure against acculturation was associated with a lower probability of reporting condomless sex with casual partners, we found no prior studies with this association. The dearth of research examining these associations between specific predictors reveals a need for greater analytic specificity. It also highlights a need to unpack these nuanced relationships with theoretical frameworks that can illuminate nuanced origins and impacts of social determinants of health on heterogeneous Latinx subgroups.

The adapted stress and coping framework (Figure 1; Estrada, 2009; Walters et al., 2002) and intersectionality (Bowleg, 2021; Crenshaw, 1991; Hill Collins, 2019; Poteat, 2021) theoretically situate our results, by contextualizing ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress as “stress” (Cano, 2014; 2021; Cheng, 2020; 2022) and familism support and ethnic identity as “coping” or protective factors (Krieger et al., 2010; Krieger, 2011), within historical foundations of the social determinants of health (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021). Settler colonialism’s production (e.g., Indigenous genocide, African enslavement; Cerdeña et al., 2021; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021) and legacy of racialization (Canizales & Agius Vallejo, 2021), political violence, and migration-related multigenerational stressors, drive social, health, and economic inequities across Latin America and the United States. Intergenerational traumas (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019)—or psychological harms resulting from historically oppressive systems and events that impact the health and well-being of subsequent generations (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019; Estrada, 2009; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021)—can result. Intergenerational resilience—or multilevel (e.g., individuals, communities) transmission of strengths (e.g., cultural values, practices, relationships), despite adversities, to subsequent generations (Cerdeña et al, 2021)—coexists through familism and ethnic identity as protective factors (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2020; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021). Intergenerational traumas and resiliencies are unique to social locations (e.g., race, gender, class) (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Estrada, 2009; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021). Intersectional theory describes complex, interconnected and historically-rooted systems of oppression (e.g., associated with race, gender, and social class), and can help articulate the relationship between social location and unique experiences of ethnic discrimination and/or acculturative stress across heterogeneous Latinx subgroups (Bowleg, 2021; Cole, 2009; Crenshaw, 1991; DeBlaere et al., 2018; Hill Collins, 2019; Poteat, 2021).

Applying these frameworks helps identify key clinical and policy interventions (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2020; López & Hogan, 2021; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021). Researchers call for inclusion of acculturative stress prevention (Jardin et al., 2016) and familism and ethnic identity as protective factors (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2014) in sexual health prevention strategies (Evans et al., 2020; Moise et al., 2019). Our findings suggest that familism support and ethnic identity are targeted intervention points in sexual risk prevention efforts for LEA who experience acculturative stress. Clinical practice strategies could include assessment questions and treatment plans that account for discrimination and acculturation-related stressors, as well as familism and ethnic identity as potential protective factors (Fernandez & Beltrán, 2022). Tailoring sexual and reproductive health interventions for LEA can increase effectiveness of interventions (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2020). Meta-analyses have identified significant gaps in availability of culturally-relevant sexual health interventions for Latinx youth (Cardoza et al., 2012) and evidence that they produce increased condom usage compared to nontailored interventions (Evans et al., 2020).

Using culturally-informed, historically-situated theoretical frameworks (Krieger et al., 2010; Krieger, 2011; Ramírez García, 2019) can drive more equitable policy interventions, such as funding community development projects and programs that center culturally-relevant protective factors for LEA (Fernandez & Beltrán, 2022). These frameworks highlight structural factors influencing predictors while accounting for Latinx heterogeneity. They thereby strengthen practice and policy (Cerdeña et al., 2021; López & Hogan, 2021), which contributes to dismantling racism (Boyd et al., 2021; López & Hogan, 2021) and health inequities (Bowleg, 2021) through identifying, articulating, and disseminating evidence and approaches that name their root causes (Bowleg, 2021; Boyd et al., 2021).

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study limitations first include the use of cross-sectional data, which precluded our ability to test for temporality between associated variables of interest. While this study provides evidence of associations between ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress and sexual risk behaviors, as well as protective effects of familism support and ethnic identity on certain sexual risk behaviors, a longitudinal study design would enable observation of individual-level change in experiences at multiple time points. Furthermore, while emerging adulthood is a crucial period for heightened sexual risk behaviors (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2020; Wood et al., 2018), this age group experiences evolving identity formation (Côté, 2006; Schwartz et al., 2005), which may implicate an evolving relationship with familism support and ethnic identity. Thus, longitudinal data could provide a more comprehensive understanding of whether and to what extent these factors are protective throughout emerging adulthood. Second, the use of self-reported measures to collect data on behavioral outcome variables commonly risks recall and social desirability biases. Data were collected about past 3-month sexual risk behaviors using an online survey methodology in which confidentiality was safeguarded to reduce the impact of these biases. Third, this analysis lacks inclusion of important variables that are linked with increased sexual risk behaviors, such as social capital. Future studies could control for social capital to determine potential impacts on sexual risk behaviors among LEA (Cordova et al., 2022). Fourth, it should also be noted that while ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress have unique theoretical integrity as predictor variables, components of ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress scales may have overlapping construct validity. Future research could involve measurement development with LEA, guided by theoretical frameworks such as the adapted stress and coping framework and intersectionality that account for such nuances and distinctions between these two measures. Furthermore, these measures could be developed with Latinx subgroups, and examine whether and to what extent differences exist in experience of ethnic discrimination or acculturative stress by variables such as skin color, nativity, or language.

Constraints on Generality

While our non-probability sample of LEA represented ethnic subgroup diversity similar to the overall Latinx population in the United States, our sample size limited our ability to test for ethnic subgroup variation. Furthermore, though the sample was split fairly evenly across binary gender categories, most participants were U.S.-born college students and identified as lighter-skinned and heterosexual, which also limits generalizability. Fewer than one-fifth to one-half of our sample reported sexual risk behaviors overall, and all reported above-average familism support and ethnic identity scores. Overall, our sample may have been less susceptible to ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress relative to those with fewer social and economic privileges (Araújo & Borrel, 2006; Arce et al., 1987; Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019; Montalvo & Codina, 2001; Telzer & Vazquez Garcia, 2009). Given these sampling limitations, we controlled for age, gender, skin color, nativity, Latinx (Hispanic) heritage, and sexual minority status in our statistical models to recognize the intersectionality of this heterogeneous population. Future research could examine differences among Latinx subgroups across intersectional identities to better identify risk and protective factors and account for diverse impacts on health, through specific subgroup comparison, measurement, and intervention development. In addition, a Spanish language survey was not offered due to inadequate funding, which limited survey eligibility to monolingual English and bilingual speakers only. Including a Spanish language survey could capture greater cultural diversity in future work. Finally, physical location may impact results. The sample was split evenly between urban Florida and Arizona sites only. Latinx represent 69.1% of Miami-Dade County (U.S. Department of Commerce [USDOC], n.d. -d)—more than 2.5 times their proportion of Florida state (26.8%) (USDOC, n.d. -b), while they represent nearly the same proportion of Maricopa County (32%) (USDOC, n.d. -c) compared with Arizona state (32.3%) (USDOC, n.d. -a). Differences in Latinx demographics, as well as political and social opportunities that could be linked with perceived discrimination and acculturative stress may vary across U.S. cities (Sanchez et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2014; Stepick & Stepick, 2002) and rural areas. To increase generalizability, this study could be replicated across multiple sites that include rural areas.

Conclusions

Sexual risk behaviors are a significant public health concern for LEA in the United States (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2020). While previous research provides evidence of the impacts of ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress on sexual risk behaviors among Latinx (Ayala et al., 2012; Díaz et al., 2004; Jardin et al., 2016; Martinez-Donate et al., 2018; Ontiniano Verissimo et al., 2020; Rivera et al., 2015), research examining potential protective factors has been limited. Mainstream health research largely emphasizes individual risk factors yet minimizes cultural, structural, and historical contexts as determinants of health (Boyd et al., 2021). In response, leading health scholars and institutions have called for a deeper examination of the social determinants of the health for Latinx, in order to not only account for important risk and protective factors (Cerdeña et al., 2021; Orozco-Figueroa, 2021; Ramírez García, 2019) but to also better understand how Latinx heterogeneity may impact experiences with ethnic discrimination and pressure to acculturate and potentially influence health outcomes. This study’s findings suggest that protective factors may help mitigate sexual risk behaviors among LEA who experience acculturative stress. Results may implicate the important protective role of familism support and ethnic identity, as well as the importance of using intersectional and culturally-congruent theoretical frameworks in the design and development of measures and interventions to address sexual risk behaviors among this population. Furthermore, using theoretical frameworks that are culturally informed and situated within the social determinants of health, while accounting for intersectional heterogeneity, can provide researchers, practitioners, and policymakers with more effective, sustainable social and behavioral strategies that advance racial equity and social justice in sexual risk prevention and health promotion among LEA (López & Hogan, 2021).

Public Significance Statement:

Ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress can be linked with sexual risk behaviors among Latinx emerging adults. This study found that while ethnic discrimination and pressure to acculturate were linked with fewer sex partners, pressure against acculturation was linked to increased condomless sex with a casual partner. Family support and ethnic identity can be protective in the prevention of sexual risk behaviors among Latinx emerging adults who experience acculturative stress.

Acknowledgments

All authors declare that we have no conflicts of interest and do not have any financial disclosures to report. This research was not pre-registered in an independent, institutional registry. Preparation of this article was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [K01 AA025992, L60 AA028757] and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [U54 MD002266] awarded to Dr. Miguel Ángel Cano; the National Institute on Drug Abuse [1R03DA041891-01A1] and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research [UL1TR002240] awarded to Dr. David Cordova; Daisy Ramirez-Ortiz was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [U54MD012393]; and Angela Fernandez was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [R25DA051343]. These funding sources had no other role than financial support. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health. This research was not preregistered in an independent, institutional registry. Data for the parent study and study materials are available from Dr. Miguel Ángel Cano upon request. Analytic methods for the present secondary data analysis are available from Dr. Angela Fernandez upon request. The authors would like to acknowledge Carlos Estrada and Irma Beatriz Vega de Luna for their work in recruiting participants.

The present study builds upon and enhances previous work from the HEAL Project Dataset. It examines sexual risk outcome variables and interactions between ethnic discrimination and acculturative stress, and family support and ethnic identity—which has not been previously analyzed with this dataset. It is also the first to use acculturation stress as an independent variable of interest and sexual risk behaviors as outcome variables. Below is a complete reference list of these articles.

References

- Aceves L, Griffin AM, Sulkowski ML, Martinez G, Knapp KS, Bámaca-Colbert MY, & Cleveland HH (2020). The affective lives of doubled-up Latinx youth: Influences of school experiences, familism, and ethnic identity exploration. Psychology in the Schools, 1–18. 10.1002/pits.22391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade N, Ford AD, & Alvarez C (2021). Discrimination and Latino health: A systematic review of risk and resilience. Hispanic Health Care International, 19(1), 5–16. 10.1177/1540415320921489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo BY, & Borrell LN (2006). Understanding the link between discrimination, mental health outcomes, and life chances among Latinos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 28(2), 245–266. 10.1177/0739986305285825 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arce CH, Murguia E, & Frisbie WP (1987). Phenotype and life chances among Chicanos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9, 19–32. 10.1177/073998638703090102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala G, Bingham T, Kim J, Wheeler DP, & Millett GA (2012). Modeling the impact of social discrimination and financial hardship on the sexual risk of HIV among Latino and Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 102(Suppl 2), S242–S249. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2021). Evolving intersectionality within public health: From analysis to action. American Journal of Public Health, 111(1), 88–90. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd R, Krieger N, De Maio F, & Maybank A (2021, April 21). The world’s leading medical journals don’t write about racism. That’s a problem. Time. https://time.com/5956643/medical-journals-health-racism/ [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Gause NK, & Northern N (2016). The association between alcohol and sexual risk behaviors among college students: A review. Current Addiction Reports, 3(4), 349–355. 10.1007/s40429-016-0125-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canizales SL, & Agius Vallejo J (2021). Latinos and racism in the Trump era. Daedalus, 150(2), 150–164. 10.1162/daed_a_01852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campos B, Ullman JB, Aguilera A, & Dunkel Schetter C (2014). Familism and psychological health: The intervening role of closeness and social support. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(2), 191–201. 10.1037/a0034094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Castillo LG, Castro Y, de Dios MA, & Roncancio AM (2014). Acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among Mexican and Mexican American students in the U.S.: Examining associations with cultural incongruity and intragroup marginalization. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, 36(2), 136–149. 10.1007/s10447-013-9196-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Gonzalez Castro F, De La Rosa M, Amaro H, Vega WA, Sánchez M, Rojas P, Ramirez-Ortiz D, Taskin T, Prado G, Schwartz SJ, Cordova D, Salas-Wright CP, & De Dios M (2020). Depressive symptoms and resilience among Hispanic emerging adults: Examining the moderating effects of mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, family cohesion, and social support. Behavioral Medicine, 46(3–4), 245–257. 10.1080/08964289.2020.1712646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MÁ, Schwartz SJ, MacKinnon DP, Keum B, Prado G, Marsiglia FF, Salas-Wright CP, Cobb CL, Garcini LM, De La Rosa M, Sánchez M, Rahman A, Acosta LM, Roncancio AM, & de Dios MA (2021). Exposure to ethnic discrimination in social media and symptoms of anxiety and depression among Hispanic emerging adults: Examining the moderating role of gender. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 571–586. 10.1002/jclp.23050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MÁ, Vaughan EL, de Dios MA, Castro Y, Roncancio AM, & Ojeda L (2015). Alcohol use severity among Hispanic emerging adults in higher education: Understanding the effect of cultural congruity. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(11), 1412–1420. 10.3109/10826084.2015.1018538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoza VJ, Documét PI, Fryer CS, Gold MA, & Butler J 3rd. (2012). Sexual health behavior interventions for U.S. Latino adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 25(2), 136–149. 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Stein JA, & Bentler PM (2009). Ethnic pride, traditional family values, and acculturation in early cigarette and alcohol use among Latino adolescents. Journal of Primary Prevention, 30(3e4), 265. 10.1007/s10935-009-0174-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a, April 8). Adolescents and young adults. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/std/life-stages-populations/adolescents-youngadults.htm [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b, May). HIV Surveillance Report, 2019, (32), 12. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-32.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021c, April 8). Media statement from CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, on racism and health. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0408-racism-health.html [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, September 14). Health disparities in HIV, viral hepatitis, STDs, and TB Hispanics/Latinos. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/healthdisparities/hispanics.html [Google Scholar]

- Cerdeña JP, Rivera LM, & Spak JM (2021). Intergenerational trauma in Latinxs: A scoping review. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 270, 113662. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Dueñas NY, Adames HY, Perez-Chavez JG, & Salas SP (2019). Healing ethno-racial trauma in Latinx immigrant communities: Cultivating hope, resistance, and action. American Psychologist, 74(1), 49–62. 10.1037/amp0000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla N, & Sarkar S (2019). Defining “high-risk sexual behavior” in the context of substance use. Journal of Psychosexual Health, 1(1), 26–31. 10.1177/2631831818822015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HL (2022). Acculturative stress, family relations, and depressive symptoms among Latinx college students: A cross-lagged study. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 10(1), 39–53. 10.1037/lat0000197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HL, McDermott RC, Wong YJ, & McCullough KM (2020). Perceived discrimination and academic distress among Latinx college students: A cross-lagged longitudinal investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(3), 401–408. 10.1037/cou0000397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64, 170–180. 10.1037/a0014564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contrada RJ, Ashmore RD, Gary ML, Goups E, Egeth JD, Sewell A, & Chasse V (2000). Ethnicity-related sources of stress and their effects on well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(4), 136–139. 10.1111/1467-8721.00078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Copen CE (2017). Condom use during sexual intercourse among women and men aged 15–44 in the United States: 2011–2015 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports, 105, 1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova D, Coleman-Minahan K, Romo T, Borrayo EA, & Bull S (2022). The role of social capital, sex communication, and sex refusal self-efficacy in sexual risk behaviors and HIV testing among a diverse sample of youth. Adolescents, 2(1), 30–42. 10.3390/adolescents2010004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Côté JE (2006). Emerging adulthood as an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In Arnett JJ & Tanner JL (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 85–116). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/11381-004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Iturbide MI, Torres Stone RA, McGinley M, Raffaelli M, & Carlo G (2007). Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: Relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(4), 347–355. 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Streit C, & Carlo G (2022). Cultural mechanisms linking mothers’ familism values to externalizing behaviors among Midwest U.S. Latinx adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. Advance online publication. 10.1037/cdp0000551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniller A (2021, March 18). Majorities of Americans see at least some discrimination against Black, Hispanic and Asian people in the U.S Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/18/majorities-of-americans-see-at-least-some-discrimination-against-black-hispanic-and-asian-people-in-the-u-s/ [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E, de Groat CL, Steinberg JR, & Ozer EJ (2013). Latino youths’ sexual values and condom negotiation strategies. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 45(4),182–90. 10.1363/4518213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBlaere C, Watson LB, & Langrehr KJ (2018). Intersectionality applied: Intersectionality is as intersectionality does. In Travis CB, White JW, Rutherford A, Williams WS, Cook SL, & Wyche KF (Eds.), APA handbook of the psychology of women: History, theory, and battlegrounds (pp. 567–584). American Psychological Association. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.umich.edu/10.1037/0000059-029 [Google Scholar]

- Díaz RM, Ayala G, & Bein E (2004). Sexual risk as an outcome of social oppression: Data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three U.S. cities. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(3), 255–267. 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal C, Carballo-Diéguez A, Nieves-Rosa L, & Díaz F (2000). Substance use and sexual risk behavior: Understanding their association among four ethnic groups of Latino men who have sex with men. Journal of Substance Abuse, 11(4), 323–336. 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00030-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM, Fehring RJ, Jarrett KM, & Haglund KA (2008). The influence of religiosity, gender, and language preference acculturation on sexual activity among Latino/a adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 30(4), 447–462. 10.1177/0739986308322912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada A (2009). Mexican-Americans and historical trauma theory: A theoretical perspective. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 8(3), 330–340. 10.1080/15332640903110500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R, Widman L, Stokes MN, Javidi H, Hope EC, & Brasileiro J (2020). Sexual health programs for Latinx adolescents: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 146, 1–14. 10.1542/peds.2019-3572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AR, & Beltrán RE (2022). “Wherever I go, I have it inside of me”: Indigenous cultural dance narratives as substance abuse and HIV prevention in an urban Danza Mexica community. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 789865. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.789865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields EL, Bogart LM, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, Klein DJ, & Schuster MA (2013). Association of discrimination-related trauma with sexual risk among HIV-positive African American men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 875–880. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, & Zolna MR (2011). Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception, 84,478–485. 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores E, Tschann JM, Dimas JM, Pasch LA, & de Groat CL (2010). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and health risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(3), 264–273. 10.1037/a0020026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germán M, Gonzales NA, & Dumka L (2009). Familism values as a protective factor for Mexican-origin adolescents exposed to deviant peers. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(1), 16–42. 10.1177/0272431608324475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grollman E (2017). Sexual health and multiple forms of discrimination among heterosexual youth. Social Problems, 64(1), 156–175. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26370894 [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Jaccard J, Lesesne C, & Ballan M (2009). Family mediators of acculturation and adolescent sexual behavior among Latino youth. Journal of Primary Prevention, 30, 395–419. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Hidalgo A, & Keene L (2020). Consideration of heterogeneity in a meta-analysis of Latino sexual health interventions. Pediatrics, e20201406. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez A, Ocampo AX, Barreto MA, & Segura G (2019). Somos más: How racial threat and anger mobilized latino voters in the Trump era. Political Research Quarterly, 72(4), 960–975. 10.1177/1065912919844327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund KA, & Fehring RJ (2010). The association of religiosity, sexual education, and parental factors with risky sexual behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Religion and Health, 49(4), 460–472. 10.1007/s10943-009-9267-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Collins P (Ed.). (2019). What’s critical about critical social theory? In Intersectionality as critical social theory (pp. 54–84). Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iturbide MI, Raffaelli M, & Carlo G (2009). Protective effects of ethnic identity on Mexican American college students’ psychological well-being. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 31(4), 536–552. 10.1177/0739986309345992 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jardin C, Garey L, Sharp C, & Zvolensky MJ (2016). Acculturative stress and risky sexual behavior: The roles of sexual compulsivity and negative affect. Behavior Modification, 40(1–2), 97–119. 10.1177/0145445515613331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, & Ethier KA (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(8). https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2017/ss6708.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia F, Frye V, Bonner S, Emmanuel PJ, Samples CL, & Latka MH (2012). Perceived peer safer sex norms and sexual risk behaviors among substance-using Latino adolescents. AIDS Education and Prevention, 24(1), 27–40. 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.1.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, & Updegraff KA (2009). The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30, 444–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (2011). Epidemiology and the people’s health: Theory and context. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Alegria M, Almeida-Filho N, Barbosa da Silva J, Barreto ML, Beckfield J, Berkman L, Birn AE, Duncan BB, Franco S, Acevedo Garcia D, Gruskin S, James SA, Laurell AC, Schmidt MI, & Walters KL (2010). Who—and what—causes health inequities? Reflections on emerging debates from an exploratory Latin American/North American workshop. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 64(9), 747–749. 10.1136/jech.2009.106906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DL, & Ahn S (2012). Discrimination against Latina/os: A meta-analysis of individual-level resources and outcomes. The Counseling Psychologist, 40(1), 28–65. 10.1177/0011000011403326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RT, Perez AD, Boykin CM, & Mendoza-Denton R (2019). On the prevalence of racial discrimination in the United States. PloS One, 14(1), e0210698. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, & Unger JB (2015). Ethnic discrimination, acculturative stress, and family conflict as predictors of depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among Latina/o youth: The mediating role of perceived stress. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(10), 1984–1997. 10.1007/s10964-015-0339-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López N, & Hogan H (2021). What’s your Street Race? The urgency of critical race theory and intersectionality as lenses for revising the U.S. Office of Management and Budget guidelines, census and administrative data in Latinx communities and beyond. Genealogy, 5(3), 75. 10.3390/genealogy5030075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M, Malcolm LR, Diaz-Albertini K, Klinoff VA, Leeder E, Barrientos S, & Kibler JL (2014). Latino cultural values as protective factors against sexual risks among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 37(8), 1215–1225. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcarne VL, Chavira DA, Fernandez S, & Liu PJ (2006). The Scale of Ethnic Experience: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86, 150–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliszewski G, & Brown C (2014). Familism, substance abuse, and sexual risk among foster care alumni. Children and Youth Services Review, 36, 206–212. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.11.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Donate AP, Zhang X, Gudelia Rangel M, Hovell MF, Gonzalez-Fagoaga JE, Magis-Rodriguez C, & Guendelman S (2018). Does acculturative stress influence immigrant sexual HIV risk and HIV testing behavior? Evidence from a survey of male Mexican migrants. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(4), 798–807. 10.1007/s40615-017-0425-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Storey A, & Benner A (2019). Externalizing behaviors exacerbate the link between discrimination and adolescent health risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(9), 1724–1735. 10.1007/s10964-019-01020-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moise RK, Meca A, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Ángel Cano M, Szapocznik J, Piña-Watson B, Des Rosiers SE, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Soto DW, Pattarroyo M, Villamar JA, & Lizzi KM (2019). The use of cultural identity in predicting health lifestyle behaviors in Latinx immigrant adolescents. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(3), 371–378. 10.1037/cdp0000229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo FF, & Codina GE (2001). Skin color and Latinos in the United States. Ethnicities, 1, 321–341. 10.1177/146879680100100303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, & Chau. (2019, October 15). Opioid and illicit drug use among the Hispanic/Latino populations. Substance Abused and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). https://blog.samhsa.gov/2019/10/15/opioid-and-illicit-drug-use-among-the-hispaniclatino-populations [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Laboy M, Martínez O, Guilamo-Ramos V, Draine J, Eyrich Garg K, Levine E, & Ripkin A (2017). Influences of economic, social and cultural marginalization on the association between alcohol use and sexual risk among formerly incarcerated Latino men. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19, 1073–1087. 10.1007/s10903-017-0554-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontiniano Verissimo AD, Dyer TP, Friedman SR, & Gee GC (2020). Discrimination and sexual risk among Caribbean Latinx young adults. Ethnicity & Health, 25(5), 639–652. 10.1080/13557858.2018.1444148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Figueroa A (2021). The history of adversity and collective strength of individuals of Mexican ancestry in the United States: A scoping literature review and emerging conceptual framework. Genealogy, 5(2), 32. 10.3390/genealogy5020032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paine L, de la Rocha P, Eyssallenne AP, Andrews CA, Loo L, Jones CP, Collins AM, & Morse M (2021). Declaring racism a public health crisis in the United States: Cure, poison, or both?. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 676784. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.676784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gupta A, Kelaher M, & Gee G (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 10(9), e0138511. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus DJ, Rodriguez-Cano R, Garza M, Ochoa-Perez M, Lemaire C, Bakhshaie J, Viana AG, & Zvolensky MJ (2019). Acculturative stress and alcohol use among Latinx recruited from a primary care clinic: Moderations by emotion dysregulation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(5), 589–599. 10.1037/ort0000378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7(2), 156–176. 10.1177/074355489272003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271–281. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piña-Watson B, Cox K, & Neduvelil A (2021). Mexican descent college student risky sexual behaviors and alcohol use: The role of general and cultural based coping with discrimination. Journal of American College Health, 1–8. 10.1080/07448481.2019.1656214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T (2021). Navigating the storm: How to apply intersectionality to public health in times of crisis. American Journal of Public Health, 111(1), 91–92. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez García JI (2019). Integrating Latina/o ethnic determinants of health in research to promote population health and reduce health disparities. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 21–31. 10.1037/cdp0000265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Ortiz D, Sheehan DM, Moore MP, Ibañez GE, Ibrahimou B, De La Rosa M, & Cano MÁ (2020). HIV testing among Latino emerging adults: Examining associations with familism support, nativity, and gender. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 10.1007/s10903-020-01000-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel MC, Gavin L, Reed C, Fowler MG, & Lee LM (2006). Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS among adolescents and young adults in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39,156–163. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera PM, Gonzales-Backen MA, Yedlin J, Brown EJ, Schwartz SJ, Caraway SJ, Weisskrich RS, Yeong SY & Ham LS (2015). Family violence exposure and sexual risk-taking among Latino emerging adults: The role of posttraumatic stress symptomology and acculturative stress. Journal of Family Violence, 30(8), 967–976. 10.1007/s10896-015-9735-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Myers HF, Mira CB, Flores T, & Garcia-Hernandez L (2002). Development of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory for adults of Mexican origin. Psychological Assessment, 14, 451–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L, Earnshaw VA, Lewis JB, Lewis TT, Reid AE, Stasko EC, Tobin JN, & Ickovics JR (2014). Discrimination and sexual risk among young urban pregnant women of color. Health Psychology, 33(1), 3–10. 10.1037/a0032502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M, Rosa MDL, Blackson TC, Sastre F, Rojas P, Li T, & Dillon F (2014). Pre- to postimmigration alcohol use trajectories among recent Latino immigrants. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(4), 990–999. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.umich.edu/10.1037/a0037807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Benet-Martínez V, Knight GP, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Des Rosiers SE, Stephens DP, Huang S, & Szapocznik J (2014). Effects of language of assessment on the measurement of acculturation: Measurement equivalence and cultural frame switching. Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 100–114. 10.1037/a0034717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Côté JE, & Arnett JJ (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood: Two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth & Society, 37, 201–229. 10.1177/0044118X05275965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, & Petrova M (2019). Prevention science in emerging adulthood: A field coming of age. Prevention Science, 20, 305–309. 10.1007/s11121-019-0975-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrader CH, Arroyo-Flores J, Skvoretz J, Fallon S, Gonzalez V, Safren S, Algarin A, Johnson A, Doblecki-Lewis S, & Kanamori M (2021). PrEP use and PrEP use disclosure are associated with condom use during sex: A multilevel analysis of Latino MSM egocentric sexual networks. AIDS and Behavior, 25, 1636–1645. 10.1007/s10461-020-03080-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solar O, & Irwin A (2010) A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health (Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 [Policy and Practice]). World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44489/9789241500852_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- Sotero MM (2006). A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 1, 93–108. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1350062 [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Rivas-Drake D, & Camacho TC (2017). Ethnic identity and familism among Latino college students: A test of prospective associations. Emerging Adulthood, 5(2), 106–115. 10.1177/2167696816657234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stepick A, & Stepick CD (2002). Power and identity: Miami Cubans. In Suárez-Orozco MM & Páez M (Eds.), Latinos: Remaking America (pp. 75–92). Harvard. [Google Scholar]

- Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, & Catalano RF (2012). Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 37(7):747–75. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, & Vazquez Garcia HA (2009). Skin color and self-perceptions of immigrant and U.S.-born Latinas: The moderating role of racial socialization and ethnic identity. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 31(3), 357–374. 10.1177/0739986309336913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Driscoll MW, & Voell M (2012). Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: A moderated mediational model. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(1), 17–25. 10.1037/a0026710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Updegraff KA (2007). Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce. (n.d.-a). QuickFacts: Arizona. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/AZ/PST045221 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce. (n.d.-b). QuickFacts: Florida. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/dashboard/FL/RHI725221? [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce. (n.d.-c). QuickFacts: Maricopa County, Arizona. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI725221 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce. (n.d.-d). QuickFacts: Miami-Dade County, Florida. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/miamidadecountyflorida/RHI725220 [Google Scholar]

- Van Campen KS, & Romero AJ (2012). How are self-efficacy and family involvement associated with less sexual risk taking among ethnic minority adolescents? Family Relations, 61(4), 548–558. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00721.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM, & Evans-Campbell T (2002). Substance abuse among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping model. Public Health Reports, 117(Suppl. 1), 5104–5117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 20–47. 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood D, Crapnell T, Lau L, Bennett A, Lotstein D, Ferris M, & Kuo A (2018). Introduction to the handbook of life course health development. In Halfon N, Forrest C, Lerner R, & Faustman E (Eds.), Handbook of life course health development (pp. 123–143). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-47143-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Xu Y, Chen X, Yu B, Yan H, & Li S (2018). Acculturative stress, poor mental health and condom-use intention among international students in China. Health Education Journal, 77(2), 142–155. 10.1177/0017896917739443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

HEAL Data Reference List

- Cano MA, Sánchez M, De La Rosa M, Rojas P, Ramírez-Ortiz D, Bursac Z, Meca A, Schwartz SJ, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Zamboanga BL, Garcini LM, Roncancio AM, Arbona C, Sheehan DM, & de Dios MA (2020). Alcohol use severity among Hispanic emerging adults: Examining the roles of bicultural self-efficacy and acculturation. Addictive Behaviors, 108, 106442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]