Abstract

Abstract

The therapeutic potential of purinergic signaling has been explored for a wide variety of diseases, including those related to the skin. In this study, we used the self-assembled skin substitutes (SASS), a highly functional reconstructed human skin model, which shares many properties with normal human skin, to study the impact of purinergic receptors agonists, such as ATP, UTP and a P2Y receptor antagonist, Reactive Blue 2 during wound healing. After treating the wounded skins, we evaluated the wound area, reepithelialization, length of migrating tongues toward the wound, quality of the skins through the cytokeratin 10 and laminin-5 expression, epidermal and dermal cell proliferation. In addition, the expression of the main ectoenzymes capable of hydrolyzing nucleotides were investigated through the wounded SASS regions: unwounded region, wound margin, intermediate region and migrating epidermal tongue. After 3 days, under the UTP treatment, the wounded SASS showed an increase in the reepithelialization and in the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, without altering the quality of the skin. We also identified the presence of the ectoenzymes NTPDase1 and NPP1 in the reconstructed human skin model, suggesting their involvement in wound healing. Considering the need for new therapies capable of promoting healing in complex wounds, although these results are still preliminary, they suggest the involvement of extracellular nucleotides in human skin healing and the importance to understand their role in this mechanism. New experiments it will be necessary to determine the mechanisms by which the purinergic signaling is involved in the skin wound healing.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12079-023-00725-2.

Keywords: Wound healing, Purinergic signaling, NTPDase1, NPP1, Self-assembled skin substitutes (SASS), Reconstructed human skin model

Introduction

Wound healing is one of the most complex processes in the human body. It greatly depends on the extent and synchronization of a variety of cell types in the phases of hemostasis, inflammation, growth, re-epithelialization, and remodeling (Martin 1997; Singer and Clark 1999; Gurtner et al. 2008; Rodrigues et al. 2019).

The epidermis can self-regenerate due to the presence of stem cells (Blanpain and Fuchs 2006). In wounds, reepithelialization progresses by the growth and migration of keratinocytes from the surrounding wound margins toward the center, with the regeneration of an stratified and differentiated epidermis over the dermo-epidermal junction in reorganization (Stanley et al. 1981). In case of deep injuries and burns, the process of healing is not adequate, leading to a chronic wound as a consequence (Blanpain and Fuchs 2006; Vig et al. 2017). The development of chronic, non-healing wounds is a persistent medical problem that causes patient morbidity or even death and increases healthcare costs (Veith et al. 2019).

While several wound healing therapies are available, the effectiveness is only moderate. Therefore, there is a need for more efficient therapies to heal complex wounds. Reconstructed human skin models are upcoming alternatives to treat patients by promoting tissue regeneration (Proulx et al. 2011; Rodrigues et al. 2019). In addition, this 3D models can be used to understand the mechanisms of wound healing (Laplante et al. 2001; Xie et al. 2010), skin aging (Diekmann et al. 2016; Weinmüllner et al. 2020), psoriasis (Jean et al. 2011), hypertrophic scar (Moulin 2021), cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (Commandeur et al. 2009) and melanoma (Hill et al. 2015). Therefore, skin models are promising tools to reach new advances that can be translated to benefit patients.

Several tissue engineered skin substitutes have been developed and optimized, based on culture conditions, cell sources, cell types and natural or synthetic dermal substrates, in order to better mimic the composition of the skin (Choudhury and Das 2021) or with the aim to improve the healing using mesenchymal stem cells (Naasani et al. 2018; Naasani et al. 2019). One example is the self-assembled skin substitutes (SASS) are a tissue-engineered skin composed by a natural collagen extracellular matrix, secreted by the own fibroblasts, without using any exogenous scaffold or biomaterial, underlying a fully differentiated epidermis (Beaudoin Cloutier et al. 2017). The self-assembly approach allows the reconstruction of a highly functional bilayered skin substitute, which shares many properties with native human skin (Larouche et al. 2016). The capacity to preserve stem cells (Lavoie et al. 2013), make the SASS a suitable skin substitute for autologous graft in humans, without a host immune rejection when is produced with cells isolated from the patient, making it suitable for clinical use in burn treatment (Germain et al. 2018).

The purinergic signaling plays important and diverse roles in skin physiology and wound healing (Burnstock et al. 2012a). Extracellular nucleotides (ATP, ADP, AMP, UTP) are signaling molecules of the purinergic cascade and influence a variety of physiological processes, such as endocrine and exocrine secretions, immune responses, inflammation, proliferation, differentiation, migration, cell death and regeneration (Geoffrey Burnstock 2007a, b). Once released, nucleotides activate P2X ionotropic receptors (P2X1-7) and P2Y metabotropic receptors (P2Y1,2,4,6,11–14) responsive to tri/diphosphate nucleotides (Abbracchio et al. 2006; Burnstock 2007a, b). Whereas all P2X receptors are activated by Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), P2Y receptor subtypes differ from each other according to their nucleotide selectivity. These receptors are activated by several nucleotides including ATP, UTP, ADP and UDP (Huang et al. 2021).

Nucleotide-induced responses can be modulated by the ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase family (NTPDases 1–8); the nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family (NPP1-3) and ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73). (Zimmermann 2001; Robson et al. 2006). The NTPDases hydrolyze triphosphate (ATP and UTP) and diphosphate (ADP and UDP) nucleotides to their monophosphate derivates (adenosine 5’-monophosphate (AMP) and uridine 5′-monophosphate (UMP) (Kukulski et al. 2005). AMP and UMP are then further hydrolyzed by CD73 to generate adenosine and uridine, respectively. The adenosine can activate the P1 type receptors (A1, A2a, A2b and A3). Therefore, these enzymes are powerful tools to control the effects mediated by extracellular purines and pyrimidines (Anderson and Parkinson 1997; Robson et al. 2006).

There is a growing interest in the therapeutic potential of purinergic compounds (Burnstock 2018), several studies evaluated the P1 and P2 purinergic receptors in various types of skin cells (White et al. 2009; Burnstock et al. 2012b). Additionally, it has become evident that P2 receptor agonists and antagonists may have therapeutic potential (Gendaszewska-Darmach and Kucharska 2011). However, the mechanisms involved in extracellular ATP signaling are poorly understood, particularly in the human dermis (Flores-Muñoz et al. 2021).

More information on these processes would be crucial for establishing future clinical applications using the nucleotides potential for tissue regeneration, without undesirable side effects. Therefore, in order to contribute with the understanding of the role of purinergic signaling in wound healing, in this study we used the self-assembled skin substitutes (SASS) to investigate the effect of agonists ATP and UTP, and antagonist of P2Y purinergic receptors, Reactive Blue 2 (RB2) on a wound healing model. After the treatment of the wounded skins, we evaluate the wound area, reepithelialization, the length of migrating tongues toward the wound, the quality of the skins through the CK10 and laminin-5 expression, epidermal and dermal cell proliferation, and the NTPDase1 and NPP1 expression.

Materials and methods

Cell isolation and culture

Primary human Keratinocytes and fibroblast were isolated and cultured as described (Moulin 2021). The source of cells are small pieces of skin removed by surgery and following procedures approved by the institution’s committee for the protection of human subjects (Moulin 2021).

Briefly, the epidermis and dermis were separated after a thermolysin (0.5 mg/mL, Sigma, St-Louis, MO, USA) incubation process. Then, keratinocytes were isolated using a 0.05% trypsin/ 0.01% EDTA solution. Fibroblasts were isolated from the dermis using collagenase H (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Qc, Canada). Keratinocytes were grown on a feeder layer of irradiated human fibroblast, obtained as described previously (Moulin 2021) and then cultured in keratinocyte medium: Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/Ham's F12 Medium (3:1) supplemented with 5% FetalClone II serum (HyClone, GEHealthcare Life Sciences, Mississauga, Ont, Canada), 10 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor, 5 μg/mL Insulin, 0.4 μg/mL Hydrocortisone, 0.212 μg/mL Isoproterenol, 100 IU/mL, penicillin G and 25 μg/mL Gentamicin. Before the keratinocytes reached confluence, they were detached and used until the third passage.

Dermal fibroblast were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% Fetal calf serum (Wisent, Saint-Bruno, QC, Canada), 100 IU/mL Penicillin G, 25 μg/mL Gentamicin until they achieve the confluence.

The cells were counted with a cell counter (Beckman Coulter ® Life Sciences). The cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C, 7% CO2.

Self assembled skin substitute

The self assembled skin substitute (SASS) was produced as described previously (Germain et al. 2018). For the dermal sheet, 5 × 104 fibroblasts/well were seeded into 12 well plate containing a anchoring paper (Whatman® filter) and cultured with fibroblast medium. When they reached confluence, cells were treated with 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid during one month in order to secrete an abundant extracellular matrix and to form the dermal sheet. Keratinocytes were then seeded on a first dermal sheet (DS1) at 8 × 105 cells/well with keratinocyte medium containing 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid and maintained for 4 days with daily media changes to form a keratinocyte sheet. After four days, the epidermal sheet was stacked with a second dermal sheet (DS2), and kept in place thanks to Ligaclip®. Skin were then placed on the air–liquid interface and cultured in air–liquid medium (DMEM/Ham F12, supplemented with 5% FetalClone II serum, 5 μg/mL Insulin, 0.4 μg/mL Hydrocortisone, 0.212 μg/mL Isoproterenol, 100 IU/mL, penicillin G and 25 μg/mL Gentamicin). Medium was changed every 48 h for 14 days to achieve formation of a stratified epidermis.

Each skin substitute was produced with keratinocytes and fibroblast from the same patient and two different patients were used.

A normal human skin (NHS) specimen from the LOEX biological material bank (previously approved by the institutional ethics committee for utilization in research was used as control for histological analysis.

Wound healing model

The wound healing model was performed with some modifications of the model described by Laplante et al. (2001). The SASS was wounded with a 4 mm diameter biopsy punch, and stacked with a third dermal sheet (DS3) to allow the migration of the epidermal tongue. The wounded SASS was placed on the air–liquid interface and cultured with the different treatments that will be described below.

Treatments and wound area measure

To evaluate the effect of the nucleotides and the P2Y receptors on the wound healing, the wounded reconstructed human skin were cultured with DMEM/Ham F12, supplemented with 5% FetalClone II, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid, penicillin G and 25 μg/mL Gentamicin (Control), which was used as a base medium for the different treatments: 100 μM Adenosine triphosphate (ATP); 100 μM Uridine triphosphate (UTP); 100 μM Reactive blue 2 (RB2). For the positive control (Control+), DMEM/Ham F12 media supplemented with 5% FetalClone II serum, and the additives: 5 μg/mL Insulin, 0.4 μg/mL Hydrocortisone, 0.212 μg/mL Isoproterenol, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid, 100 IU/mL Penicillin G and 25 μg/mL Gentamicin was used.

Following 3 days of treatment, the wound was photographed with a phase contrast microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TS-100) and the wound area was calculated using ImageJ software. Wounded SASS was then used for histological analysis. Two different patients were analyzed in triplicates.

Masson’s Trichrome staining

The morphology of wounded SASS after 3 days of healing was evaluated using Masson's Trichrome staining performed on 5um thick sections. Histological micrographs were performed with a Zeiss microscope equipped with Zeiss Axiocam HRm Rev 3 (Carl Zeiss Canada Ltd. Toronto, ON, Canada). The length of migrating tongues (part of the migrating epidermis into the wound) was measured using ImageJ software. Cells were derived from two different patients and analyzed in triplicates.

Immunofluorescence

Wounded tissues were embedded in Tissue-Tek® Optimal Cutting Temperature Compound (Sakura Finetek USA), frozen in liquid nitrogen and maintained at − 80 °C for cryostat sectioning. Indirect immunofluorescence assays were performed on 5-μm-thick cryosections of skins following permeabilization with acetone (10 min at − 20 °C). The antibodies used were: mouse monoclonal anti-Laminin 5 (γ2 chain) clone D4B5 (EMD Millipore; 1:400 dilution); mouse monoclonal anti-CK10 clone RKSE60 (Cedarlane,Burlington, ON, Canada; 1:100 dilution); rabbit polyclonal IgG anti-Ki67 Ab15580 (Abcam, 1:200 dilution); Polyclonal guinea pig anti-human NTPDase1/CD39 (Name: hN1-1C; hN1-2C; hN1-3C) (Ectonucleotidases-ab, Canada; 1:300 dilution); Polyclonal guinea pig anti-human NPP1 (Name: hNPP1-1C; hNPP1-2C; hNPP1-3C) (Ectonucleotidases-ab, Canada; 1:300 dilution). Primary antibodies were replaced by PBS-BSA 1% or preimmune serum for NTPDase1 and NPP1 as negative controls. The tissue sections were incubated with the primary antibody for 1 h and 15 min at room temperature. After PBS washes the respective secondary antibody was added and incubated for 30 min in a humid chamber. The following secondary antibodies were used: Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly CrossAdsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (A21206) (Thermo Fisher Scientific); Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 594 A11005 (ThermoFisher Scientific); Goat anti-Guinea Pig IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 594 (ThermoFisher Scientific). The cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst reagent 33,258 (Sigma Chemicals). Fluorescent micrographs were observed and photographed under a Zeiss microscope equipped with Zeiss Axiocam ICc1 digital camera.

Ki67 positive cells were quantified using imageJ software and the percentage was calculated in relation to the cell nuclei in each field. The NTPDase1 and NPP1 relative fluorescence intensity was quantified as described by Jensen (2013). We adjusted the threshold in the positive control to select the fluorescence regions and the intensity measurements were performed within regions of interest (ROIs) to separately quantify intensity in the epidermis and in the dermis. The relative fluorescence intensity was expressed as the integrated density (IntDen) by each total ROI area in μm2. Two different patients were analyzed in duplicates.

Scratch wound healing assay on normal human keratinocytes

The migration capabilities of normal human keratinocytes were assessed using a scratch wound healing assay. The keratinocytes were seeded into 12-well cell culture plates, containing a feeder layer of irradiated human fibroblast, at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/well, and cultured in a keratinocyte medium to produce a nearly confluent cell layer. After 24 h, the cells were treated with 10 μg/ml Mitomycin C (m4287) for 3 h. A linear wound was generated in the layer using a sterile 200 uL plastic pipette tip to produce a scratch. Any cellular debris was removed with PBS before adding the following treatments: DMEM/Ham F12, supplemented with 5% FetalClone II, penicillin G and 25 μg/mL Gentamicin, as the control media used for the different treatments: 100 μM Adenosine triphosphate (ATP); 100 μM Uridine triphosphate (UTP); 100 μM Reactive blue 2 (RB2). Positive control (Control+) was DMEM/Ham F12 media supplemented with 5% FetalClone II serum, 10 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor, 5 μg/mL Insulin, 0.4 μg/mL Hydrocortisone, 0.212 μg/mL Isoproterenol, 100 IU/mL, Penicillin G and 25 μg/mL Gentamicin. The migration progress was monitored and photographed with a phase contrast microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TS-100) at 0 h, 24 h and 48 h. The area of the scratch in each image was estimated using imageJ software. Scratch area on 0th hour was considered 100%, for each respective image, and the reduction in area was calculated for each set in 24 and 48 h. Two different patients were analyzed in triplicates.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed statistically by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test for the wound healing assay and the length of migrating tongues. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test for the Ki67 expression, the scratch wound assay and relative fluorescence intensity was used. We also performed an unpaired t-test to compare the NHS versus the SASS in the Ki67 expression and relative fluorescence intensity. Statistically significant differences were accepted when p < 0.05.

Results

Wound healing assay on the self-assembled skin substitute

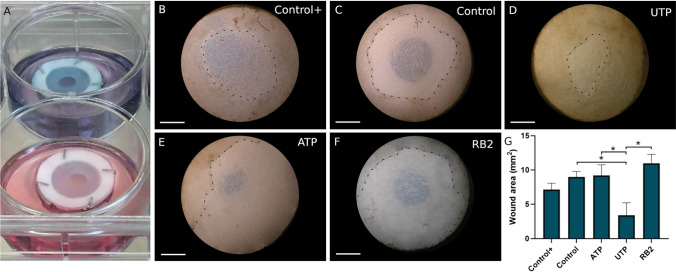

The Self-Assembled Skin Substitute was successfully produced from human keratinocytes seeded on dermal sheets. Fibroblasts secreted abundant extracellular matrix and formed macroscopically visible natural sheets, in which it was possible to seed the keratinocytes and stack to form the SASS, with uniform macroscopic aspect. A circular wound was produced on this reconstructed human skin. Following addition of a third dermal sheet, keratinocytes can migrate to allow the wound reepithelialization (Fig. 1a). From this model, it was possible to microscopically observe the wound closure through the ring of reepithelialization that progressed toward the wound center. The effect of the nucleotides and the P2Y receptors on the wound healing was analyzed using ATP, UTP, and RB2 treatments diluted in the medium, containing serum, but without additives (Insulin, Hydrocortisone and Isoproterenol), used as a control treatment. Therefore, we used the complete air–liquid medium as positive control. After 3 days in culture, the effect of diverse treatments on healing was observed by following the reepithelialization progress (Fig. 1b–f). The quantification was done by measuring the wound area, which was lower after the UTP treatment, when compared with the Control and RB2 treatments (Fig. 1g and supplementary Figure 2).

Fig. 1.

Wound healing assay on the self-assembled skin substitute. a Macroscopic aspect of the wounded SASS on the air–liquid interface at day 0; note that RB2 is a blue dye (top) vs control (bottom). Wounds after 3 days according the different treatments, b control+ (see below), c control (see below), d 100 μM UTP in control medium, e 100 μM ATP in control medium, f 100 μM RB2, the dotted black lines point the ring of reepithelialization from the border to the center of the wound. g The wound area (mm2) following quantitative evaluation. SASS was produced from cells obtained from two different patients, N = 2, in triplicates. Data were analyzed statistically by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test. Graph bars represent the mean with SD (*p < 0.05). Control+: DMEM/Ham F12 + 5% FetalClone II serum, Insulin, Hydrocortisone, Isoproterenol, ascorbic acid; Control: DMEM/Ham F12 + 5% FetalClone II, ascorbic acid. Phase contrast micrograph. Scale bars: 500 μm

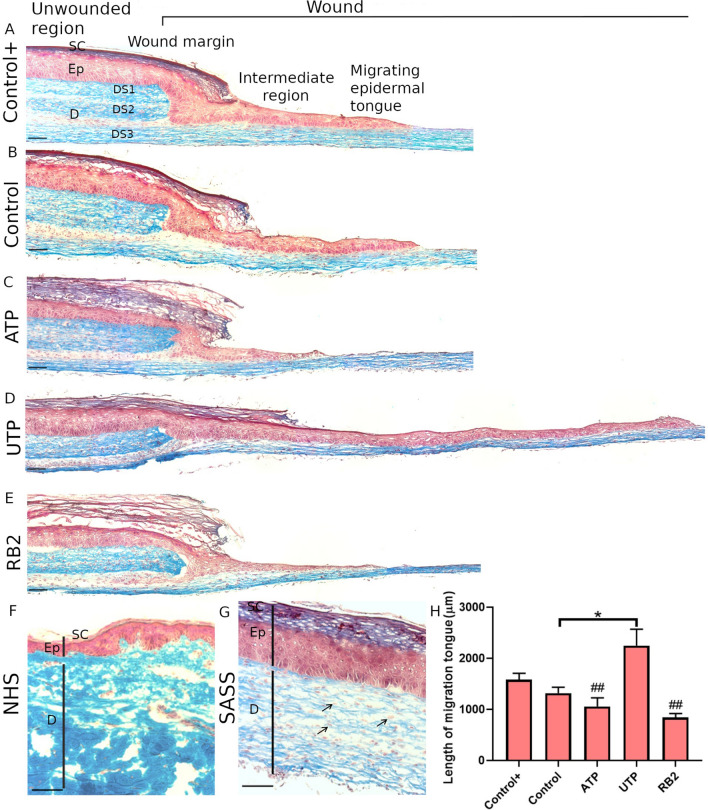

Histological cross-section of the wound healing model.

Histological analysis was performed to evaluate the integrity of the reconstructed human skin and the reepithelialization progress after treatment with agonists and antagonists of P2Y receptors. Following Masson's Trichrome staining it was possible to discriminate the epidermis from the dermis. An stratified epithelium until the stratum corneum was properly obtained. A dermis, composed of fibroblasts embedded into a rich extracellular matrix, colored in blue, displayed a microscopic structure similar to the normal human skin (Fig. 2a, f, g). The wounded reconstructed human skin was composed by the unwounded region and the wound. The unwounded region contains a fully differentiated epidermis above the three dermal sheets that form the dermis, whereas, the wound is composed by the wound margin, the limit area that was injured, followed by the intermediate region and the migrating epidermal tongue, that represents the migrating keratinocytes, without stratum corneum, on the third dermal sheet. We observed differences in the length of migrating tongues according to treatments (Fig. 2a–e). The length of migrating tongues was measured and UTP treatment induced statistically significant increase in keratinocyte migration compared to Control, ATP and RB2 treatments. (Fig. 2h).

Fig. 2.

Masson's trichrome staining in the wounded Self-Assembled Skin Substitute. Histological cross-section of the reconstructed human skin showing the unwounded region and the wound, composed by the wound margin, the intermediate region and the migrating epidermal tongue. It is possible to differentiate the epidermis layer (Ep) with the stratum corneum (SC) from the dermis (D) and the three dermal sheets (DS1,2,3), the third sheet belongs to the wound assay model, allowing the migration of the epidermal tongue; a Control+, b Control, c ATP, d UTP and e RB2. Similarity between the normal human skin (NHS) (f) and the Self-Assembled Skin Substitute (SASS) (g) are shown, the fibroblasts embedded in the collagen fibers are indicated. H) The length of migrating tongues were measured. One-way ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc test (*p < 0.05: different from Control and Control+) (##p < 0.01: different from UTP) Graph bars represent the mean with SD. SASS was produced from cells obtained from two different patients, N = 2, in triplicate. Scale bars 100 μm

Immunofluorescence analysis

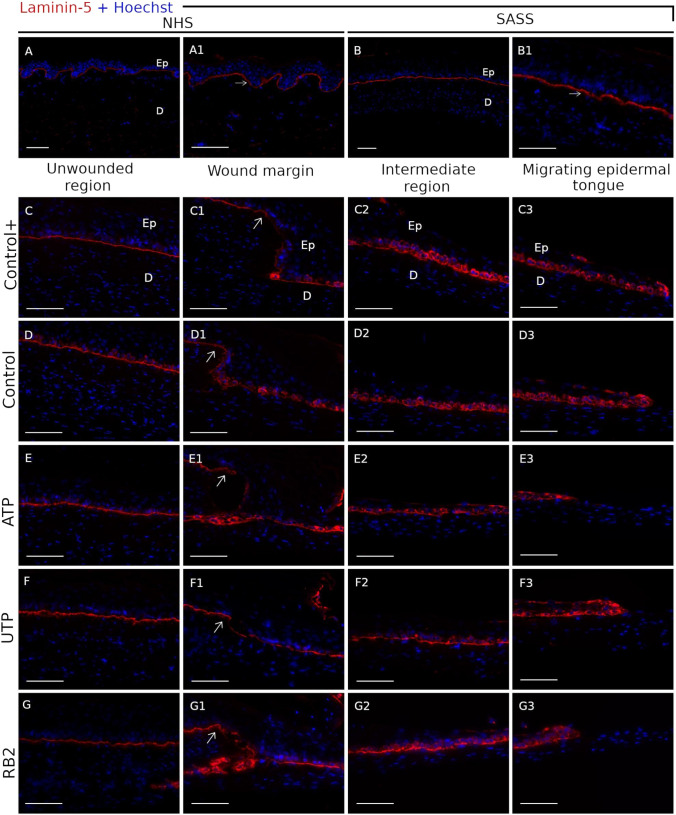

Expression of epidermal differentiation-specific protein markers, such as cytokeratin 10 (CK10), laminin-5, an important component of the basement membrane, and the proliferation marker, Ki67 were evaluated on the wounded reconstructed human skin. CK10 expression was restricted to the epidermal suprabasal layers on normal human skin, SASS and unwounded region of the wounded SASS (Fig. 3a–g). This expression was reduced in the wound margin in all the treatments (Fig. 3c1–g1). Laminin 5 formed a continuous line at the dermo-epidermal junction on normal human skin, SASS and in the unwounded region of the wounded SASS (Fig. 4a–g). From the wound margin, it was observed a keratinocyte cytoplasmic expression of laminin 5 in the basal layer, which was increased toward the migrating epidermal tongue (Fig. 4c1–g3). No change has been observed according to the treatments.

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence labeling of Cytokeratin 10. Expression of Cytokeratin 10 (CK10) (red) in normal human skin (NHS) (a) and the self assembled skin substitute (SASS), the dotted white lines indicate the basement membrane. As expected, the basal layers of the epidermis were unlabeled. The CK10 labeling is shown in the unwounded region and the wound margin (indicated by withe arrow) for the Control+ (c–c1), Control (d–d1), ATP (e-e1), UTP (f–f1) and RB2 (g–g1) treatments. The CK10 expression was unlabeled in the intermediate region and migrating epidermal tongue. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye (blue). Scale bars 100 μm

Fig. 4.

Laminin-5 expression in the wounded SASS. Laminin 5 (red) expression in the basement membrane between epidermis and dermis in the normal human skin (a–a1) and the SASS (b–b1) is shown. The higher nuclei staining with Hoechst in epidermis allows to detect the difference between the epidermis (Ep) and dermis (d) layers. The laminin 5 expression in the basement membrane of the unwounded region (c–g) and the wound margin (indicated by white arrows) (c1–g1) is exposed; the basal keratinocytes of the intermediate region (c2–g2) and migrating epidermal tongue (c3–g3) exhibit a cytoplasmic expression in all the treatments, Control+ (c–c3), Control (d–d3), ATP (e–e3), UTP (f–f3) and RB2 (g–g3). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye (blue). Scale bars 100 μm

The proliferation marker Ki67 was expressed in basal cells of the epithelium as expected on normal human skin, SASS and in the unwounded region of the wounded SASS (Fig. 5a–g). Moreover, a larger number of ki67 positive fibroblasts were observed from the wound margin to the migrating epidermal tongue (Fig. 4c1–g3). Ki67 positive cells were quantified in each section of epidermis and dermis. In the epidermis, the use of serum and additives in the medium (positive control) induced the greatest number of Ki67+ positive cells in all sections of the wound. The use of serum alone (without additive) greatly reduced the number of positive cells in unwounded skin and in the wound compared to the positive control. Regarding the treatments, the addition of UTP in the control medium (without additive) promoted a strong proliferation in the unwounded skin and in the wound which was not observed when using RB2 or ATP. The number of Ki67-positive cells induced by the UTP treatment was not statistically different from the number of cells obtained with the use of additives in the medium.

Fig. 5.

Expression of the proliferative marker Ki67 in keratinocytes and fibroblasts of the wounded reconstructed human skin. The Ki67 positive cells (green) in NHS (a–a1) and SASS (b–b1) are indicated. The dotted white lines indicate the basement membrane of the epidermis. The Ki67 expression is shown in all the treatments; Control+ (c–c3), Control (d–d3), ATP (e–e3), UTP (f–f3) and RB2 (g–g3) and all the regions of the wounded SASS; unwounded region (UR), wound margin (WM), intermediate region (IR) and migrating epidermal tongue (MET). Quantification of the percentage of Ki67+ cells in the epidermis (H) and dermis (I) in each section for the different treatments shows the highest percent of Ki67 positive cells in Control+ and UTP treatments. Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference versus Control+ group; Plus symbol (+) indicates significant a difference versus control group; and hashtag (#) indicates a significant difference versus the UTP group. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test for the treatments and unpaired t-test to compare the NHS versus the SAAS with no significant differences. (*, #, +p < 0.05), (**, ##p < 0.01). Graph bars represent the mean with SEM. SASS was produced from cells obtained from two different patients, N = 2, in duplicates. Scale bars 100 μm

In the dermis, the number of Ki67 positive cells increased in wounds, independently of the treatment. Again, addition of additives or UTP in the medium statistically increased the number of ki67 positive cells in the wound. In the wound margin of SASS treated with UTP there was the highest percentage of Ki67 positive fibroblasts, which was different from RB2. In the intermediate region and the migrating epidermal tongue the result was similar, but in this case, the differences were also in comparison to the control, ATP and RB2 treatments. No significant differences between the normal human skin and the SASS, in both epidermis and dermis were detected.

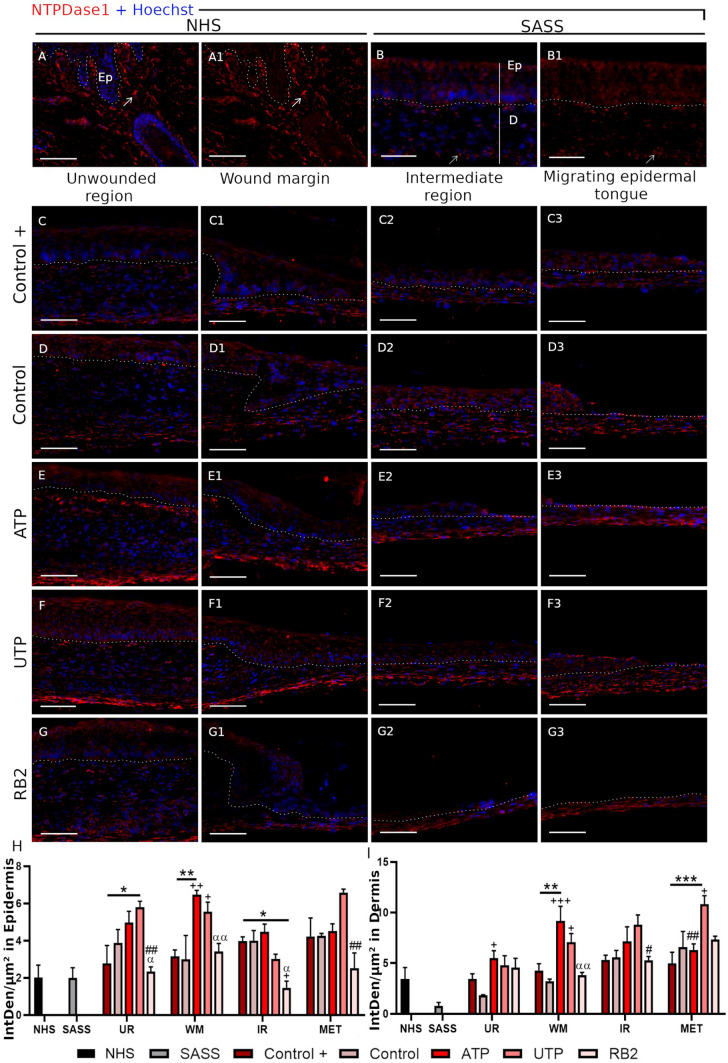

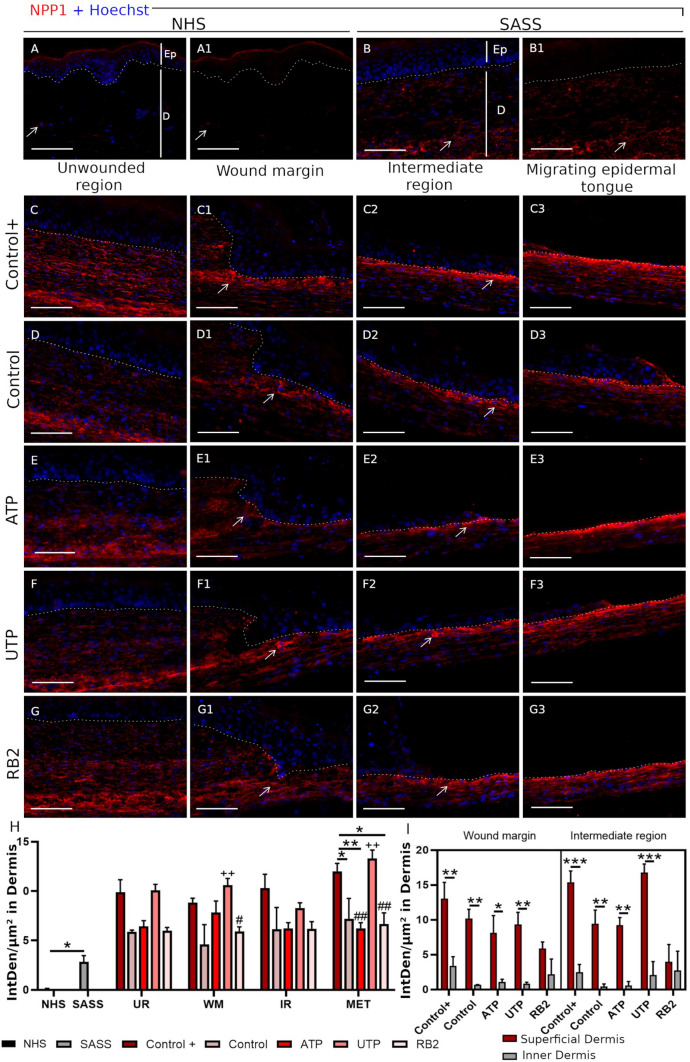

NTPDase1 and NPP1 expression in normal and reconstructed human skin

The NTPDase1 and NPP1 expressions were evaluated in the normal human skin, the SASS and the wounded SASS. In normal human skin and SASS, the NTPDase1 was mostly observed in dermal cells and epidermal cells (Fig. 6a–b1) while NPP1 was only expressed in the dermal part of the skin (Fig. 7a–b1). For both stainings, there was no immunolabeling when the respective pre-immune sera were used (Supplementary Figure 1A–B1 and C–D1).

Fig. 6.

NTPDase1 expression in normal and reconstructed human skin. Expression of the NTPDase1 in the normal human skin (a–a1) and in the Self-Assembled Skin Substitute, (b–b1) the positive expression in dermal cells are indicated (arrow). The dotted white lines indicate the basement membrane between the epidermis (Ep) and the dermis (d). The NTPDase1 expression was observed in keratinocytes of the SASS and wounded SASS and few positive NTPDase1 cells were observed in the NHS. NTPDase1 was also observed in all the regions of the wounded SASS: unwounded region (UR), wound margin (WM), intermediate region (IR) and migrating epidermal tongue (MET) and all the treatments: Control+ (c–c3), Control (d–d3), ATP (e–e3), UTP (f–f3) and RB2 (g–g3). Relative NTPDase1 fluorescence intensity (Integrated density/μm2) in Epidermis (h) and Dermis (i) The asterisk indicate the significant differences versus Control+ group, the plus symbol (+) indicate significant differences versus Control group, the hashtag (#) indicate significant differences versus the UTP group and the alpha (α) indicate significant differences versus the ATP group. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test for the treatments and unpaired t-test to compare the NHS versus the SAAS (*, +, α p < 0.05), (**, ##, ++, αα p < 0.01), (***p < 0.001). Graph bars represent the mean with SEM. SASS was produced from cells obtained from two different patients, N = 2, in duplicates. Scale bars 100 μm

Fig. 7.

NPP1 expression in normal and reconstructed human skin. The positive expression in fibroblasts in NHS (a–a1) and SASS (b–b1) is indicated (arrow). The dotted white lines indicate the basement membrane between the epidermis (Ep) and the dermis (D). NPP1 labeling was observed in fibroblasts from the wounded SASS in the Control+ (c–c3), Control (d–d3) and following ATP (e–e3), UTP (f–f3) and RB2 (g–g3) treatment and in all the regions of the wounded SASS: unwounded region (UR), wound margin (WM), intermediate region (IR) and migrating epidermal tongue (MET); we observed a higher intensity near the basement membrane in the wound margin and intermediate region, indicated by the white arrow. Relative NTPDase1 fluorescence intensity (Integrated density/μm2) in dermis (h) and superficial and inner part of the dermis (i) Significant differences versus the Control+ (*); Control (+); UTP treatment (#) and superficial versus inner dermis (*). Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test for the treatments and unpaired t-test to compare the NHS versus the SAAS (*, # < 0.05), (**, ## p < 0.01), (***p < 0.001). Graph bars represent the mean with SEM. SASS was produced from cells obtained from two different patients, N = 2, in duplicates. Scale bars 100 μm

During wound healing, NTPDase1 was observed in all regions of the wound, independently of the treatments in epidermis and dermis. By quantifying the fluorescence intensity, we identified a higher expression of NTPDase1 in dermis and epidermis following the ATP and UTP treatments, in comparison with both control and positive control. By contrast, NPP1 was not detected in epidermis during healing, but NPP1 was increased in the intermediate region and migrating epidermal tongue, after UTP treatment (Fig. 7h). Interestingly, we detected a higher NPP1 intensity in the superficial dermis, near to the basement membrane, in comparison with the inner dermis, in the wound margin and intermediate region (Fig. 7c–g3, i).

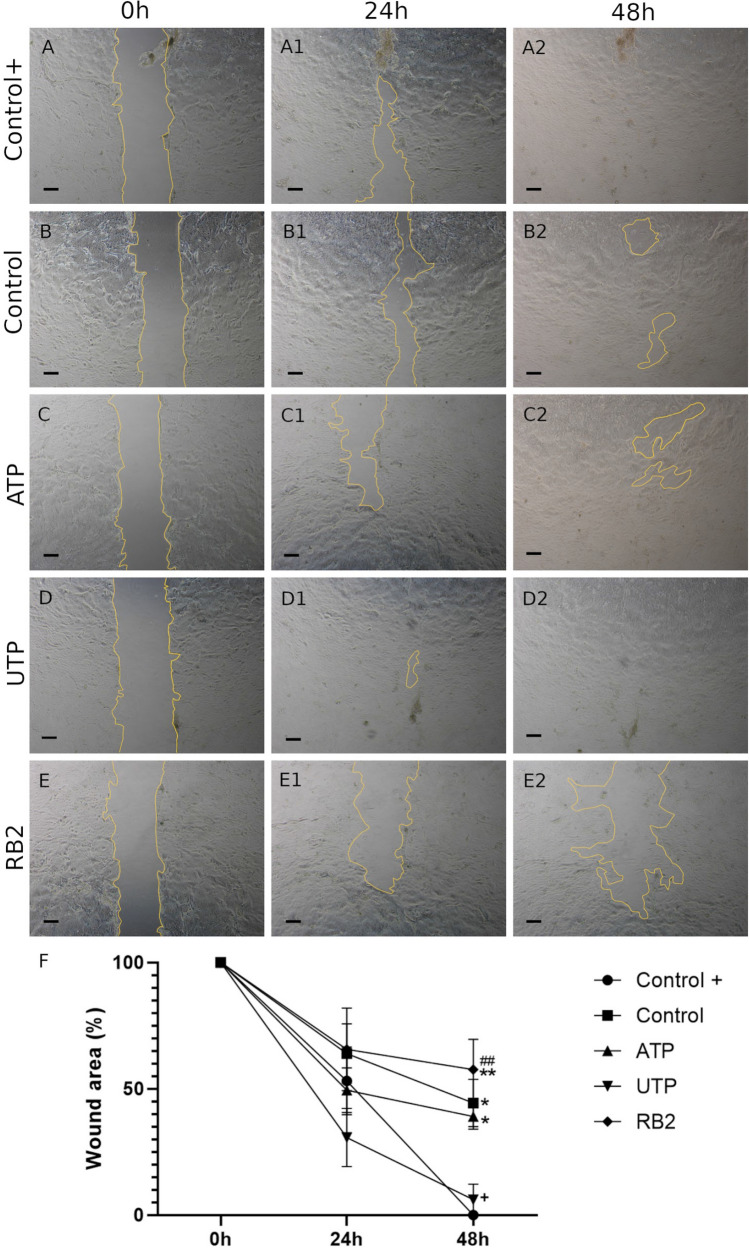

Scratch wound assay in primary human keratinocytes

The migration capabilities of primary human keratinocytes in contact with Control+, Control, ATP, UTP and RB2 were analyzed following scratch formation on confluent keratinocytes (Fig. 8a–e). Mitomycin C was added before the treatments to inhibit cell proliferation. After 24 h, among all the treatments, the UTP group showed best results (Fig. 8a1–e1, f). Complete closure of the scratch area was observed in Control+ and UTP groups in 48 h (Fig. 8a2–e2, f) whereas the other treatments did not stimulate migration.

Fig. 8.

Scratch wound assay in primary human keratinocytes. Migration of primary human keratinocytes at 0 h, 24 h and 48 h in presence of the treatments Control+ (a–a2), Control (b–b2), ATP (c–c2), UTP (d–d2) and RB2 (e–e2). Wound area percentage at each time point compared with each original wound area at time 0 h are shown. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test for the treatments. Significant differences versus the Control+ (*); Control (+); and UTP treatment (#); (*, + < 0.05), (**, ## p < 0.01). All values represent mean ± SEM, Primary human keratinocytes were obtained from two different patients, N = 2, in triplicates. Scale bar 250 μm

Discussion

Considering the need for more therapies to heal complex wounds and the role of the purinergic signaling in the skin, more information on these processes are necessary to establish future clinical applications, using the nucleotides potential for tissue regeneration. Therefore, in this study, we used the self-assembled skin substitutes (SASS), to study the effect of ATP, UTP and a P2Y receptor antagonist, Reactive Blue 2 (RB2), on a wound healing model.

Following the isolation of human skin fibroblasts, keratinocytes and their expansion in vitro, the self assembly approach allows the production of skin substitutes. They are very similar to the normal human skin, composed of a dermis, a functional basement membrane and an epidermis, without the use of any synthetic material (Beaudoin Cloutier et al. 2017). This wound healing model offers an accurate tool to compare, under standardized conditions, the effect of various factors on the rate of reepithelialization, by macroscopically following the wound closure (Laplante et al. 2001). Three days post-wounding, UTP treatment significantly accelerated wound closure, when compared to controls, whereas ATP and RB2 did not modify it.

The histological analysis of SASS and the unwounded region showed a well-structured epidermis from the stratum basale to the stratum corneum, produced by keratinocytes. Below there was an organized dermis, entirely produced from fibroblasts that increased the release of growth factors and extracellular matrix, by adding the ascorbic acid. The wound margin represented the limit of that differentiated epidermis above the dermis, since the stratum corneum was not produced in 3 days after wound in the neodermis. Therefore, the cytokeratin 10 expression was restricted to the epidermal suprabasal layers on SASS, unwounded region and wound margin, similar to the human skin. The unlabeled keratinocytes had an undifferentiated morphology and were located in the deep layers (Laplante et al. 2001). Accordingly, the migrating keratinocytes on the third dermal sheet, in the intermediate region and migrating epidermal tongue, were unlabeled for cytokeratin 10.

The basement membrane is essential for cohesion at the dermoepidermal junction and an important factor in successful healing. Also, the basement membrane participates in the regulation and anchoring of the stem cells (Lavoie et al. 2013). In SASS and unwounded region, the basement membrane, observed by the laminin 5 expression, formed a continuous line at the dermo-epidermal junction; similarly to the normal human skin, as expected. From the wound margin, it was observed a keratinocyte cytoplasmic expression of laminin 5 in the basal layer. It was increased toward the migrating epidermal tongue, since the deposition of laminin 5 over exposing dermal collagen in epidermal wounds is an early event in repair of the basement membrane (Nguyen et al. 2000).

Reepithelialization is a critical step in wound healing. Is the resurface of a wound with new epithelium and consists of both migration and proliferation of keratinocytes at the wound edges (Santoro and Gaudino 2005). The length of the migrating epidermal tongues, analyzed histologically in this study, showed an increase of the reepithelialization with UTP treatment. Therefore, a regenerative effect on wound healing after 3 days of treatment, meanwhile, a committed reepithelialization with RB2 treatment was observed. We confirmed these results observed in a 3D skin model, analyzing a scratch wound assay with primary human keratinocytes. As expected, UTP treatment showed the best results at 24 h, and similar results with the positive control in 48 h were observed. In agreement, similar results were obtained in corneal wound healing by Pintor et al. (2004), where the UTP treatment accelerated wound healing in the rabbit cornea, whereas purinoceptor antagonists, such as suramin and RB2, blocked the effect of UTP (Pintor et al. 2004). Jokela et al. (2017) explored the relationship between the UTP and hyaluronan synthase (HAS) metabolism in human HaCaT keratinocytes, in a temptative to explain the the rapid activation of hyaluronan metabolism, in response to tissue trauma, or ultraviolet radiation. They demonstrated, for the first time, that UTP strongly regulates HAS2 expression, leading to hyaluronan accumulation, providing an explanation for the rapid increase in hyaluronan synthesis detected after injury (Jokela et al. 2017).

Even though, no significative differences were observed in the wound closure area analyzed between the positive control (with additives) and the control, the presence of the positive control was important, as there was an increase in the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts in this group, as determined by the presence of ki67. Although the treatments with nucleotides were done in medium without the additives, the presence of UTP was capable to induce the increase in proliferation in both keratinocytes and fibroblasts.

In the wound microenvironment, keratinocytes will be exposed to ADP, ATP and UTP released from dead or damaged cells as well as from platelets and inflammatory cells. Our results showed that when SASS or keratinocytes were treated with RB2, there was a decrease in the proliferation and migration suggesting that the endogenous nucleotides have an effect on skin wound healing through the P2Y receptors. There are few studies in the literature showing that keratinocytes express specific receptors for these nucleotides. However, the extent to which the nucleotides ATP and UTP are differentially regulated and act as independent messengers through purinergic receptors in cells from healthy and damaged skins is still unknown (Boarder and Hourani 1998; Anderson and Parkinson 1997; Lazarowski et al. 2000; Dixon et al. 1999).

The expression of P2Y2 receptor was reported in basal and parabasal primary human keratinocytes by Greig et al. (2003). They suggested that P2 purinergic receptor agonists altered keratinocyte cell number. In addition, UTP and low concentrations of ATP caused an increase in cell number, probably due a direct proliferative effect on basal cells, via P2Y2 receptors (Greig et al. 2003). Likewise, Boucher et al. (2010) reported the involvement of the P2Y2 receptors in the epithelial injury response and cell migration of corneal epithelial cells (Boucher et al. 2010). Jin et al. (2014) using human fibroblast and a mice model showed that P2Y2 receptors, activated by ATP and UTP, have an important role in the skin wound healing process, in vitro and in vivo, by increasing cell proliferation, cell migration and the expression of extracellular matrix proteins. Thus, suggesting this receptor as a potential therapeutic target in chronic wound diseases (Jin et al. 2014).

P2Y2 is potently activated by both ATP and UTP, whereas human P2Y4 is activated by UTP. However, there are differences among species as the P2Y4 ortholog can also be activated by ATP (Brunschweiger and Muller 2006). Human P2Y6 receptors are preferentially activated by UDP (von Kügelgen and Wetter 2000), but in mice also by UDP (Kauffenstein et al. 2010). The expression and functionality of P2Y receptors involved in the regulation of proliferation of human keratinocytes and the HaCaT cell line was investigated. In both cell types there was the expression of P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 (Burrell et al. 2003). However, in primary human astrocytes when cells were cultured in the presence of calcium (200 mM and 1 mM) to mimic the differentiation, there was P2Y2 and P2Y4 downregulation. Although P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptor mRNA was expressed, only the P2Y2 receptor subtype was activated by ATP and UTP leading to intracellular calcium release and cell proliferation (Burrell et al. 2003). In addition, in situ hybridization studies showed that P2Y2 receptors were localized in the proliferative basal layer of the epidermis (Dixon et al. 1999). The actions of UTP observed in our study, improving the wound healing can be mediated by P2Y4 receptors as the ATP did not have any effects. However the participation of other P2Y receptors contributing to UTP proliferation can not be ruled out.

Burrell et al. (2003) showed that there was no response when treating human primary keratinocytes with 2MeSADP (P2Y1 agonist), ADP or UDP. Thus, suggesting that the P2Y1 and P2Y6 receptors, respectively, were not functional in this cell type (Burrell et al. 2003). The purinergic ectoenzyme NTPDase1 hydrolyzes nucleoside diphosphate and triphosphate equally. Thus, it is possible that UTP added to treat SASS can be hydrolyzed to UDP, which could in turn stimulate the P2Y6 receptor, promoting at least part of the observed results, considering that in the reconstructed skin model analyzed was composed also by dermal fibroblasts that express high levels of P2Y6 (Gendaszewska-Darmach and Kucharska 2011).

NTPDase1/CD39 can hydrolyze ATP and ADP to AMP, and UTP to UDP and UMP. This can reflect the higher intensity of this enzyme as observed after the ATP and UTP treatments in the 3D skin model. In agreement, the ATP exposure was shown to increase ectonucleotidase activity in a lineage of human epithelioid carcinoma cells (Wiendl et al. 1998). We identified the NTPDase1 expression in fibroblasts and keratinocytes of normal human skin and the reconstructed human skin. This enzyme is expressed on different immune cell types (Giuliani et al. 2020). Fausther et al. (2010) identified the NTPDase1 expression throughout the respiratory system, including superficial epithelia and fibroblasts (Fausther et al. 2010). However, Ho et al. (2013) observed low NTPDase1 levels in HACAT cells (Ho et al. 2013). Otherwise, NTPDase1/CD39 was identified to mark normal murine fibroblasts from healthy tissues (Agorku et al. 2019). Moreover, fibroblasts may express a number of mesenchymal markers (LeBleu and Neilson 2020). We previously reported the ENTPDase1 and ENPP1 gene expression in mesenchymal stem cells isolated from skin and cornea. Dermal mesenchymal stem cells expressed higher levels of ENTPDase1, leading to adenosine release that could be associated with the immunomodulatory properties of these cells (Naasani et al. 2017).

Recently, Peng et al. (2021) investigated the correlation between the NTPDase1 expression level and the degree of skin graft injuries in a mice model. They found a negative correlation showing that the higher the expression of the NTPDase1, the lower the concentration of extracellular ADP, proliferation and activation of macrophages and B cells activity. Thus, the activity of NTPDase1 was able to decrease the degree of skin graft injuries, providing a foundation for new studies investigating the use of NTPDase1 to alleviate organ damage, during the acute Antibody-mediated rejection (Peng et al. 2021). Therefore, NTPDase1 expression could be associated with immunogenic events in tissue regeneration. Accordingly, Mizumoto et al. (2002) reported the modulatory roles in inflammation and immune responsiveness of NTPDase1 on mice skin, as responsible for the Langerhans cells ecto-NTPDase activity and the augmented inflammatory responses in skin CD39−/− mice (Mizumoto et al. 2002).

Extracellular ATP can be directly hydrolysed to AMP by NPPs, as reviewed in Giuliani et al. (2020). The expression and role of NPP1 is still unknown in tissue regeneration. No labeled keratinocytes in normal human skin and in the reconstructed human skin were identified. This observation is in accordance with the work of Chourabi et al. (2018), which detected ENPP1 transcript in primary human fibroblasts and melanocytes but not in keratinocytes (Chourabi et al. 2018). A pathogenic role of this enzyme was reported observing its overexpression in cultured skin fibroblasts from insulin-resistant humans (Goldfine et al. 1999). Moreover, NPP1 expression has been reported to be increased in neural brain tumors (Lee 2015). Thus, the NPP1 overexpression could be associated with pathological events or at least, when cells are not in homeostasis state, as observed during wound healing.

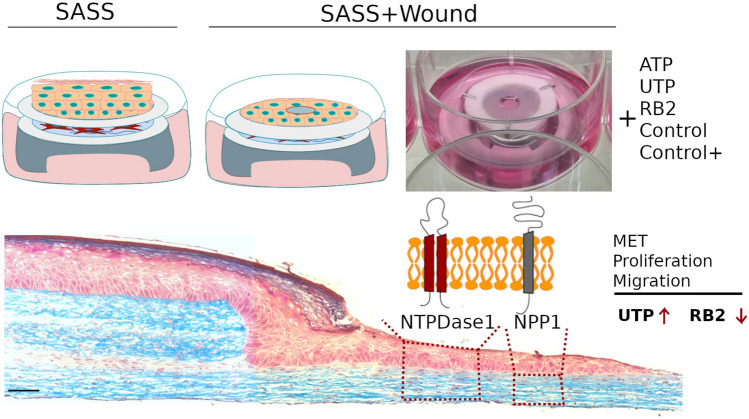

In conclusion, as a novelty, we have studied the role of two important nucleotides of the purinergic signaling, ATP and UTP, in a reconstructed human skin model. UTP treatment showed a therapeutic effect on wound healing, improving the migration and proliferation of human keratinocytes, an effect that could be blocked by the antagonist of P2Y purinergic receptors, Reactive Blue 2 (RB2). In addition, the expression of the enzymes NTPDase1 and NPP1 was observed for the first time in a reconstructed human skin model, showing their modulation in the wounded SASS regions (Fig. 9). Nevertheless, new experiments will still be necessary to understand how the purinergic signaling is involved in the skin physiology and wound healing process.

Fig. 9.

Schematic representation of the UTP role in a reconstructed human skin model. UTP treatment, the wounded SASS showed an increase in the reepithelialization, migration and in proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, different from RB2, when a committed reepithelialization was observed. We also identified the presence of the ectoenzymes NTPDase1, in keratinocytes and fibroblasts and NPP1 in fibroblasts along the wound, suggesting their involvement in wound healing

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Research Center CHU de Québec-Université Laval for the support, specially to Julie Pelletier, Israël Martel, Guillaume Martin, Emilie Attiogbe, Lucíola Barcelos, Angela Piaceski, Syrine Arif and Sébastien Larochelle.

Funding

MRW is recipient of research productivity fellowship (PQ1D) from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – Brasil (CNPq); LISN is recipient of fellowship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. This study was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul—Brasil (FAPERGS/CAPES 06/2018-Programa de Internacionalização da pós-graduação no RS (19/2551-0000679-9) to MW and VM; JS, by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC; RGPIN-2016-05867 (JS) and RGPIN-2019-06500 (VM)) and Quebec Cell, Tissue and Gene Therapy Network (ThéCell) (VM).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Véronique J. Moulin and Márcia Rosângela Wink have shared senior authorship

References

- Abbracchio MP, et al. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58(3):281–341. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agorku DJ, et al. CD49b, CD87, and CD95 are markers for activated cancer-associated fibroblasts whereas CD39 marks quiescent normal fibroblasts in murine tumor models. Front Oncol. 2019;9:716. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CM, Parkinson FE. Potential signalling roles for UTP and UDP: sources, regulation and release of uracil nucleotides. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18(10):387–392. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(97)01106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin Cloutier C, et al. In vivo evaluation and imaging of a bilayered self-assembled skin substitute using a decellularized dermal matrix grafted on mice. Tissue Eng A. 2017;23(7–8):313–322. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Epidermal stem cells of the skin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher I, et al. The P2Y2 receptor mediates the epithelial injury response and cell migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299(2):C411–C421. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00100.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunschweiger A, Muller C. P2 receptors activated by uracil nucleotides—an update. Curr Med Chem. 2006 doi: 10.2174/092986706775476052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(2):659–797. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purine and pyrimidine receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2007;64(12):1471–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. The therapeutic potential of purinergic signalling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Knight GE, Greig AVH. Purinergic signaling in healthy and diseased skin. J Investig Dermatol. 2012;132(3 Pt 1):526–546. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Knight GE, Greig AVH. Purinergic signaling in healthy and diseased skin. J Investig Dermatol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell HE, et al. Human keratinocytes express multiple P2Y-receptors: evidence for functional P2Y1, P2Y2, and P2Y4 receptors. J Investig Dermatol. 2003;120(3):440–447. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury S, Das A. Advances in generation of three-dimensional skin equivalents: pre-clinical studies to clinical therapies. Cytotherapy. 2021;23(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chourabi M, et al. ENPP1 mutation causes recessive cole disease by altering melanogenesis. J Investig Dermatol. 2018;138(2):291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commandeur S, et al. Anin vitrothree-dimensional model of primary human cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Exp Dermatol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann J, et al. A three-dimensional skin equivalent reflecting some aspects ofin vivoaged skin. Exp Dermatol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/exd.12866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon CJ et al (1999) Regulation of epidermal homeostasis through P2Y2 receptors. Br J Pharmacol 127(7):1680–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fausther M, et al. Cystic fibrosis remodels the regulation of purinergic signaling by NTPDase1 (CD39) and NTPDase3. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298(6):L804–L818. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00019.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Muñoz C, et al. Restraint of human skin fibroblast motility, migration, and cell surface actin dynamics, by Pannexin 1 and P2X7 receptor signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):7. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendaszewska-Darmach E, Kucharska M. Nucleotide receptors as targets in the pharmacological enhancement of dermal wound healing. Purinergic Signal. 2011;7(2):193–206. doi: 10.1007/s11302-011-9233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain L, et al. Autologous bilayered self-assembled skin substitutes (SASSs) as permanent grafts: a case series of 14 severely burned patients indicating clinical effectiveness. Eur Cell Mater. 2018;36:128–141. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v036a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani AL, Sarti AC, Di Virgilio F. Ectonucleotidases in acute and chronic inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:619458. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.619458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfine ID, et al. Role of PC-1 in the etiology of insulin resistance. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999 doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig AVH, et al. Purinergic receptors are part of a functional signaling system for proliferation and differentiation of human epidermal keratinocytes. J Investig Dermatol. 2003 doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner GC, et al. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DS, et al. A novel fully humanized 3d skin equivalent to model early melanoma invasion. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(11):2665–2673. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C-L, et al. Ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 2 modulates local ATP-induced calcium signaling in human HaCaT keratinocytes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e57666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, et al. From purines to purinergic signalling: molecular functions and human diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):162. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00553-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean J, Soucy J, Pouliot R. Effects of retinoic acid on keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation in a psoriatic skin model. Tissue Eng A. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen EC. Quantitative analysis of histological staining and fluorescence using ImageJ. Anat Rec. 2013;296(3):378–381. doi: 10.1002/ar.22641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, et al. P2Y2R activation by nucleotides promotes skin wound-healing process. Exp Dermatol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/exd.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokela T, et al. Human keratinocytes respond to extracellular UTP by induction of hyaluronan synthase 2 expression and increased hyaluronan synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(12):4861–4872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.760322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffenstein G, et al. NTPDase1 (CD39) controls nucleotide-dependent vasoconstriction in mouse. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85(1):204–213. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukulski F, et al. Comparative hydrolysis of P2 receptor agonists by NTPDases 1, 2, 3 and 8. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1(2):193–204. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-6217-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante AF, et al. Mechanisms of wound reepithelialization: hints from a tissue-engineered reconstructed skin to long-standing questions. FASEB J. 2001;15(13):2377–2389. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0250com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larouche D, et al. Improved methods to produce tissue-engineered skin substitutes suitable for the permanent closure of full-thickness skin injuries. Biores Open Access. 2016;5(1):320–329. doi: 10.1089/biores.2016.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie A, et al. Human epithelial stem cells persist within tissue-engineered skin produced by the self-assembly approach. Tissue Eng A. 2013;19(7–8):1023–1038. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC Harden TK (2000) Constitutive release of ATP and evidence for major contribution of ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase and nucleoside diphosphokinase to extracellular nucleotide concentrations. J Biol Chem 275(40):31061–31068 [DOI] [PubMed]

- LeBleu VS, Neilson EG. Origin and functional heterogeneity of fibroblasts. FASEB J. 2020;34(3):3519–3536. doi: 10.1096/fj.201903188R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S-Y (2015) Identification and pharmacological characterization of nucleotide pyrophosphatase, phosphodiesterase 1 (NPP1) inhibitors

- Martin P. Wound healing–aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276(5309):75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumoto N, et al. CD39 is the dominant Langerhans cell–associated ecto-NTPDase: modulatory roles in inflammation and immune responsiveness. Nat Med. 2002 doi: 10.1038/nm0402-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin VJ. Three-dimensional model of hypertrophic scar using a tissue-engineering approach. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2299:419–434. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1382-5_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naasani LIS, et al. Extracellular nucleotide hydrolysis in dermal and limbal mesenchymal stem cells: a source of adenosine production. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(8):2430–2442. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naasani LIS, et al. Comparison of human denuded amniotic membrane and porcine small intestine submucosa as scaffolds for limbal mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12015-018-9819-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naasani LIS, et al. Decellularized human amniotic membrane associated with adipose derived mesenchymal stromal cells as a bioscaffold: physical, histological and molecular analysis. Biochem Eng J. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2019.107366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen BP, Gil SG, Carter WG. Deposition of laminin 5 by keratinocytes regulates integrin adhesion and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(41):31896–31907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, et al. Mechanism of graft damage caused by NTPDase1-activated macrophages in acute antibody-mediated rejection. Transpl Proc. 2021;53(1):436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2020.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintor J, et al. UTP and diadenosine tetraphosphate accelerate wound healing in the rabbit cornea. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt J Br Coll Ophthalmic Opticians. 2004;24(3):186–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2004.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx S, et al. Stem cells of the skin and cornea: their clinical applications in regenerative medicine. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2011;16(1):83–89. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32834254f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson SC, Sévigny J, Zimmermann H. The E-NTPDase family of ectonucleotidases: structure function relationships and pathophysiological significance. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2(2):409–430. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M, et al. Wound healing: a cellular perspective. Physiol Rev. 2019 doi: 10.1152/physrev.00067.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro MM, Gaudino G. Cellular and molecular facets of keratinocyte reepithelization during wound healing. Exp Cell Res. 2005;304(1):274–286. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(10):738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley JR, et al. Detection of basement membrane zone antigens during epidermal wound healing in pigs. J Investig Dermatol. 1981;77(2):240–243. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12480082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veith AP, et al. Therapeutic strategies for enhancing angiogenesis in wound healing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;146:97–125. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig K, et al. Advances in skin regeneration using tissue engineering. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 doi: 10.3390/ijms18040789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kügelgen I, Wetter A. Molecular pharmacology of P2Y-receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362(4–5):310–323. doi: 10.1007/s002100000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinmüllner R, et al. Organotypic human skin culture models constructed with senescent fibroblasts show hallmarks of skin aging. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 2020;6:4. doi: 10.1038/s41514-020-0042-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N, et al. An in vivo model of melanoma: treatment with ATP. Purinergic Signal. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiendl HS, Schneider C, Ogilvie A. Nucleotide metabolizing ectoenzymes are upregulated in A431 cells periodically treated with cytostatic ATP leading to partial resistance without preventing apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1998;1404(3):282–298. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(98)00040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y et al (2010) Development of a three-dimensional human skin equivalent wound model for investigating novel wound healing therapies. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 16(5):1111–1123 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann H. Ectonucleotidases: some recent developments and a note on nomenclature. Drug Dev Res. 2001 doi: 10.1002/ddr.1097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.