Abstract

In recent years, biomedical research efforts aimed to unravel the mechanisms involved in motor neuron death that occurs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). While the main causes of disease progression were first sought in the motor neurons, more recent studies highlight the gliocentric theory demonstrating the pivotal role of microglia and astrocyte, but also of infiltrating immune cells, in the pathological processes that take place in the central nervous system microenvironment. From this point of view, microglia-astrocytes-lymphocytes crosstalk is fundamental to shape the microenvironment toward a pro-inflammatory one, enhancing neuronal damage. In this review, we dissect the current state-of-the-art knowledge of the microglial dialogue with other cell populations as one of the principal hallmarks of ALS progression. Particularly, we deeply investigate the microglia crosstalk with astrocytes and immune cells reporting in vitro and in vivo studies related to ALS mouse models and human patients. At last, we highlight the current experimental therapeutic approaches that aim to modulate microglial phenotype to revert the microenvironment, thus counteracting ALS progression.

Keywords: amytrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Astrocyctes, immune cell, inflammation, microglia

1. Mechanisms of neurodegeneration in ALS

ALS is the most common adult-onset motor neuron disease, affecting the upper and lower motor neurons (MN) in the brain and spinal cord. People with ALS develop muscle weakness and atrophy, leading to paralysis and death from neuromuscular respiratory failure, within 3 to 5 years after onset. Riluzole and the free-radical scavenger edaravone are the only treatments approved to treat ALS patients, which act on survival and rate of progression, respectively.

Traditionally, ALS has been classified as either the sporadic or familial form. Sporadic ALS (sALS) is the most common form, accounting for around 90% of all cases (1–5). Familial, or inherited, ALS (fALS) runs in families and accounts for the remaining 5-10% of cases. Mutations in several genes have been implicated in fALS and contribute to the development of sALS (e.g. superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), fused in sarcoma (FUS), TAR DNA binding protein (TARDBP) and chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) (6–8). Proteins encoded by these genes are involved in several aspects of MN function and in ALS pathogenesis, including protein homeostasis, axonal transport, DNA repair, RNA metabolism, vesicle transport, inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and glial cell function (9–11). In 1994, Gurney et al. developed the first mouse model of ALS, a transgenic model that over-expressed the ALS-associated mutant SOD1G93A and recapitulate some of the key clinical features of human ALS (12). These mice showed evident progressive motor abnormalities and paralysis, microglia acquire an inflammatory phenotype affecting MN death, and myeloid cells expressing mutated SOD1 promote neurotoxicity (8, 13, 14). In another ALS mouse model based on TDP-43 mutations, the TDP-43A315T mice showed pathological aggregates of ubiquitinated proteins in specific neurons and reactive gliosis, with the loss of both upper and lower MNs (15, 16). Abnormal expansion of an intronic hexanucleotide GGGGCC (G4C2) repeat of the C9orf72 gene is ALS’s most frequently reported genetic cause (17–20). Several transgenic mouse models containing the full-length C9orf72 gene show decreased survival, paralysis, muscle denervation, MN loss, and cortical neurodegeneration (21).

Despite the advance of knowledge of the ALS pathogenesis, most of the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in the progression and development of the disease remain largely unexplored. Recently, a majority of the evidence indicates that ALS is a non-neuronal-autonomous disease (1, 2, 13). Indeed, in this scenario, glia and immune cells build up a complex regulatory network involved in ALS disease, exerting both neurotoxic and neuroprotective effects on neurons. In this review, we summarize the role of non-neuronal cells in ALS pathology, with a particular focus on microglia interplay with astrocytes and peripheral immune cells that orchestrates the ALS microenvironment. We discuss the current therapeutic approaches that aim to modulate microglial crosstalk with non-neuronal cells, and finally look to the future of new therapeutic trials.

2. Microglial functions in health and disease

Microglia, which represent ~5–12% of the Central Nervous System (CNS) cells, are the resident macrophages of the CNS (22, 23), that originate from myeloid precursor cells which enter into the CNS during embryogenesis (24), becoming independent self-renewing population (25, 26). The general definition of microglial role describes them as able to perform three essential functions: sensing their environment, maintaining physiological homeostasis, and protecting from self and exogenous stimuli. Microglia are able to adopt a plethora of phenotypes, depending on the surrounding environment, which can differ in the healthy CNS and in various disease states (27–30). Recent in vivo imaging studies clearly demonstrate that microglial thin processes continually explore and sample the local environment at steady state (31, 32). Consistently, in the healthy CNS, microglia are necessary for proper brain development, providing trophic support to neurons, removing apoptotic cell debris, regulating neuronal and synaptic plasticity, developmental myelination, and tissue regeneration (33–37). In several pathological conditions, microglia lose their homeostatic molecular signature, resulting in rapid modification of their morphology, transcriptional profile, and phagocytic activity, acquiring a pro-inflammatory profile (38–44); the persistent inflammation can lead to neurotoxicity, and ultimately to neurodegeneration (45–47). Microglia have also been described as active participants in host defense against pathogens and protein aggregates, such as β-Amyloid (Aβ), mutant huntingtin, prions (PrPsc), α-synuclein, oxidized or SOD1 (48–50). In response to CNS insults, microglia initiate a defense program to restore brain homeostasis, through different pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including toll-like receptors (TLRs), scavenger receptors (SRs), and complement receptor 3 (CR3) (51–58). Furthermore, neurotoxicity dysregulates microglial immunological checkpoints (such as Trem2 and CX3CR1) that normally prevent their overreaction and may help to control inflammation (52). Dysregulation of these pathways increases the risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and ALS (59). Dysregulation of the host-defense pathway further, may also be caused by mutations in specific genes, such as Trem2, HTT, and TDP43, further, resulting in an inflammatory response and neuronal damage (60–62).

2.1. Microglia in ALS

Evidence that detrimental microglia contribute to sustaining the inflammation in ALS is observed in imaging studies in patients with ALS, human post-mortem samples, and rodent models of ALS (63–65). Microglia increase the expression of CD14, CD18, SR-A, and CD68 in ALS spinal cord, and CD68+ microglial cells are detected in close proximity to MNs (66), and in the brain of ALS patients using Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging (67, 68). Notably, microglia modify their phenotype with disease progression: adult microglia isolated from ALS mouse models at disease onset show a protective/anti-inflammatory phenotype, while microglia isolated from end-stage disease are toxic/pro-inflammatory (69–74). Consistently, in familial ALS (fALS) patients with SOD1 mutations, and in the SOD1-ALS mouse models, microglia affect MN death (75) and promote neurotoxicity (76), as well as regulate the feeding behavior and overall metabolism (77). Microglial-mediated MN death in ALS occurs through an NF-κB-dependent mechanism (75) and by secreting reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α) (78, 79). Although a number of studies are in line with the neuroinflammatory and neurotoxic microglial role observed in SOD1 mutated ALS patients and mouse models (8, 13, 14), the functional role of microglia in familial ALS or mouse models with mutated TDP-43 is not clear. In post-mortem human brain tissue from ALS patients and mouse models expressing mutated TDP43, were observed aggregates of ubiquitinated proteins in MNs, astrocytes and microglia, loss of both upper and lower MN and intestinal dysmotility that could induce premature death (15). On the contrary, the suppression of mutated human(h) TDP-43 protein in neurons, dramatically increased the microglial proliferation and changed their morphology and phagocytic activity against neuronal hTDP-43 (15). The partial depletion of microglia using PLX3397, a CSF1R and c-kit inhibitor, failed to recover motor functions in hTDP-43 mice, revealing an important neuroprotective role for microglia (80).

Recent work showed that C9orf72 expression is highest in myeloid cells, and loss of function of the C9ORF72 protein in mice disrupts microglial function and may contribute to neurodegeneration in C9orf72 expansion patients (18, 20, 81–87). Other disease mechanisms that occur in the ALS/FTD with C9orf72 gene mutation include a gain of toxicity mediated through either the RNA itself (88, 89) and/or the translation of aberrant dipeptide repeat (DPR) proteins by a non-canonical translation mechanism called repeat associated non-AUG dependent (RAN) translation (90, 91). Immunoreactive microglia and upregulation of inflammatory pathways have been confirmed in patients with mutated C9orf72 and correlate with rapid disease progression (87). Anyway, since most C9orf72 mouse models do not show ALS motor symptoms, neurodegeneration, or inflammatory response, it is difficult to determine the relationship between C9orf72-specific molecular pathology and ALS.

3. Microglial dialogue with non-neuronal cells in ALS

In the CNS, non-neuronal cells play crucial homeostatic functions both in health and diseases. The involvement of these cells in the pathophysiology of ALS is being increasingly characterized. Microglia crosstalk with peripheral immune cells and astrocytes to exert either neuroprotective or adverse effects through a broad range of cell-to-cell interactions.

3.1. Microglia – Astrocytes crosstalk

Similar to microglia, during ALS progression, astrocytes adopt neurotoxic properties which actively contribute to disease pathogenesis (92). In fact, both in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that in ALS mouse models, astrocytes with mutated mSOD1 protein exert neurotoxic effects on motor neurons, by releasing pro-inflammatory factors (93). Moreover, reactive astrocytes were described in the post-mortem CNS tissue obtained from ALS patients (94–96). This finding was confirmed further in vivo via diagnostic imaging using PET scanning demonstrating cerebral white matter and pontine astrogliosis in ALS patients (97).

In recent years, the crosstalk between astrocytes and other non-neuronal cells has been studied in more detail. The astrocytic transition from neuroprotective to neurotoxic was accompanied by a shift in microglial phenotype, suggesting that astrocytes may be important regulators of microglia activation and neuroinflammation in ALS (98). To date, several studies demonstrated that the detrimental microglia shape astrocyte phenotype in ALS driving disease progression. Both in human and mouse ALS tissues it was found the presence of neurotoxic reactive (A1-like) astrocytes since the early phase of the disease (92, 99–101). Moreover, microglia modify their phenotype as the disease progression: indeed, adult microglia isolated from ALS mouse models at disease onset show a protective/anti-inflammatory phenotype, while microglia isolated from end-stage disease are toxic/pro-inflammatory (67–72).

However, controversial results have been obtained on which cell population, between microglia and astrocytes, acquires a pro-inflammatory/neurotoxic phenotype during ALS progression. Indeed, Alexianu et al. reported that microglia activation precedes astrocyte reactivity (102). On the contrary, another study suggested that astrogliosis is present since the early symptomatic stage, while prominent microgliosis is only evident at the late phase (103).

Astrocytes have been shown to shape the microglial phenotype according to disease stage, modulating neuroprotective and neurotoxic functions in the pre-symptomatic and symptomatic phases of ALS, respectively (98). In the SOD1G93A ALS mouse model, astrocytic NF-κB activation drove microglial proliferation and leukocyte infiltration in the CNS (98). This response was initially beneficial by prolonging the pre-symptomatic phase, but it became detrimental in the symptomatic phase, accelerating disease progression. Specifically, in the pre-symptomatic phase astrocytic NF-κB activation in SOD1 mouse models induced a Wingless-related integration site (Wnt)-dependent anti‐inflammatory microglial response via nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta (IKK2), resulting in neuroprotective effects on motor neurons which translated into a delay of motor symptoms (98). However, in the symptomatic phase, NF-κB activation in astrocytes promoted pro‐inflammatory microglial responses (via CD68, TGF‐β, TNF‐α) which accelerated disease progression (98). A recent study indicated astrocytic TGF-β1 as a major molecule modulating microglial phenotype toward detrimental one (104). Astrocyte-specific overproduction of TGF-β1 in SOD1G93A mice interfered with the neuroprotective effects of microglia during the pre- and early symptomatic stages and accelerated disease progression in a non-cell-autonomous manner. This interference resulted in reduced production of neurotrophic factors from microglia and a reduced number of CNS infiltrating T cells. Consistently, the expression levels of endogenous TGF-β1 in SOD1G93A mice negatively correlated with overall life expectancy, while the administration of a TGF-β signaling inhibitor extended it (104). These findings raise TGF-β1 to an important determinant of disease progression in ALS.

On the other hand, many pieces of evidence suggest that the activation of microglia precedes the reactivity of astrocytes in ALS (105). Brites and colleagues demonstrated that microglia respond earlier than astrocytes to cell stress or damage by activating NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, thus leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL-1β) (105). These cytokines were shown to exert an inhibitory effect on Cx-43 expression, the main constitutive protein of astrocytes’ gap junctions, therefore hampering communication between astrocytes, and possibly interfering with their neuroprotective role (106). In addition, cell–cell contacts and microglial-derived soluble mediators are necessary for astrocytes to fully respond to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) insult and Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) ligation (11413), suggesting that microglia may exert a permissive effect on astrocyte pro-inflammatory activation. Liddelow et al. demonstrated that the microglial derived-pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1α, TNFα and complement component C1q42 are necessary and sufficient to induce pro-inflammatory astrocytes in mice (92). Consistently, a triple knock-out of these factors in IL-1α−/− TNFα−/−C1qa−/− SOD1G93A mice led to a drastic reduction in the number of reactive astrocytes, improving lifespan and delaying motor neuron loss and disease progression (92). This finding further supports the hypothesis of a microglia-to-astrocyte polarization.

Since an intimate interaction/communication between microglia and astrocytes occurs in ALS, a better understanding of their crosstalk could help to define potential therapeutic strategies targeting the glia in ALS.

3.2. Microglia – Natural killer cells crosstalk

NK cells contribute to ALS progression by interacting with CNS resident cells and peripheral immune cells. Increased numbers of NK cells have been found in the peripheral blood and CNS of ALS patients (107), and a rich infiltrate of NK cells has been described in the CNS of SOD1G93A mouse models (5). The NK cells - microglia crosstalk has been recently characterized, highlighting the importance of this interaction in the pathogenesis of ALS. Indeed, in NK cell-depleted hSOD1G93A and TDP43A315T microglia acquired a typical neuroprotective morphology, covering a wider parenchymal region and increasing the branches number (108). Moreover, NK cell-depleted hSOD1G93A mice showed a reduction in microgliosis, indicated as the number of microglia in the ventral horns of the spinal cord (108). In the absence of NK cells, microglia reduced the expression of genes associated to a pro-inflammatory phenotype, including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, with the simultaneous increase of expression of the anti-inflammatory (Chil3, Arg-1, and TGF-β), antioxidant (Msod1) and neuroprotective (P2yr12, Trem2, Kcnn4, Bdnf, IL-15) markers (108). The molecular link that drives the crosstalk between microglia and NK cells in ALS is the IFN-γ produced by infiltrated NK cells during the pre-symptomatic stage of disease. Accordingly, the IFN-γ immunodepletion (via IFN-γ-blocking antibody XMG1.2 administration) had consequences similar to NK cell depletion on microglial phenotype, switching them toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype (108). Lastly, this NK cell-mediated modulation of microglia resulted in an increased number of motor neurons in the ventral horn of spinal cord, and affected survival and onset time both in SOD1G93A and TDP43A315T mouse models (108), These results were further validated in an elegant study (109) exploiting Natalizumab, a blocking antibody for the α4 integrin (anti-VLA-4) (110, 111), to reduce the transfer of peripheral immune cells to the CNS of the hSOD1G93A ALS mouse model. In the lumbar spinal cord of Natalizumab-treated mice was found a reduced number of NK cells and, accordingly, microglial cells reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory markers (IL-6, IL-1β and tnf-α), and IFN-γ level was significantly reduced compared to vehicle-treated hSOD1G93A mice (108). However, Natalizumab treatment showed more effects on the modulation of the inflammation in the ALS microenvironment, suggesting a more complex scenario due to the role of different peripheral immune cells infiltrated in the CNS. Overall, these results point toward the importance of microglia-NK cells crosstalk modulation to reduce motor neuron loss in ALS.

3.3. Microglia - T lymphocytes crosstalk

Activated T cells are present in the CNS at a steady state to perform immunological surveillance (112) and provide immunological responses that are modulated by cell to cell signaling (113). Infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes has been documented in the brain and spinal cord of ALS patients (114, 115). Specifically, perivascular and intraparenchymal CD4+ helper T cells were found to surround degenerating corticospinal tracts, while ventral horns were enriched with both CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. The lymphocytic infiltration did not correlate with the rate of progression or stage of the disease in ALS patients (115); on the contrary, in transgenic mice expressing mutant SOD1G93A, the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells infiltrating the spinal cord increased as the disease progressed (116, 117). Multiple levels of evidence suggest that CD4+ helper T cells exert neuroprotective functions, especially in the initial phases of the disease process (116, 118), while CD8+ cytotoxic T cells present at later phases of the disease are possibly neurotoxic (119, 120). T cell functional profiles are, at least in part, shaped by a complex dialogue with microglia and neurons, as explained below.

3.3.1. Microglia - CD4+ T lymphocytes crosstalk

CD4+ T cells comprise multiple functionally distinct cell populations that regulate different functions, classified as Th1, Th2, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and Th17 cells (121). Although the role of CD4+ T cells in ALS remains controversial, the putatively protective effect of these cells on MNs is widely accepted (122–124). A major insight into the role of CD4+ T cells came from Beers & al., who bred immunodeficient mice lacking functional lymphocytes or functional CD4+ T cells with mSOD1G93A transgenic mice and performed selective reconstitution experiments with bone marrow transplants (116). The lack of functional CD4+ T lymphocytes resulted in a faster disease progression characterized at the molecular level by the upregulated expression of pro-inflammatory functional markers like NOX2 and pro-inflammatory cytokines, while reconstitution of CD4+ T lymphocytes prolonged survival and inhibited the acquisition of pro-inflammatory phenotype in microglia (116). The absence of functional CD4+ T cells in mSOD1G93 mice reduced the mean survival time, supporting the neuroprotective role of these lymphocytes. The fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1), a chemokine receptor expressed by microglia, monocytes, dendritic cells, and subsets of T cells, was involved in microglial neurotoxicity (125), and consistently, was reduced in mice lacking CD4+ T cells and increased following bone marrow reconstitution (125).

Within the CD4+ T lymphocyte subsets, endogenous Tregs are particularly associated to neuroprotection in ALS, with a time-specific effect (122, 123). Tregs were found to be increased in spinal cords of mSOD1 mice after disease onset, accompanied further by increased expression of IL-4 and higher number of neuroprotective/anti-inflammatory microglia (122). During the progression of the disease, there was a loss of Forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) expression in Tregs, with a concomitant reduction of IL-4 level (122). Passive transfer of Tregs from donor mSOD1G93A mice in the early phase of the disease, sustained IL-4 levels and anti-inflammatory microglia, delaying the onset of symptoms and increasing the survival of recipient mSOD1G93A mice (116, 122).

In ALS patients, neuroinflammation can be attributed to the impaired suppressive function of Tregs in addition to their decreased numbers (123, 126). Indeed, mutated SOD1 Tregs were less effective in suppressing effector T cells (Teff) proliferation (123). With the progress of diagnostic imaging, PET of activated microglia in ALS patients offers a potential opportunity to assess Treg-mediated neuroprotection (63, 67, 127). While Treg and anti-inflammatory microglia increase in the early stage of ALS (128–130), Th1 and pro-inflammatory microglia increased the inflammation in the microenvironment in the later stage of ALS (131, 132). Accordingly, a parallel shift from a neuroprotective Treg/anti-inflammatory response to a neurotoxic Th1/pro-inflammatory response has been postulated during ALS progression by Zhao et al. (132). In the mSOD1 mouse model, a Treg/anti-inflammatory response dominates the initial slowly progressing phase of the disease, as Tregs suppress microglial toxicity and SOD1 T effector cells through IL-4, IL-10 and TGF-β (132). During ALS progresses, the immune response switches to a deleterious Th1/pro-inflammatory response, where the interaction between Th1 and microglia enhances pro-inflammatory responses, including the release of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, and downregulates Treg suppressive functions (132).

Overall, these data support the concept of a well-orchestrated and complex dialog among microglia and CD4+ T cells, suggesting that different CD4+ T lymphocyte subsets play different roles in shaping microglial functions during ALS progression.

3.3.2. Microglia – CD8+ T lymphocytes crosstalk

In the peripheral blood of ALS patients, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells number was found to be significantly increased, suggesting a systemic immune activation (133). However, the role of these cells in the progression of ALS remains difficult to decipher (134).

Particularly, microglia-CD8+ T cell crosstalk is fundamental to drive the inflammation in ALS affected regions (120). Specifically, major histocompatibility complex I (MHCI) depletion in resident microglia or the lack of CD8+ T cell infiltration in the spinal cord of β2 microglobulin-deficient hSOD1G93A mice (which express little if any MHCI on the cell surface and are defective for CD8+ T cells) delayed motor symptoms and prolonged the survival mean time, suggesting that microglia interact with infiltrated CD8+ T cells through MHC complex, promoting MN death in ALS. Moreover, the level of CD68+ microglia was lower in the spinal cord of β2 microglobulin-deficient hSOD1G93A mice suggesting that the MN preservation is due to a lack of interaction with CD8+ T cells (120). Interestingly, β2 microglobulin-deficiency in the peripheral nervous system (i.e. sciatic nerve) impaired motor axon stability and anticipated the onset of muscle atrophy, delineating regional differences in the role of MHCI and CD8+ T cells in the pathogenesis of ALS (120).

3.4. Microglia – Monocytes/macrophages crosstalk

In ALS patients, peripheral monocytes infiltrate the CNS (66), and the monocytes isolated from peripheral blood of ALS patients show a pro-inflammatory profile (135). Furthermore, the degree of systemic monocyte/macrophage activation directly correlates to the rate of disease progression (136). In the hSOD1G93A mouse model, inflammatory monocytes infiltrate the ALS affected regions (137), and their progressive recruitment to the spinal cord correlates with neuronal loss (137). Prior to disease onset, monocytes expressed a polarized macrophage pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1 signature), which included increased levels of chemokine receptor CCR2. This receptor normally interacts with the ligand CCL2, controlling the migration and infiltration of CCR2-expressing monocytes/macrophages in a process implicated in multiple neurodegenerative diseases. Butovsky et al. demonstrated that CCL2 expression by microglia increases as ALS progresses (138). Mouse monocytes fall into two phenotypically distinct subsets: Ly-6Chi (which are CCR2+) and Ly-6Clo (which are CCR2−), corresponding to human CD14hiCD16− and CD14+CD16+ monocytes, respectively (138). Ly6C is a GPI-linked protein of the Ly6 family, which is found mostly in inflammatory monocytes (139). Accordingly, hSOD1G93A mouse treatment with anti-Ly6C monoclonal antibody reduced the number of monocytes recruited to the spinal cord, diminished neuronal loss, and extended survival (137).

Recently, a study by Chiot et al. (140) investigated the crosstalk between peripheral macrophages and microglia in ALS. Targeted gene modulation of the reactive oxygen species pathway in peripheral myeloid cells of hSOD1G93A mice, reduced both peripheral macrophage and microglial activation, and delayed the onset of motor symptoms (140). Specifically, the chemotherapy agent busulfan was used to induce myeloablation, followed by bone marrow transplantation in which mutant SOD1-expressing macrophages were replaced with macrophages genetically modified with less neurotoxic properties (via downregulating of Nox2 or overexpression of wild-type Sod1). In this model, resident microglial cells acquired an anti-inflammatory/protective phenotype and a reduction was found in microgliosis in the spinal cord (140). These results indicate that the modification of infiltrating monocytes/macrophages suppresses neurotoxic microglial responses in ALS, suggesting direct or indirect crosstalk between these two cell populations. The mechanisms underlying this crosstalk are not yet clear, but the authors suggested that replacing of inflammatory peripheral monocytes/macrophages could pave the way for a new therapeutic approach for ALS patients.

4. Currently approved therapies in ALS

The complex pathogenesis in ALS, coupled with its clinical and molecular heterogeneity, resulted in too many failed attempts at drug discovery and development. The foundation for failure includes the wrong target, route of administration, outcome measures, and the many different pathogenic mechanisms at play in different patients (141). Drugs undergoing clinical trials are available on the ALS Association website (https://www.neals.org/als-trials/search-for-a-trial/). To date, there are two FDA-approved drugs for ALS: riluzole and edaravone. Both drugs have a relatively small efficacy in delaying motor function deterioration, and their effectiveness is limited during early stages of the disease (142).

Riluzole was the first FDA drug approved for clinical use in 1995. This drug blocks glutamate release and therefore glutamatergic neurotransmission in the CNS, exerting neuroprotective function as it dampens pathological excitotoxicity in ALS (143). Additional proposed mechanisms of action include an indirect antagonism of glutamate receptors in addition to the inactivation of neuronal voltage-gated Na+ channel (144). Edaravone was the second FDA approved ALS-specific drug, in 2017. Edaravone is a neuroprotective drug with broad free radical scavenging activity that protect neurons, glia, and vascular endothelial cells against oxidative stress (145).

4.1. Therapies targeting neuroinflammation and microglial crosstalk with peripheral immune cells

Multiple compounds with immune-modulatory properties have been reported to affect the crosstalk between microglia and immune cells. Although promising in the mouse models of ALS, preclinical results have so far failed to translate into meaningful clinical outcomes (146, 147). Most efforts in the development and application of immune-modulatory drugs in ALS aimed at reducing pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic immune responses. Among the therapies recently developed to target neuroinflammation and microglia phenotype in ALS, the following demonstrated significant benefits in preclinical studies and have already or are soon to be translated to clinical trials (Table 1).

Table 1.

Therapies targeting neuroinflammation and microglial crosstalk with peripheral immune cells in ALS.

| Drug | Mechanism | Target cells | Trial number | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dl-3-n-Butylphthalide (NBP) | Modulation of mitochondrial oxidative stress, apoptosis and autophagy | Microglia, Motor Neurons | ChiCTR-IPR-15007365 | II |

| Cannabinoids | Anti-glutamatergic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions | Microglia | N/A | N/A |

| Ibudilast (MN-166) | Anti-inflammatory and neurotrophic actions | Microglia |

NCT02238626 NCT04057898 |

II IIb/III |

| Masitinib | Anti-inflammatory; modulation of aberrant microgliosis | Microglia |

NCT02588677 NCT03127267 |

II/III III |

| Minocycline | Anti-inflammatory | Microglia, Motor Neurons | NCT00047723 | III |

| NP001 | Anti-inflammatory | Microglia |

NCT01091142 NCT01281631 NCT02794857 |

I II II |

N/A, not applicable.

- dl-3-n-Butylphthalide (NBP) is a small molecule compound showing neuroprotective effects via multiple mechanisms, including modulation of mitochondrial oxidative stress, apoptosis and autophagy (148). In hSOD1G93A mice, treatment with NBP extended survival by attenuating microglial activation and motor neuron loss (149, 150). A randomized trial (Chictr.org.cn Identifier: ChiCTR-IPR-15007365) of NBP in the treatment of ALS patients was conducted in China. The preliminary results indicated that NBP did not improve the ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS)-R score in patients with ALS (151).

- Cannabinoids exert anti-glutamatergic, anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory actions through activation of the CB (1) and CB(2) receptors, whereby receptor activation reduces pro-inflammatory microglia, decreasing the microglial secretion of neurotoxic mediators (152, 153). In hSOD1G93A mice, treatment with WIN-55,212-2, a cannabinoid agonist with higher affinity to the CB2 than the CB1 receptor (154), and the Selective CB2 receptor agonist AM-1241 significantly delayed disease progression and increased mean survival time (155, 156). Although these promising results, a meta-analysis of the studies conducted on murine models concluded that animal studies have moderate to high risk of bias and are highly heterogeneous. Therefore, more standardized studies on cannabinoids are necessary before bringing these compounds to the clinic (157).

- Ibudilast (MN-166) is a non-selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor with a neuroprotective effect primarily mediated by the inhibition of inflammatory mediators and the upregulation of neurotrophic factors in pro-inflammatory microglia (158). Two clinical trials with ibudilast have been completed in ALS patients, and one is currently ongoing. The first Phase II trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02238626) evaluated the safety, tolerability and clinical responsiveness of ibudilast co-administered with riluzole. The study showed good safety and tolerability but no overall difference in disease progression between ibudilast and placebo treatment arms. Subgroup analysis suggested that patients with bulbar or upper limb onset might have more benefit from the compound (159). A Phase IIb/III study, the COMBAT-ALS study is currently recruiting on North America in order to evaluate the pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability and assess the efficacy of ibudilast on function, muscle strength, quality of life and survival in ALS (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04057898).

- Masitinib is a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor whose oral administration was shown to control aberrant microgliosis, abrogate neuroinflammation and slow disease progression in the hSOD1G93A mice (160). The primary analysis of a randomized Phase II/III trial testing masitinib in combination with riluzole for the treatment of ALS patients (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02588677) showed a significantly slowed functional decline, although there was no discernible difference in overall survival between the two arms (161). Long-term survival analysis indicated that oral masitinib prolonged survival by over 2 years as compared with placebo, provided that treatment started prior to severe impairment of functionality (162). A subsequent phase III clinical trial is currently ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03127267).

- Minocycline is a second-generation tetracycline antibiotic, capable to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, with anti-inflammatory effects independent of its antimicrobial activity. The compound has been demonstrated to dampen microglial activation (163) and apoptosis by inhibiting mitochondrial permeability-transition-mediated cytochrome c release (164). The compound delayed disease onset and extended survival in the hSOD1G93A and hSOD1G37R transgenic models of ALS (164–166). However, a subsequent randomized placebo-controlled phase III trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00047723) disproved any efficacy of the compound in patients, reporting an ALSFRS-R score deterioration faster in the minocycline group than in the placebo group, along with a higher incidence of adverse events (167).

- NP001 is a highly purified form of sodium chlorite, targeting inflammatory macrophages by down-regulating the Nuclear Factor kB (NF-kB) inflammatory pathways (168). Preliminary studies in hSOD1G93A mice showed a significant increase in life expectancy compared to control (169). A phase I trial in ALS patients (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01091142) showed that NP001 was generally safe and well tolerated, and caused a dose-dependent reduction in expression of the pro-inflammatory marker CD16 (170). Two subsequent randomized phase II trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01281631, NCT02794857) suggested that NP001 slowed the progression of ALS symptoms in a subset of patients with marked neuroinflammation (171). Combined post hoc analysis did not show significant differences between placebo and active treatment but identified a 40‐ to 65‐y‐old subset in which NP001‐treated patients demonstrated slower declines in ALSFRS‐R score compared with placebo (172).

5. Conclusions

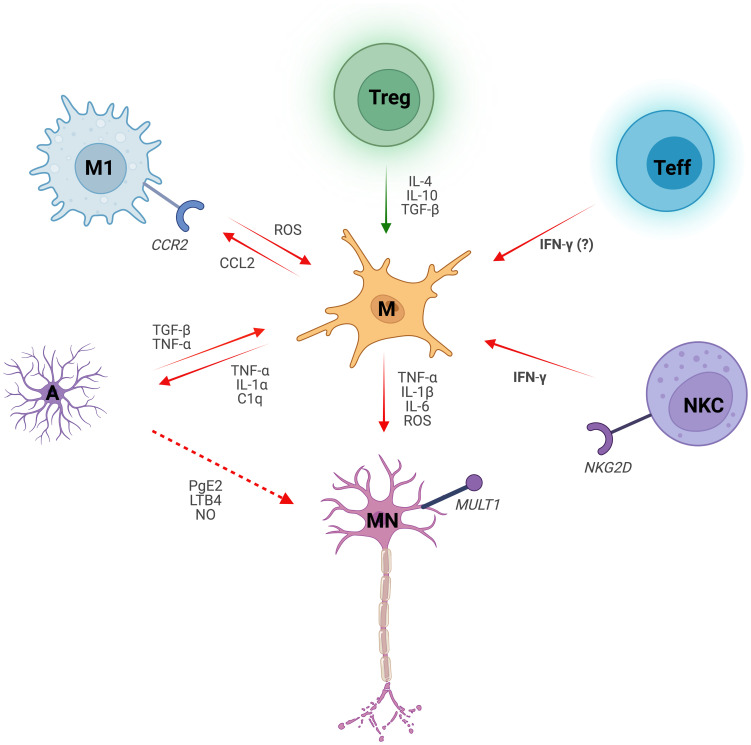

The crosstalk between immune cells and glia contribute to MN degeneration in ALS. Despite the advance in the scientific findings aimed to unravel the molecular and cellular mechanisms that induce MN to death, ALS persists without effective therapy that improves motor symptoms and increases the life of patients. In ALS microglia promote a pro-inflammatory microenvironment, supported by neurotoxic astrocytes and infiltrated lymphocytes and macrophages that exert an effective immune reaction against MNs (Figure 1) (92, 96–108, 120, 140, 173).

Figure 1.

Microglial dialogue with non-neuronal cells in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Microglia (M) induce motor neuron (MN) degeneration in ALS by secreting reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), Interleukin 6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF-α). Microglial crosstalk with non-neuronal cells shapes their phenotype, either skewing it towards a pro-inflammatory (red arrows) on anti-inflammatory (green arrows) phenotype. Microglial-derived pro-inflammatory cytokines Interleukin 1 alpha (IL-1α), TNFα and complement component C1q induce pro-inflammatory astrocytes (A). Conversely, activated astrocytes promote inflammatory microglial responses via Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β) and TNF‐α. Reactive astrocytes also exert toxic effects on MNs by secreting inflammatory mediators such as Prostaglandin E2 (PgE2), Leukotriene B4 (LBT4) and nitric oxide (NO). Chemokine ligand 2 receptor (CCR2)-expressing macrophages (M1) are recruited by the Chemokine Ligand 2 (CCL2) released by microglia. ROS pathway in classically activated macrophages induces microglial activation. Regulatory T cells (Treg) suppress microglial toxicity as well as other immune cells (not shown) through Interleukin 4 (IL-4), Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and TGF-β. Notably, TGF-β effect on microglia is context- and cell-dependent. Microglia-CD8+ Effector T cell (Teff) crosstalk drives neuroinflammation in ALS, with Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) secreted by the latter likely playing a role. Infiltrated Natural Killer Cells (NKC) instruct microglia towards an inflammatory profile by the release of IFN-γ. Additionally, NKCs are neurotoxic to MNs via NKG2D - NKG2D ligand (MULT1) interaction.

Here we review the state-of-art regarding this fascinating cellular communication, highlighting the current hypothesis that modulating the interaction of microglia with astrocytes and immune cells could represent a promising therapy. It is crucial to keep improving the biological knowledge of ALS and the interplay with resident and infiltrating immune cells in order to understand the cell-to-cell communication mechanisms and their role in driving disease pathogenesis. At last, we discuss the current experimental approaches that aim to modulate microglial phenotype to modulate the inflammation in the CNS counteracting ALS progression.

The possibility to integrate these exciting discoveries with new combination therapies will open new tools to treat this devastating disease.

Author contributions

MC and GC wrote review. CL and SG supervised, wrote and edited the review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

SG was supported by A0112E0073 Funding Source: Regione Lazio POR FSE 2014-2020 PRATT25118; NextGenerationEU” DD. 3175/2021 E DD. 3138/2021 CN_3: National Center for Gene Therapy and Drugs based on RNA Technology Codice Progetto CN 00000041; RF GR-2021-12372494. G.C. was supported by NextGenerationEU” DD. 3175/2021 E DD. 3138/2021 CN_3: National Center for Gene Therapy and Drugs based on RNA Technology Codice Progetto CN 00000041. C.L. was supported by RF-2018-12366215; Next Generation EU PNRR Rome Technopole Flagship 7; Ateneo Sapienza “SEED” PNR 2022.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Goutman SA, Hardiman O, Al-Chalabi A, Chió A, Savelieff MG, Kiernan MC, et al. Emerging insights into the complex genetics and pathophysiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol (2022) 21:465–79. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00414-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Renton AE, Chio A, Traynor BJ. State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat Neurosci (2014) 17:17–23. doi: 10.1038/nn.3584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keller MF, Ferrucci L, Singleton AB, Tienari PJ, Laaksovirta H, Restagno G, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the heritability of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol (2014) 71:1123–34. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al-Chalabi A, Fang F, Hanby MF, Leigh PN, Shaw CE, Ye W, et al. An estimate of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis heritability using twin data. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2010) 81:1324–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.207464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fang F, Kamel F, Lichtenstein P, Bellocco R, Sparén P, Sandleret DP, et al. Familial aggregation of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol (2009) 66:94–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.21580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature (1993) 362:59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chia R, Chio A, Traynor BJ. Novel genes associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: diagnostic and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol (2018) 17:94–102. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30401-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayashi Y, Homma K, Ichijo H. SOD1 in neurotoxicity and its controversial roles in SOD1 mutation-negative ALS. Adv Biol Regul (2016) 60:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2015.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Inflammatory processes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve (2002) 26:459–70. doi: 10.1002/mus.10191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferraiuolo L, Kirby J, Grierson AJ, Sendtner M, Shaw PJ. Molecular pathways of motor neuron injury in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol (2011) 7:616–30. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hop PJ, Zwamborn RAJ, Hannon E, Shireby GL, Nabais MF, Walker EM, et al. Genome-wide study of DNA methylation shows alterations in metabolic, inflammatory, and cholesterol pathways in ALS. Sci Transl Med (2022) 14:eabj0264. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj0264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dal Canto MC, Gurney ME. Development of central nervous system pathology in a murine transgenic model of human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Pathol (1994) 145:1271–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boillée S. Onset and progression in inherited ALS determined by motor neurons and microglia. Science (2006) 312:1389–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1123511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bosco DA, Morfini G, Karabacak N.M, Song Y, Gros-Louis F, Pasinelli P, et al. Wild-type and mutant SOD1 share an aberrant conformation and a common pathogenic pathway in ALS. Nat Neurosci (2010) 13:1396–403. doi: 10.1038/nn.2660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wegorzewska I. TDP-43 mutant mice develop features of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2009) 106:18809–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908767106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suk TR, Rousseaux MWC. The role of TDP-43 mislocalization in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Neurodegener (2020) 15:45. doi: 10.1186/s13024-020-00397-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Renton AE, Rousseaux MWC. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron (2011) 72:257–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron (2011) 72:245–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ebbert MTW, Farrugia SL, Sens JP, Jansen-West K, Gendron TF, Prudencio M, et al. Long-read sequencing across the C9orf72 ‘GGGGCC’ repeat expansion: implications for clinical use and genetic discovery efforts in human disease. Mol Neurodegener (2018) 13:46. doi: 10.1186/s13024-018-0274-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ciura S, Lattante S, Le Ber I, Latouche M, Tostivint H, Brice A, et al. Loss of function of C9orf72 causes motor deficits in a zebrafish model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol (2013) 74:180–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.23946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Therrien M, Rouleau GA, Dion PA, Parker JA. Deletion of C9ORF72 results in motor neuron degeneration and stress sensitivity in c. elegans. PloS One (2013) 8:e83450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pelvig DP, Pakkenberg H, Stark AK, Pakkenberg B. Neocortical glial cell numbers in human brains. Neurobiol Aging (2008) 29:1754–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Masuda T, Amann L, Monaco G, Sankowski R, Staszewski O, Krueger M, et al. Specification of CNS macrophage subsets occurs postnatally in defined niches. Nature (2022) 604:740–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04596-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Dri P, Gordon S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience (1990) 39:151–70. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol (2009) 27:119–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bruttger J, Karram K, Wörtge S, Regen T, Marini F, Hoppmann N, et al. Genetic cell ablation reveals clusters of local self-renewing microglia in the mammalian central nervous system. Immunity (2015) 43:92–106. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ransohoff RM. A polarizing question: do M1 and M2 microglia exist? nat. Neurosci. (2016) 19:987–91. doi: 10.1038/nn.4338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hammond BP, Manek R, Kerr BJ, Macauley MS, Plemel JR. Regulation of microglia population dynamics throughout development, health, and disease. Glia (2021) 69(12):2771–97. doi: 10.1002/glia.24047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hammond TR, Robinton D, Stevens B. Microglia and the brain: complementary partners in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol (2018) 34:523–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zia S, Rawji KS, Michaels NJ, Burr M, Kerr BJ, Healy LM, et al. Microglia diversity in health and multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol (2020) 11:588021. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.588021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Masuda T, Sankowski R, Staszewski O, Prinz M. Microglia heterogeneity in the single-cell era. Cell Rep (2020) 30:1271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deczkowska A, Amit I, Schwartz M. Microglial immune checkpoint mechanisms. Nat Neurosci (2018) . 21:6. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0145-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brown GC, Neher JJ. Microglial phagocytosis of live neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci (2014) 15:209–16. doi: 10.1038/nrn3710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schafer DP, Stevens B. Phagocytic glial cells: sculpting synaptic circuits in the developing nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol (2013) 23:1034–40. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tremblay ME, Lowery RL, Majewska AK. Microglial interactions with synapses are modulated by visual experience. PloS Biol (2010) 8:e1000527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Paolicelli RC, Bolasco G, Pagani F, Maggi L, Scianni M, Panzanelli P, et al. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science (2011) 333:1456–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1202529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hughes AN, Appel B. Microglia phagocytose myelin sheaths to modify developmental myelination. Nat Neurosci (2020) 23(9):1055–1066. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0654-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lloyd AF, Davies CL, Holloway RK, Labrak Y, Ireland G, Carradori D, et al. Central nervous system regeneration is driven by microglia necroptosis and repopulation. Nat Neurosci (2019) 22(7):1046–1052. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0418-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moore CS, Ase AR, Kinsara A, Rao VTS, Michell-Robinson M, Leong SY, et al. P2Y12 expression and function in alternatively activated human microglia. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm (2015) 2:e80. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Riazi K, Galic MA, Kentner AC, Reid AY, Sharkey KA, Pittman QJ, et al. Microglia-dependent alteration of glutamatergic synaptic transmission and plasticity in the hippocampus during peripheral inflammation. J Neurosci (2015) 35:4942–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4485-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Naj AC, Naj AC, Jun G, Reitz C, Kunkle BW, Perry W, et al. Effects of multiple genetic loci on age at onset in late-onset Alzheimer disease: a genome-wide association study. JAMA Neurol (2014) 71:1394–404. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Butovsky O, Weiner HL. Microglial signatures and their role in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci (2018) 19:622–35. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0057-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Masuda T, Sankowski R, Staszewski O, Bottcher C, Amann L, Sagar et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of mouse and human microglia at single-cell resolution. Nature (2019) 566(7744):388–392. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0924-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, Baufeld C, Calcagno N, El Fatimy R, et al. The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity (2017) 47(3):566–581 e569. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wyss-Coray T, Rogers J. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease-a brief review of the basic science and clinical literature. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med (2012) 2:a006346. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leng F, Edison P. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: where do we go from here? Nat Rev Neurol (2020) 17:157–172. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-00435-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gushchina S, Pryce G, Yip PK, Wu D, Pallier P, Giovannoni G, et al. Increased expression of colony-stimulating factor-1 in mouse spinal cord with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis correlates with microglial activation and neuronal loss. Glia (2018) 66(10):2108–2125. doi: 10.1002/glia.23464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J. Microglial dysfunction and defective beta-amyloid clearance pathways in aging alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci (2008) 28:8354–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liao B, Zhao W, Beers DR, Henkel JS, Appel SH. Transformation from a neuroprotective to a neurotoxic microglial phenotype in a mouse model of ALS. Exp Neurol (2012) 237:147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Muzio L, Martino G, Furlan R. Multifaceted aspects of inflammation in multiple sclerosis: the role of microglia. J Neuroimmunol (2007) 191:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. El Khoury J, Hickman SE, Thomas CA, Cao L, Silverstein SC, Loike JD. Scavenger receptor-mediated adhesion of microglia to beta-amyloid fbrils. Nature (1996) 382:716–9. doi: 10.1038/382716a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hickman SE, Kingery ND, Ohsumi TK, Borowsky ML, Wang L, Means TK, et al. The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci (2013) 16:1896–905. doi: 10.1038/nn.3554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Saijo K, Crotti A, Glass CK. Regulation of microglia activation and deactivation by nuclear receptors. Glia (2013) 61:104–11. doi: 10.1002/glia.22423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Heneka MT, Golenbock DT, Latz E. Innate immunity in alzheimer’s disease. Nat Immunol (2015) 16:229–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wu J, Chen ZJ. Innate immune sensing and signaling of cytosolic nucleic acids. Annu Rev Immunol (2014) 32:461–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Areschoug T, Gordon S. Scavenger receptors: role in innate immunity and microbial pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol (2009) 11:1160–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Appel SH, Zhao W, Beers DR, Henkel JS. The microglial-motoneuron dialogue in ALS. Acta Myol (2011) 30:4–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ransohof RM, El Khoury J. Microglia in health and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2015) 8:a020560. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hickman S, Izzy S, Sen P, Morsett L, El Khoury J. Microglia in neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci (2018) 21:1359–69. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0242-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bemiller SM, McCray TJ, Allan K, Formica SV, Xu G, Wilson G, et al. TREM2 deficiency exacerbates tau pathology through dysregulated kinase signaling in a mouse model of tauopathy. Mol Neurodegener (2017) 12:74. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0216-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson PV, Snaedal J, et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med (2013) 368:107–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ghosh R, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington disease. Handb Clin Neurol (2018) 147:255–78. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63233-3.00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Corcia P, Tauber C, Vercoullie J, Arlicot N, Prunier C, Praline J, et al. Molecular imaging of microglial activation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PloS One (2012) 7:e52941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Brites D, Vaz AR. Microglia centered pathogenesis in ALS: insights in cell interconnectivity. Front Cell Neurosci (2014) 8:117. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ransohoff RM, Schafer D, Vincent A, Blachere NE, Bar-Or A. Neuroinflammation: ways in which the immune system affects the brain. Neurotherapeutics (2015) 12:896–909. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0385-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Henkel JS, Engelhardt JI, Siklos L, Simpson EP, Kim SH, Pan T, et al. Presence of dendritic cells, MCP-1, and activated microglia/macrophages in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord tissue. Ann Neurol (2004) 55:221–35. doi: 10.1002/ana.10805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Turner MR, Cagnin A, Turkheimer FE, Miller CC, Shaw CE, Brooks DJ, et al. Evidence of widespread cerebral microglial activation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an [11C](R)-PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Neurobiol Dis (2004) 15:601–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zurcher NR, Loggia ML, Lawson R, Chonde DB, Izquierdo-Garcia D, et al. Increased in vivo glial activation in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: assessed with [11C]-PBR28. NeuroImage Clin (2015) 7:409–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chiu I, Morimoto EA, Goodarzi H, Liao J, O’Keeffe S, Phatnani H, et al. A neurodegeneration-specific gene-expression signature of acutely isolated microglia from an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Cell Rep (2013) 4(2):385–401. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Clarke BE, Patani R. The microglial component of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain (2020) 12:3526–39. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Beers DR. Neuroinflammation modulates distinct regional and temporal clinical responses in ALS mice. Brain Behav Immun (2011) 25:1025–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Beers DR, Henkel JS, Xiao Q, Zhao W, Wang J, Yen AA, et al. Wild-type microglia extend survival in PU.1 knockout mice with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A (2006) 103(43):16021–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Salter MW. Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nat Med (2017) 23:1018–27. doi: 10.1038/nm.4397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Deczkowska A. Disease-associated microglia: a universal immune sensor of neurodegeneration. Cell (2018) 173:1073–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Frakes AE, Ferraiuolo L, Haidet-Phillips AM, Schmelzer L, Braun L, Miranda CJ, et al. Microglia induce motor neuron death via the classical NF-κB pathway in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuron (2014) 81:1009–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Thonhoff JR, Gao J, Dunn TJ, Ojeda L, Wu P. Mutant SOD1 microglia-generated nitroxidative stress promotes toxicity to human fetal neural stem cellderived motor neurons through direct damage and noxious interactions with astrocytes. Am J Stem Cells (2011) 19:2–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cocozza G, Garofalo S, Morotti M, Chece G, Grimaldi A, Lecce M, et al. The feeding behaviour of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse models is modulated by the Ca2+ -activated KCa 3.1 channels. Br J Pharmacol (2021) 178(24):4891–906. doi: 10.1111/bph.15665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Parisi C, Arisi I, D’Ambrosi N, Storti AE, Brandi R, D’Onofrio M, et al. Dysregulated microRNAs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis microglia modulate genes linked to neuroinflammation. Cell Death Dis (2013) 12:e959. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cocozza G, di Castro MA, Carbonari L, Grimaldi A, Antonangeli F, Garofalo S, et al. Ca2+-activated k+ channels modulate microglia affecting motor neuron survival in hSOD1G93A mice. Brain Behav Immun (2018) 73:584–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Spiller KJ, Restrepo CR, Khan T, Dominique MA, Fang TC, Canter RG, et al. Microglia-mediated recovery from ALS-relevant motor neuron degeneration in a mouse model of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Nat Neurosci (2018) 21:329–40. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0083-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Majounie E, Renton AE, Mok K, Dopper EG, Waite A, Rollinson S, et al. Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol (2012) 11:323–30. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70043-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Belzil VV, Bauer PO, Prudencio M, Gendron TF, Stetler CT, Yan IK, et al. Reduced C9orf72 gene expression in c9FTD/ALS is caused by histone trimethylation, an epigenetic event detectable in blood. Acta Neuropathol (2013) 126:895–905. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1199-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gijselinck I, Van Langenhove T, van der Zee J, Sleegers K, Philtjens S, Kleinberger G, et al. A C9orf72 promoter repeat expansion in a Flanders-Belgian cohort with disorders of the frontotemporal lobar degeneration-amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spectrum: a gene identification study. Lancet Neurol (2012) 11:54–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70261-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Fratta P, Poulter M, Lashley T, Rohrer JD, Polke J. M, Beck J, et al. Homozygosity for the C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat expansion in frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol (2013) 126:401–9. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1147-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Xi Z, Zinman L, Moreno D, Schymick J, Liang Y, Sato C, et al. Hypermethylation of the CpG island near the G4C2 repeat in ALS with a C9orf72 expansion. Am J Hum Genet (2013) 92:981–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Waite AJ, Baumer D, East S, Neal J, Morris HR, Ansorge O, et al. Reduced C9orf72 protein levels in frontal cortex of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal degeneration brain with the C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion. Neurobiol Aging (2014) 35:1779.e5–1779.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. O’Rourke JG, Bogdanik L, Yáñez A, Lall D, Wolf AJ, Muhammad AKMG, et al. C9orf72 is required for proper macrophage and microglial function in mice. Science (2016) 351:1324–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Donnelly CJ, Zhang PW, Pham JT, Haeusler AR, Mistry NA, Vidensky S, et al. RNA Toxicity from the ALS/FTD C9ORF72 expansion is mitigated by antisense intervention. Neuron (2013) 80:415–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Sareen D, O'Rourke JG, Meera P, Muhammad AKMG, Grant S, Simpkinson M, et al. Targeting RNA foci in iPSC-derived motor neurons from ALS patients with a C9ORF72 repeat expansion. Sci Trans Med (2013) 5:208ra149. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ash PEA, Bieniek KF, Gendron TF, Caulfield T, Lin WL, Dejesus-Hernandez M, et al. Unconventional translation of C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion generates insoluble polypeptides specific to c9FTD/ALS. Neuron (2013) 77:639–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zu T, Liu Y, Banez-Coronel M, Reid T, Pletnikova O, Lewis J, et al. RAN proteins and RNA foci from antisense transcripts in C9ORF72 ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2013) 110:E4968–77. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315438110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE, Bennett FC, Bohlen CJ, Schirmer L, et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature (2017) 541:481–7. doi: 10.1038/nature21029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Phani S, Re DB, Przedborski S. The role of the innate immune system in ALS. Front Pharmacol (2012) 3:150. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kawamata T, Akiyama H, Yamada T, McGeer PL. Immunologic reactions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis brain and spinal cord tissue. Am J Pathol (1992) 140:691–707. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Schiffer D, Cordera S, Cavalla P, Migheli A. Reactive astrogliosis of the spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci (1996) 139:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(96)00073-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Nagy D, Kato T, Kushner PD. Reactive astrocytes are widespread in the cortical gray matter of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci Res (1994) 38:336–47. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490380312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Johansson A, Engler H, Blomquist G, Scott B, Wall A, et al. Evidence for astrocytosis in ALS demonstrated by [11C](L)-deprenyl-D2 PET. J Neurol Sci (2007) 255:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ouali Alami N, Schurr C, Olde Heuvel F, Tang L, Li Q, Tasdogan A, et al. NF-κB activation in astrocytes drives a stage-specific beneficial neuroimmunological response in ALS. EMBO J (2018) 37:e98697. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Guttenplan KA, Weigel MK, Adler DI, Couthouis J, Liddelow SA, Gitler AD, et al. Knockout of reactive astrocyte activating factors slows disease progression in an ALS mouse model. Nat Commun (2020) 11:3753. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17514-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Peng AYT, et al. Loss of TDP-43 in astrocytes leads to motor deficits by triggering A1-like reactive phenotype and triglial dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2020) 117:29101–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007806117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Liang LL, Zhu B, Zhao Y, Li X, Liu T, Pina-Crespo J, et al. Membralin deficiency dysregulates astrocytic glutamate homeostasis leading to ALS-like impairment. J Clin Invest (2019) 129:3103–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI127695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Alexianu ME, Kozovska M, Appel SH. Immune reactivity in a mouse model of familial ALS correlates with disease progression. Neurology (2001) 57:1282–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.7.1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yang WW, Sidman RL, Taksir TV, Treleaven CM, Fidler JA, Cheng SH. Relationship between neuropathology and disease pro- gression in the SOD1(G93A) ALS mouse. Exp Neurol (2011) 227:287–95. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Endo F, Komine O, Fujimori-Tonou N, Katsuno M, Jin S, Watanabe S, et al. Astrocyte-derived TGF-β1 accelerates disease progression in ALS mice by interfering with the neuroprotective functions of microglia and T cells. Cell Rep (2015) 11(4):592–604. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Brites D. The evolving landscape of neurotoxicity by unconjugated bilirubin: role of glial cells and inflammation. Front Pharmacol (2012) 3:88. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Meme W, Calvo CF, Froger N, Ezan P, Amigou E, Koulakoff A, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines released from microglia inhibit gap junc- tions in astrocytes: potentiation by beta-amyloid. FASEB J (2006) 20:494–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4297fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Murdock BJ, Zhou T, Kashlan SR, Little RJ, Goutman SA, Feldman EL. Correlation of peripheral immunity with rapid amyotrophic lateral sclerosis progression. JAMA Neurol (2017) 74(12):1446–54. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Garofalo S, Cocozza G, Porzia A, Inghilleri M, Raspa M, Scavizzi F, et al. Natural killer cells modulate motor neuron-immune cell cross talk in models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):1773. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15644-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Garofalo S, Cocozza G, Bernardini G, Savage J, Raspa M, Aronica E, et al. Blocking immune cell infiltration of the central nervous system to tame neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Behav Immun (2022) 105:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2022.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Yu Y, Schürpf T, Springer TA. How natalizumab binds and antagonizes α4 integrins. J Biol Chem (2013) 45:32314–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.501668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Gan Y, Liu R, Wu W, Bomprezzi R, Shi FD. Antibody to α4 integrin suppresses natural killer cells infiltration in central nervous system in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol (2012) 247:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Engelhardt B, Ransohoff RM. The ins and outs of T-lymphocyte trafficking to the CNS: anatomical sites and molecular mechanisms. Trends Immunol (2005) 26(9):485–95. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Matejuk A, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Cross-talk of the CNS with immune cells and functions in health and disease. Front Neurol (2021) 12:672455. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.672455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Engelhardt JI, Tajti J, Appel SH. Lymphocytic infiltrates in the spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol (1993) 50:30–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540010026013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Fiala M, Chattopadhay M, La Cava A, Tse E, Liu G, Lourenco E, et al. IL-17A is increased in the serum and in spinal cord CD8 and mast cells of ALS patients. J Neuroinflammation (2010) 7:76. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Beers DR, Henkel JS, Zhao W, Wang J, Appel SH. CD4+ T cells support glial neuroprotection, slow disease progression, and modify glial morphology in an animal model of inherited ALS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2008) 105:15558–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807419105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Chiu IM, Chen A, Zheng Y, Kosaras B, Tsiftsoglou SA, et al. T Lymphocytes potentiate endogenous neuroprotective inflammation in a mouse model of ALS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2008) 105:17913–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804610105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Kipnis J, Schwartz M. Controlled autoimmunity in CNS maintenance and repair: naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells at the crossroads of health and disease. Neuromol Med (2005) 7:197–206. doi: 10.1385/NMM:7:3:197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Coque E, Salsac C, Espinosa-Carrasco G, Varga B, Degauque N, Cadoux M, et al. Cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing ALS-causing SOD1 mutant selectively trigger death of spinal motoneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2019) 116(6):2312–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815961116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Nardo G, Trolese MC, Verderio M, Mariani A, De Paola M, Riva N, et al. Counteracting roles of MHCI and CD8+ T cells in the peripheral and central nervous system of ALS SOD1G93A mice. Mol Neurodegener (2018) 13(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s13024-018-0271-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Hirahara K, Nakayama T. CD4+ T-cell subsets in inflammatory diseases: beyond the Th1/Th2 paradigm. Int Immunol (2016) 28(4):163–71. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxw006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Beers DR, Henkel JS, Zhao W, Wang J, Huang A, Wen S, et al. Endogenous regulatory T lymphocytes ameliorate amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice and correlate with disease progression in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain (2011) 134(Pt 5):1293–314. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Beers DR, Zhao W, Wang J, Zhang X, Wen S, Neal D, et al. ALS patients’ regulatory T lymphocytes are dysfunctional, and correlate with disease progression rate and severity. JCI Insight (2017) 2:e89530. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Henkel JS, Beers DR, Zhao W, Appel SH. Microglia in ALS: the good, the bad, and the resting. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol (2009) 4:389–98. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9171-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Cardona AE, Pioro EP, Sasse ME, Kostenko V, Cardona SM, Dijkstra IM, et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat Neurosci (2006) 9:917–24. doi: 10.1038/nn1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Henkel JS, Beers DR, Wen S, Rivera AL, Toennis KM, Appel JE, et al. Regulatory T-lymphocytes mediate amyotrophic lateral sclerosis progression and survival. EMBO Mol Med (2013) 5(1):64–79. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Thonhoff JR, Simpson EP, Appel SH. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathogenesis. Curr Opin Neurol (2018) 31(5):635–9. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Liu G, Ma H, Qiu L, Li L, Cao Y, Ma J, et al. Phenotypic and functional switch of macrophages induced by regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in mice. Immunol Cell Biol (2011) 89:130–42. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Tiemessen MM, Jagger AL, Evans HG, van Herwijnen MJ, John S, Taams LS. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce alternative activation of human monocytes/macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2007) 104:19446–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706832104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Savage NDL, de Boer T, Walburg KV, Joosten SA, van Meijgaarden K, Geluk A, et al. Human anti-inflammatory macrophages induce Foxp3+GITR+CD25+ regulatory T cells, which suppress via membrane-bound TGF -1. J Immunol (2008) 181:2220–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Gao Z, Tsirka SE. Animal models of MS reveal multiple roles of microglia in disease pathogenesis. Neurol Res Int (2011) 2011:383087. doi: 10.1155/2011/383087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Zhao W, Beers DR, Appel SH. Immune-mediated mechanisms in the pathoprogression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol (2013) 8:888–99. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9489-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Rentzos M, Evangelopoulos E, Sereti E, Zouvelou V, Marmara S, Alexakis T, et al. Alterations of T cell subsets in ALS: a systemic immune activation? Acta Neurol Scand (2012) 125(4):260–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Liu Z, Cheng X, Zhong S, Zhang X, Liu C, Liu F, et al. Peripheral and central nervous system immune response crosstalk in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Neurosci (2020) 14:575. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Zhao W, Beers DR, Hooten KG, Sieglaff DH, Zhang A, Kalyana-Sundaram S, et al. Characterization of gene expression phenotype in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis monocytes. JAMA Neurol (2017) 74:677–85. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Zhang R, Gascon R, Miller RG, Gelinas DF, Mass J, Hadlock K, et al. Evidence for systemic immune system alterations in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (sALS). J Neuroimmunol (2005) 159(1-2):215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Butovsky O, Siddiqui S, Gabriely G, Lanser AJ, Dake B, Murugaiyan G, et al. Modulating inflammatory monocytes with a unique microRNA gene signature ameliorates murine ALS. J Clin Invest (2012) 122:3063–87. doi: 10.1172/jci62636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity (2003) 19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00174-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol (2008) 8(12):958–69. doi: 10.1038/nri2448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Chiot A, Zaïdi S, Iltis C, Ribon M, Berriat F, Schiaffino L, et al. Modifying macrophages at the periphery has the capacity to change microglial reactivity and to extend ALS survival. Nat Neurosci (2020) 23(11):1339–51. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00718-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Morgan S, Orrell RW. Pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Br Med Bull (2016) 119(1):87–98. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldw026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Liscic RM, Alberici A, Cairns NJ, Romano M, Buratti E. From basic research to the clinic: innovative therapies for ALS and FTD in the pipeline. Mol Neurodegener (2020) 15(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s13024-020-00373-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Doble A. The pharmacology and mechanism of action of riluzole. Neurology. (1996) 47(6 Suppl 4):S233–41. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6_suppl_4.233s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Cheah BC, Vucic S, Krishnan AV, Kiernan MC. Riluzole, neuroprotection and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Med Chem (2010) 17(18):1942–199. doi: 10.2174/092986710791163939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Takei K, Watanabe K, Yuki S, Akimoto M, Sakata T, Palumbo J. Edaravone and its clinical development for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener (2017) 18(sup1):5–10. doi: 10.1080/21678421.2017.1353101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Petrov D, Mansfield C, Moussy A, Hermine O. ALS clinical trials review: 20 years of failure. are we any closer to registering a new treatment? Front Aging Neurosci (2017) 9:68. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Liu J, Wang F. Role of neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: cellular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol (2017) 8:1005. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Luo R, Wangqin R, Zhu L, Bi W. Neuroprotective mechanisms of 3-n-butylphthalide in neurodegenerative diseases. BioMed Rep (2019) 11(6):235–40. doi: 10.3892/br.2019.1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Feng X, Peng Y, Liu M, Cui L. DL-3-n-butylphthalide extends survival by attenuating glial activation in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropharmacology. (2012) 62(2):1004–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]