Key Points

Question

Does 1 year of treatment with atorvastatin, 40 mg/d, started prior to anthracycline-based chemotherapy among patients with lymphoma, reduce the chance of a significant decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) compared with placebo?

Findings

In this randomized trial of 300 adult patients with lymphoma, the percentage of patients with a decrease in cardiac function (≥10% absolute decline in LVEF from prior to chemotherapy to a final value of <55% over the 12-month study period), among those randomized to atorvastatin was 9% compared with a rate of 22% among patients randomized to placebo. This difference met statistical significance.

Meaning

Atorvastatin reduced cardiac functional impairment in patients with lymphoma treated with anthracyclines. This finding may support the use of atorvastatin in patients with lymphoma at risk of cardiac dysfunction due to anthracycline treatment.

Abstract

Importance

Anthracyclines treat a broad range of cancers. Basic and retrospective clinical data have suggested that use of atorvastatin may be associated with a reduction in cardiac dysfunction due to anthracycline use.

Objective

To test whether atorvastatin is associated with a reduction in the proportion of patients with lymphoma receiving anthracyclines who develop cardiac dysfunction.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Double-blind randomized clinical trial conducted at 9 academic medical centers in the US and Canada among 300 patients with lymphoma who were scheduled to receive anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Enrollment occurred between January 25, 2017, and September 10, 2021, with final follow-up on October 10, 2022.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to receive atorvastatin, 40 mg/d (n = 150), or placebo (n = 150) for 12 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of participants with an absolute decline in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of ≥10% from prior to chemotherapy to a final value of <55% over 12 months. A secondary outcome was the proportion of participants with an absolute decline in LVEF of ≥5% from prior to chemotherapy to a final value of <55% over 12 months.

Results

Of the 300 participants randomized (mean age, 50 [SD, 17] years; 142 women [47%]), 286 (95%) completed the trial. Among the entire cohort, the baseline mean LVEF was 63% (SD, 4.6%) and the follow-up LVEF was 58% (SD, 5.7%). Study drug adherence was noted in 91% of participants. At 12-month follow-up, 46 (15%) had a decline in LVEF of 10% or greater from prior to chemotherapy to a final value of less than 55%. The incidence of the primary end point was 9% (13/150) in the atorvastatin group and 22% (33/150) in the placebo group (P = .002). The odds of a 10% or greater decline in LVEF to a final value of less than 55% after anthracycline treatment was almost 3 times greater for participants randomized to placebo compared with those randomized to atorvastatin (odds ratio, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.4-6.4). Compared with placebo, atorvastatin also reduced the incidence of the secondary end point (13% vs 29%; P = .001). There were 13 adjudicated heart failure events (4%) over 24 months of follow-up. There was no difference in the rates of incident heart failure between study groups (3% with atorvastatin, 6% with placebo; P = .26). The number of serious related adverse events was low and similar between groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with lymphoma treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, atorvastatin reduced the incidence of cardiac dysfunction. This finding may support the use of atorvastatin in patients with lymphoma at high risk of cardiac dysfunction due to anthracycline use.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02943590

This randomized trial assesses the effect of 12 months of atorvastatin vs placebo on development of cardiac dysfunction among patients with lymphoma undergoing anthracycline-based chemotherapy.

Introduction

Anthracyclines such as doxorubicin are a key component of several standard chemotherapy regimens among patients with breast cancer, leukemia, lymphoma, and sarcoma.1 Data suggest that within 12 months after administration of anthracyclines, more than 20% of patients with lymphoma have a greater than 10% decline in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF),2 and that at 5 years, up to 20% develop heart failure.3

There is plausibility supporting the role of statins such as atorvastatin to prevent or reduce the cardiac dysfunction that may occur secondary to anthracyclines. In basic studies, atorvastatin was associated with a reduction in anthracycline-associated oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte cell death, leading to preserved cardiac function.4,5 In retrospective clinical research, statins preserved cardiac function and reduced heart failure after anthracycline use,6,7 and in a small prospective study, 40 mg/d of atorvastatin started prior to anthracyclines was associated with a higher LVEF at follow-up.8 However, in a recent randomized trial among women with primarily breast cancer, atorvastatin did not prevent an absolute decline in LVEF with anthracyclines.9 Herein, we present the results of the STOP-CA (Statins to Prevent the Cardiotoxicity of Anthracyclines) trial, a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 40 mg/d of atorvastatin administered to patients receiving anthracyclines for lymphoma, with pretreatment and 12-month posttreatment measurement of LVEF.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

STOP-CA was a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee from each site and conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki,10 Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are included in Supplement 1 and Supplement 2. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Trial functions were coordinated by the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center (CIRC) at Massachusetts General Hospital. Protocol subject registration, randomization, clinical research auditing, data and safety monitoring, and quality control were coordinated by the Office of Data Quality at Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center. Analyses were performed by the Biostatistics Program at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. An independent data monitoring committee appointed by the NHLBI oversaw participant safety, efficacy, and trial conduct.

Participants

Participants at 9 academic medical centers in the US and Canada (Supplement 3) were enrolled from January 25, 2017, to September 10, 2021. The enrollment was closed after meeting the prespecified accrual goal. Race and ethnicity information was collected as required by the funding agency and was self-reported by participants.

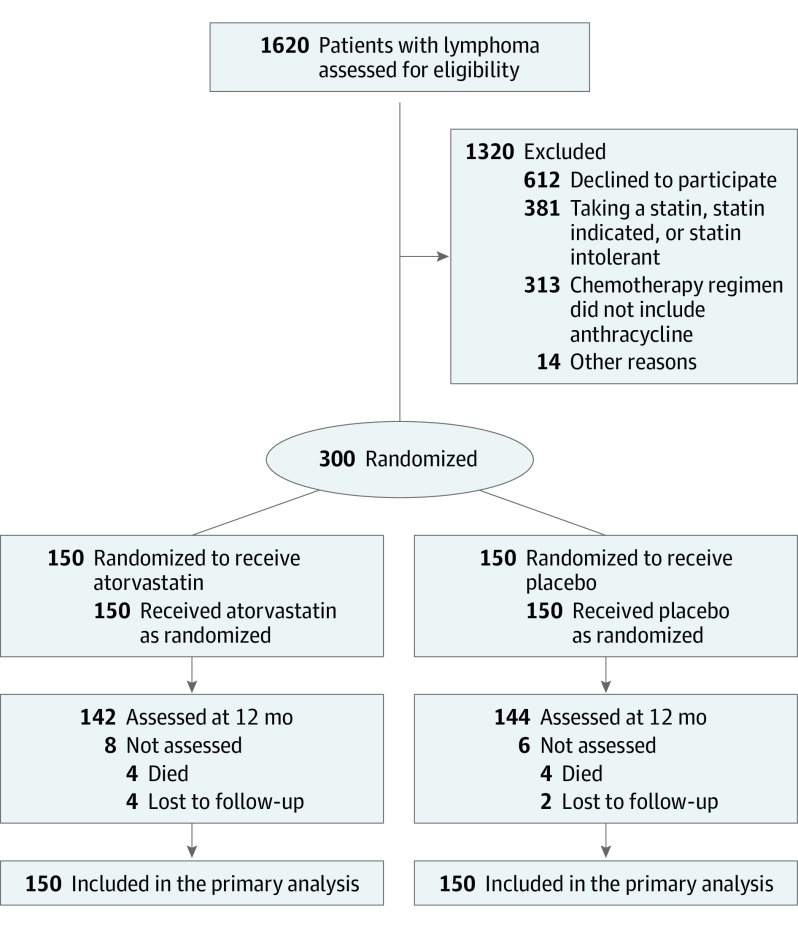

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in the Figure and in the eAppendix in Supplement 3. Patients aged 18 years or older with newly diagnosed lymphoma who were scheduled to receive anthracycline-based chemotherapy were eligible. Exclusion criteria included a persistent and unexplained pretreatment elevation of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal, standard contraindication to cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) , and treatment with a statin or clinical indication for a statin.

Figure. Participant Flow in the STOP-CA Trial.

Study Procedures

The baseline evaluation included measurement of heart rate, blood pressure, weight, blood tests, and LVEF. Visits at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months included measurement of heart rate, blood pressure, weight, and blood tests, with an LVEF measurement at 12 months. Blood tests at 1, 6, and 12 months consisted of a basic metabolic profile, blood cell count, and AST and ALT. At baseline and 3 months, a nonfasting lipid profile was added. Left ventricular ejection fraction was primarily measured using cardiac MRI (eAppendix in Supplement 3). Given the constraints of conducting outpatient research among patients with active cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic, if the period between participant identification and the scheduled first cycle of chemotherapy was restrictive, LVEF was measured using a protocol echocardiogram. Similarly, if a cardiac MRI was not feasible at 12 months, LVEF was measured using a protocol echocardiogram. To determine adherence to the study drug, a medication diary and instructions for its use were provided to participants and a monthly pill count was performed and recorded by study staff (eAppendix in Supplement 3).

Study Randomization and Interventions

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive atorvastatin, 40 mg/d orally, or placebo, starting prior to the first scheduled anthracycline infusion and continued for 12 months (eAppendix in Supplement 3). Atorvastatin, 40 mg/d, was chosen because in a small prior study of patients with varied cancers treated with anthracyclines, atorvastatin was associated with a higher posttreatment LVEF.8 Randomization was stratified according to study site.

Study End Points

The MRI measures of LVEF were performed on anonymized images in a core laboratory at CIRC. Echocardiographic measures of LVEF were performed on anonymized images in a core laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania. The primary outcome was the proportion of participants in each group with an absolute decline in LVEF of 10% or greater from prior to chemotherapy to a final value of less than 55% over the 12-month study. Multiple potential definitions of anthracycline-associated cardiac dysfunction have been published.11 This end point was chosen as an accepted threshold for the definition of cardiotoxicity in clinical studies12,13 and guidelines,14 and parallels the US Food and Drug Administration definition of cardiotoxicity with doxorubicin.11 A secondary prespecified outcome was the proportion of participants with an absolute decline in LVEF of 5% or greater in LVEF from prior to chemotherapy to a final value of less than 55% over the 12-month study period. Exploratory analyses included the absolute reduction in LVEF by treatment group and subgroup analyses testing the effect of atorvastatin or placebo on the absolute LVEF change at 12 months by sex, age (older than study median), higher cumulative anthracycline dose (in doxorubicin equivalents; ≥250 mg/m2),15 body mass index (≥30; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), and cancer type (Hodgkin lymphoma vs non-Hodgkin lymphoma). All anthracycline doses were converted to doxorubicin equivalents. Other exploratory end points included the proportion of participants in each study group who developed heart failure by 24 months of follow-up and overall survival between those randomized to placebo vs those randomized to atorvastatin. Overall survival was defined as the period from the day of randomization (day 1) until death due to any cause. Adverse events of special interest were prespecified pooled categories of adverse events, as defined in the eAppendix in Supplement 3.

Power Calculation

The study planned to enroll 300 participants. The base-case assumptions were that 20% of the placebo group and 5% of the atorvastatin group would meet the primary end point.3,8,16 The anticipated dropout rate was 10%, estimating a 1-year mortality of approximately 5% to 6%,17,18 and atorvastatin-related adverse effects in approximately 4% to 5%.19 The remaining anticipated 270 participants would provide greater than 90% power to detect a 15% difference in the proportions achieving the primary end point at a 2-sided significance level of .05. The study was not powered to detect a difference in the incidence of heart failure.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for the distribution of variables; continuous variables were summarized as means with standard deviations or medians with full ranges, and categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. All statistical analyses were performed based on intention to treat; study participants were included in the analyses if they could not complete the study protocol due to potential study drug–related toxicity or if they started anthracyclines but did not complete the entire scheduled anthracycline protocol. A Fisher exact test was used to determine whether statin use was associated with cardiac dysfunction (primary and secondary end points) and to determine the association with incidence of heart failure. The change in LVEF from baseline to month 12 was summarized descriptively and tested for association in prespecified subgroup analyses with Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to generate survival curves, and the comparisons between the groups were performed using the log-rank test. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Analyses were performed with R version 4.2 (R Core Team).

Results

Study Population

Three hundred participants were recruited and randomly assigned to receive atorvastatin (n = 150) or placebo (n = 150) (Figure). Enrollment occurred between January 25, 2017, and September 10, 2021. The mean age of participants was 50 (SD, 17) years, and 163 (54%) were aged 50 years or older. The population was 53% male; 3% identified as Black or African American, 89% identified as White, and 6% reported being of Latino or Hispanic ethnicity. The average body mass index was 27.7 and was 30 or above among 32% of the trial population. The study population consisted of 220 participants (73%) with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and 80 (37%) with Hodgkin lymphoma. All participants were treated with anthracyclines with a doxorubicin equivalent average cumulative dose of 264 (SD, 60) mg/m2; 73% were treated with a cumulative anthracycline dose of 250 mg/m2 or greater and 55% were treated with a cumulative anthracycline dose of 300 mg/m2. No study participant was treated with liposomal doxorubicin or dexrazoxane. In total, 33 participants (11%) were treated with radiation therapy, with only 4 participants having radiation treatment that involved the cardiac silhouette. These cancer treatment parameters were similar between study groups (Table 1). The chemotherapy regimens were also similar between study groups (eTable 1 in Supplement 3). At least 1 dose of study drug was taken by all study participants, and study drug adherence was high and recorded in 91% of participants and was similar between study groups (Table 1). The baseline characteristics and cancer treatments of participants who were and were not adherent to the study drug were compared and were similar between groups (eTable 2 in Supplement 3).

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Atorvastatin (n = 150) | Placebo (n = 150) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| Mean (SD) | 50 (17) | 49 (16) |

| Median (range) | 51 (20-91) | 52 (20-83) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Female | 68 (45) | 74 (49) |

| Male | 82 (55) | 76 (51) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||

| Asian | 4 (3) | 7 (5) |

| Black or African American | 5 (3) | 4 (3) |

| White | 135 (90) | 131 (87) |

| Unknown | 6 (4) | 8 (5) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, No. (%) | 11 (7) | 8 (5) |

| Body mass indexa | ||

| Mean (SD) | 28 (6.2) | 28 (6.1) |

| Median (range) | 27 (14.20-52) | 27 (17-50) |

| No. (%) | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 2 (1) | 6 (4) |

| Normal weight (18-24.9) | 48 (32) | 51 (34) |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 56 (37) | 51 (34) |

| Obese (30-34.9) | 25 (17) | 27 (18) |

| Severely obese (≥35) | 19 (13) | 15 (10) |

| Type of lymphoma, No. (%) | ||

| B-cell | 104 (69) | 102 (68) |

| Hodgkin | 37 (25) | 43 (29) |

| T-cell | 9 (6) | 5 (3) |

| ECOG Performance Status Scale, No. (%)b | ||

| Grade 0 (fully active) | 112 (75) | 104 (69) |

| Grade 1 | 29 (19) | 36 (24) |

| Grade 2 | 4 (3) | 7 (5) |

| Grade 3 (limited self-care) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Unknown | 4 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Cardiac medications, No. (%) | ||

| ARB or ACE inhibitor | 7 (5) | 10 (7) |

| β-Blocker | 7 (5) | 3 (2) |

| Aspirin | 10 (7) | 6 (4) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 4 (3) | 4 (3) |

| Other (eg, diuretic, aldosterone antagonist) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Cardiac risk factors, No. (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 14 (9) | 20 (13) |

| Smoking history | 29 (19) | 32 (21) |

| Current | 6 (4) | 8 (5) |

| Sleep apnea | 4 (3) | 7 (5) |

| Diabetes | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Cumulative anthracycline dose in doxorubicin equivalents, mg/m2 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 268 (58) | 260 (62) |

| Median (range) | 300 (100-308) | 300 (50-312) |

| Radiation treatment, No. (%)c | 12 (8) | 21 (14) |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Percentages may sum to more than 100% due to rounding. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status Scale indicates increasing levels of disability, with 0 indicating fully active; 1, restricted in strenuous activity; 2, restricted in work activity but ambulatory and capable of self-care; 3, capable of limited self-care; 4, completely disabled; and 5, deceased.

Four participants had radiation treatment that involved the cardiac silhouette.

Primary Outcome

At baseline, among the entire cohort, the mean LVEF was 63% (SD, 4.6%). In total, 286 participants (95%) completed the trial. The follow-up mean LVEF among the entire cohort was 58% (SD, 5.9%), with a mean decrease of 5% in LVEF among the entire study cohort over the 12-month study period. At 12-month follow-up, 46 participants among the entire cohort (15%) had a decline in LVEF of 10% or greater from prior to chemotherapy to a final value of less than 55%. Theere was 13 events among the 150 patients in the atorvastatin group and 33 events among the 150 patients in the placebo group, for an incidence of the primary end point at 12 months of 9% in the atorvastatin group and 22% in the placebo group (P = .002) (eFigure 1A in Supplement 3). The odds of a 10% or greater decline in LVEF to a final value of less than 55% after anthracycline treatment was almost 3 times greater for participants randomized to placebo compared with those randomized to atorvastatin (odds ratio, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.4-6.4). The number needed to treat with atorvastatin for 1 additional participant to avoid a decline in LVEF of 10% or greater from prior to chemotherapy to a final value of less than 55% was 7.7. Among the 286 participants with follow-up data, 77% had their LVEF measured with MRI, with no difference between groups (eTable 3 in Supplement 3). In an analysis restricted to participants with MRI follow-up only, the beneficial effect of atorvastatin on the primary outcome was unchanged (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3). When the analysis of the primary outcome was restricted to only those who were adherent to the study drug, the findings were also unchanged; the rate of the primary outcome was 9% in the atorvastatin group and 21% in the placebo group (P = .006). Among participants who met the primary study end point, the mean reduction in LVEF was 14% (SD, 3.95%). In comparison, among participants who did not meet the primary study end point, the mean reduction n LVEF was 3% (SD, 4.7%). Participant demographics, cancer characteristics, cancer therapy, study drug adherence, and LVEF change among participants who did and did not meet the primary study end point are presented in eTable 4 in Supplement 3.

Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes

At 12-month follow-up, among the entire cohort, 64 (21%) had a decline in LVEF of 5% or greater from prior to chemotherapy to a final value of less than 55% over the 12-month study. The incidence of this secondary outcome was 13% in the atorvastatin group and 29% in the placebo group (P = .001) (eFigure 1B in Supplement 3). In the atorvastatin group, the mean pretreatment LVEF was 62.9% (SD, 4.5%) and mean LVEF at 12 months was 58.8% (SD, 5.9%), a decrease of 4.1% (6.1%). In the placebo group, the mean pretreatment LVEF was 62.5% (SD, 4.9%) and the mean LVEF at 12 months was 57.1% (SD, 5.4%), an average decrease of 5.4% (SD, 6.1%). Thus, overall, there was only a minor difference of 1.3% in the decline in LVEF at 12 months between those randomized to atorvastatin and placebo (P = .03). In subgroup analyses, the beneficial effect of atorvastatin therapy on LVEF decline at 12 months was observed in participants who were older than the median age (52 years), among those who were treated with a cumulative dose of anthracyclines of 250 mg/m or greater,2,15 among those who were obese (body mass index ≥30), and among females (Table 2). In an exploratory analysis, the rates of incident heart failure by group at 24 months of follow-up were compared. At the time of this analysis, 93% of the study population had either died or reached 24 months of follow-up. Among these, there were 13 heart failure events (4%). Of the 13 participants with a heart failure event, 11 also met the primary study end point. There were 9 heart failure events (6%) in the placebo group and 4 heart failure events (3%) in the atorvastatin group; this different was not statistically significant (P = .26). There was no difference in overall survival between those randomized to placebo or atorvastatin (P = .67) (eFigure 3 in Supplement 3). Changes in LVEF from baseline to follow-up among participants randomized to placebo, by prespecified categories, are shown in eFigure 4 in Supplement 3.

Table 2. Change in LVEF From Pretreatment to Month 12 by Subgroup.

| Subgroups | Mean (SD) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atorvastatin | Placebo | ||

| Female | |||

| Month 0 | 63.9 (4.1) | 63.4 (4.7) | .95 |

| Month 12 | 61.0 (4.0) | 57.9 (5.6) | .001 |

| Difference | −3.1 (4.6) | −5.4 (6.5) | .02 |

| Absolute difference | 4.2 (3.6) | 6.8 (5.0) | .001 |

| Male | |||

| Month 0 | 62.0 (4.4) | 61.6 (5.0) | .93 |

| Month 12 | 57.1 (6.6) | 56.2 (5.1) | .10 |

| Difference | −4.9 (7.0) | −5.4 (5.8) | .37 |

| Absolute difference | 6.3 (5.7) | 6.4 (4.7) | .64 |

| Age, older than median (52 y) | |||

| Month 0 | 63.7 (4.4) | 63.0 (5.0) | .57 |

| Month 12 | 59.4 (5.1) | 56.2 (5.8) | .001 |

| Difference | −4.4 (5.3) | −6.6 (5.6) | .03 |

| Absolute difference | 5.5 (4.2) | 7.1 (5.0) | .08 |

| Age, median or younger (52 y) | |||

| Month 0 | 62.1 (4.2) | 62.1 (4.8) | .71 |

| Month 12 | 58.3 (6.5) | 57.8 (4.9) | .12 |

| Difference | −3.8 (6.7) | −4.5 (6.4) | .32 |

| Absolute difference | 5.2 (5.6) | 6.2 (4.7) | .06 |

| Anthracycline dose, doxorubicin equivalents, ≥250 mg/m2 | |||

| Month 0 | 63.1 (4.4) | 62.5 (5.1) | .66 |

| Month 12 | 58.8 (5.3) | 56.3 (5.4) | <.001 |

| Difference | −4.3 (5.7) | −6.2 (6.1) | .01 |

| Absolute difference | 5.3 (4.8) | 7.1 (5.0) | .005 |

| Anthracycline dose, doxorubicin equivalents, <250 mg/m2 | |||

| Month 0 | 62.2 (4.1) | 62.5 (4.4) | .32 |

| Month 12 | 59.1 (7.6) | 58.5 (5.1) | .34 |

| Difference | −3.1 (7.1) | −3.8 (5.8) | .67 |

| Absolute difference | 5.5 (5.5) | 5.5 (4.3) | .95 |

| Obese (BMI ≥30) a | |||

| Month 0 | 62.5 (3.2) | 62.8 (5.9) | .68 |

| Month 12 | 59.6 (7.3) | 57.1 (5.6) | .02 |

| Difference | −3.0 (6.3) | −5.6 (5.7) | .02 |

| Absolute difference | 4.5 (5.4) | 6.5 (4.7) | .02 |

| Not obese (BMI <30) a | |||

| Month 0 | 63.0 (4.8) | 62.4 (4.5) | .74 |

| Month 12 | 58.6 (5.3) | 57.0 (5.3) | .01 |

| Difference | −4.5 (5.9) | −5.4 (6.3) | .27 |

| Absolute difference | 5.7 (4.8) | 6.7 (4.9) | .16 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | |||

| Month 0 | 63.3 (4.6) | 62.8 (5.1) | .89 |

| Month 12 | 58.4 (6.3) | 56.6 (5.5) | .003 |

| Difference | −5.0 (6.3) | −6.1 (6.2) | .08 |

| Absolute difference | 5.9 (5.5) | 7.1 (5.1) | .04 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | |||

| Month 0 | 61.6 (3.3) | 61.7 (4.4) | .73 |

| Month 12 | 60.1 (4.2) | 58.2 (4.8) | .08 |

| Difference | −1.4 (4.3) | −3.8 (5.5) | .10 |

| Absolute difference | 3.8 (2.3) | 5.4 (3.9) | .16 |

Body mass index (BMI) is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Laboratory and Nonlaboratory Parameters

Participants’ resting heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, weight, and laboratory test results are reported across visits in eTable 5 in Supplement 3. Prior to treatment, there were no differences in total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels between the 2 study groups. Participants receiving atorvastatin experienced an expected decline in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol compared with pretreatment levels. There were no marked or unexpected changes in other tested laboratory parameters. Prospective data on participants’ other cardiac MRI parameters are reported in eTable 6 in Supplement 3.

Adverse Events

At 12-month follow-up, 8 study participants (2.6%) had died; there were 4 deaths in the placebo group and 4 in the atorvastatin group. Over the 12-month follow-up, 49 (16%) participants reported muscle pain, 28 (19%) in the atorvastatin group and 21 (14%) in the placebo group (P = .35) (eTable 7 in Supplement 3). However, no study participant had evidence of myositis (elevated creatine kinase level). Among the entire cohort, 51 participants (17%) developed elevated AST and ALT levels during the study period. There were 2 grade 4 elevations in AST and ALT, 1 in each group. There was no difference when the atorvastatin and placebo groups were compared (18% vs 16%). Six patients (2%) developed kidney failure over the 12-month study period, 2 in the atorvastatin group and 4 in the placebo group.

Discussion

Among 300 adult participants with lymphoma who were treated with anthracyclines, atorvastatin, 40 mg/d, reduced the risk of cardiac dysfunction over 12 months compared with placebo.

Several cardioprotective treatments have been tested to reduce anthracycline-associated cardiac dysfunction, with modest effects.20,21,22,23 A key advantage of statins is that they generally have an acceptable risk-benefit ratio, and their use is not limited by the adverse hemodynamic changes associated with therapies such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition or β-blockade.20,21 The hypothesis was supported both by basic science experiments and by observational studies7; however, a recent randomized trial of atorvastatin, 40 mg/d, administered over 24 months failed to show a difference in the absolute decline in LVEF after anthracycline treatment.9 Specifically, the mean LVEF values were 61.7% before treatment and 57.4% at 24 months in the placebo group and 62.6% before treatment and 57.7% at 24 months in the atorvastatin group, with a 24-month decline in LVEF of 3.3% in the placebo group and 3.2% among those randomized to atorvastatin. Several important differences between studies exist that merit consideration. In the previous study, the dose of anthracyclines was lower, the cohort was younger, and breast cancer was the indication in 85%, with the remaining 15% of that population being treated for lymphoma. The risk of cardiac dysfunction with anthracyclines is dose dependent,24 higher in patients at elevated cardiovascular risk,15 and related to the cancer type; thus, the rate of cardiac dysfunction is lower among patients with breast cancer compared with patients with lymphoma.25,26 This difference in risk of anthracycline-associated cardiac dysfunction between the 2 study cohorts is reflected in the rate of the primary end point. When applying similar criteria (an LVEF reduction of 10%), 11% of participants in the previous study developed cardiac dysfunction compared with 21% in our study. In support, several factors were identified in our study that were predictive of the beneficial effect of atorvastatin on posttreatment LVEF, including a higher anthracycline dose and older age.

Over 12 months of follow-up, approximately 1 in 6 participants who were treated with anthracyclines experienced a decline in LVEF of 10% or greater to a final value of less than 55%. This decline in LVEF is similar to that reported in other single and multicenter studies and this magnitude of decline has been reported to lead to an increased risk of subsequent development of clinical heart failure.26 The present study also highlights the impact of end-point selection in studies among patients at risk of cardiac dysfunction with cancer therapies. The primary end point in STOP-CA was the proportion in each study group with a 10% or greater decline in LVEF. In contrast, some studies have selected the absolute difference in the decline in LVEF as the primary end point.9,20,21 In STOP-CA, when the entire cohort was compared, there was only a minor difference of 1.3% in LVEF at 12 months between groups, suggesting that for a proportion of the anthracycline population, atorvastatin may have little benefit; however, atorvastatin has a substantial benefit among patients at higher risk of anthracycline-associated cardiac systolic dysfunction. However, despite the differences between study design, availability of baseline and follow-up data, study drug adherence, the study population, and the end point chosen, broadly conflicting data exist on whether statins protect against anthracycline-associated cardiac dysfunction. Thus, a reasonable approach would be to continue statins among patients who are being treated with anthracyclines; consider statins in patients who have a borderline indication for statins for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; and among patients with no traditional indication for a statin, consider a statin in those who are at high risk of anthracycline-associated cardiotoxicity. Individuals with higher risk include those who are older, those with a borderline LVEF at baseline, and those being treated with a higher cumulative dose of anthracyclines.

This study was not designed to provide mechanistic insight into why statins may protect against anthracycline-associated cardiac dysfunction. While the mechanisms of cardiotoxicity are not fully understood, robust data suggest that anthracyclines cause oxidative damage, leading to cardiac cell death and reduced cardiac function, further leading to heart failure. In mice treated with anthracyclines, statins reduced oxidative stress, preserved calcium handling, attenuated myocardial cell death, and preserved cardiac function.4,5,27 A key role for topoisomerase II has been shown in anthracycline-associated cardiotoxicity.28 Statins inhibit small Ras homologous GTPases, which reduces topoisomerase II inhibition and the generation of reactive oxygen species.29

This study has several strengths. Despite the challenges of performing an outpatient study among patients with cancer receiving active chemotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic, the study was fully enrolled, 100% of participants had a baseline measure of LVEF, follow-up was available in more than 90%, and the study drug adherence was higher than 90%. The study intervention was safe, with no serious study-related adverse effects, and had no significant effect on hemodynamic parameters such as blood pressure. An additional key strength of statins is that there are no data that suggest statins may adversely affect cancer outcomes. For example, in observational studies totaling 777 patients with lymphoma, statin use had no impact on overall survival or event-free survival.30,31 In contrast, a number of laboratory studies have indicated that statins have direct cytotoxic effects on lymphoma cell lines,32,33,34 and in an observational study among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, concomitant statin use was associated with a 24% higher complete response rate.34

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, LVEF was applied as a surrogate for the development of heart failure. However, the end point was a large change in LVEF, beyond the measurement variability, below the modality lower limits of normal, and consistent with guideline recommendations and prior studies.12,14 Second, although STOP-CA enrolled nearly 50% women, the study did not enroll a racially or ethnically diverse population, an important limitation. Third, not all study participants had an MRI of the heart at baseline and at follow-up. Due to the challenges associated with enrolling and follow-up of a population with active cancer during several years of a pandemic, the study allowed flexibility to substitute LVEF derived from a protocol-driven echocardiogram with measurement performed in a core echocardiography laboratory by expert blinded readers. In analyses restricted to patients with an MRI only at follow-up, the results were unchanged. Finally, this trial was a single-dose study given over a 12-month period, and it is not known if there is any dose or length-of-treatment effect.

Conclusions

Among study participants with lymphoma who were being treated with anthracyclines, prophylactic use of atorvastatin over 12 months was associated with a lower rate of cardiac systolic dysfunction. These data support the use of atorvastatin among patients being treated with anthracyclines, in whom prevention of cardiac systolic dysfunction is important.

Educational Objective: To identify the key insights or developments described in this article.

-

This study evaluated the potential for atorvastatin to reduce or prevent cardiac dysfunction due to anthracycline treatment for lymphoma. Why was atorvastatin chosen?

Atorvastatin has fewer interactions with anthracycline than alternative statins.

Atorvastatin initiated prior to anthracyclines was associated with higher left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at follow-up in 1 previous trial.

Atorvastatin is inexpensive and readily available, making it an ideal intervention for this pragmatic trial.

-

The primary outcome for this study was the proportion of participants with a decline in LVEF of 10% or greater to a final value of less than 55%. What did the authors find?

Most participants experienced a decline in LVEF of 10% or greater over the course of treatment regardless of treatment with atorvastatin.

Adverse effects of atorvastatin led to much greater discontinuation of therapy in the treatment group than in the randomization group.

The odds of the primary outcome were almost 3 times greater for participants randomized to the placebo group.

-

What did the authors conclude would be a reasonable approach for the use of statins to protect against anthracycline-associated cardiac dysfunction?

Consider statin therapy for patients with no traditional indication but who are at high risk of anthracycline-associated cardiotoxicity.

Discontinue statin therapy in patients already taking statins who are undergoing cancer treatment with anthracyclines.

Follow standard guidelines for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease as if the patient were not undergoing anthracycline therapy.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

STOP-CA Investigators

List of Collaborators

Data Safety Monitoring Board

eAppendix. Supplementary Methods

eFigure 1. Effect of Atorvastatin or Placebo on the Cardiac Dysfunction After Anthracyclines

eFigure 2. Reduction in the LVEF Only Among Patients With a Cardiac MRI-Derived LVEF at 12 Months

eFigure 3. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival

eFigure 4. Change in LVEF From Baseline to Follow-up Among Participants Who Were Treated With Placebo by Pre-specified Categories

eTable 1. Cancer Treatment Regimens

eTable 2. Patient Demographics, Cancer Characteristics, Drug Exposure, Cancer Treatments by Group and by Study Drug Adherence

eTable 3. Participants With Cardiac MRI at Pretreatment and Follow-up

eTable 4. Participant Demographics, Cancer Characteristics, Drug Exposure, Radiation, and LVEF Change by Primary Outcome

eTable 5. Participant Non-imaging Measures and Laboratory Values Across Study Visits

eTable 6. Participant Cardiac MRI Measures Across Study Visits

eTable 7. Adverse Events of Special Interest Across Study Visits

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Lyon AR, López-Fernández T, Couch LS, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2022 ESC guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J. 2022;43(41):4229-4361. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hequet O, Le QH, Moullet I, et al. Subclinical late cardiomyopathy after doxorubicin therapy for lymphoma in adults. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1864-1871. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Limat S, Demesmay K, Voillat L, et al. Early cardiotoxicity of the CHOP regimen in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(2):277-281. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riad A, Bien S, Westermann D, et al. Pretreatment with statin attenuates the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin in mice. Cancer Res. 2009;69(2):695-699. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramanjaneyulu SV, Trivedi PP, Kushwaha S, Vikram A, Jena GB. Protective role of atorvastatin against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity and testicular toxicity in mice. J Physiol Biochem. 2013;69(3):513-525. doi: 10.1007/s13105-013-0240-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Qadir H, Bobrowski D, Zhou L, et al. Statin exposure and risk of heart failure after anthracycline- or trastuzumab-based chemotherapy for early breast cancer: a propensity score–matched cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(2):e018393. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.018393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seicean S, Seicean A, Plana JC, Budd GT, Marwick TH. Effect of statin therapy on the risk for incident heart failure in patients with breast cancer receiving anthracycline chemotherapy: an observational clinical cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(23):2384-2390. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acar Z, Kale A, Turgut M, et al. Efficiency of atorvastatin in the protection of anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(9):988-989. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hundley WG, D’Agostino R, Crotts T, et al. Statins and left ventricular ejection fraction following doxorubicin treatment. NEJM Evid. 2022;1(9):EVIDoa2200097. doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2200097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez IE, Taveras Alam S, Hernandez GA, Sancassani R. Cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction: an overview for the clinician. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2019;13:1179546819866445. doi: 10.1177/1179546819866445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thavendiranathan P, Negishi T, Somerset E, et al. ; SUCCOUR Investigators . Strain-guided management of potentially cardiotoxic cancer therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):392-401. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López-Sendón J, Álvarez-Ortega C, Zamora Auñon P, et al. Classification, prevalence, and outcomes of anticancer therapy-induced cardiotoxicity: the CARDIOTOX Registry. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(18):1720-1729. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plana JC, Galderisi M, Barac A, et al. Expert consensus for multimodality imaging evaluation of adult patients during and after cancer therapy: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27(9):911-939. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, et al. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):893-911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drafts BC, Twomley KM, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Low to moderate dose anthracycline-based chemotherapy is associated with early noninvasive imaging evidence of subclinical cardiovascular disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(8):877-885. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235-242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS, et al. Randomized trial of bendamustine-rituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood. 2014;123(19):2944-2952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-531327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, et al. ; Treating to New Targets (TNT) Investigators . Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(14):1425-1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosch X, Rovira M, Sitges M, et al. Enalapril and carvedilol for preventing chemotherapy-induced left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with malignant hemopathies: the OVERCOME trial (Prevention of Left Ventricular Dysfunction With Enalapril and Carvedilol in Patients Submitted to Intensive Chemotherapy for the Treatment of Malignant Hemopathies). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(23):2355-2362. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulati G, Heck SL, Ree AH, et al. Prevention of Cardiac Dysfunction During Adjuvant Breast Cancer Therapy (PRADA): a 2 × 2 factorial, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of candesartan and metoprolol. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(21):1671-1680. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boekhout AH, Gietema JA, Milojkovic Kerklaan B, et al. Angiotensin II-receptor inhibition with candesartan to prevent trastuzumab-related cardiotoxic effects in patients with early breast cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(8):1030-1037. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avila MS, Ayub-Ferreira SM, de Barros Wanderley MR Jr, et al. Carvedilol for prevention of chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity: the CECCY trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(20):2281-2290. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander J, Dainiak N, Berger HJ, et al. Serial assessment of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity with quantitative radionuclide angiocardiography. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(6):278-283. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197902083000603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Tan TC, Halpern EF, et al. Major cardiac events and the value of echocardiographic evaluation in patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(3):442-446. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.04.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee ARYB, Yau CE, Low CE, et al. Natural progression of left ventricular function following anthracyclines without cardioprotective therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(2):512. doi: 10.3390/cancers15020512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim YH, Park SM, Kim M, et al. Cardioprotective effects of rosuvastatin and carvedilol on delayed cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin in rats. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2012;22(6):488-498. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2012.678406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Liu X, Bawa-Khalfe T, et al. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2012;18(11):1639-1642. doi: 10.1038/nm.2919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wartlick F, Bopp A, Henninger C, Fritz G. DNA damage response (DDR) induced by topoisomerase II poisons requires nuclear function of the small GTPase Rac. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(12):3093-3103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nowakowski GS, Maurer MJ, Habermann TM, et al. Statin use and prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):412-417. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ennishi D, Asai H, Maeda Y, et al. Statin-independent prognosis of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving rituximab plus CHOP therapy. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(6):1217-1221. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi XF, Zheng L, Lee KJ, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors induce apoptosis of lymphoma cells by promoting ROS generation and regulating Akt, Erk and p38 signals via suppression of mevalonate pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4(2):e518. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katano H, Pesnicak L, Cohen JI. Simvastatin induces apoptosis of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines and delays development of EBV lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(14):4960-4965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305149101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gouni S, Strati P, Toruner G, et al. Statins enhance the chemosensitivity of R-CHOP in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2022;63(6):1302-1313. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2021.2020782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

STOP-CA Investigators

List of Collaborators

Data Safety Monitoring Board

eAppendix. Supplementary Methods

eFigure 1. Effect of Atorvastatin or Placebo on the Cardiac Dysfunction After Anthracyclines

eFigure 2. Reduction in the LVEF Only Among Patients With a Cardiac MRI-Derived LVEF at 12 Months

eFigure 3. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival

eFigure 4. Change in LVEF From Baseline to Follow-up Among Participants Who Were Treated With Placebo by Pre-specified Categories

eTable 1. Cancer Treatment Regimens

eTable 2. Patient Demographics, Cancer Characteristics, Drug Exposure, Cancer Treatments by Group and by Study Drug Adherence

eTable 3. Participants With Cardiac MRI at Pretreatment and Follow-up

eTable 4. Participant Demographics, Cancer Characteristics, Drug Exposure, Radiation, and LVEF Change by Primary Outcome

eTable 5. Participant Non-imaging Measures and Laboratory Values Across Study Visits

eTable 6. Participant Cardiac MRI Measures Across Study Visits

eTable 7. Adverse Events of Special Interest Across Study Visits

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement