Abstract

Crosslinked, degradable, and cell adhesive hydrogel microfibers were synthesized via interfacial polymerization employing tetrazine ligation, an exceptionally fast bioorthogonal reaction between strained trans-cyclooctene (TCO) and s-tetrazine (Tz). A hydrophobic trisTCO crosslinker and homo-difunctional poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based macromers with the tetrazine group conjugated to PEG via a stable carbamate (PEG-bisTz1) bond or a labile hydrazone (PEG-bisTz2) linkage were synthesized. After laying an ethyl acetate solution of trisTCO over an aqueous solution of bisTz macromers, mechanically robust microfibers were continuously pulled from the oil-water interface. The resultant microfibers exhibited comparable mechanical and thermal properties, but different aqueous stability. Combining PEG-bisTz2 and PEG-bisTz3 with a dangling arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) peptide in the aqueous phase yielded degradable fibers that supported the attachment and growth of primary vocal fold fibroblasts. The degradable and cell-adhesive hydrogel microfibers are expected to find utility in a wide array of tissue engineering applications.

Keywords: Hydrogel microfiber, degradable, interfacial polymerization, tetrazine ligation, hydrazone

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION:

The natural extracellular matrix (ECM) is comprised of a wide variety of biomolecules that provide important biophysical and biochemical cues to cells during tissue development, remodeling, disease, and regeneration. Cells interact dynamically with the ECM, engaging with matrix bound ligands through cell surface receptors, sensing changes in matrix morphology and mechanical properties, and communicating with neighboring cells through ECM-sequestered growth factors and cytokines to inform consequential cell fate decisions.1,2,3 Cellular adhesion, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis, as well as extracellular processes including remodeling and degradation, are outcomes of the bidirectional crosstalk between cells and their ECM.4,5

Fibrous ECM proteins are predominantly represented by collagens, elastins, fibronectins, and laminins, with collagen being the most abundant.6 Fibrillar collagens (types I-III, V and XI) are made up of trimeric α-helical polypeptide strands of repeating Gly-X-Y amino acids (with X and Y often being proline and 4-hydroxyproline, respectively).7 Fibrils are formed from identical homo- or unique hetero-trimers of α chains, which twist together in right handed helices, stabilized by the presence of glycine every third residue, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatics.8 Fibrils can further assemble into supramolecular arrangements including fibers (>10 μm) and networks. Collagens provide substantial tensile strength to the ECM, limiting tissue distensibility, as well as regulate cell adhesion, support chemotaxis and migration, and guide tissue development.6, 9 Non-collagenous fibrous proteins also play essential roles in cellular migration. For example, fibronectin is crucial in directing ECM organization and mediating cell attachment, perhaps best exemplified by its ubiquitous arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) cell adhesion sequence. RGD represents the cell attachment site of several adhesive ECM, blood, and cell surface proteins, and nearly half of the known integrins can recognize it in their adhesion protein ligands.10, 11

Synthetic and natural material systems that recapitulate the microstructure and function of the native extracellular milieu have been highly sought for their potential to repair or model tissues in healthy and disease states.12-15 Fabrication approaches that afford fibrillar architectures as well as permit incorporation of recognizable sequences for cell adhesion and degradation are promising avenues toward replicating the natural ECM. Several fabrication approaches to imitate the micro- and nano- filamentous ECM architecture have emerged. Wet spinning, employing an electro-stretching process, was demonstrated to produce biopolymer fibers that displayed topographic alignment and guided cell orientation.16 These fibers were naturally biocompatible; however, their large size (~high 10s to 100s of microns) restricts their broader applicability as ECM-mimetic scaffolds. In contrast, fibers produced by self-assembly are generally much smaller than fibrous proteins, with diameters on the order of ECM fibrils rather than fibers.17 These size limitations, along with the inferior mechanical properties, restrict their utility as 3D cell culture matrices.

Electrospinning, perhaps the most widely adopted fiber fabrication approach, overcomes size constraints of the other methods. Fibers produced by electrospinning span a wide range of diameters from nano- to micrometer sizes comparable to native fibrous proteins.18 Tissue engineering applications of electrospinning have historically been limited by the hydrophobicity and/or stiffness of fibers produced using classic semi-crystalline polyesters. To overcome these limitations, core-shell fibers having a stiff, hydrophobic poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) core and a soft, hydrophilic and cell adhesive hyaluronic acid (HA) shell were produced via the combination of electrospinning and covalent layer-by-layer deposition.19 Hydrophilic polymers have also been electrospun into fibrous meshes; to prevent fiber dissolution, covalent crosslinking during spinning is necessary.20-22 HA-based, proteolytically degradable fibrous scaffolds were produced using a macromer with photo-crosslinkable methacrylate groups linked to the HA backbone through a protease degradable peptide linker.23 Establishment of 3D structures is non-trivial; in general, scaffolds prepared by traditional electrospinning methods are flat fibrous meshes. Recent approaches to develop hierarchical fibrous tissue engineering matrices have entailed the formation of monolithic gels, followed by mechanical extrusion/fragmentation, and re-formation of hydrogels with fibrous features.24-26 The inherent high porosity of the resultant 3D constructs allowed cells to physically migrate within or remodel their microenvironment. However, the arduous multistep fabrication processes introduce potential sources of batch-to-batch inconsistencies and leave much room for optimization. Moreover, the scalability of these systems has yet to be demonstrated.

Herein, we introduce a versatile method for producing hydrogel microfibers and hierarchical scaffolds that mimic key structural and functional characteristics of fibrous proteins found in the native ECM. Specifically, a diffusion controlled interfacial tetrazine ligation reaction was employed to produce crosslinked hydrogel microfibers that are cell adhesive and hydrolytically degradable. Implicit in the versatility of this approach is the biorthogonal nature of the tetrazine ligation reaction— an unnatural, inverse-electron demand Diels-Alder cycloaddition between s-tetrazines (Tz) and trans-cyclooctenes (TCO).27, 28 This reaction features fast kinetics, high selectivity at low concentrations and importantly, orthogonality toward biological functionalities, overcoming the poor functional group tolerance that historically has afflicted classical interfacial polymerization strategies.29, 30 The broad utility of the tetrazine ligation in the development of novel biomaterials is well documented.19, 31-33

Previously, we demonstrated that interfacial polymerization could be used to construct mechanically robust, hydrogel microfibers capable of serving as substrates for mammalian cell culture.33, 34 These fibers were built only from non-degradable monomers, which could limit their applications in biological systems. Here, we evaluate the tunability of this approach by combining poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based tetrazine macromers with different linker chemistry. Specifically, tetrazine was conjugated to PEG via a stable carbamate (PEG-bisTz1) linkage or a labile hydrazone (PEG-bisTz2) bond. We further investigate the synthesis of hydrolytically degradable microfibers that were suitable for cell culture by modular incorporation of PEG-bisTz2 alongside PEG-bisTz3 with a dangling RGDSP peptide during interfacial tetrazine ligation. Finally, we demonstrate facile preparation of woven meshes and tubular constructs simply by changing the geometry and orientation of the collection frame during polymerization, without additional fabrication steps.

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION:

2.1. Materials.

All 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-protected amino acids were purchased from ChemPep (Wellington, FL). Rink amide resin was ordered from Advanced Automated Peptide Protein Technologies (AAPPTEC, Louisville, KY). Ethyl(hydroxyimino)cyanoacetate was purchased from EMD Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA). Poly(ethylene glycol) diamine (PEG-bisNH2, Mn =7.5 kDa), poly(ethylene glycol) disuccinimidyl carboxymethyl ester (PEG-disNHS, Mn = 7.5 kDa) and alpha amino, omega-carboxyl poly(ethylene glycol) (NH2-PEG-COOH, Mn = 3.5 kDa) were purchased from JenKem Technology USA (Plano, TX). Cy-5 methyltetrazine was purchased from Click Chemistry Tools (Scottsdale, AZ). N, N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), piperidine, hydrazine, Dess-Martin periodinane (DMP), pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS), sodium acetate, and acetic acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Triethylamine (TEA), diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), triisopropylsilane (TIPS), tris-(2-aminoethyl)amine, and other general solvents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) and used without further purification. Deuterated solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope. (rel-1R,8S,9R,4E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-ene-9-ylmethanol, (1R,8S,9R,4E)-bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-ylmethyl(4-nitrophenyl) carbonate, (4-(6-phenyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazin-3-yl)phenyl)methanol and 4-nitrophenyl 4-(6-phenyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazin-3-yl)benzyl carbonate were prepared following known procedures.32, 35, 36 Sylgard® 184 poly(dimethyl siloxane) (PDMS) was purchased from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA) and 35-mm glass bottomed petri dishes were purchased from MatTek (Ashland, MA).

2.2. Instrumentation.

A Bruker AV600 Instrument was used to record NMR spectra (1H: 600 MHz, 13C: 151 MHz). All spectra were referenced to non-deuterated solvent peaks as follows: CDCl3 (1H: 7.26 ppm, 13C: 77.16 ppm), D2O (1H: 4.79). Chemical shifts are reported in ppm as singlet (s), doublet (d), triplet (t), quartet (q), pentet (pent), sextet (sext), heptet (hept), multiplet (m), ‘broad’ (br) and ‘apparent’ (app). Analytical HPLC was performed on all purified bisTz macromers to confirm the presence of a single peak. Samples were run at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min and temperature of 25 °C and monitored at 300 nm and 214 nm using an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC instrument equipped with a Halo C18 column (2.7 um, 3.0x75mm). A gradient of 5 to 40% acetonitrile in water over 25 min was used for all bisTz samples.

2.3. Synthesis of Hydrogel Precursors.

2.3.1. Synthesis of 3-(4-benzaldehyde)-6-phenyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazine (Tz-CHO, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Synthesis of PEG-bisTz2.

A dry round bottom flask was placed over an ice bath and sequentially charged with a solution of (4-(6-phenyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazin-3-yl)phenyl)methanol (Tz-OH, 100 mg, 0.38 mmol) in 10 mL anhydrous methylene chloride, followed by DMP (240 mg, 0.57 mmol) in 15 mL anhydrous methylene chloride. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C overnight, and the reaction progress was monitored by TLC. The crude mixture was concentrated onto silica and purified by column chromatography with a 0 to 5% methanol in methylene chloride gradient. The desired product Tz-CHO (70 mg, ~71%) was obtained as a magenta solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.17 (s, 1H), 8.86 (app d, 2H), 8.68 (app d, 2H), 8.18, (app d, 2H), 7.62-7.69 (br m, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 191.74 (CH), 164.32 (C), 163.53 (C), 138.66 (C), 137.18 (C), 133.65 (CH), 130.51 (C, CH), 129.22 (CH), 128.63 (CH), 128.44 (CH).

2.3.2. Synthesis of PEG-bisTz2 (Figure 1).

To a flame dried round bottom flask was added PEG-bisNHS (300 mg, ~0.038 mmol) in 20 mL anhydrous methylene chloride. Hydrazine hydrate (15 μL, ~0.3 mmol) was added via syringe, and the reaction was allowed to proceed under stirring for 3 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was diluted with 50 m1 methylene chloride, and the crude product isolated by exhaustive (~8) aqueous washes, followed by drying with sodium sulfate, filtering, and concentrating under reduced pressure. The presence of hydrazide primary amines, and successful removal of the NHS end groups were confirmed by ninhydrin TLC staining and 1H NMR, respectively. The crude bis hydrazide product was carried to the next step without further purification. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.15 (s, 4H), 3.77-3.51 (app m, ~682H (PEG backbone repeats))

PEG-bishydrazide (255 mg, 0.033mmol, ~87% crude yield) from the previous step was dissolved in 10 mL anhydrous methylene chloride and added to a flame dried round bottom flask. To this flask was added Tz-CHO (0.051 g, ~0.19 mmol) dissolved in 5 mL anhydrous methylene chloride, followed by PPTS (~2 mg). The mixture was stirred for 15 h at room temperature. The crude product was obtained via precipitation in diethyl ether, centrifugation at 5000 rpm, and sequential ether washing/centrifugation steps. The product was further purified by reverse phase HPLC on a Waters HPLC equipped with a Phenomenex C18 Column (100 Å, 5 μm, 250 × 21.2 mm) at 25 °C with UV monitoring of the tetrazine end groups at 300 nm using a gradient of 30 to 70% acetonitrile in water with 0.1% TFA. The collected fractions were lyophilized to obtain the dry product as a pink solid (PEG-bisTz2, yield: 209 mg, 67%).

1H NMR (600 MHz, CDC l3) δ 10.51 (s, 2H), 8.66 (app m, 8H), 8.40 (br s, 2H), 8.03 (app d,4H), 7.62 (app m, 6H), 4.21 (s, 4H), 3.77-3.51 (app m, ~682H (PEG backbone repeat)); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.70 (C),164.02 (C), 163.76 (C), 148.06 (CH), 138.13 (C) 133.32 (C), 132.91 (C), 131.83 (CH), 129.46 (CH), 128.64 (CH), 128.24 (CH), 127.17 (CH), 71.28-70.12 (CH2 PEG backbone repeats).

2.3.3. Synthesis of PEG-bisTz1, PEG-bisTz3 and trisTCO,.

PEG-bisTz1, PEG-bisTz3 and trisTCO were prepared following previously published methods.33, 34 Detailed procedures can be found in the supplementary information (Figure S1, S2, S10, S11).

2.4. Fabrication of Fibrous Scaffolds.

2.4.1. Interfacial bioorthogonal crosslinking.

Crosslinked hydrogel microfibers were synthesized from trisTCO and PEG-bisTz via interfacial tetrazine ligation. Briefly, the bisTz macromer (PEG-bisTz1, PEG-bisTz2 or PEG-bisTz3) was dissolved in DI water at a concentration of 0.125 mM. Separately, a stock solution of trisTCO in ethyl acetate was prepared at a concentration of 3 mM. To a 60-mm glass petri dish was added 3 mL of aqueous bisTz solution, and the dish was gently swirled to ensure a uniform spreading of the aqueous layer. To prepare cell-adhesive fibers, 1.5 mL of PEG-bisTz1 or PEG-bisTz2 was mixed with 1.5 mL of PEG-bisTz3 before adding to the dish. On top of the aqueous phase was layered 1.2 mL of ethyl acetate, followed by 0.8 mL of the trisTCO solution, for a final trisTCO concentration of 1.2 mM in the organic phase. Within 30 seconds, fibers were collected by drawing the crosslinked, swollen polymer film from the interface using tweezers and a collecting mandrel or frame as described previously, ensuring a consistent collection rate.34 Table 1 summarizes the compositions and properties of the three types of microfibers investigated.

Table 1.

Tunable synthesis of functional microfibers.

| Fiber I.D. |

Fiber property |

Macromer and crosslinker | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-bisTz1 (mM) |

PEG-bisTz2 (mM) |

PEG-bisTz3 (mM) |

trisTCO (mM) |

||

| MF1 | Non-degradable Non-adhesive | 0.125 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 |

| MF2 | Degradable Non-adhesive | 0 | 0.125 | 0 | 1.2 |

| MF3 | Non-degradable Cell-adhesive | 0.0625 | 0 | 0.0625 | 1.2 |

| MF4 | Degradable Cell-adhesive | 0 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 | 1.2 |

2.4.2. Preparation of fibrous scaffolds.

A fibrous mesh was collected on a square shaped 1″×1″ frame constructed from 22-gauge stainless steel wire. The direction of fiber collection was alternated during the fiber pulling process to create an interwoven mesh pattern. For each frame, 25 fibers were collected parallel to each other, after which the frame was rotated 90 degrees and 25 additional fibers were collected perpendicularly to the first 25 fibers. This process was repeated twice for a total of 100 fibers per mesh. Meshes were used in subsequent degradation and cell experiments.

Fibrous tubes were created by collecting fibers around a cylindrical shaped collector until the Tz and TCO monomers were exhausted. To form a cohesive tube, fibers were tightly wound around the collector so that fibers overlapped several times. A ~1-cm long tube (inner diameter ~1/2 cm) was constructed. For visualization purposes, fluorescently labeled meshes and tubes were made by doping Cy-5 methyl tetrazine at a 2 μM concentration in the aqueous phase during fiber pulling.

2.5. Characterization of Hydrogel Microfibers.

2.5.1. Fiber swelling.

Fibers collected from the petri dish were rinsed with ethanol and allowed to dry at room temperature for 1 h. Optical images were taken of the dry fibers with a Nikon MM-400/s microscope (with a Nikon Digital Sight DS-FI1 camera) using a 20× objective lens by affixing an individual fiber to the microscope stage and imaging coronally. Each fiber was then immersed in DI water for ~2 min, and images were acquired under the same microscope setting. Average diameters of dry and hydrated fibers were quantified digitally using ImageJ software. For every fiber imaged, 5 measurements were taken, and the results were averaged. A total of 34 microfibers were measured for each fiber composition. Circumferential swelling was calculated as the ratio of the average diameter of the hydrated fiber to the that of the corresponding dry fiber multiplied by 100. The circumferential volume fraction of the polymer in the swollen state (φp) was computed as the inverse of circumferential swelling.

2.5.2. Fiber degradation.

A total of twenty-five microfibers (MF1 and MF2, n = 4) were affixed to glass slides using silicone isolators and were either subjected to a 1-h treatment in 100 mM HCl (pH=1.0) or PBS (0.1 M, pH=7.4) at room temperature. Separately, microfibers (MF3 and MF4, n = 6) were secured on metal wires and were immersed in acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH=5) or fresh PBS (0.1 M, pH =7.4) at 37 °C for two weeks. Degradation was monitored by taking representative 10 × images of the fiber samples on an EVOS M7000 imaging system.

2.5.3. Thermal analysis.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed using a TA Instruments Discovery DSC equipped with an RCS90 cooling accessory (New Castle, DE). Baseline calibration was performed with sapphire disks while the temperature and cell constant were calibrated using an indium standard. Empty cell baseline variation was ~10 μW over ten cycles after calibration. Standard DSC experiments (2-5 mg sample per measurement) were then conducted with a heating and cooling rate of 10 °C/min and nitrogen cell purge flow rate of 50 mL/min. Plots shown are 2nd heat curves.

2.5.4. Mechanical properties.

Single fiber tensile tests were conducted using a custom micro-force tester.34, 37 Microfibers were draped over a hook fixed on the end of a soft calibrated beam and the two free ends of the fibers were taped together on an X-Y manual positioning stage directly below the hook. The microfibers were aligned in the vertical loading axis (Z-axis) and preloaded to ensure full fiber engagement. The vertical reference length was measured for each microfiber. During testing, microfibers were stretched along the Z-axis by driving the cantilevered beam via a piezoelectric stage. Using capacitive sensors, microfiber displacement (0-150 ± 0.01 μm) was calculated by taking the difference between the distance of piezoelectric stage traveled and the cantilever beam deflection. The tensile force was calculated by multiplying the beam deflection by the beam spring constant. To determine the force on a single fiber, this value was halved (looped fiber). Microfibers were pre-conditioned by a single ramp from 0 to 1.5% strain and then underwent four consecutive ramps ranging from 1 to 12% strain with a crosshead speed of 350 μm/s for both stretching and retracting. Immediately after the dry testing, each fiber was fully immersed in DI water on the stage. The hydrated fibers were tested using the same strains and crosshead speed used in dry testing. Force-displacement curves were plotted and fitted to a linear regression curve. Fiber stiffnesses were calculated from the average slope of force displacement regressions over four stretching and retracting cycles. Using the diameter values from the optical images, the cross-sectional area was computed for each fiber under both dry and hydrated conditions. Tensile stress values were calculated by dividing the force values by the corresponding cross-sectional area. Strain values were computed by dividing the change in fiber displacement during testing by the original reference length. Stress-strain curves were plotted and fit to a linear regression to obtain Young’s modulus (E) values for each testing condition. A total of 20 individual MF1 and MF2 samples were characterized in this study.

2.6. Cell Culture Studies.

2.6.1. Sample preparation.

Sylgard® 184 PDMS was coated on the surface of a 35-mm glass bottomed petri dish and allowed to cure at room temperature for 24 h to create a non-adhesive cell culture surface. Fibrous meshes were constructed around stainless steel frames as described above and placed in in PDMS-coated petri dishes. Sterilization was performed by gently agitating meshes in 70% ethanol for 1 h, with 3 solution changes. Fibrous scaffolds were next washed with sterilized DI water, followed by equilibration in serum-free cell culture media for 3 h prior to the start of cell culture.

2.6.2. Culture of porcine vocal fold fibroblasts (VFFs).

Porcine vocal fold fibroblasts (VFFs) were isolated as previously reported.19 VFFs were further expanded in a T-75 cell culture flask in DMEM media supplemented with 10% Fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin for 4 days, followed by a two-day culture with the addition of 10 ng/mL of TGF-β1. Cells were plated on the sterilized scaffold at a seeding density of 200,000 cells/mL and the cultures were maintained in the growth media for up to 7 days.

2.6.3. Viability and proliferation.

After 1, 4, and 7 days of culture, cells were stained with Calcein AM and ethidium homodimer solution at volume ratios of 1:1000 and 1:2000, respectively. After 15 min incubation at 37 °C, the dye solution was aspirated, and samples were washed with PBS and imaged using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope. Three biological repeats, each with two scaffold repeats for both fiber types were taken (i.e. n = 6) at each timepoint. Five representative 10× images were taken per scaffold for analysis, for a total of 30 images per time point for each fiber type.

To quantify viability and growth, 8-bit confocal images were first split by channel to isolate Calcein AM or ethidium homodimer-stained cells in ImageJ. The contrast was adjusted and live or dead cells were identified by applying a threshold to convert the colored images to black and white, followed by a watershed transformation to segment individual cells. Finally, cells were totaled using the particle analysis tool. The viability at day 1, 4, or 7 was computed by dividing the average number of live cells from Calcein AM channel images by the total number of cells and multiplying by 100. The fold change in number of cells was computed by dividing the average number of live cells on scaffolds at day 1, 4, or 7, by average number of live cells on scaffolds at day 1. In total, 30 images were analyzed for each timepoint for both measurements. Comparative statistics in the form of two- tailed unpaired t-tests were performed to evaluate potential differences between day 4 and day 7 samples of the same fiber type, and separately for day 7 between samples of different fiber types (MF3 vs. MF4).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION:

3.1. Synthesis of PEG-bisTz Macromers.

Chemical structures for bisTz macromers, with Tz conjugated to PEG via a stable carbamate linkage, with or without a dangling RGDSP peptide, are shown in Figure 1. Diphenyl tetrazine was chosen for its aqueous stability and high reactivity towards TCO (second order rate constant, k2, 2.85×105 M−1s−1 at 25 °C in water).32 PEG-bisTz1 and PEG-bisTz3 were synthesized following previously published protocols at gram scale with high purity (Figure S1-S2).33 PEG with a Mn of 7.5 kDa was used to ensure rapid diffusion during interfacial polymerization and the development of mechanically robust fibers via the ordered packing of PEG chains in the crystalline domain.33

To render the microfibers hydrolytically degradable, a new macromer with Tz coupled to PEG via a labile hydrazone bond (PEG-bisTz2) was synthesized using PEG-bisNHS (Mn = 7.5 kDa) as a starting material. The NHS end group was first converted to hydrazide by reacting with excess hydrazine hydrate (Figure 1). After minimal aqueous workup, inspection of 1H NMR spectra confirmed the successful removal of the succinimidyl ester end groups, as evidenced by the disappearance of the methylene proton peak at ~2.84 ppm and an up-field shift in the alpha carbonyl protons from 2.51 ppm to 2.15 ppm (Figure S3, S5). Additionally, ninhydrin TLC staining of the crude product confirmed the emergence of hydrazide end groups that were absent in the starting material TLC. The crude intermediate was carried onto the next step without further purification.

Hydrazone bonds were generated from hydrazide end groups by reacting with aldehydes. Thus, aldehyde functionalized tetrazine [Tz-CHO, (3-(4-benzaldehyde)-6-phenyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazine)] was synthesized from a diphenyl tetrazine alcohol [Tz-OH, ((4-(6-phenyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazin-3-yl)phenyl)methanol)] by oxidation in the presence of DMP (Figure 1), followed by column chromatography. Emergence of aldehyde proton at 10.17 ppm and carbon peaks at 191.74 ppm, and disappearance of alpha alcohol protons at 4.86 ppm confirmed the successful chemical transformation (Figure S6-S8). Finally, excess Tz-CHO was reacted with PEG-bisHydrazide in the presence of PPTS as a catalyst to form the crude PEG-bisTz2. Precipitation in ether followed by reverse phase HPLC allowed for the isolation of the desired product. Analytical HPLC revealed a single product peak and 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra revealed the presence of hydrazone methine peaks at 10.51 ppm and 148.06 ppm respectively, confirming successful conjugation (Figure 2, Figure S9). Comparing PEG and hydrazone proton integrations to those of diphenyl tetrazine aromatic groups confirmed a high end-group functionality (>97%).

Figure 2.

Synthesis of PEG-bisTz2 was confirmed via 1H NMR (A) and analytical HPLC monitoring absorbance at 300 nm and 214 nm (B). Integrating PEG backbone peaks (i and j) relative to tetrazine phenyl peaks (a and e) confirmed tetrazine end group functionality of >97%.

3.2. Microfiber Synthesis and Scaffold Fabrication

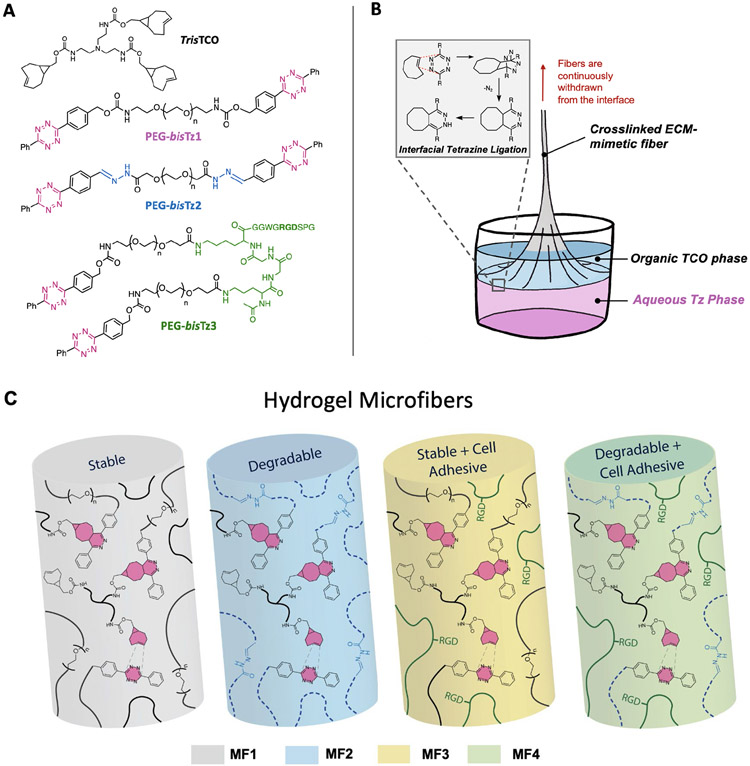

To enable fiber production via a diffusion controlled interfacial polymerization process, a hydrolytically stable, hydrophobic trisTCO crosslinker was synthesized (Figure 3A, Figure S10, S11). Layering an ethyl acetate solution of trisTCO on top of an aqueous bisTz solution immediately resulted in a solvent-swollen crosslinked film at the interface. Fibers were collected by withdrawing the film using a mandrel or fiber collection device as previously described.34 Of note, formation of a stable interface between the aqueous and organic phases by adding a small volume of ethyl acetate prior to addition of the trisTCO solution was found to afford more uniform fibers at early stages of interfacial polymerization. The rapid kinetics of tetrazine ligation allowed for a diffusion-limited reaction between TCO and Tz. As fibers were removed, new reactive partners immediately replenished the interface, allowing for continuous fiber collection (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Structures of PEG-based bisTz derivatives and the hydrophobic trisTCO molecule used to create crosslinked microfibers with desired properties are shown in (A). Interfacial tetrazine ligation occurs at the oil-water interface between TCO and Tz (B). Crosslinked polymer film can be continuously withdrawn to yield microfibers with biologically relevant properties (C).

Judicious selection of bisTz macromers in the aqueous phase provided a facile means of controlling fiber composition and properties (Table 1, Figure 3C). We have shown that PEG-bisTz1 serves as a stable macromer that, when reacted with trisTCO, yields crosslinked non-degradable fibers.34 Fibers that provide contact guidance for cell migration have also been produced from a bisTz macromer containing a dangling fibronectin-derived GRGDSP peptide (PEG-bisTz3). Development of fibers with engineered degradability was of interest to further approximate the native ECM, as well as afford hierarchical scaffolds that provisionally support cells until a new matrix is established. Herein, we introduce a new bisTz macromer (PEG-bisTz2) containing a labile hydrazone bond connecting the ethylene oxide repeats to the Tz group. Hydrolytically degradable hydrogel microfibers were continuously pulled from the oil-water interface using PEG-bisTz2 and trisTCO at a final concentration of 0.125 and 1.2 mM, respectively (Supplemental video 1). In agreement with classical interfacial polymerization,29, 38 it was not necessary to maintain a strict overall reaction stoichiometry. TrisTCO was used at a much higher concentration than the bisTz counterpart to compensate for wicking from the top oil phase during fiber pulling. It is also possible to form a stable polymer film and cohesive microfibers at a lower bisTz concentration (0.0625 mM, Supplemental video 1). Under this condition, bisTz would diffuse to the interface at a slower rate and the monomer would be exhausted earlier, potentially resulting in thinner and shorter microfibers, if the rate of fiber removal was maintained. In the subsequent experiments, bisTz concentration was fixed at 0.125 mM. Combination of bisTz3 with bisTz1 or bisTz2 in the aqueous phase afforded cell-adhesive microfibers that are stable or susceptible to hydrolysis, respectively (Figure 3C). Employing combinations of bisTz macromers confers an interfacial stoichiometry consistent with the ratios of individual components within the aqueous phase.

To demonstrate their utility as tissue engineering scaffolds, higher order structures were constructed by continuous fiber pulling, altering the collecting mandrel orientation and geometry. For example, a fibrous mesh was constructed by collecting fibers along a square shaped wire frame, repeatedly alternating the angle of collection by 90 degrees (Figure 4A). Fibrous tubes (~1 cm long, 0.5 cm wide) were created by collecting fibers around a cylindrical shaped fiber collector (Figure 4B/C). Individual fibers in the tube were held together cohesively, possibly through supramolecular interactions such as H-bonds and π─π stacking.39, 40 Taken together, the modular incorporation of macromers during interfacial polymerization, as well as the facile assembly of multifunctional fibers into hierarchical structures, demonstrate the tunability and versatility of this platform.

Figure 4.

Cy5-tetrazine was doped into the aqueous phase during fiber pulling to visualize the microfibers (MF2). Fibers can be constructed into biomimetic hierarchical structures including interwoven meshes by collecting fibers around wire frames (A) or fibrous tubes by coalescing fibers around a cylindrical collector (B, C).

3.3. Characterization of hydrogel microfibers.

Fiber swelling was examined under an optical microscope (Figure 5) and the average diameter of the fiber was measured first in the dry state, and then in the swollen state using ImageJ software. Employing a trifunctional TCO crosslinker in place of a difunctional TCO monomer during fiber pulling afforded fibers that did not craze or fracture in the swollen state under neutral conditions.33 The average diameter of the degradable fibers, MF2, in the dry state was found to be 10.8 ± 0.6 μm. Fibers reached an equilibrium swelling level upon ~1 min exposure to water. The average diameter of hydrated MF2 was found to be 28.9 ± 2.0 μm. Comparable results were collected from the non-degradable MF1, with average diameters of 9.9 ± 0.7 μm and 30.2 ± 2.5 μm, in the dry and hydrated state, respectively. MF2 circumferentially swelled to ~268% their original size (with polymer volume fraction φp = 37%), whereas MF1 swelled to ~312% their original size (φp =32%). MF1 and MF2 exhibited normal distributions in fiber diameter both in dry and hydrated states, as confirmed by Anderson-Darling, D’Agostino and Pearson, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests (Figure 5, Figure S12). There was no significant difference in fiber diameter distributions between MF1 and MF2 (Figure S13).

Figure 5.

Optical images (20×) of representative dry and hydrated MFs (A), and the corresponding diameter distributions (B, C). MF1 and MF2 fiber populations all followed gaussian distributions, and their respective curves are shown as dotted lines. Scale bar = 100 μm.

When dry fibers begin to absorb water, polar hydrophilic groups are first hydrated. Hydration of these groups leads to preliminary swelling and exposure of hydrophobic domains which can then interact with water. Further swelling, driven by osmotic pressure, occurs as “free” water infiltrates spaces between network chains, until opposing forces from the elastic network prohibit further swelling.41 Swelling differences in lightly crosslinked polymers are generally attributed to differential backbone solubility in the swelling solvent, described by the Flory-Huggins parameter, or differences in the average molecular weight between crosslinks, with shorter lengths leading to reduced swelling.42 The Tz macromers were designed to have comparable molecular weights, and the monomer feed was kept the same for MF1 and MF2. Thus, the consistency in fiber swelling suggests that replacing the carbamate bond in bisTz1 with the hydrazone linkage in bisTz2 did not affect the hydrophilicity of the resultant polymer network.

Differential scanning calorimetry was performed to analyze the thermal properties of the microfibers. The 2nd heat curves—after the removal of fabrication and processing history—are shown in Figure 6 for bisTz1 and 2 and MF1 and 2. Glass transition temperatures were not evident for the monomers or the fibers. The bisTz1 macromer exhibited an endothermic melting peak around 53.2 °C, in agreement with reported values for PEG of similar molecular weight.43 The melting temperature for MF1 was lower (50.8 °C). This is expected because installation of covalent crosslinking restricts the ordered packing of PEG chains, resulting in the formation of imperfect crystals with a lower Tm and a broader melting endotherm. PEG-bisTz2 and MF2 (Figure 6B) exhibited a Tm of 53.2 °C and 49.7 °C, respectively, comparable to those observed for the non-degradable counterparts. The enthalpy of melting for MF1 and MF2 were also comparable (56.83 J/g and 59.43 J/g, respectively). Collectively, the DSC results suggest that converting the carbamate linkage to a hydrazone bond did not compromise the crystalline packing of PEG chains or alter the physical properties of the monomer or the fiber.

Figure 6.

DSC thermograms for the PEG-bisTz1 and MF1 (A), and PEG-bisTz2 and MF2 (B) show sharp singular melting peaks. Curves represent the second heating cycle.

Mechanical properties of individual fibers were evaluated using a micro-force tester that can detect forces with a 4μN resolution.37 As shown in Figure 7, microfibers were folded over a hook at the midpoint and affixed to an X-Y stage at each end using laboratory tape. The hook was positioned at the end of a soft, calibrated cantilever beam with a spring constant of 28.4 ± 0.6 μN/μm. The looped fiber was aligned to the stretch (Z) axis, perpendicular to the stage, and its engagement was confirmed by preloading with a 150 ± 5 μN force. The cantilever beam was then driven vertically via a piezoelectric stage (0-250 μm) and fiber displacement was computed as the difference of stage travel and beam deflection, measured by a capacitance sensor. Multiplying the beam deflection by the beam spring constant and dividing by two (looped fiber setup) yielded the force. The initial length of the fiber—from the XY stage to the hook—was measured after preloading and before testing and found to be 9.5 ± 2.1 mm.

Figure 7.

Front and side illustrations of the fiber tensile testing device (A). Each fiber tested was wrapped around a hook attached to a soft-calibrated cantilevered beam. Tensile testing of fibers yielded force displacement curves of MF1 and MF2s shown here (B). Fiber diameter measurements were used to convert force displacement data into stress-strain curves, from which modulus values (C) could be ascertained. ns: non-significant, p > 0.05; **: significantly different, p = 0.0015, unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

Prior to testing, microfibers were pre-conditioned with a single strain ramp from 0-1.5% strain, followed by straining the fibers in four consecutive ramps ranging from 1-12% strain with constant crosshead speed during stretching and retracting. Fibers were tested in the dry state, followed by immersion in DI water and testing in the hydrated state, as depicted in Figure 7. Upon hydration, fibers similarly underwent four stretching and retracting cycles with the same strains and crosshead speed used in dry testing. Force-displacement curves were readily generated from the mechanical measurements, and representative curves for dry and hydrated fibers are shown in Figure 7. Consistency in mechanical behavior was confirmed across multiple stretching and retracting cycles (Figure S14), indicating that fibers could be elastically stretched under test conditions without undergoing permanent deformation. Hydrating MF1 and MF2 led to a 15-fold and 9-fold decrease in stiffness, respectively. To make more direct comparisons between fiber types, accounting for variations in fiber diameter and initial stretch lengths, stiffness measurements were converted to intrinsic mechanical quantities. Young’s Moduli values were determined from the slope of linear fits to stress-strain curves. For a given fiber, tensile stress was computed as the force divided by the cross-sectional fiber area. Strain was computed by dividing the change in fiber length during stretching by the reference length.

Water immersion significantly decreased the modulus for both fiber types (p<0.0001), with an average 47-fold decrease for MF1 and 19-fold decrease for MF2 and (Figure S15, S16). This is intuitive since water diffusion into the network increases the fiber diameter but is not expected to contribute to mechanical properties. Additionally, swelling leads to increased chain mobility due to the dissolution of PEG crystallites. Thus, fibers are both swollen (larger cross-sectional area) and less resistant to elastic deformation. While there was no significant difference between the two types of microfibers in the dry state (p=0.634), MF2 had significantly higher modulus values in the hydrated state, averaging over twice those of MF1 (p=0.0015, Figure S16, S17). Given that diameter distributions between fiber types were found to be similar before and after hydration, the heightened modulus values for MF2 cannot be explained fully by decreased water uptake (i.e. smaller cross-sectional area). The propensity for aromatic-aromatic interactions, while likely present in both types of microfibers due to diphenyl tetrazines, may be further reinforced in MF2 by extended conjugation through the hydrazone C═N bond outside the aromatic ring. These added contributions to mechanical properties may be undetectable in the dry state, due to overwhelming contributions from PEG crystallites, but become obvious when fibers are hydrated.

Hydrogel microfibers were engineered to be hydrolytically degradable by incorporating labile C═N linkages along the polymer backbone. The mechanism of imine hydrolysis, as described by Raines and others, entails protonation of nitrogen in the C═N─X bond as the first step.44-46 In the protonated state, the enhanced electrophilicity of carbon makes the linkage much more susceptible to hydrolytic cleavage. Compared to generic imines, hydrazone and oximes are much more stable due to the inductive effect of oxygen or nitrogen adjacent to the C─N double bond. Hydrazones exhibit comparably lower stability to oximes owing to reduced electronegativity of nitrogen and thus a more highly favored protonation state.44 Given their intermediate stability, hydrazone bonds have garnered broad appeal as reversible linkages in degradable tissue engineering constructs.47-50 Hydrazone hydrolysis can occur at neutral pH, and can be accelerated by acidic conditions that push the equilibrium toward the protonated state. Direct monitoring of PEG-bisTz2 hydrolysis by 1H NMR proved difficult owing to poor aqueous solubility of Tz-CHO degradation products. 1H NMR experiments involving a small “model” aliphatic hydrazone molecule (N′-cyclooctylideneacetohydrazide, CAHz, Figure S18) in D2O confirmed that hydrolysis occurs at neutral pD, on the order of weeks (t1/2 = 152.8 h, Figure S19-S22).

Having confirmed the susceptibility of the hydrazone bond to hydrolysis, we next examined microfiber degradation by optical imaging. Under an accelerated degradation condition (1-h exposure to 100 mM HCl), MF2 underwent substantial changes in surface morphology (Figure 8A, B). Fibers appear to thin non-uniformly as they degrade (arrows, Figure 8B), likely due to PEG semicrystalline chain packing that limits access to hydrazone bonds in non-amorphous regions. MF1 exposed to the same treatment appeared unchanged (Figure 8C, D) morphologically. Similarly, MF2 submerged in neutral PBS treatment for the same time period did not experience any apparent changes in morphology (Figure 8E, F).

Figure 8.

(A) Scheme showing microfiber degradation via hydrazone hydrolysis. (B-G) Optical images of MF1 (D, E) and MF2 (B, C, F, G) after 1-h incubation in HCl at pH = 1 (B-E) or pH = 7.4 (F, G).

Understanding the degradability of cell-adhesive microfibers was of particular interest since we sought to produce cell-adhesive fibers that could be broken down after serving a provisional function of supporting cells to lay a new ECM. Thus, we examined the extent of degradation for cell adhesive fibers, MF3 and 4, in acetate buffer (pH=5) and PBS (pH = 7.4). At pH 5, MF4 samples exhibited obvious macroscopic changes in morphology beginning at day 7, with significant degradation and loss of structural integrity after 14 days (Figure 9). On the other hand, MF3 control fibers exhibited no evidence of degradation over the course of the experiment at the acidic pH. MF4 appeared to loosen and break at specific points along their length rather than uniformly eroding inward from the surface, consistent with bulk erosion behavior.51 The delayed onset of perceptible degradation is likely attributed to added structural contributions from PEG-bisTz3 and three arm trisTCO. We have previously shown that a bis-functional TCO crosslinker is sufficient to generate water swollen fibers with similar surface morphology to those of trisTCO. Thus, MF4 undergoing hydrolysis may appear intact even after substantial bond breakage. Control MF3 exposed to the acidic conditions did not undergo degradation over the two-week time period (Figure 9). To confirm that the loss in fiber integrity in MF4 was due to degradation at a low pH, a negative control group of MF4 samples were exposed to PBS (0.1 M, pH=7.4) at 37 °C in parallel. These fibers did not undergo perceptible degradation over the course of the experiment; fiber integrity and morphology remained visually indistinguishable from MF3 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Fiber meshes were soaked in PBS (pH = 7.4) or acetate buffer (pH=5) for 2 weeks, and fiber integrity was monitored by optical microscope. Scale bar = 275μm.

3.4. Cell viability and growth.

Previously, we showed that microfibers without RGD (MF1) did not support cell attachment and growth.33 MF4 was designed to mimic native fibrous proteins of the ECM, providing both chemical and biological signals to cells in the form of labile backbone linkages and integrin-binding RGDSP motifs. Porcine focal fold fibroblasts were seeded on fibrous meshes—each containing 100 individual microfibers wrapped around a stainless steel frame—and maintained in the growth medium. Live/dead staining and confocal imaging showed >90% viability on days 1, 4, and 7, with viability above 96% for days 4 and 7. Cells seeded on MF4 fibers showed similar viability at all timepoints (Figure 10). Despite the low concentrations of PEG-bisTz3 required (0.0625 mM, 50% less than in our previously published work), the RGDGSP-containing microfibers (MF3 and MF4) strongly supported the attachment and spreading of VFFs. Cells on MF3 and MF4 took on an elongated morphology at day 4. By day 7, cells on MF4 scaffolds appear to grow beyond the confines of the original mesh, bridging adjacent fiber junctions (Figure 10, arrows).

Figure 10.

Live/Dead staining of cells on fibrous MF3 (A-C) and MF4 (D-F) scaffolds is shown for days 1, 4, and 7. Cells are spreading well and appear to align with fibers at day 7. 5× images show cell-encased fiber meshes at day 7 (G, H). Average fold change in cell number significantly increased for both MF3 and MF4 fibers at day 7 relative to their respective day 4 values (I, ***: p= 0.004, ****: p < 0.0001, unpaired, two-tailed t-test). Cells on both fiber varieties showed high viability for all timepoints tested (J, non-significant, p > 0.05, unpaired, two-tailed t-test).

The number of cells on MF4 meshes increased over 6-fold at day 4, and over 45-fold at day 7, indicating that the scaffolds promote the growth of cell populations. MF3 demonstrated similar fold changes; over 5-fold and over 35-fold for days 4 and 7, respectively (Figure 9). No significant difference was found in terms of fold change in cell numbers for MF4 compared to MF3 at day 7. Importantly, MF4 meshes appeared to remain intact over the course of the experiment, long enough for cells to fully envelop the 3D mesh. Extending the cell culture time to several weeks will likely reveal the benefits of fiber degradability on cell proliferation and matrix deposition.

Collectively, we have demonstrated that interfacial tetrazine ligation is a viable platform to create hybrid ECM-mimetic fibers that support cell adhesion and growth. Future advances in linker chemistry (to include MMP sensitivity, or growth factor sequestration and release, for example) are anticipated to afford further functional diversity to fibers, thus providing a better approximation of the native ECM for different tissues and disease states.

4. CONCLUSION:

We have demonstrated a novel method to produce crosslinked hydrogel microfibers using a rapid reaction between strained alkene and diphenyl tetrazine at the oil-water interface. Robust fibers with unique chemical, biological, and mechanical properties were produced on-demand by tuning the aqueous feed composition during fiber pulling. Introduction of a labile PEG-bisTz macromer enabled the production of novel crosslinked fibers with desirable mechanical and thermal properties, as well as degradation capacity. When combined with PEG-bisTz3, crosslinked ECM-mimetic microfibers that supported cell culture and degraded over time were produced. The tunability of the bioorthogonal platform enabled the combinations of bisTz1, bisTz2, and bisTz3 macromers in the fiber backbone. Higher order fiber assemblies, including tube and mesh structures, were constructed from multiple individual fibers. Meshes maintained their structural integrity over the cell culture period, supporting cell growth and viability. Overall, this platform presents a powerful method to generate compositionally diverse microfibers via modular incorporation of tetrazines and TCOs. Future developments in bisTz macromer functionalities (for example, enzymatic sensitivity, growth factor binding capability, or a non-PEG-based backbone) and TCO crosslinker functionalities (for instance, 4-, or 8-arm) are expected to provide further opportunities for scaffold customization, broadening the utility of this platform to serve new areas of tissue regeneration, remodeling, and repair.

Supplementary Material

(MOV2): Movie showing the production of MF1 at a PEG-bisTz1 concentration of 0.0625 mM.

(MOV1): Movie showing the production of MF2 at a PEG-bisTz2 concentration of 0.125 mM.

Table 2.

Summary of micromechanical testing results.

| Fiber Property | Fiber Condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF1 dry | MF2 dry | MF1 hydrated | MF2 hydrated | |

| E1 (MPa) | 99.0 ± 12.9 | 88.8 ± 16.7 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.6 |

Young’s modulus

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIDCD, R01DC014461; NIDCR R01DE029655), National Science Foundation (NSF, DMR 1809612), and Delaware Bioscience Center for Advanced Technology (DE-CAT 12A00448). OJG acknowledges the University of Delaware for the Doctoral Fellowship. Instrumentation and core facility support was made possible by NIH (S10 OD016361, P20 GM103446) and NSF (CHE-0840401, CHE-1229234, IIA-1301765) grants. The authors also acknowledge the use of facilities and instrumentation supported by NSF through the University of Delaware Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (DMR-2011824). Microscopy access was supported by grants from the NIH-NIGMS (P20 GM103446), the NSF (IIA-1301765), and the State of Delaware. We thank Xinyi Lyu for her assistance with the synthesis of trisTCO and Andrew Jemas for his help with fiber characterization.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION: Reaction schemes for PEG-bisTz1 and PEG-bisTz3, analytical HPLC data confirming purity of PEG-bisTz1 and -bisTz3 macromers; NMR spectra for PEG-bisNHS, PEG-bisHydrazide, Tz-OH, Tz-CHO and PEG-bisTz2; synthesis of trisTCO and 1H NMR spectrum of trisTCO; Quantile-quantile plots showing fiber diameter distribution alignment with normal distributions; estimation plots showing difference of mean fiber diameters in dry and hydrated states; representative stretching and retracting curves showing consistency in stiffness measurements during cyclic deformation; representative stress-strain curves from which modulus data was determined for dry and hydrated microfibers; comparison of the Young’s moduli for MF1 and MF2; and 1H NMR data showing degradation of a model hydrazone (“CAHz”) compound in D2O over one week.

References:

- 1.Lutolf MP; Hubbell JA, Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat. Biotechnol 2005, 23 (1), 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang N; Butler JP; Ingber DE, Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science 1993, 260 (5111), 1124–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daley WP; Peters SB; Larsen M, Extracellular matrix dynamics in development and regenerative medicine. J. Cell Sci 2008, 121 (Pt 3), 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleinman HK; Philp D; Hoffman MP, Role of the extracellular matrix in morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2003, 14 (5), 526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giancotti FG; Ruoslahti E, Integrin signaling. Science 1999, 285 (5430), 1028–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rozario T; DeSimone DW, The extracellular matrix in development and morphogenesis: a dynamic view. Dev. Biol 2010, 341 (1), 126–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ricard-Blum S., The collagen family. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2011, 3 (1), a004978–a004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Persikov AV; Ramshaw JA; Kirkpatrick A; Brodsky B, Electrostatic interactions involving lysine make major contributions to collagen triple-helix stability. Biochemistry 2005, 44 (5), 1414–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnans C; Chou J; Werb Z, Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2014, 15 (12), 786–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frantz C; Stewart KM; Weaver VM, The extracellular matrix at a glance. J. Cell Sci 2010, 123 (Pt 24), 4195–4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruoslahti E., RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 1996, 12, 697–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tibbitt MW; Anseth KS, Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2009, 103 (4), 655–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prince E; Kumacheva E, Design and applications of man-made biomimetic fibrillar hydrogels. Nat. Rev. Mater 2019, 4 (2), 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KY; Mooney DJ, Hydrogels for tissue engineering. Chem. Rev 2001, 101 (7), 1869–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicolas J; Magli S; Rabbachin L; Sampaolesi S; Nicotra F; Russo L, 3D Extracellular Matrix Mimics: Fundamental Concepts and Role of Materials Chemistry to Influence Stem Cell Fate. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21 (6), 1968–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang S; Liu X; Barreto-Ortiz SF; Yu Y; Ginn BP; DeSantis NA; Hutton DL; Grayson WL; Cui FZ; Korgel BA; Gerecht S; Mao HQ, Creating polymer hydrogel microfibres with internal alignment via electrical and mechanical stretching. Biomaterials 2014, 35 (10), 3243–3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui H; Webber MJ; Stupp SI, Self-assembly of peptide amphiphiles: from molecules to nanostructures to biomaterials. Biopolymers 2010, 94 (1), 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pham QP; Sharma U; Mikos AG, Electrospinning of polymeric nanofibers for tissue engineering applications: a review. Tissue Eng. 2006, 12 (5), 1197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravikrishnan A; Zhang H; Fox JM; Jia X, Core–Shell Microfibers via Bioorthogonal Layer-by-Layer Assembly. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9 (9), 1369–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews JA; Wnek GE; Simpson DG; Bowlin GL, Electrospinning of collagen nanofibers. Biomacromolecules 2002, 3 (2), 232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong S; Teo WE; Zhu X; Beuerman R; Ramakrishna S; Yung LY, Formation of collagen-glycosaminoglycan blended nanofibrous scaffolds and their biological properties. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6 (6), 2998–3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Z-M; Zhang YZ; Ramakrishna S; Lim CT, Electrospinning and mechanical characterization of gelatin nanofibers. Polymer 2004, 45 (15), 5361–5368. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wade RJ; Bassin EJ; Rodell CB; Burdick JA, Protease-degradable electrospun fibrous hydrogels. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 6639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessel B; Lee M; Bonato A; Tinguely Y; Tosoratti E; Zenobi-Wong M, 3D Bioprinting of Macroporous Materials Based on Entangled Hydrogel Microstrands. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 2020, 7 (18), 2001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogan H; Ilagan F; Tong X; Chu CR; Yang F, Microribbon-hydrogel composite scaffold accelerates cartilage regeneration in vivo with enhanced mechanical properties using mixed stem cells and chondrocytes. Biomaterials 2020, 228, 119579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davidson MD; Prendergast ME; Ban E; Xu KL; Mickel G; Mensah P; Dhand A; Janmey PA; Shenoy VB; Burdick JA, Programmable and contractile materials through cell encapsulation in fibrous hydrogel assemblies. Sci. Adv 2021, 7 (46), eabi8157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blackman ML; Royzen M; Fox JM, Tetrazine ligation: fast bioconjugation based on inverse-electron-demand Diels-Alder reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130 (41), 13518–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sletten EM; Bertozzi CR, Bioorthogonal chemistry: fishing for selectivity in a sea of functionality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2009, 48 (38), 6974–6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan PW; Kwolek SL, Interfacial polycondensation. II. Fundamentals of polymer formation at liquid interfaces. J. Polym. Sci 1959, 40 (137), 299–327. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittbecker EL; Morgan PW, Interfacial polycondensation. I. J. Polym. Sci 1959, 40 (137), 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alge DL; Azagarsamy MA; Donohue DF; Anseth KS, Synthetically Tractable Click Hydrogels for Three-Dimensional Cell Culture Formed Using Tetrazine–Norbornene Chemistry. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14 (4), 949–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang H; Dicker KT; Xu X; Jia X; Fox JM, Interfacial Bioorthogonal Cross-Linking. ACS Macro Lett. 2014, 3 (8), 727–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu S; Zhang H; Remy RA; Deng F; Mackay ME; Fox JM; Jia X, Meter-long multiblock copolymer microfibers via interfacial bioorthogonal polymerization. Adv. Mater 2015, 27 (17), 2783–2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S; Moore AC; Zerdoum AB; Zhang H; Scinto SL; Zhang H; Gong L; Burris DL; Rajasekaran AK; Fox JM; Jia X, Cellular interactions with hydrogel microfibers synthesized via interfacial tetrazine ligation. Biomaterials 2018, 180, 24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert WD; Fang Y; Mahapatra S; Huang Z; Am Ende CW; Fox JM, Installation of Minimal Tetrazines through Silver-Mediated Liebeskind-Srogl Coupling with Arylboronic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (43), 17068–17074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Royzen M; Yap GP; Fox JM, A photochemical synthesis of functionalized trans-cyclooctenes driven by metal complexation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130 (12), 3760–3761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonnevie ED; Baro V; Wang L; Burris DL, In-situ studies of cartilage microtribology: roles of speed and contact area. Tribol. Lett 2011, 41 (1), 83–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan PW; Kwolek SL, The nylon rope trick: Demonstration of condensation polymerization. J. Chem. Edu 1959, 36 (4), 182. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunter CA; Sanders JKM, The nature of pi-pi. interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1990, 112 (14), 5525–5534. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eom Y; Kim S-M; Lee M; Jeon H; Park J; Lee ES; Hwang SY; Park J; Oh DX, Mechano-responsive hydrogen-bonding array of thermoplastic polyurethane elastomer captures both strength and self-healing. Nat. Commun 2021, 12 (1), 621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffman AS, Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2002, 54 (1), 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flory PJ; Rehner J, Statistical Mechanics of Cross-Linked Polymer Networks I. Rubberlike Elasticity. J. Chem. Phys 1943, 11 (11), 512–520. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang G; Liu X; Tok AIY; Lipik V, Body temperature-responsive two-way and moisture-responsive one-way shape memory behaviors of poly(ethylene glycol)-based networks. Polym. Chem 2017, 8 (25), 3833–3840. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalia J; Raines RT, Hydrolytic stability of hydrazones and oximes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2008, 47 (39), 7523–7526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conant JB; Bartlett PD, A quantitative study of semicarbazone formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1932, 54 (7), 2881–2899. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ardagh E; Rutherford F, Studies of Some Hydrazone and Osazone Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1935, 57 (6), 1085–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boehnke N; Cam C; Bat E; Segura T; Maynard HD, Imine Hydrogels with Tunable Degradability for Tissue Engineering. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16 (7), 2101–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang B; Zhang Y; Zhang X; Tao L; Li S; Wei Y, Facilely prepared inexpensive and biocompatible self-healing hydrogel: a new injectable cell therapy carrier. Polym. Chem 2012, 3 (12), 3235–3238. [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKinnon DD; Domaille DW; Cha JN; Anseth KS, Bis-Aliphatic Hydrazone-Linked Hydrogels Form Most Rapidly at Physiological pH: Identifying the Origin of Hydrogel Properties with Small Molecule Kinetic Studies. Chem. Mater 2014, 26 (7), 2382–2387. [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKinnon DD; Domaille DW; Cha JN; Anseth KS, Biophysically defined and cytocompatible covalently adaptable networks as viscoelastic 3D cell culture systems. Adv. Mater 2014, 26 (6), 865–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ulery BD; Nair LS; Laurencin CT, Biomedical Applications of Biodegradable Polymers. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys 2011, 49 (12), 832–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(MOV2): Movie showing the production of MF1 at a PEG-bisTz1 concentration of 0.0625 mM.

(MOV1): Movie showing the production of MF2 at a PEG-bisTz2 concentration of 0.125 mM.