Abstract

The current standard of care for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) are the C5 inhibitors eculizumab and ravulizumab, both monoclonal antibodies designed to target the complement protein C5, thereby preventing its cleavage and the formation of the terminal attack complex. C5 inhibitors have yielded substantial improvements in the treatment of PNH and changed the mortality and morbidity, as well as health-related quality of life of patients with the disease. These treatments target underlying intravascular hemolysis; however, they do not address extravascular hemolysis, resulting in incomplete response and remaining symptoms in some patients. Therefore, despite treatment with a C5 inhibitor, some patients still experience anemia with associated fatigue, transfusion needs, and impaired health-related quality of life.

Current Treatments

OVERVIEW

Currently, the only cure for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.1 Stem cell transplantation is associated with high mortality: in a retrospective study of 26 patients with PNH who received hematopoietic stem cell transplants between 1988 and 2006, the transplant-related mortality rate was 42% at 12 months.2 Because of the considerable challenges and risks involved, a bone marrow transplant is not a therapeutic option for most patients and is typically recommended for patients with severe bone marrow failure and recurring life-threatening thromboembolic events.3,4

Other treatment strategies include complement mediators and supportive therapies. To date, the only therapies for PNH approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are the complement-inhibitory drugs eculizumab (approved in 2007) and ravulizumab (approved in 2018), both monoclonal antibodies designed to target the complement protein C5, thereby preventing its cleavage and the formation of the terminal attack complex.4-9 The C5 inhibitors have changed the mortality and morbidity of PNH since their introduction.6,10,11

Additional treatment strategies are focused on managing the symptoms and complications of PNH. Depending on the anemia symptoms they experience, patients with PNH may receive supportive treatments, such as blood transfusion, iron replacement therapy, growth factors, and erythropoeitin.3,4,12 Transfusions temporarily improve anemia and elevate hemoglobin levels, as the transfused cells express CD59 and CD55 on their cell surface and are resistant to complement-initiated lysis.4 Introduction of the immunotherapeutic drugs eculizumab and ravulizumab have significantly reduced the frequency of transfusions compared with no treatment.4 Steroids may also be used only for short-term use in symptomatic extravascular hemolysis.3,13

Treatment with anticoagulants, including heparin and coumarin derivatives, may reduce the risk of thrombosis.13 In the event of acute thrombosis, anticoagulant therapy with heparin is used.13 Even with preventive anticoagulant therapy, thrombohemolytic risk remains high.14 However, eculizumab therapy has markedly reduced the rate of thrombotic events11,15; for instance, in a 10-year UK cohort study of 153 patients treated with eculizumab, 3 thrombotic events were observed in 22 patients after 1 year of eculizumab therapy, compared with 36 thrombotic events in 22 patients in the 1 year before initiation of eculizumab.15

Finally, supplementation with folate, iron, and vitamin B12 can be used to support increased erythropoiesis in the bone marrow.3 Folate deficiency can accompany hemolysis as the body tries to compensate for the loss of blood by producing more blood cells, a process that uses folic acid and vitamin B12.

TENTATIVE CLASSIFICATION TO DETERMINE TREATMENT STRATEGY

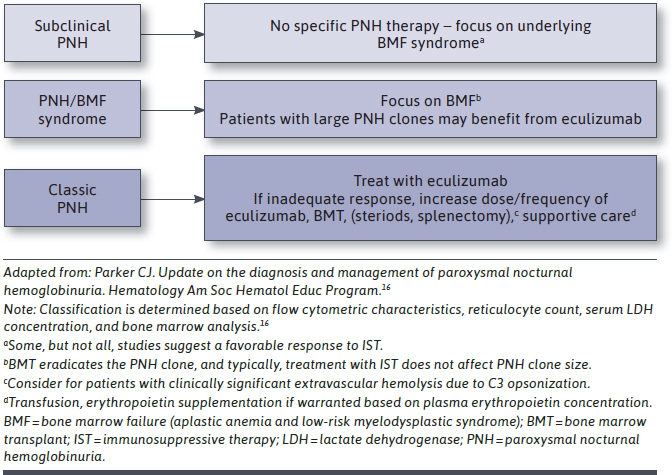

A tentative classification system for PNH was outlined by the International PNH Interest Group in 2016, with management based on 1 expert’s opinion.16 According to this classification system, an initial clinical workup is necessary to classify PNH disease activity, and treatment depends on this classification (Figure 1).16 According to this classification system, which preceded the approval of ravulizumab in 2018, eculizumab may be used to treat classic PNH and PNH in the setting of another bone marrow failure syndrome (aplastic anemia or low-risk myelodysplastic syndrome) if patients have large clones.

FIGURE 1.

Management of PNH Based on Disease Classification

C5 INHIBITORS

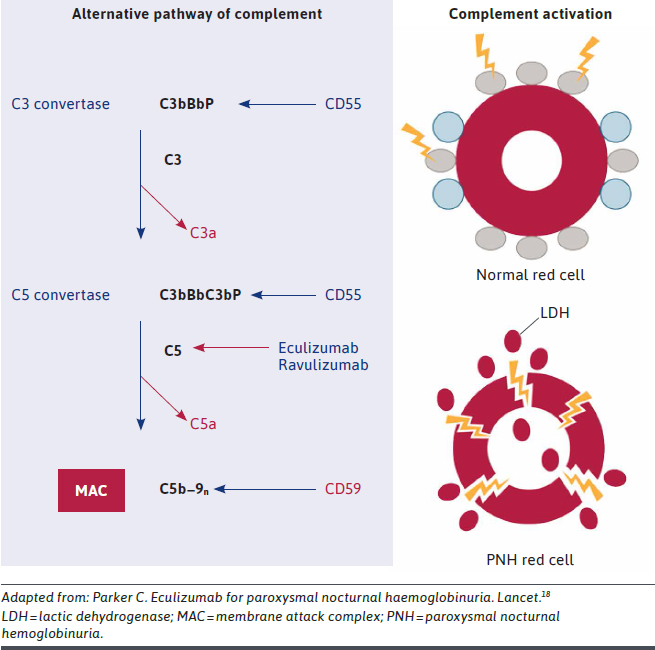

C5 inhibitors, the current standard of care, target underlying intravascular hemolysis.17 C5 inhibitors are humanized monoclonal antibodies to complement component 5.18 They inhibit the formation of membrane attack complex (Figure 2) and prevent pore formation and, hence, cell lysis, but they may not be effective in patients with C5 polymorphism.19

FIGURE 2.

Mechanism of Action of C5 Inhibitors

Eculizumab.

The C5 inhibitor eculizumab was initially approved by the FDA in 2007 for the reduction of hemolysis in PNH patients. Eculizumab has a terminal half-life of approximately 11 days and is administered by intravenous infusion over 35 minutes.20 The dosing regimen involves 600 mg weekly for 4 doses, followed by a maintenance dose of 900 mg every 2 weeks starting at week 5.

Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody specifically designed to target the complement protein C5, thereby preventing its cleavage and the formation of the terminal attack complex.4,7 This averts the complement-mediated lysis of blood cells and hemolysis. Patients on eculizumab have, therefore, improved anemia and hemoglobin levels, thus, requiring less frequent blood transfusions. Patients with PNH with kidney disease have also shown sustainable improvements in renal functions, likely due to reduced hemosiderin deposits in the kidney as a result of reduced intravascular hemolysis, normalized nitric oxide levels, and vascular tone.21 The decreased intravascular hemolysis has been associated with reduced fatigue and improved overall quality-of-life measurements.4

Clinical trial evidence has demonstrated eculizumab to be effective, safe, and well tolerated for patients with PNH.20 Both phase 3 trials of eculizumab (TRIUMPH [N = 87] and SHEPHERD [N = 97]) met their primary and secondary endpoints, including stabilization of hemoglobin, units of red blood cells (RBCs) transfused, reduction of hemolysis, transfusion independence, improvements in fatigue, and lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) changes.9,22 Eculizumab carries a boxed warning for meningococcal infection.20 Given that warning, patients on eculizumab may be susceptible to meningococcal infections and should, therefore, be vaccinated 2 weeks before beginning therapy.7

Eculizumab has yielded substantial improvements in the treatment of PNH and changed the mortality and morbidity of the disease since its introduction.6,10 In postmarket surveillance studies of eculizumab use at 1 year, health-related quality of life (HRQOL) improvements were closely associated with laboratory data, in particular LDH and hemoglobin levels, both markers of the degree of hemolysis.23 Eculizumab has also been shown to reduce the risk of thrombosis.

Ravulizumab.

An eculizumab-like monoclonal antibody approved by the FDA in 2018, ravulizumab differs from eculizumab by the substitution of 4 amino acids, which alters the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the molecule.24 Ravulizumab provides the same benefits as eculizumab with similar safety and tolerability. Compared with eculizumab, ravulizumab has a 4-time longer half-life and is administered via intravenous infusion every 8 weeks. Due to its weight-based dosing regimen, infusion time for ravulizumab may vary based on patient weight.24 Both phase 3 trials of ravulizumab (Study 301 [N = 246] and Study 302 [N = 197]) met their primary and secondary endpoints, including transfusion avoidance, LDH change/normalization, improvement in fatigue, presence of breakthrough hemolysis, stabilized hemoglobin, and presence of serum-free C5.25,26 A new formulation of ravulizumab (100 mg/mL vs. 10 mg/mL), which may decrease infusion time, was approved by the FDA in 2020.24

In addition, a phase 3 study compared ravulizumab (n = 125) versus eculizumab (n = 121) in adult patients with PNH naive to complement inhibitors.25 In this study, ravulizumab met the objective of noninferiority compared with eculizumab on both coprimary endpoints, and point estimates for both coprimary endpoints favored ravulizumab. Additionally, ravulizumab was noninferior to eculizumab on the 4 key secondary endpoints (change in LDH, change in fatigue, the proportion of patients with breakthrough hemolysis, and the proportion of patients with stabilized hemoglobin), and hierarchal superiority testing was performed for breakthrough hemolysis.

Another phase 3 study evaluated patients who were clinically stable on eculizumab treatment and were randomized 1:1 to 26 weeks of open-label treatment with intravenous ravulizumab (n = 97) or eculizumab (n = 98).27 Ravulizumab achieved noninferiority compared with eculizumab for the primary endpoint of percentage change in LDH, with the point estimate for treatment difference favoring ravulizumab. Treatment with ravulizumab also achieved noninferiority compared with eculizumab for all 4 key secondary endpoints (proportion of patients with breakthrough hemolysis, HRQOL, transfusion avoidance, and the proportion of patients with stabilized hemoglobin).

ECONOMIC BURDEN ASSOCIATED WITH CURRENT TREATMENT

Patients undergoing treatment with C5 inhibitors may experience economic burden associated with treatment. Dose adjustments, hospitalizations, and blood transfusions for a breakthrough hemolysis episode may have annual costs per patient of $51,716 for events due to complement-amplifying conditions, $152,895 for events due to insufficient C5 inhibition, and $186,107 for events due to pregnancy.28 In addition, patients with PNH and their caregivers face substantial productivity costs resulting from the time commitments for administration of C5 inhibitors at infusion clinics. In an analysis of the productivity effect of C5 inhibitor treatment, among 100 patients with PNH in the United States over a 2-year period, lost productivity (including administration, recovery, and travel times, multiplied by an hourly wage of U.S. $20) associated with treatment with any C5 inhibitor has been estimated to cost between $1,535,099 and $4,306,790.29

Intravenous infusions require administration at a hospital, outpatient infusion center, or in the home via a home infusion nurse, resulting in extra costs for the health plan. In-clinic infusions also pose an additional risk of infection—for example, from SARS-CoV-2—for patients who are already immunocompromised.30

Unmet Needs

Patients with PNH experience a wide range of symptoms that can adversely affect mortality and cause debilitating fatigue, which is often associated with decreased activities of daily living.5,31 Despite clinical improvements seen with C5 inhibitors, they may not address all the factors that can lead to ongoing hemolysis, anemia, transfusions, and severe fatigue and that may affect bone marrow function.17,32-34 C5 inhibitors such as eculizumab reduce intravascular but not C3-mediated extravascular hemolysis, leaving significant unmet need. Both eculizumab and ravulizumab carry a boxed warning for meningococcal infections.20,24 There is also a risk of breakthrough hemolysis due to insufficient complement inhibition.6,25 Few patients undergoing treatment with C5 inhibitors experience hemoglobin normalization.34 Finally, C5 inhibitors may not be effective in patients with C5 polymorphism.19

INCOMPLETE RESPONSE

C5 inhibitors are highly effective in affecting the intravascular hemolysis in PNH hemolysis but do not target C3-mediated extravascular hemolysis, resulting in incomplete response, as demonstrated in real-world evidence.10,35 In a retrospective study evaluating 93 patients with PNH on eculizumab at 6 international reference PNH centers, after 12 months of treatment 10% of patients treated with a C5 inhibitor had a complete response (defined as not requiring transfusion, normal hemoglobin, and LDH levels less than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal [ULN] and absolute reticulocyte count ≤ 150,000/μL); the remaining patients had responses ranging from major response to no response (Table 1).35 Another retrospective, single-center real-world study of a small cohort of patients treated with eculizumab (N = 30) revealed that only a small percentage of patients showed a complete response to the drug (defined as not requiring transfusion, normal hemoglobin level, no symptoms, and LDH levels < 1.5 times the ULN). Four patients (13.3%) were deemed complete responders; 16 (53.3%) were good partial responders (fewer transfusions than before the treatment, LDH < 1.5 ULN without thrombosis); and 10 (33.3%) were classified as suboptimal responders (unchanged transfusion needs and persistent PNH symptoms).10

TABLE 1.

Hematologic Response with Eculizumab Treatment

| Type of Response | Time Point, Percentage of Patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Months | 12 Months | Last 6 Months | |

| Complete response | |||

| No transfusion requirement with normal stable hemoglobin level and no evidence of hemolysis | 8.75 | 10.12 | 10.84 |

| Major response | |||

| No transfusion requirement with normal hemoglobin but evidence of residual intravascular or extravascular hemolysis | 3.75 | 6.32 | 6.02 |

| Good response | |||

| No transfusion requirement with persistent chronic mild anemia | 33.75 | 46.83 | 40.96 |

| Partial response | |||

| Persistent chronic moderate anemia and/or occasional red blood cell transfusion | 33.75 | 27.84 | 28.91 |

| Minor response | |||

| 3-6 red blood cell transfusions every 6 months | 13.75 | 6.32 | 7.22 |

| No response | |||

| > 6 blood cell transfusions every 6 months | 6.25 | 2.53 | 6.02 |

Source: Debureaux PE, Cacace F, Silva BGP, et al. Hematological response to eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: application of a novel classification to identify unmet clinical needs and future clinical goals [abstract]. Blood.35

Some patients treated with C5 inhibitors may also experience breakthrough hemolysis, defined as at least one of the following new or worsening symptoms or signs of intravascular hemolysis due to insufficient complement inhibition: fatigue, hemoglobinuria, abdominal pain, dyspnea, anemia, or a major adverse vascular event.25 A retrospective analysis using medical records of 763 dosings of 14 patients with PNH identified 12 events of breakthrough hemolysis in 4 patients, illustrating that a subset of patients treated with C5 inhibitors may experience breakthrough hemolysis in the final 24 to 48 hours before their next infusion.36

Finally, ongoing treatment with C5 inhibition may result in worsening of C3-mediated extravascular hemolysis, a novel mechanism of RBC destruction for patients with PNH undergoing C5 inhibitor treatment.33,34 A retrospective analysis of an investigative study of 56 Italian patients with PNH (N = 56) found that all 41 patients treated with eculizumab had a substantial percentage of RBCs with C3 bound on the surface.34 The percentage of C3-positive RBCs correlated with hematologic response: optimal responders had the lowest levels of C3-coated RBCs. Targeting the complement cascade upstream at C3 may provide benefit in reducing ongoing hemolysis.33

CONTINUED ANEMIA

Patients may continue to experience anemia despite treatment with C5 inhibitors. In the previously mentioned retrospective analysis of 56 Italian patients with PNH, no more than one third of patients on C5 inhibitor therapies achieved hemoglobin normalization (≥ 12 g/dL).33,34 As a result of incomplete control of hemolysis, the bone marrow continues to overproduce reticulocytes (immature RBCs).17 An additional retrospective real-world study conducted in the Leeds center of the UK PNH National Service of patients treated with eculizumab for ≥ 13 months (N = 141) revealed that 72% of patients were anemic (hemoglobin < 120 g/L).37 In this same analysis, 21% (n = 30) of patients received a higherthan-label dose of 1,200 mg or more eculizumab every 2 weeks due to either subtherapeutic eculizumab levels and/or measurable terminal complement levels indicating insufficient complement inhibition.37

In a phase 3 study comparing ravulizumab (n = 125) versus eculizumab (n = 121) in adult patients with PNH naive to complement inhibitors, after 6 months of therapy, 32%-36% of patients treated with a C5 inhibitor did not reach hemoglobin stabilization (defined as avoidance of a ≥ 2 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin level from baseline in the absence of transfusion).25

In a second phase 3 study, patients who were clinically stable on eculizumab treatment were randomized to 26 weeks of open-label treatment with intravenous ravulizumab (n = 97) or eculizumab (n = 98), after which eculizumab-treated patients were switched to open-label ravulizumab for the extension period of up to 2 years.27 In this study, 23.7% of patients receiving ravulizumab and 24.5% of patients receiving eculizumab did not achieve stabilized hemoglobin levels. Ravulizumab achieved noninferiority compared with eculizumab for the primary endpoint of percentage change in LDH, with the point estimate for treatment difference favoring ravulizumab. Treatment with ravulizumab also achieved noninferiority compared with eculizumab for all 4 key secondary endpoints (proportion of patients with breakthrough hemolysis, HRQOL, transfusion avoidance, and the proportion of patients with stabilized hemoglobin).

TRANSFUSION DEPENDENCE

Despite treatment with C5 inhibitors, some patients remain transfusion dependent. In a retrospective real-world study of 141 patients with PNH on eculizumab (> 13 months of treatment), during the last 12 months of treatment, 36% of patients received at least 1 transfusion, with 16% requiring 3 or more transfusions.37

In the phase 3 study comparing ravulizumab and eculizumab in complement-inhibitor–naive patients, the transfusion avoidance rate was 73.6% with ravulizumab and 66.1% with eculizumab, suggesting that a proportion of patients remained transfusion dependent.25 Similarly, in the phase 3 study of ravulizumab versus eculizumab in eculizumab-experienced patients, the transfusion avoidance rate was 87.6% in patients who switched to ravulizumab and 82.7% in patients who continued to receive treatment with eculizumab.26 The transfusion avoidance rate in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 26 week study of eculizumab versus placebo was 51% (vs. 0% with placebo).9

ADDITIONAL UNMET NEEDS

Patients undergoing treatment with C5 inhibitors may continue to experience fatigue and impaired HRQOL. As part of postmarketing surveillance, 491 patients with PNH who were treated with eculizumab after approval were registered in a postmarketing surveillance data registry as of March 2017.23 Patients treated with eculizumab for 1 year experienced continued impairment in overall HRQOL and continued fatigue relative to reference scores for the general adult population, as indicated by scores on the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30; 1-year eculizumab score of 60.8 vs. 75.5 for the general European population) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue subscale (FACIT-Fatigue; 1-year eculizumab score of 39.9 vs. 43.6 for the general European population).23,38

Patients undergoing treatment with C5 inhibitors experience considerable burden associated with the need for infusion. The half-life of ~11 days for eculizumab necessitates indefinite intravenous dosing every 2 weeks, which is burdensome to patients6; the infusion regimen for ravulizumab of every 8 weeks may provide a markedly reduced burden of treatment.27 Evidence suggests that patients prefer subcutaneous versus intravenous drug administration owing to home administration, saving of travel time, avoiding problems with venous access, and reduced discomfort with subcutaneous administration.39

Finally, although eculizumab is effective in the majority of patients with PNH, a small cohort (~3.2%) have been found to have a single missense mutation on C5 that blocks eculizumab binding and results in a poor therapeutic response.19

Conclusions

C5 inhibition has improved clinical outcomes for patients with PNH and has reduced morbidity and mortality. While C5 inhibitors—the current standard of care—target underlying intravascular hemolysis, they do not address residual anemia resulting from incomplete control of intravascular hemolysis in some patients. Breakthrough hemolysis and ongoing extravascular hemolysis due to C3 deposition on RBCs are not addressed by C5 inhibitors. These unmet treatment needs result in incomplete control of the disease and associated symptoms. Patients may continue to experience ongoing hemolysis, persistent chronic anemia, the need for continued blood transfusions, fatigue, and impaired HRQOL despite treatment with a C5 inhibitor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Kate Lothman of RTI Health Solutions provided medical writing services, which were funded by Apellis Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brodsky RA. How I treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2009;113(26):6522-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santarone S, Bacigalupo A, Risitano AM, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: long-term results of a retrospective study on behalf of the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto Midollo Osseo (GITMO). Haematologica. 2010;95(6):983-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker C, Omine M, Richards S, et al. Diagnosis and management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2005;106(12):3699-709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young NS, Meyers G, Schrezenmeier H, Hillmen P, Hill A. The management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: recent advances in diagnosis and treatment and new hope for patients. Semin Hematol. 2009;46(1 Suppl 1):S1-S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill A, DeZern AE, Kinoshita T, Brodsky RA. Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stern RM, Connell NT. Ravulizumab: a novel C5 inhibitor for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Ther Adv Hematol. 2019;10:2040620719874728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKeage K. Eculizumab: a review of its use in paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Drugs. 2011;71(17):2327-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillmen P, Hall C, Marsh JC, et al. Effect of eculizumab on hemolysis and transfusion requirements in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(6):552-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillmen P, Young NS, Schubert J, et al. The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(12):1233-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeZern AE, Dorr D, Brodsky RA. Predictors of hemoglobin response to eculizumab therapy in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Eur J Haematol. 2013;90(1):16-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillmen P, Muus P, Duhrsen U, et al. Effect of the complement inhibitor eculizumab on thromboembolism in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2007;110(12):4123-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boschetti C, Fermo E, Bianchi P, Vercellati C, Barraco F, Zanella A. Clinical and molecular aspects of 23 patients affected by paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Am J Hematol. 2004;77(1):36-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devalet B, Mullier F, Chatelain B, Dogne JM, Chatelain C. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a review. Eur J Haematol. 2015;95(3):190-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrezenmeier H, Muus P, Socie G, et al. Baseline characteristics and disease burden in patients in the International PNH Registry. Haematologica. 2014;99(5):922-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill A, Kelly RJ, Hillmen P. Thrombosis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2013;121(25):4985-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker CJ. Update on the diagnosis and management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016(1):208-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brodsky RA. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2014;124(18):2804-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker C. Eculizumab for paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):759-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimura J, Yamamoto M, Hayashi S, et al. Genetic variants in C5 and poor response to eculizumab. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(7):632-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soliris (eculizumab) prescribing information. Alexion Pharmaceuticals. November 2020. Available at: https://alexion.com/Documents/Soliris_USPI.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villegas A, Nunez R, Gaya A, et al. Presence of acute and chronic renal failure in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: results of a retrospective analysis from the Spanish PNH Registry. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(10):1727-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brodsky RA, Young NS, Antonioli E, et al. Multicenter phase 3 study of the complement inhibitor eculizumab for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2008;111(4):1840-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueda Y, Obara N, Yonemura Y, et al. Effects of eculizumab treatment on quality of life in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in Japan. Int J Hematol. 2018;107(6):656-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ultomiris (ravulizumab) prescribing information. Alexion Pharmaceuticals. October 2020. Available at: https://alexion.com/Documents/Ultomiris_USPI.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JW, Sicre de FontbruneF, Wong LeeLee L, et al. Ravulizumab (ALXN1210) vs eculizumab in adult patients with PNH naive to complement inhibitors: the 301 study. Blood. 2019;133(6):530-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulasekararaj AG, Hill A, Rottinghaus ST, et al. Ravulizumab (ALXN1210) vs eculizumab in C5-inhibitor-experienced adult patients with PNH: the 302 study. Blood. 2019;133(6):540-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulasekararaj A, Risitano AM, Maciejewski JP, et al. A phase 2 open-label study of danicopan (ACH-0144471) in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) who have an inadequate response to eculizumab monotherapy. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1):3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomazos I, Sierra R, Cheung A, Brodsky R, Weitz I, Johnston K. PSY12 Cost burden of breakthrough hemolysis in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria on eculizumab treatment [abstract]. Value Health. 2019;22(Suppl 2):S376. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy AR, Dysart L, Patel Y, et al. Comparison of lost productivity due to eculizumab and ravulizumab treatments for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in France, Germany, Italy, Russia, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States [abstract]. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1): 4803. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-127443 [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. COVID-19 - bone marrow failure and PNH. 2020. Available at: https://www.ebmt.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/SAAWP_COVID_Recomendations.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 31.Weitz I, Meyers G, Lamy T, et al. Cross-sectional validation study of patient-reported outcomes in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Intern Med J. 2013;43(3):298-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brodsky RA, Peffault de Latour R, Rottinghaus ST, et al. Characterization of breakthrough hemolysis events observed in the phase 3 randomized studies of ravulizumab versus eculizumab in adults with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Haematologica. January 16, 2020. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.236877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Risitano AM, Marotta S, Ricci P, et al. Anti-complement treatment for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: time for proximal complement inhibition? A position paper from the SAAWP of the EBMT. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Risitano AM, Notaro R, Marando L, et al. Complement fraction 3 binding on erythrocytes as additional mechanism of disease in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria patients treated by eculizumab. Blood. 2009;113(17):4094-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Debureaux PE, Cacace F, Silva BGP, et al. Hematological response to eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: application of a novel classification to identify unmet clinical needs and future clinical goals [abstract]. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1):3517. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-125917 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakayama H, Usuki K, Echizen H, Ogawa R, Orii T. Eculizumab dosing intervals longer than 17 days may be associated with greater risk of breakthrough hemolysis in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Biol Pharm Bull. 2016;39(2):285-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKinley C, Richards S, Munir T, et al. Extravascular hemolysis due to C3-loading in patients with PNH treated with eculizumab: defining the clinical syndrome [abstract]. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):3471. doi: 10.1182/blood.V130.Suppl_1.3471.3471 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinz A, Singer S, Brahler E. European reference values for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30: results of a German investigation and a summarizing analysis of six European general population normative studies. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(7):958-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoner KL, Harder H, Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA. Intravenous versus subcutaneous drug administration. Which do patients prefer? A systematic review. Patient. July 12, 2014. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0075-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]