Abstract

Objective

To assess the quality and accuracy of the voice assistants (VAs), Amazon Alexa, Siri and Google Assistant, in answering consumer health questions about vaccine safety and use.

Methods

Responses of each VA to 54 questions related to vaccination were scored using a rubric designed to assess the accuracy of each answer provided through audio output and the quality of the source supporting each answer.

Results

Out of a total of 6 possible points, Siri averaged 5.16 points, Google Assistant averaged 5.10 points and Alexa averaged 0.98 points. Google Assistant and Siri understood voice queries accurately and provided users with links to authoritative sources about vaccination. Alexa understood fewer voice queries and did not draw answers from the same sources that were used by Google Assistant and Siri.

Conclusions

Those involved in patient education should be aware of the high variability of results between VAs. Developers and health technology experts should also push for greater usability and transparency about information partnerships as the health information delivery capabilities of these devices expand in the future.

Keywords: voice assistant, intelligent assistant, Google Assistant, Amazon Alexa, Amazon Echo, Siri, voice search, health literacy, vaccines

Summary.

What is already known?

Voice assistants (VAs) are increasingly used to search for online information.

VAs’ ability to deliver health information has been demonstrated to be inconsistent in Siri and Google Assistant.

What does this paper add?

This study evaluates vaccine health information delivered by the top three virtual assistants.

This paper highlights answer variability across devices and explores potential health information delivery models for these tools.

Introduction

Patients widely use the internet to find health information.1 A growing share of internet searches are conducted using voice search. In 2018, voice queries accounted for one-fifth of search queries, and industry leaders predict that figure will grow to 30%–50% by 2020.2–4 The growth in voice search is partially driven by the ubiquity of artificial intelligence-powered voice assistants (VAs) on mobile apps, such as Siri and Google Assistant, and on smart speakers, such as Google Home, Apple HomePod, Amazon Alexa and Amazon Echo.5 As VAs become available on more household devices, more people are turning to them for informational queries. In 2018, 72.9% of smart speaker owners reported using their devices to ask a question at least once a month.6 A number of health-related companion apps have been released for these VAs, suggesting developer confidence that VAs will be used in the health information context in the future.7 8

Many studies have evaluated the quality of health information websites and found varied results depending on the topic being researched.9–12 However, the literature evaluating how well VAs find and interpret online health information is limited. Miner et al found that VAs from Google, Apple and Samsung responded inconsistently when asked questions about mental health and interpersonal violence.13 Boyd and Wilson found that the quality of smoking cessation information provided by Siri and Google Assistant is poor.14 Similarly, Wilson et al found that Siri and Google Assistant answered sexual health questions with expert sources only 48% of the time.15

Recently, online misinformation about vaccines is of particular concern in light of outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases in the USA. Several studies have demonstrated that online networks are instrumental in spreading misinformation about vaccination safety.16–19 Because the internet hosts a large amount of inaccurate vaccination information, the topic of vaccines is ideal for testing how well VAs distinguish between evidence-based online information and non-evidence-based sites. At the time of writing, there are no studies evaluating how well VAs navigate the online vaccine information landscape. There are also no studies that have evaluated consumer health information provided by Amazon Alexa, which makes up a growing market share for voice search.

Study objective

This study aims to assess the quality and accuracy of Amazon Alexa, Siri and Google Assistant in answering consumer health questions about vaccine safety and use. For the purposes of this paper, ‘consumer health’ refers to health information aimed at patients and lay persons rather than healthcare practitioners and policymakers.

Materials and methods

Selection of VAs

Siri, Google Assistant and Alexa were chosen for analysis due to their rankings as the top three VAs by search volume and smart speaker market share.20 21

Selection of questions

The sample set of questions was selected from government agency frequently asked question (FAQ) pages and organic web search queries about vaccines. This dual-pronged approach to question harvesting was chosen to ensure the questions reflected both agency expertise and realistic use cases from online information seekers.

Question set 1 contained questions from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) immunisation FAQ page and the CDC infant immunisation FAQ page.22 23 Question set 2 was generated using AnswerThePublic.com, a free tool which aggregates autosuggest data from Google and Bing.24 Autosuggest data offers insight into the volume of questions millions of users search for in online search engines. Prior studies have used autosuggest data from Google Trends to identify vaccination topics of interests to online health information consumers.18 The authors chose to build upon this method by using AnswerThePublic.com, which incorporates data from both Google Trends and Bing users, to capture a broader sample of online search queries. The authors used the English language setting and searched for the term ‘vaccines’ to pull 186 frequently searched vaccine-related phrases. From these phrases, fully formed questions were included and partial phrases that did not form a full sentence were discarded. Partial phrase queries were removed because they do not reflect the longer conversational queries typically used to address VAs.3 25 Questions that were redundant with question set 1 were also removed. The final sample set of questions included 54 items.

Evidence-based answers were created for each question to serve as a comparison reference when assessing VA answer accuracy. A complete list of questions, approved answers and supporting sources is available in online supplementary table S1.

bmjhci-2019-100075supp001.pdf (360.5KB, pdf)

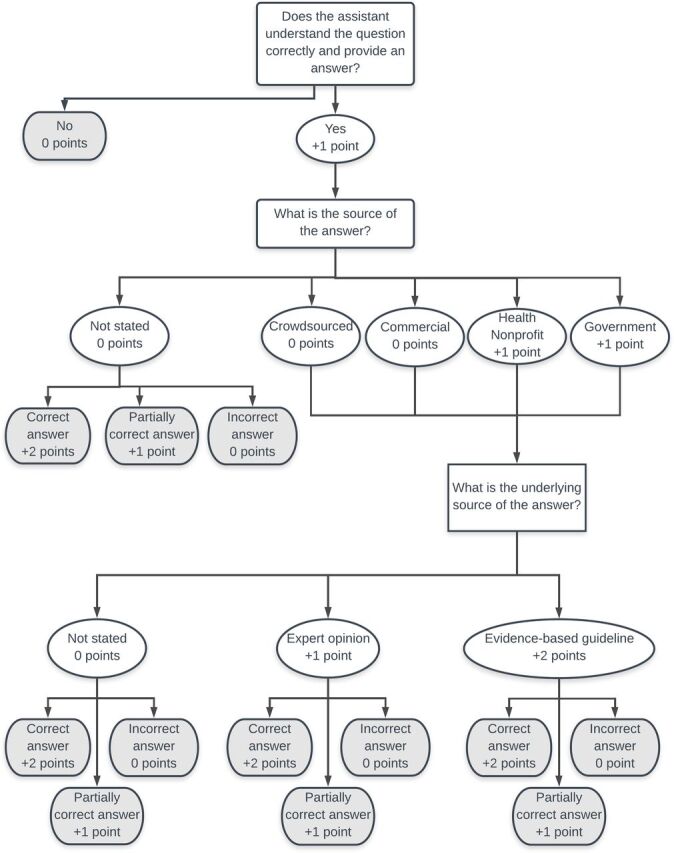

Developing the rubric

To grade the quality of each answer, the authors developed a rubric that assigned points based on author expertise, quality of sources cited and accuracy of the answer provided. The development of the rubric was informed by prior work in health web content evaluation and VA evaluation. The rubric incorporated quality standards for authorship, attribution, disclosure and currency from the JAMA benchmark criteria for evaluating websites.26 The rubric was also informed by the hierarchy of health information/advice created by Boyd and Wilson in their evaluation of smoking cessation advice provided by VAs.14 In their hierarchy, information produced by health agencies, such as the National Health Service (NHS) and the CDC, is grade A, information produced by sites with commercially oriented medical sites, such as WebMD, is grade B, and information produced by non-health organisations and individual publishers is grade C. Our rubric similarly assigned the highest value to government health agencies, such as the CDC, NHS or NIH, and lower value to crowdsourced and non-health websites. In cases where the immediate answer did not come from an expert source and was instead pulled from a for-profit or crowdsourced site, points could be gained if the answer was accurate and/or supported with an expert source citation.

All three VAs provided both an audio answer and a link to the source supporting each answer through the app interface. In determining the accuracy of the answer, both the verbal answer and the link provided as a source for the answer were considered for scoring. To assess how well the VAs processed voice interactions, the rubric assigned points for the VA’s comprehension of the question. The app interfaces also transcribed the text of the questions asked by the user, so the reviewers were able to assess whether or not the assistants had accurately recorded the question. The supporting links were also useful for evaluating which evidence was used to generate each answer. An answer was scored as fully accurate if the source it cited contained the correct answer, even if the VA did not provide the full answer through audio output. Possible scores ranged from 0.0 (VA did not understand the question and/or did not provide an answer) to 6.0 (VA answered the question correctly using an evidence-based government or non-profit source). The authors tested the rubric using a pilot set of 10 questions. Additional categories were added based on the pilot test to create the final rubric (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rubric for evaluating the quality of voice assistant responses.

Data

Data collection

Using two Apple iPads that had been reset to factory mode and had Siri, Alexa and Google Assistant installed as apps, both authors independently asked each VA the sample questions and assigned scores. Both authors speak with American English accents. The iPads ran on iOS V.11.4.1. Because search history can influence search results, the authors took several steps to ensure that the results were depersonalised.27 Each reviewer created new Amazon, Apple and Google accounts to use with each VA application. ‘Siri & Search’ was also turned off in settings to keep the Alexa and Google Assistant apps from learning from Siri’s responses. Location tracking was disabled in each app to avoid having the answers influenced by location-based results. If more than one answer or source was provided, the first source was used for scoring. Author 1 collected data on 10 August 2018. Author 2 collected data on 1–8 October 2018.

Results and discussion

Summary statistics

The authors combined the scores from both reviewers to calculate the overall mean score for each VA. Possible overall means ranged from 0.0 (VA did not understand the question and/or did not provide an answer) to 6.0 (VA answered the question correctly using an evidence-based government or non-profit source). Alexa’s overall mean was 0.9815. Google Assistant’s overall mean was 5.1012, and Siri’s was 5.1574. See table 1 for additional analysis.

Table 1.

Summary performance statistics

| Voice assistant | Alexa | Google Assistant | Siri |

| Mean score | 0.98 | 5.10 | 5.16 |

| VA provided same response to both authors | 62.96% | 70.37% | 68.52% |

| VA understood question and provided answer | 25% | 94% | 94% |

| Average spoken words per answer | 29 | 21 | 13 |

| Most cited source | Wikipedia.org | CDC.gov | CDC.gov |

VA, voice assistant.

Inter-rater reliability for the total score for each answer was strong as measured by an equally weighted Cohen’s kappa of 0.761 (95% CI 0.6908 to 0.8308). It is possible that the kappa statistic was impacted by inconsistency in some responses. Overall, the VAs offered the same answer to both reviewers for 67% of the queries. In instances where both VAs offered the same answer and source, 78% of the reviewer scores were identical. While the rubric was adequate for this pilot exploration of VA health information provision, the reviewers identified a need for more nuanced scoring of the audio answer as an area to increase the reliability of the rubric for future researchers.

Source quality

Google Assistant and Siri both scored highly for understanding the questions and delivering links to expert sources to the user. For most questions, Google Assistant and Siri delivered the recommended link to the reviewers’ devices with a brief audio response, such as ‘Here’s what I found on the web’ or ‘These came back from a search’. Both VAs provided links to evidence-based sources that contained accurate answers for the majority of the questions. The CDC website was the most frequently cited source for both Siri and Google Assistant. This CDC prevalence most likely occurred because many of the sample questions were pulled from CDC websites and demonstrates the ability of the VAs to accurately match voice input to text verbatim online. This finding is also consistent with prior research which found high online visibility for the CDC’s vaccination content.18 Other highly cited sources included expert sources produced by the WHO, the US Department of Health and Human Services, the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Pediatricians. Sources with less transparent funding and editorial processes included procon.org, healthline.com and Wikipedia.

Alexa often responded with ‘Sorry, I don’t know that’, and consequently received a low average score. This low rate of command comprehension supports prior research documenting Alexa’s low comprehension of long natural language phrases.28 In the instances where Alexa offered a spoken response, Wikipedia was the most frequently cited source. Because Wikipedia is editable by the general public and does not undergo peer review, its frequent use as a source also contributed to Alexa’s low score. Online supplementary table S2 contains the transcribed audio output and sources recommended by each device for each question.

bmjhci-2019-100075supp002.pdf (137.2KB, pdf)

Differences in supporting sources might be explained by variations in the search engines powering each VA. Alexa uses Microsoft Bing, and Siri and Google Assistant’s answers are powered by Google search.29 30 These search engines have shared information about medical information partnerships in the past, and these partnerships may explain variations in source selection.31 32

Audio output

Although Siri had the highest score for quality of answers, it used the fewest spoken words of all VAs. Alexa had the longest average spoken response in spite of having the lowest rate of understanding and providing answers to the questions. The length of audio output may offer insight into how the developers of each device envision the role of VAs as information assistants. With the brief audio responses offered by Google Assistant and Siri, the responsibility of assessing the quality of the information and locating the most important sections on the web page is placed on the user. The devices primarily function as a neutral voice-initiated web search.

Alexa’s longer answers may reflect an attempt to deliver audio-only answers that do not require additional reading. Preliminary usability research suggests that users prefer audio-only answers to those delivered via screen.33 Of the devices sampled for this study, Alexa is the only VA with documentation that claims it can ‘answer questions about medical topics using information compiled from trusted sources’.34 Alexa was the VA most likely to offer an audio-only answer without links to additional reading. Although these answers were factually correct, they often included grammar errors, as exemplified in this response to the question ‘are vaccines bad?’:

According to data from the United States Department of Health and Human Services: I know about twenty-two vaccines including the chickenpox vaccine whose health effect is getting vaccinated is the best way to prevent chickenpox. Getting the chickenpox vaccine is much safer than getting chickenpox. Influenza vaccine whose health effect is getting vaccinated every years is the best way to lower your chances of getting the flu…

Based on the data collected, Alexa is behind Google Assistant and Siri in its ability to process natural language health queries and deliver an answer from a high-quality source. Although it did not function as an effective health information assistant at the time of data collection, Alexa’s approach to audio-only responses raises larger questions about future directions for VAs as medical information tools. It is appealing to envision a convenient hands-free system that delivers evidence-based answers to consumers in easily digestible lengths. Compared to an assistant that initiates a web search on the user’s mobile device and delivers a web page that must be read, an audio-only system would improve accessibility and potentially provide health information to consumers in less time. However, the audio-only method also raises ethical concerns about transparency and bias in the creation of answers, particularly surrounding health topics that have been the target of past misinformation campaigns. The audio-only approach may also lead to a reduced choice of sources for information for consumers because they would not be offered multiple sources to explore. Recent industry analysis has explored the risks of reduced consumer choice with the ‘one perfect answer’ audio-only approach to voice search, but the implications for health information provision remain unclear.35

More research is needed to understand whether the audio-only approach or the voice-powered web search approach is more effective for delivering consumer health information. The companies developing VAs should also be more transparent about how their search algorithms process health queries.

Third-party apps

Third-party apps are an additional model for health information delivery through VAs. Amazon allows third parties, such as WebMD and Boston Children’s Hospital, to create Alexa Skills, which users can enable in the Alexa Skills Store.8 Google similarly allows users to enable third-party apps through the Google Assistant app. A recent evaluation of third-party VA apps found 300 ‘health and fitness’ apps in the Alexa Skills store and 9 available for Google Assistant.7 Although the reviewers of the present study did not evaluate third-party apps, Google Assistant offered to let them ‘talk to WebMD’ in response to the question ‘are vaccines tested?’. This active recommendation of a third-party health information tool demonstrates an alternative model in which VAs connect consumers to third-party skills designed to address specific topics. This model may reduce VA manufacturers’ liability for offering medical advice, but it is currently unclear what quality standards are used to evaluate third-party health app developers.

Limitations

The reviewers asked questions and gathered data on different dates, which may have led to variations in VA answers. However, the rubric was designed to evaluate answer quality and did not penalise answers from varying sources if the answer was correct and from an authoritative source. The scoring rubric was developed for this exploratory study. As such, it has not been assessed for reliability or validity and needs refinement in future studies to keep pace with new developments in VA technology. Additionally, because all accounts were set to default mode and cleared of search history, the VA answers may not reflect use cases where search results are tailored to the local use history of individual users. Finally, the authors chose to include the link provided via screen in the quality assessment. Some preliminary data show that users prefer audio output, so the overall scores for all assistants may have been lower if the rubric evaluated audio output only.33

Conclusions

This study assessed health information provided by three VAs. By incorporating user-generated health questions about vaccines into the set of test questions, the authors created realistic natural language use cases to test VA performance. After evaluating VA responses using a novel evaluation rubric, the authors found that Google Assistant and Siri understood voice queries accurately and provided users with links to authoritative sources about vaccination. Alexa performed poorly at understanding voice queries and did not draw answers from high-quality information sources. However, Alexa attempted to deliver audio-only answers more frequently than other VAs, illustrating a potential alternative approach to VA of health information delivery. Existing frameworks for information evaluation need to be adapted to better assess the quality of health information provided by these tools and the health and technological literacy levels required to use them.

Those involved in patient education should be aware of the increasing popularity of VAs and the high variability of results between users and devices. Consumers should also push for greater usability and transparency about information partnerships as the health information delivery capabilities of these devices expand in the future.

Footnotes

Contributors: ECA and RRH designed the study and evaluation rubric, and collected data. ECA analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. RRH provided feedback on the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Fox S, Duggan M. Health online 2018. Pew Research Center 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inside Baidu’s Plan To Beat Google By Taking Search Out Of The Text Era. Available: https://www.fastcompany.com/3035721/baidu-is-taking-search-out-of-text-era-and-taking-on-google-with-deep-learning [Accessed 30 May 2019].

- 3.Rehkopf F. Voice search optimization (VSO): digital PR's new frontier. Communication World 2019:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gartner top strategic predictions for 2018 and beyond. Available: https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/gartner-top-strategic-predictions-for-2018-and-beyond/ [Accessed 30 May 2019].

- 5.The growing footprint of digital assistants in the United States. Euromonitor 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Data breakdown, how consumers use smart speakers today. Available: https://voicebot.ai/2018/03/21/data-breakdown-consumers-use-smart-speakers-today/ [Accessed 30 May 2019].

- 7.Chung AE, Griffin AC, Selezneva D, et al. Health and fitness Apps for Hands-Free Voice-Activated assistants: content analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e174. 10.2196/mhealth.9705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Introducing new Alexa healthcare skills. Available: https://developer.amazon.com/blogs/alexa/post/ff33dbc7-6cf5-4db8-b203-99144a251a21/introducing-new-alexa-healthcare-skills [Accessed 29 May 2019].

- 9.Fahy E, Hardikar R, Fox A, et al. Quality of patient health information on the Internet: reviewing a complex and evolving landscape. Australas Med J 2014;7:24–8. 10.4066/AMJ.2014.1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joury A, Joraid A, Alqahtani F, et al. The variation in quality and content of patient-focused health information on the Internet for otitis media. Child Care Health Dev 2018;44:221–6. 10.1111/cch.12524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrant K, Heazell AEP. Online information for women and their families regarding reduced fetal movements is of variable quality, readability and accountability. Midwifery 2016;34:72–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2015.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamwela V, Ahmed W, Bath PA. Evaluation of websites that contain information relating to malaria in pregnancy. Public Health 2018;157:50–2. 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miner AS, Milstein A, Schueller S, et al. Smartphone-Based Conversational agents and responses to questions about mental health, interpersonal violence, and physical health. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:619–25. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd M, Wilson N. Just ask Siri? A pilot study comparing smartphone digital assistants and laptop Google searches for smoking cessation advice. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194811. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson N, MacDonald EJ, Mansoor OD, et al. In bed with Siri and Google assistant: a comparison of sexual health advice. BMJ 2017;359. 10.1136/bmj.j5635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Getman R, Helmi M, Roberts H, et al. Vaccine Hesitancy and online information: the influence of digital networks. Health Educ Behav 2018;45:599–606. 10.1177/1090198117739673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kata A. Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm--an overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine 2012;30:3778–89. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiley KE, Steffens M, Berry N, et al. An audit of the quality of online immunisation information available to Australian parents. BMC Public Health 2017;17:76. 10.1186/s12889-016-3933-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz, Jeanette B.|Bell, Robert A. understanding vaccination resistance: vaccine search term selection bias and the valence of retrieved information. Vaccine 2014;32:5776–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.2019 voice report: from answers to action: customer adoption of voice technology and digital assistants 2019.

- 21.Smart Homes - US - May 2019: Smart Speaker Brand Ownership and Consideration 2019.

- 22.Infant immunizations FAQs. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/parent-questions.html [Accessed Aug 6, 2018].

- 23.Parents | infant immunizations frequently asked questions | CDC. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/parent-questions.html [Accessed 30 Jul 2018].

- 24.AnswerThePublic: that free visual keyword research & content ideas tool.

- 25.How to optimize for voice search. Available: https://searchengineland.com/optimize-voice-search-273849 [Accessed 30 Jul 2018].

- 26.Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA. Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: Caveant lector et viewor--Let the reader and viewer beware. JAMA 1997;277:1244–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Personalized search for everyone. Available: https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2009/12/personalized-search-for-everyone.html [Accessed 17 Feb 2019].

- 28.Dizon G. Using intelligent personal assistants for second language learning: a case study of Alexa. TESOL Journal 2017;8:811–30. 10.1002/tesj.353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Microsoft and Amazon partner to integrate Alexa and Cortana digital assistants. Available: https://www.theverge.com/2017/8/30/16224876/microsoft-amazon-cortana-alexa-partnership [Accessed 17 Feb 2019].

- 30.Apple switches from Bing to Google for Siri web search results on iOS and spotlight on MAC. Available: http://social.techcrunch.com/2017/09/25/apple-switches-from-bing-to-google-for-siri-web-search-results-on-ios-and-spotlight-on-mac/ [Accessed 19 Feb 2019].

- 31.Search for medical information on Google. Available: https://support.google.com/websearch/answer/2364942?p=medical_conditions&visit_id=1-636259790195156908-3652033102&rd=1 [Accessed 30 Jul 2018].

- 32.Searching for health information. Available: https://blogs.bing.com/search/2009/07/07/searching-for-health-information/ [Accessed 19 Feb 2019].

- 33.Intelligent assistants have poor usability: a user study of Alexa, Google assistant, and Siri. Available: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/intelligent-assistant-usability/ [Accessed 29 May 2019].

- 34.Ask Alexa medical questions. Available: https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=G202210470 [Accessed 17 Feb 2019].

- 35.Vlahos J. Amazon Alexa and the Search for the One Perfect Answer. Wired, 2019. Available: https://www.wired.com/story/amazon-alexa-search-for-the-one-perfect-answer/ [Accessed 3 Sep 2019].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjhci-2019-100075supp001.pdf (360.5KB, pdf)

bmjhci-2019-100075supp002.pdf (137.2KB, pdf)