Abstract

The purpose of this review was to identify knowledge gaps within the literature regarding the impact of opioid use disorder, specific to immigrants in the United States, by addressing the following questions: 1) What is presented in the literature about the impact of opioid use disorder (OUD) and the opioid epidemic on immigrants in the United States?; and 2) What role does culture play in the opioid use disorder experiences of immigrants in the United States? Nineteen research articles were uncovered that addressed immigrants in the U.S. and opioid use disorder. The following themes prevailed: 1) OUD comparisons, 2) OUD comorbidities, 3) disparate OUD treatment engagement, and 4) the role of country of origin. Limited review findings support the need for future research on the topic of opioid misuse among immigrants in the United States. The authors elaborated on additional issues that influence OUD rates and warrant further exploration. Matters related to the potential positive roles of religion and faith leaders, cultural perceptions and expectations about gender roles, immigration status, ethnically diverse needs among sub-groups of immigrants, the role of geographic location within the U.S., and the implications of COVID-19 on OUD among immigrants need to be addressed to alleviate the deleterious impact of opioid misuse among immigrants.

Keywords: immigrant, opioid, treatment

The United States leads the world in the number of foreign-born residents, with over 44 million immigrants in the United States, or about 14% of the population, as of 2018 (Budiman, 2020). There is substantial evidence in the literature that being an immigrant can limit access to healthcare and treatment (Azar et al., 2020; Greenaway et al., 2020; Iacobucci, 2020). A number of factors likely contribute to these barriers, including a lack of proficiency in English, cultural differences in views on health and rehabilitation, a lack of health insurance, difficulty navigating the complex health care systems, and socioeconomic status. These factors necessitate additional education and training for clinicians who serve immigrants, to ensure that they can meet the varying health care needs of this patient population and understand their unique circumstances. One important area of health care where immigrants may face additional obstacles is in regard to experiences with opioid misuse and opioid use disorder (OUD).

Opioids are a class of drugs designed to alleviate chronic pain and have a high propensity for addiction (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021). The opioid epidemic in the U.S. is mostly attributed to patients initially having received prescriptions for pain medications, starting in the 1990s, which ultimately resulted in them experiencing chemical dependence (CDC, 2021). Opioid use disorder is a diagnosis that is the consequence of 12 months of opioid misuse, that involves at least two of the criteria outlined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5th Edition (i.e., failed attempts to control use, negative social implications, withdrawal symptoms) (Connery, 2015). Subsequent reduction or termination of these prescriptions has led individuals with OUD to seek more accessible and affordable street drugs as alternatives – most commonly heroin, with fentanyl use on the rise. More than three-quarters of a million people have died in the U.S. from a drug overdose since 1999, the start of the first wave of the opioid epidemic (United States Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2018). By 2018, two-thirds of all drugs involved in these deaths were opioids. And by 2017, citing groups labeled as “Whites, overall,” “Blacks, overall,” and “Hispanics, overall,” nearly all ethnic groups experienced increases in opioid-related deaths at varying degrees (Lippold, Jones, O’Malley, & Giroir, 2019). While much can be extracted and generalized from data stratified by race, plenty remains elusive within these data as these groupings give the impression of homogeneity, when in fact, they are quite heterogeneous. And people of color are more likely to die from an opioid overdose, even though their use rates are lower than Whites (Christensen, Berkley-Patton, Bauer, Thompson, & Burgin, 2020).

The importance of focusing on the immigrant experience surrounding opioid misuse and addiction is severalfold. Firstly, immigrants represent a diverse group, based on ethnicity and country of origin – which are likely to impact treatment-seeking behaviors and the ability to access treatment. Secondly, immigrants interface with the legal system inherently and in ways that American citizens do not. According to the Immigration and Nationality Act, an immigrant can be removed from the U.S. if it is determined that they are addicted to substances, which can impact motivations to pursue treatment (Garcia, 2018; Kagotho, Maleku, Baaklini, Karandikar, & Mengo, 2020). Policy and practice form an intimate relationship in health and human services, as legislation is often a direct source of the programming, funding, and resources that patients and clients rely on for treatment. There may be implications for policy and a need for the knowledge of policy by practitioners who provide services to immigrants.

With these important factors affecting access to OUD treatment, it is critical to specifically study treatment approaches that may better facilitate access to care for immigrants. The purpose of this qualitative scoping review was to discover the breadth of studies that have specifically examined OUD and its treatment in immigrant populations and to try to identify common themes as well as potential gaps in the literature. Our hope is to inform future research in this area, and to guide policymakers, service providers, and educators.

Method

This scoping review was guided by the methodological framework and iterative process defined by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). We focused the review on the topic of the opioid epidemic in the U.S., as it relates to immigrants’ health and treatment. To that end, the search was guided by the following question: what is presented in the literature about OUD and the opioid epidemic, as they impact immigrants in the United States? For this study, an immigrant refers to someone who has migrated to the U.S. during their lifetime, as a non-U.S. citizen. Thus, the search terms that were used included: (immigrant* OR refugee* OR “first-generation immigrant”) AND (opioid* OR opioid use disorder). These keywords were consistently searched across each database in various combinations and connected with Boolean operators. We searched Web of Science, PubMed, Google Scholar, Summon (Penn State University Libraries), and ProQuest in May 2021. The searches were limited to publication dates from 1999, the first year of the opioid epidemic in the United States (CDC, 2018). Three of the authors reviewed the article titles and abstracts based on the inclusion criteria of 1) studies examining opioids or OUD and 2) focusing on adult immigrants living in the United States. The team then examined each study further based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were excluded that discussed prescription opiates but did not directly discuss issues of misuse or addiction. Studies that included children as the primary population or focused on populations from U.S. territories such as Puerto Rico (rather than immigrants born outside of the U.S. and its territories) were also excluded. Likewise, studies that focused on populations that were born in the U.S., such as first-generation children of immigrants were excluded because the focus of this review was on immigrants born outside of the U.S. and its territories. Finally, articles which were categorized as non-research were also excluded.

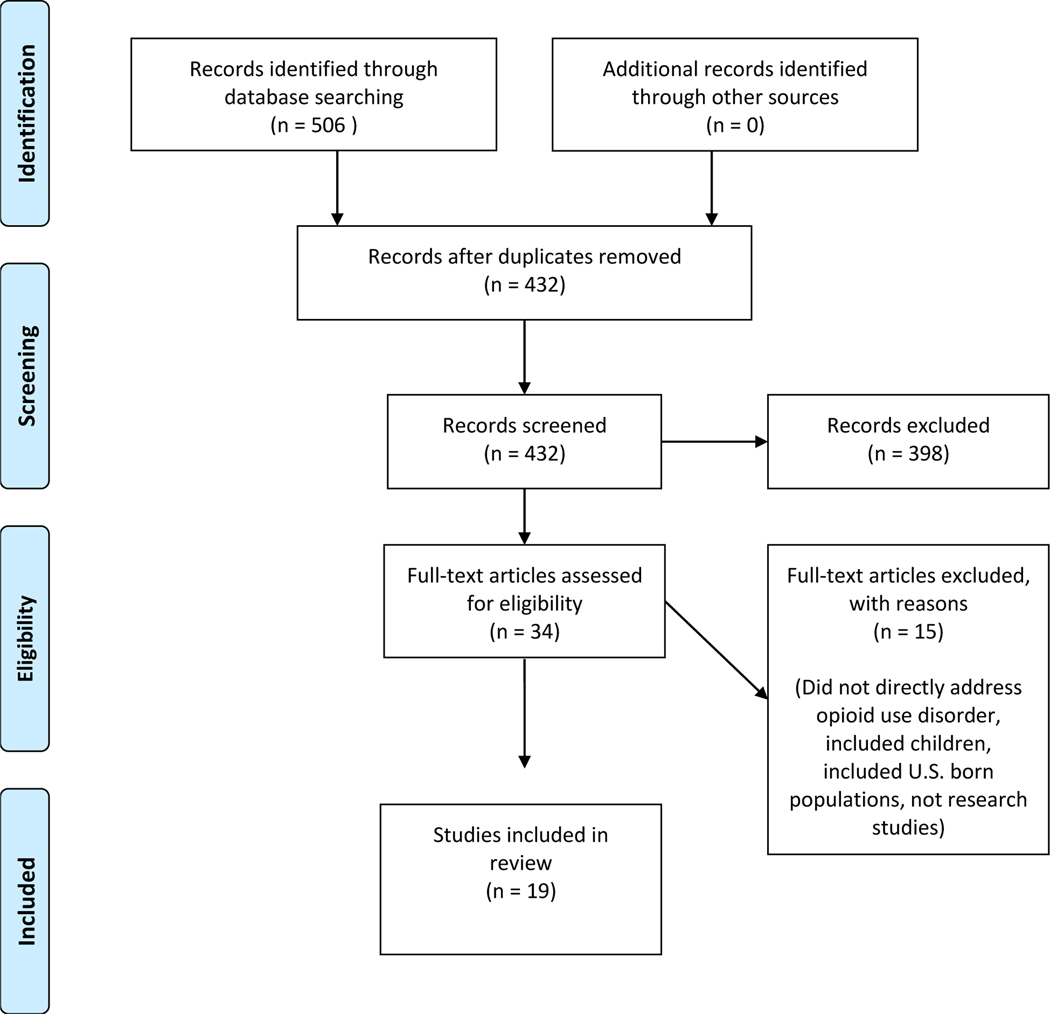

A total of 506 articles were identified as potential sources after conducting literature searches. An initial screening for duplicates identified 75 articles to be excluded. A second screening of the remaining articles with a title and abstract review alone, based on the inclusion criteria resulted in a further 398 articles being excluded. The remaining 34 articles were screened during a third full-text review according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Based on this final review, 19 articles were included in this scoping review. The PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1 presents the article selection process.

Figure 1:

PRISMA flow chart

Adapted from Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G., & The PRISMA Group (2009)

Two authors reviewed the selected articles more closely, through a manual thematic analysis process, to identify each article’s research areas of focus and gaps for future research inquiry. Using a descriptive-analytical method, we charted a list of various recurring topics on Microsoft Excel – such as research goals, ethnic populations studied, research questions posed, participant group characteristics, research outcomes, and types of substances referenced (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Themes quickly and naturally emerged, due to the small number of articles overall and the specificity of the topic area (Saldaña, 2009). Second and third cycles of reviews were conducted to properly attribute the articles with their respective themes, and to rename themes for consolidation and to improve contextualization.

Results

Of these 19 articles, seven studies used data from surveys/web-based questionnaires, four involved interviews, five were mixed-methods, one was a case study, one was a medical chart review, and one was a clinical observation. In terms of the populations and countries of origin included in this review, five studies involved immigrants from across the globe, six studies involved immigrants described as Latino/Hispanic/Central and/or South American. Four studies focused on immigrants from the former Soviet Union, two studied Hmong immigrants from southeast Asia, one study focused on Indian immigrants, and in one study the countries of origin were not explicitly stated.

Themes

The authors retrieved 19 articles related to OUD and immigrants living in the US. The articles included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research studies. Several recurrent themes arose in these studies involving immigrants, with the four most prevailing being 1) OUD comparisons, 2) OUD comorbidities, 3) disparate OUD treatment engagement, and 4) country of origin and OUD.

Opioid use disorder comparisons

The first pattern was the frequent comparison of rates of OUD between U.S. born individuals and foreign-born individuals. In the 11 articles that compared U.S. born individuals to individuals born outside of the U.S., all but one of the studies concluded that the immigrants interviewed in their studies experienced lower rates of opioid misuse or OUD, as compared to the U.S. born respondents. This phenomenon is known as the immigrant paradox, that immigrants in similar circumstances with non-immigrants will still exhibit lesser instances of opioid misuse or abuse (Bart, 2018; Cano, 2019; Guarino, Marsch, Deren, Straussner, & Teper, 2015; Guarino, Moore, Marsch, & Florio, 2012; Isralowitz, Straussner, Vogt, & Chtenguelov, 2002; Parker, Lopez-Quintero, & Anthony, 2018; Rodriguez Guzman, 2017; Salas-Wright & Vaughn, 2014; Salas-Wright, Vaughn, Clark Goings, Cordova, & Schwartz, 2018; Salas-Wright, Vaughn, Clark, Terzis, & Cordova, 2014; Wilson, Mosalpuria, & Stimpson, 2020). In other words, research suggests that being an immigrant can be a protective factor against engaging in certain high-risk behaviors. This is paradoxical because the expectation is for the opposite to be the case, due to the various levels of hardship that immigrants typically face. One partial explanation may be that immigrants appear less likely to be prescribed opioids than non-immigrants (Wilson, Mosalpuria, & Stimpson, 2020). Finally, the one exception to the trend of lower OUD rates among immigrants was a study by Guarino et al. that focused on immigrants from the Former Soviet Union (Guarino, Moore, Marsch, & Florio, 2012). The presence of cultural factors that are typically protective for immigrants, such as valuing educational achievement or strong family ties, did not alleviate substance misuse levels for FSU immigrants as they typically would for other immigrant groups in this study. A possible reason for this could have been the presence of other deleterious circumstances that outweighed the benefits of existing protective factors – such as infectious disease, the trauma of immigration during adolescence that this particular participant pool experienced, and subsequent peer influence from those of the same ethnic background (Guarino et al., 2012).

The second pattern regarding misuse of opioids was the comparison of one generation of immigrants to another. Although immigrants are less likely to experience OUD than Americans, that likelihood increases as their number of years of residence in the U.S. increases. We also see an increase in likelihood of use and misuse with each subsequent generation of descendants (Kagotho et al., 2020; Cano, 2019; Guarino et al., 2015; Rodriguez Guzman, 2017; Salas-Wright et al., 2014; Guarino et al., 2012; Gunn & Guarino, 2016; Sites & Davis, 2019). In other words, the second generation has a higher propensity for opioid misuse than its immigrant parents, the third generation has a higher propensity than the second generation, and so on.

Opioid use disorder and comorbidities

While adverse consequences from OUD are similar for immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. adults, contextual factors stemming from having marginalized identities and issues related to acculturation bring nuance and susceptibility for comorbid conditions for immigrants in particular (i.e., infectious diseases, psychiatric conditions, polysubstance use) (Bart, 2018; Epelbaum et al., 2010; Guarino et al., 2012; Guarino et al., 2015; Salas-Wright & Vaughn, 2014; Salas-Wright et al., 2018; Salas-Wright et al., 2014; ). Alongside the differences in patterns and acceptability of drug use in the U.S., as compared to immigrant countries of origin, the additional stressors from migration (i.e., family separation, exposure to violence, poverty) may lead to psychiatric comorbid conditions (i.e., depression and anxiety) and/or poly-substance use as self-medication among immigrants (Kagotho, Maleku, Baaklini, Karandikar, & Mengo, 2020).

Acculturation is a salient phenomenon that connects opioid use disorder with several comorbidities. Immigrants consciously and subconsciously adopt the customs, beliefs, and behaviors of the country within which they now reside. These adoptions impact habits that affect health. Proxies for acculturation, including English language usage and proficiency, length of time since immigrating, and immigrant generations, are known correlates of illicit substance use, specifically opioid use (Cano et al., 2019). In addition, changes in cultural norms and behaviors may increase substance use (Cano et al., 2019). Specific to prescription opioid use, changes in cultural views on physical pain and expectations of living in pain may lead to increased use of prescription opioids and increased misuse opportunities (Cano et al., 2019).

Specific to the opioid epidemic, the acculturation process has been linked with higher odds of opioid use among Hispanic immigrants, with subsequent generations following first generation immigrants having an even greater likelihood of opioid use, in addition to alcohol and drug use in general (Cano, 2019; Salas-Wright et al., 2014). Further marginalized individuals, such as undocumented immigrants, may have an increased risk of OUD and comorbid conditions. A case study by Epelbaum et al. detailed the story of a 35-year-old Brazilian immigrant woman with multiple psychiatric conditions, that led to several suicide attempts, and an OUD diagnosis after immigrating to the United States (2010). In this clinical case, the likely triggers for the mental illnesses were an undocumented status, concerns surrounding acculturation, and unemployment.

Particularly high rates of opioid use accompanied by non-opioid substance use, and injection drug use in the countries of origin are comorbidities that present unique challenges. In a qualitative study of U.S. immigrants from the former Soviet Union (FSU) who had been shown to have elevated rates of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), Guarino and colleagues noted that the high substance use rates and high-risk environments of their former countries might have created social norms that persisted in the participants’ lives post-immigration (2012). Moreover, the normalization of high-risk drug using behaviors in certain environmental contexts and social networks may increase the risks associated with drug using behaviors of U.S. immigrants and lead to excess comorbid conditions (Guarino et al., 2015; Guarino et al., 2012). For instance, among FSU immigrants who injected drugs, sharing injection related materials were common, where 69% reported being “not at all” or “slightly” worried about contracting HCV, a virus that affects all people who inject drugs upwards of 50–90% (Guarino et al., 2015).

Disparate opioid use disorder treatment engagement

Among immigrants with OUD living in the U.S., enrollment rates in Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) programs, treatment choices, and reports of barriers to treatment, treatment outcomes, and relapse rates are all low and underreported (Kagotho et al., 2020; Bart, 2018, Guarino et al., 2015; Gunn & Guarino, 2016; Fleiz, Villatoro, Dominguez, Bustos, & Medina-Mora, 2019). The potential reasons for the above problems are very complex and multifaceted and include stigmatization from providers and family members, inaccessibility rooted in geographic distance from treatment, levels of acculturation and cultural perspectives, language barriers, limited participation in human research, inadequate health information and education, immigration status and fear of deportation, low-income status, and limited insurance coverage for substance use treatment (Guarino et al., 2015; Gunn & Guarino, 2016; Isralowitz et al., 2002; Kagotho et al., 2020; Rodrigue Guzman, 2017). Furthermore, questions remain on the impact of ethnic, cultural, and psychosocial influences on therapy outcomes among immigrants with OUD. For instance, several studies have evaluated the treatment outcomes in Hmong immigrants in the U.S., many as refugees from Laos following the Vietnam conflict, who received methadone maintenance in a single urban clinic. Given their opium cultivation history and the use of opium in their traditional medicine practices, this distinct ethnic minority group may exhibit different psychosocial and culturally mediated processes that can affect treatment engagement, perceptions, and outcomes. Bart et al. showed that Hmong had significantly greater 1-year treatment program retention rates (79.8% vs. 63.5% for non-Hmong) and required lower doses of methadone for stabilization compared with non-Hmong. A more recent study, utilizing structured and semi-structured interviews, found that the Hmong involved in MAT were more likely to be male, older, and on lower methadone doses compared to the non-Hmong group (Bart, Wang, Hodges, Nolan, & Carlson, 2012). The Hmong also had significantly lower Addiction Severity Index composite scores and lower rates of DSM non-substance use disorder diagnoses such as anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (Bart, 2018). Fleiz et al. interviewed a convenience sample of 600 individuals who received treatment for heroin use in Mexico’s northern border region and found that the experience of migration to the U.S. predicted whether they sought methadone treatment versus public or private treatment or informal care (i.e., through self-help groups, religious care) (2019).

This review also identified studies that characterized immigrants’ experiences with other treatment programs and preventive strategies for OUD such as needle exchange and other harm reduction approaches. Gunn and Guarino conducted a structured assessment in 80 opioid-using FSU immigrants living in New York City (Gunn & Guarino, 2016). Among current injection drug users, only 40% reported using a Syringe Exchange Program (SEP) in the past year. In contrast to the cultural acceptance of the heavy drinking of alcohol, extreme stigmatization of drug users in the FSU immigrant community made them unwilling to use mobile SEP and other drug-related services, with the fear of permanently spoiling their identities in their communities. This has also been reported in earlier interviews conducted by Guarino et al (2012).

The researchers identified multiple barriers to OUD treatment for immigrants in the studies reviewed. Social stigma of drug use was found to be a common barrier to drug-related service utilization across different immigrant communities (Bart, 2018; Guarino et al., 2012; Bart, 2012). For instance, in the FSU immigrant community, the pervasive stigmatization towards drug users that views substance abuse as a moral failure, rooted in punitive Soviet-era drug policies, had deterred youth from accessing drug treatment and services (Isralowitz et al., 2002; Gunn & Guarino, 2016). Such stigmatization also contributed to parents’ reluctance to seek treatment for their children after the initial early signs, until the opioid use problems became severe (Gunn & Guarino, 2016). In addition to the community and families, stigma within drug-using peer groups and self-stigma, especially for individuals using harsher drugs like heroin or injection drugs, further exacerbated their shame, isolation, and acculturation stress. This made accessing drug treatment and harm reduction services even more challenging for them. The historically high mistrust of the government could have also made the FSU immigrants fear participating in treatment and revealing their substance use disorder diagnoses (Isralowitz et al., 2002).

Another issue related to treatment barriers was the role that having an undocumented status played in an individual’s inability to access drug treatment services (Epelbaum, Taylor, & Dekleva, 2010). Being undocumented prohibits full-time employment and the health benefits that would accompany it. Fuzhounese (Chinese) immigrants who were undocumented were six times more likely to be hospitalized for psychiatric conditions than those who were documented (Epelbaum et al., 2010). This phenomenon can include substance use disorder and a variety of co-occurring mental health conditions exacerbated by trauma. Without insurance, the use of emergency services is also more likely among this group. Yet there are many who avoid treatment for fear of arrest and deportation (Gunn & Guarino, 2016). Drug addiction without treatment raises the likelihood of criminal behavior for the purposes of maintaining the habit, this is true for immigrants and non-immigrants alike (Epelbaum et al., 2010). For instance, individuals with substance use disorders sometimes turn to theft, sex work, and the sale of drugs to maintain an income that can support the dependance. These behaviors can make an individual more likely to interface with the criminal justice system, which ultimately can lead to the deportation that they might fear.

Country of origin and opioid use disorder

Immigrants’ countries of origin played multiple roles in experiences around opioid use. For instance, a significant history of substance use practices in a country can increase the likelihood of use upon arrival in America, as was seen with certain groups of Hispanic heritage immigrants and immigrants from the Former Soviet Union (Cano, 2019; Guarino et al., 2015; Guarino et al., 2012). Conversely, people within the FSU culture that fostered stigma and perpetuated feelings of shame or a lack of understanding about substance use disorder tended to preserve these worldviews upon arrival in the United States (Gunn & Guarino, 2016). In addition, the literature supported that certain stressors related to the migration process could increase the likelihood of acquiring mental health conditions, including substance use disorder. It was found that among Mexicans, Cubans, Guatemalans, and El Salvadorians in the United States, low education attainment was a risk factor for increased prevalence of psychiatric conditions, and strong support systems were a protective factor against psychiatric conditions (Goddard, 2016).

Non-native speakers of English from India who faced language barriers upon arrival, increased social and political discrimination in the U.S., and who felt greater pressure to acclimate because of starker differences in culture were at greater risk of stress and subsequent psychiatric disorders and substance-related problems (Gholkar, 2007). These are examples of acculturative stress, life difficulties that are experienced as outliers in comparison to everyday, traditional life stressors. These are stress-inducing factors that are particular to the immigration experience and rooted in barriers caused by being culturally foreign. Acculturative stress is a critical concept to consider regarding the experiences of immigrants because it adds to any other, more typical life stressors that they experience and that the average American experiences (i.e., economic instability, unemployment, a global pandemic). Chronic acculturative stress can result in escapism as a coping mechanism, such as a tendency toward the abuse of substances. Assimilation Theory posits that substance misuse increases as acculturation increases (Gholkar, 2007). In Bart’s 2018 study, Hmong participants who were older in age attributed their introduction to opium and subsequent dependance to Vietnam war-related injuries and were more likely to have entered the U.S. as refugees. Interviews with service providers of immigrant groups expressed the importance of further research that disaggregates diverse groups of immigrants and honors the heterogeneity of their experiences and identities (Kagotho et al., 2020). Country of origin also plays a significant role in the phenomenon of the refugee paradox, where refugees are far less likely to experience OUD or other SUDs that non-refugee immigrants (Salas-Wright & Vaughn, 2014).

Discussion

This scoping review identified several prevailing themes that are important to ensure that rehabilitation service providers are able to tailor opioid prevention and treatment efforts to immigrant populations. First, while OUD rates tend to be lower among immigrants, rates tend to increase with acculturation - with higher rates among second and third generation immigrants. Second, immigrants face a number of important treatment barriers. Immigration status may severely limit treatment access, which only further exacerbates barriers due to stigma, which may vary on the cultural norms of different immigrant groups. Furthermore, because these barriers may limit treatment, immigrants with OUD may face delayed and complex treatment needs due to higher rates of comorbid behavioral health conditions - including depression and anxiety. Higher rates of OUD may be driven, in part, by adverse experiences in terms of exposure to the stresses of immigration, adapting to life in a new country, and related issues.

Future research recommendations

There are many relevant issues that we propose warrant further exploration but are currently absent or scant in the research literature. These topics include the influence of geographic location within the U.S. on OUD treatment for immigrants, social perceptions vs. facts about immigrants and drug-related criminal activity, the role of spirituality and religion in OUD treatment among immigrants, the role that gender plays in understanding and treating OUD among immigrants, the impact of variations in state laws on immigrant experiences with OUD, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on OUD and treatment among immigrants.

Country of origin-related geographic influences on OUD within immigrant populations remained a key theme noted in the literature. However, domestic geographic and place-based influences within the U.S. on opioid use remained notably absent in discussion of use patterns in immigrant populations. For instance, the acculturation process may lead to increased access to prescription opioids, as the U.S. prescribing rates are unprecedented compared to other countries (Humphreys, 2017). Of particular interest is the distinction between urban and rural immigrant populations regarding both use and access to treatment provision. The opioid crisis has differentially affected rural populations as compared to urban populations, with notable regional differences associated with use patterns within rural localities, but it is unclear if immigrant populations differ from settled populations due to lack of research (Hancock, Mennenga, King, Andrilla, Larson, & Schou, 2017; Schranz, Barrett, Hurt, Malvestutto, & Miller, 2018) Further, rural populations have less access to treatment as compared to urban populations. Therefore, immigrant populations within rural areas may face difficulties accessing treatment and rehabilitation services. Also, due to the high amount of immigrant seasonal agricultural laborers within rural areas, there may be cyclical differences in treatment needs and use patterns that current data collection mechanisms may not fully capture.

While immigrant populations traditionally have lower criminal activity rates, as compared to native-born populations, there remains a xenophobic perception that immigrants bring with them drug-related criminal activity. We found minimal discussion on opioid-related criminal activity within immigrant populations within the literature. However, there remains a large focus on immigrants, particularly Mexican populations, with regards to opioid-related drug distribution and trafficking activity, from both popular press and governmental perspectives (Quinones, 2016; Drug Enforcement Administration [DEA], 2021). Greater attention is needed to disentangle the involvement in drug-related criminal activity noted within criminal justice reports to understand immigrant participation in these activities.

Faith and the opioid epidemic intersect in a variety of ways, and this was touched on lightly across the literature. In the U.S., 73% of addiction treatment programs have a spirituality-based component, as seen in programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Adult & Teen Challenge (Alcoholics Anonymous [AA], 2014; Grim & Grim, 2019; Adult & Teen Challenge, 2021). Studies revealed that faith is a positive factor in addiction prevention and treatment and that religious behavior (i.e., church attendance) had a greater protective effect against substance use when compared to religious faith (Acheampong et al., 2016; Grim & Grim, 2019; Mak, 2019). Immigrant groups tend to be just as religious or more religious and spiritual than American natives, and more than foreigners who are more acculturated in the host country (Garcia-Munoz & Neuman, 2012; Massey & Higgins, 2011; Sanchez, Dillon, Ruffin, & De La Rosa, 2012). A study examining factors influencing opioid use in a church population reported that 53% of participants had an opioid prescription at some point with 31% reporting opioid prescription use in the last year (Christensen et al., 2020). Faith-based places offer a connection to a community and social network (Mak, 2019; Christensen et al., 2020). Faith leaders can bridge conversations between themselves and leaders in science by acting as brokers of trust, facilitating open conversations about treatment, resources, and stigma (Akande, 2021; McKenzie & Satcher, 2021).

The implications of gender within culture in understanding OUD within immigrant communities needs further exploration. Research into immigrants from the FSU highlighted greater stigma and shame against women with opioid use disorder. Gender role expectations around purity and associations of drug use with prostitution created perceptions of female drug use as being a greater deviance from acceptability than male drug use (Gunn & Guarino, 2016).

It would be worthwhile for researchers and practitioners to be aware of the state policies and programs specific to the clients and patients they serve. States vary in the types of healthcare-related programs that exist and that are available to immigrants, and they also vary in how accessible they are to immigrants. An example of these variations is the concept of the sanctuary city. According to the American Immigration Council, the term “sanctuary city” is an unofficial label with different meanings across these cities, but they have large immigrant populations and claim the name (2017). Generally, the goal of a sanctuary city is to foster a sense of security and trust, mainly between undocumented immigrants, local officials, and police departments – particularly when federal policies may seem to contradict these efforts. Local efforts may focus on making drivers’ licenses attainable, thwarting efforts to deport individuals to countries of origin, and ensuring access to critical healthcare (Aboii, 2016). Further research is also needed into the political debate that sanctuary city policies make the opioid epidemic worse (Vaughan, 2018).

Finally, an urgent recommendation stems from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the opioid epidemic in 2020 and beyond. Opioid drug overdoses rose through the pandemic, with more people dying in 2020 than any prior year (Langabeer, Yatsco, & Champagne-Langabeer, 2021; Vazquez, 2021). Preliminary findings show pandemic-induced variables such as 1) limitations in access to treatment, 2) resistant conversions to online therapy modalities, 3) social distancing with negative impacts on traditional support systems, 4) job insecurity, 5) propensities to self-medicate, and 6) increases in polysubstance abuse (i.e., alcohol) that are plaguing individuals with OUD (Kim, Morgan, & Nyhan, 2020). These initial research findings have not yet introduced the factor of immigrant status - yet these issues are present in immigrant populations and warrant an inquiry, as they will likely need to solicit dissimilar interventions.

Conclusion

The vast and rising number of immigrants in the U.S. creates an ethical imperative for rehabilitation practitioners, researchers, and educators to pay attention to how immigrant interactions with treatment and legal systems can be negatively impacted by cultural differences and how reduced access is manifested by a lack of citizenship status. The current literature does not reflect these issues, as they relate to the opioid epidemic. Inquiry into the impact of the opioid epidemic among ethnic minorities is too general. Insight is needed into unique immigrant experiences and needs, based on factors such as country of origin, as this can offer a wealth of information for OUD treatment, program development and evaluation, the education of future practitioners, and carrying out justice and advocacy.

Table 1.

Studies charted by design

| Author(s) | Bibliography Number | Title | Year | Study Design | Study Population of Focus | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bart | 9 | Ethnic differences in psychosocial factors in methadone maintenance: Hmong versus non-Hmong | 2018 | Structured and semi-structured interviews; quantitative self-assessment | Hmong immigrants | OUD Comparisons, OUD & Comorbidities, Disparate OUD Treatment, Country of Origin & OUD |

| Bart et al. | 30 | Superior methadone treatment outcome in Hmong compared with non-Hmong patients | 2012 | Retrospective chart review/Medical record review | Hmong immigrants | Disparate OUD Treatment |

| Cano, M. | 12 | Prescription opioid misuse among U.S. Hispanics | 2019 | Structured interviews | Hispanic immigrants | OUD Comparisons, Country of Origin & OUD |

| Epelbaum et al. | 24 | Immigration Trauma, Substance Abuse, and Suicide | 2010 | Case study | Brazilian immigrant | OUD & Comorbidities, Disparate OUD Treatment |

| Fleiz et al. | 29 | Opioid Crisis Along Mexico’s Northern Border: Treatment Needs Mexican Opioid Crisis | 2019 | Interviewer-administered questionnaires | Mexican immigrants | Disparate OUD Treatment |

| Gholkar | 32 | Substance Abuse in Two Generations of Indian Americans as a Function of Marginalization and Perceived Discrimination | 2007 | Web-based questionnaires | Indian immigrants | Country of Origin & OUD |

| Goddard | 31 | Psychological acculturation, contextual variables of substance related problems, and psychiatric symptoms among Latinos | 2016 | Structured interviews, Self-report measures; Longitudinal | Latino immigrants | Country of Origin & OUD |

| Guarino et al. | 21 | The social production of substance abuse and HIV/HCV risk: an exploratory study of opioid-using immigrants from the former Soviet Union living in New York City | 2012 | Semi-structured interviews | Former Soviet Union immigrants | OUD Comparisons, OUD & Comorbidities, Disparate OUD Treatment, Country of Origin & OUD |

| Guarino et al. | 13 | Opioid Use Trajectories, Injection Drug Use, and Hepatitis C Virus Risk Among Young Adult Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union Living in New York City | 2015 | Structured interviewer-administered assessments and semi-structured interviews | Former Soviet Union immigrants | OUD Comparisons, OUD & Comorbidities, Disparate OUD Treatment, Country of Origin & OUD |

| Gunn & Guarino | 22 | Not human, dead already: Perceptions and experiences of drug -related stigma among opioid-using young adults from the former Soviet Union living in the US | 2016 | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | Former Soviet Union immigrants | OUD Comparisons, Disparate OUD Treatment, Country of Origin & OUD |

| Isralowitz et al. | 14 | A Preliminary Exploration of Immigrant Substance Abusers from the Former Soviet Union Living in Israel, Germany and the United States: A Multi-National Perspective | 2002 | Exploratory and Clinical observations | Former Soviet Union immigrants | OUD Comparisons, Disparate OUD Treatment |

| Kagotho et al. | 9 | Substance Use, Service Provision, Access & Utilization among Foreign-Born Communities in the United States: A Mixed Methods Study | 2020 | Web-based surveys, in-depth interviews, and focus groups | African, Asian, Latin American, and Middle Eastern immigrants | OUD & Comorbidities, Disparate OUD Treatment, Country of Origin & OUD |

| Parker et al. | 15 | Young, American Indian or Alaskan Native, and born in the USA: at excess risk of starting extra-medical prescription pain reliever use? | 2018 | Surveys | Central and South American Indian immigrants | OUD Comparisons |

| Rodriguez Guzman | 16 | Health Professional Students as Providers of Behavioral Health Services to Uninsured Immigrants | 2017 | Surveys | Latino immigrants | OUD Comparisons |

| Salas-Wright et al. | 19 | Substance use disorders among first-and second-generation immigrant adults in the United States: evidence of an immigrant paradox? | 2014 | Structured interviews (Secondary data research) | African, European, Latin American, and Caribbean immigrants | OUD Comparisons, OUD & Comorbidities |

| Salas-Wright & Vaughn | 17 | A refugee paradox for substance use disorders? | 2014 | Surveys (Secondary data research) | Immigrants and Refugees from various regions | OUD Comparisons, OUD & Comorbidities, Country of Origin & OUD |

| Salas-Wright et al. | 18 | Substance use disorders among immigrants in the United States: A research update | 2018 | Surveys (Secondary data research) | African, Asian, European, Latin American, and Caribbean immigrants | OUD Comparisons, OUD & Comorbidities |

| Sites & Davis | 23 | Association of Length of Time Spent in the United States with Opioid Use Among First-Generation Immigrants | 2019 | Survey (Secondary data research) | Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other immigrants | OUD Comparisons |

| Wilson et al. | 20 | Association Between Opioid Prescriptions and Non-US-Born Status in the US | 2020 | Survey (Secondary data research) | Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other immigrants | OUD Comparisons |

References

- Aboii SM (2016). Undocumented immigrants and the inclusive health policies of sanctuary cities. Harvard Public Health Review, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Acheampong AB, Lasopa S, Striley CW, & Cottler LB (2016). Gender differences in the association between religion/spirituality and simultaneous polysubstance use (SPU). Journal of Religion and Health, 55(5), 1574–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adult & Teen Challenge. (2021). Freedom from addiction starts here. Adult & Teen Challenge. https://teenchallengeusa.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Akande AO (2021). Defining disability internationally: Implications for rehabilitation service provision within immigrant populations in the United States. Journal of Life Care Planning, 19(2), 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous. (2014). The twelve traditions of alcoholics anonymous. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. https://www.aa.org/assets/en_US/aa-literature/p-28-twelve-traditions-flyer [Google Scholar]

- American Immigration Council. (2017). Sanctuary policies: An overview. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/sanctuary-policies-overview [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, & O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azar KMJ, Shen Z, Romanelli RJ, Lockhart SH, Smits K, Robinson S, Brown S, & Pressman AR (2020). Disparities in outcomes among COVID-19 patients in a large health care system in California. Health Affairs, 39(7), 1253–12. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bart G. (2018). Ethnic differences in psychosocial factors in methadone maintenance: Hmong versus non-Hmong. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 17(2), 108–122. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2017.1371656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bart G, Wang Q, Hodges JS, Nolan C, & Carlson G. (2012). Superior methadone treatment outcome in Hmong compared with non-Hmong patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 43(3), 269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiman A. (2020, August 20). Key findings about U.S. immigrants. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/ [Google Scholar]

- Cano M. (2019). Prescription opioid misuse among U.S. Hispanics. Addictive Behaviors, 98, 106021, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, March 16). Opioid basics: CDC’s response to the opioid overdose epidemic. https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/basics/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Berkley-Patton J, Bauer A, Thompson CB, & Burgin T. (2020). Risk factors associated with opioid use among African American faith-based populations. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 13(4), 18–31. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp/vol13/iss4/3 [Google Scholar]

- Connery HS (2015). Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harvard review of psychiatry, 23(2), 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration. (2021). 2020 National drug threat assessment. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/DIR-008-21%202020%20National%20Drug%20Threat%20Assessment_WEB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Epelbaum C, Taylor ER, & Dekleva K. (2010). Immigration trauma, substance abuse, and suicide. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 18(5), 304–313. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2010.511061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiz C, Villatoro J, Dominguez M, Bustos M, & Medina-Mora ME (2019). Opioid crisis along Mexico’s northern border: Treatment needs Mexican opioid crisis. Archives of Medical Research, 50(8), 527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2019.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia S. (2018, October 15). What happens to immigrants who face addiction? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/samuelgarcia/2018/10/15/what-happens-to-immigrants-who-face-addiction/ [Google Scholar]

- García-Muñoz T, & Neuman S. (2012). Is religiosity of immigrants a bridge or a buffer in the process of integration? A comparative study of Europe and the United States (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2019436). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2019436 [Google Scholar]

- Gholkar RV (2006). Substance abuse in two generations of Indian-Americans as a function of marginalization and perceived discrimination (Master’s thesis). Available from Proquest database. (1446179) [Google Scholar]

- Goddard A. (2016). Psychological acculturation, contextual variables of substance related problems, and psychiatric symptoms among Latinos (Doctoral dissertation). Available from Proquest database. (10181700) [Google Scholar]

- Greenaway C, Hargreaves S, Barkati S, Coyle CM, Gobbi F, Veizis A, & Douglas P. (2020). COVID-19: Exposing and addressing health disparities among ethnic minorities and migrants. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(7). doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grim BJ, & Grim ME (2019). Belief, behavior, and belonging: How faith is indispensable in preventing and recovering from substance abuse. Journal of Religion and Health, 58(5), 1713–1750. doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00876-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino H, Marsch LA, Deren S, Straussner SLA, & Teper A. (2015). Opioid use trajectories, injection drug use, and hepatitis C virus risk among young adult immigrants from the former Soviet Union living in New York City. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 34(2–3), 162–177. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2015.1059711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino H, Moore SK, Marsch LA, & Florio S. (2012). The social production of substance abuse and HIV/HCV risk: An exploratory study of opioid-using immigrants from the former Soviet Union living in New York City. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 7(1), 2. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-7-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn A, & Guarino H. (2016). “Not human, dead already”: Perceptions and experiences of drug-related stigma among opioid-using young adults from the former Soviet Union living in the U.S. International Journal of Drug Policy, 38, 63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock C, Mennenga H, King N, Andrilla H, Larson E, & Schou P. (2017). Treating the rural opioid epidemic. National Rural Health Association. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K. (2017). Avoiding globalisation of the prescription opioid epidemic. The Lancet, 390(10093), 437–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobucci G. (2020). Covid-19: Racism may be linked to ethnic minorities’ raised death risk, says PHE. BMJ, 369, m2421. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isralowitz R, Straussner SLA, Vogt I, & Chtenguelov V. (2002). A preliminary exploration of immigrant substance abusers from the former Soviet Union living in Israel, Germany, and the United States: A multi-national perspective. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 2(3–4), 119–136. doi: 10.1300/J160v02n03_08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kagotho N, Maleku A, Baaklini V, Karandikar S, & Mengo C. (2020). Substance use, service provision, access & utilization among foreign-born communities in the United States: A mixed methods study. Substance Use & Misuse, 55(12), 2043–2054. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2020.1790006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Morgan E, & Nyhan B. (2020). Treatment versus punishment: Understanding racial inequalities in drug policy. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(2), 177–209. doi: 10.1215/03616878-8004850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langabeer JR, Yatsco A, & Champagne-Langabeer T. (2021). Telehealth sustains patient engagement in OUD treatment during COVID-19. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 122, 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold KM, Jones CM, O’Malley Olsen E, & Giroir BP (2019). Racial/ethnic and age group differences in opioid and synthetic opioid–involved overdose deaths among adults aged ≥18 years in metropolitan areas—United States, 2015–2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(43), 967–973. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6843a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak HW (2019). Dimensions of religiosity: The effects of attendance at religious services and religious faith on discontinuity in substance use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(3), 358–365. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, & Higgins ME (2011). The effect of immigration on religious belief and practice: A theologizing or alienating experience? Social Science Research, 40(5), 1371–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie V, & Satcher D. (2021, September 20). Bridging faith and science to combat the overdose crisis: Focus on policy. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k8-LPmM7j7I [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA, Lopez-Quintero C, & Anthony JC (2018). Young, American Indian or Alaskan Native, and born in the USA: At excess risk of starting extra-medical prescription pain reliever use? PeerJ, 6, e5713. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones S. (2016). Dreamland: The true tale of America’s opiate epidemic. New York: Bloomsbury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Guzman J. (2017). Health professional students as providers of behavioral health services to uninsured immigrants (Doctoral thesis). https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/2166 [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, & Vaughn MG (2014). A “refugee paradox” for substance use disorders? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 142, 345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Clark Goings TT, Córdova D, & Schwartz SJ (2018). Substance use disorders among immigrants in the United States: A research update. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Clark TT, Terzis LD, & Córdova D. (2014). Substance use disorders among first- and second-generation immigrant adults in the United States: Evidence of an immigrant paradox? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(6), 958–967. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M, Dillon F, Ruffin B, & De La Rosa M. (2012). The influence of religious coping on the acculturative stress of recent Latino immigrants. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 21(3), 171–194. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2012.700443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schranz AJ, Barrett J, Hurt CB, Malvestutto C, & Miller WC (2018). Challenges facing a rural opioid epidemic: treatment and prevention of HIV and hepatitis C. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 15(3), 245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sites BD, & Davis MA (2019). Association of length of time spent in the United States with opioid use among first-generation immigrants. JAMA Network Open, 2(10), e1913979. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: (2020). The opioid crisis and the Hispanic/Latino population: An urgent issue (pp. PEP20–05-02–002). https://store.samhsa.gov/product/The-Opioid-Crisis-and-the-Hispanic-Latino-Population-An-Urgent-Issue/PEP20-05-02-002 [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2018, May 8). Opioid crisis statistics. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/opioid-crisis-statistics/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn JM (2018). The effect of sanctuary city policies on the ability to combat the opioid epidemic. Center for Immigration Studies. https://cis.org/Testimony/Effect-Sanctuary-City-Policies-Ability-Combat-Opioid-Epidemic [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez M. (2021, September 30). Biden administration grapples with American addiction as overdose deaths hit a record high. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/09/30/politics/biden-administration-drug-epidemic/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Wilson FA, Mosalpuria K, & Stimpson JP (2020). Association between opioid prescriptions and non–US-born status in the US. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e206745. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]