Abstract

Background and study aims Despite the widespread use of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided tissue acquisition, the choice of optimal suction technique remains a subject of debate. Multiple studies have shown conflicting results with respect to the four suction techniques: Dry suction (DS), no suction (NS), stylet slow-pull (SSP) and wet suction (WS). Thus, the present network meta-analysis (NMA) was conducted to compare the diagnostic yields of above suction techniques during EUS-guided tissue acquisition.

Methods A comprehensive literature search from 2010 to March 2022 was done for randomized trials comparing the aspirated sample and diagnostic outcome with various suction techniques. Both pairwise and network meta-analyses were performed to analyze the outcomes: sample adequacy, moderate to high cellularity, gross bloodiness and diagnostic accuracy.

Results A total of 16 studies (n=2048 patients) were included in the final NMA. WS was associated with a lower odd of gross bloodiness compared to DS (odds ratio 0.50, 95% confidence interval 0.24–0.97). There was no significant difference between the various suction methods with respect to sample adequacy, moderate to high cellularity and diagnostic accuracy. On meta-regression, to adjust for the effect of needle type, WS was comparable to DS in terms of bloodiness when adjusted for fine-needle aspiration needle. Surface under the cumulative ranking analysis ranked WS as the best modality for all the outcomes.

Conclusions The present NMA did not show superiority of any specific suction technique for EUS-guided tissue sampling with regard to sample quality or diagnostic accuracy, with low confidence in estimates.

Introduction

The introduction of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided tissue acquisition represents an important breakthrough in the field of endoscopy and has become an integral part of the diagnostic and staging algorithms of various diseases of gastrointestinal tract 1 . Traditionally, EUS-guided tissue sampling was performed with a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) needle. However, the efficacy of EUS-FNA depends on multiple factors including the characteristics of the target tissue 2 and the availability of an on-site cytopathologist 3 . To overcome these limitations of FNA needles, fine-needle biopsy (FNB) needles were designed that allow sampling of core tissue from the target lesion.

Apart from needle type, the proper suction techniques may impact outcomes of EUS-guided tissue acquisition. Various suction techniques used in tissue acquisition during EUS include no suction (NS), dry suction (DS), stylet slow-pull (SSP), and wet suction (WS). In the DS technique, a 10 ml pre-vacuum syringe is used after removal of stylet, to generate a negative pressure for tissue acquisition. This improves the cellularity of the sample but at the cost of blood contamination 4 . The SSP technique involves slow removal of the stylet during sampling to generate negative pressure within needle, which is usually 5% of the force generated with standard suction 5 . Lastly, the WS technique involves preflushing the needle with saline or heparin prior to aspiration. Once the lesion has been punctured, a syringe prefilled with saline is left attached to the proximal port and used later for aspiration 6 .

In a recent meta-analysis 7 , WS technique has been reported to have a higher cellularity compared to DS technique, but comparable blood contamination and histological accuracy. With respect to DS versus SSP, two meta-analyses have shown conflicting results 8 9 . In lieu of the heterogeneity of outcome from studies comparing the various methods and dilemma regarding the optimal method of tissue acquisition during EUS, we conducted a systemic review, pairwise meta-analysis and network meta-analysis (NMA) to compare the various suction methods (NS, DS, WS, SSP) for EUS-guided tissue acquisition.

Methods

The present systematic review and network meta-analysis is reported as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses for Network Meta Analyses (PRISMA NMA) guidelines 10 and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022321181).

Information sources and search strategy

MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Science Direct were searched from 2010 to March 2022 for all relevant studies. A search was made using the keywords: (EUS OR FNA OR FNB OR "Endoscopic ultrasound" OR "Fine needle aspiration" OR "Fine needle biopsy") AND (Suction OR Stylet OR Wet OR "Slow-pull" OR "Heparin"). In addition, the reference lists of all identified trials, guidelines, and reviews on the topic were searched for relevant trials.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts of the retrieved search records were independently screened by two reviewers for inclusion and exclusion criteria, followed by full text examination of potential eligible citations. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion. Studies included in this NMA were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) fulfilling the following PICO criteria: 1) Patients-EUS-guided tissue acquisition of solid lesions including pancreatic lesion, lymph nodes and submucosal lesions; 2) Intervention-four suction techniques which include DS, WS, SSP and NS; 3) Comparison-Other suction techniques; and 3) Outcomes-adequacy of sample, moderate to high cellularity, gross bloodiness and diagnostic accuracy. Due to non-standardization of evaluation of blood contamination and cellularity, outcome variables were defined according to the original protocol of each study. Single-arm studies, studies with sample size <10, conference abstracts and studies involving persons <18 years of age were excluded from the analysis.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two investigators, and discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Data collection was done under the following headings: study author and year, country, type of study, number of patients, types of intervention, outcomes, and adverse events.

Risk of bias in individual studies and confidence in cumulative evidence

The risk of bias was assessed by two independent reviewers using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2). The assessment of the certainty of the evidence for all evaluable outcomes, was done using the Confidence in Network Meta Analysis (CINeMA) web application and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for NMA.

Statistical analysis

Pairwise meta-analysis was performed using a random effect model in RevMan software (version 5.4.1, Cochrane Collaboration). Dichotomous variables were analyzed using the risk ratio and Mantel-Haenszel test. Network meta-analysis was performed using Stata 17.0 software package (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas, United States) and MetaInsight [Complex Review Support Unit (CRSU) network meta-analysis (NMA) web-based app] using a Bayesian random effect model. The comparative efficacy of any two treatments was modeled as a function of each treatment relative to the reference treatment (DS in this study, as it is the most common method used). Treatment estimates were calculated as odds ratios (ORs) for binary outcomes, along with their 95% confidence interval (CI). The pooled ORs from the NMA were compared with corresponding ORs from a pairwise meta-analysis of direct comparisons to assess the inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons. Wald test was performed to assess for global inconsistency. Relative ranking of interventions for various outcomes was calculated as their surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA). Publication bias was assessed by examining the funnel plot asymmetry. The certainty or quality of evidence was evaluated based on the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) framework, which is the most widely adopted tool for grading the quality of evidence and for making recommendations.

Results

Study characteristics and risk of bias within studies

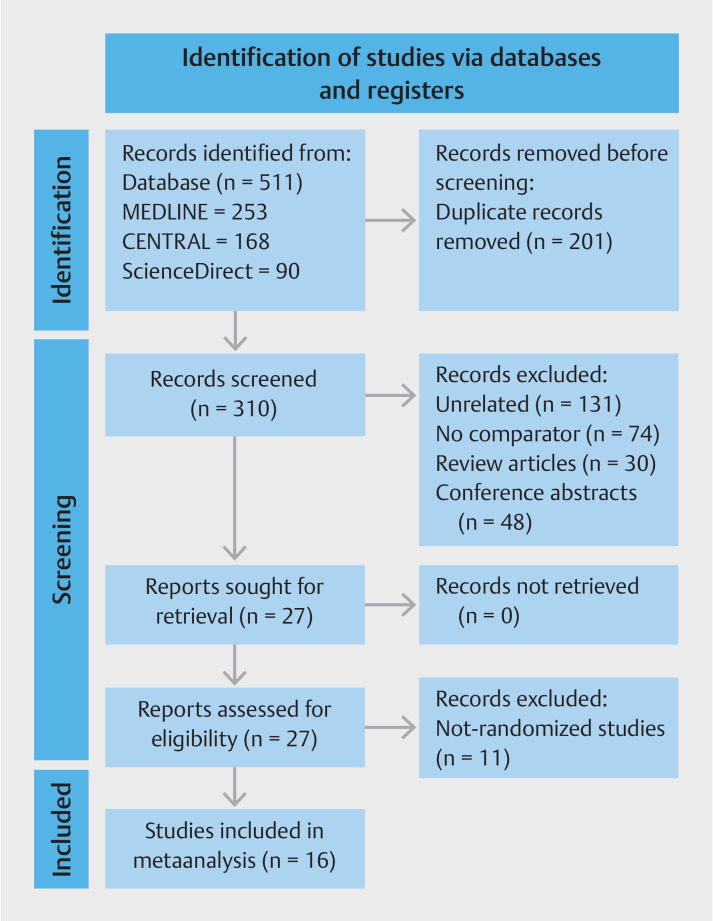

A total of 511 studies were identified from various databases and manual reference searching. After removal of duplicate studies, 310 studies were screened out of which 27 were assessed for eligibility. Finally, 16 RCTs 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 with 2048 patients were included in the meta-analysis. Fig. 1 shows the PRISMA diagram for study selection. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. Eight studies were crossover studies 11 15 17 19 20 21 22 23 while the rest eight were parallel studies 12 13 14 16 18 24 25 26 . Majority of the studies 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 22 24 25 26 included pancreatic lesions only, while 4 studies included extrapancreatic lesion including lymph nodes and subepithelial lesions 11 12 21 23 . FNA needle was used in nine studies 11 12 13 14 16 17 21 23 26 among which seven studies used 22G needles 11 13 16 17 21 23 26 and two studies used other size needles 12 14 . Seven studies used FNB needle 15 18 19 20 22 24 25 , among which only one study used 20G needles 18 and the rest used 22G needles. ROSE was available in only four studies 11 14 16 24 . The number of needle passes was two in the majority of the studies 11 12 15 17 19 20 21 23 . Six studies 15 16 20 23 24 25 had moderate risk of bias while 10 studies had low risk of bias 11 12 13 14 17 18 19 21 22 26 ( Supplementary Fig. 1 ). The definitions of various outcomes used in the included studies in shown in Supplementary Table 1 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart for study selection and inclusion process. From: Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015; 162: 777–784.

Table 1 Characteristics of included randomized controlled trials.

| Authors | Country | Study design | Total no. patients | Male/female | Mean age | Location of lesion | Needle used | ROSE | No. passes | Suction technique | No. patients in each arm |

| L/LN/P//O/SM, liver/lymph node/pancreatic mass/others/submucosal lesion; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; FNB, fine-needle biopsy; DS/NS/SSP/WS, dry suction/no suction/slow stylet pull/wet suction | |||||||||||

| Attam 2015 11 | USA, Multicentric | Crossover | 117 | 66/51 | 60.5±11.9 | P63/LN35/L10/O9 | 22-G FNA | Yes | 2 | WS | 117 |

| DS | 117 | ||||||||||

| Bansal 2017 12 | India, Single-center | Parallel | 300 | 195/105 | 52±14 | P65/LN235 | 19-G/22-G/25-G FNA | No | 2 | WS | 100 |

| DS | 100 | ||||||||||

| NS | 100 | ||||||||||

| Weston 2017 13 | USA, Multicentric | Parallel | 60 | 35/25 | - | P60 | 22-G FNA | No | 3 | SSP | 30 |

| DS | 30 | ||||||||||

| Bang 2018 14 | USA, Single-center | Parallel | 352 | 191/161 | 68.3±12.4 | P352 | 22-G/25-G FNA | Yes | 2–8 | DS | 176 |

| NS | 176 | ||||||||||

| Lee 2018 15 | Korea, Multicentric | Crossover | 50 | 27/23 | 66.8±12.6 | P50 | 22-G FNB | No | 2 | SSP | 50 |

| DS | 50 | ||||||||||

| NS | 50 | ||||||||||

| Saxena 2018 16 | USA, Multicentric | Parallel | 121 | 70/51 | 64±13.8 | P121 | 22-G FNA | Yes | 1 | SSP | 61 |

| DS | 60 | ||||||||||

| Cheng 2019 17 | Brazil, Multicentric | Crossover | 50 | 29/21 | 63.9±10.4 | P50 | 22-G FNA | No | 2 | DS | 50 |

| SSP | 50 | ||||||||||

| Di Mitri 2019 18 | Italy, Multicentric | Parallel | 110 | 49/61 | 70.8±10.4 | P110 | 20-G FNB | No | 2–3 | DS | 55 |

| SSP | 55 | ||||||||||

| Moreira 2020 19 | Portugal, Single-center | Crossover | 50 | 23/27 | 65.5±11.8 | P50 | 22-G FNB | No | 2 | DS | 50 |

| NS | 50 | ||||||||||

| Tong 2020 20 | China, Multicentric | Crossover | 50 | 34/16 | 58.6±13.7 | P50 | 22-G FNB | No | 2 | WS | 50 |

| DS | 50 | ||||||||||

| Wang 2020 21 | China, Multicentric | Crossover | 269 | 161/108 | 57.5±11.1 | P161/LN108 | 22-G FNA | No | 2 | DS | 269 |

| WS | 269 | ||||||||||

| Bang 2020 22 | USA, Single-center | Crossover | 129 | 68/61 | 68.4±12.4 | P129 | 22-G FNB | No | 1 | NS | 129 |

| SSP | 129 | ||||||||||

| DS | 129 | ||||||||||

| Takasumi 2021 23 | Japan, Single-center | Crossover | 26 | 16/10 | 63.6±16.1 | SM26 | 22-G FNA | No | 2 | DS | 26 |

| WS | 26 | ||||||||||

| Ladd 2021 24 | USA, Multicentric | Parallel | 55 | 32/23 | 66.1±12.6 | P55 | 22-G FNB | Yes | 2–3 | DS | 20 |

| WS | 17 | ||||||||||

| SSP | 18 | ||||||||||

| Zhou 2021 25 | China | Parallel | 116 | 78/38 | 58.9±9.7 | P116 | 22-G FNB | No | 1–5 | DS | 60 |

| SSP | 56 | ||||||||||

| Paik 2021 26 | Korea, Multicentric | Parallel | 193 | – | 59.8±12.7 | P193 | 22-G FNA | No | 3 | DS | 94 |

| NS | 99 | ||||||||||

Direct meta-analysis

Dry suction vs. no suction

Five studies 12 14 15 19 26 reported data on DS vs. NS. DS was associated with better cellularity (4 RCTs; OR=1.42, 95%CI [1.02–2.00]; I 2 =0.0%, P =0.81), but at the cost of higher risk of gross bloodiness (4 RCTs; OR=1.92, 95%CI [1.31–2.81]; I 2 =0.0%, P =0.82). There was no difference between DS and NS with respect to sample adequacy (4 RCTs; OR=1.49, 95%CI [0.53–4.18[; I 2 =87%, P =0.000) or diagnostic accuracy (2 RCTs; OR=0.96, 95%CI [0.63–1.45]; I 2 =0.0%, P =0.37). There was no difference in subgroups based on the location of lesion ( Supplementary Fig. 2a ), but on subgroup analysis based on needle type, DS was associated with a higher sample adequacy with the use of FNB needle ( Supplementary Fig. 2b ).

Dry suction vs. wet suction

Six studies 11 12 20 21 23 24 compared the outcomes of DS vs. WS. There was no difference between DS and WS for sample adequacy (6 RCTs; OR=0.60, 95%CI [0.27–1.34]; I 2 =72%, P =0.003), gross bloodiness (5 RCTs; OR=1.93, 95%CI [0.85–4.36]; I 2 =69%, P =0.01), moderate to highly cellular sample (6 RCTs; OR=0.67, 95%CI [0.28–1.58]; I 2 =81%, P =0.000), and diagnostic accuracy (3 RCTs; OR=0.76, 95%CI [0.50–1.16]; I 2 =0.0%, P =0.92). There was no difference in subgroups based on either the location of lesion ( Supplementary Fig. 3a ) or the type of the needle used ( Supplementary Fig. 3b ).

Dry suction vs. stylet slow-pull

Seven studies 13 15 16 17 22 24 25 reported data comparing DS vs. SSP. No significant difference was observed between the two groups with respect to sample adequacy (5 RCTs; OR=0.95, 95%CI [0.45–1.99]; I 2 =44%, P =0.13), gross bloodiness (2 RCTs; OR=1.19, 95%CI [0.32–4.45]; I 2 =0.0%, P =0.56), moderate to highly cellular sample (5 RCTs; OR=0.88, 95%CI [0.38–2.05]; I 2 =70%, P =0.009), and diagnostic accuracy (4 RCTs; OR=1.11, 95%CI [0.57–2.16]; I 2 =21%, P =0.28) ( Supplementary Fig. 4 ). There was no difference in subgroups based on the type of the needle used.

Network meta-analysis

Adequacy of sample

Thirteen studies 11 12 13 14 15 16 19 20 21 23 24 25 26 reported data on sample adequacy from four interventions. There was no difference between the various modalities on network estimate ( Supplementary Table 2 ). Meta-regression was conducted taking the needle type into account as there was significant difference between FNA and FNB on pairwise meta-analysis. On meta-regression, there was no significant difference in ORs of adequacy when adjusted for either of the needle types ( Supplementary Fig. 5 ). As the direct meta-analysis did not show any significant difference based on location of the lesion on subgroup analysis, meta-regression was not performed taking lesion location into consideration.

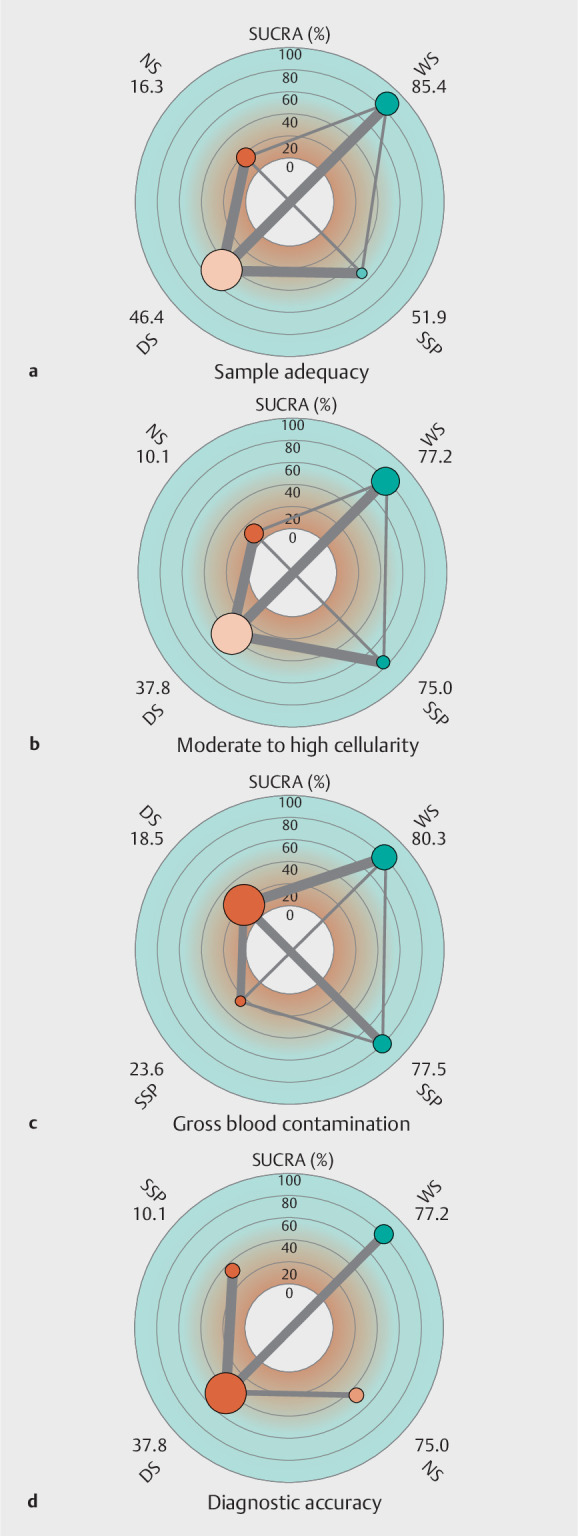

A SUCRA plot was generated from the ranking plot. Ranking based on SUCRAs accounts better for the uncertainty in the estimated treatment effects. WS was ranked first (SUCRA 85.4) with the maximum probability of obtaining an adequate sample followed by SSP (SUCRA 51.9), DS (SUCRA 46.4) and NS (SUCRA 16.3) ( Fig. 2 a ). The certainty of evidence for the SUCRA ranking was moderate.

Fig. 2.

Radial surface under the cumulative ranking analysis (SUCRA) and network plot for all the outcomes. a Sample adequacy. b Moderate to high cellularity. c Gross blood contamination. d Diagnostic accuracy. The number beside the suction techniques indicate SUCRA values. DS, dry suction; NS, no suction; SSP, slow stylet pull; WS, wet suction.

Moderate to high cellularity

Eleven studies 11 12 13 15 17 19 21 22 23 24 25 reported on the outcome of moderate to high cellularity. On network estimate, there was no significant difference between the studies with respect to moderate to high cellularity of sample ( Supplementary Table 3 ). On meta-regression, there was no significant difference in ORs of cellularity when adjusted for either of the needle types ( Supplementary Fig. 6 ).

On SUCRA analysis, WS was ranked first (SUCRA 77.2) with the maximum probability of obtaining a moderate to highly cellular sample followed by SSP (SUCRA 75.0), DS (SUCRA 37.8) and NS (SUCRA 10.1) ( Fig. 2 b). The certainty of evidence for the SUCRA ranking was moderate.

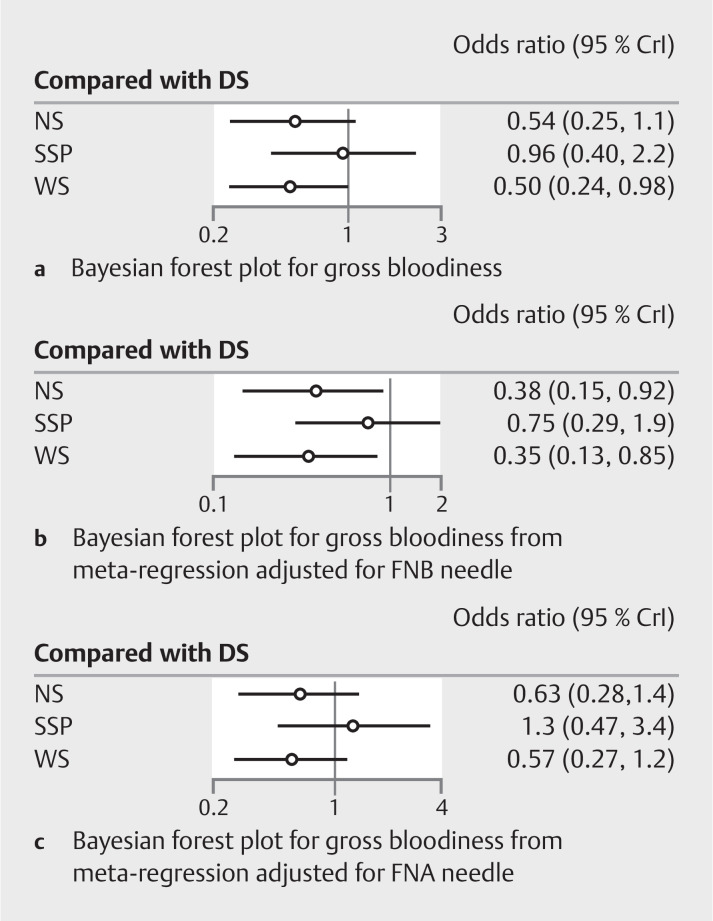

Gross bloodiness

Ten studies 11 12 14 15 17 18 19 20 21 24 reported data on gross bloodiness of sample from four interventions. On network estimate, only WS had a significantly lower odds of gross bloodiness compared to DS (OR=0.50, 95%CI [0.24–0.97]) ( Supplementary Table 4 ). Meta-regression was performed to study the effect of type of needle on bloodiness of sample. When adjusted for the effect of FNB needle, both WS (OR=0.35, 95%CI [0.13–0.85]) and NS (OR=0.38, 95%CI [0.15–0.92]) were better than DS with respect to gross bloodiness. However, on adjusting for FNA needle, there was no difference between the interventions on network estimates ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Bayesian Forest plot for diagnostic accuracy. a Unadjusted. b Adjusted for the effect of FNB needle. c Adjusted for effect of FNA needle.

On SUCRA analysis, WS was ranked first (SUCRA 80.3) with the maximum probability of obtaining an adequate sample followed by NS (SUCRA 77.5), SSP (SUCRA 23.6) and DS (SUCRA 18.5) ( Fig. 2 c ). The certainty of evidence for the SUCRA ranking was moderate.

Diagnostic accuracy

Nine studies 14 15 17 18 19 20 21 23 25 reported data on diagnostic accuracy of sample from four interventions. On network estimate, there was no significant difference between the studies with respect to diagnostic accuracy ( Supplementary Table 5 ). Meta-regression did not show any significant difference in ORs of adequacy when adjusted for either of the needle types ( Supplementary Fig. 7 ). On SUCRA analysis, WS was ranked first (SUCRA 80.2) with the maximum probability of diagnostic accuracy followed by NS (SUCRA 45.0), DS (SUCRA 41.6) and SSP (SUCRA 33.1) ( Fig. 2 d ). The certainty of the evidence for the SUCRA ranking was low.

Publication bias, network coherence, sensitivity analysis and quality of evidence

There was no evidence of publication bias, which was assessed qualitatively based on the symmetry in the funnel plot for all the studies reporting various outcomes ( Supplementary Fig. 8 ). The global Wald test for diagnostic accuracy yielded a chi 2 (0)=0.00, and the P value could not be calculated, indicating incoherence or significant heterogeneity. There was no evidence of network coherence for the other outcomes ( Supplementary Table 6 ). Sensitivity analysis was conducted with exclusion of studies including non-pancreatic lesions and exclusion of studies with available ROSE ( Table 2 ) which did not show any change compared to overall analysis. The summary of findings for treatment comparisons with quality of evidence based on the GRADE framework is shown in Supplementary Table 7 .

Table 2 Summary of findings with sensitivity analysis.

| Techniques and outcomes | Odds ratio for overall analysis | Analysis of only pancreatic lesion | Exclusion of studies with ROSE |

| DS/NS/SSP/WS, dry suction/no suction/slow stylet pull/wet suction. The table shows odds of an outcome with the first suction technique mentioned in each row compared to the second technique. | |||

| Sample adequacy | |||

| DS vs. NS | 1.45 (0.60–3.52) | 1.00 (0.51–2.07) | 1.65 (0.49–5.33) |

| DS vs. SSP | 0.94 (0.36–2.51) | 1.11 (0.56–2.28) | 1.01 (0.23–4.39) |

| DS vs. WS | 0.62 (0.26–1.49) | 0.75 (0.15–3.72) | 0.65 (0.18–2.36) |

| NS vs. SSP | 0.64 (0.19–2.24) | 1.11 (0.42–2.97) | 1.64 (0.29–9.02) |

| NS vs. WS | 0.42 (0.13–1.37) | 0.73 (0.13–4.26) | 0.39 (0.08–2.00) |

| SSP vs. WS | 0.66 (0.19–2.25) | 0.66 (0.12–3.81) | 0.64 (0.09–4.47) |

| Moderate to high cellularity | |||

| DS vs. NS | 1.47 (0.63–3.52) | 1.68 (0.61–4.56) | 1.44 (0.58–3.55) |

| DS vs. SSP | 0.68 (0.33–1.72) | 0.69 (0.30–1.69) | 0.67 (0.26–1.79) |

| DS vs. WS | 0.65 (0.35–1.29) | 0.76 (0.15–3.68) | 0.59 (0.22–1.61) |

| NS vs. SSP | 0.46 (0.17–1.29) | 0.41 (0.14–1.31) | 0.47 (0.15–1.45) |

| NS vs. WS | 0.44 (0.16–1.33) | 0.45 (0.07–2.86) | 0.41 (0.12–1.41) |

| SSP vs. WS | 0.97 (0.33–2.91) | 1.10 (0.20–5.68) | 0.89 (0.22–3.37) |

| Gross bloodiness | |||

| DS vs. NS | 1.85 (0.95–3.99) | 1.91 (1.00–4.23) | 2.06 (0.97–4.83) |

| DS vs. SSP | 1.04 (0.53–2.03) | 1.02 (0.50–2.11) | 0.99 (0.43–2.18) |

| DS vs. WS | 2.00 (1.03–4.14) | 3.05 (0.96–9.35) | 2.88 (1.33–6.13) |

| NS vs. SSP | 0.56 (0.19–1.61) | 0.53 (0.19–1.34) | 0.48 (0.15–1.34) |

| NS vs. WS | 1.08 (0.42–2.69) | 1.59 (0.37–5.76) | 1.39 (0.48–3.56) |

| SSP vs. WS | 1.92 (0.65–5.77) | 3.00 (0.77–10.83) | 2.91 (0.96–8.90) |

| Diagnostic accuracy | |||

| DS vs. NS | 0.99 (0.52–1.98) | 1.00 (0.51–2.07) | 1.40 (0.45–4.29) |

| DS vs. SSP | 1.09 (0.57–2.19) | 1.11 (0.56–2.28) | 1.75 (0.73–4.23) |

| DS vs. WS | 0.74 (0.37–1.43) | 0.75 (0.15–3.72) | 0.74 (0.38–1.42) |

| NS vs. SSP | 1.10 (0.43–2.80) | 1.11 (0.42–2.97) | 1.24 (0.30–5.36) |

| NS vs. WS | 0.74 (0.28–1.85) | 0.73 (0.13–4.26) | 0.53 (0.15–1.93) |

| SSP vs. WS | 0.67 (0.25–1.67) | 0.66 (0.12–3.81) | 0.43 (0.14–1.26) |

Discussion

EUS-guided tissue acquisition plays an essential role in diagnosing pathology related to pancreatic masses and lymph nodes. Multiple suction techniques have been evaluated to improve diagnostic adequacy and accuracy, which will, in turn, improve patient outcomes. The present NMA showed no significant difference between the suction methods concerning sample adequacy, moderate to high cellularity, and diagnostic accuracy. WS was better compared to DS, with a lower odd of bloodiness. But this difference was not significant when adjusting for the effect of the FNA needle on the outcome, thus indicating a similar rate of gross blood contamination with various suction techniques when using an FNB needle. Based on SUCRA, WS was ranked as the best suction method for all the study outcomes.

A previous meta-analysis by Nakai et al. 8 reported that SSP was likely to provide lower blood contamination but similar cellularity and diagnostic accuracy compared to DS. However, randomized trials, studies using 25G needle and studies involving pancreatic lesions showed higher diagnostic accuracy with SSP than DS on sensitivity analysis. Capurso et al. 9 analyzed only RCTs and showed that SSP had similar adequacy and diagnostic accuracy but a lower rate of blood contamination compared to DS. The present meta-analysis did not show any significant difference between SSP and DS in pairwise and NMA. This indicates the non-superiority of SSP over DS, although SSP may result in reduced blood contamination. It may be because the force used in the aspiration may have led to a higher amount of blood contamination with DS.

Ramai et al. 7 conducted a meta-analysis comparing WS and DS and showed higher specimen adequacy with WS (OR=3.18, 95%CI: [1.82–5.54]) but similar blood contamination and diagnostic accuracy between the two methods. This is explained by the fact that a water column enhances tissue aspiration due to fluid dynamics and allows greater volumes of tissue to be aspirated within a given simulation time compared to a column of air 27 . The current NMA showed a lower risk of blood contamination with WS than with DS. It is possible that the presence of the saline solution eliminates the “empty space” in the needle lumen for the red blood cells to flow into, and thereby reduces the degree of bloodiness 11 . However, this superiority of WS is not seen on adjusting for the impact of the FNA needle. Thus, using either of the techniques with an FNB needle may not lead to a difference in the rate of blood contamination.

While WS was ranked first for accuracy based on SUCRA, a statistically significant difference was not seen in different suction techniques. A variation in the definition of outcomes and needle gauge could explain this finding. Compared to the 19G or 22G needle, the 25G needle has high flexibility and a smaller diameter, making it easier to handle 28 . Other studies have reported that a 20G ProCore needle has better diagnostic accuracy and histological yield than a 25G needle 29 30 . European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy recommends using a 22-G or 25-G needle due to unreliable results with other needles 31 . In their recent NMA, Han et al. concluded that FNB needles, particularly 22-G, offer the highest diagnostic performance compared to FNA needles in sampling pancreatic masses 32 . However, in another NMA, Facciorusso et al. 33 showed no difference in the diagnostic performance based on needle type (FNA vs. FNB) or gauge (19G vs. 22G vs. 25G) for solid pancreatic lesions. Findings remained similar in sensitivity analysis based on the availability of ROSE and the use of the fanning technique.

In a recent NMA on the diagnostic performance of end-cutting FNB needles 34 , Franseen needles and fork-tip needles outperformed reverse-bevel needles and FNA needle for both sample adequacy and diagnostic accuracy. However, comparing FNB needle size, 25G Franseen and 25G Fork-tip needles were not superior to 22G reverse-bevel needles. Also, none of the FNB needles were superior when ROSE was available. Thus, multiple factors can affect the final adequacy and accuracy of a sample obtained via EUS-guided sampling.

The study's main strength is that we used NMA with rigorous methodology to analyze various RCTs and previous meta-analyses, which included all types of suction methods used during EUS tissue acquisition. Because we included only RCTs, we are able to satisfy the condition of transitivity needed for NMA. Also, considering the various sampling techniques practiced and two previous meta-analyses have shown conflicting results with respect to DS versus SSP, this NMA helps clarify the choice for endoscopists.

There were a few limitations to the study, most of them inherent in any meta-analysis and that warrant further discussion. First, the definitions of "blood contamination" and "cellularity" were not uniform in all the studies. Hence, the results need to be interpreted with caution. Second, the effect of the number of passes used during EUS-guided tissue acquisition could not be analyzed, which may affect the sensitivity of the tissue acquisition. Zhou et al. 25 demonstrated a significant increase in diagnostic accuracy with an increase in the number of passes. After three passes with DS and four passes with SSP, there was no further increase in diagnostic accuracy. However, most of the included studies in this analysis used two passes which may have led to a suboptimal outcome. Third, there was variation in the study design with half being crossover and half being parallel. While the type of estimates was the same, they were derived using different techniques, and especially the estimates of standard error were different. Fourth, there was a slight difference in the size and type of the needle used. Among FNB needles, Franseen needles and Fork-tip needles have been shown to be superior to reverse-bevel needles and FNA needles for both sample adequacy and diagnostic accuracy 34 . This difference in needle type may contribute to the heterogeneity of outcomes. Fifth, all studies did not describe whether they used the fanning technique or not. Sixth, the location of lesions (solid pancreatic lesions, submucosal lesions, or lymph nodes) may dictate the type of suction needed. Lastly, there was significant heterogeneity in the NMA for the outcome of diagnostic accuracy.

Conclusions

To conclude, WS was associated with lower odds of bloodiness than DS and was ranked as the best method for all the outcomes. However, there was a lack of sufficient literature evidence to prove the unequivocal superiority of one suction technique over the other during EUS-guided tissue acquisition. There is a need for development of standard reporting guidelines for samples obtained using EUS. As the practice of EUS-guided tissue acquisition has shifted toward increasing the use of FNB needles, there is a need to study the effect of various suction techniques on tissue adequacy and diagnostic accuracy using newer generation end-cutting needles.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Cazacu IM, Chavez AA, Saftoiu A et al. A quarter century of EUS-FNA: Progress, milestones, and future directions. Endosc ultrasound. 2018;7:141. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_19_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ieni A, Todaro P, Crino SF et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology in pancreaticobiliary carcinomas: diagnostic efficacy of cell-block immunocytochemistry. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2015;14:305–312. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(15)60367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song TJ, Kim JH, Lee SS et al. The prospective randomized, controlled trial of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration using 22G and 19G aspiration needles for solid pancreatic or peripancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1739–1745. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace MB, Kennedy T, Durkalski V et al. Randomized controlled trial of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration techniques for the detection of malignant lymphadenopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:441–447. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.117764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katanuma A, Itoi T, Baron TH et al. Bench top testing of suction forces generated through endoscopic ultrasound guided aspiration needles. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:379–385. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villa NA, Berzosa M, Wallace MB et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: The wet suction technique. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:17. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.175877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramai D, Singh J, Kani T et al. Wet- versus dry-suction techniques for EUS-FNA of solid lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2021;10:319–324. doi: 10.4103/EUS-D-20-00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakai Y, Hamada T, Hakuta R et al. A meta-analysis of slow-pull versus suction for endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition. Gut Liver. 2021;15:625–633. doi: 10.5009/gnl20270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capurso G, Archibugi L, Petrone MC et al. Slow-pull compared to suction technique for EUS-guided sampling of pancreatic solid lesions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8:E636–E643. doi: 10.1055/a-1120-8428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:777–784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attam R, Arain MA, Bloechl SJ et al. "Wet suction technique (WEST)": a novel way to enhance the quality of EUS-FNA aspirate. Results of a prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled trial using a 22-gauge needle for EUS-FNA of solid lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1401–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bansal RK, Choudhary NS, Puri R et al. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration by capillary action, suction, and no suction methods: a randomized blinded study. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E980–E984. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-116383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weston BR, Ross WA, Bhutani MS et al. Prospective randomized comparison of a 22G core needle using standard versus capillary suction for EUS-guided sampling of solid pancreatic masses. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E505–E512. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-105492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bang JY, Navaneethan U, Hasan MK et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided specimen collection and evaluation techniques affect diagnostic accuracy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1820–1.828E7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KY, Cho HD, Hwangbo Y et al. Efficacy of 3 fine-needle biopsy techniques for suspected pancreatic malignancies in the absence of an on-site cytopathologist. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:825–8310. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saxena P, El Zein M, Stevens T et al. Stylet slow-pull versus standard suction for endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of solid pancreatic lesions: a multicenter randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2018;50:497–504. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-122381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng S, Brunaldi VO, Minata MK et al. Suction versus slow-pull for endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic tumors: a prospective randomized trial. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Mitri R, Mocciaro F, Antonini F et al. Stylet slow-pull vs. standard suction technique for endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy in pancreatic solid lesions using 20 Gauge Procore needle: A multicenter randomized trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa-Moreira P, Vilas-Boas F, Martins D et al. use of suction during endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy of solid pancreatic lesions with a Franseen-tip needle: a pilot comparative trial. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E401–E408. doi: 10.1055/a-1336-3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong T, Tian L, Deng M et al. Comparison between modified wet suction and dry suction technique for endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy in pancreatic solid lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:1663–1669. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Wang RH, Ding Z et al. Wet- versus dry-suction techniques for endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of solid lesions: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2020;52:995–1003. doi: 10.1055/a-1167-2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bang YJ, Krall K, Jhala N et al. Comparing needles and methods of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy to optimize specimen quality and diagnostic accuracy for patients with pancreatic masses in a randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:825–8.35E9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takasumi M, Hikichi T, Hashimoto M et al. A pilot randomized crossover trial of wet suction and conventional techniques of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for upper gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2021;2021:4.913107E6. doi: 10.1155/2021/4913107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendoza Ladd A, Casner N, Cherukuri SV et al. Fine needle biopsies of solid pancreatic lesions: tissue acquisition technique and needle design do not impact specimen adequacy. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:4549–4556. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou W, Li SY, Jiang H et al. Optimal number of needle passes during EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy of solid pancreatic lesions with 22G ProCore needles and different suction techniques: A randomized controlled trial. Endosc Ultrasound. 2021;10:62–70. doi: 10.4103/EUS-D-20-00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paik WH, Choi JH, Park Y et al. Optimal techniques for EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic solid masses at facilities without on-site cytopathology: results from two prospective randomised trials. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4662. doi: 10.3390/jcm10204662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berzosa M, Uthamaraj S, Dragomir Daescu D et al. Mo1395 EUS‑FN wet vs. dry suction techniques; a proof of concept study on how column of water enhances tissue aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:AB421–AB422. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Artifon E, Guedes HG, Cheng S. Maximizing the diagnostic yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:881–885. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Riet PA, Giorgio AP, Petrone M et al. Combined versus single use 20 G fine-needle biopsy and 25G fine-needle aspiration for endoscopic ultra- sound-guided tissue sampling of solid gastrointestinal lesions. Endoscopy. 2020;52:37–44. doi: 10.1055/a-0966-8755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Riet PA, Cahen DL, Biermann K et al. Agreement on endoscopic ultra- sonography-guided tissue specimens: Comparing a 20-G fine-needle biopsy to a 25-G fine-needle aspiration needle among academic and non-academic pathologists. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:690–697. doi: 10.1111/den.13424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polkowski M, Jenssen C, Kaye P et al. Technical aspects of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Guideline- March 2017. Endoscopy. 2017;49:989–1006. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-119219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han S, Bhullar F, Alaber O et al. Comparative diagnostic accuracy of EUS needles in solid pancreatic masses: a network meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E853–E862. doi: 10.1055/a-1381-7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Facciorusso A, Wani S, Triantafyllou K et al. Comparative accuracy of needle sizes and designs for EUS tissue sampling of solid pancreatic masses: a network meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:893–9.03E9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gkolfakis P, Crinò SF, Tziatzios G et al. Comparative diagnostic performance of end-cutting fine-needle biopsy needles for EUS tissue sampling of solid pancreatic masses: a network meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:1067–1.077E18. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.