Dear Editor,

Male infertility is a complex and multifactorial health problem with highly heterogeneous phenotypes, ranging from reduced sperm production to the complete absence of sperm in testis, and genetic factors play an important role in this problem.1 Patients with azoospermia have the highest risk of carrying genetic abnormalities, and this risk gradually decreases as sperm count increases.1 Due to the high throughput and low cost of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, many centers have used NGS to identify genetic defects associated with abnormal spermatogenesis.2

Here, we report two infertile brothers with spermatogenetic failure (Supplementary Figure 1 (711.5KB, tif) ). The proband (III:2) was a 30-year-old Chinese man. After 3 months of combined treatment with integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine (Shengjing capsules, Vitamin E, and letrozole), his semen did not improve well. The patient and his spouse had intercourse without contraception two to three times a week but had not become pregnant for 5 consecutive years. He was 178 cm tall and weighted 77 kg, with normal external genital development, bilateral testicular volumes of approximately 12 ml, and no palpable abnormalities found in the bilateral spermatic cord and vas deferens. He underwent three semen examinations according to the guidelines in the 5th WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen.3 His semen volume was 2.0–3.5 ml (reference range: ≥1.5 ml), pH 7.2–7.5 (reference range: 7.2–8.0), but no spermatozoa was observed in the initial semen smear. Semen centrifugal sediment smear showed that the sperm count was 0–1 cells per high-power field (HPF) revealing cryptozoospermia. A total of 10–15 spermatozoa were found in 20 HPF, including 2–3 progressive (PR) motile sperm, 3–5 nonprogressive (NP) motile sperm, and 5–7 immotile (IM) sperm. Papanicolaou staining indicated that 2–3 spermatozoa had normal morphology. The total contents of neutral α-glucosidase, fructose, and zinc in seminal plasma (ChemWell BRED 2900, Awareness Technology Inc., Palm City, FL, USA) were all normal. The results of serum sex hormone levels (e601 automatic electrochemiluminescence immunoassay system, Roche Cobas®, Basel, Switzerland) were as follows: follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)=5.75 (reference range: 1.5–12.4) mIU ml−1, luteinizing hormone (LH)=5.89 (reference range: 1.7–8.6) mIU ml−1, testosterone (T)=5.24 (reference range: 2.49–8.36) ng ml−1, estradiol (E2)=33.19 (reference range: 7.6–42.6) pg ml−1, and prolactin (PRL)=8.35 (reference range: 4.6–21.4) ng ml−1. The levels of thyrotropin, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), inhibin B, and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) were all normal. His peripheral blood karyotype was 46,XY (G-band analysis, 400 resolution banding) according to the International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature 2020.4 No site deletion was found in the Y chromosome microdeletion azoospermia factor (AZF) region by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using the Y Chromosomal Microdeletion Test Kit (Tellgen Corporation, Shanghai, China) based on the European Academy of Andrology (EAA) guidelines,5 detecting the sY84 and sY86 sequence-tagged sites (STSs) of AZFa, the sY127 and sY134 STSs of AZFb, and the sY254 and sY255 STSs of AZFc. His brother (III:3) also experienced infertility through 3 years of marriage; he had normal erection and ejaculation during intercourse, but there was no conception during this time. Several semen tests indicated that no sperm could be found in his initial semen smear, but 0–1 motile sperm were occasionally seen after the semen centrifugation smear, also revealing cryptozoospermia. No obvious abnormalities were found in the physical examination and laboratory tests (including sex hormones, inhibin B, Y chromosome microdeletion and peripheral blood karyotype analysis).

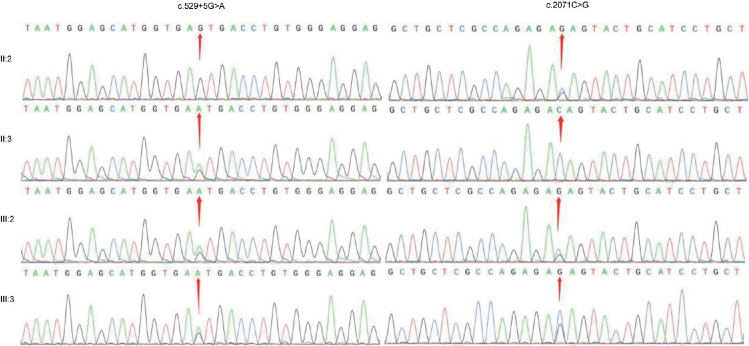

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital (Yantai, China; approval No. 2020-017) and informed consent was obtained from the participants. Blood samples of the two brothers and their parents were collected. Genomic DNA of the proband (III:2) was extracted for whole exome sequencing (WES) from peripheral blood using QIAGEN Universal DNA Purification Kit (QIAGEN, Dusseldorf, Germany). The IDT xGen Exome Research Panel version 1.0 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) was used for exome capture according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for exomic DNA sequencing. The coverage of each read is at least 10×, and the average coverage of the entire exome is 100×. Sequencing reads were aligned to the reference human genome (hg37) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA), and duplicate reads were marked using Sambamba tools. The raw calls of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions and deletions (Indels) were further filtered with the following inclusion thresholds: (1) a read depth >4; (2) a root-mean-square mapping quality of the covering reads >30; and (3) a variant quality score >20. The copy number variants (CNVs) from the WES data were detected using the SVD-ZRPKM algorithm CoNIFER (http://sv.gersteinlab.org/cnvnator/). Annotation was performed using ANNOVAR (https://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/). Filtering of rare variants was performed as follows: (1) variants with an MAF less than 0.01 in 1000 genomic data (1000g_all), esp6500siv2_all, gnomAD data (gnomAD_ALL and gnomAD_EAS) and the Chinese Gene Mutation Database (CNGMD); (2) only SNVs occurring in exons or splice sites (splicing junction 10 bp) were further analyzed because we were interested in amino acid changes; and (3) synonymous SNVs that were not relevant to the amino acid alternations predicted by dbscSNV were discarded; small free gene fragment nonframeshift (<10 bp) indels in the repeat regions defined by RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org/) were also discarded. SNVs and indels were compared with the databases of the 1000 Genomes Project, the Exome Aggregation Consortium database (ExAC), Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) and allele frequency in the CNGMD. MutationTaster, Sorting Intolerant Form Tolerant (SIFT), Polymorphism Phenotyping version 2 (PolyPhen-2), Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling (GERP), Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD), Revel score, and Mendelian Clinically Applicable Pathogenicity (M-CAP) software programs were used to predict the hazards of mutations. The pathogenicity of variants was classified according to the guidelines of American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG).6 The novelty of gene variations was evaluated by using the ClinVar database. A novel compound heterozygous mutation was identified in the meiotic double-stranded break formation protein 1 (MEI1) gene (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM]: 608797), including the missense mutation c.2071C>G (p.Gln691Glu) located in exon 18 and the splicing mutation c.529+5G>A located downstream of exon 5. These two variants have not been included in ExAC or gnomAD thus far. According to ACMG guidelines, the two variants of MEI1 are rated as follows. c.529+5G>A: PM2_Supporting+PM3_Supporting+PP1+PP3+PP4; c.2071C>G: PM2_Supporting+PP1+PP4+BP4-Moderate. This compound heterozygous mutation was confirmed by Sanger sequencing in the proband and his brother. The father (II:2) of the brothers was a c.2071C>G heterozygous carrier, while their mother (II:3) was a c.529+5G>A heterozygous carrier (Figure 1). The splicing mutation of c.529+5G>A is predicted to be class 5 according to the splice site variation prediction website varSEAK (https://varseak.bio/index.php), which likely will affect gene splicing. Prediction software such as MutationTaster, SIFT, Functional Analysis through Hidden Markov Models (FATHMM), and M-CAP all predicted the deleteriousness of the missense mutation c.2071C>G. From the pedigree of the two brothers, only their father carried the c.2071C>G heterozygous mutation and had normal fertility, while the two brothers showed infertility due to cryptozoospermia. Considering the two brothers had the same phenotype, we speculate that the compound heterozygous mutation found may be the cause of their spermatogenetic failure. Due to the extremely limited availability of sperm from the brothers, the MEI1 mRNA or MEI1 protein in sperm cannot be evaluated, and their testicular tissue cannot be obtained for further immunohistochemistry studies.

Figure 1.

Sanger sequencing results showing the compound heterozygous mutation c.529+5G>A and c.2071C>G in the proband (III:2) and his brother (III:3). Their father (II:2) was a heterozygous carrier of c.2071C>G, while their mother (II:3) was a heterozygous carrier of c.529+5G>A.

Spermatogenesis is a multistep orderly process, including the proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonia, meiosis of spermatocytes, and spermiogenesis of spermatids.7 Meiosis steps are necessary processes for haploid spermatozoa formation, during which homologous chromosomes undergo pairing, synapses, and recombination.7 Mei1 is one of the meiosis-specific mutations identified through a forward genetic approach in mammals, with the causative influence on infertility associated with the meiotic arrest phenotype.8 In homozygous male Mei1 knockout mice, mutant spermatocytes were not able to assemble RADiation sensitive 51 (RAD51; required for mediation of DNA double-strand break repair templated by sister chromatids) onto meiotic chromosomes, resulting in the failure of homologous chromosome synapsis, leading to spermatocyte block at the zygotene stage.8 Additional studies have found that Mei1 mainly acts upstream of disruption meiotic cDNA1 (DMC1; mediates DNA double-strand break repair templated by homologous chromosomes) during meiosis.9 In 2015, Li et al.10 identified and cloned the bovine meiosis defective 1 (bMei1) gene for the first time. Their study found that the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of bMei1 were highly similar to those of other mammals, and bMei1 also plays an important role in the initiation of meiotic recombination.10 Sato and colleagues detected human MEI1 cDNA from the testis using the deduced amino acid sequence of mouse Mei1 cDNA, and revealed the location of MEI1 in chromosome 22 (22q13.2).11 In that study, they found that MEI1 is mainly expressed in the testis but also weakly expressed in other human tissues. They analyzed the possible association of MEI1 mutations with human azoospermia caused by meiotic arrest.12 Ben Khelifa and his team used WES technology to screen and identify a homozygous missense mutation c.C3307T (p.Arg1103Trp) in the MEI1 among two infertile brothers from a consanguineous Tunisian family, which was the first report of nonobstructive azoospermia (NOA) caused by MEI1 gene mutation due to meiotic arrest.12 According to another study, two missense mutations c.1088C>T (p.Thr363Met) and c.925C>T (p.Leu309Phe) were found in 147 selected maturation arrest (MA) patients through WES.13 We report two brothers with infertility and cryptozoospermia in this study, both of whom carry the compound heterozygous mutation in MEI1 (including a splicing mutation of c.529+5G>A and a missense mutation of c.2071C>G). We can suggest that the combination of the two heterozygous variants may cause slight expression of MEI1 and thus sometimes allow meiosis to occur, resulting in cryptozoospermia rather than NOA. Therefore, MEI1 is an essential protein for achieving meiosis.

In conclusion, we identified a new compound heterozygous mutation in MEI1 through WES and Sanger sequencing in two infertile brothers with cryptozoospermia. The mutations were inherited from their parents, who were both single heterozygous carriers, indicating a recessive pattern of inheritance. This is a sporadic case report of male infertility caused by MEI1 compound heterozygous mutation. Our study deems to confirm that the MEI1 gene is involved in the process of spermatogenesis, but its molecular regulatory mechanism in mammalian spermatogenesis still needs to be further studied. We believe that MEI1 may become the next clinical marker for the detection of spermatogenetic failure.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

XW and YQC designed the study. JC and FHL carried out the genetic studies and wrote the manuscript. JHX analyzed high-throughput sequencing data. XBZ extracted DNA and performed Sanger sequencing. ZLD screened for candidate genes. YSJ collected clinical data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declare no competing interests. The Yinfeng Gene Technology Co., Ltd. mentioned in the article does not interfere with the topic selection and results of this article.

Pedigree chart of the patients. The arrow indicates the proband (III:2) and his brother (III:3). MEI1: meiotic double-stranded break formation protein 1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Youth Scientific Research Fund of Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital (No. Kj0215). Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Asian Journal of Andrology website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krausz C, Riera-Escamilla A. Genetics of male infertility. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:369–84. doi: 10.1038/s41585-018-0003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannarella R, Condorelli RA, Paolacci S, Barbagallo F, Guerri G, et al. Next-generation sequencing: toward an increase in the diagnostic yield in patients with apparently idiopathic spermatogenic failure. Asian J Androl. 2021;23:24–9. doi: 10.4103/aja.aja_25_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. 5th ed. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGowan-Jordan J, Hastings RJ, Moore S, editors. Basel: Karger; 2020. ISCN 2020: An International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature; pp. 341–503. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krausz C, Hoefsloot L, Simoni M, Tüttelmann F. EAA/EMQN best practice guidelines for molecular diagnosis of Y-chromosomal microdeletions: state-of-the-art 2013. Andrology. 2014;2:5–19. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2013.00173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neto FT, Bach PV, Najari BB, Li PS, Goldstein M. Spermatogenesis in humans and its affecting factors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;59:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Libby BJ, De La Fuente R, O’Brien MJ, Wigglesworth K, Cobb J, et al. The mouse meiotic mutation mei1 disrupts chromosome synapsis with sexually dimorphic consequences for meiotic progression. Dev Biol. 2002;242:174–87. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libby BJ, Reinholdt LG, Schimenti JC. Positional cloning and characterization of Mei1, a vertebrate-specific gene required for normal meiotic chromosome synapsis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15706–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2432067100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li B, Wu W, Luo H, Liu Z, Liu H, et al. Molecular characterization and epigenetic regulation of Mei1 in cattle and cattle-yak. Gene. 2015;573:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato H, Miyamoto T, Yogev L, Namiki M, Koh E, et al. Polymorphic alleles of the human MEI1 gene are associated with human azoospermia by meiotic arrest. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:533–40. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben Khelifa M, Ghieh F, Boudjenah R, Hue C, Fauvert D, et al. A MEI1 homozygous missense mutation associated with meiotic arrest in a consanguineous family. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1034–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krausz C, Riera-Escamilla A, Moreno-Mendoza D, Holleman K, Cioppi F, et al. Genetic dissection of spermatogenic arrest through exome analysis: clinical implications for the management of azoospermic men. Genet Med. 2020;22:1956–66. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0907-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Pedigree chart of the patients. The arrow indicates the proband (III:2) and his brother (III:3). MEI1: meiotic double-stranded break formation protein 1.