Abstract

Mg-ion batteries offer a safe, low-cost, and high–energy density alternative to current Li-ion batteries. However, nonaqueous Mg-ion batteries struggle with poor ionic conductivity, while aqueous batteries face a narrow electrochemical window. Our group previously developed a water-in-salt battery with an operating voltage above 2 V yet still lower than its nonaqueous counterpart because of the dominance of proton over Mg-ion insertion in the cathode. We designed a quasi-solid-state magnesium-ion battery (QSMB) that confines the hydrogen bond network for true multivalent metal ion storage. The QSMB demonstrates an energy density of 264 W·hour kg−1, nearly five times higher than aqueous Mg-ion batteries and a voltage plateau (2.6 to 2.0 V), outperforming other Mg-ion batteries. In addition, it retains 90% of its capacity after 900 cycles at subzero temperatures (−22°C). The QSMB leverages the advantages of aqueous and nonaqueous systems, offering an innovative approach to designing high-performing Mg-ion batteries and other multivalent metal ion batteries.

The quasi-solid-state Mg-ion battery boasts 5× energy density, enhanced voltage, and excellent low-temperature performance.

INTRODUCTION

Beyond Li-ion battery technology, rechargeable multivalent-ion batteries such as magnesium-ion batteries have been attracting increasing research efforts in recent years. With a negative reduction potential of −2.37 V versus standard hydrogen electrode, close to that of Li, and a lower dendrite formation tendency, Mg anodes can potentially deliver high energy with stable performance (1–5). Compared to Li-ion batteries, Mg-ion batteries also benefit from higher material abundance, higher safety, and lower cost (6–8). Nonetheless, Mg metal is notorious for its passivating behavior, which impedes redox reactions, especially in highly reducible electrolytes. To prevent passivation at the Mg anode, most rechargeable Mg-ion battery studies use nonaqueous liquid electrolytes composed of complex salts and organic solvents (8–12). However, the poor conductivity of organic Mg-ion electrolytes restricts their diffusion kinetics and requires high temperature to maintain battery performance (13). They also demand a moisture-free and oxygen-free environment and pose severe safety risks due to their toxicity and flammability, similar to conventional Li-ion electrolytes.

Considering the drawbacks of nonaqueous Mg-ion batteries (NAMBs), some researchers studied aqueous Mg-ion systems for a safer, more cost-effective, and practical alternative. The higher conductivity of conventional aqueous electrolytes could facilitate redox activity and enhance battery performance (14). However, the narrow electrochemical stability window (ESW) of 1.23 V critically restricts the battery’s operation voltage and energy density (15–17). Current aqueous Mg-ion batteries (AMBs) typically consist of intercalation-type electrodes operated in aqueous electrolytes and suffer from limited voltages below 1.5 V (18–21). To widen the ESW, Wang et al. (18) used a superconcentrated Mg(TFSI)2 electrolyte to suppress water activity. When coupled with a poly pyromellitic dianhydride (PPMDA) anode and lithium vanadium phosphate (LVP) cathode, the full cell demonstrates a specific capacity of 52 mA·hour g−1, but the average discharge voltage and energy density are still limited to 1.2 V and 68 W·hour kg−1, respectively. It is challenging to find appropriate pairs of high-voltage Mg-ion hosts at both electrodes (22).

In light of this, we previously reported an AMB with a MgCl2 water-in-salt (MgCl2-WIS) electrolyte that directly uses magnesium metal as the anode (23). Owing to an expanded ESW and Cl-induced dissolution chemistry, surface passivation is stabilized and reversible Mg stripping/plating can be achieved. By using a Mg metal anode directly, the full battery benefits from its negative redox potential and exhibits a high voltage plateau of 2.4 to 2.0 V over 700 stable cycles, making a breakthrough in AMBs.

Nonetheless, challenges remain in enhancing the performance of AMBs at the cathode. Although the reversible insertion and extraction of Mg2+ ions have been reported in several types of host materials, including Prussian blue analogs, MnO2, MgMn2O4, and V2O5 (19, 21, 24, 25), the operating voltage remains lower than their nonaqueous counterparts (up to 2.6 V) (13). Contrary to popular assumption, recent findings revealed that H+ ions, rather than multivalent metal ions (Mg2+, Zn2+, Al3+, etc.), are the dominant intercalating ionic species in aqueous multivalent metal ion batteries (26–28). Because of their lower charge-to-size ratio, protons experience weaker electrostatic repulsion than multivalent metal ions and can easily insert into the host structure (29). However, this competition with multivalent metal ions prevents full realization of the multielectron redox reaction and produces lower energy density and stability. Despite substantial advances in cathode material design for AMBs, the battery performance remains limited by the dominance of proton intercalation because the regulation of the intercalating ion species is often overlooked. To address this issue and unlock the full potential of Mg-ion batteries, the development of an advanced electrolyte is imperative.

In this work, an innovative quasi-solid-state Mg-ion battery (QSMB) with a high energy density of 264 W·hour kg−1 was developed. Quasi-solid-state electrolytes have gained tremendous research attention in recent years as a safer, more stable, and leakproof alternative to conventional liquid organic electrolytes in Li-ion batteries. Inspired by quasi-solid-state Li-ion batteries, this work uses polyethylene oxide (PEO) to immobilize the water network of the aqueous Mg-ion electrolyte. Combining the advantages of aqueous systems with high ionic conductivity and nonaqueous systems with a wide electrochemical window, the full Mg/copper hexacyanoferrate (CuHCF) battery displays high voltage (2.6- to 2.0-V plateau) and stability over 900 cycles. From in situ characterizations and theoretical simulations, we reveal that the quasi-solid-state electrolyte not only restricts proton insertion and promotes Mg2+ storage in the cathode host but also triggers the high-voltage (de-)intercalation of (MgCl3·H2O)− anions to deliver superior battery performance. Following our previous study where the reversibility of the Mg anode in a water-scarce MgCl2 electrolyte was demonstrated (23), this work examines how the charge storage mechanisms at the cathode are altered to deliver high energy density. We further reveal how the chemical insights obtained can be applied to design other high-voltage quasi-solid-state multivalent-ion batteries like Zn-ion and Al-ion batteries.

RESULTS

Widened voltage window and enhanced ionic conductivity

The use of the PEO polymer network plays a primary role in delivering the battery’s high electrochemical performance by expanding its ESW in comparison to traditional aqueous solutions. The ESW of MgCl2-PEO is notably wider than 1 M MgCl2 and MgCl2-WIS, as the onsets of hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) have become barely detectable between 0.0 and 4.0 V versus Mg/Mg2+ (Fig. 1A and fig. S1). As measured by in situ online electrochemical mass spectroscopy (OEMS), Mg symmetrical battery cycling in MgCl2-WIS experiences occasional H2 gas spikes, while in MgCl2-PEO, the H2 evolution becomes negligible (0.15 μmol/s; Fig. 1B). This value is similar to those in reported polyethylene glycol (PEG)–enhanced Li-ion batteries, where water decomposition has been practically eliminated (30, 31). MgCl2-PEO demonstrates strong electrochemical stability and suppression of HER without the need for ultrahigh salt concentrations, which can be attributed to the strong hydrogen bond anchoring effect of PEO.

Fig. 1. Hydrogen bond anchoring effect of PEO.

(A) ESW of 1 M MgCl2, MgCl2-WIS, and MgCl2-PEO at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1. (B) In situ OEMS measurement of H2 gas flux during the cycling of a Mg symmetrical battery. (C) Schematic diagram of the hydrogen bond network and solvation sheaths in traditional aqueous MgCl2, MgCl2-WIS, and MgCl2-PEO. (D) FTIR spectra and (E) 1H NMR spectra of 0.1, 1, and 3 M MgCl2, MgCl2-WIS, and MgCl2-PEO. (F) Radial distribution function g(r) and integrated coordination number (ICN) n(r) profiles of Mg2+-H2O (left) and the final MD simulation model of MgCl2-PEO (right). a.u., arbitrary units. ppm, parts per million.

Because of the higher negative charge density of the oxygen atom in PEO owing to the inductive effect of alkyl groups (15, 31), the presence of PEO in the electrolyte interacts strongly with water molecules, leading to the replacement of H2O─H2O hydrogen bonds with H─O coordination between H2O and PEO. Because more energy is required to break the covalent bonds between H2O and PEO, water decomposition and hydrogen activity are effectively suppressed (Fig. 1C) (30, 32). This reinforcement of the H─O bond is shown by the upfield peak shift in the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectrum of MgCl2-PEO compared with MgCl2-WIS at 1608 and 3330 cm−1, which represent the bending and stretching vibrations of H─O bonds, respectively (Fig. 1D). The disappearance of the ─OH peak at 3450 cm−1 also signifies the reduction in dissociated H2O as the hydrogen bonds become anchored (33). The breakdown of the water network is also evident from O─H stretches in the Raman spectrum, with a dominance of the high-frequency band at 3415 cm−1 (fig. S2). Moreover, the 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra exhibit an upfield peak shift of H2O in MgCl2-PEO, which indicates higher electron density around the H atom and suggests the strengthening of covalent H─O bonds between PEO and H2O (Fig. 1E) (30, 34). This reorganization of the proton donor framework has also been reported in LiTFSI-PEG-H2O and LiTFSI-PEGDME-H2O electrolytes, owing to similar effects of hydrogen bonding with the polymer network (30, 31). As a higher overpotential is needed to electrochemically decompose a stronger covalent bond, the ESW is substantially widened in the presence of PEO.

These experimental results are corroborated by molecular dynamics (MD) simulation (see models in fig. S3). Strong association between PEO and H2O is revealed by their radial distribution function in MgCl2-PEO, showing sharp peaks at 1.95, 2.1, and 2.9 Å (fig. S4). Furthermore, solvated Mg ions appear to undergo partial dehydration in MgCl2-PEO due to strong H2O-PEO coordination. In contrast to MgCl2-WIS where a sharp distinctive peak appears at the first solvation shell of Mg (2.1 Å), the g(r) profile of Mg-H2O in MgCl2-PEO shows a weaker and broader peak at 2.2 Å (36) (Fig. 1F) (35). The integrated coordination number (ICN) of Mg-H2O at a radial distance of 3.5 Å drops from 3.0 to 2.2 when PEO is present. Approximately 27% of solvated water molecules have left the solvation sheath of Mg ions as the water networking becomes broken by PEO coordination. The solvation structure of ions reorganizes, and more direct contact between Mg and Cl ions is promoted, generating a molecular crowding effect (fig. S5A) (15). The uniform dispersal of Mg and Cl ions in the quasi-solid-state electrolyte are illustrated by scanning electron microscopy–energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) mapping (fig. S6). Despite hydrogen bond anchoring, the quasi-solid-state electrolyte benefits from the immobilized water network and exhibits an ionic conductivity of 1.24 mS cm−1, superior to those of nonaqueous Mg-ion electrolytes and all-solid-state electrolytes, which are commonly in the order of 10−6 to 10−4 S cm−1 at room temperature (table S1) (36–41). Ionic interactions between PEO and their effects on diffusion behavior and ionic conductivity are further discussed in the Supplementary Materials (fig. S7 and table S2).

Suppressed proton insertion

The hydrogen anchoring effect of the quasi-solid-state electrolyte promotes battery performance by inhibiting proton insertion and facilitating high-voltage Mg ion storage into the cathode. As discussed earlier, the competition between the insertion of protons and multivalent metal ions into the host cathode is commonly observed in aqueous multivalent metal ion batteries. For instance, it was reported that the charge compensation in Prussian blue analogs originates from protons rather than Mg2+ ions in aqueous Mg solutions (26). This behavior is confirmed by cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans of the CuHCF cathode in aqueous MgCl2 solutions of different pH values in this work (Fig. 2A). The proton and Mg ion coinsertion process is made up of two reduction peaks at similar voltages, demonstrating their competitive relationship. As the proton concentration increases, the lower-voltage discharge peak at 0.2 V versus Ag/AgCl becomes much more pronounced than the peak centered at 0.5 V versus Ag/AgCl, which indicates that the lower-voltage peak is H+ dominated. Electrochemical kinetic analysis of the pH 1 system reveals that the redox kinetics of the lower-voltage reduction peak is mainly surface controlled, which suggests pseudocapacitive H+ behavior (b = 0.95; see fig. S8) (42, 43). The higher-voltage reduction peak shows a half-capacitive, half-diffusion behavior (b = 0.69) that could be attributed to a mixture of protons and Mg ions.

Fig. 2. Electrochemical experiments and simulation studies showing suppressed proton insertion in CuHCF.

(A) CV curves of CuHCF at a scan rate of 10 mV/s and (B) galvanostatic discharge curves of the Mg/CuHCF full battery in aqueous MgCl2 with different pH values, MgCl2-WIS, and MgCl2-PEO. (C) Intercalation voltages of Mg and H ions simulated by DFT studies. (D) The crystal structure (conventional cell) of M2Cu[Fe(CN)6], where M = Mg2+ or H+. (E and F) CV experiments of CuHCF at a scan rate of 10 mV/s and (G and H) galvanostatic cycling curves of Zn-ion and Al-ion batteries under 1 M ZnCl2, ZnCl2-PEO, 1 M AlCl3, and AlCl3-PEO. Zn metal and Al metal anodes are used in the cycling experiments.

In traditional aqueous MgCl2 solutions (from pH 1 to 5), Mg2+-dominated discharge plateaus are absent at high voltages (>2.0 V) because Mg2+ intercalation is constrained by proton activity (Fig. 2B). At pH 5 and pH 3, intense competition between Mg2+ and H+ ions prevents sufficient intercalation of either ion species and therefore critically restricts the battery capacity. At pH 1, the strong proton concentration allows H+ insertion to dictate and generate higher capacity, but the H+-dominated discharge plateau is clearly at a lower voltage (<2.0 V). On the other hand, once water activity is sufficiently restricted in MgCl2-WIS and MgCl2-PEO, the H+-dominated reduction peak disappears (Fig. 2A) and the high-voltage discharge plateau becomes elongated, in sharp contrast to H+-dominated sloping regions in the traditional MgCl2 solutions (Fig. 2B). Although the pH of MgCl2-PEO (pH = 5.7) is only slightly higher than the aqueous MgCl2 solution of pH 5, the MgCl2-PEO system performs much better because of PEO coordination with hydrogen bonds (fig. S9). Because of its long chains and high molecular weight, PEO creates strong interactions with water and effectively anchors the hydrogen bonds. Compared to the use of PEG in the same electrolyte composition, MgCl2-PEO has a substantially wider ESW, enabling it to display the high-voltage anion extraction peak that MgCl2-PEG cannot (fig. S10). According to first principles–based density functional theory (DFT) simulations, the lower formation energies of Mg-CuHCF compared to H-CuHCF shows that Mg storage is more favorable and stable than proton insertion (fig. S11). As a result, Mg ions exhibit higher intercalation voltage as simulated, which coincides well with the experimental discharge curves (Fig. 2, C and D). Evidently, the suppression of proton insertion could promote higher-performing Mg ion storage processes.

Voltage enhancement can be similarly achieved in quasi-solid-state Zn-ion and Al-ion batteries using PEO as a hydrogen bond anchorer. Higher-voltage reduction peaks in CV experiments are obtained in the PEO-based ZnCl2 and AlCl3 electrolytes when compared to 1 M aqueous solutions (Fig. 2, E and F). As proton insertion into CuHCF becomes mitigated, high-voltage multivalent metal ion intercalation can be facilitated, resulting in enhanced voltages and capacities during battery discharge (Fig. 2, G and H). In the AlCl3-PEO system, hydrogen bond anchoring even facilitates high-voltage AlCl4− anion (de-)intercalation, as evidenced by the reduction peak at 0.6 to 1.15 V versus Ag/AgCl, which has been reported in highly concentrated AlCl3 electrolytes (44, 45). Although chlorine evolution could also contribute to this peak, its broad shape and sloping voltage plateau suggest that anion (de-)insertion is likely the primary electrochemical reaction. The proton anchoring ability of quasi-solid-state electrolytes provides a universal strategy to actively facilitate the intercalation of multivalent metal ions in aqueous batteries.

To obtain direct evidence of proton storage suppression, ex situ x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterizations and in situ Raman spectroscopy were performed to comprehend the precise chemical changes within the CuHCF cathode. When the cell was fully discharged in 1 M MgCl2, the XPS N 1s spectrum of CuHCF reveals a rise of N─H bonds upon proton insertion, but when discharged under MgCl2-PEO, no changes from the pristine state are observed. Only ─C≡N─Fe and ─N─Fe bonds from the lattice itself are present (Fig. 3A) (46, 47). In the O 1s spectrum of CuHCF, the rise of O─H bonds upon discharging in 1 M MgCl2 demonstrates that protons also coordinate with functional groups (Fig. 3B) (48–50). In addition, there is a clear rise of the C 1s sp3 peaks consisting of C─H bonds (47, 51, 52) (Fig. 3C). The sp3 to C─N peak area ratio increases substantially from 0.84 in pristine CuHCF to 1.23 when discharged in 1 M MgCl2, which could be ascribed to proton insertion. In situ Raman experiments also show that the original C─H stretching band centered at 2948-cm−1 shifts to lower wavenumber positions during discharge and gradually migrates back to resemble the pristine state when charged (Fig. 3, D and E). This reconstruction of C─H bonds can be attributed to changes in CH3 versus CH2 modes due to hydrogen bond interactions (53, 54), indicating that C─H groups act as active sites for H+ coordination. This shift was also observed when CuHCF was cycled in HCl without the interference of any Mg ions (fig. S12). However, when operated under MgCl2-PEO, the C─H stretching region from 2900 to 2950 cm−1 does not show notable movement, indicating the lack of H+ storage in the presence of PEO. At fully discharged state, the XPS C 1s sp3 to C─N peak area ratio remains similar to the pristine state at 0.87 (Fig. 3C) (55, 56). The quasi-solid-state electrolyte restricts proton storage in CuHCF, which is consistent with the electrochemical data. Because of the presence of carbon nanotubes in the CuHCF samples, the intensity of the sp2-bonded C═C peaks representing graphitized carbon varies. However, the obvious decline in the sp2 peaks when discharged in MgCl2-PEO suggests a disruption in the orderly carbon interlayers caused by substantial Mg ion insertion (57).

Fig. 3. Material characterization of CuHCF cathode at different states of charge operated under 1 M MgCl2 and MgCl2-PEO.

(A to C) Ex situ XPS spectra for (A) N 1s, (B) O 1s, and (C) C 1s. (D) Representative galvanostatic cycling curve of the Mg/CuHCF battery, illustrating the corresponding states of charge for the following in situ experiments: (E) in situ Raman spectra and (F and G) in situ XRD characterization and comparison.

To further study the structural evolution of CuHCF during the ion storage processes, in situ x-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments were performed. The (400) and (420) peaks indexed to the cubic structure of the CuHCF lattice (58) show a gradual shift to higher angles when the MgCl2-PEO system was discharged (Fig. 3F). This indicates lattice expansion from ion insertion (32, 59). During charging, the peaks shift back to lower angles as ions extract and the lattice contracts. At the fully charged state, the peaks migrate past their pristine positions, owing to subsequent insertion of complex anions (see the “High-voltage dual Mg-ion storage” section). This structural change is stronger in MgCl2-PEO than in 1 M MgCl2, as shown from the larger peak movement (Fig. 3G). In 1 M MgCl2, ion storage is dominated by smaller H+ ions during discharge (26), but when the addition of PEO restricts H+ activity and favors the intercalation of bigger Mg ions instead, the CuHCF lattice experiences a larger structural change.

High-voltage dual Mg-ion storage

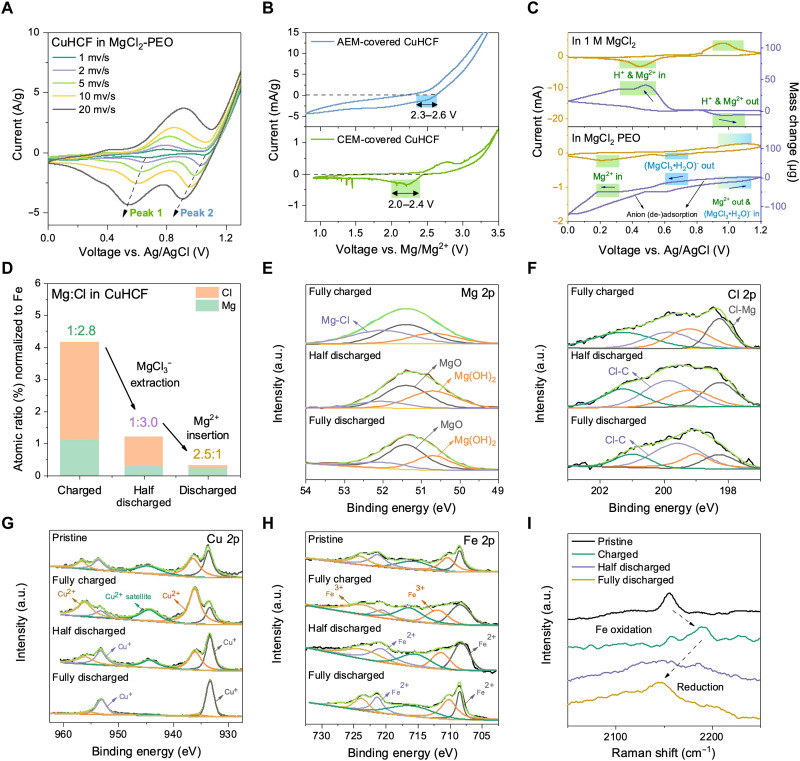

With the restriction of H+ insertion and enhanced electrochemical stability, the storage of both Mg2+ and MgCl3− charge carriers were found in the CuHCF cathode after battery cycling. A series of CV experiments on the CuHCF reveal two major reduction peaks centered at around 0.9 V versus Ag/AgCl and 0.5 V versus Ag/AgCl (Fig. 4A). Using an anion exchange membrane (AEM)–covered CuHCF, the high reduction peak remains, which correspond to 2.3 to 2.6 V versus Mg/Mg2+, while a lower reduction peak at 2.0 to 2.4 V versus Mg/Mg2+ is obtained with a cation exchange membrane (CEM)–covered CuHCF (Fig. 4B). The battery undergoes a high-voltage extraction of anion species, followed by cation insertion during discharge. The cation-induced reduction peak is driven by a fully insertion-dominated mechanism, free of the pseudocapacitive behavior from protons (b = 0.52; fig. S13).

Fig. 4. Dual Mg-ion storage in CuHCF.

(A) CV curves of CuHCF cathodes in MgCl2-PEO at scan rates varying from 1 to 20 mV s−1. (B) CV curves of Mg/CuHCF full cells with CuHCF cathodes separately covered by AEM and CEM at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1. (C) EQCM measurements of the mass change of the CuHCF electrode during in situ CV scans in 1 M MgCl2 and MgCl2-PEO. (D) A comparison of the atomic ratios of Mg and Cl, normalized with respect to Fe, in CuHCF at different states of charge, obtained by SEM-EDS. (E to I) Characterization of the CuHCF cathode at different states of charge operated under MgCl2-PEO. XPS spectra for (E) Mg 2p, (F) Cl 2p, (G) Cu 2p, (H) Fe 2p, and (I) Raman spectroscopy.

To identify the specific anion and cation species stored, in situ electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (EQCM) tests were conducted on CuHCF to measure its mass change during CV scans (Fig. 4C). By comparing the measured mass-to-charge (m/Q) ratio to the theoretical values of various ionic species, the most probable ions involved at each reaction stage are identified. In 1 M MgCl2, the closest possible mechanism is the (de-)intercalation of a mixture of H+ and Mg2+ ions as the m/Q ratio lies between those of the two ion species. In MgCl2-PEO, the higher-voltage reduction peak matches most with (MgCl3·H2O)− extraction and deadsorption. It is plausible that (MgCl3·H2O)− undergoes desolvation upon entering the CuHCF lattice; however, a reliable assessment of its solvation arrangement remains elusive (table S3 and S4; see detailed discussion in the Supplementary Materials). Nonetheless, the lower-voltage reduction peak aligns much better with the insertion of Mg2+ rather than H+, which again confirms the restriction of H+ insertion. The Raman spectrum of MgCl2-PEO exhibits a peak centered at 356 cm−1 representing the abundance of hydrated Mg2+ ions (60) and a peak at 237 cm−1 indicating the stretching motion of (MgCl3·H2O)− (fig. S14) (32). Previous studies have reported MgCl3− as a battery charge carrier, and it is also considered the most stable Mg-Cl complex ion (32, 61, 62). The presence of MgCl3− anions is also confirmed by MD simulations, which display an ICN of 3.2 between Mg2+ and Cl−, with the highest occurrence of Mg2+-n(Cl−) at n = 3 (fig. S5).

This dual-ion redox process is verified by ex situ EDS analyses of CuHCF at different states of charge (Fig. 4D and table S5). When fully charged, the Mg:Cl atomic ratio was 1:2.8, which demonstrates the storage of MgCl3− within experimental error. As MgCl3− ions insert during battery charging, ex situ XPS results show prominent inorganic Mg-Cl peaks in both the Mg 2p and Cl 2p spectra (Fig. 4, E and F) (45, 63, 64). The XPS Cu 2p spectrum reveals the oxidation of Cu as the Cu2+ peaks intensify compared to the pristine state (Fig. 4G). Fe becomes oxidized simultaneously, as shown by the enhancement of Fe3+ relative to Fe2+ peaks in the Fe 2p spectra (Fig. 4H) and the upward shift of the 2156-cm−1 band to 2188 cm−1 in the Raman spectrum (Fig. 4I) (65–68). This can be attributed to charge compensation as the MgCl3− ion intercalates. Transmission electron microscopy–EDS mapping also provides visual evidence of both Mg and Cl elements in the cathode material after charging (fig. S15). In comparison, no changes can be observed in the XPS Cu 2p spectrum of CuHCF charged in 1 M MgCl2, indicating that anion insertion is absent without hydrogen bond anchoring (fig. S16). When subsequently discharged to 2.3 V, the Mg and Cl percentages in CuHCF with respect to Fe has dropped substantially, yet traces of MgCl3− can still be detected as the Mg:Cl atomic ratio remains 1:3.0. The Mg-Cl bonds in both the Mg 2p and Cl 2p spectra are weakened, while Cu+ and Fe2+ peaks become stronger, which agrees precisely with the extraction of MgCl3− ions (Fig. 4, E to H). The 2188-cm−1 Raman band shifts back toward a lower wavenumber as Fe3+ becomes reduced back to the pristine state (Fig. 4I). However, after full discharge to 1.6 V, the Mg content surpasses Cl. As Mg2+ ions insert into the CuHCF lattice, Mg─O peaks and organic Cl─C peaks dominate instead of Mg─Cl bonds in the XPS spectra. Cu+ and Fe2+ peaks become even stronger, and the Raman band further decreases to 2145 cm−1 as Fe is reduced.

Combining the above evidence, a dual-ion reaction mechanism is uncovered where MgCl3− inserts into the CuHCF lattice during battery charging and extracts during high-voltage discharge, followed by the insertion of Mg2+ during subsequent discharge. The capacity contribution of MgCl3− is substantial, roughly 51%, and remains very stable over long-term cycling at 1 A g−1 (fig. S17; see further discussion). Most previous studies on aqueous Mg-ion electrolytes have only observed Mg2+ and H+ cointercalation mechanisms, but evidently, the expanded ESW of MgCl2-PEO not only successfully inhibits proton insertion but also enables the storage of both MgCl3− and Mg2+, contributing to high-voltage battery operation.

Electrochemical performance of the quasi-solid-state battery

A schematic design of the QSMB is illustrated in Fig. 5A. At a current rate of 0.25 A g−1, the assembled battery displays a remarkable discharge voltage plateau of 2.6 to 2.0 V and a specific capacity of 120 mA·hour g−1 between 2.6 and 1.6 V (Fig. 5B). This remarkable performance improvement from the 1 M MgCl2 system can be attributed to the dual-ion (de-)intercalation mechanism of MgCl3− and Mg2+, facilitated by the suppression of proton insertion. The battery performance was further evaluated at higher current densities ranging from 0.25 to 5 A g−1. Lower discharge voltages are displayed at higher specific currents, but the battery can still support a voltage plateau of 2.4 to 1.9 V and a discharge capacity of 100 mA·hour g−1 between 2.4 and 1.6 V at a current rate as high as 5 A g−1. A coulombic efficiency of up to 95% can be achieved at 0.25 A g−1 (Fig. 5, C and D). At lower rates, the battery capacity is even higher, reaching up to 220 mA·hour g−1 at 0.025 A g−1 (fig. S18, A and B). The battery also demonstrates impressive long-term cyclic stability, with a capacity retention rate of 88% after 900 cycles at 1 A g−1 and slight drop in voltage (Fig. 5E and fig. S18C).

Fig. 5. Electrochemical performance of the full battery.

(A) Schematic illustration of the battery mechanism with Mg metal anode, MgCl2-PEO electrolyte, and CuHCF cathode. (B) Battery discharge profiles at 0.25 A g−1 and the corresponding mechanisms. (C) Galvanostatic discharge-charge curves at various current densities. (D) Rate performance including specific capacity and coulombic efficiency. (E) Long-term battery cycling stability at 1 A g−1. (F) Performance comparison with other rechargeable Mg batteries, including QSMBs (39, 69, 70), NAMBs (5, 71–74), and AMBs (18–20, 23, 75, 76). The corresponding C-rates and capacity retention of each work are tabulated in table S6.

Figure 5F and table S6 compare the performance of this work with other rechargeable Mg-ion batteries in literature, including other QSMBs, AMBs, and NAMBs. This QSMB exhibits a higher voltage plateau that is almost double that of traditional AMBs and a cycling stability that is longer than most NAMBs. Among the few QSMBs reported to date, the average voltage outputs are generally low (~1.0 V) and the discharge capacities remain below 100 mA·hour g−1 (39, 69, 70). One of the most notable works present a Mg/Mo6S8 battery with an all-solid-state Mg(BH4)2/PEO electrolyte with MgO as filler material, exhibiting an average discharge voltage of 1.0 V and a capacity of 90 mA·hour g−1 over 150 cycles (69). Another Mg/Mo6S8 battery with a polytetrahydrofuran-borate–based gel polymer electrolyte (PTB@GF-GPE) displays an average discharge voltage of 1.0 V and a specific capacity of 74 mA·hour g−1 over 250 cycles at 0.06 A g−1 (39). In contrast, the battery cell in this work demonstrates one of the highest performances compared to other QSMBs. Benefiting from a Mg metal anode and the dual Mg-ion storage mechanism, the voltage output of this QSMB surpasses both AMBs and NAMBs, as well as other aqueous multivalent metal ion batteries like Zn-ion batteries and Al-ion batteries (table S7). Compared to our previous AMB with a “water-in-salt” electrolyte (23), this QSMB demonstrates exceptional increase in performance, particularly in specific capacity (4.8 times higher) and energy density (5.0 times higher). Without using ultrahigh salt concentrations, this work illustrates a cost-effective method to deliver superior battery performance by advanced electrolyte design.

Extreme environmental tolerance

The QSMB also demonstrates excellent tolerance in extreme operating conditions like subzero temperature, high pressure, and fire. While traditional Li-ion batteries suffer from reduced power output and permanent damage at freezing temperatures in colder climates, this battery performs equally well at −22°C compared to room temperature, with no signs of performance degradation even after 900 cycles, or 25 days of cycling, at 0.5 A g−1 (Fig. 6, A and B). This stems from the hydrogen bond anchoring effect of PEO, which effectively suppresses the freezing temperature in the aqueous electrolyte (77), and thereby sustains ionic conduction to maintain its high performance. In addition, the QSMB exhibits strong resistance to high pressure loading and successfully lights up a light-emitting diode (LED) at 4 MPa (Fig. 6C). Moreover, the aqueous quasi-solid-state electrolyte is fire resistant, presenting a safer alternative to the organic electrolytes used in conventional Li-ion batteries. Flammability tests show that an ignited cotton swab becomes extinguished when in contact with MgCl2-PEO, while the commercial LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate/diethyl carbonate becomes instantly ignited (Fig. 6D and movies S1 and S2). The antifreezing, pressure-resistant, and nonflammability properties of this QSMB build a strong foundation for a practical, robust, and safe battery technology that may enable a wide range of commercial applications in the future.

Fig. 6. Low-temperature, pressure, and flammability tests of the QSMB.

(A) Galvanostatic cycling curves of the battery at room temperature and at −22°C. (B) Long-term battery cycling stability at −22°C at 0.5 A g−1. (C) LED bulb lit up by the battery under a high pressure of 4 MPa. (D) Images of the flammable organic Li-ion electrolyte and nonflammable MgCl2-PEO electrolyte. See movies S1 and S2 for the flammability test.

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this study is to demonstrate the storage of multivalent metal ions at the cathode. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation of the reversibility of the Mg anode falls beyond the scope of this work. Nonetheless, to provide a more comprehensive study of the feasibility of this quasi-solid-state Mg-ion system, the reversibility of the anode has been demonstrated using electrochemical tests of the stripping and plating potentials and the cyclability of Mg symmetrical cells (fig. S19, A to C). This system exhibits a high coulombic efficiency of 94% (fig. S19D). Focused ion beam–SEM characterization of the anode surface shows that this high reversibility originates from the conversion of the passivation film into a conductive metal-oxide interphase, which has been studied in detail in our previous report of a water-confined MgCl2 system (fig. S19, E and F) (23). The hydrogen bond anchoring effect of PEO not only facilitates high-voltage dual Mg-ion storage at the cathode but also contributes to reversible Mg stripping and plating at the anode. This also translates to the AlCl3-PEO system, which could also benefit from the Cl-induced dissolution and water restriction effects to dissolve and suppress Al passivation (fig. S20; see further discussion). However, note that the passivation of Mg is regulated in this quasi-solid-state electrolyte but not entirely eliminated. For instance, the battery’s capacity degradation is more rapid at elevated temperatures compared to room temperature because of a stronger tendency of electrolyte decomposition and water evaporation at high temperatures (fig. S21). While the outcomes of our research are encouraging, further refinement is necessary to enhance the electrochemical performance and operational life span of Mg metal–based batteries.

In this work, a strategic method of enhancing high-voltage Mg ion (de-)intercalation in a QSMB is revealed. Owing to the hydrogen bond anchoring ability of PEO, H+ insertion into the cathode is suppressed and dual MgCl3− and Mg2+ ion intercalation is facilitated. Compared to traditional AMBs, the QSMB exhibits a notably higher voltage plateau of 2.6 to 2.0 V, with a specific capacity of 120 mA·hour g−1 in the voltage range of 2.6 to 1.6 V at 0.25 A g−1. Compared to NAMBs, the semisolid electrolyte offers much faster diffusion kinetics with a high ionic conductivity of 1.24 mS cm−1. The battery also retains 88% of its capacity after 900 cycles at 1 A g−1, overcoming the instability issue commonly observed in NAMBs. In addition, the QSMB not only promotes the desired ion intercalation but also provides freeze tolerance down to −22°C. This study provides a rational strategy to design advanced electrolytes for high-voltage and low temperature–tolerant Mg-ion batteries, with potential applications in other multivalent metal ion batteries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials preparation

Mg foil (99.95% purity) with a thickness of 0.1 mm served as the anode material. CuHCF on carbon paper served as the cathode. The synthesis procedure of the cathode was described in our previous work (23). The MgCl2-PEO electrolyte was prepared by mixing magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2·6H2O) with PEO and deionized water at a MgCl2·6H2O:PEO:H2O mass ratio of 4:1:1. PEO with a structure of H─(O─CH2─CH2)n─OH (MWn = 2 × 106) was used. To ensure uniformity, the mixture was magnetically stirred under a hot water bath at 60°C overnight. After cooling down to room temperature, the resulting quasi-solid-state electrolyte was pressed into 1-mm-thick films for use. The ZnCl2-PEO and AlCl3-PEO electrolytes were also prepared using the same method and concentration. On the basis of our previous work, the MgCl2-WIS electrolyte was prepared by mixing MgCl2·6H2O with deionized water at a salt-to-water mass ratio of 25:1. It was then grounded to a slurry-like mixture using a pestle and mortar.

Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical tests were carried out in air at room temperature. Using an electrochemical workstation (CHI 760E), CV was performed at a series of scan rates using three-electrode cells consisting of the CuHCF cathode working electrode, a Pt counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl in saturated KCl as the reference electrode. The ESW was determined using three-electrode cells with Ti electrodes at a scan rate of 100 mV/s. The Mg/CuHCF full battery was housed in a poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) cell, where the solid-state MgCl2-PEO electrolyte was inserted between the Mg anode and the CuHCF cathode. Each electrode was connected to a piece of silver foil current collector. The full batteries were cycled at a series of current densities ranging from 0.25 to 5 A g−1 on a battery testing system (CT2001A, Wuhan Land). A cutoff discharge voltage of 1.6 V was selected to study the high-voltage region, which is the main operation range in practical applications.

For in situ OEMS experiments, the hydrogen evolution rate was measured during the in situ cycling of Mg symmetrical cells at 0.25 mA cm−2. A mass spectrometer (QMS 200, Stanford Research Systems) was used for sampling and analysis of the evolved gas, which was transferred from the electrochemical cell via Ar carrier gas (N5.0, Linde HKO) continuously. The calibration of the gas concentration was performed using a standard gas mixture of O2, CO2, CO, H2, and H2O (5000 parts per million each, balanced by Ar).

In situ EQCM experiments were carried out using CHI440C (Shanghai Chenhua) with a scan rate of 25 mV s−1. Mass change was measured during CV scans in a three-electrode cell with CuHCF coated on the quartz crystal working electrode, Pt as the counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl in saturated KCl as the reference electrode. The m/Q ratio is calculated as follows

| (1) |

| (2) |

where C is the calibration constant of the quartz crystal used, 1.34 × 10−9 g/Hz (78), and ∆f is the change in oscillation frequency of the crystal (in Hz), derived from the Sauerbrey equation. i and t are the current (in A) and duration (in s) respectively. The theoretical m/Q ratio is calculated as follows

| (3) |

where M is the molar mass of the ion species, n is the number of electrons per ion, qe is the elementary charge, 1.602 × 10−19 C, and NA is the Avogadro’s constant, 6.022 × 1023.

Materials characterization

A scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S-4800) equipped with an EDS detector (Oxford Instruments X-Max 80) was used to examine the microstructure and elemental mapping of the MgCl2-PEO electrolyte. Raman spectroscopy (Micro-Raman inVia, Renishaw) was used to characterize the composition of MgCl2-WIS and MgCl2-PEO with a 632.8-nm laser. FTIR was performed using the PerkinElmer Spectrum Two FT-IR Spectrometer. The 1H NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance III 600-MHz NMR spectrometer using deuterium oxide as the field frequency lock. The ionic conductivities of the electrolytes were measured using a conductivity bench meter (FiveEasy FE30). A high-resolution transmission electron microscope (FEI Tecnai G2) equipped with an EDS detector (Oxford Instruments X-Max 80T) was used to chemically probe the CuHCF cathode for elemental mapping.

XRD, XPS, and Raman characterization

In situ XRD (XRD, Rigaku SmartLab 9kW) and in situ Raman spectroscopy (Micro-Raman inVia, Renishaw, 632.8-nm laser) were performed on CuHCF during constant-voltage charge/discharge between 1.0 and 0 V versus Ag/AgCl. A specially designed three-electrode cell was used, where CuHCF ink was deposited on a 0.05-mm graphite sheet for characterization, while Pt and Ag/AgCl in saturated KCl served as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. Ex situ XPS (Thermo Fisher Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi) was also conducted on CuHCF samples at pristine, fully charged, half discharged, and fully discharged states. The CuHCF ink was dropped onto fluorine-doped tin oxide conductive glass and charged/discharged at a current density of 0.5 A g−1 in a three-electrode cell. The active material was then scraped off and centrifuged with a mixture of ethanol and deionized water three times to remove any electrolyte residue.

MD simulation

MD simulation was carried out with the Forcite module in the Accelrys Materials Studio software to compare the structure evolution of the MgCl2-WIS and MgCl2-PEO electrolytes. A previous MD study on a Li/PEO system was used as the main reference for the simulation procedure (79). The molecular model of MgCl2·6H2O was created according to the optimized geometry from the B3LYP/6-31G* DFT method as reported in a previous study (80). The molecular model of PEO consists of 30 chains. In a periodic unit of x × y × z = 36 × 36 × 36 Å3, the MgCl2·6H2O and PEO structures were combined at a mass ratio of 4:1 to generate the initial MgCl2-PEO system in the Amorphous Cell module, whereas PEO was omitted for the MgCl2-WIS system. After the models were established, energy minimization was carried out to avoid the overlap of atomic positions using an annealing procedure reported in (81). Each system was annealed for 5 cycles with an initial temperature of 300 K and a midcycle temperature of 800 K. Afterward, NPT simulations were conducted for 100 ps under P = 1 atm and T = 300 K, and NVT simulations were performed for 1 ns under T = 300 K. A time step of 1 fs was used for all calculations. The Nosé-Hoover thermostat was used for temperature control, while the Anderson barostat was used for pressure control. Ewald’s summation method was used for long-range Coulomb interaction. The Lennard-Jones model was used for short-range van der Waals forces.

DFT simulation

First-principles total energy calculations were performed using projector augmented wave method and the generalized gradient approximation with a parameterized exchange-correlation functional according to Perdew–Bruke–Ernzerhof (6), as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (7). An energy cutoff of 520 eV and a k-point density of 2π × 0.03 Å−1 in each direction adopting the Γ-centered Monkhorst-Pack scheme were chosen so that the total ground-state energies converge to 3 meV per formula unit. The electronic self-consistent iteration and ionic relaxation loop convergence criterion were set to 10−5 eV and 0.01 Å, respectively. The DFT-D3 was implemented to describe the effect of van der Waals interaction (8). The cubic CuHCF was used as a host for M (Mg2+ or H+) storage. Total energies for various M-vacancy configurations were calculated by removing M atoms from the M2Cu[Fe(CN)6] structures and distributing the ensuing vacancies using different volume-sized supercells (9). The formation energy for a given M-vacancy arrangement with composition a (0 < a < 1) in M2aCu[Fe(CN)6] is defined as

| (4) |

The open-circuit voltage curve was obtained by calculating the average voltage over parts of the M composition domain. The charge/discharge processes of M2Cu[Fe(CN)6] comply with the following half-cell reaction versus Mg/Mg2+ or H/H+

| (5) |

Thus, neglecting the volume, pressure, and entropy effects, the average voltage of M2aCu[Fe(CN)6] in the concentration range of 2a1 < 2a < 2a2 can be estimated as

| (6) |

where , , and EM are the energies of , , and M, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y.-C. Lu and Z. Liang of the Chinese University of Hong Kong for providing the OEMS instrument, and for assisting with the OEMS experiment and subsequent data processing, respectively. We thank M. Leung and J. Zhou of the City University of Hong Kong for providing support on XPS characterization tests. We also thank the University Research Facility in Chemical and Environmental Analysis (UCEA) of Hong Kong Polytechnic University for technical support.

Funding: The authors would like to acknowledge the CRF grant of the Hong Kong Research Grant Council (C5031-20G) and the SZ-HK-Macau Technology Research Programme (Type C, SGDX20210823103537038) for partial grant support to this project. Publication was made possible in part by support from the HKU Libraries Open Access Author Fund sponsored by the HKU Libraries.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: K.W.L., W.P., and Y.W. Methodology: K.W.L. and W.P. Data analysis: K.W.L., W.P., S.L., X.Z., J.X., H.W., and Y.Z. Simulation: K.W.L., X.Y., J.M., and Y.C. Writing and editing: K.W.L., W.P., Y.W., Y.C., J.X., H.W., and D.Y.C.L.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The data can be provided by the authors pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement. Requests for the data should be submitted to ycleung@hku.hk.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S21

Tables S1 to S7

Legends for movies S1 and S2

References

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 to S2

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.X. Liu, A. Du, Z. Guo, C. Wang, X. Zhou, J. Zhao, F. Sun, S. Dong, G. Cui, Uneven stripping behavior, an unheeded killer of Mg anodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2201886 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Y. Zhang, J. Li, W. Zhao, H. Dou, X. Zhao, Y. Liu, B. Zhang, X. Yang, Defect-free metal–organic framework membrane for precise ion/solvent separation toward highly stable magnesium metal anode. Adv. Mater. 34, 2108114 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Y. Sun, Y. Wang, L. Jiang, W. Wang, D. Dong, J. Fan, Y.-C. Lu, Non-nucleophilic electrolyte with non-fluorinated hybrid-solvents for long-life magnesium metal batteries. Energ. Environ. Sci. 16, 265–274 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.H. Dong, O. Tutusaus, Y. Liang, Y. Zhang, Z. Lebens-Higgins, W. Yang, R. Mohtadi, Y. Yao, High-power Mg batteries enabled by heterogeneous enolization redox chemistry and weakly coordinating electrolytes. Nat. Energy 5, 1043–1050 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.S.-B. Son, T. Gao, S. P. Harvey, K. X. Steirer, A. Stokes, A. Norman, C. Wang, A. Cresce, K. Xu, C. Ban, An artificial interphase enables reversible magnesium chemistry in carbonate electrolytes. Nat. Chem. 10, 532–539 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.W. Zhang, Q. Zhao, Y. Hou, Z. Shen, L. Fan, S. Zhou, Y. Lu, L. A. Archer, Dynamic interphase–mediated assembly for deep cycling metal batteries. Sci. Adv. 7, eabl3752 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.I. Huang, Y. Zhang, H. M. Arafa, S. Li, A. Vazquez-Guardado, W. Ouyang, F. Liu, S. Madhvapathy, J. W. Song, A. Tzavelis, High performance dual-electrolyte magnesium–iodine batteries that can harmlessly resorb in the environment or in the body. Energ. Environ. Sci. 15, 4095–4108 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.D. Aurbach, Z. Lu, A. Schechter, Y. Gofer, H. Gizbar, R. Turgeman, Y. Cohen, M. Moshkovich, E. Levi, Prototype systems for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Nature 407, 724–727 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.H. Zhang, L. Qiao, H. Kühnle, E. Figgemeier, M. Armand, G. G. Eshetu, From lithium to emerging mono- and multivalent-cation-based rechargeable batteries: Non-aqueous organic electrolyte and interphase perspectives. Energ. Environ. Sci. 16, 11–52 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 10.A. Du, Z. Zhang, H. Qu, Z. Cui, L. Qiao, L. Wang, J. Chai, T. Lu, S. Dong, T. Dong, H. Xu, X. Zhou, G. Cui, An efficient organic magnesium borate-based electrolyte with non-nucleophilic characteristics for magnesium–sulfur battery. Energ. Environ. Sci. 10, 2616–2625 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Y. Sun, Q. Zou, Y. C. Lu, Fast and reversible four-electron storage enabled by ethyl viologen for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1903002 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.J. Luo, S. He, T. L. Liu, Tertiary Mg/MgCl2/AlCl3 inorganic Mg2+ electrolytes with unprecedented electrochemical performance for reversible Mg deposition. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1197–1202 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.B. J. Kwon, L. Yin, H. Park, P. Parajuli, K. Kumar, S. Kim, M. Yang, M. Murphy, P. Zapol, C. Liao, T. T. Fister, R. F. Klie, J. Cabana, J. T. Vaughey, S. H. Lapidus, B. Key, High voltage Mg-ion battery cathode via a solid solution Cr–Mn spinel oxide. Chem. Mater. 32, 6577–6587 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 14.D. Chao, W. Zhou, F. Xie, C. Ye, H. Li, M. Jaroniec, S.-Z. Qiao, Roadmap for advanced aqueous batteries: From design of materials to applications. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba4098 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Q. Fu, X. Wu, X. Luo, S. Indris, A. Sarapulova, M. Bauer, Z. Wang, M. Knapp, H. Ehrenberg, Y. Wei, S. Dsoke, High-voltage aqueous Mg-ion batteries enabled by solvation structure reorganization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2110674 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Z. Huang, T. Wang, X. Li, H. Cui, G. Liang, Q. Yang, Z. Chen, A. Chen, Y. Guo, J. Fan, C. Zhi, Small-dipole-molecule-containing electrolytes for high-voltage aqueous rechargeable batteries. Adv. Mater. 34, e2106180 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.X. Li, X. Wang, L. Ma, W. Huang, Solvation structures in aqueous metal-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2202068 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 18.F. Wang, X. Fan, T. Gao, W. Sun, Z. Ma, C. Yang, F. Han, K. Xu, C. Wang, High-voltage aqueous magnesium ion batteries. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 1121–1128 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.L. Chen, J. Bao, X. Dong, D. Truhlar, Y. Wang, C. Wang, Y. Xia, Aqueous Mg-ion battery based on polyimide anode and prussian blue cathode. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 1115–1121 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20.H. Zhang, K. Ye, K. Zhu, R. Cang, J. Yan, K. Cheng, G. Wang, D. Cao, High-energy-density aqueous magnesium-ion battery based on a carbon-coated FeVO4 anode and a Mg-OMS-1 cathode. Chem. A Eur. J. 23, 17118–17126 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.T. Sun, H. Du, S. Zheng, Z. Tao, Inverse-spinel Mg2MnO4 material as cathode for high-performance aqueous magnesium-ion battery. J. Power Sources 515, 230643 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Y. Tang, X. Li, H. Lv, W. Wang, Q. Yang, C. Zhi, H. Li, High-energy aqueous magnesium hybrid full batteries enabled by carrier-hosting potential compensation. Angew. Chem. 133, 5503–5512 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.K. W. Leong, W. Pan, Y. Wang, S. Luo, X. Zhao, D. Y. Leung, Reversibility of a high-voltage, Cl–regulated, aqueous Mg metal battery enabled by a water-in-salt electrolyte. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 2657–2666 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Z. Liu, W. Zhou, J. He, H. Chen, R. Zhang, Q. Wang, Y. Wang, Y. Yan, Y. Chen, Binder-free MnO2 as a high rate capability cathode for aqueous magnesium ion battery. J. Alloys Compd. 869, 159279 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Y. Zhang, G. Liu, C. Zhang, Q. Chi, T. Zhang, Y. Feng, K. Zhu, Y. Zhang, Q. Chen, D. Cao, Low-cost MgFexMn2-xO4 cathode materials for high-performance aqueous rechargeable magnesium-ion batteries. J. Chem. Eng. 392, 123652 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 26.A. I. Komayko, S. V. Ryazantsev, I. A. Trussov, N. A. Arkharova, D. E. Presnov, E. E. Levin, V. A. Nikitina, The misconception of Mg2+ insertion into prussian blue analogue structures from aqueous solution. ChemSusChem 14, 1574–1585 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Z. Liu, X. Li, J. He, Q. Wang, D. Zhu, Y. Yan, Y. Chen, Is proton a charge carrier for δ-MnO2 cathode in aqueous rechargeable magnesium-ion batteries? J. Energy Chem. 68, 572–579 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Q. Pan, R. Dong, H. Lv, X. Sun, Y. Song, X.-X. Liu, Fundamental understanding of the proton and zinc storage in vanadium oxide for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Chem. Eng. 419, 129491 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 29.V. Verma, S. Kumar, W. Manalastas Jr., M. Srinivasan, Undesired reactions in aqueous rechargeable zinc ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 1773–1785 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30.J. Xie, Z. Liang, Y.-C. Lu, Molecular crowding electrolytes for high-voltage aqueous batteries. Nat. Mater. 19, 1006–1011 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D. Dong, J. Xie, Z. Liang, Y.-C. Lu, Tuning intermolecular interactions of molecular crowding electrolyte for high-performance aqueous batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 123–130 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.K.-I. Kim, Q. Guo, L. Tang, L. Zhu, C. Pan, C.-H. Chang, J. Razink, M. M. Lerner, C. Fang, X. Ji, Reversible insertion of Mg-Cl superhalides in graphite as a cathode for aqueous dual-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 19924–19928 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.C. Yang, Z. Pu, Z. Jiang, X. Gao, K. Wang, S. Wang, Y. Chai, Q. Li, X. Wu, Y. Xiao, H2O-boosted Mg—proton collaborated energy storage for rechargeable Mg-metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2201718 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 34.M. Z. Jora, M. V. Cardoso, E. Sabadini, Dynamical aspects of water-poly (ethylene glycol) solutions studied by 1H NMR. J. Mol. Liq. 222, 94–100 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35.F. C. Lightstone, E. Schwegler, R. Q. Hood, F. Gygi, G. Galli, A first principles molecular dynamics simulation of the hydrated magnesium ion. Chem. Phys. Lett. 343, 549–555 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 36.S. Kurapati, S. S. Gunturi, K. J. Nadella, H. Erothu, Novel solid polymer electrolyte based on PMMA: CH3COOLi effect of salt concentration on optical and conductivity studies. Polym. Bull. 76, 5463–5481 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Y.-C. Jung, S.-M. Lee, J.-H. Choi, S. S. Jang, D.-W. Kim, All solid-state lithium batteries assembled with hybrid solid electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, A704–A710 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 38.D. H. Kim, M. Y. Kim, S. H. Yang, H. M. Ryu, H. Y. Jung, H.-J. Ban, S.-J. Park, J. S. Lim, H.-S. Kim, Fabrication and electrochemical characteristics of NCM-based all-solid lithium batteries using nano-grade garnet Al-LLZO powder. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 71, 445–451 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 39.A. Du, H. Zhang, Z. Zhang, J. Zhao, Z. Cui, Y. Zhao, S. Dong, L. Wang, X. Zhou, G. Cui, A crosslinked polytetrahydrofuran-borate-based polymer electrolyte enabling wide-working-temperature-range rechargeable magnesium batteries. Adv. Mater. 31, 1805930 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.H. O. Ford, L. C. Merrill, P. He, S. P. Upadhyay, J. L. Schaefer, Cross-linked ionomer gel separators for polysulfide shuttle mitigation in magnesium–sulfur batteries: Elucidation of structure–property relationships. Macromolecules 51, 8629–8636 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Y. Zhan, W. Zhang, B. Lei, H. Liu, W. Li, Recent development of Mg ion solid electrolyte. Front. Chem. 8, 125 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.S. Bi, Y. Zhang, S. Deng, Z. Tie, Z. Niu, Proton-assisted aqueous manganese-ion battery chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 134, e202200809 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.T. Sun, H. Du, S. Zheng, J. Shi, X. Yuan, L. Li, Z. Tao, Bipolar organic polymer for high performance symmetric aqueous proton battery. Small Methods 5, 2100367 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.W. Pan, Y. Wang, Y. Zhang, H. Y. H. Kwok, M. Wu, X. Zhao, D. Y. C. Leung, A low-cost and dendrite-free rechargeable aluminium-ion battery with superior performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 17420–17425 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 45.W. Pan, Y. Zhao, J. Mao, Y. Wang, X. Zhao, K. W. Leong, S. Luo, X. Liu, H. Wang, J. Xuan, High-energy SWCNT cathode for aqueous Al-ion battery boosted by multi-ion intercalation chemistry. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2101514 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 46.P. Prabhu, R. S. Babu, S. S. Narayanan, Electrochemical determination of l-vanillin using copper hexacyanoferrate film modified gold nanoparticle graphite-wax composite electrode. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 30, 9955–9963 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.W. Wang, H. Wang, J. Zhao, X. Wang, C. Xiong, L. Song, R. Ding, P. Han, W. Li, Self-healing performance and corrosion resistance of graphene oxide–mesoporous silicon layer–nanosphere structure coating under marine alternating hydrostatic pressure. J. Chem. Eng. 361, 792–804 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Y. Wu, K. Zhang, S. Chen, Y. Liu, Y. Tao, X. Zhang, Y. Ding, S. Dai, Proton inserted manganese dioxides as a reversible cathode for aqueous Zn-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 319–327 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Y. Wu, Y. Lin, J. Xu, Synthesis of Ag–Ho, Ag–Sm, Ag–Zn, Ag–Cu, Ag–Cs, Ag–Zr, Ag–Er, Ag–Y and Ag–Co metal organic nanoparticles for UV-Vis-NIR wide-range bio-tissue imaging. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 18, 1081–1091 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Y. An, Y. Liu, S. Tan, F. Xiong, X. Liao, Q. An, Dual redox groups enable organic cathode material with a high capacity for aqueous zinc-organic batteries. Electrochim. Acta 404, 139620 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 51.N. Dwivedi, R. J. Yeo, N. Satyanarayana, S. Kundu, S. Tripathy, C. S. Bhatia, Understanding the role of nitrogen in plasma-assisted surface modification of magnetic recording media with and without ultrathin carbon overcoats. Sci. Rep. 5, 7772 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.E. Laboratories, E. Scientific, Ed. (2022).

- 53.J. M. Arias, M. E. Tuttolomondo, S. B. Díaz, A. B. Altabef, FTIR and Raman analysis of l-cysteine ethyl ester HCl interaction with dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine in anhydrous and hydrated states. J. Raman Spectrosc. 46, 369–376 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 54.H. E. Hussein, H. Amari, B. G. Breeze, R. Beanland, J. V. Macpherson, Controlling palladium morphology in electrodeposition from nanoparticles to dendrites via the use of mixed solvents. Nanoscale 12, 21757–21769 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.X. Rao, A. Abou Hassan, C. Guyon, M. Zhang, S. Ognier, M. Tatoulian, Plasma polymer layers with primary amino groups for immobilization of nano- and microparticles. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 40, 589–606 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.C. Gu, L. Yang, M. Wang, N. Zhou, L. He, Z. Zhang, M. Du, A bimetallic (Cu-Co) Prussian Blue analogue loaded with gold nanoparticles for impedimetric aptasensing of ochratoxin a. Microchim. Acta 186, 343 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Y. Wang, J. Bo, Z. Chi, L. Wang, J. Li, Engineered nitrogen-doped hollow carbon nanospheres adhered by carbon nanotubes for capacitive potassium-ion storage. Appl. Surf. Sci. 557, 149833 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 58.R. Trócoli, F. La Mantia, An aqueous zinc-ion battery based on copper hexacyanoferrate. ChemSusChem 8, 481–485 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Z. Li, K. Xiang, W. Xing, W. C. Carter, Y. M. Chiang, Reversible aluminum-ion intercalation in prussian blue analogs and demonstration of a high-power aluminum-ion asymmetric capacitor. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1401410 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 60.M. Xu, J. P. Larentzos, M. Roshdy, L. J. Criscenti, H. C. Allen, Aqueous divalent metal–nitrate interactions: Hydration versus ion pairing. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 4793–4801 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.S. Behera, P. Jena, Stability and spectroscopic properties of singly and doubly charged anions. J. Phys. Chem. A 116, 5604–5617 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.K. I. Kim, L. Tang, J. M. Muratli, C. Fang, X. Ji, A graphite∥PTCDI aqueous dual-ion battery. ChemSusChem 15, e202102394 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.J. G. Connell, B. Genorio, P. P. Lopes, D. Strmcnik, V. R. Stamenkovic, N. M. Markovic, Tuning the reversibility of Mg anodes via controlled surface passivation by H2O/Cl–in organic electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 28, 8268–8277 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 64.L. C. Merrill, J. L. Schaefer, The influence of interfacial chemistry on magnesium electrodeposition in non-nucleophilic electrolytes using sulfone-ether mixtures. Front. Chem. 7, 194 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.M. Adil, A. Sarkar, A. Roy, M. R. Panda, A. Nagendra, S. Mitra, Practical aqueous calcium-ion battery full-cells for future stationary storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 11489–11503 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Z. Jia, B. Wang, Y. Wang, Copper hexacyanoferrate with a well-defined open framework as a positive electrode for aqueous zinc ion batteries. Mater. Chem. Phys. 149–150, 601–606 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 67.W. Pan, Y. Wang, X. Zhao, Y. Zhao, X. Liu, J. Xuan, H. Wang, D. Y. C. Leung, High-performance aqueous Na–Zn hybrid ion battery boosted by “water-in-gel” electrolyte. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008783 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 68.R. Mažeikienė, G. Niaura, A. Malinauskas, SERS spectroelectrochemical study of electrode processes at copper hexacyanoferrate modified electrode. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 181, 200–207 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Y. Shao, N. N. Rajput, J. Hu, M. Hu, T. Liu, Z. Wei, M. Gu, X. Deng, S. Xu, K. S. Han, J. Wang, Z. Nie, G. Li, K. R. Zavadil, J. Xiao, C. Wang, W. A. Henderson, J.-G. Zhang, Y. Wang, K. T. Mueller, J. Liu, Nanocomposite polymer electrolyte for rechargeable magnesium batteries. Nano Energy 12, 750–759 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 70.O. Chusid, Y. Gofer, H. Gizbar, Y. Vestfrid, E. Levi, D. Aurbach, I. Riech, Solid-state rechargeable magnesium batteries. Adv. Mater. 15, 627–630 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 71.F. Liu, Y. Liu, X. Zhao, X. Liu, L.-Z. Fan, Pursuit of a high-capacity and long-life Mg-storage cathode by tailoring sandwich-structured MXene@ carbon nanosphere composites. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 16712–16719 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 72.H. Dong, Y. Liang, O. Tutusaus, R. Mohtadi, Y. Zhang, F. Hao, Y. Yao, Directing Mg-storage chemistry in organic polymers toward high-energy Mg batteries. Joule 3, 782–793 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 73.B. Pan, J. Huang, Z. Feng, L. Zeng, M. He, L. Zhang, J. T. Vaughey, M. J. Bedzyk, P. Fenter, Z. Zhang, A. K. Burrell, C. Liao, Polyanthraquinone-based organic cathode for high-performance rechargeable magnesium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1600140 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 74.T. Bančič, J. Bitenc, K. Pirnat, A. K. Lautar, J. Grdadolnik, A. R. Vitanova, R. Dominko, Electrochemical performance and redox mechanism of naphthalene-hydrazine diimide polymer as a cathode in magnesium battery. J. Power Sources 395, 25–30 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Z. Zhang, Y. Li, G. Zhao, L. Zhu, Y. Sun, F. Besenbacher, M. Yu, Rechargeable Mg-ion full battery system with high capacity and high rate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 40451–40459 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.H. Zhang, D. Cao, X. Bai, High rate performance of aqueous magnesium-ion batteries based on the δ-MnO2@ carbon molecular sieves composite as the cathode and nanowire VO2 as the anode. J. Power Sources 444, 227299 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 77.S. Liu, R. Zhang, J. Mao, Y. Zhao, Q. Cai, Z. Guo, From room temperature to harsh temperature applications: Fundamentals and perspectives on electrolytes in zinc metal batteries. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn5097 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.I. CH Instruments Inc., 400C Series Time-resolved Electrochemical Quartz Crystal Microbalance (EQCM). https:/chinstruments.com/chi400.shtml [accessed 11 February 2023].

- 79.T. Mabuchi, K. Nakajima, T. Tokumasu, Molecular dynamics study of ion transport in polymer electrolytes of all-solid-state Li-ion batteries. Micromachines 12, 1012 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.X. Song, G. Liu, Z. Sun, J. Yu, Comparative study on the molecular and electronic structure of MgCl2· 6 NH3 and MgCl2· 6H2O. Asia Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 7, 221–226 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 81.T. Mabuchi, T. Tokumasu, Effect of bound state of water on hydronium ion mobility in hydrated Nafion using molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 141, 104904 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Q. Sun, C. Qin, Raman OH stretching band of water as an internal standard to determine carbonate concentrations. Chem. Geol. 283, 274–278 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 83.M. Sbroscia, A. Sodo, F. Bruni, T. Corridoni, M. A. Ricci, OH stretching dynamics in hydroxide aqueous solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 4077–4082 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.H.-C. Chen, H.-C. Lin, H.-H. Chen, F.-D. Mai, Y.-C. Liu, C.-M. Lin, C.-C. Chang, H.-Y. Tsai, C.-P. Yang, Innovative strategy with potential to increase hemodialysis efficiency and safety. Sci. Rep. 4, 4425 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.N. Ghosh, S. Roy, A. Bandyopadhyay, J. A. Mondal, Vibrational Raman spectroscopy of the hydration shell of ions. Liquids 3, 19–39 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 86.Q. Sun, The single donator-single acceptor hydrogen bonding structure in water probed by Raman spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 054507 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Q. Dou, S. Lei, D.-W. Wang, Q. Zhang, D. Xiao, H. Guo, A. Wang, H. Yang, Y. Li, S. Shi, Safe and high-rate supercapacitors based on an “acetonitrile/water in salt” hybrid electrolyte. Energ. Environ. Sci. 11, 3212–3219 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 88.M. Peng, L. Wang, L. Li, Z. Peng, X. Tang, T. Hu, K. Yuan, Y. Chen, Molecular crowding agents engineered to make bioinspired electrolytes for high-voltage aqueous supercapacitors. EScience 1, 83–90 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 89.R. Li, Z. Jiang, S. Shi, H. Yang, Raman spectra and 17O NMR study effects of CaCl2 and MgCl2 on water structure. J. Mol. Struct. 645, 69–75 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 90.D. J. Brooks, B. V. Merinov, W. A. Goddard III, B. Kozinsky, J. Mailoa, Atomistic description of ionic diffusion in PEO–LiTFSI: Effect of temperature, molecular weight, and ionic concentration. Macromolecules 51, 8987–8995 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 91.C. Cendra, A. Giovannitti, A. Savva, V. Venkatraman, I. McCulloch, A. Salleo, S. Inal, J. Rivnay, Role of the anion on the transport and structure of organic mixed conductors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1807034 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 92.E. Ruiz-Hitzky, P. Aranda, Polymer-salt intercalation complexes in layer silicates. Adv. Mater. 2, 545–547 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 93.X. Gong, H. Xu, M. Zhang, X. Cheng, Y. Wu, H. Zhang, H. Yan, Y. Dai, J.-C. Zheng, 2.4 V high performance supercapacitors enabled by polymer-strengthened 3 m aqueous electrolyte. J. Power Sources 505, 230078 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 94.S. Liu, G. L. Pan, G. R. Li, X. P. Gao, Copper hexacyanoferrate nanoparticles as cathode material for aqueous Al-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 959–962 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 95.C. D. Wessells, R. A. Huggins, Y. Cui, Copper hexacyanoferrate battery electrodes with long cycle life and high power. Nat. Commun. 2, 550 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.R. J. Capwell, Raman spectra of crystalline and molten MgCl2. Chem. Phys. Lett. 12, 443–446 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 97.E. Shi, A. Wang, Z. Ling, MIR, VNIR, NIR, and Raman spectra of magnesium chlorides with six hydration degrees: Implication for Mars and Europa. J. Raman Spectrosc. 51, 1589–1602 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 98.D. Aurbach, Y. Gofer, J. Langzam, The correlation between surface chemistry, surface morphology, and cycling efficiency of lithium electrodes in a few polar aprotic systems. J. Electrochem. Soc. 136, 3198–3205 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 99.L. Ma, M. A. Schroeder, T. P. Pollard, O. Borodin, M. S. Ding, R. Sun, L. Cao, J. Ho, D. R. Baker, C. Wang, K. Xu, Critical factors dictating reversibility of the zinc metal anode. Energy Environ. Mater. 3, 516–521 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 100.H. D. Yoo, Y. Liang, Y. Li, Y. Yao, High areal capacity hybrid magnesium–lithium-ion battery with 99.9% coulombic efficiency for large-scale energy storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 7001–7007 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.S. D. Pu, C. Gong, X. Gao, Z. Ning, S. Yang, J.-J. Marie, B. Liu, R. A. House, G. O. Hartley, J. Luo, P. G. Bruce, A. W. Robertson, Current-density-dependent electroplating in Ca electrolytes: From globules to dendrites. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 2283–2290 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 102.M. Jäckle, K. Helmbrecht, M. Smits, D. Stottmeister, A. Groß, Self-diffusion barriers: Possible descriptors for dendrite growth in batteries? Energ. Environ. Sci. 11, 3400–3407 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 103.R. Attias, M. Salama, B. Hirsch, Y. Goffer, D. Aurbach, Anode-electrolyte interfaces in secondary magnesium batteries. Joule 3, 27–52 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 104.Y. Liang, H. Dong, D. Aurbach, Y. Yao, Current status and future directions of multivalent metal-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 5, 646–656 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 105.M. Jiang, C. Fu, P. Meng, J. Ren, J. Wang, J. Bu, A. Dong, J. Zhang, W. Xiao, B. Sun, Challenges and strategies of low-cost aluminum anodes for high-performance Al-based batteries. Adv. Mater. 34, 2102026 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.T. Liang, R. Hou, Q. Dou, H. Zhang, X. Yan, The applications of water-in-salt electrolytes in electrochemical energy storage devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2006749 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 107.T. Dong, K. L. Ng, Y. Wang, O. Voznyy, G. Azimi, Solid electrolyte interphase engineering for aqueous aluminum metal batteries: A critical evaluation. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100077 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 108.T. E. Sutto, Hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions of ionic liquids and polymers in solid polymer gel electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154, P101 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 109.J. Jeon, H. Lee, J.-H. Choi, M. Cho, Modeling and simulation of concentrated aqueous solutions of LiTFSI for battery applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 124, 11790–11799 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 110.H. Liu, E. Maginn, An MD study of the applicability of the walden rule and the Nernst–Einstein model for ionic liquids. ChemPhysChem 13, 1701–1707 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Y. Zhang, E. J. Maginn, Water-in-salt LiTFSI aqueous electrolytes (2): Transport properties and Li+ dynamics based on molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 125, 13246–13254 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.A. Kisliuk, V. Bocharova, I. Popov, C. Gainaru, A. P. Sokolov, Fundamental parameters governing ion conductivity in polymer electrolytes. Electrochim. Acta 299, 191–196 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 113.F. Wieland, V. Bocharova, P. Münzner, W. Hiller, R. Sakrowski, C. Sternemann, R. Böhmer, A. P. Sokolov, C. Gainaru, Structure and dynamics of short-chain polymerized ionic liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 034903 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.J. Garcia-Jareno, C. Gabrielli, H. Perrot, Validation of the mass response of a quartz crystal microbalance coated with Prussian Blue film for ac electrogravimetry. Electrochem. Commun. 2, 195–200 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 115.S. Yagi, M. Fukuda, T. Ichitsubo, K. Nitta, M. Mizumaki, E. Matsubara, EQCM analysis of redox behavior of CuFe Prussian blue analog in mg battery electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, A2356–A2361 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 116.Q. Gou, H. Luo, Y. Zheng, Q. Zhang, C. Li, J. Wang, O. Odunmbaku, J. Zheng, J. Xue, K. Sun, M. Li, Construction of bio-inspired film with engineered hydrophobicity to boost interfacial reaction kinetics of aqueous zinc–ion batteries. Small 18, e2201732 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.H. Moon, R. Tatara, T. Mandai, K. Ueno, K. Yoshida, N. Tachikawa, T. Yasuda, K. Dokko, M. Watanabe, Mechanism of Li ion desolvation at the interface of graphite electrode and glyme–Li salt solvate ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 20246–20256 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 118.L. F. Wan, D. Prendergast, Ion-pair dissociation on α-MoO3 surfaces: Focus on the electrolyte–cathode compatibility issue in Mg batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 398–405 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 119.H. Zhang, K. Ye, K. Zhu, R. Cang, J. Yan, K. Cheng, G. Wang, D. Cao, The FeVO4·0.9H2O/graphene composite as anode in aqueous magnesium ion battery. Electrochim. Acta 256, 357–364 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 120.L. Kang, M. Cui, F. Jiang, Y. Gao, H. Luo, J. Liu, W. Liang, C. Zhi, Nanoporous CaCO3 coatings enabled uniform Zn stripping/plating for long-life zinc rechargeable aqueous batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 8, 1801090 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 121.Y. Zhu, J. Yin, X. Zheng, A.-H. Emwas, Y. Lei, O. F. Mohammed, Y. Cui, H. N. Alshareef, Concentrated dual-cation electrolyte strategy for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energ. Environ. Sci. 14, 4463–4473 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 122.Z. Guo, Y. Ma, X. Dong, J. Huang, Y. Wang, Y. Xia, An environmentally friendly and flexible aqueous zinc battery using an organic cathode. Angew. Chem. 130, 11911–11915 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.X. Xie, S. Liang, J. Gao, S. Guo, J. Guo, C. Wang, G. Xu, X. Wu, G. Chen, J. Zhou, Manipulating the ion-transfer kinetics and interface stability for high-performance zinc metal anodes. Energ. Environ. Sci. 13, 503–510 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 124.D. Wang, H. Lv, T. Hussain, Q. Yang, G. Liang, Y. Zhao, L. Ma, Q. Li, H. Li, B. Dong, T. Kaewmaraya, C. Zhi, A manganese hexacyanoferrate framework with enlarged ion tunnels and two-species redox reaction for aqueous Al-ion batteries. Nano Energy 84, 105945 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 125.C. Wu, S. Gu, Q. Zhang, Y. Bai, M. Li, Y. Yuan, H. Wang, X. Liu, Y. Yuan, N. Zhu, F. Wu, H. Li, L. Gu, J. Lu, Electrochemically activated spinel manganese oxide for rechargeable aqueous aluminum battery. Nat. Commun. 10, 73 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.S. Yang, C. Li, H. Lv, X. Guo, Y. Wang, C. Han, C. Zhi, H. Li, High-rate aqueous aluminum-ion batteries enabled by confined iodine conversion chemistry. Small Methods 5, 2100611 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S21

Tables S1 to S7

Legends for movies S1 and S2

References

Movies S1 to S2