Abstract

This study builds upon prior research on associations between moods, family functioning, and binge eating, using ecological momentary assessment to examine moderating effects of family functioning on associations between moods and binge eating. This study was conducted among a nonclinical sample of urban adolescents. Family functioning was assessed using five constructs adopted from the FACES-IV measure: ‘family cohesion,’ ‘family flexibility’ ‘family communication,’ ‘family satisfaction,’ and ‘family balance.’ Mood data was gathered using 13 items from a daily affect scale. Binge eating was assessed using two subscales from the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale—binge eating associated with ‘embarrassment’ (BE1), and binge eating associated with a sense of ‘loss of control’ (BE2). A multilevel modeling approach was employed to examine how associations between momentary moods and binge eating behaviors were moderated by family functioning. Results indicated that measures of negative affect, stress/frustration, and tiredness/boredom were significantly and positively associated with two measures of binge eating (BE1 and BE2; p values ≤ 0.05), and that multiple factors of family functioning buffered the positive predictive effects of moods on binge eating. Findings indicate the importance of inclusion of family functioning in the development of eating behavior interventions for adolescents.

Keywords: Family functioning, Moods, Adolescents, Binge eating, Ecological momentary assessment

Introduction

Binge eating (BE) is a harmful form of “out-of-control” eating which occurs in both healthy and overweight populations, but is more prevalent among overweight and weight-loss seeking populations. Some of the characteristics of BE include food consumption that occurs unusually fast, in the absence of hunger, alone due to feeling of embarrassment, and followed by feelings of uncomfortable fullness, disgust, depression, or guilt (APA, 2013). In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of BE is 2.0% among men, and 3.5% among women (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007). Among obese populations, those who self-report BE show greater feelings of ineffectiveness, stronger perfectionistic attitudes, more impulsivity, lower self-esteem, and less interoceptive awareness (De Zwaan, Mitchell, Seim, & Specker, 1994). While BE was defined as a disorder by psychiatrist Albert Stunkard (Stunkard, 1959), it was not until 2013 that the American Psychological Association (APA) recognized certain levels of BE as a clinical eating disorder [i.e. “binge eating disorder” (BED)] (Eating Disorders, 2017). BE continues to occur in non-treatment seeking and subclinical populations; depending on the severity and frequency of BE behaviors, diagnostic criterion for BED may be reached (APA, 2013). As a distinct form of disordered eating, BED is associated with demographic and psychological correlates (i.e. age, culture, gender, and dieting propensities) unique from those of other categories of disordered eating (Wilfley, Pike, & Striegel-Moore, 1997). In light of associations between eating disorders in adolescents and psychopathology in young adulthood, as well as between adolescent BE and adolescent obesity, a better understanding of the mechanisms that drive BE in adolescents is critical (Lewinsohn, Striegel-Moore, & Seeley, 2002).

Moods and family functioning associated with BE

A number of cross-sectional studies have examined associations among moods, family functioning, and BE, indicating that adults with BED show more negative patterns of everyday emotions (particularly those related to interpersonal aspects) (Zeeck, Stelzer, Linster, Joos, & Hartmann, 2011), that women with BED experience higher levels of negative moods on days of BE (Munsch, Meyer, Quartier, & Wilhelm, 2012), and that obese adults experience greater negative affect prior to BE episodes (Berg et al., 2015). Adolescents or families with one or more members with BED have been shown to have lower levels of family functioning, as measured by the Family Environment Scale (FES) (Hodges, Cochrane, & Brewerton, 1998), the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale (FACES) III (Leon, Fulkerson, Perry, & Dube, 1994; Tetzlaff, Schmidt, Brauhardt, & Hilbert, 2016), the FACES-IV (Laghi et al., 2016) and the Family Assessment Device (FAD) (Berge et al., 2014).

The stress-buffering effects model proposes that several forms of social support, including levels of perceived support from family members and relatives (Sandler, 1980; Kessler & Essex, 1982) reduce the effects of negative stressors on psychological and physical outcomes. It is hypothesized that this process takes place through the provision of protection against the negative psychological effects of stressors, reduction of perceptions of the importance of problems, and tranquilization of neuroendocrine responses to stressors (Cohen & Wills, 1985). We hypothesized an interaction effect that was consistent with the buffer interaction hypothesis of social support and stress (Cohen & Koenig, 2003; Cohen & Wills, 1985), by which social support provides a protective (i.e. buffering) effect against the effect of stressful events on a person’s well-being. The authors of this study hypothesized that family functioning would buffer (reduce) the effects of negative moods on BE—in short, by increasing the availability of coping resources which might serve as buffers against the effects of negative moods on BE. Cross-sectional research has been conducted on the main effects of moods on BE, (Zeeck et al., 2011), the main effects of family functioning on BE (Hodges et al., 1998; Leon et al., 1994; Tetzlaff et al., 2016; Laghi et al., 2016; Berge et al., 2014), and the mediating effects of moods on associations between interpersonal problems and BE (Elliott et al., 2010; Ivanova et al., 2015). While useful for some purposes, the validity of cross-sectional research suffers from issues including but not limited to recall bias. EMA research accounts for this limitation by providing real-time, repeated assessment, of constructs of interest. While one EMA study has been conducted on the main effects of moods on BE (Munsch et al., 2012; Berg et al., 2015), to the best of these authors’ knowledge no research to date has explored moderating effects of family functioning on relationships between moods and BE, among non-clinical participants.

Methods

The data in this study was taken from a primary study, the purpose for which was the examination of associations between momentary ‘cues’ (e.g. where students were, who they were with, etc.) with dietary habits. For a detailed description of procedures and measures used in the primary study, refer to Grenard and colleagues (Grenard et al., 2013). The participants, procedures, and measures used in this study are briefly described, in the section below.

Participants

This study included students recruited from schools located within 30-miles of an assessment site in San Dimas, CA; additional inclusion criteria were that schools had at least 25% of students eligible for free or reduced-cost lunches, at least 25% of students of Hispanic ethnicity, at most 25% of students of Asian ethnicity, and a minimum of 100 students who were enrolled. Following the distribution of 3000 flyers to eligible schools, 1423 students expressed interest in participation. This group was screened for age (i.e. 14–17 years old), proficiency in English (written and spoken), health status (i.e. ‘free of major illness’), treatment for obesity (i.e. ‘not taking medications or undergoing treatment for obesity’), and ability to provide transportation to the study site. After eligibility screening, 158 students were consented for participation. This group was 56.96% female, 43.04% male, 83.44% Hispanic, 16.56% Non-Hispanic, on average aged 15 (m = 15.13, sd = 2.27), and in the 72nd percentile of Body Mass Index (BMI) (m = 72.12, sd = 26.15). Approximately half of the participants in this sample had parents who had not finished high school. Based on baseline measurements of body mass index, 25% of the students in this sample were obese. Given that BE is more prevalent among overweight and obese populations (APA, 2013), the rate of obesity among this sample was an indicator of the appropriateness of this sample for this analysis. Six of the participants exhibited clinical-levels of BE (that is, these participants met diagnostic criterion for BED, based on their responses on the Stice Binge Eating Diagnostic Subscale, a subscale of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (Stice, Telch, & Rizvi, 2000)).

Procedures

At commencement of this study, participants read and signed assent forms, and parents read and signed consent forms. Consent forms were available in both English and in Spanish. After provision of consent, participants completed a series of baseline self-report measures programmed on laptop computers. Assessments of demographics, selected behaviors, and psychosocial variables were included in this battery. In addition, height and weight were directly measured using a calibrated stadiometer and a digital scale; each was measured three times and the mean of the three measurements was used as the final value. BMI was computed as the weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared. Afterward, participants were each given personal digital assistants (PDAs) and provided with instructions and training for using these devices for EMA data collection. During the seven-day period of data collection, participants completed three types of reports. The first two types were Eating Reports and Random Reports. The Eating Reports were reports of all instances of food/drink consumption, within 15 min of consumption. The Random Reports were reports of this same information, except that these reports were provided in response to prompts given at random times during each day: twice daily on school days (once per 3-h interval, between the hours of 3:00 pm–9:00 pm) and four times daily on non-school days (once per 3-h interval, between the hours of 9:00am–9:00 pm). In order to comply with schools’ requirements that students not interact with EMA devices during school hours, students were instructed that on school days they were not to complete reports between the hours of 8am–3 pm. In both the Eating Reports and the Random Reports, participants provided information on what food(s)/drink(s) were consumed, where consumption occurred, and which family influences, moods, activities, appetites/cravings, stress levels, food availability, and exercise levels surrounded its/their consumption. The third type of report was the Evening Report. This report was completed each evening, between the hours of 6:00 pm–11:45 pm. On this report, participants provided information on perceived levels of stress, and on availabilities of food in their homes throughout their days. These reports generated information for the primary study, from which data for the current study were taken. The current study only included selected information from the EMA reports.

Measures

Baseline survey data

Baseline survey data was collected on participants’ general health, eating behavior, and home environments. These data were collected using measures of socioeconomic status, acculturation, dietary consumption, family functioning, parenting style, family/friend support for dietary habits, household food availability, control over food intake, frequency/atmosphere/structure of family meals, pubertal development, physical activity, sedentary behavior, binge eating behavior, emotional/restrained/external eating, and perceived stress. The baseline data which were used in the current study were taken from the items on demographics and the items on family functioning.

Demographics

Demographic information included in the current study were gender, ethnicity, age, and obesity status. Data were coded as binary on all of these constructs: gender (either ‘male’ or ‘female’), ethnicity (either ‘Hispanic or Latino,’ or ‘not Hispanic or Latino,’) age (either ‘14–16’ or ‘17–18,’ based on reported birthdays, rounded down ages-in-years which participants would have reported), and obesity status. Obesity status was based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s definition of child obesity (i.e. being in the or over the 95th percentile).

Family functioning

Family functioning was measured using five scales taken from the FACES-IV package, and based on the Circumplex Model of Couple and Family Systems (Olson, Gorall, & Tiesel, 2009). According to the FACES-IV administration manual, normed score ranges and Cronbach alphas for these constructs are as follows: ‘Family Cohesion’ (Raw score: 7–35; percentile: 16th “very low” to 85th, “very high”; α = 0.864), ‘Family Flexibility’ (Raw score: 7–35; percentile: 16th “very low” to 85th, “very high”; α = 0.881), ‘Family Communication’ (Raw score: 10–50; percentile: 10th “very low” to 99th “very high”; α = 0.879), ‘Family Satisfaction’ (Raw score 10–50; percentile: 10th “very low” to 99th “very high”; α = 0.880), and ‘Family Balance’ (Range 0.683–2.220; α = 0.860).

All five FACES-IV constructs were included in the current study, and were scored on a continuous scale. The first two constructs—‘family cohesion’ and ‘family flexibility’—were measured using seven questions with five response options each; these questions were used to classify family cohesion on a scale of ‘somewhat connected’ to ‘very connected,’ and to classify ‘family flexibility’ on a scale of ‘somewhat flexible,’ to ‘very flexible.’ The second two constructs—‘family communication’ and ‘family satisfaction’—were measured using ten questions with five response options each; these questions were used to classify items on a scale of ‘very low’ to ‘very high.’ ‘Family balance’ was calculated as a ratio of perceived ‘balanced’ (or, perceived ‘functional’) behavior, to perceived ‘unbalanced’ (or, perceived ‘dysfunctional’) behavior, in a family system. More specifically, ‘balanced’ behavior was a family’s combined ‘cohesion’ and ‘flexibility’ scores, while ‘unbalanced’ behavior was a family’s combined ‘disengagement,’ ‘enmeshment,’ ‘rigidness,’ and ‘chaos’ scores. This ratio was used to classify ‘family balance’ on a scale of ‘unbalanced’ to ‘balanced.’ The means and standard deviations of scores achieved by participants on the above constructs, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of personal characteristics, family characteristics, momentary moods and binge eating behaviors. Descriptive statistics of moods and binge eating behaviors

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristics | ||

| Male | 68 | 43.04 |

| Female | 90 | 56.96 |

| Hispanic | 131 | 83.44 |

| Not hispanic | 26 | 16.56 |

| BMI percentile | 158 | 76.00 |

| Obeseb | 39 | 24.68 |

| Not obese | 119 | 75.32 |

| Mean | SD | |

| Agea | 15.13 | 2.27 |

| Family characteristics | ||

| Family balanced cohesion | 58.50 | 14.40 |

| Family balanced flexibility | 49.79 | 14.50 |

| Family communication | 48.87 | 26.09 |

| Family satisfaction | 29.46 | 20.92 |

| Family balancec (odds ratio) | 1.33 | 0.36 |

| Momentary moods (1–100) | ||

| Feeling tired | 44.47 | 37.22 |

| Feeling stressed | 22.69 | 30.33 |

| Feeling sad | 15.68 | 26.30 |

| Feeling relaxed | 55.33 | 32.56 |

| Feeling lonely | 12.33 | 24.15 |

| Feeling left-out | 8.40 | 18.89 |

| Feeling happy | 57.00 | 30.40 |

| Feeling frustrated | 21.77 | 30.13 |

| Feeling energetic | 37.04 | 31.90 |

| Feeling embarrassed | 7.44 | 16.54 |

| Feeling cheerful | 42.52 | 32.41 |

| Feeling bored | 33.41 | 34.77 |

| Feeling angry | 14.90 | 25.44 |

| Binge eating (1–100) | ||

| Binge eating 1d | 6.87 | 16.09 |

| Binge eating 2e | 7.64 | 17.20 |

Age determined by subject’s birthday and study date, rounded to that which participant would have reported

Defined as having a body mass index (BMI) that is in or over the 95th percentile

Ratio of ‘balanced’ to ‘unbalanced’ family characteristics

Eating to the point of being ‘embarrassed if seen’

Eating to the point of feeling a ‘loss of control’

EMA data

The EMA data used in the current study were on momentary moods and on momentary BE behaviors. EMA data were collected using PDAs, which participants had been trained to use during non-school hours. EMA data from the primary was collected on food/drink consumption, top-of-mind thoughts, location of food/drink consumption, social setting of food(s)/drink(s) consumption, activities surrounding food(s)/drink(s) consumption, levels of appetite/craving surrounding food(s)/drink(s) consumption, behaviors of self and of family members at the time of food(s)/drink(s) consumption, levels of stress, availability of food in the home, moods, and BE behaviors.

Momentary moods

Thirteen moods from a scale of daily affect were measured (Weinstein & Mermelstein, 2007; Weinstein, Mermelstein, Hankin, Hedeker, & Flay, 2007). These moods were: ‘feeling tired,’ ‘feeling stressed,’ ‘feeling sad,’ ‘feeling relaxed,’ ‘feeling lonely,’ ‘feeling left-out,’ ‘feeling happy,’ ‘feeling frustrated,’ ‘feeling energetic,’ ‘feeling embarrassed,’ ‘feeling cheerful,’ ‘feeling bored,’ and ‘feeling angry.’ Moods were scored on a continuous scale ranging from ‘0’ (“not at all”) to ‘100’ (“very much”).

Momentary binge eating

Binge eating was measured on a continuous scale from 1 to 100 (with higher numbers representing higher levels of BE), using two items from a Binge-Eating Disorder subscale of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS), a measure which has indicated adequate construct validity and excellent reliability (Burton, Abbott, Modini, & Touyz, 2016). These items were included along with each Eating Report and each Random Report. The first item, ‘Binge Eating 1,’ (BE1), asked, “Did you eat so much food in a short time that you would be embarrassed if someone saw you?” The second item, ‘Binge Eating 2,’ (BE2), asked, “Did you feel you couldn’t stop eating or control whatever how much you were eating?” (Grenard et al., 2013; Sierra-Baigrie, Lemos-Giráldez, & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2009; Stice et al., 2000).’ These items measured major symptoms of binge eating, as defined by the American Psychological Association (APA, 2013).

Analysis

This analysis focused on the main effects of moods on BE1 and BE2, as well as on a hypothesized moderation (i.e. protective or ‘buffering’ effect) of family functioning, on relationships between moods on BE1 and BE2. Study effects were examined with a series of multivariate, multilevel models implemented in the SAS Proc Mixed procedure (version 9.4). Multi-level models were set up using momentary responses (i.e. emotions, BE1, and BE2) as level-1, within-person variables; measures of family functioning were included in this analysis as level-2, between-person variables. Moderating effects were determined by cross-level interactions between momentary reports of emotions, BE1, and BE2 (level-1 variables) and baseline measures of family functioning (level-2 variables). Power calculations for the primary study (from which this data were taken) accounted for the multi-level structure of the data, assumed a minimum sample size of N = 150 and an α = 0.05, and were conducted using Raudenbush’s Optimal Design power calculations (Raudenbush & Liu, 2000). Power analyses detected a minimum of 0.80 statistical power for all analyses, for determining moderate to strong associations between daily ‘cues’ and dietary habits.

Results

For the current analysis, the data were limited to responses on which participants had provided information on momentary emotions; these responses consisted of EMA data of 3900 momentary measurements among 158 participants. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the variables used in this analysis. The outcome variables used in this analysis were two diagnostic criterion of binge eating, which these researchers referred to as “binge eating 1” (BE1) and “binge eating 2” (BE2). Participants provided responses on both of these variables (BE1 and BE2) in 2145 (55%) of a total of 3900 responses.

Table 2 presents results of main effects (beta slopes) of moods on levels of binge eating (i.e. mean differences in levels of BE, for one-unit increases in moods). At least one of two types of BE (i.e. BE1 or BE2) was significantly associated with the following moods: ‘tired,’ ‘stressed,’ ‘sad,’ ‘lonely,’ ‘left-out,’ ‘frustrated,’ ‘embarrassed,’ ‘bored,’ and ‘angry.’ There were no significant associations between BE and any of the following moods: ‘relaxed,’ ‘happy,’ ‘energetic,’ and ‘cheerful.’ In Tables 2 and 3, beta values represent changes in measures of BE for every 10 units of increase in moods (since moods were measured on a scale of 0–100), and p values reflect usage of one-tailed significance tests.

Table 2.

Relationship between adolescents’ moods and binge eating behaviors

| Feelings | Binge eating 1a |

Binge eating 2b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | Beta | SE | |

| Tired | 0.08 | 0.01 | **0.33 | 0.01 |

| Stressed | 0.21 | 0.01 | *0.30 | 0.02 |

| Sad | *0.29 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.02 |

| Relaxed | 0.15 | 0.01 | − 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Lonely | *0.51 | 0.03 | **0.68 | 0.03 |

| Left-out | **1.16 | 0.04 | **0.88 | 0.04 |

| Happy | − 0.09 | 0.01 | − 0.24 | 0.01 |

| Frustrated | **0.39 | 0.01 | *0.34 | 0.02 |

| Energetic | − 0.06 | 0.01 | − 0.19 | 0.01 |

| Embarrassed | **1.69 | 0.04 | **1.20 | 0.04 |

| Cheerful | − 0.04 | 0.01 | − 0.10 | 0.02 |

| Bored | *0.23 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.01 |

| Angry | *0.28 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

All associations measured with 1-tailed tests

Significant at p ≤ 0.05

Significant at p ≤ 0.01

Eating to the point of being ‘embarrassed if seen’

Eating to the point of feeling a ‘loss of control’

Table 3.

Family characteristicsa as moderators of the effects of momentary moodsb on momentary binge eatingc, among urban adolescents. Family characteristicsa as moderators of the relationship between momentary moodsb and momentary binge eatingc among urban adolescents

| Family cohesion |

Family flexibility |

Fam. communication |

Family satisfaction |

Family balanced |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | Beta | SE | Beta | SE | Beta | SE | Beta | SE | |

| Tired | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | *− 0.012 | 0.001 | − 0.009 | 0.001 | − 0.005 | 0.000 | − 0.005 | 0.000 | **− 0.717 | 0.027 |

| Binge eating 2 | *− 0.016 | 0.001 | − 0.009 | 0.001 | − 0.006 | 0.000 | *− 0.012 | 0.001 | *0.715 | 0.032 |

| Stressed | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | − 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | − 0.192 | 0.039 |

| Binge eating 2 | − 0.015 | 0.001 | − 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | − 0.008 | 0.001 | *− 0.914 | 0.047 |

| Sad | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | − 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | − 0.103 | 0.050 |

| Binge eating 2 | − 0.005 | 0.002 | − 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.001 | − 0.009 | 0.001 | − 0.949 | 0.066 |

| Relaxed | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | 0.002 | 0.001 | − 0.006 | 0.001 | − 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.038 | 0.034 |

| Binge eating 2 | 0.002 | 0.001 | − 0.013 | 0.001 | − 0.004 | 0.001 | − 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.096 | 0.037 |

| Lonely | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.001 | − 0.003 | 0.001 | − 0.381 | 0.080 |

| Binge eating 2 | − 0.015 | 0.002 | − 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | − 0.014 | 0.002 | − 1.202 | 0.094 |

| Left-out | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | *0.052 | 0.003 | 0.028 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.626 | 0.122 |

| Binge eating 2 | − 0.005 | 0.003 | − 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.002 | − 1.596 | 0.112 |

| Happy | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | *0.019 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.433 | 0.036 |

| Binge eating 2 | 0.001 | 0.001 | − 0.001 | 0.003 | − 0.001 | 0.001 | − 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.508 | 0.044 |

| Frustrated | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.025 | 0.041 |

| Binge eating 2 | − 0.002 | 0.001 | − 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | − 0.005 | 0.001 | − 0.596 | 0.045 |

| Energetic | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 | − 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.059 | 0.034 |

| Binge eating 2 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.085 | 0.041 |

| Embarrassed | ||||||||||

| Binge Eating 1 | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.033 | 0.003 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.039 | 0.002 | − 0.058 | 0.137 |

| Binge Eating 2 | *0.047 | 0.003 | 0.036 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.002 | 0.029 | 0.002 | 0.462 | 0.138 |

| Cheerful | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 | − 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.125 | 0.033 |

| Binge eating 2 | 0.000 | 0.001 | − 0.008 | 0.001 | − 0.001 | 0.001 | − 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.045 | 0.046 |

| Bored | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | *− 0.014 | 0.001 | − 0.011 | 0.001 | − 0.003 | 0.000 | − 0.002 | 0.001 | − 0.294 | 0.034 |

| Binge eating 2 | − 0.007 | 0.001 | − 0.005 | 0.001 | − 0.002 | 0.000 | − 0.002 | 0.001 | − 0.450 | 0.033 |

| Angry | ||||||||||

| Binge eating 1 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.001 | *0.010 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 | − 0.243 | 0.045 |

| Binge eating 2 | − 0.012 | 0.002 | − 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | − 0.001 | 0.001 | − 0.964 | 0.060 |

All associations measured with 1-tailed tests

Significant at p ≤ 0.05

Significant at p ≤ 0.01

Family characteristics: Family Balanced Cohesion, Family Balanced Flexibility, Family Communication, Family Satisfaction

Momentary moods: Tired, stressed, sad, relaxed, lonely, left-out, happy, frustrated, energetic, embarrassed, cheerful, bored, angry

Binge Eating 1: Eating to the point of being ‘embarrassed if seen’; Binge Eating 2: Eating to the point of feeling a ‘loss of controlߣ

Family balance: odds ratio of ‘balanced’ to ‘unbalanced’ family characteristics

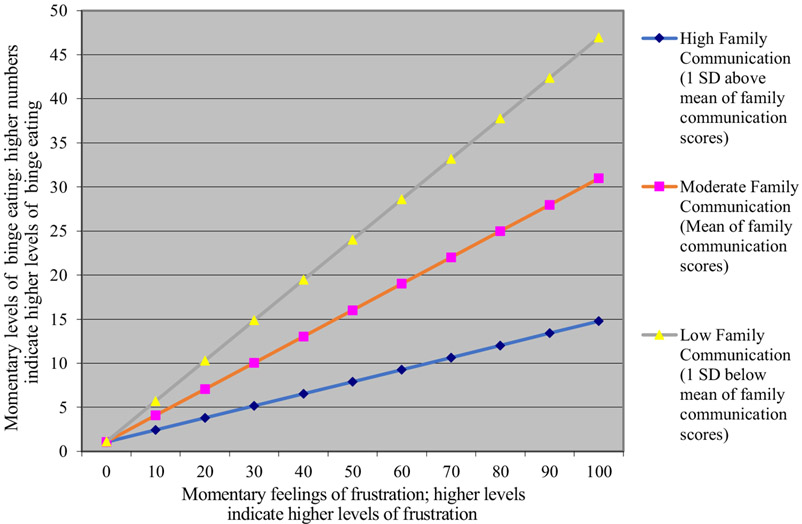

Table 3 presents results of the Level 2 (between-level) analysis: the interaction effects of family characteristics and momentary moods on BE (i.e. changes in the effects of momentary moods on BE, as affected by participants’ baseline family characteristics). For the sake of space, this manuscript only includes a graph of one interaction effect—the buffering effect of family communication on the relationship between ‘feeling frustrated’ and BE1 (p = 0.01), displayed in Fig. 1. This figure serves as an example of each of the buffering effects in this study, since the pattern of the interaction depicted in it is the same as that in each of the buffering effect in the study: at higher levels of family functioning, positive associations between feeling ‘tired,’ ‘stressed,’ ‘sad,’ ‘relaxed,’ ‘lonely,’ ‘left-out,’ ‘frustrated,’ ‘embarrassed,’ ‘bored,’ and ‘angry’ and BE are weaker. A list of interaction effects are reported in Table 3. Significant interactions were of ‘family cohesion’ × ‘feeling tired’ on BE1, ‘family cohesion’ × ‘feeling tired’ on BE2, ‘family cohesion’ × ‘feeling left-out’ on BE1, ‘family cohesion’ × ‘feeling happy’ on BE1, ‘family cohesion’ × ‘feeling embarrassed’ on BE2, ‘family cohesion’ × ‘feeling bored’ on BE1, ‘family communication’ × ‘feeling angry’ on BE1, ‘family satisfaction’ × ‘feeling tired’ on BE2, ‘family balance’ × ‘feeling tired’ on BE1, ‘family balance’ × ‘feeling tired’ on BE2, and ‘family balance’ × ‘feeling stressed’ on BE2.

Fig. 1.

Moderating effect of “family communication” on the relationship between “feeling frustrated” and “eating until the point of embarrassment if seen.” (The trend in this graph is representative of the trend of all interaction effects in this study)

Discussion

This study used EMA data to examine moderating effects of family functioning on relationships between moods and BE among healthy adolescents. Prior research indicates that BE is associated with more negative daily moods (Munsch et al., 2012; Zeeck et al., 2011), as well as lower levels of family functioning, as assessed using the FACES III (Leon et al., 1994; Tetzlaff et al., 2016), the FACES IV (Laghi et al., 2016), the Family Environment Scale (Hodges et al., 1998), and the Family Assessment Device (FAD) (Berge et al., 2014). Based on prior literature, we expected to find that negative moods would be positively associated with BE. These authors expected to find results in the direction of the stress-buffering effects model (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Cohen, 1988)—namely, that family functioning would provide a protective effect against the effects of negative—or “non-positive”—moods on BE.

Using a multi-level model which included both momentary emotions and family functioning characteristics, we found in some analyses that higher levels of ‘non-positive’ affect were associated with higher levels of binge eating, and that higher levels of family functioning provided significant buffers against the harmful effects of non-positive affect on BE.

Of the moods which indicated main effects on BE, ‘feeling lonely,’ ‘feeling left-out,’ ‘feeling frustrated,’ and ‘feeling embarrassed’ indicated the most consistent effects, in that these moods had main effects on not just one, but rather both, measures of BE. Of the measures of family functioning which indicated moderating effects of relationships between moods and BE, the two measures of family functioning which indicated the most consistent moderating effects were ‘family cohesion’ and for ‘family balance.’ While ‘family cohesion’ buffered the effects of ‘feeling tired,’ on BE1 and BE2 and of ‘feeling bored,’ on BE1,’ ‘family balance’ buffered the effects of ‘feeling tired,’ on BE1, and of ‘feeling stressed’ on BE2.

One explanation of how family functioning might buffer the effects of non-positive affect moods on BE is that family cohesion, family communication, family satisfaction, and family balance (e.g. “involvement in family members’ lives,” “closeness to family members,” “support of family members during difficult times,” “willing-ness to compromise with family members,” “ability to resolve family conflicts,” etc.) provide individuals with practical solutions for addressing the effects of non-positive moods. Such family characteristics may help people change their perceptions of certain problems or better cope with these problems, rather than engaging in BE behaviors, which might otherwise have been sought as a temporary relief or distraction from these problems.

The results of this study indicate the importance of “non-positive” affect (particularly feelings of loneliness, isolation, frustration, and embarrassment) and family functioning (particularly family cohesiveness and family balance), as predicting and moderating factors, respectively, of BE. As such, these results suggest theoretical support for affect-driven and interpersonal models of BE. Since this study was conducted among a non-clinical sample of students, the implications of its results for treatment may be limited to non-clinical binge eaters, and may suggest the utility of family-based interventions as strategies for reducing BE (i.e. by increasing the buffering effect of positive family functioning on the relationships between non-positive affect and BE).

The following are strengths within the current study. First, the data were collected used EMA—an intensive longitudinal data collection technique that involves collection of participants’ self-reports of their natural environments, at a time that is temporally close to that of the occurrences of outcome behaviors of interest. This technique improves the validity of data by reducing both interviewer and response bias. Second, study inclusion criteria did not include obesity, BED, or the incidence of any other eating disorders. As such, the results of this study may be generalized to non-clinical adolescent populations. Third, this study measured BE using two independent dimensional components: ‘loss of control,’ and ‘eating to the point of embarrassment.’ Since subjective understandings of ‘BE’ (Vannucci et al., 2013) can compromise the validity of data on its incidence, measuring this behavior with more than one item provides a level of increased validity.

Following are some limitations to the current study. First, the information used in this study was collected via self-report. Since participants may have had different interpretations of the meanings of ‘loss of control,’ and ‘eating with a sense of embarrassment,’ it would have informative to have independent measures of family functioning, moods, and BE. The reason this was not done was that these variables were not the focus of the primary study from which this data was taken. Second, the study measured associations in an observational design, which limits the strength of inferences that can be made. Third, given that the current analysis involved usage of multiple comparisons, there was an inflated risk of Type I error. These researchers considered addressing this risk with the application of a Bonferroni adjustment of p ≤ 0.01 to study results. After making the alpha level more stringent, all moderating effects of family functioning and negative moods on BE became statistically non-significant. This may have occurred because the Bonferroni test is relatively conservative, thus inflating the probability of Type 2 errors. Given that the current study was designed to provide only preliminary direction, non-adjusted results were retained and reported.

Implications for theory and treatment

Numerous studies have examined mechanisms that drive BE. Given the diversity of theories and models of this behavior (Ansell, Grilo, & White, 2012; Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Kenardy, Arnow, & Agras, 1996; Schulz & Laessle, 2010; Stein et al., 2007; Wilfley et al., 1997), a multiplicity of treatment options exist; these include Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy, and Cognitive Therapy (Berg et al., 2015). Since research on the efficacy of treatments has shown mixed results (Hay, 2013), there is a need for further research on which mechanisms underlie BE. The findings from this study may indicate a translational potential for preclinical and clinical populations, suggesting support for the usage of affect-based and/or interpersonal-based treatments for BED (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Kenardy et al., 1996; Schulz & Laessle, 2010; Stein et al., 2007).

Future directions

While the current study indicates that better levels of family functioning decrease the effect of moods on BE, future studies are needed to better understand the nature of this effect. Future researchers might investigate whether family characteristics—particularly cohesion and balance, are associated with (a) the quality and quantity of practical solutions to resolve unpleasant moods, (b) coping skills for addressing problems that lead to unpleasant moods, and (c) increased perceived efficacy to cope with these problems.

Future studies might also develop upon the current study by including additional measures of moods, specifically to capture current and anticipated moods. Research indicates that it is not just current emotions/moods which affect decision-making, but also anticipated emotions/moods, and that these two types of affect (i.e. current versus anticipated emotions/moods) can have different effects on decision-making (Mellers, 2000). As such, it may be informative for future researchers to explore the current questions, using measures of anticipated emotions or affect. It is possible that distinctions between these types of affect would affect the nature or magnitude of the interaction effects of family functioning on relationships between emotions and BE.

According to the appraisal-tendency framework (Lerner & Keltner, 2000, 2001) negative emotions (i.e. fear and anger) can exert opposing influences on choices and judgements. Regarding the construct of BE—this construct is also person- and context-dependent. For example, people who ‘objectively’ versus ‘subjectively’ BE have been shown to differ, with regard to eating concerns and overall caloric consumption (Vannucci et al., 2013). Furthermore, people who BE due to a ‘drive for thinness’ have been shown to differ, with regard to eating and comorbid psychopathology, from people who BE due to feelings of depression (Peñas-Lledó et al., 2009). Research indicates that, ‘eating to the point of embarrassment,’ may be affected by individual levels of ‘embarassability’—a personality ‘proneness’ that has been shown to be associated with ‘negative affect,’ (Edelmann & McCusker, 1986; Leary & Meadows, 1991; Miller, 1995). Finally, regarding family functioning, research indicates that differential definitions of family health (i.e. family functioning), such as interdependence (Crystal, Kakinuma, DeBell, Azuma, & Miyashita, 2008), authoritarianism (Supple & Cavanaugh, 2013) and other differentiation (Crystal et al., 2008) measures such as ‘emotional reactivity’ (Chung & Gale, 2009), are highly culture-dependent.

Future research may also add to the current model by including variables previously associated with disturbed eating attitudes, such as affiliative styles (Lewinsohn et al., 2002), neuroticism (Zander & Young, 2014), coping styles, and self-esteem (Fryer, Waller, & Kroese, 1997), as potential mediators or moderators of variables in this study. The EMA data that were used in this study could have been further explored with advanced statistical techniques. For example, building on prior research (Ansell et al., 2012; Ivanova et al., 2015), path analysis might be used for testing varied iterations of mediation/moderation, among relationships between moods, family functioning, and BE. Finally, further research using EMA data on BE might enable the development of EMA-based interventions for this problem, as has been developed for the treatment of bulimia nervosa (Norton, Wonderlich, Myers, Mitchell, & Crosby, 2003).

Conclusion

This study carries implications both for researchers and clinicians. For researchers, these results indicate the importance of considering moderating effects of family functioning, in studies that explore the relationship between moods and BE. For clinicians, these results suggest the usage of family-based therapies—particularly ones based on affect- and interpersonal-based models—for the treatment of pre-clinical BE among adolescents (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Kenardy et al., 1996; Schulz & Laessle, 2010; Stein et al., 2007).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Anna Yu Lee, Kim D. Reynolds, Alan Stacy, Zhongzheng Niu, and Bin Xie declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and Informed consent All procedures performed in study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board at Claremont Graduate University on September 4th, 2009. The protocol number was 1292, and the title of the study in the IRB application was, “Habitual and Neurocognitive Processes in Adolescent Obesity Prevention.” Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Binge-eating disorder. In: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Artlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell EB, Grilo CM, & White MA (2012). Examining the interpersonal model of binge eating and loss of control over eating in women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45, 43–50. 10.1002/eat.20897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Crosby RD, Cao L, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, et al. (2015). Negative affect prior to and following overeating-only, loss of control eating-only, and binge eating episodes in obese adults. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48, 641–653. 10.1002/eat.22401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge JM, Wall M, Larson N, Eisenberg ME, Loth KA, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2014). The unique and additive associations of family functioning and parenting practices with disordered eating behaviors in diverse adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 205–217. 10.1007/s10865-012-9478-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton A, Abbott M, Modini M, & Touyz S (2016). Psychometric evaluation of self-report measures of binge-eating symptoms and related psychopathology: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49, 123–140. 10.1002/eat.22453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, & Gale J (2009). Family functioning and self-differentiation: A cross-cultural examination. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, 31, 19–33. 10.1007/s10591-008-9080-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. (1988). Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 7, 269–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AB, & Koenig HG (2003). Religion, religiosity and spirituality in the biopsychosocial model of health and ageing. Ageing International, 28, 215–241. 10.1007/s12126-002-1005-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal DS, Kakinuma M, DeBell M, Azuma H, & Miyashita T (2008). Who helps you? Self and other sources of support among youth in japan and the USA. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 32, 496–508. 10.1177/0165025408095554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Seim HC, & Specker SM (1994). Eating related and general psychopathology in obese females with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 15, 43. 10.1002/1098-108X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eating Disorders. (2017, September 22). Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/topics/eating/

- Edelmann R, & McCusker G (1986). Introversion, neuroticism, empathy, and embarrassability. Personality & Individual Differences, 7(2), 133–140. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/223248491_Introversion_neuroticism_empathy_and_embarrassibility [Google Scholar]

- Elliott CA, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Columbo KM, Wolkoff LE, Ranzenhofer LM, et al. (2010). An examination of the interpersonal model of loss of control eating in children and adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 424–428. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer S, Waller G, & Kroese BS (1997). Stress, coping, and disturbed eating attitudes in teenage girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 22, 427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenard JL, Stacy AW, Shiffman S, Baraldi AN, MacKinnon DP, Lockhart G, et al. (2013). Sweetened drink and snacking cues in adolescents: A study using ecological momentary assessment. Appetite, 67, 61–73. 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay P. (2013). A systematic review of evidence for psychological treatments in eating disorders: 2005–2012. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 10.1002/eat.22103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, & Baumeister RF (1991). Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 86–108. 10.1037/0033/2909.110.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EL, Cochrane CE, & Brewerton TD (1998). Family characteristics of binge-eating disorder patients. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 23, 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, & Kessler RC (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 348–358. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova IV, Tasca GA, Hammond N, Balfour L, Ritchie K, Koszycki D, et al. (2015). Negative affect mediates the relationship between interpersonal problems and binge-eating disorder symptoms and psychopathology in a clinical sample: A test of the interpersonal model. European Eating Disorders Review, 23, 133–138. 10.1002/erv.2344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenardy J, Arnow B, & Agras WS (1996). The aversiveness of specific emotional states associated with binge-eating in obese subjects. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 30, 839–844. 10.3109/00048679609065053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, & Essex M (1982). Marital status and depression: The role of coping resources. Social Forces, 61, 484–507. [Google Scholar]

- Laghi F, McPhie ML, Baumgartner E, Rawana JS, Pompili S, & Baiocco R (2016). Family functioning and dysfunctional eating among italian adolescents: The moderating role of gender. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47, 43–52. 10.1007/s10578-015-0543-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, & Meadows S (1991). Predictors, elicitors, and concomitants of social blushing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 10.1037/0022-3514.60.2.254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leon GR, Fulkerson JA, Perry CL, & Dube A (1994). Family influences, school behaviors, and risk for the later development of an eating disorder. Journal of Youth and Adolescence: A Multidisciplinary Research Publication, 23, 499–515. 10.1007/BF01537733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner J, & Keltner D (2000). Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cognition and Emotion, 14, 473–493. 10.1080/026999300402763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JS, & Keltner D (2001). Fear, anger, and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 146–159. 10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Striegel-Moore RH, & Seeley JR (2002). The epidemiology and natural course of eating disorders in young women from adolescence to young adulthood. Selected Works. 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellers BA (2000). Choice and the relative pleasure of consequences. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 910–924. 10.1037//0033-2909.126.6.910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RS (1995). On the nature of embarrassability: Shyness, social evaluation, and social skill. Journal of Personality, 63, 315–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch S, Meyer AH, Quartier V, & Wilhelm FH (2012). Binge eating in binge eating disorder: A breakdown of emotion regulatory process? Psychiatry Research, 195, 118–124. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton M, Wonderlich SA, Myers T, Mitchell JE, & Crosby RD (2003). The use of palmtop computers in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 11, 231–242. 10.1002/erv.518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH, Gorall DM, & Tiesel JW (2009). FACES IV manual. Minneapolis, MN: Life Innovations. [Google Scholar]

- Peñas-Lledó E, Fernández-Aranda F, Jiménez-Murcia S, Granero R, Penelo E, Soto A, et al. (2009). Subtyping eating disordered patients along drive for thinness and depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 513–519. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, & Liu X (2000). Statistical power and optimal design for multisite randomized trials. Psychological Methods, 5, 199–213. 10.1037//1082-989X.5.2.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN (1980). Social support resources, stress and maladjustment of poor children. American Journal of Community Psychology, 8, 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz S, & Laessle RG (2010). Associations of negative affect and eating behaviour in obese women with and without binge eating disorder. Eating and Weight Disorders Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 15, 287–293. 10.1007/BF03325311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Baigrie S, Lemos-Giráldez S, & Fonseca-Pedrero E (2009). Binge eating in adolescents: Its relation to behavioural problems and family-meal patterns. Eating Behaviors, 10, 22–28. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RI, Kenardy J, Wiseman CV, Dounchis JZ, Arnow BA, & Wilfley DE (2007). What’s driving the binge in binge eating disorder?: A prospective examination of precursors and consequences. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 195–203. 10.1002/eat.20352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Telch CF, & Rizvi SL (2000). Development and validation of the eating disorder diagnostic scale: A brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychological Assessment, 12, 123–131. 10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ (1959). Eating patterns and obesity. Psychiatric Quarterly, 33, 284–295. 10.1007/BF01575455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, & Cavanaugh AM (2013). Tiger mothering and Hmong American parent–adolescent relationships. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4, 41–49. 10.1037/a0031202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff A, Schmidt R, Brauhardt A, & Hilbert A (2016). Family functioning in adolescents with binge-eating disorder. European Eating Disorders Review, 24, 430–433. 10.1002/erv.2462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci A, Theim KR, Kass AE, Trockel M, Genkin B, Rizk M, et al. (2013). What constitutes clinically significant binge eating?: Association between binge features and clinical validators in college-age women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46, 226–232. 10.1002/eat.22115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SM, & Mermelstein R (2007). Relations between daily activities and adolescent mood: The role of autonomy. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36, 182–194. 10.1090/15374410701274967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SM, Mermelstein RJ, Hankin BL, Hedeker D, & Flay BR (2007). Longitudinal patterns of daily affect and global mood during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 587–600. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00536.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Pike KM, & Striegel-Moore RH (1997). Toward an integrated model of risk for binge eating disorder. Journal of Gender Culture and Health, 2, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zander ME, & Young KP (2014). Individual differences in negative affect and weekly variability in binge eating frequency. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47, 296–301. 10.1002/eat.22222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeck A, Stelzer N, Linster HW, Joos A, & Hartmann A (2011). Emotion and eating in binge eating disorder and obesity. European Eating Disorders Review, 19, 426–437. 10.1002/erv.1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]