Abstract

Calcium ions (Ca2+) enter mitochondria via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter, driven by electrical and concentration gradients. In this regard, transgenic mouse models, such as calsequestrin knockout (CSQ-KO) mice, with higher mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]mito), should display higher cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]cyto). However, repeated measurements of [Ca2+]cyto in quiescent CSQ-KO fibers never showed a difference between WT and CSQ-KO. Starting from the consideration that fluorescent Ca2+ probes (Fura-2 and Indo-1) measure averaged global cytosolic concentrations, in this report we explored the role of local Ca2+ concentrations (i.e., Ca2+ microdomains) in regulating mitochondrial Ca2+ in resting cells, using a multicompartmental diffusional Ca2+ model. Progressively including the inward and outward fluxes of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), extracellular space, and mitochondria, we explored their contribution to the local Ca2+ distribution within the cell.

The model predicts Ca2+ concentration gradients with hot spots or microdomains even at rest, minor but similar to those of evoked Ca2+ release. Due to their specific localization close to Ca2+ release units (CRU), mitochondria could take up Ca2+ directly from high-concentration microdomains, thus sensibly raising [Ca2+]mito, despite minor, possibly undetectable, modifications of the average [Ca2+]cyto.

Why it matters

In skeletal muscle, Ca2+ enters the inner mitochondrial membrane via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) to regulate metabolic activation and apoptosis. Due to the proximity of the MCU to the ryanodine receptor type-1 (RyR1), which releases Ca2+ in the myoplasm during stimulation, mitochondria take advantage of a locally high [Ca2+] named microdomains. Here, we show, by means of a numerical model, that these microdomains are present also in resting fibers, induced by RyR1 leakage. These “resting microdomains” become even more relevant in the calsequestrin knockout (CSQ-KO) mouse model where the RyR1 leakage is enhanced. These resting microdomains can explain the observed mitochondrial [Ca2+] at rest in CSQ-KO fibers, with a minimum, possibly undetectable, variation in the average cytosolic [Ca2+].

Introduction

In skeletal muscle fibers, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is both the largest intracellular Ca2+ store and the only compartment able to quickly release and reuptake Ca2+. In this way, SR links the sarcolemma electrical activity to myofibrillar force generation. The relevance of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake to regulate ATP synthesis is widely accepted, but their ability to store Ca2+ has been debated for many years. Recently, the determination of mitochondrial Ca2+ content, using the membrane lysis method (1), has definitely confirmed that, in skeletal muscle, mitochondria are endowed with a high Ca2+-buffering capacity.

Interestingly, the lysis method showed that total mitochondrial calcium content is increased in two transgenic mouse models with a Ca2+ leak through SR ryanodine receptor type-1 (RyR1) Ca2+ channel: a gain of function RyR1 knockin and the calsequestrin knockout (CSQ-KO) mice (1). In RYR1 models, a direct comparison between total mitochondrial calcium and free mitochondrial Ca2+ ([Ca2+]mito) showed the high buffering power of the organelle, while a comparison with previously published data on free cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyto) suggested a high sensitivity of [Ca2+]mito to small changes in [Ca2+]cyto (2). Similar conclusions were suggested also for CSQ-KO mice; however, for this mouse model, these relationships were only extrapolated without using data on [Ca2+]mito and [Ca2+]cyto present in the literature (3,4,5,6). While the higher total mitochondrial calcium is consistent with previous data that report an increased [Ca2+]mito in CSQ-KO mice, [Ca2+]cyto was never found to be higher compared with WT mice.

By combining previously published data (1,1,6), here we aim at exploring further the role of [Ca2+]cyto on mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation in resting skeletal muscle fibers and, by means of theoretical and numerical methods, the specific dependence on the local Ca2+ concentration. Our results suggest that a small, possibly undetectable, difference in the averaged [Ca2+]cyto can be associated with the increment in total and free mitochondrial calcium levels thanks to the existence of the “microdomains,” where the [Ca2+]cyto is locally higher than the average value due to their peculiar position. Their existence is well established during contraction (7) but their role in resting muscle is much less considered.

The buffering power of mitochondria in WT and CSQ-KO fibers

The free [Ca2+]mito was determined in FDB fibers of CSQ-KO male mice using the cameleon-4mtD3cpv sensor by Scorzeto et al. (6) (see Fig. 1). Males were chosen because they showed a more severe phenotype than females, in particular the hyperthermic crises were more frequent (8,9). In quiescent fibers, the free [Ca2+]mito was higher in CSQ-KO (0.23 μmol/Lmito) than in WT (0.16 μmol/Lmito). Combining the [Ca2+]mito determined by Scorzeto et al. (6) with the total mitochondrial calcium content determined with the lysis method by Lamboley et al. (1), the buffering power in quiescent CSQ-KO fibers can be quantified as follows.

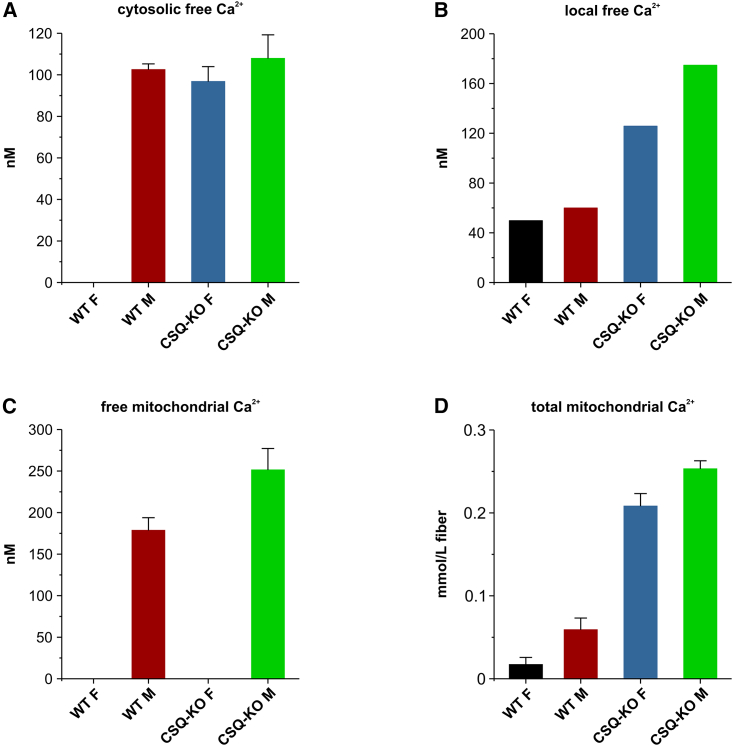

Figure 1.

(A) Resting cytosolic free Ca2+ (means ± SEM) concentration determined with Fura-2 (5,6), (B) resting local peri-mitochondrial free Ca2+ concentration estimated by Seng et al. (2), (C) resting free Ca2+ concentration (means ± SEM) in the mitochondrial matrix measured with cameleon 4mtD3cpv (6) and relevant calibration curve, (D) resting total mitochondrial calcium concentration (means ± SD) measured with the lysis method by Lamboley et al. (1). No experimental measurements are available for cytosolic concentration in WT females and for mitochondrial concentration in WT and CSQ-KO females (see text).

Extrapolated from Fig. 5 in (1), the values of total mitochondrial calcium per fiber liter are 0.06 and 0.25 mmol/Lfiber for WT and CSQ-KO, respectively. Assuming a mitochondrial volume of 5% of total fiber volume in WT and 8% (i.e., 60% higher (6,10)) in CSQ-KO, the total calcium concentrations per mitochondria liter become 0.06/0.05 = 1.2 mmol/Lmito and 0.25/0.08 = 3.12 mmol/Lmito for WT and for CSQ-KO, respectively. The buffering power can therefore be estimated to be 1200/0.16 μmol/Lmito = 7500 and 3120/0.23 μmol/Lmito = 13565 for WT and CSQ-KO, respectively. It is worth underlining that the values reported by Scorzeto et al. (6) refer to deletion of both CSQ1 and CSQ2 (double knockout), while the data of Lamboley et al. (1) refer to CSQ1 ablation. Actually, the difference is small as CSQ2 is a minor isoform in fast fibers and, as shown by Tomasi et al. (11), the ablation of CSQ1 alone leads to a reorganization of the terminal cisternae with a severe (up to 80%) reduction of other triadic proteins, among them CSQ2, triadin, and sarcalumenin.

The values of buffering power calculated above are fully comparable with those determined: 1) by Lamboley et al. (1) for skeletal muscle fibers of WT and RYR1 mutation, 2) by Madsen (12) in mitochondria isolated from human skeletal muscle biopsy, and 3) in liver, brain, and heart (13,14). The higher buffering power in CSQ-KO may be explained through an adaptive response to the genetic ablation of the CSQ. However, it may also be a consequence of a strong cooperativity in the mitochondrial buffers, as is the case for CSQ itself (15,16). A variable buffering power in cardiac mitochondria assuming the presence of multiple molecular species acting as a calcium buffer has been proposed in (14).

A high cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is needed to increase mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake

Ca2+ enters the inner mitochondrial membrane via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU), driven by an electrochemical gradient. Thus, to a first approximation, a higher free [Ca2+]mito should imply a higher [Ca2+]cyto. Accordingly, the interpretation proposed by Lamboley et al. (1) was that the higher total mitochondrial calcium content in CSQ-KO than WT muscles requires a quite higher [Ca2+]cyto in the former case. However, their approach to describe the relationship between total mitochondrial calcium and average free cytosolic Ca2+, despite informative, had some limits, which possibly overestimated the needed increase in [Ca2+]cyto. The relationship, substantially based on male CSQ1-KO and heterozygous and homozygous RYR1 knockin mice data, was shifted to a resting [Ca2+]cyto in WT of only 50 nM, a choice which emphasized the differences between phenotypes. Moreover, as also acknowledged by Lamboley et al. (1) , the local Ca2+ concentration at the mitochondrial microdomain likely plays a crucial role in defining the resting [Ca2+]mito, but this was not considered in that study. As a result, they concluded that a [Ca2+]cyto more than three times higher in CSQ-KO than in WT fibers, was necessary to explain the greater calcium accumulation in the mitochondria. This conclusion is in sharp contrast with the direct measurements, as such a difference was never detected either with Indo-1 (17,18) or with Fura-2 (3,4,5,6), a high-affinity probe with a Kd = 145 nM (data sheet Thermo Fisher), thus perfectly suitable to detect variations of the resting [Ca2+]cyto (see Fig. 1 A).

Importantly, a leaky RyR1 is not sufficient to alter resting [Ca2+]cyto by itself. According to the “cell boundary theorem” (19), steady-state [Ca2+]cyto in quiescent fibers is determined solely by exchanges with the extracellular space through the sarcolemma, while changes of Ca2+ fluxes within intracellular compartments cannot modify it permanently. In other words, [Ca2+]cyto depends on the balance between Ca2+ influx and efflux at the plasma membrane, which can be translated in mathematical terms as follows (19):

| (1) |

where influx and efflux represent the Ca2+ exchanged with the external space, and removal and release the exchanges with a particular organelle org. At the truly steady-state, when , the last two terms must be equal, and therefore also the first two terms equate each other, so:

| (2) |

which, considering the constancy of [Ca2+]ext and assuming a one-to-one matching between [Ca2+]cyto and the fluxes, leads to the conclusion that only a modification of the exchanges with the external space can regulate [Ca2+]cyto.

Thus, a higher [Ca2+]cyto would require either a decreased efflux, via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger or the plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA), or an enhanced influx via store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE). Lamboley et al. (1) have shown an altered Ca2+ permeability of the transverse tubular system membrane. A constitutively active SOCE through the recently described intracellular SR/transverse-tubule junctions at the I band of the sarcomere named Ca2+ entry units, was reported in both fast- and slow-twitch fibers from CSQ-KO mice, likely as a compensative mechanism for the massive reduction of total SR calcium content observed in these animals (20,21). These modifications can then be responsible for an altered [Ca2+]cyto, but for a quantitative understanding of their role we must consider also the influence of the steady-state Ca2+ gradients generated by RyR1 leaks, as shown in the next section.

In fibers with leaky SR, mitochondria might take up Ca2+ from microdomains

In understanding the discrepancy between higher mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration and unchanged free [Ca2+]cyto we noted that measurements of [Ca2+]cyto at rest, carried out with Fura-2 or other probes, only yielded an average or pooled [Ca2+]cyto. As we discussed in a recent review (22), at the mitochondria-CRU microdomain distance (∼140 nm) (23) a free Ca2+ concentration higher than the pooled or averaged cytosolic concentration can be expected, not only during Ca2+ release events but also in the presence of Ca2+ leakage.

In the “global version” of the cell boundary theorem reported above, in Eqs. 1 and 2, without a structural modification of the channels/pumps that support efflux and influx, the two fluxes keep a constant dependence of [Ca2+]cyto on [Ca2+]ext, and therefore any perturbation is fated to reach the sole value that equilibrates the two fluxes. However, as already noted by Ríos (19), in the presence of gradients within the cell, Eq. 1 is true only after “integration over the entire plasmalemma.” Alternatively, considering that the exchanges occur in a finite number of structures, we can write:

| (3) |

This “local version” of the cell boundary theorem considers the local [Ca2+]cyto in front of each influx (ic) or efflux (ec) channel/pump. The local version of the theorem is equivalent to the global version if we include a function “g,” which, accounting for the geometrical and diffusional constraint in the cell, links the two concentrations through [Ca2+]ic/eccyto = g([Ca2+]cyto). In this way, the new equation is again a function of the sole variable [Ca2+]cyto in the steady state. However, if the gradient generated by a different value of the removal and release fluxes is big enough to sensibly affect the function g, then the modification has an implicit effect also on the shape of the influx (g([Ca2+]cyto)) and efflux (g([Ca2+]cyto)), pointing to a different value for the [Ca2+]cyto at the equilibrium.

The previous reasoning implies that the effects of changes in the internal fluxes on the average [Ca2+]cyto can only be evaluated taking into account also the local [Ca2+] gradients. Therefore, we quantified the magnitude of the [Ca2+] gradient with a diffusion rate of Ca2+ equal to 3 × 10–6 cm2/s (24), generated by a leaky RyR1 in a quiescent sarcomere, of 2.5 μm length and 0.5 μm radius, improving our previous diffusional model (see supporting material) of a half-sarcomere of a WT fast skeletal muscle, which includes the major buffers and organelles, and refining the mesh with 50 longitudinal and 20 radial compartments (25). We progressively included into the model the inward and outward fluxes to explore their contribution to the local Ca2+ concentration. In each version of the model we kept fixed the uptake capacity of the SERCA pumps, described as a series of saturable first-order pumps distributed along the SR with maximum cumulative uptake rate of 5.6 mmol/s/Lfiber at 25°C (from 4 mmol/s/Lfiber at 20°C with Q10 = 2) and Kd = 0.5 μM (26). As a simplest case (Fig. 2, case 1) we hypothesized that the leakage of the RyR1, located on the SR at 500 nm from the Z-line, as it is the case for mammalian, and specifically mice, fast skeletal muscle (27), is fully balanced by the continuous uptake of the SERCA pumps. When the constant rate of the RyR1 leak is modulated to keep the average [Ca2+]cyto at the resting level of 100 nM, the resulting local [Ca2+] in the microdomain close to mitochondria is about 50% higher. The calculated RyR1 leakage resulted to be 255 μmol/s/Lfiber.

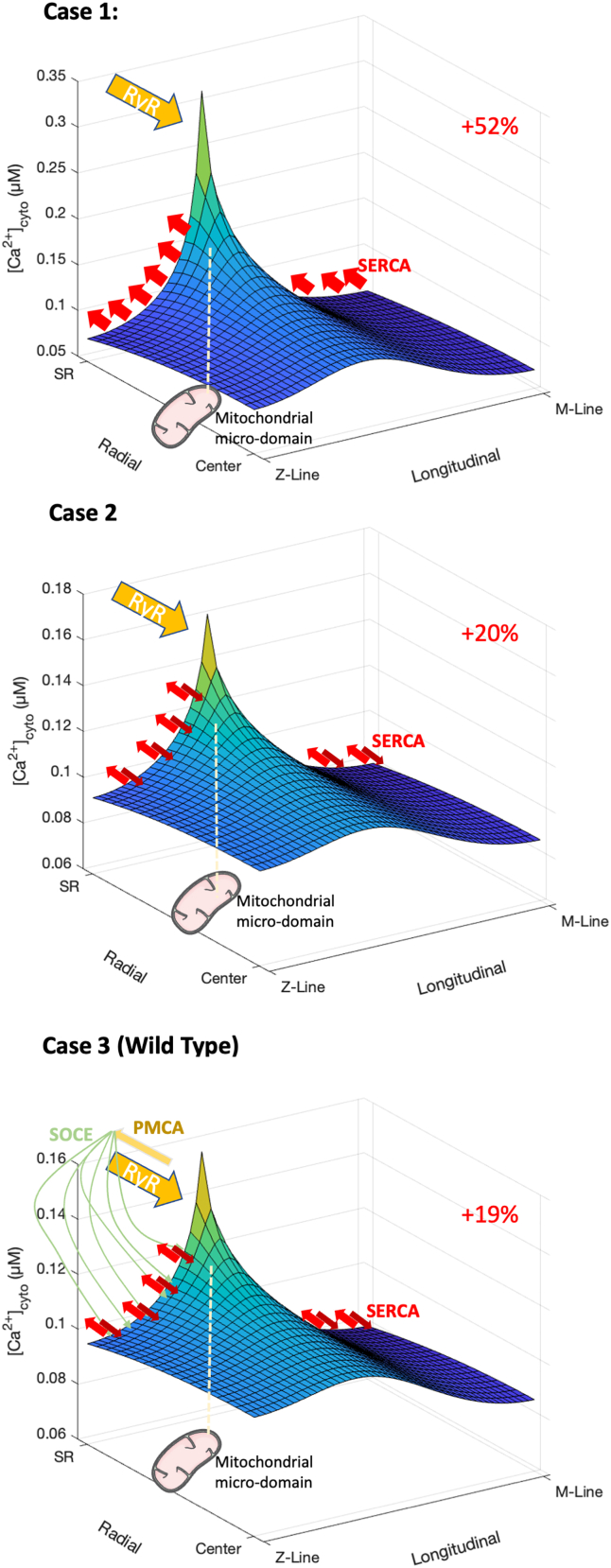

Figure 2.

Cytosolic [Ca2+] in a quiescent half-sarcomere of a fast-twitch WT mouse fiber with increasing complexity of the internal and external Ca2+ fluxes. Case 1: the leakage of the RyR1, located on the SR at 500 nm from the Z-line, is fully balanced by the continuous uptake by the SERCA pumps, described as a series of saturable first-order pumps distributed along the SR with maximum cumulative uptake rate of 4 mmol/s/Lfiber and Kd = 0.5 μM (26). The constant rate of the RyR1 leak is modulated to keep the average cytosolic [Ca2+] at the physiological level of 100 nM. The position of the RyR1 is indicated by the yellow arrow, the red arrows indicate the positions of the SERCA. The white dashed line indicates the likely location of the closest compartment of an intermyofibrillar mitochondrion at 140 nm from the CRU (23). Case 2 introduces a non-RyR1 leakage in the SR of 75% of the SERCA uptake rate. Case 3 includes also Ca2+ fluxes with the extracellular space and can represent the WT situation. Percentages in red indicate the increase in the local mitochondrial microdomain concentration with respect to the bulk level.

For a Figure360 author presentation of this figure, see https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpr.2023.100117.

This was, however, the simplest case, which did not include Ca2+ influx and efflux across the sarcolemma. To reach a more realistic situation, we included first a non-RyR1 leakage in the SR, which can account for three-fourths of the total reuptake of SERCA in resting muscle, as estimated by Barclay and Launikonis starting from the rate of heat output from noncontracting human forearm muscles (26). In this case (Fig. 2, case 2), the constant RyR1 leak calculated to keep the [Ca2+]cyto resting level at 100 nM was lower and the local [Ca2+] in the mitochondrial microdomain was 20% higher than that level. Moreover, the gradient was even more reduced when we included in the model the Ca2+ exchange with the extracellular space. We hypothesized (Fig. 2, case 3) an extrusion of Ca2+ through the PMCA of the 10% of the total RyR1 leakage (26), located in the junctional space, i.e., same cytosolic compartment of the RyR1, balanced by a series of influxes disposed along the SR, to mimic the SOCE. The localization of these outward and inward fluxes reduces the gradient generated by the RyR1 leak, creating a sort of shortcut in the mathematical model, bringing an amount of Ca2+ from the triad directly to the uptake compartments. Although relatively small, it is sufficient to reduce the gradient in the local [Ca2+] of the mitochondrial microdomain, which is now 19% higher than the bulk level. We considered this last case as representative of the WT cells. The RyR1 leakage, which keeps the average [Ca2+]cyto to 100 nM in this more realistic case, is computed to be about 50 μM/s/Lfiber (Table 1). This value is compatible with the value of 17 μmol/s/Lfiber obtained in the model proposed in (1) considering that in that study a basal level of [Ca2+]cyto of only 50 nM has been imposed.

Table 1.

Comparison of the fluxes and Ca2+ concentrations in the WT and in the CSQ-KO with two different leaks in the RyR (see text)

| RyR1 (μM/s) | [Ca2+]cyto (nM) | [Ca2+]microdomain (nM) | [Ca2+]mito nM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 50 | 100 | 119 | 160 |

| RyR1 ×2.3 | 130 | 117 | 140 | 230 |

| RyR1 ×5 | 250 | 142 | 189 | 420 |

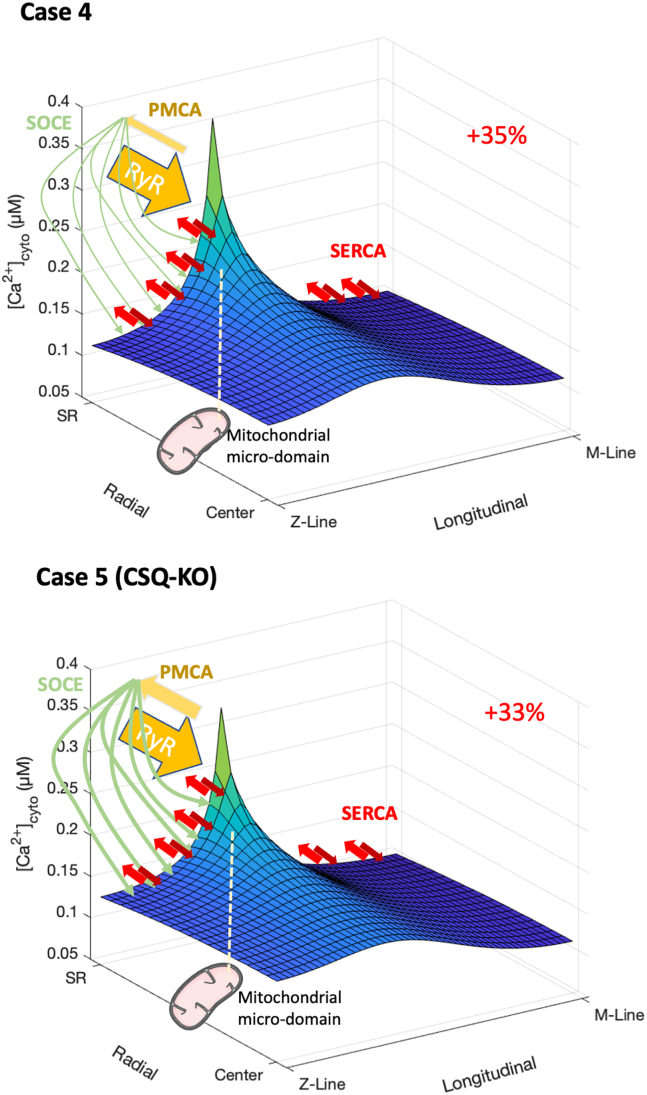

Next, we used the model to estimate the sole effect of an increased RyR1 leakage, as observed in CSQ-KO muscles, on both the average [Ca2+]cyto and on the local [Ca2+] of the mitochondrial microdomain. Although the CSQ ablation possibly affects to a different extent several model parameters, we adopted a ceteris paribus approach, where the estimated increase in RyR1 leakage is the sole parameter modified along with the absence of the CSQ buffer in the SR. We aimed at showing how much the increase in RyR1 leakage alone can influence the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. First, we explored the impact of a fivefold increase of the leakage. This means a constant leak of 250 μmol/s/Lfiber, close to what was estimated by a previous work for CSQ-KO cells (238.5 μmol/s/Lfiber) (1). Without further modifications of other fluxes, the increased RyR1 leak generates an average [Ca2+]cyto of 142 nM, with an increase of the [Ca2+] in the mitochondrial microdomains of +35% (192 nM, Fig. 3, case 4). When the RyR1 leakage is chronically raised, a simultaneous increase in Ca2+ extrusion, through PMCA, and reuptake, through SOCE, is observed (28). PMCA is very close to RyR1 and highly sensitive to local [Ca2+] in the junctional space (1), while SOCE, activated to keep constant the SR Ca2+ content, releases Ca2+ in a close proximity with the SERCA (29). When we included a faster Ca2+ exchange with the extracellular space, as previously observed in this mouse model (20), increasing the extracellular flux from 10 to 50% of the RyR1 leak in the WT case, the average [Ca2+]cyto value was almost unaffected, while the local [Ca2+] of the mitochondrial microdomain decreased to 189 nM (+33% with respect to the bulk value, Fig. 3, case 5). Interestingly, this local value is very close to the Ca2+ concentration extrapolated in (1) from the relationship between total mitochondrial calcium and average [Ca2+]cyto as described above.

Figure 3.

Cytosolic [Ca2+] in a quiescent half-sarcomere of a fast-twitch CSQ-KO mouse fiber with increasing complexity of the internal and external Ca2+ fluxes. Description as in Fig. 2, with an increased RyR1 leak of a factor of 5. Case 4: Ca2+ exchange with the extracellular space is kept as in the WT case 3. Case 5 accounts for a greater Ca2+ exchange with the extracellular space, representative of the CSQ-KO situation.

Our simulation predicts that the presence of higher local [Ca2+] might provide an acceptable explanation of the [Ca2+]mito higher in CSQ-KO than in WT even in the presence of a similar resting global [Ca2+]cyto. Interestingly, the privileged location of the mitochondria suggests that, in the presence of leakage from SR, they might contribute to stabilize or prevent increase in average [Ca2+]cyto and, at the same time, enhance the leakage via ROS and RNS generation. The cystein thiol groups of RYR1 and SERCA are well-known targets of ROS/RNS (for a review, see (30)). In addition, the increased free [Ca2+]mito would boost ATP production, which is beneficial to support the SERCA-mediated SR refilling. The recent demonstration that RyR1 Ca2+ leak determines a standing [Ca2+] gradient between RyR1 and SERCA (31) is consistent with this view.

The Ca2+ uptake via MCU is not the only determinant of mitochondrial calcium content

Next, we made an attempt to estimate the resting [Ca2+]mito generated by the different gradient in [Ca2+]cyto in WT and in CSQ-KO cases including into the model a mitochondrial compartment located at about 140 nm from the RyR1. In this context it is worth underlining that intramitochondrial free and total calcium concentrations are not simply determined by the influx via the MCU complex driven by the Ca2+ electrochemical gradient. The kinetic balance of Ca2+ accumulation by mitochondria can be described more correctly by the equation

| (4) |

where , kon, and Koff are the rate constants of the buffer, and Btot and BCa are the total and Ca2+-bound concentrations, respectively, of intramitochondrial buffers (see (22)).

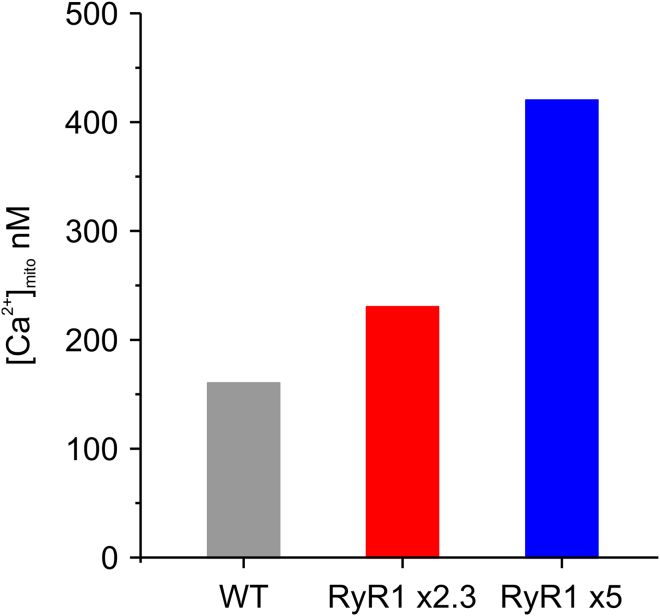

As underlined by Eq. 4, the mitochondrial ability to accumulate Ca2+ does not depend only on the MCU-mediated influx, but also on the buffer capacity and on outflow via the sodium-calcium-lithium exchanger (NCLX) or via permeability transition pore. It is plausible that the increased SR Ca2+ leakage determined by constitutive ablation of CSQ or gain-of-function RYR1 mutations could induce adaptive response of the mitochondria. An increased mitochondrial density has been observed in CSQ-KO fibers (10) and swollen mitochondria can be found in fibers with RYR1 mutations (32). As discussed above, the comparison between the total and free mitochondrial calcium determined by our group and others points to an increased buffer capacity in CSQ-KO fibers, eventually reducing the free Ca2+ during transient states. An increased influx, or a decreased efflux, can instead increase [Ca2+]mito in resting CSQ-KO fibers. However, lacking experimental data, and with the aim of analyzing the effect of RyR1 leakage in a ceteris paribus approach, in the following we kept the values of MCU and NCLX parameters equal in WT and CSQ-KO. Thus, in an attempt to reproduce the balance of these two fluxes in WT and CSQ-KO cells, we simulated MCU as a saturable first-order kinetics, with Vmax = 22.4 μmol/s/Lfiber (from (33) adapted at 25°C with a Q10 of 2) and cooperativity of 2 (25), while Ca2+ extruded through NCLX was simulated as proposed in (34) with a 3:1 stoichiometry for Na+ and Ca2+. Maximum extrusion velocity was imposed to match the measured resting [Ca2+]mito in WT of 160 nM (6). Cooperativity in the MCU Ca2+ uptake represents the changes in the calcium affinity of the MCU induced by [Ca2+]cyto via MICU1/2 subunits (35). Keeping these values constant, the model indicated that the predicted increase of local [Ca2+] in the mitochondrial microdomain with a fivefold increase of RyR1 leak would lead to a resting [Ca2+]mito of 420 nM, higher than that observed experimentally by Scorzeto et al. (6). A value closer to that seen experimentally (230 nM) was reached imposing a factor of 2.3 in the RyR1 leak in CSQ-KO compared with WT (Fig. 4). This value required a local [Ca2+] in the mitochondrial microdomain at 140 nM, and the average [Ca2+]cyto to 117 nM, only 17% higher than the WT counterpart, and possibly below the resolution obtained experimentally with Fura-2 measurements (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial free calcium concentration in WT and in CSQ-KO with two different RyR1 leakages, 2.3 and 5 times greater, respectively, than in WT.

Conclusion

The present results contribute to the quantitative understanding of how local gradients or hotspots/microdomains are generated, not only during contraction but also at rest, and how relevant they are to mitochondrial Ca2+ regulation.

Some limits must be acknowledged both for the numerical model and for the experimental data. Parameters for the maximum fluxes and cooperativities are still under debate in literature and their mathematical representation is necessarily a simplification of the real events. This is particularly true for the mitochondrial model, where the Na+ and H+ homeostasis is not considered as well as possible variation in the membrane potential.

Our ceteris paribus approach, which imposed for the CSQ-KO simulations the same parameters used for the WT case, except for the RyR1 leakage, allowed to highlight the crucial role of the RyR1 leakage in determining the mitochondrial calcium content at rest. We acknowledge that modifications in the mitochondrial Ca2+ buffer, influx, or efflux would also affect [Ca2+]mito but, to the best of our knowledge, these adaptive alterations due to genetic ablation of the CSQ are not quantitatively characterized experimentally. An extension of the model to include these effects is left for future work. Finally, the existence of a MCU “threshold,” as a minimum level of [Ca2+]cyto that triggers the MCU Ca2+ influx, has been hypothesized (36) but, since its existence is still under debate (37), we decided to include these effects in the model through the imposed MCU cooperativity.

As to experimental determination of cytosolic and free mitochondrial [Ca2+], it is important to underline the differences between male and female mice in both WT and CSQ-KO (see Fig. 1). Malignant hyperthermia crises occurred much less frequently in females when exposed to anesthetics or to high environmental temperature (8,9). The data suggested that a better redox control in females can explain the sex-related difference (3,4,5). Similarly to RYR1 mutations (32), in CSQ-KO fibers, the Ca2+ leakage increases ROS/RNS production, which in turn enhances RyR1 permeability via nitrosylation of cysteine residues (3). It is also worth noting that another important factor is the temperature. The free [Ca2+]cyto and free [Ca2+]mito measurements (5,6), as well as of the total mitochondrial calcium (1,2) in the CSQ-KO model, were obtained at room temperature (25°C). In muscle fibers with leaky RyR1, no difference in [Ca2+]cyto is present at low temperature (38). The difference appears only when temperature is increased toward physiological values (32,39). Finally, the determinations of [Ca2+]cyto were performed in fibers dissociated with collagenase (6), which are partially depolarized (resting potential close to –60 mV, (40)) and this possibly affects the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger both in CSQ-KO and WT.

Nonetheless, the model prediction demonstrates that the gradients between the CRU and the closest intermyofibrillar mitochondria due to the continuous leakage provides the link to the free and total mitochondrial calcium in resting skeletal muscle. Moreover, the presence of local variations of [Ca2+]cyto at rest explains how the enhanced leakage may not affect substantially the average [Ca2+]cyto. Considering local values is then a necessary step in estimating the average [Ca2+]cyto in CSQ-KO fibers. This is critical, especially in view of the proposed mechanism that the augmented RyR1 leak could be functional in presaturating the troponin to preserve a normal force production despite the reduced SR calcium content and Ca2+ release in CSQ-KO fibers (1,10,17).

It is finally worth recalling that mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration is of outmost relevance for many biological processes such as regulation of ATP resynthesis, apoptosis, and proteostasis in health and disease (41,42). The control of mitochondrial Ca2+ in skeletal muscles is still debated, but there are clear indications that Ca2+ leakage from the SR leads to increased [Ca2+]mito, possibly enhancing ROS/RNS production and inducing mitochondrial dysfunction (43,44). In this regard, the role of MCU, electrochemical gradient, and local [Ca2+]cyto is not exhaustive and other components such as the Ca2+ efflux from mitochondria would require more attention.

Author contributions

L.M., C.R., and A.M. designed the research. L.M. performed numerical simulation. L.M., C.R., and A.M. analyzed the data. L.M., C.R., and A.M. wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the European Union via Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 886232 to L.M. We acknowledge the CINECA award under the ISCRA initiative for providing high-performance computing resources and support in the project HP10C6USIW. The code used for the mathematical model of the calcium diffusion in a resting sarcomere is available at https://github.com/ lorenzomarcucci/Skeletal-Caldiff.

Declaration of interests

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Editor: Howard Young.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpr.2023.100117.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Lamboley C.R., Pearce L., et al. Launikonis B.S. Ryanodine receptor leak triggers fiber Ca2+ redistribution to preserve force and elevate basal metabolism in skeletal muscle. Sci. Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abi7166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seng C., Pearce L., et al. Launikonis B.S. Tiny changes in cytoplasmic [Ca2+] cause large changes in mitochondrial Ca2+: What are the triggers and functional implications? Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022;323:C1285–C1289. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00092.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michelucci A., Paolini C., et al. Protasi F. Antioxidants protect Calsequestrin-1 knockout mice from halothane- and heat-induced sudden death. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:603–617. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paolini C., Quarta M., et al. Protasi F. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and cores in muscle from Calsequestrin-1 knockout mice. Skeletal Muscle. 2015;5:10. doi: 10.1186/s13395-015-0035-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michelucci A., Boncompagni S., et al. Protasi F. Estrogens protect Calsequestrin-1 knockout mice from lethal hyperthermic episodes by reducing oxidative stress in muscle. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/6936897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scorzeto M., Giacomello M., et al. Stienen G.J.M. Mitochondrial Ca2+-handling in fast skeletal muscle fibers from wild type and calsequestrin-null mice. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzuto R., Pozzan T. Microdomains of intracellular Ca2+: Molecular determinants and functional consequences. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:369–408. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dainese M., Quarta M., et al. Protasi F. Anesthetic- and heat-induced sudden death in Calsequestrin-1-knockout mice. FASEB J. 2009;23:1710–1720. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Protasi F., Paolini C., Dainese M. Calsequestrin-1: A new candidate gene for malignant hyperthermia and exertional/environmental heat stroke. J. Physiol. 2009;587:3095–3100. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paolini C., Quarta M., et al. Protasi F. Reorganized stores and impaired calcium handling in skeletal muscle of mice lacking Calsequestrin-1: Calsequestrin role in skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2007;583:767–784. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomasi M., Canato M., et al. Nori A. Calsequestrin (CASQ1) rescues function and structure of calcium release units in skeletal muscles of CASQ1-null mice. Aust. J. Pharm. Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C575–C586. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00119.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madsen K., Ertbjerg P., et al. Pedersen P.K. Calcium content and respiratory control index of skeletal muscle mitochondria during exercise and recovery. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.6.E1044. E1044–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalmers S., Nicholls D.G. The relationship between free and total calcium concentrations in the matrix of liver and brain mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:19062–19070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bazil J.N., Blomeyer C.A., et al. Dash R.K. Modeling the calcium sequestration system in isolated guinea pig cardiac mitochondria. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2013;45:177–188. doi: 10.1007/s10863-012-9488-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royer L., Sztretye M., et al. Ríos E. Paradoxical buffering of calcium by calsequestrin demonstrated for the calcium store of skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010;136:325–338. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fénelon K., Lamboley C.R.H., et al. Pape P.C. Calcium buffering properties of sarcoplasmic reticulum and calcium-induced Ca2+ release during the quasi-steady level of release in twitch fibers from frog skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 2012;140:403–419. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olojo R.O., Ziman A.P., et al. Ward C.W. Mice null for calsequestrin 1 exhibit deficits in functional performance and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium handling. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosca B., Delbono O., et al. Zorzato F. Enhanced dihydropyridine receptor calcium channel activity restores muscle strength in JP45/CASQ1 double knockout mice. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1541. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ríos E. The cell boundary theorem: A simple law of the control of cytosolic calcium concentration. J. Physiol. Sci. 2010;60:81–84. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0069-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michelucci A., Boncompagni S., et al. Dirksen R.T. Pre-assembled Ca2+ entry units and constitutively active Ca2+ entry in skeletal muscle of Calsequestrin-1 knockout mice. J. Gen. Physiol. 2020;152 doi: 10.1085/jgp.202012617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michelucci A., Pietrangelo L., et al. Boncompagni S. Constitutive assembly of Ca2+ entry units in soleus muscle from calsequestrin knockout mice. J. Gen. Physiol. 2022;154 doi: 10.1085/jgp.202213114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reggiani C., Marcucci L. A controversial issue: Can mitochondria modulate cytosolic calcium and contraction of skeletal muscle fibers? J. Gen. Physiol. 2022;154 doi: 10.1085/jgp.202213167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boncompagni S., Rossi A.E., et al. Protasi F. Mitochondria are linked to calcium stores in striated muscle by developmentally regulated tethering structures. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1058–1067. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cannell M.B., Allen D.G. Model of calcium movements during activation in the sarcomere of frog skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 1984;45:913–925. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcucci L., Canato M., et al. Reggiani C. A 3D diffusional-compartmental model of the calcium dynamics in cytosol, sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria of murine skeletal muscle fibers. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barclay C.J., Launikonis B.S. Components of activation heat in skeletal muscle. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2021;42:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10974-019-09547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flucher B.E. Structural analysis of muscle development: transverse tubules, sarcoplasmic reticulum, and the triad. Dev. Biol. 1992;154:245–260. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90065-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearce L., Meizoso-Huesca A., et al. Launikonis B.S. Ryanodine receptor activity and store-operated Ca2+ entry: Critical regulators of Ca2+ content and function in skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2022 doi: 10.1113/JP279512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Protasi F., Girolami B., et al. Paolini C. Ablation of Calsequestrin-1, Ca2+ unbalance, and susceptibility to heat stroke. Front. Physiol. 2022;13:1033300. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.1033300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Csordás G., Hajnóczky G. SR/ER-mitochondrial local communication: Calcium and ROS. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:1352–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meizoso-Huesca A., Pearce L., et al. Launikonis B.S. Ca2+ leak through ryanodine receptor 1 regulates thermogenesis in resting skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2119203119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durham W.J., Aracena-Parks P., et al. Hamilton S.L. RyR1 S-nitrosylation underlies environmental heat stroke and sudden death in Y522S RyR1 knockin mice. Cell. 2008;133:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baylor S.M., Hollingworth S. Simulation of Ca2+ movements within the sarcomere of fast-twitch mouse fibers stimulated by action potentials. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;130:283–302. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dash R.K., Beard D.A. Analysis of cardiac mitochondrial Na+ -Ca2+ exchanger kinetics with a biophysical model of mitochondrial Ca2+ handing suggests a 3: 1 stoichiometry: Characterization of mitochondrial NCE stoichiometry. J. Physiol. 2008;586:3267–3285. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.151977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vais H., Payne R., et al. Foskett J.K. Coupled transmembrane mechanisms control MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:21731–21739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005976117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mallilankaraman K., Cárdenas C., et al. Madesh M. MCUR1 is an essential component of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that regulates cellular metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:1336–1343. doi: 10.1038/ncb2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyman L., Greiser M., Lederer W.J. Calcium influx through the mitochondrial calcium uniporter holocomplex, MCUcx. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2021;151:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chelu M.G., Goonasekera S.A., et al. Hamilton S.L. Heat- and anesthesia-induced malignant hyperthermia in an RyR1 knock-in mouse. FASEB J. 2006;20:329–330. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4497fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanner J.T., Georgiou D.K., et al. Hamilton S.L. AICAR prevents heat-induced sudden death in RyR1 mutant mice independent of AMPK activation. Nat. Med. 2012;18:244–251. doi: 10.1038/nm.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canato M., Dal Maschio M., et al. Megighian A. Mechanical and electrophysiological properties of the sarcolemma of muscle fibers in two murine models of muscle dystrophy: col6a1-/- and mdx. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/981945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hood D.A., Memme J.M., et al. Triolo M. Maintenance of skeletal muscle mitochondria in health, exercise, and aging. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019;81:19–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Mario A., Gherardi G., et al. Mammucari C. Skeletal muscle mitochondria in health and disease. Cell Calcium. 2021;94 doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2021.102357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boncompagni S., Rossi A.E., et al. Protasi F. Characterization and temporal development of cores in a mouse model of malignant hyperthermia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:21996–22001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911496106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Canato M., Capitanio P., et al. Reggiani C. Excessive accumulation of Ca2 + in mitochondria of Y522S-RYR1 knock-in mice: A link between leak from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and altered redox state. Front. Physiol. 2019;10:1142. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.