Abstract

Currently, with the preference for a healthy diet and increased awareness of reducing the carbon footprint, the demand for protein is becoming more and more diversified. In this study, the physicochemical properties of yeast protein (YP) and four common plant proteins (soy protein isolate, pea protein isolate, wheat gluten, and peanut protein) were compared. The most prevalent secondary structure in YP is the β-sheet. Furthermore, YP is in an aggregated state, and it has a high surface hydrophobicity. The tryptophan residues are primarily exposed on the polar surface of YP. The results of in vitro digestibility indicated that YP (84.91 ± 0.52%) was a high-quality protein. Moreover, YP has a higher thermal stability and relatively stable low apparent viscosity, which provides ample possibility for its application in food processing and in foods for people with swallowing difficulties. This study provides theoretical basis in the potential of YP as an alternative protein source.

Keywords: Yeast protein, Plant protein, Structural characterization, Rheological properties, In vitro protein digestibility

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Yeast protein (YP) has higher thermal stability and stable apparent viscosity.

-

•

The physicochemical properties of YP were compared with those of plant proteins.

-

•

YP showed similar surface hydrophobicity to plant proteins.

-

•

YP was a protein with high digestibility in nutrition.

1. Introduction

The demand for high quality protein is rapidly increasing worldwide, due to the exponential growth of the global population and the pursuit of a healthy diet. There will be a significant “protein gap” between the current protein supply and the anticipated protein demand in 2050 (Jach et al., 2022). Despite the fact that animal protein remains a good protein source for food production, it has induced particular environmental issues for sustainability. For example, livestock farming discharges greenhouse gas (GHG) as well as occupies limited arable land and freshwater resources (Lin et al., 2022). In addition, studies have shown that a diet containing excessive amounts of red meat is strongly associated with some chronic diseases including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and colorectal cancer (Willett et al., 2019). As a result, there has been a trend towards alternative protein diets around the globe, and the main alternative proteins currently available are plant proteins.

Soy, pea, wheat, and peanut protein are the primary sources of plant proteins. However, they fall short of meeting the entire demand for protein among consumers. Due to the increasing rate of soil erosion and degradation throughout the world, the land availability has become a major constraint to plant protein food production (Fu et al., 2021). The yield of plant protein, on the other hand, is influenced by fresh-water resources as well as weather and seasons. Consequently, there is an urgent need for more sustainable, accessible, and healthy protein sources to partially or fully replace traditional protein sources. Microbial proteins have emerged as a promising protein source.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is currently the common strain used in more than 90% of the yeast and yeast-based products originate (Stam et al., 1998). It has a long history of safe consumption and has been a major focus of both fundamental and applied research (Karim et al., 2020). Yeast is inoculated in a fermenter with rich nutrients (molasses, etc.) and cultured through fermentation. The supernatant component of the enzymatic hydrolysis is used to make yeast extract for use as a food seasoning. The precipitation, which contains the majority of the proteins, is used to make yeast protein (YP). YP content is upwards of 70% and it contains all the essential amino acids required by the human body (Kurcz et al., 2018). In addition, YP contains trace minerals and B-vitamins (Jach and Serefko, 2018). Compared with bean protein, YP has no allergenic ingredients, non-beany taste, and no risk of genetic modification, which is suitable for the general population. Generally, the production of YP requires less arable land, reducing the waste of fresh-water resources and the emission of carbon dioxide. Therefore, it could be an excellent complement and unique alternative to animal and plant proteins and a real breakthrough in the current animal and plant protein-based protein market. YP is produced from agricultural, forestry, and industrial wastes, thus contributing to the elimination of contaminants and aiding in waste recycling (Jach et al., 2022). Consequently, using yeast to produce protein offers both beneficial nutrition and enhanced waste purification.

To our knowledge, YP is mainly used as protein components in feeds, there are fewer cases about the application of YP in food production. The contribution of YP as an alternative protein source has not received much attention in the literature yet. The ability of protein to satisfy the metabolic demands of the body depends on its quality status. A comprehensive understanding of the nutritional and physicochemical properties of YP through characterization is essential for their utilization in food processing products. Therefore, the present study is conducted to compare the physicochemical and nutritional properties of YP to those of common plant proteins including soy protein isolate (SPI), pea protein isolate (PPI), wheat gluten (WG), and peanut protein (PP). It is hoped to gain knowledge about the structural and nutritional properties of YP to promote its use as an alternative protein source in food processing. In conclusion, YP may become the best choice for human and animal nutrition in the future, with great significance in improving the problem of protein source shortage and increasing world food security.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

YP (82.4% protein), provided by AngelYeast Co., Ltd. SPI (91.4% protein, Linyi Shansong Biological Products Co., Ltd.), PPI (81.6% protein, Yantai Oriental Protein Technology Co., Ltd.), WG (77.5% protein, Fengqiu Huafeng powder Co., Ltd.), and PP (80% protein, Xi'an Chibacao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) are purchased from the market. Analytical-grade materials were used for all chemicals and reagents.

2.2. Surface morphology

The method described by Cui et al. (2021) was used to scan the surface morphology. The microstructure of protein samples was studied by viewing under a JSM-5800LV scanning electron microscope. The protein powder was covered with a thin layer of gold and taped to a circular aluminum specimen stub before the examination. The samples were photographed at an accelerating voltage of 5 KV and at 500, 3000, and 10000-fold magnifications.

2.3. Bulk density

The method of bulk density was measured according by Zhang et al. (2012). Pouring protein sample into a graduated cylinder, its volume was recorded, and the bulk density was calculated as g/mL.

2.4. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

The protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE according to the method reported by López-Monterrubio et al. (2020), with slight modifications. 125 g/L separating gel and 50 g/L stacking gel were prepared, respectively. The protein dispersions were obtained (2 mg/mL) in phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0). 10 μL protein dispersion including 1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol was loaded into the lane for electrophoresis. Electrophoresis was performed on the Bio-Rad Mini-Protein apparatus.

The sample was first run at 60 V to the top of the separating gel, then, run at 120 V until the sample reached the reference line. The gel was stained with Coomassie Bright Blue for 40 min, and then the gel with the decolorizing solution was used to decolorization.

2.5. Surface hydrophobicity (H0)

H0 values of protein samples were determined using ANS (8-anilino-1-naphthalene sulfonic acid) as a fluorescence probe, as reported by Gao et al. (2022), with minor modification. Protein sample dispersions were serially diluted with 0.01 M phosphate buffer solution pH 7.0 to obtain protein concentrations ranging from 0.0375 to 0.6 (mg/mL). Subsequently, 20 μL of ANS (8.0 mM in 0.01 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) was mixed with 4 mL protein samples and reacted in the dark for 10 minutes. Fluorescence intensity (FI) was measured with a fluorescence spectrophotometer (F-4600, Hitachi, Inc. Japan), at wavelengths of 390 nm (excitation) and 470 nm (emission), with a constant slit of 5 nm for both excitation and emission. The hydrophobicity value of the protein surface was obtained by calculating the initial slope of FI versus protein concentration plot. Each analysis was done in triplicate.

2.6. Intrinsic fluorescence and ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy

The intrinsic fluorescence and ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy were determined based on the method of Du et al. (2022), with some modifications. A fluorescence spectrometer (F-4600, Hitachi, Inc. Japan) was used to detect the fluorescence of the samples. The protein samples were diluted to 0.2 mg/mL with 10 mM pH=7.0 phosphate buffer. The excitation wavelength was 280 nm, and the emission spectra measured ranged from 290 to 450 nm. The slit width was constant at 5 nm for both excitation and emission, the scan speed and voltage were 1200 nm/min and 700 V, respectively. All the measurements were conducted in triplicate.

The protein samples were dissolved in distilled water with a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. Absorbance was recorded from 240 to 400 nm at 25 °C with a 1 cm path-length quartz cell by a UV2355 ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer. A background scan was performed before the first sample measurement. All the measurements were conducted in triplicate.

2.7. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR was used to characterize the protein secondary structures (Cui et al., 2021). Freeze-dried protein sample (1 mg) was combined with dried KBr (100 mg), followed by fully grinding. Then the mixtures were pressed from powder to a transparent flake. The infrared spectroscopy of protein samples was collected using an infrared spectrometer (Nicolet iS10, USA) in the frequency range of 4000–500 cm-1 at a resolution of 4 cm-1 and 64 times scan. The curve of infrared spectroscopy was analyzed by Omnic 9.2 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, USA) and Peakfit 4.12 software (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) with baseline correcting, smooth, Fourier deconvoluting, and Gaussian peak fitting.

2.8. In vitro protein digestibility (IVPD)

The method of López-Monterrubio et al. (2020) was used for the determination of IVPD of YP and four plant protein samples, using a multi-enzyme system included 1.6 mg trypsin (14,600 U/mg), 3.1 mg α-chymotrypsin (48 U/mg) and 1.3 mg peptidase (102 U/g) per mL. 50 mL of protein suspensions (1 mg N/mL) were prepared and use a magnetic stirrer to disperse them evenly. Subsequently, the suspensions were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and the pH was adjusted to 8.0 by using 0.2 M NaOH. Five milliliters of the multi-enzyme solution were then added to each protein suspension which was kept at 37 °C in a water bath shaker and the pH was recorded by a pH meter (ST300, OHAUS, USA) after 10 minutes. The percent IVPD was calculated by the following equation:

| (1) |

Where: pH10min is the pH value of the solution measured by pH meter after 10 min of enzymatic digestion.

2.9. Rheological properties

The rheological properties of YP and four plant protein samples were determined by the method of Syed et al. (2022) with slight modifications. A 15% protein solution was prepared and stirred at 900 r/min for 2 h, then stored at 4 °C overnight. Rheological tests were carried out on a rheometer with plate geometry (40 mm diameter) and the shear test was performed at 25 °C with a shear rate range of 1–100 s-1. The sample was loaded on the rheometer plate and stabilized for 2 minutes. A thin layer of low-viscosity paraffin oil was added to the edge of the sample to avoid evaporation during measurement.

2.10. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The TGA of samples was determined by Zhang et al. (2019) with a few modifications. The thermostability of samples was measured using a thermogravimetric analyzer (Mettler Toledo Thermogravimetric Analyzer TGA2). Each protein sample (about 5 mg) was put into an oxidized aluminum pan and heated from 40 °C to 550 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min in a nitrogen atmosphere at a rate of 30 mL/min, and the change in weight loss and the curve of the inverse change in weight loss of the samples were recorded.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using a one factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) and differences among the individual means were compared by Duncan's multiple range test. Significance of differences was set at the P < 0.05 level. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

3. Result and discussion

3.1. Surface morphology

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) examination was commonly used to characterize the microscopic surfaces morphological information of biological materials (Merrett et al., 2002). Surface morphology of YP and four plant protein samples was studied using SEM. As shown in Fig. 1, the distinctive differences in SEM images of YP and four protein samples were observed. YP exhibited a relatively dense spherical structure and a rough surface. Moreover, there are almost no pores on its surface. Conversely, the SPI and PPI powder emerged with shriveled or collapsed shapes. As a matter of fact, both SPI and PPI samples exhibited similar particle morphology. However, SPI is accompanied by caking on the surface, while PPI demonstrated many smaller particles around the bigger ones and some folding and hollow. This is consistent with the observations of Cui et al. (2020). From the micrographs, it was viewed that non-homogeneous particles of various sizes and shapes were discovered in both the WG and PP. Seen from Fig. 1, there are many cracks as well as caking on the WG surface and it shows a loose and porous morphology. At the same time, PP particles were observed of different sizes, sometimes spherical and at other times irregular, having in both cases a rough surface. The SEM showed the difference particle sizes between proteins, and the particle size in turn could affects the rate of protein dissolution (Kumarakuru et al., 2018).

Fig. 1.

The SEM images of YP and other four plant protein samples.

Note: YP (yeast protein), SPI (soy protein isolate), PPI (pea protein isolate), WG (wheat gluten), PP (peanut protein), and SEM (scanning electron microscopy). All experiments were repeated at least three times.

3.2. Bulk density

Bulk density and particle size are connected and affect packaging requirements. Low bulk density powders necessitate larger containers per unit weight (Kinsella and Morr, 1984). As shown in Table 1 (P<0.05), the bulk density of YP was 0.61 ± 0.01 g/mL, which was less in comparison with WG (0.71 g/mL), but higher than SPI (0.45 ± 0.01 g/mL), PPI (0.52 ± 0.01 g/mL), and PP (0.56 ± 0.01 g/mL). The higher the bulk density value, the smaller the pores between the protein particles.

Table 1.

The bulk density of protein samples.

| Samples | Bulk Density (g/mL) |

|---|---|

| YP | 0.61 ± 0.01d |

| SPI | 0.45 ± 0.01a |

| PPI | 0.52 ± 0.01b |

| WG | 0.71 ± 0.00e |

| PP | 0.56 ± 0.01c |

Note: Values within columns with different lowercase(s) indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

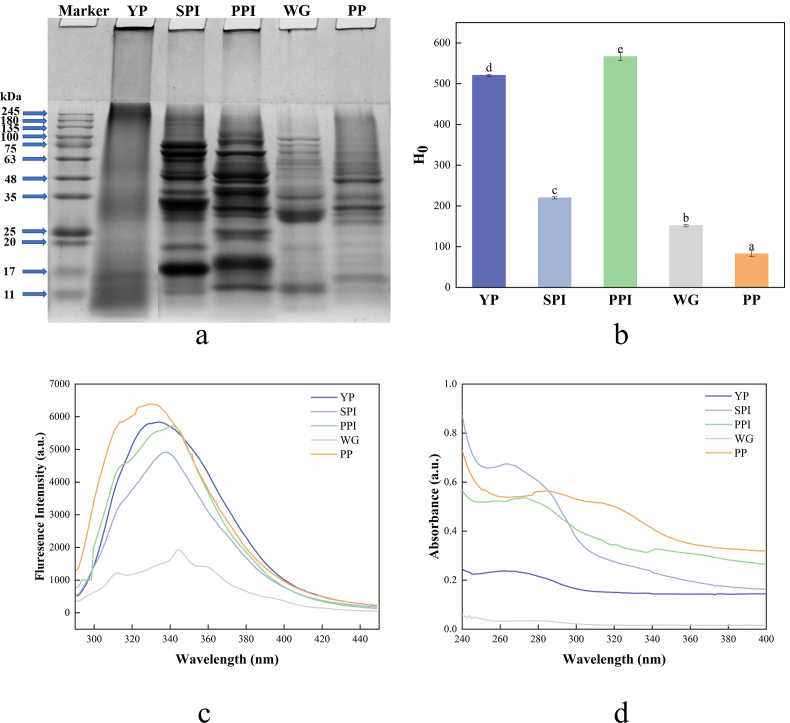

3.3. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

The reducing agent (mercaptoethanol) disrupted the disulfide bond and the hydrophobic interactions between protein subunits, leading to the dissociation of the subunits (Ma et al., 2022). Therefore, the differences in subunit compositions of YP and four plant protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Generally, cross-linked protein polymers or protein aggregates occurred at molecular weights higher than 245 kDa, in other words, they accumulated at the top of the gel (Ke and Huang, 2016). As shown in Fig. 2a, large protein polymers are formed at the top of the separation gel for YP, in addition, the lane showed trailing phenomenon and it has no distinct characteristic band was observed. However, multiple slight bands were still seen in the electrophoresis of YP samples with molecular weight ranging from 11 to 17 kDa, 25 to 35 kDa, and 48 to 63 kDa, indicating that YP is composed of several protein or protein fragments with different molecular weights.

Fig. 2.

The structural properties of YP and other four plant protein samples. (a) SDS-PAGE, (b) H0, (c) Intrinsic fluorescence spectra, (d) Ultraviolet spectra. The different lowercase indicates significant differences (P < 0.05).

Note: YP (yeast protein), SPI (soy protein isolate), PPI (pea protein isolate), WG (wheat gluten), PP (peanut protein), SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis), and H0 (surface hydrophobicity). All experiments were repeated at least three times.

The electrophoretic pattern of SPI showed typical SPI electrophoresis bands: 11S globin and 7S globin featured bands can be clearly observed. 11S globulins contains six acidic polypeptide chains with molecular weights between 37 and 45 kDa. The electrophoretic profile of PPI revealed numerous bands ranging from roughly about 15 to 80 kDa. PPI can be further classified as 11S legumin, 7S vicilin, and convicilin. From the Fig. 2a, one of the typical polypeptide fragments of the 11S legumin: basic (leg β, ∼20 kDa) and it is possible to see convicilin, which has a molecular weight of about 70 kDa, and 7S vicilin, which has a molecular weight of about 50 kDa. Vicilin subunits were assumed to be the PPI electrophoretic bands with a molecular weight below 46 kDa (Cui et al., 2020). The bands of WG and PP are mostly located between 35 kDa and 100 kDa, and all exhibited very weak bands at low molecular weight. The results presented that the subunit composition of YP, WG, and PP are relatively simple in comparison with SPI and PPI, which had complicated proteins with a higher number of bands and intensities.

3.4. Surface hydrophobicity (H0)

H0, an index of the content of hydrophobic groups on the protein surface, plays a significant role in the functional properties of the protein. The formation of hydrophobicity on the protein surface is due to the side chains of amino acid residues that are exposed to the protein surface and tend to aggregate (Wang et al., 2022). Hydrophobicity is the main force that maintains the tertiary structure of protein and has an essential influence on the functional role of protein in non-polar systems. ANS is an extremely sensitive fluorescent probe that nonspecifically binds to the hydrophobic areas of protein molecules, and the exposure of hydrophobic groups in protein measured by fluorescence spectroscopy (Gao et al., 2022). The H0 value results of YP and plant protein samples are presented in Fig. 2b. It is evident from the data that PPI had the highest H0 value (566.52 ± 10.04), followed by that of YP (520.56 ± 2.56). Their H0 values were much higher than that of SPI (220.04 ± 2.86), WG (151.75 ± 3.05), and PP (82.71 ± 7.28). Thus, it can be concluded that YP has more non-polar amino acid content and non-polar chemical bonds. In other words, there are more hydrophobic regions distributed on the surface of the YP that can be available for ANS binding. The hydrophobic residues exposed on the surface of the molecule are extensively involved in intermolecular interactions and reduce the solubility of the protein. Studies have shown that H0 is also considered to be an important factor affecting protein solubility and emulsifying properties and these characteristics are required for a specific food product application, such as beverages or emulsified foods. (Mao and Hua, 2012). The H0 value is positively correlated with emulsifying properties, the higher the H0 values are, the better the emulsification property and emulsion stability show (Gong et al., 2016). Therefore, YP could be used as a protein additive to prepare emulsification-based products, such as salad dressings and ice creams.

3.5. Intrinsic fluorescence and ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy analysis

The intrinsic fluorescence and ultraviolet-visible are related to aromatic amino acids, and they were generally used to monitor the tertiary-structural changes in protein, such as protein folding, unfolding, and association (Cui et al., 2013). The difference in protein tertiary structure is shown by changes in the maximum wavelength (λmax) and fluorescence intensity. When excited at 280.0 nm, the intrinsic fluorescence of protein was attributed to the fluorescence of tryptophan (Trp) residues and the peak position is between 325.0 nm and 350.0 nm (Jiang et al., 2015). When Trp residues are buried in the protein's hydrophobic core, λmax is usually <330.0 nm. However, in a polar environment, λmax shifts to a longer wavelength (red shifts) (Wang et al., 2017).

The comparison of fluorescence spectroscopy of YP and four plant protein samples is presented in Fig. 2c. The results showed that the λmax for YP occurred at 344.6 nm, which was the same λmax as WG. However, the fluorescence spectroscopy acquired from YP and WG not exhibited the same fluorescence intensity at the λmax. It was observed that YP showed a higher fluorescence intensity with 5486.50 a.u. than that of WG (1927.70 a.u.). This phenomenon implied that the content of Trp residues in YP was higher than that in WG. Simultaneously, it could be found that the maximum peak positions of SPI, PPI, and PP appeared at 337.6, 341.6, and 329.6 nm, respectively. Compared with SPI, PPI, and PP, the λmax of YP showed a slight right shift. This shift depended on the position of Trp residues in the protein molecule. The λmax values above 330.0 nm indicate that more Trp residues are exposed to the polar surface of the protein (Li et al., 2018).

The ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy reflects the absorption of ultraviolet light by the side chain groups of aromatic amino acids as well as histidine and cysteine residues in the protein (T. Zhang et al., 2022). Consequently, the changes in protein structure could be inferred based on the position of the characteristic absorption peak. The ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy of YP and four plant protein samples are illustrated in Fig. 2d. Due to variations in the amounts of the amino acids Tyr, Trp, and phenylalanine, different proteins have different absorption peaks. The absorption peak of YP and SPI occurring at 263.0 nm are 0.24 a.u. and 0.67 a.u., respectively. The results indicated that the aromatic amino acid content in YP was low. The absorption peaks of PPI and PP are 271.0 nm (0.54 a.u.) and 284.0 nm (0.56 a.u.), respectively. The absorption peak of WG is less pronounced at 275.0 nm (0.03 a.u.). A similar observation has been reported for wheat germ protein (Wang et al., 2020). When compared to SPI, PPI, and PP, YP's absorption peak is less prominent, and it exhibits a relatively steady UV absorption intensity that does not shift noticeably with absorption wavelength. The above results indicated that YP is in an aggregated state and exposed fewer chromophore groups to solvent, which is consistent with the results observed by intrinsic fluorescence.

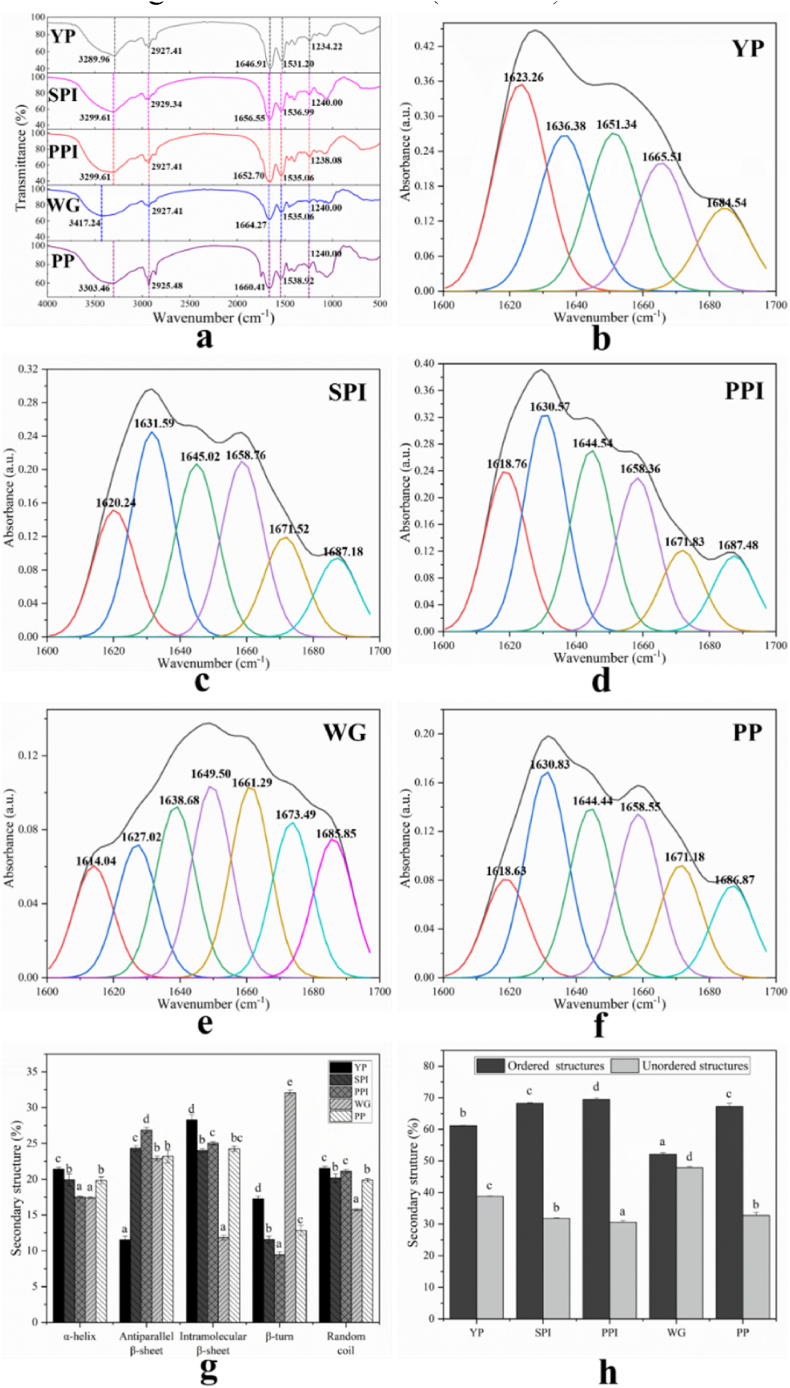

3.6. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

Infrared spectroscopy is a popular method to study the secondary structure of the protein. In infrared spectroscopy, the amide I (1600–1700 cm-1) region of the protein infrared spectrum is used for the secondary structure analysis of protein. The amide I region of the infrared spectrum of protein is dominated by the stretching vibrations of the C O bond (Pelton and McLean, 2000). The FTIR spectra of YP and four plant protein samples are shown in Fig. 3. The absorption peak of YP appeared at 3289.96 cm-1 (amide A associated with N–H stretching coupled with hydrogen bonding), 2927.41 cm-1 (amide B, –CH stretching vibration), 1646.91 cm-1 (amide I, C–O stretching), 1531.20 cm-1 (amide II, N–H bending), and 1234.22 cm-1 (amide III C–N stretching and N–H deformation) (Yan et al., 2021). We could conclude that the five peak positions of YP are similar to those of SPI and PPI.

Fig. 3.

The secondary structures of YP and other four plant protein samples. (a) FTIR spectra, (b) Fourier self-deconvoluted of YP for curve-fitted amide I band, (c) Fourier self-deconvoluted of SPI for curve-fitted amide I band, (d) Fourier self-deconvoluted of PPI for curve-fitted amide I band, (e) Fourier self-deconvoluted of WG for curve-fitted amide I band, (f) Fourier self-deconvoluted of PP for curve-fitted amide I band, (g) Secondary structures, (h) Ordered and unordered structures. The different lowercase indicates significant differences (P < 0.05).

Note: YP (yeast protein), SPI (soy protein isolate), PPI (pea protein isolate), WG (wheat gluten), PP (peanut protein), and FTIR (fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy). All experiments were repeated at least three times.

To detailly observe the composition of secondary structure, plotted was performed in the amide I region as shown in Fig. 3(b-f). In the amide I region, the spectrum of the YP was composed of five bands located at 1623.26 cm-1, 1636.38 cm-1, 1651.34 cm-1, 1665.51 cm-1, and 1684.54 cm-1, while SPI, PPI, and PP had six spectral bands and WG has seven spectral bands. Obviously, the position and absorbance value of the peaks were different between YP and four plant protein samples.

The percentages of α-helix, β-sheet, β-turn, and random coil were calculated (Fig. 3g). In general, the β-sheet is the most abundant secondary structure element of the YP, followed by α-helix, random coil, and β-turn. The high percentage of β-sheet (hydrophobic) implied the high hydrophobicity, which was also demonstrated in the result of the H0 value (Cui et al., 2021). β-sheet often exists in insoluble aggregates, and the intramolecular β-sheet content also represents the degree of aggregation of protein molecules, which further supports the conjecture of poor solubility of YP (Srisailam et al., 2002). The high content of α-helix prevents protein gelation, and more β-sheets promote the formation of protein networks (W. Zhang et al., 2022). Compared to the other four plant proteins, YP contains the highest content of α-helix, which could make it difficult for YP to form gels. The secondary structure of SPI was mainly composed of β-sheet and random coil, which was consistent with the results of Yan et al. (2021). In the PP, the highest proportion of secondary structure elements corresponds to the β-sheet, which is the same as the conclusion reached by Guo et al. (2019). The comparison of the ordered and disordered structures of YP and four plant protein samples is shown in Fig. 3h. The α-helix and β-sheet indicated the ordered structure of the protein, while the β-turn and random coil indicated the disordered structure of the protein (Vanga et al., 2020). In YP, ordered structures are roughly twice as common as disordered ones.

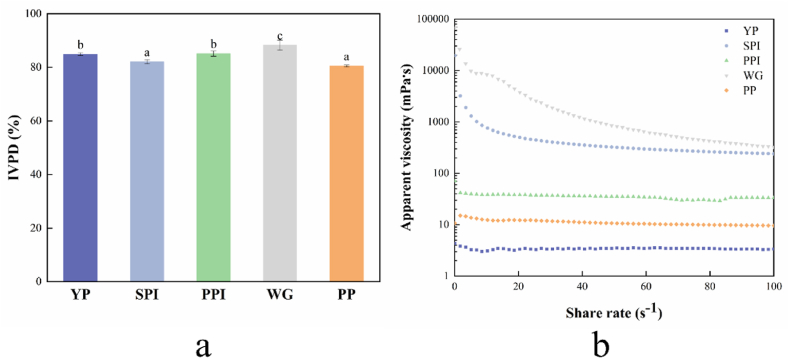

3.7. In vitro protein digestibility (IVPD)

The digestibility of protein is a key index to evaluate the bioavailability of protein, and it is also an important characteristic for estimating protein quality. Studies have shown that the structure and composition of the protein, the effective contact area between the protein and proteolytic enzyme, and the aggregation of the protein all affected the digestive efficiency (Dyer and Grosvenor, 2014). Hence, the relationship between structural and nutritional properties is closely related. Generally, a higher digestibility will be provided by the protein containing lower levels of β-sheet because a high content of β-sheet structure reduces accessibility of proteolytic enzymes (Yu, 2005).

The IVPD of YP and four plant protein samples are presented in Fig. 4a. The IVPD of all protein samples was above 80%. It was observed that the IVPD of WG (88.28 ± 1.89%) ranked first, which is consistent with the results obtained by FTIR that WG has a lower content of β-sheet. Meanwhile, it was also observed that the IVPD of YP (84.91 ± 0.52%) was similar to the IVPD of PPI (85.15 ± 0.10%). The results confirmed that YP is a high-quality protein with high digestibility.

Fig. 4.

The in vitro digestibility and rheological properties of YP and other four plant protein samples. (a) in vitro digestibility, (b) Apparent viscosity. The different lowercase indicates significant differences (P < 0.05).

Note: YP (yeast protein), SPI (soy protein isolate), PPI (pea protein isolate), WG (wheat gluten), PP (peanut protein), and IVPD (in vitro protein digestibility). All experiments were repeated at least three times.

3.8. Rheological properties

Analysis of rheological properties helps explain how molecular-scale and macroscopic features relate to one another. Foods and beverages' acceptability among consumers is influenced by the viscosity of the item (Syed et al., 2022). The molecular weight, composition, protein size and shape, level of hydration, and intermolecular interaction all affect the rheological properties of protein solution (Alizadehfard and Wiley, 1996). Fig. 4b showed the flow curves of YP and four plant protein samples with changes in shearing rate. It can be seen from Fig. 4b that the apparent viscosity of YP was relatively low and the shear rate had no apparent effect on the apparent viscosity of YP. The apparent viscosity of the YP was stable with an increase in shearing force, which was similar to the changes in PPI and PP. However, the overall apparent viscosity of YP is less than that of PPI and PP. The phenomenon may be attributed to the difference in the degree of protein aggregation. In contrast, the apparent viscosity of SPI and WG showed a decrease with the increase of shear rate, exhibiting a shear-thinning behavior (pseudoplastic fluid). For both proteins, WG showed the most pseudoplastic properties. According to the findings, YP has the lowest apparent viscosity, making it a potential raw material in the development of dysphagia foods since it allows for the production of goods with a lower viscosity texture; low-viscosity foods require less time and effort to process, which is easier for consumers with the disease (Pure et al., 2021).

3.9. Thermogravimetric properties

When a protein denatures, its molecular structure transforms from an ordered to a disordered state, and intramolecular hydrogen bonds could be disrupted. The degree of protein denaturation could be evaluated by the protein's thermodynamic properties because these changes will result in energy changes (Peng et al., 2022). The thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) curve shows the weight loss of substance in the relation to the temperature of thermal degradation, while the derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curve shows the corresponding weight-loss rate (Zhang et al., 2019).

As shown in Fig. 5a, the protein samples showed similar TGA curves, the weight loss of all protein samples that occurred at the beginning was attributed to the evaporation of water. The hydrogen bonds in hydrophilic components were damaged by high temperatures during this stage. Therefore, the absorbed and bound water was released resulting in a reduction of mass (Zhao et al., 2017). At a temperature range of 200 °C–400 °C, the maximum weight loss of protein mainly corresponded to the cleavage of non-covalent bonds (Mir et al., 2021). The degradation rate of YP was the slowest with the increase of temperature. This indicates that the degree of crosslinking between YP molecules could be higher, which resulted in higher thermal stability (Malik et al., 2017). While the degradation rate of WG was the fastest, hence it has poor thermal stability. The differences in weight loss between samples were mainly embodied in the rate of weight change, which can be observed in Fig. 5b. Two endothermic peaks appeared in all curves, the first weight loss process in the TGA curve, which is the one brought on by the elimination of water from the sample. The second peak was due to the loss of protein and corresponds to the second weight loss process shown in the TGA curve (Malik et al., 2017). The maximum degree of weight loss for all protein samples occurred between 200 and 400 °C, with the highest peak detected at 275–375 °C. The maximum weight loss peak of YP was located on the rightmost side, indicating that it has the highest thermal stability. In addition, at a temperature range of 375 °C–400 °C, the weight loss rate of YP increased with increasing temperature. A high weight loss rate is associated with more structural changes and cleavage of bonds in the protein (Mir et al., 2021).

Fig. 5.

The thermal properties of YP and other four plant protein samples. (a) TGA, (b) DTG.

Note: YP (yeast protein), SPI (soy protein isolate), PPI (pea protein isolate), WG (wheat gluten), PP (peanut protein), TGA (thermal gravimetric analysis), and DTG (derivative thermogravimetric). All experiments were repeated at least three times.

4. Conclusion

For the first time, common plant proteins and yeast protein were compared in this study and the structural properties, rheological properties, thermal properties, and IVPD of the proteins were systematically compared. The results of the structural properties indicated that the bulk density of YP was 0.61 ± 0.01, which was slightly lower than those of WG, and higher than those of the other three plant proteins. Protein has a lower bulk density, which could save packing materials and transportation costs. Meanwhile, YP has a higher H0 value (520.56 ± 2.56). Compared to the other four plant proteins, YP contains the highest amount of α-helix, which makes it challenging for YP to form gels. In order to produce gel food, YP could be modified using physical, chemical, and enzymatic methods. The IVPD results suggested that YP was a protein with high digestibility. The results of rheological properties show that YP has a low apparent viscosity and could be used as a component in the development of dysphagia foods. The results of the thermal properties display that the high thermal stability of YP provides full possibilities for its application in food fields.

Therefore, this study may be of interest for the food industry to develop new protein products and functional ingredients. As a sustainable and green microbial protein, YP can fill the protein shortage. Therefore, further work should be done to investigate the physicochemical and processing properties of YP. Besides this, it is worthwhile further to explore the relationship between structural and functional properties to provide guidance for subsequent product development.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chengxin Ma: Methodology, Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Songgang Xia: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Jian Song: Methodology, Investigation. Yukun Hou: Methodology, Investigation. Tingting Hao: Methodology, Investigation. Shuo Shen: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Ku Li: Resources, Funding acquisition. Changhu Xue: Funding acquisition, Supervision. Xiaoming Jiang: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest and no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgment

This research was financially supported by Key Technology Research and Development Program of Shandong (2021SFGC0701) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (202213026).

Handling Editor: Dr. Xing Chen

Contributor Information

Chengxin Ma, Email: machengxin0105@163.com.

Songgang Xia, Email: songgang_xia@163.com.

Jian Song, Email: slz928557854@163.com.

Yukun Hou, Email: Houyk99@163.com.

Tingting Hao, Email: ting_h@yeah.net.

Shuo Shen, Email: shenshuo@angelyeast.com.

Ku Li, Email: liku@angelyeast.com.

Changhu Xue, Email: xuech@ouc.edu.cn.

Xiaoming Jiang, Email: jxm@ouc.edu.cn.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Alizadehfard M.R., Wiley D.E. Non-Newtonian behaviour of whey protein solutions. J. Dairy Res. 1996;63(2):315–320. doi: 10.1017/s0022029900031812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C., Zhao M., Yuan B., Zhang Y., Ren J. Effect of pH and pepsin limited hydrolysis on the structure and functional properties of soybean protein hydrolysates. J. Food Sci. 2013;78(12):C1871–C1877. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L., Bandillo N., Wang Y., Ohm J.-B., Chen B., Rao J. Functionality and structure of yellow pea protein isolate as affected by cultivars and extraction pH. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q., Wang L., Wang G., Zhang A., Wang X., Jiang L. Ultrasonication effects on physicochemical and emulsifying properties of Cyperus esculentus seed (tiger nut) proteins. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.110979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Zhang J., Wang S., Manyande A., Wang J. Effect of high-intensity ultrasonic treatment on the physicochemical, structural, rheological, behavioral, and foaming properties of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.)-seed protein isolates. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2022;155 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer J.M., Grosvenor A. Food Structures, Digestion Health. 2014. Novel approaches to tracking the breakdown and modification of food proteins through digestion; pp. 303–317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Chen T., Chen S.H.Y., Liu B., Sun P., Sun H., Chen F. The potentials and challenges of using microalgae as an ingredient to produce meat analogues. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;112:188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.03.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K., Zha F., Yang Z., Rao J., Chen B. Structure characteristics and functionality of water-soluble fraction from high-intensity ultrasound treated pea protein isolate. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;125 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.107409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong K.-J., Shi A.-M., Liu H.-Z., Liu L., Hu H., Adhikari B., Wang Q. Emulsifying properties and structure changes of spray and freeze-dried peanut protein isolate. J. Food Eng. 2016;170:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2015.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S., Ai M., Liu J., Luo Z., Yu J., Li Z., Jiang A. Physicochemical, conformational properties and ACE-inhibitory activity of peanut protein marinated by aged vinegar. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2019;101:469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.11.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jach M.E., Serefko A. Diet, Microbiome and Health. 2018. Nutritional yeast biomass: characterization and application; pp. 237–270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jach M.E., Serefko A., Ziaja M., Kieliszek M. Yeast protein as an easily accessible food source. Metabolites. 2022;12(1) doi: 10.3390/metabo12010063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Wang Z., Li Y., Meng X., Sui X., Qi B., Zhou L. Relationship between surface hydrophobicity and structure of soy protein isolate subjected to different ionic strength. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015;18(5):1059–1074. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2013.865057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karim A., Gerliani N., Aïder M. Kluyveromyces marxianus: an emerging yeast cell factory for applications in food and biotechnology. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020;333 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Z., Huang Q. Haem-assisted dityrosine-cross-linking of fibrinogen under non-thermal plasma exposure: one important mechanism of facilitated blood coagulation. Sci. Rep-uk. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep26982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella J.E., Morr C.V. Milk proteins: physicochemical and functional properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1984;21(3):197–262. doi: 10.1080/10408398409527401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumarakuru K., Reddy C.K., Haripriya S. Physicochemical, morphological and functional properties of protein isolates obtained from four fish species. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018;55:4928–4936. doi: 10.1007/s13197-018-3427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurcz A., Błażejak S., Kot A.M., Bzducha-Wróbel A., Kieliszek M. Application of industrial wastes for the production of microbial single-cell protein by fodder yeast Candida utilis. Waste Biomass Valori. 2018;(9):57–64. doi: 10.1007/s12649-016-9782-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Chu S., Lu J., Wang P., Ma M. Molecular and structural properties of three major protein components from almond kernel. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018;42(3) doi: 10.1111/jfpp.13536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q., Pan L., Deng N., Sang M., Cai K., Chen C., Han J., Ye A. Protein digestibility of textured-wheat-protein (TWP) -based meat analogues: (I) Effects of fibrous structure. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;130 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.107694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López-Monterrubio D.I., Lobato-Calleros C., Alvarez-Ramirez J., Vernon-Carter E.J. Huauzontle (Chenopodium nuttalliae Saff.) protein: composition, structure, physicochemical and functional properties. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., Li L., Wu C., Huang Y., Teng F., Li Y. Effects of combined enzymatic and ultrasonic treatments on the structure and gel properties of soybean protein isolate. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2022;158 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X., Hua Y. Composition, structure and functional properties of protein concentrates and isolates produced from walnut (Juglans regia L.) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13(2):1561–1581. doi: 10.3390/ijms13021561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik M.A., Sharma H.K., Saini C.S. Effect of gamma irradiation on structural, molecular, thermal and rheological properties of sunflower protein isolate. Food Hydrocolloids. 2017;72:312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merrett K., Cornelius R.M., McClung W.G., Unsworth L.D., Sheardown H. Surface analysis methods for characterizing polymeric biomaterials. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2002;13(6):593–621. doi: 10.1163/156856202320269111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir N.A., Riar C.S., Singh S. Rheological, structural and thermal characteristics of protein isolates obtained from album (Chenopodium album) and quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) seeds. Food Hydrocolloids Health. 2021;1 doi: 10.1016/j.fhfh.2021.100019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelton J.T., McLean L.R. Spectroscopic methods for analysis of protein secondary structure. Anal. Biochem. 2000;277(2):167–176. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H., Zhang J., Wang S., Qi M., Yue M., Zhang S.…Ma C. High moisture extrusion of pea protein: effect of l-cysteine on product properties and the process forming a fibrous structure. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;129 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.107633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pure A.E., Yarmand M.S., Farhoodi M., Adedeji A. Microwave treatment to modify textural properties of high protein gel applicable as dysphagia food. J. Texture Stud. 2021;52(5-6):638–646. doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisailam S., Kumar T.K.S., Srimathi T., Yu C. Influence of backbone conformation on protein aggregation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124(9):1884–1888. doi: 10.1021/ja012070r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam H., Hoogland M., Laane C. Food flavours from yeast. Microbiology of Fermented Foods. 1998:505–542. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0309-1_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syed R., Ding H.H., Hui D., Wu Y. Physicochemical and functional properties of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) protein and non-starch polysaccharides. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre. 2022;28 doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2022.100317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanga S.K., Wang J., Orsat V., Raghavan V. Effect of pulsed ultrasound, a green food processing technique, on the secondary structure and in-vitro digestibility of almond milk protein. Food Res. Int. 2020;137 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., You S., Wang W., Zeng Y., Su R., Qi W., Wang K., He Z. Laccase-catalyzed soy protein and gallic acid complexation: effects on conformational structures and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2022;375 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Sun D.-W., Pu H., Wei Q. Principles and applications of spectroscopic techniques for evaluating food protein conformational changes: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017;67:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Tang Y., Yang Y., Zhao J., Zhang Y., Li L., Wang Q., Ming J. Interaction between wheat gliadin and quercetin under different pH conditions analyzed by multi-spectroscopy methods. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020;229 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W., Rockström J., Loken B., Springmann M., Lang T., Vermeulen S.…Murray C.J.L. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet Discovery Science. 2019;393(10170):447–492. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S., Xu J., Zhang S., Li Y. Effects of flexibility and surface hydrophobicity on emulsifying properties: ultrasound-treated soybean protein isolate. LWT--Food Sci. Technol. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.110881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P. Multicomponent peak modeling of protein secondary structures: comparison of Gaussian with lorentzian analytical methods for plant feed and seed molecular biology and chemistry research. Appl. Spectrosc. 2005;59(11) doi: 10.1366/000370205774783151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Wang J., Feng J., Liu Y., Suo R., Ma Q., Sun J. Effects of ultrasonic–microwave combination treatment on the physicochemical, structure and gel properties of myofibrillar protein in Penaeus vannamei (Litopenaeus vannamei) surimi. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;90 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Boateng I.D., Zhang W., Jia S., Wang T., Huang L. Effect of ultrasound-assisted ionic liquid pretreatment on the structure and interfacial properties of soy protein isolate. Process Biochem. 2022;115:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2022.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang B., Zhang W., Xu W., Hu Z. Effects and mechanism of dilute acid soaking with ultrasound pretreatment on rice bran protein extraction. J. Cereal. Sci. 2019;87:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2019.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Song H., Peng Z., Luo Q., Ming J., Zhao G. Characterization of stipe and cap powders of mushroom (Lentinus edodes) prepared by different grinding methods. J. Food Eng. 2012;109(3):406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2011.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Sun N., Li Y., Cheng S., Jiang C., Lin S. Effects of electron beam irradiation (EBI) on structure characteristics and thermal properties of walnut protein flour. Food Res. Int. 2017;100:850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.