Abstract

Objective:

Road traffic injuries to youth are a serious global public health concern. One contributor to adolescent injury risk is the tendency to engage in sensation seeking behaviors. The current study examined how sensation seeking personality might directly influence adolescent traffic injury, as well as how it might indirectly influence traffic injury as mediated by road safety attitudes, intentions, and behaviors.

Methods:

4470 adolescents of 10–15 years were recruited from 29 primary and secondary schools in China. Youth completed several self-report questionnaires, including measures of sensation seeking, road safety attitudes and intentions, and road user behaviors. Spearman correlations and logistic regression tested the direct effects of sensation seeking, road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions, and road user behaviors on traffic injury. Structural Equation Modeling evaluated a multiple mediation model of road safety attitudes, intentions, and behaviors as mediators of the association between sensation seeking and adolescent traffic injury.

Results:

Correlation coefficients between traffic injury and the other variables ranged from 0.01 to 0.15, with moderate relations emerging between adolescent traffic injury and most other variables. Logistic regression analysis showed that Disinhibition sensation seeking, road safety attitudes, and road user behaviors predicted adolescent traffic injury significantly (OR = 1.03, 0.35, 2.99, respectively). The multiple mediation model analysis indicated that, after controlling for adolescent gender and age, most paths were significant: both road safety attitudes and road user behaviors mediated the association between Disinhibition and traffic injury, and road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions, and road user behaviors sequentially mediated the relation between Disinhibition and traffic injury.

Conclusions:

There were direct effects of Disinhibition sensation seeking, road safety attitudes, and road user behaviors on adolescent traffic injury. Sensation seeking also indirectly affected adolescent traffic injury through multiple mediating roles of road safety attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Implications for traffic injury prevention and training are discussed.

Keywords: Adolescents, sensation seeking, road traffic injury, road user behavior, multiple mediating effect

Introduction

Road traffic injuries (RTIs) to youth are a serious global public health concern (WHO 2006). According to estimates from the Global Burden of Disease project, 29,000 youths aged 10–19 years died in traffic crashes in 2017, and 1,310,000 youths were injured (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2019). The burden of RTIs is particularly pronounced in low- and middle-income countries. In China, the most populous LMIC, 10,369 adolescents of 10–19 years old died due to traffic crashes in 2017. Over 60% of those deaths (N = 6,403) were adolescent pedestrians and cyclists (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2019).

Several factors may explain the vulnerability of adolescents on the road. One contributor is that adolescents may be risky road users: they engage with traffic and roadways in risky ways. Research suggests adolescents – including younger adolescents - frequently engage in traffic without adult supervision, but their cognitive skills to handle complex traffic situations remain inferior to those of adults (O’Neal and Plumert 2018). In particular, adolescents display poor hazard perception ability (Meir et al. 2015) and underdeveloped visual search strategies (Kovesdi and Barton 2013).

A second risk factor for adolescents is their intention to take risk. Adolescents tend to underestimate the cognitive challenge of negotiating traffic safely, and therefore express intentions to take risks on roads that most adults would not take (Tolmie et al. 2006). These intentions may be driven by attitudes that the risks in traffic are less than they actually are. A large literature supports adolescents tendency toward minimalizing risk (Díaz 2002; Evans and Norman 2003; Zhou et al. 2009), and this attitudinal tendency likely occurs in traffic as well as other risky situations (Ulleberg and Rundmo 2003).

A third contributor to adolescent road traffic injury risk is the tendency to engage in sensation seeking behavior. Steinberg and his colleagues (Steinberg et al. 2008) suggest the development of sensation seeking is linked to pubertal maturation, with sensation seeking increasing between ages 10 and 15 and then declining or remaining stable thereafter. Sensation seeking has been linked in several previous studies to risky behaviors on the road as well as to traffic collision incidents (e.g. Dahlen and White 2006; Schwebel et al. 2009). For example, Dahlen and White (2006) examined the roles of sensation seeking, driving anger, and the Big Five personality factors in predicting unsafe driving behavior and crash-related outcomes among university students. They found sensation seeking predicted students’ moving citations, minor crashes, and major crashes. More broadly, sensation seeking is widely cited as a predictor of broad injury risk, including non-traffic-related injuries among samples of children and adults. See Turner et al (2004) for a systematic review.

The pathway through which sensation seeking might lead to risky road behaviors and to traffic injury is less clear. In the teen driving literature, several scholars have proposed that sensation seeking may directly influence risky road behavior (Smorti 2014), but few studies focus on links between sensation seeking and adolescent pedestrian or bicycling behavior. Available evidence supports direct links between sensation seeking and pedestrian behavior among college students, both in simulated pedestrian behavior studies (Schwebel et al. 2009) and in an observational study of violating red light signal crossings (Rosenbloom 2006).

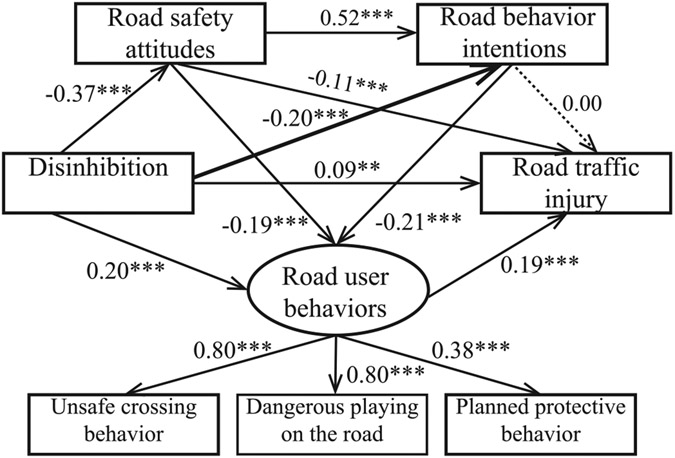

In some domains of risk-taking (e.g. speeding, drunk driving, rule violations), scholars have suggested the relationship between sensation seeking and adolescent-risk-taking is not just a direct relationship, but rather is mediated by other factors, such as individual attitudes (Ulleberg and Rundmo 2003), risk perception (Meir et al. 2015), and anticipated benefits from taking the risk (Machin and Sankey 2008). The present study sought to extend these findings to the domain of adolescent-risk-taking on the road as a pedestrian or cyclist. Figure 1 conceptualizes our hypothesized relationships.

Figure 1.

The proposed multiple mediation model. The association between sensation seeking and traffic injury is mediated by road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions and road user behaviors.

As documented by scattered previous publications, we propose direct relationships between road traffic injury and the following predictors: road user behavior, road behavior intentions, road safety attitudes, and sensation seeking personality. We simultaneously posit that direct effects models linking sensation seeking to injury risk are oversimplified: Risk factors for injury are complex, and there is mounting and compelling evidence suggesting the impact of sensation seeking on injury is influenced by other factors (Ulleberg and Rundmo 2003; Machin and Sankey 2008). We therefore hypothesize, as shown in Figure 1, multiple mediating effects between sensation seeking personality and road traffic injury outcomes. We specifically focus on three potential mediators: road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions, and road user behaviors. We also hypothesize road safety attitudes and road behavior intentions will serve in multiple mediating roles, with high sensation seeking leading to riskier attitudes, which leads to riskier intentions and which in turn leads to riskier behaviors then to injury outcomes.

Method

Participants

Nationwide sampling was used to collect data from 29 primary and secondary schools across 7 Chinese provinces (Anhui, Guangdong; Hunan, Jiangsu, Shandong, Shanghai, Zhejiang).The provinces were selected primarily out of convenience, although we purposively sampled provinces that span different regions in China. In total, 4920 students in grades 5–9 were recruited and the sample yielded 4470 valid questionnaires (effective response rate of 90.9%). Students were sampled from 29 schools, with 4 to 5 schools included from each province. Selection of schools was conducted out of convenience, with purposive sampling to include schools in both urban and rural areas.

The included sample comprised 2134 (47.7%) males and 2336 (52.3%) females, and 1231 fifth-graders (27.5%; Mean age = 10.53 years, SD = 0.64), 1088 sixth-graders (24.3%; Mean age = 11.49 years, SD = 0.71), 732 seventh-graders (16.4%; Mean age = 12.38 years, SD = 0.71), 784 eighth-graders (17.5%; Mean age = 13.39 years, SD = 0.71), and 635 ninth-graders (14.2%; Mean age = 14.35 years, SD = 0.56). The included sample had an age range of 10 to 15 years old and an average age of 12.13 years (SD = 1.50). A small number of older adolescents (ages 16–18; N = 54) were omitted from the analyzed sample to avoid contamination of the analysis from developmental effects, but a sensitivity analysis including the older adolescents yielded results very similar to those reported.

Among the included participants, 1421 adolescents (31.8%) reported that they lived in a city, 1060 (23.7%) in a county town, and 1971 (44.1%) in rural areas (data were missing for 18 participants). 40.7% of the participants (N = 1820) reported mainly walking to and from school, 28.2% (N = 1261) reported mainly riding with parents to and from school by car or motorcycle/electric bicycle, 20.6% (N = 919) reported mainly riding a bicycle to and from school, and 10.2% (N = 458) reporting mainly riding public transportation to and from school (data were missing from 12 participants on transportation to school).

Measures

Sensation seeking

Adolescent sensation seeking level was measured using the Primary and Middle School Students’ Sensation Seeking Scale, which has documented reliability and validity data (Chen et al. 2006). The scale is grounded in Zuckerman’s concept of sensation seeking and includes 30 items, each scored on a 3-point scale (0, 1, 2) with higher scores indicating higher levels of sensation seeking. The scale is divided into two dimensions: Thrill and Adventure Seeking (TAS), which reflects a desire to engage in sports or other activities involving speed or danger, and Disinhibition (Dis), which reflects desire to engage in antisocial negative risk-taking behaviors like social drinking and partying. In our sample, the scale had strong internal consistency (α = 0.92 for TAS, and α = 0.81 for Dis). Confirmatory factor analysis found χ2/df = 8091.02/404, NFI = .95, NNFI = .95, RFI = .95, IFI = .96, CFI = .95, and RMSEA = .07, which together suggest the scale has adequate structural validity in our sample.

Road safety attitudes and road behavior intentions

Adolescent’s road safety attitudes and road behavior intentions were measured by the Children Traffic Safety Awareness Questionnaire (Wang et al. 2013), which has demonstrated reliability and validity in previous research. The questionnaire includes 17 items that are divided into 3 factors: road safety knowledge (e.g. What should you do when walking on the road without sidewalks?), road safety attitudes (e.g. What do you think about when someone wants to climb over the isolation barrier between lanes in a roadway?) and road behavior intentions (e.g. There is a car parked on the side of the road, and your good friends jump up and down in the car and call you to play with them. What would you do?). Items are answered on a 3-point scale (0, 1, 2), with higher scores indicating higher levels of knowledge, safer attitudes toward traffic, and safer road behaviors intentions.

Since risky attitude and behavioral intentions have been demonstrated in previous research to be associated with sensation seeking (Machin and Sankey 2008), but safety knowledge has not, we omitted the safety knowledge scale from further analyses. The other scales were included and had adequate internal consistency reliability coefficients (α = 0.61 for road safety attitudes, α = 0.80 for road behavior intentions). Confirmatory factor analysis found χ2/df = 1118.18/116, NFI = .97, NNFI = .97, RFI = .97, IFI = .97, CFI = .97, and RMSEA = .04, indicating the scale has adequate structural validity in our sample.

Adolescent road user behaviors

We used the Adolescent Road User Behavior Questionnaire (ARBQ) Chinese version to investigate adolescents’ behaviors as a pedestrian and cyclist. This questionnaire was developed by Elliott and Baughan (2004) in the United Kingdom, and revised slightly to reflect Chinese culture and Chinese road traffic environments by Wang and colleagues (Wang et al. 2016). The scale consists of 42 items evaluating self-reported road user behaviors, with items answered on 5-point scales ranging from never to very often. Higher scores indicated riskier road behavior. The ARBQ is divided into 3 factors: unsafe crossing behavior, dangerous playing on the road, and planned protective behavior (reverse scored). The Chinese version of ARBQ has strong psychometric properties to measure adolescent road behavior. In this sample, internal consistency reliability coefficients are strong, with α = 0.81, 0.72, and 0.77 for the three factors of unsafe crossing behavior, dangerous playing on the road, and planned protective behavior, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis found χ2/df = 8004.88/816, NFI = .90, NNFI = .90, RFI = .89, IFI = .91, CFI = .91, and RMSEA = .06, indicating the scale has adequate structural validity in our sample.

Road traffic injury

All participants were asked whether they had been injured on the road as a pedestrian or cyclist in the past 6 months. Three criteria were used to define an injury, with affirmative answers to any of them suggesting a traffic injury had occurred: visiting a professional medical unit to evaluate for an injury; emergency treatment or care from family members, teachers or peers; and missing more than half a day from school because of an injury. Two hundred eighty-four (6.4%) of the participants reported a traffic injury in the past 6 months. Along with completing these scales and questionnaires, all participants reported demographic information (age, grade, gender, living area, and most common means of transportation to and from school).

Procedure

Four thousand four hundred and seventy adolescents from elementary and junior high schools across China were included using cluster sampling. In Jiangsu Province, two research assistants sent questionnaires to primary and secondary students and guided them to fill out questionnaires. In schools outside Jiangsu Province, we entrusted two school teachers in each school and trained them by telephone to issue questionnaires to students and instruct them to complete them. All participating school officials agreed to cooperate with the study and informed consent was obtained from all students. Approval for the research was obtained from the Nantong University Academic Ethics Committee prior to the study. Participants were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality of their answers. They completed the written questionnaires individually in their school setting, and the study took about 20–30 minutes for each participant.

Analysis plan

Data analysis proceeded in three steps. First, one-way MANCOVAs were conducted on all variables to explore potential gender and age effects, and Spearman correlations were computed to examine the interrelations among variables. Second, we tested the direct effects of adolescent sensation seeking, road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions, and road user behaviors on traffic injury using logistic regression analysis. Variables were included in the multivariate logistic regression model based on bivariate Spearman correlation results, with those variables having significant bivariate relations with the outcome measure included in the multivariate analysis. Finally, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted to evaluate the multiple mediation model of road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions and road user behaviors as mediators of the association between sensation seeking and adolescent traffic injury, as illustrated in Figure 1. Analyses were conducted using SPSS 22, Lisrel 8.8 and MPLUS7.0.

Results

Tests of common method bias (CMB)

Since our data were all collected from adolescents’ self-report, it faced risk of CMB, which would threaten the validity of the conclusions about the relations between measures (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Therefore, two tests were conducted to test the extent of CMB. First, we computed a Harman’s single-factor test. The results of a principal components factor analysis of all items from the theoretical constructs constrained to a single-factor produced a variance of 33% on the first factor, which was well below the acceptable maximum threshold of 50% of total variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

Given the insensitivity of the Harman’s test (Podsakoff et al. 2003), we also performed a Single Method-Factor Approach test. First, we constructed a confirmatory factor analysis model, which achieved main fitting indexes of χ2/df = 3.676, NFI = 968, GFI = 989, CFI = 977, TLI = 968, and RMSEA = 0.027. Second, on the basis of the original confirmatory factor analysis model, a method latent factor was added to make all measurement items load on this factor besides the concept factor. The results showed that, compared with the original model, Δ χ2/df = 0.019, Δ NFI = 0.001, Δ GFI = 0.001, Δ CFI = 0.002, Δ TLI = 0.003, and Δ RMSEA = 0.001. All changes in fitting indices were less than 0.02, so it can be concluded that the model was not significantly improved by adding common method factors. Together, the results indicate no obvious common method deviation in measurement.

Associations among variables

Means and standard deviations for all study variables are presented in Table 1, both for the full sample and for the sample divided by gender and by age group. To examine age and gender effects, we computed two MANCOVA models. In the first model, participant age served as a covariate and gender was entered as the independent variable. In the second model, gender served as a covariate and age was entered as the independent variable. For both models, five dependent variables were included: TAS sensation seeking, Dis sensation seeking, road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions, and road user behaviors.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations for boys and girls, and age groups.

| TAS sensation seeking | Dis sensation seeking | Road safety attitudes | Road behavior intentions | Road user behaviors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

| Full sample | 39.82 | 11.40 | 46.72 | 8.23 | 1.89 | 0.24 | 1.83 | 0.28 | 1.96 | 0.38 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Boys | 39.92 | 11.75 | 47.05 | 8.97 | 1.86 | 0.27 | 1.80 | 0.35 | 1.99 | 0.4 |

| Girls | 39.79 | 11.08 | 46.43 | 7.48 | 1.92 | 0.20 | 1.88 | 0.28 | 1.94 | 0.36 |

| F (1, 4467) | 0.89 | 7.36 ** | 76.00 *** | 80.88 *** | 30.56 *** | |||||

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 10 | 37.74 | 10.57 | 46.24 | 6.53 | 1.93 | 0.19 | 1.90 | 0.25 | 1.83 | 0.32 |

| 11–12 | 39.23 | 11.09 | 46.87 | 8.40 | 1.90 | 0.22 | 1.86 | 0.30 | 1.90 | 0.38 |

| 13–14 | 41.10 | 11.78 | 46.48 | 8.35 | 1.86 | 0.27 | 1.80 | 0.35 | 2.07 | 0.37 |

| 15 | 43.27 | 12.05 | 48.08 | 10.00 | 1.84 | 0.27 | 1.78 | 0.31 | 2.15 | 0.33 |

| F(3, 4464) | 24.69 *** | 3.87 ** | 20.23 *** | 24.05 *** | 119.17 *** | |||||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

In the first model, with age controlled, significant univariate gender effects were obtained on the Dis sensation seeking, road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions and road user behaviors outcomes, Fs (1, 4467) = 7.36, 76.00, 80.88, 30.56, respectively, all ps < 0.05 ( = 0.01, 0.02, 0.02, and 0.01, respectively). Boys scored lower than girls on road safety attitudes and road behavior intentions, but higher than girls on Dis sensation seeking and road user behaviors. Moreover, Chi-square tests showed that more boys suffered traffic injuries than girls, χ2(1, N = 4470) = 39.49, p < 0.001.

In the second MANCOVA model, with gender controlled, significant univariate age effects were obtained on TAS and Dis sensation seeking, and on measures of road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions and road user behaviors, Fs(3, 4464) = 24.69, 3.87, 20.23, 24.05, 119.17, respectively, all ps < 0.001 (η2p = 0.02, 0.02, 0.02, 0.02 and 0.08, respectively). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses indicated adolescents 10 years old showed the lowest sensation seeking levels and the safest road behavior intentions among the age groups, while 15-year-olds showed the highest sensation seeking levels, the most risky road behaviors, and the lowest scores in road safety attitudes and road behavior intentions among the age groups (p < 0.05). Chi-square tests showed no significant differences in traffic injury across age groups, χ2(4, N = 4470) = 1.10, p > 0.05.

Spearman correlations were computed to explore the interrelations among variables (Table 2). The correlation coefficients between traffic injury and other variables range from 0.01 to 0.15, with moderate relations emerging between adolescent traffic injury and most other variables except TAS and age. The predictor variables generally intercorrelated moderately.

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlations between study variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Traffic injurya | — | ||||||

| 2 Thrill and Adventure Seeking (TAS) | .01 | — | |||||

| 3 Disinhibition (Dis) | .10*** | .43*** | — | ||||

| 4 Road safety attitudes | −.15*** | −.15*** | −.26*** | — | |||

| 5 Road behavior intentions | −.123*** | −.16*** | −.30*** | .53*** | — | ||

| 6 Road user behaviors | .14*** | .14*** | .21*** | −.36*** | −.38*** | — | |

| 7 Male/Femaleb | −.10*** | .01 | .01 | .12*** | .13*** | −.06*** | — |

| 8 Age | −.01 | .12*** | −.09*** | −.13** | −.12*** | .28*** | .01 |

Traffic injury (0 = no traffic injury, 1= suffered traffic injury).

Male/Female (1 = male, 2 = female).

Note. Spearman’s rho was used due to the categorical variables of traffic injury and gender.

p < .01

p < .001.

Logistic regression analysis

Based on the correlation results, logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the effect of Disinhibition, road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions, road user behaviors, gender and age on the dichotomous outcome of adolescent traffic injury history. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was χ2(8, N = 4470) = 11.38, p > 0.05, suggesting adequate goodness of fit. Table 3 shows results, which indicate all variables predict adolescent traffic injury significantly except road behavior intentions.

Table 3.

Coefficients for the logistic regression analysis of adolescent traffic injury.

| Variable | B | Wald (df = 1) | p | OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disinhibition | .03 | 15.49 | <.001 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) |

| Road safety attitudes | −1.03 | 17.14 | <.001 | .35 (.21–.58) |

| Road behavior intentions | .22 | 1.1 | .32 | 1.25 (.81–1.94) |

| Road user behaviors | 1.10 | 36.05 | <.001 | 2.99 (2.09–4.27) |

| Male gender | .66 | 23.68 | <.001 | 1.93 (1.48–2.52) |

| Age | −.23 | 7.66 | <.01 | .80 (.68-.96) |

Multiple mediation model

The correlation and regression results indicate road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions, and road user behaviors all may serve as mediators of the relation between Disinhibition and adolescent traffic injury risk. Therefore, a multi-mediation model was tested using SEM. We controlled for gender and age in the model. Fit statistics indicated the model was a good fit to the data, χ2 =408.44, df = 20, CFI = .96, TLI = .92, and RMSEA (90% CI) = .0066 (0.061–0.072). The standardized regression coefficients for all paths are shown in Figure 2. Most paths were significant, except the path from road behavior intentions to traffic injury. The results indicate that Disinhibition not only positively predicted traffic injuries directly, but also predicted traffic injuries indirectly through road safety attitudes, and through road user behaviors. Disinhibition also predicted traffic injuries through sequential mediators of road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions, and road user behaviors.

Figure 2.

Predicting adolescent traffic injury from Disinhibition, road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions, and road user behaviors. Path values are the path coefficients. (n = 4470, gender and age are controlled in the model).

**p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

This study had two primary aims. First, we sought to replicate previously-reported direct effects of sensation seeking, road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions and road user behaviors on adolescent traffic injury. As predicted, most variables correlated strongly to adolescent traffic injury. Second, we evaluated a multiple mediating model to test whether road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions and road user behaviors mediated the relation between sensation seeking and adolescent traffic injury. Our results confirmed the hypothesis that the Disinhibition component of sensation seeking indirectly influenced adolescent road injury incidents, with road safety attitudes, road behavior intentions and road user behaviors directly and/or sequentially mediating the effect.

The fact that the Disinhibition subscale of sensation seeking was associated with traffic injury risk as well as adolescent road user behaviors and road safety attitudes is consistent with previous studies among adult pedestrians (Rosenbloom 2006; Schwebel et al, 2009), and teen drivers (Smorti 2014). Of particular note, our findings support previous studies linking sensation seeking with actual traffic crashes among drivers (e.g. Iversen and Rundmo 2002).

Our results also replicate previous reports concerning road safety attitudes and road behaviors on adolescent traffic injury: adolescents who reported less safe attitudes about risk in traffic, and who report engaging in riskier road behaviors, were more likely to experience traffic injuries (Tolmie et al. 2006). This finding reinforces the potential for adolescent traffic safety interventions that focus on attitudinal change through theory-driven health behavior change strategies.

Along with the direct paths between Disinhibition sensation seeking and traffic injury risk, our hypothesized mediational model proved largely accurate. The relation between Disinhibition and road traffic injuries was mediated by both road traffic attitudes and road user behaviors. We also found sequential mediation, with Disinhibition sequentially leading to risky road safety attitudes and then to risky road behaviors, which led to injury as well as Disinhibition leading to risky road behavior intentions, which sequentially led to risky road behaviors and then injury. These results support the Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior (Ajzen 2005), which states the proximal determinant of behavior is the individual’s intention to perform the behavior, and intention is in turn determined by three constructs: attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control.

One surprising finding was that road behavior intentions did not have a direct effect on adolescent traffic injury in the logistic regression analysis, although the bivariate Spearman correlation analysis found a significant negative correlation between the two. This pattern of results suggests adolescents’ road behavior intentions may not affect the occurrence of traffic injuries directly, but rather only indirectly through their actual road behaviors. It corresponds to results by Díaz (2002), who found adult pedestrians’ intentions to violate traffic regulations were related to their reported violations, errors and lapses.

Also surprising was the result that although the Disinhibition (Dis) subscale of sensation seeking was related to adolescent traffic injury both directly and indirectly, the Thrill and Adventure Seeking (TAS) subscale of sensation seeking was not. This finding concords with previous research on risky teen driving (Dahlen and White 2006), and may reflect a critical distinction between aspects of sensation seeking that are relevant to traffic safety risks. Zuckerman (1971) defines TAS among adults as “a desire to engage in outdoor sports or other activities involving elements of speed or danger,” while Dis is described as “the loss of social inhibitions: heavy social drinking, variety in sexual partners, ‘wild’ parties, and gambling.” Chen et al (2006) extends the definition for Chinese culture, implying that TAS encompasses activities that offer speed and opportunity to challenge authority, but those activities are accepted and even advocated by society. In other words, TAS may reflect pro-social or positive risk-taking tendencies. Dis, on the other hand, reflects preferences for new and exciting experiences, some of which may be anticonventional or illegal. Thus, Dis could be conceptualized as antisocial, negative risk-taking. Many traffic safety risks involve breaking laws, behaving in antisocial or negative ways, and contradicting pro-social activities such as waiting patiently for other road users to pass before proceeding. Thus, the links between Dis and traffic safety, but not between TAS and traffic safety, seem logical and indicate the need for researchers and interventionists to consider sensation seeking as a multi-factored construct when conceptualizing risk and developing behavioral interventions.

From a prevention perspective, one must also remember that sensation seeking is an aspect of personality, and therefore likely to be fairly stable and resistant to change. The fact that we found the relation between sensation seeking and traffic safety risk was mediated by other variables, however, offers promise for behavioral intervention efforts. Unlike sensation seeking personality, some mediating factors we identified – in particular, road safety attitudes and intentions – may be amenable to change through theory-driven intervention strategies. Prevention and training programs that target traffic safety attitudes and intentions at an early age may be effective to reduce subsequent risk-taking in traffic by adolescents. Such interventions might use strategies to increase children’s perceived vulnerability to risk (change individual attitudes, e.g. Tolmie et al. 2006), to alter group-based norms of how to engage in traffic (change behavioral intentions, e.g. Zhou et al. 2009), and to help adolescents recognize the real risk of injury and death from errors in roadways (change individual attitudes and behavioral intentions, e.g. Evans and Norman 2003).

Our study suffers from weaknesses. First, we collected data only through self-report measures, which may create bias in our measurement and influence the precision of our findings. Future research might employ multi-informant and behavioral methods to collect more comprehensive information. Second, we adopted a cross-sectional design, in which road user behaviors and road traffic injury history were retrospectively reported but safety attitudes and safety behavior intentions were reported for the present. Causal conclusions regarding the cross-sectional findings must be interpreted cautiously and future research might implement prospective and longitudinal designs. Last, our study was amply powered, so many of the effects we report, though statistically significant, had small to moderate effect sizes. This is a common conclusion in research studying personality influences on behavior, as well as in research studying the effect of health behavior attitudes on actual health behaviors (Gignac and Szodorai 2016). We suggest the data patterns we report are likely to be veridical and meaningful, but moderate rather than strong in scope and their influence on behavior and injury outcomes.

In summary, our study found direct effects of Disinhibition sensation seeking, road safety attitudes and road user behaviors on adolescent traffic injury; adolescents with high sensation seeking levels, less safe attitudes, and riskier behaviors were more likely suffer traffic injuries. We also found that sensation seeking indirectly affected adolescent traffic injury through multiple mediating roles of traffic safety attitudes, road behavior intentions and road user behaviors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the students from 29 primary and secondary schools for their participation, and the teachers from these schools for their assistance with the survey. We also thank Zhang Jing and Wu Peng for assistance with collecting data. Finally, we acknowledge Wu Mengying and Cheng Xuebing for assistance with coding and preliminary data analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences [grant number 16YJC880072]. This research was also supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the United States National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD088415. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ajzen I. 2005. Attitudes, personality and behaviour. Berkshre, England: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Zhang M, Jin Z, Zhao S, Mei S. 2006. The development and application of primary and middle school students’ sensation seeking scale. Psychol Develop Educ. 4:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlen ER, White RP. 2006. The Big Five factors, sensation seeking, and driving anger in the prediction of unsafe driving. Personal Indiv Diff. 41(5):903–915. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz EM. 2002. Theory of planned behavior and pedestrians’ intentions to violate traffic regulations. Transport Res Part F. 5:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MA, Baughan CJ. 2004. Developing a self-report method for investigating adolescent road user behaviour. Transport Res Part F. 7(6):373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Evans D, Norman P. 2003. Predicting adolescent pedestrians’ road-crossing intentions: an application and extension of the theory of planned behaviour. Health Educ Res. 18(3):267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gignac GE, Szodorai ET. 2016. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personal Indiv Differ. 102:74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2019. GBD compare viz hub. University of Washington. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ [last accessed May 28, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen H, Rundmo T. 2002. Personality, risky driving and accident involvement among Norwegian drivers. Personal Indiv Differ. 33(8):1251–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Kovesdi CR, Barton BK. 2013. The role of non-verbal working memory in pedestrian visual search. Transport Res Part F. 19:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Machin MA, Sankey KS. 2008. Relationships between young drivers’ personality characteristics, risk perceptions, and driving behaviour. Accident Anal Prevent. 40(2):541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meir A, Oron-Gilad T, Parmet Y. 2015. Are child-pedestrians able to identify hazardous traffic situations? Measuring their abilities in a virtual reality environment. Safe Sci. 80:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neal EE, Plumert JM. 2018. How do parents teach children to cross roads safely? A study of parent-child road-crossing in an immersive pedestrian simulator. Inj Prevent. 24:A17–A18. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 88(5):879–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom T. 2006. Sensation seeking and pedestrian crossing compliance. Soc Behav Pers. 34(2):113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Schwebel DC, Stavrinos D, Kongable EM. 2009. Attentional control, high intensity pleasure, and risky pedestrian behavior in college students. Accident Anal Prevent. 41(3):658–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smorti M. 2014. Sensation seeking and self-efficacy effect on adolescents risky driving and substance abuse. Proc Social Behav Sci. 140:638–642. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Albert D, Cauffman E, Banich M, Graham S, Woolard J. 2008. Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: evidence for a dual systems model. Dev Psychol. 44(6):1764–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolmie AK, Thomson JA, O’Connor R, Foot HC, Karagiannidou E, Banks M, O’Donnell C, Sarvary P. 2006. The role of skills, attitudes and perceived behavioural control in the pedestrian decision-making of adolescents aged 11–15 years. London: Department for Transport. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5ac0/bc41770c7ca6e-ceb0b5b1dadeae8f25c14ba.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Turner C, McClure R, Pirozzo S. 2004. Injury and risk-taking behavior: a systematic review. Accident Anal Prevent. 36(1):93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulleberg P, Rundmo T. 2003. Personality, attitudes and risk perception as predictors of risky driving behaviour among young drivers. Safe Sci. 41(5):427–443. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Shi L, Tan D. 2013. Preparation and application of Children Traffic Safety Awareness Questionnaire. China Safe Sci J. 23(8):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang HR, Wu M, Chen X. 2016. Revision of the adolescent road user behaviour questionnaire for Chinese adolescent. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 24(2):245–249. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2006. Child and adolescent injury prevention: a WHO plan of action 2006-2015. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Horrey W, Yu R. 2009. The effect of conformity tendency on pedestrians’ road-crossing intentions in China: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Accident Anal Prevent. 41(3):491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M 1971. Dimensions of sensation seeking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 36(1):45–52. [Google Scholar]