This case series study evaluates the prevalence of germline variants that were incidentally detected via tumor-only genomic profiling among patients with mesothelioma.

Key Points

Question

What proportion of mesothelioma tumor profiling assays incidentally detect germline variants associated with hereditary cancer syndromes?

Findings

In a case series of 161 unrelated patients with mesothelioma, 16% carried a pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variant associated with hereditary cancer syndromes.

Meaning

These findings suggest that mesothelioma patients may benefit from universal germline testing.

Abstract

Importance

Patients with mesothelioma often have next-generation sequencing (NGS) of their tumor performed; tumor-only NGS may incidentally identify germline pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants despite not being designed for this purpose. It is unknown how frequently patients with mesothelioma have germline P/LP variants incidentally detected via tumor-only NGS.

Objective

To determine the prevalence of incidental germline P/LP variants detected via tumor-only NGS of mesothelioma.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A series of 161 unrelated patients with mesothelioma from a high-volume mesothelioma program had tumor-only and germline NGS performed during April 2016 to October 2021. Follow-up ranged from 18 months to 7 years. Tumor and germline assays were compared to determine which P/LP variants identified via tumor-only NGS were of germline origin. Data were analyzed from January to March 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The proportion of patients with mesothelioma who had P/LP germline variants incidentally detected via tumor-only NGS.

Results

Of 161 patients with mesothelioma, 105 were male (65%), the mean (SD) age was 64.7 (11.2) years, and 156 patients (97%) self-identified as non-Hispanic White. Most (126 patients [78%]) had at least 1 potentially incidental P/LP germline variant. The positive predictive value of a potentially incidental germline P/LP variant on tumor-only NGS was 20%. Overall, 26 patients (16%) carried a P/LP germline variant. Germline P/LP variants were identified in ATM, ATR, BAP1, CHEK2, DDX41, FANCM, HAX1, MRE11A, MSH6, MUTYH, NF1, SAMD9L, and TMEM127.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this case series of 161 patients with mesothelioma, 16% had confirmed germline P/LP variants. Given the implications of a hereditary cancer syndrome diagnosis for preventive care and familial counseling, clinical approaches for addressing incidental P/LP germline variants in tumor-only NGS are needed. Tumor-only sequencing should not replace dedicated germline testing. Universal germline testing is likely needed for patients with mesothelioma.

Introduction

Mesothelioma is an aggressive cancer that principally affects the pleural and/or peritoneal cavities.1 The prognosis of mesothelioma is poor, with a median survival of only 18.4 months.2 Anatomic tumor location does influence prognosis, as individuals with peritoneal mesothelioma have longer survival compared with patients with pleural mesothelioma.3

Asbestos exposure is the major known risk factor for mesothelioma, but prior work has shown 12% of patients also carry germline pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants that further modify an individual’s lifetime risk of solid tumor development.3,4,5,6,7 Individuals with peritoneal mesothelioma are particularly likely to carry germline P/LP variants (25% of cases).4 Universal germline genetic testing, which is increasingly a standard of care in other cancers, is not yet routinely used in mesothelioma care.8 Clinical guidelines for mesothelioma recommend discussing the risks and benefits of germline genetic testing with patients who have personal or family histories that are suggestive of a hereditary cancer syndrome, particularly if these malignant neoplasms are associated with germline BAP1 P/LP variants.9 Experiences with other tumor types have shown that universal genetic testing, as opposed to germline testing triggered by high-risk personal and/or family histories, increases the diagnosis of hereditary cancer syndromes.10

Germline BAP1 P/LP variants are the most frequent and well-studied alterations in patients with mesothelioma who have increased cancer risk. Patients with mesothelioma and germline P/LP variants, especially in BAP1, have improved survival relative to patients without germline P/LP variants.3,11 Recognition of patients with germline BAP1 P/LP variants may also help guide treatment decision-making, particularly in regard to the use of platinum-based therapies.3,4,9

Tumor-only next-generation sequencing (NGS) is increasingly being used in academic practices, where NGS can determine eligibility for clinical trials investigating targeted agents. The genes that are most frequently somatically altered in mesothelioma include BAP1, CDKN2A, DDX3X, NF2, and TP53.12,13 These same genes, when altered in the germline, are associated with hereditary cancer syndromes (BAP1, CDKN2A, NF2, and TP53) as well as developmental delays and/or disabilities (DDX3X).9,14,15,16,17,18 Recognizing the germline origin of these variants has important implications for the counseling and care of both the patient and their family members.9 Some P/LP variants detected via tumor-only NGS may be of germline origin. The association between tumor-only NGS and germline sequencing has not previously been performed for patients with mesothelioma.

Here, we analyzed a large series of patients with mesothelioma who underwent both tumor and germline sequencing. We determined the prevalence of incidental germline findings that were also detected via tumor-only sequencing.

Methods

Study Population

Patients with mesothelioma presenting to University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) were consented to an annually reviewed, institutional review board–approved protocol, from April 2016 to October 2021. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. After thorough discussion of the protocol, including risks and benefits, confidentiality, and voluntary nature of participation, and allowing the patient adequate time for consideration and asking questions, informed consent was obtained. This protocol allowed for biobanking (peripheral blood, saliva, and tumor) and germline sequencing. Trained interviewers used a standardized survey to collect a personal and family history of cancer from each patient. Primary (occupational or environmental) or secondary asbestos exposure (living with persons exposed to asbestos) was self-reported by patients. All exposures were classified as definite, probable, possible, or no known exposure. Demographic data, such as participant-reported race, were also collected, as patients with European ancestry have historically been overrepresented in most mesothelioma studies, increasing the importance of including data from non-European populations.

Germline Variant Detection and Interpretation

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells or saliva. DNA was sequenced with an 84 gene, research-based, NGS panel designed by the University of Chicago Genetic Services Laboratory to sequence the coding and flanking intronic regions of each gene (genes listed in eTable 1 in Supplement 1). All variants were analyzed by 2 independent reviewers (S.D. and D.G.) and interpreted according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and Association for Molecular Pathology consensus guidelines.19 P/LP variants, including nonsense, frameshift, splice site, missense variants, and large-scale genomic rearrangements with known moderate-to-high penetrance cancer susceptibility were reported. All germline P/LP variants were validated by Sanger sequencing, correlated with clinical and family history, and segregated in family members when possible. During the informed consent process, patients could opt in to receive disclosure of clinically relevant research results. Patients selecting yes were provided with clinical appointments with a physician and/or genetic counselor to discuss these results.

Somatic Variant Detection and Interpretation

DNA was extracted from fresh frozen, paraffin embedded tumor tissue blocks. Somatic variants were identified using the UCM OncoPlus NGS panel, which sequences 1212 genes with median depths ranging from 360 × to 785 × coverage. eTable 1 in Supplement 1 contains 76 genes from the Oncoplus panel that are clinically reported.20

Immunohistochemistry

BAP1 and PD-L1 staining was conducted in a CLIA-certified laboratory. The Santacruz, C4 monoclonal antibody was used for BAP1 staining and the Abcam 28.8 monoclonal antibody was used to evaluate PD-L1 staining. Percentage of cells positive for PD-L1 was calculated via the Tumor Percentage Score (TPS).

Statistical Analysis

Fisher exact test and χ2 test were used to determine an association between patients with mesothelioma, the presence of germline variants, patient demographics, and tumor characteristics. A 2-sided P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was generated in Microsoft Excel, version 16, with the Real Statistics Resource Pack software, version 7.6, (Real Statistics) from August 2022 to March 2023.

Results

Study Population

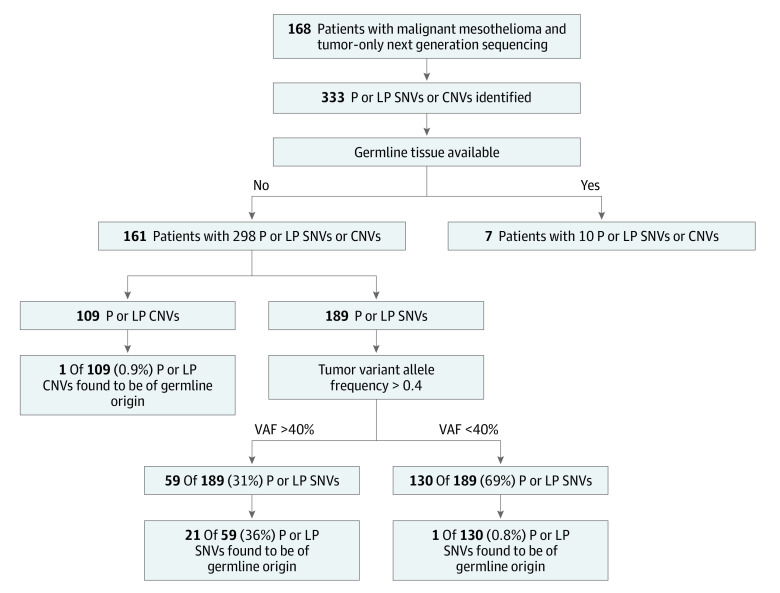

Overall, 168 unrelated patients with mesothelioma who had tumor-only NGS were included. Of these patients, 161 (96%) had sufficient germline tissue available for sequencing (Figure 1). Of the 161 patients, 105 were male (65%) and the mean (SD) age was 64.7 (11.2) years. Most patients self-identified as non-Hispanic White (156 patients [97%]). Approximately 68% of all patients had pleural mesothelioma (109 patients), 28% had peritoneal mesothelioma (45 patients), and 4% had bicavitary disease or involvement of the tunica vaginalis (7 patients). Most patients had epithelioid mesothelioma (138 patients [86%]), 14 patients (9%) had biphasic, and 8 patients (5%) had sarcomatoid mesothelioma. Most patients did not have a personal history of second cancers (122 patients [76%]). Among the 39 patients (24%) with second malignant neoplasms, 12 had a history of skin cancer not otherwise specified secondary to a lack of family knowledge and/or medical records, 8 had prostate cancer, 7 had lymphoma, and 4 had thyroid cancer. A total of 114 patients (71%) had a first-degree family member with a malignant neoplasm (Table 1).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Patients in Mesothelioma Sequencing Cohort.

CNV indicates copy number variants; P, pathogenic; LP, likely pathogenic; SNV, single nucleotide variants.

Table 1. Characteristics of Mesothelioma Patients and Tumors.

| Characteristic | Patients, No (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with P or LP germline variants | Patients without P or LP germline variants | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 9 (36) | 47 (35) | >.99 |

| Male | 16 (64) | 89 (65) | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||

| <20 | 0 | 0 | .92 |

| 20-29 | 0 | 2 (1) | |

| 30-39 | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| 40-49 | 1 (4) | 7 (5) | |

| 50-59 | 6 (24) | 31 (22) | |

| 60-69 | 9 (36) | 51 (38) | |

| 70-79 | 6 (24) | 36 (26) | |

| >80 | 3 (12) | 8 (6) | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Asian or South Asian | 0 | 3 (2) | >.99 |

| Black | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| White, Hispanic | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 25 (100) | 131 (96) | |

| Asbestos exposurea | |||

| Definite | 10 (40) | 52 (38) | .77 |

| Probable | 4 (16) | 32 (24) | |

| Possible | 8 (32) | 41 (30) | |

| No known exposure | 3 (12) | 10 (7) | |

| No data | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Mesothelioma site | |||

| Bicavitary | 1 (4) | 4 (3) | .61 |

| Pericardium | 0 | 0 | |

| Peritoneum | 9 (36) | 36 (26) | |

| Pleura | 15 (60) | 94 (69) | |

| Tunica vaginalis | 0 | 2 (1) | |

| Tumor histology | |||

| Benign multicystic | 0 | 1 (1) | .69 |

| Biphasic | 2 (8) | 12 (9) | |

| Epithelial | 23 (92) | 115 (85) | |

| Sarcomatoid | 0 | 8 (6) | |

| Personal history of other cancer | |||

| Yes | 12 (48) | 27 (18) | .005 |

| No | 13 (52) | 109 (81) | |

| Other cancersb | |||

| Colon | 0 | 2 (6) | NA |

| Lymphoma | 3 (19) | 4 (13) | |

| Prostate | 2 (13) | 6 (19) | |

| Kidney | 2 (13) | 0 | |

| Skin, not otherwise specified | 3 (19) | 9 (29) | |

| Thyroid | 1 (6) | 3 (10) | |

| Other | 5 (31) | 7 (23) | |

| Cancer in first degree relative | |||

| Yes | 23 (92) | 91 (68) | .01 |

| No | 2 (8) | 45 (33) | |

Abbreviations: LP, likely pathogenic; P, pathogenic.

Self-reported.

Some patients had multiple other cancers.

Somatic and Germline P/LP Variants

Overall, 25 of 161 patients (16%) ultimately carried a P/LP germline variant (Figure 1 and eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Most patients (126 patients [78%]) with tumor-only NGS had a P/LP variant detected in a gene associated with a hereditary cancer syndrome. The positive predictive value (PPV) of a P/LP variant identified on tumor-NGS was 20% (25 of 126 patients). A total of 28 germline P/LP variants were identified. Three patients carried P/LP germline variants in 2 different genes. Most germline variants were in genes involved in DNA repair: BAP1 (8 patients [29% of patients with a germline P/LP variant]), CHEK2 (6 patients [21%]) and ATM (3 patients [11%]). Other genes with a germline P/LP variant identified in at least 1 patient included ATR, DDX41, FANCM, HAX1, MRE11A, MSH6, MUTYH, NF1, SAMD9L, and TMEM127 (Table 2). Each patient with multiple P/LP germline variants carried a P/LP BAP1 variant with germline P/LP variants in additional genes: TMEM127 (patient 8), HAX1 (patient 9), and SAMD9L (patient 10).

Table 2. Patients With a Germline Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic Variant.

| Patient | Gene | Variant on germline panel | Variant on tumor panel | Tumor VAF, % | Interpretationa | Inheritance | IHC BAP1 status | History of other cancers | First-degree family history of cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ATM | p. ? | p.? | 50 | P | D | RE | Breast | Uterine |

| 2 | ATM | p.E1978* | p.E1978* | 44 | P | D | L | Thyroid | Prostate |

| 3 | ATM | p.E2052K | p.E2052K | 48 | LP | D | L | DLBCL | Colorectal |

| 4 | ATR | p.R443* | p.R443* | 54 | LP | D | L | No | Lymphoma NOS |

| 5 | BAP1 | p.L573Wfs*3 | p.L573Wfs*3 | 78 | P | D | L | No | Mesothelioma |

| 6 | BAP1 | p.L573Wfs*3 | p.L573Wfs*3 | 43 | P | D | L | Meningioma, BCC | BCC, breast, gilioblastoma, mesothelioma, testicular |

| 7 | BAP1 | p.L573Wfs*3 | p.L573Wfs*3 | 51 | P | D | L | No | RCC, uterine |

| 8 | BAP1 | p.Q260* | p.Q260* | 52 | P | D | L | Skin NOS | BCC, mesothelioma |

| 9 | BAP1 | c.376_377del,p.? | c.376_377delp.? | NA | P | D | ND | Bladder, melanoma | Bladder, ovarian |

| 10 | BAP1 | p.C91Wfs*35 | p.C91Wfs*35 | 88 | LP | D | L | No | Sarcoma |

| 11 | BAP1 | Structural rerrangement2 | Rearrangements | NA | P | D | L | No | Kidney |

| 12 | BAP1 | p.R60* | p.R60* | 46 | P | D | L | RCC | Breast |

| 13b | CD36 | p.S113Ffs*20 | NA | NA | P | R | R | No | Colorectal, prostate |

| 14 | CHEK2 | p.I157T | p.I157T | 70 | LP | D | L | No | Breast, kidney NOS |

| 15 | CHEK2 | p.W93Gfs*17 | p.W93Gfs*17 | 49 | P | D | L | Prostate | Colorectal |

| 16 | CHEK2 | p.T476M | p.T476M | 89 | LP | D | L | No | None |

| 17 | CHEK2 | p.T367Mfs*15 | p.T367Mfs*15 | 42 | P | D | L | Prostate, WM | Breast, prostate, thyroid |

| 18 | CHEK2 | p.T367Mfs*15 | p.T367Mfs*15 | 45 | P | D | RE | Breast | Breast |

| 19 | CHEK2 | p.I157T | p.I157T | 49 | LP | D | L | No | NHL, prostate |

| 20 | DDX41 | p.R164W | p.R164W | 46 | LP | D | L | No | Lymphoma NOS |

| 21b | FANCM | p.Q1701* | NA | NA | LP | R | RE | Paragan-glioma | Bladder |

| 9b | HAX1 | p.E31Kfs*54 | NA | NA | P | R | ND | Bladder, melanoma | Bladder, ovarian |

| 22 | MRE11A | p.T408Nfs*49 | p.T408Nfs*49 | 46 | LP | R | ND | No | Colorectal |

| 23 | MSH6 | p.F1088Lfs*5 | p.F1088Lfs*5 | 16 | P | R | R | No | Colorectal, skin NOS |

| 24b | MUTYH | p.Y179C | NA | NA | P | R | L | CLL, BCC | None |

| 25 | NF1 | p.P1650Lfs*48 | p.P1650Lfs*48 | 47 | P | D | R | RCC | None |

| 10b | SAMD9L | p.Q1409Tfs*49 | NA | NA | LP | R | L | No | Sarcoma |

| 8b | TMEM127 | p.L155* | N/A | NA | P | R | L | Skin NOS | BCC, mesothelioma |

Abbreviations: BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; D, dominant; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; L, lost; LP, likely pathogenic; ND, no data; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; NOS, not otherwise specified; P, pathogenic; R, recessive; RE, retained; VAF, variant allele frequency; WM, Waldenstrom macroglobulinmia.

Interpretation by The University of Chicago Genetic Services Lab.

Gene not sequenced on tumor NGS panel; all other genes names, variant detected in both germline and tumor tissue.

Characteristics of Germline P/LP Variant Carriers

Most patients (15 patients [60%]) with P/LP germline variants had pleural mesothelioma, 36% (9 patients) had peritoneal mesothelioma, and 4% (1 patient) had bicavitary disease. Asbestos exposure was not significantly different between germline P/LP variant carriers and patients without germline variants (P = .77, Fisher exact test) (Table 1). Germline variant carriers were more likely to have a history of a second cancer (12 of 25 patients [48%]; P = .005; odds ratio [OR], 3.73; 95% CI, 3.19-4.24) as compared with patients without germline variants (27 of 136 patients [18%]). Most patients (11 of 12 patients [92%]) with P/LP germline variants and multiple cancers received a mesothelioma diagnosis concurrently or after the diagnosis of the other malignant neoplasm (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The mean (SD) time between a first diagnosis of cancer and a mesothelioma diagnosis in patients with P/LP germline variants was 9.8 (14.5) years (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Germline P/LP variant carriers were more likely to have at least 1 first-degree family member with a cancer diagnosis (23 patients [92%]; P = .01, Fisher exact test) than patients without a germline P/LP variant (91 patients [68%]) (Table 1).

Pathologic Characteristics of Mesothelioma in Germline P/LP Variant Carriers

Overall, 23 of 25 germline P/LP variant carriers (92%) had epithelioid mesothelioma and 2 germline P/LP variant carriers had biphasic mesothelioma (8%). These proportions were similar to patients without germline variants (85% epithelioid and 9% biphasic or sarcomatoid; respectively, P = .69; OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.80-1.09) (Table 1). Most tumors in germline P/LP variant carriers (17 patients [68%]) lost BAP1 expression, which was similar to patients without germline P/LP variants (69 patients [51%]) (P = .28, Fisher exact test). Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) staining, which may be associated with immunotherapy response in mesothelioma, was similarly positive in patients with and without germline P/LP variants (56% and 45%, respectively; P = .38, Fisher exact test).21,22 Most patients with evaluable CHEK2 germline P/LP variant carriers (5 of 6 patients [83%]) had tumors with BAP1 loss and positive PD-L1 staining (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

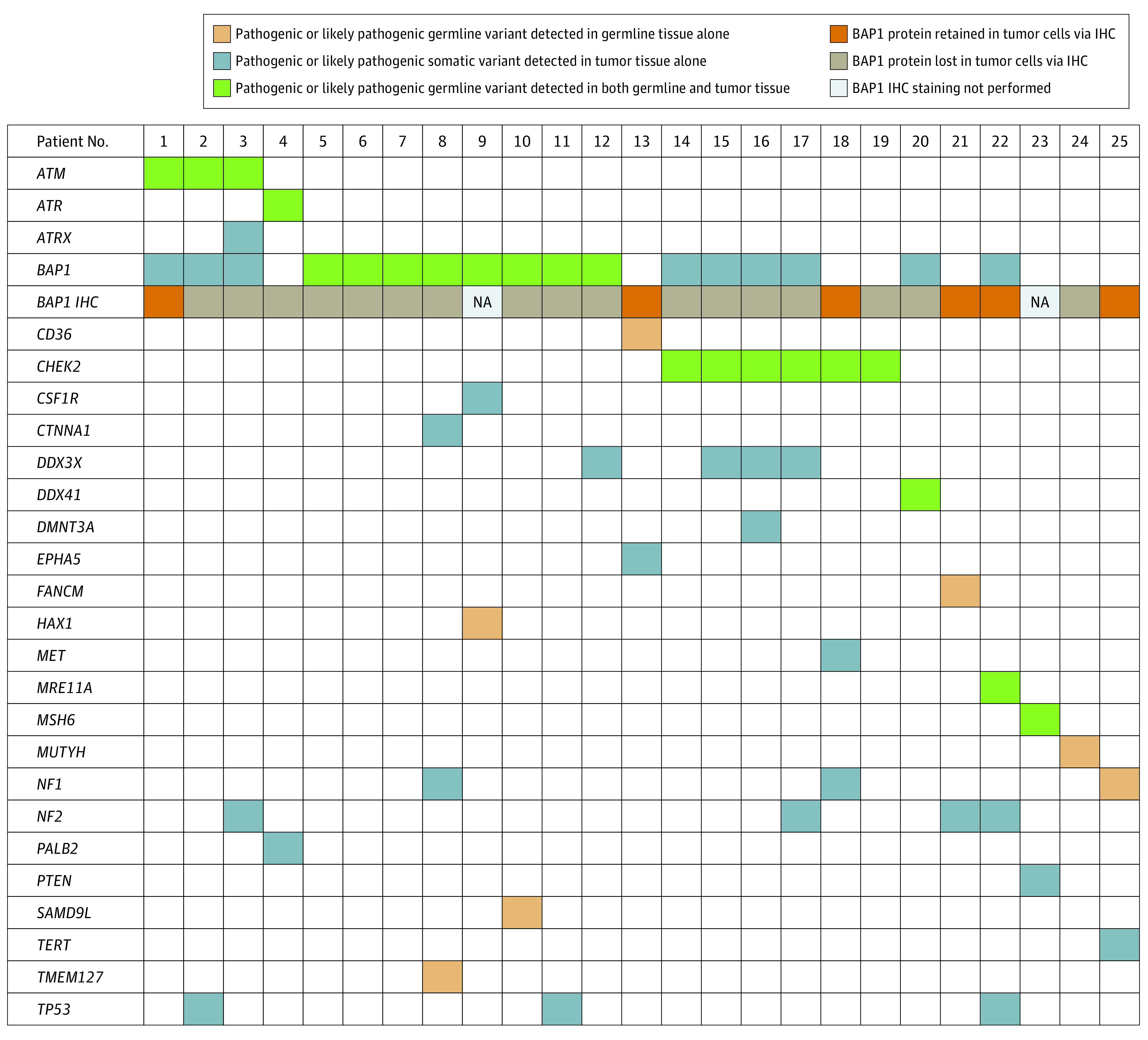

Plot of Somatic and Germline P/LP Variants

The tumor variant allele frequency (VAF) for incidental germline P/LP variants was greater than 40% in 19 of the 20 variants for which VAF was available (Table 2). Only 1 germline variant, a frameshift variant in MSH6, had a tumor VAF less than 40% (Table 2). The most frequent somatic variants in patients with germline P/LP variants were in DDX3X (4 patients), NF2 (4 patients), and TP53 (3 patients) (Figure 2). Three of 8 patients (38%) with germline P/LP variants in BAP1 had second somatic hits in BAP1. The VAF of these second hits in BAP1 ranged from 18% to 25%. All known germline P/LP variants in the patient cohort were incidentally detected via tumor-only NGS panels that sequenced the same genes (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). A small number of patients had P/LP germline variants detected via dedicated germline sequencing only, as the genes of interest (CD36, FANCM, HAX1, MUTYH, SAMD9L, TMEM127) were not sequenced by our institution’s tumor-only NGS panel.

Figure 2. Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic Variants in Patients With Germline Pathogenic/Likely Pathogenic Variants.

IHC indicates immunohistochemistry; NA, not applicable.

Discussion

Multiple groups have shown tumor-based NGS will incidentally detect germline P/LP variants in many patients with otherwise unremarkable personal and family histories.23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 None of these studies have focused on patients with mesothelioma. Here, we demonstrate that 16% of unrelated patients (25 of 161) with mesothelioma carried P/LP germline variants associated with hereditary cancer syndromes. These variants were incidentally detected via tumor-only sequencing. Most patients (126 patients [78%]) in our cohort had variants detected via tumor-only NGS that warranted dedicated germline testing. The PPV of a potentially incidental germline P/LP variant on tumor-only testing was 20%. The high overall germline diagnostic yield in our cohort (25 patients [16%]) is similar to other tumor types in which universal germline genetic testing is now recommended, such as metastatic prostate cancer (12%-17%), epithelial ovarian cancer (18%-24%), and exocrine pancreatic cancer (15%).32,33 Universal genetic testing in all patients with cancer has been suggested as one approach to avoid missing any patients who harbor pathogenic germline variants. In 1 study10 of more than 2900 patients with cancer, 1 in 8 were found to be carrying a P/LP germline variant. Half of patients with P/LP germline variants did not meet guidelines for hereditary genetic testing. Given the high yield of patients with mesothelioma harboring a P/LP germline variant, which is similar to other cancer types where universal genetic testing is standard, it is reasonable to consider recommending universal germline screening in future mesothelioma treatment guidelines. Of note, only 1 patient in our cohort, a woman who had previously developed breast cancer in her 40s, would have met NCCN criteria for a hereditary cancer evaluation according to personal history.

We found patients with a family history of cancer had a higher likelihood of carrying a germline P/LP variant (92% vs 68%, respectively; P < .001) (Table 1). Despite this, we also identified germline variants in patients who did not have a family history of cancer. Given the importance of avoiding false negatives when deciding when to offer germline testing, family history alone is not a clinically acceptable surrogate for guiding germline testing decisions. We also found age at diagnosis, asbestos exposure, site of disease, and tumor histology were not associated with the presence or absence of a germline P/LP variant (Table 1). Tumor VAF has been proposed as a potential surrogate for germline variants.34 Once again, however, the importance of avoiding false-negative germline evaluations suggest that VAF alone should not be used as a surrogate for dedicated germline testing in patients with mesothelioma. Two patients in the germline P/LP variant cohort carried the CHEK2 p.I157T, which has variable classifications of pathogenicity.35,36 According to the high prevalence of germline P/LP variants in patients with mesothelioma (16%), the high prevalence of variants on tumor-only NGS that warrant dedicated germline evaluation (78%), the inability to use tumor-based NGS as a germline assay, the clinical importance of identifying hereditary cancer syndromes, and the rapidly decreasing cost of NGS, we are likely approaching a point at which universal germline testing of patients with mesothelioma warrants consideration.

Limitations

This study had limitations. One limitation is the 50 gene panel-based approach that we used for germline sequencing. This panel-based approach will have a lower diagnostic yield than more unbiased methods, such as whole exome or whole genome sequencing. However, panel-based sequencing is less expensive than more unbiased approaches, which improves the feasibility of implementing germline sequencing in a variety of clinical settings. Similar panel-based sequencing approaches have been used to establish the prevalence of germline variants in other tumor types.33 The high germline diagnostic yield (16%) in our cohort, despite our panel-based NGS approach and limited sample size, indicates that patients with mesothelioma represent a population that is at high risk for hereditary cancer syndromes regardless of sequencing approach and the size of panel used. We anticipate that the germline diagnostic yield in patients with mesothelioma will increase over time as more unbiased sequencing approaches are used. A second limitation is that our patient population was largely of European ancestry and was drawn from a single center, although the proportion of white patients in our retrospective study was similar to the proportion of patients with mesothelioma of European ancestry (93%) in larger data sets.37

Conclusions

In this case series of 161 patients with mesothelioma, 16% had confirmed germline P/LP variants. Given the implications of a hereditary cancer syndrome diagnosis for preventive care and familial counseling, clinical approaches for addressing incidental P/LP germline variants in tumor-only NGS are needed. Universal germline testing is likely needed for patients with mesothelioma.

eTable 1. Genes Sequenced on the Germline and Somatic Panels

eTable 2. Timeline of Multiple Cancer Diagnoses in Patients With Germline Variants

eTable 3. Immunohistochemical Characteristics

eTable 4. P/LP Somatic Variants Detected on Tumor NGS

eTable 5. rsID and ExAC Frequency of Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic Germline Variants

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Cantini L, Hassan R, Sterman DH, Aerts JGJV. Emerging treatments for malignant pleural mesothelioma: where are we heading? Front Oncol. 2020;10:343. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faig J, Howard S, Levine EA, Casselman G, Hesdorffer M, Ohar JA. Changing pattern in malignant mesothelioma survival. Transl Oncol. 2015;8(1):35-39. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassan R, Morrow B, Thomas A, et al. Inherited predisposition to malignant mesothelioma and overall survival following platinum chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(18):9008-9013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821510116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panou V, Gadiraju M, Wolin A, et al. Frequency of germline mutations in cancer susceptibility genes in malignant mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(28):2863-2871. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.5204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betti M, Casalone E, Ferrante D, et al. Germline mutations in DNA repair genes predispose asbestos-exposed patients to malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Lett. 2017;405:38-45. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo R, DuBoff M, Jayakumaran G, et al. Novel germline mutations in DNA damage repair in patients with malignant pleural mesotheliomas. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(4):655-660. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pastorino S, Yoshikawa Y, Pass HI, et al. A subset of mesotheliomas with improved survival occurring in carriers of BAP1 and other germline mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(35):JCO2018790352. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.79.0352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly MB, Pal T, Berry MP, et al. ; CGC; CGC; LCGC; CGC; CGC . Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(1):77-102. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbone M, Pass HI, Ak G, et al. Medical and surgical care of patients with mesothelioma and their relatives carrying germline BAP1 mutations. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(7):873-889. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samadder NJ, Riegert-Johnson D, Boardman L, et al. Comparison of universal genetic testing vs guideline-directed targeted testing for patients with hereditary cancer syndrome. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):230-237. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumann F, Flores E, Napolitano A, et al. Mesothelioma patients with germline BAP1 mutations have 7-fold improved long-term survival. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36(1):76-81. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bueno R, Stawiski EW, Goldstein LD, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat Genet. 2016;48(4):407-416. doi: 10.1038/ng.3520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung YP, Dong F, Torre M, Crum CP, Bueno R, Chirieac LR. Molecular characterization of diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(11):2269-2279. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0588-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein AM. Familial melanoma, pancreatic cancer and germline CDKN2A mutations. Hum Mutat. 2004;23(6):630. doi: 10.1002/humu.9247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu C, Hart SN, Polley EC, et al. Association between inherited germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes and risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2018;319(23):2401-2409. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.6228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asthagiri AR, Parry DM, Butman JA, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 2. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1974-1986. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60259-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocca V, Blandino G, D’Antona L, Iuliano R, Di Agostino S. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome: mutation of TP53 is a biomarker of hereditary predisposition to tumor: new insights and advances in the treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(15):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snijders Blok L, Madsen E, Juusola J, et al. ; DDD Study . Mutations in DDX3X are a common cause of unexplained intellectual disability with gender-specific effects on Wnt signaling. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(2):343-352. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. ; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405-424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadri S, Long BC, Mujacic I, et al. Clinical validation of a next-generation sequencing genomic oncology panel via cross-platform benchmarking against established amplicon sequencing assays. J Mol Diagn. 2017;19(1):43-56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters S, Scherpereel A, Cornelissen R, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy in patients with unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma: 3-year outcomes from CheckMate 743. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(5):488-499. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.01.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baas P, Scherpereel A, Nowak AK, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (CheckMate 743): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10272):375-386. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32714-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maani N, Panabaker K, McCuaig JM, et al. Incidental findings from cancer next generation sequencing panels. NPJ Genom Med. 2021;6(1):63. doi: 10.1038/s41525-021-00224-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drazer MW, Kadri S, Sukhanova M, et al. Prognostic tumor sequencing panels frequently identify germ line variants associated with hereditary hematopoietic malignancies. Blood Adv. 2018;2(2):146-150. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017013037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catenacci DV, Amico AL, Nielsen SM, et al. Tumor genome analysis includes germline genome: are we ready for surprises? Int J Cancer. 2015;136(7):1559-1567. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slavin TP, Banks KC, Chudova D, et al. Identification of incidental germline mutations in patients with advanced solid tumors who underwent cell-free circulating tumor DNA sequencing. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(35):JCO1800328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott AJ, Tokaz MC, Jacobs MF, Chinnaiyan AM, Phillips TJ, Wilcox RA. Germline variants discovered in lymphoma patients undergoing tumor profiling: a case series. Fam Cancer. 2021;20(1):61-65. doi: 10.1007/s10689-020-00192-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meric-Bernstam F, Brusco L, Daniels M, et al. Incidental germline variants in 1000 advanced cancers on a prospective somatic genomic profiling protocol. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(5):795-800. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al. ; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics . ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15(7):565-574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yushak ML, Han G, Bouberhan S, et al. Patient preferences regarding incidental genomic findings discovered during tumor profiling. Cancer. 2016;122(10):1588-1597. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray SW, Hicks-Courant K, Cronin A, Rollins BJ, Weeks JC. Physicians’ attitudes about multiplex tumor genomic testing. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(13):1317-1323. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hampel H, Yurgelun MB. Point/counterpoint: is it time for universal germline genetic testing for all GI cancers? J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(24):2681-2692. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uson PLS Jr, Samadder NJ, Riegert-Johnson D, et al. Clinical impact of pathogenic germline variants in pancreatic cancer: results from a multicenter, prospective, universal genetic testing study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021;12(10):e00414. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLeonardis K, Hogan L, Cannistra SA, Rangachari D, Tung N. When should tumor genomic profiling prompt consideration of germline testing? J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(9):465-473. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu C, Wang QS, Wang YJ. The CHEK2 I157T variant and colorectal cancer susceptibility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(5):2051-2055. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.5.2051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han FF, Guo CL, Liu LH. The effect of CHEK2 variant I157T on cancer susceptibility: evidence from a meta-analysis. DNA Cell Biol. 2013;32(6):329-335. doi: 10.1089/dna.2013.1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henley SJ, Larson TC, Wu M, et al. Mesothelioma incidence in 50 states and the District of Columbia, United States, 2003-2008. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2013;19(1):1-10. doi: 10.1179/2049396712Y.0000000016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Genes Sequenced on the Germline and Somatic Panels

eTable 2. Timeline of Multiple Cancer Diagnoses in Patients With Germline Variants

eTable 3. Immunohistochemical Characteristics

eTable 4. P/LP Somatic Variants Detected on Tumor NGS

eTable 5. rsID and ExAC Frequency of Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic Germline Variants

Data Sharing Statement