Abstract

Context

Type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for incident dementia but whether risk and treatment/prevention strategies differ by diabetes subgroup is unknown.

Objective

We assessed (1) whether specific type 2 diabetes (T2D) subgroups are associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or probable dementia (PD), and (2) whether T2D subgroups modified the association of the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) multidomain intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) with MCI/PD.

Methods

We included 3760 Look AHEAD participants with T2D and overweight or obesity randomly assigned to 10 years of ILI or diabetes support and education. We used k-means clustering techniques with data on age of diabetes diagnosis, body mass index, waist circumference, and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) to characterize diabetes subgroups at randomization. Prevalent MCI/PD were centrally adjudicated based on standardized cognitive tests and other health information 10 to 13 years after randomization. We estimated marginal probabilities for prevalent MCI/PD among T2D subgroups with adjustment for potential confounders and attrition and examined whether ILI modified any associations.

Results

Four distinct T2D subgroups were identified, characterized by older age at diabetes onset (43% of sample), high HbA1c (13%), severe obesity (23%), and younger age at onset (22%). Unadjusted prevalence of MCI/PD (314 cases, 8.4%) differed across T2D subgroup (older onset = 10.5%, severe obesity = 9.0%, high HbA1c = 7.9%, and younger onset = 4.0%). Adjusted probability for MCI/PD within T2D subgroup was highest for the severe obesity subgroup and lowest for the younger onset subgroup but did not differ by ILI arm (interaction P value = 0.84).

Conclusions

Among individuals with T2D and overweight or obesity, probability of MCI/PD differed by T2D subgroup. Probability of MCI/PD was highest for a subgroup characterized by severe obesity.

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier

Keywords: type 2 diabetes subgroups, mild cognitive status and probable dementia, intensive lifestyle intervention

The Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) multidomain intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI), compared with a control condition of diabetes support and education (DSE), was not associated with overall between-arm differences in scores on tests of cognitive function or prevalence of cognitive impairment (1-3). However, subgroup analyses suggest that ILI may be associated with cognitive benefit for individuals with overweight body mass index (BMI) and harm for individuals with severe obesity (1, 2). We previously characterized 4 distinct diabetes subgroups in Look AHEAD with respective qualitative disease hallmarks of older age at onset, younger age at onset, high glycated hemoglobin (previously termed poor glucose control), and severe obesity; these subgroups are determined by probabilistic statistical clustering methods and not defined by absolute categorization (4). Importantly, randomization to ILI vs DSE was associated with differences in the incidence of major cardiovascular disease (CVD) events that varied by diabetes subgroup. Alarmingly, randomization to ILI, compared with DSE, was associated with relatively greater incidence of CVD events for the subgroup with high glycated hemoglobin at enrollment. These prior findings demonstrate potential for diabetes subgrouping approaches to tailor CVD prevention strategies that maximize benefit and avoid harm.

There is a critical need to understand whether diabetes treatment and prevention strategies differ by diabetes subgroup in their effect on prevention of other prevalent and debilitating diabetes complications. Diabetes is a risk factor for incident dementia, with stronger causal evidence in relation to risk for vascular dementia than Alzheimer’s disease (5-7). Whether diabetes subgroups differ in risk for mild cognitive impairment (MCI)/probable dementia, and separately, whether ILI is differentially associated with MCI/probable dementia according to diabetes subgroups are 2 important clinical questions. With answers to these questions, we can develop interventions targeted to groups of individuals with diabetes who would benefit and/or avoid cognitive harm from intensive lifestyle modification. We had 2 objectives in this secondary analysis of the Look AHEAD intervention trial. First, to assess whether the prevalence of MCI and probable dementia vary among diabetes subgroups, and second, to assess whether ILI may alter this association. Based on our prior findings in observational cohorts and Look AHEAD, we hypothesized that diabetes subgroups would be associated with differential prevalence of MCI/probable dementia and that the association of ILI with prevalence of MCI/probable dementia would differ by diabetes subgroup (1, 2, 8).

Methods

The Look AHEAD trial study design and methods have been described (9). Look AHEAD was designed as a randomized controlled trial among individuals with T2D and overweight or obesity. From August 2001 through April 2004, 5145 participants were recruited at 16 clinical sites across the United States. Eligibility criteria for Look AHEAD included age 45 to 76 years; T2D verified by the use of glucose-lowering medication, a physician’s report, or glucose levels; and a BMI of ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 (≥ 27.0 kg/m2 if taking insulin). Individuals were excluded from study participation for any of the following: glycated hemoglobin level (HbA1c) of > 11% (> 97 mmol/mol); systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 160 mm Hg; diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 100 mm Hg; triglyceride level ≥ 6.77 mmol/L; inability to complete a valid maximal exercise test; and lacking an established relationship with a primary care provider. Cognitive function was not assessed at baseline; however, eligibility criteria (successful completion of run-in and approval by a behaviorist after an evaluation for barriers to adherence) likely precluded the enrollment of participants with major cognitive deficits. Participants provided informed consent and local institutional review boards approved the study protocol.

Study Intervention

Study participants were randomly assigned 1:1 within clinical site to receive either a multidomain intensive lifestyle intervention or a control condition of diabetes support and education (9-11). The intervention aimed to achieve and maintain participant weight loss of ≥ 7% via decreased caloric intake and increased physical activity. Participants who were randomized to DSE were invited to 3 group educational sessions each year in the first 4 years of the trial, reduced thereafter to 1 annual session. All adjustments to medications were made by the patient’s health care provider, with the exception of temporary changes in glucose-lowering medications made by study staff to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia in the ILI group. While participants were not masked to intervention allocation, nonintervention study staff and investigators were masked to intervention status. On September 14, 2012, on the basis of a futility analysis for the parent trial primary cardiovascular outcome, the intervention was terminated and participants were invited to continue participation in an observational phase. At this point, median duration of the intervention was 9.6 years (12).

Clinical Assessments

At baseline and annual study clinic visits, staff members certified in assessment procedures measured height, weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure. With participants in light clothing, height and weight were measured in duplicate using a standard stadiometer and digital scale, respectively. Resting seated blood pressure was measured in duplicate with a Dinamap Monitor Pro100 automated device. Fasting blood was drawn, aliquoted, and samples were shipped on dry ice to the Look AHEAD Central Biochemistry Laboratory (Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories, Seattle, WA,) where analyses were performed. HbA1c was measured using a dedicated ion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography instrument (Bio-Rad Variant II) (13). Interviewer-administered questionnaires were used to collect information on participant medical history, employment, education, family income, prior pregnancies, smoking, prescription medications, alcohol use, and family medical history.

Cognitive Assessment and Adjudication of Cognitive Status

Centrally trained, certified, and masked study staff conducted standardized assessments of cognitive function between August 2013 and December 2014 (10-13 years after enrollment) during a postintervention continuation of Look AHEAD. The neurocognitive battery included Trail Making Test Parts A and B (14), Modified Stroop Color and Word Test (15, 16), Digit Symbol-Coding Test (17), Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (18), and the Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MSE) (19). A masked panel of experts adjudicated cognitive status to identify cases of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and probable dementia (1). Participants whose 3MSE test score fell below prespecified age- and education-specific cut points for their 2013-2014 cognitive assessment were considered potential cases (20). These cases were triggered for telephone administration of the Functional Assessment Questionnaire to a friend or family member previously designated by the participant and who could respond to questions on functional status in instrumental activities of daily living (21). Two adjudicators independently reviewed all cognitive test scores, responses to the Functional Assessment Questionnaire, depressive symptoms scores, and medical and health information to make their primary classification (no impairment, MCI, probable dementia). When MCI was identified, a secondary classification of subtype was made as amnestic single domain, amnestic multiple domain, nonamnestic single domain, or nonamnestic multiple domain (22). Adjudicators used a separate classification of “cannot classify” if they could not make a confident classification due to a variety of reasons (eg, depression, illness, incomplete data). When adjudicators agreed on the primary classification, it was recorded as final. In instances of disagreement, the case was referred to the 5-member committee for discussion until consensus was reached. No attempt was made to subtype probable dementia cases because Look AHEAD lacked the necessary tests to do so (eg, imaging, amyloid imaging, tau). The final outcome variable was binary cognitive status (no MCI or probable dementia vs MCI or probable dementia).

Statistical Analysis

We used the same statistical approach to characterize diabetes subgroups as our prior study in Look AHEAD and similar to other studies on this topic (4, 23-25). Briefly, we applied k-means clustering to characterize diabetes subgroups at the time of randomization. Clustering variables included age at diabetes diagnosis, and BMI, waist circumference, and HbA1c at the time of randomization. These variables were chosen for their importance in predicting T2D development or monitoring diabetes progression, availability for ascertainment in observational and clinical settings, and overlap with prior research on diabetes subgroups (23-25). We used two-step fully conditional specification imputation methods to generate missing data for age at diagnosis (n = 32 observations), waist circumference (n = 6 observations), and covariates (n = 115 missing education and n = 40 missing diabetes duration), creating 10 unique imputed datasets (26, 27). Prior to the clustering step, we regressed sex on the clustering variables, separately, and used the residuals as the value for each clustering variable in the k-means models. We calculated Jaccard and Silhouette index values to assess cluster assignment, stability, and within-cluster similarity. Collectively, these metrics and cluster model statistics supported cluster numbers of 3 or 4 as those which would best fit the data and we ultimately selected 4 clusters (subgroups) because this permitted better separation between cluster profiles for each of the clustering characteristics (4).

We excluded from analysis 539 participants who died before 2013-2014, 804 individuals who declined further follow-up, and 42 participants for whom cognitive status was determined “cannot classify” for an analytic sample of 3760. We calculated stabilized inverse probability of attrition weights (IPW) to account for these potential selective exclusions, when attrition is related to both potential for exposure and development of the outcome (28). Probability of not being lost to follow-up is calculated for each observation based on baseline characteristics. This probability is used to create a unique analytic weight for each observation which is included in the final statistical model and should be distributed around the sample mean IPW value of 1. We used logistic regression models with weighting statements to estimate predicted marginal probabilities and relative risks for MCI/probable dementia in 2013-2014. Despite not having obtained cognitive status at baseline, we assume that MCI/probable dementia cases ascertained herein are largely incident. The rigorous screening and intervention protocols lead us to believe the cohort was likely cognitively unimpaired at randomization. We cannot verify participants were free of MCI/probable dementia at randomization, but potential prevalent cases were likely balanced by randomization arm. When the primary exposure was diabetes subgroup, the model adjustments included data collected at the time of randomization for age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, HbA1c, diabetes duration, diabetes medication use, BMI, smoking status, SBP, blood pressure lowering medication use, history of CVD, intervention, and study site. We assessed whether diabetes subgroup overall was associated with MCI/probable dementia (Χ2 with 3 degrees of freedom). We also assessed whether ILI (main exposure) was associated with differential marginal probability for MCI/probable dementia according to diabetes subgroups by including a product term between ILI and diabetes subgroup in the model. Where ILI was assessed as the main exposure, analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. We assessed between-arm differences in weight, HbA1c, SBP, DBP, and low- and high-density lipoprotein (LDL and HDL) cholesterol during the intervention by T2D subgroup. All analyses that included T2D subgroups were not prespecified in the parent trial. A two-sided alpha of 0.05 was used. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and STATA software version 13.0 (Stata-Corp, College Station, TX, USA) were used for analysis.

Results

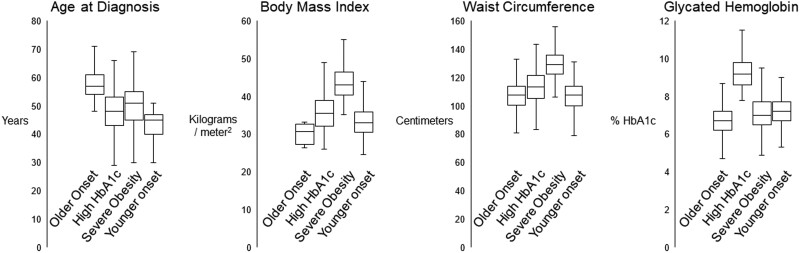

The 4 diabetes subgroups were qualitatively characterized by older age at diabetes onset (43% of sample), high HbA1c (13%), severe obesity (23%), and younger age at onset (22%). Figure 1 presents distributions for each clustering variable by diabetes subgroup. Random allocation to intervention arm was similar within diabetes subgroups (Table 1). Women were less likely to be in the older onset diabetes subgroup than expected. The distributions of race and ethnicity and educational attainment differed across subgroups. Diabetes duration and medication use were lowest for the older onset subgroup and highest for the younger onset subgroup. Systolic blood pressure was highest in the high HbA1c and severe obesity subgroups and blood pressure medication use was highest in the severe obesity subgroup. The distribution of diabetes subgroups and within-subgroup characteristics among the 3760 Look AHEAD participants included in this analysis (73% of original cohort) were similar as the full cohort. Those excluded from analysis were more likely to be older, male, White, and to have higher BMI and blood pressure (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Clustering variables according to diabetes subgroup in the Look AHEAD cohort. The distribution presented for each characteristic includes the minimum, 25th percentile, 50th percentile (median), 75th percentile, and maximum value.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics according to diabetes subgroup among Look AHEAD trial participants with cognitive status determination in 2013-2014

| Subgroup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Older onset | High HbA1c | Severe obesity | Younger onset |

| N (% total) | 1614 (43%) | 483 (13%) | 850 (23%) | 813 (22%) |

| Clustering characteristics | ||||

| ȃWaist circumference, cm (SD) | 107.3 (9.5) | 113.5 (11.2) | 130.3 (10.6) | 107.0 (9.9) |

| ȃBody mass index, kg/m2 (SD) | 32.9 (3.6) | 35.7 (4.5) | 43.7 (4.5) | 33.3 (3.8) |

| ȃGlycated hemoglobin, % (SD) | 6.7 (0.7) | 9.3 (0.9) | 7.1 (0.9) | 7.2 (0.8) |

| ȃGlycated hemoglobin, mmol/mol (SD) | 50.1 (7.8) | 78.6 (10.2) | 54.4 (9.9) | 55.0 (8.3) |

| ȃAge at diabetes diagnosis, years (SD) | 57.5 (5.2) | 47.7 (7.1) | 50.7 (7.3) | 43.1 (6.2) |

| Demographic and clinical risk factors | ||||

| ȃIntensive lifestyle intervention, n (%) | 811 (50%) | 236 (49%) | 427 (50%) | 421 (52%) |

| ȃAge at randomization, years (SD) | 61.6 (5.5) | 56.2 (5.8) | 56.5 (6.2) | 54.1 (5.9) |

| ȃFemale, n (%) | 944 (58%) | 306 (63%) | 531 (62%) | 523 (64%) |

| Race and ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| ȃAfrican American (not Hispanic) | 240 (15%) | 101 (21%) | 152 (18%) | 127 (16%) |

| ȃȃAmerican Indian/Native American/Alaskan Native | 63 (4%) | 37 (8%) | 43 (5%) | 68 (8%) |

| ȃȃAsian/Pacific Islander | 17 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 2 (<1%) | 16 (2%) |

| ȃȃWhite (not Hispanic) | 1055 (65%) | 243 (50%) | 558 (66%) | 443 (54%) |

| ȃȃHispanic | 205 (13%) | 90 (19%) | 78 (9%) | 137 (17%) |

| ȃȃOther/multiple | 34 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 17 (2%) | 22 (3%) |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| ȃȃHigh school or less | 306 (19%) | 122 (25%) | 144 (17%) | 169 (21%) |

| ȃȃSome college | 785 (49%) | 235 (49%) | 470 (55%) | 431 (53%) |

| ȃȃCollege graduate or more | 476 (29%) | 114 (24%) | 221 (26%) | 193 (24%) |

| ȃȃMissing (ultimately imputed) | 47 (3%) | 12 (2%) | 15 (2%) | 20 (2%) |

| Diabetes duration, median years (IQR) | 3 (1, 6) | 7 (4, 12) | 5 (2, 9) | 10 (5, 16) |

| Diabetes medication use, n (%) | 1264 (78%) | 464 (96%) | 767 (90%) | 759 (93%) |

| Insulin use, n (%) | 135 (8%) | 165 (34%) | 154 (18%) | 232 (29%) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg (SD) | 127 (16) | 130 (17) | 130 (17) | 126 (17) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg (SD) | 70 (9) | 71 (10) | 70 (9) | 71 (10) |

| Blood pressure medication use, n (%) | 1158 (72%) | 330 (68%) | 659 (78%) | 568 (70%) |

| Prior history of CVD, n (%) | 215 (14%) | 43 (9%) | 86 (10%) | 76 (10%) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | ||||

| ȃȃNo regular consumption | 1056 (65%) | 338 (70%) | 607 (71%) | 564 (69%) |

| ȃȃ≤1 drink per day | 161 (10%) | 43 (9%) | 86 (10%) | 77 (9%) |

| ȃȃ>1 drink per day | 397 (25%) | 102 (21%) | 157 (18%) | 172 (21%) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| ȃȃNever | 811 (50%) | 255 (53%) | 435 (51%) | 453 (56%) |

| ȃȃFormer | 752 (47%) | 194 (40%) | 383 (45%) | 315 (39%) |

| ȃȃCurrent | 49 (3%) | 33 (7%) | 30 (4%) | 44 (5%) |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; IQR, interquartile range; mm Hg, millimeters mercury.

Values are counts (column percentage, %) or mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics according to inclusion and exclusion into the study sample from the Look AHEAD trial

| Characteristics | Overall trial | Excluded | Included |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 5145 | 1385 | 3760 |

| Clustering characteristics | |||

| ȃWaist circumference, cm (SD) | 113.9 (13.9) | 115.8 (14.1) | 113.2 (13.8) |

| ȃBody mass index, kg/m2 (SD) | 35.9 (5.9) | 36.3 (5.9) | 35.8 (5.9) |

| ȃGlycated hemoglobin, % (SD) | 7.3 (1.2) | 7.4 (1.2) | 7.2 (1.1) |

| ȃGlycated hemoglobin, mmol/mol (SD) | 56.1 (12.8) | 57.2 (13.3) | 55.6 (12.5) |

| ȃAge at diabetes diagnosis, years (SD) | 51.9 (8.6) | 52.9 (8.8) | 51.6 (8.4) |

| Demographic and clinical risk factors | |||

| ȃIntensive lifestyle intervention, n (%) | 2570 (50%) | 675 (49%) | 1895 (50%) |

| ȃAge at randomization, years (SD) | 58.7 (6.8) | 60.4 (7.2) | 58.1 (6.6) |

| ȃFemale, n (%) | 3063 (60%) | 759 (55%) | 2304 (61%) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| ȃAfrican American (not Hispanic) | 804 (16%) | 184 (13%) | 620 (16%) |

| ȃAmerican Indian/Native American/Alaskan Native | 258 (5%) | 47 (3%) | 211 (6%) |

| ȃAsian/Pacific Islander | 50 (1%) | 12 (1%) | 38 (1%) |

| ȃWhite (not Hispanic) | 3252 (63%) | 953 (69%) | 2299 (61%) |

| ȃHispanic | 680 (13%) | 170 (12%) | 510 (14%) |

| ȃOther/multiple | 100 (2%) | 18 (1%) | 82 (2%) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| ȃHigh school or less | 1020 (20%) | 279 (21%) | 741 (20%) |

| ȃSome college | 2622 (52%) | 701 (51%) | 1921 (52%) |

| ȃSome post college | 1388 (28%) | 384 (28%) | 1004 (27%) |

| Diabetes duration, median years (IQR) | 5 (2, 10) | 5 (2, 10) | 5 (2, 10) |

| Diabetes medication use, n (%) | 4504 (88%) | 1250 (90%) | 3254 (87%) |

| Insulin use, n (%) | 980 (19%) | 294 (21%) | 686 (18%) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg (SD) | 129 (17) | 131 (18) | 128 (17) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg (SD) | 70 (10) | 70 (10) | 70 (10) |

| Blood pressure medication use, n (%) | 3786 (74%) | 1071 (77%) | 2715 (72%) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | |||

| ȃNo regular consumption | 3492 (68%) | 927 (67%) | 2565 (68%) |

| ȃ≤ 1 drink per day | 504 (10%) | 137 (10%) | 367 (10%) |

| ȃ> 1 drink per day | 1149 (22%) | 321 (23%) | 828 (22%) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| ȃNever | 2576 (50%) | 622 (45%) | 1954 (52%) |

| ȃFormer | 2331 (45%) | 687 (50%) | 1644 (44%) |

| ȃCurrent | 227 (5%) | 71 (5%) | 156 (4%) |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; IQR, Interquartile range; mm Hg, millimeters mercury.

Values are counts (column percentage, %) or mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

There were 314 cases (8.4%) of MCI/probable dementia in 2013-2014 (Table 3). Cases were more likely to be MCI than probable dementia overall (78% of cases were MCI). The severe obesity subgroup had the greatest proportion of cases as MCI (84%) while the older age at onset subgroup had the greatest proportion of cases as probable dementia (25%). Before adjustment, the probability of MCI/probable dementia differed across diabetes subgroups ranging from 10.5% for the older onset subgroup to 9.0% for severe obesity, 7.9% for high HbA1c, and 4.0% for the younger onset subgroup. Compared to the older onset group, all other diabetes subgroups had a lower unadjusted relative risk for MCI/probable dementia. After adjustment for age, gender, race and ethnicity, and education, the marginal probability for MCI/probable dementia among the high HbA1c and severe obesity subgroups was higher than the older onset group and the corresponding relative risks were greater than 1, compared to the older onset subgroup. After further adjustment for HbA1c, diabetes duration, diabetes medication use, BMI, smoking status, SBP, blood pressure medication use, prior history of CVD, intervention arm, and clinic site, individuals in the severe obesity subgroup had 77% higher marginal probability of MCI/probable dementia compared to the older onset subgroup. In contrast, the marginal probability of MCI/probable dementia was 32% lower for the younger onset subgroup compared to the older onset subgroup. Overall, diabetes subgroup status at randomization was associated with MCI/probable dementia in 2013-2014 (Χ2 3 degrees of freedom, P value = 0.001).

Table 3.

Cognitive status according to diabetes subgroup among Look AHEAD participants 2013-2014

| Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or probable dementia | Older onset | High HbA1c | Severe obesity | Younger onset | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases/number at risk | 167/1614 | 38/483 | 77/850 | 32/813 | |

| MCI, n (% cases)/probable dementia, n (% cases) | 125 (75%)/42 (25%) | 31 (82%)/7 (18%) | 65 (84%)/12 (16%) | 25 (78%)/7 (22%) | |

| Marginal probability (SE), unadjusted | 10.5 (0.8) | 7.9 (1.2) | 9.0 (1.0) | 4.0 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | Reference | 0.76 (0.50, 1.02) | 0.86 (0.64, 1.09) | 0.38 (0.24, 0.52) | |

| Marginal probability (SE), Model 1 | 7.9 (0.6) | 10.1 (1.5) | 10.7 (1.1) | 6.2 (1.0) | 0.01 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | Reference | 1.28 (0.86, 1.70) | 1.36 (1.01, 1.70) | 0.79 (0.50, 1.08) | |

| Marginal probability (SE), Model 2 | 7.7 (0.7) | 8.8 (1.8) | 13.7 (2.0) | 5.4 (1.1) | 0.003 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | Reference | 1.15 (0.59, 1.70) | 1.78 (1.15, 2.42) | 0.70 (0.39, 1.01) | |

| Marginal probability (SE), Model 3 | 7.6 (0.7) | 9.0 (1.9) | 14.1 (2.0) | 5.5 (1.1) | 0.002 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | Reference | 1.18 (0.61, 1.76) | 1.85 (1.19, 2.51) | 0.72 (0.40, 1.03) | |

| Marginal probability (SE), Model 4 | 7.8 (0.7) | 8.8 (1.8) | 13.8 (2.0) | 5.3 (1.0) | 0.001 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | Reference | 1.13 (0.59, 1.68) | 1.77 (1.14, 2.41) | 0.68 (0.38, 0.98) |

Abbreviation: HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin.

Adjustments: Model 1 includes age, gender, race and ethnicity, and education. Model 2 includes Model 1 plus glycated hemoglobin, diabetes duration, diabetes medication use, and body mass index. Model 3 includes Model 2 plus smoking status, systolic blood pressure, blood pressure lowering medication use, prior history of cardiovascular disease. Model 4 includes Model 3 plus intervention arm and study site.

P value is for the overall diabetes subgroup variable association with cognitive status (Χ2, 3 degrees of freedom).

Participants randomized to ILI had greater improvements in weight, HbA1c, SBP, DBP, and HDL compared with DSE (Supplementary Figs. S1-S6) (29). Improvements for each of these measurements for the ILI arm were greatest at year 1 for each T2D subgroup and diminished over time, although between-arm differences were noted out to year 10 for weight and HbA1c for a couple subgroups.

We assessed for differential associations and did not observe evidence for effect modification of the association between ILI and MCI/probable dementia by diabetes subgroup (P = 0.84). The marginal probability of MCI/probable dementia was similar comparing ILI to DSE within diabetes subgroup (Table 4). The distribution statistics for IPWs for attrition are presented in Supplementary Table S7 (29). Results indicate median IPW did not differ by cognitive status or diabetes subgroup, although the younger age at onset subgroup did have the narrowest range of IPWs.

Table 4.

Cognitive status among Look AHEAD participants in 2013-2014 according to intervention arm and diabetes subgroup at randomization

| Older onset | High HbA1c | Severe obesity | Younger onset | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild cognitive impairment or probable dementia | ILI | DSE | ILI | DSE | ILI | DSE | ILI | DSE |

| Number of cases/numbers at risk | 83/811 | 84/803 | 17/236 | 21/247 | 41/427 | 36/423 | 15/421 | 17/392 |

| Marginal probability of MCI/probable dementia (SE) | 10.1 (1.0) | 10.7 (1.1) | 7.1 (1.7) | 8.5 (1.7) | 9.6 (1.4) | 8.6 (1.4) | 3.6 (0.9) | 4.4 (1.0) |

| Relative risk comparing ILI to DSE | 0.95 | Ref. | 0.84 | Ref. | 1.12 | Ref. | 0.82 | Ref. |

| ȃ95% confidence limits | (0.68, 1.22) | (0.33, 1.36) | (0.64, 1.59) | (0.27, 1.38) | ||||

Abbreviations: DSE, diabetes support and education; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; ILI, intensive lifestyle intervention; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; ref., reference.

Model adjusted for diabetes subgroup, intervention arm, clinic site, prior history of cardiovascular disease, and diabetes subgroup*intervention arm interaction.

P for diabetes subgroup*intervention arm interaction = 0.84.

Discussion

In this study of the Look AHEAD intensive lifestyle intervention among individuals with type 2 diabetes and overweight or obesity, we applied diabetes subgroup characterization and assessed whether the lifestyle intervention was differentially associated with cognitive status 10 to 13 years after randomization. We characterized 4 distinct T2D subgroups at the time of randomization related to older age at diabetes onset, younger age at onset, high HbA1c, and severe obesity. We observed an overall association between T2D subgroup with subsequent mild cognitive impairment and probable dementia. After adjusting for demographic and clinical confounding factors, the prevalence for mild cognitive impairment or probable dementia was highest (14.1%) for the severe obesity subgroup, which was 23% of the sample and lowest (5.5%) for the younger onset subgroup which was 22% of the sample. We did not find evidence that the lifestyle intervention differed in prevention of mild cognitive impairment or probable dementia by T2D subgroup.

Based on our prior work in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) assessing diabetes subgroups and incident complications including dementia, we hypothesized that T2D subgroups would be associated with mild cognitive impairment or probable dementia in Look AHEAD (8). In MESA, we used a different approach in diabetes subgroup stratification and dementia classification was based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) hospital or death data and medication use. The highest risk of dementia in MESA was observed among a diabetes subgroup characterized by both early age at onset (age ≤45) and high central obesity. MESA participants were older at baseline and living with diabetes for longer duration, on average, compared with the Look AHEAD participants. The vascular damage in the brain from diabetes duration, obesity, and aging among this subgroup in MESA may be more advanced than in Look AHEAD. However, the cumulative incidence of dementia was lower in MESA (6.4% over 14 years) and these subgroup estimates were based on small event numbers and had low precision. Our current study extends this prior work with more rigorous and comprehensive assessment of cognitive function and adjudication of cognitive status and higher numbers of probable dementia cases within T2D subgroups to support statistical inference.

Prior work in Look AHEAD observed differential effects of ILI on cognitive outcomes according to obesity status, the hallmark of a T2D subgroup characterized here (1, 2). We hypothesized that the association of ILI with MCI/probable dementia would differ by T2D subgroups and that ILI would be associated with cognitive harm for the severe obesity subgroup. We did not find evidence to support a differential association of ILI with cognitive status by T2D subgroup. Previously, Espeland et al reported that the prevalence of MCI/probable dementia was inversely associated with BMI and that ILI was associated with better scores on cognitive tests 8 years after the start of the intervention among individuals with overweight but not obesity (2). Further, Espeland et al observed evidence that the effect of ILI on prevalent MCI/probable dementia changed direction of association across the spectrum of BMI from beneficial among individuals with overweight to harmful among those with severe obesity (1). Our findings do align with this prior work to an extent wherein we observed the highest adjusted marginal probability for MCI/probable dementia among the severe obesity T2D subgroup.

It is unclear why the severe obesity T2D subgroup had the highest marginal probability for MCI/probable dementia and not the subgroup characterized by high HbA1c. High blood glucose is associated with vascular damage and observational cohorts have observed a gradient of higher risk for MCI/probable dementia with worse glucose control in individuals with diabetes (30, 31). Although, interventions to lower glucose in individuals with diabetes have not proven effective at preventing cognitive complications (32, 33). Further, the Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle and metformin interventions for weight loss and glucose control were not associated with cognitive differences (34). As noted above, BMI status was inversely associated with prevalence of MCI/probable dementia in Look AHEAD (1). Our current finding of the highest marginal probability for MCI/probable dementia among the severe obesity subgroup suggests that T2D subgrouping approaches capture different information in relation to health outcomes than assessments of individual characteristics. In the current study, at baseline the severe obesity subgroup had some of the highest blood pressure levels, similar to the high HbA1c subgroup, in addition to the greatest use of blood pressure medications among the 4 subgroups and we adjusted for these blood pressure characteristics, although it is possible that differences in duration of adverse blood pressure profiles or other bias account for this association.

The following considerations should be used to inform interpretation and generalizability of our findings. Look AHEAD participants had T2D and overweight or obesity, but were able to complete physical fitness requirements, and had more favorable lipid and glucose profiles at enrollment than the USA population with diabetes (13). Cognitive status was first determined in the full Look AHEAD cohort in 2013-2014 and was not determined at enrollment. Therefore, individuals with MCI at the time of enrollment may be included in our analysis which may limit their ability to adhere to the intervention (reverse-causation) or individuals with MCI at enrollment may experience attrition differentially by diabetes subgroup (selection bias). Because 27% of the original trial population were excluded from this analysis, we used statistical weighting approaches to account for the select analytic sample. We characterized T2D subgroups among prevalent diabetes cases at a single point in time using data for characteristics that may be influenced by disease progression. An individual may be categorized to a different subgroup at the time of diabetes onset, and we do not assert that these T2D subgroups are absolute. Individuals were assigned membership to the most probable T2D subgroup based on their entire clustering profile, but participants could share defining characteristics of other subgroups. The number and composition of T2D subgroups defined by our approach might be different in other cohorts and with other approaches. Diabetes subgroups defined in Look AHEAD have similar patterns in age at onset, obesity, and HbA1c subgroup profile than those from other cohorts of individuals with T2D (23). These subgroup analyses were not prespecified in the parent trial design and should be interpreted as exploratory.

These findings are informative for several reasons. First, this is one of the largest studies on the topic of T2D subgroups to assess cognitive health outcomes and demonstrate strong heterogeneity in probability of MCI/probable dementia according to T2D subgroups characterized by data that is readily available in observational and clinical settings. Second, when added to our prior work in Look AHEAD these findings show that T2D subgroups are differentially associated with diabetes complications. Where the high HbA1c subgroup had the highest risk for incident CVD, the probability of MCI/probable dementia was highest in the severe obesity subgroup (4). Given the high vascular morbidity for the high HbA1c subgroup and observed stronger relation to vascular dementia than Alzheimer disease, we may have expected the highest risk for MCI/probable dementia among the high HbA1c subgroup. Third, the relationship of lifestyle intervention with cognitive health does not appear to differ by T2D subgroup. While these findings may not inform targeted MCI/probable dementia prevention strategies, they also suggest that there is no major cognitive harm from the intervention for a particular T2D subgroup. Together with our prior work, these findings provide support to subclassify T2D to better predict diabetes etiology and risk for complications, and to guide effective and efficient treatment and prevention (35, 36).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the Look AHEAD trial for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating investigators and institutions and study protocols can be found at https://www.lookaheadtrial.org/. This trial is registered at Clinicaltrials.gov: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00017953, Identifier: NCT00017953. M.P. Bancks is the guarantor of this work. As such, he takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis and affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported. All authors made substantial intellectual contributions participating in creating and designing the study, analyzing and interpreting the data, and reviewing this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final report for publication. This study used data from the Look AHEAD trial intervention phase, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through cooperative agreements with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. Additional funding was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NIH Office of Research on Women's Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources. Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (RR025758-04); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) (M01RR000056), the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) funded by the Clinical & Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 024153), and NIH grant (DK 046204); the VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; and the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346). Some of the information contained herein was derived from data provided by the Bureau of Vital Statistics, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The following organizations committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; OPTIFAST of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America. Digestive and Kidney Diseases; the National Institutes of Health; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- DSE

diabetes support and education

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin A1c

- ILI

intensive lifestyle intervention

- IPW

inverse probability weighting

- Look AHEAD

Action for Health in Diabetes study

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- MESA

Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

- PD

probable dementia

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

Contributor Information

Michael P Bancks, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA.

James Lovato, Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA.

Ashok Balasubramanyam, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Mace Coday, Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN 38163, USA.

Karen C Johnson, Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN 38163, USA.

Medha Munshi, Joslin Diabetes Center, Harvard Medical School, and Division of Gerontology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA 02445, USA.

Candida Rebello, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University System, Baton Rouge, LA 70808, USA.

Lynne E Wagenknecht, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA.

Mark A Espeland, Departments of Internal Medicine-Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine and Biostatistics and Data Science, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts to disclose. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NHLBI; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Data Availability

The data used for analysis during the current study were housed at the data coordinating center and are not available for public distribution. However, all data used for this analysis were supplied by Look AHEAD investigators to the NIDDK Central Repository and are publicly available at https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/studies/look-ahead/?query=Look%20AHEAD.

References

- 1. Espeland MA, Luchsinger JA, Baker LD, et al. Effect of a long-term intensive lifestyle intervention on prevalence of cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2026‐2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Bray GA, et al. Long-term impact of behavioral weight loss intervention on cognitive function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(9):1101‐1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rapp SR, Luchsinger JA, Baker LD, et al. Effect of a long-term intensive lifestyle intervention on cognitive function: action for health in diabetes study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):966‐972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bancks MP, Chen H, Balasubramanyam A, et al. Type 2 diabetes subgroups, risk for complications, and differential effects due to an intensive lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(5):1203‐1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xue M, Xu W, Ou YN, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 144 prospective studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;55:100944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomassen JQ, Tolstrup JS, Benn M, Frikke-Schmidt R. Type-2 diabetes and risk of dementia: observational and Mendelian randomisation studies in 1 million individuals. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doney ASF, Bonney W, Jefferson E, et al. Investigating the relationship between type 2 diabetes and dementia using electronic medical records in the GoDARTS bioresource. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(10):1973‐1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bancks MP, Carnethon M, Chen H, et al. Diabetes subgroups and risk for complications: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). J Diabetes Complicat. 2021;35(6):107915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, et al. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24(5):610‐628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, et al. The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(5):737‐752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wesche-Thobaben JA. The development and description of the comparison group in the Look AHEAD trial. Clin Trials. 2011;8(3):320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):145‐154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bray G, Gregg E, Haffner S, et al. Baseline characteristics of the randomised cohort from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3(3):202‐215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reitan RM. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8(3):271‐276. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol. 1935;18(6):643‐662. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Houx PJ, Jolles J, Vreeling FW. Stroop interference: aging effects assessed with the Stroop color-word test. Exp Aging Res. 1993;19(3):209‐224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wechsler D. WAIS-R Manual. The Psychologic Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(8):314‐318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yuspeh RL, Vanderploeg RD, Kershaw DA. Normative data on a measure of estimated premorbid abilities as part of a dementia evaluation. Appl Neuropsychol. 1998;5(3):149‐153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37(3):323‐329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment–beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the international working group on mild cognitive impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):240‐246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahlqvist E, Storm P, Käräjämäki A, et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: a data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(5):361‐369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zaharia OP, Strassburger K, Strom A, et al. Risk of diabetes-associated diseases in subgroups of patients with recent-onset diabetes: a 5-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(9):684‐694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bancks MP, Casanova R, Gregg EW, Bertoni AG. Epidemiology of diabetes phenotypes and prevalent cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes complications in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2014. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;158:107915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219‐242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yuan YC. Multiple imputation for missing data: concepts and new development (version 9.0). In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Annual SAS Users Group International Conference. Vol 49: Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2000:1‐11. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weuve J, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, et al. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology. 2012; 23(1):119‐128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bancks M. Supplementary material for Look AHEAD type 2 diabetes subgroups and cognitive status. Posted November 12, 2022. 10.6084/m9.figshare.21547080.v1 [DOI]

- 30. Rawlings AM, Sharrett AR, Albert MS, et al. The association of late-life diabetes status and hyperglycemia with incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia: the ARIC study. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(7):1248‐1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zheng B, Su B, Price G, Tzoulaki I, Ahmadi-Abhari S, Middleton L. Glycemic control, diabetic complications, and risk of dementia in patients with diabetes: results from a large U.K. Cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(7):1556‐1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2560‐2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murray AM, Hsu FC, Williamson JD, et al. ACCORDION MIND: results of the observational extension of the ACCORD MIND randomised trial. Diabetologia. 2017;60(1):69‐80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Luchsinger JA, Ma Y, Christophi CA, et al. Metformin, lifestyle intervention, and cognition in the diabetes prevention program outcomes study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(7):958‐965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ahlqvist E, Prasad RB, Groop L. 100 YEARS OF INSULIN: towards improved precision and a new classification of diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol. 2021;252(3):R59‐R70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Herder C, Roden M. A novel diabetes typology: towards precision diabetology from pathogenesis to treatment. Diabetologia. 2022;65(11):1770‐1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for analysis during the current study were housed at the data coordinating center and are not available for public distribution. However, all data used for this analysis were supplied by Look AHEAD investigators to the NIDDK Central Repository and are publicly available at https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/studies/look-ahead/?query=Look%20AHEAD.