Abstract

目的

探讨血浆致动脉硬化指数(atherogenic index of plasma,AIP)与儿童支气管哮喘的关系。

方法

回顾性选取2020年7月—2022年8月于南京医科大学附属常州第二人民医院住院治疗的86例支气管哮喘患儿为哮喘组,选取同期149例健康体检儿童为对照组。收集两组的临床资料,包括血清总胆固醇(total cholesterol,TC)、三酰甘油(triglycerides,TG)、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(high-density lipoprotein cholesterol,HDL-C)、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(low-density lipoprotein cholesterol,LDL-C)、血糖检测数据及身高、体重、体重指数(body mass index,BMI)、有无特异性皮炎、吸入性过敏原过敏史、哮喘家族史及喂养史等资料。采用多因素logistic回归分析研究AIP、TG及HDL-C与支气管哮喘的关系。采用受试者操作特征曲线(receiver operating characteristic curve,ROC曲线)评估AIP、TG、HDL-C预测支气管哮喘的价值。

结果

哮喘组AIP、TG水平显著高于对照组,HDL-C显著低于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);两组TC、LDL-C的比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。在调整身高、体重、有无特异性皮炎、吸入性过敏原过敏史、哮喘家族史、人工喂养、混合喂养及血糖前后,多因素logistic回归分析显示AIP、TG、HDL-C均与支气管哮喘相关(P<0.05)。ROC曲线分析发现AIP取-0.333是预测支气管哮喘的最佳临界值,灵敏度为80.2%,特异度为55.0%,阳性预测值为50.71%,阴性预测值为82.85%。比较AIP、TG、HDL-C预测支气管哮喘的AUC发现,AIP的AUC显著高于TG,差异有统计学意义(P=0.009),但AIP与HDL-C的AUC比较差异无统计学意义(P=0.686)。

结论

AIP、TG、HDL-C均与支气管哮喘相关。AIP对支气管哮喘的预测价值高于TG,与HDL-C的价值相当。

Keywords: 血浆致动脉硬化指数, 血脂, 哮喘, 儿童

Abstract

Objective

To explore the relationship between atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) and childhood asthma.

Methods

This retrospective study included 86 children with asthma admitted to the Changzhou Second People's Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing Medical University from July 2020 to August 2022 as the asthma group and 149 healthy children undergoing physical examination during the same period as the control group. Metabolic parameters including total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and blood glucose, as well as general information of the children such as height, weight, body mass index, presence of specific dermatitis, history of inhalant allergen hypersensitivity, family history of asthma, and feeding history, were collected. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to study the relationship between AIP, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and asthma. The value of AIP, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol for predicting asthma was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Results

The AIP and triglyceride levels in the asthma group were significantly higher than those in the control group, while high-density lipoprotein cholesterol was significantly lower (P<0.05). However, there was no significant difference in total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol between the two groups (P>0.05). Before and after adjusting for height, weight, presence of specific dermatitis, history of inhalant allergen hypersensitivity, family history of asthma, feeding method, and blood glucose, multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that AIP, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were associated with asthma (P<0.05). ROC curve analysis showed that the optimal cutoff value for predicting asthma with AIP was -0.333, with a sensitivity of 80.2%, specificity of 55.0%, positive predictive value of 50.71%, and negative predictive value of 82.85%. The area under the curve (AUC) for AIP in predicting asthma was significantly higher than that for triglycerides (P=0.009), but there was no significant difference in AUC between AIP and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (P=0.686).

Conclusions

AIP, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol are all associated with asthma. AIP has a higher value for predicting asthma than triglycerides and comparable value to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Keywords: Atherogenic index of plasma, Blood lipid, Asthma, Child

支气管哮喘(以下简称哮喘)是儿童最常见的慢性呼吸道疾病之一,影响了世界上1%~18%人口,不仅成为全球范围内严重的公共卫生问题,也造成了巨大的医疗资源消耗[1]。目前,越来越多的人认识到肥胖与哮喘的相关性[2]。有研究发现哮喘与肥胖所伴随的血脂异常有关,但研究结果不完全一致[3-5]。血浆致动脉硬化指数(atherogenic index of plasma,AIP)是三酰甘油(triglyceride,TG)和高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(high-density lipoprotein cholesterol,HDL-C)比值的对数转换[log(TG/HDL-C)]值,AIP能够在一定程度上反映人体动脉硬化及相关性疾病,是一项于2001年被人为定义的指数[6]。有研究证明AIP与其他重要的动脉粥样硬化指标显著相关,如低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(low-density lipoprotein cholesterol,LDL-C)和小而致密低密度脂蛋白(small dense low-density lipoproteins,sdLDL),并且可反映致动脉粥样硬化和保护性脂蛋白之间的关系,故AIP最初被构建为致血浆动脉粥样硬化的生物标志物[7-9]。有研究表明AIP比TG、HDL-C等单项血脂指标对临床血脂异常的检测特异性更高[10]。然而,目前国内外均未见AIP与哮喘关系的相关研究报道。因此,本课题组开展了此病例对照研究以探讨AIP与哮喘的关系。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 研究对象

选取2020年7月—2022年8月于南京医科大学附属常州第二人民医院儿科住院治疗的86例哮喘患儿作为哮喘组,选取同期行健康体检的149例健康儿童作为对照组。哮喘组纳入标准:(1)年龄2~13岁的汉族儿童;(2)根据全球哮喘防治创议(Global Initiative for Asthma,GINA)[2]确诊为哮喘;(3)就诊期间进行了血脂相关检测。哮喘组排除标准为:(1)患有可能引起血脂异常的疾病,如甲状腺功能减退、肾病综合征等;(2)使用过调脂药物;(3)患有严重肝肾疾病、先天性或慢性心肺疾病。对照组纳入标准:(1)年龄2~13岁的汉族儿童;(2)未确诊哮喘,既往无反复喘息病史;(3)就诊期间进行了血脂相关检测。排除标准与哮喘组相同。本研究已通过南京医科大学附属常州第二人民医院医学伦理委员会批准(伦审号:YLJSC010),并获得豁免知情同意。

1.2. 数据收集

记录两组儿童年龄、性别及有无特异性皮炎史、吸入性过敏原过敏史、哮喘家族史及喂养史,并在空腹状态下进行健康检查。使用校准后的平衡木秤进行体重测量,使用校准过的测距仪测量身高,并计算体重指数(body mass index,BMI);采用Olympus U5431全自动生化分析仪检测总胆固醇(total cholesterol,TC)、TG、LDL-C、HDL-C及血糖,检测过程严格按照试剂盒说明书进行。AIP计算公式为log(TG/HDL-C)。

1.3. 统计学分析

采用SPSS 26.0统计软件对数据进行统计学分析,图表采用GraphPad Prism 8.0软件绘制。符合正态分布并满足方差齐性的计量资料以均数±标准差( )表示,组间比较采用两样本t检验。非正态分布的计量资料以中位数(四分位数间距)[M(P 25,P 75)]表示,组间比较采用非参数检验。计数资料以例数和百分率(%)表示。两组间率的比较采用Person卡方检验或Fisher确切概率法。以是否有哮喘作为因变量,TC、TG、HDL-C、LDL-C、AIP作为自变量,进行多因素logistic回归分析,得到调整前数据模型(模型1)和调整了身高、体重、有无特异性皮炎、吸入性过敏原过敏史、哮喘家族史和人工喂养、混合喂养及血糖后的数据模型(模型2),分析AIP及血脂指标与哮喘的关系;采用受试者操作特征曲线(receiver operating characteristic curve,ROC曲线)评估AIP、TG、HDL-C预测哮喘的价值。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 两组一般情况比较

两组身高、体重及特异性皮炎病史、吸入性过敏原过敏史、哮喘家族史、人工喂养、混合喂养比例等指标的比较差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05),而年龄、性别、BMI、母乳喂养等指标的比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表1。

表1.

哮喘组与对照组一般资料比较

| 指标 | 对照组 (n=149) | 哮喘组 (n=86) | /t/Z值 | P值 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 年龄 ( ±s, 岁) | 5.6±2.9 | 6.2±2.6 | -1.478 | 0.141 |

| 性别 (男/女, 例) | 87/62 | 55/31 | 0.929 | 0.405 |

| 身高 [M(P 25, P 75), m] | 1.1(1.0, 1.2) | 1.2(1.1, 1.4) | -4.970 | <0.001 |

| 体重 [M(P 25, P 75), kg] | 17.0(15.0, 24.0) | 22.0(18.0, 28.3) | -4.239 | <0.001 |

| BMI ( ±s, kg/m2) | 16.8±4.5 | 16.2±3.5 | 0.952 | 0.342 |

| 特异性皮炎史 [例(%)] | 0(0) | 22(25.6) | - | <0.001# |

| 吸入性过敏原过敏史 [例(%)] | 0(0) | 57(66.3) | - | <0.001# |

| 哮喘家族史 [例(%)] | 0(0) | 2(2.3) | - | <0.001# |

| 喂养史 [例(%)] | ||||

| 人工喂养 | 17(11.4) | 2(2.3) | - | 0.013# |

| 母乳喂养 | 128(85.9) | 76(88.4) | 0.290 | 0.590 |

| 混合喂养 | 4(2.7) | 8(9.3) | - | 0.034# |

注:[BMI]体重指数;#采用Fisher确切概率法。

2.2. 两组代谢相关指标分析

哮喘组血糖、AIP、TG均显著高于对照组,而HDL-C低于对照组,两组比较差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05);而两组TC、LDL-C比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表2。

表2.

哮喘组与对照组代谢指标比较

| 指标 | 对照组 (n=149) | 哮喘组 (n=86) | t值 | P值 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 血糖 ( ±s, mmol/L) | 4.8±0.8 | 5.7±1.3 | -6.403 | <0.001 |

| TC ( ±s, mmol/L) | 4.0±0.6 | 3.9±0.7 | 1.001 | 0.318 |

| TG ( ±s, mmol/L) | 0.8±0.4 | 1.0±0.5 | -2.892 | 0.006 |

| HDL-C ( ±s, mmol/L) | 1.6±0.9 | 1.3±0.3 | 2.552 | 0.011 |

| LDL-C ( ±s, mmol/L) | 2.1±0.5 | 2.0±0.6 | 1.425 | 0.155 |

| AIP | -0.3±0.3 | -0.2±0.3 | -4.745 | <0.001 |

注:[TC]总胆固醇;[TG]三酰甘油;[HDL-C]高密度脂蛋白胆固醇;[LDL-C]低密度脂蛋白胆固醇;[AIP]血浆致动脉硬化指数。

2.3. 哮喘发生的相关危险因素分析

模型1中,TG、AIP与哮喘的发生呈正相关(P<0.05);而HDL-C与哮喘的发生呈负相关(P<0.05)。在模型2调整了身高、体重、有无特异性皮炎、吸入性过敏原过敏史、哮喘家族史和人工喂养、混合喂养及血糖等指标后,TG、AIP、HDL-C仍与哮喘有相关性(P<0.05),见表3。

表3.

哮喘发生的多因素分析

| 指标 | B | OR | P | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 模型1 | ||||

| TC | -0.230 | 0.795 | 0.317 | 0.506~1.247 |

| TG | 0.848 | 2.336 | 0.007 | 1.264~4.316 |

| HDL-C | -1.957 | 0.141 | <0.001 | 0.056~0.360 |

| LDL-C | -0.365 | 0.694 | 0.156 | 0.419~1.149 |

| AIP | 2.592 | 13.356 | <0.001 | 4.158~42.904 |

| 模型2 | ||||

| TC | -0.165 | 0.848 | 0.734 | 0.328~2.195 |

| TG | 1.008 | 2.741 | 0.048 | 1.011~7.437 |

| HDL-C | -3.849 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.002~0.234 |

| LDL-C | -0.456 | 0.634 | 0.431 | 0.213~1.886 |

| AIP | 3.210 | 24.787 | 0.006 | 2.541~241.762 |

注:[TC]总胆固醇;[TG]三酰甘油;[HDL-C]高密度脂蛋白胆固醇;[LDL-C]低密度脂蛋白胆固醇;[AIP]血浆致动脉硬化指数。模型1:未进行校正;模型2:校正身高、体重、有无特异性皮炎、有无吸入性过敏原过敏史、有无哮喘家族史、人工喂养、混合喂养、血糖。

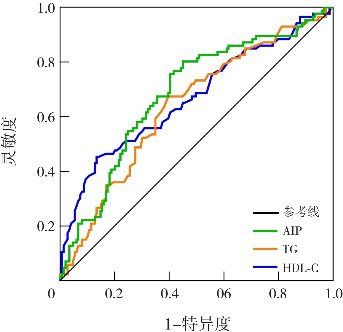

2.4. AIP与独立血脂指标对哮喘预测价值的比较

ROC曲线分析显示,对于哮喘的预测,AIP的曲线下面积(area under the curve,AUC)为0.682(95%CI:0.611~0.754,P<0.001),TG的AUC为0.638(95%CI:0.565~0.711,P<0.001),HDL-C的AUC为0.669(95%CI:0.595~0.743,P<0.001)。AIP的最佳临界值为-0.333,灵敏度为80.2%,特异度为55.0%,阳性预测值为50.71%,阴性预测值为82.85%。AIP的AUC显著高于TG,差异有统计学意义(Z=2.580,P=0.009),但AIP与HDL-C的AUC比较差异无统计学意义(Z=0.403,P=0.686)。见图1。

图1. AIP与独立血脂指标的ROC曲线 [TG]三酰甘油;[HDL-C]高密度脂蛋白胆固醇;[AIP]血浆致动脉硬化指数。.

3. 讨论

哮喘是儿童常见的呼吸道疾病,1990—2010年3次全国儿童哮喘患病率调查显示,我国儿童哮喘患病率呈逐年上升趋势[11]。但近年来随着社会经济及教育的发展,越来越多的研究发现,适当的早期干预可能会降低哮喘的患病率[12-13]。

有研究表明,性别、遗传、过敏等均可能是哮喘的诱发因素[14],其中伴或不伴有吸入性过敏原过敏史[15]及特异性皮炎病史[16]的儿童发生哮喘的风险有显著差异。本研究结果显示,两组吸入性过敏原过敏史及特异性皮炎病史比例的比较差异有统计学意义,这与已有研究结果[15-16]一致。国外有研究发现,不同时长母乳喂养及喂养方式对儿童哮喘发生有影响[17]。本研究显示哮喘组与对照组母乳喂养比例的比较差异无统计学意义,但考虑到纯母乳喂养持续时长对哮喘儿童的保护作用与儿童年龄相关[18],结果的差异可能与人种及参与儿童年龄大小有关。

多项研究表明,血脂与哮喘具有相关性,并且可能参与到哮喘的发生发展过程中[19-21]。目前解释血脂与哮喘关系的机制包括胆固醇转运和免疫转换。高胆固醇血症会阻碍免疫细胞的免疫反应,并减少细胞因子的分泌,同时也能增强免疫反应,这可能与免疫细胞细胞膜和细胞质中胆固醇率的改变有关[22]。脂筏是细胞膜上的微结构域,在细胞信号传递中发挥重要作用,胆固醇在脂筏中占据重要地位,胆固醇发生轻微变化便可激活巨噬细胞中的Toll样受体信号通路,这一通路可影响免疫细胞功能,从而改变免疫应答[23-25]。另一种可以解释二者关系的机制为免疫转换。Emruzi等[26]证实了高胆固醇血症可增加2型辅助性T细胞(T helper 2,Th2)相关细胞因子的mRNA表达,如白细胞介素-5、GATA结合蛋白3,此外也表明高胆固醇血症可降低1型辅助性T细胞(T helper 1,Th1)相关细胞因子的mRNA表达,如干扰素-γ、肿瘤坏死因子-α、白细胞介素-2、白细胞介素-6,并且在蛋白质水平也证实了同源基因mRNA的表达。由此可见,高胆固醇血症可以改变Th1/Th2比率,使得平衡向Th2方向倾斜。有研究表明Th2细胞及其细胞因子可能会控制2型高表型哮喘[27],在过敏原进入气道并被识别后,过敏原特异性Th2细胞会产生2型细胞因子(如白细胞介素-4、白细胞介素-5、白细胞介素-9、白细胞介素-13),导致气道壁累积大量嗜酸性粒细胞,使黏液过量产生,并促进过敏原特异性B细胞合成免疫球蛋白E,最终引起哮喘发作。

然而探索哮喘和血脂关联的临床研究结果并不完全一致。基于英国生物样本库(U.K. Biobank,UKB)数据的一项大样本研究表明,哮喘发生与较低的TG、LDL-C、TC相关,而与HDL-C呈正相关性[5]。一项检索了1999—2012年美国国家健康和营养检查调查数据库(National Health and Nutrition Examnation Survey,NHANES)的横断面研究中,未发现异常血脂或稳态模型胰岛素抵抗指数与儿童或青少年当前哮喘存在关联[4]。而在本研究中哮喘组与对照组TG和HDL-C差异均有统计学意义,并且高TG、低HDL-C与哮喘的发生呈正相关。血脂指标与哮喘相关性结论不一致的原因可能与种族及入选人群不同有关,另外也可能与单项血脂指标不能综合反映体内脂代谢紊乱有关。

AIP由Dobiásová等[6]提出,现被用于量化血脂水平,通常作为血脂异常相关性疾病(如动脉粥样硬化心血管疾病)的最佳指标。有研究表明AIP除了被认为是成人动脉粥样硬化风险的预测生物标志物之外,在评估心血管风险方面也比其他脂质变量更好[28]。国内的一项大样本病例对照研究表明,AIP与冠状动脉疾病显著相关,其调整后的OR为1.66,95%CI为1.367~2.016[29],这可能与AIP是sdLDL的一项极具代表性的指标有关。sdLDL因其有体表面积较大、更易透过内皮细胞、不易被清除且对比LDL-C更容易氧化等可引起内皮细胞损伤的特点,被认为有较强诱发动脉粥样硬化的能力[30]。与单项血脂指标相比,AIP能更好地反映体内脂代谢紊乱。本研究结果表明,高AIP的儿童患哮喘的风险可能会增加,特别是在多因素logistic回归分析调整了混杂因素后这一结果仍有统计学意义。此外,本研究显示,相比于传统独立血脂指标TG,AIP对哮喘的预测价值更高,并且得到AIP的最佳临界值为-0.333,表示当儿童AIP高于此值时需警惕患哮喘的可能。

本研究也有不足之处。首先,研究因素与结论是探索性的,其因果关系需进一步开展前瞻性研究予以验证;其次,由于缺乏特异性免疫球蛋白E或皮肤点刺试验数据,本研究无法根据哮喘表型(即特应性或非特应性哮喘)分析数据;最后,由于原始数据无肺功能数据的详细描述,也无法确定哮喘严重程度与AIP之间的关系。尽管存在以上不足,但本研究仍具有明显优势。本研究参与者均是儿童,排除了因成年人更可能有慢性炎症和动脉粥样硬化改变等可能会引起血脂异常的疾病,儿童可能参与影响血脂异常状态的共病较少,这使AIP与哮喘相关性这一结果变得更加可靠。

综上所述,本研究显示AIP与哮喘具有相关性;AIP对哮喘的预测价值高于TG,与HDL-C的预测价值相当。这些发现为国内血脂与哮喘的相关研究提供了资料,也为后续的研究提供了方向。

利益冲突声明

所有作者声明不存在利益冲突。

参 考 文 献

- 1. Boulet LP, Reddel HK, Bateman E, et al. The global initiative for asthma (GINA): 25 years later[J]. Eur Respir J, 2019, 54(2): 1900598. DOI: 10.1183/13993003.00598-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global Initiative for Asthma . Global strategy for asthma management and prevention (update 2021)[EB/OL]. [2022-03-29]. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/GINA-Main-Report-2021-V2-WMS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peng J, Huang Y. Meta-analysis of the association between asthma and serum levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol[J]. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 2017, 118(1): 61-65. DOI: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.09.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lu M, Wu B, Qiao R, et al. No associations between serum lipid levels or HOMA-IR and asthma in children and adolescents: a NHANES analysis[J]. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol, 2019, 11(3): 270-277. DOI: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2019.2018.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tang Z, Shen M, Xiao Y, et al. Association between atopic dermatitis, asthma, and serum lipids: a UK biobank based observational study and mendelian randomization analysis[J]. Front Med (Lausanne), 2022, 9: 810092. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2022.810092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dobiásová M, Frohlich J. The plasma parameter log (TG/HDL-C) as an atherogenic index: correlation with lipoprotein particle size and esterification rate in apoB-lipoprotein-depleted plasma [FER(HDL)][J]. Clin Biochem, 2001, 34(7): 583-588. DOI: 10.1016/s0009-9120(01)00263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ivanova EA, Myasoedova VA, Melnichenko AA, et al. Small dense low-density lipoprotein as biomarker for atherosclerotic diseases[J]. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2017, 2017: 1273042. DOI: 10.1155/2017/1273042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhu X, Yu L, Zhou H, et al. Atherogenic index of plasma is a novel and better biomarker associated with obesity: a population-based cross-sectional study in China[J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2018, 17(1): 37. DOI: 10.1186/s12944-018-0686-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kucera M, Oravec S, Hirnerova E, et al. Effect of atorvastatin on low-density lipoprotein subpopulations and comparison between indicators of plasma atherogenicity: a pilot study[J]. Angiology, 2014, 65(9): 794-799. DOI: 10.1177/0003319713507476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shen SW, Lu Y, Li F, et al. Atherogenic index of plasma is an effective index for estimating abdominal obesity[J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2018, 17(1): 11. DOI: 10.1186/s12944-018-0656-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. 洪建国. 我国儿童哮喘诊治现状和思考[J]. 四川大学学报(医学版), 2021, 52(5): 725-728. DOI: 10.12182/20210960201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. 王雪艳, 刘长山, 王峥, 等. 天津市城区0~14岁儿童支气管哮喘流行病学特点[J]. 中华实用儿科临床杂志, 2014, 29(4): 279-282. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-428X.2014.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bloom CI, Franklin C, Bush A, et al. Burden of preschool wheeze and progression to asthma in the UK: Population-based cohort 2007 to 2017[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2021, 147(5): 1949-1958. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. 温西苹, 李元霞. 儿童哮喘相关危险因素研究进展[J]. 新乡医学院学报, 2019, 36(11): 1092-1096. DOI: 10.7683/xxyxyxb.2019.11.021. 30955221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao L, Yang Y, Zang YR, et al. Risk factors for asthma in patients with allergic rhinitis in eastern China[J]. Am J Otolaryngol, 2022, 43(3): 103426. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yu J. Which subtype of atopic dermatitis progresses to asthma? A story about allergic march[J]. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res, 2022, 14(6): 585-586. DOI: 10.4168/aair.2022.14.6.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wilson K, Gebretsadik T, Adgent MA, et al. The association between duration of breastfeeding and childhood asthma outcomes[J]. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol, 2022, 129(2): 205-211. DOI: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xue MK, Dehaas E, Chaudhary N, et al. Breastfeeding and risk of childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. ERJ Open Res, 2021, 7(4): 00504-2021. DOI: 10.1183/23120541.00504-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barochia AV, Gordon EM, Kaler M, et al. High density lipoproteins and type 2 inflammatory biomarkers are negatively correlated in atopic asthmatics[J]. J Lipid Res, 2017, 58(8): 1713-1721. DOI: 10.1194/jlr.P077776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Su X, Ren Y, Li M, et al. Association between lipid profile and the prevalence of asthma: a meta-analysis and systemic review[J]. Curr Med Res Opin, 2018, 34(3): 423-433. DOI: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1384371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jiang T, Dai L, Li P, et al. Lipid metabolism and identification of biomarkers in asthma by lipidomic analysis[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids, 2021, 1866(2): 158853. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ikonen E. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2008, 9(2): 125-138. DOI: 10.1038/nrm2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fessler MB, Parks JS. Intracellular lipid flux and membrane microdomains as organizing principles in inflammatory cell signaling[J]. J Immunol, 2011, 187(4): 1529-1535. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Horejsi V, Hrdinka M. Membrane microdomains in immunoreceptor signaling[J]. FEBS Lett, 2014, 588(15): 2392-2397. DOI: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karr S. Epidemiology and management of hyperlipidemia[J]. Am J Manag Care, 2017, 23(9 Suppl): S139-S148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Emruzi Z, Babaheidarian P, Arshad M, et al. Immune modulatory effects of hypercholesterolemia: can atorvastatin convert the detrimental effect of hypercholesterolemia on the immune system?[J]. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol, 2019, 18(5): 554-566. DOI: 10.18502/ijaai.v18i5.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. The basic immunology of asthma[J]. Cell, 2021, 184(6): 1469-1485. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Verduci E, Banderali G, Di Profio E, et al. Effect of individual- versus collective-based nutritional-lifestyle intervention on the atherogenic index of plasma in children with obesity: a randomized trial[J]. Nutr Metab (Lond), 2021, 18(1): 11. DOI: 10.1186/s12986-020-00537-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cai G, Shi G, Xue S, et al. The atherogenic index of plasma is a strong and independent predictor for coronary artery disease in the Chinese Han population[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2017, 96(37): e8058. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. 李张曼玉, 李晓盼, 于莹, 等. 血浆致动脉硬化指数与冠状动脉病变严重程度的相关性研究[J]. 中国介入心脏病学杂志, 2019, 27(2): 107-110. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-8812.2019.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]