PURPOSE

Approximately 6 million people provide caregiving to people diagnosed with cancer. Many must remain employed to support their household and to have access to health insurance. It is unknown if caregiving for a spouse diagnosed with cancer is associated with greater financial and mental stress relative to providing care for a spouse with different conditions.

METHODS

Health and Retirement Study (2002-2020) data were used to compare employed caregivers, younger than age 65 years, caring for a spouse diagnosed with cancer (n = 103) and a matched control group caring for a spouse with other conditions (n = 515). We used logistic regression to examine a decrease in household income, increase in household debt, stopping work, and a new report of a mental health condition over a 4-year period, adjusting for socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, and health insurance status. Subanalyses stratified estimations by median household income.

RESULTS

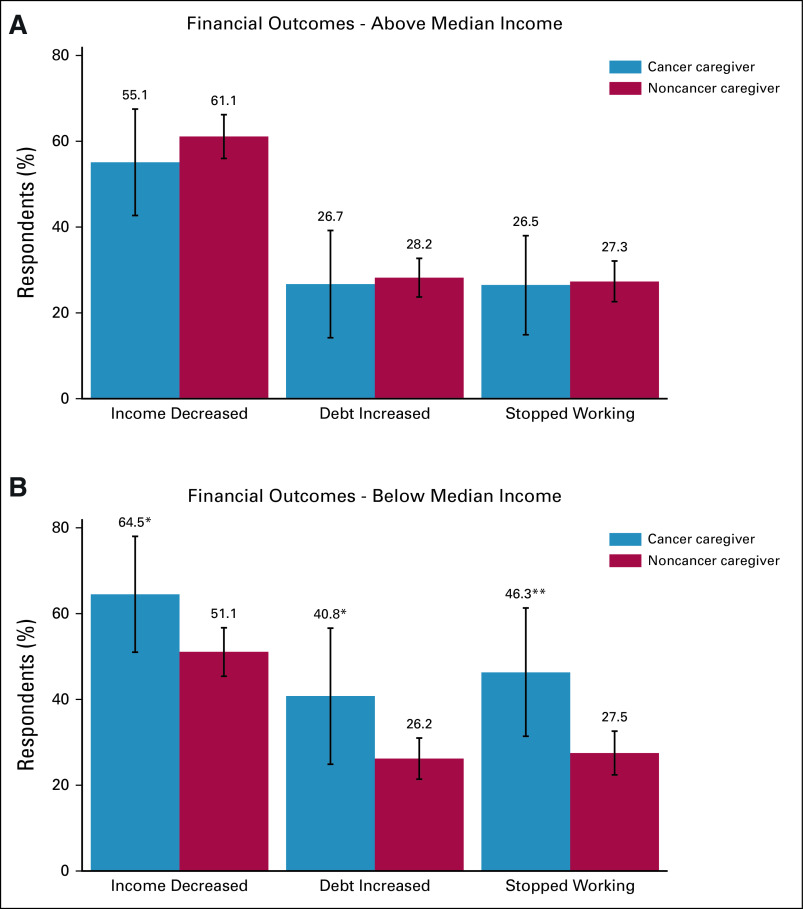

Around a third of cancer caregivers reported they stopped working (35%) and had an increase in household debt (30%). Cancer caregivers in households below the median household income were more likely to report decreased income (13.4 percentage points [pp]; P < .10), increased household debt (14.5 pp; P < .10), and stopping work (18.8 pp; P < .05) than similar noncancer caregivers. Mixed results were found for a change in mental health domains. The results were robust to multiple sensitivity analyses.

CONCLUSION

Cancer caregivers from low-income households were more likely to increase debt and incur work loss compared with noncancer caregivers in similar households. Policies such as paid sick leave and family leave are needed for this strained and important population who have financial and employment responsibilities in addition to caregiving.

INTRODUCTION

With 53 million adults serving as unpaid caregivers in the United States, the importance of examining the challenges caregivers face is essential.1 Caregivers of people diagnosed with cancer, estimated to be more than 6 million,2 have additional economic and well-being risks relative to caregivers of other adult patients.3 Caregivers of people diagnosed with cancer often assist with activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and medical tasks at greater frequency than noncancer caregivers.4 They also spend more time per week caregiving—about 32.9 hours per week4—and half of them work an average of 35 hours per week doing paid work in addition to their caregiving responsibilities.5

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Do employed cancer caregivers experience greater financial and mental health strain than similar caregivers of other conditions?

Knowledge Generated

In this cohort study, employed cancer caregivers in households below an annual household income of $75,000 US dollars were more likely to see a decrease in their annual income, to report increased household debt, and to report stopping work than the control group. There were mixed results for new reports of mental health conditions.

Relevance (S.B. Wheeler)

This work illustrates the higher financial strain among caregivers of people with cancer compared to caregivers of people with other conditions, contributing to growing evidence of the considerable economic ripple effects of cancer beyond those diagnosed.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor Stephanie B. Wheeler, PhD, MPH.

Caregivers for adults diagnosed with cancer also report mental health declines because of the patient's disease progression and expected mortality.6 High levels of emotional stress are reported by half of cancer caregivers, and 43% need help managing emotional and physical stress.5 Many caregivers of people diagnosed with cancer feel underprepared, overwhelmed, and that they lack support for the role they are undertaking.7

Employment introduces additional complexities into the caregiving experience. Caregivers may continue to work to preserve household income, provide health insurance for themselves and their spouses with cancer, and sustain their own career trajectory,8 all of which may be especially important if their loved one has a high probability of death or disability. Caregivers' employment for patients undergoing allogenic hematopoietic stem-cell transplant, an intensive inpatient treatment, reported reduced employment (45%), and among caregivers who reduced their work hours, higher levels of anxiety and depression were also reported.9

It is well established that the cost of cancer is outpacing that of other diseases, making copays and out-of-pocket expenses a financial hardship and an additional incentive to maintain employment and earned income.8 Like patients diagnosed with cancer, their caregivers also experience trouble paying medical bills and worry and distress about making payments.10,11 Employed caregivers for people diagnosed with cancer report financial strain at higher rates than employed noncancer caregivers.12 Financial concerns may lead to poor quality of life and life-altering decisions that remain after the patient is deceased, such as savings or retirement account withdrawals and home sale or refinancing.

We investigate whether employed caregivers caring for a spouse diagnosed with cancer experience greater economic and mental stress relative to similar caregivers caring for a spouse with conditions other than cancer. This study is relevant, given the growing population of cancer survivors coupled with the high cost of cancer care and dependency on employment-based health insurance to provide a financial shield against these costs. Employment also provides a distraction from caregiving responsibilities, but balancing work demands with caregiving is nonetheless challenging. Investigation into the issues we raise can inform policies related to paid family medical leave, health insurance sources outside employment, and long-term services and supports.

METHODS

Participants and Analysis Sample

We use data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), from 2002 through 2020.13 The HRS surveys respondents age 51 years and older and their spouses every 2 years. Respondents who reported in one interview period, but not the prior period, that they helped their spouse with ADLs, IADLs, or managing money were identified as caregivers. Assistance with ADLs include helping with getting across a room, dressing, bathing, eating, getting in/out of bed, or using the toilet. IADLs include helping to prepare meals, shopping for groceries, making telephone calls, or taking medications. We excluded caregivers who were not caring for a spouse because these caregivers may not be financially committed to the same household. Caregivers with a spouse who responded yes to the question “Has a doctor told you that you have cancer or a malignant tumor, excluding minor skin cancer?” were considered cancer caregivers.

To examine the impact of caregiving longitudinally, we assessed outcomes over a 4-year period using two surveys, the interview before caregiving and the interview after the first report of caregiving, referred to as baseline and follow-up interviews, respectively. We excluded the interview that the caregiver first reported caregiving as a washout year to allow time to observe the longer-term impact of caregiving, allowing 4 years between the baseline and follow-up interviews; 6,925 caregivers were identified. Only married caregivers were included in the sample (excluded 423 caregivers). Caregivers with key variables missing such as employment and spousal cancer information were removed from the sample (n = 838). We excluded 2,718 caregivers who did not respond to the baseline or follow-up interview. The sample was further restricted to caregivers working at least 20 hours per week during the baseline interview (excluded 2,091 caregivers). Caregivers diagnosed with cancer were also excluded (n = 37). Last, we restricted the sample to those younger than 65 years at baseline to reduce the influence of Medicare insurance on employment decisions (excluded 258 caregivers) and excluded 14 caregivers whose spouse also reported caregiving. This yielded an unmatched sample of 546 caregivers.

To reduce potential bias when comparing the cancer caregiver sample to other caregivers, we used a 1:5 nearest-neighbor matching with replacement on the basis of Mahalanobis distance.14 We matched on baseline variables for age (36-55, 55-59, or 60 and older), census region (Northwest, Midwest, South, and West), education (college degree/higher or no college degree), race (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or non-Hispanic Other/unknown, and Hispanic), self-reported health status (fair/poor health versus good to excellent health), and annual household income above $75,000 US dollars (USD) at baseline, which was around the median household income for the full sample. We also matched on whether the caregiver had health insurance (employer sponsored, other plan, or no insurance) and the availability of retiree health insurance. Retiree health insurance may allow caregivers to leave the workforce earlier relative to those without such benefits.15 Standardized differences were balanced and below the threshold of 15% for all variables after matching. The final sample included 103 cancer caregivers and 515 matched controls (270 unique control respondents). Care recipients had heterogeneous health conditions; some had multiple comorbidities. The distinguishing characteristic was that one group had cancer and the other did not. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline (Appendix Fig A1 [online only]). The institutional review board at the University of Colorado approved study procedures and ruled the study as exempt.

Measures

The outcomes of interest were financial and mental health outcomes among caregivers employed at baseline. Financial outcomes were any decrease in annual household income, any increase in household debt, and if the caregiver stopped working. Mental health outcomes were measured at the individual level using indicators from the Center for Epidemiological Studies 8—Depression (CES-D).16 For each of the CES-D indicators, we identified a new report of poor mental health after caregiving. Variables were equal to one if the respondent reported no in the baseline interview and yes in the follow-up interview.

Statistical Analysis

We descriptively assessed financial and mental health outcomes after the baseline interview (4 years later or 2 years after a new report of spousal caregiving). Statistically significant differences were determined by chi-square and t-tests. We estimated logistic regression models as functions of cancer caregiving, exogenous variables reported in Table 1, indicators for the survey year, and unobserved influences. To examine if there were differential impacts because of socioeconomic status, we stratified models by median annual household income ($75,000 USD or higher) at baseline. Assessments of financial indicators were stratified by sex since men and women have different labor market attachments and work in different types of jobs.17-19 We estimated and graphed the predicted probabilities using Stata's margins command. Standard errors were estimated using robust standard errors. All models were estimated using Stata (version 17.0). We conducted sensitivity analyses restricting the sample to caregivers who helped their spouse with ADLs and IADLs only, ADLs only, and caregivers younger than 63 years; we also specified a decrease in annual household income and increase in household debt as a 5% change.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of Cancer Caregivers and the Equivalent Noncancer, Matched Control Group, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 reports baseline descriptive statistics for employed cancer and noncancer caregivers. The cancer and matched control samples were well balanced. There were few statistically significant differences between characteristics of cancer caregivers compared with the control group (P < .10). Most cancer caregivers were female (59.2%), 55 years and older (69.0%), non-Hispanic White (66.0%), and had health insurance through an employer (61.2%). Approximately 44% lived in the southern region of the United States and nearly 17% reported their health status as poor or fair. Around a quarter (26.2%) had a college degree and 56% had annual household incomes above $75,000 USD. Around 28% had access to retiree health insurance if they stopped working. Matched controls reported similar characteristics, although a higher percentage of cancer caregivers reported feeling unhappy at baseline compared with noncancer caregivers (19.4% v 13.2%).

Financial and Mental Health Impact

Table 2 reports unadjusted changes in financial and mental health outcomes from the baseline interview and the follow-up interview. Over a third of cancer caregivers reported they stopped working relative to a quarter of noncancer caregivers (35.0% v 26.4%; P < .10). Other caregivers were more likely to report they did not enjoy life relative to cancer caregivers (11.8% v 5.0%; P < .05). Otherwise, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups. After adjusting for covariates using logistic regression (Fig 1), for all three measures, income decreased, debt increased, and stopping work, a greater percentage of cancer caregivers report an adverse outcome, but none were statistically significant.

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted Change in Financial and Mental Health Outcomes After Caregiving, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020

FIG 1.

Adjusted change in financial outcomes between cancer and noncancer caregivers, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020. Predicted probabilities were estimated using adjusted logistic regression models with robust standard errors. Models estimate whether respondents' income decreased, debt increased, or stopped working after caregiving. Models were adjusted using variables listed in Table 1. Statistical significance is above P < .10 unless noted. Full results are presented in Appendix Table A1.

Caregivers in households below the median annual household income of $75,000 USD at baseline bore the brunt of financial consequences after cancer caregiving (Fig 2). These households were 13.4 percentage points (pp) more likely to report a decrease in income (P < .10), 14.5 pp more likely to report increase household debt (P < .10), and 18.8 pp more likely to report stopping work than similar households caring spouses with a condition other than cancer (P < .05). Caregivers in households above the median annual income of $75,000 USD experienced fewer adverse financial outcomes relative to noncancer caregivers in similar households. Almost half of cancer caregivers who lived in lower-income households stopped working compared with only a quarter of higher-income caregivers. Cancer caregivers in lower-income households were also more likely to report an increase in debt and decrease in income compared with those who resided in a household above median income.

FIG 2.

Adjusted change in financial outcomes between cancer and noncancer caregivers stratified by income, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020: (A) above median income and (B) below median income. Predicted probabilities were estimated using adjusted logistic regression models with robust standard errors. Models estimate whether respondents' income decreased, debt increased, or stopped working after caregiving and stratified by baseline household median annual income of $75,000 US dollars. Models were adjusted using variables listed in Table 1. These variables were also controlled in the estimation. Statistical significance is noted as *P < .10 and **P < 5. Full results are presented in Appendix Table A1.

When we stratify by sex (Appendix Fig A2 [online only]), men and women had similar financial outcomes, although men who cared for a patient diagnosed with cancer were 16.1 pp more likely report they stopped working than men who were noncancer caregivers (P < .05). When we stratified by race, more non-White respondents were likely to have a decrease in income, but similar percentages were observed for the other measures. Non-White cancer caregivers were 19.6 pp more likely to report decreased income relative to non-White, noncancer caregivers (P < .05, Appendix Fig A3 [online only]). Complete regression marginal effects are reported in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

A new report of poor mental health outcomes is displayed in Figures 3 and 4. Differences were not statistically significant between cancer and noncancer caregivers with one exception; noncancer caregivers were more likely to report that they did not enjoy life relative to cancer caregivers (P < .05; Fig 3). However, the difference did not persist when stratifying by median household income (Fig 4). For lower-income households, cancer caregivers had higher rates of some poor mental health outcomes (feeling lonely and sad), but had lower rates of feeling unmotivated and unhappy, although these differences were not statistically significant. Similarly, cancer caregivers in households below the annual median income were also more likely to report worsening mental health than caregivers in households with above median income (Fig 4). Eleven percent of cancer caregivers below median income reported they were newly depressed compared with only 5.3% of those above median income. In supplemental analyses (Appendix Fig A4 [online only]), there is suggestive evidence that non-White cancer caregivers may be more likely to report loneliness than non-White caregivers of other conditions, but the sample size was small. Regression marginal effects for mental health outcomes are reported in Appendix Table A2 (online only).

FIG 3.

Adjusted change in mental health outcomes between cancer and noncancer caregivers, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020. Predicted probabilities were estimated using adjusted logistic regression models with robust standard errors. Models were adjusted using variables in Table 1. Models estimate whether respondents newly reported yes to mental health indicators after caregiving. Statistical significance is noted as **P < 5. Full results are presented in Appendix Table A2.

FIG 4.

Unadjusted change in mental health outcomes between cancer and noncancer caregivers stratified by median household income, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020: (A) above median income and (B) below median income. Predicted probabilities were estimated using logistic regression models with robust standard errors. These models were unadjusted because of small sample sizes. The model for does not enjoy life in the above median income stratification was excluded because no cancer caregivers reported they did not enjoy life. Noncancer caregivers were matched to cancer caregivers using the variables listed in Table 1. Models estimate whether respondents newly reported yes to mental health indicators following caregiving. Statistical significance in all models is above P < .10. Full results are presented in Appendix Table A2.

Sensitivity Analysis

Appendix Table A3 (columns 2-5 [online only]) reports sensitivity analyses where we restrict the sample to caregivers who provide only ADL and IADL support, only ADL support, caregivers younger than 63 years, and where we specify the financial outcomes as a 5% change or more. Estimates were generally robust, and in some cases became stronger, despite the reduction in sample size. Cancer caregivers were 10 pp more likely to report increased debt when the sample was restricted to those who provided ADL support (P < .10). Caregivers in households below the median income were 17.4 (P < .10) and 18.3 (P < .05) pp more likely to report increased debt and lost work, respectively, when the sample was restricted to ADL and IADL support. Similarly, when the sample was restricted to those age 63 years and younger, cancer caregivers were 14 pp more likely to report decreased income (P < .10) and 20 pp more likely to report losing their job (P < .05). The findings were robust when we specified the outcomes as a 5% change.

DISCUSSION

This longitudinal cohort study of employed cancer caregivers compared with a matched control group of caregivers of people with other conditions offers several insights for policy. After adjustment for socioeconomic and demographic variables, the impact of caregiving on financial and mental health outcomes for cancer caregivers was similar to caregivers with other conditions. When stratifying by median household income, cancer caregivers in lower-income households experienced increased financial strain after caregiving. However, cancer caregivers in lower-income households did not have significantly different mental health outcomes relative to other caregivers. Although our objective was to report differences between cancer and noncancer caregivers, we note that in unadjusted analyses, approximately 60% of all caregivers reported that their income decreased; 30% and 28% of cancer and noncancer caregivers, respectively, report that their household debt increased; and 35% and 26% of cancer and noncancer caregivers, respectively, report that they stopped working. This highlights the enormous and long-term financial impact of caregiving, regardless of condition. We note that these differences were persistent and that caregivers did not return to their precaregiving financial situations, which potentially sets them up for long-term financial strain.

The probability of increasing debt was especially high in low-income households where nearly 65% reported decreased income and 41% reported additional debt. This estimate is nearly twice that of the 25% experiencing financial hardship reported in prior published research.20 When we restrict the sample to caregivers providing assistance with ADLs, the results become stronger for caregivers in households below the median income. Spending on cancer drugs in the United States reached $57 billion USD in 2018,21 and out-of-pocket medical costs for cancer survivors exceeded out-of-pocket costs for the treatment of other conditions.22 Therefore, it is unsurprising that households with lower incomes would have difficulty paying for care. The Federal Reserve reports that in 2018, approximately 40% of US households cannot afford an unexpected expense of $400 USD; many reported that they would increase their debt to cover unexpected expenses.23

Almost half of the caregivers (46.3%) in low-income households also reported that they stopped working. Reasons why caregivers stopped working are unknown, but the absence of paid sick leave may have played a role. In the United States, paid sick leave is uncommon for low-wage workers.24 These workers may have been unable to sustain work while providing care to a spouse with cancer. The absence of paid sick leave is associated with fewer preventive health care utilization25 and more emergency department use.26 The lack of preventive care coupled with the stressors of caregiving may have resulted in health declines for caregivers who subsequently stopped working. It is also possible that the spouse's health declined and required more of the caregiver's time. Regardless of the reason, a caregiver's loss of paid work imperils a low-income household that is already financially struggling.

Mental health declines were observed for all caregivers. However, cancer caregivers in low-income households were more likely to report a new mental health condition. Although these differences were not generally statistically significant, they are nonetheless important as they demonstrate mental health consequences of caregiving, especially for low-income households with few supports. A feeling of loneliness highlights the isolation felt by these caregivers.

The study has limitations. First, the sample was restricted to spousal caregivers who reported at least three interviews (baseline interview, new caregiving interview, and follow-up interview). Attrition between the interviews, particularly in the cancer sample, may be attributable to the sickest caregivers dropping out of the HRS and thus biasing our results toward the null if those who remain are healthier than those who dropped out. Second, cancer site and stage are unavailable in the HRS public use data; the complexity of caregiving responsibilities associated with later-stage disease and treatment may influence the impact of caregiving. However, the impact of caregiving was largely robust when restricting the sample to caregivers who provide help with at least one ADL (Appendix Table A3). Third, the availability of paid sick leave influences decisions to work, household income, and other financial indicators. Although these variables are in the HRS, over 50% of observations are missing this information. Last, the absence of paid sick leave and health insurance outside of employers is overwhelmingly specific to the United States, limiting the ability to generalize our findings to other countries.

In conclusion, this longitudinal study reports that the increase in medical debt for cancer caregivers is concentrated among households that earn less than $75,000 USD per year. We note that all caregivers experience a decline in financial stability but that caregivers of a spouse with cancer appear to suffer greater consequences that are sustained over time. Caregivers do not return to their precaregiving financial status, suggesting that the impacts are long-lasting and for lower-income families, financial consequences may worsen. Policies such as paid sick leave, health insurance coverage, and other services to address housing and food insecurity may be needed to support these caregivers. Without supports for low-income working families who are struggling to care for a loved one with cancer, disparities may widen.

APPENDIX

FIG A1.

Sample inclusion flow diagram, cancer and noncancer caregivers, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020. Matched sample represents 1:5 matching with replacement.

FIG A2.

Economic impact of cancer caregiving compared with noncancer caregiving stratified by sex, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020: (A) women and (B) men. Predicted probabilities were estimated using adjusted logistic regression models with robust standard errors. Models estimate whether respondents' income decreased, debt increased, or stopped working after caregiving. Noncancer caregivers were matched to cancer caregivers using the variables listed in Table 1. Statistical significance is noted as **P < .05. Coefficients are presented in Appendix Table A1.

FIG A3.

Financial impact of cancer caregiving compared with noncancer caregiving stratified by race, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020: (A) White and (B) non-White. Predicted probabilities were estimated using adjusted logistic regression models with robust standard errors. Models estimate whether respondents' income decreased, debt increased, or stopped working after caregiving and stratified by White and non-White respondents. Noncancer caregivers were matched to cancer caregivers using the variables listed in Table 1. Statistical significance is noted as **P < .05. Coefficients are presented in Appendix Table A1.

FIG A4.

Mental health impact of cancer caregiving compared to noncancer caregiving stratified by race, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020: (A) White and (B) non-White. Predicted probabilities were estimated using logistic regression models with robust standard errors. These models were unadjusted because of small sample sizes. Noncancer caregivers were matched to cancer caregivers using the variables listed in Table 1. Models estimate whether respondents newly reported yes to mental health indicators after caregiving. Statistical significance is noted as **P < .05. Coefficients are presented in Appendix Table A2.

TABLE A1.

Financial Impact of Cancer Caregiving Compared With Noncancer Caregiving, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020

TABLE A2.

Mental Health Impact of Cancer Caregiving Compared With Noncancer Caregiving, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020

TABLE A3.

Sensitivity Analyses—Financial Impact, Health and Retirement Study, 2002-2020

SUPPORT

Supported by National Cancer Institute grants Emotional and financial needs of employed caregivers eCare: A virtual stress management intervention for employed caregivers of solid tumor cancer patients (R01CA231387, C.J.B., Principal Investigator) and the University of Colorado Cancer Center Core Grant No. (P30CA046934).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Administrative support: Cathy J. Bradley, Sara Kitchen

Data analysis and interpretation: Cathy J. Bradley, Kelsey M. Owsley

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Working, Low Income, and Cancer Caregiving: Financial and Mental Health Impacts

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Applebaum AJ: There is nothing informal about caregiving. Palliat Support Care 20:621-622, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Applebaum AJ: Care for the cancer caregiver. https://ascopost.com/issues/september-25-2018/care-for-the-cancer-caregiver/

- 3.Sun V, Raz DJ, Kim JY: Caring for the informal cancer caregiver. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 13:238-242, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Alliance for Caregiving : Cancer caregiving in the U.S. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CancerCaregivingReport_FINAL_June-17-2016.pdf

- 5.NIH National Cancer Institute : Informal caregivers in cancer: Roles, burden, and support (PDQ®)—Health professional version. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/family-friends/family-caregivers-hp-pdq [PubMed]

- 6.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. : Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer 122:1987-1995, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, et al. : The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs 28:236-245, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley CJ: Economic burden associated with cancer caregiving. Semin Oncol Nurs 35:333-336, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Natvig C, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Laudenslager ML, et al. : Association between employment status change and depression and anxiety in allogeneic stem cell transplant caregivers. J Cancer Surviv 16:1090-1095, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yabroff KR, Bradley C, Shih Y-CT: Understanding financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: Strategies for prevention and mitigation. J Clin Oncol 38:292-301, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadigh G, Switchenko J, Weaver KE, et al. : Correlates of financial toxicity in adult cancer patients and their informal caregivers. Support Care Cancer 30:217-225, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longacre ML, Weber-Raley L, Kent EE: Cancer caregiving while employed: Caregiving roles, employment adjustments, employer assistance, and preferences for support. J Cancer Educ 36:920-932, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Health and Retirement Study, Public Survey Data, 1992-2018. https://hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/data-products/public-survey-data?_ga=2.185838432.876153474.1679678209-573202515.1679678209

- 14.Rubin DB: Bias reduction using mahalanobis-metric matching. Biometrics 36:293-298, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley CJ, Owsley KM: Retirement behavior of cancer survivors: Role of health insurance. J Cancer Surviv 10.1007/s11764-022-01248-2 [epub ahead of print on September 5, 2022] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychological Association : Center for epidemiological studies-depression. https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/depression-scale

- 17.Currie J, Madrian BC: Health, health insurance and the labor market. Handbook in Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds): Handbook of Labor Economics. Amsterdam, the Netherlands, Elsevier‐North Holland, 1999, pp 3309-3416 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marianne B: New perspectives on gender, in Card D, Ashenfelter O (eds): Handbook of Labor Economics. Amsterdam, the Netherlands, Elsevier-North Holland, 2011, pp 1543-1590 [Google Scholar]

- 19.List JA, Rasul I: Field experiments in labor economics, in Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds): Handbook of Labor Economics. Amsterdam, the Netherlands, Elsevier-North Holland, 2011, pp 103-228 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han X, Zhao J, Zheng Z, et al. : Medical financial hardship intensity and financial sacrifice associated with cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 29:308-317, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The IQVIA Institute : Global Oncology Trends 2019. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/global-oncology-trends-2019 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekwueme DU, Zhao J, Rim SH, et al. : Annual out-of-pocket expenditures and financial hardship among cancer survivors aged 18–64 years—United States, 2011–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:494-499, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System : Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2018—May 2019. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2018-dealing-with-unexpected-expenses.htm [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claxton G, Levitt L: Paid Sick Leave Is Much Less Common for Lower-Wage Workers in Private Industry. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/paid-sick-leave-is-much-less-common-for-lower-wage-workers-in-private-industry/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamsal R, Napit K, Rosen AB, et al. : Paid sick leave and healthcare utilization in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 60:856-865, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Y, Johnston KJ, Yu H, et al. : State mandatory paid sick leave associated with a decline in emergency department use in the US, 2011–19. Health Aff 41:1169-1175, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]