PURPOSE

To characterize racial and ethnic disparities and trends in opioid access and urine drug screening (UDS) among patients dying of cancer, and to explore potential mechanisms.

METHODS

Among 318,549 non-Hispanic White (White), Black, and Hispanic Medicare decedents older than 65 years with poor-prognosis cancers, we examined 2007-2019 trends in opioid prescription fills and potency (morphine milligram equivalents [MMEs] per day [MMEDs]) near the end of life (EOL), defined as 30 days before death or hospice enrollment. We estimated the effects of race and ethnicity on opioid access, controlling for demographic and clinical factors. Models were further adjusted for socioeconomic factors including dual-eligibility status, community-level deprivation, and rurality. We similarly explored disparities in UDS.

RESULTS

Between 2007 and 2019, White, Black, and Hispanic decedents experienced steady declines in EOL opioid access and rapid expansion of UDS. Compared with White patients, Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to receive any opioid (Black, –4.3 percentage points, 95% CI, –4.8 to –3.6; Hispanic, –3.6 percentage points, 95% CI, –4.4 to –2.9) and long-acting opioids (Black, –3.1 percentage points, 95% CI, –3.6 to –2.8; Hispanic, –2.2 percentage points, 95% CI, –2.7 to –1.7). They also received lower daily doses (Black, –10.5 MMED, 95% CI, –12.8 to –8.2; Hispanic, –9.1 MMED, 95% CI, –12.1 to –6.1) and lower total doses (Black, –210 MMEs, 95% CI, –293 to –207; Hispanic, –179 MMEs, 95% CI, –217 to –142); Black patients were also more likely to undergo UDS (0.5 percentage points; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.8). Disparities in EOL opioid access and UDS disproportionately affected Black men. Adjustment for socioeconomic factors did not attenuate the EOL opioid access disparities.

CONCLUSION

There are substantial and persistent racial and ethnic inequities in opioid access among older patients dying of cancer, which are not mediated by socioeconomic variables.

BACKGROUND

Opioids are a cornerstone of managing cancer pain, particularly for patients with advanced malignancies.1 Yet, the ongoing US epidemic of opioid misuse has prompted numerous regulations aimed at curbing opioid prescribing and mitigating their risks.2-5 Although not the intended targets, patients with cancer have experienced substantial declines in opioid access—even at the end of life (EOL).6,7 We recently reported that between 2007 and 2017, the number and dose of opioid prescriptions filled by patients with cancer near EOL declined by 34% and 38%, respectively, while pain-related emergency department visits rose by 50%.8

CONTEXT

Key Objective

To quantify racial and ethnic disparities in opioid access and urine drug screening among patients with poor-prognosis cancers near the end of life, and to explore potential mechanisms.

Knowledge Generated

Among 318,549 Medicare beneficiaries with poor-prognosis cancers who died between 2007 and 2019, Black and Hispanic patients were substantially less likely to receive any opioids or long-acting opioids and received lower doses than White patients, while Black compared with White patients were also more likely to undergo urine drug screening. These inequities disproportionately affected Black men, and were not mitigated by adjusting for measures of poverty, community-level deprivation, or rurality.

Relevance (S.B. Wheeler)

-

This epidemiologic analysis demonstrates that there are ongoing racial and ethnic inequities in opioid access among Medicare-insured patients dying of cancer not explained by clinical or contextual factors, potentially representing prejudice and structural racism within the health care system that must be addressed.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor Stephanie B. Wheeler, PhD, MPH.

An important unanswered question is how these declines have affected patients of color, who are known to receive fewer opioids than White patients across multiple conditions.9-14 Specific to cancer, studies have shown Black patients to be twice as likely as White patients to have their pain undertreated,15 and 25% less likely to receive opioids following definitive cancer treatment.16 Importantly, these and most studies of cancer pain management inequities15-19 predate the 2012 peak in opioid prescribing and subsequent intensification of opioid regulations and stigma. Moreover, few, if any, have focused on advanced cancer populations—for whom opioids are widely agreed to be appropriate treatment for moderate-to-severe pain,20,21 unlike treatment guidelines for chronic noncancer pain. Evaluating and ensuring racial and ethnic parity in opioid access among EOL cancer populations is therefore of utmost importance.

The opioid crisis has also prompted numerous efforts to mitigate risk of misuse and overdose. Notably, the Centers for Disease Control recommends that all patients on opioids for chronic noncancer pain undergo baseline and annual urine drug screening (UDS).4,22 Yet, Black compared with White individuals are substantially more likely to undergo UDS and to have their opioids discontinued in response.23-26 As UDS is increasingly incorporated into cancer care,20,27,28 guidelines regarding triggers or the optimal frequency for testing are lacking. This could amplify racial biases in UDS, yet little is known about the prevalence or inequities in UDS among cancer populations.

Here, we investigate recent trends and racial and ethnic inequities in opioid access and UDS among patients with poor-prognosis cancers near EOL. Recognizing that health care inequities are often a function of societal structures that have historically deprived people of color from privilege and resources,29-31 we also explore the contributions of socioeconomic variables to disparities in opioid access and UDS near EOL.

METHODS

Data/Study Population

Using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) administrative data for a 20% random sample of beneficiaries, we identified decedents with poor-prognosis cancers who died between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2019, years spanning the initial recognition of the opioid crisis,32,33 ensuing legislative reforms,2,34 and prescribing declines.35 We focused on decedents age ≥ 66 years continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare Parts A, B, and D ≥ 12 months before death. To identify patients who likely died from cancer, decedents had to have ≥ 1 inpatient or ≥ 2 outpatient claims with an International Classification of Diseases Ninth (ICD-9) or Tenth (ICD-10) Revision code for a poor-prognosis cancer,8 including the 10 most common causes of cancer death reported by the American Cancer Society36 and National Vital Statistics System,37 supplemented by ICD-9/10 codes for lethal rare cancers (eg, cholangiocarcinoma, acute myeloid leukemia). Concurrent nonlymphatic metastatic codes were required for solid tumors frequently diagnosed at early stages (eg, breast, prostate, and colorectal). We restricted this analysis to decedents identified as non-Hispanic White (hereafter, White), non-Hispanic Black (Black), or Hispanic using the Research Triangle Institute race and ethnicity indicator.38 The Harvard Medical School institutional review board approved the study.

Outcomes

We used National Drug Codes39 to identify all Medicare Part D claims for outpatient opioid prescriptions, excluding addiction treatments, cough suppressants, and parenteral opioids. We focused on prescriptions filled ≤ 30 days before death or hospice enrollment (hereafter referred to as near EOL), excluding the hospice period when the hospice benefit covers symptom-relieving medications.8 We examined long-acting opioids separately because there are often more restrictions for prescriptions and insurance coverage. We determined decedents' mean daily opioid dose in morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) per day (MMEDs) by multiplying the total dose of each prescription filled near EOL by standard conversion factors,39 summing all prescriptions, and averaging over 30 days. We also calculated the total opioid dose filled per decedent near EOL, averaged across opioid recipients and nonrecipients. To assess opioid risk reduction strategies, we identified codes for presumptive (i.e., screening) urine drug tests (H0003, H0049, 80100-80104, 80300-80307, G0434, G0477, G0478, and G0477-G0479) among opioid recipients.22 Because of relatively low rates of UDS, we expanded this time horizon to 180 days before death or hospice.

Patient Demographics

We identified age at death, documented sex, census region, and 11 Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse diagnoses possibly associated with receipt of an opioid prescription (Table 1).

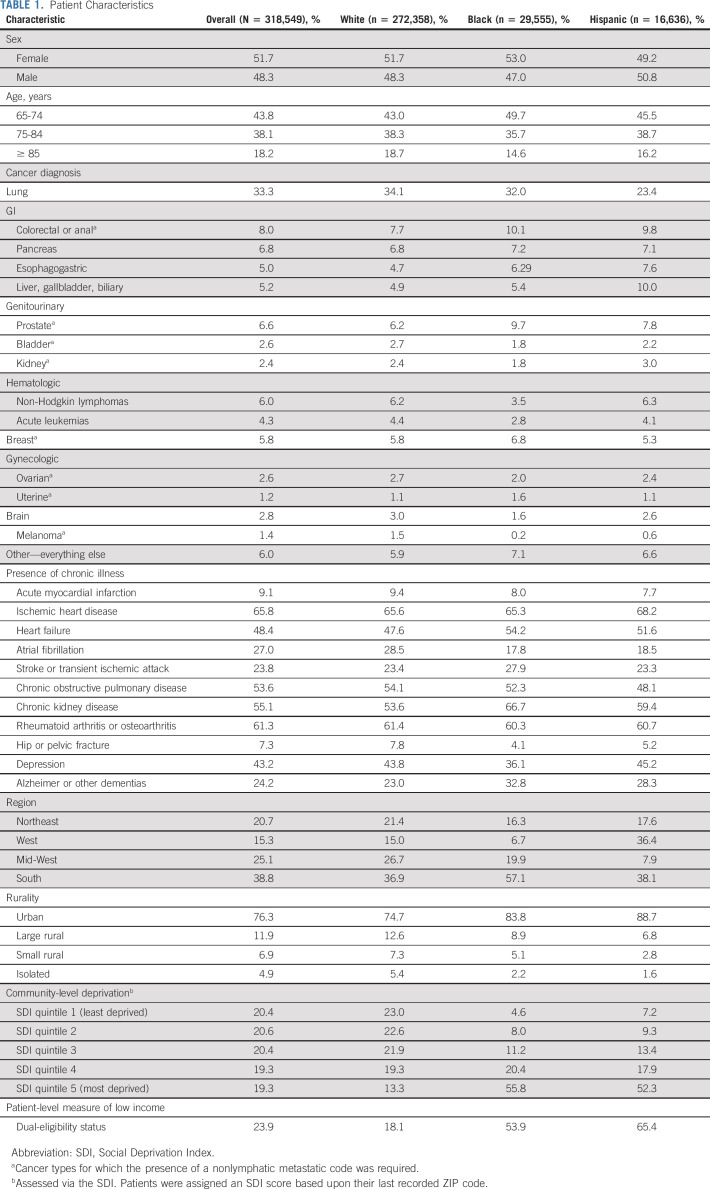

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

Socioeconomic Factors

We assessed dual-eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid as an indicator of low income.40 Older Medicare beneficiaries may qualify for Medicaid based upon state-specific thresholds for low income and resources—typically < 100% of the federal poverty level and three times the Supplemental Security Income resource limit, respectively.41 We measured community-level socioeconomic deprivation by assigning each decedent a Social Deprivation Index (SDI) score based upon the ZIP code tabulation area corresponding to their five-digit ZIP code. The SDI is a composite measure of seven items from the American Community Survey (including the percentage of adults living in poverty; with < 12 years education; unemployed; living in rented or crowded housing, single-parent households, or without a car), weighted and scaled from 0 to 100 and categorized into quintiles, with higher scores indicating worse deprivation.42 Higher SDI scores are associated with worse health outcomes than lower scores across a range of measures.43-46 Recognizing that the opioid crisis has affected many rural communities more severely than some urban communities47,48 and patients of color may face added barriers to accessing health care in rural communities49—we used Rural Urban Commuting Area codes50 for decedents' ZIP codes, categorized as urban and rural (including large rural, small rural, and isolated rural areas).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics characterized annual trends among White, Black, and Hispanic decedents in the proportion filling ≥ 1 opioid prescription near EOL (overall and for long-acting opioids), opioid potency among decedents filling ≥ 1 prescription, the average total dose of opioids filled per decedent near EOL (averaged across those who did and did not fill an opioid), and the proportion of opioid users with ≥ 1 screening UDS. We fit linear probability models to examine associations between race and ethnicity and each outcome, controlling for demographic and clinical factors, including age, documented sex, cancer type, comorbidities, census region, and year. Consistent with the framework of health care disparities proposed by the Institute of Medicine,51 these base models provided our main effect estimates for race and ethnicity and were not adjusted for socioeconomic factors that could potentially mediate unequal treatment. In additional models, we adjusted for dual-eligibility, SDI quintile, and rural/urban residence. To more fully explore race- and ethnicity-based disparities, separate models included interactions for race and ethnicity by documented sex, dual-eligibility, and rural/urban residence and we calculated adjusted differences in absolute rates of each outcome among White, Black, and Hispanic decedents with each of these characteristics. We present point estimates and 95% CIs; analyses were conducted using STATA software, version 17.0, and SAS software, version 9.4.

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

We studied 272,358 White, 29,555 Black, and 16,636 Hispanic patients with poor-prognosis cancers who died between 2007 and 2019 (Table 1). Decedents' mean age was 77.6 years. Baseline characteristics differed by patient race and ethnicity in expected ways. Compared with White patients, Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to be dually eligible and live in the South, urban areas, and the most deprived SDI quintile.

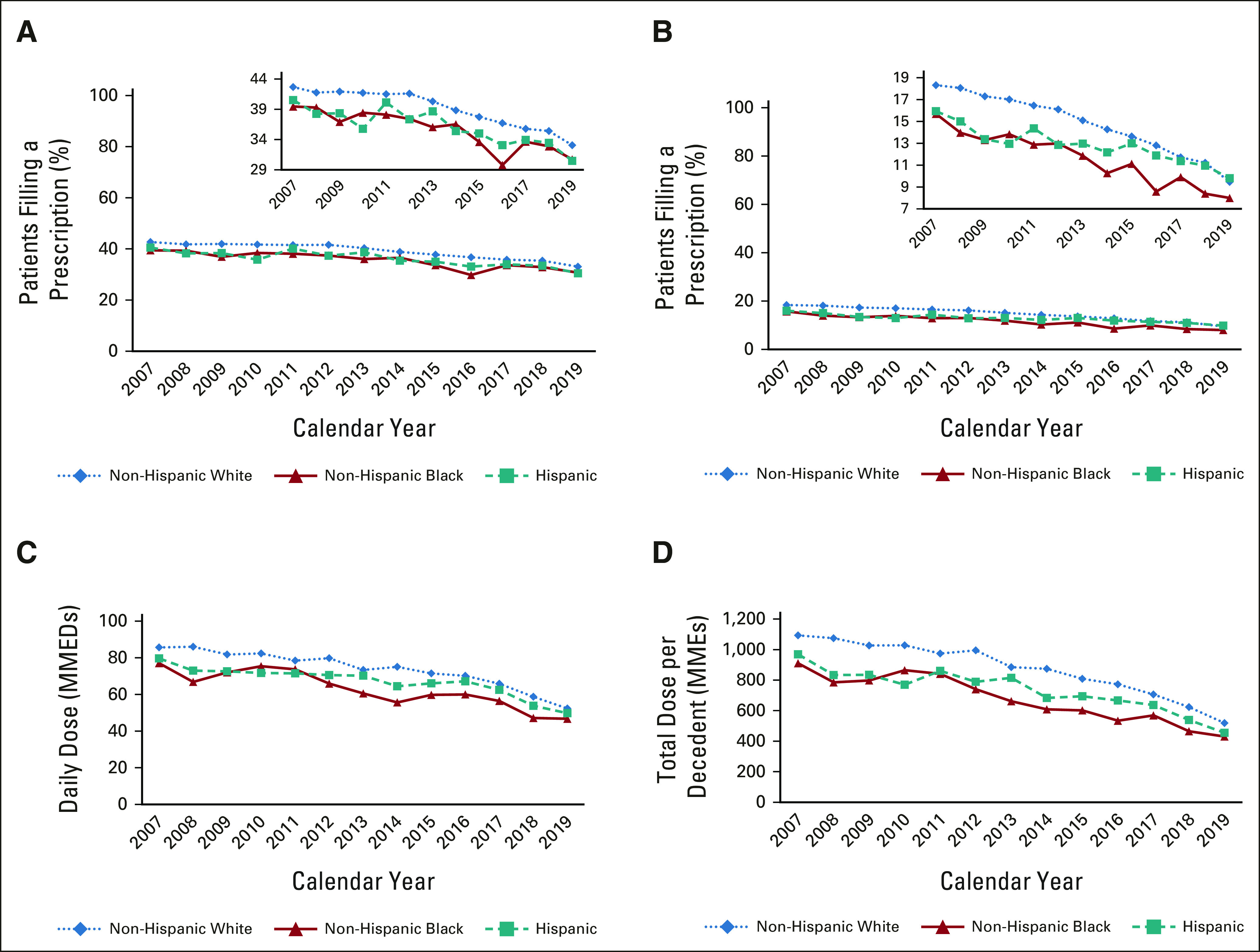

Temporal Trends in EOL Opioid Utilization and Urine Drug Screens

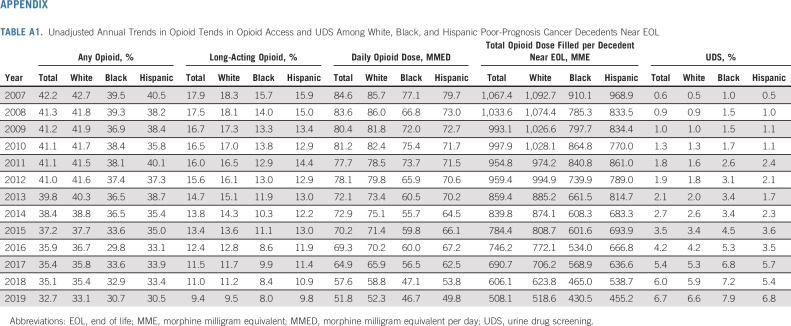

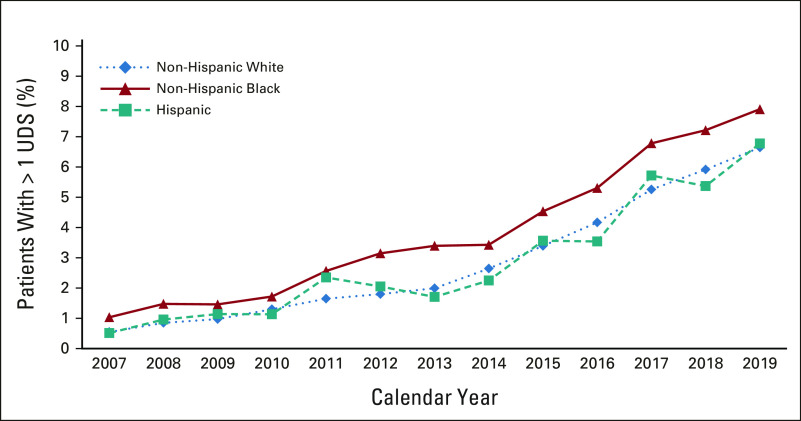

From 2007 to 2019, we observed steady declines in EOL opioid access overall, and among White, Black, and Hispanic patients (Fig 1; Appendix Table A1, online only). Overall, the proportion of patients near EOL receiving any opioid or long-acting opioids decreased from 42.2% to 32.7%, and 17.9% to 9.4%, respectively. Among those filling ≥ 1 opioid, the mean daily dose fell from 84.6 to 51.8 MMED, and the total dose of opioids filled per decedent (averaged across those who did and did not fill an opioid) fell from 1,067 to 508 MME. Black and Hispanic decedents received fewer opioids at lower doses than White decedents throughout the study, except in 2019, when long-acting opioid access equalized between Hispanic and White patients. The proportion of patients undergoing UDS increased from 0.6% to 6.7% in the 180 days before death or hospice; Black decedents were tested more often than White or Hispanic decedents (Appendix Table A1, Appendix Fig A1, online only).

FIG 1.

Annual trends in opioid access and UDS among White, Black, and Hispanic poor-prognosis cancer decedents near EOL. Unadjusted annual trends in opioid access among patients with poor-prognosis cancers near EOL, by race and ethnicity: (A) the proportion of decedents with poor-prognosis cancers filling any opioid near EOL, by race and ethnicity; (B) the proportion filling a long-acting opioid near EOL; (C) mean opioid dose in MMEDs among patients filling at least one opioid; and (D) the mean total dose of opioids (in morphine milligram equivalents) filled by patients with poor-prognosis cancers near EOL. All trends are presented separately for non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic decedents. Near EOL is considered the 30 days before death or hospice enrollment. EOL, end of life; MMEDs, morphine milligram equivalents per day; UDS, urine drug screening.

Racial Disparities in EOL Opioid Access and UDS

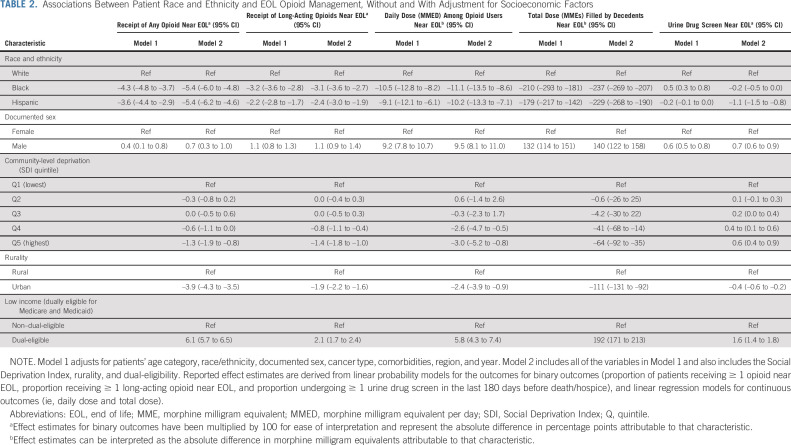

After adjustment for demographic and clinical factors (Table 2), Black and Hispanic patients were statistically less likely than White patients to receive ≥ 1 opioid prescription near EOL (Black, –4.3 percentage points, 95% CI, –4.8 to –3.6; Hispanic, –3.6 percentage points, 95% CI, –4.4 to –2.9) and ≥ 1 long-acting opioid prescription (Black, –3.1 percentage points, 95% CI, –3.6 to –2.8; Hispanic, –2.2 percentage points, 95% CI, –2.7 to –1.7). Among those filling ≥ 1 opioid prescription, Black patients received daily doses that were 10.5 MMEs lower (95% CI, –12.8 to –8.2) and Hispanic patients received daily doses that were 9.1 MMEs lower (95% CI, –12.1 to –6.1) than White patients. Compared with the total opioid dose filled per White decedent near EOL, the total dose filled per Black decedent was 210 MMEs lower (95% CI, –239.1 to –181.3) and the total dose filled per Hispanic decedent was 179.7 MMEs lower (95% CI, –217.1 to –142.3). Black decedents were 0.5 percentage points more likely than White decedents to undergo UDS near EOL (95% CI, 0.3 to 0.8).

TABLE 2.

Associations Between Patient Race and Ethnicity and EOL Opioid Management, Without and With Adjustment for Socioeconomic Factors

Influence of Socioeconomic Factors on EOL Opioid Outcomes and Disparities

Socioeconomic factors were strongly associated with EOL opioid management. Compared with decedents living in the least deprived SDI quintile, decedents living in the fourth and fifth (most deprived) SDI quintiles received statistically fewer opioids by every measure and were more likely to undergo UDS (Table 2). Compared with decedents residing in rural areas, those living in urban areas also received statistically fewer opioids across all measures but were less likely to undergo UDS. Contrary to our expectation, decedents who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid versus not received more opioids and were more likely to undergo UDS. Adjustment for socioeconomic factors did not attenuate disparities in EOL opioid access, and slightly magnified Black-White and Hispanic-White disparities in receipt of any opioid near EOL. Conversely, adjustment for socioeconomic factors eliminated the disparity between Black and White decedents in UDS.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in EOL Opioid Access and UDS by Patient Characteristics

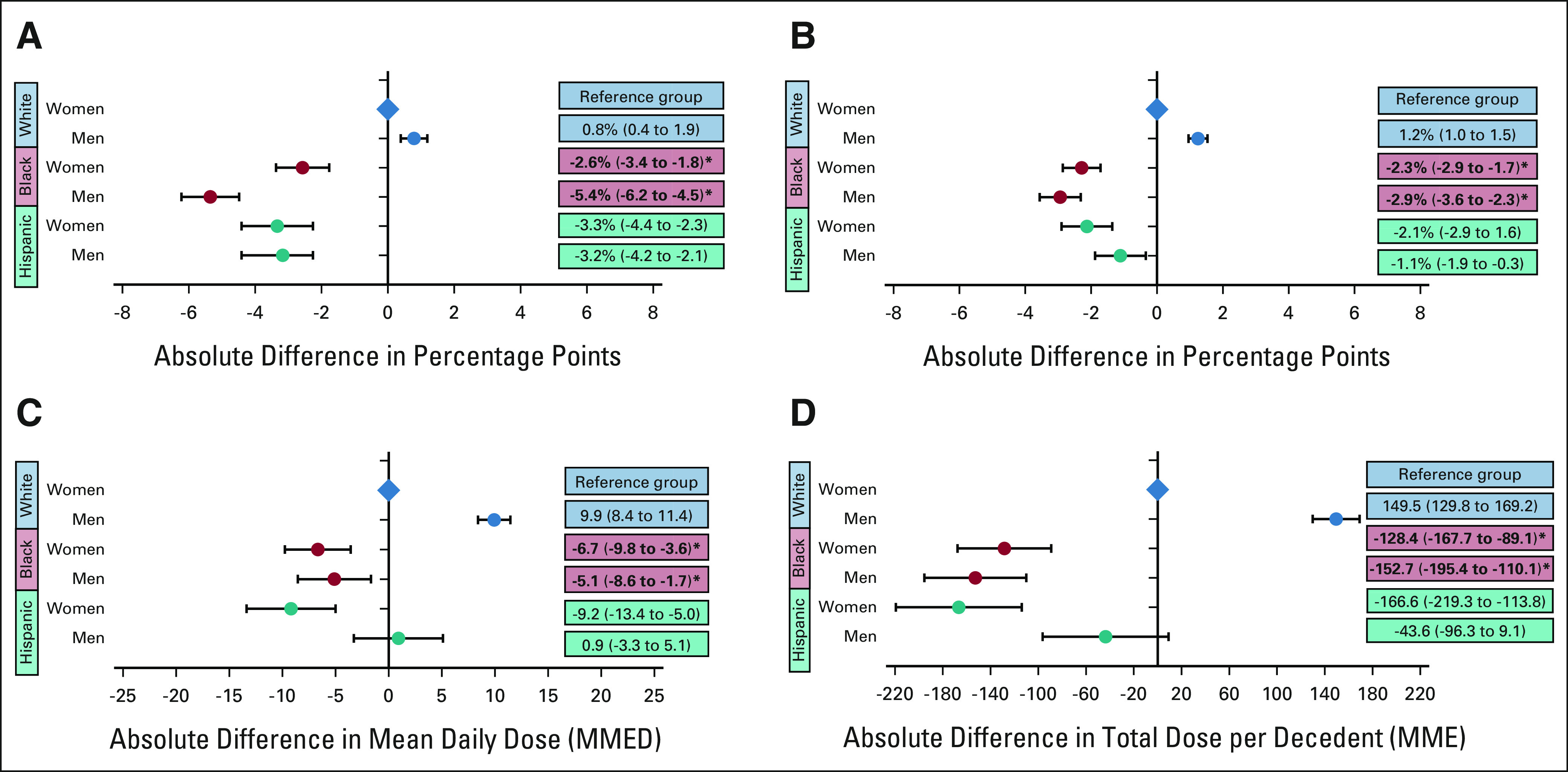

EOL opioid access varied widely between White, Black, and Hispanic patients according to documented sex, rurality, and dual-eligibility status. Examining EOL opioid access by race, ethnicity, and sex (Fig 2A) revealed that the association of Black race with EOL opioid access differed by sex, with White men being most likely and Black men being least likely to receive opioids. Black men and women, and Hispanic women received statistically fewer opioids than White men and women across all measures. For example, compared with White women, White men filled a mean total opioid dose near EOL that was 150 MMEs more per decedent (95% CI, 130 to 169), whereas Black women filled 128 MMEs less (95% CI, 168 to 153) and Black men filled 153 MMEs less (95% CI, –195 to –110). Black men were also disproportionately affected by racial disparities in UDS (Appendix Fig A2, online only).

FIG 2.

Racial and ethnic disparities in EOL opioid access by patient sex: the adjusted absolute differences by race, ethnicity, and sex (A) in the probability of filling any opioid near EOL; (B) in the probability of filling a long-acting opioid near EOL; (C) in opioid dose in MMED among patients filling an opioid prescription near EOL; and (D) in the total dose of opioids filled per decedent near EOL in MMEs. White women are the reference group for all analyses. Circles reflect the adjusted correlation coefficients and the error bars reflect the 95% CIs from regression models. For all analyses, EOL was defined as the last 30 days before death or hospice. Bold text and asterisk indicates the presence of a statistically significant, negative interaction between Black race and male sex. For all outcomes, the negative effect of being Black on EOL opioid outcomes is disproportionately large for men. EOL, end of life; MME, morphine milligram equivalent; MMED, morphine milligram equivalent per day.

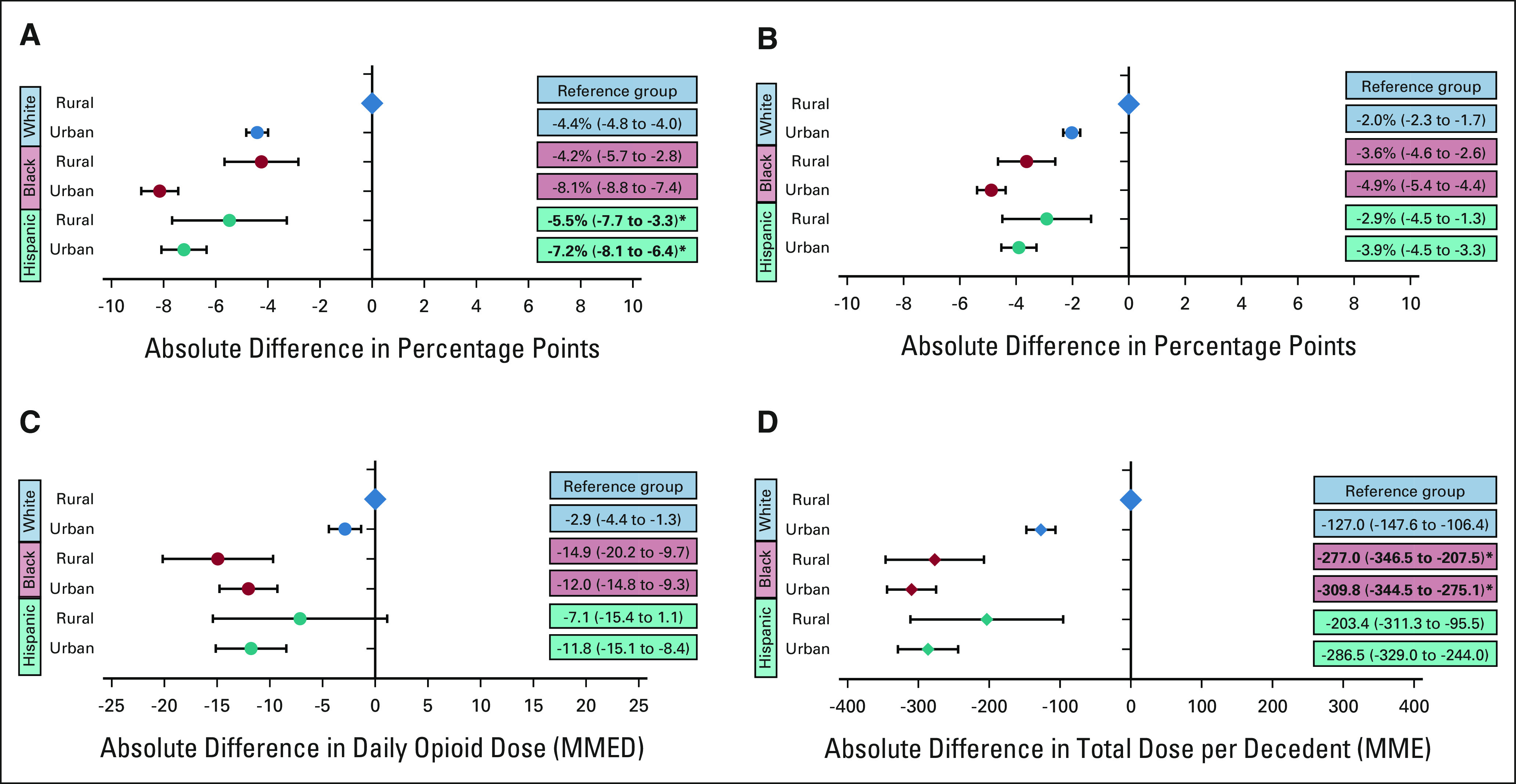

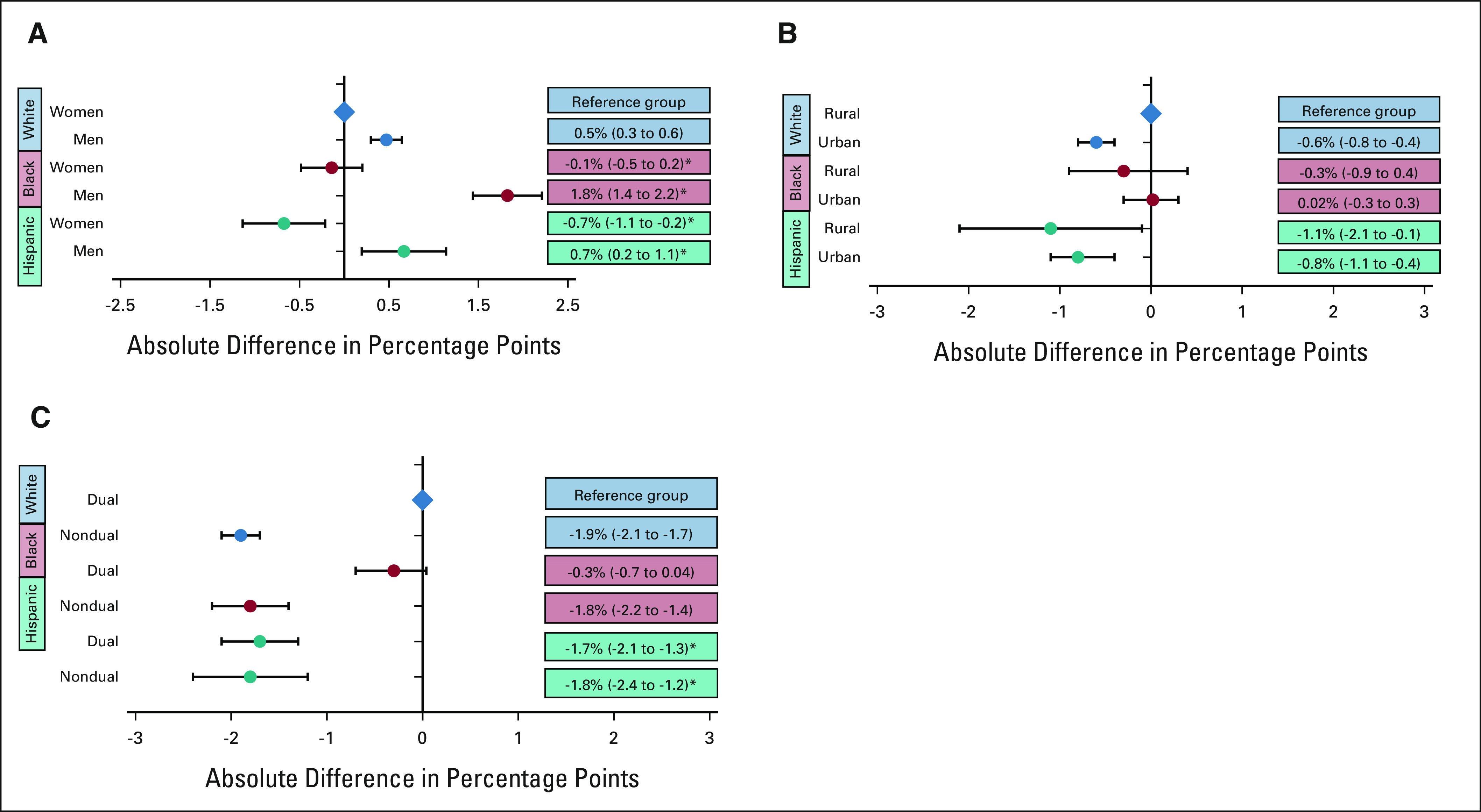

Examining EOL opioid access by race, ethnicity, and rurality (Fig 3) revealed that White rural-dwelling patients received the most opioids near EOL by every measure, whereas Black urban-dwelling patients generally received the least. Some of the largest variations in EOL opioid access were observed according to patient race, ethnicity, and dual-eligibility (Fig 4). White dual-eligible patients received the most opioids across all measures, whereas Black non–dual-eligible patients generally received the least. Compared with White dual-eligible patients, Black non–dual-eligible patients were 13.1 percentage points less likely to fill any opioid near EOL (95% CI, –14.0 to –12.1), 5.9 percentage points less likely to fill a long-acting opioid (95% CI, –6.6 to –5.3), their daily opioid dose was 15.0 MMEDs lower (95% CI, –18.7 to –11.2), and their mean total opioid dose was 439.8 MMEs less per decedent (95% CI, –484.8 to –394.7). The associations between dual-eligibility and EOL opioid access differed by race and ethnicity. White dual-eligible compared with non–dual-eligible patients received more opioids across all measures, whereas among Black and Hispanic patients, most measures of EOL opioid receipt did not differ by dual-eligibility.

FIG 3.

Racial and ethnic disparities in EOL opioid access by rurality: the adjusted absolute differences by race, ethnicity, and urban/rural status (A) in the probability of filling any opioid near EOL; (B) in the probability of filling a long-acting opioid near EOL; (C) in opioid dose in MMED among patients filling an opioid prescription near EOL, and (D) in the total dose of opioids filled per decedent near EOL in MMEs. White rural patients are the reference group for all analyses. Circles reflect the adjusted correlation coefficients and the error bars reflect the 95% CIs from regression models. For all analyses, EOL was defined as the last 30 days before death or hospice. Bold text and asterisk indicates the presence of a statistically significant positive interaction between race, ethnicity, and urban status. EOL, end of life; MME, morphine milligram equivalent; MMED, morphine milligram equivalent per day.

FIG 4.

Racial and ethnic disparities in EOL opioid access by Medicaid dual-eligibility: (A) the adjusted absolute differences by race, ethnicity, and Medicaid dual-eligibility in the probability of filling any opioid near EOL; (B) in the probability of filling a long-acting opioid near EOL; (C) in opioid dose in MMED among patients filling an opioid prescription near EOL; and (D) in the total dose of opioids filled per decedent near EOL in MMEs. White dual-eligible patients are the reference group for all analyses. Circles reflect the adjusted correlation coefficients and the error bars reflect the 95% CIs from regression models. For all analyses, EOL was defined as the last 30 days before death or hospice. Bold text and asterisk indicates the presence of a statistically significant negative interaction between race, ethnicity, and Medicaid dual-eligibility. EOL, end of life; MME, morphine milligram equivalent; MMED, morphine milligram equivalent per day.

DISCUSSION

In this large representative cohort of Medicare decedents with poor-prognosis cancers, we identified meaningful inequities in EOL opioid access that persisted from 2007 to 2019. UDS also expanded rapidly, despite no clear guidelines recommending its use for terminally ill populations.4 Compared with White patients, Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to receive any opioid and long-acting opioids; received lower daily doses and lower total doses, and were more often subjected to UDS. Adjustment for socioeconomic factors did not mitigate EOL opioid access disparities.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to document the scale of disparities in opioid access among US patients with cancer, and the first to document their persistence to EOL. Prescribing gaps were small to moderate in size, varied by outcome, and were greatest between Black and White patients. Black and Hispanic patients were, respectively, 4.3 and 3.6 percentage points less likely than White patients to receive any opioid, and 3.2 and 2.2 percentage points less likely to receive long-acting opioids near EOL. These modest absolute differences are clinically meaningful relative to the overall prevalence of EOL opioid receipt—which fell to 32.7% over the study—and long-acting opioids, which fell to 9.4%. Perhaps easier to conceptualize, inequities in total opioid dose translate into the average Black and Hispanic patient receiving approximately 28 or 24 fewer 5-mg oxycodone tablets in the final month of life than the average White patient, which is likely to impede pain control.

Racial and ethnic differences in opioid receipt and UDS were not explained by patient demographics or health status. Although our data lacked information about pain severity or preferences, cancer patients of color experience pain of similar or greater severity than White patients,52 and they value pain management.9,53 Patient-level factors such as stoicism, addiction concerns, fatalism, or mistrust of medical providers might interfere with Black and Hispanic patients' willingness to accept opioids54-56; however, these factors are likely rooted in an individual's experiences of racism within health care. Opioid access disparities are therefore clinically inappropriate and unjustifiable.57 Similarly, although patterns of prescription opioid misuse predominantly affect non-Hispanic White populations, inequities in UDS predominantly affected people of color.58,59 Although opioid overdose rates have recently increased among non-White populations, a long history of racial prejudice in society's response to substance misuse60 makes it imperative that substance misuse screening procedures be standardized and equitable.

Potential causes of disparities in EOL opioid access and UDS include clinicians' racial prejudice and unconscious bias, and structural racism within the health care system or society more broadly. Prior research suggests that clinicians often hold racist beliefs about pain (eg that Black patients have lower pain sensitivity),61 recognize pained expressions less readily on Black relative to White faces,62,63 disproportionately underestimate Black patients' pain severity,64 and may overestimate their substance misuse risk.24,25 Structural racism inherent to the health care delivery system may also contribute; patients of color may receive care in practices or health systems that prescribe opioids infrequently, use more UDS,15,19 or rely on pharmacies that stock fewer opioids.65,66 Interestingly, adjusting for Medicaid dual-eligibility, SDI, and rurality did not mitigate observed disparities. These measures are imperfect and do not account for all forms of structural disadvantage experienced by patients of color. Future research is needed to examine the contributions of other forms of racism such as residential segregation, and historic underinvestment in and overpolicing in communities of color, which could impede equitable access to pain management and further stigmatize opioid analgesics, hindering patients' willingness to accept them.

Several important observations arose from our analyses of EOL opioid access by race, ethnicity, and patient characteristics. Black men were disproportionately affected by disparities in opioid access and UDS. This suggests that clinicians may hold stronger negative biases toward Black men when assessing their need for opioid analgesics, or their risk for misuse. Opioid access also varied dramatically by dual-eligibility, which had different effects by patient race and ethnicity. Dual-eligibility was strongly associated with greater EOL opioid access among White patients. Although dual-eligibility was intended as a marker of low income, this association may reflect more adequate insurance drug coverage (ie, by qualifying for the low-income subsidy). By contrast, dual-eligibility conferred no such protections upon Hispanic patients, and it provided less protection to Black relative to White patients. More research is needed to understand these differential effects, and whether they reflect heightened bias against patients of color who are also poor, or if they represent inequities inherent to the Medicaid coverage system.

Our study has several limitations. First, we assessed opioid prescription fills, and not prescriptions that were written but unfilled. Inequities could partly reflect barriers to filling prescriptions, such as insurance or pharmacy-level factors. Second, we could not observe opioid prescription fills on hospice; however, our prior work suggests that EOL opioid utilization trends are not significantly altered by excluding the hospice period from the EOL period.8 Third, we focused on older Medicare beneficiaries. Thus, our findings likely represent conservative estimates of prescribing disparities, and should be examined among younger populations, including those with Medicaid or commercial insurance. Finally, we used administrative data to ascertain race and ethnicity. Prior studies have documented high validity for the Medicare variable for self-reported Black race, albeit lower for Hispanic ethnicity.38

In summary, from 2007 to 2019, we observed dramatic declines and substantial racial and ethnic inequities in prescription opioid access among Medicare beneficiaries with poor-prognosis cancers near EOL. Inequities were not attributable to patient demographic or clinical characteristics, nor were they attenuated by adjusting for measures of poverty, community deprivation, or rurality. Further research is required to understand the causes and consequences of these inequities, and whether they extend to other populations and phases of cancer care. Multilevel examinations could help identify the most potent drivers of the inequities, and thereby the most strategic targets for future interventions to promote equitable management of cancer pain near EOL.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Unadjusted Annual Trends in Opioid Tends in Opioid Access and UDS Among White, Black, and Hispanic Poor-Prognosis Cancer Decedents Near EOL

FIG A1.

Annual trends in UDS among patients with poor-prognosis cancers by race and ethnicity presents the proportion of patients with poor-prognosis cancer filling at least one opioid prescription, who also had one or more claims for a presumptive urine drug test in the 180 days before death or hospice enrollment. UDS, urine drug screening.

FIG A2.

Racial and ethnic disparities in UDS by patient sex, urban/rural status, and Medicaid dual-eligibility: (A) the adjusted absolute differences in the proportion of decedents undergoing UDS by race, ethnicity, and sex. White women are the reference group. *Statistically significant positive interactions were observed between Black and male, and Hispanic and male. (B) The adjusted absolute differences in UDS by race, ethnicity, and urban/rural status. White rural-dwelling patients are the reference group. (C) The adjusted absolute differences of UDS by race, ethnicity, and dual-eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid. White dual-eligible patients are the reference group. *We observed statistically significant negative interactions between Hispanic ethnicity and dual-eligibility. Circles reflect the adjusted correlation coefficients and the error bars reflect the 95% CIs from regression models. For all panels, UDS was assessed in the 180 days before death or hospice enrollment, and restricted to patients filling ≥ 1 opioid prescriptions. UDS, urine drug screening.

See accompanying editorial on page 2474

SUPPORT

Supported by AHRQ U19HS024072.

M.B.L. and A.A.W. are co-last authors of this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Andrea C. Enzinger, Kaushik Ghosh, Nancy L. Keating, David M. Cutler, Mary Beth Landrum, Alexi A. Wright

Financial support: David M. Cutler

Collection and assembly of data: Andrea C. Enzinger, Kaushik Ghosh, Nancy L. Keating, David M. Cutler, Mary Beth Landrum

Data analysis and interpretation: Andrea C. Enzinger, Kaushik Ghosh, David M. Cutler, Cheryl R. Clark, Narjust Florez, Mary Beth Landrum, Alexi A. Wright

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Opioid Access and Urine Drug Screening Among Older Patients With Poor-Prognosis Cancer Near the End of Life

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Andrea C. Enzinger

Consulting or Advisory Role: Five Prime Therapeutics, Merck, Astellas Pharma, Lilly, loxo, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Zymeworks, Takeda, Zymeworks, Istari, Ono Pharmaceutical, Xencor, Novartis

Research Funding: Medtronic

David M. Cutler

Expert Testimony: MDL—Opioids, MDL—JUUL

Cheryl R. Clark

Research Funding: IBM

Narjust Florez

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Pfizer, NeoGenomics Laboratories, Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb/Medarex, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics

Speakers' Bureau: MJH Life Sciences

Alexi A. Wright

Consulting or Advisory Role: GlaxoSmithKline, Cancer Support Community, Merck

Research Funding: NCCN/AstraZeneca (Inst), Pack Health (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, et al. : Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 51:1070-1090.e9, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meara E, Horwitz JR, Powell W, et al. : State legal restrictions and prescription-opioid use among disabled adults. N Engl J Med 375:44-53, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azizoddin DR, Knoerl R, Adam R, et al. : Cancer pain self-management in the context of a national opioid epidemic: Experiences of patients with advanced cancer using opioids. Cancer 127:3239-3245, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R: CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA 315:1624-1645, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humphreys K, Shover CL, Andrews CM, et al. : Responding to the opioid crisis in North America and beyond: Recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission. Lancet 399:555-604, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal A, Roberts A, Dusetzina SB, Royce TJ: Changes in opioid prescribing patterns among generalists and oncologists for Medicare Part D beneficiaries from 2013 to 2017. JAMA Oncol 6:1271, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jairam V, Yang DX, Pasha S, et al. : Temporal trends in opioid prescribing patterns among oncologists in the Medicare population. J Natl Cancer Inst 113:274-281, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enzinger AC, Ghosh K, Keating NL, et al. : US trends in opioid access among patients with poor prognosis cancer near the end-of-life. J Clin Oncol 39:2948-2958, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R: Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: Causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain 10:1187-1204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morden NE, Chyn D, Wood A, Meara E: Racial inequality in prescription opioid receipt—Role of individual health systems. N Engl J Med 385:342-351, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM: Time to take stock: A meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med 13:150-174, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morales ME, Yong RJ: Racial and ethnic disparities in the treatment of chronic pain. Pain Med 22:75-90, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman J, Kim D, Schneberk T, et al. : Assessment of racial/ethnic and income disparities in the prescription of opioids and other controlled medications in California. JAMA Intern Med 179:469-476, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Townsend TN, Bohnert ASB, Lagisetty P, Haffajee RL: Did prescribing laws disproportionately affect opioid dispensing to Black patients? Health Serv Res 57:482-496, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisch MJ, Lee JW, Weiss M, et al. : Prospective, observational study of pain and analgesic prescribing in medical oncology outpatients with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:1980-1988, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitzthum LK, Nalawade V, Riviere P, et al. : Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic discrepancies in opioid prescriptions among older patients with cancer. JCO Oncol Pract 17:e703-e713, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Valero V, et al. : Minority cancer patients and their providers: Pain management attitudes and practice. Cancer 88:1929-1938, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Baez L, et al. : Pain and treatment of pain in minority patients with cancer. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Minority Outpatient Pain Study. Ann Intern Med 127:813-816, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. : Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med 330:592-596, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Comprehensive Cancer Network : NCCN Clinical Practice Gudelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Adult Cancer Pain. Version 1.2022. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=3&id=1413 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fallon M, Giusti R, Aielli F, et al. : Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann Oncol 29:iv166-iv191, 2018. (suppl 4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taha SA, Westra JR, Raji MA, Kuo YF: Trends in urine drug testing among long-term opioid users, 2012-2018. Am J Prev Med 60:546-551, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker WC, Meghani S, Tetrault JM, Fiellin DA: Racial/ethnic differences in report of drug testing practices at the workplace level in the U.S. Am J Addict 23:357-362, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker WC, Starrels JL, Heo M, et al. : Racial differences in primary care opioid risk reduction strategies. Ann Fam Med 9:219-225, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaither JR, Gordon K, Crystal S, et al. : Racial disparities in discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy following illicit drug use among black and white patients. Drug and Alcohol Depend 192:371-376, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pflugeisen BM, Mou J, Drennan KJ, Straub HL: Demographic discrepancies in prenatal urine drug screening in Washington state surrounding recreational marijuana legalization and accessibility. Matern Child Health J 24:1505-1514, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paice JA: Cancer pain management and the opioid crisis in America: How to preserve hard-earned gains in improving the quality of cancer pain management. Cancer 124:2491-2497, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arthur JA: Urine drug testing in cancer pain management. Oncologist 25:99-104, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unger JM, Moseley AB, Cheung CK, et al. : Persistent disparity: Socioeconomic deprivation and cancer outcomes in patients treated in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 39:1339-1348, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P: Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 51:S28-S40, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, Vu C: Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv Res 54:1374-1388, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. : Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA 300:2613-2620, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulozzi LJ, Ryan GW: Opioid analgesics and rates of fatal drug poisoning in the United States. Am J Prev Med 31:506-511, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker AM, Strunk D, Fiellin DA: State responses to the opioid crisis. J Law Med Ethics 46:367-381, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guy GP Jr., Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. : Vital signs: Changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66:697-704, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69:7-34, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : National Vital Statistics System. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/index.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fnchs%2Fnvss.htm [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarrin OF, Nyandege AN, Grafova IB, et al. : Validity of race and ethnicity codes in Medicare administrative data compared with gold-standard self-reported race collected during routine home health care visits. Med Care 58:e1-e8, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Data Resources: Analyzing Prescription Data and Morphine Milligram Equivalents. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/resources/data.html [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng E, Soulos PR, Irwin ML, et al. : Neighborhood and individual socioeconomic disadvantage and survival among patients with nonmetastatic common cancers. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2139593, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services : MLN Fact Sheet: Beneficiaries Dually Eligible for Medicare & Medicaid. 2022. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/medicare_beneficiaries_dual_eligibles_at_a_glance.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butler DC, Petterson S, Phillips RL, Bazemore AW: Measures of social deprivation that predict health care access and need within a rational area of primary care service delivery. Health Serv Res 48:539-559, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liaw W, Krist AH, Tong ST, et al. : Living in "cold spot" communities is associated with poor health and health quality. J Am Board Fam Med 31:342-350, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Khullar D, Wang F, et al. : Socioeconomic variation in characteristics, outcomes, and healthcare utilization of COVID-19 patients in New York City. PLoS One 16:e0255171, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cottrell EK, Hendricks M, Dambrun K, et al. : Comparison of community-level and patient-level social risk data in a network of community health Centers. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2016852, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cottrell EK, Dambrun K, Cowburn S, et al. : Variation in electronic health record documentation of social determinants of health across a national network of community health Centers. Am J Prev Med 57:S65-S73, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. : Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain 30:605-612, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lund BC, Ohl ME, Hadlandsmyth K, Mosher HJ: Regional and rural-urban variation in opioid prescribing in the veterans health administration. Mil Med 184:894-900, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caldwell JT, Ford CL, Wallace SP, et al. : Intersection of living in a rural versus urban area and race/ethnicity in explaining access to health care in the United States. Am J Public Health 106:1463-1469, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.US Department of Agriculture : Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGuire TG, Alegria M, Cook BL, et al. : Implementing the Institute of Medicine definition of disparities: An application to mental health care. Health Serv Res 41:1979-2005, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green CR, Montague L, Hart-Johnson TA: Consistent and breakthrough pain in diverse advanced cancer patients: A longitudinal examination. J Pain Symptom Manage 37:831-847, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meghani SH, Houldin AD: The meanings of and attitudes about cancer pain among African Americans. Oncol Nurs Forum 34:1179-1186, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson KO, Richman SP, Hurley J, et al. : Cancer pain management among underserved minority outpatients: Perceived needs and barriers to optimal control. Cancer 94:2295-2304, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meghani SH, Thompson AM, Chittams J, et al. : Adherence to analgesics for cancer pain: A comparative study of African Americans and Whites using an electronic monitoring device. J Pain 16:825-835, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwon JH, Hui D, Chisholm G, et al. : Experience of barriers to pain management in patients receiving outpatient palliative care. J Palliat Med 16:908-914, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Unequal Treatment : Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Furr-Holden D, Milam AJ, Wang L, Sadler R: African Americans now outpace whites in opioid-involved overdose deaths: A comparison of temporal trends from 1999 to 2018. Addiction 116:677-683, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoopsick RA, Homish GG, Leonard KE: Differences in opioid overdose mortality rates among middle-aged adults by race/ethnicity and sex, 1999-2018. Public Health Rep 136:192-200, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steenland K, Goldsmith DF: Silica exposure and autoimmune diseases. Am J Ind Med 28:603-608, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN: Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:4296-4301, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kissi A, Van Ryckeghem DML, Mende-Siedlecki P, et al. : Racial disparities in observers' attention to and estimations of others' pain. Pain 163:745-752, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mende-Siedlecki P, Lin J, Ferron S, et al. : Seeing no pain: Assessing the generalizability of racial bias in pain perception. Emotion 21:932-950, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Staton LJ, Panda M, Chen I, et al. : When race matters: Disagreement in pain perception between patients and their physicians in primary care. J Natl Med Assoc 99:532-538, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morrison RS, Wallenstein S, Natale DK, et al. : “We don't carry that”—Failure of pharmacies in predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods to stock opioid analgesics. N Engl J Med 342:1023-1026, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Green CR, Ndao-Brumblay SK, West B, Washington T: Differences in prescription opioid analgesic availability: Comparing minority and white pharmacies across Michigan. J Pain 6:689-699, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]